1. Introduction

In recent years, the research and development of natural plant components have become a hotspot with the growing concern for healthy diets. Among these components, anthocyanins, as natural antioxidants with multiple biological activities, have attracted much attention. Mulberry, as a traditional Chinese herbal medicine in China, is rich in nutrients, is especially high in anthocyanins, and has high value for development and utilization. Modern pharmacological studies have shown that mulberry contains anthocyanins, polysaccharides, phenolics, alkaloids, flavonoids, resveratrol, and other pharmacologically active ingredients [

1], which provide it with good antioxidant [

2], hypoglycemic [

3], anti-inflammatory [

4], anticancer [

5], hepatoprotective, and neuroprotective properties [

6]. Mulberry is rich in anthocyanins such as cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G), cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside (C3R), and pulsatilloside-3-glucoside (P3G) [

7].

Traditional extraction methods for mulberry anthocyanins primarily involve solvent extraction techniques. However, recent advancements have introduced novel extraction methodologies, such as ultrasonic-assisted extraction and microwave-assisted extraction, which have gained traction due to their environmentally friendly, efficient, and sustainable characteristics. In terms of purification, commonly employed techniques [

8] include large-pore resin adsorption, high-performance liquid chromatography, and membrane separation. While these methods effectively enhance the purity of mulberry anthocyanins, they also present challenges, including operational complexity and high costs [

9].

This study aims to review the extraction and purification techniques for mulberry anthocyanins, alongside their associated biological activities. It will summarize existing research findings, analyze current challenges and issues, and propose future directions for development. The insights provided herein are intended to serve as a reference for further research and industrial applications of mulberry anthocyanins, with the expectation that such investigations will contribute significantly to human health.

