1. Introduction

In Poland, between 1990 and 2009, 76% of road accidents were caused by the drivers themselves, with 60% of these incidents being due to distraction and concentration problems [

1,

2,

3]. This is particularly significant in the context of the growing number of people suffering from neurological diseases, which can affect their ability to concentrate and react while driving. One example of such a disease is a stroke – a condition that affects 2.5 million new patients annually worldwide, and 33 million people live with its consequences. In Poland, 60-70 thousand stroke cases are reported each year, posing challenges in rehabilitation and public health, especially since strokes are the leading cause of disability [

4,

5,

6].

The aging of society is an additional factor that could exacerbate these problems. By 2050, people aged 65 and above will make up 32.7% of Poland’s population [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Combined with the rising number of individuals suffering from neurological diseases, this may lead to an increase in road accidents caused by the health problems of drivers, as well as their ability to maintain proper concentration and reaction times. Data from the USA shows that in 2015, 391,000 people were injured and 3,477 people were killed in accidents caused by distracted drivers, emphasizing the importance of maintaining full concentration on the road, especially for older individuals, whose risk of stroke and other health issues is increasing.

In response to these challenges, there has been an analysis of current technologies aimed at improving driving re-education, particularly through driving simulators. Various systems have been developed to aid in both driving education and rehabilitation. A classic solution is a driving simulator, based on analyzing data displayed on a monitor in front of the driver and responding accordingly using only the steering wheel. This approach is outlined in patents such as US 5888074 A, US 2015024347 A1, and US 20110076649 A1, where the focus is on driving scenarios like navigating through traffic congestion [

11,

12,

13].

Another approach, as seen in the US8770980 B2 patent, is the development of an adaptive mechatronic device designed to replicate the typical driving environment[

14]. This device includes displays, sensors, and software that enhance the realism of the driving experience, providing an effective tool for driving training. A similar technology, introduced in the US 8894415-B2 patent, focuses on rehabilitation for patients with motor dysfunctions, allowing them to regain necessary motor skills for driving [

15]. These simulators, equipped with specialized software and mechanical components like steering wheels, allow for multi-mode training, including assisted steering and resistance torque, to simulate real driving conditions.

Commercially available mechatronic devices, such as the Luna EMG system by EGZOTech, also provide rehabilitation solutions, though not specifically designed for driving. This device uses virtual reality and is equipped with interchangeable attachments, including a steering wheel-shaped grip for functional rehabilitation of drivers. Additionally, devices like the DS250 and DS600 models by DriveSafety focus specifically on driving simulation and rehabilitation, offering advanced systems at a high cost, exceeding 100,000 PLN [

16,

17,

18].

Rehabilitation research, such as that by S. George et al. (2014), emphasizes two main objectives for driver re-education: retraining motor, cognitive, and sensory processing skills, and directly enhancing driving abilities through simulators or in-car exercises [

19]. This research suggests that a comprehensive approach combining motor training, cognitive development, and physical exercises can effectively improve driving skills [

20].

Despite the availability of these technologies, there remains a gap in the market for a comprehensive solution that combines driving rehabilitation with the specific needs of individuals recovering from conditions like COVID-19 or neurological disorders. The objective of the project described in this article is to develop an innovative mechatronic rehabilitation device that addresses the needs of drivers recovering from conditions such as COVID-19, strokes, or age-related cognitive and physical impairments [

21]. This is especially important given the growing global demand for such solutions, as evidenced by studies indicating that 87% of COVID-19 survivors face significant health issues, including prolonged fatigue and neurological symptoms, which impact driving abilities [

22].

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this project was to develop a mechatronic training device designed to enhance driving skills. This multidisciplinary project is particularly dedicated to individuals who, prior to illness, were active drivers but now face motor-visual coordination issues, concentration difficulties, as well as fear and anxiety about returning to driving due to the effects of COVID-19 or neurological conditions. The solution was also designed for elderly drivers, whose ability to drive safely can rapidly change due to an increased risk of age-related diseases. The proposed system offers a quantitative assessment of their driving-related skills and provides a customised rehabilitation program to support recovery. This is not a conventional driving simulator, which merely allows the user to simulate vehicle operation based on on-screen visuals. Instead, it is an innovative rehabilitation device that facilitates comprehensive recovery and rehabilitation [

23,

24].

During the initial research phase, the project team thoroughly defined and analysed the key challenges faced by ill and elderly drivers. A detailed literature review and industry analysis were conducted alongside an evaluation of existing driver-assistive devices. Additionally, interviews were held with 10 patients and elderly drivers, 2 rehabilitation specialists, and 1 driving instructor. Based on the insights gained, fundamental design assumptions were formulated, leading to the development of a preliminary concept for the device.

The final version of this mechatronic rehabilitation device, as described in this article, was developed based on proprietary research and patented solutions. The project incorporates patents granted in Poland, including: Patent No. 231292 (18.02.2019) – Mechatronic Steering Wheel Overlay. Patent No. 238042 (30.06.2021) – Mechatronic Device for Rehabilitation and Driving Assistance, Particularly for Automobiles.

During the design phase of the project, particular attention was given to numerical values of anthropometric data and upper limb motion parameters, ensuring the device's construction would accommodate a broad range of potential users—drivers. The applied data and industry standards, derived from available literature on adult populations, cover women aged 20–60 and men aged 20–65. The collected data, crucial to the project, comply with European standards (EIM 979). The primary reference for the device’s design is the anthropometric data of women from the 5th percentile group and men from the 95th percentile group. The selection and corresponding structural design were developed in accordance with PN-EN 547-3 ("Human Body Measurements – Anthropometric Data").

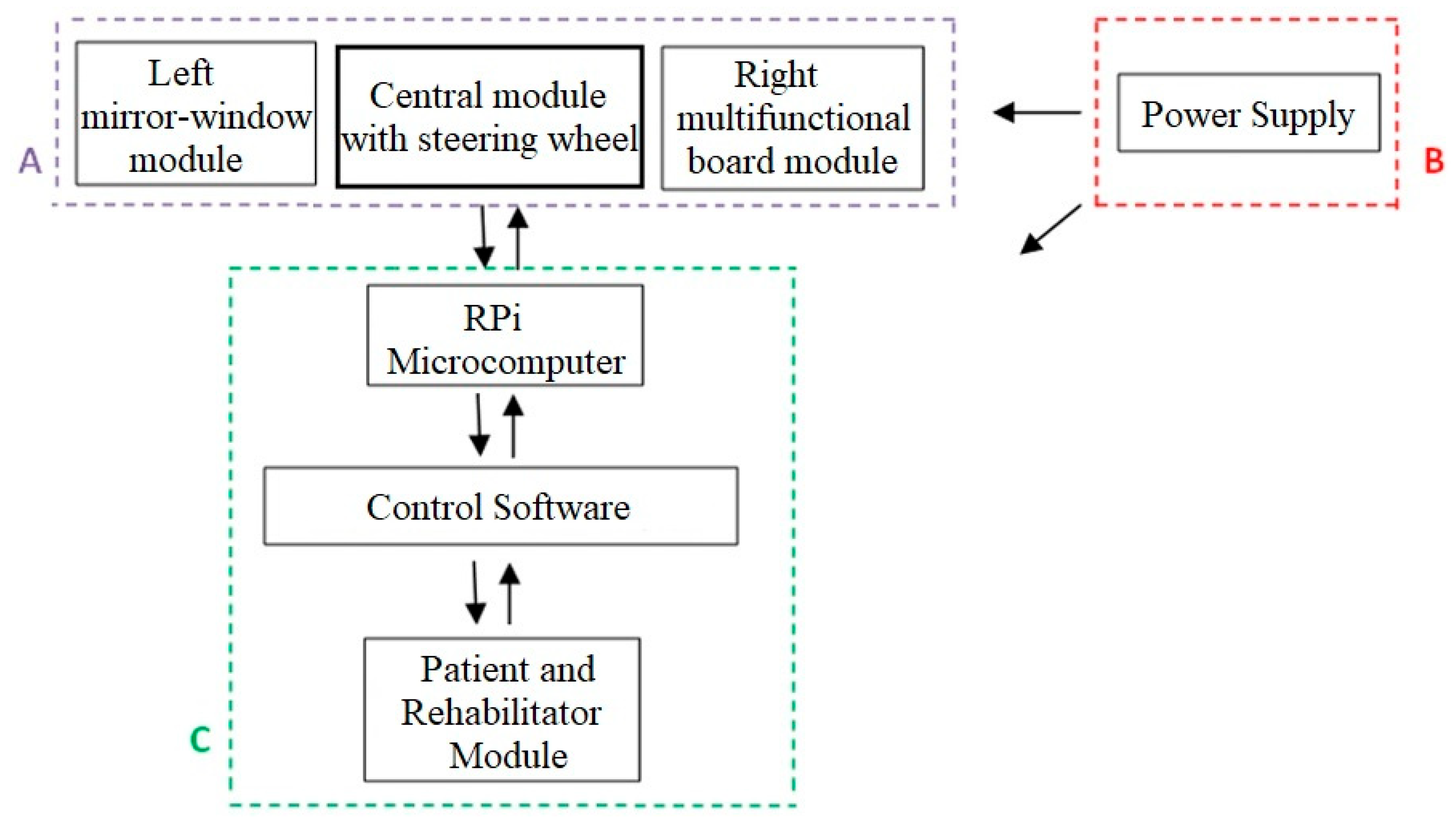

The driver training device, specifically designed for individuals recovering from COVID-19, those with neurological conditions, and elderly users, features a base unit equipped with dedicated components to support the rehabilitation process. These modules are connected via an electronic control module to a Raspberry Pi microcomputer using a bidirectional data bus. The system also includes custom software, designed exclusively for this device, which is operated via a touchscreen display.

