Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ №1

- Can sentence transformers’ embeddings and graph-based solutions correctly capture the notion of sentence entailment? Theoretical results (Section 4.1) indicate that similarity metrics that mainly consider the symmetric properties of the data are unsuitable for capturing the notion of logical entailment, for which we at least need quasi-metric spaces or divergence measures. This paper offers the well-known metric of confidence [17] for this purpose and contextualises it within logic-based semantics for full texts.

- RQ №2

-

Can pre-trained language models correctly capture the notion of sentence similarity? The previous result should imply the impossibility of accurately deriving the notion of equivalence, as entailment implies equivalence through if-and-only-if relationships but not vice versa. Meanwhile, the notion of sentence indifference should be kept distinct from the notion of conflict. We designed empirical experiments with certain datasets to address the following sub-questions:

- (a)

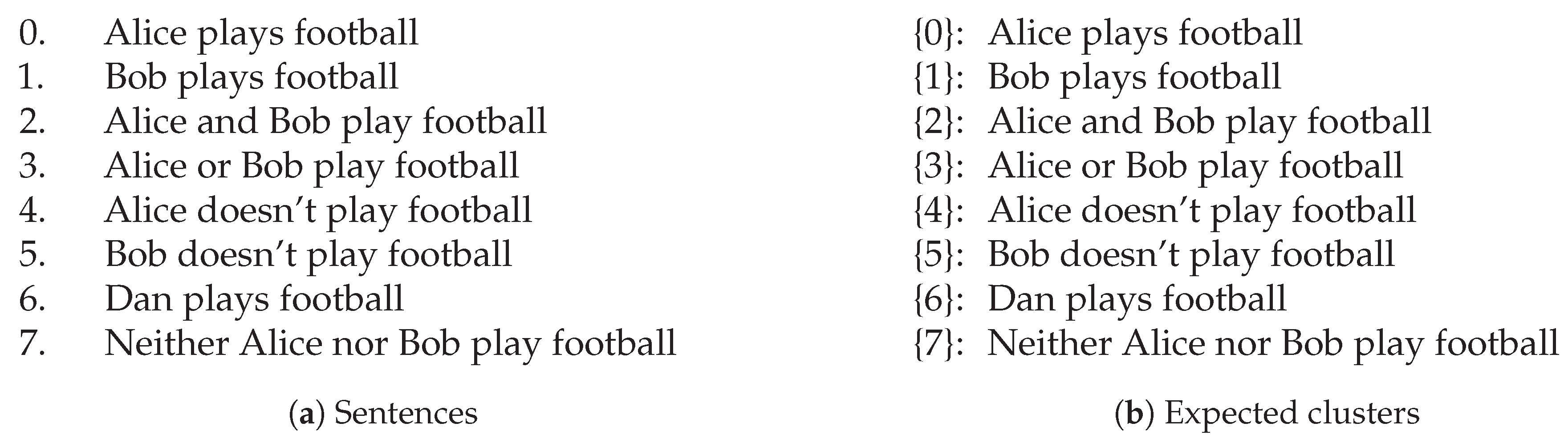

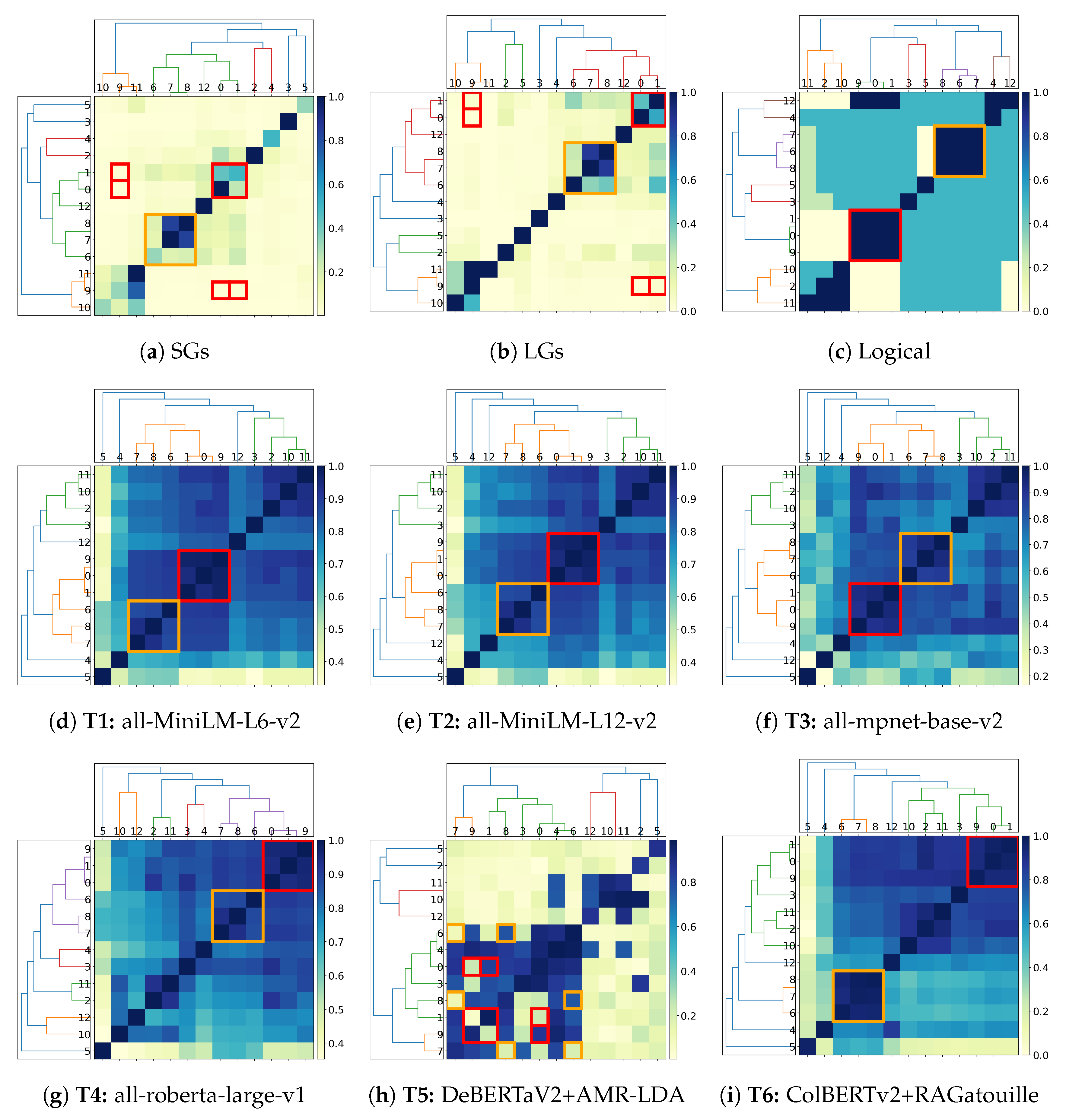

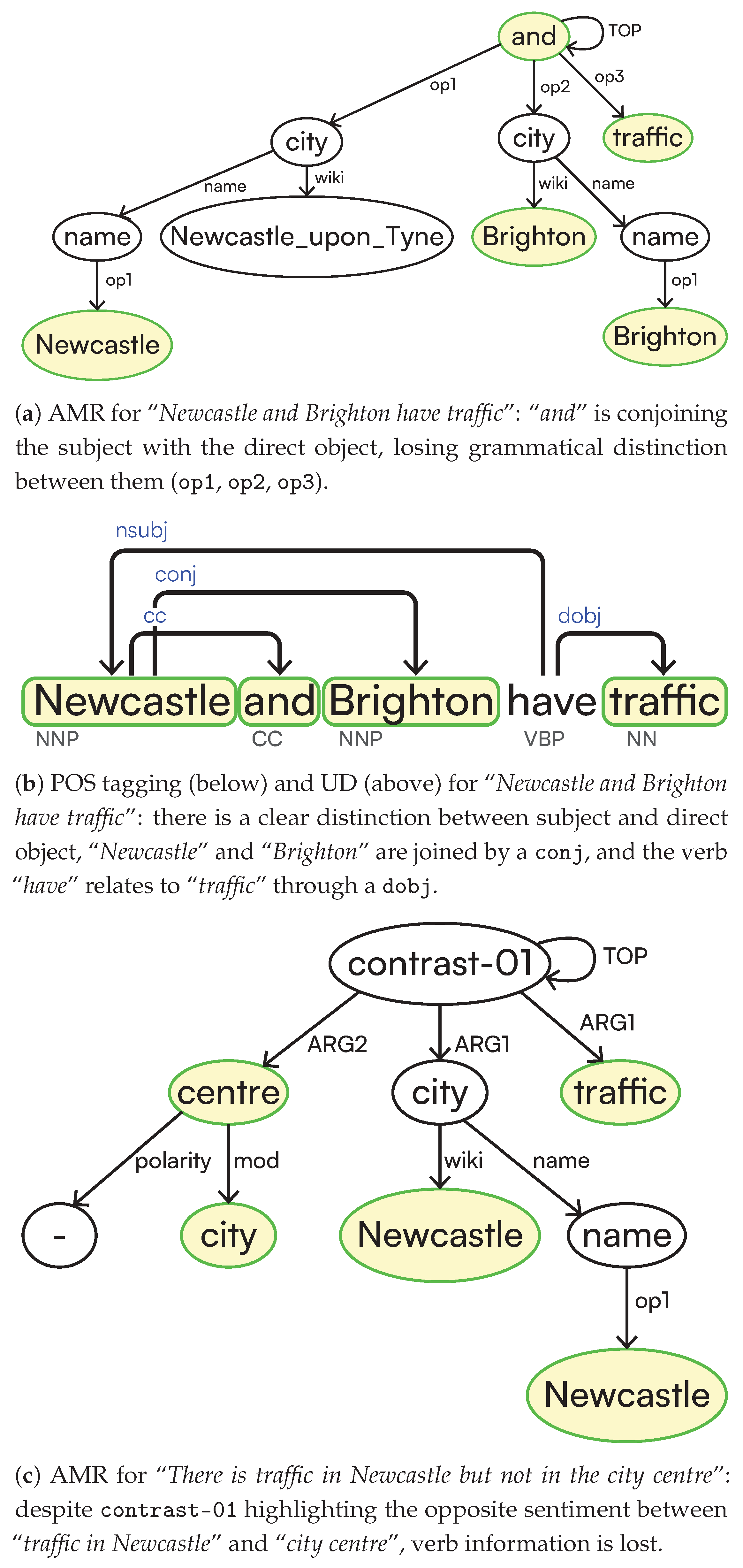

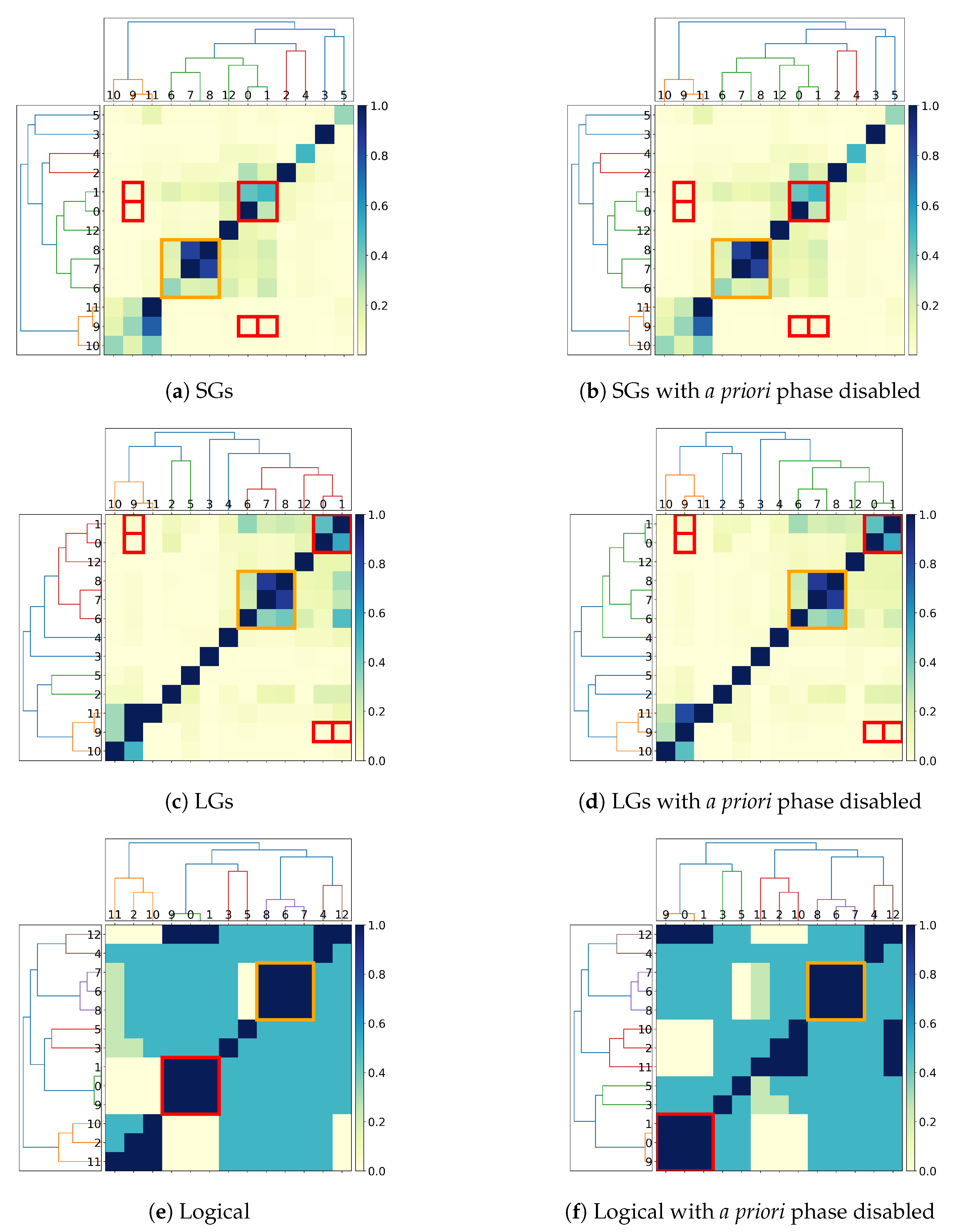

- Can pre-trained language models capture logical connectives? Current experiments (Section 4.2.1) show that pre-trained language models cannot adequately capture the information contained in logical connectives. The results can be improved after elevating such connectives as first-class citizens (Simple Graphs (SGs) vs. Logical Graphs (LGs)). Furthermore, given the experiments’ outcomes, vector embedding likely favours entities’ positions in the text and discards logical connectives within the text as stop words.

- (b)

- Can pre-trained language models distinguish between active and passive sentences? Preliminary experiments (Section 4.2.2) show that structure alone is insufficient for implicitly deriving semantic information. Additional disambiguation processing is required to derive the correct representation desiderata (SGs and LGs vs. logical). Furthermore, pre-trained language models that either mask and tokenise the sentence or exploit Abstract Meaning Representation (AMR) representation fail to faithfully represent simple sentence structures, even without calling on logical inference or negation detection.

- (c)

- Can pre-trained language models correctly capture the notion of logical implication, e.g., in spatiotemporal reasoning? Spatiotemporal reasoning requires specific part-of and is-a reasoning. This, to the best of our knowledge and at the time of this paper’s writing, is unprecedented in the existing literature on logic-based text interpretation. Consequently, we argue that these notions cannot be captured with embeddings alone or with graph-based representations using merely structural information, as this requires categorising the logical function of each entity within the text as well as correctly addressing the interpretation of the logical connectives occurring (Section 4.2.3).

