Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

Discussion

Materials and Methods

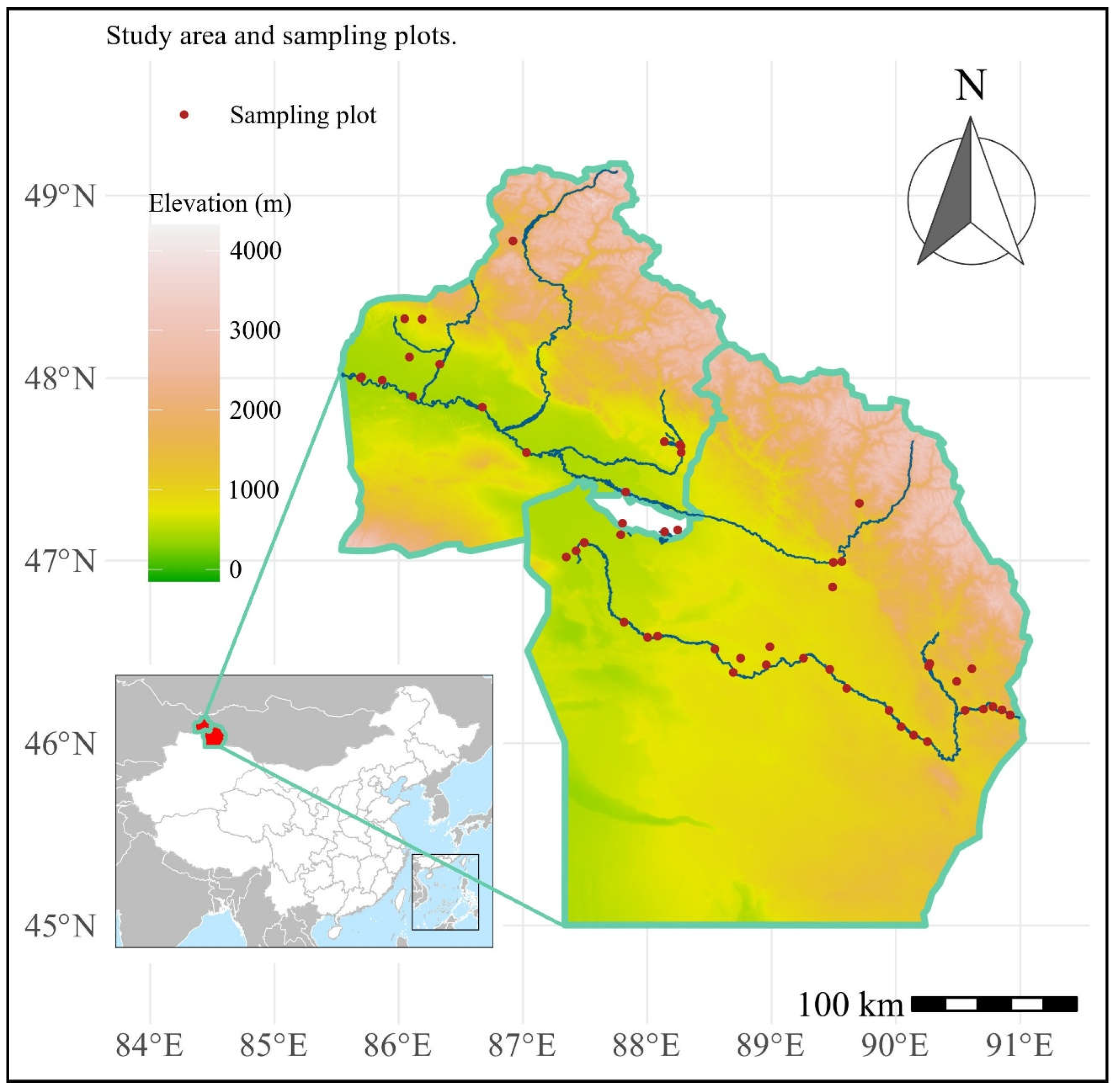

Study Area

Field Survey

Species Name Standardization

Environmental Factors

Species Diversity Metrics

Data Analysis

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiu, S.Y.; Liu, S.S.; Wei, S.J.; Cui, X.H.; Nie, M.; Huang, J.X.; He, Q.; Ju, R.T.; Li, B. Changes in Multiple Environmental Factors Additively Enhance the Dominance of an Exotic Plant with a Novel Trade-off Pattern. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 1989–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.Q.; Cui, M.M.; Yu, H.C.; Fan, X.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Zhang, H.Y.; Dai, Z.C.; Sun, J.F.; Yang, B.; Du, D.L. Global Environmental Change Shifts Ecological Stoichiometry Coupling between Plant and Soil in Early-Stage Invasions. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 2402–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, M.O.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, F.H. Genotypic Differences in Response to Different Patterns of Clonal Fragmentation in the Aquatic Macrophyte Pistia stratiotes. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catford, J.A.; Bode, M.; Tilman, D. Introduced Species That Overcome Life History Tradeoffs Can Cause Native Extinctions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Chen, J.; Xu, C.; Koppel, J. van de; Thomsen, M.S.; Qiu, S.; Cheng, F.; Song, W.; Liu, Q.-X.; Xu, C.; et al. An Invasive Species Erodes the Performance of Coastal Wetland Protected Areas. Sci. Adv. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.M. Interacting Effects of Plant Invasion, Climate, and Soils on Soil Organic Carbon Storage in Coastal Wetlands. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2019, 124, 2554–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Invasive Plants in Coastal Wetlands: Patterns and Mechanisms. In Wetlands: Ecosystem Services, Restoration and Wise Use; An, S., Verhoeven, J.T.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 97–128. ISBN 978-3-030-14861-4. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.B.; Bian, Z.H.; Ren, W.J.; Wu, J.H.; Liu, J.Q.; Shrestha, N. Spatial Patterns and Hotspots of Plant Invasion in China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 43, e02424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.C.; Dong, R.; Yang, Q.; Kinlock, N.L.; Yu, F.H.; van Kleunen, M. Predicting Invasion Success of Naturalized Cultivated Plants in China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 62, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.H.; Chen, X.M.; Liu, R.L.; Zhang, S.H.; Gao, J.Q.; Dong, B.C.; Yu, F.H. Effects of Alligator Weed Invasion on Wetlands in Protected Areas: A Case Study of Lishui Jiulong National Wetland Park. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 953, 176230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.G.; Ding, H.; Li, M.; Qiang, S.; Guo, J.Y.; Han, Z.M.; Huang, Z.G.; Sun, H.Y.; He, S.P.; Wu, H.R.; et al. The Distribution and Economic Losses of Alien Species Invasion to China. Biol. Invasions 2006, 8, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early, R.; Bradley, B.A.; Dukes, J.S.; Lawler, J.J.; Olden, J.D.; Blumenthal, D.M.; Gonzalez, P.; Grosholz, E.D.; Ibañez, I.; Miller, L.P.; et al. Global Threats from Invasive Alien Species in the Twenty-First Century and National Response Capacities. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, J.L.; Vitousek, P.M. Resource-Use Efficiency and Plant Invasion in Low-Resource Systems. Nature 2007, 446, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, J.Z.; Liu, M.; Yan, Z.Q.; Xu, X.L.; Kuzyakov, Y. Invasive Plant Competitivity Is Mediated by Nitrogen Use Strategies and Rhizosphere Microbiome. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 192, 109361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.H.; Yang, H.J.; Ma, T.X.; Huang, C.Y.; Hu, L.Y.; Zhang, M.X.; Sang, W.G. Enhanced Competitive Advantage of Invasive Plants by Growth-Defence Trade-off: Evidence from Phytohormone Metabolism and Transcriptomic Analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.C.M.; Mesléard, F.; Buisson, E. Priority Effects: Emerging Principles for Invasive Plant Species Management. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 127, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; van Kleunen, M. Common Alien Plants Are More Competitive than Rare Natives but Not than Common Natives. Ecol. Lett. 2019, 22, 1378–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, M.O.; Ning, L.; Tang, M.; Du, D.L.; van Kleunen, M.; Yu, F.H. Diversity- and Density-Mediated Allelopathic Effects of Resident Plant Communities on Invasion by an Exotic Plant. Plant Soil 2019, 440, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Wang, J.Y. Functional Traits of Both Specific Alien Species and Receptive Community but Not Community Diversity Determined the Invasion Success under Biotic and Abiotic Conditions. Funct. Ecol. 2023, 37, 2598–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.J. Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Plant Invasion Success Driven by Nitrogen Fluctuations. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 60, 2425–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Yang, L.F. Impacts of invasion plant on soil ecological environment. Adv. Environ. Prot. 2020, 10, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, F.H. Effects of Invasive Plant Diversity on Soil Microbial Communities. Diversity 2022, 14, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauni, M.; Hyvönen, T. Positive Diversity–Invasibility Relationships across Multiple Scales in Finnish Agricultural Habitats. Biol. Invasions 2012, 14, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiter, M.; Stampfli, A. Positive Diversity–Invasibility Relationship in Species-Rich Semi-Natural Grassland at the Neighbourhood Scale. Ann. Bot. 2012, 110, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambers, J.H.R.; Harpole, W.S.; Tilman, D.; Knops, J.; Reich, P.B. Mechanisms Responsible for the Positive Diversity–Productivity Relationship in Minnesota Grasslands. Ecol. Lett. 2004, 7, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridley, J.D.; Stachowicz, J.J.; Naeem, S.; Sax, D.F.; Seabloom, E.W.; Smith, M.D.; Stohlgren, T.J.; Tilman, D.; Holle, B.V. The Invasion Paradox: Reconciling Pattern and Process in Species Invasions. Ecology 2007, 88, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.F.T.; Billings, S.A. Temperature and pH Mediate Stoichiometric Constraints of Organically Derived Soil Nutrients. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 1630–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, G.Q.; Du, Y.Z.; Yang, B.; Wang, J.J.; Cui, M.M.; Dai, Z.C.; Adomako, M.O.; Rutherford, S.; Du, D.L. Influence of Precipitation Dynamics on Plant Invasions: Response of Alligator Weed (Alternanthera philoxeroides) and Co-Occurring Native Species to Varying Water Availability across Plant Communities. Biol. Invasions 2023, 25, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Chahouki, M.A.Z.; Tavili, A.; Azarnivand, H.; Amiri, Gh.Z. Effective Environmental Factors in the Distribution of Vegetation Types in Poshtkouh Rangelands of Yazd Province (Iran). J. Arid Environ. 2004, 56, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.H.; Jensen, K.; Schönfeldt, M. Warming Increases Plant Biomass and Reduces Diversity across Continents, Latitudes, and Species Migration Scenarios in Experimental Wetland Communities. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.J.; Yang, S.W.; Zhou, J.W.; Chu, B.; Ma, S.J.; Zhu, H.M.; Hua, L.M. Vegetation Distribution along Mountain Environmental Gradient Predicts Shifts in Plant Community Response to Climate Change in Alpine Meadow on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.L.; Xia, J.Y.; Wan, S.Q. Climate Warming and Biomass Accumulation of Terrestrial Plants: A Meta-Analysis. New Phytol. 