The key components of the described system include:

Central module with a steering wheel and a task module positioned below it;

Left mirror-window module;

Right multifunctional panel module.

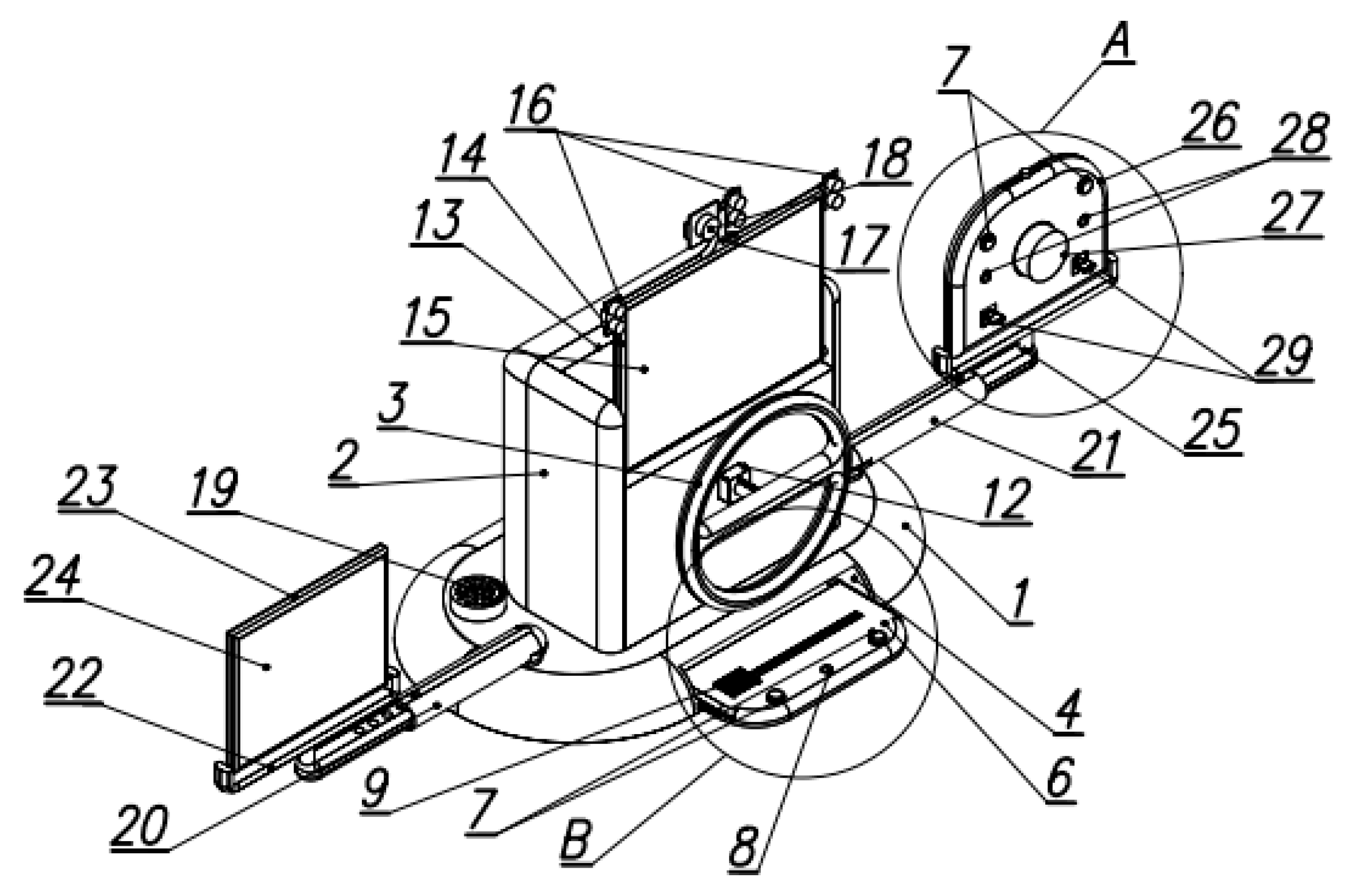

The base of the device is shaped like a flat plate. At the front of the base, directly in front of the user/patient, there is a task module in the form of a retractable flat drawer with gently rounded edges. On the upper surface of the task module, to the right and left, directly in front of the user, mushroom-shaped buttons are installed, one on each side. It is important to note that the left mushroom button is blue, while the right one is yellow. On the upper surface of the task module, between the blue and yellow mushroom buttons, three LEDs of different colours are embedded, corresponding, among other things, to the button colours.

On the upper surface of the task module, just behind the buttons, a slider button is mounted. This button has a guide rail running parallel to the line of the three preceding objects. Additionally, the upper surface of this button is shaped like a flattened cube.

At the centre of the base, on its upper surface, the central module is installed. It consists of a cubic housing, with an encoder mounted in the middle of its front panel. A steering wheel is attached to the front of this housing, positioned directly above the previously described task module. The steering wheel can be removed and replaced with an alternative control object, such as an attachment simulating a motorcycle or bicycle handlebar.

Above the housing with the steering wheel, there is a mount for the central display. On the left side of the central display housing, in its upper part, distance sensors are installed. These distance sensors can be manually adjusted to align with the user’s position—considering factors such as the user’s height or the current tilt angle of the central display housing relative to the base. Additionally, on the upper edge of the central display housing, there is another distance sensor along with a camera.

The device set also includes speakers, which can be repositioned and are used to generate sound for implementing proprietary tasks with biofeedback (

Figure 1).

The device also includes a left mirror-window module, which consists of a movable display mounted on an extendable arm positioned to the left of the central module. Both the display position and the length of the arm can be adjusted. The display presents tasks to be performed, including adjustments related to field-of-view correction.

On the right side of the central module, there is a right multifunctional panel module. This module is designed as a panel mounted on a movable, adjustable arm. The panel’s rotation and tilt angle can also be modified. The panel features two rows of buttons located in the middle and upper sections. The buttons in each row require different pressing techniques, encouraging the user to engage their wrist and fingers in varying ways. Additionally, between these two rows of buttons, a rotary button is centrally positioned. The shape, size, and texture of this rotary button can be customised.

Each module's position can be adjusted (including tilt angle and distance from the base), allowing for a personalised approach tailored to the user. Furthermore, selected task response buttons are made from different materials and feature surfaces with varying textures. Their diverse sizes and pressing requirements significantly contribute to the rehabilitation process by stimulating sensory receptors located on the inner surface of the hand and fingers. The variety in button colours and numbers across different modules—such as the right multifunctional panel or task module—ensures that the exercises remain engaging and effective in the rehabilitation process.

Before the user begins performing exercises tailored to their individual needs—taking into account their dysfunctions and current upper limb motor abilities while driving—it is necessary to conduct a diagnostic assessment. This involves selecting which of the two button modules will be used (either the right multifunctional panel or the task module) and requesting the patient to press specific control buttons. Based on this assessment, a personalised set of exercises is proposed for the patient to complete. The results obtained through these exercises are then recorded and presented to the patient, providing them with an overview of their current performance.

The patient has the opportunity to practice not only the range of motion of the steering wheel, which is fundamental to driving a car, but also the ability to train the entire upper limb, particularly the wrist and finger movements, through appropriate gripping and pressing of dedicated components in each module. The device’s adjustable module settings, as well as buttons made from different materials with varying textures, sizes, and shapes, significantly accelerate the rehabilitation process. This is achieved by stimulating the skin receptors located on the inner hand and fingers. Additionally, the diverse colors and varying numbers of buttons in each module (such as the right functional panel or task module) make rehabilitation exercises for drivers recovering from COVID-19, individuals with neurological dysfunctions, or elderly people who wish to actively participate in society by safely driving a vehicle much more engaging compared to conventional rehabilitation methods, even those using traditional driving simulators with only a steering wheel.