- RQ №3

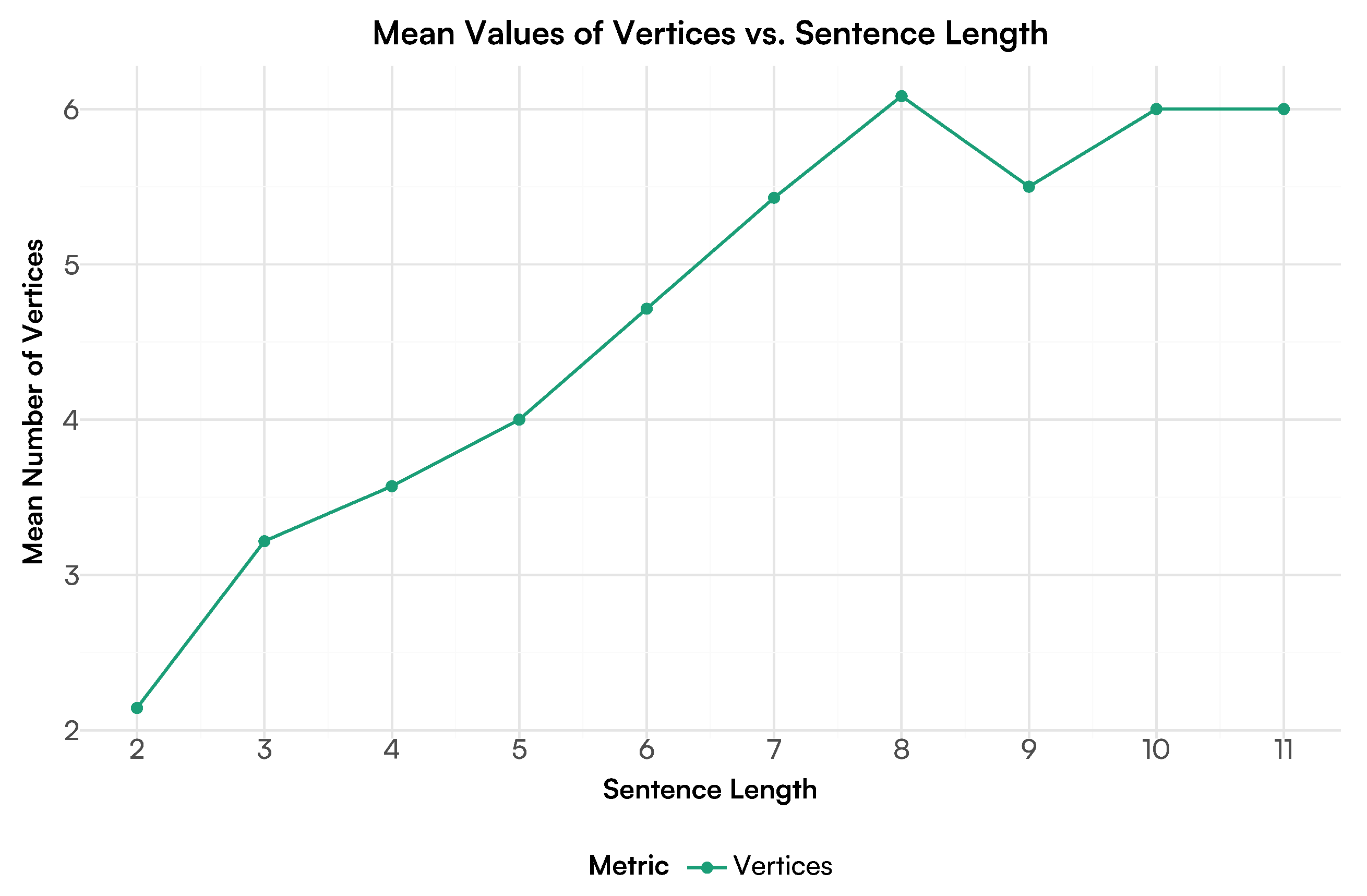

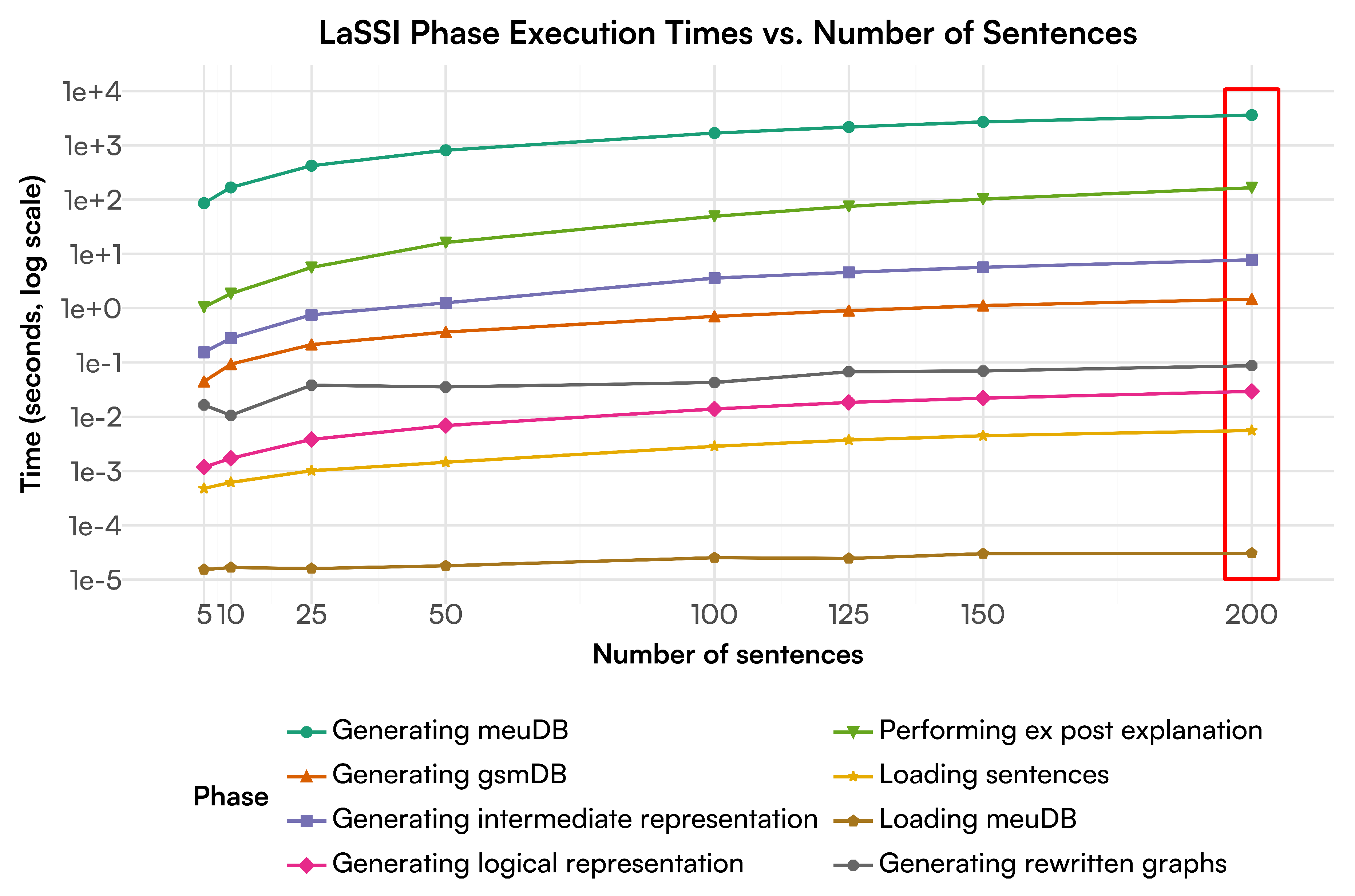

- Is our proposed technique scalable? Benchmarks over a set of 200 sentences retrieved from sentences within ConceptNet [2] (Section 4.3) indicate that our pipeline runs in at most linear time over the number of sentences, thus indicating the optimality of the envisioned approach.

- RQ №4

- Can a single rewriting grammar and algorithm capture most factoid sentences? Our Discussion (Section 5) remarks that this preliminary work improves over the sentence representation from our previous solution, but there are still ways to improve the current pipeline. We also argue the following: given that training-based systems also use annotated data to correctly identify patterns and return correct results (Section 2.2), the output provided by training-based algorithms, without abductive reasoning [18,19] or relational learning support [20], can only be as correct as a human’s ability to consider all possible cases for validation. Furthermore, to better ensure the correctness of the inference process, the inverse approach should be investigated, which is commonly used in Upper Ontologies [21] through machine teaching [22,23,24].

- We extend our logical representation of sentences to also consider existential quantifiers (subject ellipsis): this is paired with an algorithmic extension of our pipeline (Appendix B.3.1).

- We capture richer sentence semantics by acknowledging the logical functions of adverbial phrases rather than just recognising the type associated with this (Section 3.2.3) and, for the first time, provide a pipeline enabling logical sentence analysis of the sentence per Italian Linguistics (Section 2.3.1).

- We capture the notion of semantic entailment across atoms through the Parmenides KB (Appendix D.2.1).

- The ad hoc phase (Section 3.2) now addresses some of the errors generated through automated Universal Dependency (UDs) extraction by leveraging limited syntactical context and annotated dictionaries from the a priori phase (Supplement III and Supplement IV).

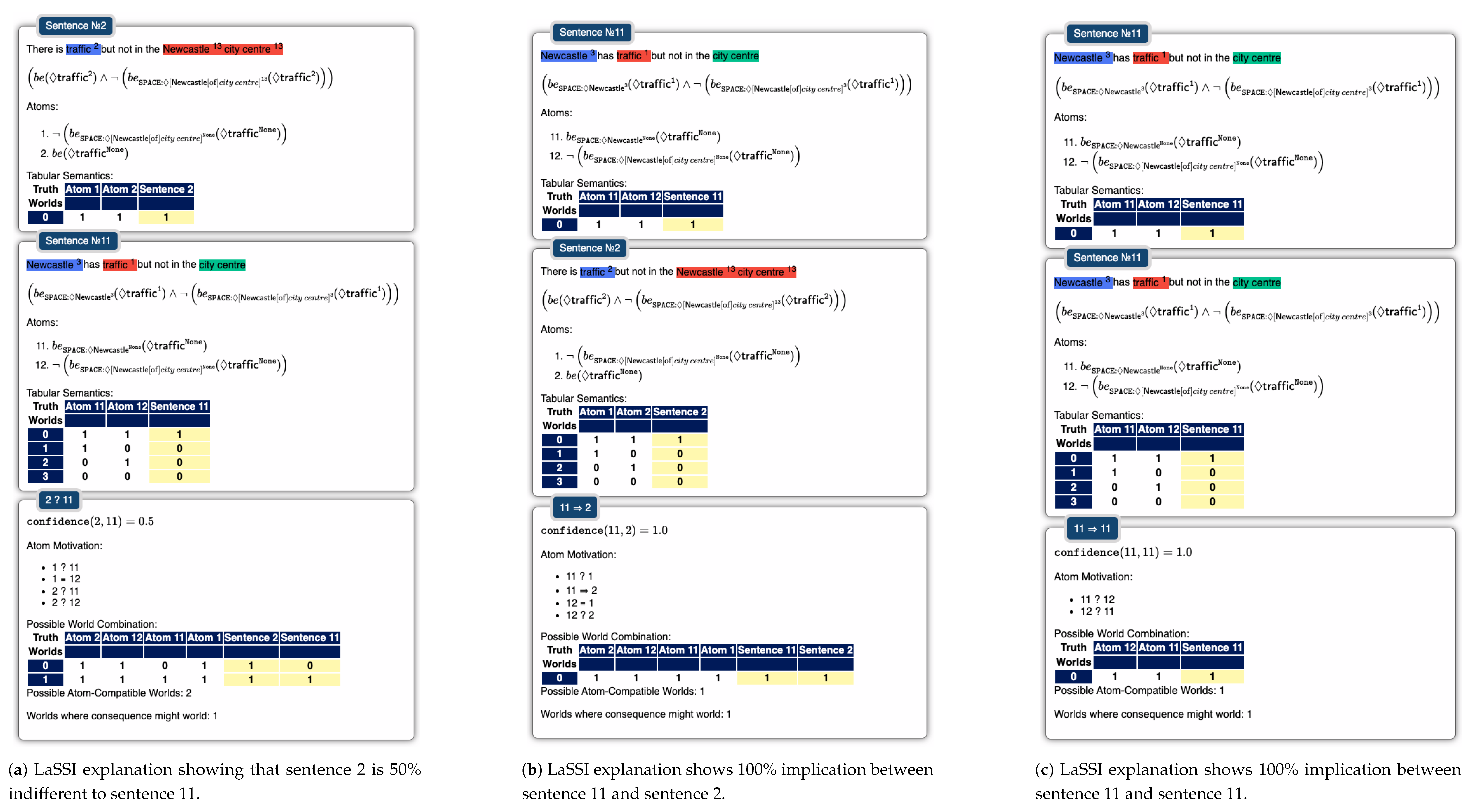

- We extend our pipeline to plot an explanation for the implication, inconsistency, or indifference for each pair of sentences (Section 5.3).

2. Related Works

2.1. General Explainable and Verified Artificial Intelligence (GEVAI)

2.2. Natural Language Processing (NLP)

2.3. Linguistics and Grammatical Structure

2.3.1. Italian Linguistics

2.4. Pre-Trained Language Models

2.4.1. Sentence Transformers

2.4.2. Neural IR

2.4.3. Generative Large Language Models (LLMs)

3. Materials and Methods

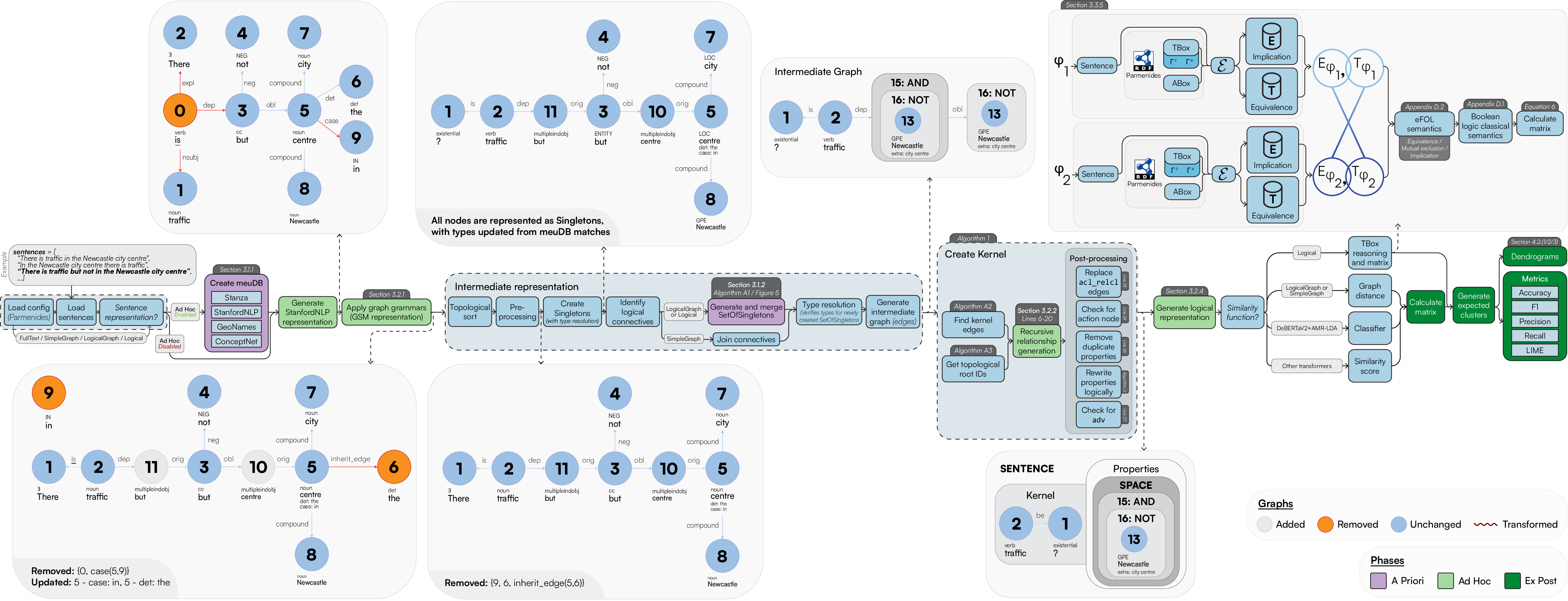

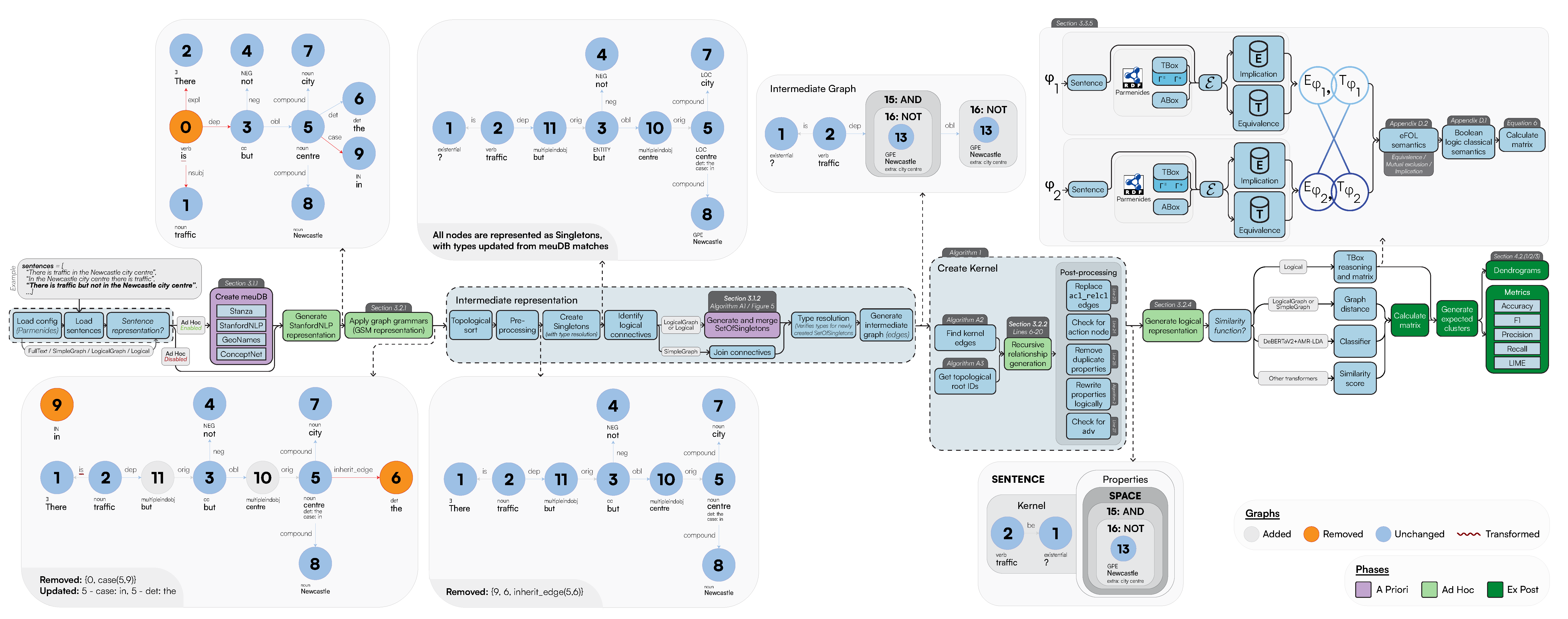

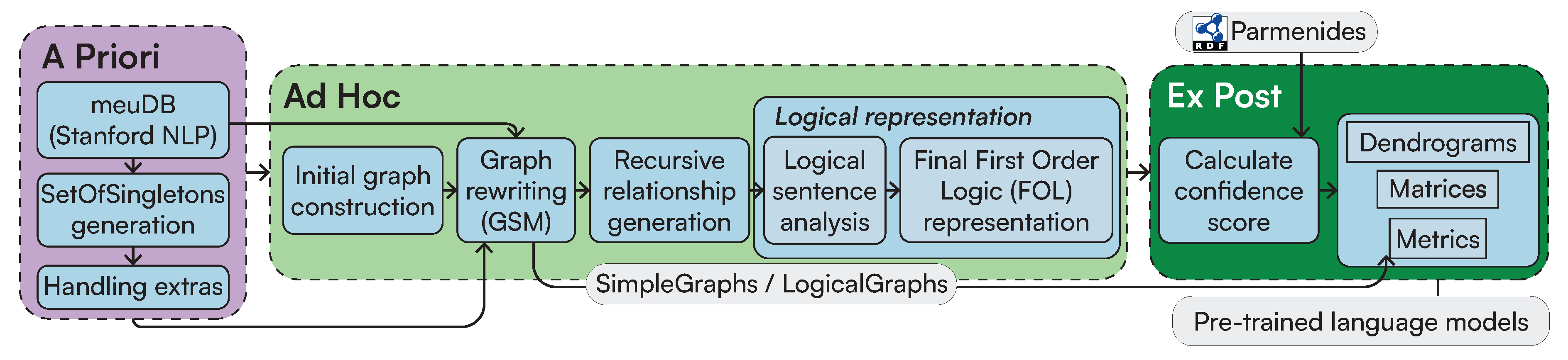

3.1. A Priori

3.1.1. Syntactic Analysis using Stanford CoreNLP

- start and end characters respective to their character position within the sentence: these constitute provenance information that is also pertained in the ad hoc explanation phase (Section 3.2), thus allowing the enrichment of purely syntactic sentence information with a more semantic one.

