Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

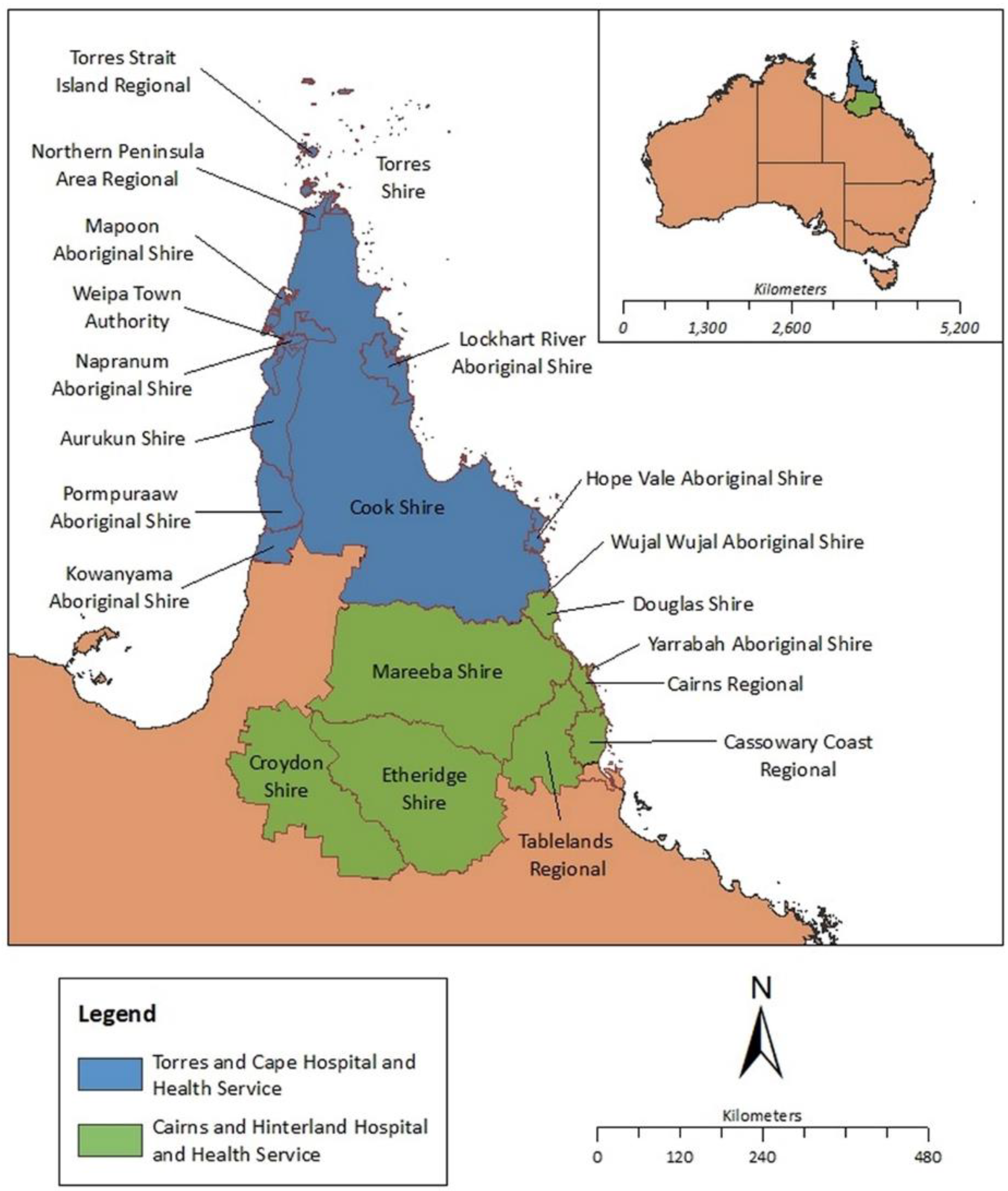

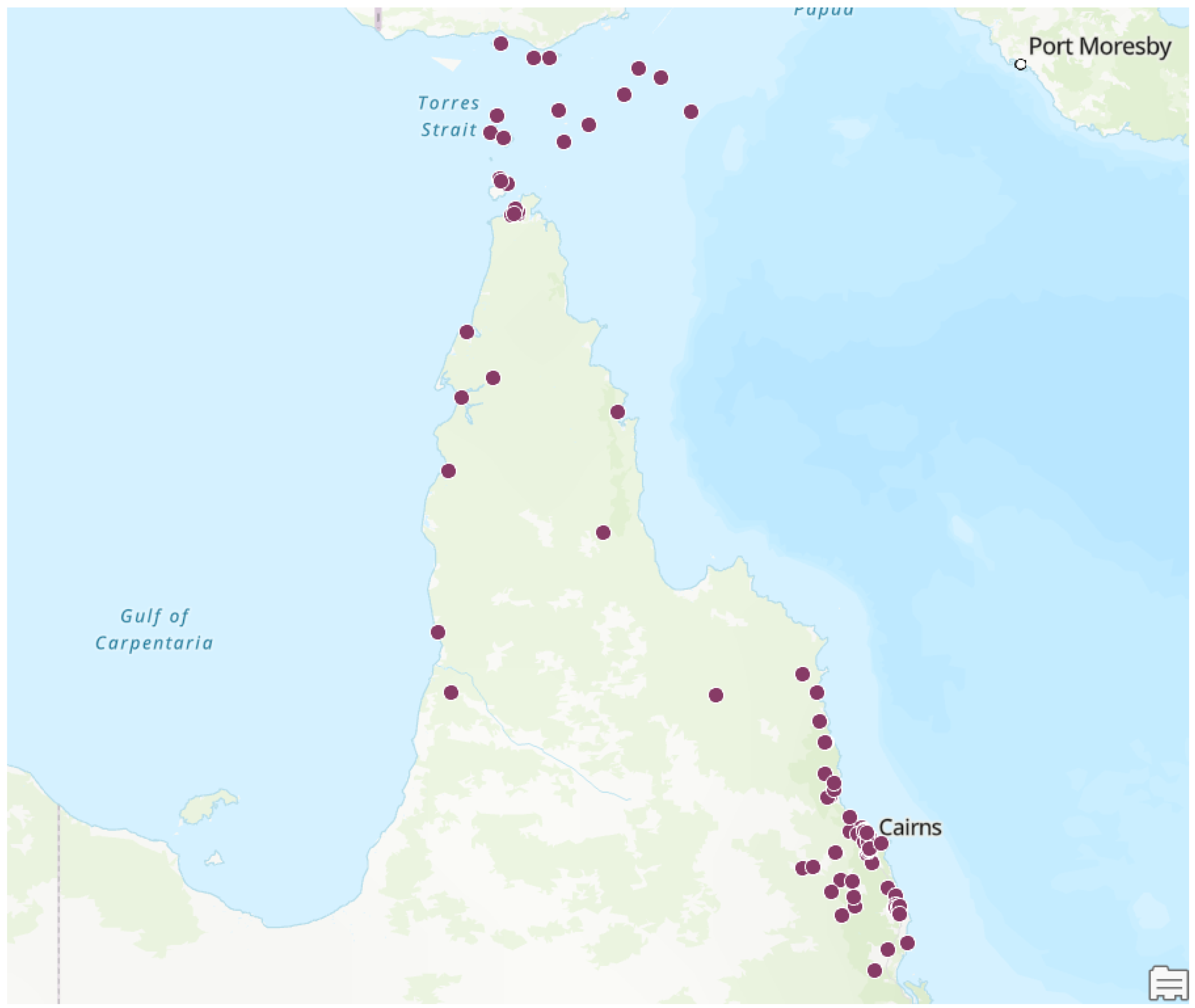

Setting

