1. Introduction

The advent of Transformer-based language models has revolutionized the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP). These language models, exemplified by the likes of BERT [

1], GPT [

2], and their successors [

3], have achieved unprecedented success across a wide array of NLP benchmarks. Their ability to learn from vast dataSET has enabled them to capture subtle nuances of language, making them highly effective in tasks ranging from text classification to question-answering [

4,

5,

6].

Despite their success, a critical aspect of language understanding—syntactic structure—has been largely overlooked in the design of these models. Classical linguistic theories, dating back to the pioneering work of Chomsky [

7], emphasize the importance of hierarchical syntactic structures in understanding language. These structures underpin the grammatical organization of sentences, contributing significantly to the meaning and coherence of linguistic expressions. However, Transformer models, which primarily focus on sequential patterns in text, do not inherently capture these hierarchical structures.

This gap in syntactic modeling raises a pivotal question: Can the integration of syntactic structure into Transformer models enhance their linguistic comprehension and performance? This question is particularly pertinent considering the success of smaller-scale models, like recurrent neural network grammars (RNNGs) [

10], in capturing syntactic nuances. RNNGs and similar models have demonstrated the utility of syntactic parsing in understanding complex sentence structures, especially in tasks where understanding the underlying grammar is crucial. However, these models often struggle to scale to the size of dataSET that Transformers are typically trained on, limiting their practical application in large-scale NLP tasks.

In response to this challenge, we introduce Syntax-Enhanced Transformer Models (SET). SET represent a novel class of Transformer models that integrate deep syntactic parsing into the Transformer architecture. This integration is achieved through a dual approach: (i) enhancing the Transformer’s attention mechanism to account for syntactic structures and (ii) incorporating a deterministic process for transforming linearized parse trees. This approach allows SET to harness the Transformer’s ability to process large-scale data while also capturing the intricate syntactic structures that underpin language comprehension.

Our work is inspired by recent efforts to augment Transformer models with syntactic understanding [

11]. However, SET differ significantly in their approach. Unlike previous works that have primarily focused on modifying attention heads to be syntax-sensitive, SET embed a more profound syntactic inductive bias. This is achieved by explicitly constructing representations for each syntactic constituent, thereby embedding a deeper level of syntactic analysis within the model’s architecture.

Moreover, our research extends beyond sentence-level modeling to include document-level language understanding. This expansion is critical, as it allows us to explore the impact of syntactic structures in a broader linguistic context, encompassing longer and more complex textual formats.

In summary, our introduction of SET aims to bridge the gap between traditional Transformer models and the need for deeper syntactic understanding in NLP. By integrating syntactic structures into the Transformer framework, we hope to pave the way for a new generation of language models that combine the best of both worlds: the scalability and performance of Transformers with the nuanced understanding of language provided by syntactic analysis. This paper will detail the design of SET, their implementation, and the results of extensive evaluations that showcase their effectiveness in various language modeling tasks.

2. Related Work

The integration of syntactic and hierarchical elements into language models has been a subject of considerable interest in recent years. Models like the Recurrent Neural Network Grammar (RNNG) [

10,

12] have pioneered this approach by concurrently modeling linguistic trees and strings, employing recursive networks for phrase representation—a concept that echoes the methodology of our Syntax-Enhanced Transformers (SET). However, the scalability of RNNGs remains a challenge, as highlighted in [

15]. Other methods to incorporate structural biases without directly using observed syntax trees include employing stack-structured memory [

16], multi-scale RNNs [

17], and hierarchically organized LSTM ’forget’ gates [

18].

The emergence of Transformer models and large-scale pretraining has reignited the debate on the necessity of syntactic and hierarchical structures in language models. While it’s acknowledged that bidirectional encoders can implicitly learn syntactic details through pretraining [

23], they still struggle with rare syntactic phenomena, which may contribute to semantic inaccuracies [

24]. Various strategies have been proposed to infuse syntactic inductive biases into Transformer architectures, with mixed results in language understanding tasks [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Our proposed SET model synergizes two key strands of linguistic modeling: (i) the tradition of syntactic language models that calculate the joint likelihood of strings and their corresponding trees [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], and (ii) the practice of modulating attention patterns in Transformers based on syntactic structures [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. SET draw inspiration from, but differ significantly from, the model proposed by Qian et al. [

11], who combined syntax-sensitive language modeling with syntax-driven attention constraints. SET distinguish themselves in two primary aspects: firstly, they employ a unique typed-attention mask that incorporates duplicated closing nonterminal symbols to facilitate recursive syntactic compositions, a crucial element in RNN-based syntax models [

10,

39,

50,

51,

52]. Secondly, SET extend the concept of sentence-level syntactic modeling to encompass full-document models, a critical consideration in the wake of recent advancements in language modeling [

2,

4]. This expansion is pivotal for understanding the interplay between syntax and large-scale language modeling challenges.

