Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

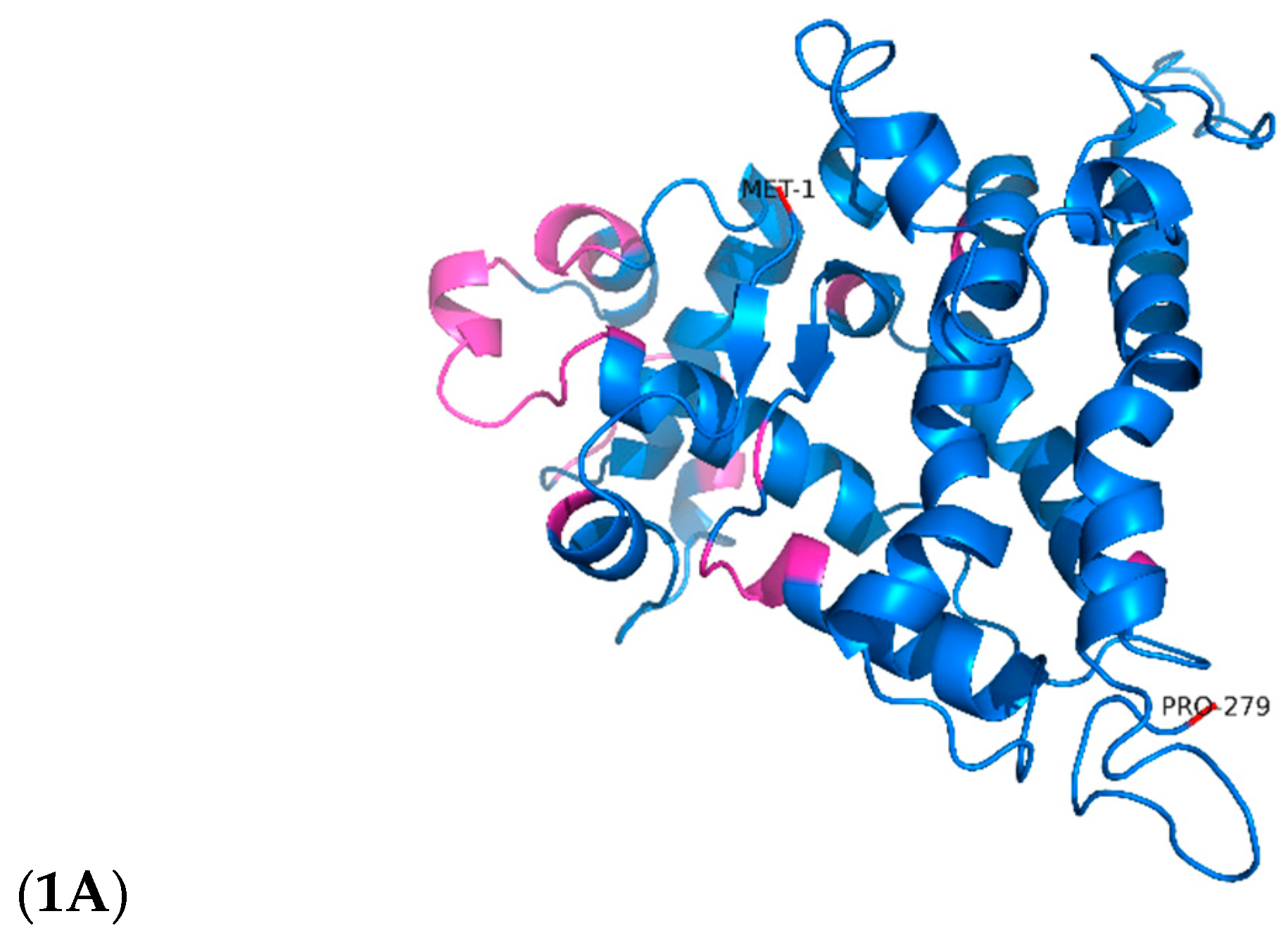

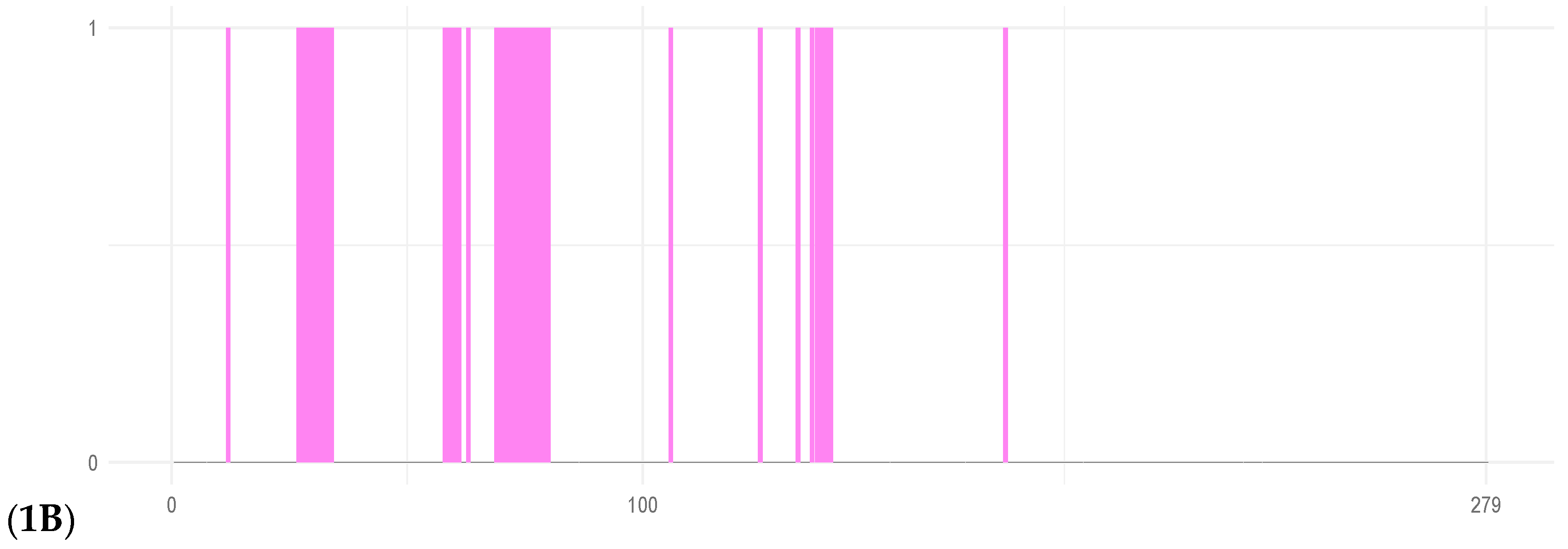

2.1. Structural Characterisation and Refinement of TetR Transcription Factors in the Actinomycin D Biosynthetic Cluster of Streptomyces fildesensis