Data Collection

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Approval

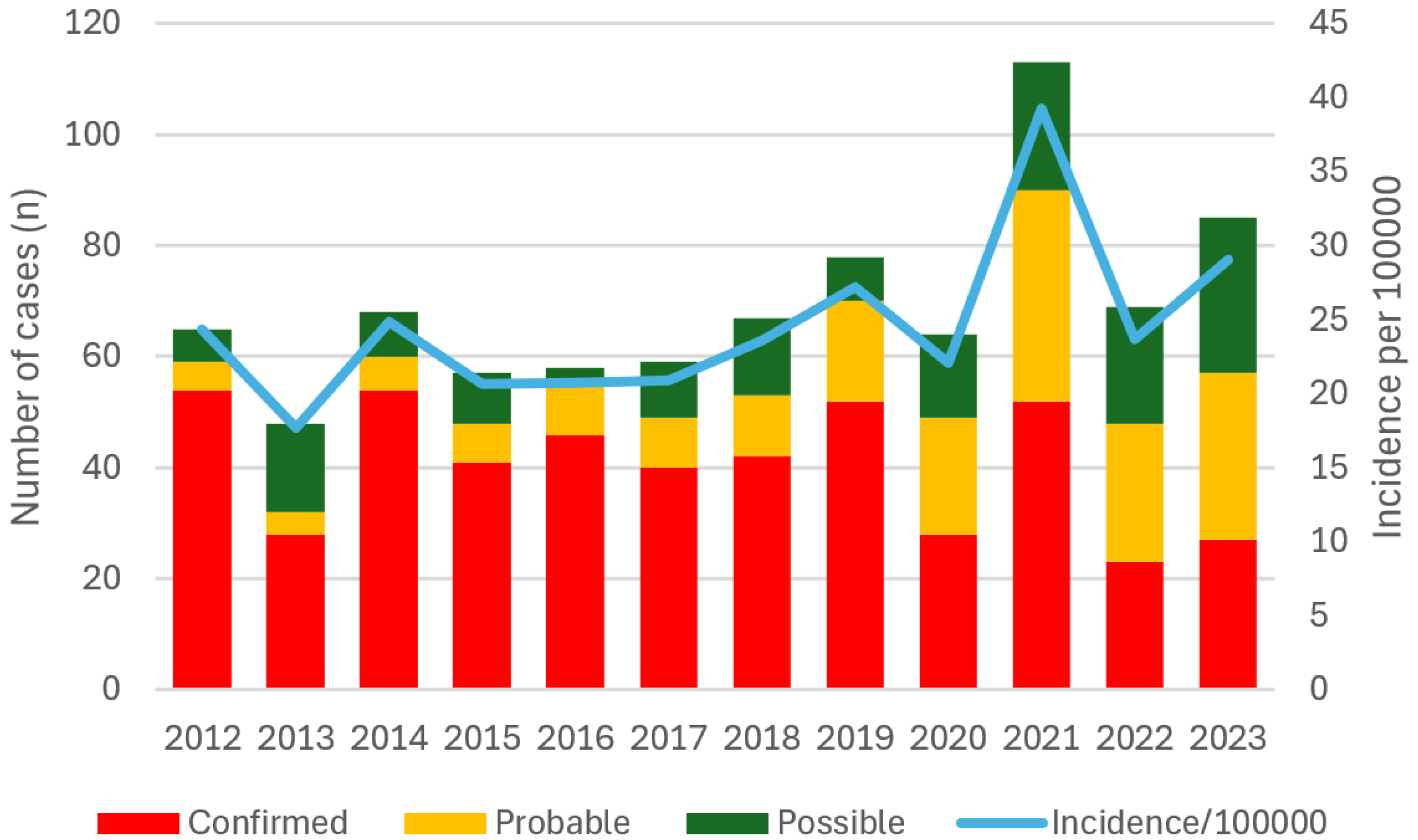

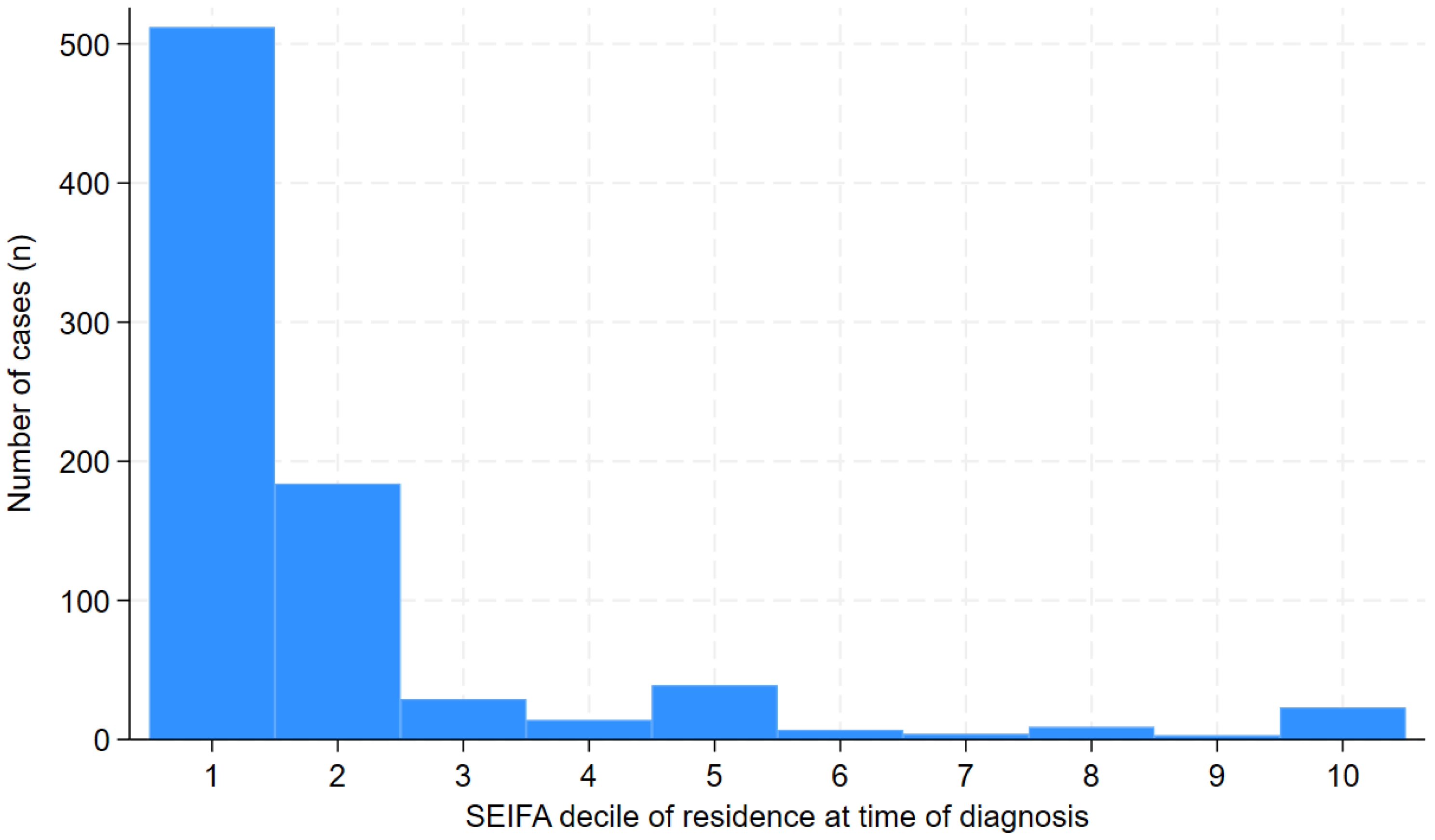

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Auala T, Zavale BLG, Mbakwem AÇ, Mocumbi AO. Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease: Highlighting the Role of Group A Streptococcus in the Global Burden of Cardiovascular Disease. Pathogens (Basel). 2022;11(5):496.