3. Methodology

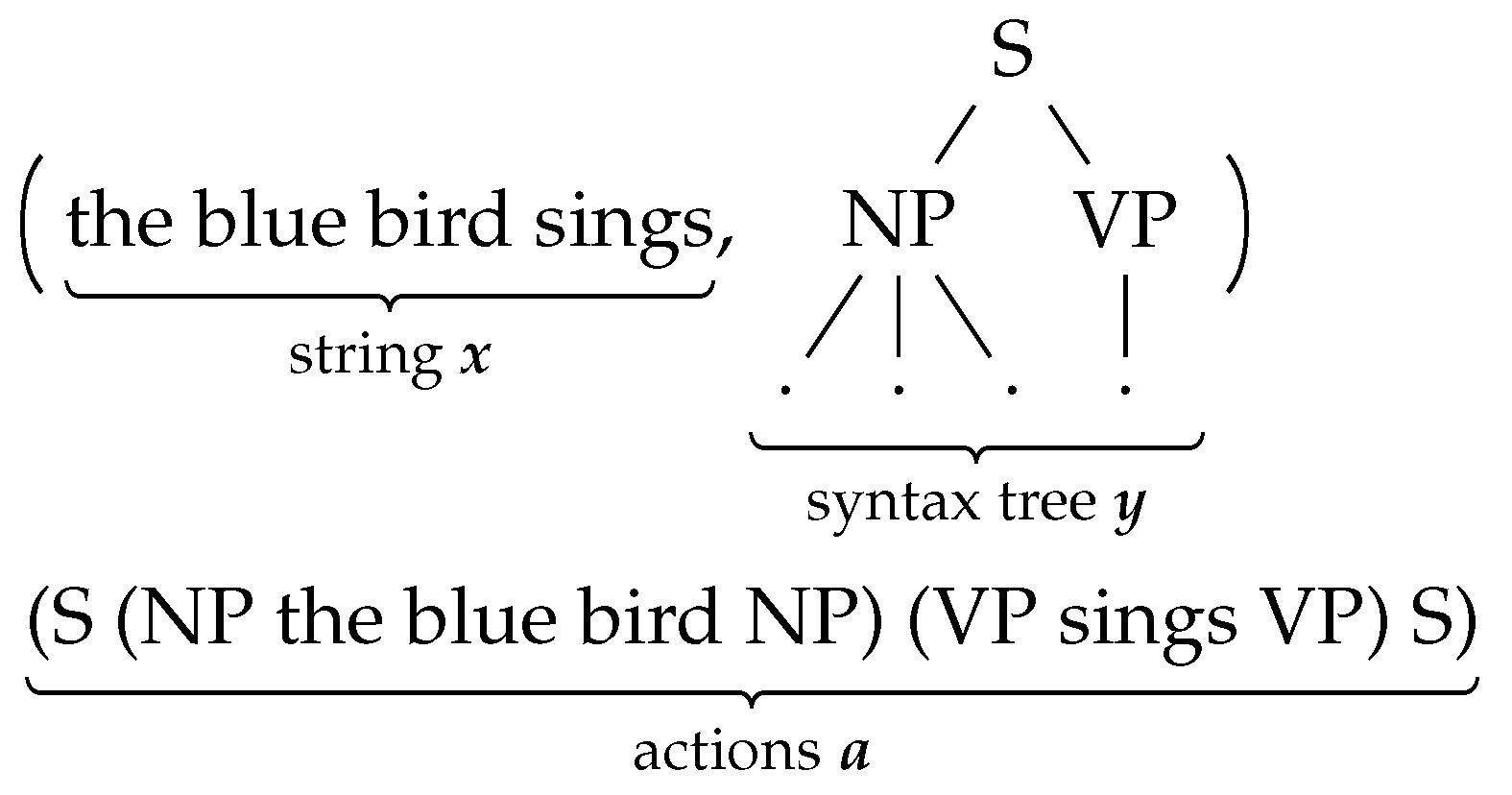

The Syntax-Enhanced Transformer (SET) models are at the forefront of syntactic language modeling. They are designed to simultaneously model the probabilities of syntactic phrase-structure trees

and the corresponding word strings

. SET use these predicted structures to guide the computation of model states, a concept rooted in recent advancements in syntactic parsing and language modeling [

10,

38,

53]. The generation of (

,

) is decomposed into a series of

actions that build the pair in a systematic top-down and left-to-right manner. This process involves interleaving nonterminal nodes with their children, as exemplified in

Figure 1. The linearized representation of (

,

) is categorized into three action types: (i) opening nonterminals (

ONT), which signify the start of a new constituent; (ii) generation of terminal symbols or leaf nodes (i.e., words or subword tokens), denoted as

T; and (iii) closure of the most recent open constituent or incomplete nonterminal symbol, denoted as

CNT.

Consider as the sequence of actions (length T) generating (, ), with each action belonging to the vocabulary . The SET defines a probability distribution over through a left-to-right factorization: .

