1. Introduction

City branding has become a global phenomenon [

1] that not only large cities like London, New York, Shanghai or Paris have adopted, but also developing cities like Medellín-Colombia, Malaga-Spain, or Coimbra-Brazil, have found branding a city as a way to promote their tangible and intangible attributes to compete. Cities have learned that positioning their brands is a strategic asset for the process of internationalization, to attract not only resources from exports or products or services, foreign direct investment, tourism or international cooperation, but also to attract talents or [

2].

City branding has become crucial for urban competition and survival [

3], as regions increasingly enter into this competitive landscape, a coordinated and strategic approach is necessary to gather as much information as possible from different stakeholders [

4] this way, the city’s projected image truly reflects the appropriate values from the territory.

As Cities are learning systems that borrow knowledge from business practices [

5], the creation of a strong image requires the participation of different actors to plan, design, execute and measure strategies that let the cities achieve their goals in the international field.

Stakeholders have been widely described in the literature as a fundamental part for the co-creation of the brand [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] and their participation in the place branding process has been rated as “extremely relevant” [

12]. The citizens have also been subject of study, not only in the creation of those images and marketing campaigns, but also for its evaluation.

From the previous discussions, this study has settled as goal to perform a structured literature review and bibliometric analysis to identify how the different stakeholders have participated in the evaluation of the city projected images with the use of neuromarketing techniques. The authors extracted from the literature the main variables related to these evaluations and how their perceptions were measured. As the city brand perceptions affects directly the cities’ global competitiveness, additionally, it provides valuable information to develop new marketing strategies that are useful for the territories long term planning.

A total of 92 articles were analyzed to develop this systematic review. The findings are divided into two main topics: the measurement of perceptions towards city branding within the different stakeholders, and the implementation of the neuromarketing techniques towards city brands. This way, the reader can understand the approaches that have been studied related to these themes.

2. Materials and Methods

Following the PRISMA model, which is a method that integrates methodological and conceptual frameworks for literature reviews [

13], it seeks to reduce biases and errors in the analysis and guarantee relevant findings [

14]. This method consists of several phases, as shown in

Table 1, the first part is the definition of the keywords and the information search string, in an open period that was updated until July 30th of 2024 and following the research question that was established: what are the neuromarketing strategies that have been used to measure perceptions towards city brands?

To achieve this goal, we carried out two searches in two databases without limitation of publishing date: Web of Science and Scopus. Firstly, WOS represents the most consulted database in bibliometric analysis [

15,

16]. On the other hand, Alaloul et al., [

17] comment on the advantages of performing queries with SCOPUS because it allows consulting the largest number of abstracts worldwide, covering more than 21,000 titles and providing a large number of metrics for these documents. The main advantage is that both sources provide a holistic view of the most recent research in any field of knowledge [

14].

The data collection was divided in two moments: the first one consisting of the identification of perceptions associated with city-brands or place-brands, the query and findings are available in

Table 2, and the second, the objective was to identify the neuromarketing strategies that have been applied in studies related with cities, the results of this search are available in

Table 3.

All the articles identified within the searches were subject of an abstract revision by two researchers with inclusion criteria considering the relevance of the keywords whether in the abstract or in the title and that its content it’s related to the topic of research; while the third researcher acted as referee to resolve disagreements on the inclusion of the articles and avoid bias. Once the abstracts were screened, a complete revision of the content of the articles was performed by the three researchers, identifying key aspects that will be shown in the Findings section.

All the references of the articles included in this study were uploaded into Mendeley reference manager, and then its consolidated data was implemented on VOS Viewer and Litmaps for the bibliometric analysis.

During the articles screening, we followed the PRISMA model establishing the strategies applied, eligibility criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria. Litmaps was used as bibliographic resource to identify the repeated documents.

The articles included in the revision included both qualitative and quantitative studies. Only articles written in English and Spanish were considered for the revision.

2.1. Data Selection Plan

The three researchers that participated in the study, examined all the titles and abstracts to minimize the risk of selection. To increase the coherence between the researchers, the results were discussed, and then, the selection and extraction of the data was modified.

2.2. Ethic Considerations

The project where this systematic review was developed, was revised and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Politécnico Grancolombiano University.

3. Results

3.1. First Literature Review: Citizen’s Perceptions Towards City Brand

When the search keys were entered into the databases, “Citizen-Perception” AND Place-Brand”, in Scopus, no results were found; as the researchers changed the word “Place” for “City” to extend the query, two articles were found. In the Web of Science: For the first query, Citizen-Perception and Place-Brand no articles were found either, after changing the word place for city, the results were the same.

With this panorama, the researchers decided to amplify the query, eliminating the word citizen from the search, leaving the searches on both databases as described on

Table 1 and now obtaining 101 results on Scopus and 235 in the Web of Science. After combining the two databases' results, the researchers identified 40 duplicates, then a revision of the 296 abstracts was conducted to consider only articles that were related to the topic of research; in this case, 74 articles were selected as final. The

Table 4 represents the distribution of the articles by stakeholders.