The device enables engaging rehabilitation exercises incorporating biofeedback, particularly with the left mirror-window module, where the display presents images directly linked to the tasks displayed on the main screen of the central module. The ability to change color schemes combined with multicolored button combinations encourages the patient to not only practice movement range and precision but also to engage in cognitive training, including problem-solving and decision-making tasks displayed on the main or side screen simulating a side mirror. This enhances a faster and safer return to comfortable driving, considering biofeedback, increased upper limb joint mobility, and necessary head movements based on exercise sets and instructions displayed on the device or provided by a driving instructor.

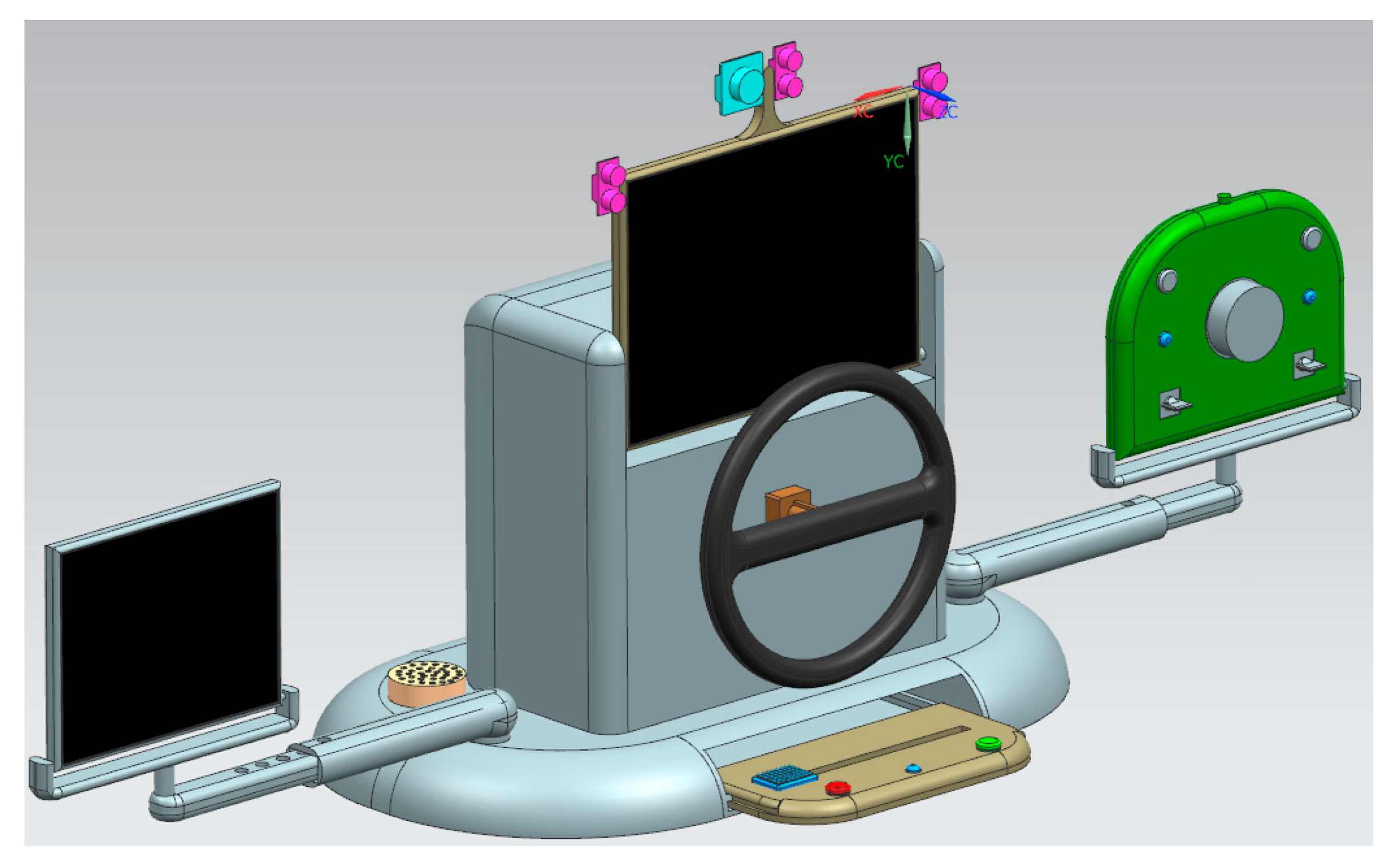

The CAD models were created based on a previously developed conceptual solution using NX Siemens CAD software (

Figure 2).

2.1. Prototype of the Device

The mechatronic approach to design allowed for the refinement of the previously proposed geometric features and components of the device based on obtained conclusions. By improving the construction models of the modules mounted on the base—such as the left mirror-window module and the right multifunctional panel module in relation to the central module with a large display and detachable steering wheel, as well as the task module with physical buttons and LEDs, while also considering the ergonomics of the performed movements—this approach enabled the optimization of the device’s structural design.

Following this, selected CAD models were prepared for further strength analysis of the proposed solution, and the prototype construction process was initiated. In the case of the left mirror-window module, which serves as a mirrored counterpart to the right multifunctional panel module, ensuring the stable mounting of these modules was crucial for user comfort. Their placement on the base was dictated by the ergonomics of limb movement—particularly the left upper limb for the left mirror-window module and the right upper limb for the right multifunctional panel module.

It is worth noting the method of mounting these modules on the base. The arms of both the left mirror-window module and the right multifunctional panel module are aligned along a central symmetry axis in their initial position. This design consideration aimed to ensure that the base experiences a balanced distribution of weight.

It is also essential to highlight that during the prototype construction and the iterative development of each module, extensive testing was required. These tests primarily focused on evaluating the correct operation of the left mirror-window module, the central module, the right multifunctional panel module, and the task module. In the final development and prototyping stage, 3D printing proved to be an indispensable tool. It played a crucial role in refining the buttons located on the task module and the right multifunctional panel module. These buttons were manufactured in successive testing phases using Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) technology, an additive manufacturing technique based on material extrusion. The Prusa i3 MK3 3D printer was used for this purpose. Polylactic Acid (PLA) filament was selected as the printing material due to its minimal printing constraints. Its low extrusion temperature (ranging from 190-220°C) and the absence of a requirement for a heated chamber made it an optimal choice. PLA is derived from renewable resources such as corn starch, sugarcane, and tapioca roots, making it highly biodegradable and cost-effective [

25,

26].

