Submitted:

28 June 2024

Posted:

01 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Methodology

Section 3.1 Models

- 1.

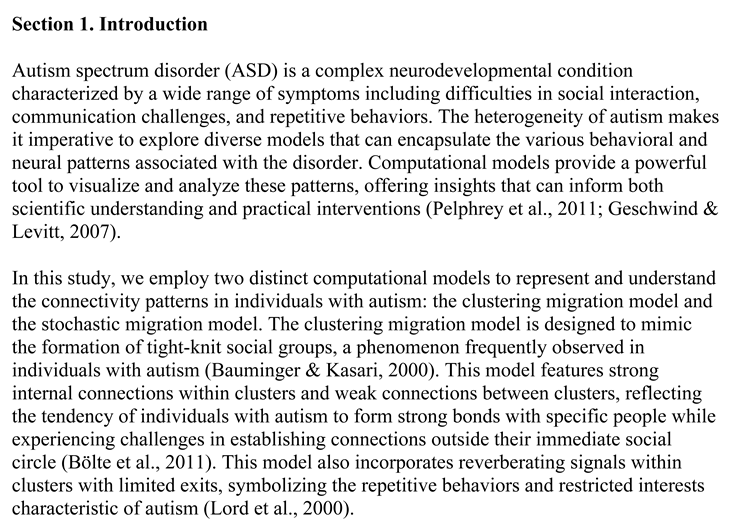

- Initial Positions: Cells are uniformly distributed along the x-axis:

- 1.

- 1. Initial Positions: Cells are uniformly distributed along x-axis:

- 2.

- Migration to Semicircle: Cells migrate to form a semicircle of radius 8, with clustering effects introduced by adding Gaussian noise:

- 3.

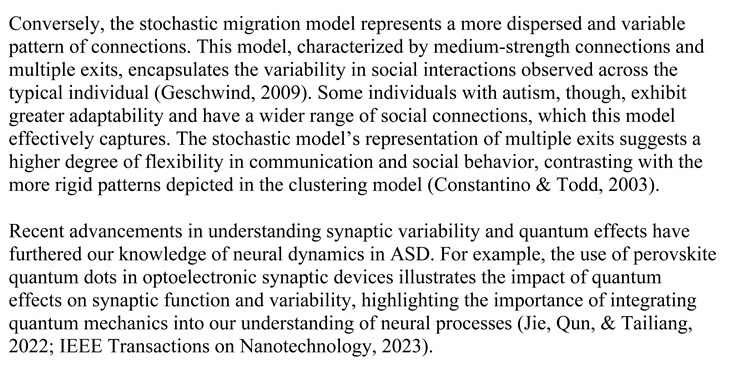

- Connectivity: Strong connections are established within clusters and weak connections between clusters:

- Initial Positions: Similar to Model 1, cells are uniformly distributed along the -axis.

- Stochastic Migration: Cells migrate to a semicircle of radius 8, with stochastic variations in their angles:

- 3.

- Connectivity Patterns: Various geometric patterns are defined (triangles, squares, hexagons, etc.), with connections established accordingly:

- 4.

- Medium Strength Random Connections: Additional connections are added with medium strength:

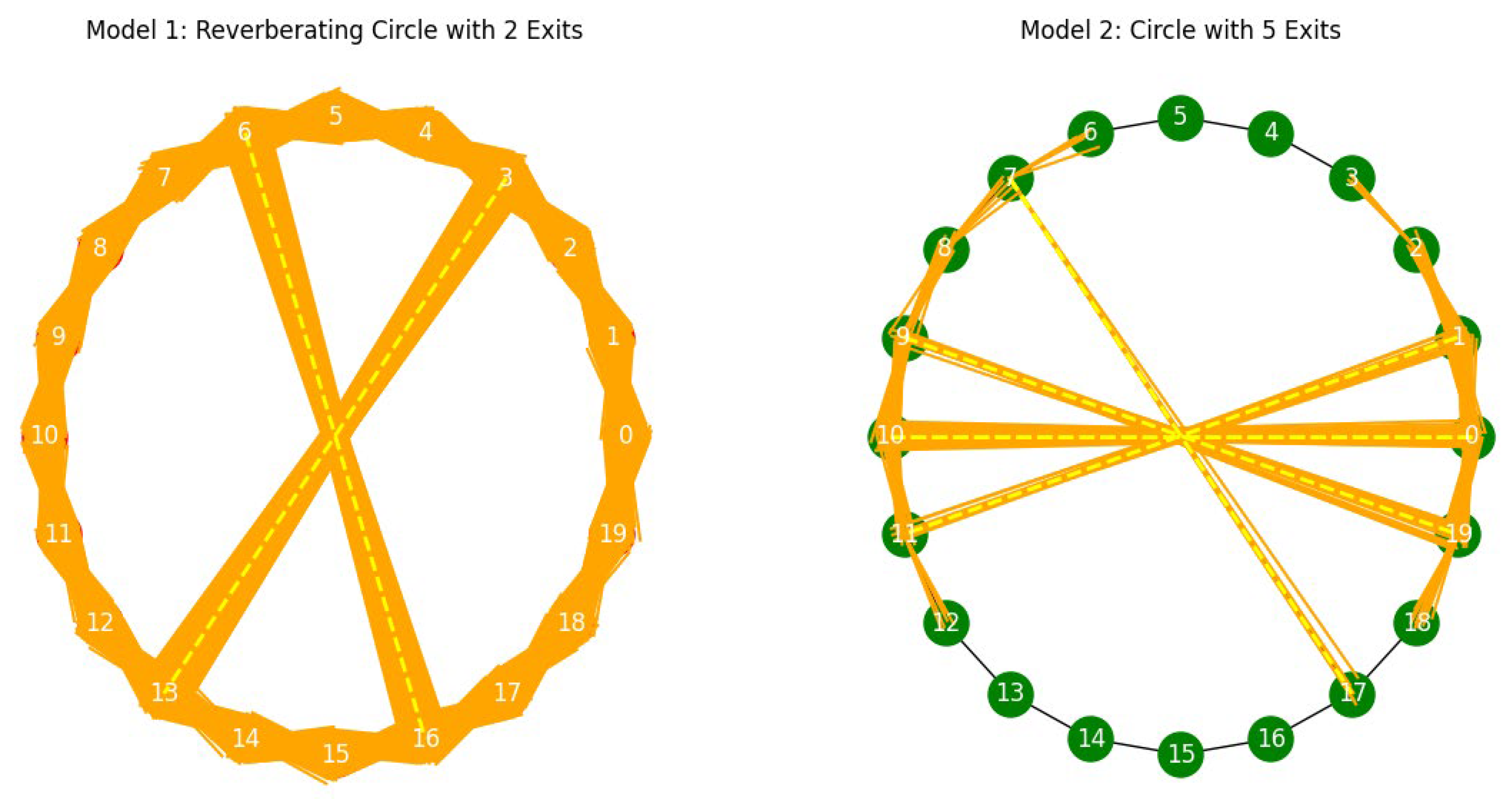

- Circle Graph with Exits: A circle graph with 20 nodes is created, with nodes connected in a circular manner and specific exit nodes:

- Circle Graph with Exits: A circle graph with 20 nodes is created, with nodes connected in a circular manner and specific exit nodes:

- 2.

- Reverberating Signals: Signals propagate with added noise, representing the dynamic nature of neural communication:

- 3.

- Escape Probability: The escape probability at exits is defined by a Bernoulli trial:

- 4.

- Number of Reverberations: The number of reverberations is controlled by the number of iterations:

Section 3.2 Visualization

Section 4. Results

- Cells form distinct clusters with strong internal connections.

- Weak connections are observed between clusters, representing limited interaction outside immediate social groups.

- The clustering effect introduces slight positional perturbations, emphasizing the tendency of individuals with autism to form tight-knit social groups and experience challenges in connecting outside these groups.

- Cells are more evenly dispersed along the semicircle, reflecting greater variability in social interactions.

- The presence of medium-strength random connections between nodes suggests flexibility and adaptability in communication.

- Scenario 1: Circle graph with 20 nodes and 2 exits.

- Signals reverberate 20 times within the circle before exiting, representing difficulty in breaking out of behavior loops.

- Limited exits symbolize challenges in transitioning between tasks or environments, akin to the repetitive behaviors seen in autism.

- 2.

- Scenario 2: Circle graph with 20 nodes and 5 exits.

- Signals reverberate 5 times within the circle before exiting, indicating greater ease in transitioning between states.

- Multiple exits represent higher flexibility and adaptability in neural communication, akin to individuals with more fluid social interactions.

Section 5. Discussion

Section 5.1 Clustering Migration Model

Section 5.2 Stochastic Migration Model

Section 5.3 Neural Connectivity and Behavioral Correlates

Section 5.4 Implications for Intervention

Conclusion

Section 6. Attachments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, L. F. , & Regehr, W. G. (2004). Synaptic computation. Nature, 431(7010), 796-803.

- Baron-Cohen, S. (2008). Autism and Asperger syndrome. Oxford University Press.