- text value referring to the original matched text.

-

monad for the possible replacement value:

- -

- Supplement III.3 details that this might eventually replace words in the logical rewriting stage.

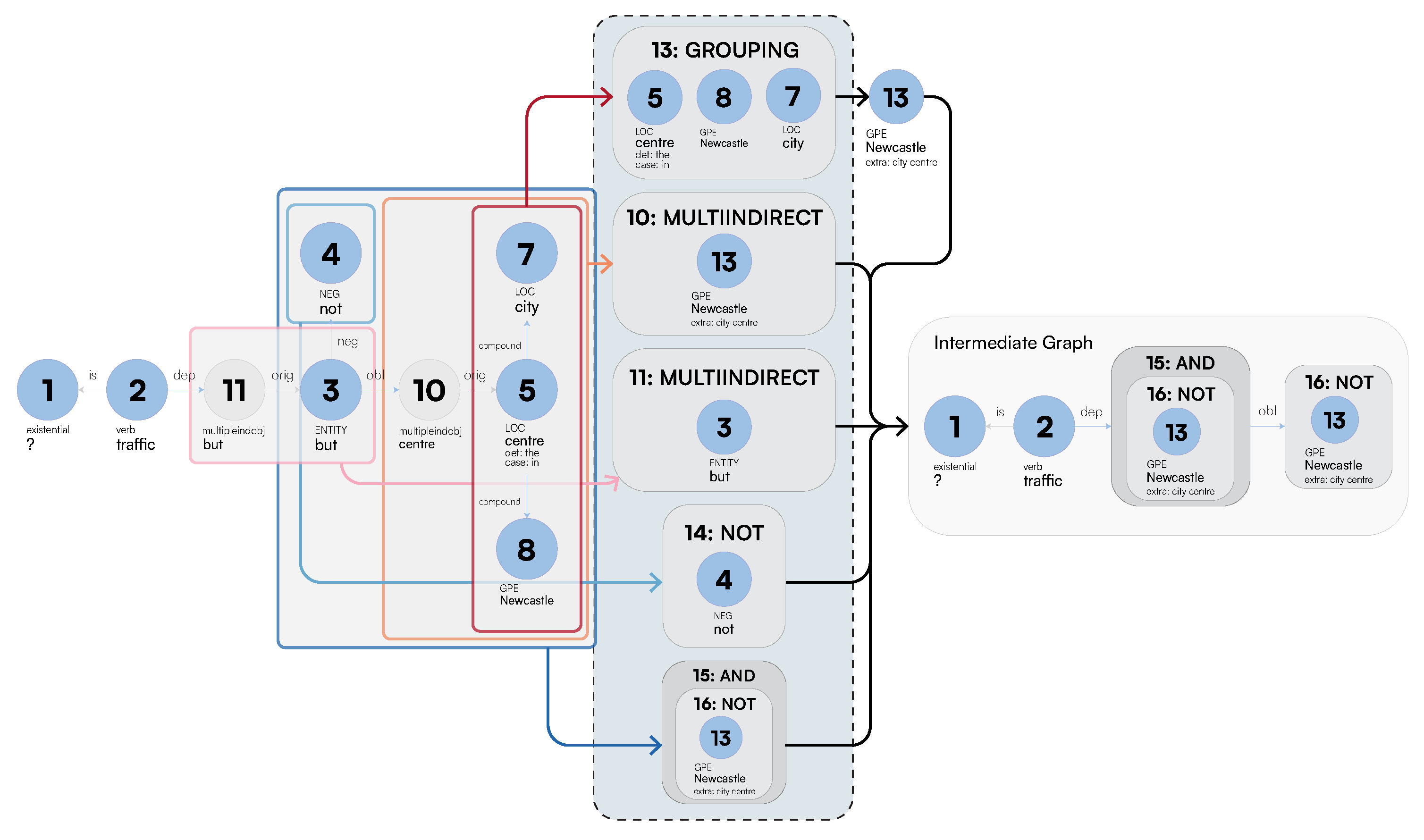

3.1.2. Generation of SetOfSingletons

-

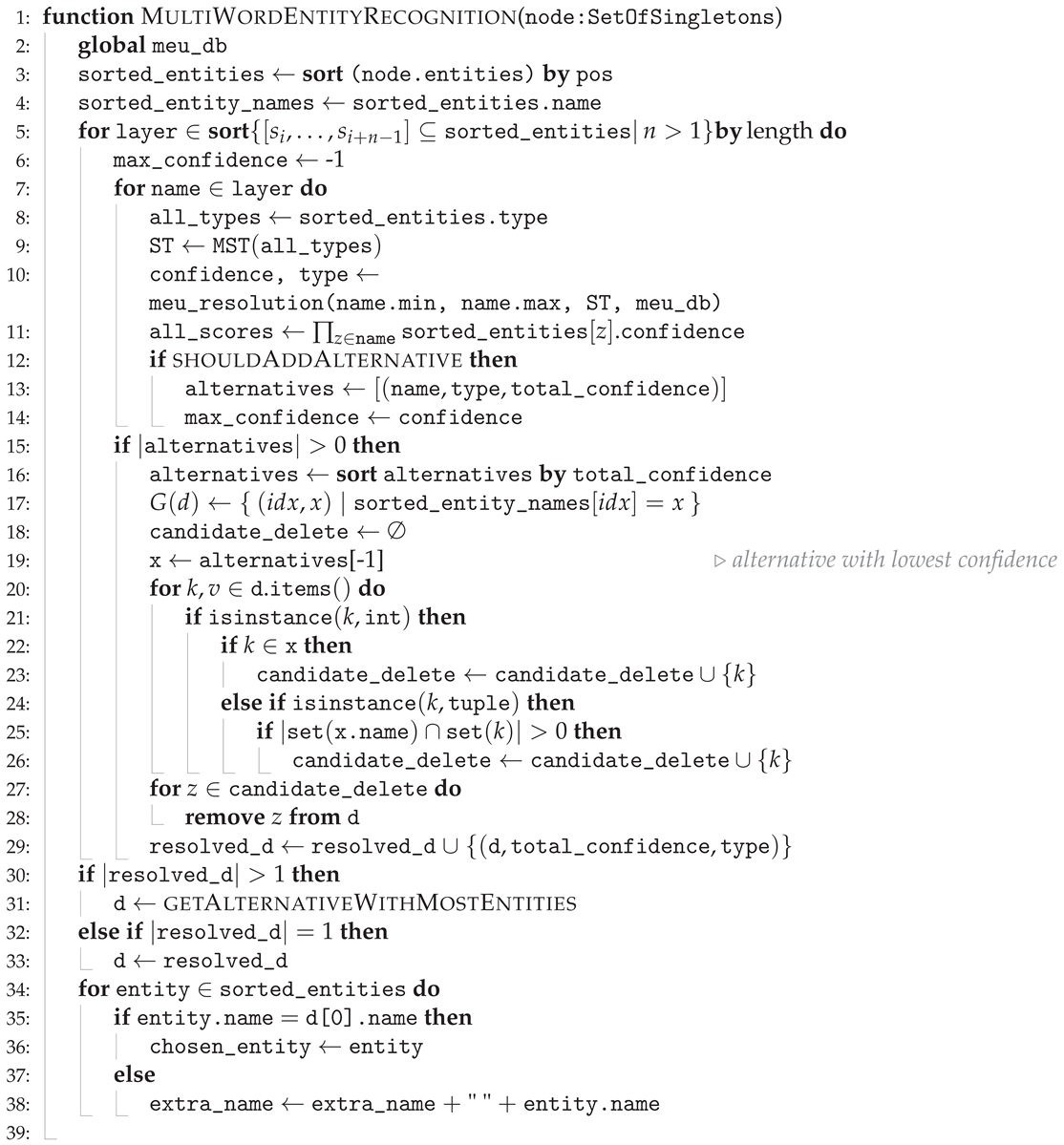

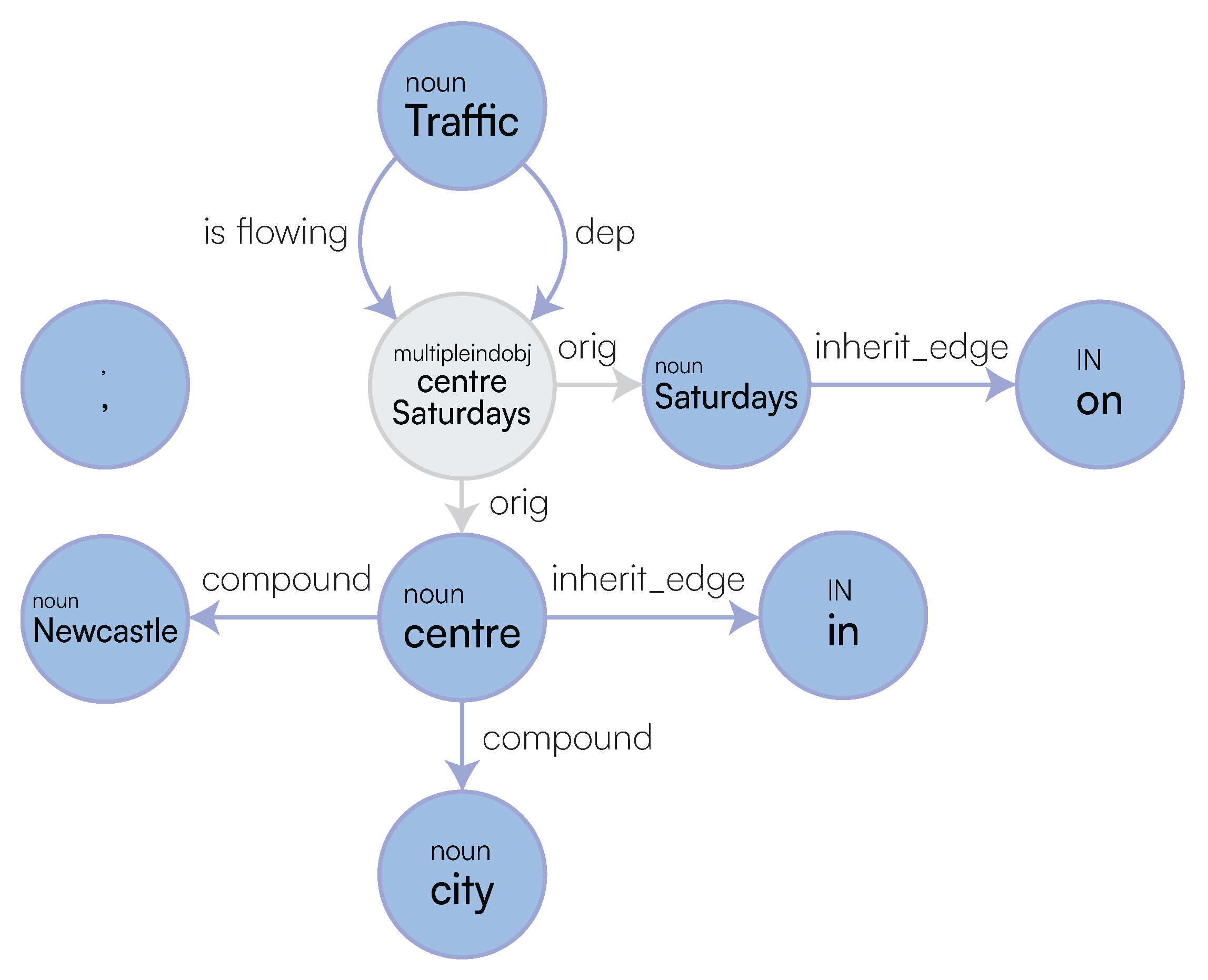

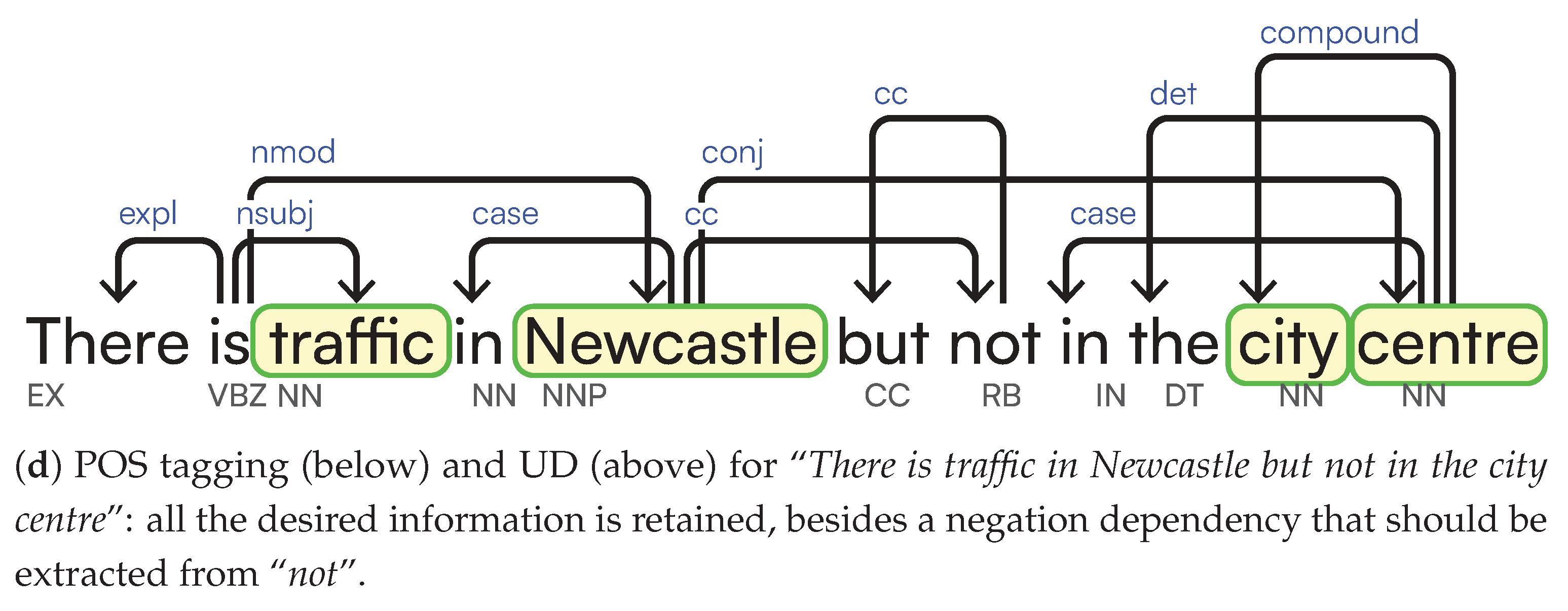

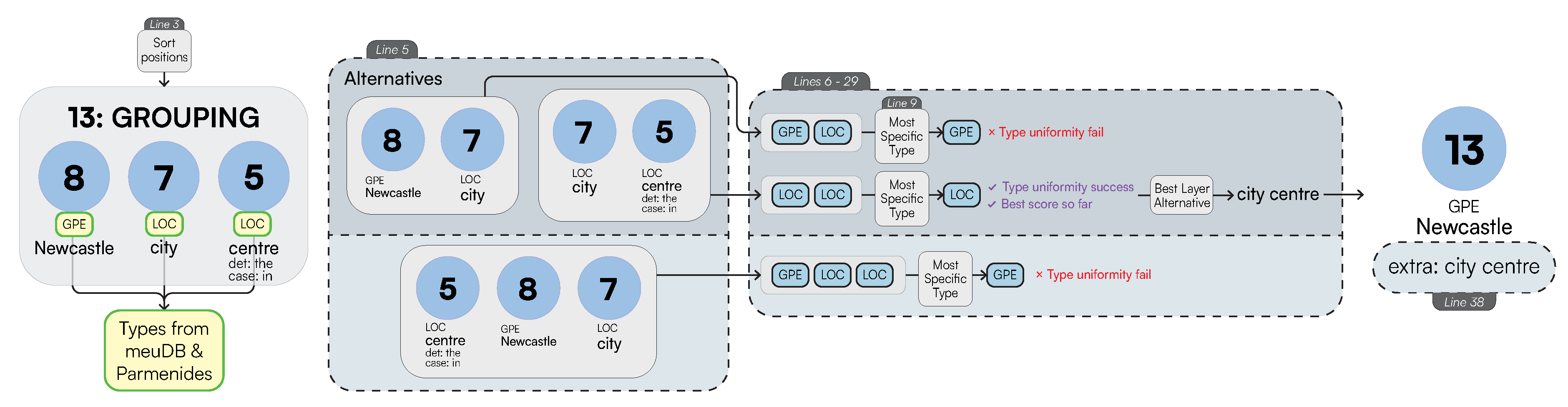

Multi-Word Entities: Algorithm 1 performs node grouping [66] over the the nodes connected by compound edge labels while efficiently visiting the graph using a Depth-First Search (DFS) search. After this, we identify whether a subset of these nodes acts as a specification (extra) to the primary entity of interest or whether it should be treated as a single entity. This is computed as follows: after generating all the possible ordered grouping of words, we associate each group to a type as derived by their corresponding meuDB match. Through the typing information, we then decide to keep the most specific type as the main entity, while leaving the most general one as a specification (extra). While doing so, we also consider the confidence of the fuzzy string matching through the meuDB. Appendix A.1 provides further algorithmic details on how LaSSI performs this computation.Example 1.After coalescing thecompoundrelationships from Figure 5, we would like to represent the grouping “Newcastle city centre” as a Singleton with a core entity “Newcastle” and anextra“city centre”. Figure 6 sketches the main phases of Algorithm 1 leading to this expected result. For our example, the possible ordered permutations of the entities withinGROUPINGare: “Newcastle city”, “city centre”, and “Newcastle city centre”. Given these alternatives, “Newcastle city centre” returns a confidence of 0.8 and “city centre” returns the greatest confidence of1.0, so our chosen alternative is [city,centre]. As “Newcastle” is the entity having the most specific type, this is selected as ourchosen_entity, and subsequently, “city centre” becomes theextraproperty to be added to “Newcastle”, resulting in our finalSingleton: Newcastle[extra:city centre].For Simplistic Graphs, “Newcastle upon Tyne” would be represented as oneSingletonwith noextraproperty.

