Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

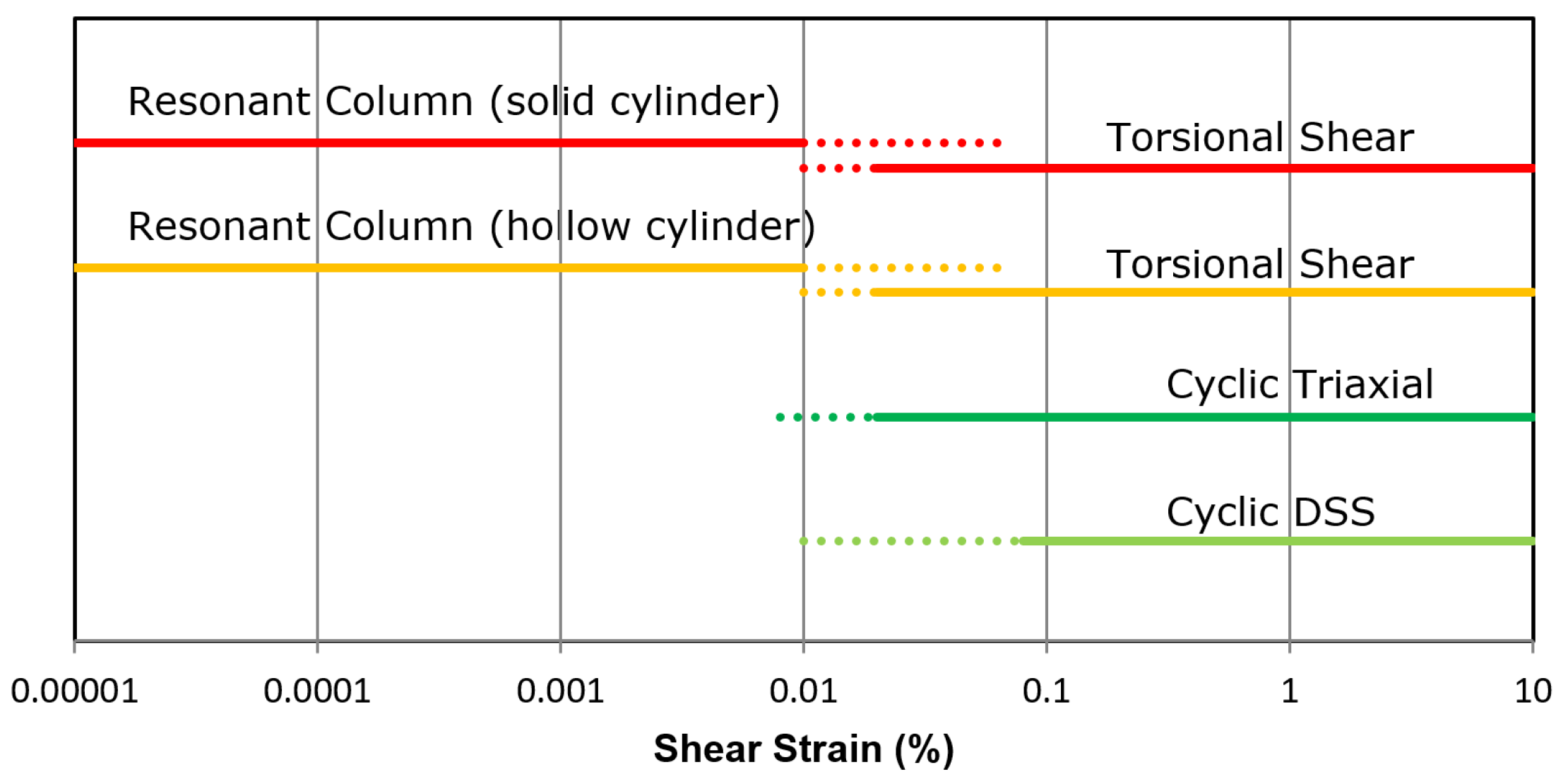

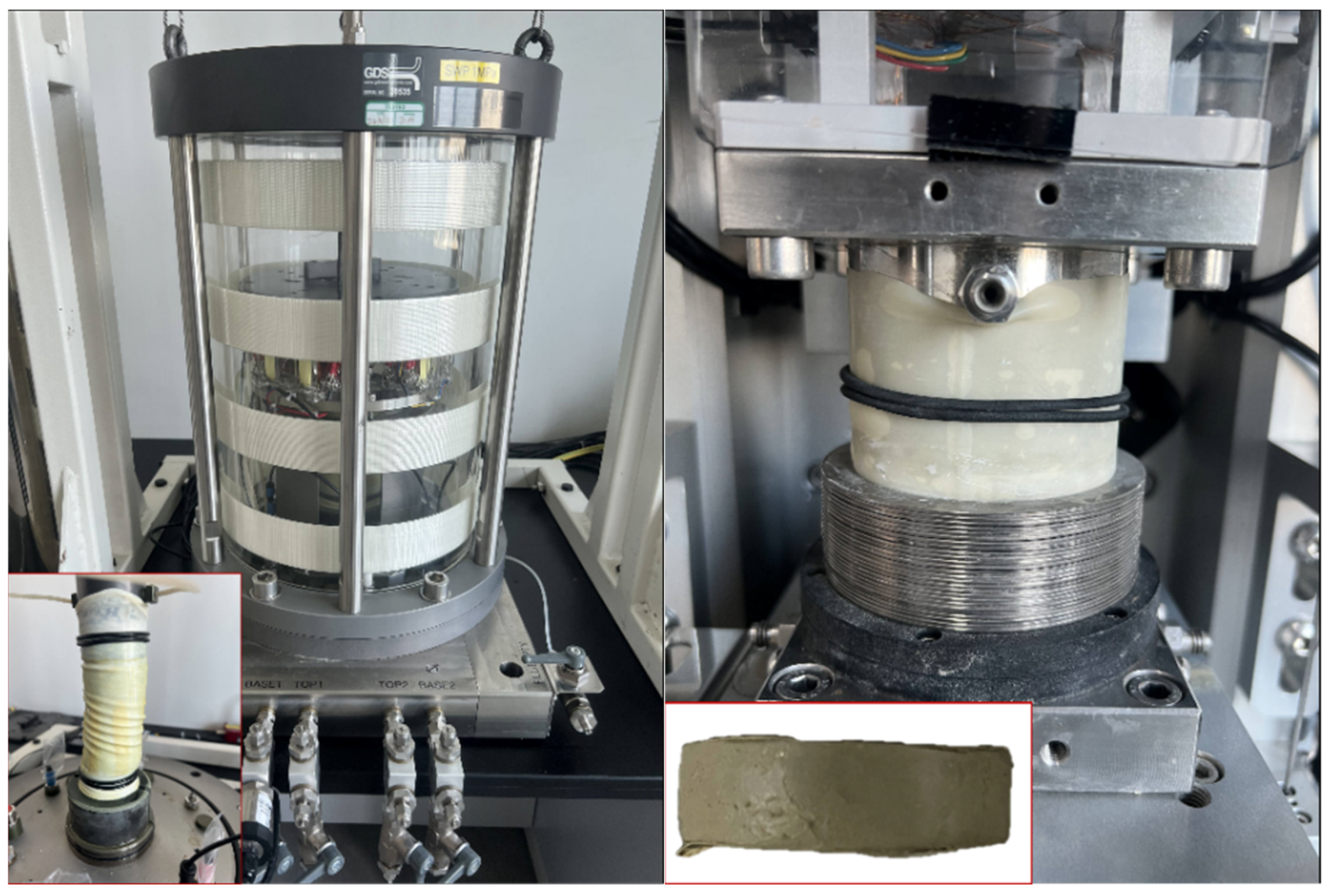

2. Experimental Method

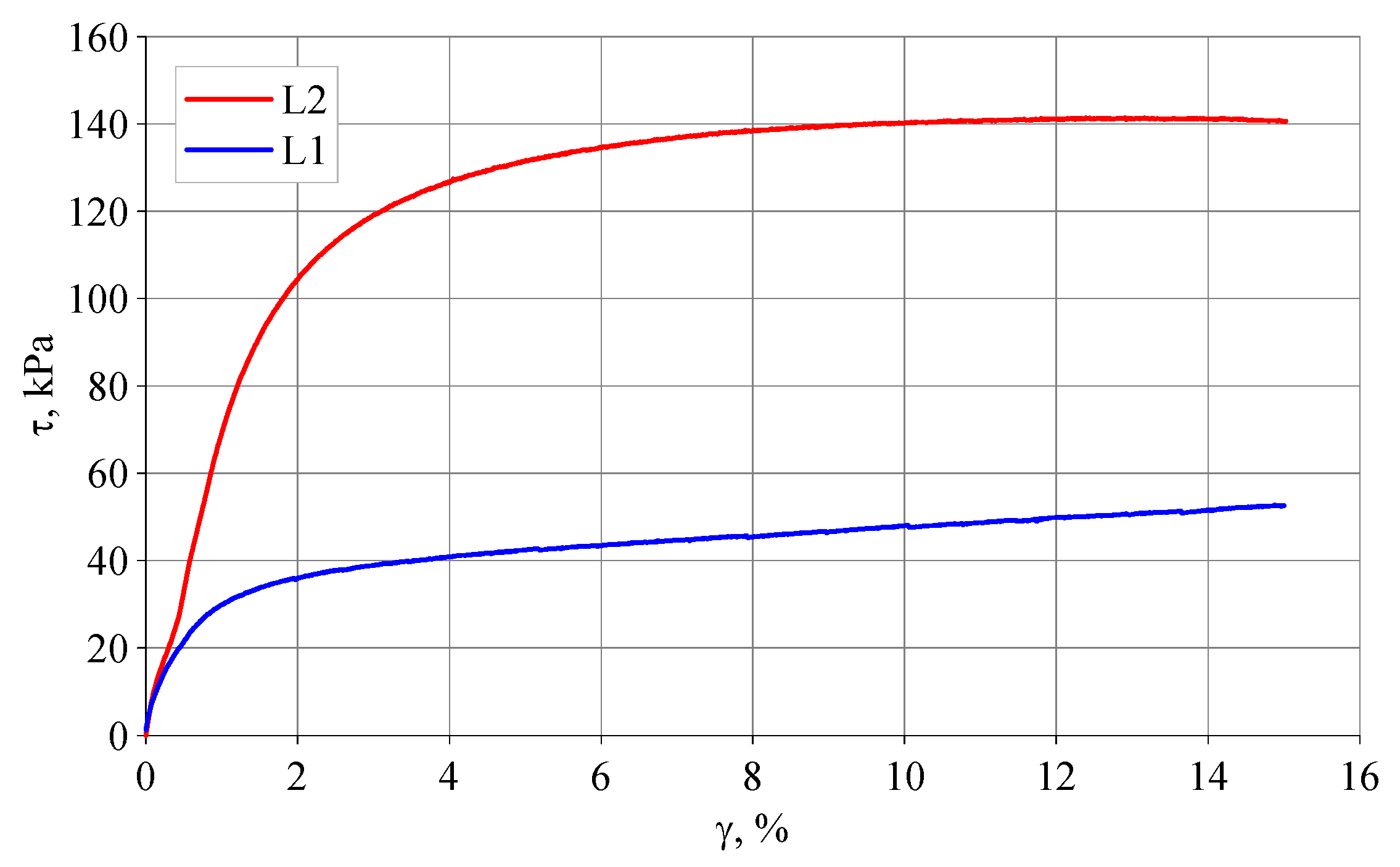

2.1. Soil Sample Overview

2.2. Experimental Plan

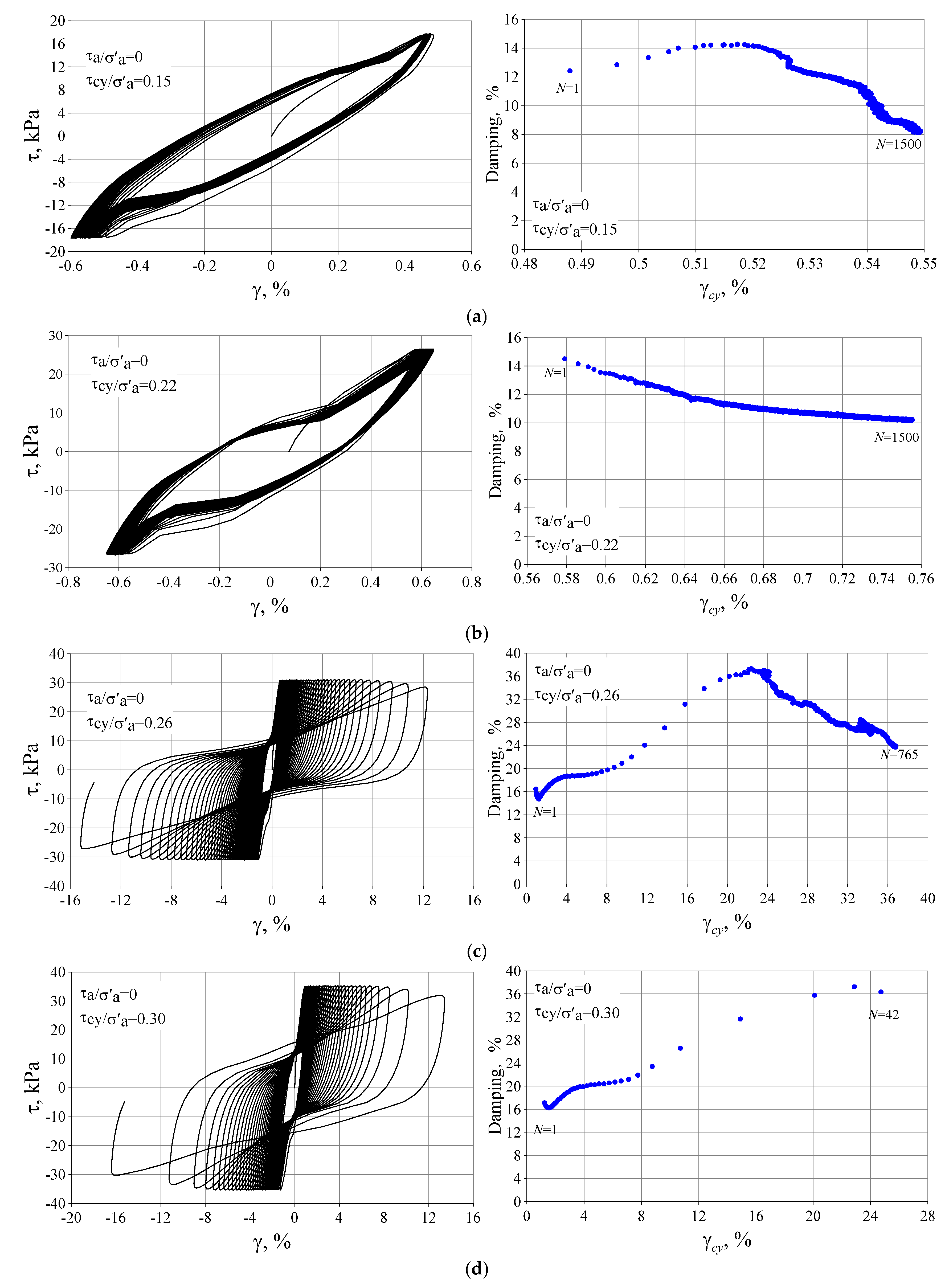

3. Results and Analysis

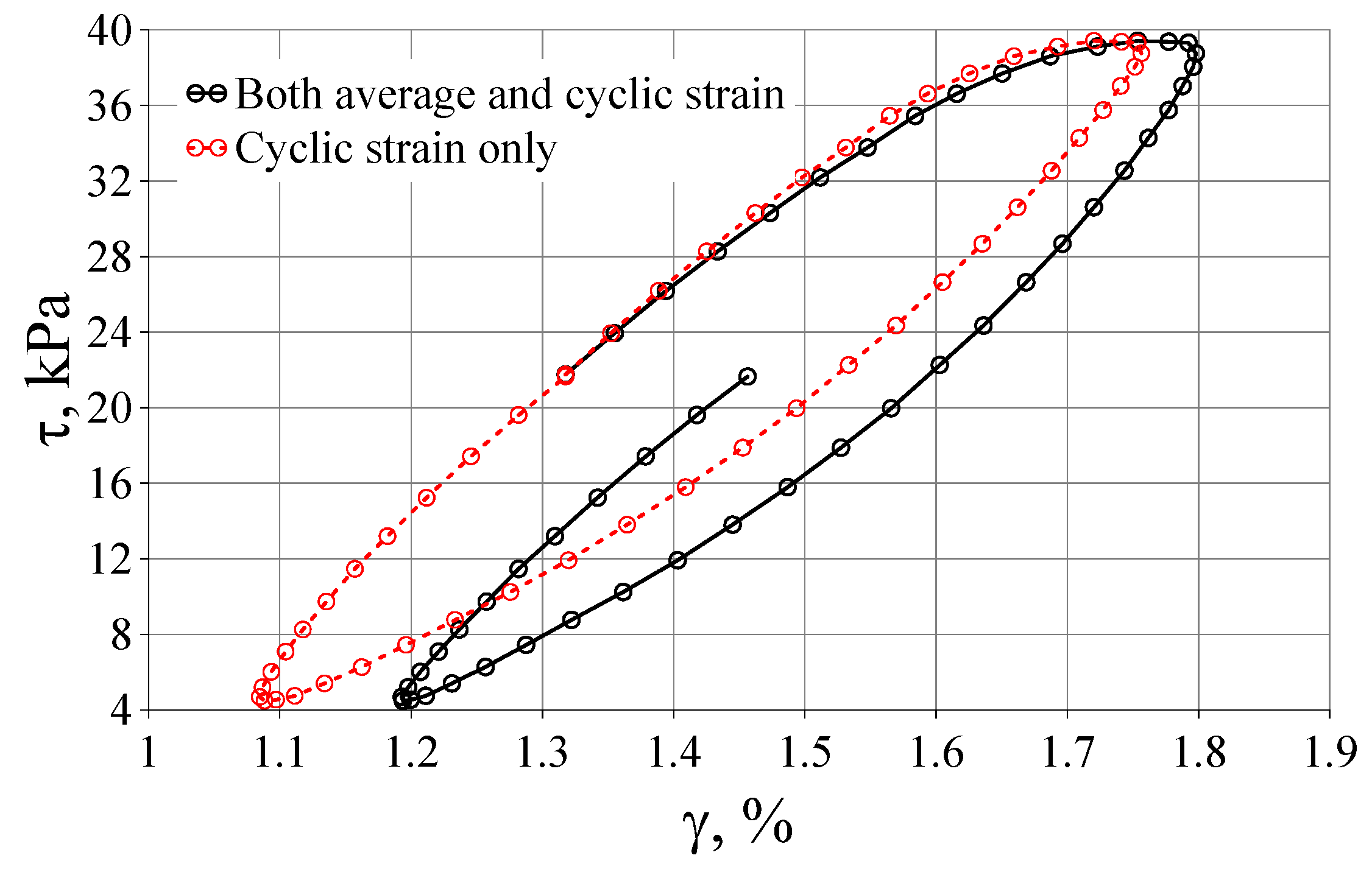

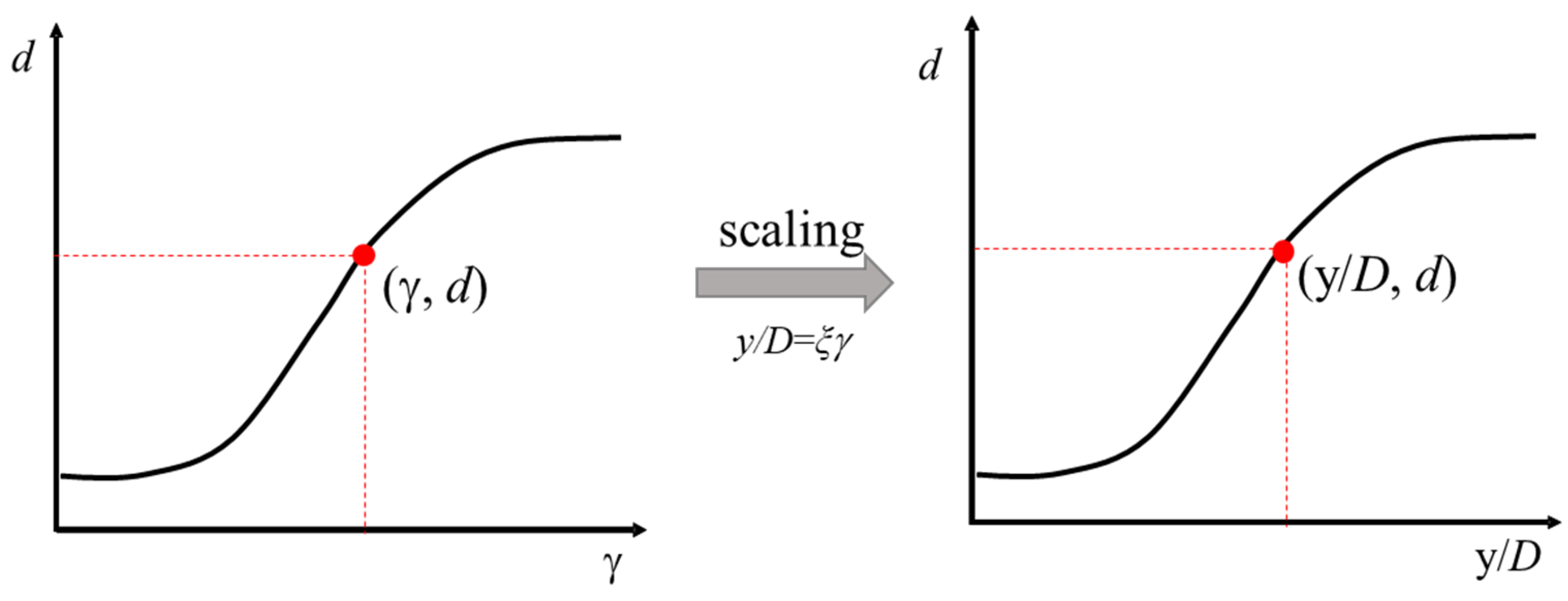

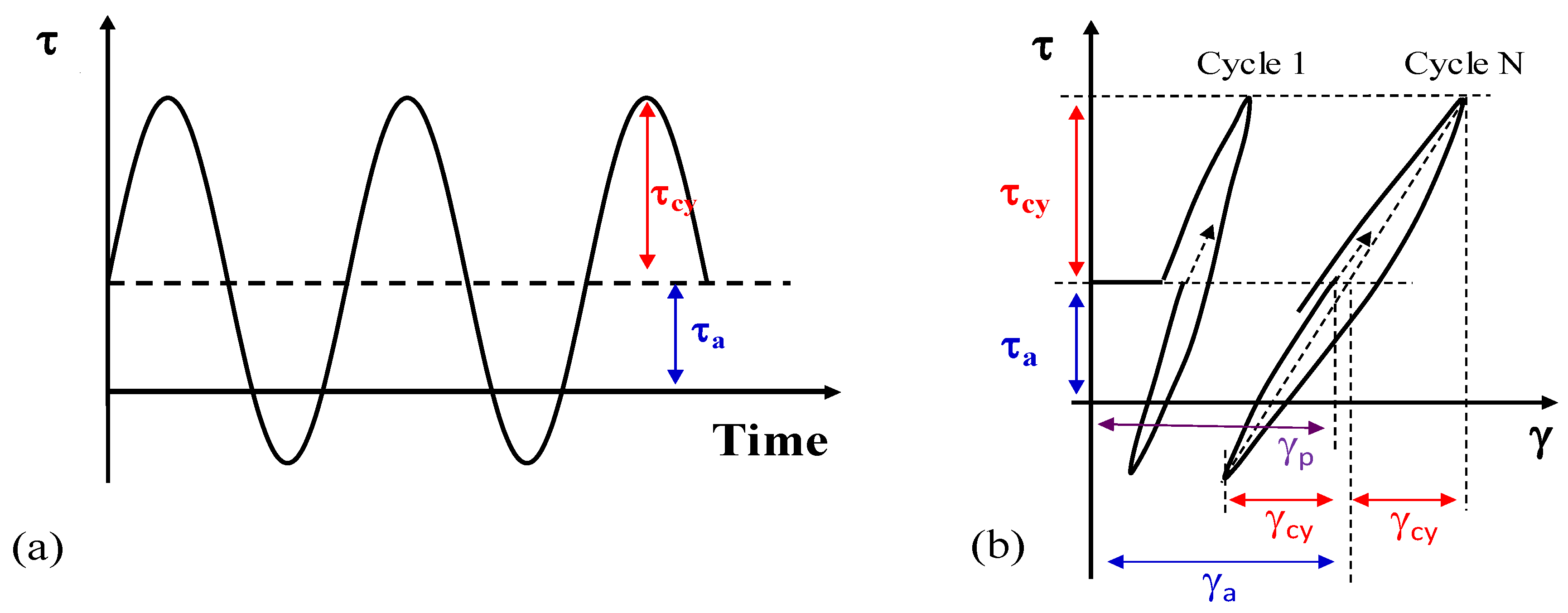

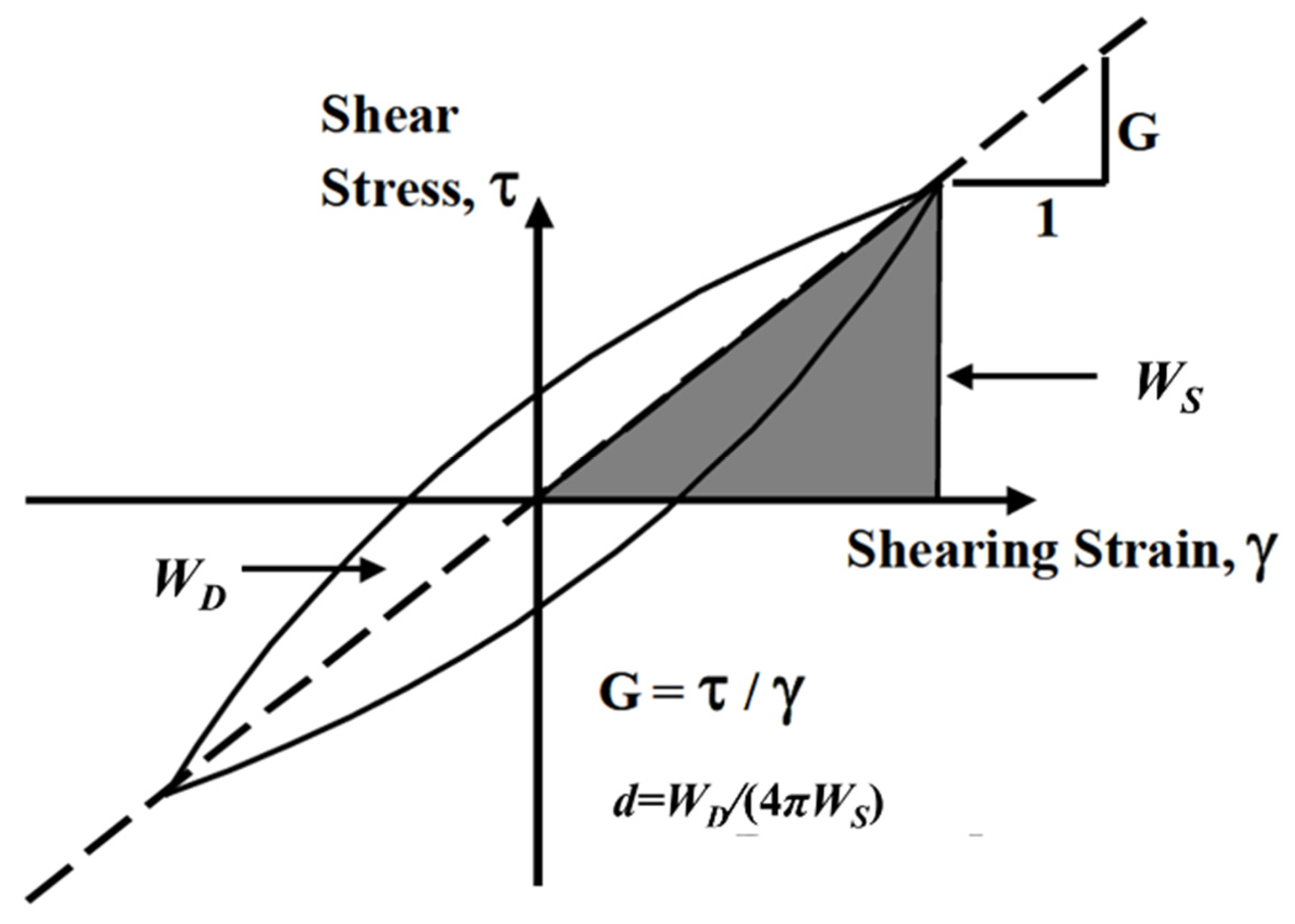

3.1. Damping Ratio Calculation Method

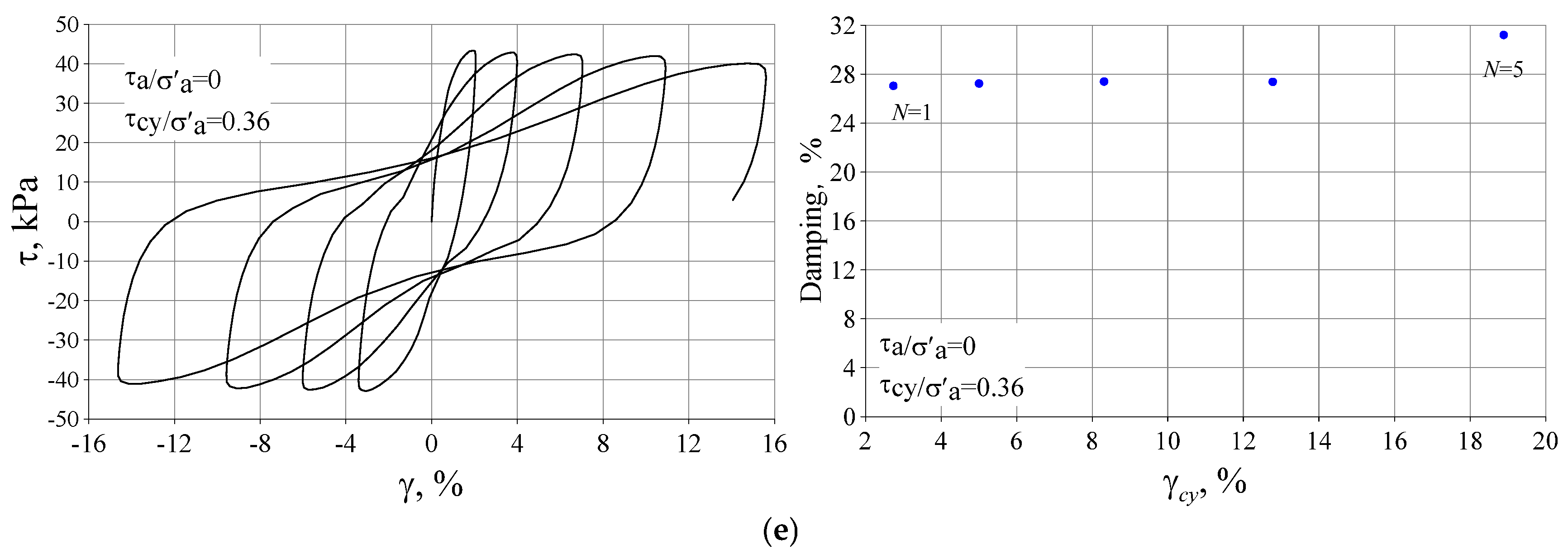

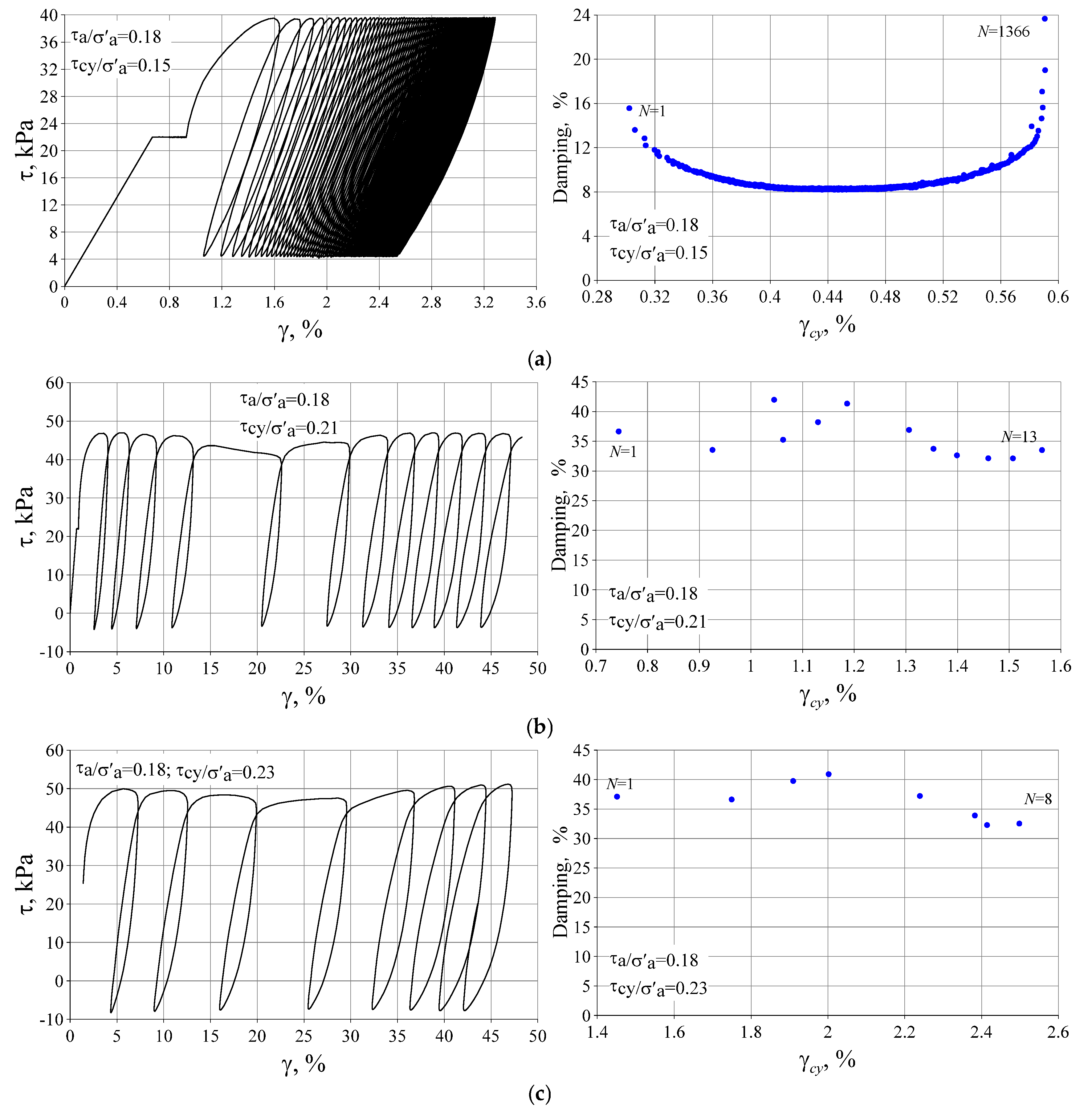

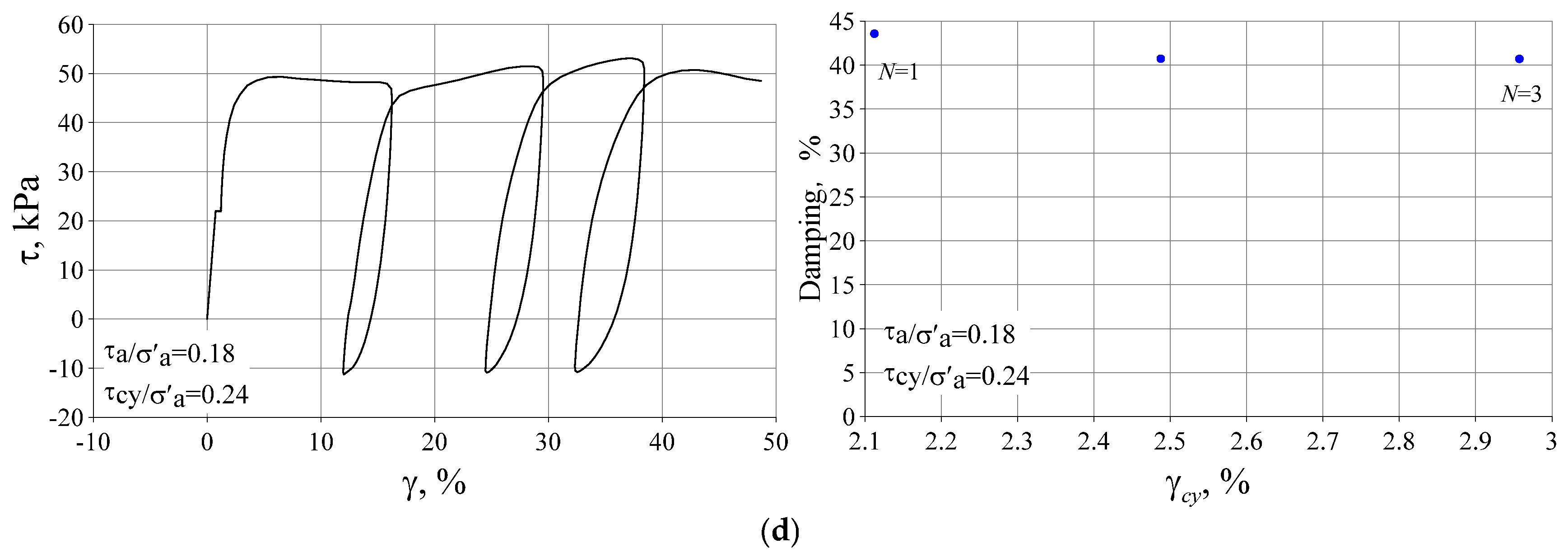

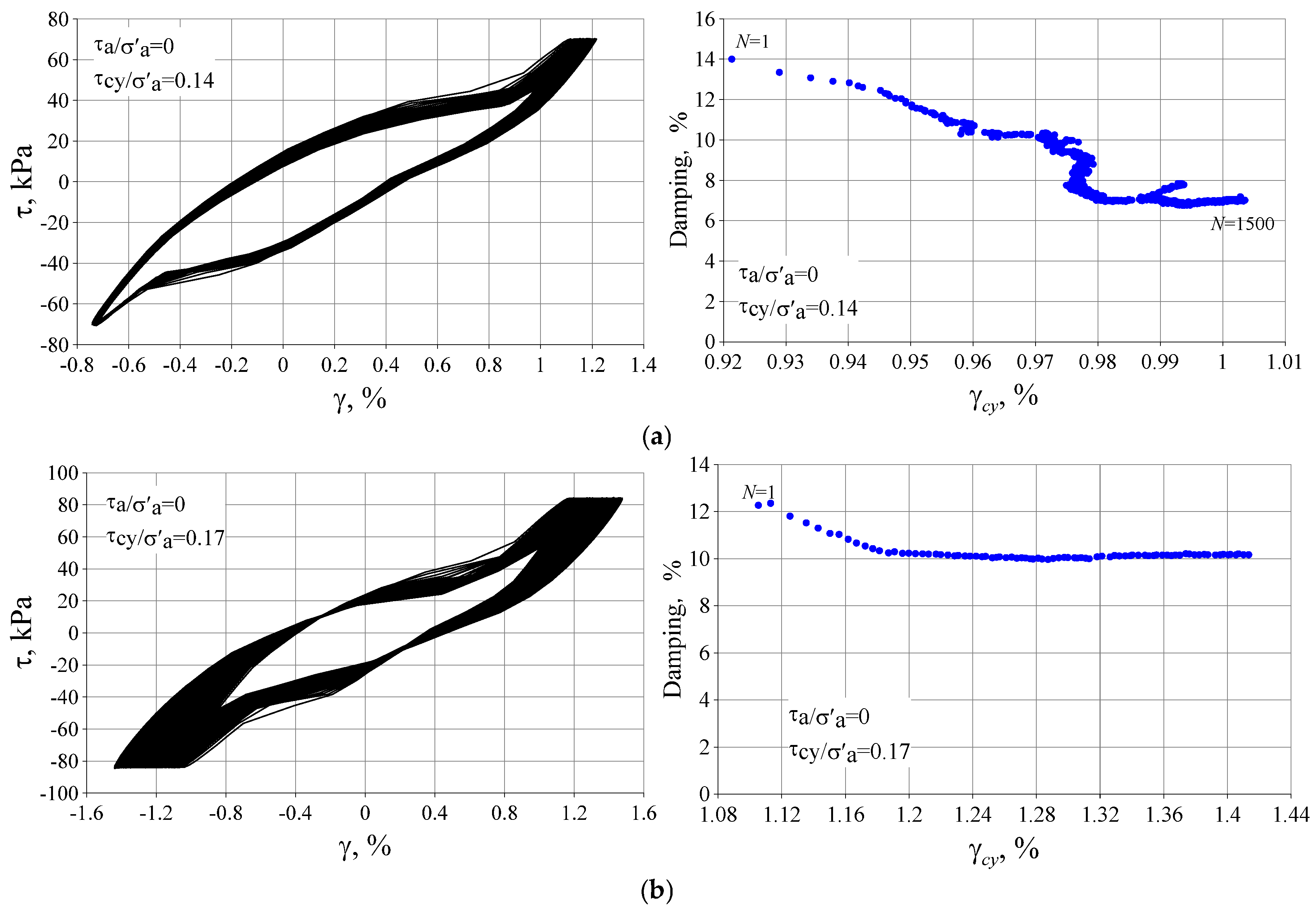

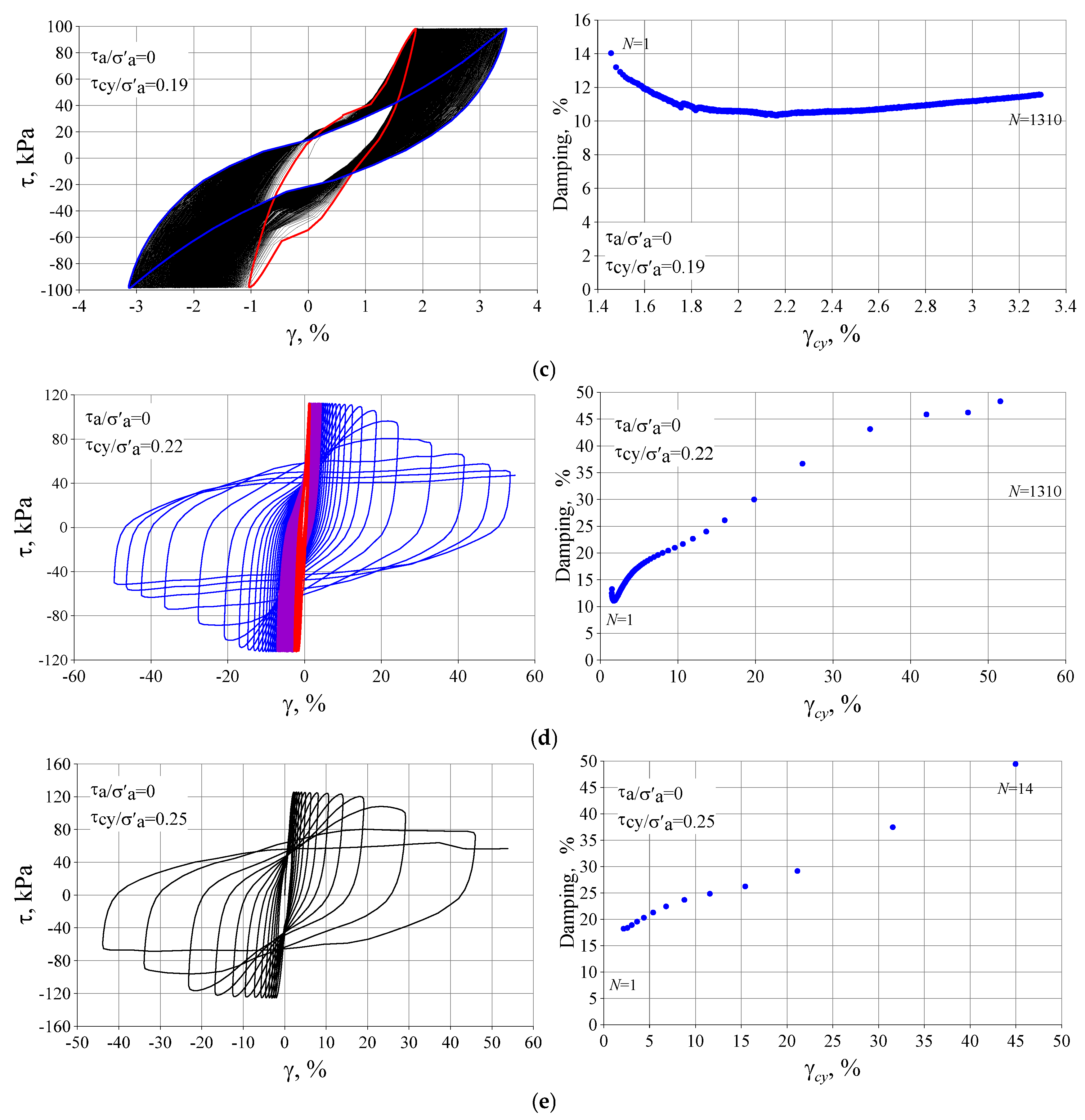

3.2. The Influence of Initial Deviatoric Stress and Cyclic Stress History

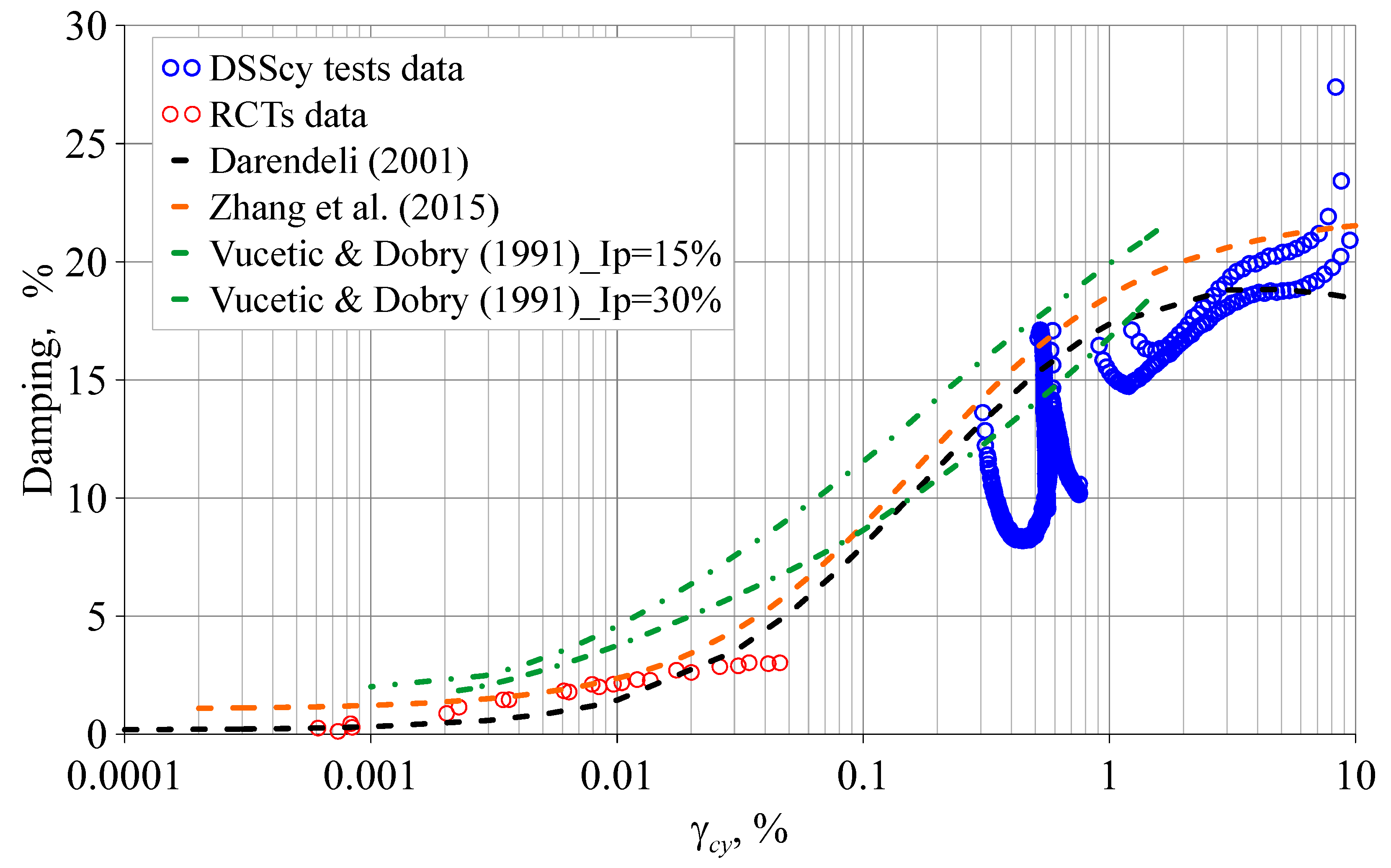

3.3. Damping Ratios of Silty Clay

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Zhang, Y. , Aamodt, K. K. and Kaynia, A. M. Hysteretic damping model for laterally loaded piles. Marine