Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Quantify group differences in body motion synchrony under unidirectional verbal communication;

- Characterize the variability and timing of listener synchrony in ASD;

- Assess the utility of phase-based synchrony features as potential behavioral markers for ASD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

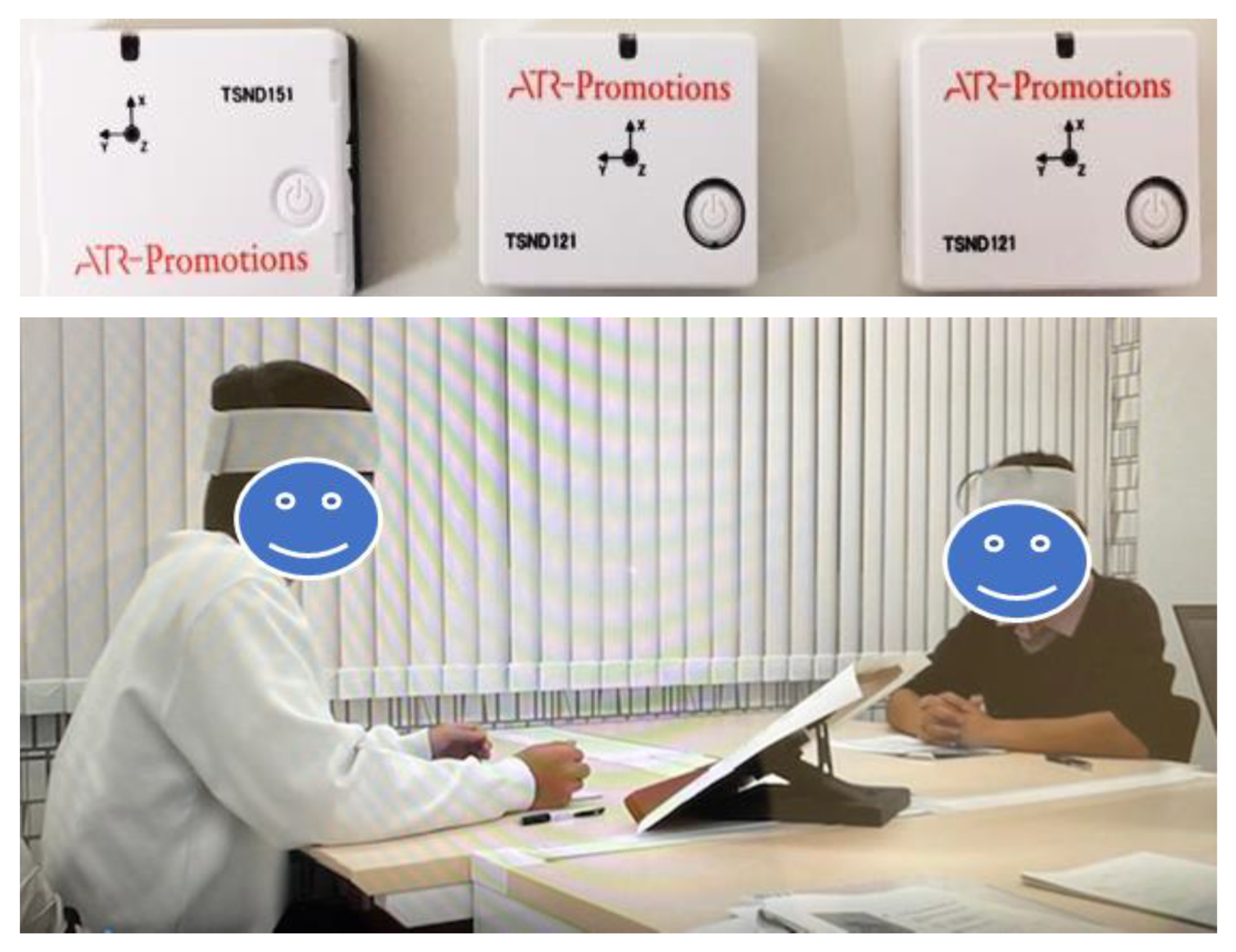

2.2. Experimental Environment and Apparatus

2.3. Experimental Procedures

3. Data Analysis

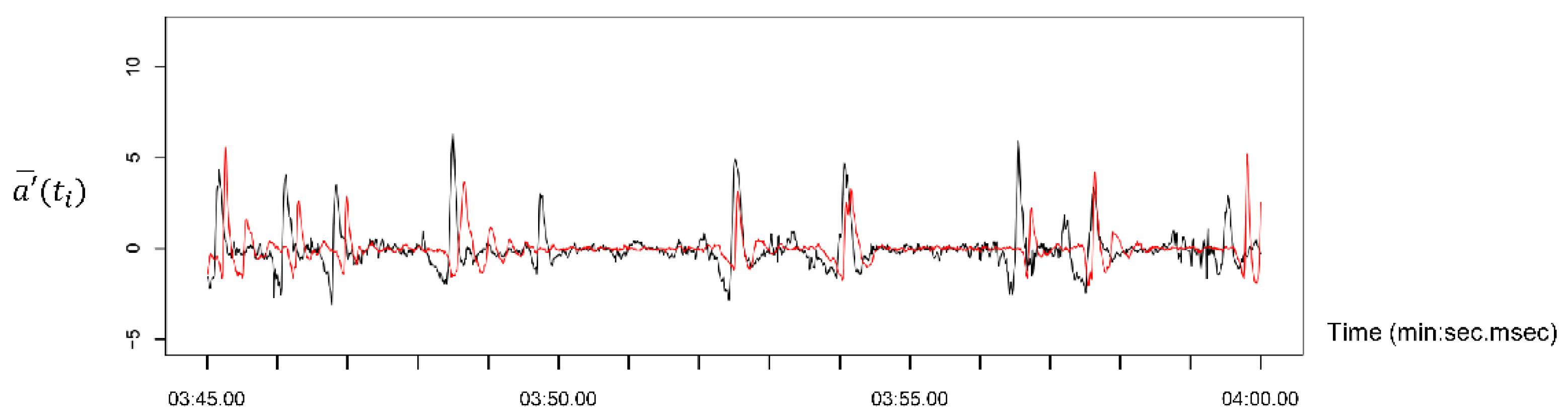

