Why Did We Develop a New Method, CLTS, for scRNA-seq Data Normalization?

Presently, prevalent normalization methods such as CP10K, CPM, TPM, SCnorm, and SCTransform, encounter scaling issues. Specifically,

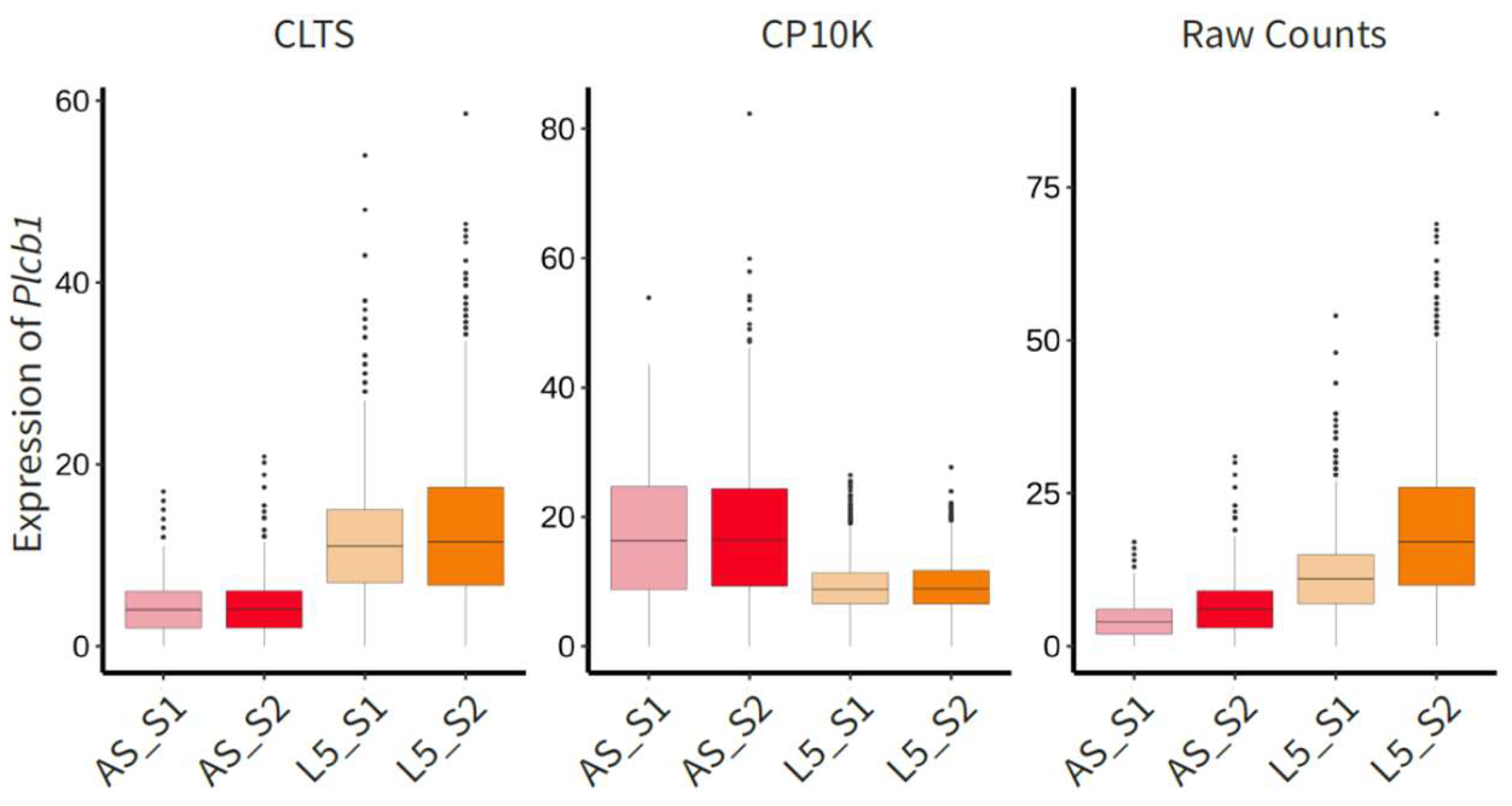

they amplify expression profiles of various cell types on different scales. It’s important to note that not all cell types express the same number of genes and RNAs. Moreover, the total RNAs expressed by a cell (defined as the cell’s

transcriptome size) maintains a robust linear correlation with the quantity of genes it expresses. Take, for instance, the extreme case of red blood cells, which express only one gene,

hemoglobin, while stem cells typically express more than 10,000 genes. This implies a significant disparity in the total RNAs expressed by different cell types. Therefore, if we employ CP10K to standardize the transcriptome size of all cells to 10K, the expression profiles of cells with smaller transcriptome sizes may be relatively amplified, while those with larger transcriptome sizes could be relatively suppressed. For instance, the transcriptome sizes of AS cells are significantly smaller than those of L5 cells. Therefore, CP10K will relatively amplify the expression profiles of AS cells and suppress those of L5 cells. As a result, following CP10K normalization, some genes, such as

Plcb1, that appear to be highly expressed in AS cells may, in reality, have higher expression in L5 cells (

Figure 1: CP10K). These scaling issues can lead to problems in cell type annotation and deconvolution (defined as Type-I issues). Therefore, we developed CLTS, a method designed to address the technology-induced effects present in scRNA-seq data, without the scaling issues (

Figure 1: CLTS).

What Is Hypothesis and the Basic Idea of CLTS Normalization Method?

The basic assumptions of the CLTS model are:

The value of a cell’s true transcriptome size, or the total amount of RNAs truly expressed by a cell, should remain stable within a narrow range for any type of cell. However, it’s worth noting that the values of true transcriptome sizes may vary significantly among different types of cells.

