1. Introduction

Transport interchanges operate as a highly dynamic and complex system with dual functionality as transport nodes and places. Multiple interdependent factors, including transfers among different transport modes, the diversity of user profiles, and the wide range of services available, shape this complexity. As a result, an interchange is not merely a node within the broader transport system but can be considered a network itself where continuous interactions occur between three fundamental components: infrastructure, processes (encompassing operations, logistics, and services), and people.

Therefore, effective management must account for these continuous interactions, ensuring that station design, facility layout, and operational strategies are adaptable to fluctuating passenger demand, ultimately enhancing system performance and user experience. However, despite the crucial role of passengers, management remains primarily focused on transport services and other operational aspects, while research on passenger-centric management is very limited [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] It is necessary to have a holistic vision that links user behaviour and preferences with the use of the space to optimize operational efficiency and service quality at the terminal.

As cities grow and public transportation demand becomes increasingly critical to reducing car dependency, getting efficient and competitive public transportation becomes crucial [

6]. Effective planning is essential for improving both daily management and long-term system performance. In general, it ensures services during periods of peak demand, such as special events or service disruptions. At the same time, at the station level, it helps address growing challenges such as pedestrian flow, bottlenecks, and crowding [

7]. The system aims to provide passengers with the most efficient, safe, and seamless travel experience, including smooth transfers and movement within stations [

6]. Applications related to forecasting for early proactive interventions help enhance transfer time, perceived service quality, and retail revenues [

7]. The ongoing digitalization of public transport has demonstrated the value of

Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) in meeting these requirements through technological solutions [

8]. Moreover,

Automated Passenger Counting (APC) tools enable to collect accurate real-time data [

8], but forecasting remains a key area that requires further development.

This paper analyzes passenger flow and stance within a multimodal transport hub. It aims to develop a method for forecasting user occupancy in critical station areas using a prediction model based on the

Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM) procedure. It has been widely used in the transportation field, demonstrating strong performance and providing valuable insights [

9]. This approach enhances data-driven strategies for improving service quality through dynamic management. By examining movement patterns, occupancy trends, and forecasted results, this research aims to provide valuable insights that support a more user-centric understanding of passengers’ movements and station dynamics.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature for the main concepts and definitions implied in the study.

Section 3 describes the proposed methodology, which is divided into phases and developed from the general approach to the application in the case study. Using the Moncloa Interchange as a case study, one of the key multimodal stations in Madrid’s transport network that serves more than 200,000 passengers daily.

Section 4 presents the results related to the real time APC installed system and occupancy forecasting using the LSTM prediction model.

Section 5 discusses the achievements and limitations of the study, analyses the results and proposes dynamic strategies management for multimodal transport stations. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper by discussing its contributions to existing literature and proposes possible future research lines.

2. Literature Review

Transport interchanges are key nodes within the transport network, playing a crucial role in facilitating intermodal connectivity. The primary objective of these nodes is to minimize the penalties associated with transfers between different transport modes, by providing suitable infrastructure that optimizes both the comfort during the transfer process and in the waiting areas [

10,

11]. This is achieved through the improvement of transfer and waiting areas, as well as offering a range of complementary services that enhance the user experience and make the system more attractive overall. Given that in large European cities such as Madrid, a high percentage of trips involve at least one transfer, reducing the penalties associated with this process has a significant impact on the perception of the public transport system, contributing to making it more competitive compared to the use of private vehicles [

12]. To manage a high volume of users, these infrastructures are typically large in scale and represent landmarks of the transport network. As primary points of interaction between users and the system, interchanges significantly influence the public perception of the public transport system [

13]. Given their critical role in passenger movement and their spatial potential, it is essential that interchanges incorporate a high degree of functional diversity to ensure seamless integration into the surrounding urban environment while enhancing the overall user experience [

13,

14]. This integration enhances both transport perception and urban value, yielding positive economic, social, and environmental benefits [

15].

Consequently, transport interchanges serve a dual function: on the one hand, they act as transport nodes, facilitating movement and transfers between different modes; on the other hand, they also serve as places to wait and engage in activities related to daily mobility [

15,

16]. This duality adds complexity to their management, as it involves the passenger flow, presence, and stay. Total integration encompasses both physical and operational aspects, requiring the coordination of three interdependent elements that interact dynamically: infrastructure, processes, and passengers [

17].

The infrastructure dictates the available space for the general operation of the interchange. The main characteristic is the fixed typology and dimensions. Its structural layout and design determine the arrangement of facility distribution (such as commercial areas, amenities, and waiting zones) and shape passenger flow, congestion, and dwell time (through paths to entrances, exits, transfers, and stay areas) [

2].

The processes are defined based on the specific functionality of each space within the interchange, the delivery of services, and overall management. Certain elements remain constant, such as design constraints, capacity, platforms, fixed equipment, facilities, and space distribution and allocation. In contrast, operational aspects are dynamic, influenced by disruptions in the surrounding urban environment, unforeseen events, incidents, emergencies, fluctuations in transportation services, and variations in passenger demand.

Passengers are the primary actors who interact with and experience the previously mentioned aspects. The experience varies for everyone, as Bertolini exposed different people perform different actions [

16,

18]. Individuals engage in different actions based on their specific needs and circumstances. Factors such as physical condition, trip purpose, age, walking speed, personal preferences, and route choices—combined with station design and the operational plan, including service schedules, frequencies, and waiting times—shape individual behavior within the interchange [

2].

The interdependent relationship among these three aspects also highlights that effective management must be integrated with the station’s structure and facility layout, which serve as the foundation for path organization, operation and physically delimited passenger behavior [

2,

19].

The integrated management of transport interchanges, aligned with service quality, is essential in enhancing the user experience [

20]. Literature includes different studies and guidelines from industry authorities that have identified key principles and characteristics to consider in this management, many of which share common elements. Following the conceptual dimensions proposed by Bertolini,

transport node,

place, and

both [

16],

Table 1 presents a summary of these principles, categorized by dimension, as outlined by various authors in the literature.

As observed, in addition to aspects specifically related to transportation, most are linked to the stay within the interchange and the conditions that define it. This stay can be brief, limited only to the time required for transfer, or more prolonged due to waiting times or the performance of other activities.

Most authors agree that the aspects related to the conception of the interchange as a place and a node-place are determined by factors such as accessibility, design, spatial layout, and capacity, as well as safety, security, and the availability of services, which depend on the organization of facilities. In this regard, infrastructure and associated occupancy play a crucial role in evaluating these factors, and their effective management can significantly enhance service quality.

In this context, the main areas of transport interchanges, beyond access and exit points, include connecting corridors, halls, and platforms for each mode of transportation. These spaces are essential for facilitating transfers, regulating passenger flows, and crucial for analyzing passenger characteristics [

2]. However, the research findings indicate that waiting areas and spaces for services and amenities, such as commercial areas, have a significant impact on the perception of the interchange’s level of service [

18,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

From a user-centric perspective, service evaluation has identified that the most influential factor for users is related to transfer conditions, particularly regarding the physical structures involved and the distances that must be covered to switch between modes [

24,

27]. These findings are further supported by other studies highlighting the importance of interchange layout and internal connections [

31], as well as the walking environment [

32], the transfer environment, and important facilities, which collectively have a significant impact on users’ perception and rating of service quality [

25].

The optimization of operations, focused on managing transportation services in terms of schedules, frequencies, and coordination, among other aspects, has traditionally been a central axis for improving the evaluation of service quality in transport interchanges. However, the management of passengers, their behaviors, and their interaction with the infrastructure has lagged behind, despite their fundamental role in the process. Indicators such as capacity usage and passenger density are among the most relevant for assessing the performance of the facility configuration scheme, highlighting the need to prioritize user management [

2,

33]. Additionally, as identified by Zhang et al. [

2], aligning general decision-making methods with the practical management of stations—considering physical infrastructure, available services, demand, and passenger needs—remains an existing research gap. Addressing these issues effectively as the first step requires accurately identifying passenger presence within the interchange, when combined with passenger flow analysis, which enables the detection of behavioral patterns, critical event causes, passenger bottlenecks, and space usage demand tendencies. All of these are essential for implementing data-driven strategies to optimize operational management.