3.1. Recursive syntactic composition via attention

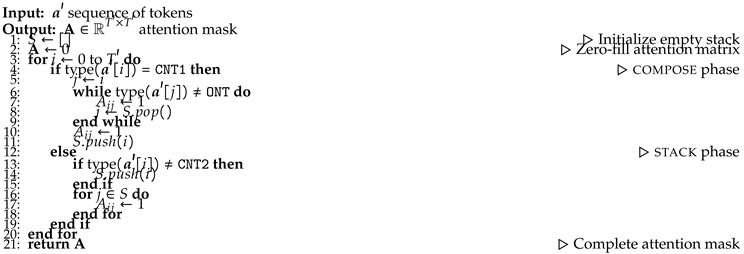

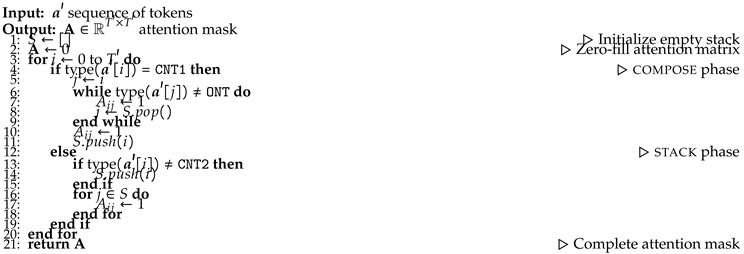

In SET models, attention is the key mechanism for integrating information from earlier positions when generating based on . The flow of this information, governed by the attention mask, is critical. SET are engineered to leverage recursive syntactic compositions, proven to enhance generalization in LSTM-based RNNG models, and implemented via the Transformer attention mechanism.

The action sequence in SET unfolds from left-to-right, with each symbol effectively updating a stack of indices. When is a closing nonterminal (signifying the end of a constituent), its index i gets represented by a single-vector composed representation, attained by attending to the child positions of the ending constituent. Future positions () may attend to this composed position but are restricted from directly attending to the individual constituent positions. This imposed syntactic bottleneck forces the model to learn informative representations of composed phrases, mirroring the design principle in RNNGs and other tree-structured architectures. The stack manipulation involves popping the indices of child nodes and pushing the index of the composed constituent, a process we term compose attention.

Additionally, we employ stack attention at each position i, where i is added to the stack and attention is limited to stack positions. Both stack and compose attention utilize identical parameters and heads, differentiated only by the rules defining attendable positions. Crucially, for closing nonterminals (e.g., to compute a composed representation and then add it to the stack), both compose and stack attentions are required. To manage this while maintaining one attention operation per token, we duplicate all closing nonterminals in the original sequence , resulting in a sequence of length , such as (S (NP the blue bird NP) NP) (VP sings VP) VP) S) S). The first closing nonterminal in each pair is labeled CNT1 for compose, and the second as CNT2 for stack. No final prediction is made for compose positions to keep the number of prediction events constant.

The procedure for stack/compose is detailed in Algorithm 1. The attendable positions are represented as a binary attention mask , where iff position j is attendable from i. The computation of is causal, meaning no information from positions is used in its computation.

3.1.0.1. Relative positional encoding.

In Transformer-XL, positional information is based on the difference between attending position

i and attended position

j,

i.e.,. SET generalize this concept to incorporate tree topology in relative positions. Any matrix

can represent relative positions, with

indicating the relative position between

i and

j. For SET,

, where

denotes the depth of the

i-th token in the tree. Note, the relative distance

is only computed if

(

i.e., if

j is attendable from

i). For example, in the action sequence, the relative distance between

sings and

bird is never calculated, but it is computed between

sings and its sibling NP covering

the blue bird.

|

Algorithm 1 stack/compose attention in SET Models |

|

3.2. Segmentation and Recurrence in SET

The SET inherits the recurrent neural network characteristics of Transformer-XL, enabling the processing of long sequences as consecutive segments containing a fixed number of tokens

L. This ability to maintain and update a memory of temporal dimension

M from one segment to the next is a critical aspect of SET’s design

1. For each segment

within the range

,

represents the

-th segment. These token embeddings are derived from an embedding matrix

, forming a sequence of

L vectors in

:

.

SET’s architecture comprises

K stacked recurrent layers. For each layer

k (with

), the following computation occurs:

Here, for each segment :

represents the sequence of hidden states, inputted into the next layer,

is the memory state,

denotes the attention mask linking the current segment with its memory,

is the matrix of relative positions.

Each layer receives identical attention masks and relative position matrices. The structure of each layer

k includes a multi-head self-attention (

) sub-layer and a position-wise feed-forward network (

) sub-layer, featuring residual connections and layer normalization (details omitted for brevity). Additionally, each layer updates the memory for subsequent segments:

The output from the final layer,

, is used to calculate the unnormalized log probabilities of the next token by multiplying with the transpose of the embedding matrix

.

Adhering to the notation of Dai et al. [

54], let

,

,

,

, and

u and

v represent the trainable parameters of the SET model. The operation `

’ signifies the concatenation along the time dimension. For each attention head, the computations are as follows:

The attention score between positions

i (attending) and

j (attended) is computed as:

where

represents the embedding of the relative position

(a row from

). As with Transformer-XL, the second term is efficiently computed since the relative positions fall within a limited range

.