The total raw count obtained from any scRNA-seq data for a cell is essentially a measure of the cell’s true transcriptome size. Moreover, the measured transcriptome size for all cells in the same sample should be proportional to its real value (Although the variance is usually large). Overall, this proportion should be fairly similar for all cells within the same sample. For simplicity, we usually refer to the “measured transcriptome size” as “transcriptome size”.

The proportion of the measured values to the true transcriptome sizes can vary significantly among cells in different samples. This is what leads to significant differences in gene expression of the same cell type across different samples.

Our assumptions have been supported by many scRNA-seq data, including:

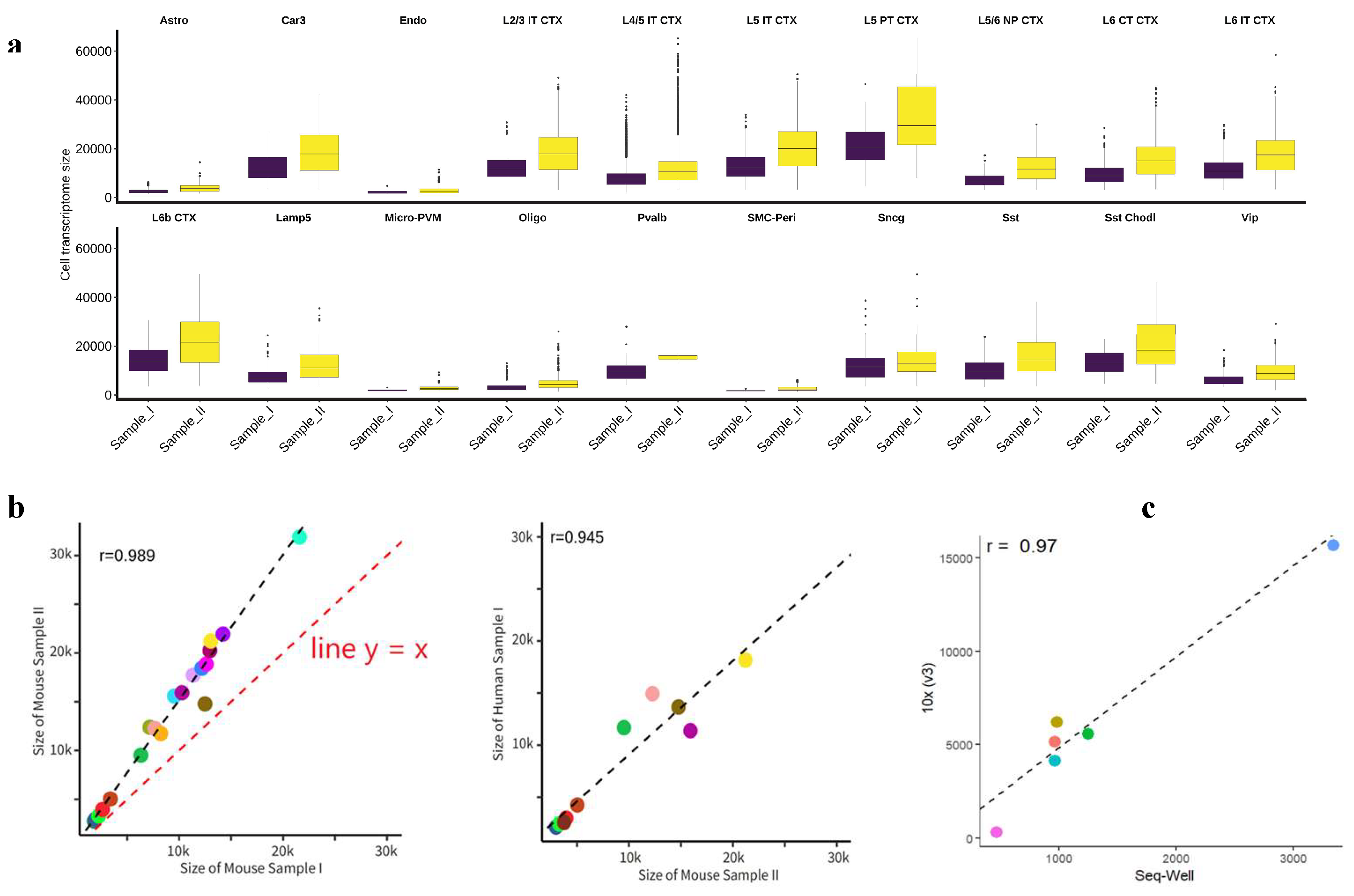

The transcriptome sizes of different types of cells show considerable variation, while those of the same cell type remain within a narrow range (

Figure 2a).

The average transcriptome sizes of different cell types in different samples show a strong linear relationship. Basically, by multiplying the average transcriptome sizes of all cell types in one of the two samples by a constant, we can make the average transcriptome sizes of all matching cell types in the two samples similar (

Figure 2b).

This linear relationship remains not only between samples of the same species, such as between two mouse brain samples (

Figure 2b), but also between samples of different species, such as between a mouse brain sample and a human brain sample (

Figure 2c). Additionally, this linear correlation holds across samples with scRNA-seq data from various sequencing platforms, such as 10x (v3) and Seq-well (

Figure 2d).