3.1. Phase Difference Detection Algorithm

3.2. Synchrony Feature Extraction

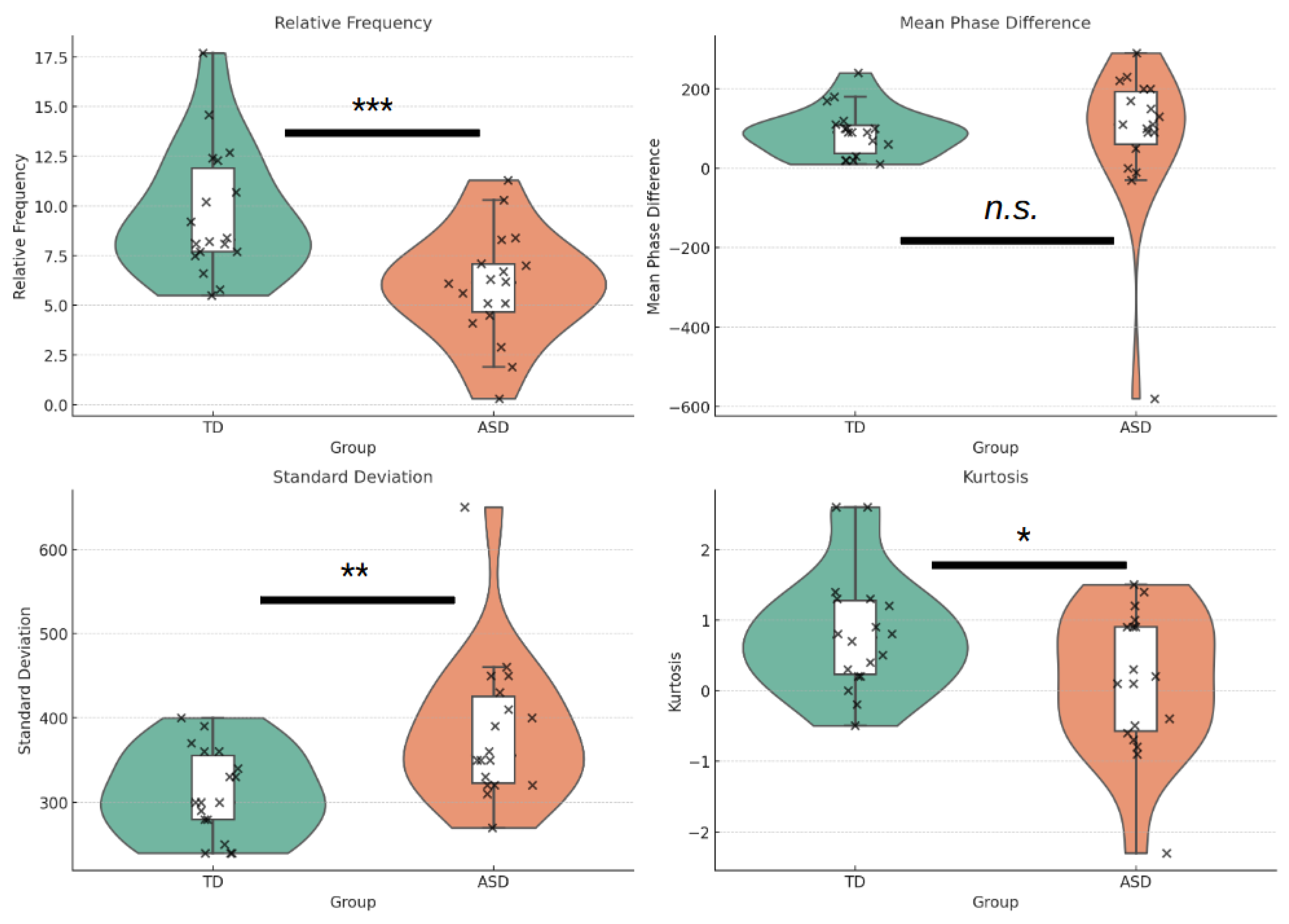

- Density (Synchrony Activity): The number of synchronized events per minute, reflecting the overall activity level of synchrony within a dyad.

- Mean Phase Difference (Synchrony Directionality): The average temporal lead or lag between paired movements. Positive values indicate that the speaker's movements consistently preceded those of the listener, while negative values indicate the opposite. This measure captures the directional dynamics of synchrony and reflects potential leader–follower roles within the interaction.

- Standard Deviation (Synchrony Variability): The dispersion of phase differences around the mean. Smaller values indicate more temporally precise alignment, whereas larger values reflect greater inconsistency in coordination.

- Kurtosis (Synchrony Coherence): A measure of the peakedness of the phase difference distribution. Higher kurtosis indicates stronger convergence of synchronized movements around the mean phase, implying greater coherence and temporal stability.