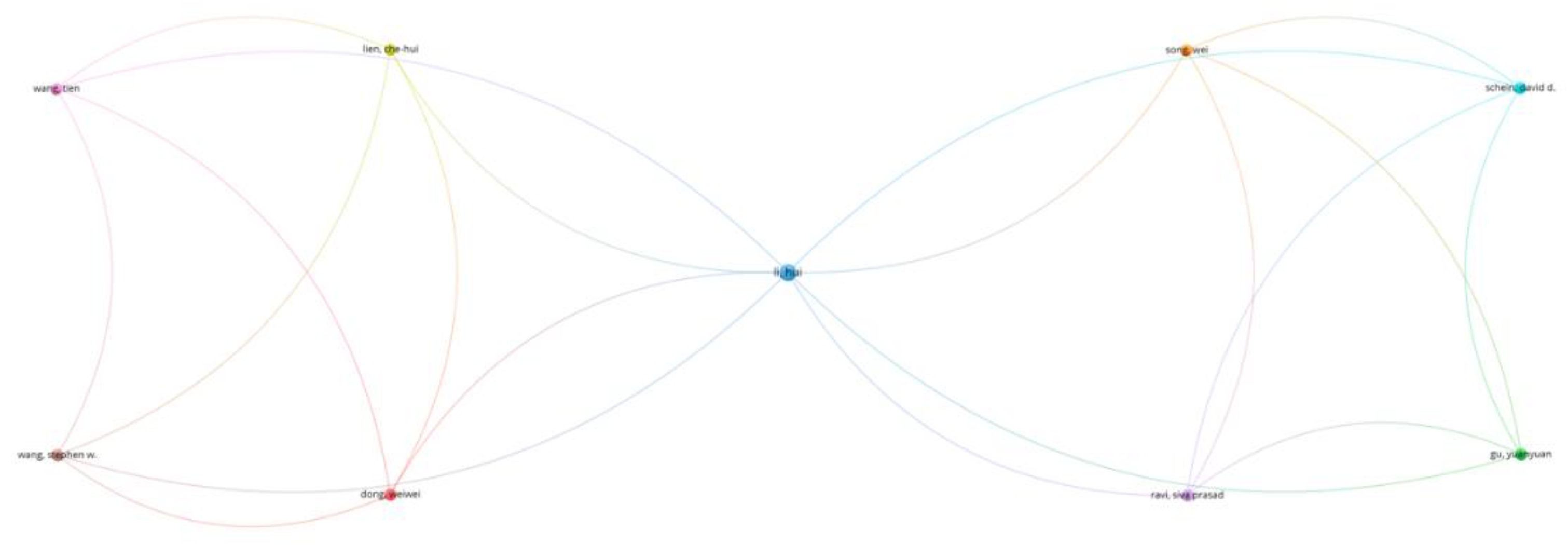

To understand the collaborative landscape within the field of place brand and city branding perception studies, a co-authorship analysis was conducted using the VOSviewer software. This analysis considered all authors found in Scopus and the Web of Science. The system calculated the link strength between authors based on the frequency of their co-authorship. The initial visualization aimed to map the entire network of collaborating authors to identify key research clusters and prominent contributors in the field.

However, the analysis revealed a fragmented co-authorship network within the dataset. Despite including all authors with a minimum of one publication, the overall connectivity among researchers was limited. Consequently, VOSviewer only presented the largest connected component of the network, which comprised a cluster of 9 authors, as shown in

Figure 1.

These authors demonstrated direct co-authorship ties among themselves, indicating a specific area of more intensive collaboration within the broader research field. The remaining authors in the database did not exhibit sufficient co-authorship links to be included in this visualized network, suggesting a potentially diverse and less interconnected research landscape in the study of place brand and city branding perceptions.

Figure 1, shows that Hui Li, was the most connected author within the authors, citing and being cited in this research topic.

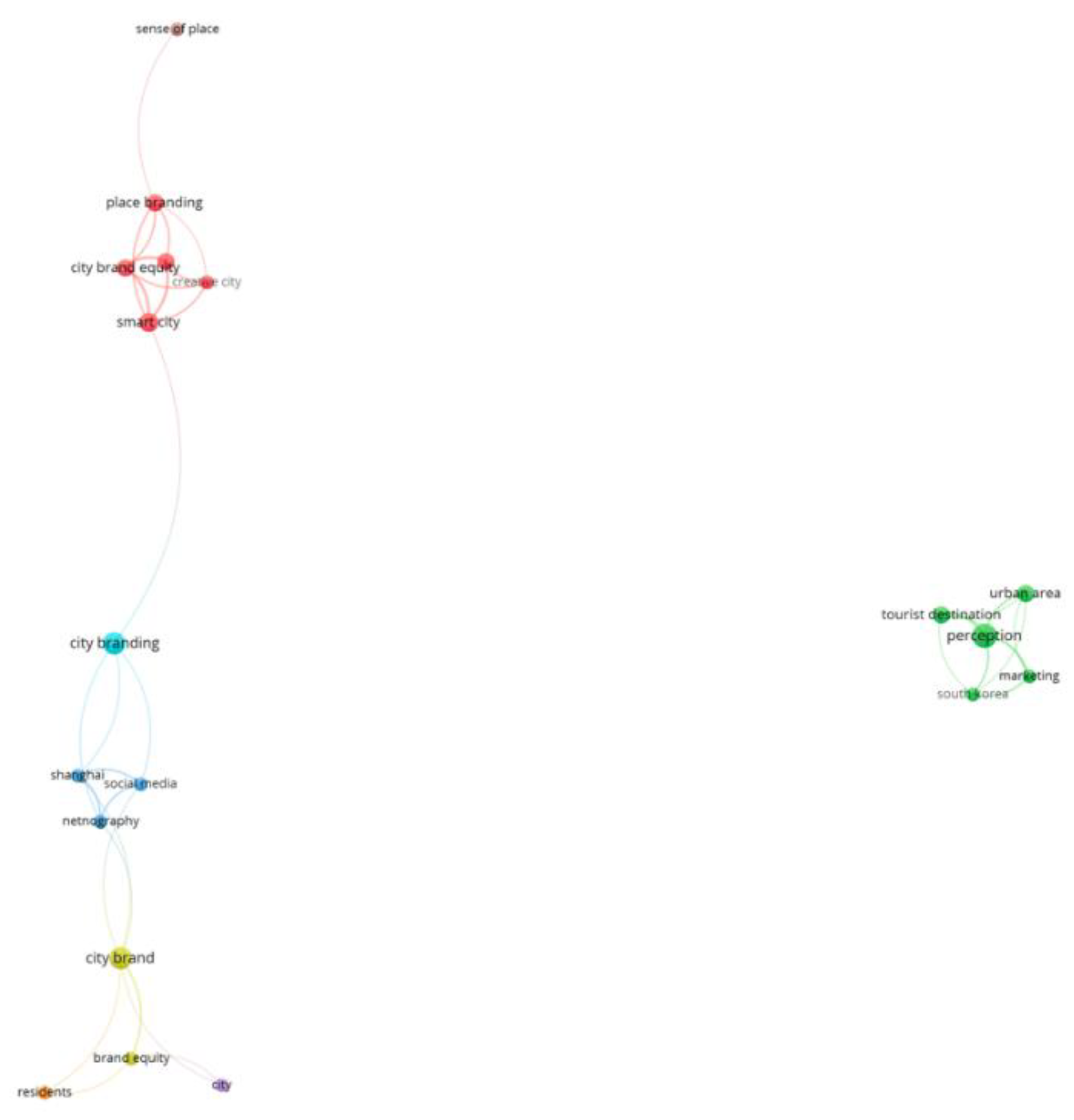

Then, to explore the key themes and concepts within the place brand and city branding perception literature, a co-occurrence analysis of keywords was also performed. This analysis utilized the same database of studies, which contained a total of 136 keywords. To focus on the most relevant and frequently discussed topics, a minimum co-occurrence threshold of 2 was established. This criterion was met by 19 keywords, which were then visualized to identify clusters of terms that frequently appear together in the literature.

The resulting visualization revealed several distinct clusters of co-occurring keywords, indicating different thematic areas within the research. The results are presented in

Figure 2, where a prominent cluster (represented in red) includes terms such as

place branding, city brand equity, smart city, city branding, and

city brand, suggesting a significant body of work focusing on the strategic development and management of city and place brands, often in the context of technological advancements.

