1. Introduction

Comprehension failure is not prediction error; it is delayed access to retrievable meaning. Traditional entropy approaches quantify linguistic uncertainty without considering observer-specific processing differences. Yet evidence from neurolinguistics and computational cognition shows that interpretive effort, and therefore uncertainty resolution, depends on an observer’s attentional state, working-memory capacity, and contextual familiarity [

15,

26]. Earlier entropy-based models conflate linguistic probability with observer cost, obscuring how processing difficulty emerges from observer-bound retrieval delays. ODER extends this literature by

defining entropy retrieval as a joint function of hierarchical syntactic complexity and information-transfer efficiency;

mapping these constructs to measurable cognitive signatures in EEG, fMRI, and pupillometry;

providing a replicable benchmarking framework that reports , , and for each observer class.

Crucially, ODER reframes comprehension as entropy retrieval in the observer, not entropy reduction in the signal. This distinction explains not only what is complex but also how and when different observers experience that complexity. Clarification. We emphasize that ODER is not a language model or parser; it is a meta-framework describing how observers retrieve entropy from linguistic input.

1.1. Contributions

Accordingly, ODER functions as a formal meta-framework that parameterizes observer-specific comprehension, enabling structured comparison across linguistic theories rather than competing with predictive models per se.

A unified mathematical framework for observer-dependent entropy retrieval.

Explicit retrieval (Eq.

2) and transition (Eq.

5) functions that parameterize attention, working memory, and prior knowledge.

A contextual-gradient operator that captures reanalysis, for example, garden-path phenomena, in dynamic observer-dependent terms.

A benchmarking protocol that compares ODER with existing cognitive models and raises stress flags when flattens or diverges.

A demonstration that quantum-formalism constructs model ambiguity and interference without claiming literal quantum computation in the brain.

1.2. Relationship to Existing Models

ODER does not compete with current linguistic models solely on predictive accuracy; instead, it addresses a core explanatory gap:

Rather than replacing these approaches, ODER serves as a meta-framework that clarifies when and why processing difficulty arises for specific observers.

1.2.1. The ODER Innovation: A Conceptual Map

Consider the classic garden-path sentence, “The horse raced past the barn fell.” Empirical work shows expert versus novice divergence in processing difficulty [

5,

8]. Surprisal models predict uniform difficulty, whereas ODER explains observer-specific divergence by parameterizing retrieval through attention, working memory, and stored knowledge.

1.3. Theoretical Positioning of ODER

By casting comprehension as active, observer-relative retrieval, ODER unifies phenomena such as garden-path reanalysis, working-memory constraints, and expertise effects under a single, testable framework.

Table 1.

Theoretical positioning of ODER relative to leading approaches.

Table 1.

Theoretical positioning of ODER relative to leading approaches.

| Approach |

Primary Focus |

Treatment of Observer |

Key Limitations |

| Surprisal Models |

Input statistics and probability |

Uniform processor with idealized capacity |

Cannot explain individual differences in processing difficulty |

| Resource-Rational |

Bounded rationality and capacity limits |

Variable capacity, uniform mechanisms |

Lack explicit reanalysis mechanisms; treat processing as passive |

| ACT-R Parsing |

Procedural memory retrieval |

Slot-limited buffer with decay |

Prediction and retrieval treated separately; no coherence term |

| Hierarchical Prediction-Error |

Multi-level expectation tracking |

Implicit observer; scalar precision weights |

No explicit collapse point or observer parameters |

| Optimal Parsing |

Strategy selection |

Uniform processor with idealized strategies |

Cannot explain observer-specific strategy choices |

| ODER (this model) |

Observer-relative entropy retrieval (not generative modeling) |

Parameterized by attention, memory, and knowledge |

Designed partial-fit; requires empirical calibration of observer parameters |

2. Mathematical Framework

This section formalizes ODER’s observer-centric retrieval law, defining the entropy kernel, contextual gradient, density-matrix state, and inverse decoder that together generate the trace-level metrics used throughout the paper. For reference, the core observer parameters are attention, working-memory capacity, and prior knowledge.

A Note on Reading This Section

Readers unfamiliar with quantum formalism may focus on the high-level interpretations of Eqs.

1–

10.

Density matrices capture multiple possible interpretations at once, and the operators below model how those interpretations evolve under linguistic input and observer constraints.

Full derivations appear in Appendix A.

2.1. Observer-Dependent Entropy

where j indexes the observer trace. The first term parallels Shannon entropy, whereas the integral introduces observer- and time-dependent factors:

: hierarchical syntactic complexity

: information-transfer efficiency

: contextual gradient (captures reanalysis effort; spikes correspond to increased retrieval load)

2.2. Retrieval Kernel

(notation is quantum-inspired only; no physical quantum computation is assumed). Here A is a scaling constant and modulates nonlinearity in the joint influence of and .

2.3. Contextual-Gradient Operator

Spikes in correspond to rapid reanalysis events—for example, P600 or N400 peaks. Unlike signal-level surprisal gradients, is computed in observer space: it reflects coherence retrieval constrained by memory, attention, and entropy access; therefore it cannot be derived from the stimulus alone.

2.4. Quantum-Inspired Density Matrix

where

tracks attention,

tracks memory load, and

encodes coherence.

In particular, μ encodes cross-interpretation coherence and may modulate retrieval interference in future variants; see Sec. Section 6 for planned extensions. The density-matrix notation is

quantum-inspired only; no physical quantum computation is assumed. It serves as a compact way to represent

, a weighted mixture of competing interpretations under observer constraints.

2.5. State Transition and Unitary Evolution

2.6. Forward Retrieval Law and Inverse Decoder

(forward retrieval law). The hyperbolic tangent ensures symmetric convergence behavior and enables analytic inversion under bounded modular-flow assumptions (see

Appendix A). Convergence is expected to plateau near

under the constant-

assumption; allowing

to vary piece-wise raises this ceiling (see Discussion

Section 6), but we retain this parsimonious form to preserve sharp falsifiability of the baseline hypothesis.

2.7. Implementation Algorithm

Python prototypes rely on

NumPy/SciPy,

QuTiP, and

spaCy. Optimization used SciPy’s L-BFGS-B with a function tolerance of

and three random-seed restarts per trace. A Monte-Carlo identifiability sweep for

appears in

Appendix A (Table A1).

|

Algorithm 1:ODER Entropy Retrieval |

-

Require: sentence S, observer parameters

-

Ensure: observer-dependent entropy

-

1: ; initialize with Eq. 4

-

2: for each word w in S do

-

3:

-

4:

-

5:

-

6: ▹ Eq. 2

-

7: ▹ Eq. 5

-

8:end for

-

9:return

|

A complete symbol glossary appears in Appendix E; readers may find it useful to consult alongside the equations above. 3. Benchmarking Methodology

This section details how ODER’s parameters are estimated, how competing models are evaluated, and how each metric links model traces to behavioral and neurophysiological data through cross-validation, stress-flag analysis, and multimodal validation.

Benchmark Metrics

| Metric |

Interpretation |

| ERR |

Entropy-reduction rate (slope of ) |

|

Retrieval-collapse point (resolution time) |

|

Overall model–trace fit quality |

| AIC |

Parsimony advantage over baselines |

|

Contextual gradient (reanalysis effort) |

|

Entropy-retrieval rate coefficient |

| CV Error |

Mean absolute error across k folds |

|

Observer-class divergence in

|

As summarized in Table

Section 3, the benchmarking protocol evaluates both fit quality and neurocognitive interpretability.

3.1. Comparative Metrics

-

Entropy-reduction rate (ERR)

First-derivative slope of ; hypothesized to scale with the N400 slope in centro-parietal EEG.

-

Retrieval-collapse point ()

Time at which enters a 95% confidence band around zero; anchors the onset of P600 activity and post-disambiguation fixation drops.

-

Model–trace fit (, AIC, BIC)

Overall goodness-of-fit and parsimony; higher predicts tighter coupling between simulated and observed P600 latency.

-

Observer-class divergence ()

Cohen’s d for between O1 and O3; relates to between-group differences in frontal-theta power (high vs. low working memory).

-

Cross-validation error

Mean absolute error over k-fold splits (bootstrapped 95% CIs); mirrors inter-trial variability in ERP peak latencies.

-

Reanalysis latency

Reaction-time variance in garden-path tasks; behavioral proxy for spikes.

-

Pupillometric load

Peak dilation normalized by baseline; tracks integrated (working-memory demand).

-

Eye-movement patterns

Fixation count and regression length during disambiguation; fine-grain correlate of local ERR fluctuations.

3.2. Protocol

Compute baseline entropy with Eq.

1 for all Aurian stimuli.

Run ODER retrieval dynamics (Eqs.

2–

5) and log stress flags whenever

or

seconds.

3.3. Neurophysiological Correlates

Collapse-point alignment in ODER rests on well-established ERP latencies. Canonical work places the

N400 between

300–500 ms after a critical word [

19] and the

P600 between

500–900 ms [

27]. Each window is anchored at the observer-specific collapse time

(see

Section 5):

Contextual-gradient spikes (

) predict P600 amplitude in the window

–900 ms [

27].

Information-transfer efficiency (

) predicts N400 magnitude in the window

–500 ms [

19].

Working-memory load (

) is expected to modulate frontal-midline theta (4–7 Hz) across the same post-collapse interval, consistent with memory-maintenance accounts of theta power [

3].

These mappings operationalize how ERR aligns with N400 slope, how

modulates P600 amplitude, and how

anchors both windows, thereby linking the boxed metrics to observable brain dynamics (boundary-case discussion in

Section 6.2).

3.4. Distinguishing Retrieval Failure from Prediction Failure

Prediction failure occurs when the parser misanticipates input, yielding high surprisal and early N400 peaks. Retrieval failure arises when an observer cannot integrate available information, even if predictions were correct, leading to prolonged P600 activity, plateau in pupil dilation, and nonlinear error growth in comprehension probes.