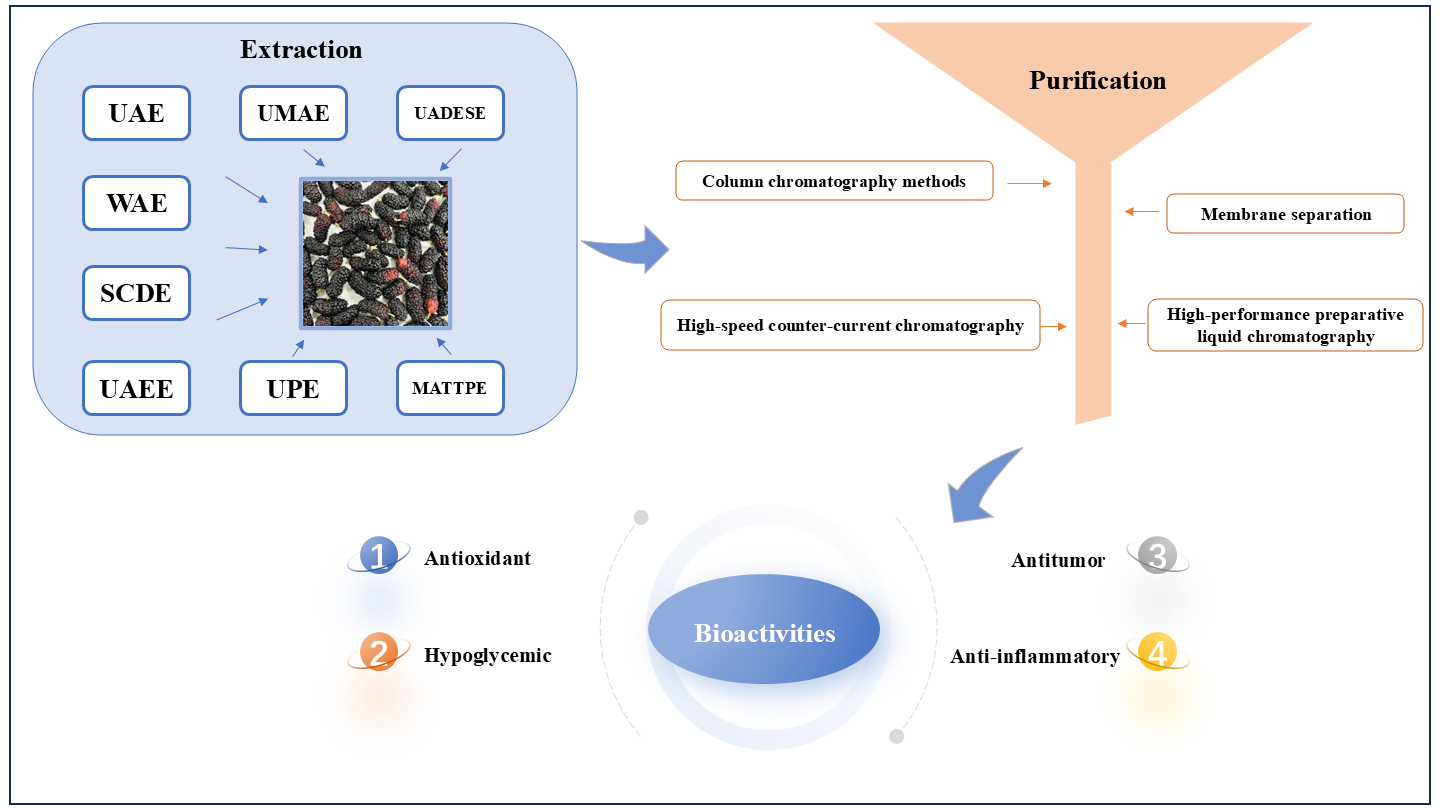

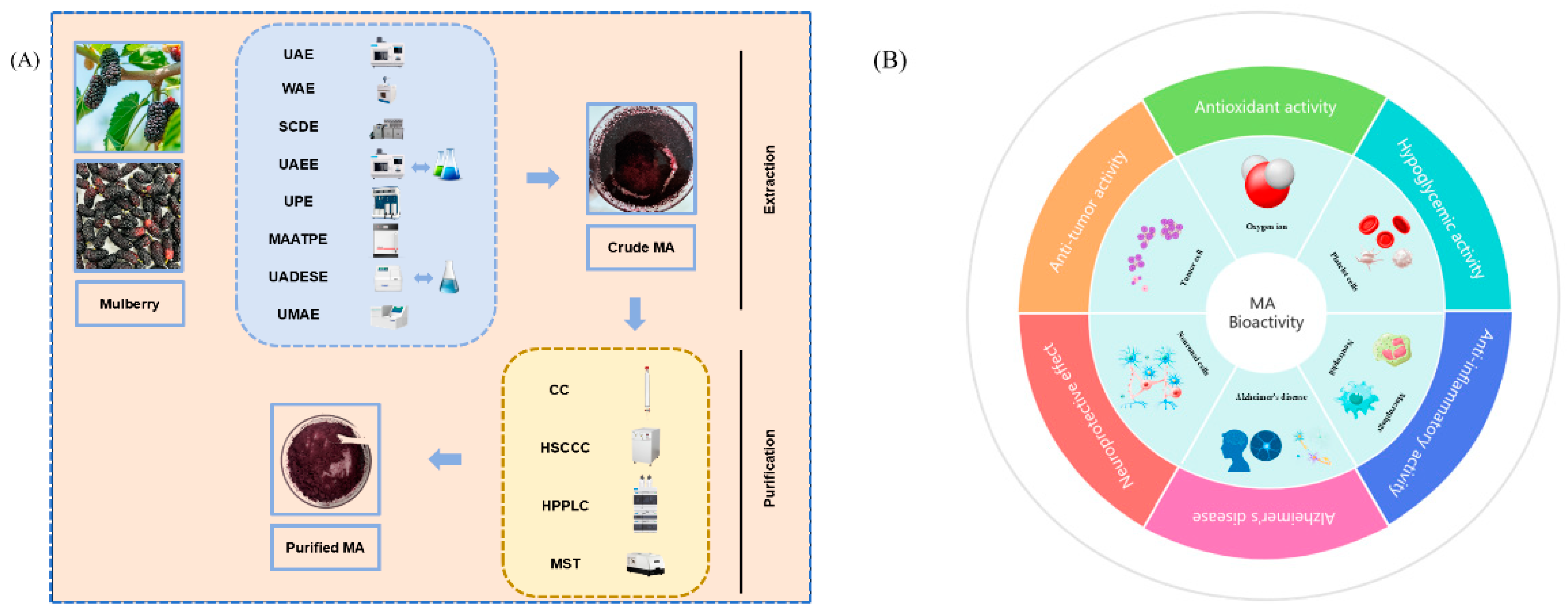

Figure 1.

(A) Different extraction and purification processes of mulberry anthocyanins. (B) Main biological activities of mulberry anthocyanins.

Figure 1.

(A) Different extraction and purification processes of mulberry anthocyanins. (B) Main biological activities of mulberry anthocyanins.

2. Extraction Methods for Mulberry Anthocyanins

The ongoing advancements in extraction technology have led to a heightened recognition of the nutritional and medicinal properties of anthocyanins. Consequently, a variety of both traditional and innovative extraction techniques have been developed over time.

Table 1 presents a summary of the impacts of various extraction methods and processes on the yield of anthocyanins from mulberry over the last five years.

2.1. Solvent Extraction Method (SEM)

The technical principle of the SEM aligns closely with the concept of solubility similarity in dissolution [

26], and the solvents are most commonly acidified water, ethanol, acidified methanol, acetone, or mixed solvents [

27]. Upon reviewing the extraction methods of mulberry anthocyanins in recent years, the optimal conditions for effectively extracting mulberry anthocyanins were identified as an extraction temperature ranging from 20 °C to 60 °C, an extraction time of 44.95 minutes to 3 hours, and a material-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 to 1:31 g/mL [

10,

11,

12,

28]. Therefore, the SEM is widely regarded as a conventional extraction method due to its advantages, including straightforward operation, low equipment requirements, and easy implementation. However, it has issues such as a prolonged extraction time, low efficiency, and high solvent consumption. (thus increasing costs), significant environmental harm from organic solvents, and potential solvent residues. Therefore, the SEM has gradually been replaced by new extraction methods.

To overcome the inherent limitations of conventional solvent extraction, a suite of advanced, high-efficiency extraction techniques has been developed to address the specific challenges posed by traditional methods. Currently, innovative approaches such as ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), ultrahigh-pressure extraction (UPE), supercritical carbon dioxide extraction (SCDE), microwave-assisted two-phase aqueous extraction (MAATPE), ultrasound-assisted deep eutectic solvent extraction (UADESE), and ultrasonic-microwave-assisted extraction (UMAE) are increasingly employed in the extraction of anthocyanins from mulberries and related botanical species.

2.2. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

UAE predominantly employs the physical properties of ultrasound to facilitate the extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials. The principal mechanisms at play include cavitation, mechanical action, thermal effects, and diffusion [

29]. As ultrasound propagates through a liquid medium, it induces cavitation, resulting in high-frequency compressions that create numerous microbubbles. These microbubbles undergo rapid expansion and subsequent collapse due to ultrasonic energy. UAE offers several benefits over other extraction methods, including shorter extraction times, increased efficiency, lower temperatures necessary to avert the thermal degradation of anthocyanins, diminished energy consumption, and improved environmental sustainability.

Table 1 provides an overview of the process conditions for extracting anthocyanins from mulberries using UAE [

14,

15,

16,

17]. While UAE is more efficient than SEM, the cavitation and mechanical effects of ultrasound can partially damage anthocyanin structures in mulberries. Therefore, optimizing parameters like ultrasonic power, solid-to-liquid ratio, temperature, and extraction time is essential to fully leverage its advantages.

2.3. Microwave-Assisted Extraction

MAE leverages ion conduction and dipole relaxation within dielectric materials to isolate target compounds effectively [

30]. This method accelerates solvent heating, diminishes extract viscosity, and enhances the solubility of molecular compounds such as anthocyanins. It additionally disrupts the microstructure of plant cells, thus facilitating the release of anthocyanins into the solvent [

9]. Over the 2020-2024 years MAE has been infrequently applied to mulberry anthocyanins. Wang et al. [

24] employed ethanol/ammonium sulfate as a two-phase extraction solvent with microwave assistance. Response surface optimization revealed that with 39% ethanol (w/w), 13% ammonium sulfate (w/w), a solid-to-liquid ratio of 45:1, a microwave extraction time of 3 minutes, and a microwave power of 480 W, the mulberry anthocyanin recovery reached 86.35 ± 0.32%. Similarly, Liu et al. [

31] used MAE to extract anthocyanins from purple sweet potato, achieving a yield of 31.16 mg/100 g with 30% ethanol, a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:3 g/mL, a microwave power of 320 W, and an extraction time of 500 seconds—significantly higher than the traditional SEM. However, as with UAE, both methods may lead to the structural degradation of mulberry anthocyanins. Thus, controlling factors such as microwave power within a reasonable range is essential to improve yield while preserving anthocyanin structure.

2.4. Ultrahigh-Pressure-Assisted Extraction

UPE is an innovative non-thermal extraction technique designed to preserve the stability of thermally sensitive bioactive compounds, effectively preventing degradation due to heat damage [

32]. Since high pressure does not disrupt the stability of hydrogen and covalent bonds, UPE can effectively break down plant cell walls, enhancing solvent permeability and promoting the release of intracellular active compounds while maintaining their stability [

33]. Compared with the conventional SEM, UPE provides notable benefits, including low energy consumption, a short extraction time, rapid compression, high yield, and straightforward operation, environmental friendliness, and the ability to preserve the stability of bioactive compounds such as anthocyanins [

34,

35].

Although UPE exhibits numerous advantages, there are challenges in its application, including high equipment costs, safety risks, limited solvent selection, high technical requirements, and insufficient adaptation to some bioactive components. Chen et al. [

18] first applied UPE to the extraction of anthocyanins from mulberries and optimized the process conditions by using the Box–Behnken design. The results showed that the predicted yield of mulberry anthocyanins reached 1.99 mg/g with the optimal parameters (extraction pressure of 429.52 MPa, liquid–solid ratio of 12.37:1, and ethanol concentration of 74.19%).