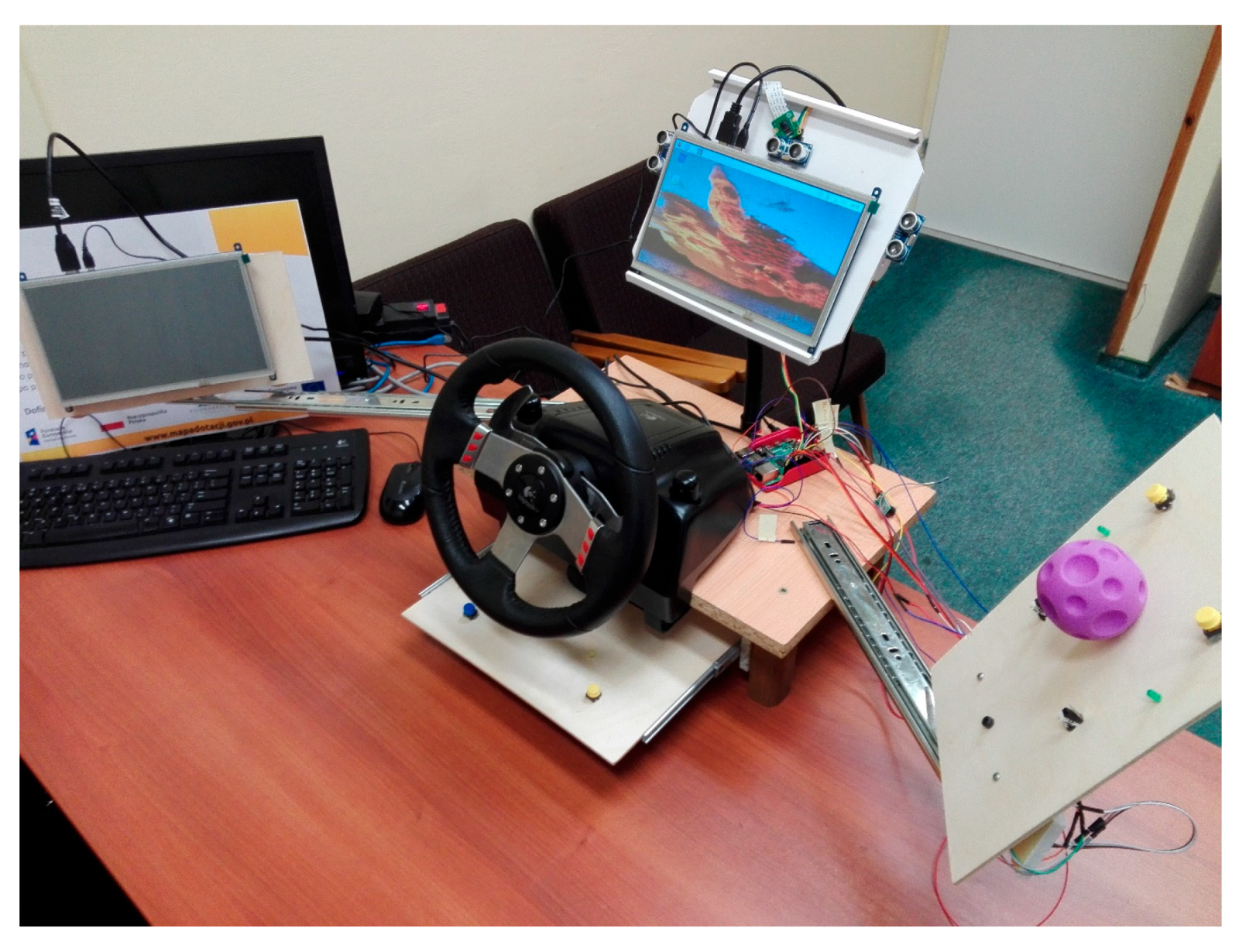

The prototype of the driver training (

Figure 3) device consists of several essential components, including:

A microcomputer, specifically the Raspberry Pi 4B (8GB);

Two touchscreen displays, resistive LCD IPS 10.1'' (1024x600px HDMI + GPIO) - Waveshare 11870;

An LED system;

Control button modules, including large-format buttons and WK315 straight-lever limit switches;

Various rotational and distance sensors

The device described in this article represents a inovative approach to driver rehabilitation and training. It not only enables standard driving exercises but also integrates task and panel modules to engage the entire upper body, head, and torso. Unlike conventional simulators that focus primarily on steering movements and forward motion, this solution prioritises comprehensive situational awareness, precision of movement, decision-making skills, and reaction time—all of which are essential for safe driving.

This system is particularly designed for individuals requiring intensive active exercises, with a focus on simultaneous upper limb and head movement, ensuring precise and repeatable motor actions in response to stimuli. A dedicated diagnostic, training, and reporting system has been developed, allowing for a customised rehabilitation programme tailored to each driver’s motor impairments caused by illness or injury.

In addition to improving range and precision of motion, the system also enhances cognitive skills, including focus and logical thinking, by adapting exercises to each driver’s unique needs. Moreover, the interactive and engaging nature of the device accelerates rehabilitation, fostering higher motivation and involvement in the recovery process.

2.2. Software Development

The software development process for this device was not approached solely from an engineering perspective, as is common in many projects. Instead, special attention was given to rehabilitation-oriented software design, particularly concerning the central module. While the fundamental features of this module have been previously discussed, an important design consideration was the intentional positioning of the steering wheel and central module at a higher level than typically found in passenger cars. This setup encourages the user to maintain their hands in an elevated position, preventing them from resting on a table or their thighs, thereby promoting active upper limb engagement.

For the left mirror-window module, the development process focused on determining whether restricting the displayed image area—differentiating between a side window and a side mirror—was necessary. Ultimately, it was concluded that the nature of the exercises and the user's focus on the displayed information were more critical than limiting the screen size.

Figure 4 illustrates the system concept of the driver training and rehabilitation device.

Further work focused on refining the software in the context of rehabilitation through the implementation of the right multifunctional panel module and the task module, particularly concerning movement ergonomics. Each of these modules includes dedicated interactive elements and indicator LEDs. The introduction of specialised buttons within these modules enforces active upper limb exercises, emphasising rehabilitation, movement speed, and precision, while incorporating biofeedback mechanisms.

The key components of this software have already been outlined, including the diagnostic module, exercise module, and reporting module, which generates feedback after each completed task. The software was developed in Python using Visual Studio Code, with separate script files corresponding to different functionalities, each of which can be executed independently [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Due to the extensive lines of code, the article provides sample screenshots illustrating the graphical user interface (

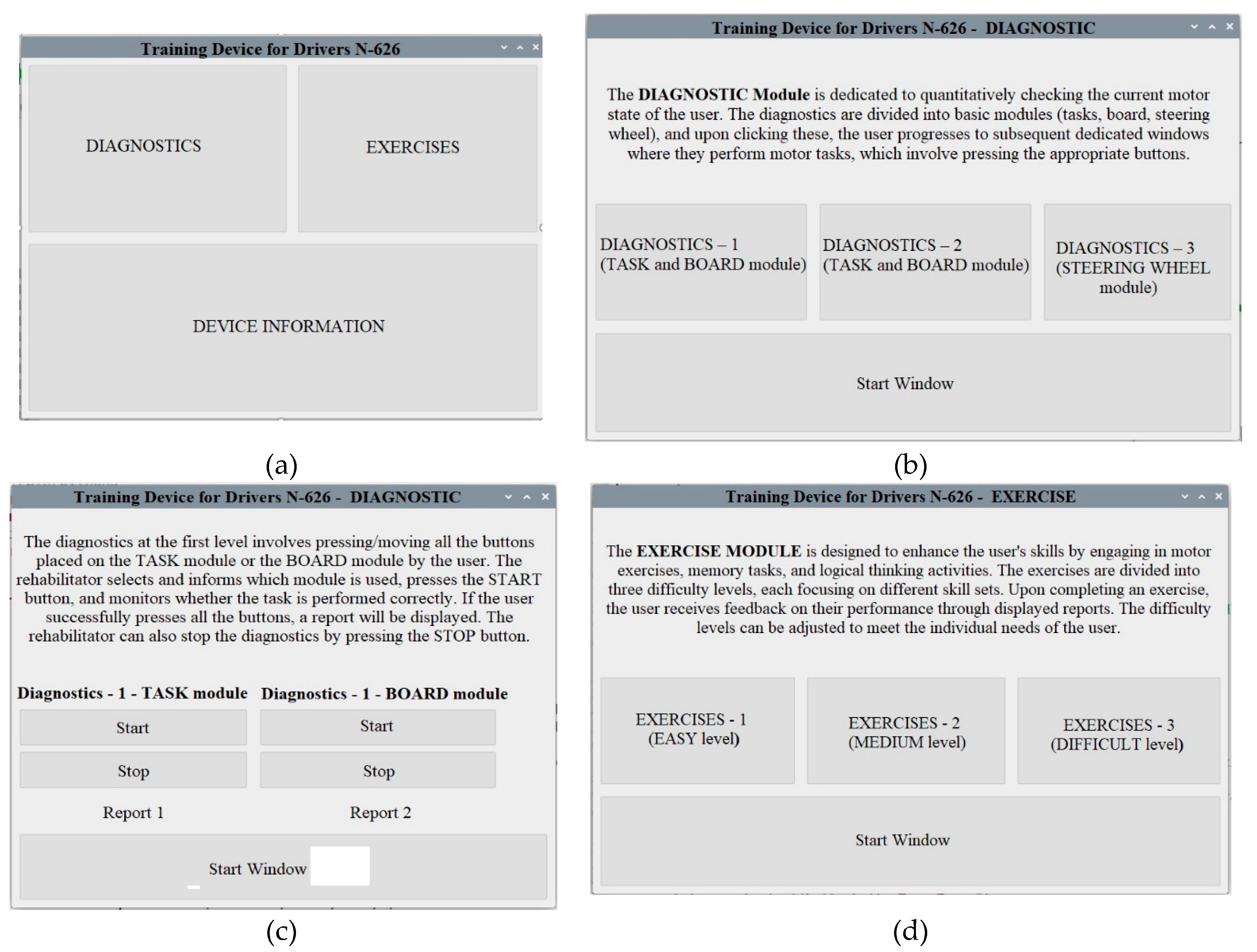

Figure 5). Upon launching the device, the start window appears (

Figure 5a), allowing the user to choose between the diagnostic module, exercise module, and device information. The project title is displayed at the top of each window. At the beginning of the session, it is recommended that the user access the device information window, which provides a brief description of the system, details of the project, as well as the project logo and an image of the device model.