The attention mask (described in §3.1) is applied to the scores element-wise, setting masked entries to . The normalized attention weights are derived by applying a function to these scores; the final attention output is the product of these weights and the values. SET utilize multiple heads, with the outputs from each head concatenated and then linearly transformed.

Unlike conventional Transformer-XLs where memory is updated by shifting the current input into it, SET leverage the fact that positions within a subtree that have undergone compose are never attended to in future segments. Consequently, only positions that might be attended are either added to or retained in the memory. This process necessitates meticulous tracking of each memory position’s correspondence with the original input sequence, both for updating purposes and for accurate computation of the attention mask and relative positions.

3.3. Properties of SET

The SET model achieves recursive composition through a bespoke attention mask, adeptly mirroring the hierarchical phrase structures inherent in natural language. While the mask at a given position

is contingent upon the mask at

i, during training, the complete attention mask matrix can be precalculated. This allows for the independent computation of multiple syntactic compositions in parallel across the entire segment. For instance, the representations of NP and VP constituents in the exemplar sequence are processed concurrently, despite the disparate sequence positions of their respective closing nonterminals. Sequential layers in the SET model build upon the compositions of preceding layers. For example, at position 12, the second layer constructs a composed representation of the sentence constituent

S) utilizing the first layer’s representations of

NP) and

VP). This model necessitates at least

d layers for tokens at depth

d to influence the uppermost composed representation, a characteristic shared with standard Transformers applied to tree structures [

55].

The SET model employs a compose attention mask for each closing nonterminal of type CNT1, while other actions utilize a stack attention mask. This stack mask renders accessible the representations of all completed constituents, words, and open nonterminals in the stack. In the scenario presented, the word sings is able to attend to the closed constituent NP), along with ancestral nonterminals (S and (VP. Significantly, at sings, knowledge of preceding words is only obtainable through the composed NP) representation, thereby reinforcing the syntactic composition’s compressive nature.

Higher layers in SET exhibit a nuanced interplay between stack and compose attentions. The stack attention, utilized for the representation of sings, can access the composed representation of the preceding NP) subject. This integration of "outside information" deviates from the stringent bottom-up compositionality found in RNNGs and akin models. The SET model’s indirect incorporation of external context into composed representations instills a bias against embedding such outside information within these representations. This bias stems from two premises: (i) the composition of a constituent at position i is influenced by predictions or prediction errors of a subsequent symbol (where ), and (ii) if ’s prediction heavily relies on information external to the constituent at i, a more direct attention path than through the composed representation at will always exist. The availability of two pathways, one direct (via attention) and one indirect (through composition followed by attention), advocates for a preference towards bottom-up information in composed representations.

It is important to note that the dynamics of how external context influences composition remain a complex and unresolved question. Research by Bowman et al. [

56] suggests that allowing external information to modulate compositional processes results in more effective composed representations. They argue that external context can play a vital role in disambiguating during the composition process. SET’s design accommodates these findings by allowing some degree of external context to shape the composition, while still prioritizing bottom-up information flow.

4. Experiments

In our experimental setup, we benchmark the Syntax-Enhanced Transformer (SET) against two Transformer-XL (TXL) variants: (i) TXL trained solely on terminal sequences (

TXL (terminals)), and (ii) TXL trained on linearized tree sequences as per the approach of Choe and Charniak [

38], hereinafter referred to as

TXL (trees). It’s noteworthy that the former model is a word-level language model estimating the probability of surface strings

, whereas the latter is a syntactic language model estimating

. Additionally, we compare SET with two preceding syntactic language models: (i) the generative parsing as language modeling approach by Qian et al. [

11], and (ii) the batched Recurrent Neural Network Grammar (RNNG) model of Noji and Oseki [

15].

Our experiments are conducted on the Penn Treebank (PTB) dataset [

57] containing approximately 1M words, and the BLLIP-

lg dataset [

58] as partitioned by Hu et al. [

59], comprising roughly 40M words. We utilize the sentence-level PTB dataset processed by Dyer et al. [

10], where unknown words and singletons in the training set are mapped according to a unique set of unknown word symbols following Petrov and Klein [

60]. For BLLIP-

lg, we employ the parse trees provided by Hu et al. [

59] and apply tokenization using SentencePiece [

61] with a 32K word-piece vocabulary.

We account for training variability by independently initializing and training 100 models for each type (SET, TXL (terminals), and TXL (trees)). On PTB, we deploy 16-layer models with 12M parameters, and for BLLIP-lg, we scale up to 16-layer models with 252M parameters. The best model checkpoint for each training run is selected based on the lowest validation loss, calculated using a single gold-standard tree per sentence.

4.1. Language Modeling Perplexity

Experimental Setup

To calculate the probability of a string for models focused on strings, we use a left-to-right decomposition. For models operating on the joint distribution of strings and syntax trees, we define as the marginal distribution, summing over the set of possible trees . Given the infinite nature of , we approximate this probability using a smaller set of proposal trees . We use a separately-trained discriminative RNNG as a proposal model , and select a set of trees sampled without replacement to approximate the most likely trees for .