- Karthikeyan G, Guilherme L. Acute rheumatic fever. The Lancet (British edition). 2018;392(10142):161-74.

- Ruan R, Liu X, Zhang Y, Tang M, He B, Zhang QW, et al. Global, Regional, and National Advances Toward the Management of Rheumatic Heart Disease Based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(13):e028921.

- Steer, AC. Historical aspects of rheumatic fever. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2015;51(1):21-7.

- Wyber R, Noonan K, Halkon C, Enkel S, Cannon J, Haynes E, et al. Ending rheumatic heart disease in Australia: the evidence for a new approach. Medical journal of Australia. 2020;213(S10):S3-S31.

- Parnaby MG, Carapetis JR. Rheumatic fever in indigenous Australian children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46(9):527-33.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Health Performance Framework. Tier 1 - Health status and outcomes. 1.06 Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Canberra: The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.; 2025 [Available from: https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1-06-rheumatic-fever-rheumatic-heart-disease.

- Francis JR, Fairhurst H, Hardefeldt H, Brown S, Ryan C, Brown K, et al. Hyperendemic rheumatic heart disease in a remote Australian town identified by echocardiographic screening. Med J Aust. 2020;213(3):118-23.

- Beaton A, Okello E, Rwebembera J, Grobler A, Engelman D, Alepere J, et al. Secondary Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Latent Rheumatic Heart Disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(3):230-40.

- Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia, 2022. Canberra: AIHW; 2024.

- Bray JJ, Thompson S, Seitler S, Ali SA, Yiu J, Salehi M, et al. Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of rheumatic fever recurrence and progression to rheumatic heart disease. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2024;9:CD015779.

- Gewitz MH, Baltimore RS, Tani LY, Sable CA, Shulman ST, Carapetis J, et al. Revision of the Jones Criteria for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever in the era of Doppler echocardiography: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation (New York, NY). 2015;131(20):1806-18.

- Pulle J, Ndagire E, Atala J, Fall N, Okello E, Oyella LM, et al. Specificity of the Modified Jones Criteria. Pediatrics. 2024;153(3).

- Carapetis JR, Currie BJ. Rheumatic fever in a high incidence population: the importance of monoarthritis and low grade fever. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85(3):223-7.

- Ralph AP, Noonan S, Wade V, Currie BJ. The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Med J Aust. 2021;214(5):220-7.

- Kang K, Chau KWT, Howell E, Anderson M, Smith S, Davis TJ, et al. The temporospatial epidemiology of rheumatic heart disease in Far North Queensland, tropical Australia 1997-2017; impact of socioeconomic status on disease burden, severity and access to care. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(1):e0008990.

- Hempenstall A, Howell E, Kang K, Chau KWT, Browne A, Kris E, et al. Echocardiographic Screening Detects a Significant Burden of Rheumatic Heart Disease in Australian Torres Strait Islander Children and Missed Opportunities for its Prevention. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104(4):1211-4.

- Australian census Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2021 [Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/census.

- Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2021.

- Rwebembera J, Marangou J, Mwita JC, Mocumbi AO, Mota C, Okello E, et al. 2023 World Heart Federation guidelines for the echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;21(4):250-63.

- Casey D, Turner P. Australia's rheumatic fever strategy three years on. Med J Aust. 2024;220(4):170-1.

- Kumar M, Little J, Pearce S, MacDonald B, Greenland M, Tarca A, et al. Clinical profile of paediatric acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Western Australia: 1987 to 2020. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2024;60(8):375-83.

- Stacey I, Ralph A, de Dassel J, Nedkoff L, Wade V, Francia C, et al. The evidence that rheumatic heart disease control programs in Australia are making an impact. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health. 2023;47(4):100071-.

- Quinn E, Girgis S, Van Buskirk J, Matthews V, Ward JE. Clinic factors associated with better delivery of secondary prophylaxis in acute rheumatic fever management. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48(12):859-65.

