1. Introduction

Pathological conditions in arteries are crucial for the health of the patient. Common pathological conditions that can be observed are stenotic arteries and aneurysms. The simulations utilizing Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) are the most reliable solution for evaluating the patient’s condition through flow parameters such as velocity, pressure, stresses at the wall and more advanced biomedical parameters.

In the cardiovascular system, bifurcation regions are present, with the abdominal aortic bifurcation being of great interest, as it is the largest bifurcated artery in our body. Fluid mechanics contributes to flow analysis and provides crucial information that must be assessed individually for each case. Geometric parameters of the artery, hemodynamic factors and boundary pulsatility, significantly influence the stenosis progression and its narrowing, leading to pathological conditions for the patient.

Branching networks are essential in the human body and have been extensively studied. Pedlay et al. have examined such networks of branching tubes with varying geometry [

1]. Pradham and Guha presented a 3D parametric study in a bifurcation [

2]. Wilde et al. studied several shear stress factors in the carotid bifurcation of mouse-specific FSI (Fluid Structure Interaction) cases [

3]. Furthermore, Lewandowska et al. conducted a comparative study on different carotid bifurcation angles [

4]. Additionally, Ahmed and Podder explore how diseases, such as anemia and diabetes, influence fluid dynamic parameters [

5]. Finally, Garcia et al. analyze local hemodynamic changes in a coronary bifurcation caused by three different stenting techniques [

6], while Younis et al. apply an FSI approach based on the finite element method to investigate hemodynamic flow parameters [

7].

The evolution of vortices and secondary motion including Dean and anti-Dean type structures is analyzed in [

12]. The flow dynamics in multiple generations, with multiple branches, is investigated by many researchers [

13,

14,

15,

16] and is of great interest as it represents the complex structure of many human body organs.

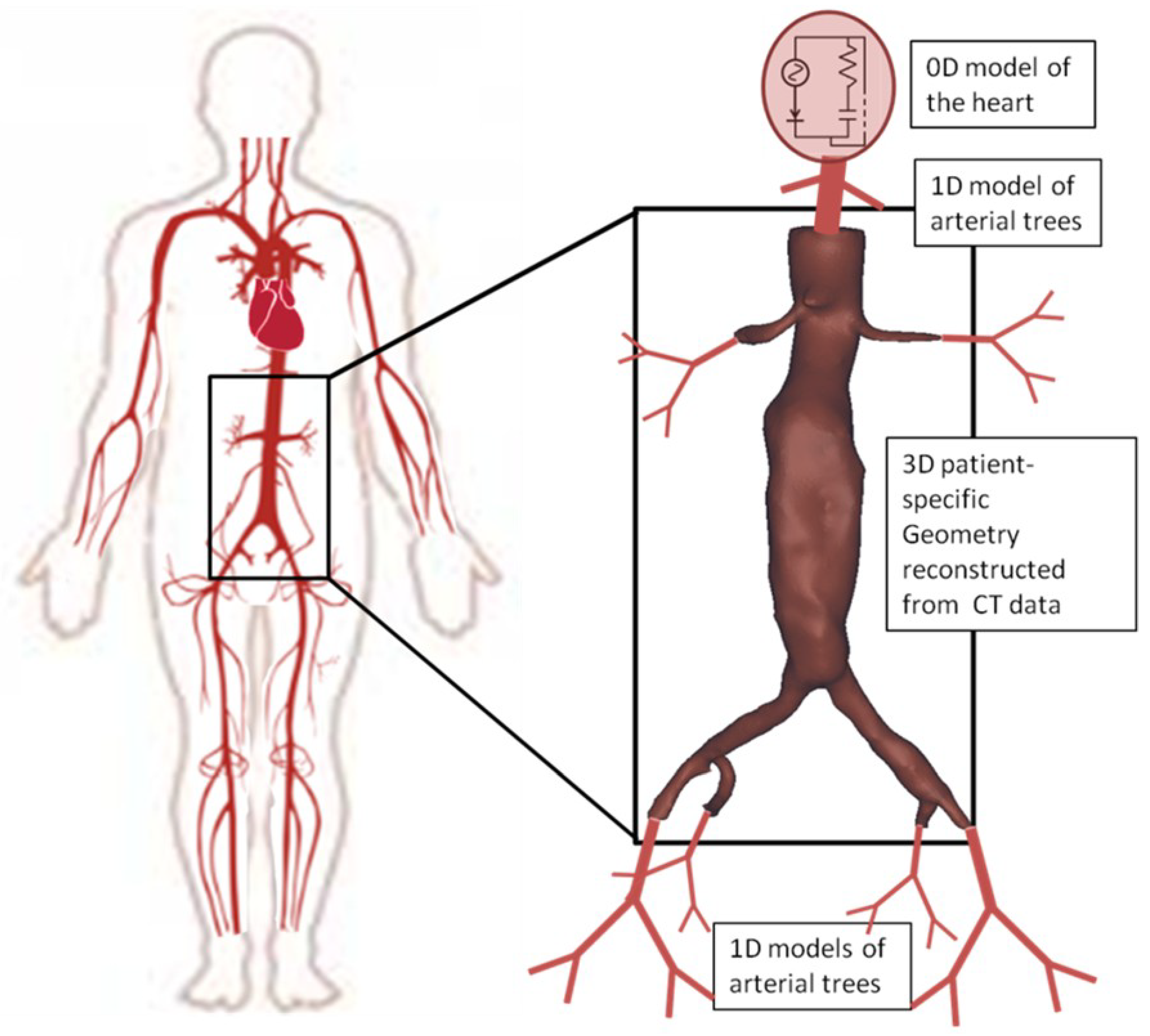

Additionally, mathematical modeling of blood flow in systemic arteries is of great interest due to its significance in human health. In this study, we employ an advanced mathematical model for monitoring pressure and flow profiles at specific locations, as these profiles are vital for the final behavior of blood flow in the abdominal aorta. This 0D-1D model predicts the flow and pressure at any given time in the systemic arteries of interest. Blood is treated as an incompressible Newtonian fluid, while vessels are assumed to be elastic. To ensure a reliable numerical solution, the model is divided into the first part (1D), that includes the large arteries and the second one which includes the smaller arteries (0D) [

19]. For the smaller arteries, a Windkessel mathematical model is used as described in [

19]. For the larger arteries, Navier-Stokes, continuity and arterial wall motion equations are solved as a coupled system of equations. The solution of the system of equations (0D-1D) for the entire arterial tree provides with the boundary conditions that are applied in the 3D problem that is described by the three-dimensional Navier-Stokes equations.

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is a reliable alternative to open surgery, but commercial endografts are not dedicated to all thoracic and abdominal aortic anatomies. The scope of this study is to compare the properties of blood flow at the splanchnic (secondary) vessels after F/BEVAR stent designs.

Fenestrated devices are made with the reference to patient’s unique anatomy. Fenestrated grafts include small openings that allow the restoration of blood flow to the arteries branching from the aorta, which deliver blood to essential organs such as the kidneys, bowel, and liver. Fenestrated stent grafts use the healthier part of the abdominal aorta as a landing zone and are deployed under fluoroscopic guidance. Their fenestrations are connected to the target vessels with flared stent grafts for secure blood flow.

Branched devices are endografts that have specific branches for the main target vessels. The branches have downward direction and are useful for the treatment of complex, mostly thoracoabdominal, aneurysms. They are used in case of suprarenal aneurysms with or without the presence of angulation.

The selection of the stent device depends on the unique anatomy of the patient’s aorta and until now, there is not optimal combination of B/FEVAR. The impact of each device on blood flow, as influenced by the respective stent, must be considered when selecting between the two options.

