I. Introduction

The increasing prevalence of information technology and the accelerated growth of the e-commerce sector have underscored the paramount importance of developing and optimising logistics networks. Nevertheless, the scarcity of urban logistics resources makes it challenging to satisfy the rising demand for logistics services, particularly in light of the increasing diversity and personalisation of customer requirements [

1]. In order to enhance the operational efficacy of the logistics network, it has become a pivotal objective to develop a rational transportation plan for logistics vehicles, optimise resource allocation and maximise resource utilisation.

In practical applications, customer needs are highly personalised and diversified, thereby placing higher demands on the timeliness and efficiency of logistics services. This necessitates not only the implementation of an efficient route planning strategy, but also the capacity of the logistics system to adaptively respond to the inherent variability of demand. The integration of intelligent technology and big data analysis enables logistics companies to more accurately predict customer needs and rationally allocate logistics resources, thereby facilitating efficient distribution, improving service quality and reducing operating costs [

2]. This, in turn, provides support for the sustainable development of urban logistics.

An efficient logistics network is typically comprised of several key components, including warehousing centres, distribution centres, transportation routes, information systems, and distribution terminals. The warehousing centre is responsible for the storage and management of goods, ensuring a reasonable level of inventory is maintained. The distribution centre serves as a transit point, coordinating logistics activities across a variety of locations [

3]. Transport routes encompass a range of modes of transport, including road, rail, air and water, facilitating the swift and secure delivery of goods to their destination. Information systems occupy a pivotal position within the logistics network, enabling comprehensive control and optimisation of logistics activities through real-time monitoring and data analysis.

In order to construct an effective logistics network, it is essential for companies to implement a range of optimisation strategies. The initial step is the optimisation of the network layout, which can be achieved through the scientific selection of warehousing and distribution centres. This approach has the potential to reduce transportation distance, minimise transportation time and reduce costs. The second strategy is the optimisation of transportation routes [

4]. This is achieved through the utilisation of sophisticated algorithms and software tools, which facilitate the planning of optimal transportation routes, thereby avoiding traffic congestion and the wastage of resources. Furthermore, the optimisation of inventory management is pivotal to the reduction of inventory overstock and stock-out risk through the implementation of accurate demand forecasting and inventory control strategies.

The effective operation of a contemporary logistics network is contingent upon the utilisation of sophisticated technology. The Internet of Things (IoT) technology facilitates the real-time monitoring of goods and means of transport, thereby ensuring transparency and traceability of logistics processes. The application of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms enables the analysis of vast quantities of data, the optimisation of transportation routes and resource allocation, and the enhancement of decision-making processes through the application of scientific and accurate methodologies. Blockchain technology provides a secure and reliable data-sharing platform for logistics networks, thereby enhancing transparency and trust within the supply chain [

5]. Furthermore, the implementation of automated equipment and robotics has enhanced the efficacy of warehousing and distribution operations while reducing labour costs.

While there are numerous advantages to optimising the logistics network, there are also a number of challenges that must be overcome in practice. The first of these is the finite nature of resources, which is particularly pertinent in high-density cities, where competition for logistics resources is becoming increasingly intense [

6]. The second is the complexity of technology, and the challenge of effectively integrating and applying various emerging technologies is an urgent issue that must be addressed. Furthermore, changes in policies and regulations, as well as the requirements of environmental protection, have also introduced new requirements for the construction of logistics networks [

7].

III. Methodologies

A. YOLOv8 Framework

In order to capture the temporal dependence of demand and traffic state in the logistics and transportation network, a multi-layer bidirectional LSTM network is employed for the purpose of modelling the input sequence. We consider an input sequence X = {x1, x2, ..., x}, where x_t represents the input feature of time step t. The hidden state update formula for layer l bidirectional LSTM is as Equations (1)–(4):

The forward and backward LSTMs process the forward and backward information of the sequence, respectively, and merge the hidden states of the two through vector splicing to form a comprehensive hidden representation , which is used as the input of the next layer. The bidirectional structure enables the capture of information from the time series in its entirety, thereby enhancing the accuracy of forecasting.

