1. Introduction

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) occurs as a short-term nonsuppurative sequela of pharyngitides caused by

Streptococcus pyogenes [

1]: among the Streptococci being classified according to the carbohydrate composition of cell wall antigens such as polysaccharides (into the groups A, B, C, E, F and G), teichoic acids, lipoteichoic acid as well as sequence variations in the

emm gene encoding the M protein, only group A beta-hemolytic

Streptococcus can give rise to ARF [

2]. The immune-mediated mechanisms behind this important disease have not yet been fully elucidated, and only a small number of specific

emm/M protein types can be considered “rheumatogenic”, i.e., potentially characterized by the possibility of inducing ARF, with remarkable differences between developing and developed countries [

3]. The most dreaded ARF-related complication is rheumatic heart disease (RHD), which usually brings about substantial effects on the individual’s health, often resulting in chronic illness and even premature death [

4]. ARF and RHD cause a large worldwide burden of morbidities across the world, but

clues contributing to the specific involvement of heart in ARF remain obscure: indeed, RHD is still a major cause of cardiac deaths in the developing countries due to poor rates of diagnosis and lack of a proper ARF treatment or prophylaxis [

3]. Despite the widespread application of Jones’ criteria, carditis may result either underdiagnosed or sometimes overdiagnosed, but the only strategy available for disease control is secondary prophylaxis with long-acting penicillin G-benzathine administered every three weeks [

4]. However, the definite reasons for heart valve injuries occurring after attacks of ARF are not understood. The general aim of this retrospective study was to provide a comprehensive description of the clinical and labwork characteristics of a single-centre cohort of patients with ARF hospitalized in our Department during a 20-year-period and to assess whether there were any clinical or laboratory factors specifically associated with RHD.

2. Patients and Methods

Out of 90 eligible pediatric patients for this study, all with a post-streptococcal illness, 11 were not considered as shown to be affected with post-streptococcal arthritis, and 1 was excluded due to incomplete inpatient data available. Patients considered in our evaluation were all Caucasian and had an average age at the diagnosis of ARF of 102,7±33 months (range 29-180 months); all of them were managed at the Department of Life Sciences and Public Health of our University in Rome. The whole study was performed in line with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments: all patients’ caregivers were informed about the aims of this retrospective evaluation, and all of them signed a written consent for both unrestricted access to patients’ medical charts and evaluation of children’s anonymized data. The Local Ethical Committee authorized different study protocols related to nutritional issues (including vitamin D) in patients with complex diseases as well as rare conditions and rheumatologic diseases (approval code: 2105; approval date: 05.02.2019).

A comprehensive questionnaire focused on the eventual exposure to risk factors during the four weeks prior to illness and a general interview to parents’ patients were yielded at the time of first clinical assessment. All patients were diagnosed with ARF according to the modified Jones criteria, designed to establish the initial attack of ARF through a defined mix of major and minor manifestations with evidence of a previous group A Streptococcus infection. Indeed, a throat swab for group A Streptococcus pyogenes had been performed in every patient of the cohort.

Exclusion criteria for the participation to our study were comorbidities with immunodeficiency or other immune-mediated disorders, such as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and blood diseases. Demographic data, month of the year at diagnosis, clinical signs, and laboratory variables at disease onset, including C-reactive protein (CRP) and anti-streptolysin-O titer (ASO), were retrieved by medical charts. Serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)-vitamin D] were also retrieved, after a measurement performed by automated chemiluminescence immunoassay technology within the first two weeks after patients’ hospitalization. All patients diagnosed with ARF underwent Doppler echocardiography to assess any cardiac involvement [

5], and echocardiography examinations were repeated on the long run, as case by case required. All patients had a minimal follow-up duration of at least 5 years, except for the most recently diagnosed cases.