The study of hemodynamic parameters and the significant changes of different endograft designs have been studied through CFD [

17,

18,

19]. Visceral arteries may have a vital role in the mathematical modeling and could create small flow perturbations that generally affect the patient’s health. Changes in important hemodynamic parameters between preoperative and postoperative FEVAR cases have been evaluated via CFD, resulting in all hemodynamic characteristics converging to normal after repair [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Regarding the effectiveness of BEVAR many studies have been conducted on their postoperative impact and the reasons for their long-term effects [

17,

20,

22,

23,

24,

25].

In this study, both two-dimensional (2D) bifurcation flow and 3D patient-specific numerical solutions are presented. For the two-dimensional case the solution is acquired via the use of the Finite Volume Method and a Newton-like algorithm. Levenberg-Marquardt is utilized to solve the non-linear system of PDEs (Navier-Stokes and Continuity equations), aiming to obtain robust and converged numerical solutions. The main advantage of this method is its reliable solutions to stiff problems, where classic iterative methods may fail to deliver. The pressure and velocity fields are presented in both bifurcated and stenotic bifurcated geometries. The impact of stenosis near a branching network is highlighted through the contours of pressure distribution.

Regarding the multiscale 3D study, the main focus was on the hemodynamic changes in F/BEVAR cases regarding the four visceral (secondary) target vessels. The results are exported through the use of an advanced multiscale mathematical model introduced in [

18,

19]. The two different cases of B/FEVAR are simulated, compared and evaluated. The hemodynamic parameters of interest are exported through CFD simulations. The most significant of these, including wall shear stress (WSS), localized normal helicity (LNH), and time averaged WSS (TAWSS), are presented in this study.

2. Mathematical Formulation

2.1. The 2D Study

The mathematical modeling of the problem is described by the Navier-Stokes and continuity partial differential equations (PDEs) for incompressible flow. The momentum equations of interest are provided in vector form,

where

p is the pressure,

the density and

is the kinematic viscosity. The equations that describe the two-dimensional, steady state and incompressible flow are the system of PDEs that includes

x,

y momentum and the continuity equation. The system of PDEs is provided below in dimensionless form,

Continuity equation, dimensionless

x-momentum equation, dimensionless

y-momentum equation, dimensionless

where

u and

v are the components of the velocity vector,

,

p is the pressure and the Reynolds number is defined as

, where

L is the characteristic length and

is the maximum value of the parabolic velocity applied at the inlet.

Numerical solution. The studied problem is discretized under Finite Volume Method, a second-order discretization method. The acquired algebraic system is strongly non-linear and the domain of interest is divided into a finite number of control volumes. By integrating the governing equations over every control volume, the final algebraic system of equations is obtained. The system of algebraic equations for the two-dimensional case consists of three dimensionless equations for each control volume, the two momentum equations in addition to the continuity equation that are provided below,

Continuity equation, dimensionless

x-momentum equation, dimensionless

y-momentum equation, dimensionless

Where and are the dimensions of the control volume and and N are the East, West, Centroid, South and the North points of each control volume.

For the final numerical solution, which contains the

and

p values in every volume of the computational domain, we use a Newton-like method, specifically the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. Newton-like methods use the Jacobian matrix of residual functions

that corresponds to the equations (

5)-(

7) equal to zero. The derivatives of the functions are obtained with respect to the known variables

. The calculation of the Jacobian matrix can be computationally expensive and the solutions that we propose lie in the sparsity of this matrix. With this solution, the algorithm applies only to the non-zero elements of the matrix. This is a common technique in Newton-like methods as the number of zeros is exponentially increasing as the number of grid points is getting larger. A large-scale problem, such as the one that we are approaching, needs to be adjusted, aiming to be optimal regarding computational memory and time consumption.

The main difference of this approach compared to other common CFD solvers such as PISO and variations of SIMPLE is that we are working in a collocated grid in which we are solving the raw Navier-Stokes equations coupled, without any change or any addition of equations like pressure correction equations. The numerical convergence criterion has been set to a very small number

The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm is chosen for this problem due to the robustness that it provides. The mathematical scope of this method lies in the Newton-like methods, which use trust-region frameworks. For spherical trust-regions, the subproblems to be solved are described in equation (

8).

where

is the step direction in the parameter space, which we are trying to determine,

is the Jacobian matrix of the residual function evaluated at the current iteration

k, and

is the residual vector at iteration

k. The

is defined as the radius of trust region and

is the Euclidean norm. Thus, the trust-region approach requires to solve a sequence of subproblems [

11]. Finally, we obtain the optimal field of parameter

which in our problem corresponds to the velocity components

and pressure

p.

2.2. The 3D Study

The problem under consideration is governed by the unsteady and incompressible Navier-Stokes, equations (

1), and the continuity equation.

The 1D mathematical model that is utilized predicts the blood flow and pressure in all systemic arteries of the arterial tree and the 3D Navier-Stokes numerical solution is obtained to evaluate the post-endovascular F/BEVAR cases. For this work the post-endovascular aneurysms are constructed from computed tomography scans of patients treated with custom-made fenestrated and branched endografts. The cases presented are from patients who suffered from AAA and had a patient-specific stent graft system implanted at the General University Hospital of Larissa, Thessaly, Greece. The patients received custom-made fenestrated devices, with configurations including fenestrations for renal arteries, scallops for the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and, in some cases, an additional scallop for the celiac axis. Balloon-expandable bridging stent-grafts were implanted in all target vessels. The processed imaging data were totally anonymised, thus no ethics committee approval was necessary.

The 0D-1D model consists of a system of elastic cylindrical tubes that mathematically representing blood flow across an extended portion of the arterial system. These tubes are interconnected, meaning the outflow from one segment serves as the inflow for the next, with appropriate conditions applied at bifurcations [

32,

33]. The model incorporates initial conditions by introducing pressure and flow waveforms in the ascending aorta. At the outlet of the 1D arterial tree we apply more simplistic 0D-Windkesel models. The 0D-1D mathematical model predict the volumetric flow (

q), pressure (

p), and cross-sectional area (

A) for each vessel of the arterial tree.

where

E is the Young’s modulus. At the inlet of the 3D aorta a dynamic parabolic profile is enforced. Thus, spatially a parabolic profile that is changed at each time step based on a waveform obtained from the coupling of 0D-1D mathematical model is applied.

More specifically, the boundary conditions of the in-study problem are determined by the use of 0D-1D mathematical model, which results in the inlet/outlet waveforms in each artery of the 3D reconstructed model [

18], as depicted in

Figure 1. At the inlet of the 3D mathematical model, we applied parabolic waveforms obtained from the 1D mathematical model, representing healthy characteristics. Additionally, the pressure waveforms at the outlets of the 3D model derived from the developed 1D mathematical model. The velocity profile at the outlets was described in literature as almost parabolic during the systolic phase [

18,

19,

26,

27,

28]. No-slip condition was applied to the wall in all studied 3D cases.

The quantity Time Averaged Wall Shear Stress (TAWSS) is defined as the average value of the magnitude of Wall Shear Stress (WSS) vector along the cardiac cycle,

where

T is the duration of the cardiac cycle and

s is the general surface coordinate.

Helicity,

, is an index that quantifies the interplay between rotational and translational motion of blood i.e. has influence on the development of helical structures in the fluid domain. It is defined as follows,

where

is the velocity vector,

is the vorticity vector and

V the fluid domain. Additionally, the rotational structures are visualized through the Local Normalized Helicity (LNH) parameter [

27,

35,

36].

where

is the velocity and vorticity vectors angle.

LNH hemodynamic parameter as a function of space and time, is an indicator of the helical structures’ intensity and their rotational direction [

35,

37,

38]. When the absolute value of LNH is one, the flow is purely helical. Otherwise, when the value is zero, the flow is symmetric. The sign is of great importance as it dictates the right (+) or left-handed(-) direction of helical structures directionality. Therefore, LNH values range between -1 and 1 as discussed in [

18].