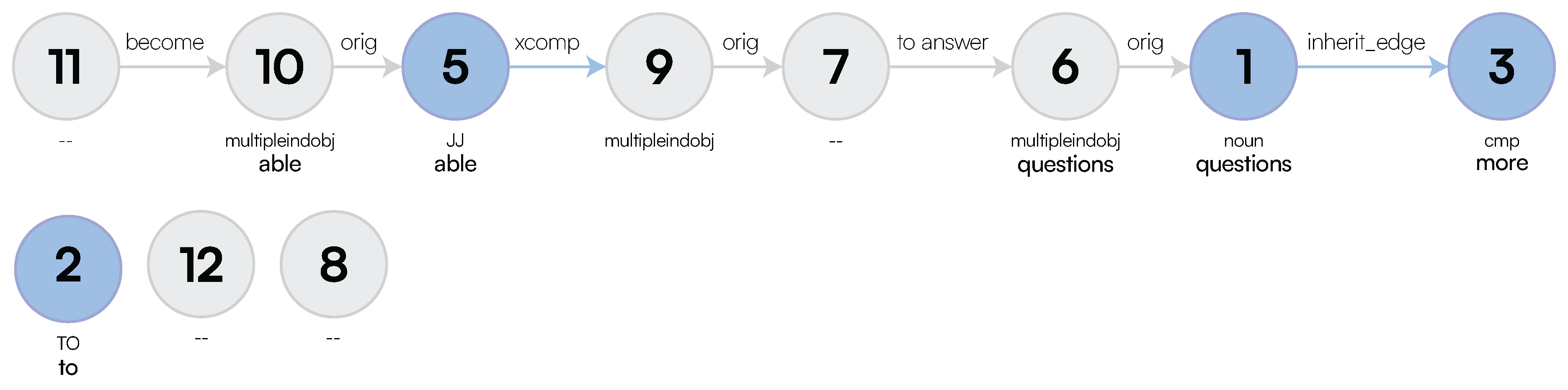

- Multiple Logical Functions: Due to the impossibility of graphs to represent n-ary relationships, we group multiple adverbial phrases into one SetOfSingleton. These will be then semantically disambiguated by their function during the Logical Sentence Analysis (Section 3.2.3). Figure 5 provides a simple example, where each MULTIINDIRECT contains either one adverbial phrase or a conjunction. Appendix A.2 provides a more compelling example, where such SetOfSingleton actually contains more Singletons.

-

Coordination: For coordination induced by conj relationships, we can derive a coordination type to be AND, NEITHER, or OR. This is derived through an additional cc relationship on any given node through a Breadth-First Search (BFS) that will determine the type.Last, LaSSI also handles compound_prt relationships; unlike the above, these are coalesced into one Singleton as they represent a compound word: becomes , and are not therefore represented as a SetOfSingleton.

| Algorithm 1 Given a SetOfSingletons node, this pseudocode shows how it is merged, while also determining whether an `extra’ should be added to the resulting merged Singleton node. |

|

3.2. Ad Hoc

3.2.1. Graph Rewriting with the Generalised Semistructured Model (GSM)

3.2.2. Recursive Relationship Generation

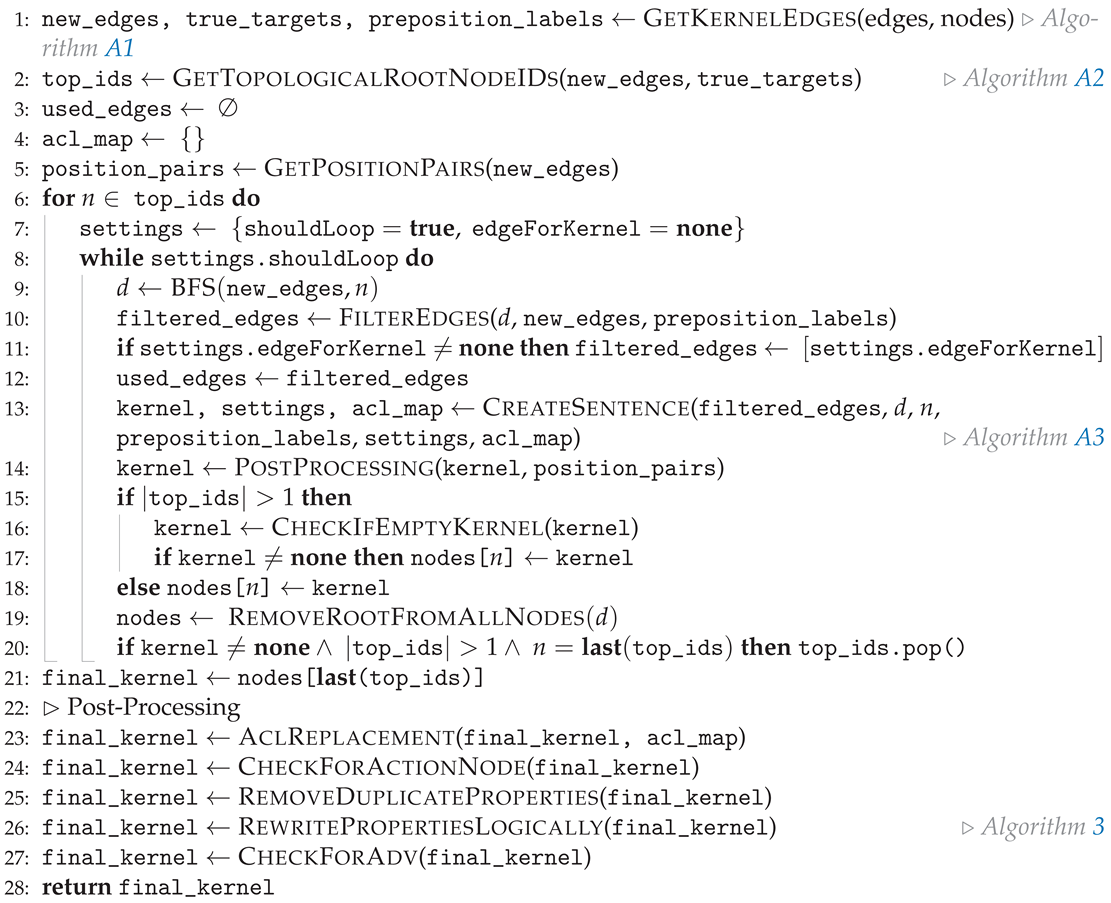

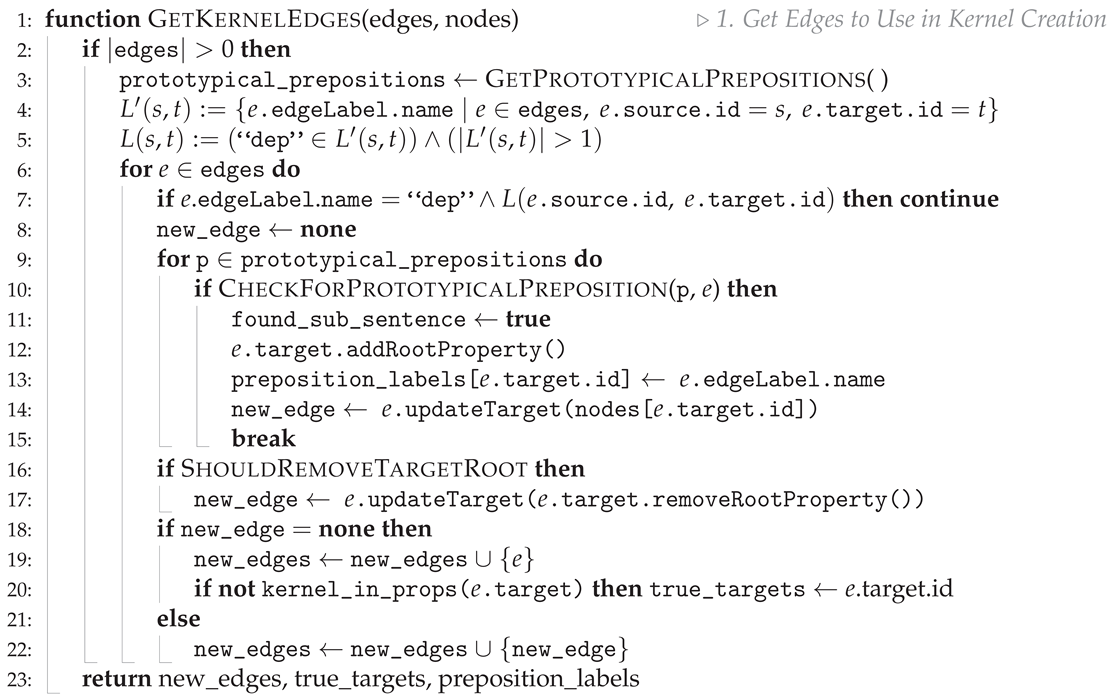

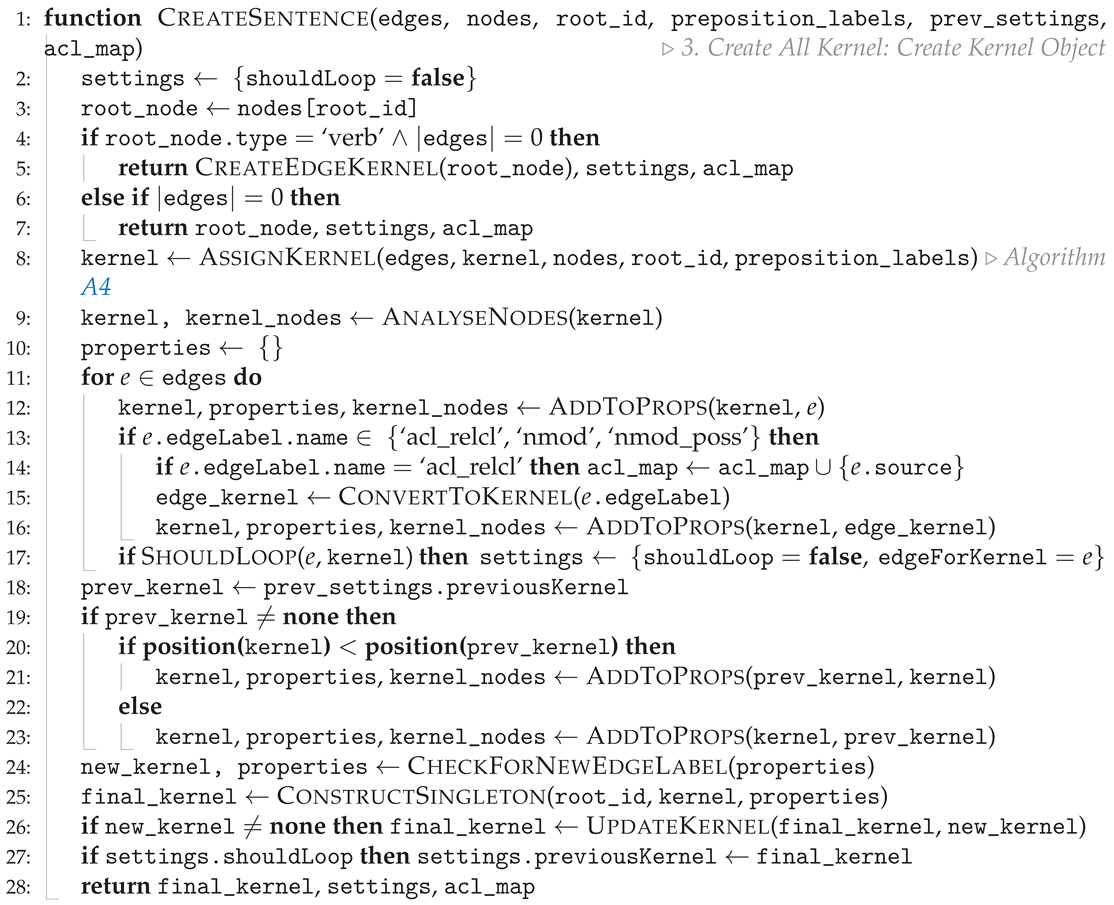

| Algorithm 2 After our a priori phase, we move to creating our final kernel. This is how our sentence is represented before transforming into our final logical representation. |

|

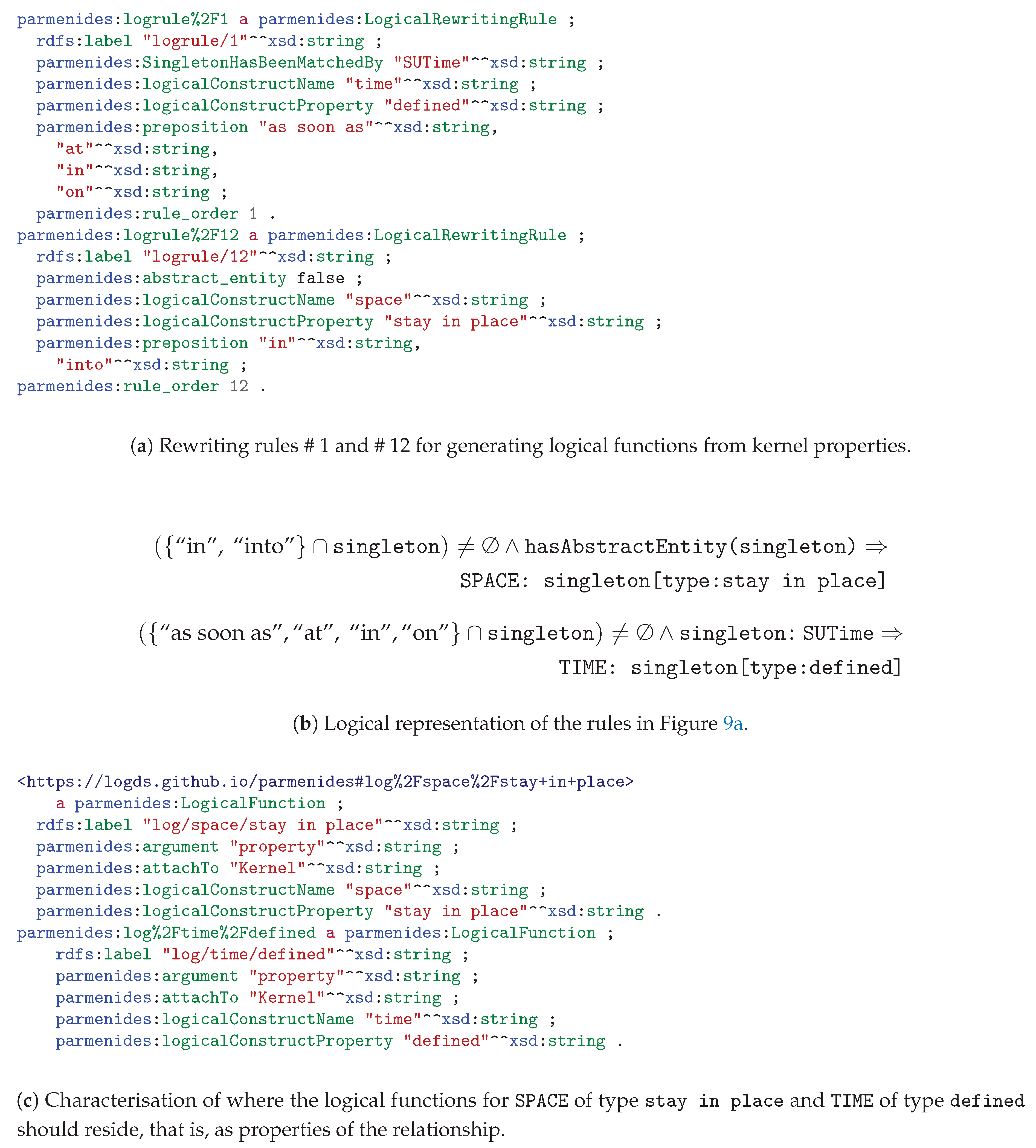

3.2.3. Logical Sentence Analysis

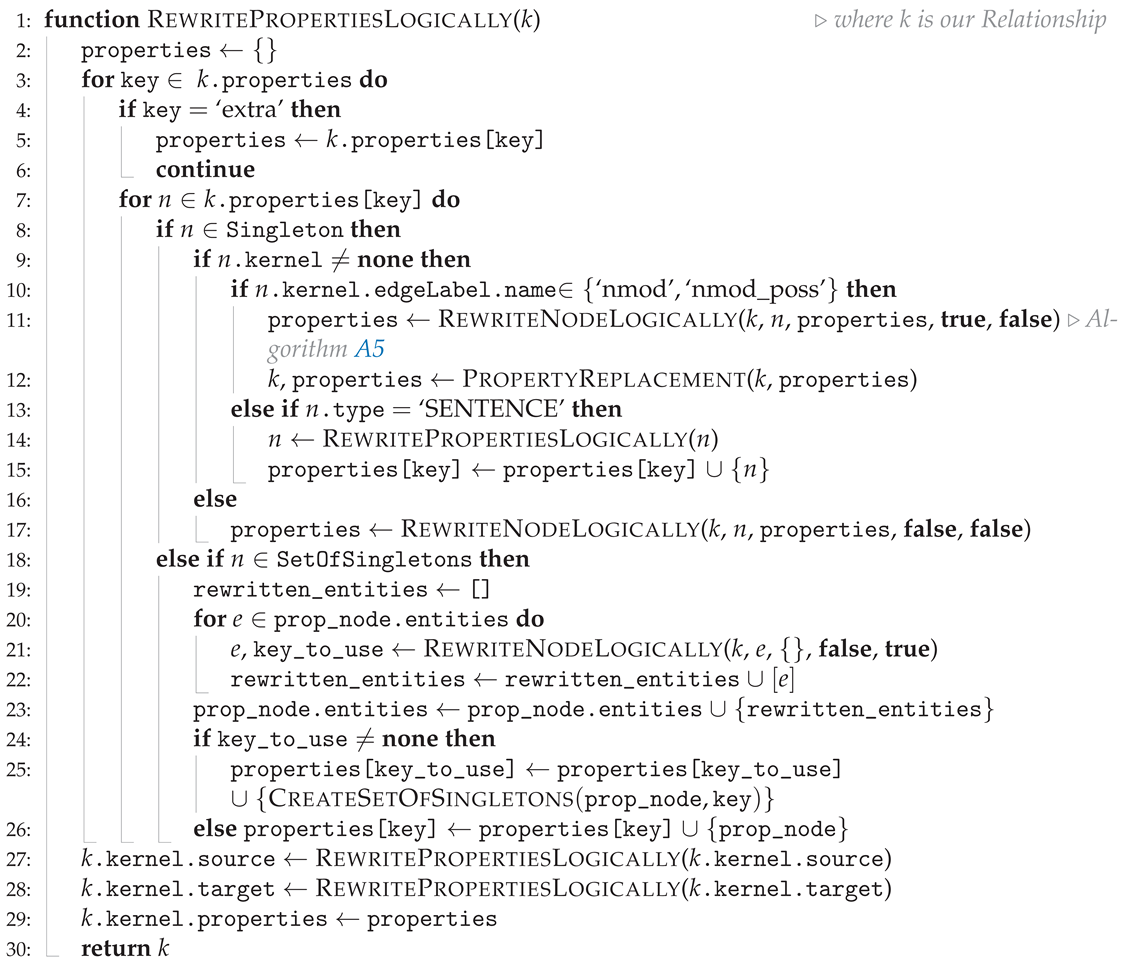

| Algorithm 3 Properties contained within the kernel at this stage are not entirely covered logically. Therefore, this function determines, under a set of rules within the text, how they should be rewritten and appended to the properties of the kernel in order to be properly represented. |

|

3.2.4. Final First-Order Logic (FOL) Representation

3.3. Ex Post

3.3.1. Sentence Transformers

3.3.2. Neural IR

3.3.3. Generative Large Language Models (LLM)

3.3.4. Simple Graphs (SGs) vs. Logical Graphs (LGs)

Simple Graphs (SGs)