2.5. Combined Extraction Methods

Some combined extraction techniques (e.g., MAATPE, UAEE, UADESE, UMAE) have been progressively applied to the extraction of anthocyanins from mulberries. The UAEE technique significantly increased the yield of anthocyanins from mulberries through the addition of cellulases and pectinases in combination with ultrasonication [

36]. Due to the high specificity of the enzymes, they can be directed to break down specific components of the plant cell wall, thus disrupting the cell wall structure and making it easier to release intracellular components into the solvent. The extraction of target products is further facilitated by the synergistic effect of cavitation and the mechanical effects of ultrasound [

37].

The conventional extraction of mulberry anthocyanins mainly relies on organic solvents, but their toxicity and environmental unfriendliness raise large safety concerns. For this reason, deep eutectic solvents (DESs) are gradually becoming an alternative choice to organic solvents. DESs usually consist of a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and two or three safe and renewable hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) that are capable of easy and large-scale preparation under different reaction conditions [

38]. By modulating the hydrogen bonding interactions between the HBA and HBDs, DESs exhibited good solubility for both polar and nonpolar compounds. Bi et al. [

39] extracted mulberry anthocyanins using DESs coupled with an ultrasound technique. Response surface analysis showed that a choline chloride (ChCl)–lactic acid (HL) ratio of 1:2 was achieved with an extraction time of 31.54 min and an extraction temperature of 57.24 °C for optimal extraction. This study showed that DESs have a significant advantage over conventional solvents, which may be related to the hydrogen bonding network formed between DES components and solute and water molecules. UMAE is another effective method for extracting anthocyanins. A study [

25] showed that the optimal conditions for extracting anthocyanins from mulberry with the UMAE method were a microwave power of 150 W, an ultrasound power of 360 W, an extraction time of 2 min, and a material–liquid ratio of 1:70, and the extraction rate was 13.57±1.30 mg/g under these conditions. The UMAE method combines the cavitation effect of ultrasound and the thermal effect of microwaves, which rapidly destroys the plant cell wall to release the target components, thus effectively improving the extraction efficiency [

40]. However, the equipment cost of this method is high; its application is limited to small-scale laboratory operations, and the effect on some heat-sensitive active ingredients should be considered in practical applications.

Although these combined extraction techniques have shown good results in the laboratory, optimization in terms of equipment and cost is still required for industrial applications. Further improvement of these techniques will provide a more feasible solution for the efficient and environmentally friendly extraction of anthocyanins from mulberries.

3. Purification of Anthocyanins from Mulberries

Mulberry anthocyanin extracts are often accompanied by impurities such as soluble sugars, proteins, and organic acids. The presence of these impurities not only affects the purity of anthocyanins but also weakens their bioactivity and stability, thus adversely affecting the identification and application of anthocyanins. Therefore, the purification of anthocyanins from mulberries is a key step in improving their quality and application value. Currently, anthocyanin purification primarily relies on methods such as column chromatography (the macroporous resin method and ion exchange resin method), membrane separation (MBS), high-speed counter-current chromatography (HSCCC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and combined purification techniques. Each type of method has its own characteristics in terms of purity enhancement, retention of activity, and improvement of extraction efficiency.

3.1. Column Chromatography Methods(CC)

CC is the most widely used method for separating and purifying anthocyanins. Its principle relies on differences in the partition coefficients of anthocyanosides between the solid and liquid phases, enabling the efficient separation of anthocyanosides from impurities [

41]. Commonly used filler resins include macroporous resins, Sephadex-100, and polyamide resins. Macroporous resins can effectively extract target compounds from complex samples due to their porous skeleton structure, absence of ion-exchange groups, high physicochemical stability and mechanical strength, and characteristics of being difficult to break and being unaffected by inorganic salts, strong ions, and low molecular weight compounds [

42]. In addition, macroporous resins are easy to operate, have a low cost and good selectivity, are easy to regenerate, and have fast adsorption [

43]. Huang et al. [

44] compared the purification of mulberry anthocyanins using three macroporous resins (AB-8, D-101, and S-8), and the results showed that the adsorption rate (92.28%) and adsorption capacity (5.54 mg/g) of AB-8 were better than those of the other two resins because of its large specific surface area and moderate pore size, which were more favorable for the adsorption of mulberry anthocyanins. Li et al. [

45] used AB-8 and Sephadex LH-20 for the purification of mulberry anthocyanins, and the whole process was carried out at temperatures lower than 40 °C and protected from light; firstly, deionized water was used to remove sugar impurities, and then 65% ethanol was used for the collection of anthocyanins. Liao et al. [

46] applied a new type of strongly acidic cation exchange resin to purify anthocyanins. They used the new strongly acidic cation exchange resin 001X7 and found that the optimal purification conditions for it were a wash flow rate of 30 mL/min, a pH of 2.17, and washing with 1 mol/L NaCl desorbent for optimal extraction according to high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection (HPLC-DAD) and ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) analyses.

Although CC is currently the main method for the purification of mulberry anthocyanins, its purification amount is small, and it is difficult to realize the purification of mulberry anthocyanins on an industrial scale.

3.2. High-Speed Counter-Current Chromatography (HSCCC)

HSCCC is a chromatographic technique based on liquid–liquid partitioning, and it utilizes two immiscible solvents to form a unidirectional hydrodynamic equilibrium in a high-speed rotating helical tube, effectively avoiding the irreversible adsorption, inactivation, and denaturation of samples [

47]. Compared with traditional chromatographic columns, HSCCC has a high loading capacity, making it suitable for the rapid and large-scale preparation of bioactive compounds [

48].

Y. Chen et al. [

49] purified mulberry anthocyanosides using HSCCC with a solvent system consisting of methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE), n-butanol, acetonitrile, water, and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (30:10:10:50:0.05, v/v). The upper solvent layer was delivered to the column at a pump speed of 40 mL/min and a host speed of 900 rpm, and the lower solvent layer was used as a mobile phase at a flow rate of 10 mL/min at 25 °C. Three monomers, dopamine receptor type 3 (D3R), C3R, and C3G, were successfully separated using this method. Wang, Y. L. (Wang, Y. L., 2023) investigated the isolation and purification of oligomeric proanthocyanidins from green mulberry and their antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities using HSCCC and a solvent system of n-hexane, ethyl acetate, and water (1:20:20, v/v/v), with a mobile-phase flow rate of 2 mL/min, a mainframe rotational speed of 850 rpm, and a temperature controlled at 30 °C; five fractions were obtained through isolation after 500 min. The choice of solvent system is crucial in the HSCCC purification process; this is one of the key challenges in current studies, and it still needs to be further explored and optimized [

50].