In order to enhance the adaptability of the logistics and transportation network to optimisation requirements, a weighted loss function has been devised. This function combines the prediction error and the optimisation objective, as illustrated in Equation (5):

The acronym stands for mean square error, which is employed to quantify the discrepancy between the predicted and actual values. The term represents the regularisation term, which is utilised to avert the phenomenon of overfitting in the model. The weight coefficients and are employed to achieve a balance between these two aspects of the loss function, thereby ensuring that the model exhibits good generalisation ability while simultaneously enhancing the accuracy of the predictions.

B. Self-Supervised Learning

The attention weights are calculated using the scaled dot product attention, which is expressed in Equation (6).

The weighted attention output is obtained by multiplying the attention weight matrix by the value matrix . This step integrates the information from the parts of the input sequence and weights them according to their importance.

The introduction of a multi-head mechanism enables the capture of features from disparate subspaces through the utilisation of parallel multiple attention heads, as illustrated in Equation (7):

The attention output of the various subspaces is calculated in parallel by multiple attention heads, and then these output vectors are spliced together. The resulting spliced output is then transformed linearly to generate the final multi-head attention output. This approach serves to enhance the model’s capacity to capture a diverse range of features.

It is recommended that the weight of each attention head be adaptively adjusted according to the prevailing environmental conditions, as illustrated by Equations (8) and (9):

A modest neural network generates a dynamic weight based on the prevailing state of the environment and activates the function to guarantee that the weights remain within a reasonable range. Subsequently, the output of each attention head is weighted and summed according to the dynamic weight , thereby obtaining the final attention output . This mechanism enables the model to adaptively enhance or reduce the impact of different attention heads in response to real-time environmental changes.

The

-value function is approximated using DQN and updated by empirical replay and target network, as expressed in Equations (10) and (11):

Deep -Network approximates the optimal -function, , by parameter . The loss function, , optimises the parameters by minimising the mean square error between the current -value and the target -value. The experience replay pool, designated as , serves to store historical experience samples, which are then randomly sampled for training purposes. This approach effectively breaks the temporal correlation of the data, thereby enhancing the stability of the training process. Concurrently, the target network parameter is introduced and periodically updated as a copy of the current network parameter, thereby stabilising the training process.

IV. Experiments

A. Experimental Setups

The Freight Analysis Framework (FAF) dataset, provided by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS), was employed in the experiment. The dataset encompasses the movement of goods within the United States by disparate modes of transportation, including road, rail, air, and water. It comprises comprehensive records of timestamps, cargo types, origin and destination, transportation distances, transportation times, and transportation costs.

Further, a three-layer stacked bidirectional LSTM structure, comprising 128 hidden cells in each layer, is employed to effectively capture both short- and long-term time series dependencies in transportation network data. The self-attention mechanism is constructed with four parallel attention heads, each with a dimension set to 64, with the objective of emphasising pivotal time points and localising features. During the training phase, the Adam optimiser was employed, the learning rate was set to 0.001, and the batch size was 64.

B. Experimental Analysis

In order to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed model’s effectiveness, three comparative methods were selected: Genetic Algorithm (GA), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) and Integer Programming (IP). A genetic algorithm is a global optimisation algorithm that simulates natural selection and genetic mechanisms. It is therefore well-suited to solving complex combinatorial optimisation problems and possesses strong global search capabilities. The ant colony algorithm draws on the foraging behaviour of ants and optimises the path through the accumulation and volatilisation mechanism of pheromones, which makes it particularly well-suited to the fields of transportation network and path planning. Integer programming is a classical mathematical optimisation method. It is suitable for optimisation problems with explicit constraints, whereby linear objective functions and constraints are established to solve the optimal solution of discrete variables.