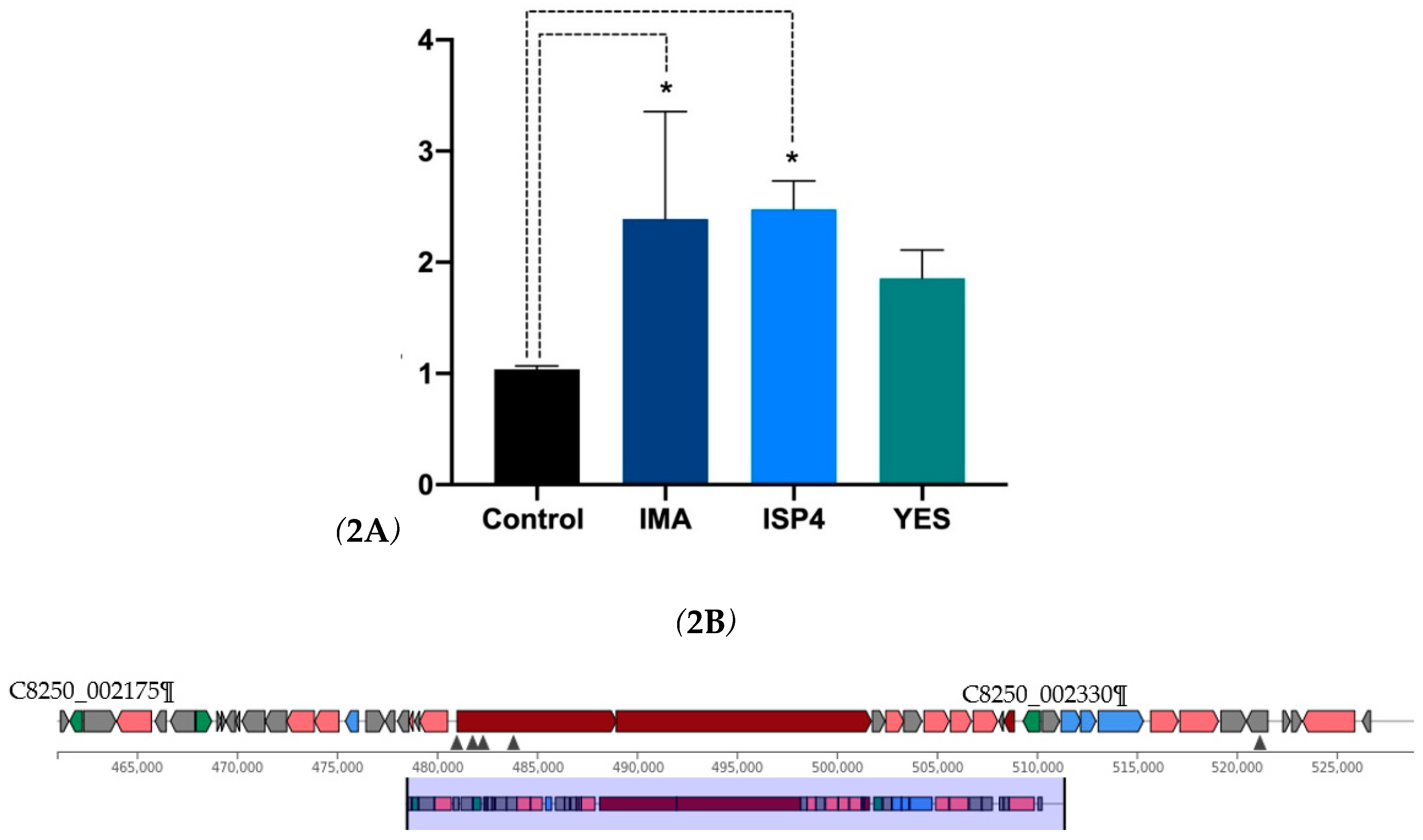

2.2. Nutrient-Dependent Regulation of TetR-279 Expression in the Actinomycin D Gene Cluster

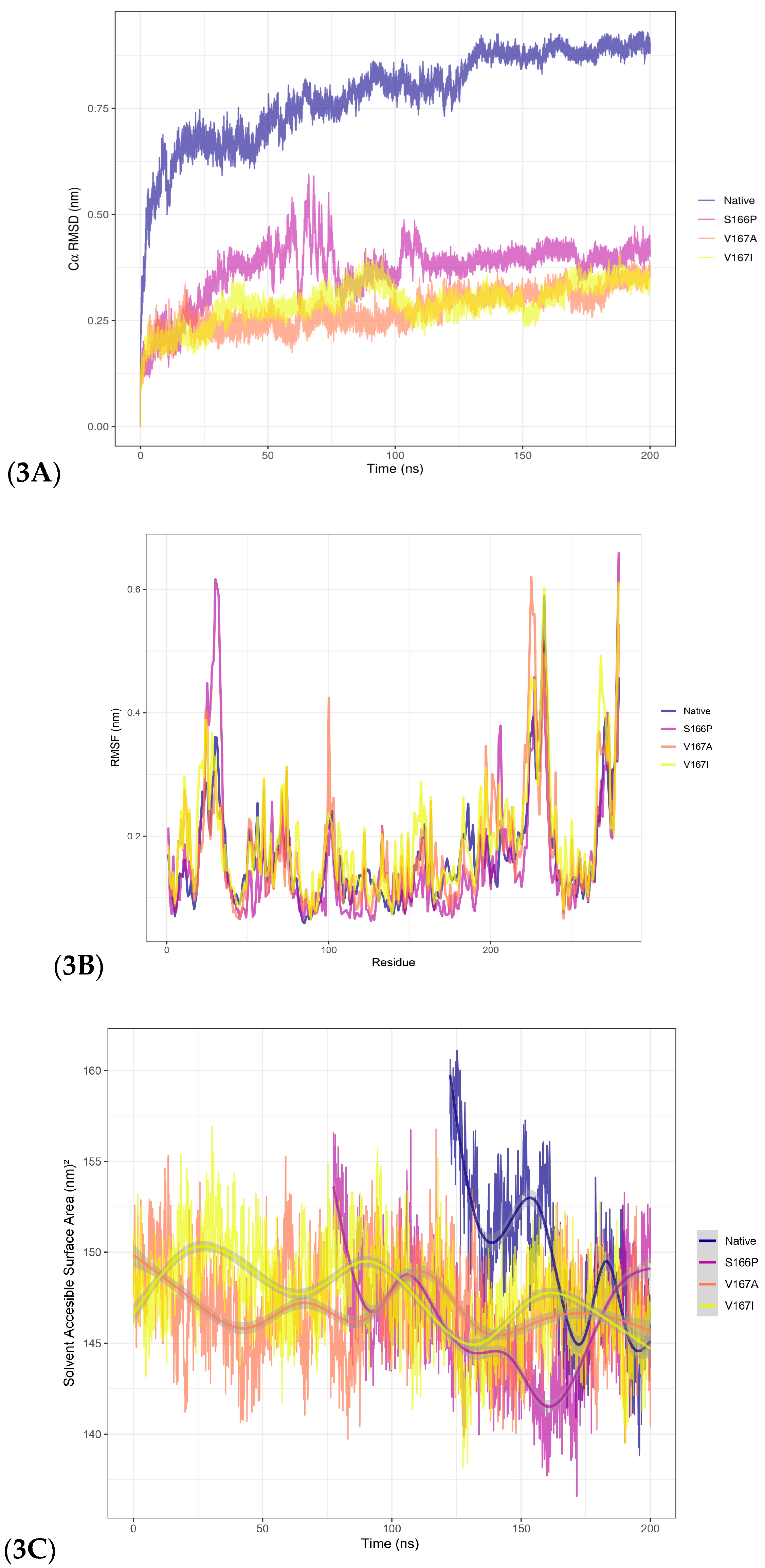

2.3. Structural Effects of Point Mutations in TetR-279 via Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification and Structural Analysis of the Protein

4.2. Cultivation Conditions of Streptomyces fildesensis So13.3

4.3. Gene Expression Analysis of TetR-279 Under Different Nutritional Conditions

4.5. Homology Modeling, Refinement, and Molecular Dynamics Simulations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BGC: | Biosynthetic Gene Clusters |

| CRISPR: | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| MD: | Molecular Dynamics |

| RMSD: | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| RMSF: | Root Mean Square Fluctuation |

| SASA: | Solvent Accessible Surface Area |

| TF: | Transcription Factor |

| ISP4: | International Streptomyces Project Medium 4 |

| YES: | Yeast Extract Sucrose Medium |

| HTH: | Helix-Turn-Helix |

| SNP: | Sodium Nitroprusside |

| LPS: | Lipopolysaccharide |

| qPCR: | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PDB: | Protein Data Bank |

| pLDDT: | Predicted Local Distance Difference Test |

| VMD: | Visual Molecular Dynamics |

| PBC: | Periodic Boundary Conditions |

| PME: | Particle Mesh Ewald |

| NVT: | Constant Number, Volume, Temperature Ensemble |

| NPT: | Constant Number, Pressure, Temperature Ensemble |

| LINCS: | Linear Constraint Solver |

| EMSA: | Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay |

| DSB: | Double-Strand Break |

| NRPS: | Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetase |

| CRISPR-BEST: | CRISPR Base Editing SysTem |

| EXPosition: | EXpression Prediction from Sequence Mutations |

References

- Govindaraj Vaithinathan and A. Vanitha, "WHO global priority pathogens list on antibiotic resistance: an urgent need for action to integrate One Health data," Perspect Public Health, vol. 138, no. 2, pp. 87–88, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. T. Nisa, D. Nakatani, F. Kaneko, T. Takeda, and K. Nakata, "Antimicrobial resistance patterns of WHO priority pathogens isolated in shospitalised patients in Japan: A tertiary center observational study," PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 1 January, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Choudhury, A. Medina-Lara, and R. Smith, "Antimicrobial resistance and the COVID-19 pandemic," Bull World Health Organ, vol. 100, no. 5, pp. 295–295, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Núñez-Montero and L. Barrientos, "Advances in Antarctic Research for Antimicrobial Discovery: A Comprehensive Narrative Review of Bacteria from Antarctic Environments as Potential Sources of Novel Antibiotic Compounds Against Human Pathogens and Microorganisms of Industrial Importance," Antibiotics 2018, Vol. 7, Page 90, vol. 7, no. 4, p. 90, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. P. Thompson and B. F. Gilmore, "Exploring halophilic environments as a source of new antibiotics," Crit Rev Microbiol, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 341–370, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Lugg and C. R. Roy, "Ultraviolet radiation and health effects in the Antarctic," Polar Res, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 353–359, Jan. 1999. [CrossRef]