3.3. High-Performance Preparative Liquid Chromatography (HPPLC)

HPPLC consists of a stationary phase and a mobile phase, and separations are achieved using adsorption, desorption, and partitioning processes for compounds between the two phases [

51]. The components of mulberry anthocyanins are separated due to their different interaction forces (polarity, molecular size, charge) with the stationary phase, which results in different rates of movement through the column. By adjusting the composition of the mobile phase, the separation can be effectively improved. HPPLC has high selectivity and high resolution, and it can be used to rapidly analyze many types of compounds, including polar, non-polar, and ionic compounds [

52]. Y. T. Li et al. [

45] converted cornflowerin-3-O-rutinoside into cornflowerin-3-O-glucoside using whole-cell catalysis coupled with an aqueous two-phase system (ATPS); this was followed by HPPLC to improve the purity of C3G to 99%. RAN, G. J et al. (RAN, G. J et al. 2019) used medium-pressure preparative liquid chromatography to rapidly prepare high-purity cornflowerin-3-O-glucoside monomers from mulberry. It was shown that the main anthocyanin glycosides in mulberry were C3G, C3R, and malvidin-3-O-glucoside (M3G), and the purity of C3G was improved from 73.56% to 98.72% using the cutting and collecting technique. Despite the high selectivity and resolution of HPPLC in the isolation and purification of anthocyanosides from mulberry, its high cost, complex pretreatment, and large consumption of organic solvents limit its large-scale application. Therefore, more economical and environmentally friendly purification methods should be developed for more efficient industrial applications in the future.

3.4. Membrane Separation Method (MBS)

MBS utilizes the selective permeability of semipermeable membranes to separate the components of a mixture, and it has the advantage of being simple, easy to operate, and able to be carried out at room temperature to avoid structural changes in the sample [

53]. This method usually uses water as the solvent, as it has a low impact on the environment; by selecting appropriate membrane materials and pore sizes, mulberry anthocyanosides of different molecular weights can be separated efficiently without the need to add additional organic chemical reagents, which reduces chemical contamination [

54].

Within the last five years, the applications of the MBS in the purification of anthocyanins from mulberry have been relatively few. Zhao, Y. L. (Zhao, Y. L. 2023) used a 1 KDa polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membrane for the purification of anthocyanins from medicinal mulberries, and the protein and total sugar were effectively retained by the ultrafiltration membrane, with the retention rate reaching 98.9% and 95.53%, respectively; in addition, the color value of anthocyanin was increased by 15 times. In the future, MBS can be combined with raw material pretreatment or with resin adsorption and other technologies to optimize the efficiency of separating mulberry anthocyanosides.

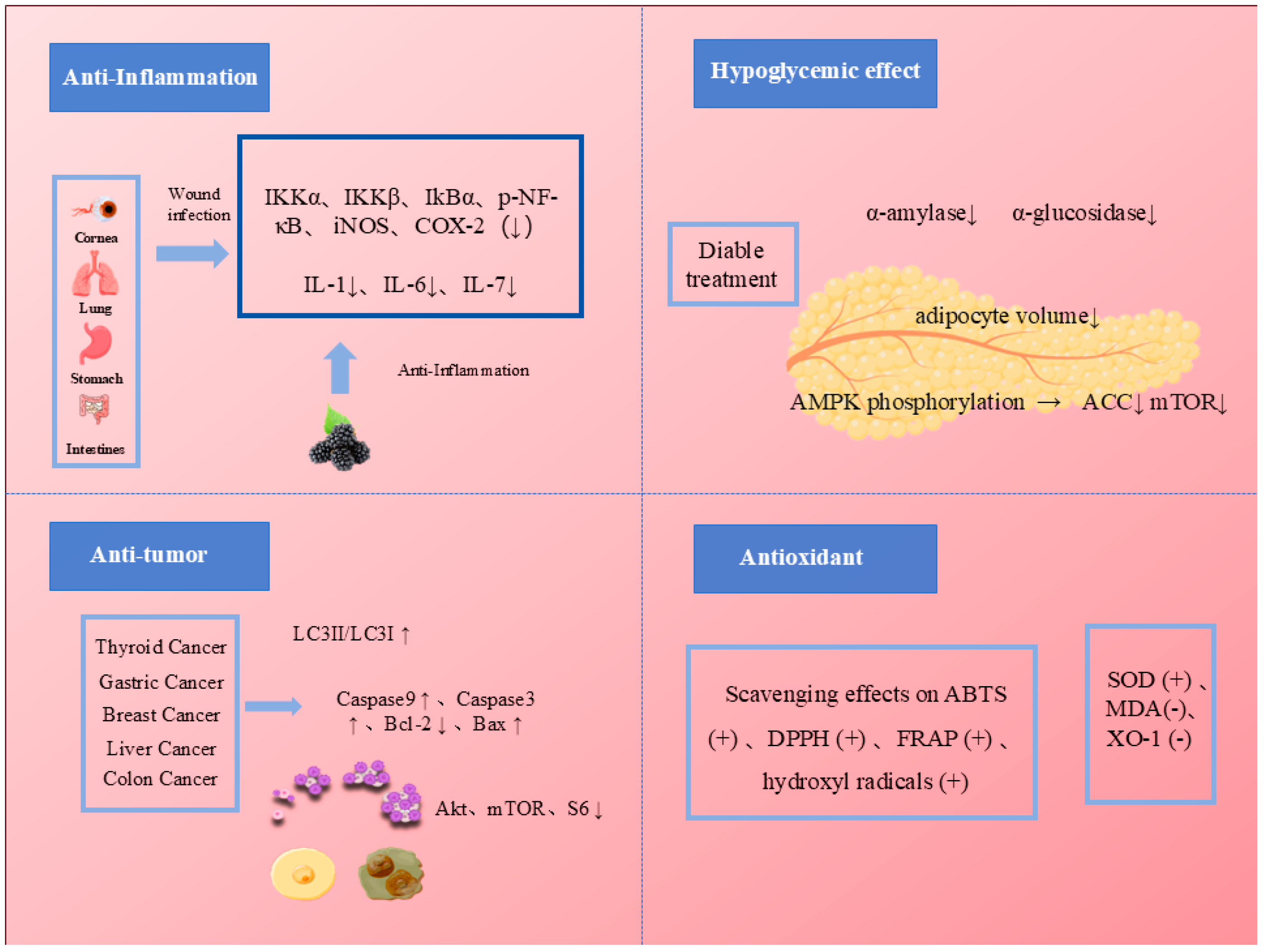

4. Bioactivities of Mulberry Anthocyanins

Mulberry anthocyanins combine with monosaccharides under natural conditions to form anthocyanosides, and their main active components have significant biological activities, like antioxidant, anticancer, hypoglycemic. In view of the potential role of mulberry anthocyanins in disease prevention and health maintenance, this study systematically reviews the current progress of research on their biological activities, aiming to provide a theoretical basis and reference for their application in the development of functional foods and drugs.

Figure 2.

Bioactivities of mulberry anthocyanins.

Figure 2.