The word perplexity of the validation and test splits of the dataSET under the models is computed as , where is the total number of words in dataset D. This measure is exact for models operating on words and an upper bound for models working on the joint distribution of strings and syntax trees.

Discussion

Table 1 presents the mean and sample standard deviation of perplexity for the models. Interestingly, both TXL (trees) and SET models demonstrate lower perplexity than the TXL (terminals) model on both PTB and BLLIP sentence-level dataSET, indicating the effectiveness of joint modeling of syntax and strings in Transformers. However, when comparing SET to TXL (trees), there is a slight increase in perplexity on both dataSET and a more pronounced increase at the document level on BLLIP-

lg. This suggests that while explicit syntactic modeling aids language understanding, its implementation may require further optimization for better performance in complex, document-level language modeling scenarios.

4.2. Syntactic Generalization

Experimental Setup

Building on the framework established by Hu et al. [

59], we explore the syntactic generalization capabilities of language models. This framework assesses models’ proficiency in human-like syntactic generalization, a pivotal aspect of linguistic competence. The evaluation is based on how well models adhere to certain probabilistic constraints in crafted examples that reflect human language processing patterns. We deploy models trained on individual sentences from BLLIP-

lg for this evaluation, using parse trees from Hu et al. [

59] generated via an RNNG proposal model. The results are reported as the average syntactic generalization (

SG) score, encompassing 31 distinct syntactic test suites.

Discussion

Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviation of the average SG scores. Our analysis reveals that models trained on linearized tree structures, specifically SET and TXL (trees), exhibit superior SG scores compared to those trained solely on word sequences (TXL (terminals)). This pattern is also evident when compared to larger-scale models, such as GPT-2, Gopher [

62], and Chinchilla [

63], suggesting that mere scale and data volume are not substitutes for structural understanding.

This finding is attributable to a threefold mechanism: Firstly, the inclusion of nonterminals in SET and TXL (trees) during training acts as a form of syntactic guidance, aiding in the selection of suitable parses. Secondly, the SG score computation, which relies on model surprisals on words, involves an approximate marginalization step for SET and TXL (trees). This step weights valid parses more heavily. Lastly, a model’s inclination towards syntactically coherent parses simplifies its performance on the test suite tasks, hence the improved scores. The larger models’ results indicate that increasing model size does not necessarily compensate for the lack of structured syntactic training.

A key observation is that SET, when compared to TXL (trees), shows marked advantages in tasks closely linked to structural modeling, such as parse reranking and the broad SG test suite. SET achieves higher bracketing scores and average SG scores, with statistically significant differences. This enhancement in SET’s performance is likely due to its constrained attention mechanism, which limits attention to syntactically relevant segments of the input. Such a design promotes the development of informative representations of subtrees, aligning the model more closely with the intricacies of syntactic structures.

5. Conclusions

The Syntax-Enhanced Transformer (SET) represents a novel paradigm in syntactic language modeling, adeptly integrating recursive syntactic composition within phrase representations via an advanced attention mechanism. Our comprehensive experiments demonstrate that SET surpass previous models in terms of performance on several syntax-sensitive language modeling benchmarks. Specifically, in sentence-level language modeling, SET exhibit superior performance over a robust Transformer-XL model that processes only word sequences. However, it is observed that at the document level, SET, constrained to single composed representations for preceding sentences, show reduced effectiveness. This finding underscores the complexity of document-level language modeling and the challenge of adequately representing long sequences with syntactic structures. Moreover, our analysis reveals that incorporating structural information into Transformer models consistently enhances performance across all evaluated metrics compared to models trained exclusively on word sequences. This reinforces the pivotal role of syntactic understanding in language modeling. While SET maintain the sampling efficiency characteristic of autoregressive language models, they present challenges in probability estimation. Direct probability calculations are less straightforward with SET, necessitating either increased computational effort or further research to develop efficient probability estimation methodologies. Our study highlights the ongoing imperative to devise more scalable and effective methods to instill structural properties of language into language models. This endeavor is crucial for achieving deeper linguistic understanding and more human-like language processing capabilities in AI systems. The implementation of SET is available upon request, inviting further exploration and development in this promising area of NLP research.

5.1. Future Work

Looking ahead, several avenues for future research emerge from our work on the Syntax-Enhanced Transformer (SET). First and foremost, exploring the extension of SET to document-level language modeling presents a significant opportunity. While SET demonstrate efficacy at the sentence level, their performance at handling longer texts, such as entire documents, needs further investigation. Developing methods to effectively represent longer sequences without losing the syntactic detail and coherence is a promising direction.

Another key area for future exploration involves enhancing the efficiency of probability estimation in SET. Given the complexity of calculating probabilities in models that incorporate structural information, novel techniques or algorithms that streamline this process would be highly beneficial. This could involve the development of new sampling strategies or the integration of approximation methods to balance accuracy and computational efficiency.