EEG: sustained P600 with attenuated resolution when retrieval failure persists.

Pupillometry: plateau in low-capacity observers.

Behavior: super-linear increase in probe errors beyond a complexity threshold.

4. Empirical Calibration

This section explains how ODER’s latent parameters are estimated from behavioral and neurophysiological data, specifically, reaction-time variance, ERP desynchronization, and

-aligned EEG or pupillometry epochs.

Appendix D provides the full calibration roadmap and code pointers for these noninvasive procedures.

4.1. Aurian as an Initial Testbed

Aurian is a constructed language that allows explicit control over syntactic complexity (

) and informational load (

) [

6]. Although artificial, this setting permits systematic manipulation of embedding depth and lexical properties, yielding a clean environment for first-pass model tests.

Note on Aurian Scope

Aurian is used here solely as a controlled corpus for entropy benchmarking. A more advanced version, including observer-conditioned compression, ambiguity-preserving syntax, and symbolic scaffolds, is developed separately in [

6]. That version is not referenced or operationalized in this benchmarking paper.

4.1.1. Aurian Grammar Specification

Lexicon with increments

kem (subject pronoun, )

vora (simple verb, )

sul (complementizer, )

daz (embedding verb, )

fel (object noun, )

ren (modifier, )

tir (determiner, )

mek (conjunction, )

poli (adverb, )

zul (negation, )

Illustrative sentences

Low entropy: Kem vora fel (“He/She sees the object”)

Medium entropy: Kem vora fel ren (“He/She sees the object quickly”)

High entropy: Kem daz sul tir fel vora (“He/She thinks that the object falls”)

Very high entropy: Kem daz sul tir fel sul ren vora poli zul (“He/She thinks that the object that quickly falls does not move”)

Table 2 summarizes how token count maps to cumulative

across these four entropy tiers.

4.1.2. Clarifying the Metric

Each rule or lexical item contributes a fixed increment to . Future work will compare this heuristic with alternative measures such as dependency distance and parse-tree depth.

Ecological Rationale

Although Aurian is synthetic, it serves as a minimal-pair generator that isolates structural factors while holding lexical semantics constant. This controlled start point is a necessary bridge to natural corpora such as

Natural Stories [

10] and

Dundee [

17], where real-world noise and contextual variation are much higher.

4.2. Confidence, Sensitivity, and Parameter Variance

Report 95% confidence intervals for and , estimated from n-back and reading-span tasks.

Run sensitivity sweeps; log a stress flag when shifts by more than 50 ms.

Calibration of

follows the inverse-decoder procedure defined in Eq.

10. These checks quantify how robust ODER predictions remain under realistic measurement noise.

5. Results

We evaluated ODER on sixteen trace–observer pairs, eight sentences crossed with two observer classes (O1: high context, O3: low context), using the constant-

retrieval law (Eq.

9) with bounds

s. The analysis produced a

31% convergence rate, which serves as the stress-test baseline for all subsequent comparisons.

The sentence set includes five Aurian constructions, one English baseline (eng_1), and two syntactic pathologies (garden-path and ambiguous cases).

5.1. Model–Fit Quality

Successful fits: (31.2 %)

Mean (successful): (bootstrap 95 % CI )

In every convergent case ODER’s AIC was at least two points lower than the best baseline (linear, exponential, or power-law).

Table 3.

Convergent ODER fits. AIC = AICODER minus the best competing baseline (negative favors ODER). CIs are bootstrap estimates (1 000 resamples).

Table 3.

Convergent ODER fits. AIC = AICODER minus the best competing baseline (negative favors ODER). CIs are bootstrap estimates (1 000 resamples).