4. Results

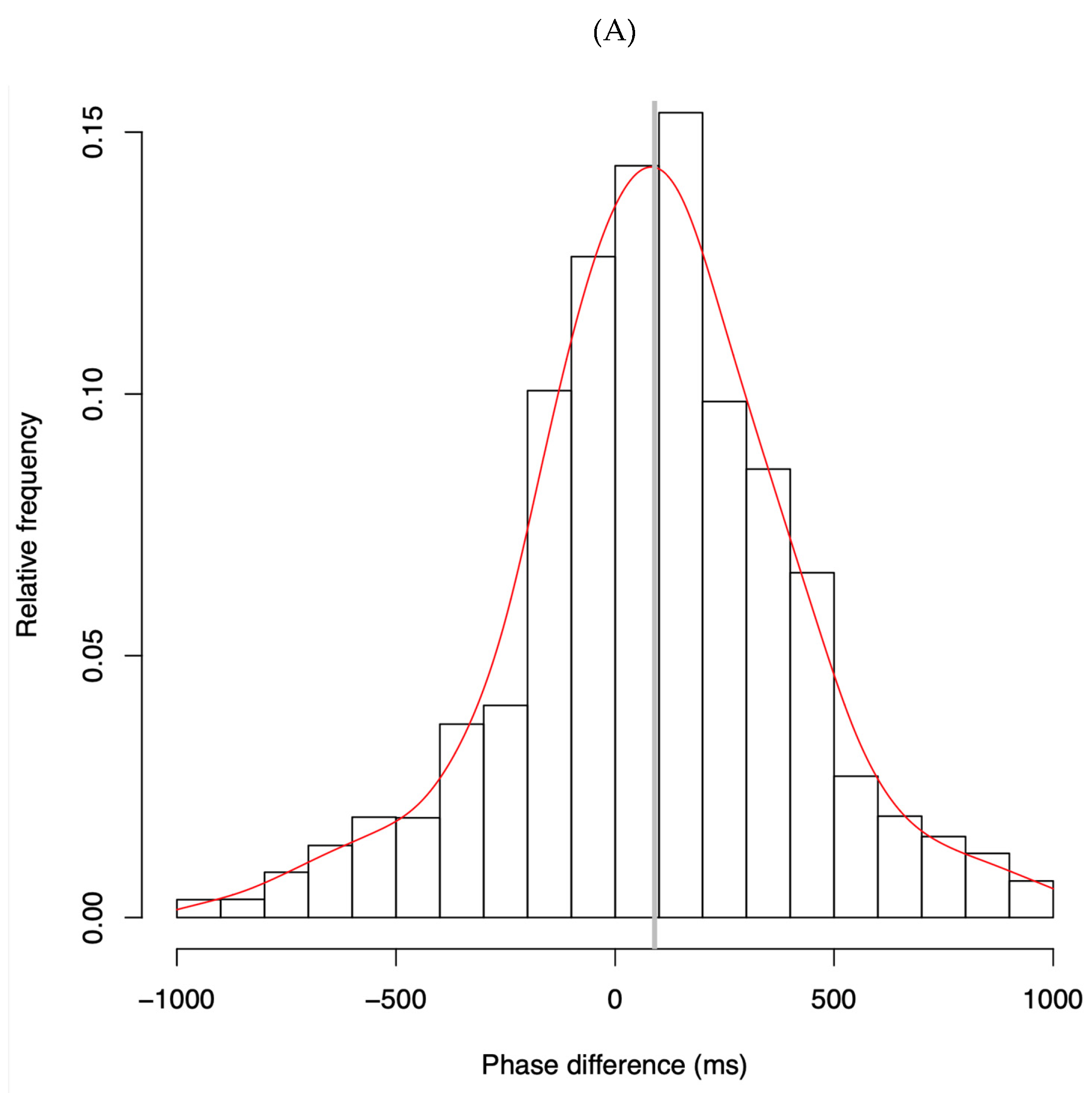

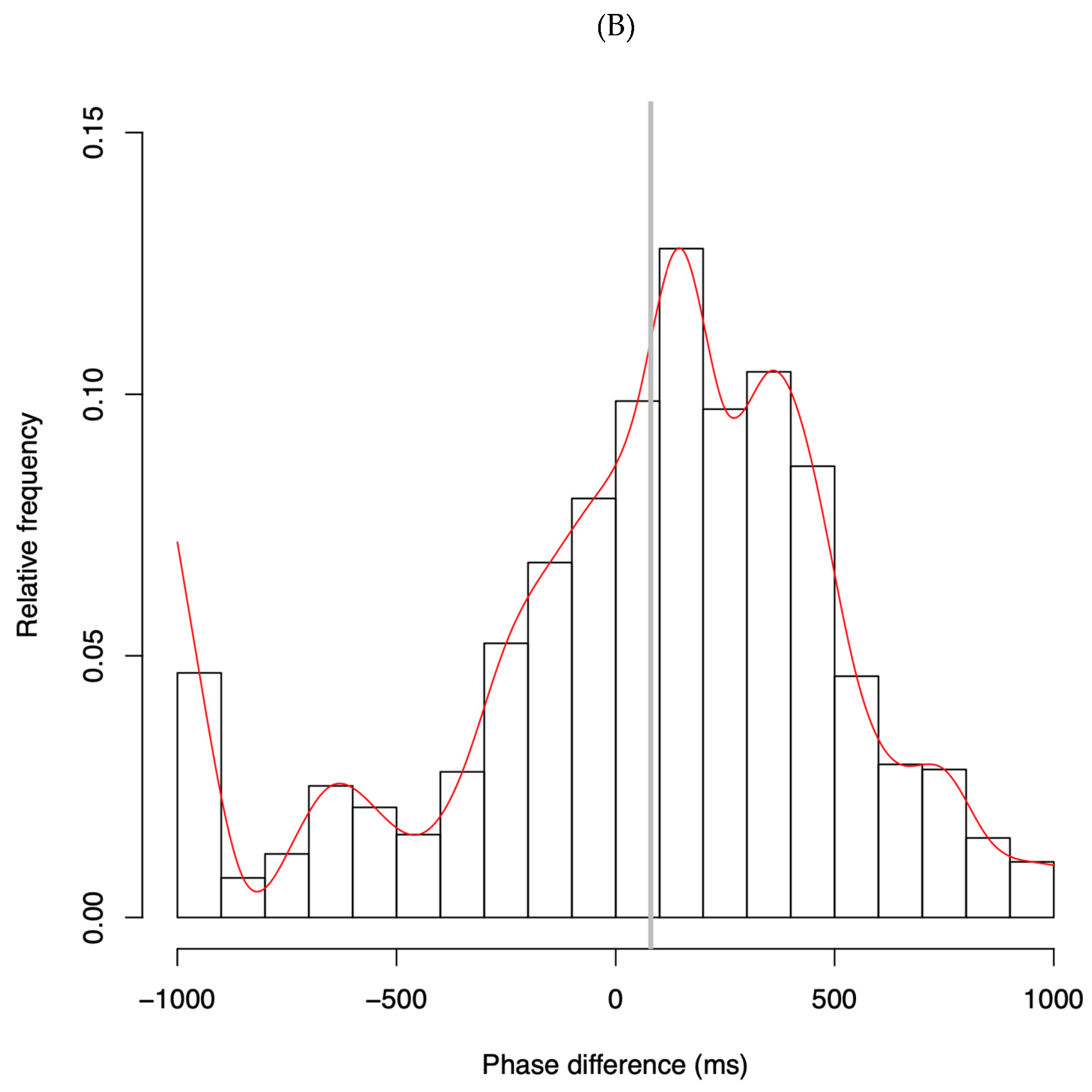

4.1. Phase Difference Distributions

4.2. Synchrony Metrics Across Groups

Synchrony Activity

Synchrony Directionality

Synchrony Variability

Synchrony Coherence

5. Discussion

- Methodological Advancements and Novel Contributions to Synchrony Research

- Synchrony Activity and Temporal Precision: Quantitative and Qualitative Divergences