3. Statistical Analysis

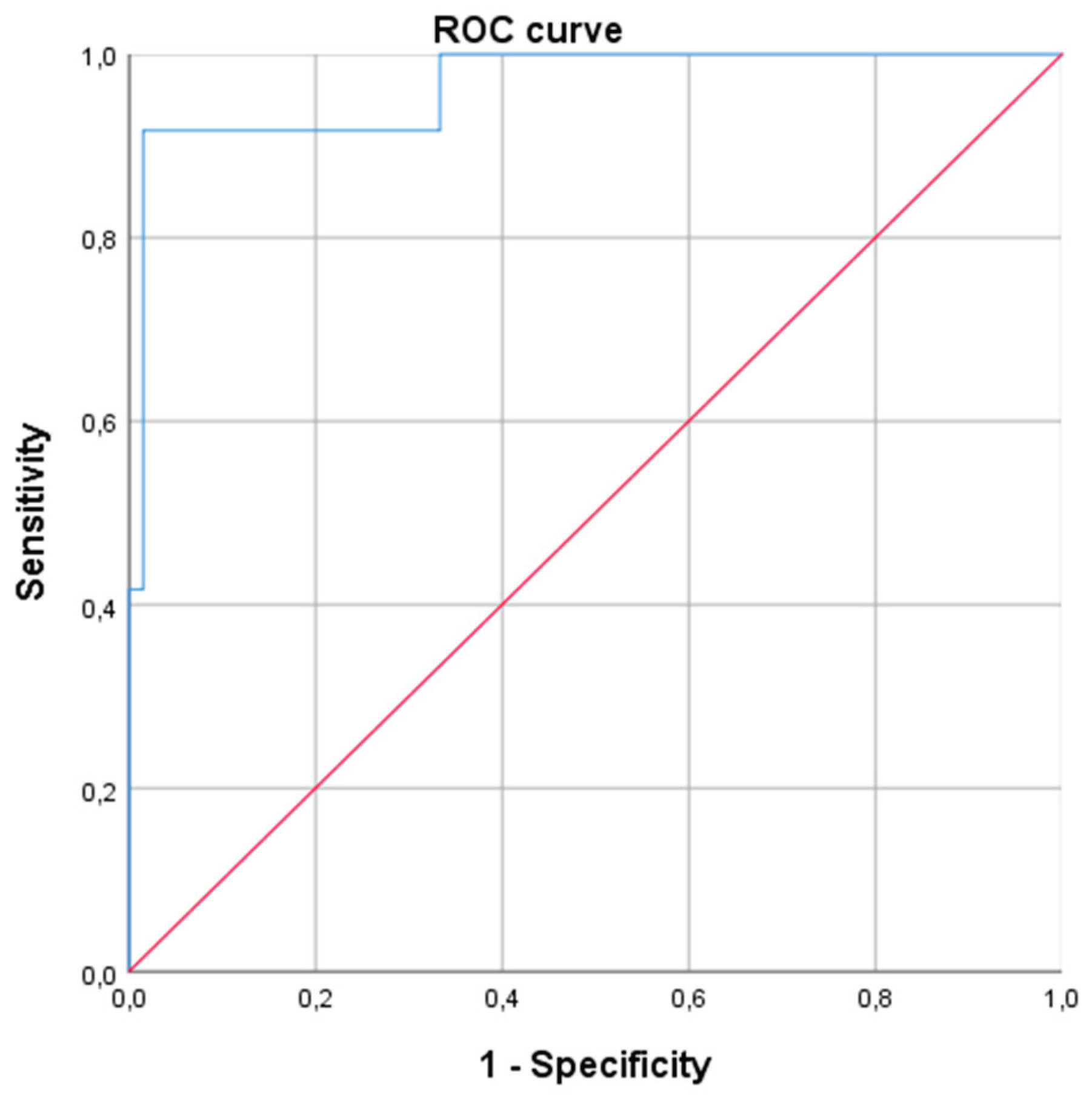

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables and as count (percentages) for categorical variables. The Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables, while the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (depending on group size) was applied for categorical data. Additionally, we performed a multinomial logistic regression, adjusting for sex and age and including all factors that showed a p-value of less than 0.2 at the univariate analysis. Furthermore, we constructed a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of serum vitamin D levels in predicting cardiac involvement for patients with ARF. Finally, we used Youden’s test to identify the optimal cut-off value for vitamin D to distinguish patients with and without cardiac involvement, and we also calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for that threshold.