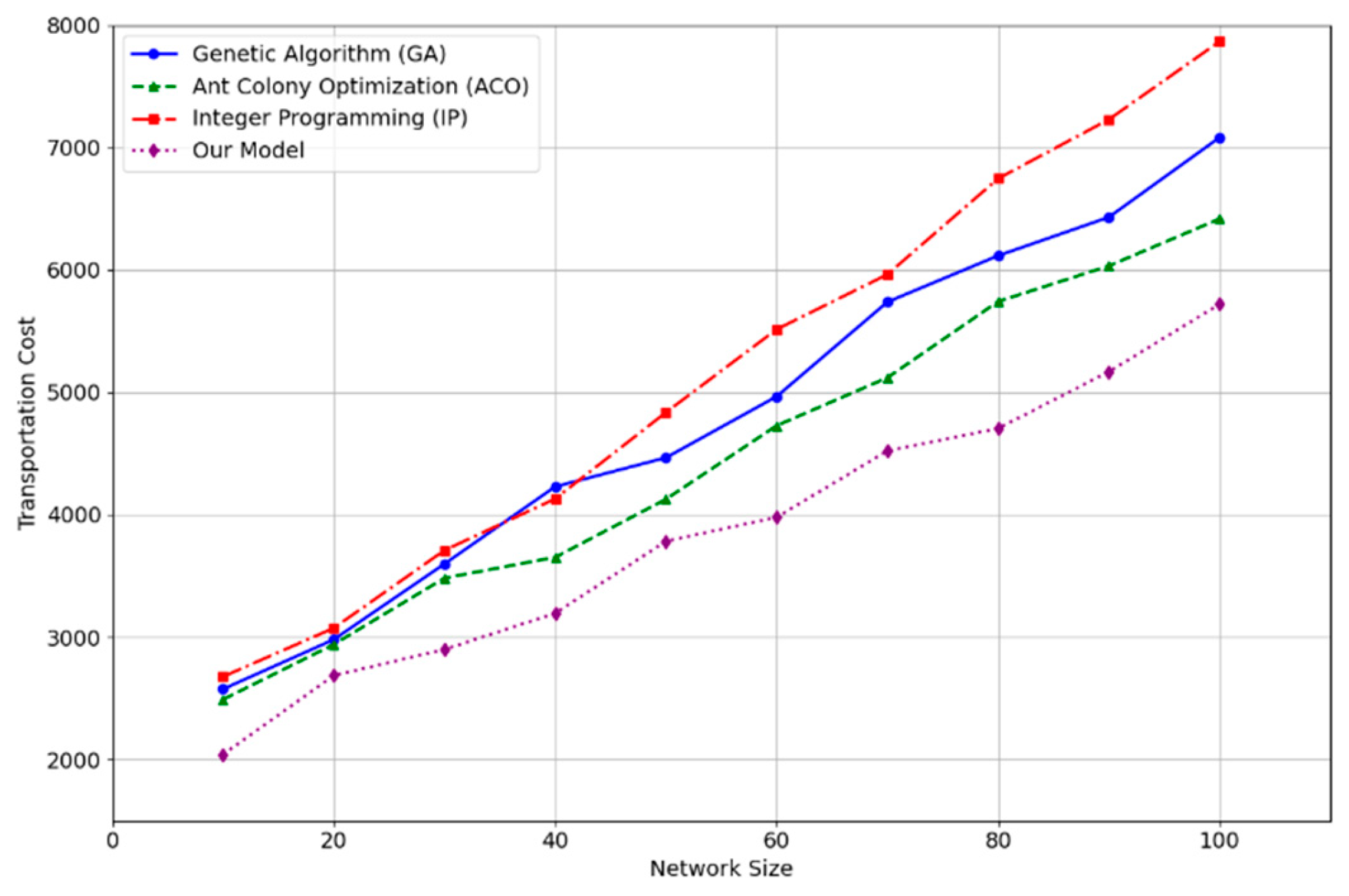

The transportation cost is employed as an evaluation index to assess the optimisation effect, with the primary objective being to ascertain the minimum transportation cost required by the model across varying network scales. A reduction in shipping costs will result in enhanced optimisation efficiency and an improved network performance. In the experiment, the Our model demonstrated superior performance compared to other methods, particularly in the context of large-scale networks. Its transportation cost was notably low, indicating that it possesses robust adaptability and optimisation capabilities in complex and dynamic logistics environments.