Another cluster (in green) features keywords like urban area, tourist destination, perception, and marketing, highlighting research centered on how cities and places are perceived by visitors and the role of marketing in shaping these perceptions. Additionally, a smaller cluster (in blue) connects Shanghai, social media, and netnography, indicating a focus on using digital methodologies to study place perceptions in specific urban contexts.

Furthermore, the analysis identified other relevant keywords forming separate nodes or smaller clusters. For instance, brand equity and residents appear together (in yellow), suggesting studies that examine brand equity from the perspective of the local population. Interestingly, the term sense of place appears as an isolated node, indicating its relevance as a concept within the field but perhaps with less direct co-occurrence with the other highly frequent keywords in this specific dataset. The separated nature of these clusters suggests the existence of distinct, though potentially related, research streams within the broader field of place brand and city branding perception studies.

3.2. Second Literature Review: Neuromarketing Strategies Applied to Cities

Considering that the neuromarketing is a discipline that studies the brain process that explains the decision taking in humans in the field of action of traditional marketing: marketing intelligence, product and service design, pricing, branding and promotion, the neuromarketing studies have centered in brand analysis and the consumer behavior [

92]. Implementing neuromarketing in market research, allows examining sensomonoitor, cognitive and affective responses that consumer have toward advertisement, brands and other marketing elements.

Neuromarketing strategies have also been applied in cities for its branding, thus, the second literature review was carried out using the terms “Neuromarketing” AND “city” OR “cities” as result, 8 articles were found in Scopus and 12 in the Web of Science, with one repeated between databases, 19 documents were taken for abstract revision. Only one article addressed the interested topic of research in which, the authors highlight that no other applications of neuromarketing have been used as methods to study destination marketing nor other aspects of tourism yet [

93].

Once the query was changed with the word “destination” instead of “cities” or “city” another 10 articles were found in Scopus plus 12 in the Web of Science, after combining both databases, we eliminated 8 duplicates plus 1 that was found during the previous step. The final combination of both queries led to 10 documents and the identified techniques are distributed in

Table 5.

As it can be seen in

Table 5, there are different neuromarketing techniques that have been applied in the city branding processes. Most of the articles are focused on the electroencephalography technique (36%), followed by the eye-tracker (ET) (29%) and only one case (representing 7%) implemented functional magnetic resonance imaging. Other cases (29%) reported other methods or a combination of different techniques. Savelli et al., [

95] combined implicit priming, eye-tracking and EEG.

De Frutos & López [

96] presented a literature review of the emotions in tourism advertising with the techniques electroencephalography (EEG), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), eye-tracking and skin conductance; and finally, Ponce [

99], addresses an empirical-analytical model of the use of chromatic codes in destination books and magazines.

Within this research line, Bastiaansen et al., [

93] utilize brain event-related potentials (ERP) are used as tool to evaluate the effectiveness of place marketing in Bruges and Kyoto when the subjects are exposed to pictures and movies from these destinations. In the results, the authors demonstrated an increase in emotional reactions to the pictures shown and conclude that EEG can be conducted for experimental neuromarketing to study the effectiveness of destination marketing.

On the other hand, Li et al., [

94] use inside neural mechanism (brain activity) through EEG to measure individuals’ arousal induced by destination advertising. The authors first identified the ERP component when the residual excitation is induced by prior advertisement, finally, their study explores the spillover effects on behavioral intention.

Furthermore, Lazo et al., [

98] consider the theoretical approaches of the use of neuromarketing for the digital promotion of Cuba. The authors conclude that using eye-tracking to identify reactions to different stimuli, the researchers can evaluate the design of the ads by recording the number of elements that are attractive for the users of websites.

In addition, Savelli et al., [

95] analyzed how communicating typical-local food serves as motivation to attract travelers. For their research, they implemented a combination of neuroscience techniques like implicit priming test, eye-tracking and electroencephalography. In the results, they found that tourists perceive healthiness as typical-local foods as the most relevant variable to engage travelers, followed by geographical indications.

Next, De Frutos & López [

96] analyze the influence of emotions in tourism advertisement, the impact of tourists´ attitudes, decisions and preferences through the application of neuromarketing. In their results, the authors found that the ET is the most used tool that has been successfully proved to measure the attention in tourist advertisement measuring the tourists’ stimuli in real time.

Ponce, [

99], studies the theory of the neuromarketing incidence on destination books and magazines through the use of images and chromatic codes. Her study also includes the importance of semiotics for the translation of touristic materials as cultural dimensions, context, needs and preferences of the consumers require deep knowledge of the origin. Concluding that neuromarketing affects the sensorial meaning through the visual elements of the brand.

Finally, Michael, et al.,[

97] present the first study of “Islamic Marketing” using neuromarketing to research Muslim customers’ unconscious emotional responses. They argue that most of the studies found in the literature use self-report questionnaires that are subject to a variety form of bias. This is why they explore unconscious emotional responses that can provide unbiased portrays of subjects when exposed to stimuli. Their study is focused on the “third” source of image formation that is the “demand side” (local citizens) of the United Arab Emirates with 30 participants, ET was the tool implemented plus a brain scanning equipment.

With the collected data, the authors analyzed Emotional Responses, considering New York city with the strongest emotional response.

Having established a foundational understanding of both place branding perceptions and neuromarketing techniques, we will now examine the existing applications of these techniques within the cases of place branding.

3.2.1. Eye-tracker:

Lazo et al., [

98] mention how the combination of marketing and neuroscience makes possible to analyze the reactions to purchasing stimuli and how it outlines the behavior from a cognitive point of view. The authors mention the potential of psychology in marketing to explore emotions, confidence and security on tourists and how neuromarketing should be incorporated on business strategies. Continuing, the authors highlight the capabilities of using ET and mouse tracking to record not only the frequency of blinking and the dilatation of the pupils, but the movements and duration and links users access when visiting a tourist website, comprising groups of data that can be used to structure the content and enhance the visitors’ experience.

Following the concerns of Savelli et al., [

95] about the lack of clarity in previous studies where tourists’ attitudes, preferences and behaviors have been analyzed, the authors explore a combination of neuroscientific approaches where biometric and neurometric data is collected through eye-tracking and electroencephalogram techniques.