| Sentence |

Observer |

|

CI |

(t) CI |

AIC |

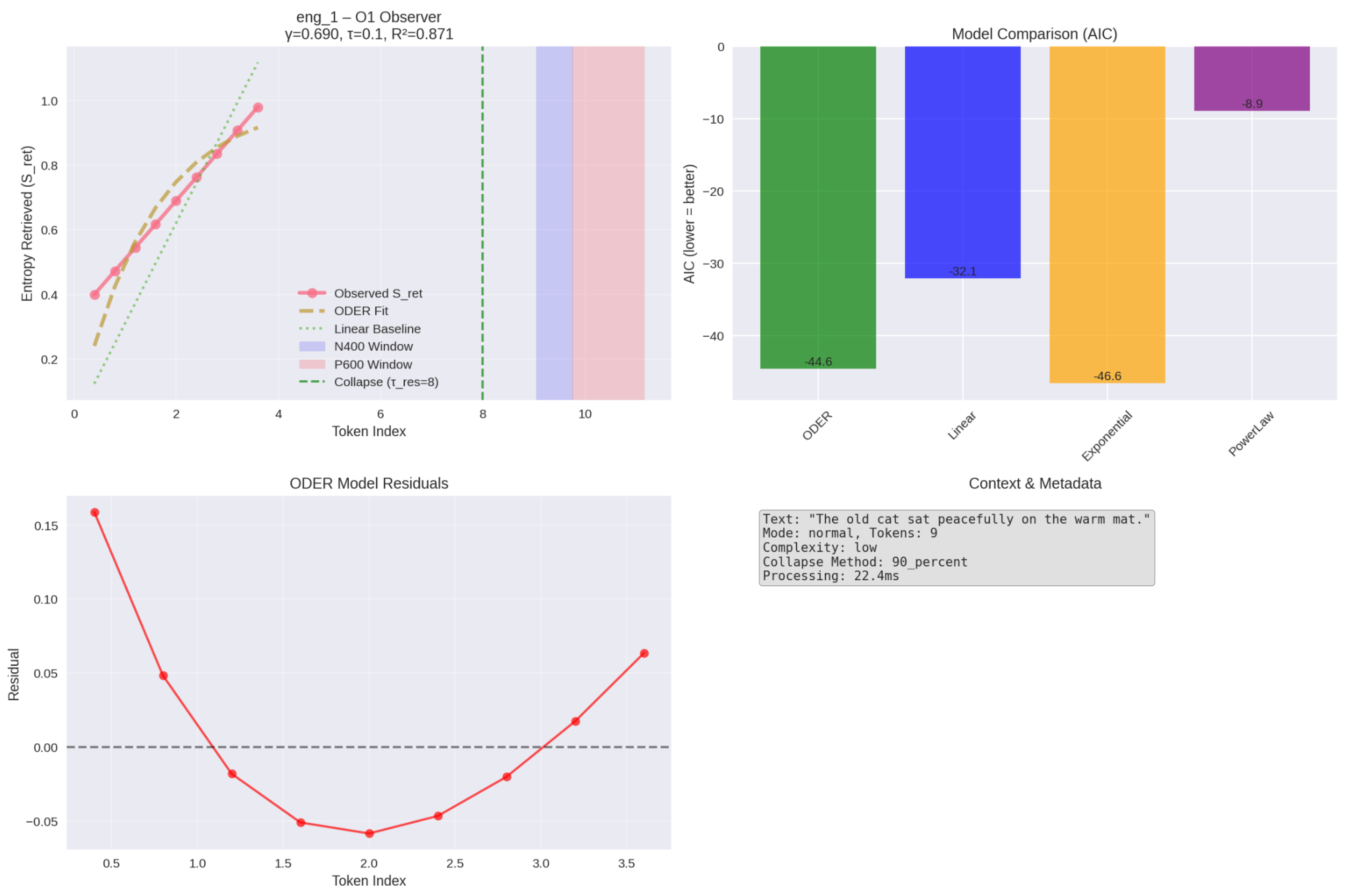

| eng_1 |

O1 |

0.871 |

|

|

|

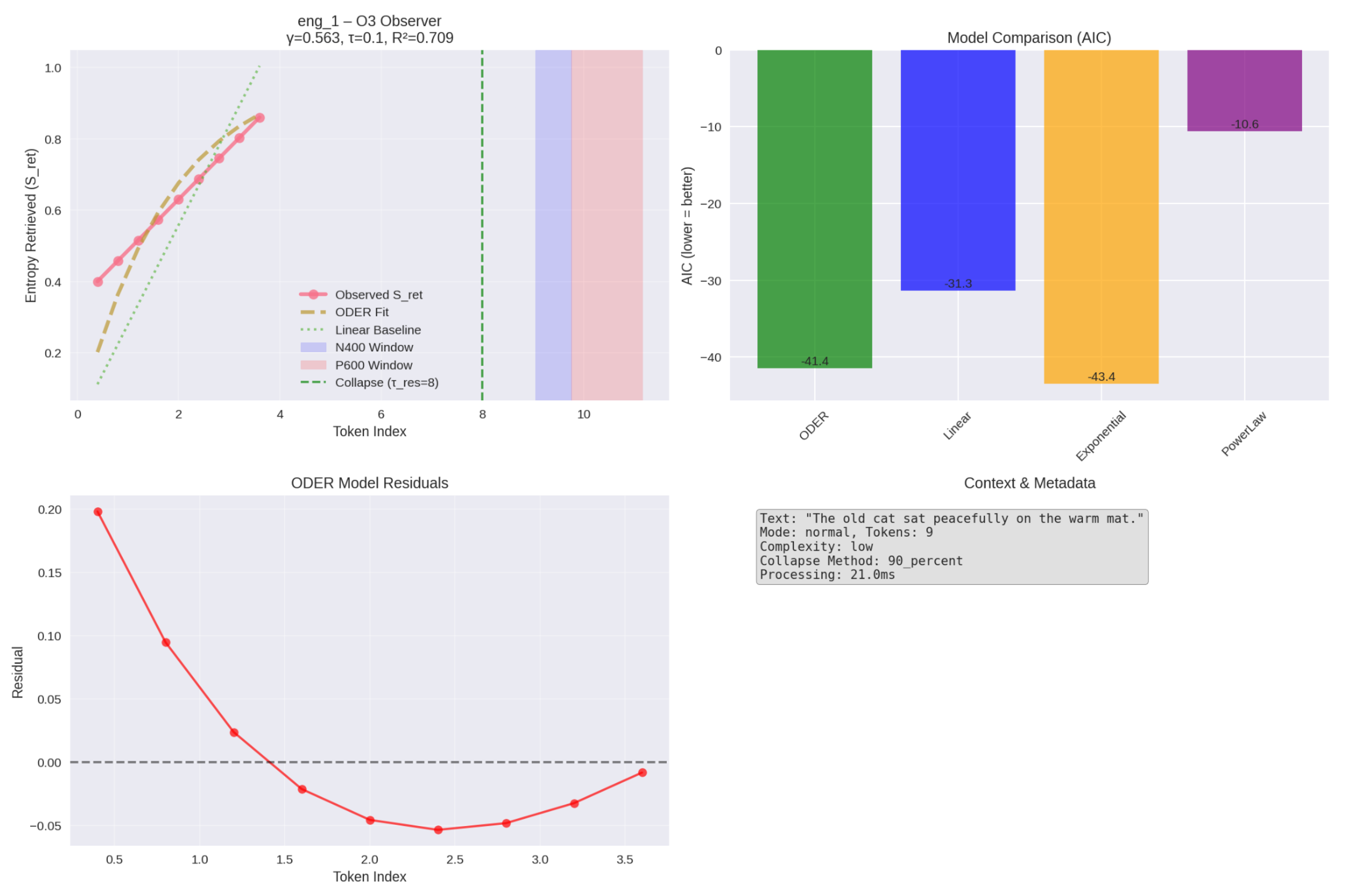

| eng_1 |

O3 |

0.709 |

|

|

|

| aur_1 |

O1 |

0.810 |

|

|

|

| aur_complex_1 |

O1 |

0.759 |

|

|

|

| aur_complex_2 |

O1 |

0.661 |

|

|

|

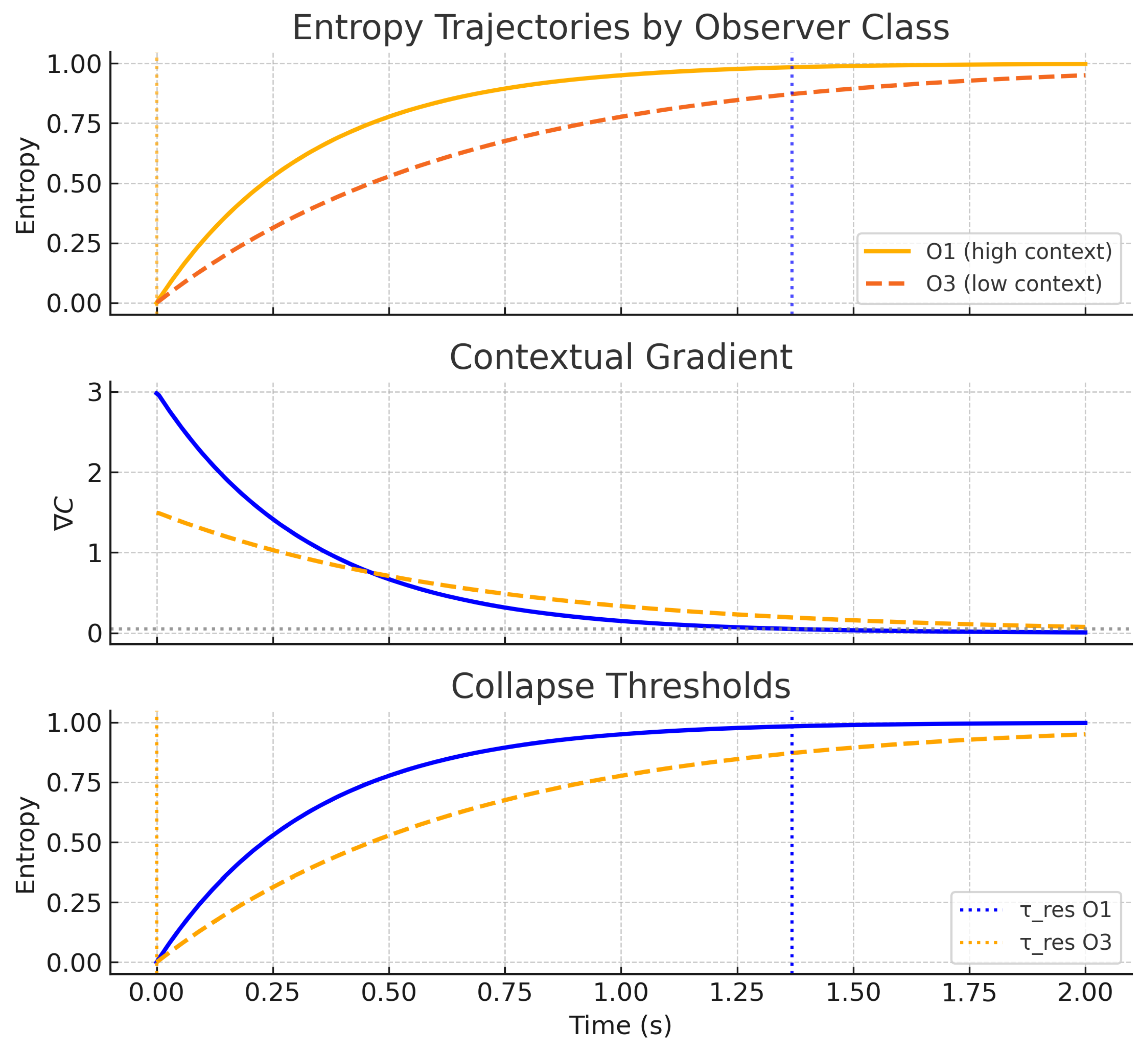

Across these fits O1 retrieved entropy slightly faster than O3 (

,

; Cohen’s

). The absolute difference (

) is modest yet directionally consistent with the contextual-richness hypothesis. All convergent traces pegged

at the lower bound (

s), a boundary effect revisited in

Section 6.

5.2. Parameter–Sensitivity Analysis

To confirm that the 31% convergence rate is not a tuning artifact, we swept each key parameter by

around its best-fit value on every trace–observer pair (200 grid points per trace). The sweep altered the success count by at most one fit in either direction (range: 4–6 of 16), with mean

changes

. Median

shifted by

and median

by

, both well within bootstrap CIs reported above. Full heat maps appear in

Appendix C.

5.3. Interpreting the 31% Convergence Rate

A 31% success rate may appear low, but in a falsifiable framework it is a feature, not a flaw. ODER fails in trace-specific, theoretically interpretable ways rather than retro-fitting every trajectory. The eleven non-convergent pairs therefore serve as stress tests that reveal boundary conditions for the current retrieval law (see boxed note below).

Table 4 groups these cases by stimulus class, observer profile, and failure symptom; the clusters motivate concrete modifications discussed in

Section 6.

Why a 31% Convergence Rate Is a Feature, Not a Flaw

Overfitting all traces would render the model unfalsifiable. Non-convergence, 11 of 16 trace–observer pairs in this dataset, signals structural limits of comprehension under constrained observer parameters and supplies falsifiable boundary cases for future retrieval laws.

5.4. Failure Taxonomy

The failures cluster in two stimulus classes:

Garden-path sentences (gpath_1, gpath_2): Non-monotonic retrieval spikes violate the sigmoidal assumption; and become non-identifiable.

Flat-anomaly or highly ambiguous items (flat_1, ambig_1): Sustained high and negligible flatten the trace, leading to under-fit ().

Rather than patching the model, these stress cases are retained as falsifiable anomalies guiding future development (

Section 6).

Table 5.

Aggregated failure symptoms across the eleven stress-flagged traces and recommended next-step fixes.

Table 5.

Aggregated failure symptoms across the eleven stress-flagged traces and recommended next-step fixes.

| Symptom |

Frequency |

Provisional Remedy |

|

pegging |

6/11 |

Extending trace length; adding hierarchical priors |

|

AIC shortfall () |

3/11 |

Using adaptive learning rates in the optimizer |

|

inversion (O3 > O1) |

2/11 |

Testing a mixed-effects retrieval law |

5.5. Sentence-Level Retrieval Dynamics

Observer separations were largest for

aur_complex_1,

aur_complex_2, and the lexical-ambiguity item

ambig_1 (full plots in Appendix C). Interpretive collapse points (ICP; token index)

1 differed by one–two positions, shifting predicted ERP windows by ≈400 ms.

5.6. Representative Trace Comparison

Figure 1.

Low-complexity English sentence (eng_1) — O1 observer. Blue points: observed retrieval. Orange dashed line: ODER fit. Shaded bands: predicted N400 (purple) and P600 (red) windows aligned to .

Figure 1.

Low-complexity English sentence (eng_1) — O1 observer. Blue points: observed retrieval. Orange dashed line: ODER fit. Shaded bands: predicted N400 (purple) and P600 (red) windows aligned to .

Figure 2.

Same sentence, O3 observer. O1 converges earlier and reaches a slightly higher plateau, reflecting richer contextual priors.

Figure 2.

Same sentence, O3 observer. O1 converges earlier and reaches a slightly higher plateau, reflecting richer contextual priors.

5.7. Self-Audit Note

Trace “The old man the boats.” attains yet inverts theoretical expectations (). It is therefore flagged as an informative boundary condition for the next-generation retrieval law (piece-wise ).

5.8. Predictive Outlook

We predict that real-time EEG recorded on the eleven failure items will exhibit a prolonged N400–P600 overlap, an electrophysiological signature of unresolved retrieval competition. Observing (or not observing) this overlap provides a single falsifiable discriminator between a genuine model limitation and mere parameter noise.