Structures 2021, 76, 102896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assimaki D, Kausel E, Whittle A. Model for dynamic shear modulus and damping for granular soils[J]. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 2000, 126, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineering, E. Dynamic moduli and damping ratios for a soft clay[M]. Journal of Terramechanics 1972, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Inci G, Yesiller N, Kagawa T. Experimental investigation of dynamic response of compacted clayey soils[J]. Geotechnical Testing Journal 2003, 26, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee S, Balaji P. Springer International Publishing, 2018. Effect of Anisotropy on Cyclic Properties of Chennai Marine Clay[J]. International Journal of Geosynthetics and Ground Engineering 2018, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mojezi M, Biglari M, Jafari M K, Ashayeri I. Taylor & Francis, 2020. Determination of shear modulus and damping ratio of normally consolidated unsaturated kaolin[J]. International Journal of Geotechnical Engineering 2020, 14, 264–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Yamanashi T, Hashimoto H, Yamaki M. Springer International Publishing, 2018. Shear Modulus and Damping Ratio for Normally Consolidated Peat and Organic Clay in Hokkaido Area[J]. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering 2018, 36, 3159–3171. [Google Scholar]

- Azeddine Chehat, Mahmoud N. Hussien M A. Stiffness–and damping–strain curves of sensitive Champlain clays through experimental and analytical approaches[J]. Canadian Geotechnical Journal Stiffness-and 2018, 29, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta T T, Saride S. Dynamic Properties of Compacted Cohesive Soil Based on Resonant Column Studies[J]. International Conference on Geo-Engineering and Climate Change Technologies for Sustainable Environmental Management GCCT-2015 2015, 7–12.

- CAI Yuanqiang, WANG Jun, XU Changjie. Experimental study on dynamic elastic modulus and damping ratio of Xiaoshan saturated soft clay considering initial deviator stress[J]. Rock and Soil Mechanics 2007, 28, 2291–2296. [Google Scholar]