The availability of real-time data is valuable and relevant, but it does not guarantee fully efficient management. The evolution of ITS technologies, with the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, enables the development of more sophisticated tools that address new challenges in data processing and exploitation, adding high value to mobility services for both passengers and operators [

8,

34]. In this context, the logical next step is the ability to foresee the future evolution of this data, that is, to predict passenger occupancy or presence levels within the stations. Anticipating trends and possible scenarios would enable the optimization of planning, improve responses to events or variations, reduce the randomness of operations, prevent unforeseen situations, and generally control factors that may negatively affect service quality. Thus, occupancy prediction becomes an essential component of real-time management in transport systems, as highlighted by Vieira et al [

3,

35].

In this context, it has been identified that passenger occupancy forecasting plays a pivotal role in traveler satisfaction, especially in transport vehicles, which has been extensively researched [

8,

36,

37,

38]. However, regarding stations, there has been less research. Studies have focused on stations with a single predominant mode of transport, such as smaller-scale bus stops [

35], and larger ones for metro or railway stations [

39], Despite these studies representing a good starting point, they can be expanded or adapted to multimodal stations, and specific research on this topic is limited. In addition, most existing research has utilized smart card datasets, which only provide information on entry/exit validation at stations and limit the study by not considering passenger flow within the area. This results in a lack of predictive analysis in multimodal stations.

To address these gaps, this paper focuses on analyzing passenger flow within a transport interchange, collecting specific data through an internal APC system to forecast passenger occupancy. The outputs enable the evaluation of the service level and the proposal of data-driven tool to manage station spaces dynamically, optimizing station operations and enhancing the user experience.

3. Materials and Methods

This methodology outlines the steps to predict occupancy in a transport interchange based on passenger flow within its spaces, allowing for the evaluation of service levels and the definition of strategies to enhance its management.

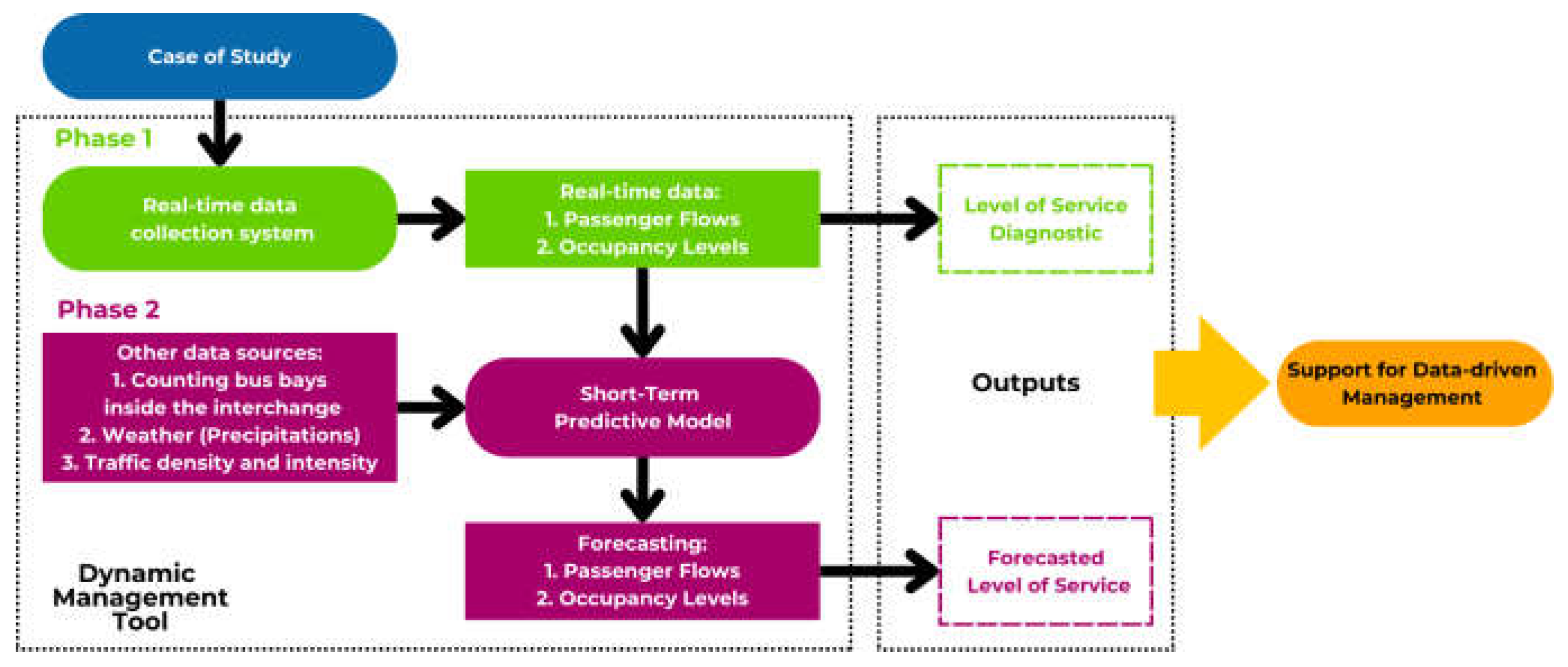

Figure 1 illustrates the complete workflow to be implemented.

The process begins with the selection of a case study that exemplifies the importance of integrated management in complex nodes within the transport system. Next, for phase 1 a distributed

Automatic Passenger Counting (APC) [

40] system is implemented to capture real-time passenger flow data, which is then used to calculate occupancy levels and provide a continuous assessment of service conditions within the facility. This data is subsequently utilized in phase 2 to train a neural network-based prediction model designed to anticipate over a short-term horizon of up to 24 hours occupancy trends in relation to the corresponding service levels. The objective of this approach is to leverage the predictive model as a dynamic management tool, enabling the anticipation of service quality variations and the proactive planning of operational and contingency strategies. This ensures an optimized interchange performance with a standardized and efficient level of service.

This section begins with an explanation of the selected case study and the characteristics that make it suitable for this analysis. Next, the functioning of the implemented APC system for data capture is detailed, highlighting its advantages compared to other approaches. The calculation of occupancy is explained, and finally, the definition of the predictive model is described, along with its configuration, the variables used, and the validation process.

3.1. Setting of the Case Study for Validation

The selection of the case study aligns with the research objective, focusing on passenger presence and flows within transport stations with complex management requirements. The selected station or transport node should integrate diverse functionalities, including services and facilities for the transfer and use of space. The Moncloa interchange fulfils the requirements of a good case study. It is a key transportation hub in Madrid, situated on the city’s border, connecting the capital with the metropolitan northwest corridor, one of the most densely populated and affluent areas in the Madrid Metropolitan Area. Its transport node connects metropolitan buses with urban bus lines and metro. Its facilities serve 55 metropolitan bus lines, serving nearly 100,000 passengers daily, with over 350 buss services during the morning peak hours. Additionally, 19 urban bus lines connect to the interchange, transporting approximately 120,000 passengers per day. The Moncloa Metro station is the busiest in the network, with over 115,000 daily validations, served by two lines: Line 3, which connects to the city center, and Line 6 (the Circular) that distributes passengers among all the city’s periphery and links to seven other metropolitan bus interchanges [

41,

42,

43].

Studying the level of service at Moncloa Interchange is crucial due to its distinctive characteristics, including its large scale, strategic location, functional diversity, and high passenger volume. These factors make it an ideal case study for analyzing occupancy and passenger dynamics across areas with different functionalities, both for transfers and additional on-site activities.