4. Results

The enrolled patients were of Caucasian ethnicity, and all resided in the central or southern Italy (at a latitude varying from 41°13’N to 37°56’N, with ultraviolet index of 1-3 in wintertime): 50% of them (39) were males. Fifty patients (64%) had resulted positive for

Streptococcus pyogenes on the pharyngeal swab, while the mean anti-streptolysin O titer was 1433±1171 IU/L in the totality of patients. Thirty-nine of them (50%) had arthritis in at least one joint, and the median number of involved joints was 0.5, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 0-2. Seventy percent of patients (55) reported arthralgia, and 23% (18) exhibited neurological symptoms (chorea) of varying severity. Cardiac involvement was observed in 66 patients (84.6% of the cohort). Among these, 63 patients (81%) displayed mitral regurgitation (mild in 41, moderate in 19, and severe in 3), while 45 (58%) showed aortic valve regurgitation (mild in 35, moderate in 7, and severe in 3). Twenty-four out of 66 patients with carditis (36.4%) had single valve involvement, while 42 (63.6%) had both mitral and aortic valve involvement. Four patients (5%) presented signs of myocarditis, and four (5%) had also pericarditis. The most common electrocardiographic abnormality was an increased PR interval duration (first-degree atrioventricular block), that was found in 12 patients (15% of the cohort). Additionally, 15 patients (19%) showed a left ventricular dilation on echocardiography, and 2 had a severe heart disease at an extent to require specific heart surgical intervention. As conceivable, a significantly higher proportion of patients with cardiac involvement required corticosteroid treatment compared to those without carditis (59%

versus 25%,

p=0.05). The distribution of the revised Jones criteria for ARF by patients considered within this study are shown in

Table 1.

By dividing patients based on the presence (or absence) of carditis, we observed no significant differences regarding age, sex, and other ARF signs (fever, arthritis, arthralgia, chorea, and/or skin lesions). Serum vitamin D levels were significantly lower in patients with ARF displaying cardiac involvement compared to those without (18±6

versus 38±8 ng/mL,

p=0.0001). In addition, the proportion of patients with normal serum vitamin D level was significantly higher in those without cardiac involvement (92%) compared to those with carditis (3%,

p=0.0001). These data are also schematically included in

Table 1. No differences were found between the two groups regarding the period of diagnosis: 33 patients (42% of the cohort) had their vitamin D level measured during spring or summer season (from May to October), while the remaining were tested during wintertime. Specifically, 29 patients with carditis (44% of the cohort) were diagnosed during winter, compared to 4 patients without cardiac involvement (33.3% of the cohort,

p=0.54). To account for any potential confounding factors we performed a multivariate analysis using logistic regression, adjusting for sex, age, and period of diagnosis (spring/summer or fall/winter) and including all the variables that showed a

p value ≤0.2 an the univariate analysis. The results of the logistic regression have been shown in the

Table 2.

Serum levels of 25(OH)-vitamin D above 30 ng/mL assessed at the moment of ARF diagnosis were strongly associated with the presence of cardiac involvement. Concurrently, we also used vitamin D levels and presence of cardiac involvement to build a ROC curve and evaluate its diagnostic accuracy (

Figure 1,

Table 3). The accuracy evaluated as area under the ROC curve was outstanding (0.965).

Therefore, we applied the Youden index and the optimal vitamin D cut-off value for diagnosing cardiac involvement in ARF was found to be 32.5 ng/mL; the results of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values for this cut-off are presented in

Table 4.

To assess whether vitamin D levels were correlated with the severity of cardiac involvement we divided patients with RHD into two groups: the first included patients with a mild valvular involvement, while the second comprised those having moderate-to-severe involvement of heart valves. We chose to combine patients with moderate and moderate/severe manifestations due to the limited number of patients with a severe involvement. Patients were classified into the moderate/severe group if echocardiographic findings showed at least one cardiac valve with moderate or severe regurgitation, or if they had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. All patients who did not meet these criteria were assigned to the mild cardiac involvement group.

As a result, the presence of arthritis and vitamin D levels between 20 and 30 ng/dL were associated with mild RHD, whereas vitamin D levels below 20 ng/mL were linked to moderate and severe forms of RHD. The male sex and lower mean serum levels of vitamin D demonstrated a trend (not statistically significant) towards an association with moderate-to-severe carditis (

Table 5).

We also performed a multiple logistic regression analysis to correct these results for age, sex and season at which ARF was diagnosed: the analysis confirmed that presence of arthritis was associated to milder forms of RHD; conversely, vitamin D level lower than 20 ng/mL was significantly related to moderate and severe forms of carditis (

Table 6).