For the eye-tracking technique, they analyzed gazing behavior (eye movement and eye fixation, which includes the average time of the first fixation as a single area of interest) projecting a group of images for 10 seconds with intervals of a neutral background for 5 seconds, then another projection of images simultaneously for 30 seconds to allow the subjects to make comparisons. In their results, it is shown the attractiveness of particular areas in the images exposed to the subjects. They concluded that it was possible to rank visual and cognitive attractiveness on communicational signs and uncovering specific sub-signals where strategies should be focusing on. The use of neuroscience techniques has provided new insights into measuring emotions, attitudes and associations experienced by the individuals.

Likewise, De Frutos & López, [

96] found that emotions play a relevant role in tourism and how neuroscience provides a relevant opportunity for marketing research.

3.2.2. EEG:

Neuromarketing techniques have already been tested in urban and destination branding contexts. A notable example is the use of EEG to evaluate emotional responses to promotional city videos. Bastiaansen et al. [

93] conducted a neuromarketing experiment where participants’ brain activity was monitored via EEG while watching destination marketing videos. They found that viewing these videos could indeed induce stronger positive emotions toward the destination – evidenced by significant changes in event-related potentials, suggesting the videos effectively stimulated emotional processing in the brain.

Such results illustrate how EEG can verify whether a city’s advertising media is truly engaging viewers at a deep emotional level.

While particular studies used ET (focusing on where people look), researchers could complement it with EEG or facial expression analysis to also capture the emotional arousal when viewing beautiful city scenes. Together, these case studies demonstrate the empirical application of neuromarketing in urban branding: researchers can quantitatively measure how engaging a city’s marketing materials are at a neurological level.

3.2.3. fMRI:

fMRI measures changes in blood flow in the brain, revealing which brain regions become active in response to city-related stimuli (e.g. seeing a skyline or city logo). fMRI has shown that strong brands (like beloved consumer products) can activate the brain’s reward centers and even areas tied to self-identity. De Frutos & López [

96] have been the only authors to address to this technique applied to city branding. We found (and we will extend on this on the ethical considerations) that the use of this specific technique could be expensive, and results might defer from reality as all the possible scenarios should be simulated with images, videos or virtual reality, plus the availability of experts (neuropsychologist or radiologist experts on brain images) to interpret the results.

4. Discussion

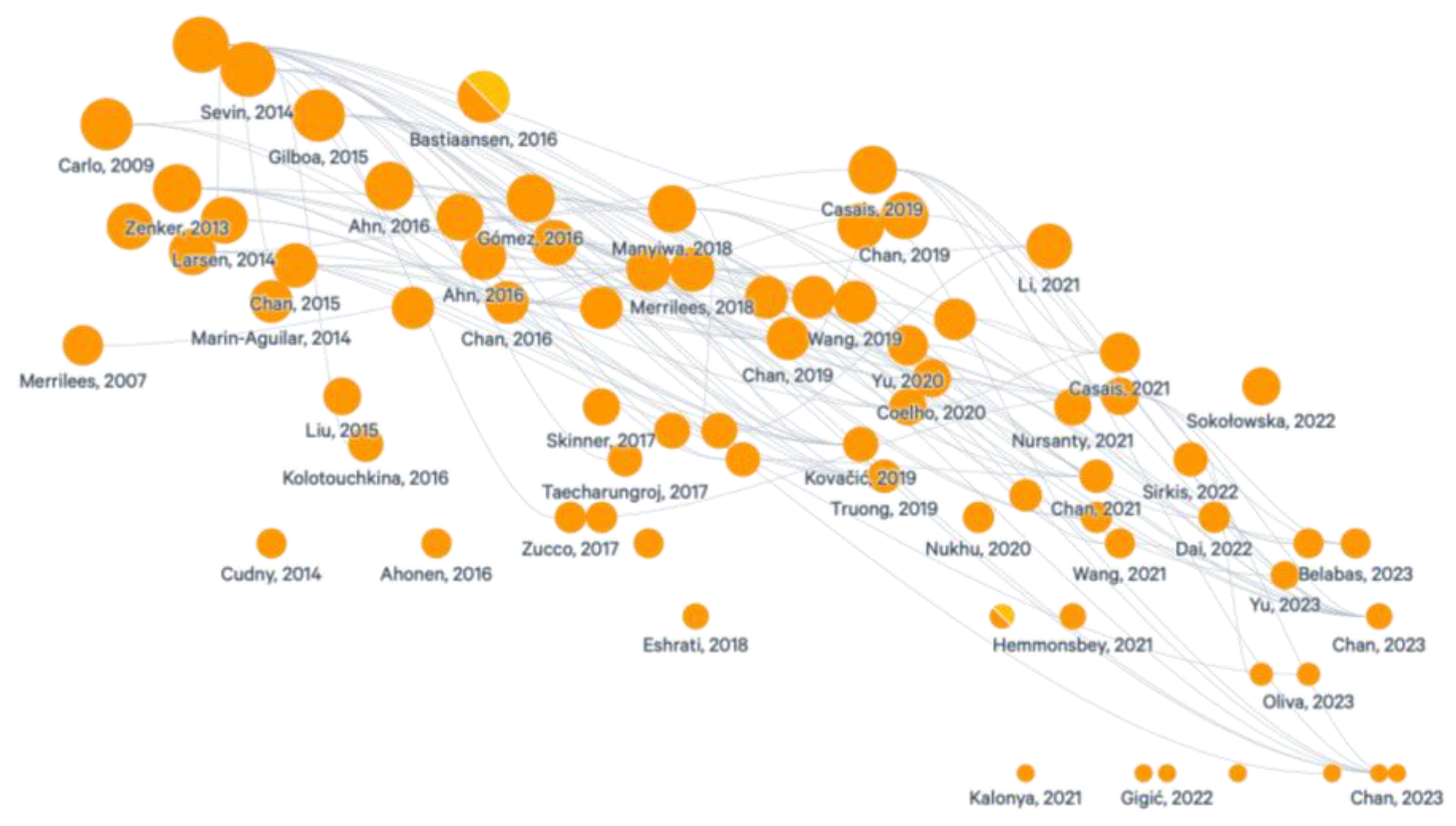

The intersection of neuromarketing and city branding is an emerging area of interest,

Figure 3 shows the co-citation of authors and the first articles that combined neuromarketing techniques with place branding.

As cities today compete globally to attract resources and attention from different sources (Tourist, Investors, International Cooperators, Talents, Importers)

[11] effective branding can offer a competitive advantage. Traditional city branding efforts like logos, slogans and promotional campaigns, rely on understanding conscious preferences and self-reported attitudes of target audiences.

Findings show a gap between what people say about a place and their deeper subconscious feelings or actual behavior towards the brand or the place itself. This is where neuromarketing can add value, by applying different techniques, city marketing can uncover the hidden emotional and cognitive responses that a city’s image or marketing campaign evokes.