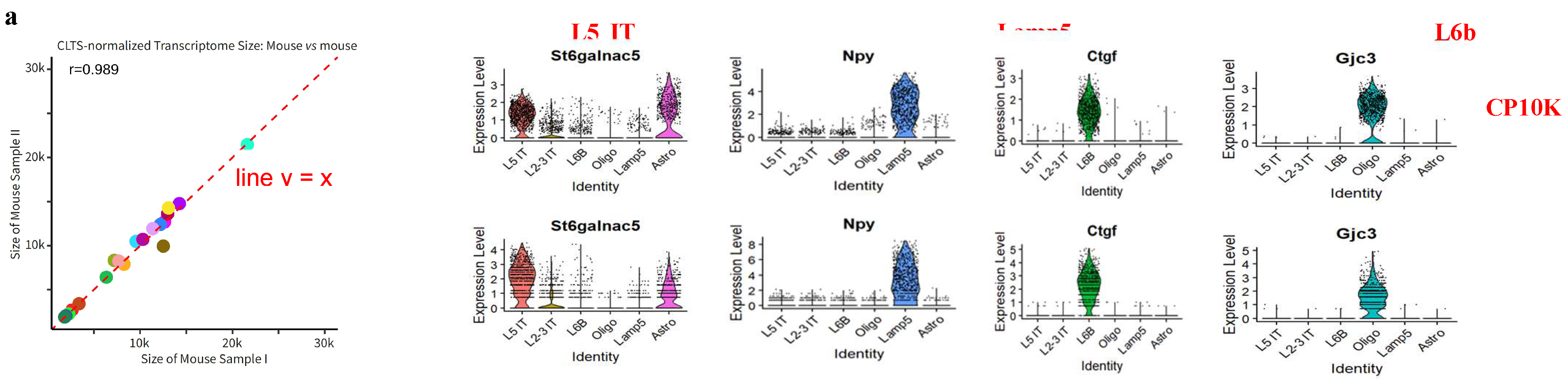

The basic idea of CLTS:

Our novel model,

CLTS, leverages this linear correlation to perform normalization. Consequently, after normalization, the average transcriptome sizes of any given cell type become similar across all samples (

Figure 3a). It is obvious that CLTS does not have the scaling issues that CP10K has.

What Should We Notice When Using Seurat for scRNA-seq Data Processing?

Seurat is the most widely used software for processing scRNA-seq data. By default, Seurat applies the CP10K normalization method, which may have problems in cell type annotations and the downstream analysis.

Cell clustering is a process that considers the similarity of cell expression profiles, with CP10K exerting a minimal influence on this step.

In the process of determining the cell type of each Seurat cluster using cell type markers, typically, the selected type markers, such as

Npy,

Ctgf and

Gjc3 (as shown in

Figure 3b), are predominantly expressed in a single cell type or Seurat cluster. Consequently, CP10K does not compromise the precision of cell type annotation. However, if a cell type marker, like

St6galnac5 (refer to

Figure 3b), demonstrates substantial expression in multiple cell types or Seurat clusters, it becomes imperative to reevaluate the results for potential impacts stemming from CP10K’s scaling issues. Therefore, utilizing the CLTS-normalized data for cell type annotations of Seurat clusters can help prevent annotation errors.

During downstream analysis, such as identifying genes that are highly expressed in specific cell types, CP10K can significantly influence the results. For instance, several genes that exhibit high expression in Astrocytes may actually have higher expression in L5 cells. Consequently, we strongly advocate for the use of CLTS-normalized data in downstream analysis.

How Do We Integrate Seurat and CLTS for scRNA-seq Data Processing?

There are two primary methods to approach this.

In the first approach, we employ Seurat in a traditional manner for clustering and cell type annotations. Following this, we utilize CLTS for normalization of the scRNA-seq data. We then use this CLTS-normalized data to examine if the cell type markers are impacted by CP10K scaling issues and to conduct other downstream analysis.

In the second approach, we consider each Seurat cluster as a distinct cell type after the clustering step. Consequently, we use the cluster information and CLTS for normalizing the scRNA-seq data. We then employ CLTS-normalized data for cell type annotation of the Seurat clusters and for performing additional downstream analysis. You can find demonstration codes on how to implement this method on the ReDeconv website.

