Submitted:

29 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reactivation and Growth of Bacillus licheniformis UV01

2.2. Chitinase Gene Amplification

2.3. Purification and Quantification of PCR Product

2.4. Cloning of the Chitinase Gene Chibluv01

2.5. Recombinant Protein Expression

2.6. Preparation of Colloidal Chitin

2.7. Quantification of Concentration Protein

2.8. Enzymatic Assay

2.9. Purification by Affinity Chromatography

2.10. Determination of Optimal Temperature and pH for Chitinolytic Activity

2.11. Adaptation of Aethina tumida.

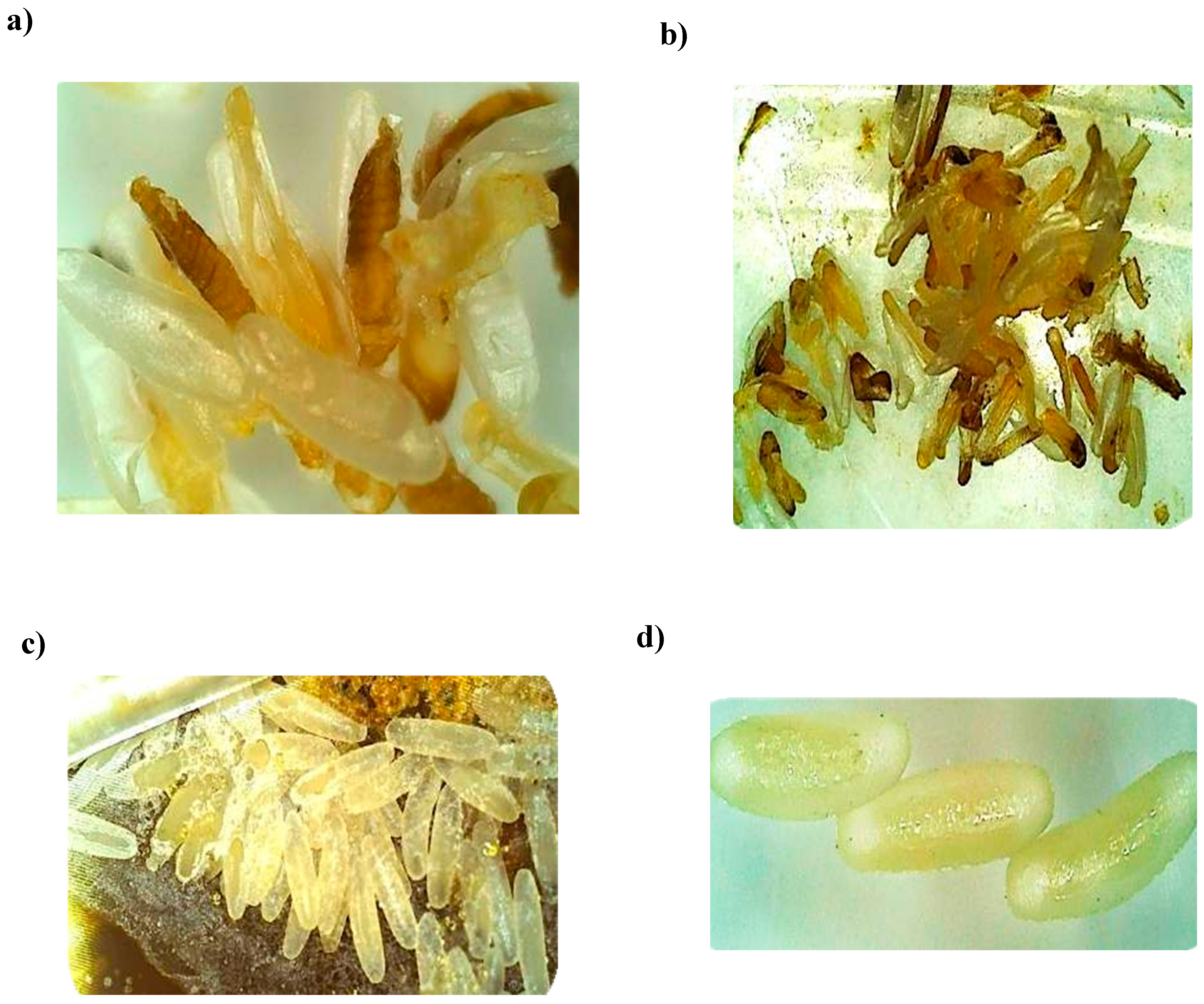

2.12. Choleoptericidal on Activity Aethina tumida

3. Results

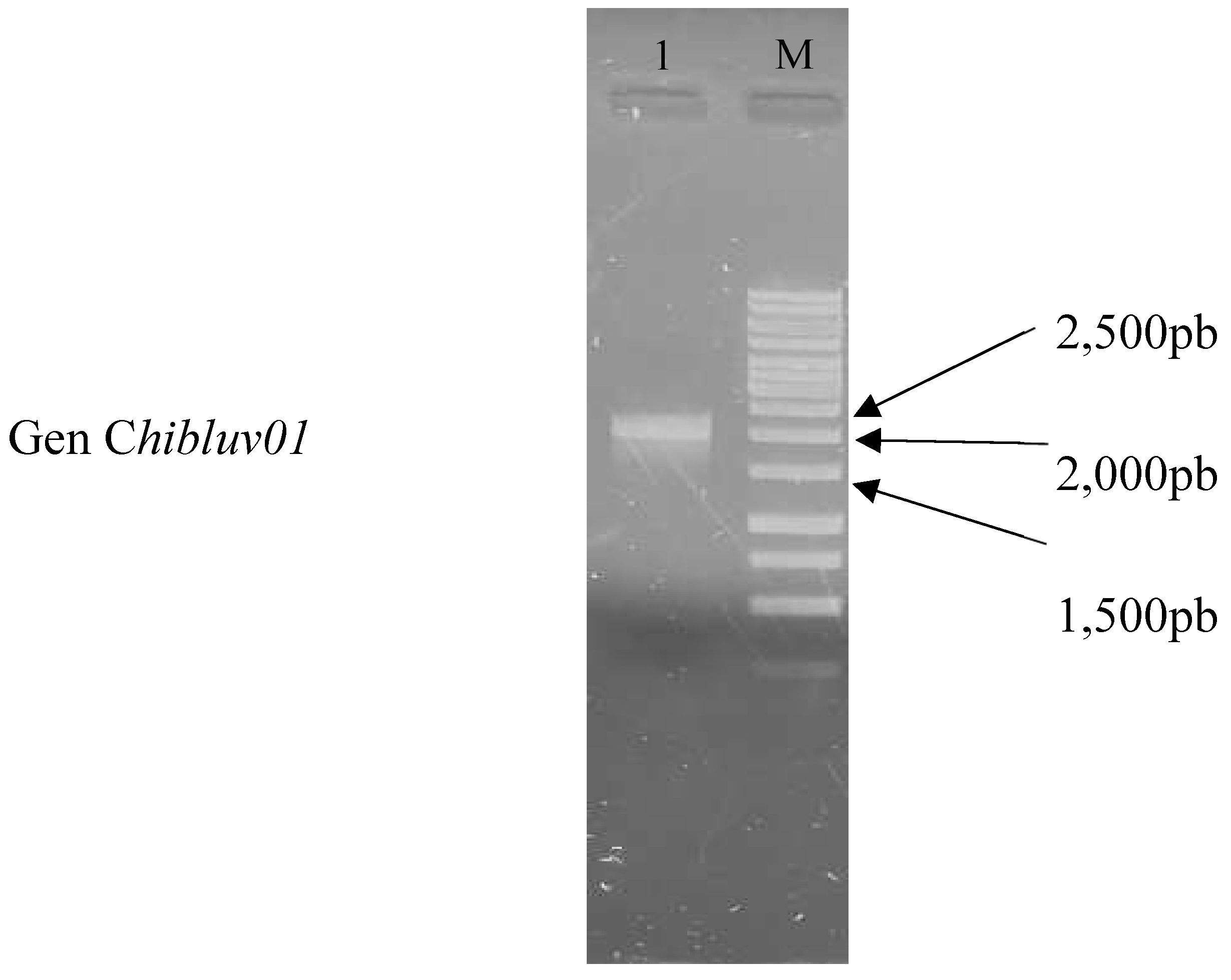

3.1. Recovery of the Gene chiBLUV01

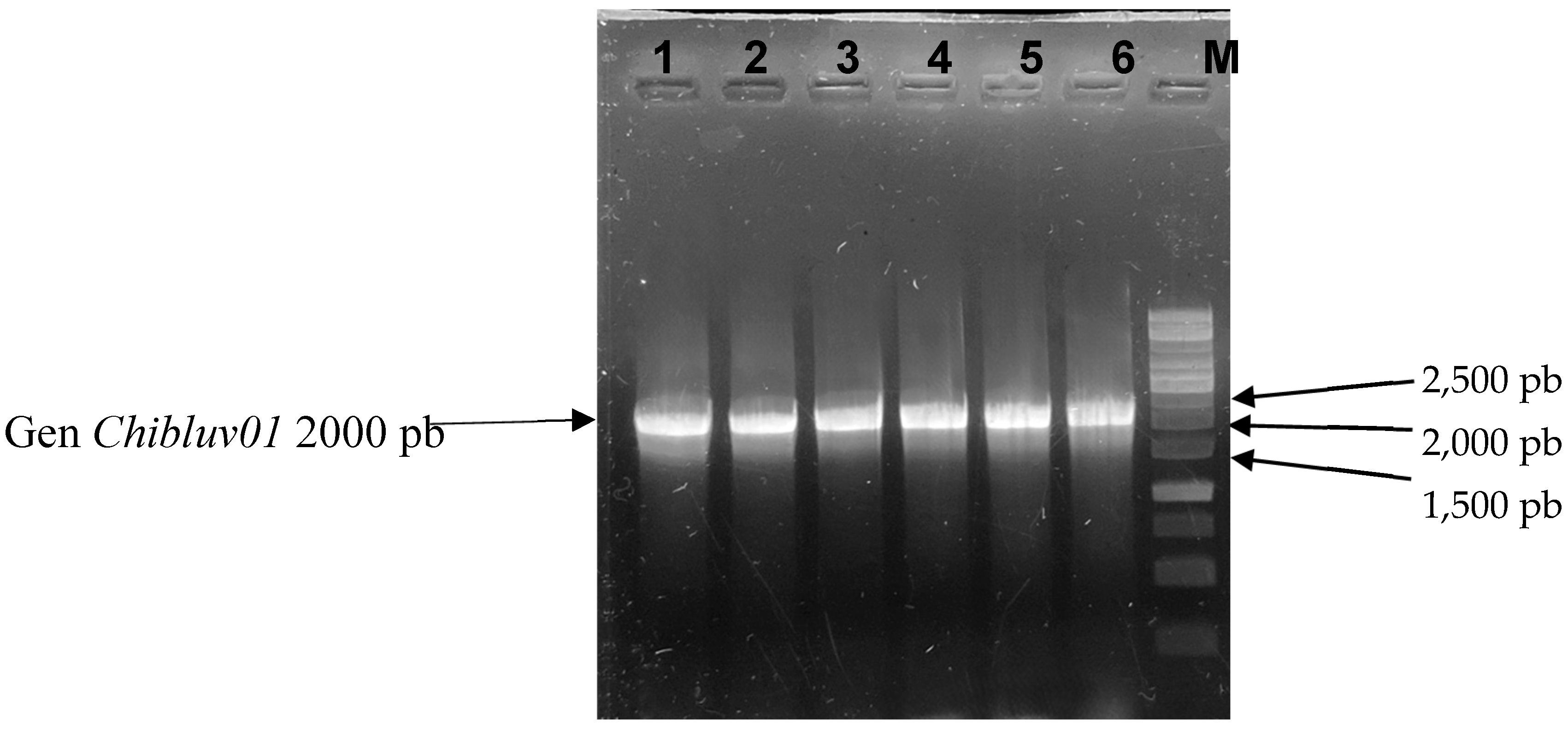

3.2. Identification Transformed Cells

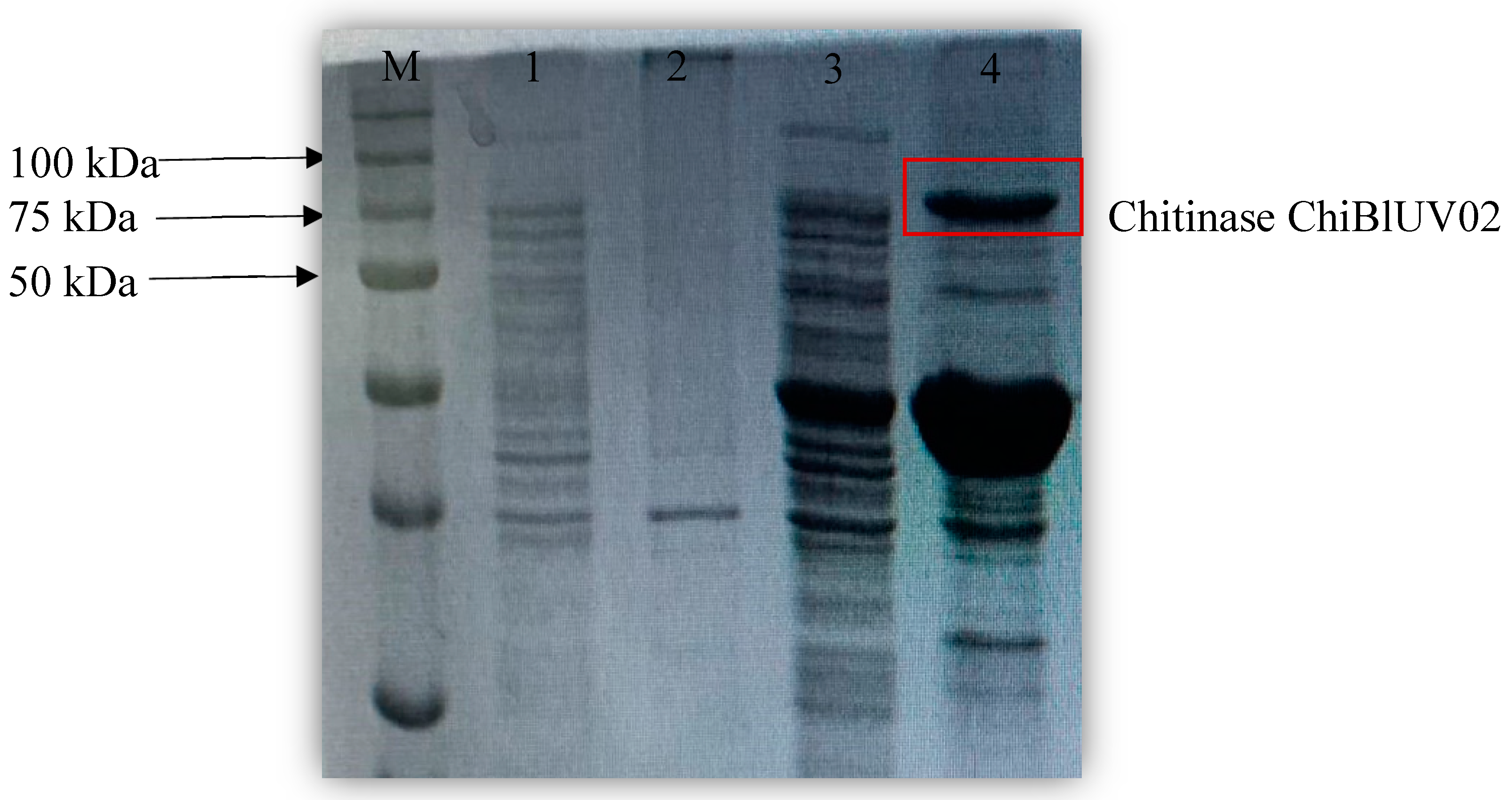

3.3. Induction of chibluv01 Gene Expression

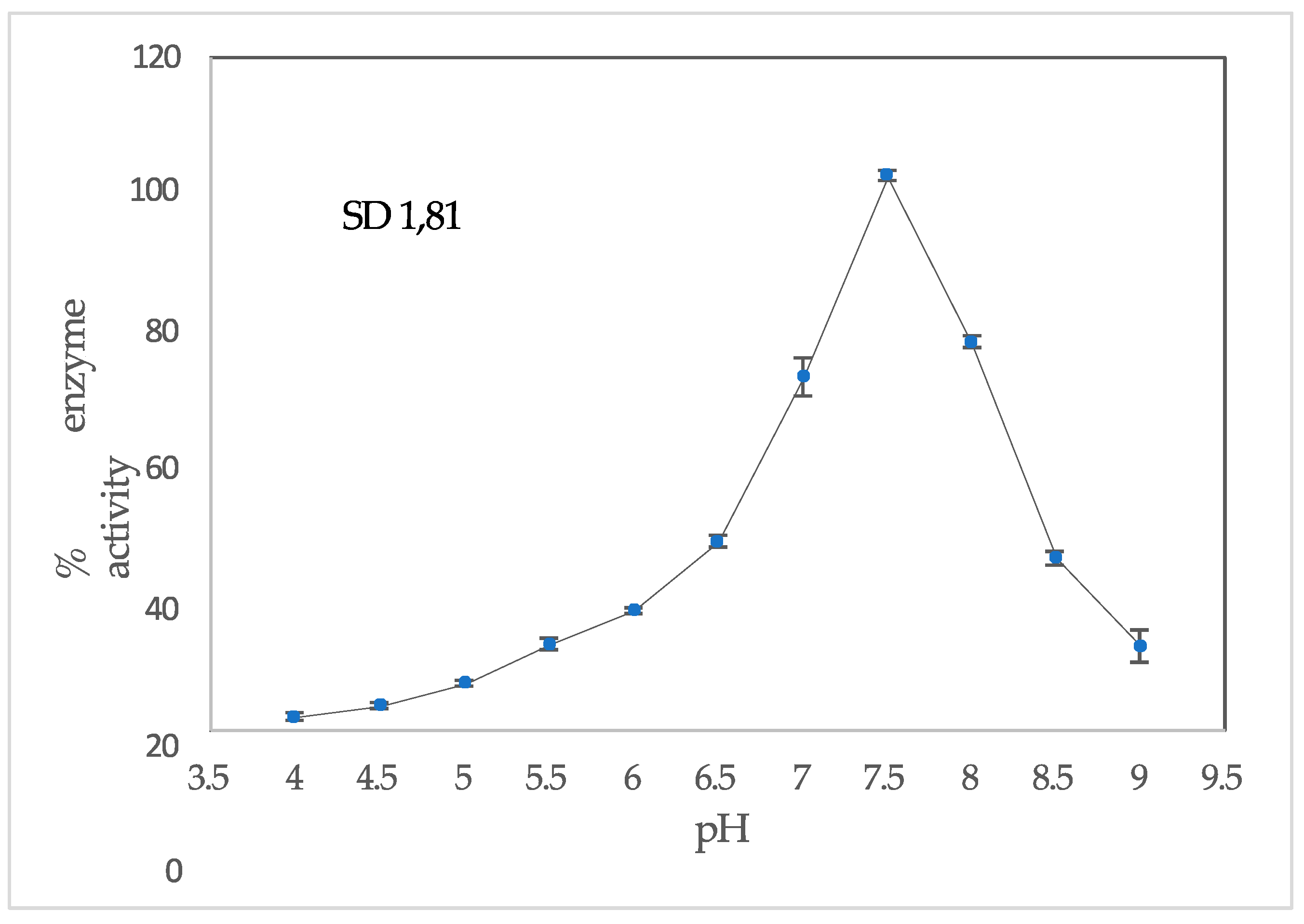

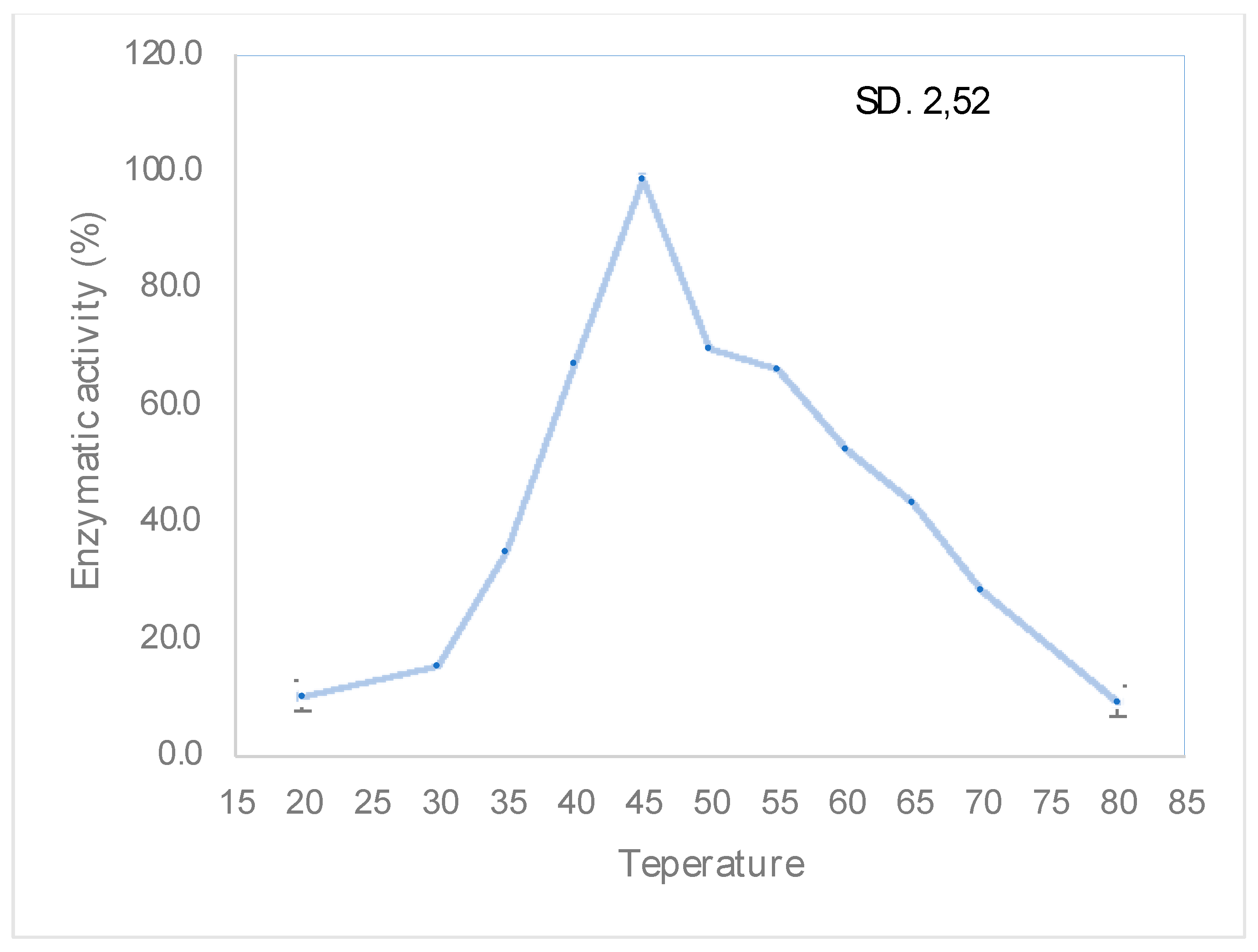

3.4. Determination pH and Temperature Maximum

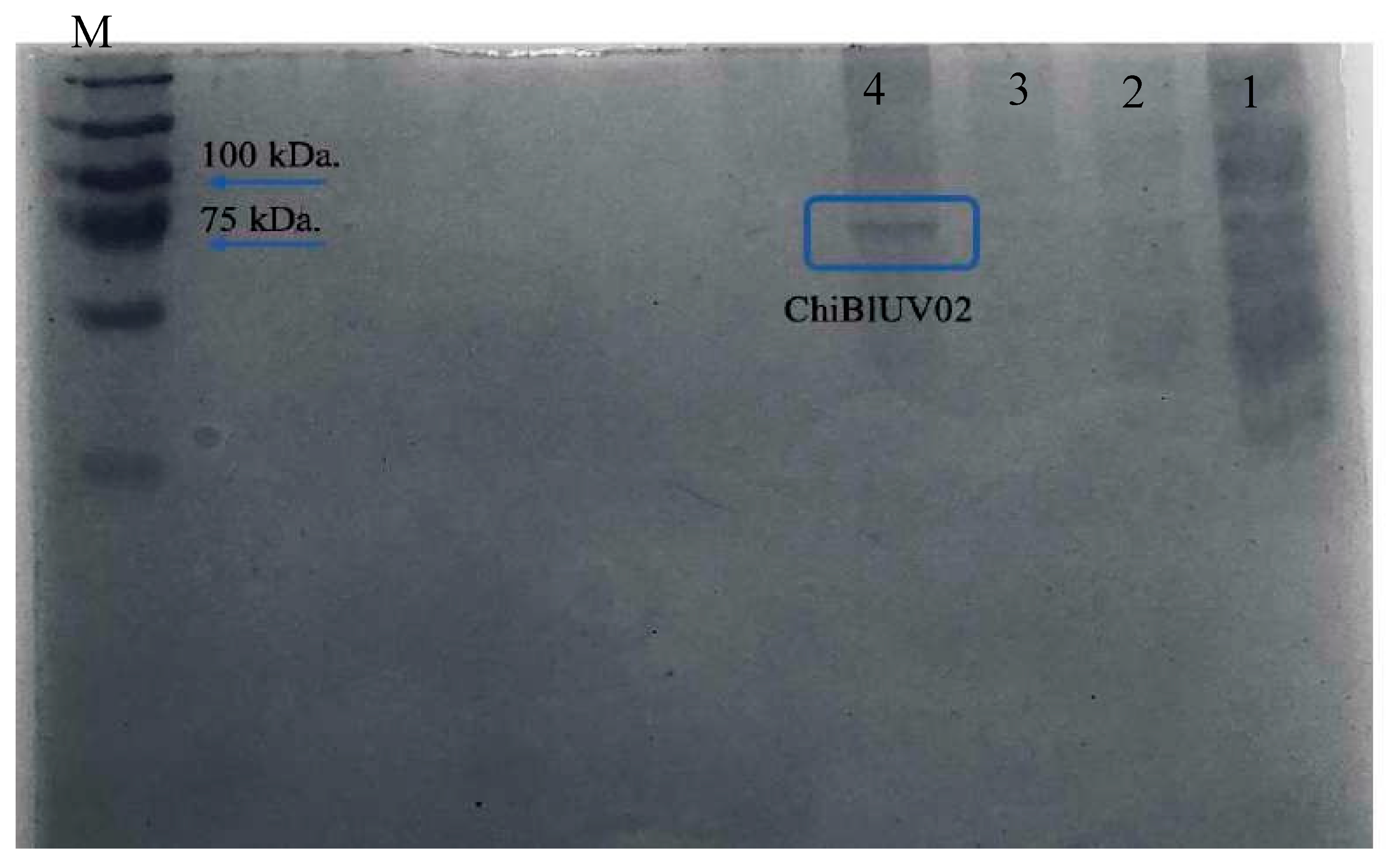