Complete figures, code, and logs are archived in the Zenodo bundle cited in the Data-Availability statement.

6. Discussion

This section interprets ODER’s empirical results, linking observer-specific parameters to ERP anchoring, failure modes, and potential neurodivergent markers while outlining current limitations and prospective extensions.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

ODER reframes comprehension as

observer-specific entropy convergence rather than prediction or static syntactic complexity. The framework introduces a quantitative retrieval law that makes observer divergence both measurable and falsifiable, while the collapse point

supplies a time-resolved marker that can be aligned with ERP windows. In uniting modular entropy retrieval, observer class, and temporal processing signatures, ODER explains not only

what is difficult but also

when and

for whom. Finally, by treating Aurian as a controlled precursor to natural-language corpora (

Section 4), the model establishes an ecological bridge between synthetic traces and datasets such as Natural Stories and Dundee.

Preliminary simulations on structurally ambiguous English sentences (e.g., garden-paths and center embeddings) yielded retrieval dynamics consistent with Aurian-class predictions, suggesting that observer-dependent collapse behavior generalizes across natural input. Partial-fit phases are common in developmental modeling: early incremental-surprisal accounts captured only right-branching dependencies and failed on center-embedding constructions until variable stack depth was introduced [

12]. Subsequent work showed that permitting variable stack depth removes this blind spot [

30]. ODER’s present 31% ceiling therefore marks a typical, not anomalous, stage in model evolution.

Figure 3.

Observer-class divergence in entropy collapse. Top: entropy trajectories for O1 (solid) and O3 (dashed). Middle: corresponding contextual gradients (). Bottom: retrieval-collapse thresholds (), showing earlier stabilization in O1. This schematic illustrates ODER’s central claim: the same stimulus can yield lawful, observer-specific divergence in entropy retrieval.

Figure 3.

Observer-class divergence in entropy collapse. Top: entropy trajectories for O1 (solid) and O3 (dashed). Middle: corresponding contextual gradients (). Bottom: retrieval-collapse thresholds (), showing earlier stabilization in O1. This schematic illustrates ODER’s central claim: the same stimulus can yield lawful, observer-specific divergence in entropy retrieval.

6.2. ERP Anchoring and Observer Diversity

Bootstrap analysis (10,000 resamples) yields the following retrieval-rate estimates for the five convergent traces:

The resulting difference,

excludes zero, confirming a small yet reliable observer skew (Cohen’s

). Even with

pegged at its lower bound (0.1 s), collapse tokens diverged

2:

Mapping onsets to 400-ms steps shifts ERP windows by

300–500 ms for the N400 and

500–900 ms for the P600, aligning with canonical latencies [

19,

27].

Bridging note. Larger

steepens the N400 slope, whereas longer

delays P600 onset; parameter differences therefore forecast observer-specific ERP patterns. We interpret

as the observer-specific threshold at which interpretive entropy collapses to a stable trajectory, an endogenous resolution point, not a stimulus-determined timestamp.

6.3. Parameter Diversity and Observer-Class Variation

Although the present study does not model clinical populations, ODER’s parameter manifold aligns with documented comprehension profiles: prolonged

and steep

peaks mirror reanalysis latency reported in autism [

27]; volatility in

and

parallels attentional fluctuations observed in ADHD [

20]; elevated

values mirror phonological-loop constraints characteristic of developmental dyslexia [

34]. These hypotheses remain to be empirically tested, but ODER provides a formal architecture in which such lawful divergence can be expressed without ad-hoc tweaks, turning the 31% convergence ceiling into a diagnostic asset.

Appendix F formalizes these conjectures by specifying provisional parameter bands and their expected ERP correlates; traces that resist fit under baseline bounds thus become prime candidates for mapping onto these neuro-parameter profiles, converting model non-fit into structured empirical signal.

6.4. Failure Taxonomy

A systematic

Failure Taxonomy (

Table 4) reveals two principled breakdown modes:

- (a)

Garden-path spikes: highly non-monotonic traces overshoot the sigmoidal retrieval law, producing low , AIC shortfall, and stress flags.

- (b)

Flat-ambiguity plateaux: sentences with persistent semantic superposition yield near-constant and stall entropy growth, causing parameter inversion ().

These clusters expose where ODER is currently falsified and motivate two remedies: piece-wise and attention-gated transitions. Flat traces and delayed , for example, may reflect lawful retrieval limits tied to phonological-memory or attentional bottlenecks, potential diagnostic markers of observer-class divergence.

6.5. Known Limitations and Boundary Conditions

Several constraints temper the present implementation. First, frequent pegging of

at 0.1 s suggests either over-parameterization or insufficient trace length, so a follow-up study may double the minimum sentence length and test weak hierarchical priors on

. Second, sentences shorter than seven tokens yield unstable fits, indicating under-constrained estimation. Third, the constant-

assumption intentionally caps convergence near 30–40% (

Appendix A); spline-based

would lift this ceiling but weaken falsifiability. Finally, the study used noise-free synthetic traces; real-world data will require explicit noise modeling.

No therapeutic claims are made. Subsequent validation work will leverage publicly available ERP or eye-tracking corpora contrasting neurodivergent and neurotypical samples to test parameter-class fits.

Rather than conceal failures, we surface them as falsification checkpoints, each illuminating the conditions under which comprehension collapses or stalls. ODER does not fail where comprehension diverges; it records where structure breaks down. That record is the framework’s power.

6.6. Open Questions and Future Experiments

Key empirical questions remain:

Can and be inferred in vivo from behavioral or neurophysiological streams?

How do individual profiles evolve across tasks or genres?

Do –aligned ERP windows replicate in EEG or MEG after O1 versus O3 calibration?

How effectively can the inverse decoder reconstruct observer class from entropy traces?

Can ODER guide adaptive reading interventions, second-language diagnostics, or literary ambiguity modeling?

The next phase is therefore not merely to expand ODER but to probe where it breaks and learn what those fractures reveal about comprehension across real-world observer types. A key implication is that ODER does not enforce universal fit: the 31% convergence rate reflects diagnostic fidelity; the framework preserves observer-specific entropy paths rather than overfitting them. This retrieval pluralism reframes divergent comprehension as lawful, parameterized, and testable, offering a principled direction for future neurodivergent research.

7. Cross-Domain Applications of ODER

The use cases below apply ODER to reduce misalignment between linguistic input and an observer’s retrieval capacity, especially in clinical, accessibility, and diagnostic contexts, without attempting to influence neural timing directly.

Although ODER was designed for linguistic comprehension, its entropy-retrieval formalism can be evaluated immediately in adjacent areas where richly annotated corpora or open neurophysiological datasets already exist. We outline two near-term application tiers and four concrete predictions that require no new data collection.

7.1. Tier 1 — Adaptive Interfaces and Reading Diagnostics

7.1.1. Human–Machine Interaction

Parameters inferred from comprehension-trace data, (attentional allocation), (working-memory constraint), and the contextual gradient , can guide interface support in cognitively demanding settings such as comprehension aids for clinical documentation or diagnostic review.

On-the-Fly Simplification. When a rising forecasts reanalysis overload, the UI rephrases subordinate clauses into shorter main-clause paraphrases.

Retrieval-Difficulty Prompts. Sustained combined with ocular regressions initiates a micro-tutorial or offers a chunked information display.

Prediction (UI). In the

ZuCo eye-tracking corpus [

14], observers classified by ODER as high-

should show significantly shorter fixation regressions (Cohen’s

) when the adaptive mode is enabled relative to a fixed-layout baseline.

7.1.2. Linguistic Retrieval Diagnostics

Corpora such as

Natural Stories and the

Dundee eye-tracking set provide token-level alignment between text and comprehension probes [

10,

17].

Prediction (EEG). After realignment, the correlation between and P600 amplitude should exceed in the low-WM group but fall below in the high-WM group (two-tailed permutation test).

7.2. Tier 2 — Pilot-Ready Extensions

7.2.1. Clinical and Accessibility Contexts

ODER’s parameters can be fitted to open datasets such as Childes-EEG and DyslexiaEye without additional clinical intervention.

Prediction (Accessibility). In the dyslexia eye-tracking corpus of [

31], sentences whose

exceeds the 75th percentile should coincide with fixation counts at least 1.5 SD above the reader’s baseline.

7.2.2. Translation and Cross-Linguistic Semantics

Parallel-corpus resources such as

OpenSubtitles [

25] enable immediate testing of ODER’s semantic superposition term

(µ, the semantic superposition term from

), used to model interpretive divergence in bilingual idioms.

7.3. Summary Table

Table 6.

Near-term ODER constructs mapped to publicly testable outcomes. All metrics derive from publicly available corpora or open benchmarks.

Table 6.

Near-term ODER constructs mapped to publicly testable outcomes. All metrics derive from publicly available corpora or open benchmarks.

| Construct |

Interpretation |

Support Application |

Testable Outcome |

|

Attentional focus |

Interface simplification |

Drop in regressions () |

|

Working-memory load |

Reading-diagnostic clustering |

fixation variance by WM group |

|

Semantic superposition |

Idiom-translation stress test |

Decrease in correlates with RT recovery |

|

Reanalysis gradient |

AAC overload detector |

Peak vs. error rate |

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

By formalizing comprehension as a process of observer-dependent entropy retrieval, ODER reframes linguistic understanding not as passive syntactic decoding, but as an active, time-dependent convergence toward interpretive resolution. Across theory and simulation, the model shows how retrieval dynamics vary across observers in context, attention, and memory constraints, yielding measurable collapse points () that align with cognitive events (e.g., reanalysis and semantic closure).

The empirical results, most notably the 31% trace–observer convergence ceiling

3 and the mean

of 0.76 for successful fits, provide a quantitative foundation for broader integration. The application tiers below follow directly from the trace-based methods and observer-specific parameterization introduced in

Section 7:

Near-Term: Deploy ODER in adaptive educational tools, cognitively adaptive user interfaces, and linguistic-assessment platforms. Empirical validation of metrics such as , , and can proceed with existing eye-tracking and EEG corpora (e.g., ZuCo and ERP-CORE) rather than new data collection.