2010, 188, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seddon, A.W.R.; Macias-Fauria, M.; Long, P.R.; Benz, D.; Willis, K.J. Sensitivity of Global Terrestrial Ecosystems to Climate Variability. Nature 2016, 531, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-M.; Gao, Y.; Liao, H.X.; Peng, S.L. Differential Responses of Invasive and Native Plants to Warming with Simulated Changes in Diurnal Temperature Ranges. AoB Plants 2017, 9, plx028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseli, E.; Chisholm, C.; Lenoir, J.; Haider, S.; Seipel, T.; Barros, A.; Hargreaves, A.L.; Kardol, P.; Lembrechts, J.J.; McDougall, K.; et al. Rapid Upwards Spread of Non-Native Plants in Mountains across Continents. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.M.; Pyšek, P.; Guo, K.; Hasigerili, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Guo, W.Y. Clonal Alien Plants in the Mountains Spread Upward More Extensively and Faster than Non-Clonal. NeoBiota 2024, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Li, Z.-A.; Daleo, P.; Lefcheck, J.S.; Thomsen, M.S.; Adams, J.B.; Bouma, T.J. Coastal Wetland Resilience through Local, Regional and Global Conservation. Nat. Rev. Biodivers. 2025, 1, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundson, R. Soil Biogeochemistry and the Global Agricultural Footprint. Soil Secur. 2022, 6, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.H.; Qian, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.M.; Gao, H.; An, Y.N.; Qi, J.J.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.R.; Chen, S.; et al. Land Conversion to Agriculture Induces Taxonomic Homogenization of Soil Microbial Communities Globally. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembrechts, J.J.; Pauchard, A.; Lenoir, J.; Nuñez, M.A.; Geron, C.; Ven, A.; Bravo-Monasterio, P.; Teneb, E.; Nijs, I.; Milbau, A. Disturbance Is the Key to Plant Invasions in Cold Environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 14061–14066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, I.; Bellingham, P.J.; Mason, N.W.H.; McCarthy, J.K.; Peltzer, D.A.; Richardson, S.J.; Wright, E.F. Disturbance-Mediated Community Characteristics and Anthropogenic Pressure Intensify Understorey Plant Invasions in Natural Forests. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 1856–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, É.S.; Dias, F.S.; Borda-de-Água, L.; González, P.M.R. Anthropogenic Disturbance and Alien Plant Invasion Drive the Phylogenetic Impoverishment in Riparian Vegetation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2024, 33, 4237–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, K.; Guo, Y.Q. Study on ecological protection and restoration path of arid area based on improvement of ecosystem service capability, a case of the ecological protection and restoration pilot project aera in Irtysh River basin. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 8998–9007. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, B.C.; Yang, Q.; Kinlock, N.L.; Pouteau, R.; Pyšek, P.; Weigelt, P.; Yu, F.H.; van Kleunen, M. Naturalization of Introduced Plants Is Driven by Life-Form-Dependent Cultivation Biases. Divers. Distrib. 2024, 30, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, M.O.; Alpert, P.; Du, D.L.; Yu, F.H. Effects of Fragmentation of Clones Compound over Vegetative Generations in the Floating Plant Pistia stratiotes. Ann. Bot. 2021, 127, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adomako, M.O.; Alpert, P.; Du, D.L.; Yu, F.H. Effects of Clonal Integration, Nutrients and Cadmium on Growth of the Aquatic Macrophyte Pistia stratiotes. J. Plant Ecol. 2020, 13, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, T.; Hudson, L.N.; Hill, S.L.L.; Contu, S.; Lysenko, I.; Senior, R.A.; Börger, L.; Bennett, D.J.; Choimes, A.; Collen, B.; et al. Global Effects of Land Use on Local Terrestrial Biodiversity. Nature 2015, 520, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenda, M.; Skórka, P.; Knops, J.; Żmihorski, M.; Gaj, R.; Moroń, D.; Woyciechowski, M.; Tryjanowski, P. Multispecies Invasion Reduces the Negative Impact of Single Alien Plant Species on Native Flora. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turbelin, A.; Catford, J.A. Chapter 25 - Invasive Plants and Climate Change. In Climate Change (Third Edition); Letcher, T.M., Ed.; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 515–539. ISBN 978-0-12-821575-3. [Google Scholar]