3.5. ChiBlUV02 Chitinase Purification

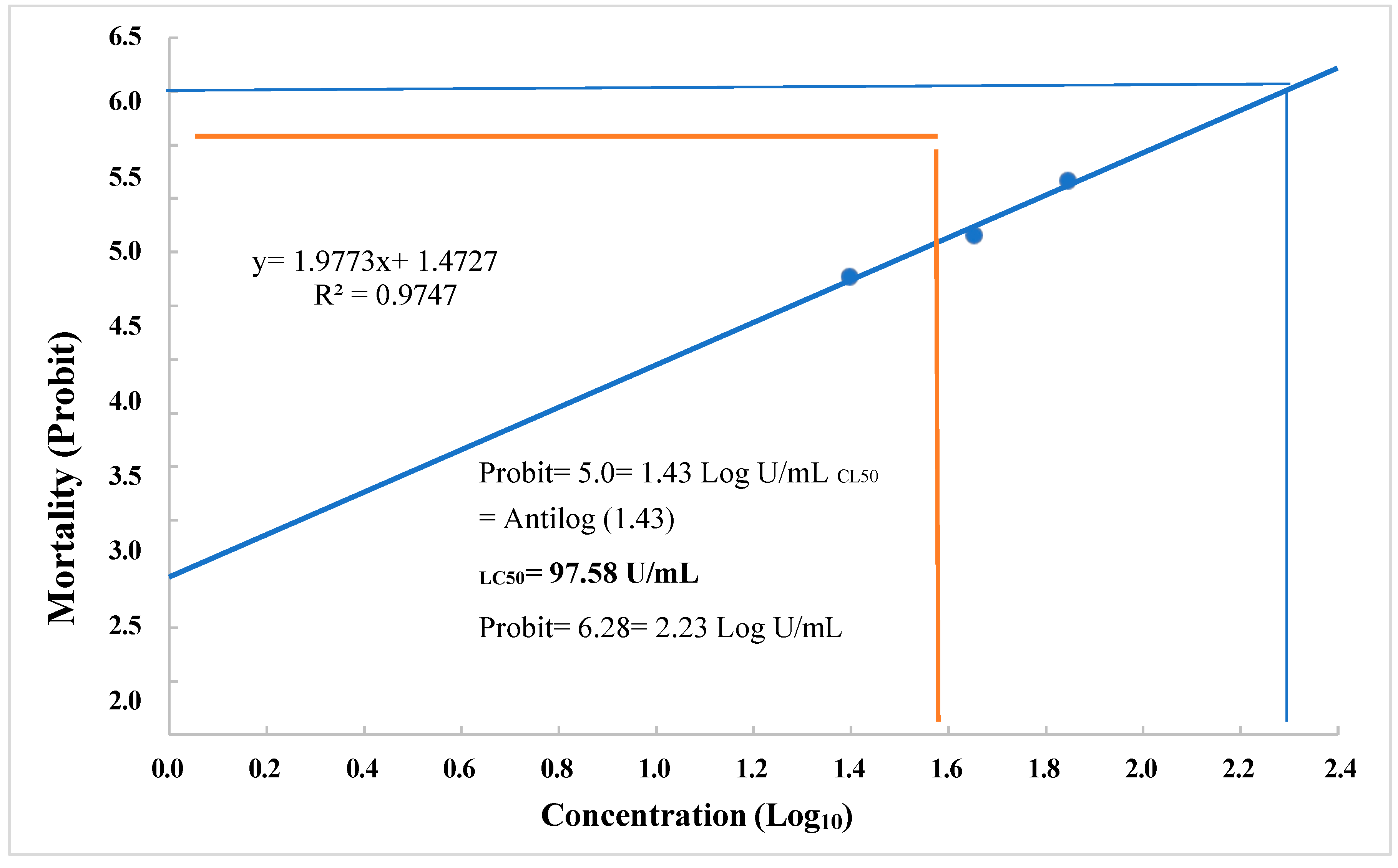

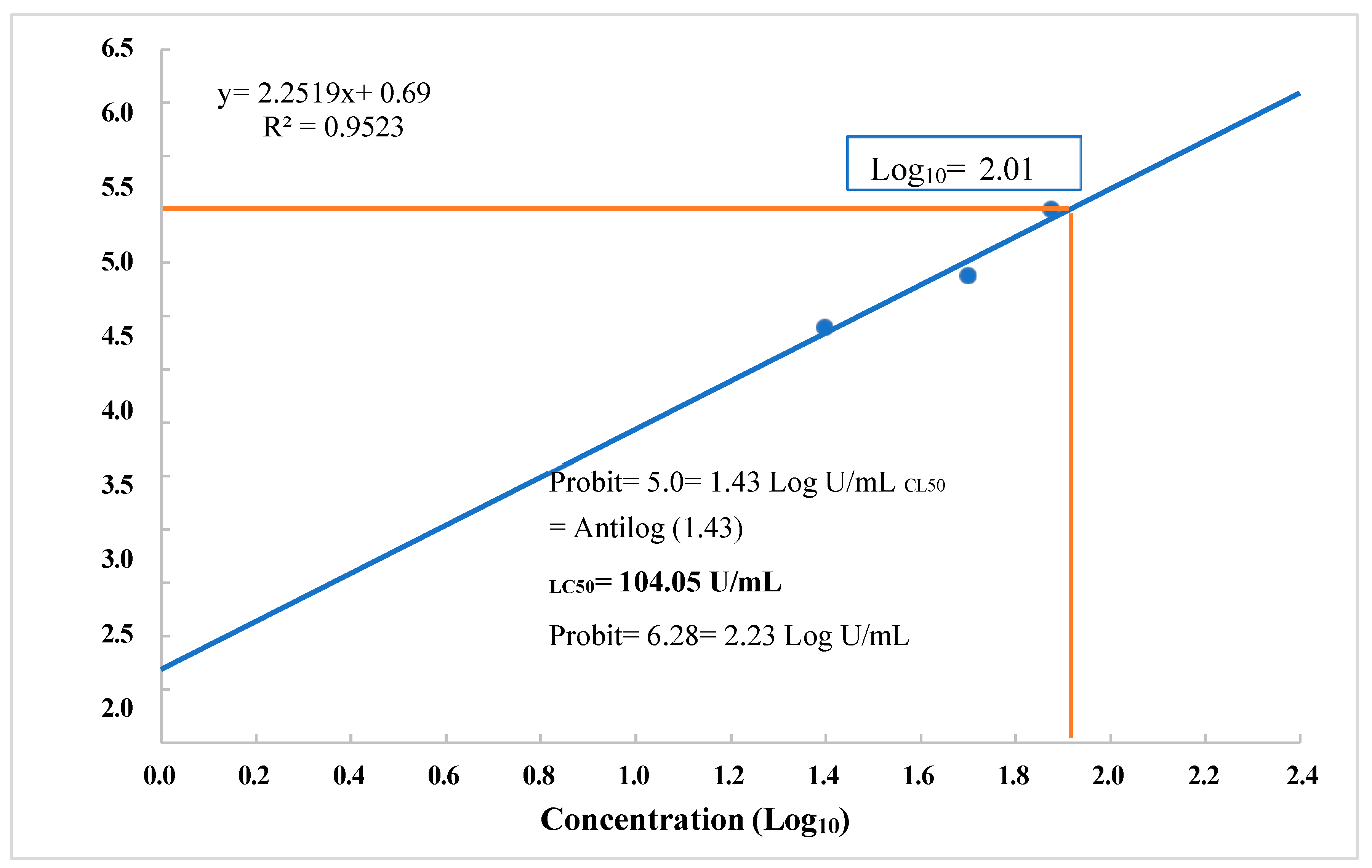

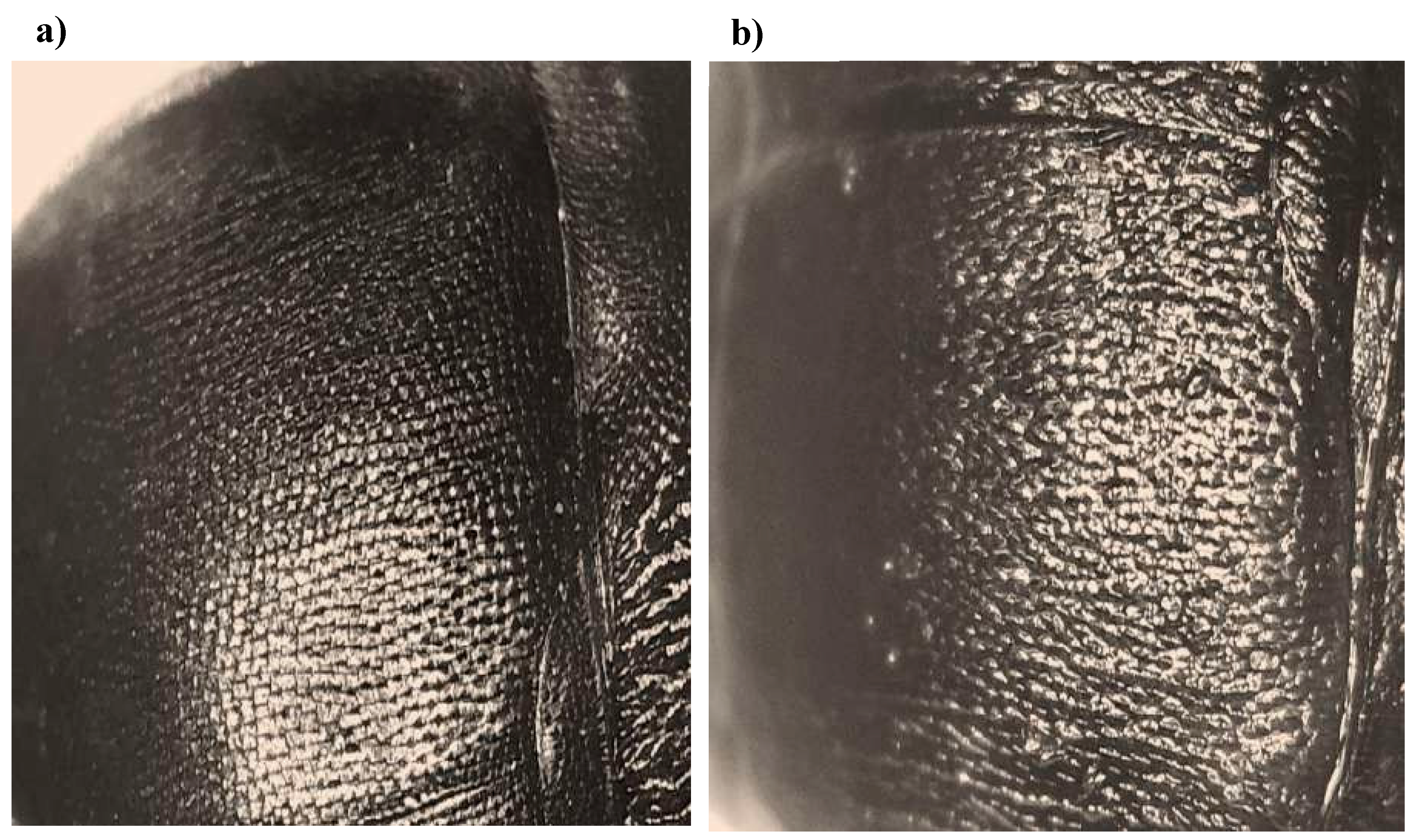

3.6. Choleoptericidal Activity on Larvae and Adults of Aethina tumida

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Langner, T.; Göhre, V. Fungal chitinases: function, regulation, and potential roles in plant/pathogen interactions. Curr Genet. 2016, 62, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, U. Production of chitinases from by-products. of