The first recommended step is to initiate the diagnostic module (

Figure 5b), where the user is guided through the entire diagnostic process and given the option to select one of three rounds—assessing their range of motion and interaction with the device. During this process, the user must press the designated control buttons on specific modules of the system. The results obtained are subsequently displayed in reports (Figures 5c). The user's objective is to press all the buttons in the shortest possible time. If they are unable to complete the task, the rehabilitation specialist has the option to terminate the diagnostic session early by pressing the stop button. For this reason, both possible report formats are included in the screenshots.

Following the diagnostic phase, the user proceeds to the exercise tasks, which involve performing specific movement patterns as assigned by the rehabilitation specialist. These exercises are structured across three predefined difficulty levels—easy, medium, and difficult—allowing the user to select the appropriate level (

Figure 5d).

3. Results

As part of the conducted research, the developed prototype was tested under simulated operational conditions. Due to cost constraints, the new technology was evaluated in an environment closely resembling real-world conditions, focusing on several operational parameters. These included the range of motion exercises performed by drivers using the system, the application of biofeedback through various interactive buttons, and the accuracy of each application module’s functionality.

The testing was conducted with the participation of four individuals aged 40, 53, 67, and 68, comprising two women and two men. Notably, two participants had previously contracted COVID-19 and suffered from neurological conditions. Over the course of a one-week testing period, none of the participants reported any issues related to software malfunctions.

Regarding the obtained results, improvements were assessed based on errors in selecting the correct buttons, the accuracy of pressing them, and reaction times during task execution, as recorded by the system. Depending on the participant, performance improvements ranged from 10% to 30%.

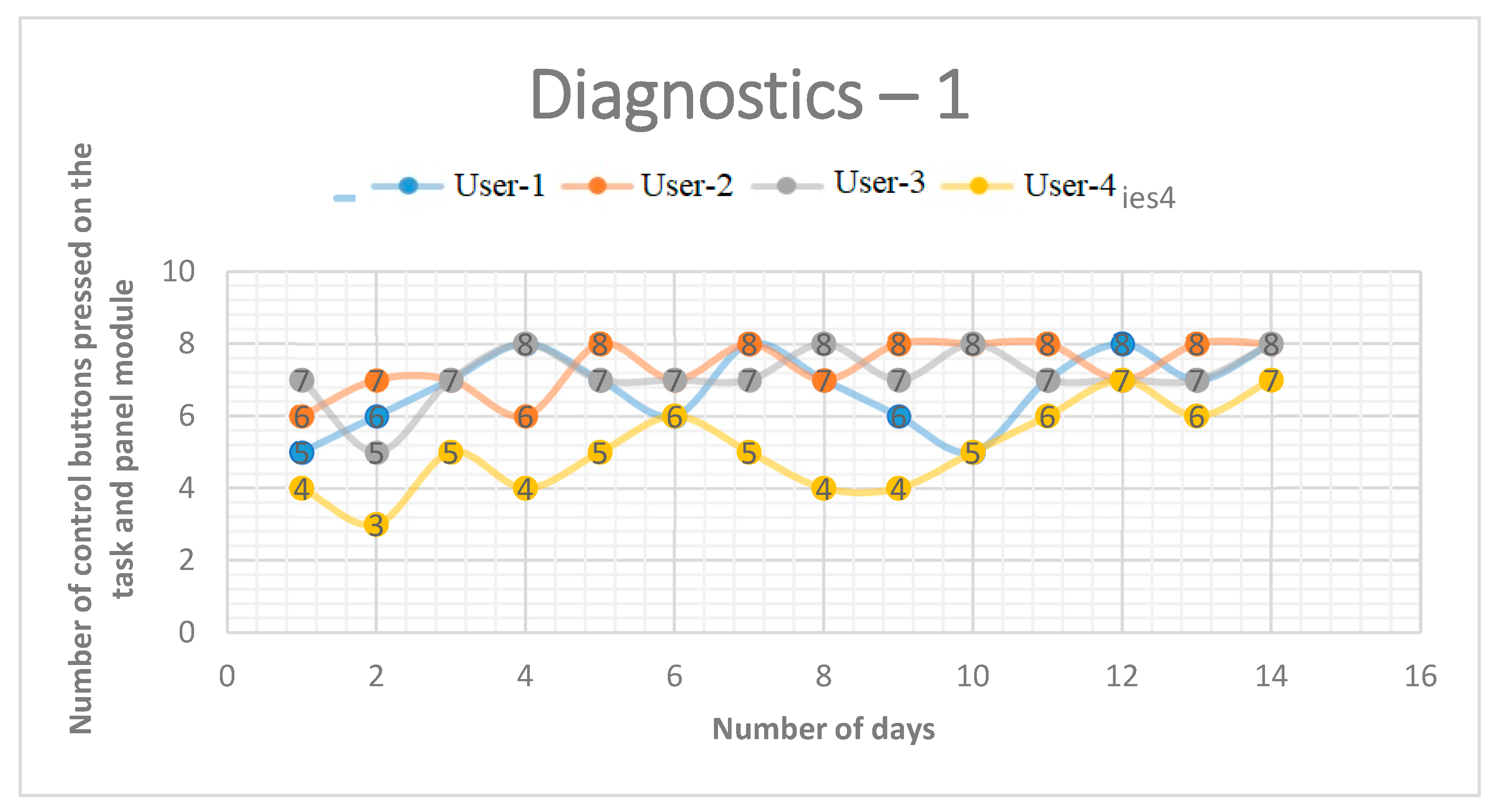

Figure 6 presents the results of the initial diagnostic module tests, which were conducted over 14 days with the four participants. During the diagnostics, the length and tilt angle of the right arm module were adjusted to match the anthropometric measurements of each user. The graph illustrates the results from "Diagnostics-1," which involved pressing and sliding all eight buttons in both the task module and the panel module.

Additionally, the diagnostic module includes two further testing phases—"Diagnostics-2" and "Diagnostics-3"—which separately evaluate the range of motion, speed of object manipulation within the task module and the panel module, as well as steering wheel control. Since the underlying software operation remains consistent across all modules,

Figure 6 depicts "Diagnostics-1," visualising the pressing and sliding of all buttons in a random order across both modules.

Furthermore, the system allows for the measurement and recording of both task completion time and the exact sequence in which actions were performed. The purpose of "Diagnostics-1" was to assess the participant's range of motion and use these results to tailor subsequent rehabilitation exercises. Consequently, individual reaction speeds will be presented in graphical form within the exercise module results.

The issues encountered by some participants in pressing all the control buttons may indicate limitations in the full range of motion of the upper limbs. Therefore, subsequent stages of the exercises take this into account, or the arm lengths of these modules may need to be adjusted. As shown in

Figure 6, Person 4 exhibited poorer performance, which could be indicative of a dysfunction, particularly during the early stages of the tests (on days 2, 8, and 9). However, by the end of the exercise period, this individual achieved much better results, pressing 6 to 7 of the 8 buttons. Similarly, Person 1 showed significant improvement over the course of the exercises. For the other two participants, the results were relatively consistent.