- Garces, J.J.C.; Flores, M.J.L. Effects of Environmental Factors and Alien Plant Invasion on Native Floral Diversity in Mt. Manunggal, Cebu Island, Philippines. Curr. World Environ. 2018, 13, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.C.; Alpert, P.; Guo, W.; Yu, F.H. Effects of Fragmentation on the Survival and Growth of the Invasive, Clonal Plant Alternanthera philoxeroides. Biol. Invasions 2012, 14, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Liu, Z.-K.; Song, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.J.; Li, B.; van Kleunen, M.; Wu, J. Biodiversity Increases Resistance of Grasslands against Plant Invasions under Multiple Environmental Changes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunez-Mir, G.C.; McCary, M.A. Invasive Plants and Their Root Traits Are Linked to the Homogenization of Soil Microbial Communities across the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121, e2418632121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, D.M.; Pyšek, P. Naturalization of Introduced Plants: Ecological Drivers of Biogeographical Patterns. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuebbing, S.E.; Nuñez, M.A. Invasive Non-Native Plants Have a Greater Effect on Neighbouring Natives than Other Non-Natives. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavieres, L.A. Facilitation and the Invasibility of Plant Communities. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 2019–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pec, G.J.; Carlton, G.C. Positive Effects of Non-Native Grasses on the Growth of a Native Annual in a Southern California Ecosystem. PLoS One 2014, 9, e112437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Carrillo, J.; Ding, J.Q. Species Diversity and Environmental Determinants of Aquatic and Terrestrial Communities Invaded by Alternanthera philoxeroides. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 581–582, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Wu, B.D.; Jiang, K.; Zhou, J.W.; Du, D.L. Canada Goldenrod Invasion Affect Taxonomic and Functional Diversity of Plant Communities in Heterogeneous Landscapes in Urban Ecosystems in East China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.L.; Yang, Y.B.; Lee, B.R.; Liu, G.; Zhang, W.G.; Chen, X.Y.; Song, X.J.; Kang, J.Q.; Zhu, Z.H. The Dispersal-Related Traits of an Invasive Plant Galinsoga quadriradiata Correlate with Elevation during Range Expansion into Mountain Ranges. AoB Plants 2021, 13, plab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xiong, Q.L.; Luo, P.; Zhang, Y.B.; Gu, X.D.; Lin, B. Direct and Indirect Effects of Environmental Factors, Spatial Constraints, and Functional Traits on Shaping the Plant Diversity of Montane Forests. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Wang, T.-J.; Han, Q.; Dai, Y.B.; Zuo, Y.T.; Wang, L.C.; Lang, Y.C. Impacts of Environmental Factors on Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency: An Insight from Gross Primary Production and Evapotranspiration Dynamics. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 362, 110382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.E.; Meacham-Hensold, K.; Lemonnier, P.; Slattery, R.A.; Benjamin, C.; Bernacchi, C.J.; Lawson, T.; Cavanagh, A.P. The Effect of Increasing Temperature on Crop Photosynthesis: From Enzymes to Ecosystems. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2822–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, G.J.; Angert, A.L.; Usui, T. Temperature Dependence and Genetic Variation in Resource Acquisition Strategies in a Model Freshwater Plant. Funct. Ecol. 2024, 38, 1600–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, A.T.; Perkins, S.E.; Laffan, S.W.; Flores-Moreno, H.; Awasthy, M.; Tindall, M.L.; Sack, L.; Pitman, A.; Kattge, J.; Aarssen, L.W.; et al. Which Is a Better Predictor of Plant Traits: Temperature or Precipitation? J. Veg. Sci. 2014, 25, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, B.J.; Munson, S.M. Temperature Is Better than Precipitation as a Predictor of Plant Community Assembly across a Dryland Region. J. Veg. Sci. 2016, 27, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.B.; HilleRisLambers, J.; Kyriakidis, P.C.; Guan, Q.F.; Levine, J.M. Climate Variability Has a Stabilizing Effect on the Coexistence of Prairie Grasses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 12793–12798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cervigón, A.I.; Quintana-Ascencio, P.F.; Escudero, A.; Ferrer-Cervantes, M.E.; Sánchez, A.M.; Iriondo, J.M.; Olano, J.M. Demographic Effects of Interacting Species: Exploring Stable Coexistence under Increased Climatic Variability in a Semiarid Shrub Community. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonato, A.A.E.; Guimarães-Steinicke, C.; Stein, G.; Schreck, B.; Kattenborn, T.; Ebeling, A.; Posch, S.; Denzler, J.; Büchner, T.; Shadaydeh, M.; et al. Seasonal Shifts in Plant Diversity Effects on Above-Ground–below-Ground Phenological Synchrony. J. Ecol. 2025, 113, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korell, L.; Auge, H.; Chase, J.M.; Harpole, W.S.; Knight, T.M. Responses of Plant Diversity to Precipitation Change Are Strongest at Local Spatial Scales and in Drylands. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, K.L.; Chen, F.S.; Huang, C.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, F.C.; Zhu, G.J.; Bu, W.S.; Fang, X.M.; Guo, L.P. The Elevational Distribution Patterns of Plant Diversity and Phylogenetic Structure Vary Geographically across Eight Subtropical Mountains. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.C.; Ao, S.C.; He, F.Z.; Resh, V.H.; Cai, Q.H. Elevation Shapes Biodiversity Patterns through Metacommunity-Structuring Processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Liu, Y.J.; Hardrath, A.; Jin, H.F.; van Kleunen, M. Increases in Multiple Resources Promote Competitive Ability of Naturalized Non-Native Plants. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbritter, A.H.; Fior, S.; Keller, I.; Billeter, R.; Edwards, P.J.; Holderegger, R.; Karrenberg, S.; Pluess, A.R.; Widmer, A.; Alexander, J.M. Trait Differentiation and Adaptation of Plants along Elevation Gradients. J. Evol. Biol. 2018, 31, 784–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.N.; Gesang, Q.Z.; Luo, J.F.; Wu, X.L.; Rebi, A.; You, Y.G.; Zhou, J.X. Drivers of Plant Diversification along an Altitudinal Gradient in the Alpine Desert Grassland, Northern Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 53, e02987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Musciano, M.; Calvia, G.; Ruggero, A.; Farris, E.; Ricci, L.; Frattaroli, A.R.; Bagella, S. Elevational Patterns of Plant Species Richness and Phylogenetic Diversity in a Mediterranean Island. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2024, 65, 125815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.C.; Bestion, E.; Warfield, R.; Yvon-Durocher, G. Changes in Temperature Alter the Relationship between Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 10989–10994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hao, H.G.; Zhang, W.G.; Liu, P.; Sun, L.H. Evaluation of ecological protection and restoration effectiveness based on “pattern-quality-service” in Irtysh River basin. Res. Environ. Sci. 2022, 35, 2495–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.W.; Xu, Z.R.; Chen, J.X.; Xu, Q.H. Nutrient content of five natural poplar forests in the Irtysh River Basin in Xinjiang. Arid Zone Res. 2021, 38, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Zhang, D.M.; Zhang, W. Effects of human activities on carbon storage in the Irtysh River Basin. Arid Zone Res. 2023, 40, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.J.M.; Walker, B.E.; Black, N.; Govaerts, R.H.A.; Ondo, I.; Turner, R.; Nic Lughadha, E. rWCVP: A Companion R Package for the World Checklist of Vascular Plants. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.W.; Xiao, C.; Ma, J.S. A dataset on catalogue of alien plants in China. Biodivers. Sci. 2022, 30, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.M.; Mao, L.F.; Yang, T.; Ye, J.F.; Liu, B.; Li, H.L.; Sun, M.; Miller, J.T.; Mathews, S.; Hu, H.H.; et al. Evolutionary History of the Angiosperm Flora of China. Nature 2018, 554, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.Z.; Ding, Y.X.; Liu, W.Z.; Li, Z. 1 Km Monthly Temperature and Precipitation Dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.R.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, M.; Guan, N.Q.; Wang, Y.W.; Jiang, R.H.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wu, M.J.; Xia, F.C. Effect of Thinning Intensity on Understory Herbaceous Diversity and Biomass in Mixed Coniferous and Broad-Leaved Forests of Changbai Mountain. For. Ecosyst. 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kofahi, S.D.; Al-Kafawin, A.M.; Al-Gharaibeh, M.M. Investigating Domestic Gardens Landscape Plant Diversity, Implications for Valuable Plant Species Conservation. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 21259–21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.S.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.G.; Mao, L.F. glmm.hp: An R Package for Computing Individual Effect of Predictors in Generalized Linear Mixed Models. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