5. Discussion

The identification of ARF represents a keystone to diagnose permanent heart valve damage as a result of an immune-mediated response to

Streptococcus pyogenes in genetically predisposed individuals: untreated or undertreated pharyngeal infections caused by group A

Streptococcus can determine RHD, which is largely common in countries with socioeconomic disadvantage [

6,

7]. Global estimates suggest that 62-78 million individuals may have RHD with potential death of above 1.4 million per year [

8]. The mitral valve is the most widely involved in RHD, but aortic valve involvement occurs in ¼ of the cases as well [

9]. A broader knowledge about risk factors and pathophysiologic mechanisms of RHD is needed to optimize prophylaxis strategies, as an effective treatment of

Streptococcus pyogenes infections could prevent the development of both ARF and RHD. Such strategies may be inaccessible for patients living in low and middle income-countries: in fact, socioeconomic deprivation, household crowding, access to primary health care combined with positive family history have been related in the pathogenesis of ARF [

10]. Indeed, both improvement of living conditions and employment of antimicrobial drugs are thought to have led to ARF virtually disappearing in most high-income countries [

10].

Despite being a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among young people in low- and middle-income countries, the resolution of ARF faces several challenges, including the difficulty of diagnosis and the lack of access to preventive measures [

11].

Several aspects of nutrition may contribute to the risk of ARF, including overall nutritional status with intake of micronutrients [

12]. In particular, the serum levels of 25(OH)-vitamin D have been related to ARF in the medical literature, though the general incidence of both streptococcal infections and ARF makes seasonal peaks at winter and spring months when 25(OH)-vitamin D levels are expected to be lower because of the lack of sunlight exposure [

13]. A host of epidemiological studies support the association between vitamin D deficiency and susceptibility or severity of different autoimmune diseases. For instance, a poor nutritional status including low serum level of 25(OH)-vitamin D has been found in Nepalese populations with confirmed RHD compared to healthy controls, and people with vitamin D insufficiency were also found to display a higher risk of developing RHD in comparison to people with normal vitamin D concentrations [

14]. Yusuf et al. found significantly lower levels of 25(OH)-vitamin D in 55 patients with RHD having mild to moderately calcified valves (median serum level of 20.4 ng/ml) and 55 patients with severely calcified valves (median serum level of 11.4 ng/ml) as compared to those with non-calcified less severely damaged valves [

15].

Vitamin D, known for its essential role in calcium and bone homeostasis, has multiple effects beyond the skeleton, including regulation of immunity pathways and modulation of autoimmune processes: unfortunately, vitamin D deficiency is a global health problem, particularly in children, and several reports have revealed suboptimal serum supply of 25(OH)-vitamin D in children with IgA vasculitis, periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical adenitis syndrome, and Kawasaki disease [

16,

17,

18]. At the intersection of rheumatology and cardiovascular medicine there is a growing awareness that recognizes how individuals with autoimmune and autoinflammatory conditions will have a much higher likelihood of developing heart diseases [

19]. Even children with hereditary periodic fever syndromes are prone to display heterogeneous heart complications [

20,

21], though the most relevant childhood condition associated with cardiovascular abnormalities in children living in developed countries of the world is Kawasaki disease [

22], requiring a prompt treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin to decrease the disease-associated inflammatory burden and prevent the formation of a structural damage within coronary arteries [

23].

There are few studies showing the relationship between vitamin D and ARF or RHD. Onan et al. prospectively found lower levels of 25(OH)-vitamin D levels in 77% of children with ARF in comparison with age-matched healthy controls having innocent murmurs during a 15 month-period, with nonsignificant correlation with carditis severity [

24]. We also know that the production of vascular endothelial growth factor is regulated by vitamin D, and that endothelial cell dysfunction might have a role in heart valve remodeling and in initiating the process of RHD [

25,

26]. A further Arabian study identified an association between the GC2 polymorphism of the vitamin D-binding protein (VDBP) and ARF [

27]: VDBP belongs to the albumin family and is essential for the intracellular transport of vitamin D to various cell types, including macrophages and B lymphocytes [

28]. VDBP gene polymorphisms have been also associated with increased risk of mitral and aortic valve calcifications in children with RHD [

29,

30].

This present study of ours has revealed that vitamin D level is the only factor statistically and independently associated with the development of cardiac involvement in patients with ARF, and that vitamin D cut-off of 32.5 ng/mL exhibits exceptional diagnostic accuracy for suggesting RHD, with relevant high sensitivity and specificity. Interestingly, very low values of vitamin D (˂20 ng/mL) have resulted associated with severe RHD.