After considering the different cases, we performed an analysis of the geographical distribution of the studies. We found 31 different countries where perceptions have been measured on place branding, data reveals a concentration of research on place brand perception across various regions globally. Notably, the Asia Pacific region exhibits the highest number of studies, with a significant focus on countries like China and Hong Kong (including Taiwan) a total of 20 o those cases. Indicating a strong interest in understanding and measuring place perceptions in this rapidly developing and urbanized part of the world. Western Europe also shows a substantial number of studies, covering a diverse range of countries and city types, suggesting a mature research landscape in this area, with 19 cases.

In contrast, other regions such as Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East have a comparatively lower number of studies on this topic within the reviewed literature. While North America and South Asia also show some representation, the overall distribution suggests a potential research gap in understanding place brand perceptions in these regions. Furthermore, the presence of multi-country studies, particularly within Europe and Latin America, highlights the interest in comparative analyses across different urban contexts. This geographical analysis underscores the need for further research to explore the nuances of place brand perception in under-represented regions and to facilitate a more globally comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon.

In terms of the neuromarketing techniques, we found different cases where different methods were used to capture objective neurological and physiological reactions (brain activity, skin conductance, eye movement or fixations) providing insights into what truly people feel about a city’s brand, beyond biases or social desirability in surveys.

Key techniques include neuroimaging methods like fMRI and EEG as well as other physiological measures like eye-tracking, galvanic skin response (GSR), and heart rate monitoring. Each modality offers a window into a different aspect of the consumer’s (or visitor’s) neurophysiological response.

5. Conclusions

The use of neuromarketing techniques is a novel solution for destinations that wish to have a deeper understanding of the consumer’s emotions and reactions when exposed to the destination and its advertisement. Tourism boards might use EEG, or GSR on a sample of viewers to compare two city promotional videos, choosing the one that elicits stronger positive spikes in attention and emotion. Such data-driven optimization can potentially make city branding efforts more effective by aligning them with the innate preferences and emotional triggers of the target audience.

Another interesting angle is using neuroimaging to study city brand perceptions in the brain: although still nascent, city marketers could use fMRI to see how the brain responds to a city’s name or symbols. Results show that people who strongly identify with a city (their hometown or a favorite destination) would show heightened activation in emotional and memory regions when exposed to cues of that city (like images of landmarks or city slogans). Preliminary neuroscience of place studies has indeed found that urban environments modulate brain activity: e.g. urban scenes versus natural scenes produce different connectivity patterns in attention networks.

Knowing this, city marketers can tailor their branding content – emphasizing elements that neurologically promote positive engagement (such as greenery, human-friendly spaces) and minimizing those that provoke anxiety. In sum, neuromarketing techniques provide a cutting-edge set of tools for city marketing: from measuring attention (eye-tracking where people focus in an ad) to capturing emotion (EEG/GSR responses to city imagery) and decoding preference (brain patterns linked to liking a city). These methods elevate city branding research from purely subjective opinions to a richer understanding of the subconscious impressions a city creates in the mind.

In conclusion, the application of neuromarketing and neuropsychology to city marketing and branding offers a powerful complementary approach to traditional place marketing. This review highlighted that by tapping into neuroscience, city marketers can gain deeper insights into how people emotionally and cognitively engage with urban places – from the brainwave patterns evoked by city advertisements to the emotional bonds reflected in place attachment.

Theoretical frameworks from consumer neuroscience and environmental psychology converge to suggest that successful city brands work on an implicit level, creating positive associations in memory and affect, much like successful product brands do.

Future research directions may include conducting more in-situ neuromarketing studies, for example using mobile EEG or biometric sensors as people navigate real city environments to capture authentic responses to urban design and marketing installations. The integration of advanced technologies like virtual reality (to simulate city experiences) and artificial intelligence (to analyze complex neurophysiological datasets) holds promise for richer insights. Machine learning, for example, could identify patterns in brain data that correspond with certain favorable perceptions of a city, aiding predictive models of city image. Researchers are also looking into combining multiple neuromarketing tools simultaneously (“multimodal” approaches) to get a holistic view of attention, emotion, and cognition during city brand exposure.

5.1. Challenges and Ethical Considerations

While the potential of neuromarketing and neuropsychology in city and place branding is exciting, there are significant challenges and ethical issues to consider: Methodological limitations of neuromarketing in city research include practicality, cost, and interpretability. Techniques like fMRI are expensive and require laboratory settings, making it difficult to study authentic reactions to a city (one cannot easily put a person in an MRI scanner and simulate the full experience of walking through Times Square, for example). EEG and biometric measures are more portable, but even then, capturing data in real urban environments can be confounded by numerous uncontrolled variables (noise, weather, movement artifacts in data, etc.). Sample sizes in such studies are often small due to the complexity of experiments, raising questions about generalizability of findings. There is also the issue of expertise – analyzing brain data is complex, and city marketers may misinterpret results without proper neuroscientific guidance.

Another challenge is ensuring ecological validity, that the stimuli used in neuromarketing experiments realistically represent the city experience. Watching a promotional video in a lab with an EEG cap on is not the same as visiting the city. Thus, researchers must be careful about drawing conclusions. Additionally, integrating findings from different tools can be difficult: brain data, eye-tracking heatmaps, and self-report might sometimes conflict (one might show excitement while another shows aversion), requiring careful interpretation.

As a limitation, neuromarketing typically captures immediate reactions; city branding, however, often aims to build a long-term relationship. Longitudinal effects (how repeated exposures to a city’s brand over months or years affect the brain) are not yet well-understood and present a frontier for future research.

From an ethical standpoint, the use of neuromarketing in any domain raises important concerns about manipulation and privacy, which are very pertinent in city branding because the consumers of city brands are often citizens and society at large.

One concern is the potential for invasive profiling, this is, the idea that city marketers could “read the minds” of their audience to tailor campaigns. If brain data or other biometric information is collected from visitors (even in research), there must be strict consent and data protection, since this delves into individuals’ subconscious preferences. People have a right to privacy of their thoughts; using neuro-tools without transparency could violate that.

There is also a risk of exploitation and discrimination. If neuro-research found, hypothetically, that certain groups of people’s brains respond more favorably to a certain city message, a city might overly target those groups and neglect others, or worse, try to exploit neurological vulnerabilities (as has been discussed in product marketing ethics). For example, if a subset of individuals has a strong subconscious preference for gambling, a city known for casinos might aggressively brand toward them, this crosses into questionable territory of exploiting predispositions.

Lack of regulatory oversight is a concern raised in the literature [101], as marketing practices are not typically subject to the same ethical review as medical experiments, thus, a neuromarketing study conducted by a city’s marketing department might bypass institutional ethics review, even though it deals with human subjects and sensitive data.