Figure 1 depicts the fluctuations in transportation costs across varying network scales for distinct optimization techniques. As the network scale increases, the transportation cost of the Our model is significantly lower than that of the GA, ACO and IP methods, thereby verifying the advantages of the Our model when combined with a self-attention mechanism and reinforcement learning. This demonstrates that the Our model is more effective in predicting and adjusting the network state when dealing with large-scale logistics and transportation networks, thereby reducing costs.

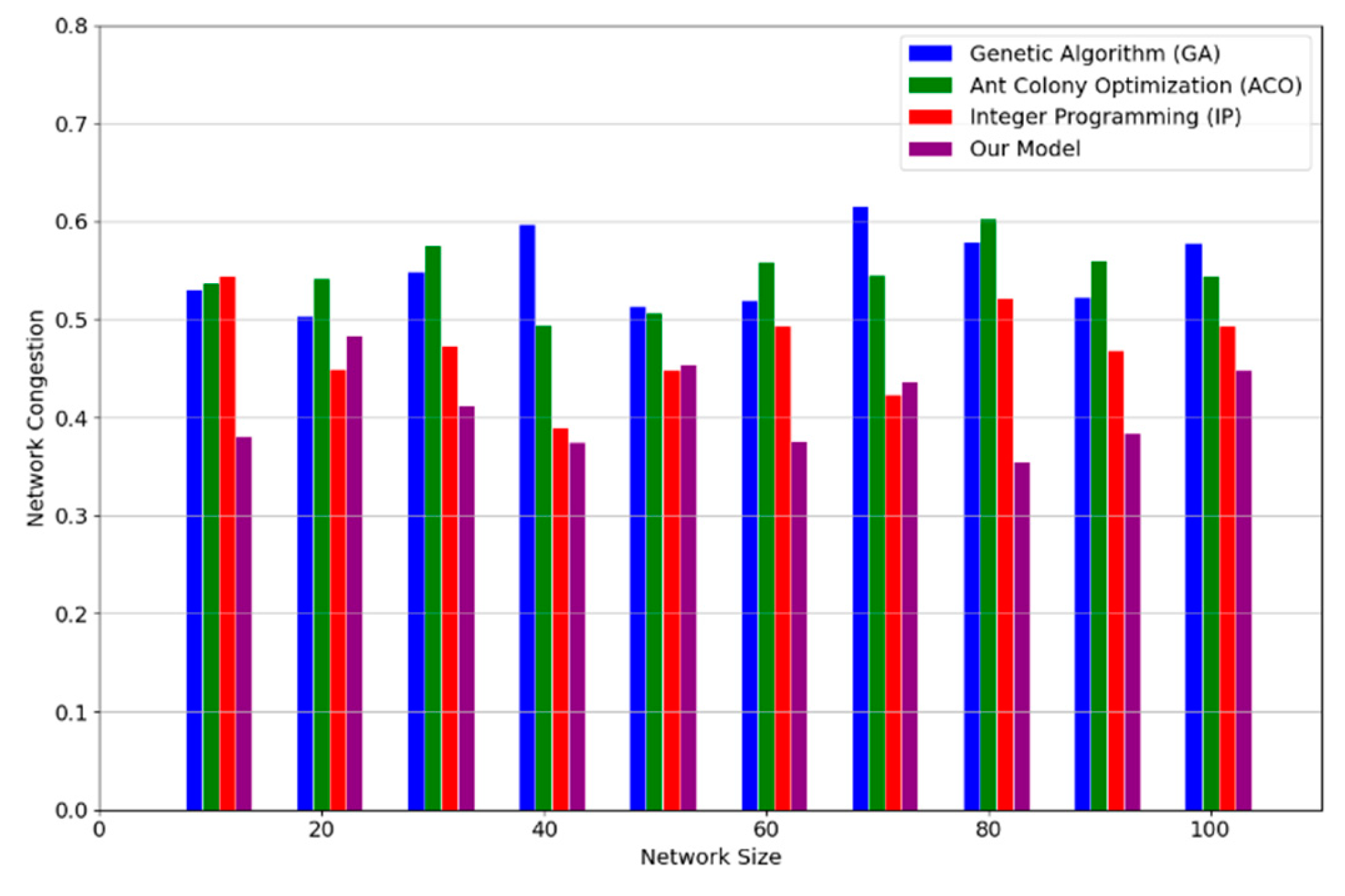

Network congestion is a key performance indicator used to assess the operational efficiency of a transportation network. It is defined as the ratio of traffic flow to the maximum capacity at a critical point in the transportation network, expressed as a rate per unit of time. As illustrated in

Figure 2, congestion levels for all methods increase in proportion to the network size. However, the Our model exhibits the smallest increase in congestion, which is consistently lower than that observed for the Genetic Algorithm (GA), Ant Colony Algorithm (ACO), and Integer Programming (IP) methods. This demonstrates that the Our model is capable of more effectively reducing congestion in transportation networks and adapting to complex, large-scale network optimisation scenarios, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency of the logistics system.

Table 1 illustrates the throughput performance of the four optimisation methods at varying network scales. It is evident that the throughput of the proposed model is considerably higher than that of the alternative methods, which suggests that in large-scale logistics networks, the proposed model can more effectively optimise the performance of the transportation network and enhance logistics efficiency.

V. Conclusions

In conclusion, we propose a dynamic optimisation method for logistics and transportation networks based on long short-term memory neural networks. The method improves the performance of the model in reducing network congestion and optimising transportation costs by combining an attention mechanism with reinforcement learning. The experimental results demonstrate that the our model outperforms the Genetic Algorithm , Ant Colony Algorithm and Integer Programming at multiple network scales, exhibiting enhanced adaptability, particularly in complex logistics environments. Further improvements to the model’s adaptability and scalability may be achieved through the application of advanced technologies, such as deep reinforcement learning and transfer learning.