In all truth, this study has several important limitations. Firstly, although patient histories were rigorously reviewed by a panel of experienced clinicians using the ARF revised Jones criteria, adjustment for potential confounding factors contributing to hypovitaminosis D, such as children’s nutritional habits, was not performed. In addition, geoepidemiological variations in ARF were not considered, and several well-known risk factors for vitamin D deficiency in children, including limited outdoor activity (which reduces sunlight exposure) and obesity, were not accounted. Furthermore, the retrospective design, absence of non-white children, and the relatively low number of ARF cases over the past two decades (due to the single-centre nature of the study) may have influenced the final results and hinder the generalizability of our findings.

6. Conclusions

The development of RHD in subsets of pediatric patients with ARF is not clearly explained: this study provides a freeze image of the vitamin D status at diagnosis of ARF, without considering specific time points.

In particular, hypovitaminosis D has been identified as the only independent factor significantly associated with both RHD development and severity in a single-center cohort of children with ARF evaluated over two decades.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: DR and MC; methodology and data curation: DR, GP and MC; writing original draft preparation: DR; review and editing: MC; cardiologic assessments and critical evaluation of the paper: GDR, ABD and CDP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Local Ethical Committee of the Università Cattolica Sacro Cuore, Rome (Italy), authorized study protocols related to nutritional issues in patients with complex and rare diseases as well as rheumatologic diseases (approval code: 2105; approval date: 05.02.2019).

Informed Consent Statement

A formal written informed consent was obtained from all caregivers of participants included in the study to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families of children participating in this retrospective study. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARF |

acute rheumatic fever |

| RHD |

rheumatic heart disease |

| ROC |

receiver operating characteristic |

| NSAIDS |

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

References

- Zhang, J.; Jia, S.; Chen, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, W. Recent advances on the prevention and management of rheumatic heart disease. Glob. Heart 2025, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Crombrugghe, G.; Baroux, N.; Botteaux, A.; Moreland, N.J.; Williamson, D.A.; Steer, A.C.; Smeesters, P.R. The limitations of the rheumatogenic concept for group A Streptococcus: systematic review and genetic analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, S.; Krishna, M.P.; Sasidharan, A.; Mithun, C.B. Acute rheumatic fever and post-streptococcal reactive arthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2025, 39, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirani, K.; Rwebembera, J.; Webb, R.; Beaton, A.; Kado, J.; Carapetis, J.; Bowen, A. Acute rheumatic fever. Lancet 2025, 405, 2164–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewitz, M.H.; Baltimore, R.S.; Tani, L.Y.; Sable, C.A.; Shulman, S.T.; Carapetis, J. Revision of the Jones Criteria for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever in the era of Doppler echocardiography: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 131, 1806–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, G.; Guilherme, L. Acute rheumatic fever. Lancet 2018, 392, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Guo, D.; Yu, D. A mini review of the pathogenesis of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1447149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, K.K.; Gupta, A. Predictors of mortality in chronic rheumatic heart disease. Indian J. Med. Res. 2016, 144, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomo, V.T. Epidemiology and prevention of valvular heart diseases and infective endocarditis in Africa. Heart 2007, 93, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutarelli, A.; Nogueira, G.P.G.; Pantaleao, A.N.; Nogueira, A.; Giavina-Bianchi, B.; Fonseca, I.M.G.; Nascimento, B.R.; Dutra, W.O.; Levine, R.A.; Nunes, M.C.P.; PRIMA Network. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in first-degree relatives of index-cases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Heart 2025, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupieri, A.; Jha, P.K.; Nizet, V.; Dutra, W.O.; Nunes, M.C.P.; Levine, R.A.; Aikawa, E. Rheumatic heart valve disease: navigating the challenges of an overlooked autoimmune disorder. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1537104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.G.; Gurney, J.; Oliver, J.; Moreland, N.J.; Williamson, D.A.; Pierse, N.; Wilson, N.; Merriman, T.R.; Percival, T.; Murray, C.; Jackson, C.; Edwards, R.; Foster Page, L.; Chan Mow, F.; Chong, A.; Gribben, B.; Lennon, D. Risk factors for acute rheumatic fever: literature review and protocol for a case-control study in New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A.; Aydın, A.; Demir, T.; Koşger, P.; Özdemir, G.; Uçar, B.; Kilic, Z. Acute rheumatic fever: a single center experience with 193 clinical cases. Minerva Pediatr. 2016, 68, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thorup, L.; Hamann, S.A.; Tripathee, A.; Koirala, B.; Gyawali, B.; Neupane, D.; Mota, C.C.; Kallestrup, P.; Hjortdal, V.E. Evaluating vitamin D levels in rheumatic heart disease patients and matched controls: a case-control study from Nepal. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0237924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, J.P.J.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Vignesh, V.; Tyagi, S. Evaluation of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in calcific rheumatic mitral stenosis - a cross sectional study. Indian Heart J. 2018, 70, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigante, D.; Guerriero, C.; Silvaroli, S.; Paradiso, F.V.; Sodero, G.; Laferrera, F.; Franceschi, F.; Candelli, M. Predictors of gastrointestinal involvement in children with IgA vasculitis: results from a single-center cohort observational study. Children (Basel) 2024, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigante, D.; Manna, R.; Candelli, M. Exploring the significance of vitamin D insufficiency in the periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome: a single-centre retrospective assessment during the decade 2014-2024. Intern. Emerg. Med.