Logical Graphs (LGs)

3.3.5. Logical Representation

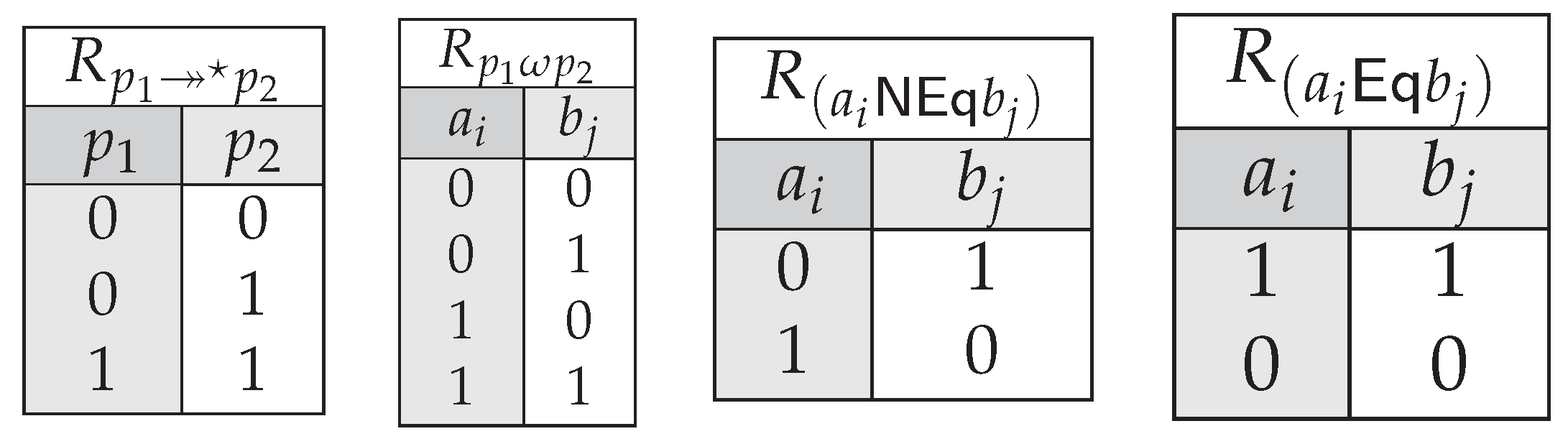

Tabular Semantics per Sentence

Determining General Implications Through Machine Teaching

- Equivalence:

- if is structurally equivalent to .

- Inconsistency:

- if either or is the explicit negation of the other, or whether their negation appears within the expansion of the other ( and , respectively).

- Implication:

- if occurs in one of the expansions .