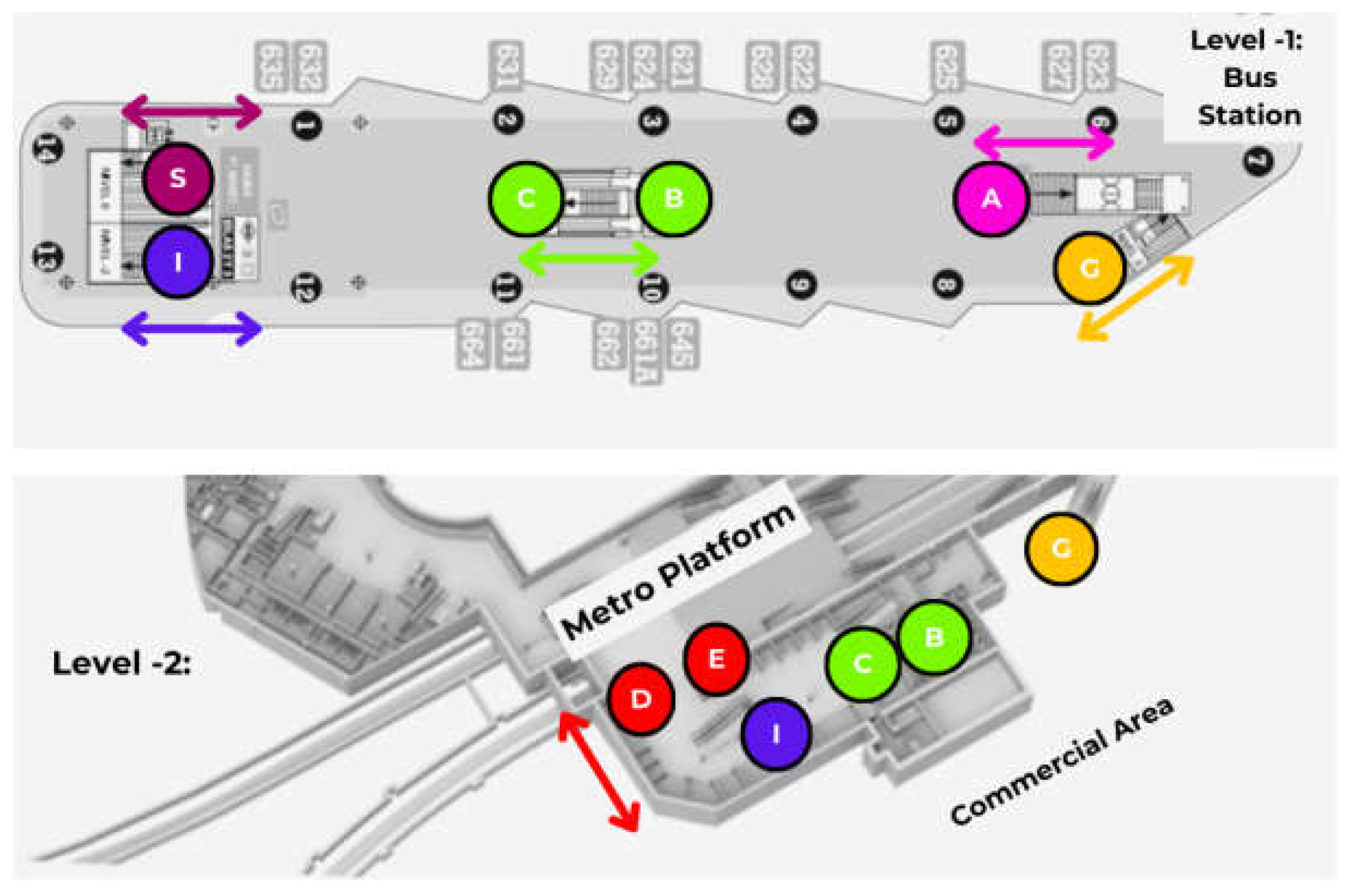

The interchange consists of two buildings: the older one (Module A) and a newer one (Module B), which was constructed as part of an expansion to accommodate increasing demand. Both buildings are connected by transfer corridors that facilitate movement between them and various transportation platforms. Module A concentrates most passenger entries and exits at the interchange, as well as the busiest connection points in terms of passenger flow [

41]. It has two overlapping levels interconnected by both escalators and conventional stairs. The -1 level spans an area of 2,200 m², featuring 14 bus bays and a central waiting area. The -2 level is smaller -approximately 1,100 m²- and corresponds to the commercial area and connection to the metro station. This commercial area comprises approximately 30 establishments offering food, retail, and other services [

41]. It is a good example of a multifunction station, aligned with the study objective of analyzing the interchange not only as a transportation hub but also as an integrated urban space.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of spaces with the access points marked and differentiated by color. These points correspond to corridors, pedestrian ramps, and staircases, and the green and blue ones represent the connections between the two levels.

3.2. Phase 1: Real-Time Data Collection System

This study proposes calculating occupancy based on the adaptation of the basic principle of energy conservation, as outlined in Equation 1 [

44]. This indicates that the occupancy level in a location at a given time is the result of the initial presence at the start of that period, plus the difference between incoming and outgoing flows during the interval. To accurately calculate the passenger numbers of entries and exits, it is necessary to monitor all access points in a reliable manner to minimize errors.

Occupancy in transport systems has often been estimated using

Automatic Fare Collection (AFC), which has proven effective for buses and small stations where all users validate payment at their entry. However, counting in larger or multimodal stations, such as interchanges, poses a challenge due to their open-access nature and the absence of the AFC devices at access points. While combining validation data from different transport modes could help, it does not fully address the problem, as these facilities also attract not only passengers using transport services but also visitors looking for the station’s commercial and service areas [

4], making it difficult to estimate the duration of their stay accurately and, consequently, their impact on overall occupancy.

To address this challenge, a real-time data collection APC system was designed and installed at the Moncloa Transport Interchange. This video-based system combines detection and trajectory methods for real-time passenger counting [

6]. Detection techniques identify targets using region classifiers and feature subtraction, while trajectory methods track the movement of objects [

6,

45]. It uses cameras with edge-computing AI models based on convolutional neural networks to detect and count people in specified directions through image classification and segmentation [

46]. The system tracks bidirectional flows: ’entry’ and ’exit’.

This implementation enables the precise spatial delimitation of each zone at the interchange and provides a detailed understanding of passenger movement directions and presence levels over time. Moreover, this approach is cost-effective and has easy functionality, since complex data preprocessing is not required to obtain the final measures.

For its deployment at the Moncloa Interchange, the five connection and access points to Module A identified in

Figure 1 were evaluated based on their spatial dimensions and physical conditions to determine the number, placement, and angles of sensors required to ensure full coverage of the area. As a result, real-time passenger flow data are collected at all access and egress points within the study area and validated by comparing them with manual counts taken during peak hours on several days, including weekdays and weekends, ensuring a margin of error below 2%. The space occupancy is determined by applying Equation 1. These data will then be used to train the predictive model.

3.3. Phase 2: Short-Term Predictive Model

The real-time data collected on phase 1 is used to create a historical dataset of these variables and then used to train a predictive model. This model aims to predict short-term occupancy levels, thereby providing a supportive tool for the dynamic management of the interchange.

Short and long-term predictions in transportation have been identified essentially as a time series forecasting problem, where exogenous explanatory variables (such as weather, land use, transport validation, and traffic) are used to conduct more comprehensive analyses. These variables allow for the use of a larger set of correlated data with varying degrees of influence [

39], and enables the adoption of a generalized approach to obtain specific and detailed results, focused on a particular variable. As illustrated in

Figure 1, in this phase, different data sources are integrated into the process.

Several prediction model approaches have demonstrated their ability to capture both the stationarity and periodicity of real-time data in transportation [

47]. However, several studies have highlighted that

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [

48] Recurrent Neural Networks are a promising approach. This has been extensively applied in the transportation domain, particularly for predicting passenger demand, traffic flow, and occupancy levels [

9]. LSTM networks have shown strong capabilities in time series forecasting and have outperformed other methods [

39,

49] demonstrating high performance in capturing long-range dependencies due to their ability to overcome the vanishing gradient problem, which commonly arises during the training of traditional RNNs, especially when long time lags are involved in the prediction horizon [

50].

Consequently, an LSTM model based on time series is selected for this study. The datasets used will be time series, meaning that the data will be organized according to their chronological sequence, which is suitable for trend analysis and predicting future behaviors, as it captures the temporal dependence between observations.

The following subsections provide detailed definitions for the application and validation of the model.

3.3.1. Data Used for Modeling

According to the definition and requirements set to optimize the performance of the selected model, along with the historical data on passenger flow and occupancy captured by the APC system, it is useful to incorporate other data sources that influence or are related to these target variables.

LSTM models learn from temporal sequences and improve its performance when input variables are relevant and have a significant relationship or influence on the target variable. This makes the models more effective to capture patterns and temporal relationships between the data [

8,

48].

Passenger flows within transport stations are influenced by factors such as weather conditions and traffic congestion in surrounding areas. Similarly, station occupancy is directly linked to the boarding and alighting processes across different transport modes operating at the station [

39]. Based on this information, this study integrates an additional set of heterogeneous data sources, including time series of traffic conditions around the interchange, entries and exits of a transport mode, weather variables, and variables representing calendar and periodic patterns, as these trends strongly influence mobility.

Traffic conditions are collected from twenty sensors measuring traffic intensity and density at critical ramps connecting to other roads along the A6 Corridor, which is the main transportation artery near the interchange. Entry and exit data for the 14 bus bays at Module A, as well as precipitation data from the city’s meteorological stations. Since time-based and seasonal factors highly influence interchange demand due to their connection with educational institutions, workplaces, and tourist attractions, Boolean and sinusoidal identifier variables are included to represent these variations and identify daily and weekly patterns, as well as holidays and term times.