- D. Coppola et al., "Biodiversity of UV-Resistant Bacteria in Antarctic Aquatic Environments," J Mar Sci Eng, vol. 11, no. 5, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Silva et al., "Actinobacteria from Antarctica as a source for anticancer discovery," Sci Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Benaud et al., "Antarctic desert soil bacteria exhibit high novel natural product potential, evaluated through long-read genome sequencing and comparative genomics.," Environ Microbiol, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 3646–3664, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Russell, R. Lacret, and A. Truman, "Genome-led discovery of novel microbial natural products," Access Microbiol, vol. 1, no. 1A, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Lebedeva, G. Jukneviciute, R. Čepaitė, V. Vickackaite, R. Pranckutė, and N. Kuisiene, "Genome Mining and Characterization of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Two Cave Strains of Paenibacillus sp.," Front Microbiol, vol. 11, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Mao, B. K. Okada, Y. Wu, F. Xu, and M. R. Seyedsayamdost, "Recent advances in activating silent biosynthetic gene clusters in bacteria.," Curr Opin Microbiol, vol. 45, pp. 156–163, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Montiel, H. S. Kang, F. Y. Chang, Z. Charlop-Powers, and S. F. Brady, "Yeast homologous recombination-based promoter engineering for the activation of silent natural product biosynthetic gene clusters," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 112, no. 29, pp. 8953–8958, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Núñez-Montero et al., "Antarctic Streptomyces fildesensis So13.3 strain as a promising source for antimicrobials discovery," Scientific Reports 2019 9:1, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–13, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Núñez-Montero, D. Quezada-Solís, Z. G. Khalil, R. J. Capon, F. D. Andreote, and L. Barrientos, "Genomic and Metabolomic Analysis of Antarctic Bacteria Revealed Culture and Elicitation Conditions for the Production of Antimicrobial Compounds," Biomolecules, vol. 10, no. 5, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lin et al., “Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals Anti-Staphylococcus aureus Activity of Actinomycin D Originating from Streptomyces parvulus,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 22, no. 22, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu et al., “Identification of the Actinomycin D Biosynthetic Pathway from Marine-Derived Streptomyces costaricanus SCSIO ZS0073,” Mar Drugs, vol. 17, no. 4, 2019. [CrossRef]