- Bauminger, N.; Kasari, C. Loneliness and Friendship in High-Functioning Children with Autism. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliss, T.V.P.; Collingridge, G.L. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 1993, 361, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölte, S.; Westerwald, E.; Holtmann, M.; Freitag, C.; Poustka, F. Autistic Traits and Autism Spectrum Disorders: The Clinical Validity of Two Measures Presuming a Continuum of Social Communication Skills. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 41, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, L. Memristor-The missing circuit element. IEEE Trans. Circuit Theory 1971, 18, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, J. N. , & Todd, R. D. (2003). Autistic traits in the general population: A twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(5), 524-530.

- Courchesne, E.; Pierce, K.; Schumann, C.M.; Redcay, E.; Buckwalter, J.A.; Kennedy, D.P.; Morgan, J. Mapping Early Brain Development in Autism. Neuron 2007, 56, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Campo, M.; Mollenhauer, B.; Bertolotto, A.; Engelborghs, S.; Hampel, H.; Simonsen, A.H.; Kapaki, E.; Kruse, N.; Le Bastard, N.; Lehmann, S.; et al. Recommendations to Standardize Preanalytical Confounding Factors in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers: An Update. Biomarkers Med. 2012, 6, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, B. , Hampel, H., & Feldman, H.H., et al. (2016). Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimer’s Dementia, 12, 292-323.

- Fisher, M.P. Quantum cognition: The possibility of processing with nuclear spins in the brain. Ann. Phys. 2015, 362, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschwind, D. H. (2009). Advances in autism. Annual Review of Medicine, 60, 367-380.

- Geschwind, D.H.; Levitt, P. Autism spectrum disorders: developmental disconnection syndromes. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007, 17, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-Y.; Dan, Q.-Q.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.-K.; Fu, S.-J.; Zhao, N.; Wang, T.-H. Protein Network Analysis of the Serum and Their Functional Implication in Patients Subjected to Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henstridge, C.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Spires-Jones, T.L. Beyond the neuron–cellular interactions early in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huebschman, N. A. , Prakapenka, L., & Fishman, P. S., et al. (2021). FMRP regulates synaptic development and plasticity in the striatum. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 14, 629849.

- Jie, S. , Qun, Y., & Tailiang, G. (2022). Perovskite Quantum Dots for Emerging Displays: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Nanomaterials, 12(13), 2243.

- Kanner, L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv. Child 1943, 2, 217–250. [Google Scholar]

- Landa, R. Early communication development and intervention for children with autism. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Risi, S.; Lambrecht, L.; Cook, J.E.H.; Leventhal, B.L.; DiLavore, P.C.; Pickles, A.; Rutter, M. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: A Standard Measure of Social and Communication Deficits Associated with the Spectrum of Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2000, 30, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Wagner, A.; Rogers, S.; Szatmari, P.; Aman, M.; Charman, T.; Dawson, G.; Durand, V.M.; Grossman, L.; Guthrie, D.; et al. Challenges in Evaluating Psychosocial Interventions for Autistic Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2005, 35, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malpetti, M. , Jones, P. S., & Thomas, D. L., et al. (2021). Synaptic loss in the frontal cortex is associated with cognitive deficits in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain, 144(11), 3369-3382.

- Montgomery, R. M. (2023). Visualizing Social and Neural Connectivity in Autism: Insights from Clustering and Stochastic Models. Universidade de Aveiro.

- Nanomaterials (2022). Perovskite Quantum Dots for Emerging Displays: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Nanomaterials, 12(13), 2243.

- Pakkenberg, B.; Pelvig, D.; Marner, L.; Bundgaard, M.J.; Gundersen, H.J.G.; Nyengaard, J.R.; Regeur, L. Aging and the human neocortex. Exp. Gerontol. 2003, 38, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelphrey, K.A.; Shultz, S.; Hudac, C.M.; Wyk, B.C.V. Research Review: Constraining heterogeneity: the social brain and its development in autism spectrum disorder. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PLOS Computational Biology (2020). Axonal Noise as a Source of Synaptic Variability. PLOS Computational Biology.

- Proteomic insights into synaptic signaling in the brain: the past, present and future (2021). Molecular Brain, 14, 113.

- Purves, D. , Augustine, G. J., Fitzpatrick, D., Katz, L. C., LaMantia, A. S., McNamara, J. O., & Williams, S. M. (2001). Neuroscience. Sinauer Associates.

- Quantum Dot Optoelectronic Synaptic Devices (2023). IEEE Transactions on Nanotechnology.

- Suzuki, K. , Tsunekawa, Y., & Inoue, K., et al. (2020). Synthetic organizer proteins that restore synaptic function. Nature Neuroscience, 23(3), 294-303.

- Tegmark, M. Importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 61, 4194–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Quantum Biology of Consciousness and Visual Perception (2021). Frontiers in Neuroscience.

- Uddin, L.Q.; Supekar, K.; Menon, V. Reconceptualizing functional brain connectivity in autism from a developmental perspective. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 53721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).