Finally, there is the matter of public perception and trust. If the public learns that a city is using brain-scanning to craft its image, reactions could vary from fascination to fear. Transparency is key – people generally do not object to being emotionally persuaded (that’s what good branding does), but they might react negatively if they feel their subconscious is being “weaponized” without consent. A city’s reputation could suffer if its branding is seen as manipulative or deceptive. Therefore, ethical city branding with neuromarketing should emphasize using these insights to enhance genuine well-being and satisfaction, not to trick or coerce. For example, using neuroscience to design more pleasant parks or more intuitive wayfinding in a city (thus legitimately improving experiences) would be viewed differently than using it to simply increase tourism at any psychological cost.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Balzan, A.; methodology, Balzan, A.; Castaneda-Quirama, T., and Casadiego-Alzate, R.; software, Balzan, A.; validation, Castaneda-Quirama, T., and Casadiego-Alzate, R.; formal analysis, Balzan, A.; Castaneda-Quirama, T.; investigation, Balzan, A.; Castaneda-Quirama, T., and Casadiego-Alzate, R.; resources, Balzan, A.; Castaneda-Quirama, T., and Casadiego-Alzate, R.; data curation, Casadiego-Alzate, R.; writing—original draft preparation, Balzan, A.; writing—review and editing, Castaneda-Quirama, T., and Casadiego-Alzate, R.; visualization, Balzan, A.; supervision, Balzan, A.; project administration, Balzan, A.; funding acquisition, Balzan, A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by INSTITUCIÓN UNIVERSITARIAPOLITÉCNICO GRANCOLOMBIANO, grant number CIDES2024_ENDI_MI2_PEC_07-87411.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institución Universitaria Politécnico Grancolombiano (protocol accepted on project CIDES2024_ENDI_MI2_PEC_07-87411).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data collected for the creation of this article is open sourced at OSF repository and may be accessed using the following link: DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/7FCD3.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Institución Universitaria Politécnico Grancolombiano for the funding for the development of this research, specially to the Direction of the School of Business and International Direction and the Direction of Research.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| fMRI |

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| GSR |

Galvanic Skin Response |

| ET |

Eye-Tracker |

References

- Gilboa, S.; Jaffe, E.D.; Vianelli, D.; Pastore, A.; Herstein, R. A Summated Rating Scale for Measuring City Image. CITIES 2015, 44, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, A. City Branding Como Estrategia de Mercadeo Para La Internacionalización de Las Ciudades. Punto de vista 2022, 13, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. The Global City: Introducing a Concept. The Brown Journal of World Affairs 2005, 11, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğan, M.; Bilisik, Öğr.Ü.Ö.N.; Kaya, İ. A New Fuzzy Decision-Making Procedure to Prioritization of the Brand City Candidates for Turkey. Journal of Multiple-Valued Logic & Soft Computing 2018, 30, 1–28.

- Petrikova, D.; Jaššo, M.; Hajduk, M. Social Media as Tool of SMART City Marketing. In; 2020; pp. 55–72.