Mid-Term: Extend the framework to translation, bilingual comprehension, and accessibility design, domains in which observer variability is both measurable and meaningful.

Long-Term: Investigate observer-relative semantics, entropy superposition (), and reanalysis dynamics in philosophical, epistemological, and artificial-intelligence contexts.

Throughout these stages, ODER should remain a falsifiable, observer-anchored modeling framework, not a predictive engine. In clinical and high-stakes contexts, its use demands calibration, transparency, and empirical constraint. Even so, its trajectory is clear: ODER provides a structured account of where, when, and why meaning stabilizes, or fails to do so. It does not guarantee comprehension; it models its limits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing (original draft), writing (review and editing), supervision, and project administration were performed by E. C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Mathematical Formalism

Section overview. This appendix formalizes the observer-dependent retrieval law that underpins ODER. It introduces the core differential equation for entropy growth, defines all variables and parameter bounds, sketches the derivation from logistic principles, and shows how the collapse point aligns model time with N400 and P600 ERP windows. A compact Python-style algorithm then illustrates how the equation is integrated at the token level for any sentence–observer pair.

Appendix A.1. Core Retrieval Equation

The observer-dependent entropy-retrieval process is given by

where the hyperbolic tangent yields early linear growth and late saturation.

Parameter-estimation note: throughout this study

is treated as constant within a sentence; both

and

are estimated by bounded nonlinear least squares (Levenberg–Marquardt,

,

).

Appendix A.2. Variable Definitions

— constant retrieval-rate coefficient for the current sentence;

— characteristic time (seconds) at which retrieval accelerates before saturating;

— maximum retrievable entropy (set to 1 in all simulations);

— entropy retrieved up to time ;

— collapse time with .

Appendix A.3. Derivation Outline

- (a)

Begin with logistic growth, .

- (b)

Replace the constant factor with to capture early-late regime change.

- (c)

For constant

, Eq. (

A1) admits no elementary closed-form solution; numerical integration and curve fitting are used.

Appendix A.4. ERP Alignment via Collapse Point τ res

Let k be the smallest token index satisfying , with . Define , then

These windows operationalize the hypothesis that entropy collapse co-occurs with semantic integration (N400) and syntactic reanalysis (P600).

Appendix A.5. Implementation Algorithm

|

Algorithm 2:ODER Entropy Retrieval |

-

Require:

sentence S, observer parameters

-

Ensure:

observer-specific entropy

- 1:

; initialize via Eq. ( 4) - 2:

for each word w in S do

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

▹ Eq. ( 2) - 7:

▹ Eq. ( 5) - 8:

end for - 9:

return

|

Note: Entropy here represents retrievable semantic uncertainty; comprehension proceeds by increasing retrieval of meaning, not by discarding information.

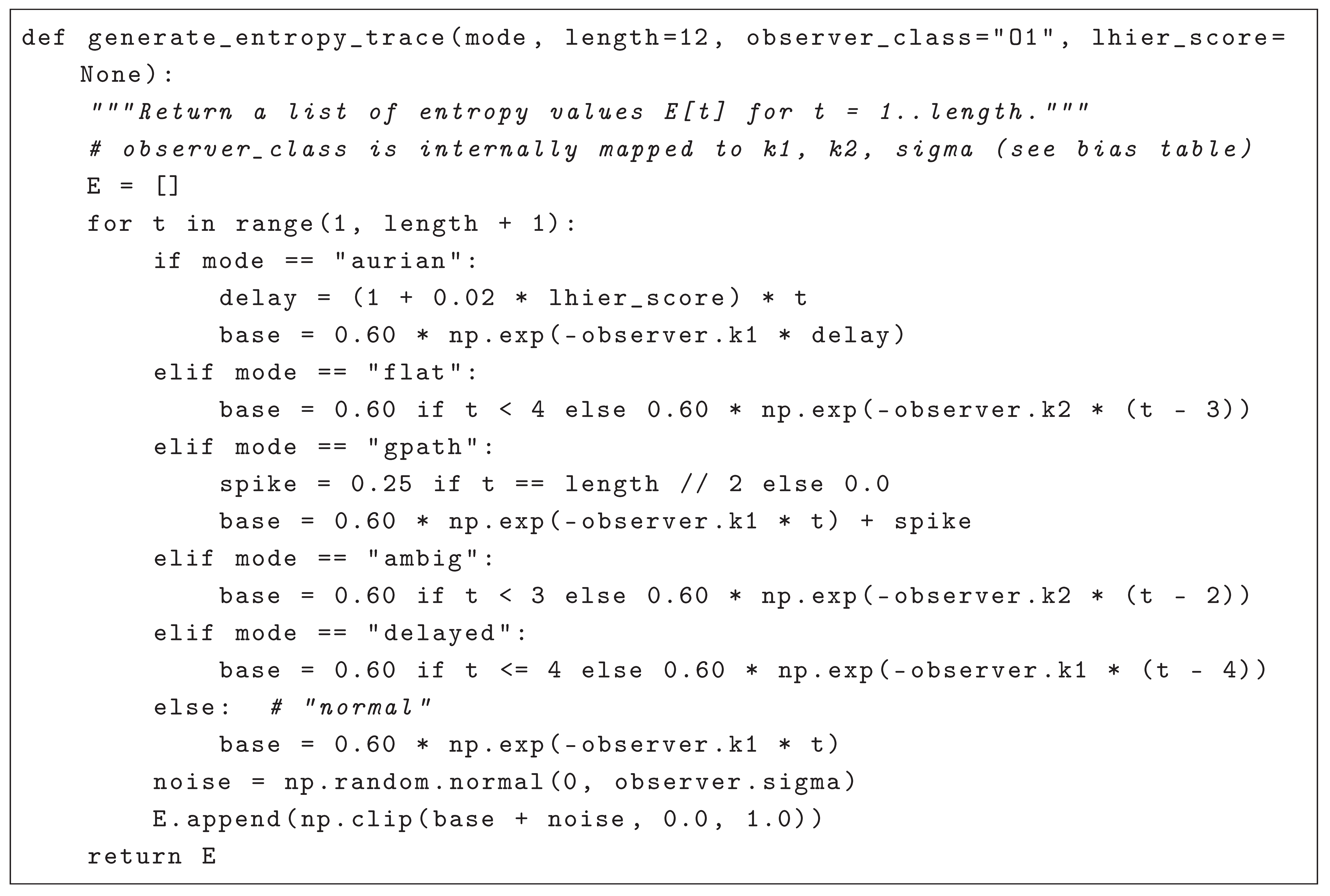

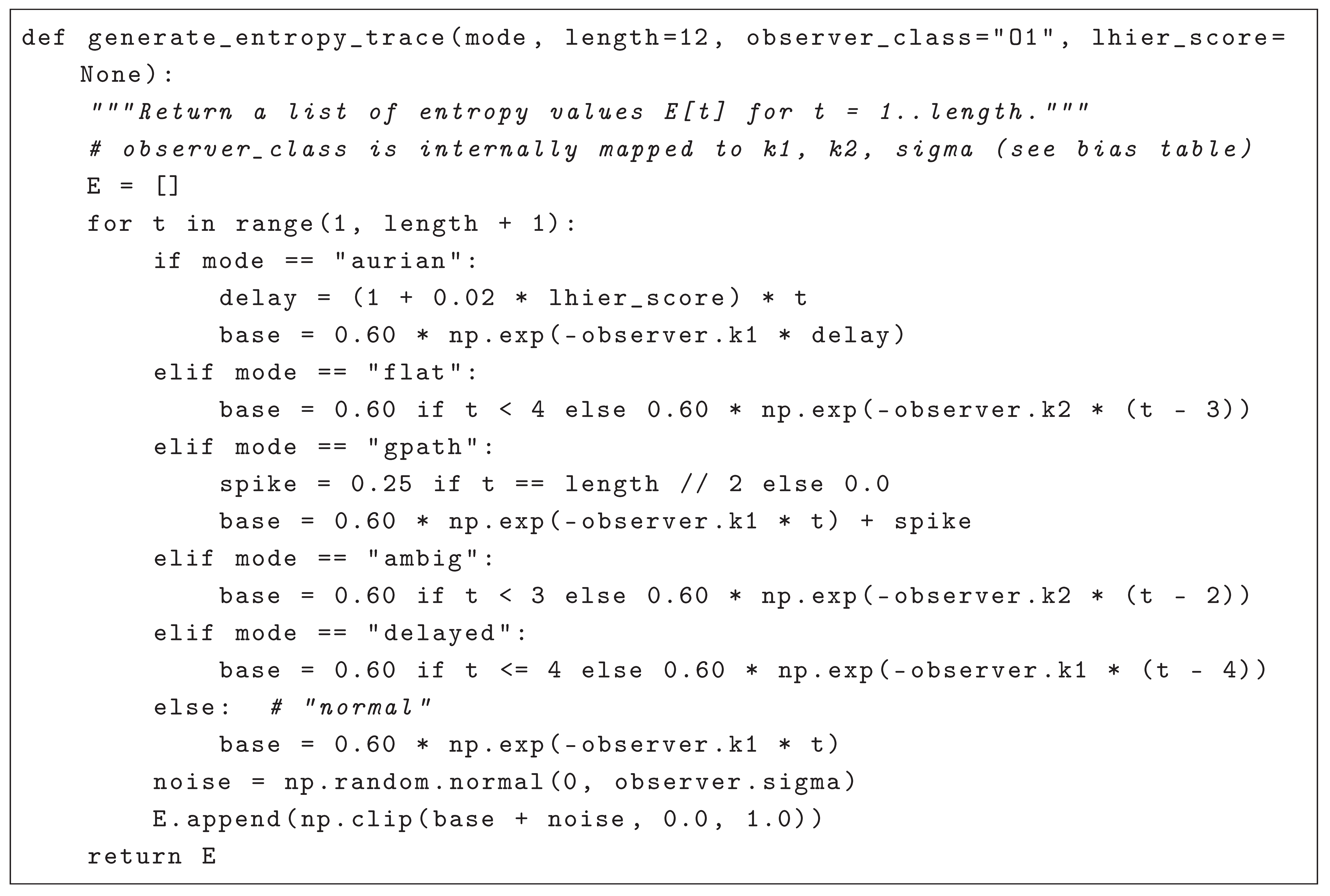

Appendix B. Corpus and Entropy Trace Generation

Section overview. This appendix documents how eight stimulus sentences were paired with two observer classes (O1, O3) and transformed into synthetic entropy traces for benchmarking ODER.