- Lindholm DE, Whiteman IJ, Oliver J, Cheung MMH, Hope SA, Brizard CP, et al. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in children and adolescents in Victoria, Australia. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2023;59(2):352-9.

- Jack S, Moreland NJ, Meagher J, Fittock M, Galloway Y, Ralph AP. Streptococcal Serology in Acute Rheumatic Fever Patients: Findings From 2 High-income, High-burden Settings. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2019;38(1):e1-e6.

- Lawrence JG, Carapetis JR, Griffiths K, Edwards K, Condon JR. Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease: Incidence and Progression in the Northern Territory of Australia, 1997 to 2010. Circulation (New York, NY). 2013;128(5):492-501.

- Davidson L, Knight J, Bowen AC. Skin infections in Australian Aboriginal children: a narrative review. Med J Aust. 2020;212(5):231-7.

- Ricciardo BM, Kessaris HL, Cherian S, Kumarasinghe SP, Amgarth-Duff I, Sron D, et al. Healthy skin for children and young people with skin of colour starts with clinician knowledge and recognition: a narrative review. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2025;9(4):262-73.

- Baker MG, Gurney J, Moreland NJ, Bennett J, Oliver J, Williamson DA, et al. Risk factors for acute rheumatic fever: A case-control study. The Lancet regional health Western Pacific. 2022;26:100508-.

- Oliver J, Bennett J, Thomas S, Zhang J, Pierse N, Moreland NJ, et al. Preceding group A streptococcus skin and throat infections are individually associated with acute rheumatic fever: evidence from New Zealand. BMJ global health. 2021;6(12):e007038.

- Thomas HMM, Enkel SL, Mullane M, McRae T, Barnett TC, Carapetis JR, et al. Trimodal skin health programme for childhood impetigo control in remote Western Australia (SToP): a cluster randomised, stepped-wedge trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2024;8(11):809-20.

- Woods JA, Sodhi-Berry N, MacDonald BR, Ralph AP, Francia C, Stacey I, et al. A multijurisdictional cohort study. Australian health review. 2024.

- Ben-Dov I, Berry E. Acute rheumatic fever in adults over the age of 45 years: an analysis of 23 patients together with a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1980;10(2):100-10.

- Chan K, Cullen T, Ralph A, Ilton M, Marangou J. Acute Rheumatic Fever Diagnosis in Older Adults. Heart, Lung and Circulation. 2019;28:S50.

- Basaglia A, Kang K, Wilcox R, Lau A, McKenna K, Smith S, et al. The aetiology and incidence of infective endocarditis in people living with rheumatic heart disease in tropical Australia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023;42(9):1115-23.

- Ralph AP, Noonan S, Wade V, Currie BJ. The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Medical Journal of Australia. 2021;214(5):220-7.

- de Dassel JL, de Klerk N, Carapetis JR, Ralph AP. How Many Doses Make a Difference? An Analysis of Secondary Prevention of Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24):e010223.

- Coffey PM, Ralph AP, Krause VL. The role of social determinants of health in the risk and prevention of group A streptococcal infection, acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: A systematic review. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2018;12(6):e0006577.

- Doran J, Canty D, Dempsey K, Cass A, Kangaharan N, Remenyi B, et al. Surgery for rheumatic heart disease in the Northern Territory, Australia, 1997-2016: what have we gained? BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(3).

- Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2021 [Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/socio-economic-indexes-areas-seifa-australia/latest-release.

- Hanson J, Smith S, Stewart J, Horne P, Ramsamy N. Melioidosis - a disease of socioeconomic disadvantage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(6):e0009544.

- Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: Report by the Director-General. Geneva, Switzerland World Health Organisation (WHO) Executive Board; 2018.