- NIE Yong, FAN Henghui, WANG Zhongni, et al. Influence of cyclic shear direction on static and dynamic characteristics of saturated soft clay[J]. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng 2015, 34, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Leng J, Ye G LIN, Ye B, Jeng D S. Elsevier Ltd., 2017. Laboratory test and empirical model for shear modulus degradation of soft marine clays[J]. Ocean Engineering 2017, 146, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin B O, Drnevich V P. Shear Modulus and Damping in Soils: Measurement and Parameter Effects.[J]. ASCE J Soil Mech Found Div 1972, 98, 603–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallioglou P, Tika T, Pitilakis K. Shear modulus and damping ratio of cohesive soils[J]. Journal of Earthquake Engineering 2008, 12, 879–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darendeli M, B. Development of a New Family of Normalized Modulus Reduction and Material Damping Curves[D].

- Zhang J, Andrus R D, Juang C H. Normalized shear modulus and material damping ratio relationships[J]. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 2005, 131, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senetakis K, Payan M. Elsevier Ltd., 2018. Small strain damping ratio of sands and silty sands subjected to flexural and torsional resonant column excitation[J]. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2018, 114, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee C J, Sheu S F. The stiffness degradation and damping ratio evolution of Taipei Silty Clay under cyclic straining[J]. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2007, 27, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Wang B, Liu J. Dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio of recently deposited soils in coastal areas of Jiangsu Province[R]. 2008.

- Lan J, Liu H, Lyu Y. Dynamic nonlinear parameters of soil in the Bohai Sea and their rationality[R].