Table 2 provides a summary of the variables used, along with specific information and data sources.

3.3.2. Data Preprocessing

The effective integration of heterogeneous data sources requires conducting a preliminary analysis of their characteristics, such as format and sampling frequency, and standardizing common parameters according to the requirements set for modeling with an LSTM neural network. This implies that all time series must have the same sampling frequency and must not contain any missing values.

Moreover, the LSTM model is multivariate and predicts the activity of all target variables simultaneously. To enhance performance, applying standardization or normalization to the aggregated dataset is considered good practice. That standardization may not significantly improve the model’s ability to forecast low values, but it is necessary when predicting high values to achieve better results [

50].

For the study, since the sampling rate must be adjusted to the resolution of the time series with the lowest granularity, it was set to 1 hour, which was the least disaggregated level found among the datasets, and the others were adjusted accordingly. This definition means that each day in the final time series used in the model is represented by 24 records, which implies that the prediction will be made by day, covering the next 24 periods.

A two-steps gap-filling method was applied to the missing data, using average values:

• First step: Each missing value in a variable was filled with the average of all its values that shared the same temporal characteristics: "instant within the day," "instant within the week," "term time (primary)," "term time (secondary)," "term time (higher)," "weekend or holiday," and "working day next to a holiday."

• Second step: Any remaining gaps were filled based on a more simplified set of variables: "instant within the day," "instant within the week," and "holiday or not."

Additionally, to avoid the accumulation of errors, the occupancy is set to zero daily when the interchange is closed (from 00:00 to 06:00). With these adjustments, the final time series ensures data consistency and eliminates discrepancies that could affect the models’ performance and accuracy.

3.4. Model Training and Validation

The occupancy prediction in Module A of the Moncloa Transport Interchange is made using the time series obtained after data preprocessing as input. The model is designed to use data from the past groups of 24 records to predict the values for the next 24 hours. This approach corresponds to short-term prediction due to the limited forecast horizon.

For the case study, the analysis period spans from June 25, 2024, to February 10, 2025. To ensure similar conditions to the real interchange operation, the available data was divided into three consecutive sets, following the principle that the model can only learn from past events:

• Training set: Used to adjust the model parameters and minimize prediction error, corresponds to the period spanning from June 25, 2024, to December 3, 2024 (approximately 5.5 months).

• Validation set: Used to fine-tune the hyperparameters during training, allowing the model to generalize to new data, covering the period from December 4, 2024, to January 18, 2025 (approximately 1.5 months).

• Testing set: Used for an unbiased evaluation of the model, runs from January 19, 2025, to February 10, 2025 (approximately 1 month).

After the execution phase, with the results obtained for each set, the loss function is used to evaluate the model’s performance. The Loss Function [

51] quantifies the error between predicted and actual values using variance.

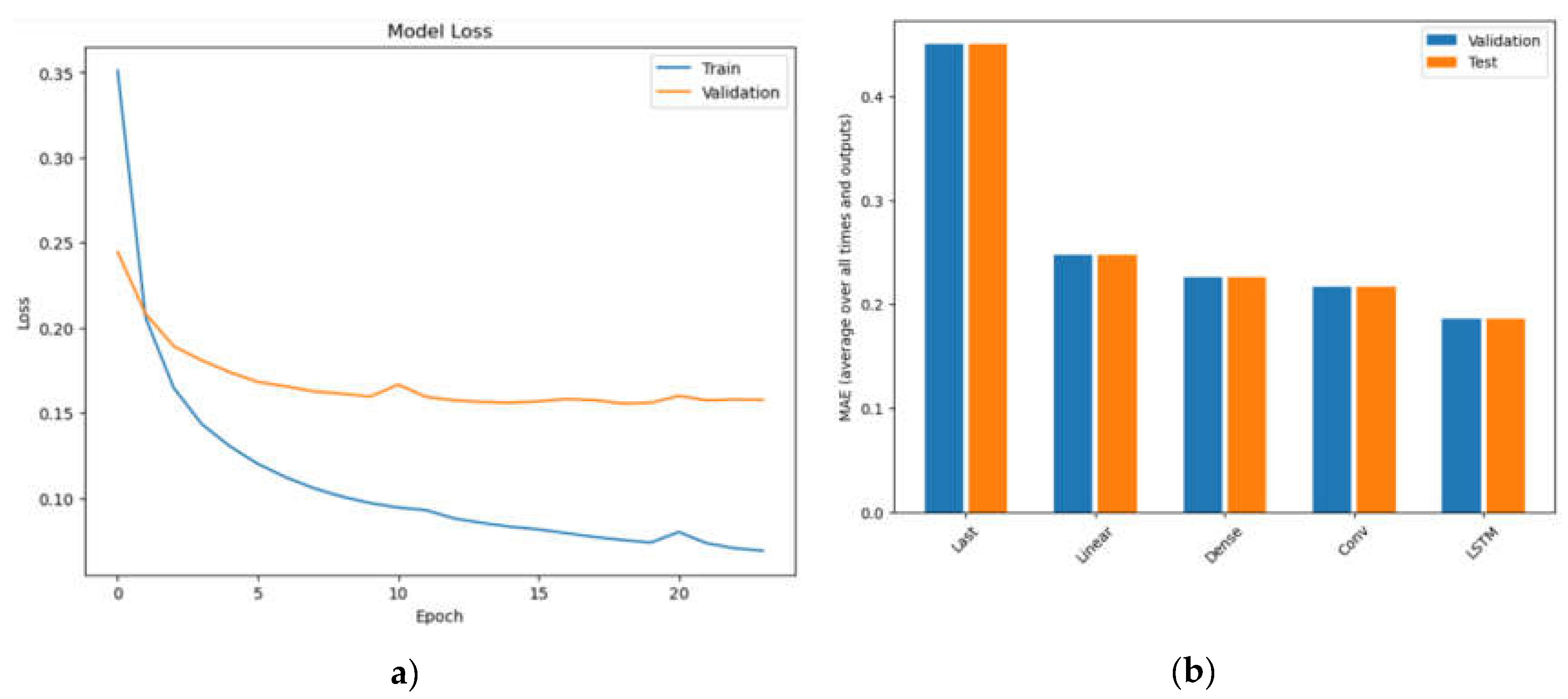

Figure 3.a. illustrates the evolution of training and validation losses throughout the training process. As observed, the training loss remains below 0.10, while the validation Loss value remains under 0.20, indicating a minimal value that suggests the model effectively fits the training data. Although the validation loss is slightly higher, it remains low, implying good generalization, which is also further supported by the stabilization of both loss curves.

Meanwhile,

Figure 3.b. compares the Validation and Test Losses performance of the LSTM model against alternative approaches, including a Baseline Method, a Linear Model, a Dense Neural Network, and a Convolutional Neural Network. This is performed by calculating the

Median Absolute Error (MAE) using Equation 2, where

represents the forecasted value and

the actual value [

50]. It demonstrates that the LSTM achieves the lowest MAE values in both cases and outperforms all other methods, yielding the best performance and reinforcing the suitability of the model for this study.

4. Results

The results are presented according to two distinct analyses as shown in

Figure 1: the diagnostic of the

Level of Service (LOS) based on real-time data and the assessment of the forecasted values.

Related to the evaluation of real-time data captured by the installed APC system, as well as the calculation of occupancy based on these values. Focus on the predictions generated by the LSTM model using the defined time series, which integrates the mentioned data, and the additional datasets explained. Both sets of results are analyzed under the guidelines of LOS, both in real-time and as predicted. Since all users within transport stations are pedestrians, we apply the LOS criteria for pedestrian facilities of the

Highway Capacity Manual [

52] to classify the station-level service according to the average space per person (m²/person). Using the dimensions of each area in the Moncloa Interchange, the corresponding number of people per area dimension is calculated for each level, yielding the results presented in

Table 3.

The average space criteria column indicates the required space per person in an area to achieve the corresponding LOS. The other two columns show the calculated number of people that can occupy an area with those specific dimensions to ensure the corresponding LOS is maintained. In the figures below, the LOS is represented by a color overlay on the graphs, with the corresponding letter for each level displayed on the right margin.

4.1. Level of Service Diagnostic: Real-Time Observations

Real-time results provide a preliminary diagnosis of the service levels at the interchange based on occupancy. Furthermore, these illustrate the operation of the distributed APC system by the hourly evolution of the calculated occupancy using real-time passenger flow data captured at the access points. This occupancy analysis is plotted, describing the interchange operation and identifying recurring patterns. It is essential for detecting potential trends that could be crucial for management, which can later be validated with the results of the predictive model.

