Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Unveiling Endogenous Quinolines in the Kynurenine (KYN) Pathway: A Gateway to Kynurenic Acid (KYNA)–Driven Neuroprotection and Rational Drug Design

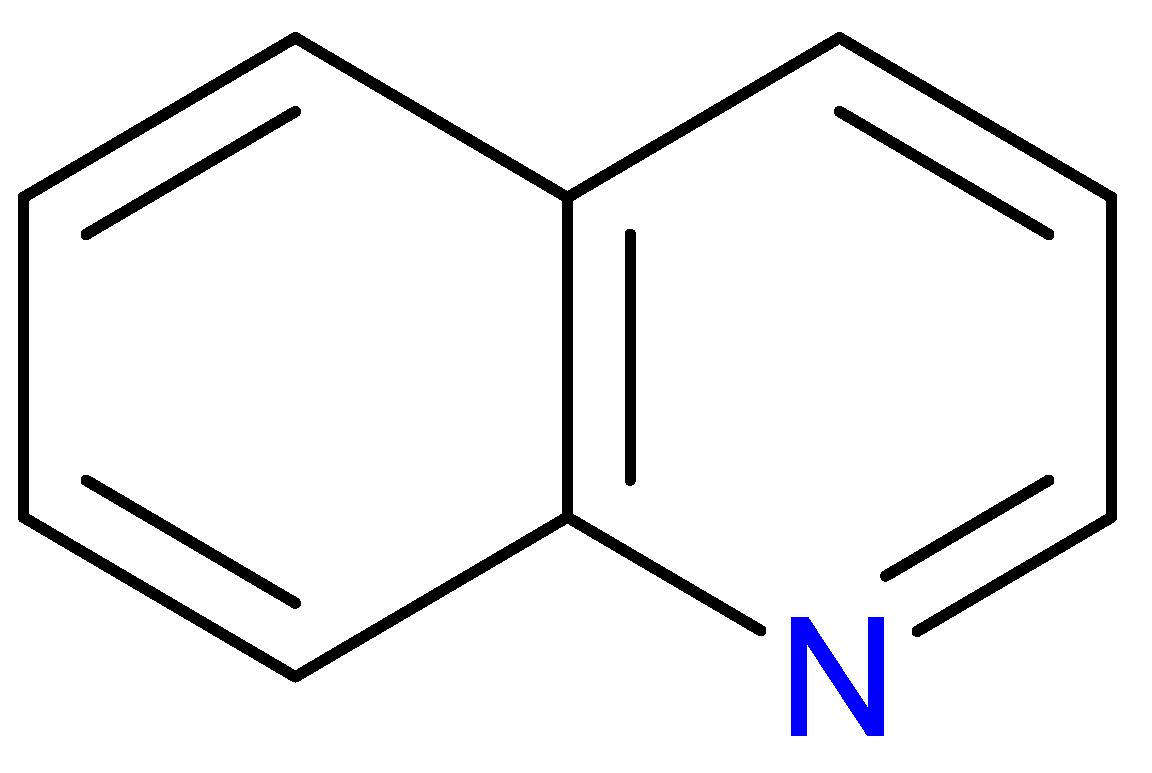

2.1. Structural & Functional Synergy

2.2. Key Gaps in Translation

3. Expanding the Quinoline Landscape: Derivatives Beyond the Kynurenine (KYN) Metabolic Pathway

| Compounds | Main characteristics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Quinoline and quinolone derivatives | ||

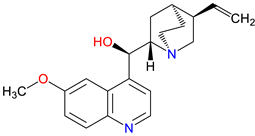

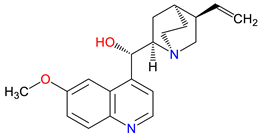

Quinine  Quinidine |

Quinine: Antimalarial agent – Inhibits Plasmodium pp. by interfering with heme detoxification Historically used to reduce fever and pain Muscle relaxant – Helps alleviate nocturnal leg cramps by modulating ion channels Quinidine: Class I antiarrhythmic – Blocks sodium channels, stabilizing cardiac rhythm Chiral isomer of quinine – Shares structural similarities but has distinct pharmacological effects Proarrhythmic risk – Can prolong QT interval 1, requiring careful clinical use |

[134,135,136] [137,138,139] [140,141] [142,143,144] [145,146,147] [148,149,150] |

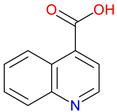

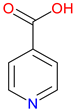

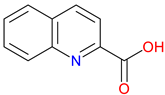

Cinchoninic Acid |

Quinoline derivative – Structurally related to quinine and other cinchona alkaloids Metal chelation – Binds with metal ions, potentially influencing enzymatic activity Pharmacological potential – Investigated for antimicrobial and neuroactive properties |

[141,151,152] [153,154] [155,156,157] |

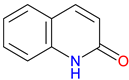

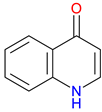

2-Quinolinone  4-Quinolinone |

Core scaffold for quinolone antibiotics – Forms the backbone of fluoroquinolones, targeting bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV Broad-spectrum antimicrobial Activity – Effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria Synthetic Versatility – Modifiable structure allows for improved potency, pharmacokinetics, and resistance mitigation. |

[158,159,160] [161,162,163] [162,164,165] |

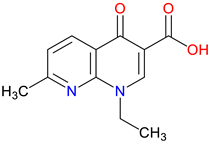

Nalidixic Acid |

First-generation quinolone antibiotic – Inhibits DNA gyrase, primarily effective against Gram-negative bacteria Limited spectrum & rapid resistance – Narrow activity and high bacterial resistance limit its clinical use Urinary tract infection treatment – Historically used for urinary tract infections, though largely replaced by newer fluoroquinolones |

[166,167,168] [169,170] [171,172,173] |

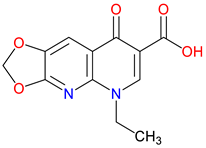

Oxolinic Acid |

Early quinolone antibiotic – Inhibits DNA gyrase, effective against Gram-negative bacteria Used in veterinary medicine – Primarily employed for treating bacterial infections in animals Limited clinical use – Replaced by newer fluoroquinolones due to resistance and pharmacokinetic limitations |

[174,175,176] [177,178,179] [180] |

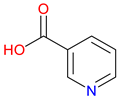

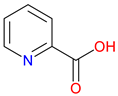

| Pyridinecarboxylic Acids | ||

Isonicotinic Acid (INA) |

Pyridine carboxylic acid derivative – Structurally related to NA (vitamin B3). Key precursor for isoniazid – Used in the synthesis of isoniazid, a frontline anti-tuberculosis drug. Pharmacological Potential – Investigated for antimicrobial and metabolic regulatory properties |

[181,182] [183,184] [183,185,186] |

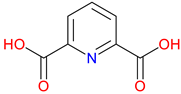

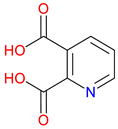

Dipicolinic Acid (DPA) |

Metal ion chelator – Strongly binds calcium and other metal ions, playing a role in metal homeostasis Bacterial spore component – Essential for bacterial endospore resistance and heat stability Potential neuroprotective role – Explored for its effects on metal-related oxidative stress in neurodegeneration |

[187,188] [189] [190,191,192] |

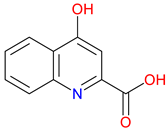

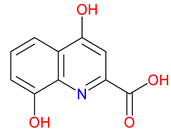

| Hydroxy-Substituted Derivatives | ||

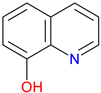

8-Hydroxyquinoline |

Metal clator – Strongly binds iron, copper, and zinc, influencing redox balance and enzymatic activity Antimicrobial and antifungal agent – Exhibits broad-spectrum activity against bacteria and fungi Potential neuroprotective role – Investigated for treating neurodegenerative diseases by regulating metal toxicity |

[193,194,195] [196,197,198] [199,200,201] |

3.1. Repurposing Potential

3.2. Bridging to Kynurenic acid (KYNA)-Based Targets

3.3. Innovative Directions

4. Exogenous Horizons: Synthetic Quinoline Scaffolds in Rational Drug Design

| Compounds | Main characteristics | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

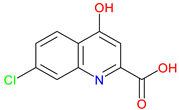

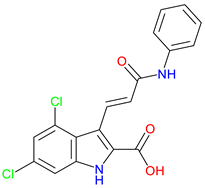

7-Chlorokynurenic Acid (7-CKA) |

NMDA receptor antagonist – Blocks the glycine-binding site, reducing excitotoxicity. Preclinical behavioral actions – Elicits antidepressant-like effects, blocks NMDA-induced convulsions, and attenuates ischemia-induced learning deficits Clinical trials – 4-Clorokynurenin, a prodrug of 7-CKA show no significant antidepressant effects in treatment-resistant depression and launched a clinical trial for neuropathic pain |

[245,246] [247,248,249] [250] |

|

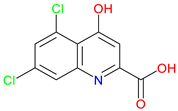

5,7-Dichlorokynurenic Acid |

NMDA receptor antagonist – Blocks the glycine site to reduce excitotoxicity Enhanced potency – More effective than KYNA at inhibiting NMDA receptor activity Preclinical behavioral actions – Show anxiolytic effects and enhance short-term memory and recognition |

[251,252,253] [238,251,253,254] [255,256,257] |

|

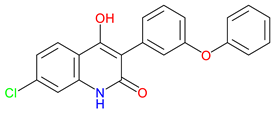

L-701,324 |

NMDA receptor antagonist – Blocks the glycine site, reducing excitotoxicity Preclinical behavioral evidence – Demonstrates antidepressant-like activity, Reduce anxiety-like behavior Potential clinical application –Epilepsy, schizophrenia, and chronic pain |