Model reconstruction and numerical solution. The 3D model of the fenestrated stent-graft system that includes the renal, superior mesenteric, celiac axis and renal arteries, was constructed using the computed tomography scan of the treated patient. Aiming to obtain the numerical solution, a procedure from the computed tomography scan to its transfer to the computing system must be followed. The image processing and reconstruction software, Mimics (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) was used for the reconstruction of the DICOM images into a 3D model. The aneurysmal sac was not taken into account in the reconstructed mathematical model [

30,

31]. An additional smoothing study was performed in Vascular Modeling Toolkit (VMTK) which led to an optimized smoothing factor of

. The computational grid of the reconstructed geometry was created with tetrahedral elements in the ICEM (Ansys Inc., Canonsburg, PA) CFD software package.

The simulation has been set with

the kinematic viscosity, and

, the blood density. The computational domain has a total of more than two million tetrahedral elements. To adequately study this problem we performed three cardiac cycles. A small computational error of

was set as a stopping criterion and we present the results of the final cardiac cycle avoiding any dynamic behavior of the first pulses [

29]. A mesh sensitivity test was conducted in areas of predicted disturbed flow, we obtained an optimal grid, choosing it regarding an error of less than

in hemodynamic parameters. All 3D model simulations were performed using Fluent (Ansys Inc., Canonsburg, PA). The model ensures high-resolution analytics, including Time Averaged Wall Shear Stress (TAWSS) and Local Normalized Helicity (LNH).