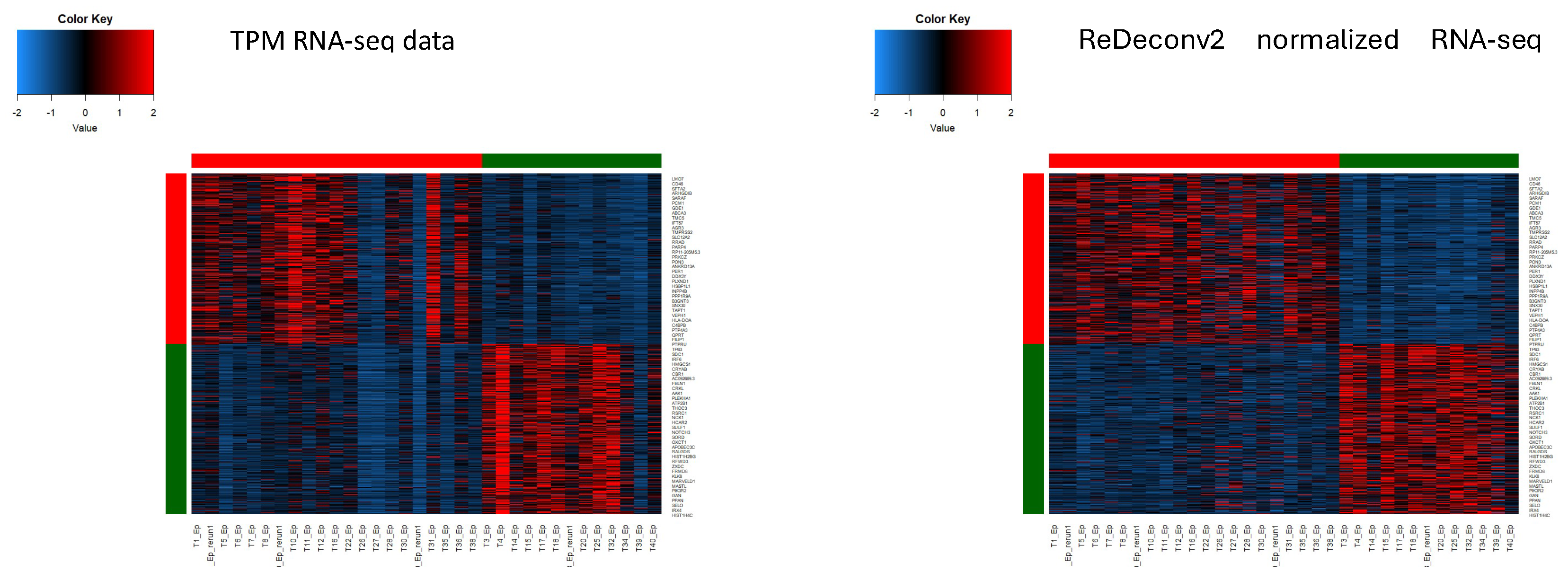

Does the Normalization of Bulk RNA-seq Data Need to Consider the Transcriptome Sizes of Cells?

Theoretically, it is straightforward to comprehend that the transcriptome size of a mixture sample with bulk RNA-seq data should correlate with its cell type composition. For instance, the transcriptome size of a sample consisting of 10% astrocytes and 90% L5 cells is expected to be larger than that of a sample with 90% astrocytes and 10% L5 cells. Presently, CPM, TPM, and FPKM are commonly employed for bulk RNA-seq data normalization, which however, disregards the cell type composition of mixture samples. Even in the raw-count format for bulk RNA-seq data, transcriptome sizes are not associated with their cell type composition, as the sequencing process typically includes a step to standardize all sample concentrations (of RNAs or RNA fragments) before sequencing. Therefore, we should normalize bulk RNA-seq data according to the cell type composition of samples and the transcriptome sizes of different cell types. This is particularly crucial if the expression profiles of some samples appear unusually high or low in the heatmap (refer to

Figure 4a).

At present, we usually consider that those samples are problematic and therefore, choose to exclude them from the data.

While ReDeconv does not offer this function, individuals can easily perform the normalization using the results of cell type percentages for mixture samples with bulk RNA-seq data. Fundamentally, one should first identify common genes in the scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data, where the scRNA-seq data should be normalized by CLTS and the bulk RNA-seq data should be in TPM or FPKM. Subsequently, use the common genes to compute the average transcriptome sizes of all cell types from the scRNA-seq data and the transcriptome size of each sample in the bulk RNA-seq data. Assuming

scT1,

scT2, …,

scTk are the mean transcriptome sizes of all cell types, and

bulkTi is the transcriptome size of mixture sample

i. Further assuming that the percentage of all cell types for the mixture sample

i are

P1i,

P2i, …,

Pki. Then the normalized transcriptome size,

norm(

bulkTi), of the mixture sample

i should be:

scT1P1i +

scT2P2i + … +

scTkPki. Consequently, to perform normalization for the mixture sample

i, one simply needs to multiply the expression of each gene in sample

i by

norm(

bulkTi)/

bulkTi. After normalization, we might discover that the issue may not lie with the sample itself, but rather with the TPM normalization process (refer to

Figure 4b).