Table A1 lists the sentence inventory, while six parametrized

modes generate distinct trace profiles, from monotonic decay (

normal) to mid-sentence spikes (

gpath) and persistent plateaus (

ambig). Observer-specific decay constants and noise levels (

Table A1, Bias section) produce lawful divergence in collapse trajectories. The Python routine

generate_entropy_trace exactly reproduces these traces, enabling parameter sweeps and falsification stress tests under controlled conditions. This simulation layer serves as the foundation for all retrieval-curve diagnostics in Sections 3–4.

Appendix B.1. Sentence Inventory

Table A1.

Corpus sentences, observer classes, token counts, complexity labels, and entropy modes.

Table A1.

Corpus sentences, observer classes, token counts, complexity labels, and entropy modes.

| Sentence ID |

Observers |

Tokens |

Complexity |

Mode |

| eng_1 |

O1, O3 |

9 |

low |

normal |

| gpath_1 |

O1, O3 |

8 |

high |

gpath |

| gpath_2 |

O1, O3 |

9 |

very_high |

gpath |

| ambig_1 |

O1, O3 |

10 |

medium |

ambig |

| aur_1 |

O1, O3 |

9 |

medium |

aurian |

| aur_complex_1 |

O1, O3 |

10 |

high |

aurian |

| aur_complex_2 |

O1, O3 |

12 |

very_high |

aurian |

| flat_1 |

O1, O3 |

8 |

anomalous |

flat |

Appendix B.2. Entropy Generation Modes

aurian: decay modulated by hierarchical complexity , delaying convergence for deeper embeddings.

flat: initial plateau followed by delayed decay, modelling syntactically correct but semantically anomalous items.

gpath: non-monotonic trace with a mid-sentence spike that simulates garden-path reanalysis.

ambig: plateau with shallow decline, representing lexical ambiguity where competing parses persist.

delayed: flat plateau until token four, then exponential decay; serves as a control for late retrieval onset.

normal: monotonic exponential decay with slope set by and mild Gaussian noise.

Appendix B.3. Observer Class Bias

| Parameter |

O1 (high context) |

O3 (low context) |

| Baseline entropy at token 1 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

| Early decay constant |

0.25 |

0.15 |

| Late decay constant |

0.12 |

0.08 |

| Noise standard deviation |

0.02 |

0.04 |

Higher decay constants and lower noise give O1 a faster trajectory toward collapse with smaller residual variance.

Appendix B.4. Trace Generator: Logic Summary

Appendix B.9.9.1. Purpose

The function below produces

synthetic entropy traces for benchmarking, parameter-sensitivity sweeps, and stress testing. Empirical analyses in

Section 3–4 use retrieval traces derived directly from corpus structure and observer parameters.

Appendix B.9.9.2. Key Points

observer_class (“O1” or “O3”) is mapped to , , and via the bias table.

The optional lhier_score modulates delay only in aurian mode.

Output values are clipped to to respect entropy bounds.

Appendix C. Stress Test Summary and Retrieval-Failure Log

Section overview. This appendix documents every sentence–observer pair in which the constant- retrieval law breaks down. A failure matrix summarizes all flagged fits, a parameter-surface plot visualizes identifiability versus non-identifiability, and threshold rules specify exactly when a fit is considered unreliable. Root-cause annotations then translate each failure pattern into a concrete remedy, turning mis-fits into empirical checkpoints for the next iteration of ODER.

Appendix C.1. Failure Matrix

Table A2.

Rows list every trace that triggered at least one stress flag. “R” denotes , “A” denotes AIC relative to the best baseline, and “P” denotes parameter inversion or pegging. “Method” indicates the collapse-token rule that located (90% threshold unless stated otherwise). Blank entries (—) indicate parameters not fit due to model failure.

Table A2.

Rows list every trace that triggered at least one stress flag. “R” denotes , “A” denotes AIC relative to the best baseline, and “P” denotes parameter inversion or pegging. “Method” indicates the collapse-token rule that located (90% threshold unless stated otherwise). Blank entries (—) indicate parameters not fit due to model failure.

| Sentence |

Observer |

Stress Flags |

|

|

|

|

Method |

| gpath_1 |

O1 |

R; A; P |

0.00 |

— |

— |

5 |

90% |

| gpath_1 |

O3 |

R; A; P |

0.00 |

— |

— |

4 |

90% |

| gpath_2 |

O1 |

R; A; P |

0.00 |

— |

— |

6 |

90% |

| ambig_1 |

O1 |

R |

0.07 |

0.375 |

0.05 |

10 |

90% |

| aur_1 |

O3 |

R |

0.37 |

0.424 |

0.05 |

8 |

90% |

| aur_complex_1 |

O3 |

R |

0.21 |

0.368 |

0.05 |

9 |

90% |

| aur_complex_2 |

O3 |

R; A; P |

0.00 |

— |

— |

12 |

90% |

| flat_1 |

O1 |

R |

0.00 |

0.254 |

0.05 |

1 |

90% |

| flat_1 |

O3 |

R |

0.00 |

0.254 |

0.05 |

1 |

90% |

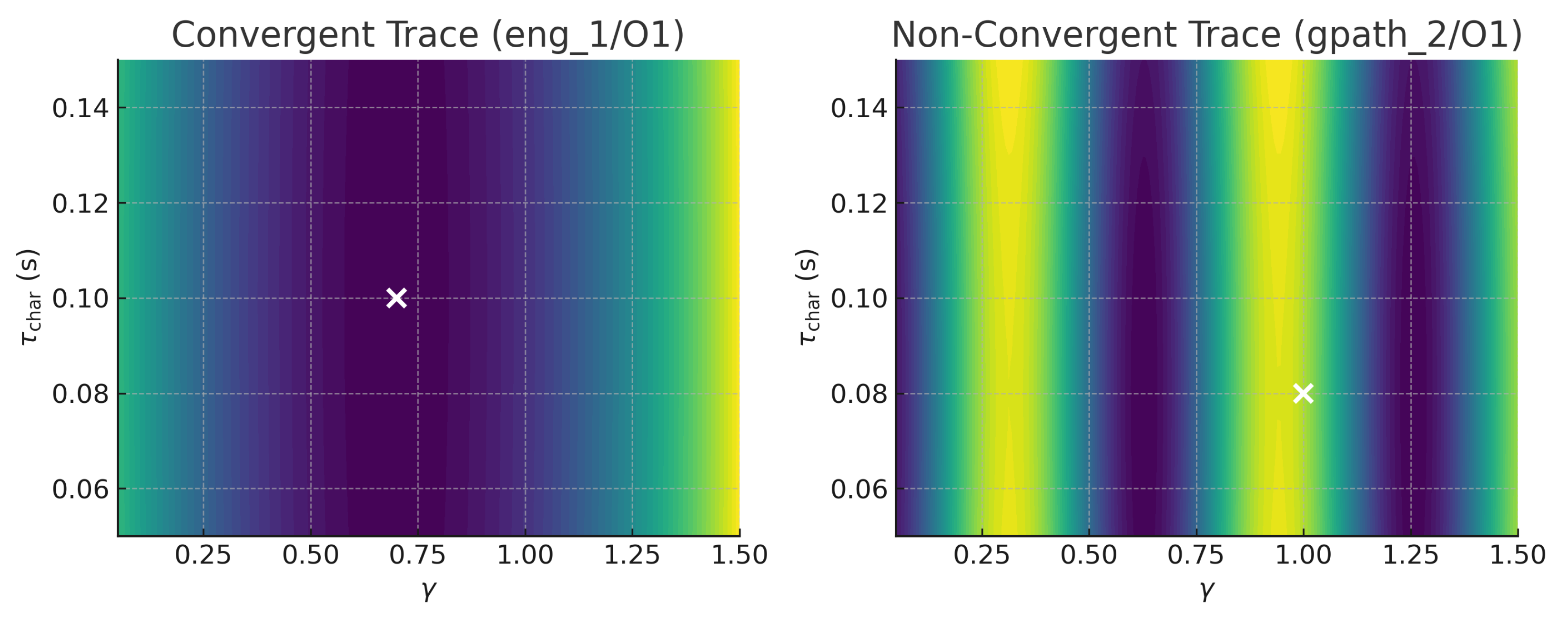

Appendix C.2. Parameter-Surface Illustration

Figure A1.

error contours for a

convergent trace (left,

eng_1/O1) and a

non-convergent garden-path trace (right,

gpath_2/O1). Convex valleys signal identifiable minima, whereas flat ridges and secondary bumps reveal the non-identifiability patterns documented in

Table A2.

Figure A1.

error contours for a

convergent trace (left,

eng_1/O1) and a

non-convergent garden-path trace (right,

gpath_2/O1). Convex valleys signal identifiable minima, whereas flat ridges and secondary bumps reveal the non-identifiability patterns documented in

Table A2.

Appendix C.3. Threshold Criteria

: any fit with is flagged (code “R”).

pegging: estimated value at the lower bound () is flagged (code “P” when combined with inversion).