Bioactivities of mulberry anthocyanins.

4.1. Antioxidant Activity of Mulberry Anthocyanins

Antioxidant activity is one of the most important indicators for the assessment of bioactive substances, and oxidative stress is currently a key factor in the development of several diseases due to environmental stresses and poor lifestyle habits [

55]. Therefore, research and development of natural products with strong antioxidant activity are important for the prevention and treatment of these diseases. Mulberry anthocyanin, a natural anthocyanoside analog, has been shown to possess significant antioxidant capacity. Huang et al. [

44] investigated the protective effect of mulberry anthocyanin against H2O2-induced damage to vascular endothelial cells (VECs) and found that mulberry anthocyanin restored the H2O2-induced decrease in vascular cell viability and increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) while simultaneously decreasing malondialdehyde (MDA) and xanthine oxidase (XO-1) activities. This study suggests that mulberry anthocyanins can be used as antioxidants in the prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Wang et al. [

24] investigated the scavenging activity of mulberry anthocyanins against 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) and DPPH free radicals and found that the scavenging rates of the two were 96.4±0.76% and 82.52±2.13% respectively, with an antioxidant capacity close to that of vitamin C. Chen et al. [

11] explored the effects of mulberry anthocyanins extracted using different extractants on DPPH and ABTS scavenging, and they found that the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for DPPH scavenging by mulberry anthocyanins extracted using 60% ethanol ranged from 0.056 to 0.180 mg/mL. In addition, this study compared the effects of anthocyanins extracted from mulberries of different ages on ABTS and FRAP scavenging, both of which showed better antioxidant properties than vitamin C.

4.2. Hypoglycemic Ability of Mulberry Anthocyanins

In recent years, mulberry extracts have shown promising applications in hypoglycemia, and their effects are mainly mediated through various pathways, including the enhancement of the insulin signaling pathway, the inhibition of intestinal glycosidase activity, a reduction in gluconeogenesis, and glyco-lipid metabolism for regulating blood glucose [

56]. For example, Fang et al. [

16] studied the hypoglycemic effect of mulberry anthocyanins and found that mulberry anthocyanins can reduce insulin resistance and β-cell apoptosis by improving glucose metabolism and lipid metabolism and reducing oxidative stress, thus indicating that they possess excellent hypoglycemic properties, in addition to ameliorating diabetes. Chen et al. [

18] observed that mulberry anthocyanins could inhibit the activity of α-amylase and α-glucosidase, with the inhibitory effect on both enzymes increasing as their concentration increased. Therefore, this experiment confirmed that mulberry anthocyanins have a potential hypoglycemic effect and have a unique advantage as a natural antioxidant for the prevention or treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Wu et al. [

57] explored the effects of mulberry anthocyanins on high-fat diets and on β cell apoptosis as indicated by weight gain in male high-fat diet (HFD)-fed C57BL/6 mice. The results of the 12-week experiment showed that mulberry anthocyanins effectively reduced body weight gain and improved insulin sensitivity, decreased adipocyte volume, and possessed potential hypoglycemic ability. Yan [

58] explored the effects of mulberry anthocyanins on HepG2 cells and type 2 diabetic mice, focusing on their ability to reduce oxidative damage and regulate protein expression. The intervention with mulberry anthocyanins led to increased phosphorylation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and decreased expression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Additionally, changes were observed in the expression of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38-MAPK) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) in insulin-sensitive tissues. The results demonstrated the potential benefits of MAE in protecting hepatocytes from oxidative stress during hyperglycemia in HepG2 cells and ameliorating dysfunction in diabetic mice by regulating the AMPK/ACC/mTOR pathway. Yan et al. [

59] demonstrated that mulberry anthocyanin attenuates, through the activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) pathway, insulin resistance in HepG2 cells and increases glucose consumption, glucose uptake, and the glycogen content. Compared with conventional hypoglycemic agents, mulberry anthocyanosides have attracted widespread attention due to their natural origin and lower side effects. However, there are still some limitations in the existing studies, such as the inconsistency of results between different experimental models, insufficient safety evaluations for long-term use, and unclear definitions of the effective dose range.

4.3. Antitumor Effects of Mulberry Anthocyanins

In recent years, the antitumor effects of mulberry anthocyanins on a variety of cancers have received widespread attention, and several studies have demonstrated that they significantly inhibit the proliferation and migration of tumor cells by inducing apoptosis and autophagy. For example, a study by Long et al. [

60] demonstrated that mulberry anthocyanins (MAs) significantly inhibited the proliferation and migration of tumor cells by inducing apoptosis and autophagic cell death, and they significantly inhibited thyroid cancer progression. The study analyzed the effects of MAs on SW1736 and HTh-7 cells and found that MAs inhibited the proliferation and migration of these two cell types. Western blotting results showed that MAs increased the LC3II/LC3I ratio and significantly inhibited the activation of AKT, mTOR, and S6 in SW1736 and HTh-7 cells. This study demonstrated that MAs exhibited potential in thyroid cancer therapy by inducing autophagy and inhibiting the activation of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Huang et al. [

61] showed that anthocyanin-rich mulberry extract induced endogenous cancer by activating the p38/p53 and p38/c-jun signaling pathways and induced endogenous and exogenous apoptosis, thereby inhibiting the growth of human gastric cancer cells (AGSs), demonstrating its key role in gastric cancer cell apoptosis. Cho et al. [

62] explored the anticancer effect of cyanidin-3-glucoside from mulberry via caspase-3 cleavage and DNA fragmentation in vitro and in vivo by investigating the mechanism of action of the mulberry anthocyanin C3G in MDA-MB-453 human breast cancer cells, and they found that C3G was able to promote the activation of the caspase-3 enzyme and induce, through the Bcl-2 and Bax pathways, DNA fragmentation of the living cell apoptosis pathway, thus inhibiting the growth of cancer cells. In conclusion, mulberry anthocyanins show significant inhibitory effects on various cancer cells by inducing autophagy and apoptosis; thus, they have potential therapeutic value. However, the relations hip between autophagy and apoptosis and the mechanisms of related signaling pathways still need to be further investigated.