This analysis is presented for both weekday and weekend days to compare variations and the influence of time on service demand trends, thereby providing a comprehensive view of the station’s operation in different contexts.

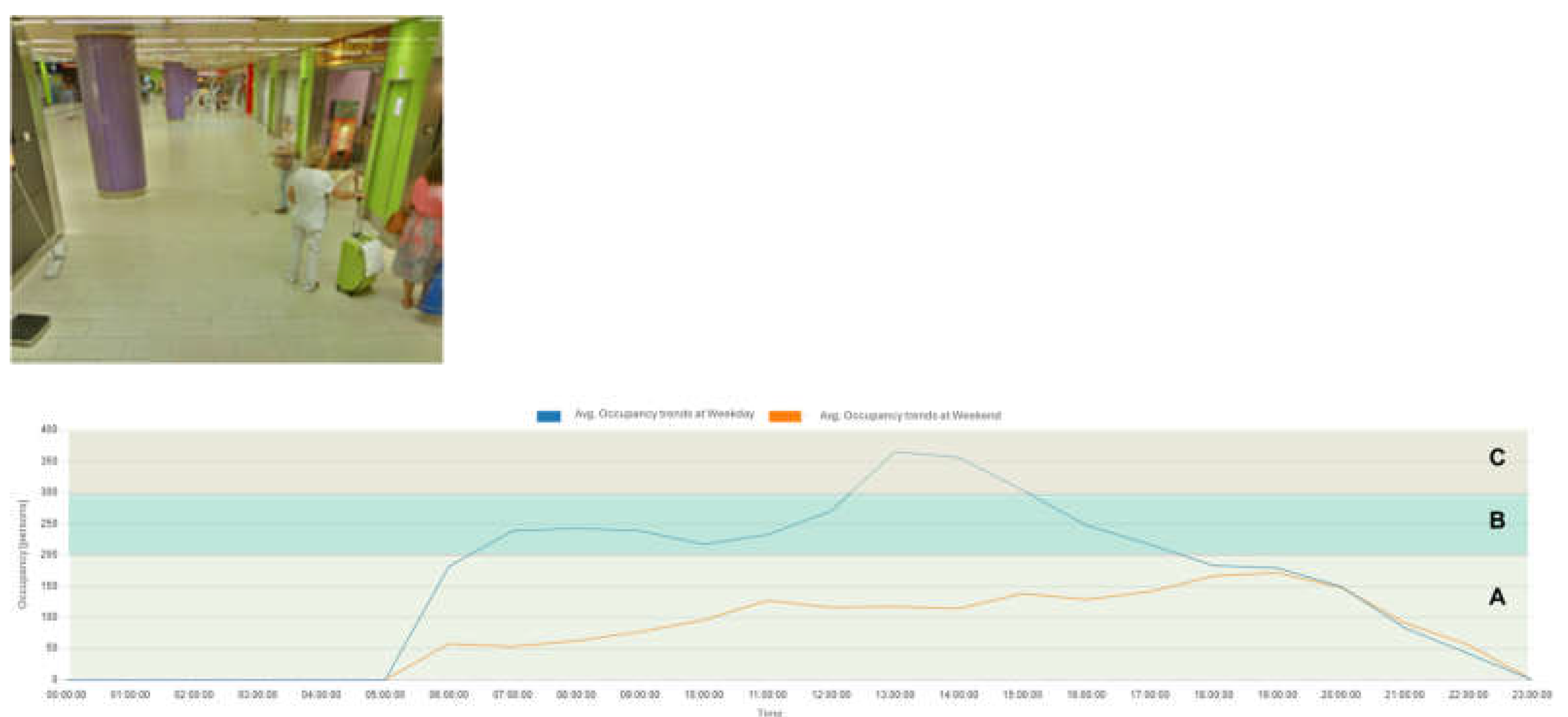

Figure 4 presents the results obtained from the data captured at level -1 (bus station) along with a photo of the place. In line with the known demand data for the Moncloa Interchange [

41], it is observed that the highest occupancy peak occurs between 07:00 and 08:00, when the most significant number of passengers use the interchange to enter or leave Madrid, mainly for commuting to work or study. It is also observed that return trips are almost evenly distributed throughout the day, as the occupancy remains at similar levels. Only two small peaks are identified, around 14:00 and 17:00, when most users typically concentrate on their return journey. Regarding the weekend, it is noticeable that the morning peak disappears, and instead, occupancy gradually increases, remaining constant throughout the day, indicating that demand is more widespread over time.

Regarding the LOS rating, as shown in

Table 3, LOS most of the time remains between A and B for both days, with only slight dips into level C. However, during the morning peak, occupancy rises enough to temporarily reach service level D, where walking speed and the ability to overtake slower pedestrians are restricted. This signals an initial conflict situation that management should consider addressing.

Figure 5 presents the results for Level -2 (Commercial Area) and its corresponding photo. During weekdays, the highest occupancy occurs during lunch hours, between 13:00 and 15:00, which is expected due to the services available in this area, such as cafeterias and restaurants. A slight peak is also observed in the early morning hours, coinciding with Level -1. This peak is considerably smaller, which is understandable, as users are generally in a hurry and have less time to engage in additional activities.

A notable difference is observed between the values on weekdays and weekends. This indicates that services in this area have considerably lower demand at weekends, partly because many of the facilities are closed as fewer passengers use the interchange. In general, the number of users is significantly lower compared to the other level.

LOS in this Level -2 predominantly remains between A and B for both days, but again, peak demand deteriorates the situation, but less than in Level -1.