Additionally, the integration of unsupervised or semi-supervised learning approaches to further improve the syntactic understanding of SET is an intriguing possibility. Leveraging large, unannotated corpora to refine and expand the model’s syntactic capabilities could lead to improvements in language understanding and generation tasks.

Finally, examining the applicability of SET in diverse NLP tasks, such as machine translation, summarization, and question-answering, is an important area of research. Understanding how the syntactic nuances captured by SET can enhance performance on these tasks will be crucial in determining the broader impact and utility of the model.

In conclusion, the potential applications and improvements of the Syntax-Enhanced Transformer are vast, and we look forward to the advancements that future research will bring in this domain.

| 1 |

This property, a key advantage of Transformer-XL, forms the basis for our selection of it as the foundational architecture for SET. |

References

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Proc. of NAACL, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners 2019.

- Wu, S.; Fei, H.; Qu, L.; Ji, W.; Chua, T.S. NExT-GPT: Any-to-Any Multimodal LLM. CoRR 2023, abs/2309.05519.

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Agarwal, S.; Herbert-Voss, A.; Krueger, G.; Henighan, T.; Child, R.; Ramesh, A.; Ziegler, D.; Wu, J.; Winter, C.; Hesse, C.; Chen, M.; Sigler, E.; Litwin, M.; Gray, S.; Chess, B.; Clark, J.; Berner, C.; McCandlish, S.; Radford, A.; Sutskever, I.; Amodei, D. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H.; Ranzato, M.; Hadsell, R.; Balcan, M.F.; Lin, H., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020, Vol. 33, pp. 1877–1901.

- Fei, H.; Ren, Y.; Ji, D. Retrofitting Structure-aware Transformer Language Model for End Tasks. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2020, pp. 2151–2161.

- Peters, M.E.; Neumann, M.; Iyyer, M.; Gardner, M.; Clark, C.; Lee, K.; Zettlemoyer, L. Deep Contextualized Word Representations. Proc. of NAACL, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, N. Syntactic Structures; Mouton: The Hague/Paris, 1957.

- Li, J.; Xu, K.; Li, F.; Fei, H.; Ren, Y.; Ji, D. MRN: A Locally and Globally Mention-Based Reasoning Network for Document-Level Relation Extraction. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, 2021, pp. 1359–1370.

- Fei, H.; Wu, S.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, M. Matching Structure for Dual Learning. Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, 2022, pp. 6373–6391.

- Dyer, C.; Kuncoro, A.; Ballesteros, M.; Smith, N.A. Recurrent Neural Network Grammars. Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; Association for Computational Linguistics: San Diego, California, 2016; pp. 199–209. [CrossRef]

- Qian, P.; Naseem, T.; Levy, R.; Fernandez Astudillo, R. Structural Guidance for Transformer Language Models. Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Online, 2021; pp. 3735–3745. [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, A.; Ballesteros, M.; Kong, L.; Dyer, C.; Neubig, G.; Smith, N.A. What Do Recurrent Neural Network Grammars Learn About Syntax? Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Volume 1, Long Papers; Association for Computational Linguistics: Valencia, Spain, 2017; pp. 1249–1258.

- Fei, H.; Ren, Y.; Ji, D. Boundaries and edges rethinking: An end-to-end neural model for overlapping entity relation extraction. Information Processing & Management 2020, 57, 102311. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Fei, H.; Liu, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, M.; Teng, C.; Ji, D.; Li, F. Unified Named Entity Recognition as Word-Word Relation Classification. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, pp. 10965–10973.

- Noji, H.; Oseki, Y. Effective Batching for Recurrent Neural Network Grammars. Findings of the ACL-IJCNLP, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yogatama, D.; Miao, Y.; Melis, G.; Ling, W.; Kuncoro, A.; Dyer, C.; Blunsom, P. Memory Architectures in Recurrent Neural Network Language Models. Proc. of ICLR, 2018.

- Chung, J.; Ahn, S.; Bengio, Y. Hierarchical Multiscale Recurrent Neural Networks. Proc. of ICLR, 2017.

- Shen, Y.; Tan, S.; Sordoni, A.; Courville, A. Ordered Neurons: Integrating Tree Structures into Recurrent Neural Networks. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2019.

- Wu, S.; Fei, H.; Li, F.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Teng, C.; Ji, D. Mastering the Explicit Opinion-Role Interaction: Syntax-Aided Neural Transition System for Unified Opinion Role Labeling. Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, pp. 11513–11521.

- Shi, W.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Fei, H.; Ji, D. Effective Token Graph Modeling using a Novel Labeling Strategy for Structured Sentiment Analysis. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2022, pp. 4232–4241.

- Fei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Ji, D. Latent Emotion Memory for Multi-Label Emotion Classification. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020, pp. 7692–7699.

- Wang, F.; Li, F.; Fei, H.; Li, J.; Wu, S.; Su, F.; Shi, W.; Ji, D.; Cai, B. Entity-centered Cross-document Relation Extraction. Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022, pp. 9871–9881.