3. Results

3.1. Two-Dimensional Bifurcation Results

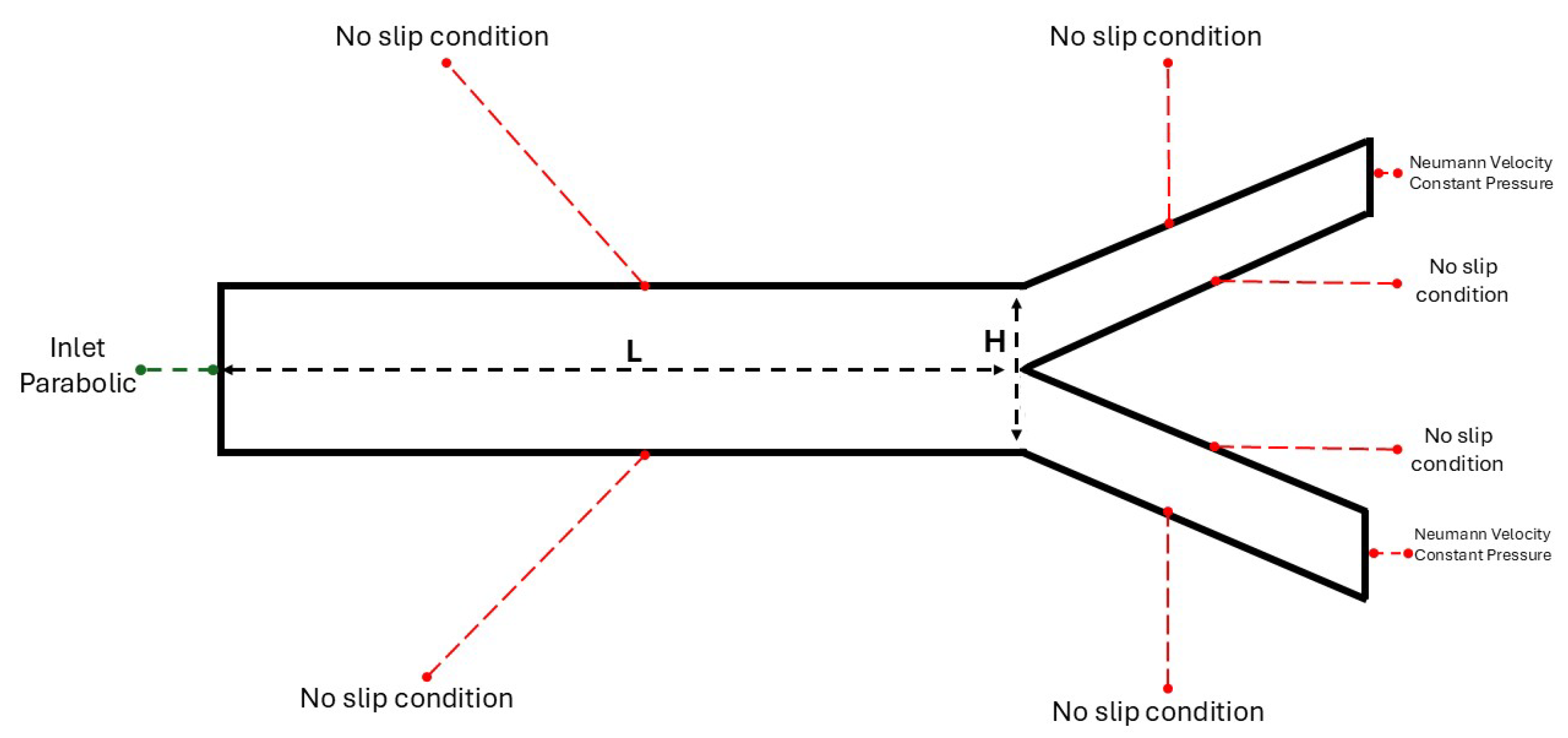

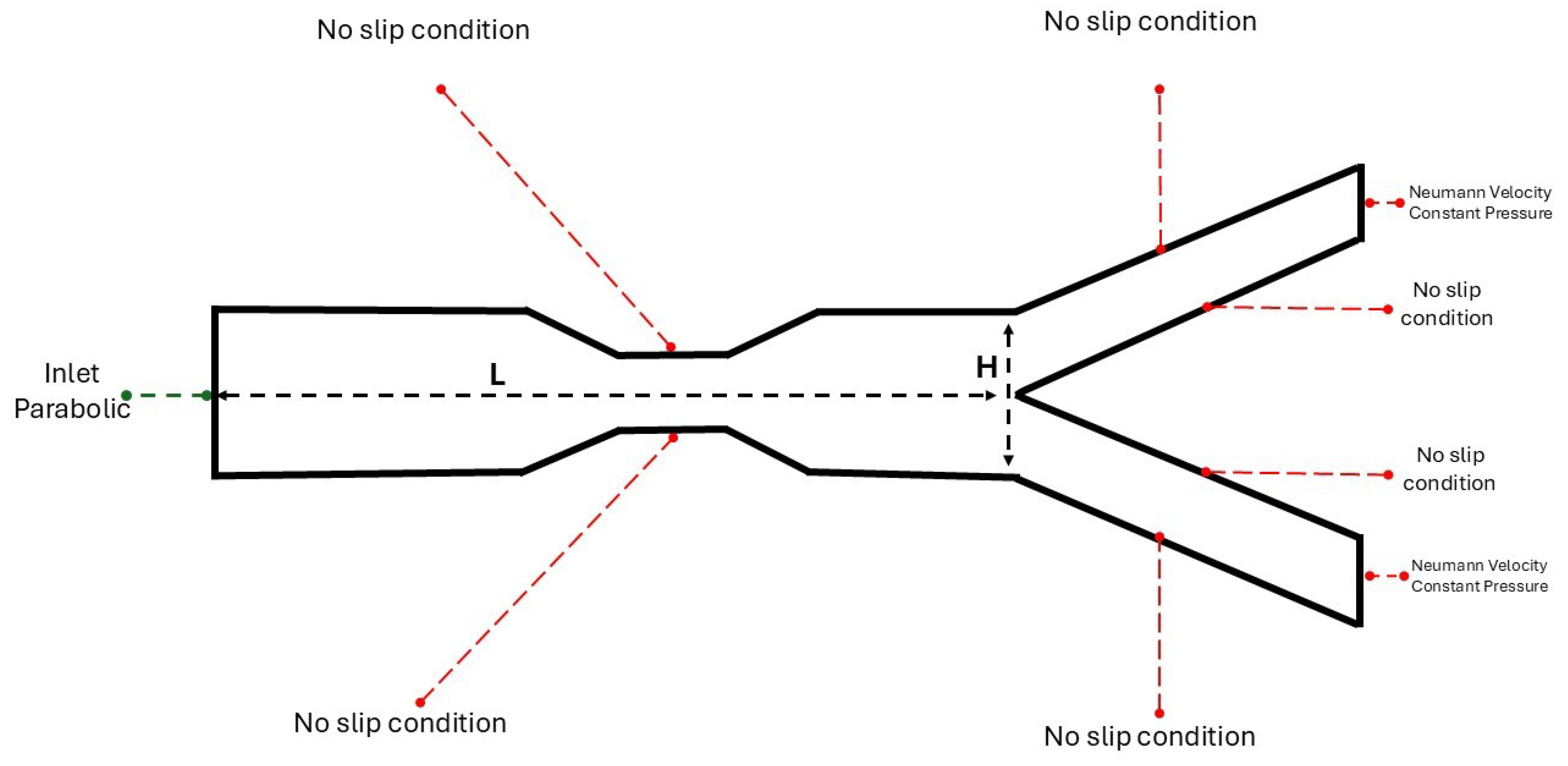

The bifurcation geometry consists of a channel that leads to a division into two smaller and equal in diameter channels, also referred to as mother and daughters arteries. This simplification is aiming in understanding further the flow mechanisms that arise from the branching network. In the last section of this study, a patient specific analysis will be conducted, where the conditions are not ideal and the geometry is not characterized as symmetric.

The computational domain is a rectangle with a length of

and a height of

dimensionless units. As depicted in

Figure 2 the artery has a height of

and length of

dimensionless units. Additionally, they are presented with the boundary conditions that are applied in the solid boundaries, in which the no-slip condition applies. A collocated grid has been constructed with rectangles cells. The angle of daughters arteries is defined as,

. The rectangle grid has a size of

. A mesh sensitivity study has been conducted, for both bifurcation/stenotic bifurcation. In this study an error smaller than

has been achieved for larger grids such as

. So, we chose the

grid size to achieve optimal results in terms of accuracy and computational time.

The numerical solution obtained with the use of Matlab(MathWorks Inc.) has converged with the aid of the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm which suggests a powerful tool in the solving of the strongly non-linear system of equations. It is widely used in problems that utilize the coupling of Finite Volumes Method with Newton-like algorithms for pathological conditions such as aneurysmal geometries [

8,

9,

10].

The boundary conditions for the problems under consideration are,

These boundary conditions coupled with the system of equations (

2)-(

4) provide the numerical solution, for

u,

v-velocity components and pressure

p.