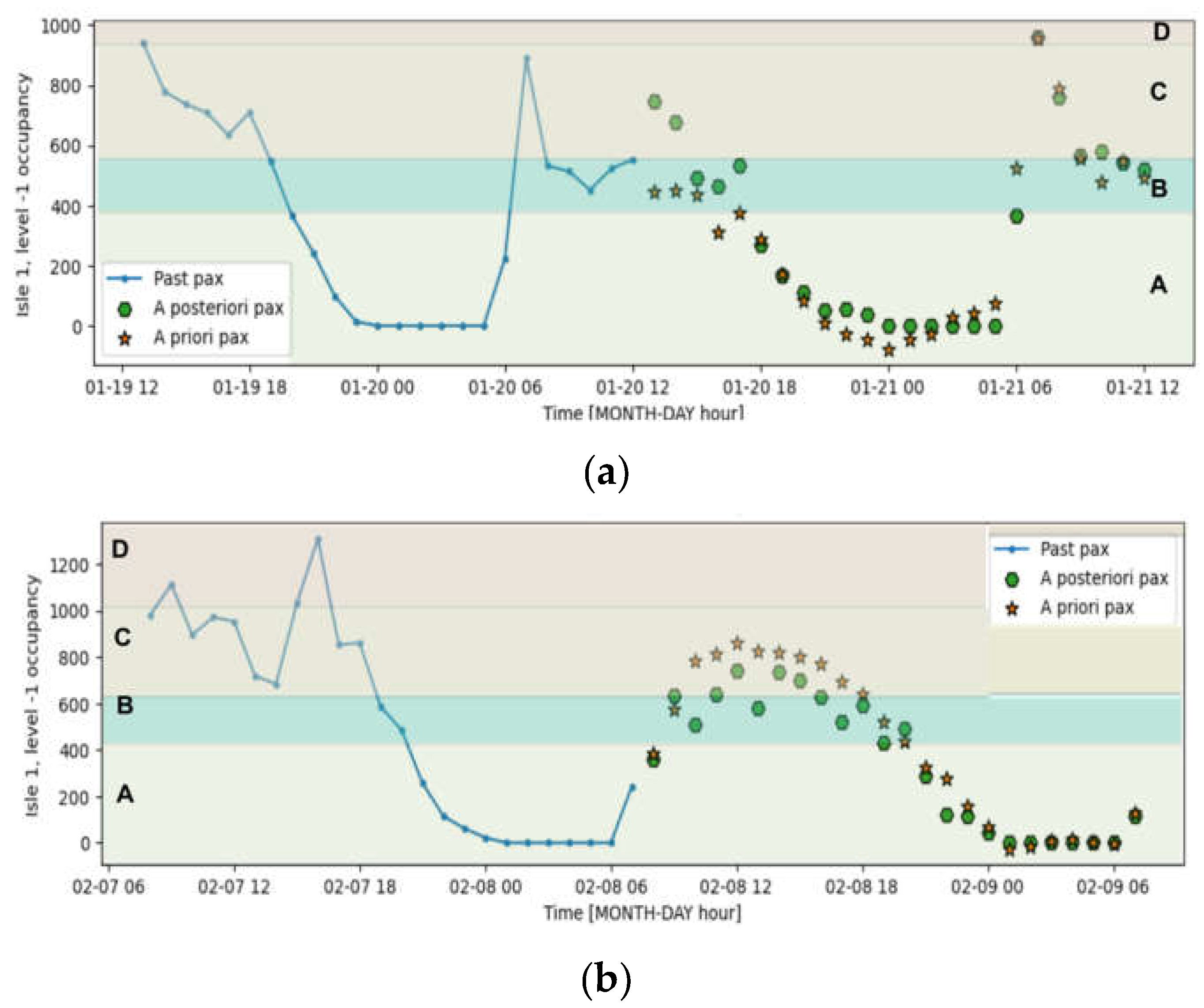

4.2. Forescating Level of Service: Predicted Values

The results obtained from the predictive model for the occupancy values are presented in the following figures. In each of them, the previous 24 hours are plotted alongside the predicted 24 hours, including both the predicted and actual values. This representation facilitates the analysis of the model’s performance by graphically comparing the similarity between the actual and predicted data and determining whether the model can follow the expected trend. On the other hand, LOS analysis enables the evaluation of how well the prediction aligns with the actual levels, helping to identify any discrepancies.

Figure 6 presents the outcomes for two different days and time ranges at Level -1. The results demonstrate that the model is sensitive to the day type and effectively distinguishes different days. The model correctly adjusts its forecasts for non-working days following working days.

Overall, the model successfully follows the expected patterns in the data, accurately detecting peaks, troughs, and the general shape of the trends, despite a certain degree of error. Furthermore, even with this margin of error, the predicted results align with the same LOS levels as the actual data, indicating their predictive accuracy.

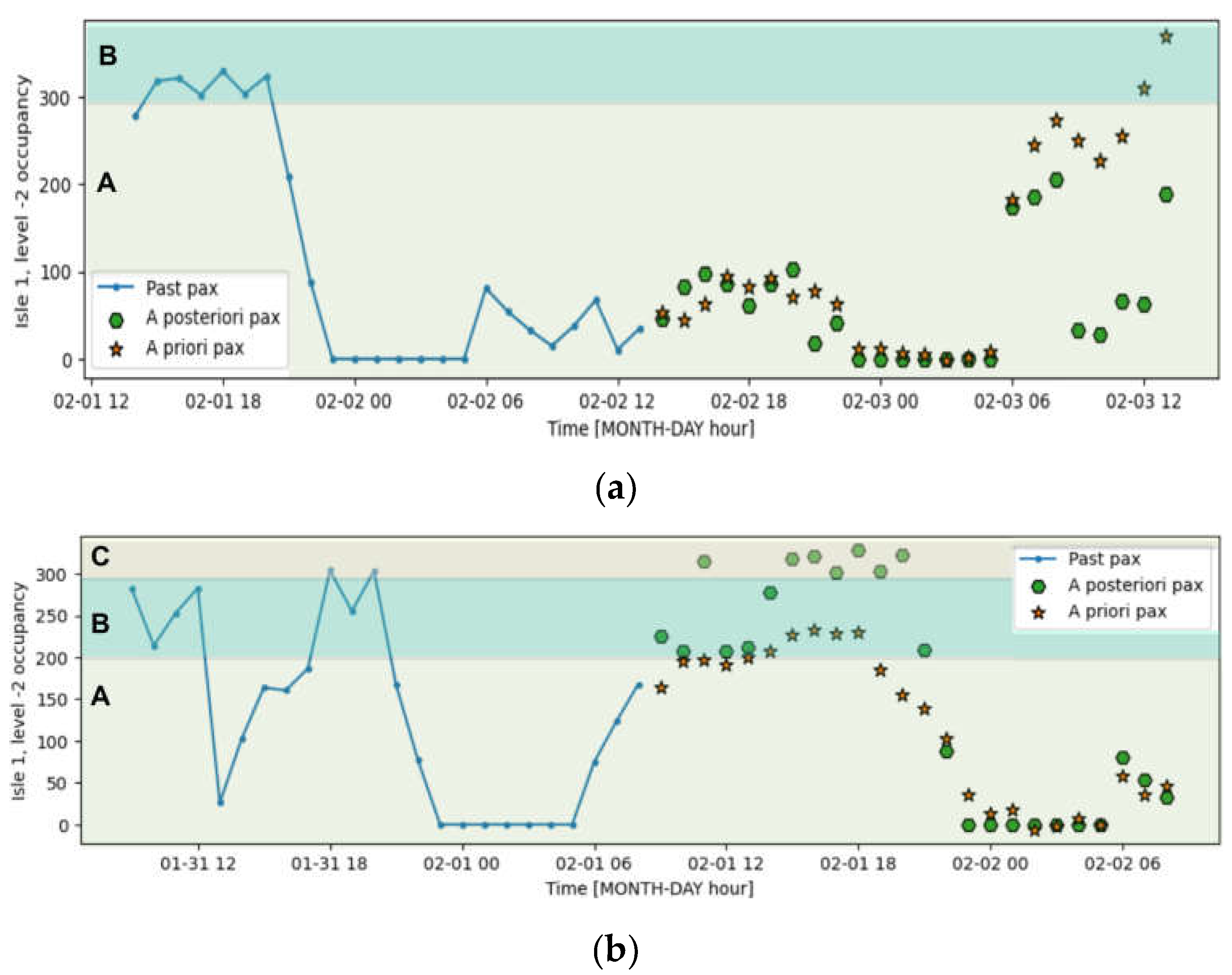

Figure 7 illustrates the forecast for two different days at Level -2.

As expected, the number of users at this level is significantly lower compared to level -1, and the prediction reflects this as well. The forecast consistently follows the trends of real values, but the margin of error is higher in this case. The model can detect the maximum and minimum peaks, but it tends to exaggerate the maximum values, deviating more from the actual ones. This causes a slight error when defining the LOS, although it is only observed between two consecutive levels, which does not represent a significant difference.

Finally, thanks to the configuration of setting occupancy at zero in the close period, the model successfully identifies the start of each different day. The forecast is more accurate for the bus station level. In general, the model manages to represent with accuracy the occupancy level trends for the different areas of Module A, predicting properly the expected LOS.

5. Discussion

The results confirm the possibility of integrating heterogeneous data sources, including real-time flows and historical passenger counting data, to predict users’ movements in a transport interchange. This integration achieved the objective of monitoring and predicting the service level in terms of passenger flow and occupancy. The strong performance of the prediction model demonstrates that the processes developed at each step of the methodology were appropriate and aligned with the research goals.

It is demonstrated that using multiple data sources has synergies despite differences in dataset characteristics. Data needs to be homogenized using various techniques, such as resampling and interpolation, implemented during the preprocessing phase. Although these processes may result in information loss due to variables initially recorded at a higher granularity, the main patterns, which are the focus of this type of study, are maintained and can still be identified. This means that the most relevant trends, which have the most significant influence on the interchange’s level of service, remain unchanged. While some very specific patterns may have been smoothed or even lost due to the adjustment methods, this does not significantly affect the results or notably impact the model’s performance.

The model’s performance validated using data from Moncloa Interchange demonstrates consistency between real-time data and predicted values, indicating the model’s reliability. The predicted occupancy levels closely follow the trends observed in real-time measurements, maintaining similar patterns during peak and off-peak hours. This alignment indicates that the model accurately captures the underlying dynamics of passenger flow and station usage, as well as the impact of external factors such as weather and surrounding traffic conditions. The two interchange functions were analyzed (real-time and forecast), concluding that the primary function of the Moncloa Interchange is as a transport node rather than as a space where passengers stay. However, it also reveals an essential commercial function associated with shops and services during specific periods, especially on weekdays. This conclusion is based on the observation that occupancy levels in commercial areas remain relatively low despite the high volume of passengers passing through the infrastructure. These results could differ if the model were applied to other types of interchanges, such as rail stations, where waiting time for long-distance transport services is higher, and the function as a place could be more relevant.