- Kalandides, A.; Kavaratzis, M.; Boisen, M. Special Edition of the Place Branding Conference: “Roots-Politics-Methods Journal of Place Management and Development 2012, 5. [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Hatch, M.J. The Dynamics of Place Brands: An Identity-Based Approach to Place Theory. MARKETING THEORY 2013, 13, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuring, J.H.G.; Haartsen, T. Destination Branding by Residents: The Role of Perceived Responsibility in Positive and Negative Word-of-Mouth. Tourism Planning & Development 2017, 14, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de San Eugenio-Vela, J.; Ginesta, X.; Kavaratzis, M. The Critical Role of Stakeholder Engagement in a Place Branding: A Case Study of the Emporda Brand. EUROPEAN PLANNING STUDIES 2020, 28, 1393–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cui, X.; Guo, Y. Residents’ Engagement Behavior in Destination Branding. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, A.; Correa-Jaramillo, J.; Jiménez-Zarco, A.I. Participation of Stakeholders in the Internationalization of the City of Medellin. Journal of Qualitative Research in Tourism 2024, 5, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, E.; Kavaratzis, M.; Zenker, S. My City – My Brand: The Different Roles of Residents in Place Branding. Journal of Place Management and Development 2013, 6, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebanić, K.R.; Vukomanović, M. Realizing the Need for Digital Transformation of Stakeholder Management: A Systematic Review in the Construction Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liao, H. A Bibliometric Analysis of Fuzzy Decision Research During 1970–2015. International Journal of Fuzzy Systems 2017, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadiego-Alzate, R.; Sanguino-García, V.; Velásquez Calle, P.A.; Díaz Mesa, V.; Palacio Miranda, D.A. Análisis Bibliométrico y Visualización de Estudios Relacionados Con La Segmentación de Los Consumidores En Los Mercados Campesinos. Emergentes - Revista Científica 2024, 4, 158–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaloul, W.S.; Alzubi, K.M.; Malkawi, A.B.; Al Salaheen, M.; Musarat, M.A. Productivity Monitoring in Building Construction Projects: A Systematic Review. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2022, 29, 2760–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, F.; Lazzeretti, L. FASHION INDUSTRY AND CITY BRANDING AN ANALYSIS OF VISITORS PERCEPTION OF FLORENCE. Global Fashion Management Conference 2015, 3, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casais, B.; Monteiro, P. Residents’ Involvement in City Brand Co-Creation and Their perceptions of City Brand Identity: A Case Study in Porto. PLACE BRANDING AND PUBLIC DIPLOMACY 2019, 15, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, K.W.K.; Law, W.W.Y. City Re-Imagined: Multi-Stakeholder Study on Branding Hong Kong as a City of Greenery. J Environ Manage 2018, 206, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmonsbey, J.; Tichaawa, T.M. Stakeholder and Visitor Reflections of Sport Brand Positioning in South Africa. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites 2021, 34, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Foster, C.; Alevizou, P.J.; Frohlich, C. Stakeholder Engagement in the City Branding Process. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2016, 12, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukhu, R.; Singh, S. Branding Dilemma: The Case of Branding Hyderabad City. International Journal of Tourism Cities 2020, 6, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- kalonya, dalya hazar Evaluation of the Perception of Change in Tourism and Agriculture After the Slow City Branding: The Case of Seferihisar. MEGARON / Yıldız Technical University, Faculty of Architecture E-Journal 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sevin, H.E. Understanding Cities through City Brands: City Branding as a Social and Semantic Network. Cities 2014, 38, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.-A.T. Applying the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique on Understanding Place Image. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies 2019, 27, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolowska, E.; Pawlak, K.; Hajduk, G.; Dziadkiewicz, A. City Brand Equity, a Marketing Perspective. CITIES 2022, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uskokovic, L. CREATING A CITY BRAND AS A TOURIST DESTINATION IN THE SELECTED COUNTRIES OF ADRIATIC REGION. TRANSFORMATIONS IN BUSINESS & ECONOMICS 2020, 19, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Zenker, S.; Beckmann, S.C. Measuring Brand Image Effects of Flagship Projects for Place Brands: The Case of Hamburg. Journal of Brand Management 2013, 20, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.I.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.X.; Loo, Y.-M. Ningbo City Branding and Public Diplomacy under the Belt and Road Initiative in China. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2021, 17, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.; Hyun, S.S.; Kim, I. City Residents’ Perception of MICE City Brand Orientation and Their Citizenship Behavior: A Case Study of Busan, South Korea. Asia pacific journal of tourism research 2016, 21, 328–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-J.; Kim, I.; Lee, T.J. Exploring Visitor Brand Citizenship Behavior: The Case of the ‘MICE City Busan’, South Korea. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2016, 5, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabas, W. Glamour or Sham? Residents’ Perceptions of City Branding in a Superdiverse City: The Case of Rotterdam. Cities 2023, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campelo, A.; Aitken, R.; Thyne, M.; Gnoth, J. Sense of Place: The Importance for Destination Branding. J Travel Res 2014, 53, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-S. Which City Theme Has the Strongest Local Brand Equity for Hong Kong: Green, Creative or Smart City? Place Branding And Public Diplomacy 2019, 15, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-S. From the Perspective of Local Brand Equity, How Do Citizens Perceive, Creative and Smart Brand Potential of Future Hong Kong? Place Branding And Public Diplomacy 2023, 19, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.S.; Peters, M.; Marafa, L.M. Public Parks in City Branding: Perceptions of Visitors Vis-a-Vis in Hong Kong. Urban For Urban Green 2015, 14, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.S.; Tsun, W.Y. Unleashing the Potential of Local Brand Equity of Hong Kong as A-Creative-Smart City. Journal Of Place Management And Development 2024, 17, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. The Influence of The „KOMISARZ Alex“ TV Series on The Development of Łódź (Poland) in The Eyes of City Inhabitants. Moravian Geographical Reports 2014, 22, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escourido-Calvo, M.; Prado-Dominguez, A.J.; Alejandro-Martinez, V.; Martin-Bermudez, F. Repositioning the City Brand in the Face of the Energy and Ecological Paradigm. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigic, B.K. population perception of creating the brand of the city of osijek with an emphasis in the field of culture. Casopis Za Ekonomiju I Trzisne Komunikacije 2022, 12, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, S.; Jaffe, E. Can One Brand Fit All? Segmenting City Residents for Place Branding. Cities 2021, 116, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Mosoni, G.; Wang, M.; Zheng, X.; Sun, Y. The Image of the 2010 World Expo: Residents’ Perspective. Engineering Economics 2017, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolotouchkina, O.; Seisdedos, G. The Urban Cultural Appeal Matrix: Identifying Key Elements of the Cultural City Brand Profile Using the Example of Madrid. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2016, 12, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, H.G. The Emerging Shanghai City Brand: A Netnographic Study of Image among Foreigners. Journal Of Destination Marketing & Management 2014, 3, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, H.G. The `mental Topography’ of the Shanghai City Brand: A Netnographic to Formulating City Brand Positioning Strategies. Journal Of Destination Marketing & Management 2018, 8, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Schein, D.D.; Ravi, S.P.; Song, W.; Gu, Y. Factors influencing residents’ perceptions, attitudes and behavioral intention toward festivals and special events: a pre-event perspective. Journal of Business Economics and Management 2018, 19, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Aguilar, J.T.; Vila-Lopez, N. How Can Mega Events and Ecological Orientation Improve City Brand? International Journal Of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2014, 26, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrilees, B.; Miller, D.; Ge, G.L.; Tam, C.C.C. Asian City Brand Meaning: A Hong Kong Perspective. Journal of Brand Management 2018, 25, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrilees, B.; Miller, D.; Herington, C.; Smith, C. Brand Cairns: An Insider (Resident) Stakeholder Perspective. Tourism Analysis 2007, 12, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milagros, A.-P.C.; Arelis, M.-Q.L.; Elizabeth, V.L.L.; Paul, T.-R.A. Sullana City Brand: Opportunity and Challenges in Piura, Peru; [Marca Ciudad Sullana: Oportunidad y Retos En Piura, Perú]. Rev Cienc Soc 2022, 28, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursanty, E.; Cauba, A.G.; Waskito, A.P. Vernacular Branding: Sustaining City Identity through Vernacular Architecture of Indigenous Villages. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E.C.; De la Cruz, E.R.R.; Vázquez, F.J.C. Sustainable Tourism and Residents’ Perception towards the Brand: The Case of Malaga (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taecharungroj, V. City-District Divergence Grid: A Multi-Level City Brand Positioning Tool. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2018, 14, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toros, E.; Gazibey, Y. Priorities of the Citizens in City Brand Development: Comparison of Two Cities (Nicosia and Kyrenia) by Using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Approach. Qual Quant 2018, 52, 413–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gu, S.; Lin, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zheng, Y. Urban Renewal and Brand Equity: Guangzhou, China Residents’ Perceptions of Microtransformation. J Urban Plan Dev 2021, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Lee, D.; Ahn, J.; Lee, M.; Foreman, J.J. City Branding’s Impact on Cities Hosting Sporting Events: Top-down and Bottom-up Effects in a Pre-Post Study. Tour Manag Perspect 2023, 46, 101098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.; Kim, J. The Relationship between Self-City Brand Connection, City Brand Experience, and City Brand Ambassadors. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Beckmann, S.C. My Place Is Not Your Place – Different Place Brand Knowledge by Different Target Groups. Journal of Place Management and Development 2013, 6, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucco, F.D.; Reis, C.; Anjos, S.J.G. dos; Effting, S.J.; Pereira, M. de L. Attributes of the Blumenau (Brazil) Brand from the Residents’ Perspective, and Its Influence on the Decision to Stay in the Destination. International Journal of Tourism Cities 2017, 3, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, M.; Canali, S.; Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N. Moving Milan towards Expo 2015: Designing Culture into a City Brand. Journal of Place Management and Development 2009, 2, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.S.; Peters, M.; Pikkemaat, B. Investigating Visitors’ Perception of Smart City Dimensions for City in Hong Kong. International Journal Of Tourism Cities 2019, 5, 620–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Suryadipura, D.; Kostini, N.; Miftahuddin, A. An Integrative Model of Cognitive Image and City Brand Equity. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites 2021, 35, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Zheng, X. Understanding How Multi-Sensory Spatial Experience Influences, Affective City Image and Behavioural Intention. Environ Impact Assess Rev 2021, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Fernández, A.C.; Molina, A.; Aranda, E. City Branding in European Capitals: An Analysis from the Visitor Perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2018, 7, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahar, D.; Vincent, V.Z.; Philip, A.V. Art-Event Image in City Brand Equity: Mediating Role of City Brand Attachment. International Journal of Tourism Cities 2020, 6, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, S.; Milenkovic, N.; Slivar, I.; Rancic, M. Shaping City Brand Strategies Based on the Tourists’ Brand Perception: Report on Banja Luka Main Target Groups. International Journal Of Tourism Cities 2020, 6, 371–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, A.; Dewantara, R.Y.; Azizah, D.F.; Supriono, S. Determining Outcome Factors of City Branding Post-COVID-19: Roles of Brand Satisfaction, Brand Experience and Perceived Risk. Journal of Tourism Futures 2024, 10, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lien, C.-H.; Wang, S.W.; Wang, T.; Dong, W. Event and City Image: The Effect on Revisit Intention. Tourism Review 2021, 76, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A.N.; Rodrigues, R.I.; Palrão, T.; Santos, V.R. The Influence of Web Summit Attendees’ Age and Length of Stay on Leisure Activity Preferences and City Image. International Journal of Event and Festival Management 2023, 14, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Fernández, A.C.; Gómez, M.; Aranda, E. Differences in the City Branding of European Capitals Based on Online vs. Offline Sources of Information. Tour Manag 2017, 58, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawir; Koerniawan, M.D.; Dewancker, B.J. Visitor Perceptions and Effectiveness of Place Branding Strategies in Thematic Parks in Bandung City Using Text Mining Based on Google Maps User Reviews. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2123. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Lee, T.J. Influence of the ‘Slow City’ Brand Association on the Behavioural Intention of Potential Tourists. Current Issues in Tourism 2019, 22, 1405–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Brand Image Assessment: International Visitors’ Perceptions of Cape Town. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 2010, 28, 462–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado-Pezúa, O.; Sirkis, G.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W. Urban Tourism Perception and Recommendation in Mexico City and Lima. Land (Basel) 2022, 11, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigwele, L.; Prinsloo, J.J.; Pelser, T.G. Strategies for Branding the City of Gaborone as a Tourist Destination. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 2018, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Sirkis, G.; Regalado-Pezúa, O.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W. The Determining Factors of Attractiveness in Urban Tourism: A Study in Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Bogota, and Lima. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H. Business Tourists’ Perceptions of Nation Brands and Capital City Brands: A Comparison between Dublin/Republic of Ireland, and Cardiff/Wales. Journal Of Marketing Management 2017, 33, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casais, B.; Poço, T. Emotional Branding of a City for Inciting Resident and Visitor Place Attachment. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2023, 19, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-S.; Marafa, L.M. The Green Branding of Hong Kong: Visitors’ and Residents’ Perceptions. Journal of Place Management and Development 2016, 9, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Bairrada, C.; Simão, L.; Barbosa, C. The Drivers of the City Brand Equity Comparing Citizens’ and Tourists’ Perceptions and Its Influence on the City Attractiveness: The Case of the City of Coimbra. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration 2022, 23, 242–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahatkar, H.; Aminzadeh, B. The Sense of Place and Its Influence on Place Branding: A Case Study of Sanandaj Natural Landscape in Iran. Landsc Res 2020, 45, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-D. Major Event and City Branding. Journal of Place Management and Development 2015, 8, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyiwa, S.; Priporas, C.V.; Wang, X.L. Influence of Perceived City Brand Image on Emotional Attachment to the City. Journal of Place Management and Development 2018, 11, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochkovskaya, M.; Gerasimenko, V. Buildings from the Socialist Past as Part of a City’s Brand Identity: The Case of Warsaw. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series 2018, 39, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompe, A. Designing the Image and the Perception of the City and Its’ Brand: The Importance and Impact of Qualitative Urbanistic Elements. Advances in Business Related Scientific Research Journal 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-J. Green City Branding: Perceptions of Multiple Stakeholders. Journal Of Product And Brand Management 2019, 28, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, C.; De Mortanges, C.P. City Branding: A Brand Concept Map Analysis of a University Town. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2011, 7, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernicova-Buca, M.; Pevnaya V, M.; Fedorova, M.; Bystrova, T. Students’ Awareness of the Local Cultural and Historical Heritage in Post-Communist Regional Centers: Yekaterinburg, Gyumri, Timisoara. Land (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshrati, D. Type versus stereotype: an analysis of international college students’ perceptions of us cities and public spaces. International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR 2018, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque Oliva, E.J.; Sánchez-Torres, J.A. Building a University City Brand: Colombian University Students’ Perceptions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, V.; Dimoka, A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Vo, K.; Hampton, W.; Bollinger, B.; Hershfield, H.E.; Ishihara, M.; Winer, R.S. Predicting Advertising Success beyond Traditional Measures: New Insights from Neurophysiological Methods and Market Response Modeling. Journal of Marketing Research 2015, 52, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaansen, M.; Straatman, S.; Driessen, E.; Mitas, O.; Stekelenburg, J.; Wang, L. My Destination in Your Brain: A Novel Neuromarketing Approach for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Destination Marketing. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 2018, 7, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lyu, T.; Park, S.; Choi, Y. Spillover Effects in Destination Advertising: An Electroencephalography Study. Ann Tour Res 2023, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelli, E.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Murmura, F.; Pencarelli, T. How to Communicate Typical–Local Foods to Improve Food Tourism Attractiveness. Psychol Mark 2022, 39, 1350–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Frutos-Arranz, S.; López, M.-F.B. the state of the art of emotional advertising in tourism: a neuromarketing perspective. Tourism Review International 2022, 26, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, I.; Ramsoy, T.; Stephens, M.; Kotsi, F. A Study of Unconscious Emotional and Cognitive Responses to Tourism Images Using a Neuroscience Method. Journal of Islamic Marketing 2019, 10, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazo, S.R.M.; Alfonso, Y.V.; del Vallin, S.L. NEUROMARKETING ACTIONS FOR THE DIGITAL PROMOTION OF TOURISM IN CUBA. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites 2023, 46, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policastro Ponce, G. Visual Semiotics as a Neuromarketing Strategy in Tourist Information and promotion Digital Texts, and Its Importance for Translation Activity(Spanish, French and Italian). ONOMAZEIN 2020, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).