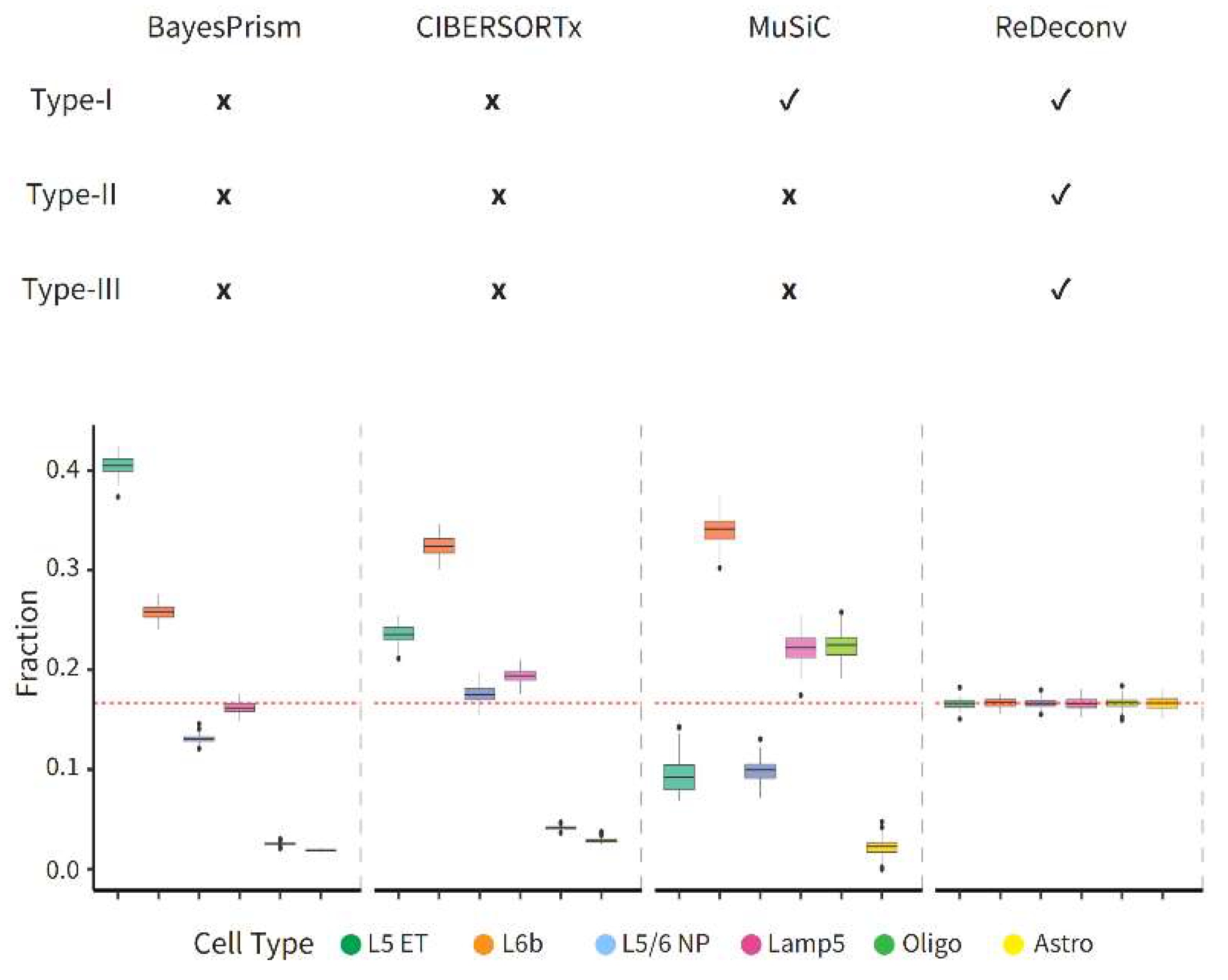

Why Did We Develop a New Model, ReDevonv, for Cell Type Deconvolution?

Even though the cell type deconvolution problem has been under investigation for over a decade, certain critical issues remain unaddressed by even the most advanced current models, including BayesPrism, CIBERSORTx, and MuSiC. We have categorized these problems into Type-I, Type-II, and Type-III issues. Type-I issues pertain to improper normalization of the scRNA-seq data reference, Type-II issues involve the use of mismatched normalization for the scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data, and Type-III issues relate to the expression stability of genes across all cell types. If we adhere to the software manuals of these models for choosing the format of scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data, all previous methods will exhibit Type-II and Type-III issues, while BayesPrism and CIBERSORTx will also manifest Type-I issues. These problems significantly impact the results of deconvolution. This is the reason we developed ReDeconv, which addresses these three types of issues and significantly enhances the performance of deconvolution (refer to

Figure 5).

What Is the Basic Idea of Cell Type Deconvolution?

In a mixture sample with bulk RNA-seq data, the RNAs of each gene originate from various cell types. Thus, for any given gene, such as gene

i, if we determine the gene's expression in the mixture sample and the expression means (

) of the gene across all cell types, we should be able to establish equations (1). This concept forms the fundamental basis for using references to ascertain the fraction of different cell types present in the mixture samples. Deconvolution models attempt to find all coefficients to fit the equations (1), where models based on linear regression, such as CIBERSORT/CIBERSORx, try to directly fit the equations (1), while other models based on Bayesian or probability, such as BayesPrism, MuSiC, and our new model, assume that the expected value of

should be equal to

, for

.

What Is the Type-I Issues?

Type-I issues arise from the application of

inappropriate normalization methods, such as CP10K and CPM, to scRNA-seq data used as a reference for deconvolution. This primarily addresses the sequence depth problem. For instance, because CP10K would amplify the expression of genes in cells with smaller transcriptome sizes, it could alter the expression means of genes in cell type 1 from

to

. To maintain the balance of equations (1), the fraction of cell type 1 would be adjusted from

to

. Therefore, the influence of Type-I issues on deconvolution can be elucidated by equations (2). As illustrated in

Figure 6, there is a clear agreement between the results and our mathematical analysis.