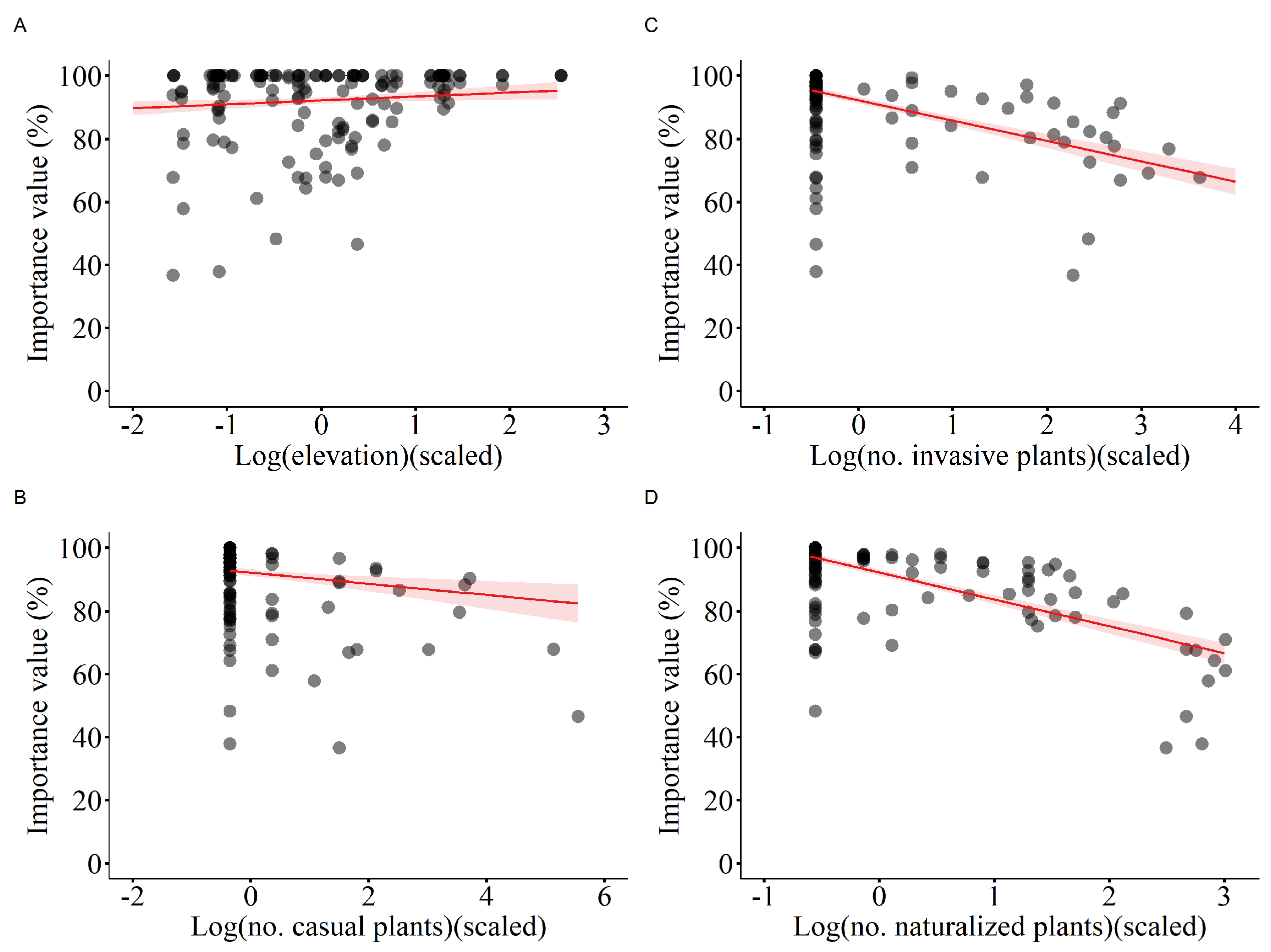

| Term | Estimate | SE | t-value | P-value | Ind. R2 | Ind. perc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.92 | 0.01 | 182.87 | <0.001 | / | / |