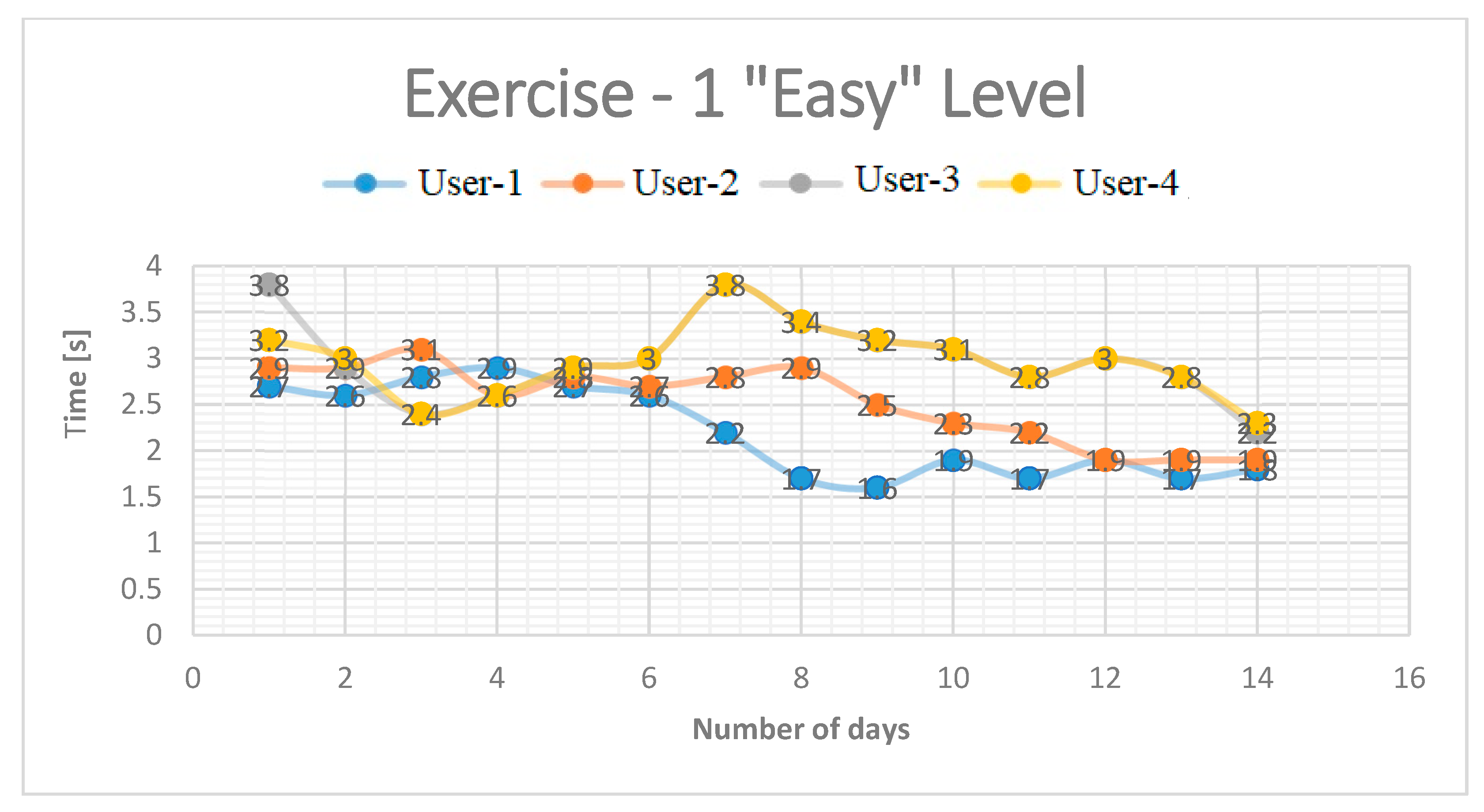

In the Exercise-1 tab at the "easy" level, the focus was on the speed at which both hands completed the task of pressing and sliding the task module's buttons. This task had to be performed in any order. The time achieved by participants ranged from 3.8 [s] to 1.8 [s], with the most significant improvements observed in Person 3 (see

Figure 7).

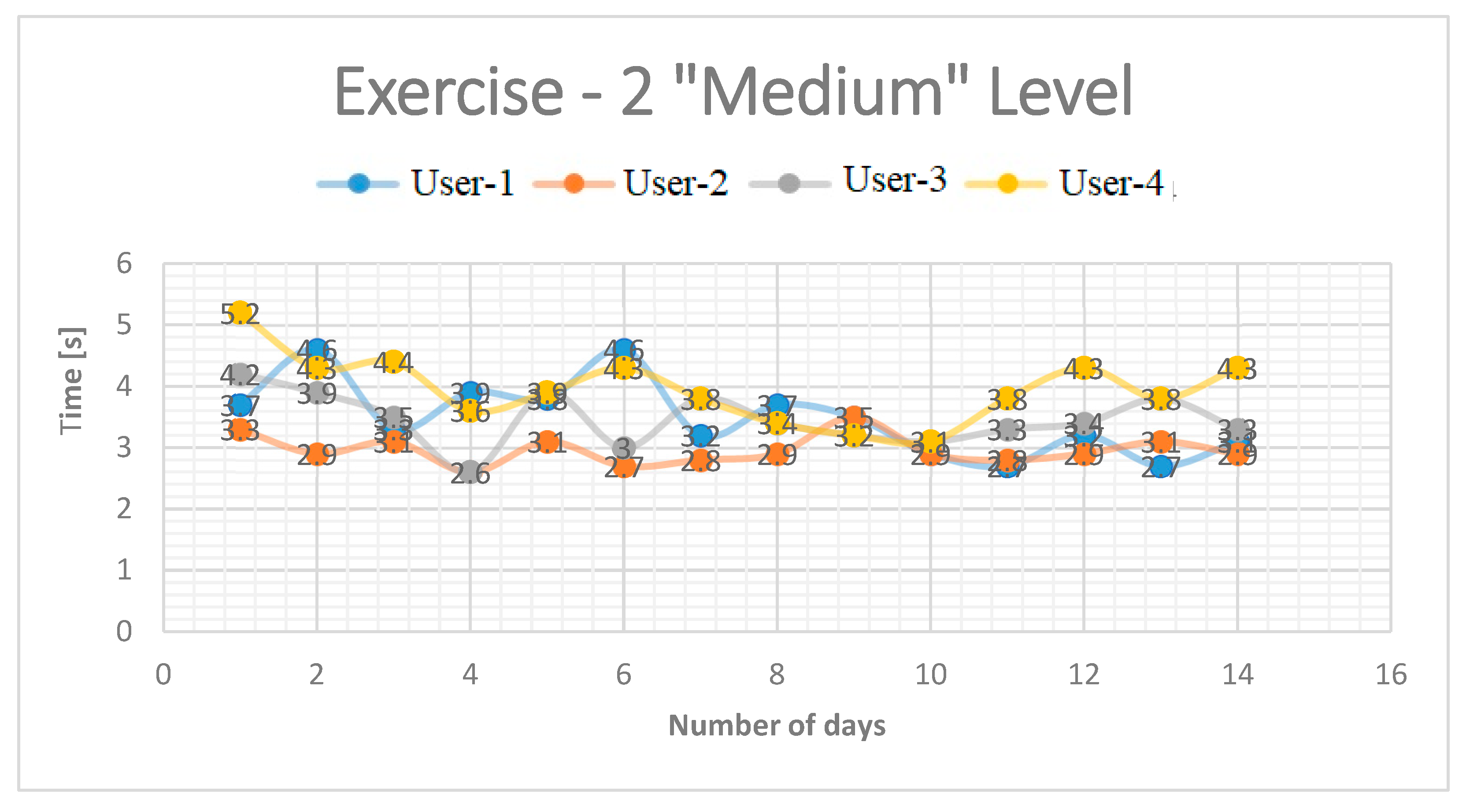

In the Exercise-2 tab at the "Medium" level, the focus shifted to the speed of the right upper limb while pressing and rotating the buttons on the board module. The task had to be completed in the sequence indicated by the LEDs. The system displayed the order in which the three buttons should be pressed, followed by a pause time. During this pause, participants were required to memorise the order of operations and then repeat them as quickly as possible. In addition to the reaction time measurement (

Figure 8), the report also provided information about which buttons were pressed.