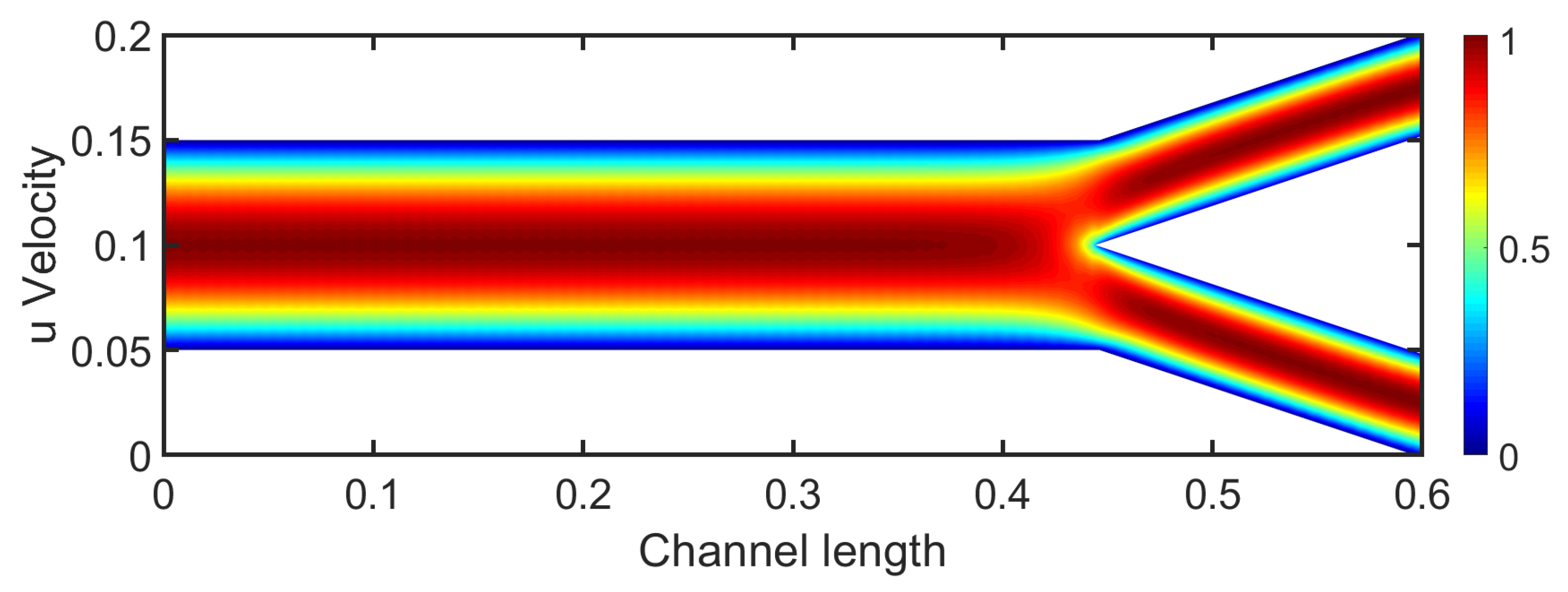

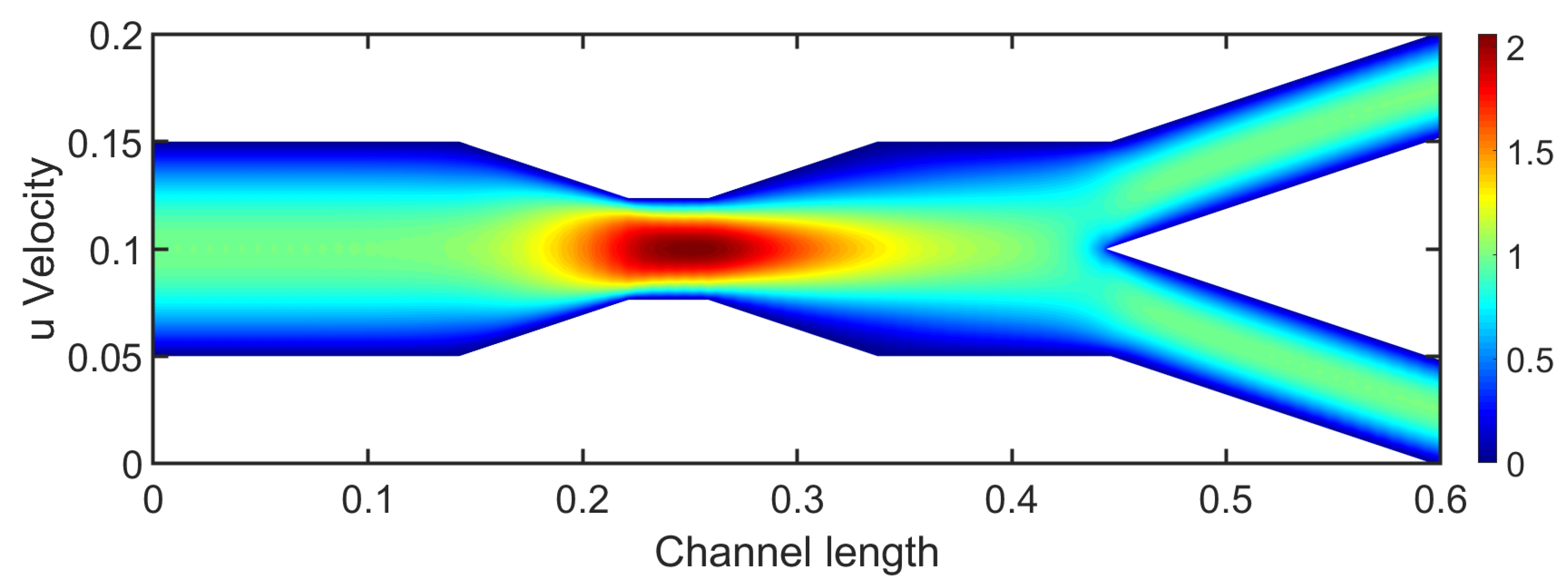

Results in bifurcation. The bifurcation flow presents a velocity field of great interest. Both velocity and pressure fields are crucial for studying patient’s health and the development of pathological conditions. Blood flow in arteries is inherently pulsatile. However, due to the steady-state approach used in this study, a constant parabolic velocity profile is applied at the inlet. The chosen Reynolds number is 400, which approximately corresponds to the mean blood flow value between the systolic and diastolic phases.

In the channel section, the velocity profile remains parabolic, indicating a fully developed laminar flow similar to Poiseuille flow. Right after the channel, the bifurcation divides into two daughter arteries with the same diameter. The flow near the bifurcation decreases and the two daughter branches receive symmetric flow. The flow in daughter arteries near the stagnation point presents small boundary layer thickness in comparison with the upper wall’s boundary layer, as depicted in