[258,259] [257,260] [261,262,263] |

|

Gavestinel |

Glycine site NMDA receptor antagonist – Blocks NMDA receptor activity to reduce excitotoxicity Preclinical behavioral findings – potential in reducing ischemic damage and modulating certain NMDA receptor-mediated schizophrenia-like behaviors Stroke neuroprotection Candidate – Investigated for acute stroke, primary intracerebral hemorrhage, acute ischemic stroke, but failed in clinical trials. |

[264,265] [264,266] [264,267,268] |

|

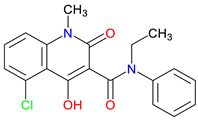

Laquinimod |

Immunomodulatory agent – Reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines and modulates immune cell activity Preclinical findings – Improve motor function in a Huntington's disease model, activate the AhR in the EAE Model of MS Clinical trials – Modestly reduce relapse rates and disability progression and significantly reduce brain volume change atrophy in relapsing-remitting MS, and show limited efficacy in active non-infectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis (NCT02720102) |

[269,270,271] [272,273] [274,275,276] |

|

Tasquinimod |

Anti-cancer properties – Inhibits tumor angiogenesis, suppresses myeloid-derived suppressor cells, downregulate immune suppressive pathways and inflammatory cytokine signaling S100A9 modulation – Suppress inflammatory factor expression, potentially inhibit the upregulation of S100A9 in AD, and inhibit MDSC recruitment HDAC4 Modulation – potentially influence epigenetic regulation in neurodegenerative or cognitive disorders and potentially control neuronal memory, plasticity, and learning |

[277,278,279] [280,281,282] [283,284] |

4.1. Rational Design Successes and Failure

4.2. Mechanistic Trade-Offs

5. Next-Generation Kynurenic Acid (KYNA) Analogues: The SZR Series

| Compounds | Main characteristics | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

SZR-72 |

BBB penetration – effectively crosses the blood–brain barrier, enhancing its therapeutic potential in the CNS Neuroprotective effect – Offers enhanced neuroprotection, reduces brainstem c-fos, and induces therapeutic hypothermia Behavioral effects – Alters motor and exploratory behaviors, reducing vertical activity and affecting curiosity-linked emotional and motor responses |

[334,335] [333,334] [335] |

|

SZR-73 |

Mitochondrial function enhancement – Enhances mitochondrial respiration and ATP production, improving complex I- and II-linked OXPHOS in a rodent sepsis model Systemic inflammatory activation reduction – Reduces systemic inflammation in sepsis, lowering ET-1, IL-6, NT levels, and XOR activity Microcirculatory Effects – Improves mitochondrial function but does not restore microcirculation, unlike KYNA, which improves microvascular perfusion in sepsis |

[221] [221] [221] |

|

SZR-81 |

Antidepressant-like effects – Reduces immobility and increasing swimming in FST via serotonin 5-HT system involvement BBB permeability – Poor BBB penetration or metabolic alteration before reaching the CNS Neuroprotective potential– To be explored for use in stroke, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammatory conditions |

[339] [339] [340] |

|

SZR-104 |

High permeability through the blood – Shows high BBB permeability, surpassing KYNA and analogues Neuroprotective effects in sepsis – Demonstrates neuroprotection in septic rodents, reducing BBB disruption and CNS mitochondrial dysfunction Influence on motor behavior – Increases horizontal exploration, indicating BBB penetration and retention of KYNA-like effects on motor-related curiosity and emotional behavior |

[49] [336] [335] |

|

SZR-105 |

High BBB penetrability – Significantly better BBB permeability than KYNA and earlier analogues due to its dual cationic side chains Potent anti-inflammatory effects – Suppresses TNF-α production and strongly induces TSG-6 Neuroprotective activity in CNS models – Reduces cortical spreading depression propagation in migraine models |

[49] [337] [338] |

|

SZR-109 |

Enhanced BBB penetration – penetrate the BBB more effectively than KYNA Neuroprotective effects –Suppresses pro-inflammatory TNF-α production and upregulates TSG-6 Anti-convulsant activity – prevents or diminishes seizure-like activity in the brain |

[49] [337] [338] |

|

SZRG-21 |

BBB penetration – Demonstrated efficacy in reducing cytokine levels in colitis models Impact on motor activity – Alter motor activity and exploratory behavior Emotional and behavioral modulation – Affect emotional functions such as motor-associated curiosity and emotions |

[335] [335] [335] |

5.1. SAR-Driven Innovations

5.2. Translational Barriers

5.3. Path to Lead Optimization

3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| 7-CKA | 7-chlorokynurenic acid |

| DPA | dipicolinic acid |

| GPR35 | G protein-coupled receptor 35 |

| HDAC | histone deacetylase |

| IDOs | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenases |

| INA | isonicotinic acid |

| KYN | kynurenine |

| KYNA | kynurenic acid |

| NA | nicotinic acid |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| QUIN | quinolinic acid |

| SAR | structure–activity relationship |

| Trp | tryptophan |

| TDO | tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase |

| XA | xanthurenic acid |

References

- Stone, T.W.; Williams, R.O. Tryptophan metabolism as a ‘reflex’feature of neuroimmune communication: sensor and effector functions for the indoleamine-2, 3-dioxygenase kynurenine pathway. Journal of Neurochemistry 2024, 168, 3333–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelace, M.D.; Varney, B.; Sundaram, G.; Lennon, M.J.; Lim, C.K.; Jacobs, K.; Guillemin, G.J.; Brew, B.J. Recent evidence for an expanded role of the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism in neurological diseases. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervenka, I.; Agudelo, L.Z.; Ruas, J.L. Kynurenines: Tryptophan’s metabolites in exercise, inflammation, and mental health. Science 2017, 357, eaaf9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.; Zadeh, K.; Vekariya, R.; Ge, Y.; Mohamadzadeh, M. Tryptophan metabolism and gut-brain homeostasis. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Yu, S.; Long, Y.; Shi, A.; Deng, J.; Ma, Y.; Wen, J.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. Tryptophan metabolism: Mechanism-oriented therapy for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 985378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, A.A. Kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism: regulatory and functional aspects. International journal of tryptophan research 2017, 10, 1178646917691938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, D.; Song, P.; Zou, M.-H. Deregulated tryptophan-kynurenine pathway is linked to inflammation, oxidative stress, and immune activation pathway in cardiovascular diseases. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition) 2015, 20, 1116. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Redefining roles: A paradigm shift in tryptophan–kynurenine metabolism for innovative clinical applications. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25, 12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-Q.; Li, X.; Guo, H.-Y.; Shen, Q.-K.; Quan, Z.-S.; Luan, T. Application of quinoline ring in structural modification of natural products. Molecules 2023, 28, 6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, O.O.; Iyaye, K.T.; Ademosun, O.T. Recent advances in chemistry and therapeutic potential of functionalized quinoline motifs–a review. RSC advances 2022, 12, 18594–18614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehlangia, S.; Nayak, N.; Garg, N.; Pradeep, C.P. Substituent-controlled structural, supramolecular, and cytotoxic properties of a series of 2-Styryl-8-nitro and 2-Styryl-8-hydroxy quinolines. ACS omega 2022, 7, 24838–24850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Ayala, L.F.; Guzmán-López, E.G.; Galano, A. Quinoline Derivatives: Promising Antioxidants with Neuroprotective Potential. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorana, A.; La Monica, G.; Lauria, A. Quinoline-based molecules targeting c-Met, EGF, and VEGF receptors and the proteins involved in related carcinogenic pathways. Molecules 2020, 25, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, T.; Takeuchi, M.; Uda, M.; Ariga, Y.; Yamazaki, A.; Sekiguchi, R.; Ito, S. Synthesis of Azuleno [2, 1-b] quinolones and Quinolines via Brønsted Acid-Catalyzed Cyclization of 2-Arylaminoazulenes. Molecules 2023, 28, 5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V.; Reang, J.; Sharma, V.; Majeed, J.; Sharma, P.C.; Sharma, K.; Giri, N.; Kumar, A.; Tonk, R.K. Quinoline-derivatives as privileged scaffolds for medicinal and pharmaceutical chemists: A comprehensive review. Chemical Biology & Drug Design 2022, 100, 389–418. [Google Scholar]