the food: industry application to edible mushrooms and crustaceans. Seville; 2019.

- Bhattacharya, D.; Nagpure, A.; Gupta, R.K. Bacterial chitinases: properties and potential. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2007, 27, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiontek Brzezinska, M.; Jankiewicz, U.; Burkowska, A.; Walczak, M. Chitinolytic microorganisms and their possible application in environmental protection. Curr Microbiol. 2014, 68, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, M.V.; Calzadíaz, L. Industrial enzymes and metabolites from Actinobacteria in food and medicine industry. Actinobacteria - Basics and Biotechnological Applications; InTech, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fu, X.; Yan, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Z. Cloning, expression, purification and application of a novel chitinase from a thermophilic marine bacterium Paenibacillus barengoltzii. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, F.; Diyarza Sandoval, N.A. Potential biological control agents against Fusarium spp. in Mexico: current situation, challenges and perspectives. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cai, J.; Xie, C.-C.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.-H. Purification and partial characterization of a 36-kDa chitinase from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. Colmeri and its biocontrol potential. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2010, 46, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N.; Nath, A.K.; Chauhan, A.; Gupta, R. Purification, characterization, and antifungal activity of Bacillus cereus strain NK91 chitinase from rhizospheric soil samples of Himachal Pradesh, India. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2022, 69, 1830–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.; Garg, N. antifungal activity and protoplast formation by chitinase produced from Bacillus licheniformis NK-7. Biology Fascicle/Analele Universităţii din Oradea. 2022;(1). https://www.bioresearch.ro/2022-1/061-067-AUOFB.29.1.2022-VERMA.K.-Antifungal.activity.and.protoplast.