- Phase Distributions and Entrainment Signatures

- Contextual and Individual Variability in ASD Synchrony Patterns

- Implications for ASD Assessment and Intervention

- Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, U. Autism: Explaining the Enigma; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Happé, F. Autism: Cognitive deficit or cognitive style? Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klin, A.; Jones, W.; Schultz, R.; Volkmar, F.; Cohen, D. Defining and quantifying the social phenotype in autism. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.C.; Morr, S.; Fitzpatrick, P.; Richardson, M.J. Measuring the dynamics of interactional synchrony. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2012, 36, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.C.; Richardson, M.J. Dynamics of interpersonal coordination. In Coordination: Neural, Behavioral and Social Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 281–308. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo, O.; Gordon, I. In and out of synchrony—Behavioral and physiological dynamics of dyadic interpersonal coordination. Psychophysiology 2020, 57, e13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaherche, E.; Chetouani, M.; Mahdhaoui, A.; Saint-Georges, C.; Viaux, S.; Cohen, D. Interpersonal synchrony: A survey of evaluation methods across disciplines. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseyer, F.; Tschacher, W. Nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: Coordinated body movement reflects relationship quality and outcome. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdesolo, P.; Ouyang, J.; DeSteno, D. The rhythm of joint action: Synchrony promotes cooperative ability. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 46, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Kato, M.; Saunders, J.A.; Tseng, C.H. Paired walkers with better first impression synchronize better. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hove, M.J.; Risen, J.L. It’s all in the timing: Interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Soc. Cogn. 2009, 27, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakin, J.L.; Chartrand, T.L. Using nonconscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 14, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Kimura, M.; Daibo, I. Rhythmic features of movement synchrony for bonding individuals in dyadic interaction. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2020, 44, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrends, A.; Müller, S.; Dziobek, I. Moving in and out of synchrony: A concept for a new intervention fostering empathy through interactional movement and dance. Arts Psychother. 2012, 39, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finset, A.; Ørnes, K. Empathy in the clinician–patient relationship: The role of reciprocal adjustments and processes of synchrony. J. Patient Exp. 2017, 4, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernieri, F.J.; Reznick, J.S.; Rosenthal, R. Synchrony, pseudosynchrony, and dissynchrony: Measuring the entrainment process in mother-infant interactions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschacher, W.; Rees, G.M.; Ramseyer, F. Nonverbal synchrony and affect in dyadic interactions. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogan, R.; Fischer, R.; Bulbulia, J.A. To be in synchrony or not? A meta-analysis of synchrony's effects on behavior, perception, cognition and affect. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 72, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseyer, F.; Tschacher, W. Synchrony in dyadic psychotherapy sessions. In Simultaneity: Temporal Structures and Observer Perspectives; World Scientific: Singapore, 2008; pp. 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, K.L.; Isenhower, R.W.; Richardson, M.J.; Helt, M.; Verbalis, A.D.; Schmidt, R.C.; Fein, D. Autism and social disconnection in interpersonal rocking. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, P.; Frazier, J.A.; Cochran, D.M.; Mitchell, T.; Coleman, C.; Schmidt, E.R. Impairments of social motor synchrony evident in autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehne, S.; Hatri, A.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Dziobek, I. Perceived interpersonal synchrony increases empathy: Insights from autism spectrum disorder. Cognition 2016, 146, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, S.; Salomäki, S.; Tuominen, J.; Arstila, V.; Falter-Wagner, C.M.; Noreika, V. Is there a generalized timing impairment in Autism Spectrum Disorders across time scales and paradigms? J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 99, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, A.L.; Koeroglu, S.; Hamilton, A.F.D.C.; Vogeley, K.; Falter-Wagner, C.M.; Tschacher, W. Reduced nonverbal interpersonal synchrony in autism spectrum disorder independent of partner diagnosis: A motion energy study. Mol. Autism 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, J.C.; Georgescu, A.L.; Weiske, J.; et al. Brief Report: Specificity of Interpersonal Synchrony Deficits to Autism Spectrum Disorder and Its Potential for Digitally Assisted Diagnostics. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 3718–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseyer, F.T. Motion energy analysis (MEA): A primer on the assessment of motion from video. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Yokomitsu, K. Video-based tracking approach for nonverbal synchrony: A comparison of Motion Energy Analysis and OpenPose. Behav. Res. 2021, 53, 2700–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornejo, C.; Cuadros, Z.; Morales, R.; Paredes, J. Interpersonal Coordination: Methods, Achievements, and Challenges. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Ogawa, K.I.; Ono, E.; Miyake, Y. Detection of nonverbal synchronization through phase difference in human communication. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Kotani, H. Head motion synchrony in unidirectional and bidirectional verbal communication. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavelas, J.B.; Gerwing, J. The listener as addressee in face-to-face dialogue. Int. J. Listen. 2011, 25, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stivers, T. Stance, alignment and affiliation during story telling: When nodding is a token of affiliation. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 2008, 41, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmann, A.T.; Llewellyn, L.G. Relationship between vocalizations and head nods as listener responses. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1968, 9, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, S.; Ide, S. Nodding, aizuchi, and final particles in Japanese conversation: How conversation reflects the ideology of communication and social relationships. J. Pragmat. 2007, 39, 1242–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S. Backchannels across cultures: A study of Americans and Japanese. Lang. Soc. 1989, 18, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angles, J.; Nagatomi, A.; Nakayama, M. Japanese responses hai, ee, and un: Yes, no, and beyond. Lang. Commun. 2000, 20, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Camacho, L.E.; Fishburn, F.A.; Belardi, K.; Williams, D.L.; Huppert, T.J.; Perlman, S.B. Dysfunction in interpersonal neural synchronization as a mechanism for social impairment in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampella, C.J.; Csumitta, K.D.; Simon, E.; Bennetto, L. Interactional synchrony and its association with social and communication ability in children with and without autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 3195–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chartrand, T.L.; Bargh, J.A. The chameleon effect: The perception–behavior link and social interaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakin, J.L.; Jefferis, V.E.; Cheng, C.M.; Chartrand, T.L. The chameleon effect as social glue: Evidence for the evolutionary significance of nonconscious mimicry. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2003, 27, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, L.K.; Nind, L.K.; Macrae, C.N. The rhythm of rapport: Interpersonal synchrony and social perception. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehl, S.; Fairhurst, M.; Schirmer, A. Interactional synchrony: Signals, mechanisms and benefits. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2021, 16, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, A.; Jin, C.; Lu, C. Putting our heads together: Interpersonal neural synchronization as a biological mechanism for shared intentionality. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 633–643. [Google Scholar]