- Lanz, T.V.; Williams, S.K.; Stojic, A.; Iwantscheff, S.; Sonner, J.K.; Grabitz, C.; Becker, S.; Böhler, L.-I.; Mohapatra, S.R.; Sahm, F. Tryptophan-2, 3-Dioxygenase (TDO) deficiency is associated with subclinical neuroprotection in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 41271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maya, S.; Prakash, T.; Goli, D. Effect of wedelolactone and gallic acid on quinolinic acid-induced neurotoxicity and impaired motor function: Significance to sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurotoxicology 2018, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Platten, M.; Friedrich, M.; Wainwright, D.A.; Panitz, V.; Opitz, C.A. Tryptophan metabolism in brain tumors—IDO and beyond. Current opinion in immunology 2021, 70, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelace, M.D.; Varney, B.; Sundaram, G.; Franco, N.F.; Ng, M.L.; Pai, S.; Lim, C.K.; Guillemin, G.J.; Brew, B.J. Current evidence for a role of the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism in multiple sclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology 2016, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.; Suh, H.-S.; Tarassishin, L.; Cui, Q.L.; Durafourt, B.A.; Choi, N.; Bauman, A.; Cosenza-Nashat, M.; Antel, J.P.; Zhao, M.-L. The tryptophan metabolite 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid plays anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective roles during inflammation: role of hemeoxygenase-1. The American journal of pathology 2011, 179, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zádori, D.; Veres, G.; Szalárdy, L.; Klivényi, P.; Vécsei, L. Alzheimer’s disease: recent concepts on the relation of mitochondrial disturbances, excitotoxicity, neuroinflammation, and kynurenines. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2018, 62, 523–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, R.S.; Iradukunda, E.C.; Hughes, T.; Bowen, J.P. Modulation of enzyme activity in the kynurenine pathway by kynurenine monooxygenase inhibition. Frontiers in molecular biosciences 2019, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valotto Neto, L.J.; Reverete de Araujo, M.; Moretti Junior, R.C.; Mendes Machado, N.; Joshi, R.K.; Dos Santos Buglio, D.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Direito, R.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Investigating the Neuroprotective and Cognitive-Enhancing Effects of Bacopa monnieri: A Systematic Review Focused on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Apoptosis. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaudel, C.; Danne, C.; Agus, A.; Magniez, A.; Aucouturier, A.; Spatz, M.; Lefevre, A.; Kirchgesner, J.; Rolhion, N.; Wang, Y. Rewiring the altered tryptophan metabolism as a novel therapeutic strategy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut 2023, 72, 1296–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, C.A.; Somarribas Patterson, L.F.; Mohapatra, S.R.; Dewi, D.L.; Sadik, A.; Platten, M.; Trump, S. The therapeutic potential of targeting tryptophan catabolism in cancer. British journal of cancer 2020, 122, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.; Wu, Y.-H.; Song, Y.; Yu, B. Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) inhibitors in clinical trials for cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2021, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- El-Zahabi, M.A.A.; Abouzeid, M.Y.; Eissa, I.H.; Taghour, M.S. DUAL INHIBITORS OF INDOLEAMINE-2, 3-DIOXYGENASE (IDO) AND TRYPTOPHAN-2, 3-DIOXYGENASE (TDO) AS ANTI-TUMOR IMMUNE MODULATORS. Al-Azhar Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 69, 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plitman, E.; Iwata, Y.; Caravaggio, F.; Nakajima, S.; Chung, J.K.; Gerretsen, P.; Kim, J.; Takeuchi, H.; Chakravarty, M.M.; Remington, G. Kynurenic acid in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia bulletin 2017, 43, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Zhang, J. Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity: a perspective biomarker for laboratory determination in tumor immunotherapy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, T.W. Does kynurenic acid act on nicotinic receptors? An assessment of the evidence. Journal of neurochemistry 2020, 152, 627–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuwatari, T. Possibility of amino acid treatment to prevent the psychiatric disorders via modulation of the production of tryptophan metabolite kynurenic acid. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauzon, J.; Lee, G.; Cummings, J. Repurposed agents in the Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline. Alzheimer's research & therapy 2020, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Saranraj, K.; Kiran, P.U. Drug repurposing: Clinical practices and regulatory pathways. Perspectives in Clinical Research 2024, 10.4103.