- W. Deng, C. Li, and J. Xie, "The underling mechanism of bacterial TetR/AcrR family transcriptional repressors.," Cell Signal, vol. 25 7, no. 7, pp. 1608–13, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Filipek et al., "Comprehensive structural overview of the C-terminal ligand-binding domains of the TetR family regulators.," J Struct Biol, vol. 216, no. 2, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Krushkal, S. Sontineni, C. Leang, Y. Qu, R. M. Adkins, and D. R. Lovley, "Genome diversity of the TetR family of transcriptional regulators in a metal-reducing bacterial family Geobacteraceae and other microbial species.," OMICS, vol. 15 7–8, no. 7–8, pp. 495–506, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Cuthbertson and J. R. Nodwell, "The TetR Family of Regulators," Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, vol. 77, no. 3, pp. 440–475, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu et al., "AveI, an AtrA homolog of Streptomyces avermitilis, controls avermectin and oligomycin production, melanogenesis, and morphological differentiation," Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 103, no. 20, pp. 8459–8472, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Xu, P. Waack, Q. Zhang, S. Werten, W. Hinrichs, and M. J. Virolle, "Structure and regulatory targets of SCO3201, a highly promiscuous TetR-like regulator of Streptomyces coelicolor M145.," Biochem Biophys Res Commun, vol. 450 1, no. 1, pp. 513–8, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Núñez-Montero et al., "Antarctic Streptomyces fildesensis So13.3 strain as a promising source for antimicrobials discovery," Scientific Reports 2019 9:1, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–13, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tong, C. M. Whitford, K. Blin, T. S. Jørgensen, T. Weber, and S. Y. Lee, "CRISPR–Cas9, CRISPRi and CRISPR-BEST-mediated genetic manipulation in streptomycetes," Nature Protocols 2020 15:8, vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 2470–2502, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- U. Keller, M. Lang, I. Crnovcic, F. Pfennig, and F. Schauwecker, "The Actinomycin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster of Streptomyces chrysomallus: a Genetic Hall of Mirrors for Synthesis of a Molecule with Mirror Symmetry," J Bacteriol, vol. 192, no. 10, pp. 2583–2595, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- Crnovčić, C. Rückert, S. Semsary, M. Lang, J. Kalinowski, and U. Keller, "Genetic interrelations in the actinomycin biosynthetic gene clusters of <em>Streptomyces antibioticus</em> IMRU 3720 and <em>Streptomyces chrysomallus</em> ATCC11523, producers of actinomycin X and actinomycin C," Advances and Applications in Bioinformatics and Chemistry, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 29–46, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu et al., “Identification of the Actinomycin D Biosynthetic Pathway from Marine-Derived Streptomyces costaricanus SCSIO ZS0073,” Mar Drugs, vol. 17, no. 4, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Govindarajan et al., “Genome Sequencing of Streptomyces griseus SCSIO PteL053, the Producer of 2,2′-Bipyridine and Actinomycin Analogs, and Associated Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Analysis,” J Mar Sci Eng, vol. 11, no. 2, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- U. Keller, M. Lang, I. Crnovcic, F. Pfennig, and F. Schauwecker, "The Actinomycin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster of Streptomyces chrysomallus: a Genetic Hall of Mirrors for Synthesis of a Molecule with Mirror Symmetry," J Bacteriol, vol. 192, no. 10, pp. 2583–2595, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Montero, D. Quezada-Solís, Z. G. Khalil, R. J. Capon, F. D. Andreote, and L. Barrientos, "Genomic and Metabolomic Analysis of Antarctic Bacteria Revealed Culture and Elicitation Conditions for the Production of Antimicrobial Compounds," Biomolecules 2020, Vol. 10, Page 673, vol. 10, no. 5, p. 673, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ke et al., "CRAGE-CRISPR facilitates rapid activation of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters in bacteria.," Cell Chem Biol, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 696-710.e4, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ameruoso, M. C. V. Kcam, K. P. Cohen, and J. Chappell, "Activating natural product synthesis using CRISPR interference and activation systems in Streptomyces," Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 50, no. 13, pp. 7751–7760, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liang et al., "ActO, a positive cluster-situated regulator for actinomycins biosynthesis in Streptomyces antibioticus ZS.," Gene, vol. 933, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lei, S. Asamizu, T. Ishizuka, and H. Onaka, “Regulation of Multidrug Efflux Pumps by TetR Family Transcriptional Repressor Negatively Affects Secondary Metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2),” Appl Environ Microbiol, vol. 89, no. 3, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu et al., "TetR family regulator AbrT controls lincomycin production and morphological development in Streptomyces lincolnensis," Microb Cell Fact, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Inahashi et al., "Identification and heterologous expression of the actinoallolide biosynthetic gene cluster," J Antibiot (Tokyo), vol. 71, no. 8, pp. 749–752, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Yu, H. Lin, A. Bechthold, X. Yu, and Z. Ma, "RS24090, a TetR family transcriptional repressor, negatively affects the rimocidin biosynthesis in Streptomyces rimosus M527.," Int J Biol Macromol, vol. 285, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Naeem and O. S. Alkhnbashi, "Current Bioinformatics Tools to Optimise CRISPR/Cas9 Experiments to Reduce Off-Target Effects," Int J Mol Sci, vol. 24, no. 7, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tong et al., "Highly efficient DSB-free base editing for streptomycetes with CRISPR-BEST," Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 116, no. 41, pp. 20366–20375, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M.