4. Results

4.1. Theoretical Results

4.1.1. Cosine Similarity

4.1.2. Confidence Metrics

4.2. Clustering and Classification

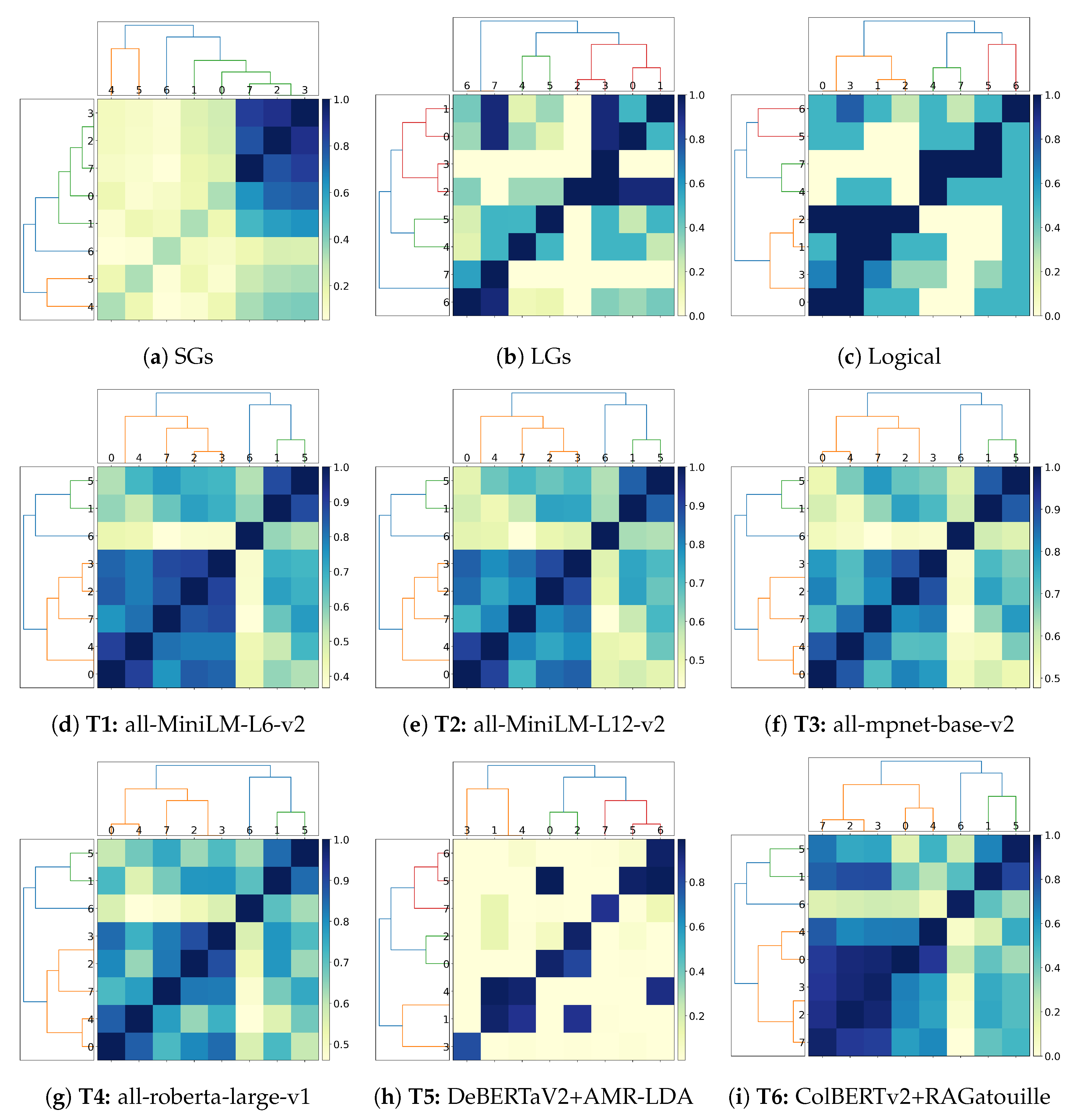

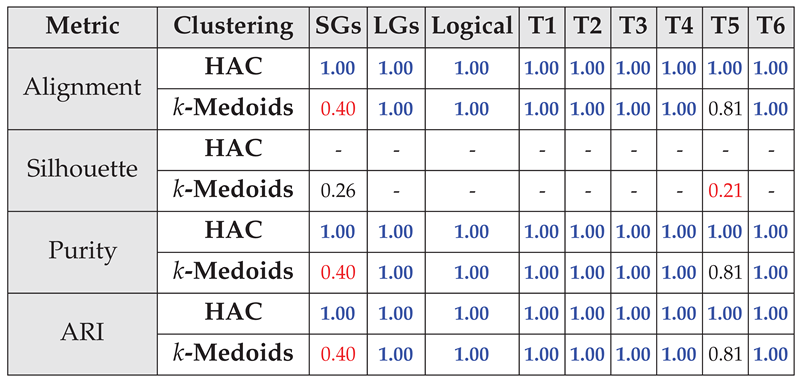

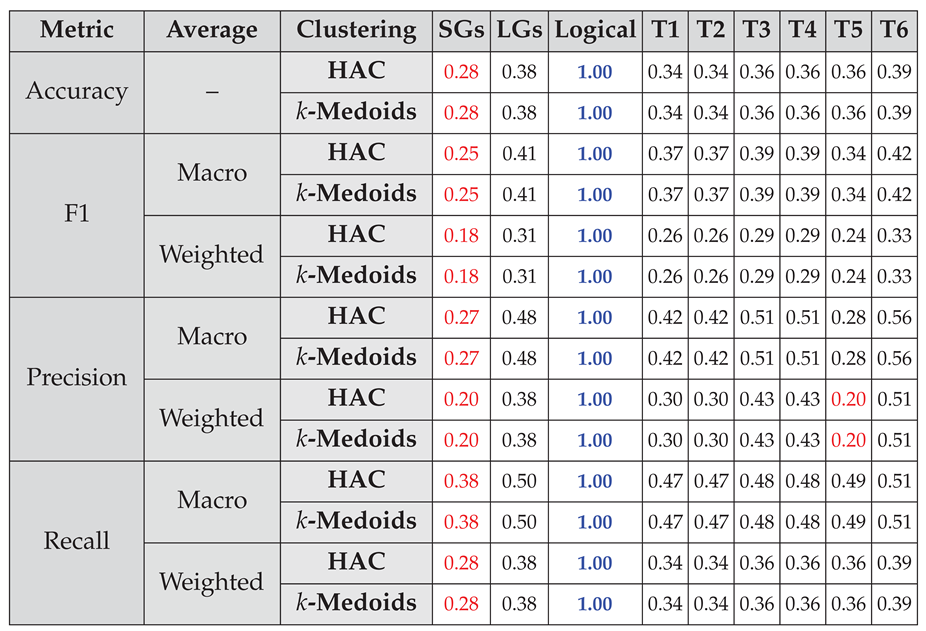

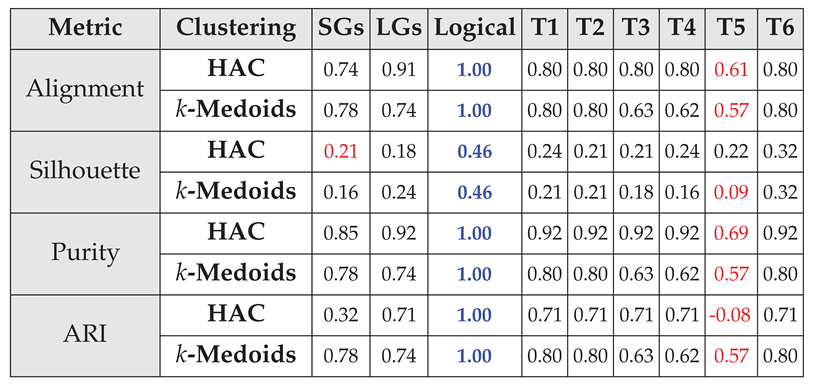

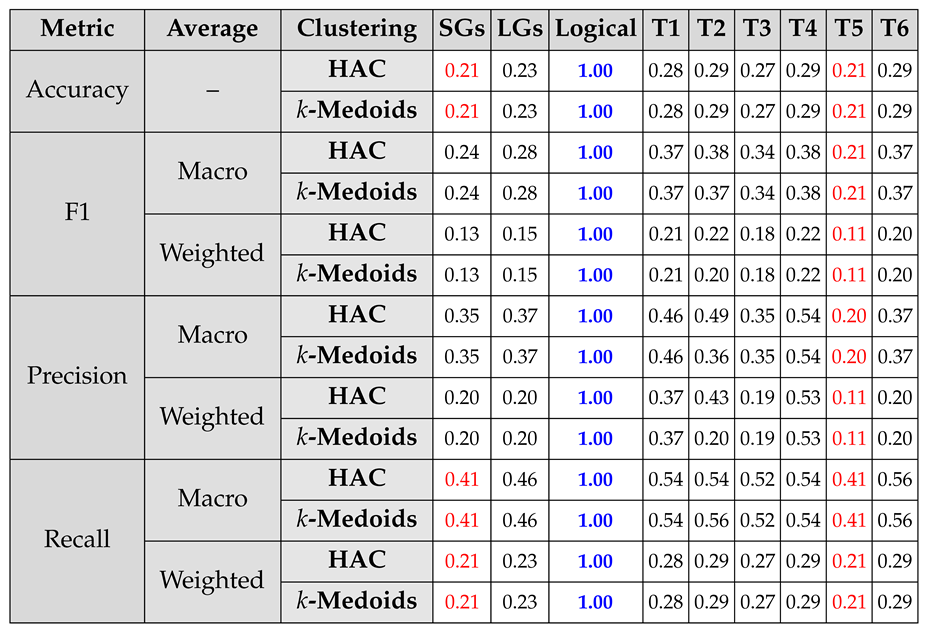

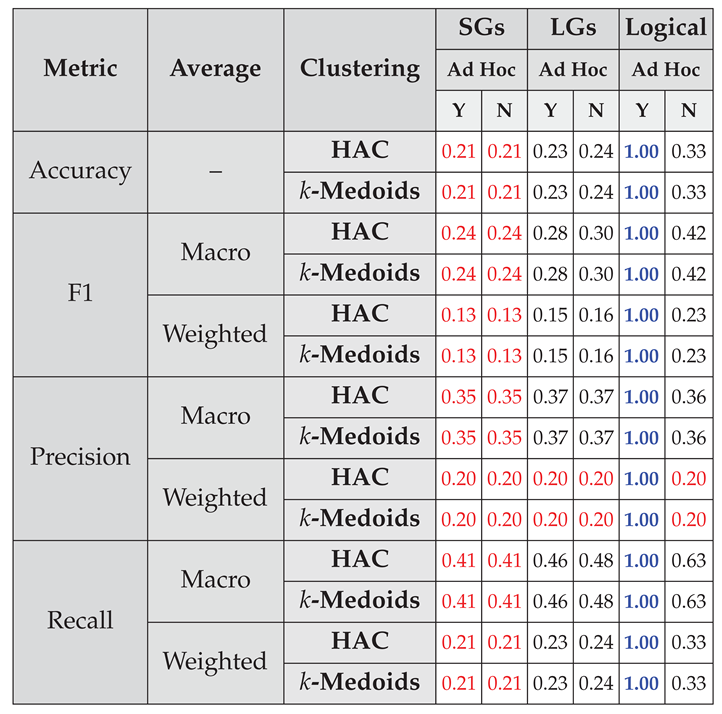

4.2.1. Capturing Logical Connectives and Reasoning

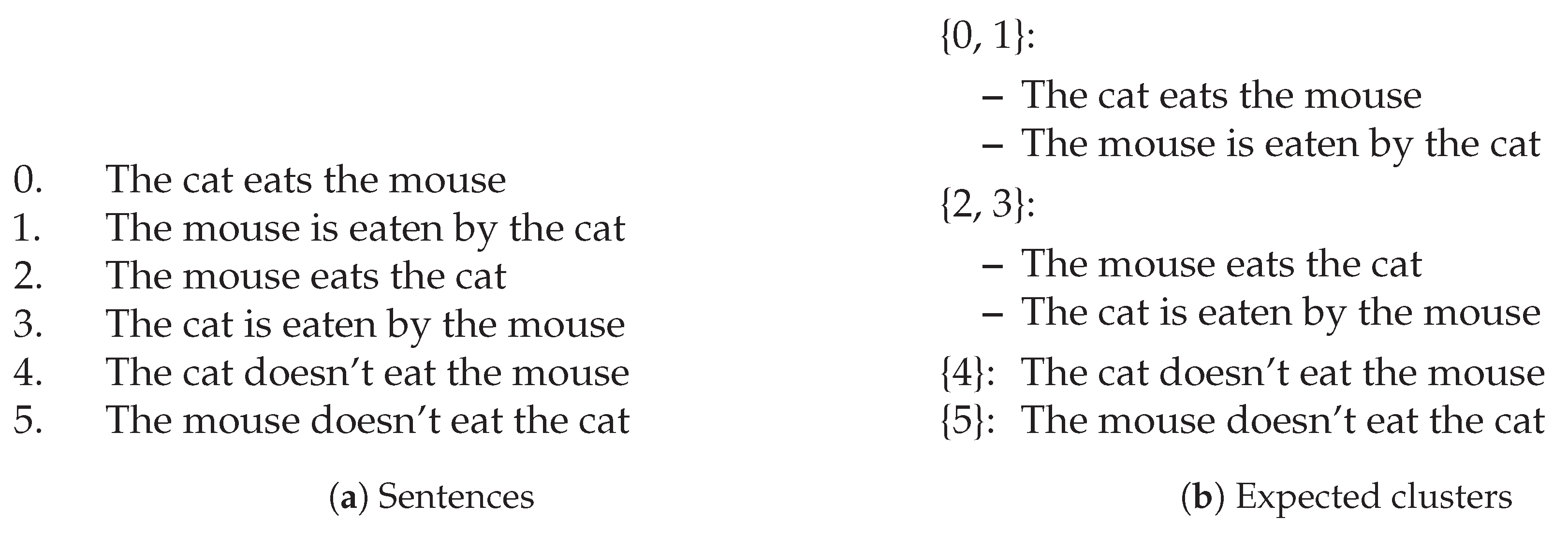

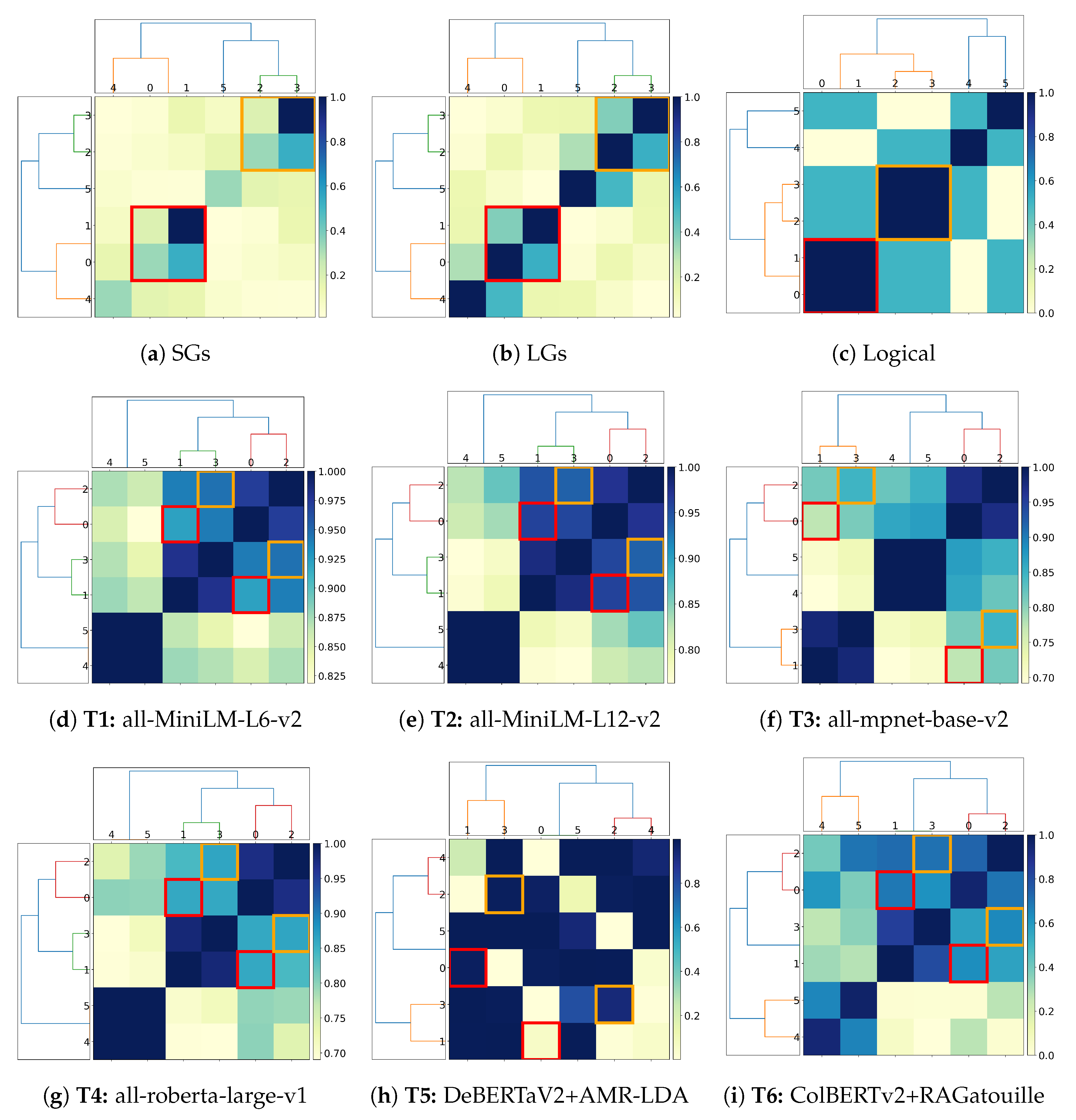

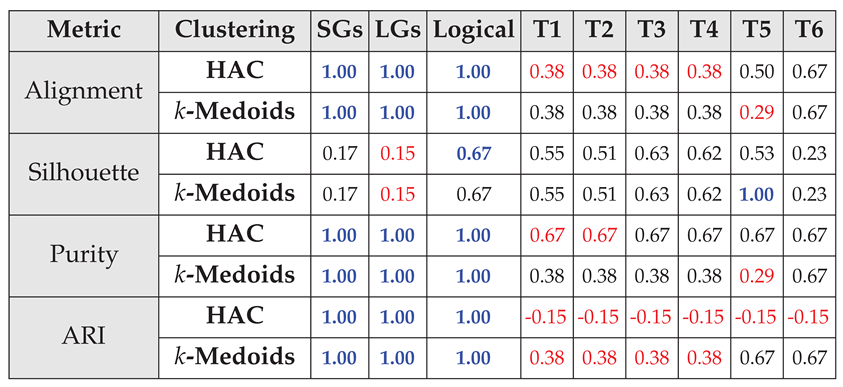

4.2.2. Capturing Simple Semantics and Sentence Structure

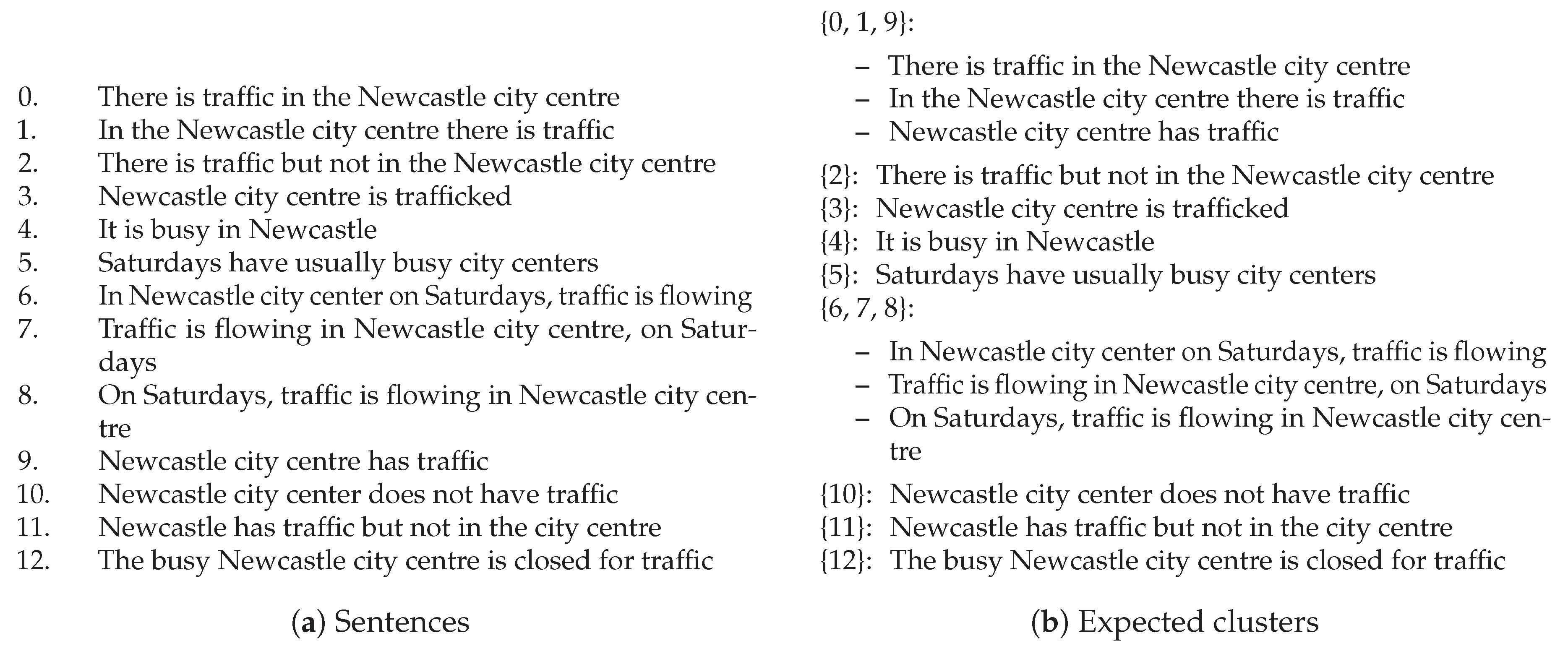

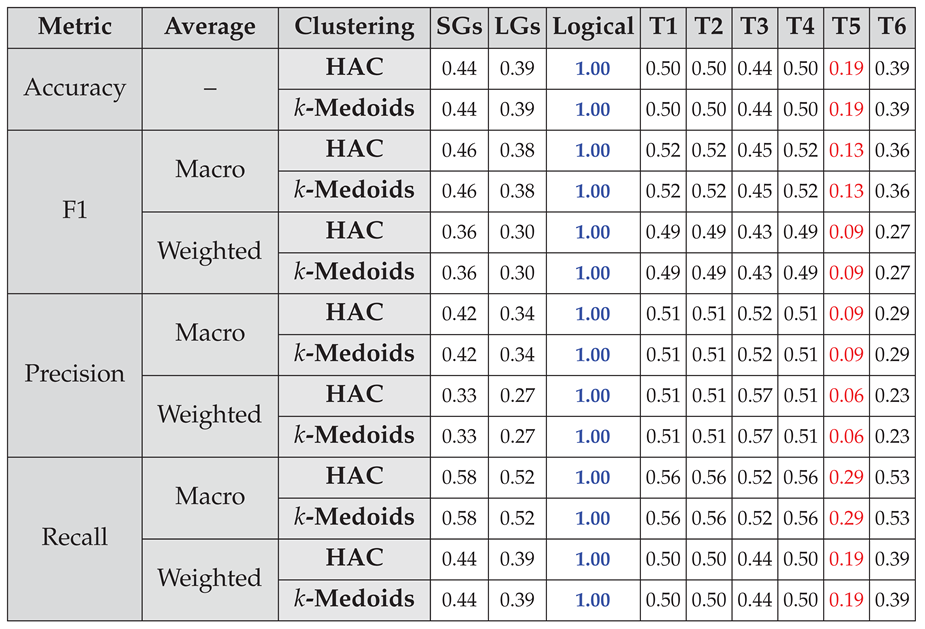

4.2.3. Capturing Simple Spatiotemporal Reasoning

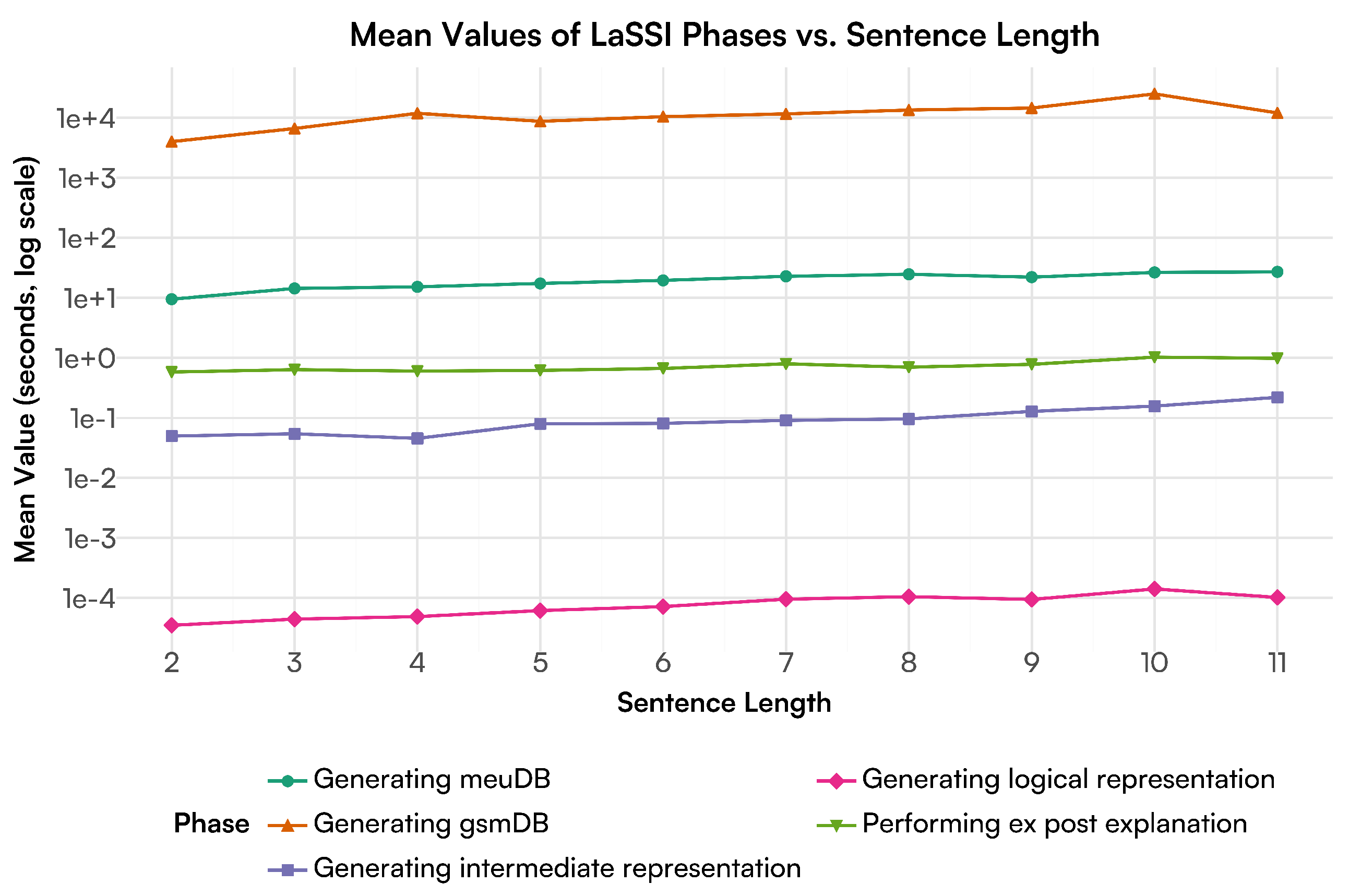

4.3. Sentence Scalability Rewriting

5. Discussion

5.1. Using Short Sentences

5.2. LaSSI Ablation Study

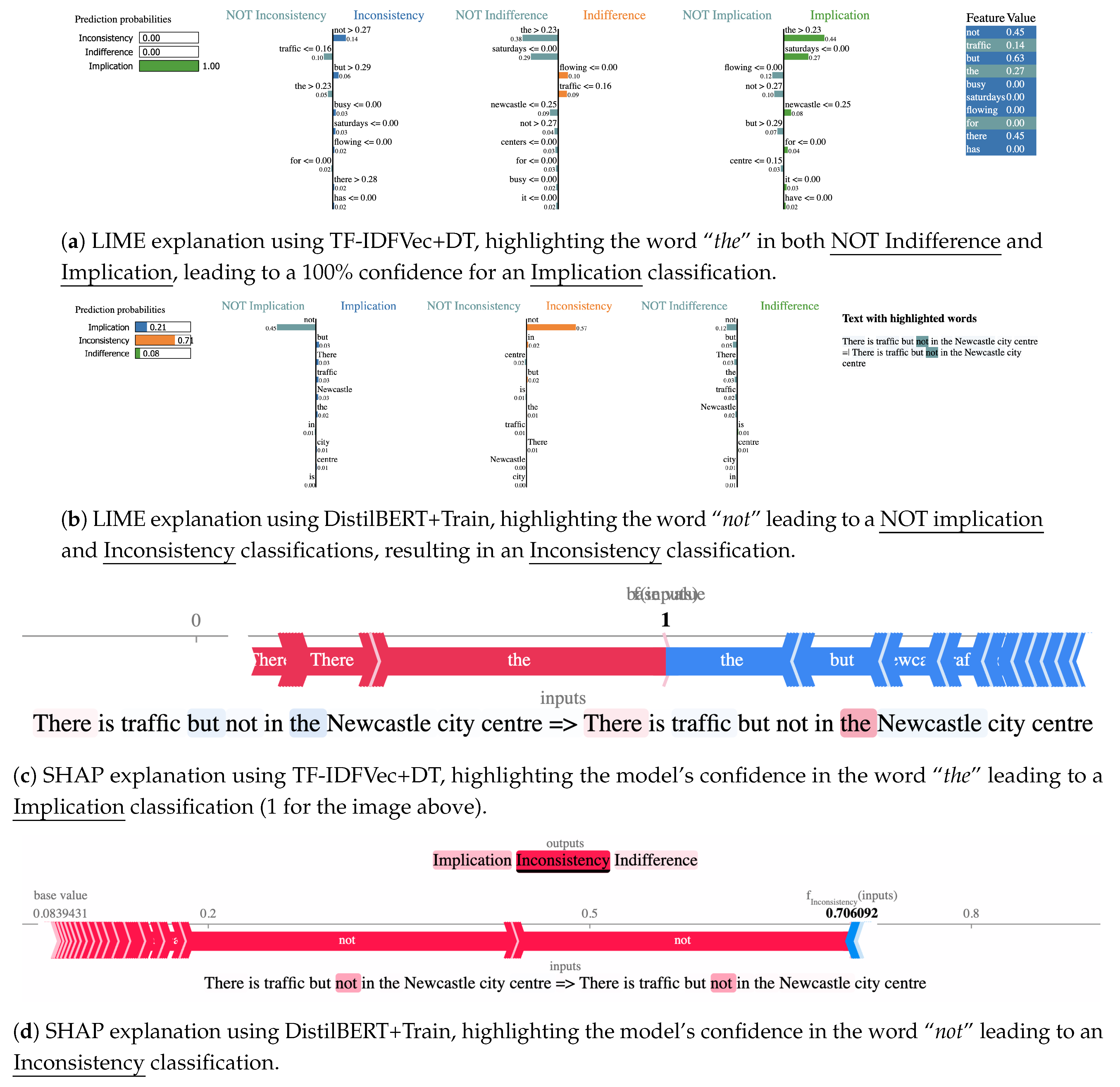

5.3. Explanability Study

5.3.1. Explicate Problem

5.3.2. Define Requirements

- Req №1

- The trained model used by the explainer should minimise the degradation of classification performances.

- Req №2

- The explainer should provide an intuitive explanation of the motivations why the text correlates with the classification outcome.

- Req №3

-

The explainer should derive connections between semantically entailing words towards the classification task.

- (a)

- The existence of one single feature should not be sufficient to derive the classification: when this occurs, the model will overfit a specific dataset rather than learning to understand the general context of the passage.

5.3.3. Design And Develop

- TF-IDFVec+DT:

- TF-IDF Vectorisation [100] is a straightforward approach to represent each document within a corpus as a vector, where each dimension describes the TF-IDF value [53] for each word in the document. After vectorising the corpus, we fit a Decision Tree (DT) for learning the correlation between word frequency and classification outcome. Stopwords such as “the” typically have high IDF scores, as they might frequently occur within the text. We retain all the occurring words to minimize our bias when training the classifier. As this violates Req №3(a), we decide to pair this mechanism with the following, being attention-based.