References

- Li, Ang, et al. “Optimization of logistics cargo tracking and transportation efficiency based on data science deep learning models.” (2024).

- Nimmagadda, Venkata Siva Prakash. “Artificial Intelligence for Real-Time Logistics and Transportation Optimization in Retail Supply Chains: Techniques, Models, and Applications.” Journal of Machine Learning for Healthcare Decision Support 1.1 (2021): 88-126.

- Odimarha, Agnes Clare, Sodrudeen Abolore Ayodeji, and Emmanuel Adeyemi Abaku. Machine learning’s influence on supply chain and logistics optimization in the oil and gas sector: a comprehensive analysis. Computer Science & IT Research Journal 2024, 5, 725–740. [Google Scholar]

- Naganawa, Hisatoshi. Logistics Hub and Route Optimization in the Physical Internet Paradigm. Logistics 2024, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yanqi, et al. Research on logistics management layout optimization and real-time application based on nonlinear programming. Nonlinear Engineering 2021, 10, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, Nazneen N., et al. “Fast approximate solutions using reinforcement learning for dynamic capacitated vehicle routing with time windows.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.12088 (2021).

- Das, Madhushree, et al. Solving fuzzy dynamic ship routing and scheduling problem through new genetic algorithm. Decision Making: Applications in Management and Engineering 2022, 5, 329–361. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, Pedro, and Bernardo Almada-Lobo. The impact of food perishability issues in the vehicle routing problem. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2014, 67, 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Chi Kin, et al. An integrated production-inventory model for deteriorating items with consideration of optimal production rate and deterioration during delivery. International Journal of Production Economics 2017, 189, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelzadeh, Mehdi, Vahid Mahdavi Asl, and Mehdi Koosha. A mathematical model and a solving procedure for multi-depot vehicle routing problem with fuzzy time window and heterogeneous vehicle. The international journal of advanced manufacturing technology 2014, 75, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, Jean-Yves, Ying Xu, and Ilham Benyahia. Vehicle routing and scheduling with dynamic travel times. Computers & Operations Research 2006, 33, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).