- Agenson T, Katzenellenbogen JM, Seth R, Dempsey K, Anderson M, Wade V, et al. Case Ascertainment on Australian Registers for Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17, 5505. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| High-risk individuals | All other individuals |

|---|---|

| Major manifestations | |

|

|

| Minor manifestations | |

|

|

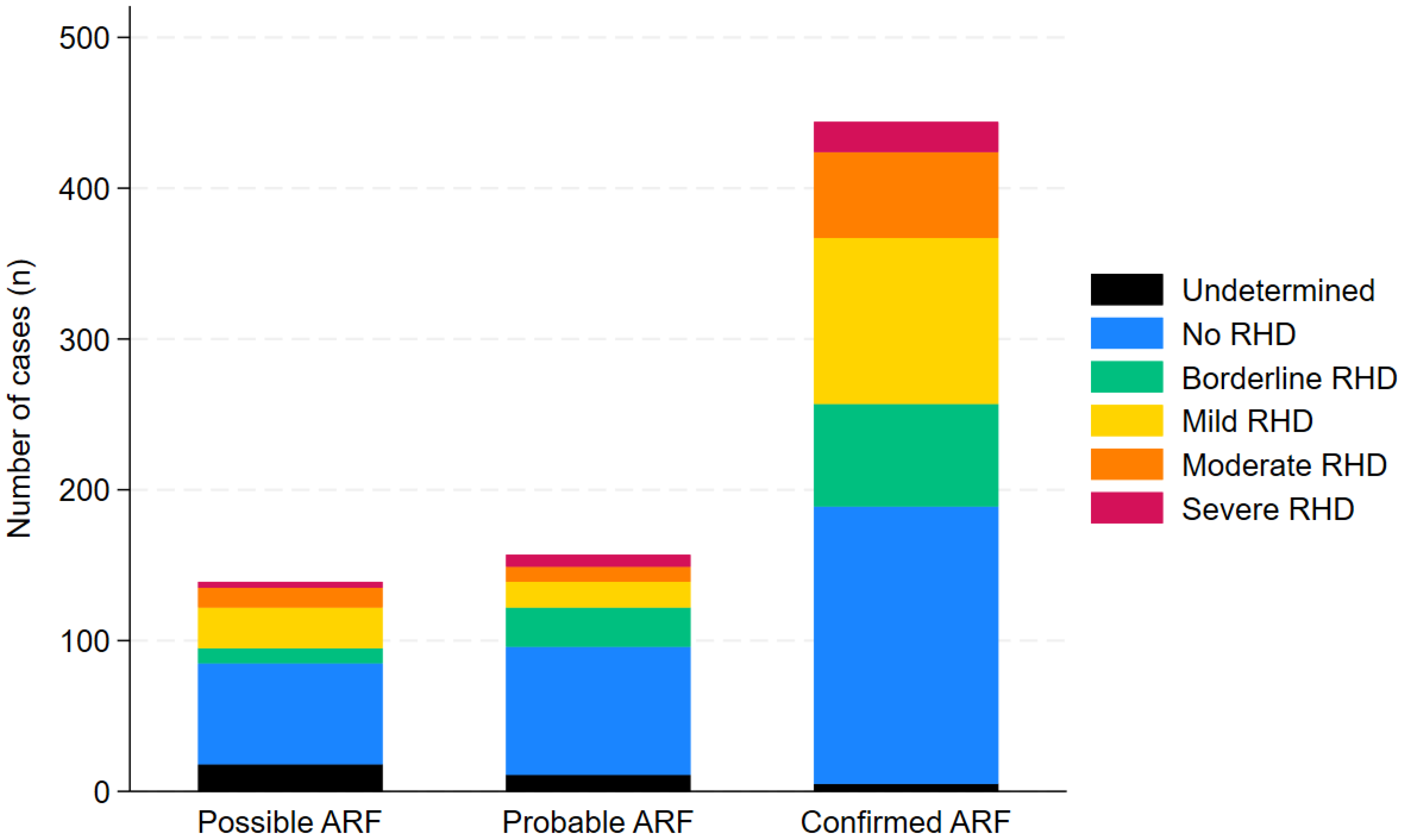

| All n=830 | Confirmedn=492 | Probablen=180 | Possiblen=158 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <5 years | 20 (2%) | 15 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (3%) |