| Elevation | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.39 | 0.021 | 0.02 | 2.41 |

| NCP | -0.02 | 0.01 | -3.23 | 0.002 | 0.09 | 12.18 |

| NIP | -0.06 | 0.01 | -12.60 | <0.001 | 0.22 | 29.23 |

| NNP | -0.09 | 0.01 | -16.08 | <0.001 | 0.43 | 56.18 |

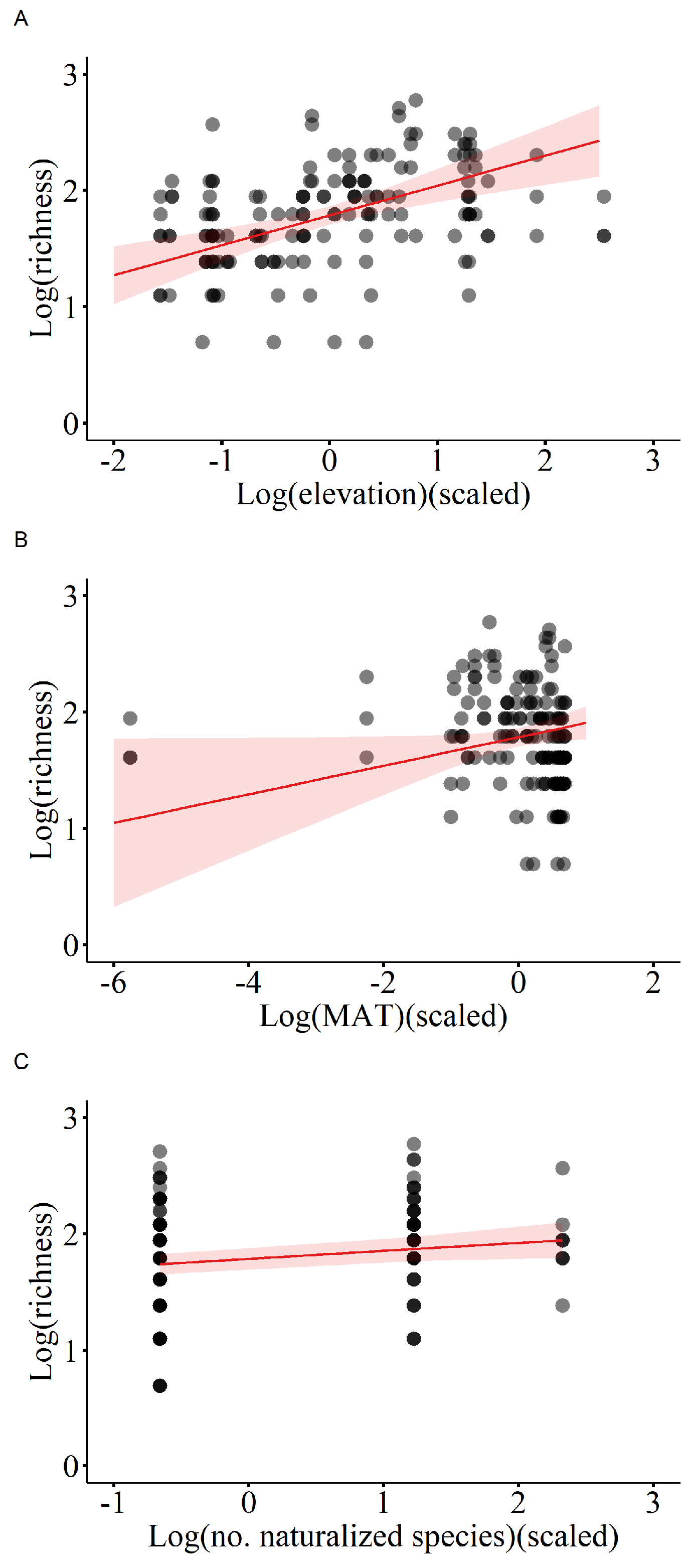

| Term | Estimate | SE | t-value | P-value | Ind. R2 | Ind. perc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.79 | 0.04 | 45.36 | <0.001 | / | / |

| Elevation | 0.26 | 0.06 | 4.27 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 72.29 |

| MAT | 0.12 | 0.06 | 2.02 | 0.048 | 0.03 | 14.23 |

| NNS | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.40 | 0.018 | 0.03 | 13.48 |