- Oberman, L.M.; Winkielman, P.; Ramachandran, V.S. Slow echo: Facial EMG evidence for the delay of spontaneous, but not voluntary, emotional mimicry in children with autism spectrum disorders. Dev. Sci. 2009, 12, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Cruys, S.; Evers, K.; Van der Hallen, R.; Van Eylen, L.; Boets, B.; de-Wit, L.; Wagemans, J. Precise minds in uncertain worlds: Predictive coding in autism. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 121, 649–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.J.; Lawson, R.P.; Hohwy, J. Bayesian approaches to autism: Towards volatility, action, and behavior. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 521–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; Wilson, T.P. An oscillator model of the timing of turn-taking. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2005, 12, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, K.A.; Redcay, E. Interpersonal synchrony in autism. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lense, M.D.; Ladányi, E.; Rabinowitch, T.C.; Trainor, L.; Gordon, R. Rhythm and timing as vulnerabilities in neurodevelopmental disorders. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20200327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.M.; Wallace, M.T. Dysfunction of sensory oscillations in autism spectrum disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 848–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boets, B.; Verhoeven, J.; Wouters, J.; Steyaert, J. Fragile spectral and temporal auditory processing in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and early language delay. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 1845–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.; Koch, S.C. Embodied affectivity: On moving and being moved. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, D.; Lee, C.C.; Chaspari, T.; Black, M.P.; Williams, M.E.; Lee, S.; Narayanan, S.S. Acoustic-Prosodic, Turn-Taking, and Language Cues in Child-Psychologist Interactions for Varying Social Demand. In Proc. Interspeech 2013, 2400–2404. [Google Scholar]