- Patrignani, P.; Contursi, A.; Tacconelli, S.; Steinhilber, D. The future of pharmacology and therapeutics of the arachidonic acid cascade in the next decade: Innovative advancements in drug repurposing. Frontiers in pharmacology 2024, 15, 1472396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PANCHAL, N.B.; VAgHELA, V.M. " From Molecules to Medicine: The Remarkable Pharmacological Odyssey of Quinoline and It's Derivatives". Oriental Journal of Chemistry 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atukuri, D.; Vijayalaxmi, S.; Sanjeevamurthy, R.; Vidya, L.; Prasannakumar, R.; Raghavendra, M. Identification of quinoline-chalcones and heterocyclic chalcone-appended quinolines as broad-spectrum pharmacological agents. Bioorganic Chemistry 2020, 105, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elebiju, O.F.; Ajani, O.O.; Oduselu, G.O.; Ogunnupebi, T.A.; Adebiyi, E. Recent advances in functionalized quinoline scaffolds and hybrids—Exceptional pharmacophore in therapeutic medicine. Frontiers in Chemistry 2023, 10, 1074331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, T.; Umino, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Onozato, M. A review of chromatographic methods for bioactive tryptophan metabolites, kynurenine, kynurenic acid, quinolinic acid, and others, in biological fluids. Biomedical Chromatography 2022, 36, e5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapiuk, A.; Urbanska, E.M. Kynurenic acid in neurodegenerative disorders—unique neuroprotection or double-edged sword? CNS neuroscience & therapeutics 2022, 28, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, T.; Sandi, D.; Bencsik, K.; Vécsei, L. Kynurenines in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis: Therapeutic perspectives. Cells 2020, 9, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, F.; Cseh, E.K.; Vécsei, L. Natural molecules and neuroprotection: kynurenic acid, pantethine and α-lipoic acid. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.S.; Schmitz, F.; Marques, E.P.; Siebert, C.; Wyse, A.T. Intrastriatal quinolinic acid administration impairs redox homeostasis and induces inflammatory changes: prevention by kynurenic acid. Neurotoxicity Research 2020, 38, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitre, M.; Taleb, O.; Jeltsch-David, H.; Klein, C.; Mensah-Nyagan, A.G. Xanthurenic acid: A role in brain intercellular signaling. Journal of Neurochemistry 2024, 168, 2303–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-M.; Huang, C.-Y.; Lai, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-C.; Hwang, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-Y. Neuroprotection effects of kynurenic acid-loaded micelles for the Parkinson’s disease models. Journal of Liposome Research 2024, 34, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertelendy, P.; Toldi, J.; Fülöp, F.; Vécsei, L. Ischemic stroke and kynurenines: Medicinal chemistry aspects. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 25, 5945–5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Hernández, D.; Tendilla-Beltrán, H.; Madrigal, J.L.; García-Bueno, B.; Leza, J.C.; Caso, J.R. Chronic mild stress alters kynurenine pathways changing the glutamate neurotransmission in frontal cortex of rats. Molecular Neurobiology 2019, 56, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirthgen, E.; Hoeflich, A.; Rebl, A.; Günther, J. Kynurenic acid: the Janus-faced role of an immunomodulatory tryptophan metabolite and its link to pathological conditions. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 8, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitz, J. The kynurenine pathway: a finger in every pie. Molecular psychiatry 2020, 25, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, K.; Lőrinczi, B.; Fazakas, C.; Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F.; Kmetykó, N.; Berkecz, R.; Ilisz, I.; Krizbai, I.A.; Wilhelm, I. Szr-104, a novel kynurenic acid analogue with high permeability through the blood–brain barrier. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhász, Á.; Ungor, D.; Varga, N.; Katona, G.; Balogh, G.T.; Csapó, E. Lipid-Based nanocarriers for delivery of neuroprotective kynurenic acid: Preparation, characterization, and BBB transport. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 14251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, N.; Csapó, E.; Majláth, Z.; Ilisz, I.; Krizbai, I.A.; Wilhelm, I.; Knapp, L.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L.; Dékány, I. Targeting of the kynurenic acid across the blood–brain barrier by core-shell nanoparticles. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2016, 86, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, N.; Yamada, K.; Shibata, T.; Osago, H.; Hashimoto, T.; Tsuchiya, M. Elevation of cellular NAD levels by nicotinic acid and involvement of nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase in human cells. Journal of biological chemistry 2007, 282, 24574–24582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, R.-S.; Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. NAD (H) and NADP (H) redox couples and cellular energy metabolism. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2018, 28, 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Kameda, T.; Kamiya, T.; Abe, H.; Abe, T.; Tanuma, S.-i. Supplementation of nicotinic acid and its derivatives up-regulates cellular NAD+ level rather than nicotinamide derivatives in cultured normal human epidermal keratinocytes. Life 2024, 14, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.A. Nicotinic acid: the broad-spectrum lipid drug. A 50th anniversary review. Journal of internal medicine 2005, 258, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schachter, M. Strategies for modifying high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a role for nicotinic acid. Cardiovascular drugs and therapy 2005, 19, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, H.L.; Figge, J.; Souney, P.F.; Mutnick, A.H.; Sacks, F. Nicotinic acid: a review of its clinical use in the treatment of lipid disorders. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy 1988, 8, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.; Wu, T.-J.; Wu, K.K.; Sturino, C.; Metters, K.; Gottesdiener, K.; Wright, S.D.; Wang, Z.; O’Neill, G.; Lai, E. Antagonism of the prostaglandin D2 receptor 1 suppresses nicotinic acid-induced vasodilation in mice and humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 6682–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyo, Z.; Gille, A.; Bennett, C.L.; Clausen, B.E.; Offermanns, S. Nicotinic acid-induced flushing is mediated by activation of epidermal langerhans cells. Molecular pharmacology 2006, 70, 1844–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyó, Z.; Gille, A.; Kero, J.; Csiky, M.; Suchánková, M.C.; Nüsing, R.M.; Moers, A.; Pfeffer, K.; Offermanns, S. GPR109A (PUMA-G/HM74A) mediates nicotinic acid–induced flushing. The Journal of clinical investigation 2005, 115, 3634–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidy, N.; Grant, R.; Adams, S.; Brew, B.J.; Guillemin, G.J. Mechanism for quinolinic acid cytotoxicity in human astrocytes and neurons. Neurotoxicity research 2009, 16, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Huitrón, R.; Ugalde Muñiz, P.; Pineda, B.; Pedraza-Chaverrí, J.; Ríos, C.; Pérez-de la Cruz, V. Quinolinic acid: an endogenous neurotoxin with multiple targets. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2013, 2013, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurr, A.; West, C.A.; Rigor, B. Neurotoxicity of quinolinic acid and its derivatives in hypoxic rat hippocampal slices. Brain research 1991, 568, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Cruz, V.P.-D.; Carrillo-Mora, P.; Santamaría, A. Quinolinic acid, an endogenous molecule combining excitotoxicity, oxidative stress and other toxic mechanisms. International Journal of Tryptophan Research 2012, 5, IJTR–S8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leipnitz, G.; Schumacher, C.; Scussiato, K.; Dalcin, K.B.; Wannmacher, C.M.; Wyse, A.T.; Dutra-Filho, C.S.; Wajner, M.; Latini, A. Quinolinic acid reduces the antioxidant defenses in cerebral cortex of young rats. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 2005, 23, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Severiano, F.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.; Pedraza-Chaverrí, J.; Maldonado, P.D.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Ortíz-Plata, A.; Sánchez-García, A.; Villeda-Hernández, J.; Galván-Arzate, S.; Aguilera, P. S-Allylcysteine, a garlic-derived antioxidant, ameliorates quinolinic acid-induced neurotoxicity and oxidative damage in rats. Neurochemistry international 2004, 45, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, R.; Whetsell Jr, W.O.; Mangano, R.M. Quinolinic acid: an endogenous metabolite that produces axon-sparing lesions in rat brain. Science 1983, 219, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hestad, K.; Alexander, J.; Rootwelt, H.; Aaseth, J.O. The role of tryptophan dysmetabolism and quinolinic acid in depressive and neurodegenerative diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seal, C.J.; Heaton, F.W. Effect of dietary picolinic acid on the metabolism of exogenous and endogenous zinc in the rat. The Journal of nutrition 1985, 115, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, U.; Louache, F.; Titeux, M.; Thomopoulos, P.; Rochant, H. The iron-chelating agent picolinic acid enhances transferrin receptors expression in human erythroleukaemic cell lines. British journal of haematology 1985, 60, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodinger, J.; Loacker, L.J.; Schmidt, R.L.; Ratzinger, F.; Greiner, G.; Witzeneder, N.; Hoermann, G.; Jutz, S.; Pickl, W.F.; Steinberger, P. The tryptophan metabolite picolinic acid suppresses proliferation and metabolic activity of CD4+ T cells and inhibits c-Myc activation. Journal of Leucocyte Biology 2016, 99, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, H.; Shimizu, T.; Tatano, Y. Effects of picolinic acid on the antimicrobial functions of host macrophages against Mycobacterium avium complex. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2007, 29, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Sato, K.; Shimizu, T.; Yamabe, S.; Hiraki, M.; Sano, C.; Tomioka, H. Antimicrobial activity of picolinic acid against extracellular and intracellular Mycobacterium avium complex and its combined activity with clarithromycin, rifampicin and fluoroquinolones. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2006, 57, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco, M.C.; Rapisarda, A.; Massazza, S.; Melillo, G.; Young, H.; Varesio, L. The tryptophan catabolite picolinic acid selectively induces the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and-1β in macrophages. The Journal of Immunology 2000, 164, 3283–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, R.; Coggan, S.; Smythe, G.A. The physiological action of picolinic acid in the human brain. International journal of tryptophan research 2009, 2, IJTR–S2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockhill, J.; Jhamandas, K.; Boegman, R.; Beninger, R. Action of picolinic acid and structurally related pyridine carboxylic acids on quinolinic acid-induced cortical cholinergic damage. Brain research 1992, 599, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, B.E.; Jhamandas, K.; Boegman, R.J.; Beninger, R.J. Picolinic acid protects against quinolinic acid-induced depletion of NADPH diaphorase containing neurons in the rat striatum. Brain Research 1994, 668, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taleb, O.; Maammar, M.; Klein, C.; Maitre, M.; Mensah-Nyagan, A.G. A role for xanthurenic acid in the control of brain dopaminergic activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, F.; Lionetto, L.; Curto, M.; Iacovelli, L.; Copeland, C.S.; Neale, S.A.; Bruno, V.; Battaglia, G.; Salt, T.E.; Nicoletti, F. Cinnabarinic acid and xanthurenic acid: Two kynurenine metabolites that interact with metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Haneda, M.; Yoshino, M. Prooxidant action of xanthurenic acid and quinoline compounds: role of transition metals in the generation of reactive oxygen species and enhanced formation of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine in DNA. Biometals 2006, 19, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Ito, M.; Yoshino, M. Xanthurenic acid inhibits metal ion-induced lipid peroxidation and protects NADP-isocitrate dehydrogenase from oxidative inactivation. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology 2001, 47, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.L.; Dias, F.; Nunes, R.D.; Pereira, L.O.; Santos, T.S.; Chiarini, L.B.; Ramos, T.D.; Silva-Mendes, B.J.; Perales, J.; Valente, R.H. The antioxidant role of xanthurenic acid in the Aedes aegypti midgut during digestion of a blood meal. PloS one 2012, 7, e38349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicka-Stążka, P.; Langner, E.; Turski, W.; Rzeski, W.; Parada-Turska, J. Quinaldic acid in synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis and its effect on synoviocytes in vitro. Pharmacological Reports 2018, 70, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, H.; Miyamoto, S.; Mabuchi, H.; Yoneyama, Y.; Takeda, R. Insulin-releasing effect of quinaldic acid and its relatives on isolated Langerhans islets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1973, 53, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhamandas, K.H.; Boegman, R.J.; Beninger, R.J.; Miranda, A.F.; Lipic, K.A. Excitotoxicity of quinolinic acid: modulation by endogenous antagonists. Neurotox Res 2000, 2, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, M.; Radhakrishnan, T.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, G.P.; Dobraia, J.R.; Kirti, P.B. Erratum: Overexpression of a fusion defensin gene from radish and fenugreek improves resistance against leaf spot diseases caused by Cercospora arachidicola and Phaeoisariopsis personata in peanut. Turk J Biol 2019, 43, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Gao, Q.; Liu, W. Thiopeptide Antibiotics Exhibit a Dual Mode of Action against Intracellular Pathogens by Affecting Both Host and Microbe. Chem Biol 2015, 22, 1002–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhamandas, K.; Boegman, R.J.; Beninger, R.J.; Bialik, M. Quinolinate-induced cortical cholinergic damage: modulation by tryptophan metabolites. Brain Res 1990, 529, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Fishbein, J.; Hong, J.; Roeser, J.; Furie, R.A.; Aranow, C.; Volpe, B.T.; Diamond, B.; Mackay, M. Quinolinic acid, a kynurenine/tryptophan pathway metabolite, associates with impaired cognitive test performance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus Sci Med 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Kayakiri, H.; Abe, Y.; Mizutani, T.; Inamura, N.; Asano, M.; Hatori, C.; Aramori, I.; Oku, T.; Tanaka, H. Discovery of the first non-peptide full agonists for the human bradykinin B(2) receptor incorporating 4-(2-picolyloxy)quinoline and 1-(2-picolyl)benzimidazole frameworks. J Med Chem 2004, 47, 2853–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorana, A.; La Monica, G.; Lauria, A. Quinoline-Based Molecules Targeting c-Met, EGF, and VEGF Receptors and the Proteins Involved in Related Carcinogenic Pathways. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorai, P.; Pal, K.; Karmakar, P.; Saha, A. The development of two fluorescent chemosensors for the selective detection of Zn(2+) and Al(3+) ions in a quinoline platform by tuning the substituents in the receptor part: elucidation of the structures of the metal-bound chemosensors and biological studies. Dalton Trans 2020, 49, 4758–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikata, Y. Quinoline- and isoquinoline-derived ligand design on TQEN (N,N,N',N'-tetrakis(2-quinolylmethyl)ethylenediamine) platform for fluorescent sensing of specific metal ions and phosphate species. Dalton Trans 2020, 49, 17494–17504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.R. Quinolone molecular structure-activity relationships: what we have learned about improving antimicrobial activity. Clin Infect Dis 2001, 33 Suppl 3, S180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, F.; Jin, G. Structural basis of quinolone derivatives, inhibition of type I and II topoisomerases and inquiry into the relevance of bioactivity in odd or even branches with molecular docking study. J Mol Struct 2020, 1221, 128869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, K.; Haneda, M.; Yoshino, M. Prooxidant action of xanthurenic acid and quinoline compounds: role of transition metals in the generation of reactive oxygen species and enhanced formation of 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine in DNA. Biometals 2006, 19, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fray, M.J.; Bull, D.J.; Carr, C.L.; Gautier, E.C.; Mowbray, C.E.; Stobie, A. Structure-activity relationships of 1,4-dihydro-(1H,4H)-quinoxaline-2,3-diones as N-methyl-D-aspartate (glycine site) receptor antagonists. 1. Heterocyclic substituted 5-alkyl derivatives. J Med Chem 2001, 44, 1951–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre, M.; Taleb, O.; Jeltsch-David, H.; Klein, C.; Mensah-Nyagan, A.G. Xanthurenic acid: A role in brain intercellular signaling. J Neurochem 2024, 168, 2303–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Z.; Vanecek, A.S.; Tepe, J.J.; Odom, A.L. Synthesis, structure, properties, and cytotoxicity of a (quinoline)RuCp(+) complex. Dalton Trans 2023, 52, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Wellen, K.E. Advances into understanding metabolites as signaling molecules in cancer progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2020, 63, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liloia, D.; Zamfira, D.A.; Tanaka, M.; Manuello, J.; Crocetta, A.; Keller, R.; Cozzolino, M.; Duca, S.; Cauda, F.; Costa, T. Disentangling the role of gray matter volume and concentration in autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analytic investigation of 25 years of voxel-based morphometry research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2024, 105791.