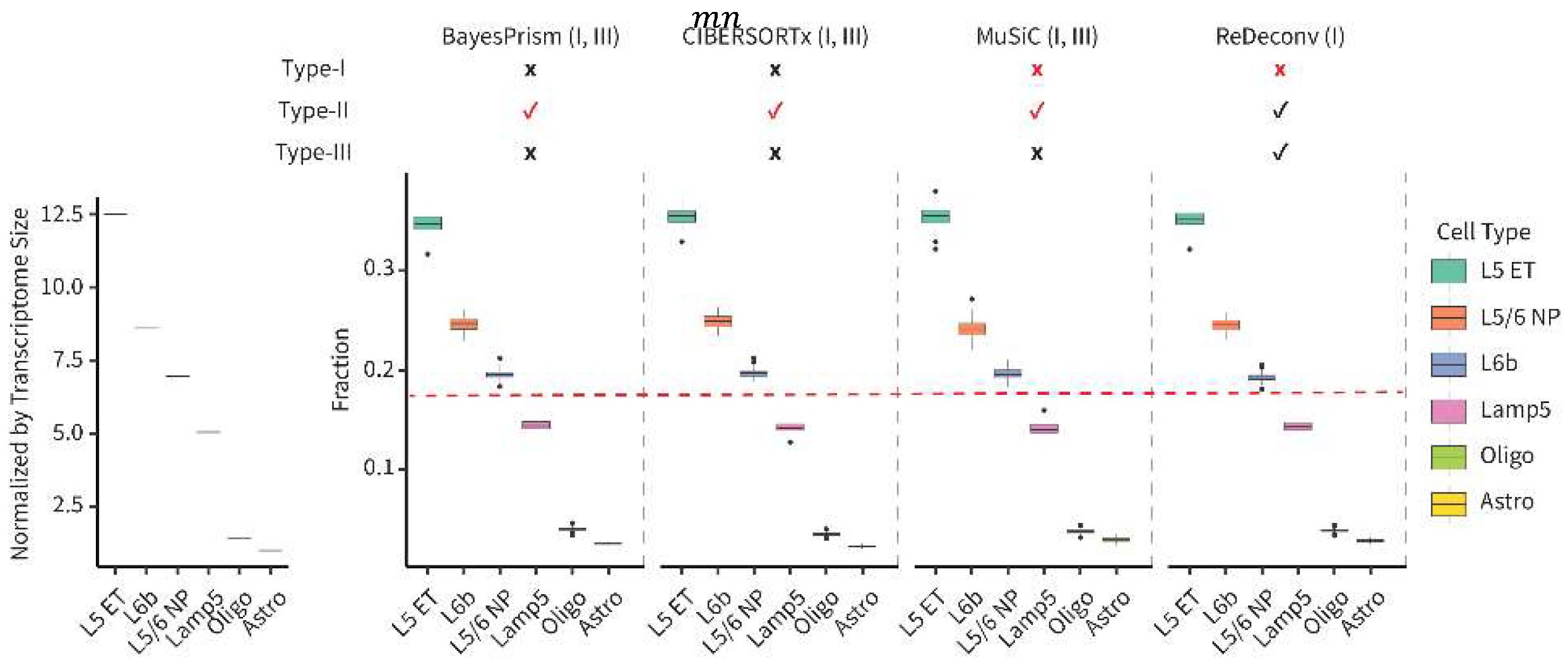

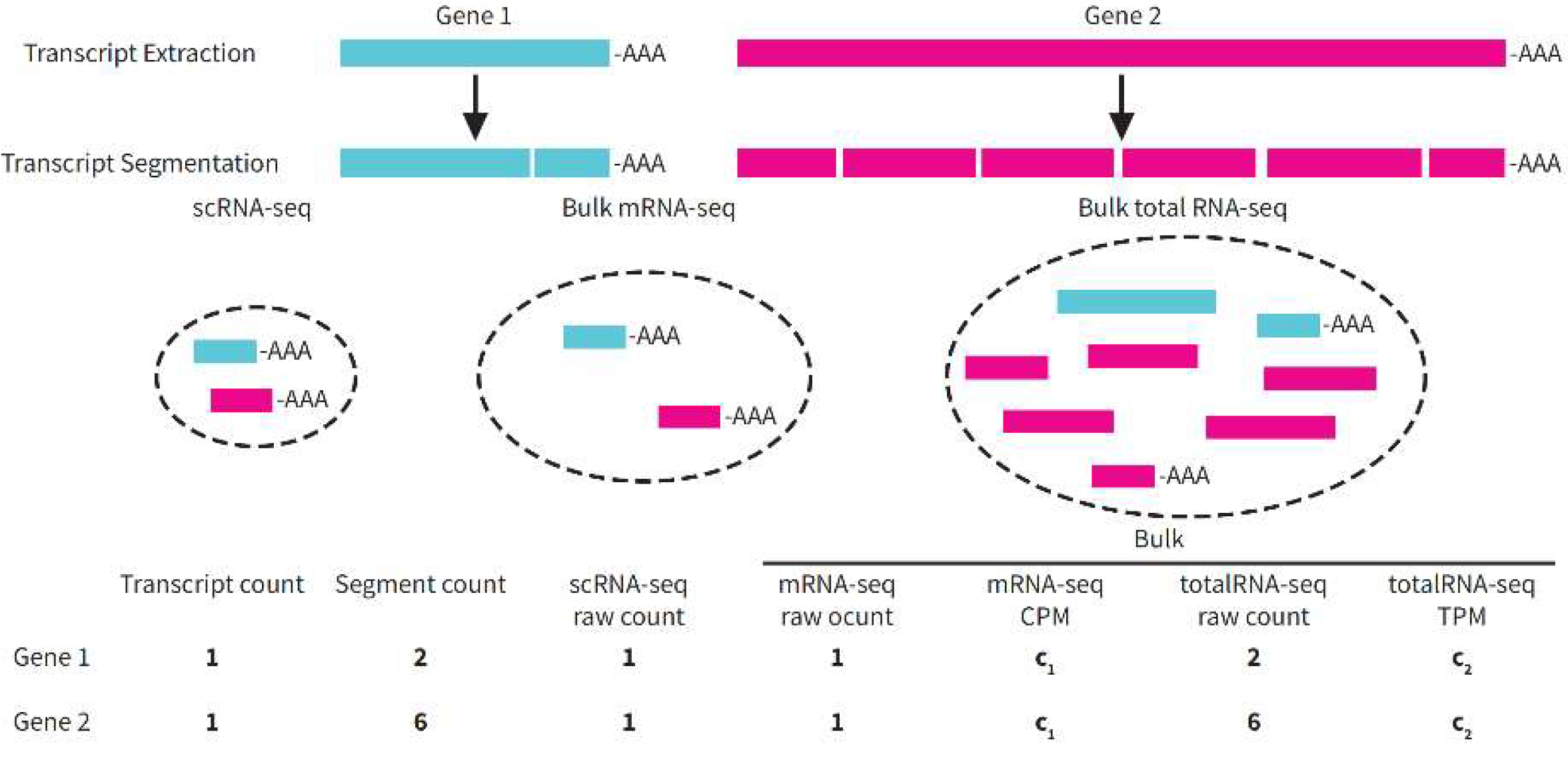

What Is the Type-II Issues?

Type-II issues stem from the application of

mismatched normalization to the scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data used for deconvolution. This primarily pertains to gene length normalization. As demonstrated in

Figure 7, the raw-count expression of genes in the scRNA-seq data is not linked to gene length, while in the total bulk RNA-seq data, it is. Consequently, if we employ raw-count scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data (or TPM scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data) for deconvolution, our solution will be dictated by equations (3), rather than being derived from equations (1). This elucidates how Type-II issues influence deconvolution. (

Li represents the gene length of gene

i). Similarly, equations (4) reveal how the combination of both Type-I and Type-II issues impact deconvolution.