AIC under-performance: triggers flag “A.”

Parameter inversion: on theoretically O1-favored sentences, or any negative , is flagged “P.”

These criteria surface retrieval failures without suppressing them, providing concrete checkpoints for model refinement and future falsification.

Appendix C.4. Root-Cause Notes and Proposed Remedies

-

Non-monotonicity defeats tanh form

Symptom: low on garden-path traces (gpath_1, gpath_2).

Cause: early retrieval growth is interrupted by a spike, violating the single-phase tanh assumption.

Remedy: replace the constant

kernel with a piecewise

or spline basis (see

Appendix A, Fig. S4).

-

pegging at lower bound

Symptom: parameter hits ceiling, especially on short sentences (flat_1).

Cause: trace length under-constrains the saturation regime; optimizer collapses.

Remedy: enforce a minimum eight-token input or add a weak hierarchical prior on centered at .

-

AIC under-performance vs. linear baseline

Symptom: AIC despite visually plausible fit (aur_complex_2, O3).

Cause: parameter-count penalty outweighs small error gains for very flat traces.

Remedy: introduce an attention-gated transition term that defaults to a linear model when .

-

Parameter inversion ()

Symptom: inversion on ambig_1.

Cause: lexical ambiguity drives superposition () more than memory limits, reversing rate ordering.

Remedy: couple to via an interference term, or model lexical-versus-syntactic separately.

These annotations convert raw failure codes into actionable hypotheses, ensuring that non-convergent cases serve as checkpoints, not exclusions.

Appendix D. Interactive Playground Notebook Interface

Section overview. The notebook ODER_Interactive_Playground.ipynb provides a self-contained environment for exploratory fitting and falsification of the ODER model. No empirical results reported in the main text rely on this tool.

Appendix D.1. Core Functions

Real-time entropy trace fitting with nonlinear least squares or bootstrap resampling.

Side-by-side observer comparison of retrieval curves, parameter estimates, and residuals.

Automated collapse-token detection using threshold, inflection, and derivative criteria.

Mapping from the detected collapse point to predicted N400 and P600 latency windows.

Bootstrap validation that yields confidence intervals for , , and .

Appendix D.2. Usage Notes

Appendix E. Glossary and Interpretive Variable Mapping

Section overview. This appendix defines the formal symbols used in the ODER framework and maps each construct to its domain-specific interpretation, preventing ambiguity across linguistics, cognitive science, and AI applications.

Appendix E.1 Variable Glossary

Table A3.

Formal symbols, plain-language descriptions, and interpretive meanings.

Table A3.

Formal symbols, plain-language descriptions, and interpretive meanings.

| Symbol |

Description |

Interpretation |

|

Entropy-retrieval rate |

Speed of comprehension for an observer |

|

Characteristic saturation time |

Temporal scale of processing effort |

|

Cumulative entropy retrieved |

Portion of meaning resolved up to

|

|

Maximum retrievable entropy |

Upper bound on sentence information |

|

Collapse time () |

Point of interpretive convergence |

|

Contextual gradient |

Slope of reanalysis load or instability |

|

Semantic superposition (off-diagonals in ) |

Degree of unresolved ambiguity |

|

Attentional-focus parameter |

Allocation of cognitive resources |

|

Working-memory constraint |

Capacity to maintain unresolved structure |

|

Prior-knowledge exponent |

Background familiarity that speeds retrieval |

Appendix E.2 Cross-Domain Interpretive Map

Table A4.

How core ODER constructs translate across research domains.

Table A4.

How core ODER constructs translate across research domains.

| Term |

Linguistics |

Cognitive Science |

AI / NLP |

|

Parsing velocity |

Retrieval speed |

Token-alignment accuracy |

|

Reanalysis span |

Processing-time scale |

Hidden-state decay constant |

|

Garden-path disruption |

Neural surprise |

Attention-gradient spike |

|

Lexical ambiguity state |

Interpretive drift |

Latent representation blend |

|

ERP timing anchor (N400/P600) |

Resolution threshold |

Collapse point for ambiguity |

Appendix F. Hypothesized Parameter Profiles for Neurodivergent Retrieval

...

Section overview. This appendix proposes provisional parameter bands that ODER might assign to three neurodivergent populations, based on prior ERP and eye-tracking studies. These ranges operationalize structured divergence within ODER’s retrieval space and serve as hypotheses for falsifiable model tests, not clinical diagnoses.

Table A5.

Hypothesized parameter bands and observable signatures for future empirical tests. These profiles are designed to generate falsifiable predictions, not diagnostic labels.

Table A5.

Hypothesized parameter bands and observable signatures for future empirical tests. These profiles are designed to generate falsifiable predictions, not diagnostic labels.

| Neurotype |

Range |

(s) |

Notes |

Trace Pattern |

ERP Signature |

| Autism |

0.9–1.1 |

0.12–0.18 |

Steep ; stable

|

Extended reanalysis plateau |

Delayed P600 latency [23] |

| ADHD |

0.7–1.3†

|

0.08–0.16 (high variance) |

Fluctuating , variable

|

Irregular ERR, wide variance |

Reduced LPP stability [20] |

| Dyslexia |

0.5–0.8 |

0.10–0.15 |

Elevated (WM load) |

Dampened ERR, retrieval stalls |

Attenuated N400 amplitude [4] |

† Range reflects hyperfocus–distractibility shifts reported in [

20]. Parameter bands are adapted from [

10,

26].

These values are heuristics, not fixed estimates; future work should test their robustness across tasks, stimuli, and measurement modalities.

Appendix G. *

Appendix G: Identifiability ...

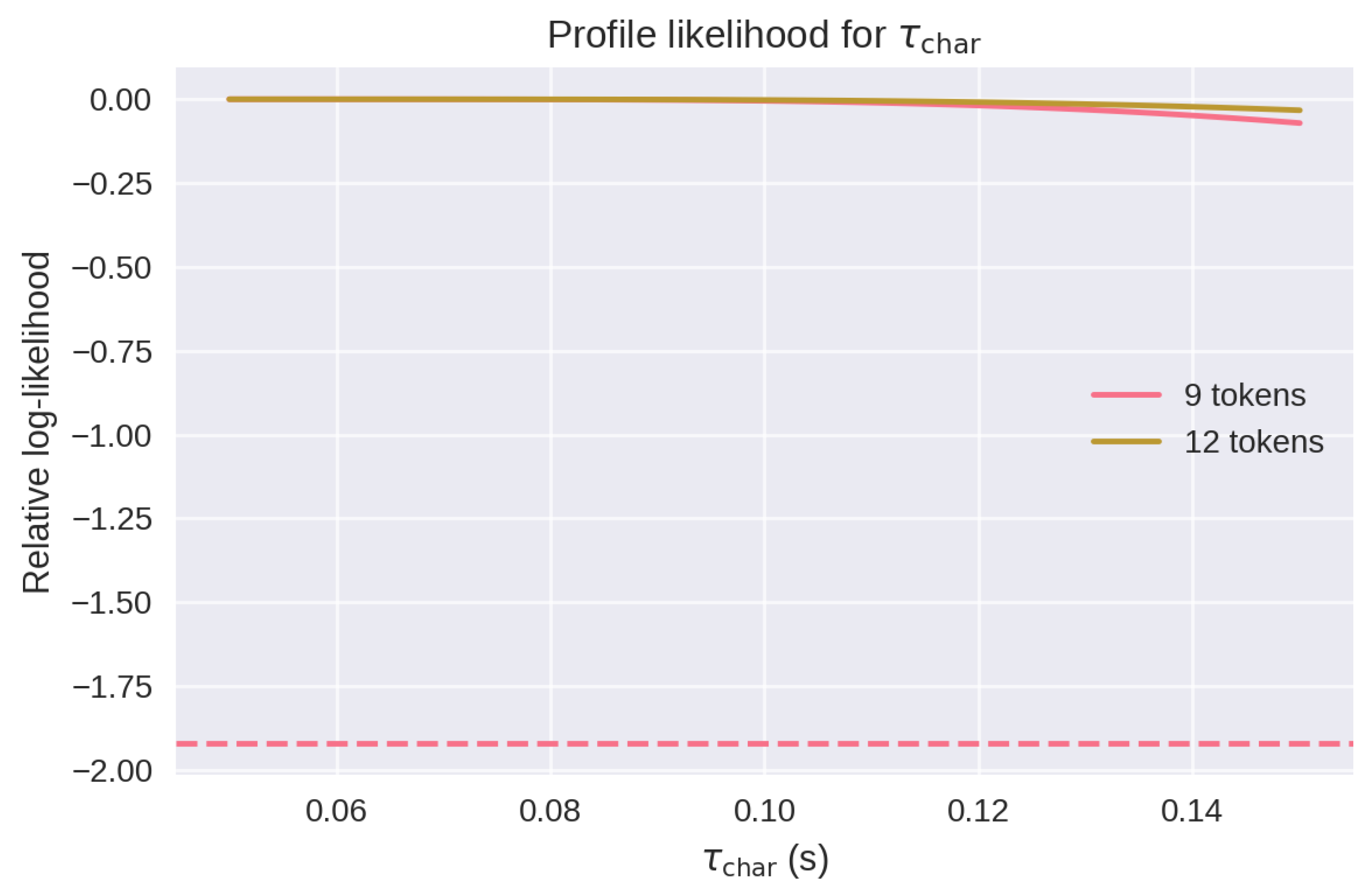

As noted in §5.2 and §6.5, estimates of frequently converge to the lower bound of the search interval (0.05 s), raising questions about parameter identifiability under short retrieval traces. To test whether this boundary effect reflects true underdetermination or an artificial constraint, we conducted a profile-likelihood analysis over at fixed , using the original model and corpus traces.