-S. Liu, S. Gong, H. Yu, K. Jung, K. Johnson, and D. W. Taylor, "Basis for discrimination by engineered CRISPR/Cas9 enzymes," bioRxiv, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Cohen, S. Bergman, N. Lynn, and T. Tuller, "A tool for CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA evaluation based on computational models of gene expression," bioRxiv, p. 2024.06.08.598047, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Yuan, "Mitigating the Off-target Effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Genetic Editing with Bioinformatic Technologies," Transactions on Materials, Biotechnology and Life Sciences, vol. 3, pp. 318–326, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Hwang et al., "Primary transcriptome and translatome analysis determines transcriptional and translational regulatory elements encoded in the Streptomyces clavuligerus genome," Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 47, no. 12, pp. 6114–6129, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. A. Hussein and A. A. Al-Kazaz, "BIOINFORMATICS EVALUATION OF CRISP2 GENE SNPs AND THEIR IMPACTS ON PROTEIN," IRAQI JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 369–377, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Chellapandi, "Structural-functional integrity of hypothetical proteins identical to ADPribosylation superfamily upon point mutations.," Protein Pept Lett, vol. 21 8, no. 8, pp. 722–35, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. E. V. Pires, J. Chen, T. L. Blundell, and D. B. Ascher, "In silico functional dissection of saturation mutagenesis: Interpreting the relationship between phenotypes and changes in protein stability, interactions and activity," Sci Rep, vol. 6, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Yu, Y. Zhao, C. Guo, Y. Gan, and H. Huang, "The role of proline substitutions within flexible regions on thermostability of luciferase.," Biochim Biophys Acta, vol. 1854 1, no. 1, pp. 65–72, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Atsavapranee, F. Sunden, D. Herschlag, and P. M. Fordyce, "Quantifying protein unfolding kinetics with a high-throughput microfluidic platform," Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Kellis, K. Nyberg, and A. R. Fersht, "Energetics of complementary side-chain packing in a protein hydrophobic core.," Biochemistry, vol. 28 11, no. 11, pp. 4914–22, 1989. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Berman et al., "The Protein Data Bank," Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 235–242, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- J. Jumper et al., "Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold," Nature 2021 596:7873, vol. 596, no. 7873, pp. 583–589, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Almagro Armenteros et al., "SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks," Nature Biotechnology 2019 37:4, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 420–423, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Núñez-Montero, D. Rojas-Villalta, R. Hernández-Moncada, A. Esquivel, and L. Barrientos, “Genome Sequence of Pseudomonas sp. Strain So3.2b, Isolated from a Soil Sample from Robert Island (Antarctic Specially Protected Area 112), Antarctic," Microbiol Resour Announc, vol. 12, no. 3, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Livak and T. D. Schmittgen, "Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method," Methods, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 402–408, Dec. 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. Lin, Z. Zou, C. Zhou, H. Zhang, and Z. Cai, "Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Adenosine Biosynthesis in Anamorph Strain of Caterpillar Fungus," Biomed Res Int, vol. 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Blin, L. E. Pedersen, T. Weber, and S. Y. Lee, "CRISPy-web: An online resource to design sgRNAs for CRISPR applications," Synth Syst Biotechnol, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 118–121, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Blin et al., "antiSMASH 5.0: updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline," Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 47, no. W1, pp. W81–W87, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Afgan et al., "The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2018 update," Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 46, no. W1, pp. W537–W544, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. J. C. Berendsen, D. van der Spoel, and R. van Drunen, "GROMACS: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation," Comput Phys Commun, vol. 91, no. 1–3, pp. 43–56, Sep. 1995. [CrossRef]