- Borgi, M.A.; Khila, M.; Boudebbouze, S.; Aghajari, N.; Szukala, F.; Pons, N.; et al. The attractive recombinant phytase from Bacillus licheniformis: biochemical and molecular characterization. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 5937–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Maquat, L.E. lncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3’ UTRs via Alu elements. Nature 2011, 470, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellouli, K.; Ghorbel-Bellaaj, O.; Ayed, H.B.; Manni, L.; Agrebi, R.; Nasri, M. Alkaline-protease from Bacillus licheniformis MP1: Purification, characterization and potential application as a detergent additive and for shrimp waste deproteinization. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimene, I.B.; Tabbene, O.; Gharbi, D.; Mnasri, B.; Schmitter, J.M.; Urdaci, M.-C.; et al. Isolation of a chitinolytic Bacillus licheniformis S213 strain exerting a biological control against Phoma medicaginis infection. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2015, 175, 3494–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.-H.; Won, S.-J.; Moon, J.-H.; Lee, U.; Park, Y.-S.; Maung, C.E.H.; et al. Bacillus licheniformis PR2 controls fungal diseases and increases production of jujube fruit under field conditions. Horticulturae. 2021, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Li, X. List of Coleoptera received from old calabar, on the west coast of Africa. Ann Mag Nat Hist. 1867, 20, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Elzen, P.J. The biology of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, Coleoptera: Nitidulidae): Gaps in our knowledge of an invasive species. Apidologie. 2004, 35, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, W.M. The small hive beetle, Aethina tumida: a review. Bee World. 2004, 85, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K. Beekeeping role in enhancing food security and environmental public health. Health Economics and Management Review 2023, 4, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, T.; Dimitrova, I.; Teneva, A. The development of beekeeping in Bulgaria and the European Union in the last ten years. An overview. Bulgarian Journal of Animal Husbandry/Životnov Dni Nauki 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry 7th ed, W.H. Freeman, 2017.

- Syrový, I.; Hodný, Z. Staining and quantification of proteins separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications 1991, 569, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.C.; Lockwood, J.L. Powdered chitin agar as a selective medium for enumeration of Actinomycetes in water and Soil1. Appl Microbiol. 1975, 29, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monreal, J.; Reese, E.T. The chitinase of Serratia marcescens. Can J Microbiol. 1969, 15, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.R. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Current Protocols Essential Laboratory Techniques 2012, 6, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas Jorge Ismael Tucuch et, a.l. Alternative control of Aethina tumida Murray (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae) with plant powders. Acta Agrícola y Pecuaria 2020, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muras, A.; Romero, M.; Mayer, C.; Otero, A. Biotechnological applications of Bacillus licheniformis. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, N.; et al. Characterization of thermostable chitinase from Bacillus licheniformis B2. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing, 2019; Volume 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laribi-Habchi, H.; Bouanane-Darenfed, A.; Drouiche, N.; Pauss, A.; Mameri, N. Purification, characterization, and molecular cloning of an extracellular chitinase from Bacillus licheniformis stain LHH100 isolated from wastewater samples in Algeria. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015, 72, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menghiu, G.; Ostafe, V.; Prodanovic, R.; Fischer, R.; Ostafe, R. Biochemical characterization of chitinase A from Bacillus licheniformis DSM8785 expressed in Pichia pastoris KM71H. Protein Expr Purif. 2019, 154, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan Ashwini Srividya Shivakumar "Optimization of chitinase produced by a biocontrol strain of Bacillus subtilis using Plackett-Burman design" Eur, J. Exp. Biol 2012, 2, 861–865.

- Jholapara, R.J.; Radhika, S.M.; Chhaya, S.S. Optimization of cultural conditions for chitinase production from chitinolytic bacterium isolated from soil sample. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci 2013, 4, 464–471. [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Chitinase production by Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus licheniformis: their potential in antifungal biocontrol. J Microbiol. 2012, 50, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugaiah, V.; Mathivanan, N.; Balasubramanian, N.; Manoharan, P.T. Optimization of cultural conditions for production of chitinase by Bacillus laterosporous MML2270 isolated from rice rhizosphere soil. African Journal of Biotechnology 2008, 7, 2562–2568. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinska, M.S.; Jankiewicz, U. Production of antifungal chitinase by Aspergillus niger LOCK 62 and its potential role in the biological control. Curr Microbiol. 2012, 65, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y.; Haga, S.; Suzuki, S. Direct antagonistic activity of chitinase produced by Trichoderma sp. SANA20 as biological control agent for grey mould caused by Botrytis cinerea. Cogent Biol. 2020, 6, 1747903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essghaier, B.; Zouaoui, M.; Najjari, A.; Sadfi, N. Potentialities and characterization of an antifungal chitinase produced by a halotolerant Bacillus licheniformis. Curr Microbiol. 2021, 78, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.-H.; Ajuna, H.B.; Won, S.-J.; Choub, V.; Choi, S.-I.; Yun, J.-Y.; et al. The Anti-Termite Activity of Bacillus licheniformis PR2 against the Subterranean Termite, Reticulitermes speratus kyushuensis Morimoto (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). Forests. 2023, 14, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 24 h | 48h | 72h | |||||

| Concentración (U/mL) | Live | Dead | Live | Dead | Live | Dead | Mortality |

| Control | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | 26 | 4 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 3 | 13 % |

| 45 | 22 | 8 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 7 | 30 % |

| 70 | 19 | 11 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 12 | 43 % |

| 115 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 50 % |

| 24 h | 48h | 72h | |||||

| Concentración (U/mL) | Live | Dead | Live | Dead | Live | Dead | Mortality |

| Control | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | 27 | 3 | 27 | 3 | 27 | 3 | 10 % |

| 45 | 23 | 7 | 23 | 7 | 23 | 7 | 23 % |

| 70 | 19 | 11 | 18 | 12 | 18 | 12 | 40 % |

| 115 | 13 | 17 | 13 | 17 | 13 | 17 | 56 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).