- Rigante, D.; De Rosa, G.; Delogu, A.B.; Rotunno, G.; Cianci, R.; Di Pangrazio, C.; Sodero, G.; Basile, U.; Candelli, M. Hypovitaminosis D and leukocytosis to predict cardiovascular abnormalities in children with Kawasaki disease: insights from a single-center retrospective observational cohort study. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, F.; Abdulla, M.; Retnowati, F.D.; Al-Khawaga, H.; Alhiraky, H.; Al-Harbi, K.M.; Al-Haidose, A.; Maayah, Z.H.; Abdallah, A.M. Cardio-rheumatic diseases: inflammasomes behaving badly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigante D, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Cantarini L. From the Mediterranean to the sea of Japan: the transcontinental odyssey of autoinflammatory diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 485103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigante, D.; Cantarini, L.; Imazio, M.; Lucherini, O.M.; Sacco, E.; Galeazzi, M.; Brizi, M.G.; Brucato, A. Autoinflammatory diseases and cardiovascular manifestations. Ann. Med. 2011, 43, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, G.; Pardeo, M.; Rigante, D. Current recommendations for the pharmacologic therapy in Kawasaki syndrome and management of its cardiovascular complications. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 11, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rigante, D.; Valentini, P.; Rizzo, D.; Leo, A.; De Rosa, G. , Onesimo, R.; De Nisco, A.; Angelone, D.F.; Compagnone, A.; Delogu, A.B. Responsiveness to intravenous immunoglobulins and occurrence of coronary artery abnormalities in a single-center cohort of Italian patients with Kawasaki syndrome. Rheumatol. Int. 2010, 30, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onan, S.H.; Demirbilek, H.; Aldudak, B.; Bilici, M.; Demir, F.; Yılmazer, M.M. Evaluation of vitamin D levels in patients with acute rheumatic fever. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2017, 18, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Chopra, S.; Rohit, M.K.; Banerjee, D.; Chakraborti, A. Vitamin D regulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor: a triggering cause in the pathogenesis of rheumatic heart disease? Med. Hypotheses 2016, 95, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamali, N.; Sorenson, C.M.; Sheibani, N. Vitamin D and regulation of vascular cell function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 314, H753–H765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, G.M.; Eales, L.J.; Nye, K.E.; Majeed, H.A.; Yousof, A.M.; Behbehani, K.; Rook, G.A. An association between Gc (vitamin D-binding protein) alleles and susceptibility to rheumatic fever. Immunology 1989, 67, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bouillon, R.; Schuit, F.; Antonio, L.; Rastinejad, F. Vitamin D binding protein: a historic overview. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2020, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.; Mohamadi-Nori, E.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Tanhapour, M.; Elahi-Rad, S.; Bahrehmand, F.; Rahimi, Z.; Pourmotabbed, T. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D receptor genotypes and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are associated with development of aortic and mitral valve calcification and coronary artery diseases. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 5225–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, A.I.; Meza-Meza, M.R.; Vizmanos-Lamotte, B.; Parra-Rojas, I.; de la Cruz-Mosso, U. Association of vitamin D metabolism gene polymorphisms with autoimmunity: evidence in population genetic studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).