- Li Y, Li P, Zhu S. Taylor and Francis Ltd., 2022. The study on dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio of marine soils based on dynamic triaxial test[J]. Marine Georesources and Geotechnology 2022, 40, 473–486. [Google Scholar]

- Song Qianjin, ChengLei, He Weimin. Experimental study of the dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio of silty clay on Eastern Henan Plain [J]. China Earthquake Engineering Journal 2020, 42, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Song Binghui, Sun Yongfu, Song Yupeng, et al. Experimental study on the small-strain dynamic properties of offshore seabed soil in Liaodong Bay [J]. China Earthquake Engineering Journal 2022, 44, 535–541. [Google Scholar]

- H2 Weimin, Li Deqing, Yang Jie, et al. Recent progress in research on dynamic shear modulus, damping ratio, and poisson ratio of soils[J]. China Earthquake Engineering Journal 2016, 38, 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- WANG Jianhua, YANG Teng. Cyclic shear modulus and damping ratio of k0 consolidated saturated clays[J]. Journal of natural disasters 2018, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vucetic M and Dobry, R. Effect of soil plasticity on cyclic response. Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, ASCE 1991, 117, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNV (2021). Offshore soil mechanics and geotechnical engineering. DNV-RP-C212, edition 2019-09, amended 2021-09.

| Soil Layer No. | Depth Range (m) | Natural Moisture Content (%) | Saturated Unit Weight (kN/m3) | Plasticity Index (%) | Sand Content (0.075-2 mm) (%) | Silt Content (0.005-0.075 mm) (%) | Clay Content (< 0.005 mm) (%) |

| L1 | 16-17 | 40.5 | 17.9 | 26.6 | 4.3 | 62.7 | 33 |

| L2 | 17-18 | 38.7 | 18.1 | 20.9 | 7.4 | 72.3 | 20.3 |

| Soil Layer | τa(kPa) | τcy(kPa) | ta/sa’ | tcy/sa’ | sa’(kPa) | OCR | Ntot | Test | |

| 1 | L1 | - | - | - | - | 119 | 2 | - | DSS |

| 2 | L1 | - | - | - | - | 119 | 2 | - | RCA |

| 3 | L1 | 0 | 17.6 | 0 | 0.15 | 119 | 2 | >1500 | DSScy |

| 4 | L1 | 0 | 26.4 | 0 | 0.22 | 119 | 2 | >1500 | DSScy |

| 5 | L1 | 0 | 30.8 | 0 | 0.26 | 119 | 2 | 66 | DSScy |

| 6 | L1 | 0 | 35.2 | 0 | 0.30 | 119 | 2 | 38 | DSScy |

| 7 | L1 | 0 | 43 | 0 | 0.36 | 119 | 2 | 5 | DSScy |

| 8 | L1 | 22 | 17.6 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 119 | 2 | 1366 | DSScy |

| 9 | L1 | 22 | 24.9 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 119 | 2 | 13 | DSScy |

| 10 | L1 | 22 | 27.3 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 119 | 2 | 8 | DSScy |

| 11 | L1 | 22 | 28 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 119 | 2 | 3 | DSScy |

| 12 | L2 | - | - | - | - | 506 | 1 | - | DSS |

| 13 | L2 | - | - | - | - | 506 | 1 | - | RCA |

| 14 | L2 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 0.14 | 506 | 1 | >1500 | DSScy |

| 15 | L2 | 0 | 84 | 0 | 0.17 | 506 | 1 | >1500 | DSScy |

| 16 | L2 | 0 | 98 | 0 | 0.19 | 506 | 1 | 270 | DSScy |

| 17 | L2 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 0.22 | 506 | 1 | 191 | DSScy |

| 18 | L2 | 0 | 126 | 0 | 0.25 | 506 | 1 | 10 | DSScy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).