- W. Humphrey, A. Dalke, and K. Schulten, "VMD: Visual molecular dynamics," J Mol Graph, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 33–38, Feb. 1996. [CrossRef]

- H. Wickham, "ggplot2," 2016. [CrossRef]

| Locus tag | Product | Length | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT | AA | |||

| C8250_002175 | TetR/AcrR family transcriptional regulator | 621 | 206 | Regulatory |

| C8250_002330 | TetR/AcrR family transcriptional regulator | 840 | 279 | Regulatory |

| Medium | Components (per litre) |

|---|---|

| IMA | Yeast extract (4 g), Malt extract (10 g), Glucose (4 g), Mannitol (40g) |

| YES | Sucrose (150 g), Yeast extract (20 g), MgSO₄·7H₂O (0.5 g), ZnSO₄·7H₂O (0.01 g), CuSO₄·5H₂O (0.005 g) |

| ISP-4 | Starch (10 g), CaCO₃ (2 g), (NH₄) ₂SO₄ (2 g), K₂HPO₄ (1 g), MgSO₄·7H₂O (1 g), NaCl (1 g), FeSO₄·7H₂O (1 mg), MnCl₂·7H₂O (1 mg), ZnSO₄·7H₂O (1 mg) |

| M2 | Mannitol (40 g), Maltose (40 g), Yeast extract (10 g), K₂HPO₄ (2 g), MgSO₄·7H₂O (0.5 g), FeSO₄·7H₂O (0.01 g) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).