Figure 3. The flow gradually becomes fully developed and the velocity profile at the end of each branch is characterized as parabolic. As the

increases, we observe smaller boundary layer thickness at the walls due to the increased momentum.

The contours of the u-velocity component do not present strong separation regions that could potentially lead to vortex creation. Higher angles between the daughter arteries could lead to recirculation zones. The narrowing in geometry suggests shear stress differences that could influence the arterial wall.

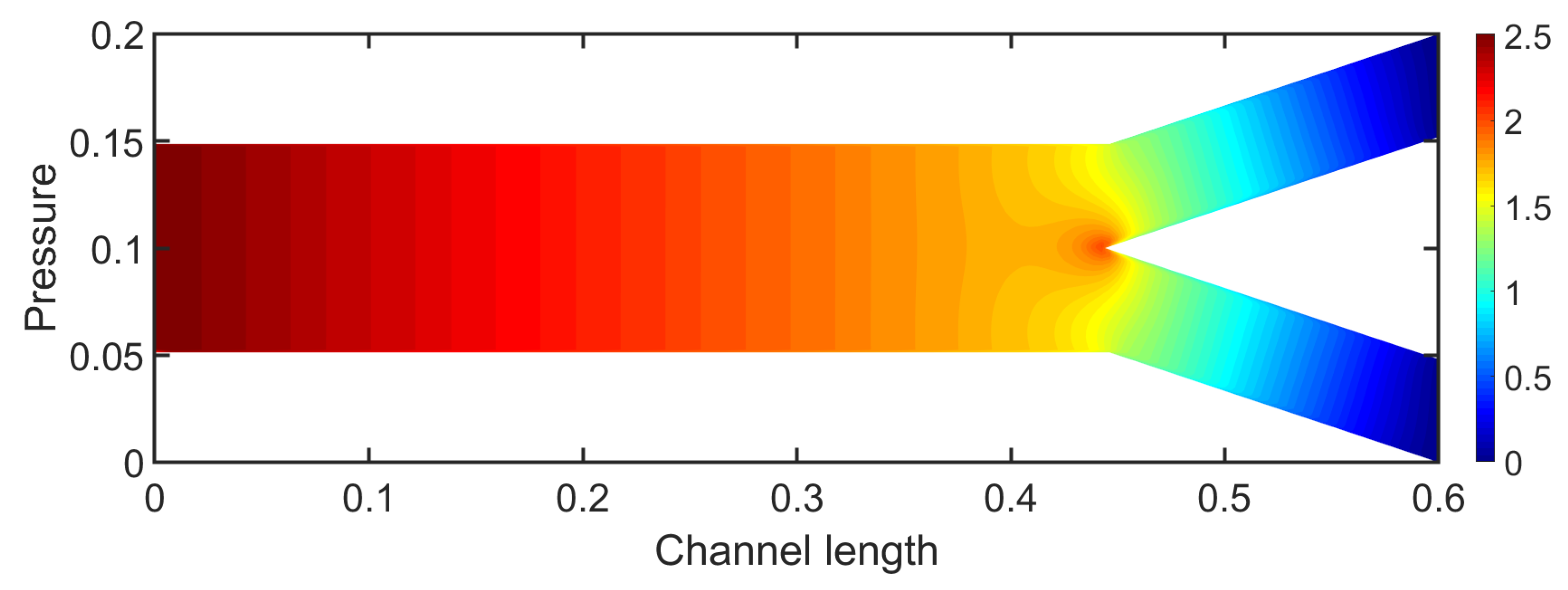

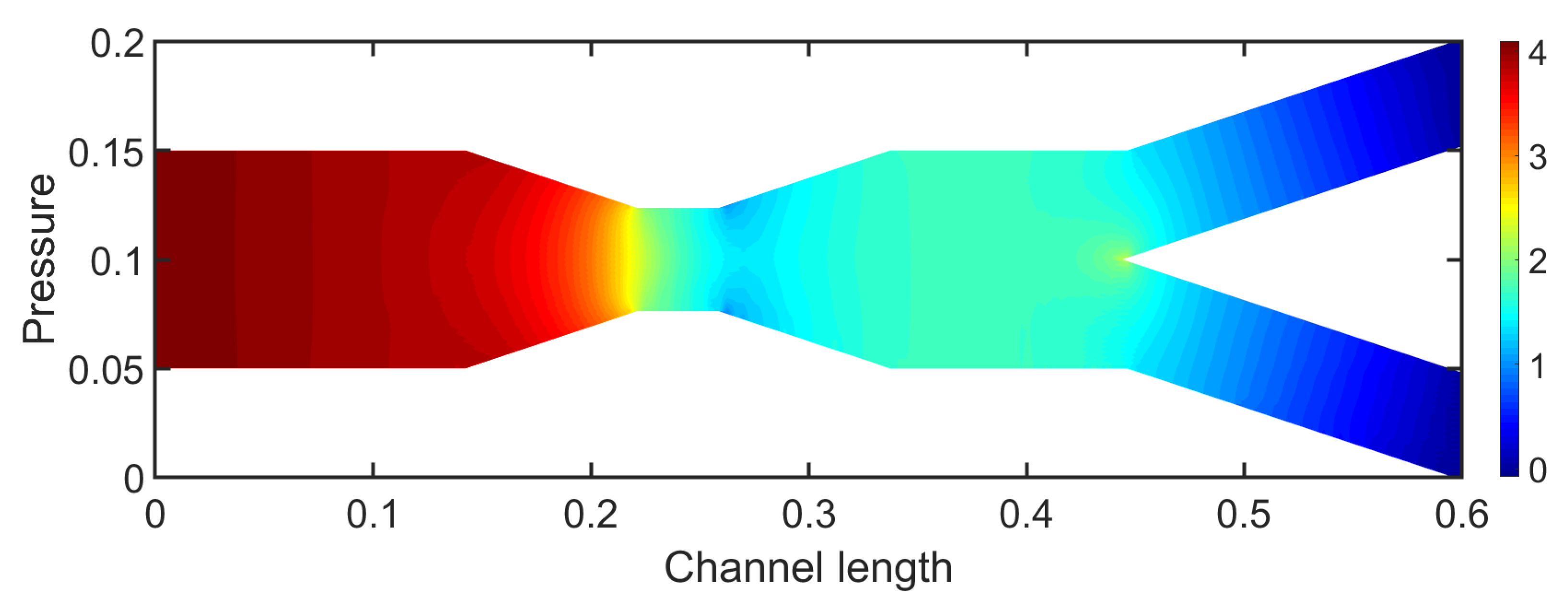

In

Figure 4, the contours of the pressure field of the bifurcation are depicted. The pressure presents a gradual decrease similar to fully developed flow in a channel, until the area of bifurcation. The highest values of pressure are observed at the inlet of the channel. At the bifurcation the pressure exhibits an increase due to the stagnation point. In daughter branches, the pressure continues to decrease to reach a constant value at the outlet.