On the other hand, the results validate that the selection of data for forecasting was appropriate and accurate, as the data used has a significant influence on the target variable, helping ensure that the predictions closely align with the actual values. Moreover, the adjustments and modifications made during the data preprocessing phase were crucial in increasing the efficiency of model execution, reflected in that training took less than a minute on a computer equipped with a Tesla T1 TPU. Related to the APC based on on-site observation or physical measurement, reinforce the model’s performance by its capture data method that minimize errors associated with interference and selection bias that are common when using signal analysis (e.g., WiFi, Bluetooth) or GPS triangulation methods [

7,

53,

54]. Other advantages include the short data processing time due to edge computing, the simplicity of system configuration and calibration, and the operational independence of the components involved.

The study has a limited scope because the test lasted only seven and a half months, from the installation of the distributed APC system to the completion of this study. This resulted in 5,520 observations, which were sufficient for testing and validating the model for short-term predictions yielding strong results, as demonstrated by the achieved performance and accuracy.

The APC system may deliver systematic errors as it relies on sensors and on-premises equipment, which potentially may lead to biases in occupancy estimation. However, these misvalues can be identified and mitigated using the preprocessing techniques implemented in phase 2. In summary, the low error margins between predicted and actual values reinforce the model’s accuracy, confirming that the selected input variables are appropriate and contribute meaningfully to the forecasting process.

The results validate the model’s potential for applications in the transportation field, enabling it to be used as a tool for proactive and planned management of station occupancy, thereby maintaining service within adequate LOS ranges.

Data-Driven Tool for Dynamic Management of Transport Interchanges

The tool enhances the comprehensive management of transport interchanges by monitoring the LOS, enabling efficient operations and improving the perceived service quality by users.

The implemented integration of the APC system and the predictive model serves as a powerful approach for enabling decision-makers to implement data-driven strategies that address the two key pillars of immediate and long-term operation: real-time monitoring and forecasting for anticipating and mitigating potential issues. Proactive management, along with advance planning and the definition of contingency measures, enables the identification of periods when situations that negatively impact service may arise, allowing them to be minimized or even eliminated, thereby ensuring the operation remains in optimal condition.

Specific dynamic management strategies for the interchange based on the results can be implemented by actions related to five key aspects, all aimed at improving the operational efficiency of the transport hub: information management, space optimization, passenger flow control, development and enhancement of services and amenities, and effective emergency response [

3]. Particularly, emergency response is a critical aspect due to space limitations and high passenger volumes. In this regard, having predictive data enables the design of more effective contingency plans to ensure user safety, optimize evacuation procedures, and improve the handling of critical situations [

53].

Having real time and predictive data would strengthen the efficiency of traditional strategies by making them more informed and accurate. For example, optimizing the frequency adjustment of transport services for different modes during peak and off-peak periods, and adapting it to specific daily patterns rather than relying on generalized demand trends. This would optimize resources and improve the overall cost-effectiveness of the service.

For user management within the station, predicting the number of people based on passenger flow enables the anticipation of potential congestion periods. This enables the prior planning of corrective measures and contingency strategies to prevent or manage these situations as efficiently as possible. In the literature, this approach is known as

congestion or crowd management, which involves planning and implementing actions to ensure the orderly movement of crowds within an infrastructure [

3]. In the crowd management framework, two types of strategies can be implemented. On one hand,

hard management strategies refer to mandatory measures for pedestrians, like flow separation through signage, designation of specific access and exit points with staff guiding users, or restricted access to certain areas during specific time slots. On the other hand,

soft management strategies consist of recommendations that users can follow voluntarily, such as suggested optimal travel times and itineraries to avoid peak congestion periods [

4].

Among the operational strategies that could be implemented to manage demand in real time are passenger metering (controlling passenger access to prevent overcrowding in certain areas), dock-skipping (strategically skipping docks or platforms to improve service flow), short-turning (rerouting certain services earlier to optimize capacity), and real-time stop position selection (dynamically selecting stops based on demand) [

54]. The last two involve coordination with the operators of the different transport modes.

Lastly, regarding short and long-term occupancy predictions, the literature has shown that the availability of congestion information can influence users’ travel decisions, allowing them to better plan their daily commutes. This not only benefits passengers but can also be strategically used to optimize system operations and distribute the demand more efficiently [

54,

55]. Making the predicted information available not only to operators but also, to some extent, to users, actively encouraging them to explore more convenient travel alternatives. This could help reduce excessive passenger concentration at specific points in the system and enhance the overall mobility experience.

Finally, by integrating real-time and predictive data, this tool proves effective in transforming raw information into actionable insights. It enables a more efficient, adaptable, and user-friendly transport interchange by proactively managing fluctuations in occupancy and passenger flow. This approach helps maintain an optimal level of service, ensuring smoother operations and improved passenger experience.

6. Conclusions

The primary function of multimodal transport stations is to facilitate passenger transfers, reduce the penalties associated with them, and act as connection nodes within the system, thereby contributing to an improved perception of the service. Therefore, their role as places is also relevant, especially in their integration within the urban context. This dual function is evident at the Moncloa interchange, where around half of the passengers passing through the bus station visit the commercial area, highlighting the importance of those areas for improving the interchange´s perceived quality.

The proposed methodology develops a real-time and predictive tool that integrates data from both functional interchange dimensions and uses these data to monitor current situations and forecast the short-term ones. This information enables the application of data-driven strategies to proactive decision-making and efficient planning of the space, ensuring optimized operational management while maintaining the Level of Service at a good rate.

Specifically, regarding the technical characteristics of the prediction model used, it is relatively insensitive to fine-tuning, which simplifies its application and scalability for use in other case studies with larger and more diverse data sources. Furthermore, this is supported by the fact that its training and prediction times are negligible, allowing for frequent retraining with high flexibility and maintaining low hardware requirements.

Future research should focus on enhancing the capabilities and adaptability of the predictive model. The first improvement could be to expand the prediction to a longer term by incorporating a longer time span of data to reflect long-term seasonal trends; secondly, adding to the model the Automatic Fare Collection (AFC) data at entry points, will provide a more comprehensive view of passenger demand and its relationship with the occupancy dynamics. Furthermore, incorporating external variables, such as special events, service disruptions, and fluctuations in commercial activity, will enhance the model’s ability to anticipate variations in passenger flow and occupancy levels. Lastly, testing the model in various types of multimodal interchanges with different layouts, service configurations, and demand patterns would help generalize the results and facilitate their transfer to other transport nodes.

Finally, the application of this tool to optimize dynamic management of transport interchanges in large metropolitan areas, where nearly 80% of citizens rely on public transportation [

12], would help to improve service levels. This will provide guidelines for more comfortable space utilization and efficient transfer flows, making public transport more competitive compared to private transportation.

Funding

Project PLEC2021-007609 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR.

Abbreviations

| APC |

Automatic Passenger Counting |

| AFC |

Automatic Fare Validation |

| ITS |

Intelligent Transport System |

| LOS |

Level Of Service |

| LSTM |

Long-Short Term Memory |

| MAE |

Median Absolute Error |

References

- Yun, T.-G.; Lee, Y.-I. A Study on the Evaluation Method of Level of Service in Transfer Walking Facilities. Journal of Korean Society of Transportation 2010, 28, 143–156.

- Zhang, J.; Ai, Q.; Ye, Y.; Deng, S. Dynamic Flow Analysis and Crowd Management for Transfer Stations: A Case Study of Suzhou Metro. Public Transport 2024, 16, 619–653. [CrossRef]

- Kabalan, B.; Leurent, F.; Christoforou, Z.; Dubroca-Voisin, M. Framework for Centralized and Dynamic Pedestrian Management in Railway Stations. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier B.V., 2017; Vol. 27, pp. 712–719.

- Molyneaux, N.; Scarinci, R.; Bierlaire, M. Pedestrian Management Strategies for Improving Flow Dynamics in Transportation Hubs; Lausanne, 2017;

- Ahn, Y.; Kowada, T.; Tsukaguchi, H.; Vandebona, U. Estimation of Passenger Flow for Planning and Management of Railway Stations. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier B.V., 2017; Vol. 25, pp. 315–330.

- McCarthy, C.; Moser, I.; Jayaraman, P.P.; Ghaderi, H.; Tan, A.M.; Yavari, A.; Mehmood, U.; Simmons, M.; Weizman, Y.; Georgakopoulos, D.; et al. A Field Study of Internet of Things-Based Solutions for Automatic Passenger Counting. IEEE Open Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 2, 384–401. [CrossRef]

- van Den Heuvel, J.; Voskamp, A.; Daamen, W.; Hoogendoorn, S.P. Using Bluetooth to Estimate the Impact of Congestion on Pedestrian Route Choice at Train Stations. In Proceedings of the Traffic and Granular Flow, 2013; Springer International Publishing, 2015; pp. 73–82.