4.4. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Mulberry Anthocyanins

Studies have shown that mulberry anthocyanins (MA) exhibit therapeutic potential in a variety of inflammatory diseases. For example, Mo et al. [

63] observed that MA exhibited a significant protective effect against dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced ulcerative colitis. This effect is attributed to their ability to inhibit colonic oxidative stress and restore the expression of tight junction proteins (e.g., ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-3), thereby mitigating intestinal barrier damage. Additionally, 16S rRNA amplicon analysis revealed that MA improved DSS-induced intestinal dysbiosis by reducing harmful bacteria such as Escherichia–Shigella and increasing beneficial bacteria like Akkermansia, Muribaculaceae, and Allobaculum.. Jung et al. [

64], on the other hand, found that MA effectively alleviated obesity-induced inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction by modulating miR-21, miR-132, and miR-43 expression in white adipose tissue and activating the PGC-1α/SIRT1 pathway in muscle. Another study by D. Lee et al. [

65] found that white mulberry anthocyanin exhibited concentration-dependent nitric oxide (NO) inhibition in macrophages and indicated its potential application in inflammation-related diseases by inhibiting the phosphorylation of IκB kinase alpha (IKKα), IκB kinase beta (IKKβ), inhibitor of kappa B alpha (IkBα), and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB), in addition to the activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). In addition, Lee et al. [

65] showed that mulberry anthocyanin could exert an inhibitory effect on the inflammatory response in dry eyes by decreasing the expression of interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and IL-7 in the cornea and lacrimal gland. In summary, MA exhibits a wide range of anti-inflammatory activities by maintaining intestinal barrier function, modulating inflammatory factors, and improving the microbiota, offering new possibilities for the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

4.5. Other Bioactivities of Mulberry Anthocyanins

Studies have shown that mulberry anthocyanins exhibit a variety of biological activities, such as glycosylation inhibition, antioxidant activity, mitochondrial function improvement, and neuroprotection, with potential therapeutic effects on metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases.

For example, Khalifa et al. [

66] found that mulberry anthocyanins were able to selectively capture dicarbonyl compounds such as glyoxal (GO) and, thus, effectively inhibit the formation of advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs). This mechanism involves GO trapping and covalent and non-covalent binding of mulberry anthocyanins (MAs) to β-lactoglobulin (β-Lg), making MAs functional components with anti-glycation effects. In addition, Yan et al. [

67] showed that mulberry anthocyanin extract reduced glucose-induced oxidative stress in LO2 cells and restored the lifespan of a model organism, Hidradenitis elegans nematode, under hyperglycemic conditions. RNA-seq analysis revealed that MAE treatment induced alterations in the expression of 92 genes, which strengthened the cellular antioxidant defense system and, in turn, attenuated glucose-induced cellular damage. In terms of metabolic improvement, a study by You et al. [

68] found that mulberry anthocyanins (C3G and C3R) significantly upregulated the expression of mitochondrial-biosynthesis-related genes, mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 1/2 (NRF1/NRF2), and they activated the AKT and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathways in brown adipose tissue (BAT)-cMyc cells, which resulted in an increase in BAT-specific uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) gene expression. This result suggests that C3G and C3R may ameliorate metabolic disease symptoms by enhancing the thermogenic capacity of BAT. In addition, Shih et al. [

69] demonstrated in the senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 (SAMP8) and senescence-accelerated mouse resistant 1 (SAMR1) mouse models that mulberry anthocyanin ingestion significantly reduced amyloid β accumulation and modulated MAPK and NRF2 in the brains of mice, thereby activating the antioxidant defense system and contributing to the improvement of memory decline in aged mice. These results suggest that ME has a potential anti-Alzheimer’s effect.

In conclusion, mulberry anthocyanins exhibit important biological activities in metabolism and neuroprotection through multiple biological pathways, and further studies may help to develop their applications in metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases.

5. Concluding Remarks and Prospects

Mulberry anthocyanins have demonstrated significant potential as bioactive compounds, showing antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and metabolic regulatory effects. As reviewed, advancements in extraction and purification techniques, such as UAE, MAE, UPE, have greatly improved the yield and stability of mulberry anthocyanins, while various purification approaches, including HSCCC and HPPLC, have enhanced the purity and application potential. However, industrial-scale applications remain challenging due to factors such as high costs, complex procedures, and equipment limitations.

In terms of bioactivities, mulberry anthocyanins have shown promising therapeutic effects in multiple disease models. Their ability to mitigate oxidative stress, inhibit inflammatory pathways, and regulate cancer cell apoptosis and autophagy highlights their value as natural health-supporting agents. However, the precise molecular mechanisms, especially the interactions with signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and NRF2, require further elucidation. Additionally, their role in modulating gut microbiota and metabolic health warrants more in-depth exploration, particularly through clinical trials.