Another crucial parameter for biomedical flows is the Wall Shear Stresses (WSS), given as the product of the viscosity with the velocity gradient near the wall,

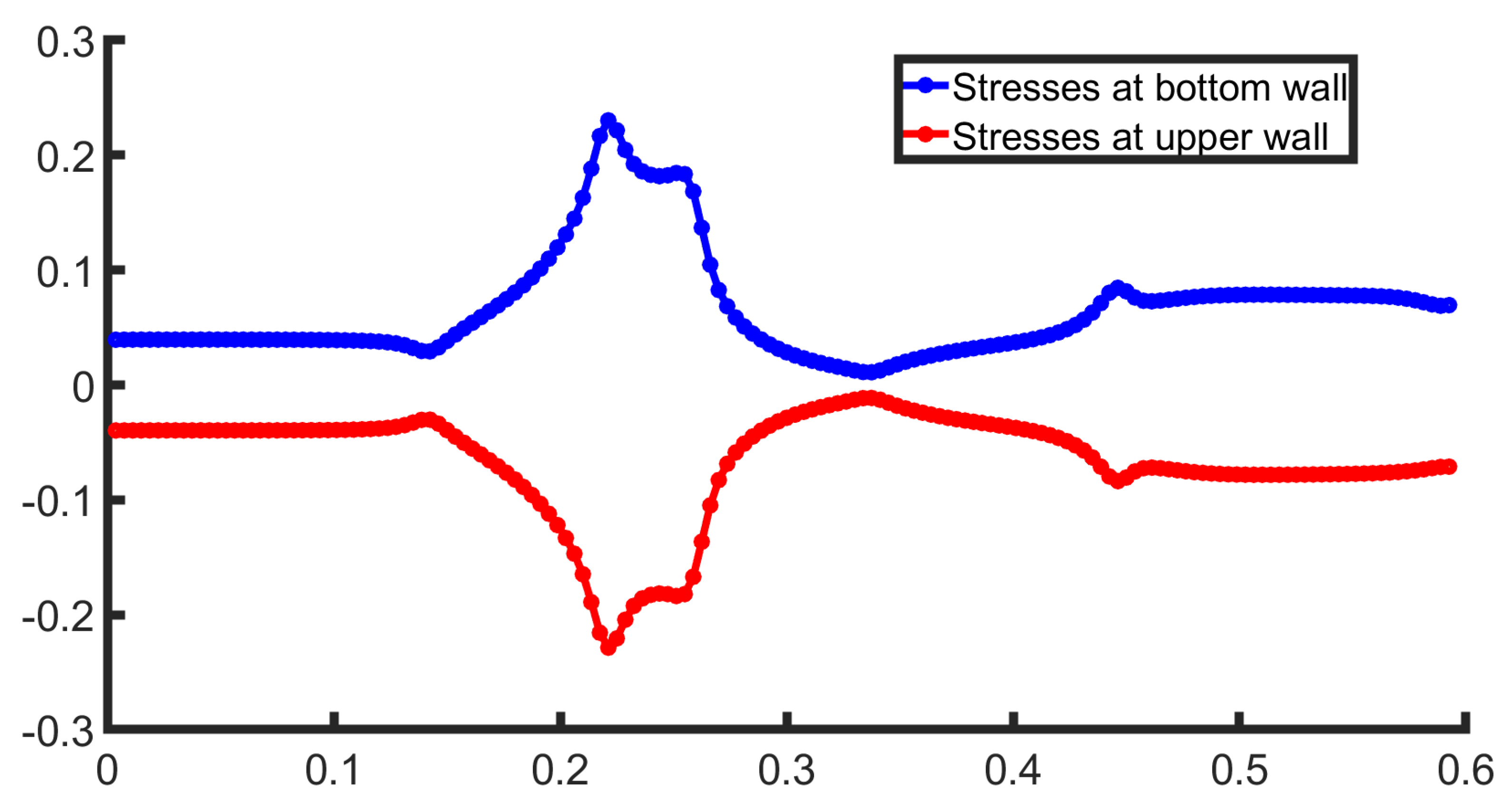

. In

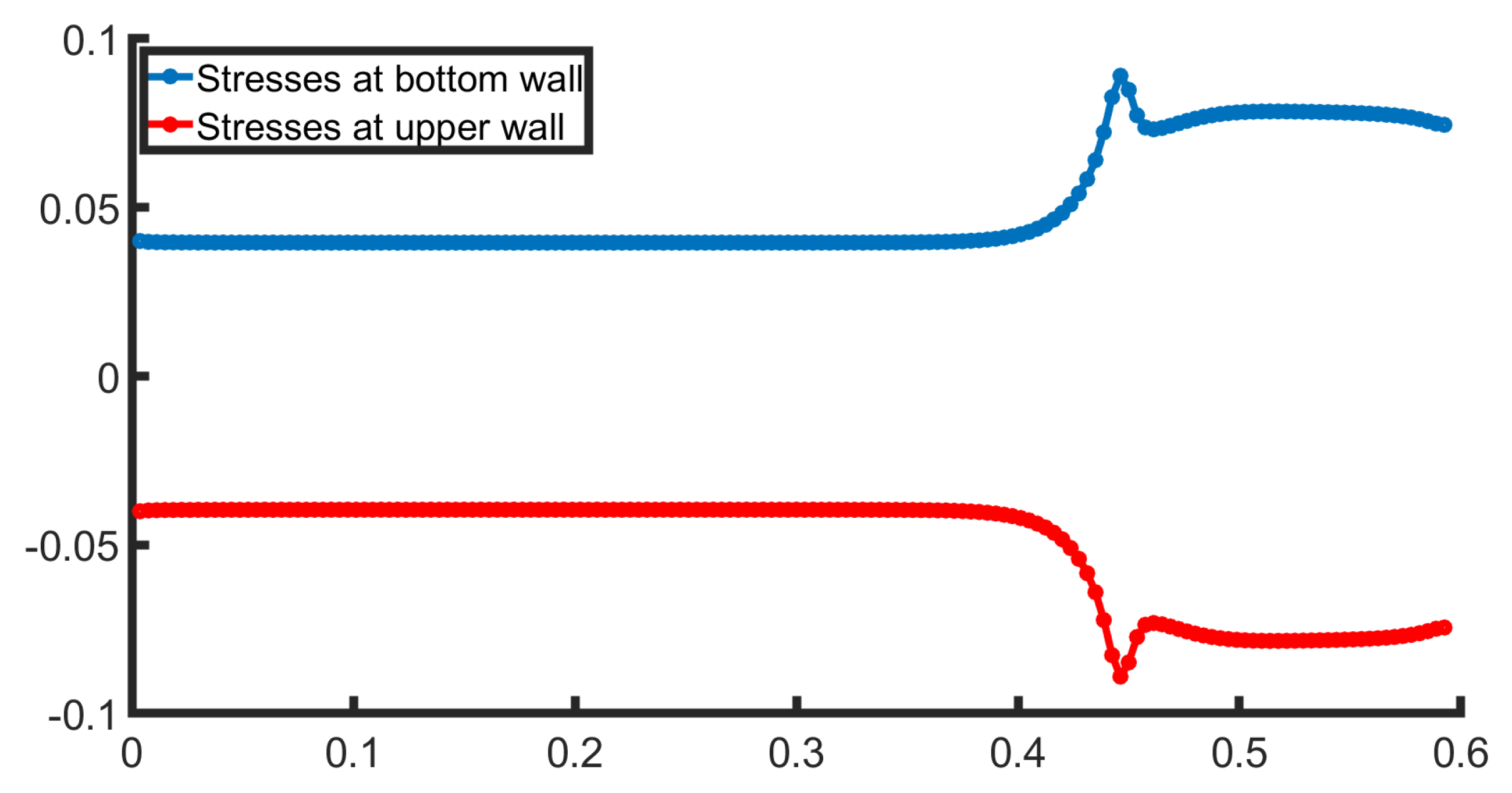

Figure 5, the stresses at both walls are presented. The behavior is symmetrical, as the bifurcation geometry is symmetric. The stresses remain constant in the channel section as the flow is fully developed. Right after this the WSS increase, for the bottom wall as it crosses the bifurcation and flows into the lower daughter artery. This suggests that fluid velocity near the bottom wall accelerates due to the narrowing of the channel, forces the fluid to adjust, leading to a higher velocity gradient. The upper wall behaves identically to the bottom wall, with a different sign.

Results in Stenotic Bifurcation. In the case of a stenotic bifurcation, a stenosis is introduced close to the flow bifurcation to obtain the vital changes that possibly affect the hemodynamic parameters. The geometric parameters are identical to this of bifurcation in previous subsection, with the addition of a

stenosis of the artery, depicted in

Figure 6. In this figure the boundary conditions are described in equation (

15).

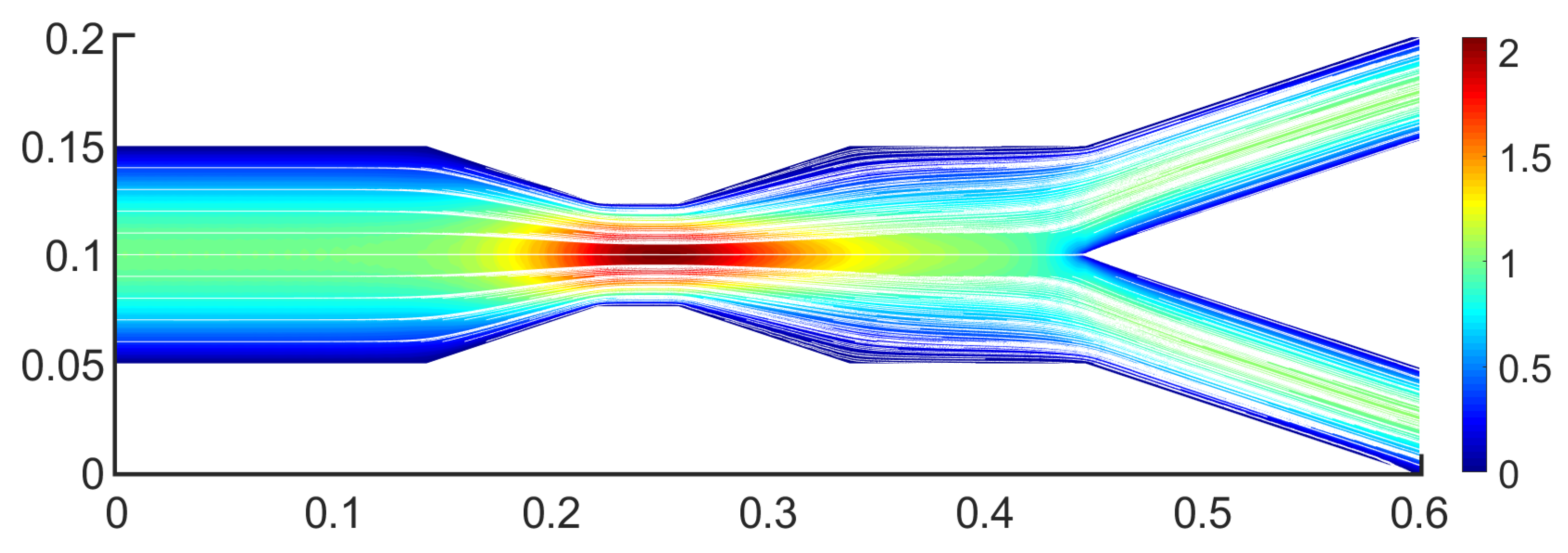

The stenosis impact is visible in

Figure 7, in which it is presented the

u-velocity component. Stenosis drastically affects the flow behavior as the highest velocity is observed in it. The maximum velocity value increased at almost

and the flow reaches the value of 2. The overall behavior outside the stenosis is similar to this of a bifurcation. Upstream of the stenosis, the flow presents a typical fully developed laminar flow with a parabolic velocity profile. However, downstream the stenosis the bifurcation is affected by the stenotic region, revealing an altered flow field from before.

Figure 8 presents the pressure field for

. Initially, upstream the stenosis the pressure exhibits a decrease that almost resembles a typical channel flow until the region of stenosis. In the stenosis pressure presents a rapid decrease in contrast to the large velocity values in the stenotic region. Downstream the stenotic section the pressure fluctuates and presents an increase which is due to the expansion of the geometry. This behavior drastically changes the pressure behavior compared to the previous case.

Finally, WSS, a critical factor in pathological conditions, it is presented for both the upper and lower walls in

Figure 9. The WSS presents a strongly non-linear behavior due to the advanced geometric parameters of the geometry under consideration, such as a stenosis followed by a bifurcation. The stresses, at the bottom wall (blue color), at first present a steady behavior and after this, rapidly increases due to the compression of the flow that lead to the increase in velocity and consequently the increase in WSS value. In the expansion section of the geometry, the WSS rapidly decreases. In this region, often recirculation regions occur that can appear via the change in sign in the WSS. In this case, vortices do not occur. However, a stenosis exceeding

in addition to larger Reynolds number could induce vortex formation.

Figure 10 presents the streamlines in the stenotic bifurcation case. The colors below the streamlines represent the

u-velocity component. These streamlines could be used to trace the trajectories of possible fluid particles, highlighting regions of flow acceleration and motion. This is a multiscale perspective, by connecting the Eulerian field with Lagrangian particle trajectories. The streamlines represent the collective motion of particles responding to pressure and shear forces originating from upstream hemodynamics.