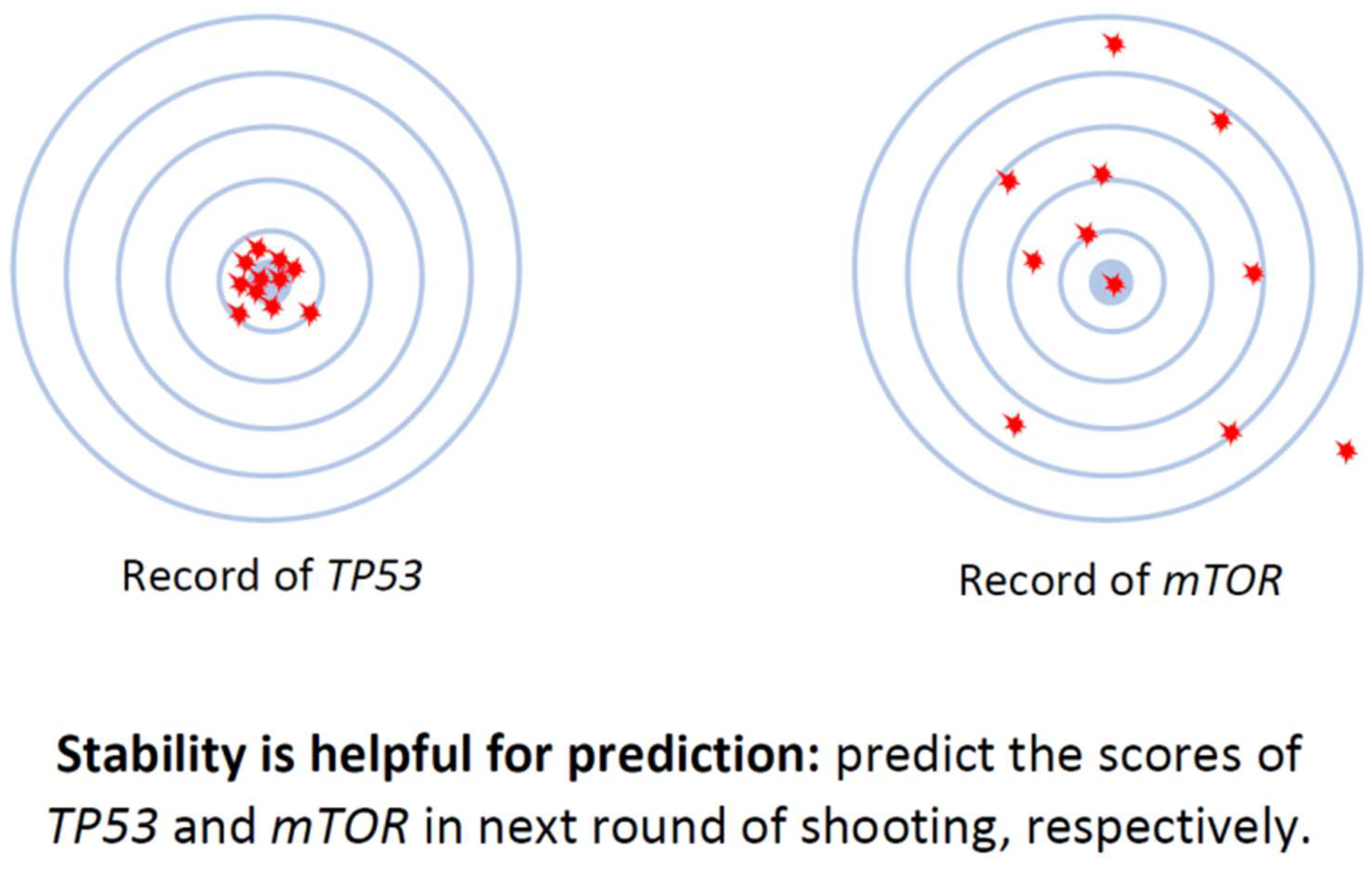

What Is the Type-III Issues?

Type-III issues pertain to the robustness of deconvolution models. The expression value of each gene within a cell of a given type is not constant. Thus, the expression of a gene in the same cell type in the reference (scRNA-seq data) and mixture samples (bulk RNA-seq data) should exhibit some differences, which can impact the accuracy of fraction predictions. To address this issue, we

first select signature genes with more stable expressions (

Figure 8).

Secondly, we incorporate the expression variance of these signature genes into our new computational model designed to determine cell type fractions in the mixture samples (please refer to equation (5)).

Why Have These Issues Not Been Noticed Before in Model Evaluations?

The primary reasons why Type-I and Type-II issues have been overlooked in the assessment of current popular deconvolution models can be traced back to two factors. Firstly, real tumor data often lacks a definitive ground truth. Secondly, when synthetic bulk RNA-seq data is derived from raw-count, CPM, or CP10K scRNA-seq data, these are also used as references, resulting in the disappearance of Type-II issues, or both Type-I and Type-II issues. However, it’s important to note that this kind of bulk RNA-seq data typically does not exist in real-world situations.

Notes: Certain models, like BayesPrism and CIBERSORTx, that automatically apply CP10K/CPM to the scRNA-seq data, invariably have Type-I issues, even when utilizing raw-count or CLTS-normalized scRNA-seq data as references. Prior to using any deconvolution models, it’s advisable to verify if the models exhibit any types of issues.