| 5-9 years | 157 (19%) | 116 (24%) | 25 (14%) | 16 (10%) |

| 10-14 years | 234 (28%) | 163 (33%) | 47 (26%) | 24 (15%) |

| 15-19 years | 143 (17%) | 85 (17%) | 26 (14%) | 32 (20%) |

| 20-24 years | 102 (12%) | 44 (9%) | 24 (13%) | 34 (22%) |

| ≥ 25 years | 174 (21%) | 69 (14%) | 57 (32%) | 48 (30%) |

| Population group | ||||

| Aboriginal | 429 (52%) | 248 (50%) | 96 (53%) | 85 (54%) |

| Torres Strait Islander | 237 (29%) | 145 (29%) | 52 (29%) | 40 (25%) |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 119 (14%) | 64 (13%) | 25 (14%) | 30 (19%) |

| Māori | 6 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| Pacific Islander | 12 (1%) | 11 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| Other High Risk | 13 (1%) | 10 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 0 |

| Other Low Risk | 14 (1%) | 9 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 2 (1%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 475 (57%) | 264 (54%) | 111 (62%) | 100 (63%) |

| Male | 355 (43%) | 228 (46%) | 69 (38%) | 58 (37%) |

| Geography | ||||

| CHHHS | 371 (45%) | 217 (44%) | 88 (49%) | 66 (42%) |

| TCHHS | 459 (55%) | 275 (56%) | 92 (51%) | 92 (58%) |

| Confirmedn=492 | Probablen=180 | Possiblen=158 | Odds ratio a(95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Criteria | |||||

| Polyarthralgia | 231 (47%) | 95 (53%) | 76 (48%) | 0.86 (0.66-1.14) | 0.30 |

| Monoarthritis | 59 (12%) | 17 (9%) | 23 (15%) | 1.02 (0.66-1.56) | 0.95 |

| Polyarthritis | 130 (26%) | 37 (21%) | 14 (9%) | 2.02 (1.41-2.89) | <0.001 |

| Carditis | 89 (18%) | 13 (7%) | 2 (1%) | 4.76 (2.70-8.38) | <0.001 |

| Sydenham's Chorea | 53 (11%) | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Erythema Marginatum | 8 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1.10 (0.36-3.39) | 0.87 |

| Subcutaneous Nodules | 6 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1.03 (0.29-3.68) | 0.96 |

| Minor Criteria | |||||

| Monoarthralgia | 32 (7%) | 14 (8%) | 21 (13%) | 0.60 (0.36-0.99) | 0.047 |

| Fever | 295 (60%) | 69 (38%) | 45 (28%) | 2.94 (2.20-3.93) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged PR interval | 161 (33%) | 23 (13%) | 12 (8%) | 4.21 (2.83-6.27) | <0.001 |

| CRP >30mg/L | 358 (73%) | 104 (58%) | 48 (30%) | 3.27 (2.44-4.38) | <0.001 |

| ESR >30mm/hr | 296 (60%) | 102 (57%) | 52 (33%) | 1.80 (1.36-2.39) | <0.001 |

| Evidence of GAS infection | |||||

| Median (IQR) ASOT (U/mL) | 768 (496-1190) | 578 (347-1000) | 395 (223-597) | 1.10 (1.07-1.14) b | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) Anti-DNase B (U/mL) | 650 (429-1015) | 586 (389-954) | 391 (257-735) | 1.06 (1.03-1.10)b | <0.001 |

| Positive skin swab | 26 (5%) | 9 (5%) | 8 (5%) | 1.05 (0.56-1.97) | 0.87 |

| Positive throat swab | 43 (9%) | 15 (8%) | 12 (8%) | 1.10 (0.67-1.82) | 0.70 |

| Positive blood culture | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Stated history | 96 (20%) | 43 (24%) | 27 (17%) | 0.93 (0.66-1.31) | 0.67 |

| Unknown | 326 (66%) | 113 (63%) | 111 (70%) | 1.00 (0.75-1.34) | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).