- Hoppe, J.; Schwinger, F.; Haeger, H.; Wernz, J.; Jarke, M. Improving the Prediction of Passenger Numbers in Public Transit Networks by Combining Short-Term Forecasts with Real-Time Occupancy Data. IEEE Open Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 4, 153–174. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, F.; Shen, Q. Cluster-Based LSTM Network for Short-Term Passenger Flow Forecasting in Urban Rail Transit. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 147653–147671. [CrossRef]

- Cascajo, R.; Lopez, E.; Herrero, F.; Monzon, A. User Perception of Transfers in Multimodal Urban Trips: A Qualitative Study. Int J Sustain Transp 2019, 13, 393–406. [CrossRef]

- Cascajo, R.; Garcia-Martinez, A.; Monzon, A. Stated Preference Survey for Estimating Passenger Transfer Penalties: Design and Application to Madrid. European Transport Research Review 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jara-Diaz, S.; Monzon, A.; Cascajo, R.; Garcia-Martinez, A. An International Time Equivalency of the Pure Transfer Penalty in Urban Transit Trips: Closing the Gap. Transp Policy (Oxf) 2022, 125, 48–55. [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, R.; O’higgins, T. Public Transport Interchange Design Guidelines: Final Report; Auckland, 2013;

- Transport for London Interchange Best Practice Guidelines; London, 2021;

- Monzón, A.; Di Ciommo, F. CITY-HUBs: Sustainable and Efficient Urban Transport Interchanges; 2016;

- Bertolini, L.; Spit, T. Cities on Rails; Routledge, 2005; ISBN 9781135811259.

- Bernal, L.M.M.D. Basic Parameters for the Design of Intermodal Public Transport Infrastructures. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier B.V., 2016; Vol. 14, pp. 499–508.

- Lois, D.; Monzón, A.; Hernández, S. Analysis of Satisfaction Factors at Urban Transport Interchanges: Measuring Travellers’ Attitudes to Information, Security and Waiting. Transp Policy (Oxf) 2018, 67, 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Heekyukim; Shin, M.; Hur, J.; Sam Moon, Y. A Study on the Analysis of Space and Structural Interface for Improvement of the Transfer Path in a Metro Station. International Journal of Civil, Structural, Environmental and Infrastructure Engineering, Research and Development 2016, 6, 11–16.

- Moodley, S.; Venter, C. Measuring the Service Quality at Multimodal Public Transport Interchanges: A Needs-Driven Approach. In Transportation Research Record; SAGE Publications Ltd, 2022; Vol. 2676, pp. 194–206.

- Terzis, G.; Last, A. GUIDE Project - Urban Interchanges - A Good Practice: Final Report; 2000;

- Consorcio Proyecto PIRATE Intercambiador de Transporte: Manual y Directrices; Madrid, 2000;

- Wilson, T.; Yariv, B. Station Design Principles for Network Rail; 2015;

- Hernández del Olmo, S. Assessment Methodology to Make Urban Transport Interchanges Attractive for Users, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, 2015.

- Chauhan, V.; Gupta, A.; Parida, M. Demystifying Service Quality of Multimodal Transportation Hub (MMTH) through Measuring Users’ Satisfaction of Public Transport. Transp Policy (Oxf) 2021, 102, 47–60. [CrossRef]

- Hine, J.; Scott, J. Seamless, Accessible Travel: Users’ Views of the Public Transport Journey and Interchange; 2000;

- Hernandez, S.; Monzon, A. Key Factors for Defining an Efficient Urban Transport Interchange: Users’ Perceptions. Cities 2016, 50, 158–167. [CrossRef]

- DellߣAsin, G.; Monzón, A.; Lopez-Lambas, M.E. Key Quality Factors at Urban Interchanges. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Transport 2015, 168, 326–335. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.; Monzon, A.; de Oña, R. Urban Transport Interchanges: A Methodology for Evaluating Perceived Quality. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 2016, 84, 31–43. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Schmöcker, J.D.; Yu, J.W.; Choi, J.Y. Service Quality Evaluation for Urban Rail Transfer Facilities with Rasch Analysis. Travel Behav Soc 2018, 13, 26–35. [CrossRef]

- Desiderio, N. Requirements of Users and Operators on the Design and Operation of Intermodal Interchanges; 2004;

- Li, L.; Loo, B.P.Y. Towards People-Centered Integrated Transport: A Case Study of Shanghai Hongqiao Comprehensive Transport Hub. Cities 2016, 58, 50–58. [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Berki, B.; Dohmen, C.; Wauters, C.; Moszkowicz, D.; Koenig, G.; Carmena, G.; Koberg, H.; Moreno Sanz, I.B.; Singh, J.; et al. Improving Passenger Flow and Crowd Management through Technology and Innovation; Brussels, 2022;

- Pasini, K.; Khouadjia, M.; Samé, A.; Ganansia, F.; Oukhellou, L. LSTM Encoder-Predictor for Short-Term Train Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer, 2020; Vol. 11908 LNAI, pp. 535–551.

- Vieira, T.; Almeida, P.; Meireles, M.; Ribeiro, R. Public Transport Occupancy Estimation Using WLAN Probing and Mathematical Modeling. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier B.V., January 1 2020; Vol. 48, pp. 3299–3309.

- Kuchár, P.; Pirník, R.; Janota, A.; Malobický, B.; Kubík, J.; Šišmišová, D. Passenger Occupancy Estimation in Vehicles: A Review of Current Methods and Research Challenges. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, N.; Morton, A.; Akartunalı, K. Passenger Demand Forecasting in Scheduled Transportation. Eur J Oper Res 2020, 286, 797–810. [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.; Yu, Z.; Gayah, V. V. Development and Evaluation of Frameworks for Real-Time Bus Passenger Occupancy Prediction. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology 2023, 12, 399–413. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, X. Short-Term Passenger Flow Prediction with Decomposition in Urban Railway Systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 107876–107886. [CrossRef]

- Dib, A.; Cherrier, N.; Graive, M.; Rérolle, B.; Schmitt, E. Unified Occupancy on a Public Transport Network through Combination of AFC and APC Data. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Consorcio de Transportes de Madrid (CRTM) Intercambiador de Moncloa Available online: https://www.crtm.es/tu-transporte-publico/intercambiadores/grandes-intercambiadores/90_14.aspx (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Comunidad de Madrid Datos Abiertos Available online: https://www.comunidad.madrid/gobierno/datos-abiertos (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Empresa Municipal de Transportes de Madrid (EMT Madrid) Cuentas Anuales e Informes Estadísticos de Gestión Available online: https://www.emtmadrid.es/Empresa/PortalTransparencia (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica Conservation of Energy Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/conservation-of-energy (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Liu, G.; Yin, Z.; Jia, Y.; Xie, Y. Passenger Flow Estimation Based on Convolutional Neural Network in Public Transportation System. Knowl Based Syst 2017, 123, 102–115. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection; 2016;

- Xue, R.; Sun, D. (Jian); Chen, S. Short-Term Bus Passenger Demand Prediction Based on Time Series Model and Interactive Multiple Model Approach. Discrete Dyn Nat Soc 2015, 2015, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM). Neural Comput 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [CrossRef]

- Toque, F.; Come, E.; El Mahrsi, M.K.; Oukhellou, L. Forecasting Dynamic Public Transport Origin-Destination Matrices with Long-Short Term Memory Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 19th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC); IEEE, November 2016; pp. 1071–1076.

- Toque, F.; Khouadjia, M.; Come, E.; Trepanier, M.; Oukhellou, L. Short & Long-Term Forecasting of Multimodal Transport Passenger Flows with Machine Learning Methods. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC); IEEE, October 2017; pp. 560–566.

- Bergmann, D.; Stryker, C. What Is a Loss Function? Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/loss-function (accessed on 16 March 2025).

-

Highway Capacity Manual 7th Edition; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2022; ISBN 978-0-309-27566-8.

- Tang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Cabrera, J.; Ma, J.; Tsui, K.L. Forecasting Short-Term Passenger Flow: An Empirical Study on Shenzhen Metro. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2019, 20, 3613–3622. [CrossRef]

- Jenelius, E. Data-Driven Metro Train Crowding Prediction Based on Real-Time Load Data. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2020, 21, 2254–2265. [CrossRef]

- Pasini, K.; Khouadjia, M.; Samé, A.; Ganansia, F.; Oukhellou, L. LSTM Encoder-Predictor for Short-Term Train Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer, 2020; Vol. 11908 LNAI, pp. 535–551.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).