- Manning, C.D.; Clark, K.; Hewitt, J.; Khandelwal, U.; Levy, O. Emergent linguistic structure in artificial neural networks trained by self-supervision. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117. [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, A. What BERT Is Not: Lessons from a New Suite of Psycholinguistic Diagnostics for Language Models. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Bi, B.; Yan, M.; Wu, C.; Bao, Z.; Peng, L.; Si, L. StructBERT: Incorporating Language Structures into Pre-training for Deep Language Understanding. Proc. of ICLR, 2020.

- Fei, H.; Wu, S.; Ren, Y.; Li, F.; Ji, D. Better Combine Them Together! Integrating Syntactic Constituency and Dependency Representations for Semantic Role Labeling. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL/IJCNLP 2021, 2021, pp. 549–559.

- Sundararaman, D.; Subramanian, V.; Wang, G.; Si, S.; Shen, D.; Wang, D.; Carin, L. Syntax-Infused Transformer and BERT models for Machine Translation and Natural Language Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.06156v1 2019. arXiv:1911.06156v1 2019.

- Kuncoro, A.; Kong, L.; Fried, D.; Yogatama, D.; Rimell, L.; Dyer, C.; Blunsom, P. Syntactic Structure Distillation Pretraining for Bidirectional Encoders. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2020, 8, 776–794, [https://direct.mit.edu/tacl/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/tacl_a_00345/1923888/tacl_a_00345.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Sachan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, P.; Hamilton, W.L. Do Syntax Trees Help Pre-trained Transformers Extract Information? Proc. of EACL, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Bai, J.; Yu, J.; Tong, Y. Syntax-BERT: Improving Pre-trained Transformers with Syntax Trees. Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume; Association for Computational Linguistics: Online, 2021; pp. 3011–3020.

- Warstadt, A.; Parrish, A.; Liu, H.; Mohananey, A.; Peng, W.; Wang, S.F.; Bowman, S.R. BLiMP: The Benchmark of Linguistic Minimal Pairs for English. TACL 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pruksachatkun, Y.; Phang, J.; Liu, H.; Htut, P.M.; Zhang, X.; Pang, R.Y.; Vania, C.; Kann, K.; Bowman, S.R. Intermediate-Task Transfer Learning with Pretrained Language Models: When and Why Does It Work? Proc. of ACL, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jurafsky, D.; Wooters, C.; Segal, J.; Stolcke, A.; Fosler, E.; Tajchman, G.N.; Morgan, N. Using a stochastic context-free grammar as a language model for speech recognition. Proc. of ICASSP, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Chelba, C.; Jelinek, F. Structured Language Modeling. Computer Speech & Language 2000, 14, 283–332. [CrossRef]

- Roark, B. Probabilistic Top-Down Parsing and Language Modeling. Computational Linguistics 2001, 27, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J. Discriminative Training of a Neural Network Statistical Parser. Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL-04); , 2004; pp. 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Mirowski, P.; Vlachos, A. Dependency Recurrent Neural Language Models for Sentence Completion. Proc. of ACL-IJCNLP, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Choe, D.K.; Charniak, E. Parsing as Language Modeling. Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Association for Computational Linguistics: Austin, Texas, 2016; pp. 2331–2336. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Rush, A.; Yu, L.; Kuncoro, A.; Dyer, C.; Melis, G. Unsupervised Recurrent Neural Network Grammars. Proc. of NAACL, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.; Wu, S.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Li, F.; Qin, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Chua, T.S. LasUIE: Unifying Information Extraction with Latent Adaptive Structure-aware Generative Language Model. Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2022, 2022, pp. 15460–15475.

- Fei, H.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, D.; Liang, X. Enriching contextualized language model from knowledge graph for biomedical information extraction. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22.

- Strubell, E.; Verga, P.; Andor, D.; Weiss, D.; McCallum, A. Linguistically-Informed Self-Attention for Semantic Role Labeling. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Association for Computational Linguistics: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 5027–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Chen, Y.N. Tree Transformer: Integrating Tree Structures into Self-Attention. Proc. of EMNLP-IJCNLP, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Schwartz, R.; Smith, N.A. PaLM: A Hybrid Parser and Language Model. Proc. of EMNLP-IJCNLP, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Chua, T.S. Scene Graph as Pivoting: Inference-time Image-free Unsupervised Multimodal Machine Translation with Visual Scene Hallucination. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2023, pp. 5980–5994.

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Duan, S.; Zhao, H.; Wang, R. SG-Net: Syntax-Guided Machine Reading Comprehension. The Thirty-Fourth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI 2020, The Thirty-Second Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference, IAAI 2020, The Tenth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, EAAI 2020, New York, NY, USA, February 7-12, 2020. AAAI Press, 2020, pp. 9636–9643.

- Nguyen, X.; Joty, S.R.; Hoi, S.C.H.; Socher, R. Tree-Structured Attention with Hierarchical Accumulation. 8th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2020, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, April 26-30, 2020. OpenReview.net, 2020.