If CLTS-normalized scRNA-seq data and TPM/FPKM bulk RNA-seq data are used as inputs for ReDeconv, then all Type-I, II, III issues are effectively addressed. For more detailed information about the ReDeconv model and instructions on how to use ReDeconv, please refer to our paper, “

Transcriptome Size Matters for Single-Cell RNA-seq Normalization and Bulk Deconvolution” (Nature Communications, Feb. 2025), and visit the website –

https://redeconv.stjude.org/home. Most of the figures in this summary are derived from our paper in Nature Communications.

Figure 1.

How different normalization methods impact the expression of gene in the scRNA-seq data. Expressions of gene Plcb1 in L5 and AS of mouse brain Sample_1 and Sample_2 under CLTS-, CP10K-normalized, and raw count scRNA-seq data, respectively.

Figure 1.

How different normalization methods impact the expression of gene in the scRNA-seq data. Expressions of gene Plcb1 in L5 and AS of mouse brain Sample_1 and Sample_2 under CLTS-, CP10K-normalized, and raw count scRNA-seq data, respectively.

Figure 2.

Transcriptome sizes of different cell types across samples. a, Transcriptome sizes of different types of cells in mouse brain Sample_1 and Sample_2. b–d, Scatter plots depict the comparison of mean transcriptome sizes of various cell types in two samples or the same sample with data under different sequencing platforms, demonstrating a strong linear correlation between the mean transcriptome sizes under raw count in the two samples or two sequencing platforms. b, mouse brain Sample_1 vs. Sample_2. c, mouse brain Sample_2 (x-axis) vs. human brain sample (y-axis). d, 10x (v3) vs. Seq-Well.

Figure 2.

Transcriptome sizes of different cell types across samples. a, Transcriptome sizes of different types of cells in mouse brain Sample_1 and Sample_2. b–d, Scatter plots depict the comparison of mean transcriptome sizes of various cell types in two samples or the same sample with data under different sequencing platforms, demonstrating a strong linear correlation between the mean transcriptome sizes under raw count in the two samples or two sequencing platforms. b, mouse brain Sample_1 vs. Sample_2. c, mouse brain Sample_2 (x-axis) vs. human brain sample (y-axis). d, 10x (v3) vs. Seq-Well.

Figure 3.

CLTS normalization. a, Transcriptome size means of different types of cells in mouse brain Sample_1 and Sample_2 after the CLTS normalization. b, Expressions of cell type markers in Seurat clusters under CP10K and CLTS, respectively.

Figure 3.

CLTS normalization. a, Transcriptome size means of different types of cells in mouse brain Sample_1 and Sample_2 after the CLTS normalization. b, Expressions of cell type markers in Seurat clusters under CP10K and CLTS, respectively.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of DEGs under TPM and ReDeconv2-normalized bulk RNA-seq data. a, Heatmap of DEGs for samples of two groups under TPM RNA-seq data. b, Heatmap of the same DEGs in Figure 4a under ReDeconv2-normalized data.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of DEGs under TPM and ReDeconv2-normalized bulk RNA-seq data. a, Heatmap of DEGs for samples of two groups under TPM RNA-seq data. b, Heatmap of the same DEGs in Figure 4a under ReDeconv2-normalized data.

Figure 5.

Overall performance of ReDeconv vs. popular bulk deconvolution methods. Cell type fractions predicted by BayesPrism, CIBERSORTx, MuSiC, and ReDeconv against ground truth. Recomended input formats and parameters were used according to each method’s manual. Bulk RNA-seq data were 100 synthetic mixture samples with equal fractions to all cell types. In all tests, CIBERSORTx and BayesPrism exhibited all three types of issues, while MuSiC showed Type-II and Type-III issues. ReDeconv, however, didn’t exhibit these three types of issues.

Figure 5.

Overall performance of ReDeconv vs. popular bulk deconvolution methods. Cell type fractions predicted by BayesPrism, CIBERSORTx, MuSiC, and ReDeconv against ground truth. Recomended input formats and parameters were used according to each method’s manual. Bulk RNA-seq data were 100 synthetic mixture samples with equal fractions to all cell types. In all tests, CIBERSORTx and BayesPrism exhibited all three types of issues, while MuSiC showed Type-II and Type-III issues. ReDeconv, however, didn’t exhibit these three types of issues.

Figure 6.

How Type-I issues impact deconvolution. Cell type fractions predicted by BayesPrism, CIBERSORTx, MuSiC, and ReDeconv against ground truth. All models have been modified such that they are mainly affected by Type-I issues. Bulk RNA-seq data were 100 synthetic mixture samples with equal fractions to all cell types.

Figure 6.

How Type-I issues impact deconvolution. Cell type fractions predicted by BayesPrism, CIBERSORTx, MuSiC, and ReDeconv against ground truth. All models have been modified such that they are mainly affected by Type-I issues. Bulk RNA-seq data were 100 synthetic mixture samples with equal fractions to all cell types.

Figure 7.

Single cell and bulk RNA sequencing. Illustrates the readouts for scRNA-seq, bulk mRNA-seq, and bulk total RNA-seq data that were subjected to different normalization methods.

Figure 7.

Single cell and bulk RNA sequencing. Illustrates the readouts for scRNA-seq, bulk mRNA-seq, and bulk total RNA-seq data that were subjected to different normalization methods.

Figure 8.

Illustrate of how the stability of gene expression impacts prediction. Genes exhibiting stable expression indicate that there are minor differences between their expression in the scRNA-seq data reference and in the bulk RNA-seq data. Therefore, selecting these genes as signature genes can enhance the prediction accuracy in the deconvolution process.

Figure 8.

Illustrate of how the stability of gene expression impacts prediction. Genes exhibiting stable expression indicate that there are minor differences between their expression in the scRNA-seq data reference and in the bulk RNA-seq data. Therefore, selecting these genes as signature genes can enhance the prediction accuracy in the deconvolution process.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).