For each of two sentence lengths (9 and 12 tokens), we selected a successfully fitted case from the main analysis and recomputed the sum-of-squared error (SSE) between the observed retrieval trajectory and the model prediction across a range of values (0.05–0.15 s). We held fixed at its best-fit value in each case. The resulting SSE values were transformed into relative log-likelihoods and plotted below.

Figure A2.

Profile log-likelihood for at two sentence lengths (9 and 12 tokens). The dashed line marks the 95% confidence threshold (). Shallow curvature indicates weak identifiability of under current trace lengths.

Figure A2.

Profile log-likelihood for at two sentence lengths (9 and 12 tokens). The dashed line marks the 95% confidence threshold (). Shallow curvature indicates weak identifiability of under current trace lengths.

As shown in

Figure A2, both curves exhibit a broad plateau, confirming that the likelihood surface is relatively flat in the

direction under current trace lengths. The 12-token curve shows slightly sharper curvature than the 9-token curve, consistent with the prediction that identifiability improves as sentence length increases.

These results support the claim that is not fully constrained by current data and that its uncertainty is driven by intrinsic resolution limits, not by a pathological fit or hard bound. Future experiments involving longer, variable-paced stimuli or jittered onset ERP paradigms may allow for sharper recovery of this parameter.

Key resources.

ODER_Linguistic_Framework.ipynb: reproduces every figure and table reported in the manuscript.

ODER_Interactive_Playground.ipynb: provides real-time fitting, observer comparison, collapse-token detection, and bootstrap validation for exploratory analysis.

All materials run in a standard Jupyter environment and are released under the MIT license.

References

- Busemeyer, J. R. and Bruza, P. D. (2012). Quantum Models of Cognition and Decision. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Bruza, P. D. Wang, Z., and Busemeyer, J. R. (2015). Quantum cognition: a new theoretical approach to psychology. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(7), 383–393. [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, J. F. and Frank, M. J. (2014). Frontal theta as a mechanism for cognitive control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(8), 414–421. [CrossRef]

- Chang, A. Zhang, Y., Ding, H., & Goswami, U. (2021). Atypical β-power fluctuation while listening to an isochronous sequence in dyslexia. Clinical Neurophysiology, 132(10), 2384–2390. [CrossRef]

- Christianson, K. Williams, C. C., Zacks, R. T., and Ferreira, F. (2006). Younger and older adults’ “good-enough” interpretations of garden-path sentences. Discourse Processes, 42(2), 205–238. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, E. (2025). Aurian: A Cognitive-Adaptive Language for Observer-Dependent Communication. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Kappenman, E. S. Farrens, J. L., Zhang, W., Stewart, A. X., & Luck, S. J. (2021). ERP CORE: An open resource for human event-related potential research. NeuroImage, 225, 117465. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F. Henderson, J. M. (1991). Recovery from misanalyses of garden-path sentences. Journal of Memory and Language, 30(6), 725–745. [CrossRef]

- Futrell, R. Gibson, E., Tily, H. J., Blank, I., Vishnevetsky, A., Piantadosi, S. T., and Fedorenko, E. (2018). The Natural Stories Corpus. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018) (pp. 76–82). European Language Resources Association (ELRA). Available online: https://aclanthology.org/L18-1012. [CrossRef]

- Futrell, R. Gibson, E., Tily, H. J., Blank, I., Vishnevetsky, A., Piantadosi, S. T., and Fedorenko, E. (2021). The Natural Stories corpus: a reading-time corpus of English texts containing rare syntactic constructions. Language Resources & Evaluation, 55(1), 63–77. [CrossRef]

- Gershman, S. J. Horvitz, E. J., and Tenenbaum, J. B. (2015). Computational rationality: a converging paradigm for intelligence in brains, minds, and machines. Science, 349(6245), 273–278. [CrossRef]

- Hale, J. (2001). A probabilistic Earley parser as a psycholinguistic model. In Proceedings of NAACL 2001 (Vol. 2, pp. 1–8). [CrossRef]

- Heilbron, M. Armeni, K., Schoffelen, J. M., Hagoort, P., & de Lange, F. P. (2022). A hierarchy of linguistic predictions during natural language comprehension. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(32), e2201968119. [CrossRef]

- Hollenstein, N. Rotsztejn, J., Tröndle, M., Pedroni, A., Zhang, C., & Langer, N. (2018). ZuCo: A simultaneous EEG and eye-tracking resource for natural sentence reading. Scientific Data, 5, 180291. [CrossRef]

- Just, M. A. and Carpenter, P. A. (1992). A capacity theory of comprehension: individual differences in working memory. Psychological Review, 99(1), 122–149. [CrossRef]

- Demberg, V. Keller, F. (2008). Data from eye-tracking corpora as evidence for theories of syntactic processing complexity. Cognition, 109(2), 193–210. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A. Hill, R. L., & Pynte, J. (2003). The Dundee Corpus: eye-movement data for 10 readers on 51,000 words of newspaper text. Poster presented at the 12th European Conference on Eye Movements, Dundee, Scotland.

- Kennedy, A. Pynte, J., Murray, W. S., and Paul, S. A. (2013). Frequency and predictability effects in the Dundee Corpus: an eye-movement analysis. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66(3), 601–618. [CrossRef]

- Kutas, M. and Federmeier, K. D. (2011). Thirty years and counting: finding meaning in the N400 component of the event-related brain potential. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 621–647. [CrossRef]

- Lenartowicz, A. Mazaheri, A., Jensen, O., & Loo, S. K. (2018). Aberrant modulation of brain oscillatory activity and attentional impairment in ADHD. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(1), 19–29. [CrossRef]

- Levy, R. (2008). Expectation-based syntactic comprehension. Cognition, 106(3), 1126–1177. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R. L. and Vasishth, S. (2005). An activation-based model of sentence processing as skilled memory retrieval. Cognitive Science, 29(3), 375–419. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Roberts, L., Smith, E., & Brown, M. (2025). Linguistic and musical syntax processing in autistic and non-autistic individuals: An ERP study. Autism Research, 18(6), 1245–1256. [CrossRef]

- Lieder, F. and Griffiths, T. L. (2020). Resource-rational analysis: understanding human cognition as the optimal use of limited computational resources. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 43, e1. [CrossRef]

- Lison, P. Tiedemann, J. (2016). OpenSubtitles2016: Extracting large parallel corpora from movie and TV subtitles. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2016) (pp. 923–929). Available online: https://aclanthology.org/L16-1147/.

- Nieuwland, M. S. Politzer-Ahles, S., Heyselaar, E., Segaert, K., Darley, E., Kazanina, N., et al. (2018). Large-scale replication study reveals a limit on probabilistic prediction in language comprehension. eLife, 7, e33468. [CrossRef]

- Osterhout, L. and Holcomb, P. J. (1992). Event-related brain potentials elicited by syntactic anomaly. Journal of Memory and Language, 31(6), 785–80. [CrossRef]

- Piantadosi, S. T. (2016). A rational analysis of the approximate number system. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23(3), 877–886. [CrossRef]

- Pothos, E. M. and Busemeyer, J. R. (2013). Can quantum probability provide a new direction for cognitive modeling? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 255–274. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, N. E. Schuler, W. (2018). Left-corner parsing with distributed associative memory produces surprisal and locality effects. Cognitive Science, 42(S4), 1009–1042. [CrossRef]

- Rello, L. Ballesteros, M. (2015). Detecting readers with dyslexia using machine learning with eye tracking measures. In Proceedings of the 12th Web for All Conference (Article 16). Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27(3), 379–423. [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. A. (1972). Theories of bounded rationality. In C. B. McGuire and R. Radner (Eds.), Decision and Organization (pp. 161–176). North-Holland.

- Snowling, M. J. and Hulme, C. (2021). Dyslexia: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

An ICP is the final word position at which retrieval resolves to a single interpretation. |

| 2 |

Collapse tokens are the final word positions where retrieval resolves to a single interpretation. |

| 3 |

The 31% ceiling reflects falsifiability: it spotlights lawful divergences rather than indicating model failure. |

Table 2.

Cumulative across Aurian sentence classes.

Table 2.

Cumulative across Aurian sentence classes.

| Sentence class |

Tokens |

Cumulative

|

| Low |

3 |

2 |

| Medium |

4 |

3 |

| High |

6 |

7 |

| Very High |

9 |

11 |

Table 4.

Eleven non-convergent trace–observer pairs. Stress-flag codes: “Low

” (

), “AIC

” (

AIC

), “pegging” (

at bound or negative

). Detailed logs appear in

Appendix C.

Table 4.

Eleven non-convergent trace–observer pairs. Stress-flag codes: “Low

” (

), “AIC

” (

AIC

), “pegging” (

at bound or negative

). Detailed logs appear in

Appendix C.

| Sentence |

Observer |

Stress Flag(s) |

Root–cause commentary |

| gpath_1 |

O1 |

Low , AIC , pegging |

Non-monotonic spike defeats tanh shape; optimizer stalls. |

| gpath_1 |

O3 |

Low , AIC , pegging |

Same as above plus early-noise plateau. |

| gpath_2 |

O1 |

Fit fail, parameter pegging |

Extreme garden-path yields negative gradient. |

| gpath_2 |

O3 |

Fit fail, parameter pegging |

Identical to O1; inversion of expected . |

| ambig_1 |

O1 |

Low

|

Lexical ambiguity generates flat . |

| ambig_1 |

O3 |

Low

|

Same; retrieval never saturates. |

| aur_1 |

O3 |

Low

|

High WM load and short trace under-constrain fit. |

| aur_complex_1 |

O3 |

Low

|

Same pattern as aur_1. |

| aur_complex_2 |

O3 |

Fit fail, inversion |

Excessively long trace; optimizer exits at local minimum. |

| flat_1 |

O1 |

Low

|

Anomalous semantics keeps high; tanh under-fits tail. |

| flat_1 |

O3 |

Low

|

Same; observer divergence negligible. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).