- Astudillo, R.F.; Ballesteros, M.; Naseem, T.; Blodgett, A.; Florian, R. Transition-based Parsing with Stack-Transformers. Findings of EMNLP, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.; Zhang, M.; Ji, D. Cross-Lingual Semantic Role Labeling with High-Quality Translated Training Corpus. Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020, pp. 7014–7026.

- Wu, S.; Fei, H.; Ren, Y.; Ji, D.; Li, J. Learn from Syntax: Improving Pair-wise Aspect and Opinion Terms Extraction with Rich Syntactic Knowledge. Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021, pp. 3957–3963.

- Wilcox, E.; Qian, P.; Futrell, R.; Ballesteros, M.; Levy, R. Structural Supervision Improves Learning of Non-Local Grammatical Dependencies. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019; pp. 3302–3312. [CrossRef]

- Futrell, R.; Wilcox, E.; Morita, T.; Qian, P.; Ballesteros, M.; Levy, R. Neural language models as psycholinguistic subjects: Representations of syntactic state. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019; pp. 32–42. [CrossRef]

- Vinyals, O.; Kaiser, L.; Koo, T.; Petrov, S.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G. Grammar as a Foreign Language. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Cortes, C.; Lawrence, N.; Lee, D.; Sugiyama, M.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2015, Vol. 28.

- Dai, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.; Le, Q.; Salakhutdinov, R. Transformer-XL: Attentive Language Models beyond a Fixed-Length Context. Proc. of ACL, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M. Theoretical Limitations of Self-Attention in Neural Sequence Models. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2020, 8, 156–171, [https://direct.mit.edu/tacl/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/tacl_a_00306/1923102/tacl_a_00306.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.R.; Gauthier, J.; Rastogi, A.; Gupta, R.; Manning, C.D.; Potts, C. A Fast Unified Model for Parsing and Sentence Understanding. Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 1466–1477. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M.P.; Santorini, B.; Marcinkiewicz, M.A. Building a Large Annotated Corpus of English: The Penn Treebank. Computational Linguistics 1993, 19, 313–330.

- Charniak, E.; Blaheta, D.; Ge, N.; Hall, K.; Hale, J.; Johnson, M. BLLIP 1987–89 WSJ Corpus Release 1, LDC2000T43. LDC2000T43. Linguistic Data Consortium 2000, 36.

- Hu, J.; Gauthier, J.; Qian, P.; Wilcox, E.; Levy, R. A Systematic Assessment of Syntactic Generalization in Neural Language Models. Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Association for Computational Linguistics: Online, 2020; pp. 1725–1744. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, S.; Klein, D. Improved Inference for Unlexicalized Parsing. Human Language Technologies 2007: The Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Proceedings of the Main Conference; Association for Computational Linguistics: Rochester, New York, 2007; pp. 404–411.

- Kudo, T.; Richardson, J. SentencePiece: A simple and language independent subword tokenizer and detokenizer for Neural Text Processing. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations; Association for Computational Linguistics: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 66–71. [CrossRef]

- Rae, J.W.; Borgeaud, S.; Cai, T.; Millican, K.; Hoffmann, J.; Song, H.F.; Aslanides, J.; Henderson, S.; Ring, R.; Young, S.; Rutherford, E.; Hennigan, T.; Menick, J.; Cassirer, A.; Powell, R.; van den Driessche, G.; Hendricks, L.A.; Rauh, M.; Huang, P.; Glaese, A.; Welbl, J.; Dathathri, S.; Huang, S.; Uesato, J.; Mellor, J.; Higgins, I.; Creswell, A.; McAleese, N.; Wu, A.; Elsen, E.; Jayakumar, S.M.; Buchatskaya, E.; Budden, D.; Sutherland, E.; Simonyan, K.; Paganini, M.; Sifre, L.; Martens, L.; Li, X.L.; Kuncoro, A.; Nematzadeh, A.; Gribovskaya, E.; Donato, D.; Lazaridou, A.; Mensch, A.; Lespiau, J.; Tsimpoukelli, M.; Grigorev, N.; Fritz, D.; Sottiaux, T.; Pajarskas, M.; Pohlen, T.; Gong, Z.; Toyama, D.; de Masson d’Autume, C.; Li, Y.; Terzi, T.; Mikulik, V.; Babuschkin, I.; Clark, A.; de Las Casas, D.; Guy, A.; Jones, C.; Bradbury, J.; Johnson, M.; Hechtman, B.A.; Weidinger, L.; Gabriel, I.; Isaac, W.S.; Lockhart, E.; Osindero, S.; Rimell, L.; Dyer, C.; Vinyals, O.; Ayoub, K.; Stanway, J.; Bennett, L.; Hassabis, D.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Irving, G. Scaling Language Models: Methods, Analysis & Insights from Training Gopher. CoRR 2021, abs/2112.11446v2.

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Casas, D.d.L.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; Hennigan, T.; Noland, E.; Millican, K.; Driessche, G.v.d.; Damoc, B.; Guy, A.; Osindero, S.; Simonyan, K.; Elsen, E.; Rae, J.W.; Vinyals, O.; Sifre, L. Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. CoRR 2022, abs/2203.15556v1. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).