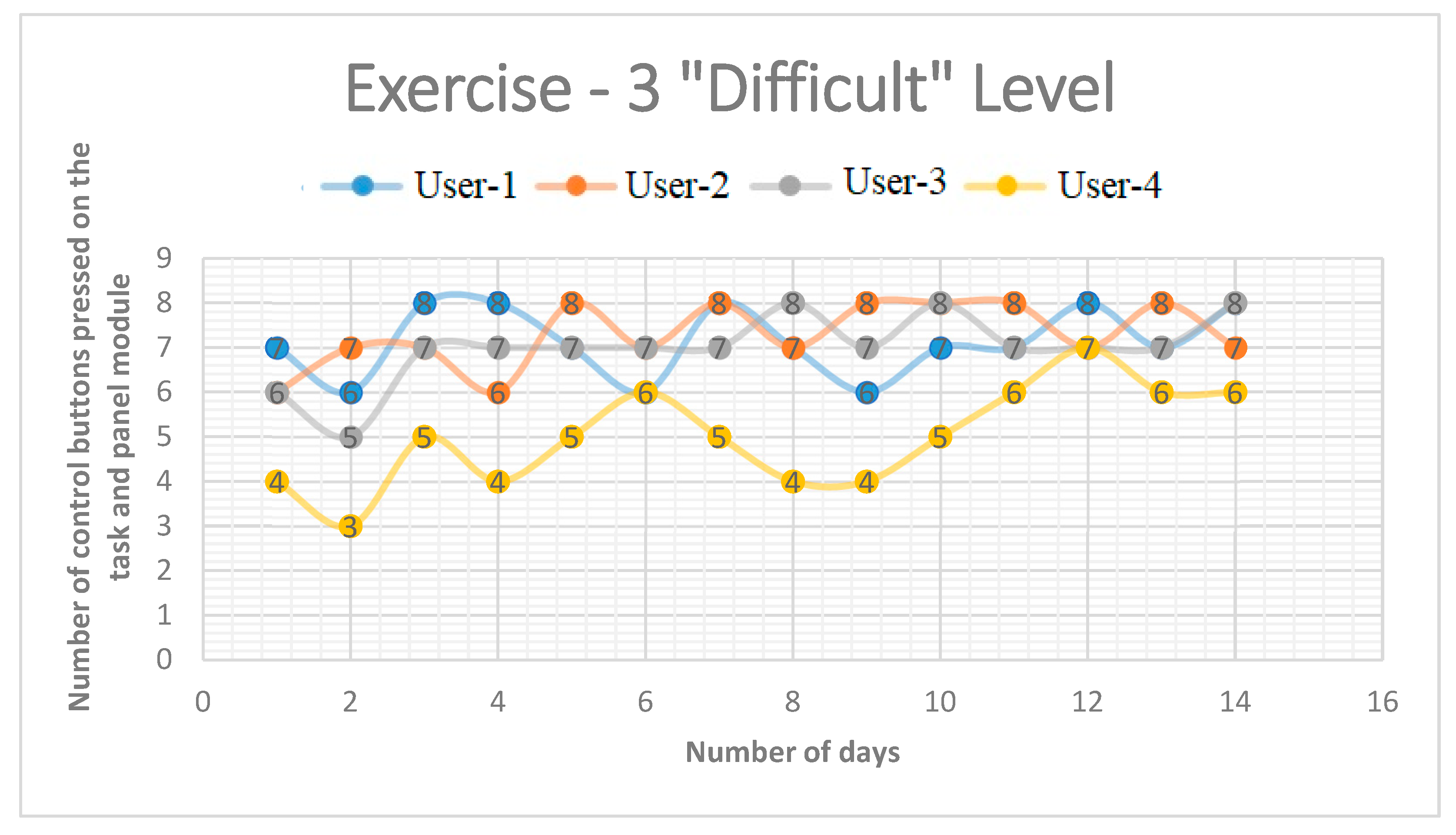

The chart in

Figure 9 presents the results from Exercise-3 at the "Difficult" level, which aimed to assess how, during vehicle operation, the user, while keeping both hands on the steering wheel, drives a simulated vehicle and simultaneously analyses the surroundings – in this case, the right side of the vehicle. The user’s reactions are tested by the simulated illumination of a corresponding indicator – an RGB LED on the right module of the board, triggering the need for a specific task. These tasks involve pressing or rotating the selected buttons on the board. The chart shows the number of errors made during the 14-day period.

This task specifically focused on the proper functioning of the right upper limb to reach the button, and then to position the hand correctly in order to press the button or rotate the knob either to the right or left. The buttons, arranged in pairs in two rows, require a different wrist position to press them. Additionally, at this level, the time taken for one test was not measured, although this information could be generated for the user in another report tab. The graph shows that person 4 made the most errors, with a high number of incorrect movements in the early days of the exercises (four wrong movements). This was anticipated when analyzing their diagnostic results in comparison to the others. Their worst results were observed on days 2, 4, 8, and 9, which were attributed to more significant movement dysfunctions. However, over the short testing period, this person was still able to achieve a final count of six errors in the later days. The remaining three individuals improved their results by eliminating one or three errors.

The solution described in the article is innovative and previously unseen. The device developed and detailed in the article was filed with the Patent Office of the Republic of Poland on 27th September 2022 under the title "Driver Exercise Device," patent number P.442373, authored by Jacek S. Tutak, Krzysztof Lew, Andrzej Burghardt, Michał Jurek, and Piotr Matłosz.

4. Conclusions

Treatment and rehabilitation are long-term processes, and the rapidly increasing number of individuals recovering from illnesses and injuries, as well as those requiring rehabilitation, often leads to the need for re-education in vehicle operation. Additionally, the aging population, not only in Poland but worldwide, is contributing to the growing number of older drivers, which will necessitate monitoring their driving skills. The driving capabilities of this group of drivers are not subjected to any specialized tests related to their coordination, visual-motor skills, concentration, or the ability to make quick and correct decisions.

This article describes the design and construction of a prototype of an innovative device for driver rehabilitation, particularly for individuals recovering from neurological conditions, older adults, and those with post-COVID complications. Unlike a typical simulator, this device is aimed at rehabilitation. It includes a base, a left mirror-window module (a movable display on an arm with a field-of-view correction), a central module with a large screen and a detachable steering wheel, and a right multifunctional control panel. In front of and beside the steering wheel are custom task modules with physical buttons and LEDs, as well as portable speakers for completing proprietary tasks that include biofeedback, which is vital for restoring concentration, visual-motor coordination, and decision-making speed. We also analyze head and torso movements using information from distance sensors and cameras on the modules.

The described device addresses the problem of rehabilitation for coordination, accuracy, reaction speed, performing visual-motor tasks, and concentration – all essential skills for safe vehicle operation, which may have been impaired due to injuries, illness, or aging. This solution is innovative and has not been encountered elsewhere in the world. The driver performs proprietary tasks, allowing the patient not only to practice the range of motion of the steering wheel, which is fundamental to driving a car, but also to train the entire upper limb, with a particular focus on the wrist and finger movements. These exercises involve the appropriate grip and pressing of dedicated components on each module.

The selected buttons for task responses are made from different materials and have a uniform texture, with their size and diversity significantly impacting the acceleration of the recovery process. This process stimulates skin receptors on the inner side of the hand, including the palms, while the different colours and numbers of buttons on each module (the right functional panel or task module) focus the patient's concentration. The task modules are sensor-equipped and contain electronic components that support biofeedback, which is crucial for the restoration of lost abilities and skills.

The rehabilitation exercises for drivers recovering from various illnesses and injuries, or for elderly individuals wishing to actively participate in social life by driving safely on their own, become much more engaging than conventional methods, even those using traditional car simulators with only a steering wheel. The device includes diagnostic, exercise, and reporting modules, along with external modules. In order to verify the proper functioning of the device, tests were carried out, the results of which are presented and analysed in the article. The described solution is expected to increase the speed of recovery and the driver’s involvement in rehabilitation by approximately 15%.

In the first tests, described in the article, four individuals, aged 40, 53, 67, and 68, participated in the exercises. The group consisted of two women and two men, two of whom had previously had COVID-19 and a neurological disorder. The tests were conducted over the course of one week of using the device. The results are promising, and detailed exercise data are provided in the article. Further studies involving a larger number of participants are planned in the near future to further develop the described prototype.

The described solution could become an important piece of equipment in rehabilitation centres, sanatoriums, and driving schools. Due to its compact design and the ease of assembling/disassembling the modules, the device is sure to be appreciated by rehabilitation professionals who operate independent rehabilitation services in private homes of patients.

The device described in the article will significantly improve the quality of life for a wide range of potential users and enable a safe return to driving for a large number of people with illnesses or elderly individuals, as previously mentioned. This will enhance the safety of not only the mentioned group of drivers but also all other road users – improving the safety of other drivers as well as pedestrians.

6. Patents

Application to the Patent Office of the Republic of Poland on 2022-09-27 entitled "Device for exercising drivers" no. P.442373 by Jacek S. Tutak, Krzysztof Lew, Andrzej Burghardt, Michał Jurek and Piotr Matłosz.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T. and K.L.; methodology, J.T. and K.L.; software, J.T. and K.L.; validation, J.T.; formal analysis, K.L.; investigation, J.T., K.L.; resources, J.T. and K.L.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T. and K.L.; writing—review and editing, K.L.; visualization, J.T.; supervision, K.L.; project administration, K.L..; funding acquisition, J.T.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Funding

Grant number N3_626 and funded by PCI – Podkarpackie Centrum Inowacji”.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

All data have been presented in the text of the paper, other data can be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reeves M.J. et al.: Sex differences in stroke. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, medical care, and outcomes. Lancet Neurology 2008, 7(10), 915–926.

- Peterson B.L., Won S., Geddes R.I. Sayeed I., Stein D.G.: Sex-related differences in effects of progesterone following neonatal hypoxic brain injury. Behavioural Brain Research. 2015, 286, 152–165.

- Just F., Baur K., Riener R., Klamroth-Marganska V., Rauter G.: Online adaptive compensation of the ARMin Rehabilitation Robot. 6th IEEE International Confer ence on IEEE 2016. Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob) 2016, 747–752.

- Kwolek A.: Rehabilitacja medyczna. Elsevier Urban & Partner, Wrocław 2003.