- Boros, F.; Vécsei, L. Progress in the development of kynurenine and quinoline-3-carboxamide-derived drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2020, 29, 1223–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, T.W. Neuropharmacology of quinolinic and kynurenic acids. Pharmacol Rev 1993, 45, 309–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, T.W. Kynurenines in the CNS: from endogenous obscurity to therapeutic importance. Prog Neurobiol 2001, 64, 185–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, T.W.; Stoy, N.; Darlington, L.G. An expanding range of targets for kynurenine metabolites of tryptophan. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2013, 34, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Lamson, A.R.; Shelley, M.; Troyanskaya, O. Interpretable neural architecture search and transfer learning for understanding CRISPR-Cas9 off-target enzymatic reactions. Nat Comput Sci 2023, 3, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, P.A.; Shin, C.B.; Arroyo-Currás, N.; Ortega, G.; Li, W.; Keller, A.A.; Plaxco, K.W.; Kippin, T.E. Ultra-High-Precision, in-vivo Pharmacokinetic Measurements Highlight the Need for and a Route Toward More Highly Personalized Medicine. Front Mol Biosci 2019, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Monitoring the kynurenine system: Concentrations, ratios or what else? Adv Clin Exp Med 2021, 30, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Yang, L.; He, D.; Li, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhang, J. Metabolic pathways and pharmacokinetics of natural medicines with low permeability. Drug Metab Rev 2017, 49, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matada, B.S.; Pattanashettar, R.; Yernale, N.G. A comprehensive review on the biological interest of quinoline and its derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem 2021, 32, 115973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, L.A. Nicotinic acid: the broad-spectrum lipid drug. A 50th anniversary review. J Intern Med 2005, 258, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.; Hussain, K.; Shehzadi, N.; Arshad, M.; Arshad, M.N.; Iftikhar, S.; Saghir, F.; Shaukat, A.; Sarfraz, M.; Ahmed, N. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking studies of quinoline-anthranilic acid hybrids as potent anti-inflammatory drugs. Org Biomol Chem 2024, 22, 3708–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabiyat, S.; Alzoubi, A.; Al-Daghistani, H.; Al-Hiari, Y.; Kasabri, V.; Alkhateeb, R. Evaluation of Quinoline-Related Carboxylic Acid Derivatives as Prospective Differentially Antiproliferative, Antioxidative, and Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Chem Biol Drug Des 2024, 104, e14615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Xie, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, H.; Ren, H.; Tang, S.; Liu, Q.; Huang, M.; Shao, X.; Li, C.; et al. Discovery of Novel Imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline Derivatives to Treat Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) by Inhibiting Multiple Proinflammatory Signaling Pathways and Restoring Intestinal Homeostasis. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 11949–11969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, X.F.; Morris-Natschke, S.L.; Liu, Y.Q.; Guo, X.; Xu, X.S.; Goto, M.; Li, J.C.; Yang, G.Z.; Lee, K.H. Biologically active quinoline and quinazoline alkaloids part I. Med Res Rev 2018, 38, 775–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wei, C.; Wu, J.; Yang, X. Quinolines: A Promising Heterocyclic Scaffold for Cancer Therapeutics. Curr Med Chem 2025, 32, 958–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, L.T.; Kadriu, B.; Gould, T.D.; Zanos, P.; Greenstein, D.; Evans, J.W.; Yuan, P.; Farmer, C.A.; Oppenheimer, M.; George, J.M. A randomized trial of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor glycine site antagonist prodrug 4-chlorokynurenine in treatment-resistant depression. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 23, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyes, M.P.; Saito, K.; Crowley, J.S.; Davis, L.E.; Demitrack, M.A.; Der, M.; Dilling, L.A.; Elia, J.; Kruesi, M.J.; Lackner, A.; et al. Quinolinic acid and kynurenine pathway metabolism in inflammatory and non-inflammatory neurological disease. Brain 1992, 115 ( Pt 5) Pt 5, 1249–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadela-Tomanek, M.; Jastrzębska, M.; Chrobak, E.; Bębenek, E. Lipophilicity and ADMET Analysis of Quinoline-1,4-quinone Hybrids. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elebiju, O.F.; Ajani, O.O.; Oduselu, G.O.; Ogunnupebi, T.A.; Adebiyi, E. Recent advances in functionalized quinoline scaffolds and hybrids-Exceptional pharmacophore in therapeutic medicine. Front Chem 2022, 10, 1074331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platten, M.; Nollen, E.A.A.; Röhrig, U.F.; Fallarino, F.; Opitz, C.A. Tryptophan metabolism as a common therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegeneration and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.; Suh, H.S.; Tarassishin, L.; Cui, Q.L.; Durafourt, B.A.; Choi, N.; Bauman, A.; Cosenza-Nashat, M.; Antel, J.P.; Zhao, M.L.; et al. The tryptophan metabolite 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid plays anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective roles during inflammation: role of hemeoxygenase-1. Am J Pathol 2011, 179, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, S.; Fang, X.; Guo, L.; Hu, N.; Guo, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; He, J.C.; Kuang, C.; et al. N-Benzyl/Aryl Substituted Tryptanthrin as Dual Inhibitors of Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase and Tryptophan 2,3-Dioxygenase. J Med Chem 2019, 62, 9161–9174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolšak, A.; Gobec, S.; Sova, M. Indoleamine and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenases as important future therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Ther 2021, 221, 107746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Leme Boaro, B.; da Silva Camarinha Oliveira, J.; Patočka, J.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Tanaka, M.; Laurindo, L.F. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Neuroinflammation Intervention with Medicinal Plants: A Critical and Narrative Review of the Current Literature. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Monitoring the Redox Status in Multiple Sclerosis. Biomedicines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löscher, W.; Gericke, B. Novel Intrinsic Mechanisms of Active Drug Extrusion at the Blood-Brain Barrier: Potential Targets for Enhancing Drug Delivery to the Brain? Pharmaceutics 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuchero, Y.J.; Chen, X.; Bien-Ly, N.; Bumbaca, D.; Tong, R.K.; Gao, X.; Zhang, S.; Hoyte, K.; Luk, W.; Huntley, M.A.; et al. Discovery of Novel Blood-Brain Barrier Targets to Enhance Brain Uptake of Therapeutic Antibodies. Neuron 2016, 89, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terstappen, G.C.; Meyer, A.H.; Bell, R.D.; Zhang, W. Strategies for delivering therapeutics across the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dounay, A.B.; Tuttle, J.B.; Verhoest, P.R. Challenges and Opportunities in the Discovery of New Therapeutics Targeting the Kynurenine Pathway. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 8762–8782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.L.; Pernet, A.G. Mechanism of inhibition of DNA gyrase by analogues of nalidixic acid: the target of the drugs is DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1985, 82, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.A.; Wilson, S.; Farrar, C.; Richardson, A.P. The reflex respiratory and circulatory actions of some cinchoninic acid derivatives and a number of unrelated compounds. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1952, 104, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Direito, R.; Tanaka, M.; Jasmin Santos German, I.; Lamas, C.B.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; Fiorini, A.M.R. Polyphenols, Alkaloids, and Terpenoids Against Neurodegeneration: Evaluating the Neuroprotective Effects of Phytocompounds Through a Comprehensive Review of the Current Evidence. Metabolites 2025, 15, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herraiz, T.; Guillén, H.; González-Peña, D.; Arán, V.J. Antimalarial Quinoline Drugs Inhibit β-Hematin and Increase Free Hemin Catalyzing Peroxidative Reactions and Inhibition of Cysteine Proteases. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 15398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapishnikov, S.; Staalsø, T.; Yang, Y.; Lee, J.; Pérez-Berná, A.J.; Pereiro, E.; Yang, Y.; Werner, S.; Guttmann, P.; Leiserowitz, L.; et al. Mode of action of quinoline antimalarial drugs in red blood cells infected by Plasmodium falciparum revealed in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 22946–22952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, M.; Tilley, L. Quinoline antimalarials: mechanisms of action and resistance and prospects for new agents. Pharmacol Ther 1998, 79, 55–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, J.P.; Brown, R.A.; Will, G. Observations on the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with butazolidin. Ann Rheum Dis 1953, 12, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelfman, D.M. Reflections on quinine and its importance in dermatology today. Clin Dermatol 2021, 39, 900–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukusheva, G.K.; Zhasymbekova, A.R.; Seidakhmetova, R.B.; Nurkenov, O.A.; Akishina, E.A.; Petkevich, S.K.; Dikusar, E.A.; Potkin, V.I. Quinine Esters with 1,2-Azole, Pyridine and Adamantane Fragments. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man-Son-Hing, M.; Wells, G.; Lau, A. Quinine for nocturnal leg cramps: a meta-analysis including unpublished data. J Gen Intern Med 1998, 13, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisselmann, G.; Alisch, D.; Welbers-Joop, B.; Hatt, H. Effects of Quinine, Quinidine and Chloroquine on Human Muscle Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jin, X.; Wu, T.; Huang, G.; Wu, K.; Lei, J.; Pan, X.; Yan, N. Structural Basis for Pore Blockade of the Human Cardiac Sodium Channel Na(v) 1.5 by the Antiarrhythmic Drug Quinidine*. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2021, 60, 11474–11480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J.; Duff, H.J.; Sheldon, R.S. Class I antiarrhythmic drug receptor: biochemical evidence for state-dependent interaction with quinidine and lidocaine. Mol Pharmacol 1989, 36, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, I.; Toyama, J.; Yamada, K. Open and inactivated sodium channel block by class-I antiarrhythmic drugs. Jpn Heart J 1986, 27 Suppl 1, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, H.L., Jr.; Luchi, R.J. SOME CELLULAR AND METABOLIC CONSIDERATIONS RELATING TO THE ACTION OF QUINIDINE AS A PROTOTYPE ANTIARRHYTHMIC AGENT. Am J Med 1964, 37, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Fan, P.; Shi, Y.; Feng, L.; Wang, J.; Zhan, G.; Li, B. Stereoselective Blockage of Quinidine and Quinine in the hERG Channel and the Effect of Their Rescue Potency on Drug-Induced hERG Trafficking Defect. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocks, D.R.; Mehvar, R. Stereoselectivity in the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the chiral antimalarial drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003, 42, 1359–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Camm, A.J. Evaluation of drug-induced QT interval prolongation: implications for drug approval and labelling. Drug Saf 2001, 24, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeusler, I.L.; Chan, X.H.S.; Guérin, P.J.; White, N.J. The arrhythmogenic cardiotoxicity of the quinoline and structurally related antimalarial drugs: a systematic review. BMC Med 2018, 16, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, M.J.; Higgins, S.L.; Payne, A.G.; Mann, D.E. Effects of quinidine versus procainamide on the QT interval. Am J Cardiol 1986, 58, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Sheng, L.; Larson, P.; Liu, X.; Zou, X.; Wang, S.; Guo, K.; Ma, C.; Zhang, G.; et al. A Cinchona Alkaloid Antibiotic That Appears To Target ATP Synthase in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Med Chem 2019, 62, 2305–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boratyński, P.J.; Zielińska-Błajet, M.; Skarżewski, J. Cinchona Alkaloids-Derivatives and Applications. Alkaloids Chem Biol 2019, 82, 29–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chajdaś, Z.; Kucharska, M.; Wesełucha-Birczyńska, A. Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy (2D-COS) Tracking of the Formation of Selected Transition Metal Compounds Cu(II) and Cd(II) With Cinchonine and Their Impact on Model Components of Erythrocytes. Appl Spectrosc 2024, 37028241279434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabłońska-Trypuć, A.; Wydro, U.; Wołejko, E.; Świderski, G.; Lewandowski, W. Biological Activity of New Cichoric Acid-Metal Complexes in Bacterial Strains, Yeast-Like Fungi, and Human Cell Cultures In Vitro. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramić, A.; Skočibušić, M.; Odžak, R.; Čipak Gašparović, A.; Milković, L.; Mikelić, A.; Sović, K.; Primožič, I.; Hrenar, T. Antimicrobial Activity of Quasi-Enantiomeric Cinchona Alkaloid Derivatives and Prediction Model Developed by Machine Learning. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, S.; Maurya, N.; Meena, A.; Luqman, S. Cinchonine: A Versatile Pharmacological Agent Derived from Natural Cinchona Alkaloids. Curr Top Med Chem 2024, 24, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluraya, B.; Sreenivasa, S. Synthesis and pharmacological properties of some quinoline derivatives. Farmaco 1998, 53, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.R.; Malik, M.; Snyder, M.; Drlica, K. DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV on the bacterial chromosome: quinolone-induced DNA cleavage. J Mol Biol 1996, 258, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drlica, K.; Zhao, X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 1997, 61, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, A.C.; Panda, S.S. DNA Gyrase as a Target for Quinolones. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.G.; Li, Z.W.; Hu, X.X.; Si, S.Y.; You, X.F.; Tang, S.; Wang, Y.X.; Song, D.Q. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Quinoline Derivatives as a Novel Class of Broad-Spectrum Antibacterial Agents. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamkhenshorngphanuch, T.; Kulkraisri, K.; Janjamratsaeng, A.; Plabutong, N.; Thammahong, A.; Manadee, K.; Na Pombejra, S.; Khotavivattana, T. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of Novel 4-Hydroxy-2-quinolone Analogs. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, A.; Tejchman, W.; Pawlak, A.M.; Mokrzyński, K.; Różanowski, B.; Musielak, B.M.; Greczek-Stachura, M. Preliminary Studies of Antimicrobial Activity of New Synthesized Hybrids of 2-Thiohydantoin and 2-Quinolone Derivatives Activated with Blue Light. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostopoulou, I.; Tzani, A.; Chronaki, K.; Prousis, K.C.; Pontiki, E.; Hadjiplavlou-Litina, D.; Detsi, A. Novel Multi-Target Agents Based on the Privileged Structure of 4-Hydroxy-2-quinolinone. Molecules 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gach-Janczak, K.; Piekielna-Ciesielska, J.; Waśkiewicz, J.; Krakowiak, K.; Wtorek, K.; Janecka, A. Quinolin-4-ones: Methods of Synthesis and Application in Medicine. Molecules 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Kelley, S.O. Enhancing the Potency of Nalidixic Acid toward a Bacterial DNA Gyrase with Conjugated Peptides. ACS Chem Biol 2017, 12, 2563–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, A.; Badshah, S.L.; Muska, M.; Ahmad, N.; Khan, K. The Current Case of Quinolones: Synthetic Approaches and Antibacterial Activity. Molecules 2016, 21, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fàbrega, A.; Madurga, S.; Giralt, E.; Vila, J. Mechanism of action of and resistance to quinolones. Microb Biotechnol 2009, 2, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.B. Mode of action, and in vitro and in vivo activities of the fluoroquinolones. J Clin Pharmacol 1988, 28, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, G.J.; Williams, J.D. Frequency of appearance of resistant variants to norfloxacin and nalidixic acid. J Antimicrob Chemother 1984, 13 Suppl B, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majalekar, P.P.; Shirote, P.J. Fluoroquinolones: Blessings Or Curses. Curr Drug Targets 2020, 21, 1354–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, A.M. NALIDIXIC ACID IN INFECTIONS OF URINARY TRACT. LABORATORY AND CLINICAL INVESTIGATIONS. Br Med J 1963, 2, 1308–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, D.S.; Lacey, R.W.; Mummery, R.V.; Mahendra, M.; Bint, A.J.; Newsom, S.W. Treatment of acute urinary infection by norfloxacin or nalidixic acid/citrate: a multi-centre comparative study. J Antimicrob Chemother 1984, 13 Suppl B, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, E.C.; Manes, S.H.; Drlica, K. Differential effects of antibiotics inhibiting gyrase. J Bacteriol 1982, 149, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuuchi, K.; O'Dea, M.H.; Gellert, M. DNA gyrase: subunit structure and ATPase activity of the purified enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1978, 75, 5960–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.L.; Heller, K.; Gellert, M.; Zubay, G. Differential sensitivity of gene expression in vitro to inhibitors of DNA gyrase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1979, 76, 3304–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, E.; Tilocca, B.; Roncada, P. Antimicrobial resistance in veterinary medicine: An overview. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.N.; Watts, J.L.; Gilbert, J.M. Questions associated with the development of novel drugs intended for the treatment of bacterial infections in veterinary species. The Veterinary Journal 2019, 248, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomba, C.; Rantala, M.; Greko, C.; Baptiste, K.E.; Catry, B.; Van Duijkeren, E.; Mateus, A.; Moreno, M.A.; Pyörälä, S.; Ružauskas, M. Public health risk of antimicrobial resistance transfer from companion animals. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2017, 72, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.S.; Hooper, D.C. The fluoroquinolones: structures, mechanisms of action and resistance, and spectra of activity in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1985, 28, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, Z. Room-Temperature Phosphorescence of Nicotinic Acid and Isonicotinic Acid: Efficient Intermolecular Hydrogen-Bond Interaction in Molecular Array. J Phys Chem Lett 2022, 13, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.; Jaw, R.; Grecz, N. Role of chelation and water binding of calcium in dormancy and heat resistance of bacterial endospores. Bioinorganic Chemistry 1978, 8, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.E.; Badawy, E.T.; Aboukhatwa, S.M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.M.; Kabbash, A.; Abo Elseoud, K.A. Isonicotinic acid N-oxide, from isoniazid biotransformation by Aspergillus niger, as an InhA inhibitor antituberculous agent against multiple and extensively resistant strains supported by in silico docking and ADME prediction. Nat Prod Res 2023, 37, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, C.; Macdonald, I.K.; Murphy, E.J.; Brown, K.A.; Raven, E.L.; Moody, P.C. The tuberculosis prodrug isoniazid bound to activating peroxidases. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 6193–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volynets, G.P.; Tukalo, M.A.; Bdzhola, V.G.; Derkach, N.M.; Gumeniuk, M.I.; Tarnavskiy, S.S.; Yarmoluk, S.M. Novel isoniazid derivative as promising antituberculosis agent. Future Microbiol 2020, 15, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, V.; Narasimhan, B.; Ahuja, M.; Sriram, D.; Yogeeswari, P.; De Clercq, E.; Pannecouque, C.; Balzarini, J. Synthesis, antimycobacterial, antiviral, antimicrobial activity and QSAR studies of N(2)-acyl isonicotinic acid hydrazide derivatives. Med Chem 2013, 9, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.C. Germination of bacterial spores by calcium chelates of dipicolinic acid analogues. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1972, 247, 1861–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintze, P.E.; Nicholson, W.L. Single-spore elemental analyses indicate that dipicolinic acid-deficient Bacillus subtilis spores fail to accumulate calcium. Archives of microbiology 2010, 192, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.Y.; Thomas, P.W.; Stewart, A.C.; Bergstrom, A.; Cheng, Z.; Miller, C.; Bethel, C.R.; Marshall, S.H.; Credille, C.V.; Riley, C.L.; et al. Dipicolinic Acid Derivatives as Inhibitors of New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase-1. J Med Chem 2017, 60, 7267–7283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, B.D.; Halvorson, H. Dependence of the heat resistance of bacterial endospores on their dipicolinic acid content. Nature 1959, 183, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecz, N.; Tang, T. Relation of dipicolinic acid to heat resistance of bacterial spores. J Gen Microbiol 1970, 63, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setlow, B.; Atluri, S.; Kitchel, R.; Koziol-Dube, K.; Setlow, P. Role of dipicolinic acid in resistance and stability of spores of Bacillus subtilis with or without DNA-protective alpha/beta-type small acid-soluble proteins. J Bacteriol 2006, 188, 3740–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, K.L.; Pushie, M.J.; Sopasis, G.J.; James, A.K.; Dolgova, N.V.; Sokaras, D.; Kroll, T.; Harris, H.H.; Pickering, I.J.; George, G.N. Solution Chemistry of Copper(II) Binding to Substituted 8-Hydroxyquinolines. Inorg Chem 2020, 59, 13858–13874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierre, J.L.; Baret, P.; Serratrice, G. Hydroxyquinolines as iron chelators. Curr Med Chem 2003, 10, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pape, V.F.S.; May, N.V.; Gál, G.T.; Szatmári, I.; Szeri, F.; Fülöp, F.; Szakács, G.; Enyedy É, A. Impact of copper and iron binding properties on the anticancer activity of 8-hydroxyquinoline derived Mannich bases. Dalton Trans 2018, 47, 17032–17045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Ji, Z.; Fang, T.; Lu, H.; Yan, L.; Shen, F.