- DistilBERT+Train:

- DistilBERT [101] is a transformer model designed to be fine-tuned on tasks that use entire sentences (potentially masked) to make decisions [102]. It uses the WordPiece subword segmentation to extract features from the full text. We use this transformer to go beyond straightforward word tokenisation as the former. Thus, this approach will not violate Req №3(a) if the attention mechanism will not focus on one single word to draw conclusions, thus remarking their impossibility to draw correlations across the two sentences.

5.3.4. Artifact Evaluation

Performance Degradation

Intuitiveness

Explanation through Word Correlation

5.3.5. Final Considerations

6. Conclusions and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A. Generation of SetOfSingletons

Appendix A.1. Multi-Word Entities

Appendix A.2. Multiple Logical Functions

Appendix A.2.1. Handling Extras

Appendix B. Recursive Sentence Rewriting

Appendix B.1. Promoting Edges to Binary/Unary Relationships

| Algorithm A1 Edges collected from our a priori phase need to be analysed to ensure that they are all relevant and structured correctly, such that our kernel best represents the given full text. This function checks for prototypical prepositions within edge labels, in order to possibly rewrite targets of a number of edges. |

|

Appendix B.2. Identifying the Clause Node Entry Points

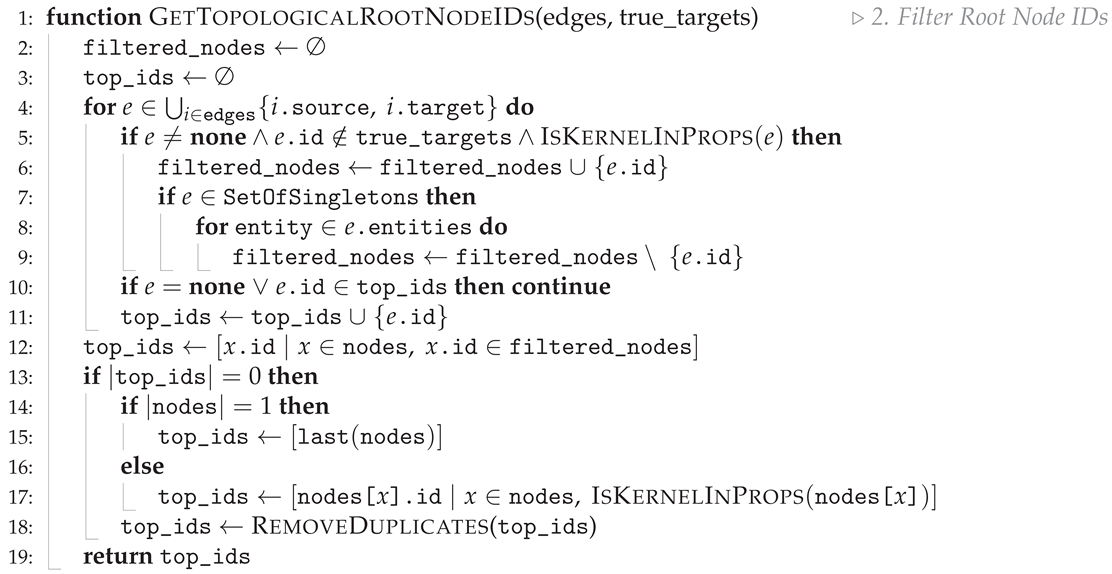

| Algorithm A2 To properly encompass the recursive nature of the sentence, we find the root IDs within the given edges in topological order, ensuring that we maintain structural understanding when rewriting the sentence. (Algorithm 2 cont.) |

|

Appendix B.3. Generating Binary Relationships (Kernels)

| Algorithm A3 Construct final relationship (kernel) (Algorithm 2 cont.) |

|

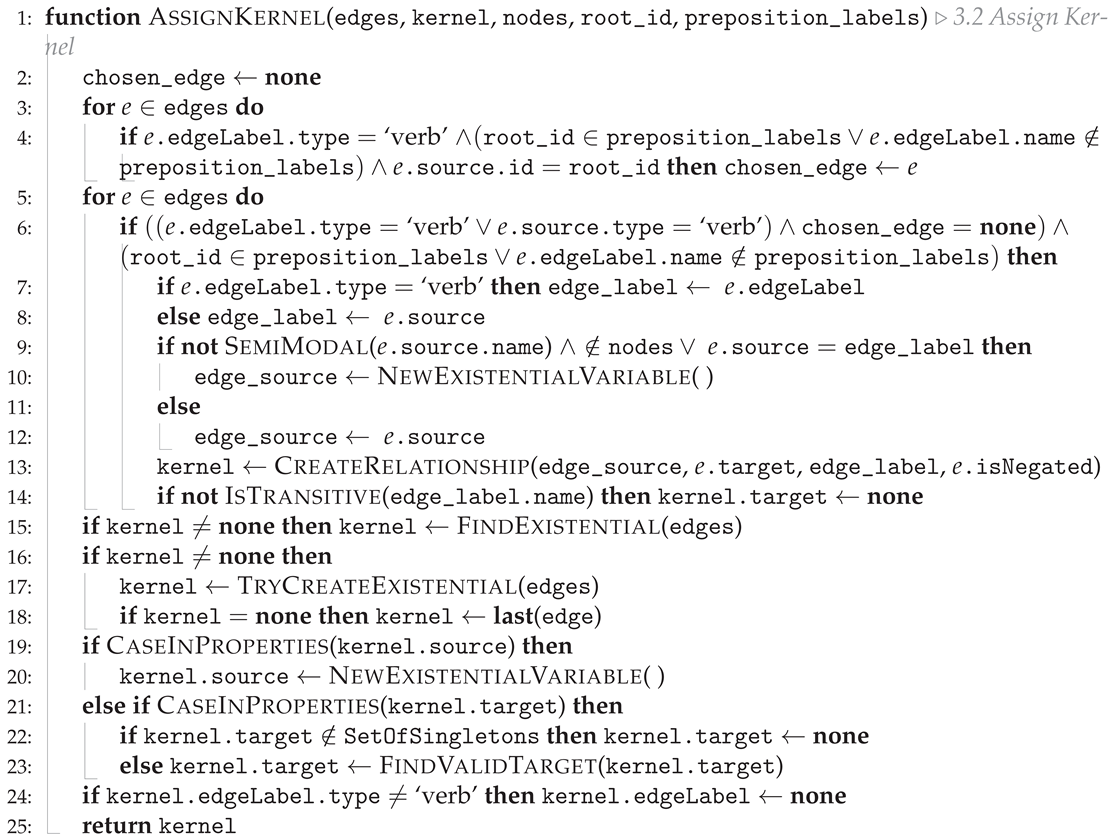

Appendix B.3.1. Kernel Assignment

| Algorithm A4 Given a list of edges, we find the most relevant edge (using a set of rules narrated in the text) that should be used as our kernel. (Algorithm A3 cont.) |

|

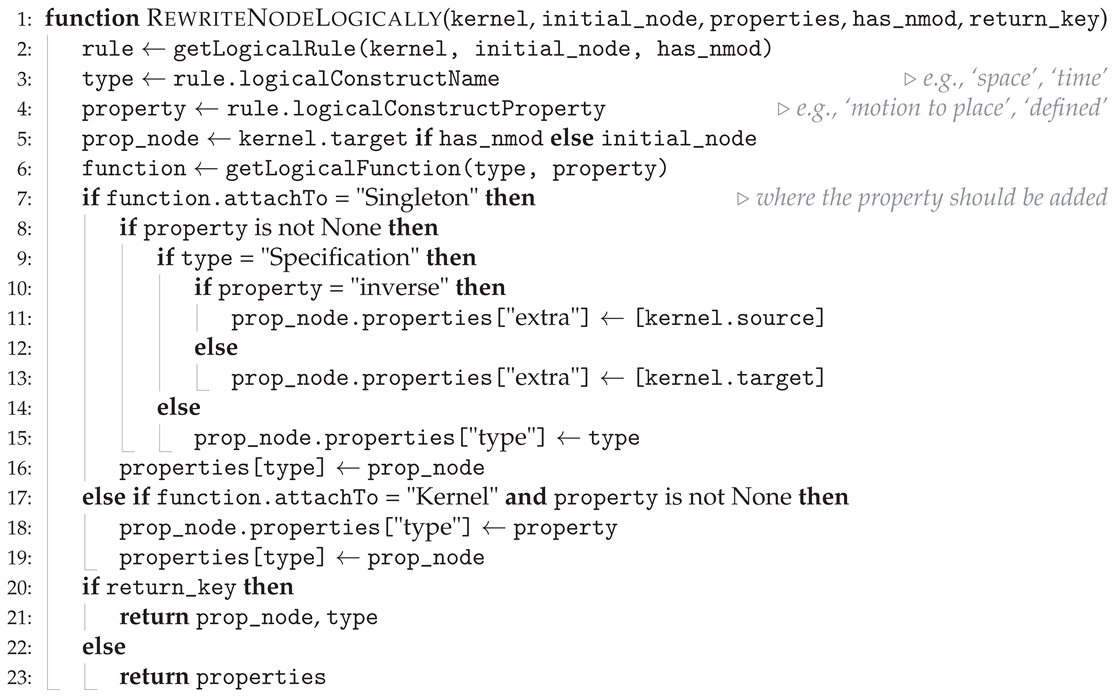

Appendix C. Rewriting Semantics for Logical Function Rules in Parmenides

| Algorithm A5 Given a node, taken from our kernel, we try to match a rule from our Parmenides ontology. From this rule we get the type which determines the rewriting function, that should be applied to the given node. This function also determines whether the rewriting should be added to the properties of the given Singleton, or to the entire kernel. |

|

Appendix D. Classical Semantics, Bag Semantics, and Relational Algebra

Appendix D.1. Enumerating the Set of Possible Worlds Holding for a Formula

Appendix D.2. Knowledge-Based Driven Propositional Semantics

- :

- If we lose specificity due to some missing copula information.

- :

- By interpreting a missing value from one of the property arguments as missing information entailing any possible value for this field, whether the right element is a non-missing value.

- :

- If we interpret the second object as a specific instance of the first one.

- ↠:

- A general implication state that cannot be easily categorised into any of the former cases while including any of them.

Appendix D.2.1. Multi-Valued Term Equivalence

Appendix D.2.2. Multi-Valued Proposition Equivalence

Appendix E. Proofs

- ⇒

- Left to right: If two equations are the same, they will have the same set of the possible worlds. Given this, their intersection will be always equivalent to one of the two sets, from which it can be derived that the support of either of the two formulas is always true.

- ⇐

- Right to left: When the confidence is 1, then by definition, both the numerator and denominator are of the same size. Therefore, and . By the commutativity of the intersection, we then derive that are of the same size and represent the same set. Thus, it holds that .

References

- Zhang, T.; et al. GAIA - A Multi-media Multi-lingual Knowledge Extraction and Hypothesis Generation System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Text Analysis Conference, TAC 2018, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA, November 13-14, 2018. NIST, 2018.

- Speer, R.; Chin, J.; Havasi, C. ConceptNet 5.5: An Open Multilingual Graph of General Knowledge. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, February 4-9, 2017, San Francisco, California, USA; Singh, S.; Markovitch, S., Eds. AAAI Press, 2017, pp. 4444–4451. [CrossRef]

- Auer, S.; Bizer, C.; Kobilarov, G.; Lehmann, J.; Cyganiak, R.; Ives, Z. DBpedia: A nucleus for a web of open data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 6th International The Semantic Web and 2nd Asian Conference on Asian Semantic Web Conference, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; ISWC’07/ASWC’07, p. 722–735.

- Mendes, P.; Jakob, M.; Bizer, C. DBpedia: A Multilingual Cross-domain Knowledge Base. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC`12); Calzolari, N.; Choukri, K.; Declerck, T.; Doğan, M.U.; Maegaard, B.; Mariani, J.; Moreno, A.; Odijk, J.; Piperidis, S., Eds., Istanbul, Turkey, 2012; pp. 1813–1817.

- Bergami, G. A framework supporting imprecise queries and data, 2019, [arXiv:cs.DB/1912.12531].

- Talmor, A.; Herzig, J.; Lourie, N.; Berant, J. CommonsenseQA: A Question Answering Challenge Targeting Commonsense Knowledge. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Burstein, J.; Doran, C.; Solorio, T., Eds., Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019; pp. 4149–4158. [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, C.K.; Wolz, M.; Knack, J.; Weyers, B.; Schenkel, R. SchenQL: In-depth analysis of a query language for bibliographic metadata. International Journal on Digital Libraries 2022, 23, 113–132. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jagadish, H.V. NaLIR: An interactive natural language interface for querying relational databases. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, New York, NY, USA, 2014; SIGMOD ’14, p. 709–712. [CrossRef]

- Tammet, T.; Järv, P.; Verrev, M.; Draheim, D. An Experimental Pipeline for Automated Reasoning in Natural Language (Short Paper). In Proceedings of the Automated Deduction – CADE 29; Pientka, B.; Tinelli, C., Eds., Cham, 2023; pp. 509–521.

- Bao, Q.; Peng, A.Y.; Deng, Z.; Zhong, W.; Gendron, G.; Pistotti, T.; Tan, N.; Young, N.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Abstract Meaning Representation-Based Logic-Driven Data Augmentation for Logical Reasoning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024; Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 5914–5934. [CrossRef]

- Dallachiesa, M.; Ebaid, A.; Eldawy, A.; Elmagarmid, A.; Ilyas, I.F.; Ouzzani, M.; Tang, N. NADEEF: A commodity data cleaning system. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, New York, NY, USA, 2013; SIGMOD ’13, p. 541–552.

- Andrzejewski, W.; Bębel, B.; Boiński, P.; Wrembel, R. On tuning parameters guiding similarity computations in a data deduplication pipeline for customers records: Experience from a R&D project. Information Systems 2024, 121, 102323.

- Picado, J.; Davis, J.; Termehchy, A.; Lee, G.Y. Learning Over Dirty Data Without Cleaning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Management of Data, SIGMOD Conference 2020, online conference [Portland, OR, USA], June 14-19, 2020; Maier, D.; Pottinger, R.; Doan, A.; Tan, W.; Alawini, A.; Ngo, H.Q., Eds. ACM, 2020, pp. 1301–1316.

- Bergami, G. A framework supporting imprecise queries and data. CoRR 2019, abs/1912.12531, [1912.12531].

- Virgilio, R.D.; Maccioni, A.; Torlone, R. Approximate querying of RDF graphs via path alignment. Distributed Parallel Databases 2015, 33, 555–581.

- Fox, O.R.; Bergami, G.; Morgan, G. LaSSI: Logical, Structural, and Semantic text Interpretation. In Proceedings of the Database Engineered Applications. Springer, 2025, IDEAS ’24 (in press).

- Wong, P.C.; Whitney, P.; Thomas, J. Visualizing Association Rules for Text Mining. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE Symposium on Information Visualization, USA, 1999; INFOVIS ’99, p. 120.

- Tsamoura, E.; Hospedales, T.; Michael, L. Neural-Symbolic Integration: A Compositional Perspective. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2021, 35, 5051–5060. [CrossRef]

- Raedt, L.D. Logical and Relational Learning; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2008.

- Picado, J.; Termehchy, A.; Fern, A.; Ataei, P. Logical scalability and efficiency of relational learning algorithms. The VLDB Journal 2019, 28, 147–171. [CrossRef]

- Niles, I.; Pease, A. Towards a standard upper ontology. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Formal Ontology in Information Systems, FOIS 2001, Ogunquit, Maine, USA, October 17-19, 2001, Proceedings. ACM, 2001, pp. 2–9. [CrossRef]

- Simard, P.Y.; Amershi, S.; Chickering, D.M.; Pelton, A.E.; Ghorashi, S.; Meek, C.; Ramos, G.A.; Suh, J.; Verwey, J.; Wang, M.; et al. Machine Teaching: A New Paradigm for Building Machine Learning Systems. CoRR 2017, abs/1707.06742, [1707.06742].

- Ramos, G.; Meek, C.; Simard, P.; Suh, J.; and, S.G. Interactive machine teaching: A human-centered approach to building machine-learned models. Human–Computer Interaction 2020, 35, 413–451. [CrossRef]

- Mosqueira-Rey, E.; Hernández-Pereira, E.; Alonso-Ríos, D.; Bobes-Bascarán, J.; Fernández-Leal, Á. Human-in-the-loop machine learning: A state of the art. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 3005–3054. [CrossRef]

- Seshia, S.A.; Sadigh, D.; Sastry, S.S. Toward verified artificial intelligence. Commun. ACM 2022, 65, 46–55.

- Bergami, G.; Fox, O.R.; Morgan, G., Extracting Specifications through Verified and Explainable AI: Interpretability, Interoperabiliy, and Trade-offs (In Press). In Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Trustworthy Decisions in Smart Applications; Springer; chapter 2.

- Ma, L.; Kang, H.; Yu, G.; Li, Q.; He, Q. Single-Domain Generalized Predictor for Neural Architecture Search System. IEEE Transactions on Computers 2024, 73, 1400–1413. [CrossRef]

- Zini, J.E.; Awad, M. On the Explainability of Natural Language Processing Deep Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 103:1–103:31. [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, J.; Yang, X.J.; Zhou, F. Combat COVID-19 infodemic using explainable natural language processing models. Information Processing & Management 2021, 58, 102569. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. Structure Regularization for Structured Prediction. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2014, December 8-13 2014, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Ghahramani, Z.; Welling, M.; Cortes, C.; Lawrence, N.D.; Weinberger, K.Q., Eds., 2014, pp. 2402–2410.

- "Manning, C.; Surdeanu, M.; Bauer, J.; Finkel, J.; Bethard, S.; McClosky, D. The Stanford CoreNLP Natural Language Processing Toolkit. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations; Bontcheva, K.; Zhu, J., Eds., Baltimore, Maryland, jun 2014; pp. 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Jurafsky, D.; Martin, J.H. Speech and Language Processing: An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition with Language Models, 3rd ed.; 2025. Online manuscript released January 12, 2025.

- Nivre, J.; et al. conj. Available online: https://universaldependencies.org/en/dep/conj.html (accessed on 13.02.2025).

- Nivre, J.; et al. cc. Available online: https://universaldependencies.org/en/dep/cc.html (accessed on 13.02.2025).

- Chen, D.; Manning, C.D. A Fast and Accurate Dependency Parser using Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2014, October 25-29, 2014, Doha, Qatar, A meeting of SIGDAT, a Special Interest Group of the ACL; Moschitti, A.; Pang, B.; Daelemans, W., Eds. ACL, 2014, pp. 740–750. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.; Vlachos, A.; Naradowsky, J. Noise reduction and targeted exploration in imitation learning for Abstract Meaning Representation parsing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Erk, K.; Smith, N.A., Eds., Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Stanford NLP Group. The Stanford Natural Language Processing Group. Available online: https://nlp.stanford.edu/software/lex-parser.shtml (accessed on 24.02.2025).