- Grabowska-Fudala B., Jaracz K., Górna K.: Zapadalność, śmiertelność i umieralność z powodu udarów mózgu – aktualne tendencje i prognozy na przyszłość. Przegląd Epidemiologiczny 2010, 64, 439–442.

- Feigin V.L., Forouzanfar M.H., Krishnamurthi R. et al.: Global and regional bur den of stroke during 1990–2010. Findings fromthe Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2014, 383(9913), 245–255.

- Seshadri S., Wolf A.: Lifetime risk of stroke and dementia: current concepts, and estimates from the framingham study. Lancet Neurology 2017, 6(12), 1106–1114.

- Mohan K.M., Wolfe C.D., Rudd A.G., Heuschmann P.U., Kolominsky-Rabas P.L., Grieve A.P.: Risk and cumulative risk of stroke recurrence. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2011, 42, 1489–1494. [CrossRef]

- N.C.f.H. Statistics. Health. United States 2011. Hyattsville US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyatlsville 2012.

- O’Donnell M.J. et al.: Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (INTERSTROKE study). A case-control study. Lancet 2010, 376(9735), 112–123.

- Kirchner Iii Albert H, Gish Kenneth W, Staplin Loren. System for Testing and Evaluating Driver Situational Awareness. Patent No.: US-5888074-A, Date of Patent: Mar.30, 1999.

- Best Aaron M, Turpin Aaron J, Purvis Aaron M, Barton J Ken, Havell David J, Welles Reginald T, Turpin Darrell R, Voorhees James W, Kearney John E, Price Camille B, Stahlman Nathan P. System, Method and Apparatus for Adaptive Driver Training. Patent No.: US-20110076649-A1, Date of Patent: Mar.31, 2011.

- Joon Woo SON, Myoung Ouk PARK, Woo Taik LEE, Hwa Kyung SHIN. Driving simulator apparatus and method of driver rehabilitation training using the same. Patent No.: US 20150024347-A1, Date of Patent: Jan. 22, 2015.

- Best A.M., Barton J.K., Havell D.J., Welles R.T., Turpin D.R., Voorhees J.V., Kearney J.E., Price C.B., Stahlman N.P., Turpin A.J., Purvis A.M. System, method and apparatus for adaptive driver training. Patent No.: US8770980B2, Date of Patent: Jul. 8, 2014.

- Kearney J.E., Turpin D.R., Price C.B., Stahlman N.P., Welles R.T., Havell D.J., Purvis A.M., Barton J.K., Best A.M., Turpin A.J., Voorhees J.W.System, Method and Apparatus for Driver Training. Patent No.: US-8894415-B2, Date of Patent: Nov. 25, 2014.

- Olczak A., Truszczyńska-Baszak A. Influence of the Passive Stabilization of the Trunk and Upper Limb on Selected Parameters of the Hand Motor Coordination, Grip Strength and Muscle Tension, in Post-Stroke Patients. J Clin Med. 2021 May 29;10(11):2402. [CrossRef]

- Zasadzka E., Tobis S., Trzmiel T., Marchewka R., Kozak D., Roksela A., Pieczyńska A., Hojan K. Application of an EMG-Rehabilitation Robot in Patients with Post-Coronavirus Fatigue Syndrome (COVID-19)-A Feasibility Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Aug 20;19(16):10398. [CrossRef]

- Johnson M., Van der Loos M.H.F., Burgar C.G., Shor P. Design and evaluation of Driver's SEAT: A car steering simulation environment for upper limb stroke therapy. Robotica 2003, Jan., 21(1):13-23. [CrossRef]

- George S, Crotty M, Gelinas I, Devos H. Rehabilitation for improving automobile driving after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Feb 25;2014(2):CD008357. PMID: 24567028; PMCID: PMC6464773. [CrossRef]

- Almaleh, A. A Novel Deep Learning Approach for Real-Time Critical Assessment in Smart Urban Infrastructure Systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 3286. [CrossRef]

- Zgłoszenie do Urzędu Patentowego Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej dnia 2022-09-27 pt. „Urządzenie do ćwiczenia kierowców” nr. P.442373 autorstwa Jacka S. Tutaka, Krzysztofa Lwa, Andrzeja Burghardta, Michała Jurka oraz Piotra Matłosza.

- J. Wirkner et al., “Mental Health in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Current Knowledge and Implications From a European Perspective,” European Psychologist, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 310–322, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cinar, O.E.; Rafferty, K.; Cutting, D.; Wang, H. AI-Powered VR for Enhanced Learning Compared to Traditional Methods. Electronics 2024, 13, 4787. [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Kwon, S.; Myeong, S. Enhancing Software Code Vulnerability Detection Using GPT-4o and Claude-3.5 Sonnet: A Study on Prompt Engineering Techniques. Electronics 2024, 13, 2657. [CrossRef]

- Budzik G., Turek P., Traciak J.: The influence of change in slice thickness on the accuracy of reconstruction of cranium geometry, Proc IMechE, Part H: J Engineering in Medicine, 231(3), s. 197-202, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Turek P.: Automating the process of designing and manufacturing polymeric models of anatomical structures of mandible with Industry 4.0 convention, Polimery, 64(7-8), s. 522-529, 2019. DOI:dx.doi.org/10.14314/polimery.2019.7.9.

- Shin, H.; Park, W.; Kim, S.; Kweon, J.; Moon, C. Driver Identification System Based on a Machine Learning Operations Platform Using Controller Area Network Data. Electronics 2025, 14, 1138. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, G.; Sun, C.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Tian, L.; Li, F. Multi-Environment Vehicle Trajectory Automatic Driving Scene Generation Method Based on Simulation and Real Vehicle Testing. Electronics 2025, 14, 1000. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Lian, X.; Shen, H. Efficient Spiking Neural Network for RGB–Event Fusion-Based Object Detection. Electronics 2025, 14, 1105. [CrossRef]

- Trzmiel T., Marchewka R., Pieczyńska A., Zasadzka E., Zubrycki I., Kozak D., Mikulski M., Poświata A., Tobis S., Hojan K. The Effect of Using a Rehabilitation Robot for Patients with Post-Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Fatigue Syndrome. Sensors 2023, 23(19), 8120. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Driver Training Device with Its Key Components: 1 - base, 2 - body, 3 - steering wheel, 4 - recess, 5 - first guide rail, 6 - panel, 7 - first button, 8 - RGB LED diode, 9 - slider, 10 - second guide rail, 11 - protrusions, 12 - encoder, 13 - groove, 14 - casing, 15 - central display, 16 - distance sensor, 17 - handle, 18 - camera, 19 - speaker, 20 - first arm, 21 - second arm, 22 - second handle, 23 - frame, 24 - side display, 25 - third handle, 26 - panel, 27 - rotary knob, 28 - diode, 29 - second button.

Figure 1.

Driver Training Device with Its Key Components: 1 - base, 2 - body, 3 - steering wheel, 4 - recess, 5 - first guide rail, 6 - panel, 7 - first button, 8 - RGB LED diode, 9 - slider, 10 - second guide rail, 11 - protrusions, 12 - encoder, 13 - groove, 14 - casing, 15 - central display, 16 - distance sensor, 17 - handle, 18 - camera, 19 - speaker, 20 - first arm, 21 - second arm, 22 - second handle, 23 - frame, 24 - side display, 25 - third handle, 26 - panel, 27 - rotary knob, 28 - diode, 29 - second button.

Figure 2.

CAD Models of the Driver Training Device.

Figure 2.

CAD Models of the Driver Training Device.

Figure 3.

Prototype of the Driver Training Device.

Figure 3.

Prototype of the Driver Training Device.

Figure 4.

Block Diagram of the Driver Training Device: A – Exercise Module System, B – Power Supply System, C – Control System.

Figure 4.

Block Diagram of the Driver Training Device: A – Exercise Module System, B – Power Supply System, C – Control System.

Figure 5.

Driver Exercise Device User Interface: (a) Information Window; (b) Diagnostics_1 Window; (c) Diagnostics_2 Window; (d) Exercise Window.

Figure 5.

Driver Exercise Device User Interface: (a) Information Window; (b) Diagnostics_1 Window; (c) Diagnostics_2 Window; (d) Exercise Window.

Figure 6.

Results from Diagnostic Module – 1.

Figure 6.

Results from Diagnostic Module – 1.

Figure 7.

Results from Exercise Module – 1 "Easy" Level.

Figure 7.

Results from Exercise Module – 1 "Easy" Level.

Figure 8.

Results from Exercise Module – 2 "Medium" Level.

Figure 8.

Results from Exercise Module – 2 "Medium" Level.

Figure 9.

Results from Exercise Module – 3 "Difficult" Level.

Figure 9.

Results from Exercise Module – 3 "Difficult" Level.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).