- Corps, R.E.; Gambi, C.; Pickering, M.J. Coordinating utterances during turn-taking: The role of prediction, response preparation, and articulation. Discourse Process. 2018, 55, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, S.C.; Torreira, F. Timing in turn-taking and its implications for processing models of language. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riest, C.; Jorschick, A.B.; de Ruiter, J.P. Anticipation in turn-taking: Mechanisms and information sources. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skantze, G. Turn-taking in conversational systems and human-robot interaction: A review. Comput. Speech Lang. 2021, 67, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaghband-Rad, J.; Hajikarim-Hamedani, A.; Motamed, M. Camouflage and masking behavior in adult autism. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1108110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Hull, L.; Crane, L.; Mandy, W. Camouflaging in autism: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 89, 102080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, G.; Jayaramayya, K.; Balasubramanian, V.; Vellingiri, B. The potential role of rhythmic entrainment and music therapy intervention for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2019, 15, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.M.; Kaur, M.; Park, I.K.; Gifford, T.D.; Marsh, K.L.; Bhat, A.N. The effects of rhythm and robotic interventions on the imitation/praxis, interpersonal synchrony, and motor performance of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A pilot randomized controlled trial. Autism Res. Treat. 2015, 2015, 736516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, M.W.; LaGasse, A.B. Rhythm, movement, and autism: Using rhythmic rehabilitation research as a model for autism. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, G.E.; Kim, S.J. Dyadic drum playing and social skills: Implications for rhythm-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Music Ther. 2018, 55, 340–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Park, S.; Sakamoto, M.; Mito, K. The effects of vibratory frequency and temporal interval on tactile apparent motion. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2021, 14, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thepsoonthorn, C.; Yokozuka, T.; Kwon, J.; Yap, R.M.S.; Miura, S.; Ogawa, K.-I.; Miyake, Y. Look at you, look at me: Detection and analysis of mutual gaze convergence in face-to-face interaction. In Proc. IEEE/SICE Int. Symp. Syst. Integr. (SII) 2015, 581–586. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Miyake, Y. Motion-binding property contributes to accurate temporal-order perception in audiovisual synchrony. Multisens. Res. 2023, 36, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Q.; Ogata, T.; Ogawa, K.-I.; Kwon, J.; Miyake, Y. The simultaneous perception of auditory–tactile stimuli in voluntary movement. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Ogawa, K.-I.; Miyake, Y. The effect of visual apparent motion on audiovisual simultaneity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J. Synchrony Vision: Capturing Body Motion Synchrony Through Phase Difference Using the Kinect. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 41658–41669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ASD Participant No.(Gender) | Comorbidities & Medication (+/–) | IQ/DQ | AQ |

| A1(F) | ADHD (-) | 92 | 30 |

| A2(F) | — | Average Range | 28 |

| A3(F) | — | Average Rage | 30 |

| A4(F) | — | 97 | 21 |

| A5(M) | Epilepsy (+) | 87 | 38 |

| A6(M) | — | 121 | 33 |

| A7(M) | — | 102 | 35 |

| A8(M) | — | 75 | 34 |

| A9(F) | ADHD (+) | 87 | 38 |

| A10(M) | ADHD (-) | 115 | 36 |

| A11(M) | SLD | 86 | 35 |

| A12(F) | — | 139 | 30 |

| A13 (M) | — | 86 | 10 |

| A14 (M) | Color Vision Deficiency | 93 | 32 |

| A15 (M) | — | 93 | 22 |

| A16 (F) | SLD, ADHD (-) | 111 | 37 |

| A17 (F) | — | 97 | 38 |

| A18 (F) | — | 69 | 23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).