- Cardona, G. Pāṇini – His Work and its Traditions, 2 ed.; Vol. 1, Motilal Banarsidass: London, 1997.

- Christensen, C.H. Arguments for and against the Idea of Universal Grammar. Leviathan: Interdisciplinary Journal in English 2019, p. 12–28. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, M.D.; Chomsky, N.; Fitch, W.T. The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, and How Did It Evolve? Science 2002, 298, 1569–1579, [https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/science.298.5598.1569]. [CrossRef]

- Bergami, G., On Nesting Graphs. In A new Nested Graph Model for Data Integration; University of Bologna, Italy; chapter 7, pp. 195–220. PhD thesis.

- Montague, R., ENGLISH AS A FORMAL LANGUAGE. In Logic and philosophy for linguists; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Boston, 1975; pp. 94–121. [CrossRef]

- Montague, R. English as a formal language. In Linguaggi nella Societa e nella Tecnica; Edizioni di Communità: Milan, Italy, 1970; pp. 189–224.

- Dardano, M.; Trifone, P. Italian grammar with linguistics notions (in Italian); Zanichelli: Milan, 2002.

- terdon. terminology - Syntactic analysis in English: Correspondence between Italian complements and English ones. Available online: https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/628592/syntactic-analysis-in-english-correspondence-between-italian-complements-and/628597#628597 (accessed on 10.02.2025).

- Song, K.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Lu, J.; Liu, T. MPNet: Masked and Permuted Pre-training for Language Understanding, 2020.

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach, 2019, [arXiv:cs.CL/1907.11692].

- Wang, W.; Bao, H.; Huang, S.; Dong, L.; Wei, F. MiniLMv2: Multi-Head Self-Attention Relation Distillation for Compressing Pretrained Transformers. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; Zong, C.; Xia, F.; Li, W.; Navigli, R., Eds., Online, 2021; pp. 2140–2151. [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, K.; Khattab, O.; Saad-Falcon, J.; Potts, C.; Zaharia, M. ColBERTv2: Effective and Efficient Retrieval via Lightweight Late Interaction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; Carpuat, M.; de Marneffe, M.C.; Meza Ruiz, I.V., Eds., Seattle, United States, 2022; pp. 3715–3734. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.u.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I.; Luxburg, U.V.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017, Vol. 30.

- Gonen, H.; Blevins, T.; Liu, A.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Smith, N.A. Does Liking Yellow Imply Driving a School Bus? Semantic Leakage in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers); Chiruzzo, L.; Ritter, A.; Wang, L., Eds., Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2025; pp. 785–798.

- Strobl, L.; Merrill, W.; Weiss, G.; Chiang, D.; Angluin, D. What Formal Languages Can Transformers Express? A Survey. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2024, 12, 543–561.

- Manning, C.D.; Raghavan, P.; Schütze, H. Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Hicks, M.T.; Humphries, J.; Slater, J. ChatGPT is bullshit. Ethics and Information Technology 2024, 26, 38.

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, New York, NY, USA, 2021; FAccT ’21, p. 610–623.

- Chen, Y.; Wang, D.Z. Knowledge expansion over probabilistic knowledge bases. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management of Data, SIGMOD 2014, Snowbird, UT, USA, June 22-27, 2014; Dyreson, C.E.; Li, F.; Özsu, M.T., Eds. ACM, 2014, pp. 649–660.

- Kyburg, H.E. Probability and the Logic of Rational Belief; Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, CT, USA, 1961.

- Brown, B. Inconsistency measures and paraconsistent consequence. In Measuring Inconsistency in Information; Grant, J.; Martinez, M.V., Eds.; College Press, 2018; chapter 8, pp. 219–234.

- Graydon, M.S.; Lehman, S.M. Examining Proposed Uses of LLMs to Produce or Assess Assurance Arguments. NTRS - NASA Technical Reports Server.

- Ahlers, D. Assessment of the accuracy of GeoNames gazetteer data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th Workshop on Geographic Information Retrieval, New York, NY, USA, 2013; GIR ’13, p. 74–81.

- Chang, A.X.; Manning, C. SUTime: A library for recognizing and normalizing time expressions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC`12); Calzolari, N.; Choukri, K.; Declerck, T.; Doğan, M.U.; Maegaard, B.; Mariani, J.; Moreno, A.; Odijk, J.; Piperidis, S., Eds., Istanbul, Turkey, 2012; pp. 3735–3740.

- Qi, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bolton, J.; Manning, C.D. Stanza: A Python Natural Language Processing Toolkit for Many Human Languages. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, 2020.

- Speer, R.; Chin, J.; Havasi, C. ConceptNet 5.5: An open multilingual graph of general knowledge. In Proceedings of the AAAI. AAAI Press, 2017, AAAI’17, p. 4444–4451.

- Group, T.P.G.D. PostgreSQL: Documentation: 17: F.16. fuzzystrmatch — determine string similarities and distanceAppendix F. Additional Supplied Modules and Extensions. Available online: https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/fuzzystrmatch.html (accessed on 18.02.2025).

- Bergami, G.; Fox, O.R.; Morgan, G. Matching and Rewriting Rules in Object-Oriented Databases. Mathematics 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Junghanns, M.; Petermann, A.; Rahm, E. Distributed Grouping of Property Graphs with Gradoop. In Proceedings of the Datenbanksysteme für Business, Technologie und Web (BTW 2017), 17. Fachtagung des GI-Fachbereichs ,,Datenbanken und Informationssysteme" (DBIS), 6.-10. März 2017, Stuttgart, Germany, Proceedings; Mitschang, B.; Nicklas, D.; Leymann, F.; Schöning, H.; Herschel, M.; Teubner, J.; Härder, T.; Kopp, O.; Wieland, M., Eds. GI, 2017, Vol. P-265, LNI, pp. 103–122.

- Bergami, G.; Zegadło, W. Towards a Generalised Semistructured Data Model and Query Language. SIGWEB Newsl. 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bonifati, A.; Murlak, F.; Ramusat, Y. Transforming Property Graphs, 2024, [arXiv:cs.DB/2406.13062].

- Bergami, G.; Fox, O.R.; Morgan, G. Matching and Rewriting Rules in Object-Oriented Databases. Preprints 2024. [CrossRef]

- 2025, C.U.P..A. Modality: forms - Grammar - Cambridge Dictionary. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/grammar/british-grammar/modality-forms#:~:text=Dare%2C%20need%2C%20ought%20to%20and%20used%20to%20(semi%2Dmodal%20verbs) (accessed on 17.03.2025).

- Nivre, J.; et al. case. Available online: https://universaldependencies.org/en/dep/case.html (accessed on 05.03.2025).

- Nivre, J.; et al. nmod. Available online: https://universaldependencies.org/en/dep/nmod.html (accessed on 05.03.2025).

- Jatnika, D.; Bijaksana, M.A.; Suryani, A.A. Word2Vec Model Analysis for Semantic Similarities in English Words. In Proceedings of the Enabling Collaboration to Escalate Impact of Research Results for Society: The 4th International Conference on Computer Science and Computational Intelligence, ICCSCI 2019, 12-13 September 2019, Yogyakarta, Indonesia; Budiharto, W., Ed. Elsevier, 2019, Vol. 157, Procedia Computer Science, pp. 160–167. [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2013, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA, May 2-4, 2013, Workshop Track Proceedings; Bengio, Y.; LeCun, Y., Eds., 2013.

- Rosenberger, J.; Wolfrum, L.; Weinzierl, S.; Kraus, M.; Zschech, P. CareerBERT: Matching resumes to ESCO jobs in a shared embedding space for generic job recommendations. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 275, 127043. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bao, H.; Xu, D. Concept Vector for Similarity Measurement Based on Hierarchical Domain Structure. Comput. Informatics 2011, 30, 881–900.

- Nickel, M.; Kiela, D. Poincaré Embeddings for Learning Hierarchical Representations. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, December 4-9, 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA; Guyon, I.; von Luxburg, U.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.M.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.V.N.; Garnett, R., Eds., 2017, pp. 6338–6347.

- Asperti, A.; Ciabattoni, A. Logica ad Informatica.

- Bergami, G. A new Nested Graph Model for Data Integration. PhD thesis, University of Bologna, Italy, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Carnielli, W.; Esteban Coniglio, M. Paraconsistent Logic: Consistency, Contradiction and Negation; Springer: Switzerland, 2016.

- Hinman, P.G. Fundamentals of Mathematical Logic; A K Peters/CRC Press, 2005.

- Hugging Face. sentence-transformers (Sentence Transformers. Available online: https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers (accessed on 24.02.2025).

- Zaki, M.J.; Meira, Jr, W. Data Mining and Machine Learning: Fundamental Concepts and Algorithms, 2 ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Arthur, D.; Vassilvitskii, S. k-means++: The advantages of careful seeding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, SODA 2007, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, January 7-9, 2007; Bansal, N.; Pruhs, K.; Stein, C., Eds. SIAM, 2007, pp. 1027–1035.

- Kleene, S.C. Introduction to Metamathematics; P. Noordhoff N.V.: Groningen, 1952.

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 1987, 20, 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.V.; Epps, J.; Bailey, J. Information Theoretic Measures for Clusterings Comparison: Variants, Properties, Normalization and Correction for Chance. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2010, 11, 2837–2854. [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, E.J.; O’Neil, P.E.; Weikum, G. The LRU-K Page Replacement Algorithm For Database Disk Buffering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1993 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Washington, DC, USA, May 26-28, 1993; Buneman, P.; Jajodia, S., Eds. ACM Press, 1993, pp. 297–306. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Shasha, D.E. 2Q: A Low Overhead High Performance Buffer Management Replacement Algorithm. In Proceedings of the VLDB’94, Proceedings of 20th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases, September 12-15, 1994, Santiago de Chile, Chile; Bocca, J.B.; Jarke, M.; Zaniolo, C., Eds. Morgan Kaufmann, 1994, pp. 439–450.

- Harrison, J. Handbook of Practical Logic and Automated Reasoning; Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Simon, H.A. The Science of Design: Creating the Artificial. Design Issues 1988, 4, 67–82.

- Johannesson, P.; Perjons, E. An Introduction to Design Science; Springer, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Dewi, C.; Tsai, B.J.; Chen, R.C. Shapley Additive Explanations for Text Classification and Sentiment Analysis of Internet Movie Database. In Proceedings of the Recent Challenges in Intelligent Information and Database Systems; Szczerbicki, E.; Wojtkiewicz, K.; Nguyen, S.V.; Pietranik, M.; Krótkiewicz, M., Eds., Singapore, 2022; pp. 69–80.

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, NeurIPS 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, November 28 - December 9, 2022; Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; Oh, A., Eds., 2022.

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. "Why Should I Trust You?": Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, August 13-17, 2016; Krishnapuram, B.; Shah, M.; Smola, A.J.; Aggarwal, C.C.; Shen, D.; Rastogi, R., Eds. ACM, 2016, pp. 1135–1144.

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Anchors: High-Precision Model-Agnostic Explanations. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2018, 32.

- Visani, G.; Bagli, E.; Chesani, F. OptiLIME: Optimized LIME Explanations for Diagnostic Computer Algorithms. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the CIKM 2020 Workshops co-located with 29th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM 2020), Galway, Ireland, October 19-23, 2020; Conrad, S.; Tiddi, I., Eds. CEUR-WS.org, 2020, Vol. 2699, CEUR Workshop Proceedings.

- Watson, D.S.; O’Hara, J.; Tax, N.; Mudd, R.; Guy, I. Explaining Predictive Uncertainty with Information Theoretic Shapley Values. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, NeurIPS 2023, New Orleans, LA, USA, December 10 - 16, 2023; Oh, A.; Naumann, T.; Globerson, A.; Saenko, K.; Hardt, M.; Levine, S., Eds., 2023.

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; NIPS’17, p. 4768–4777.

- Bengfort, B.; Bilbro, R.; Ojeda, T. Applied Text Analysis with Python: Enabling Language-Aware Data Products with Machine Learning, 1st ed.; O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2018.

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. CoRR 2019, abs/1910.01108, [1910.01108].

- Bai, J.; Cao, R.; Ma, W.; Shinnou, H. Construction of Domain-Specific DistilBERT Model by Using Fine-Tuning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technologies and Applications of Artificial Intelligence, TAAI 2020, Taipei, Taiwan, December 3-5, 2020. IEEE, 2020, pp. 237–241. [CrossRef]

- Crabbé, J.; van der Schaar, M. Evaluating the robustness of interpretability methods through explanation invariance and equivariance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2023; NIPS ’23.

- Slack, D.; Hilgard, S.; Jia, E.; Singh, S.; Lakkaraju, H. Fooling LIME and SHAP: Adversarial Attacks on Post hoc Explanation Methods. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, New York, NY, USA, 2020; AIES ’20, p. 180–186. [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, J.B.; Wish, M. Multidimensional Scaling; Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Mead, A. Review of the Development of Multidimensional Scaling Methods. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series D (The Statistician) 1992, 41, 27–39.

- Agarwal, S.; Wills, J.; Cayton, L.; Lanckriet, G.R.G.; Kriegman, D.J.; Belongie, S.J. Generalized Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, AISTATS 2007, San Juan, Puerto Rico, March 21-24, 2007; Meila, M.; Shen, X., Eds. JMLR.org, 2007, Vol. 2, JMLR Proceedings, pp. 11–18.

- Quist, M.; Yona, G. Distributional Scaling: An Algorithm for Structure-Preserving Embedding of Metric and Nonmetric Spaces. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2004, 5, 399–420.

- Costa, C.F.; Nascimento, M.A.; Schubert, M. Diverse nearest neighbors queries using linear skylines. GeoInformatica 2018, 22, 815–844. [CrossRef]

- Botea, V.; Mallett, D.; Nascimento, M.A.; Sander, J. PIST: An Efficient and Practical Indexing Technique for Historical Spatio-Temporal Point Data. GeoInformatica 2008, 12, 143–168. [CrossRef]

- Hopcroft, J.E.; Ullman, J.D. Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages and Computation; Addison-Wesley, 1979.

- Nivre, J.; et al. dep. Available online: https://universaldependencies.org/en/dep/dep.html (accessed on 27.02.2025).

- Weber, D. English Prepositions in the History of English Grammar Writing. AAA: Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 2012, 37, 227–243.

- Asperti, A.; Ricciotti, W.; Sacerdoti Coen, C. Matita Tutorial. Journal of Formalized Reasoning 2014, 7, 91–199. [CrossRef]

- Defays, D. An efficient algorithm for a complete link method. The Computer Journal 1977, 20, 364–366, [https://academic.oup.com/comjnl/article-pdf/20/4/364/1108735/200364.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F., Hierarchical Clustering. In Introduction to HPC with MPI for Data Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 195–211. [CrossRef]

- Partitioning Around Medoids (Program PAM). In Finding Groups in Data; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1990; chapter 2, pp. 68–125, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9780470316801.ch2]. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, J.; Kshirsagar, R.; Abidin, D.; Griffin, J.; Kanarachos, S.; James, J.; Alamaniotis, M.; Fitzpatrick, M. A comparison of machine learning methods to classify radioactive elements using prompt-gamma-ray neutron activation data. [CrossRef]

- Nivre, J.; et al. English Dependency Relations. Available online: https://universaldependencies.org/en/dep/ (accessed on 24.02.2025).

| 1 | The previous phase provided a preliminary rewriting, where a new relationship is derived from each verb occurring within the pipeline and connecting the agents performing and receiving the action; information concerning additional entities and pronouns occurring within the sentence is collected among the properties associated with the relationship. |

| 2 | See Appendix D.2 for further details on this notation. |

| Logical Function | (Sub)Type | Example (underlined) |

|---|---|---|

| Space | Stay in place | “I sit on a tree.” |

| Space | Motion to place | “I go to Bologna.” |

| Space | Motion from place | “I come from Italy.” |

| Space | Motion through place | “Going across the city center.” |

| Cause | – | “Newcastle is closed for congestion” |

| Time | Continuous | “The traffic lasted for hours” |

| Time | Defined | “On Saturdays, traffic is flowing” |

| Sentence Transformers (Section 2.4.1) | Neural IR (Section 2.4.2) | Generative LLM (Section 2.4.3) | GEVAI (Section 2.1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPNet [46] | RoBERTa [47] | MiniLMv2 [48] | ColBERTv2 [49] | DeBERTaV2+AMR-LDA [10] | LaSSI (This Paper) | |

| Task | Document Similarity | Query Answering | Entailment Classification | Paraconsistent Reasoning | ||

| Sentence pre-processing | Word Tokenisation + Position Encoding | •AMR with Multi-Word Entity Recognition •AMR Rewriting |

•Dependency Parsing •Generalised Graph Grammars •Multi-Word Entity Recognition •Logic Function Rewriting |

|||

| Similarity/Relationship inference |

Permutated Language Modelling |

– | Annotated Training Dataset |

Factored by Tokenisation |

•Logical Prompts •Contrastive Learning |

•Knowledge Base-driven Similarity •TBox Reasoning |

| Learning Strategy | Static Masking | Dynamic Masking | Annotated Training Dataset |

•Autoregression •Sentence Distance Minimisation |

||

| Final Representation | One vector per sentence | Many vectors per sentence | Classification outcome | Extended First-Order Logic (FOL) | ||

| Pros | Deriving Semantic Similarity through Learning | Generalisation of document matching |

Deriving Logical Entailment through Learning | •Reasoning Traceability •Paraconsistent Reasoning •Non biased by documents |

||

| Cons | •Cannot express propositional calculus •Semantic similarity does not entail implication capturing |

•Inadequacy of AMR Representation •Reasoning limited by Logical Prompts •Biased by probabilistic reasoning |

Heavily Relies on Upper Ontology | |||

| #W | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| #2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| #3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| #4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Accuracy | F1 | Precision | Recall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macro | Weighted | Macro | Weigthed | Macro | Weighted | ||

| TF-IDFVec+DT | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.94 |

| DistilBERT+Train | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.76 |

| Explainer | Model | Req №1 | Req №2 | Req №3 | Req №3(a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAP | TF-IDFVec+DT | ◐ | • | ◐ | ○ |

| DistilBERT+Train | ○ | • | ◐ | ○ | |

| LIME | TF-IDFVec+DT | ◐ | • | ◐ | ○ |

| DistilBERT+Train | ○ | • | ◐ | ○ | |

| LaSSI | • | ○ | • | • | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).