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Discovery of Novel 8-Hydroxyquinoline Derivatives with Potent In Vitro and In Vivo Antifungal Activity. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 16364–16376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, A.Y.; Chen, C.P.; Roffler, S. A chelating agent possessing cytotoxicity and antimicrobial activity: 7-morpholinomethyl-8-hydroxyquinoline. Life Sci 1999, 64, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherdtrakulkiat, R.; Boonpangrak, S.; Sinthupoom, N.; Prachayasittikul, S.; Ruchirawat, S.; Prachayasittikul, V. Derivatives (halogen, nitro and amino) of 8-hydroxyquinoline with highly potent antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Biochem Biophys Rep 2016, 6, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Bergamini, C.; Fato, R.; Soukup, O.; Korabecny, J.; Andrisano, V.; Bartolini, M.; Bolognesi, M.L. Novel 8-Hydroxyquinoline Derivatives as Multitarget Compounds for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 1284–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bachiller, M.I.; Pérez, C.; González-Muñoz, G.C.; Conde, S.; López, M.G.; Villarroya, M.; García, A.G.; Rodríguez-Franco, M.I. Novel tacrine-8-hydroxyquinoline hybrids as multifunctional agents for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, with neuroprotective, cholinergic, antioxidant, and copper-complexing properties. J Med Chem 2010, 53, 4927–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prachayasittikul, V.; Prachayasittikul, S.; Ruchirawat, S.; Prachayasittikul, V. 8-Hydroxyquinolines: a review of their metal chelating properties and medicinal applications. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013, 7, 1157–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, F.; Lionetto, L.; Curto, M.; Iacovelli, L.; Cavallari, M.; Zappulla, C.; Ulivieri, M.; Napoletano, F.; Capi, M.; Corigliano, V.; et al. Xanthurenic Acid Activates mGlu2/3 Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors and is a Potential Trait Marker for Schizophrenia. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 17799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, F.; Lionetto, L.; Curto, M.; Iacovelli, L.; Copeland, C.S.; Neale, S.A.; Bruno, V.; Battaglia, G.; Salt, T.E.; Nicoletti, F. Cinnabarinic acid and xanthurenic acid: Two kynurenine metabolites that interact with metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taleb, O.; Maammar, M.; Brumaru, D.; Bourguignon, J.J.; Schmitt, M.; Klein, C.; Kemmel, V.; Maitre, M.; Mensah-Nyagan, A.G. Xanthurenic acid binds to neuronal G-protein-coupled receptors that secondarily activate cationic channels in the cell line NCB-20. PLoS One 2012, 7, e48553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haruki, H.; Hovius, R.; Pedersen, M.G.; Johnsson, K. Tetrahydrobiopterin Biosynthesis as a Potential Target of the Kynurenine Pathway Metabolite Xanthurenic Acid. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, L.; Larsson, A.; Begum, A.; Iakovleva, I.; Carlsson, M.; Brännström, K.; Sauer-Eriksson, A.E.; Olofsson, A. Modifications of the 7-Hydroxyl Group of the Transthyretin Ligand Luteolin Provide Mechanistic Insights into Its Binding Properties and High Plasma Specificity. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0153112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontermann, R.E. Half-life extended biotherapeutics. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2016, 16, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contella, L.; Farrell, C.L.; Boccuto, L.; Litwin, A.; Snyder, M.L. Gene Variant Frequencies of IDO1, IDO2, TDO, and KMO in Substance Use Disorder Cohorts. Genes (Basel) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procaccini, C.; Santopaolo, M.; Faicchia, D.; Colamatteo, A.; Formisano, L.; de Candia, P.; Galgani, M.; De Rosa, V.; Matarese, G. Role of metabolism in neurodegenerative disorders. Metabolism 2016, 65, 1376–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.C.O.; do Vale, T.M.; Gomes, R.L.M.; Forezi, L.; de Souza, M.; Batalha, P.N.; Boechat, F. Exploring 4-quinolone-3-carboxamide derivatives: A versatile framework for emerging biological applications. Bioorg Chem 2025, 157, 108240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Lal, S.; Narang, R.; Sudhakar, K. Quinoline Hydrazide/Hydrazone Derivatives: Recent Insights on Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Action. ChemMedChem 2023, 18, e202200571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, T.W.; Forrest, C.M.; Darlington, L.G. Kynurenine pathway inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for neuroprotection. Febs j 2012, 279, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lv, H.; Guo, Y.; Teka, T.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Han, L.; Pan, G. Structure-Based Reactivity Profiles of Reactive Metabolites with Glutathione. Chem Res Toxicol 2020, 33, 1579–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musiol, R. An overview of quinoline as a privileged scaffold in cancer drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2017, 12, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Dong, C.; Zhang, X. Recent Advances in Pro-PROTAC Development to Address On-Target Off-Tumor Toxicity. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 8428–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles, O.; Romo, D. Chemo- and site-selective derivatizations of natural products enabling biological studies. Nat Prod Rep 2014, 31, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajani, O.O.; Iyaye, K.T.; Ademosun, O.T. Recent advances in chemistry and therapeutic potential of functionalized quinoline motifs - a review. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 18594–18614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Fang, J.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Xie, Y.P.; Lu, X. Structural diversity of copper(I) alkynyl cluster-based coordination polymers utilizing bifunctional pyridine carboxylic acid ligands. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 17817–17824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaku, E.; Smith, D.T.; Njardarson, J.T. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J Med Chem 2014, 57, 10257–10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C. Tuning receptor signaling through ligand engineering. The FASEB Journal 2020, 34, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.H.; Acree Jr, W.E. On the solubility of nicotinic acid and isonicotinic acid in water and organic solvents. The Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics 2013, 61, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotammagari, T.K.; Saleh, L.Y.; Lönnberg, T. Organometallic modification confers oligonucleotides new functionalities. Chem Commun (Camb) 2024, 60, 3118–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MURAKAMI, K.; UEDA, T.; MORIKAWA, R.; ITO, M.; HANEDA, M.; YOSHINO, M. Antioxidant effect of dipicolinic acid on the metal-catalyzed lipid peroxidation and enzyme inactivation. Biomedical Research 1998, 19, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattatray Shinde, S.; Kumar Behera, S.; Kulkarni, N.; Dewangan, B.; Sahu, B. Bifunctional backbone modified squaramide dipeptides as amyloid beta (Aβ) aggregation inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem 2024, 97, 117538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, S.A.; Henry, R.J.; Blanchard, A.C.; Stoica, B.A.; Loane, D.J.; Faden, A.I. Enhanced Akt/GSK-3β/CREB signaling mediates the anti-inflammatory actions of mGluR5 positive allosteric modulators in microglia and following traumatic brain injury in male mice. J Neurochem 2021, 156, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Dingledine, R. Prostaglandin receptor EP2 in the crosshairs of anti-inflammation, anti-cancer, and neuroprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2013, 34, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcucci, R.M.; Wertz, R.; Green, J.L.; Meucci, O.; Salvino, J.; Fontana, A.C.K. Novel Positive Allosteric Modulators of Glutamate Transport Have Neuroprotective Properties in an in Vitro Excitotoxic Model. ACS Chem Neurosci 2019, 10, 3437–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Li, W.X.; Dai, S.X.; Guo, Y.C.; Han, F.F.; Zheng, J.J.; Li, G.H.; Huang, J.F. Meta-Analysis of Parkinson's Disease and Alzheimer's Disease Revealed Commonly Impaired Pathways and Dysregulation of NRF2-Dependent Genes. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 56, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Nao, J.; Dong, X. The Therapeutic Potential of Hydroxycinnamic Acid Derivatives in Parkinson's Disease: Focus on In Vivo Research Advancements. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 10932–10951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagotto, G.L.d.O.; Santos, L.M.O.d.; Osman, N.; Lamas, C.B.; Laurindo, L.F.; Pomini, K.T.; Guissoni, L.M.; Lima, E.P.d.; Goulart, R.d.A.; Catharin, V.M.S. Ginkgo biloba: a leaf of hope in the fight against Alzheimer’s dementia: clinical trial systematic review. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomé, C.; Salomé-Grosjean, E.; Park, K.D.; Morieux, P.; Swendiman, R.; DeMarco, E.; Stables, J.P.; Kohn, H. Synthesis and anticonvulsant activities of (R)-N-(4'-substituted)benzyl 2-acetamido-3-methoxypropionamides. J Med Chem 2010, 53, 1288–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Buzatu, D.; Harris, S.; Wilkes, J. Development of models for predicting Torsade de Pointes cardiac arrhythmias using perceptron neural networks. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis de Oliveira, B.; Gonçalves de Oliveira, F.; de Assis Cruz, O.; Mendonça de Assis, P.; Glanzmann, N.; David da Silva, A.; Rezende Barbosa Raposo, N.; Zabala Capriles Goliatt, P.V. In Silico and In Vitro Evaluation of Quinoline Derivatives as Potential Inhibitors of AChE, BACE1, and GSK3β for Neurodegenerative Diseases Treatment. Chem Biodivers 2025, 22, e202401629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zindo, F.T.; Joubert, J.; Malan, S.F. Propargylamine as functional moiety in the design of multifunctional drugs for neurodegenerative disorders: MAO inhibition and beyond. Future Med Chem 2015, 7, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janse van Rensburg, H.D.; Terre'Blanche, G.; van der Walt, M.M.; Legoabe, L.J. 5-Substituted 2-benzylidene-1-tetralone analogues as A(1) and/or A(2A) antagonists for the potential treatment of neurological conditions. Bioorg Chem 2017, 74, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongarzone, S.; Bolognesi, M.L. The concept of privileged structures in rational drug design: focus on acridine and quinoline scaffolds in neurodegenerative and protozoan diseases. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2011, 6, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, J.V.; Petersson, E.J.; Chenoweth, D.M. Rational Design and Facile Synthesis of a Highly Tunable Quinoline-Based Fluorescent Small-Molecule Scaffold for Live Cell Imaging. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140, 9486–9493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, A.C.; Kemp, J.A.; Leeson, P.D.; Grimwood, S.; Donald, A.E.; Marshall, G.R.; Priestley, T.; Smith, J.D.; Carling, R.W. Kynurenic acid analogues with improved affinity and selectivity for the glycine site on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor from rat brain. Mol Pharmacol 1992, 41, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, J.A.; Priestley, T. Effects of (+)-HA-966 and 7-chlorokynurenic acid on the kinetics of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor agonist responses in rat cultured cortical neurons. Mol Pharmacol 1991, 39, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloog, Y.; Lamdani-Itkin, H.; Sokolovsky, M. The glycine site of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel: differences between the binding of HA-966 and of 7-chlorokynurenic acid. J Neurochem 1990, 54, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Q.; Salituro, F.G.; Schwarcz, R. Enzyme-catalyzed production of the neuroprotective NMDA receptor antagonist 7-chlorokynurenic acid in the rat brain in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol 1997, 319, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Shah, K. Quinolines, a perpetual, multipurpose scaffold in medicinal chemistry. Bioorg Chem 2021, 109, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolšak, A.; Švajger, U.; Lešnik, S.; Konc, J.; Gobec, S.; Sova, M. Selective Toll-like receptor 7 agonists with novel chromeno[3,4-d]imidazol-4(1H)-one and 2-(trifluoromethyl)quinoline/ quinazoline-4-amine scaffolds. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 179, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konieczny, J.; Ossowska, K.; Schulze, G.; Coper, H.; Wolfarth, S. L-701,324, a selective antagonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor, counteracts haloperidol-induced muscle rigidity in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999, 143, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, J.A.; Foster, A.C.; Leeson, P.D.; Priestley, T.; Tridgett, R.; Iversen, L.L.; Woodruff, G.N. 7-Chlorokynurenic acid is a selective antagonist at the glycine modulatory site of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988, 85, 6547–6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.C.; Procureur, D.; Wood, P.L. 7-Chlorokynurenate prevents NMDA-induced and kainate-induced striatal lesions. Brain Res 1993, 620, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.L.; Wang, S.J.; Liu, M.M.; Shi, H.S.; Zhang, R.X.; Liu, J.F.; Ding, Z.B.; Lu, L. Glycine site N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist 7-CTKA produces rapid antidepressant-like effects in male rats. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2013, 38, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koek, W.; Colpaert, F.C. Selective blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-induced convulsions by NMDA antagonists and putative glycine antagonists: relationship with phencyclidine-like behavioral effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990, 252, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, E.R.; Bussey, T.J.; Phillips, A.G. A glycine antagonist 7-chlorokynurenic acid attenuates ischemia-induced learning deficits. Neuroreport 1993, 4, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, L.T.; Kadriu, B.; Gould, T.D.; Zanos, P.; Greenstein, D.; Evans, J.W.; Yuan, P.; Farmer, C.A.; Oppenheimer, M.; George, J.M.; et al. A Randomized Trial of the N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor Glycine Site Antagonist Prodrug 4-Chlorokynurenine in Treatment-Resistant Depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2020, 23, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, B.M.; Harrison, B.L.; Miller, F.P.; McDonald, I.A.; Salituro, F.G.; Schmidt, C.J.; Sorensen, S.M.; White, H.S.; Palfreyman, M.G. Activity of 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid, a potent antagonist at the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-associated glycine binding site. Mol Pharmacol 1990, 38, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, B.M.; Siegel, B.W.; Slone, A.L.; Harrison, B.L.; Palfreyman, M.G.; Hurt, S.D. [3H]5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid, a novel radioligand labels NMDA receptor-associated glycine binding sites. Eur J Pharmacol 1991, 206, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, D.; Smith, E.C.; Calligaro, D.O.; O'Malley, P.J.; McQuaid, L.A.; Dingledine, R. 5,7-Dichlorokynurenic acid, a potent and selective competitive antagonist of the glycine site on NMDA receptors. Neurosci Lett 1990, 120, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurt, S.D.; Baron, B.M. [3H] 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid, a high affinity ligand for the NMDA receptor glycine regulatory site. J Recept Res 1991, 11, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, R.; Dunn, R.W. Effects of 5,7 dichlorokynurenic acid on conflict, social interaction and plus maze behaviors. Neuropharmacology 1993, 32, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaznik, A.; Palejko, W.; Nazar, M.; Jessa, M. Effects of antagonists at the NMDA receptor complex in two models of anxiety. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1994, 4, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlinák, Z.; Krejci, I. Kynurenic acid and 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acids improve social and object recognition in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995, 120, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, T.; Laughton, P.; Macaulay, A.J.; Hill, R.G.; Kemp, J.A. Electrophysiological characterisation of the antagonist properties of two novel NMDA receptor glycine site antagonists, L-695,902 and L-701,324. Neuropharmacology 1996, 35, 1573–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannhardt, G.; Kohl, B.K. The glycine site on the NMDA receptor: structure-activity relationships and possible therapeutic applications. Curr Med Chem 1998, 5, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotlinska, J.; Liljequist, S. A characterization of anxiolytic-like actions induced by the novel NMDA/glycine site antagonist, L-701,324. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998, 135, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potschka, H.; Löscher, W.; Wlaź, P.; Behl, B.; Hofmann, H.P.; Treiber, H.J.; Szabo, L. LU 73068, a new non-NMDA and glycine/NMDA receptor antagonist: pharmacological characterization and comparison with NBQX and L-701,324 in the kindling model of epilepsy. Br J Pharmacol 1998, 125, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, L.J.; Flatman, K.L.; Hutson, P.H.; Kulagowski, J.J.; Leeson, P.D.; Young, L.; Tricklebank, M.D. The atypical neuroleptic profile of the glycine/N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, L-701,324, in rodents. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 1996, 277, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoph, T.; Reissmüller, E.; Schiene, K.; Englberger, W.; Chizh, B.A. Antiallodynic effects of NMDA glycine(B) antagonists in neuropathic pain: possible peripheral mechanisms. Brain Res 2005, 1048, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, K.R.; Asplund, K.; Carolei, A.; Davis, S.M.; Diener, H.-C.; Kaste, M.; Orgogozo, J.-M.; Whitehead, J. Glycine antagonist (gavestinel) in neuroprotection (GAIN International) in patients with acute stroke: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2000, 355, 1949–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, P.; Franks, N.P.; Dickinson, R. Competitive inhibition at the glycine site of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor mediates xenon neuroprotection against hypoxia-ischemia. Anesthesiology 2010, 112, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benneyworth, M.A.; Basu, A.C.; Coyle, J.T. Discordant behavioral effects of psychotomimetic drugs in mice with altered NMDA receptor function. Psychopharmacology 2011, 213, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley Jr, E.C.; Thompson, J.L.; Levin, B.; Davis, S.; Lees, K.R.; Pittman, J.G.; DeRosa, J.T.; Ordronneau, P.; Brown, D.L.; Sacco, R.L. Gavestinel does not improve outcome after acute intracerebral hemorrhage: an analysis from the GAIN International and GAIN Americas studies. Stroke 2005, 36, 1006–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, R.L.; DeRosa, J.T.; Haley Jr, E.C.; Levin, B.; Ordronneau, P.; Phillips, S.J.; Rundek, T.; Snipes, R.G.; Thompson, J.L.; Investigators, G.A. Glycine antagonist in neuroprotection for patients with acute stroke: GAIN Americas: a randomized controlled trial. Jama 2001, 285, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z. Laquinimod protects against TNF-α-induced attachment of monocytes to human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) by increasing the expression of KLF2. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2020, 1683-1691.

- Nessler, S.; Ott, M.; Wegner, C.; Hayardeny, L.; Ullrich, E.; Bruck, W. Laquinimod suppresses CNS autoimmunity by activation of natural killer cells (P1. 161). Neurology 2015, 84, P1–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, M.; Avendaño-Guzmán, E.; Ullrich, E.; Dreyer, C.; Strauss, J.; Harden, M.; Schön, M.; Schön, M.P.; Bernhardt, G.; Stadelmann, C. Laquinimod, a prototypic quinoline-3-carboxamide and aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, utilizes a CD155-mediated natural killer/dendritic cell interaction to suppress CNS autoimmunity. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]