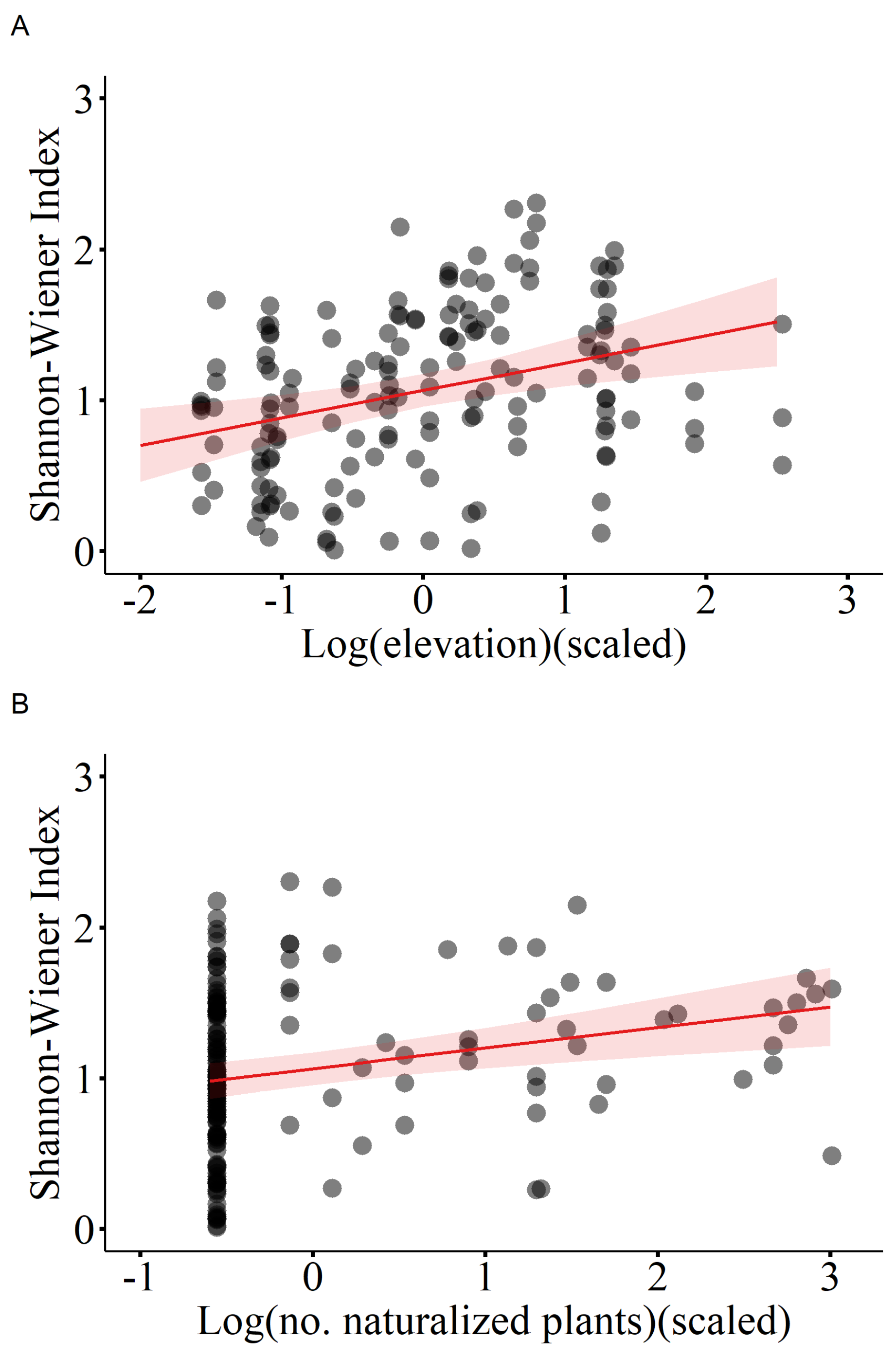

| Term | Estimate | SE | t-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.58 | 0.02 | 23.92 | <0.001 |

| NNP | 0.06 | 0.02 | 2.92 | 0.004 |

| Term | Estimate | SE | t-value | P-value | Ind. R2 | Ind. perc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.07 | 0.05 | 19.41 | <0.001 | / | / |

| Elevation | 0.18 | 0.06 | 3.30 | 0.002 | 0.10 | 63.37 |

| NNP | 0.14 | 0.04 | 3.44 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 36.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).