Future research should focus on optimizing extraction and purification methods to make them more cost-effective and environmentally sustainable, which would facilitate their commercial application. Furthermore, studies exploring the bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of mulberry anthocyanins will be crucial for understanding their efficacy in human health applications. With comprehensive investigations of dosage, long-term safety, and synergistic effects with other bioactive compounds, mulberry anthocyanins hold promise as natural therapeutic agents for combatting a variety of chronic diseases.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All relevant ethical safeguards have been met in relation to patient or subject protection, or animal experimentation.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the “Thirteenth Five-Year Plan” for National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2016YFD0400903), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31471923), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32202120), and the Zhuhai College of Science and Technology “Three Levels” Talent Construction Project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Wen, P.; Hu, T.G.; Linhardt, R.J.; Liao, S.T.; Wu, H.; Zou, Y.X. Mulberry: A review of bioactive compounds and advanced processing technology. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 83, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.C.; Zhang, R.J.; Wang, J.Y.; Tong, Y.C.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.Z.; Zhang, H.S.; Abbas, Z.; Si, D.Y.; Wei, X.B. Isolation, Characterization, and Functional Properties of Antioxidant Peptides from Mulberry Leaf Enzymatic Hydrolysates. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.H.; Liu, F.; Xiong, L. Medicinal parts of mulberry (leaf, twig, root bark, and fruit) and compounds thereof are excellent traditional Chinese medicines and foods for diabetes mellitus. J. Funct. Food. 2023, 106, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kwon, J.W. Anti-inflammatory effect of mulberry anthocyanins on experimental dry eye. Acta Ophthalmol. 2024, 102, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cui, S.Y.; Dan, C.Y.; Li, W.L.; Xie, H.Q.; Li, C.H.; Shi, L.E. Phellinus baumii Polyphenol: A Potential Therapeutic Candidate against Lung Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhao, X.Y.; Liu, K.F.; Yang, X.T.; He, Q.Z.; Gao, Y.L.; Li, W.N.; Han, W.W. Mulberry Leaf Compounds and Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease and Diabetes: A Study Using Network Pharmacology, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, and Cellular Assays. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.L.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.X.; Jin, Q.; Zhu, Z.X.; Dong, Z.X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yu, C. Transcriptomic Analysis Provides Insights into Anthocyanin Accumulation in Mulberry Fruits. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.Q.; Han, Y.M.; Han, B.; Qi, X.M.; Cai, X.; Ge, S.Q.; Xue, H.K. Extraction and purification of anthocyanins: A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.H.; Zhong, W.T.; Yang, C.M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Yang, D.S. Study on anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr via ultrasonic microwave synergistic extraction and its antioxidant properties. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Xu, Y.; Shishir, M.R.I.; Zheng, X.; Chen, W. Green extraction of mulberry anthocyanin with improved stability using β-cyclodextrin. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2018, 99, 2494–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Mokhtar, R.A.M.; Sani, M.S.A.; Noor, N. The Effect of Maturity and Extraction Solvents on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Mulberry (Morus alba) Fruits and Leaves. Molecules 2022, 27, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suriyaprom, S.; Kaewkod, T.; Promputtha, I.; Desvaux, M.; Tragoolpua, Y.J.P. Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of white mulberry (Morus alba L.) fruit extracts. 2021, 10, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budiman, A.; Praditasari, A.; Rahayu, D.; Aulifa, D.L.J.J.o.P.; Sciences, B. Formulation of antioxidant gel from black mulberry fruit extract (Morus nigra L.). 2019, 11, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, S.; Senavongse, R.; Papayrata, C.; Chumroenphat, T.J.H. Evaluation of color, phytochemical compounds and antioxidant activities of mulberry fruit (Morus alba L.) during ripening. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jiang, X.; Huang, G.; Xin, X.; Attaribo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Gui, Z.J.S. Preparation and characterization of methylated anthocyanins from mulberry fruit with iodomethane as a donor. Anthocyanins 2019, 59, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.L.; Jia, S.S.; Lin, Y.; Yuan, K.; Jin, S.H. Extraction, Purification, Content Analysis and Hypoglycemic Effect of Mulberry marc Anthocyanin. Pharmacognosy Magazine 2020, 16, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.; Pinela, J.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Añibarro-Ortega, M.; Pires, T.; Saldanha, A.L.; Alves, M.J.; Nogueira, A.; Ferreira, I.; Barros, L. Extraction of Anthocyanins from Red Raspberry for Natural Food Colorants Development: Processes Optimization and In Vitro Bioactivity. Processes 2020, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.L.; Ma, J.; Li, P.; Wen, B.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.H.; Huang, W.Y. Preparation of hypoglycemic anthocyanins from mulberry (Fructus mori) fruits by ultrahigh pressure extraction. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2023, 84, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannou, O.; Oussou, K.F.; Chabi, I.B.; Awad, N.M.; Aïssi, M.V.; Goksen, G.; Mortas, M.; Oz, F.; Proestos, C.; Kayodé, A.P.J.N. Nanoencapsulation of Cyanidin 3-O-Glucoside: Purpose, technique, bioavailability, and stability. 2023, 13, 617. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tao, F.; Wang, Y.; Cui, K.; Cao, J.; Cui, C.; Nan, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z. Process optimization for enzymatic assisted extraction of anthocyanins from the mulberry wine residue. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2020, 559. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Khan, M.A.; Yan, Z.; Beta, T. Ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic extraction and identification of anthocyanin components from mulberry wine residues. Food Chem 2020, 323, 126714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Chi, X.; Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Q.; Ding, C.; Yang, R.; Jiang, L. Highly efficient extraction of mulberry anthocyanins in deep eutectic solvents: Insights of degradation kinetics and stability evaluation. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2020, 66. [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Ping, K.; Jiang, Y.W.; Wang, L.T.; Niu, L.J.; Liu, Z.M.; Fu, Y.J. Natural deep eutectic solvents couple with integrative extraction technique as an effective approach for mulberry anthocyanin extraction. Food Chem 2019, 296, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Q.; Cui, H.P.; Zong, K.L.; Hu, H.C.; Yang, J.T. Extraction of functional natural products employing microwave-assisted aqueous two-phase system: application to anthocyanins extraction from mulberry fruits. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 54, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Yan, X.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, C.J.C.C. Optimization of ultrasonic-microwave assisted extraction of anthocyanins from mulberry and theirs antioxidant activities. 2020, 45, 172–178. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Collins, T.; Walsh, K.; Naiker, M. Solvent extractions and spectrophotometric protocols for measuring the total anthocyanin, phenols and antioxidant content in plums. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 4481–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangrat, R.; Williams, P.T.; Saengcharoenrat, P. Subcritical solvent extraction of total anthocyanins from dried purple waxy corn: Influence of process conditions. J. Food Process Preserv. 2017, 41, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman, A.; Praditasari, A.; Rahayu, D.; Aulifa, D.L. Formulation of Antioxidant Gel from Black Mulberry Fruit Extract (Morus nigra L.). J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2019, 11, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, I.M.; Taher, Z.M.; Rahmat, Z.; Chua, L.S. A review of ultrasound-assisted extraction for plant bioactive compounds: Phenolics, flavonoids, thymols, saponins and proteins. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Salazar, H.; Camacho-Díaz, B.H.; Ocampo, M.L.A.; Jiménez-Aparicio, A.R. Microwave-assisted Extraction of Functional Compounds from Plants: A Review. BioResources 2023, 18, 6614–6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, C.; Zhou, C.; Wen, Z.; Dong, X. An improved microwave-assisted extraction of anthocyanins from purple sweet potato in favor of subsequent comprehensive utilization of pomace. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2019, 115, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Meng, F.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Z. Effects of ultrahigh pressure extraction conditions on yields and antioxidant activity of ginsenoside from ginseng. Separation and Purification Technology 2009, 66, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J. Effect of High Pressure Processing on the Extraction of Lycopene in Tomato Paste Waste. Chemical Engineering & Technology 2006, 29, 736–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Aslam, R.; Makroo, H.A. High pressure extraction and its application in the extraction of bio-active compounds: A review. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2018, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Lee, H.J.; Yu, H.J.; Ju do, W.; Kim, Y.; Kim, C.T.; Kim, C.J.; Cho, Y.J.; Kim, N.; Choi, S.Y.; et al. A comparison between high hydrostatic pressure extraction and heat extraction of ginsenosides from ginseng (Panax ginseng CA Meyer). J Sci Food Agric 2011, 91, 1466–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Dong, H.; Li, L.; Chen, G. Comparison of different drying pretreatment combined with ultrasonic-assisted enzymolysis extraction of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2024, 107, 106933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umego, E.C.; He, R.; Ren, W.; Xu, H.; Ma, H. Ultrasonic-assisted enzymolysis: Principle and applications. Process Biochemistry 2021, 100, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal-Abidin, M.H.; Hayyan, M.; Hayyan, A.; Jayakumar, N.S. New horizons in the extraction of bioactive compounds using deep eutectic solvents: A review. Analytica Chimica Acta 2017, 979, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Chi, X.; Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Q.; Ding, C.; Yang, R.; Jiang, L. Highly efficient extraction of mulberry anthocyanins in deep eutectic solvents: Insights of degradation kinetics and stability evaluation. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2020, 66, 102512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.X.; Meng, X.J.; Tan, C.; Tong, Y.Q.; Wan, M.Z.; Wang, M.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, H.T.; Kong, Y.W.; Ma, Y. Composition and antioxidant activity of anthocyanins from Aronia melanocarpa extracted using an ultrasonic-microwave-assisted natural deep eutectic solvent extraction method. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2022, 89, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, M.M.; Wang, W.J.; Zheng, G.D.; Yin, Z.P.; Chen, J.G.; Zhang, Q.F. Separation and purification of anthocyanins from Roselle by macroporous resins. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 161, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Su, J.Q.; Chu, X.L.; Zhang, X.Y.; Kan, Q.B.; Liu, R.X.; Fu, X. Adsorption and Desorption Characteristics of Total Flavonoids from Acanthopanax senticosus on Macroporous Adsorption Resins. Molecules 2021, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.F.; Nie, W.; Cui, Y.P.; Yue, F.L.; Fan, X.T.; Sun, R.Y. Purification with macroporous resin and antioxidant activity of polyphenols from sweet potato leaves. Chem. Pap. 2024, 78, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xie, C.; Wu, C.; Li, T.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.; Yang, X.; Fan, G. Purification of mulberry anthocyanins by macroporous resin and its protective effect against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in vascular endothelial cells. Food Bioscience 2024. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.T.; Huang, T.; Wang, J.Z.; Yan, C.H.; Gong, L.C.; Wu, F.A.; Wang, J. Efficient acquisition of high-purity cyanidin-3-O-glucoside from mulberry fruits: An integrated process of ATPS whole-cell transformation and semi-preparative HPLC purification. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Battino, M.; Giampieri, F.; Bai, W.; Tian, L. Recovery of value-added anthocyanins from mulberry by a cation exchange chromatography. Curr Res Food Sci 2022, 5, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spórna-Kucab, A.; Jerz, G.; Kumorkiewicz-Jamro, A.; Tekieli, A.; Wybraniec, S. High-speed countercurrent chromatography for isolation and enrichment of betacyanins from fresh and dried leaves of Atriplex hortensis L. var. “Rubra”. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44, 4222–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Yang, X.; Wang, N.N.; Li, H.M.; Zhao, J.Y.; Li, Y.L. Separation of six compounds including two n-butyrophenone isomers and two stibene isomers from Rheum tanguticum Maxim by recycling high speed counter-current chromatography and preparative high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2018, 41, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Du, F.; Wang, W.; Li, Q.; Zheng, D.H.; Zhang, W.J.; Zhao, T.; Mao, G.H.; Feng, W.W.; Wu, X.Y.; et al. Large-scale isolation of high-purity anthocyanin monomers from mulberry fruits by combined chromatographic techniques. J. Sep. Sci. 2017, 40, 3506–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Z.Z.; Liao, X.J.; Chen, A.L.; Yang, S.M. Isolation of strawberry anthocyanins using high-speed counter-current chromatography and the copigmentation with catechin or epicatechin by high pressure processing. Food Chem. 2018, 247, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Chen, D.; Ye, J.; Lu, Y.; Dai, Z. Preparative separation of three terpenoids from edible brown algae Sargassum fusiforme by high-speed countercurrent chromatography combined with preparative high-performance liquid chromatography. Algal Research 2021, 59, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Huai, J.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Zhuang, L.; Zhang, J. An online preparative high-performance liquid chromatography system with enrichment and purification modes for the efficient and systematic separation of Panax notoginseng saponins. Journal of Chromatography A 2023, 1709, 464378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cissé, M.; Vaillant, F.; Pallet, D.; Dornier, M. Selecting ultrafiltration and nanofiltration membranes to concentrate anthocyanins from roselle extract (Hibiscus sabdariffa L). Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2607–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.; Díaz-Montaña, E.J.; Asuero, A.G. Recovery of Anthocyanins Using Membrane Technologies: A Review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2018, 48, 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockermann, P.; Lizio, R.; Hansmann, J. Healthberry 865® and a Subset of Its Single Anthocyanins Attenuate Oxidative Stress in Human Endothelial In Vitro Models. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Chai, T.; Xu, H.; Du, H.-y.; Jiang, Y. Mulberry leaf multi-components exert hypoglycemic effects through regulation of the PI-3K/Akt insulin signaling pathway in type 2 diabetic rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2024, 319, 117307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Qi, X.M.; Liu, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhu, R.Y.; Chen, W.; Zheng, X.D.; Yu, T. Dietary supplementation with purified mulberry (Morus australis Poir) anthocyanins suppresses body weight gain in high-fat diet fed C57BL/6 mice. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.J.; Zheng, X.D. Anthocyanin-rich mulberry fruit improves insulin resistance and protects hepatocytes against oxidative stress during hyperglycemia by regulating AMPK/ACC/mTOR pathway. J. Funct. Food. 2017, 30, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.J.; Dai, G.H.; Zheng, X.D. Mulberry anthocyanin extract ameliorates insulin resistance by regulating PI3K/AKT pathway in HepG2 cells and db/db mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 36, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Zhang, F.F.; Wang, H.L.; Yang, W.S.; Hou, H.T.; Yu, J.K.; Liu, B. Mulberry anthocyanins improves thyroid cancer progression mainly by inducing apoptosis and autophagy cell death. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.P.; Chang, Y.C.; Wu, C.H.; Hung, C.N.; Wang, C.J. Anthocyanin-rich Mulberry extract inhibit the gastric cancer cell growth in vitro and xenograft mice by inducing signals of p38/p53 and c-jun. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1703–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Chung, E.Y.; Jang, H.-Y.; Hong, O.-Y.; Chae, H.S.; Jeong, Y.-J.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, B.-S.; Yoo, D.J.; Kim, J.-S.J.A.-C.A.i.M.C. Anti-cancer effect of cyanidin-3-glucoside from mulberry via caspase-3 cleavage and DNA fragmentation in vitro and in vivo. 2017, 17, 1519–1525. [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.L.; Ni, J.D.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.T.; Karim, N.; Chen, W. Mulberry Anthocyanins Ameliorate DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis by Improving Intestinal Barrier Function and Modulating Gut Microbiota. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Lee, M.S.; Chang, E.; Kim, C.T.; Kim, Y. Mulberry (Morus alba L.) Fruit Extract Ameliorates Inflammation via Regulating MicroRNA-21/132/143 Expression and Increases the Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Content and AMPK/SIRT Activities. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, S.R.; Kang, K.S.; Kim, K.H. Bioactive Phytochemicals from Mulberry: Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, I.; Xia, D.; Dutta, K.; Peng, J.M.; Jia, Y.Y.; Li, C.M. Mulberry anthocyanins exert anti-AGEs effects by selectively trapping glyoxal and structural-dependently blocking the lysyl residues of β-lactoglobulins. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 96, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, F.J.; Chen, X.A.; Zheng, X.D. Protective effect of mulberry fruit anthocyanin on human hepatocyte cells (LO2) and Caenorhabditis elegans under hyperglycemic conditions. Food Res. Int. 2017, 102, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.L.; Liang, C.; Han, X.; Guo, J.L.; Ren, C.L.; Liu, G.J.; Huang, W.D.; Zhan, J.C. Mulberry anthocyanins, cyanidin 3-glucoside and cyanidin 3-rutinoside, increase the quantity of mitochondria during brown adipogenesis. J. Funct. Food. 2017, 36, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, P.H.; Chan, Y.C.; Liao, J.W.; Wang, M.F.; Yen, G.C. Antioxidant and cognitive promotion effects of anthocyanin-rich mulberry (Morus atropurpurea L.) on senescence-accelerated mice and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).