3.2. 3D Multiscale Patient-Specific Results

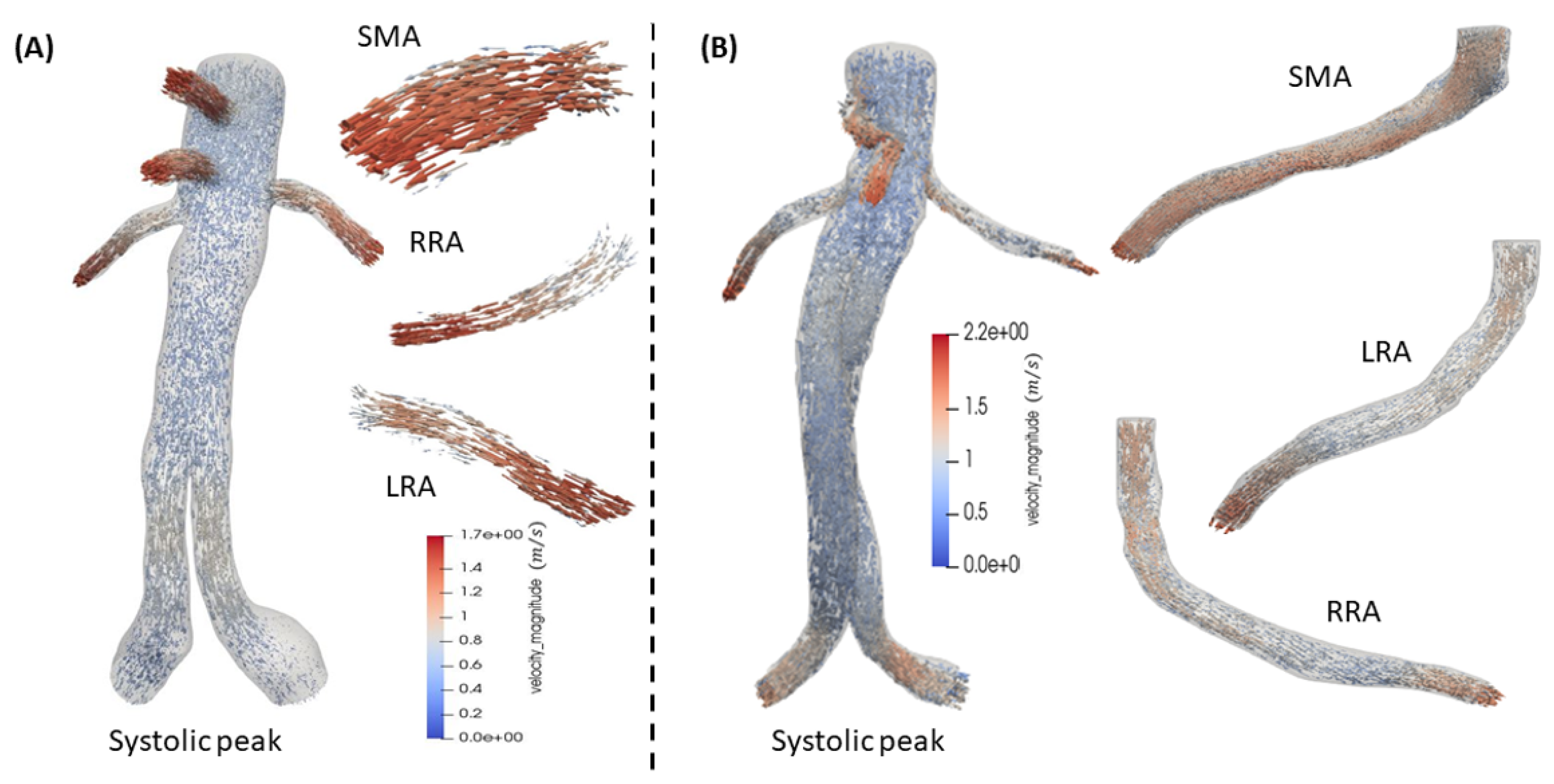

Simulations of the post-operative aorta after B/FEVAR grafts are presented revealing the hemodynamics in these stent designs. In FEVAR the flow remains undisturbed and can be characterized as smooth in the main body of the graft. In contrast, the visceral arteries exhibit more intense behavior. In the case of BEVAR the velocity presents an increase in flow compared to FEVAR, as it can be depicted in

Figure 11. Especially, in the mesenteric artery the flow shows a visible increase compared to BEVAR. The maximum values for FEVAR and BEVAR in systole are approximately

and

, respectively.

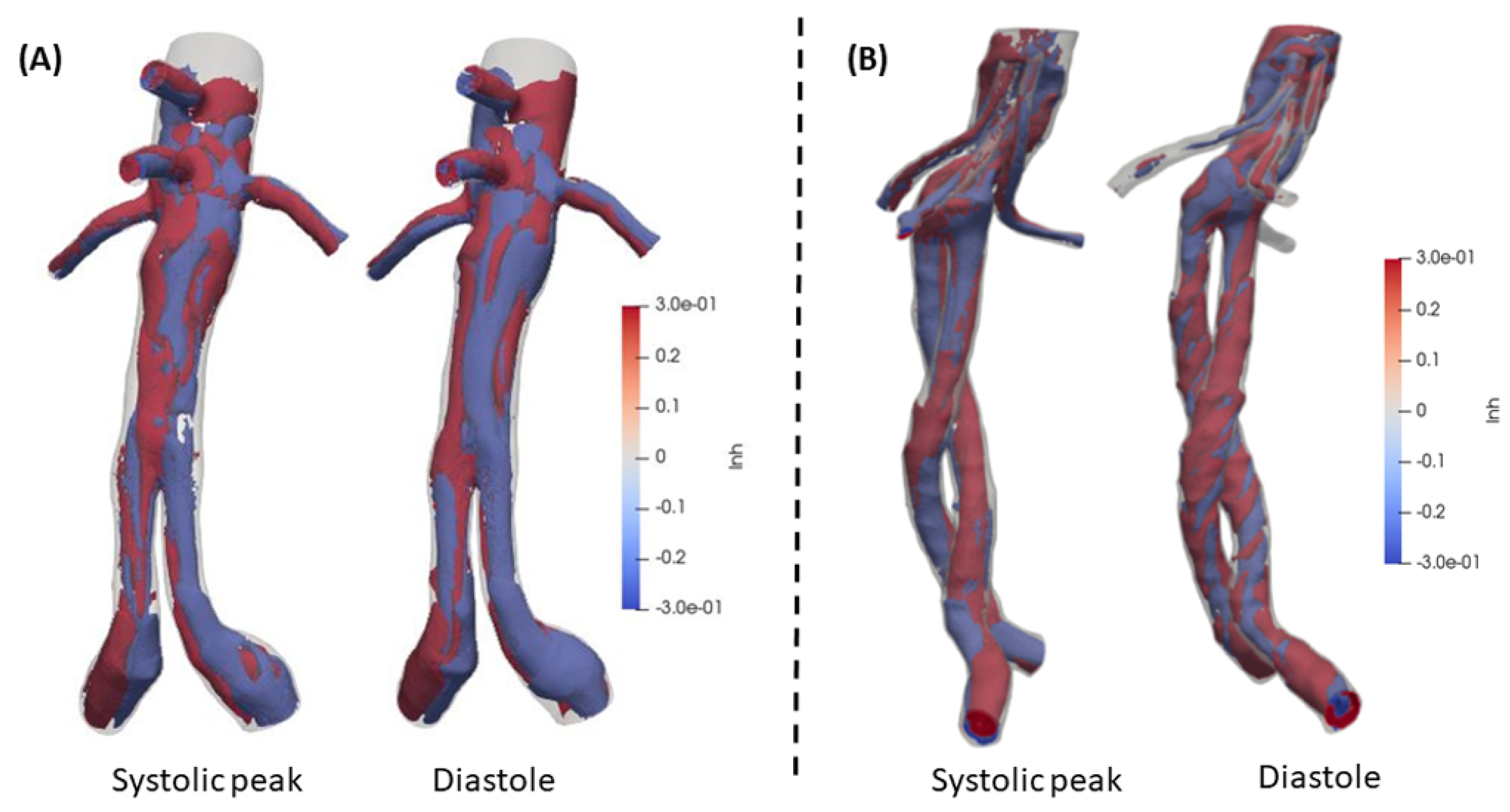

Rotational structures are of great interest in blood flow and LNH is a reliable quantity to evaluate the flow rotation. A threshold (

) has been set according to literature [

34,

36,

38]. The structures that represent helical schemes are distributed uniformly through the domains in both BEVAR and FEVAR cases. The behavior of FEVAR LNH is depicted in

Figure 12(A), where the structures present a compact and smooth behavior in contrast to BEVAR,

Figure 12(B). The maximum values and range of the two cases are identical and finally, BEVAR case structures are more developed and have more rotational disposition (|LNH|

). Visceral (secondary) arteries LNH demonstrates a similar behavior.

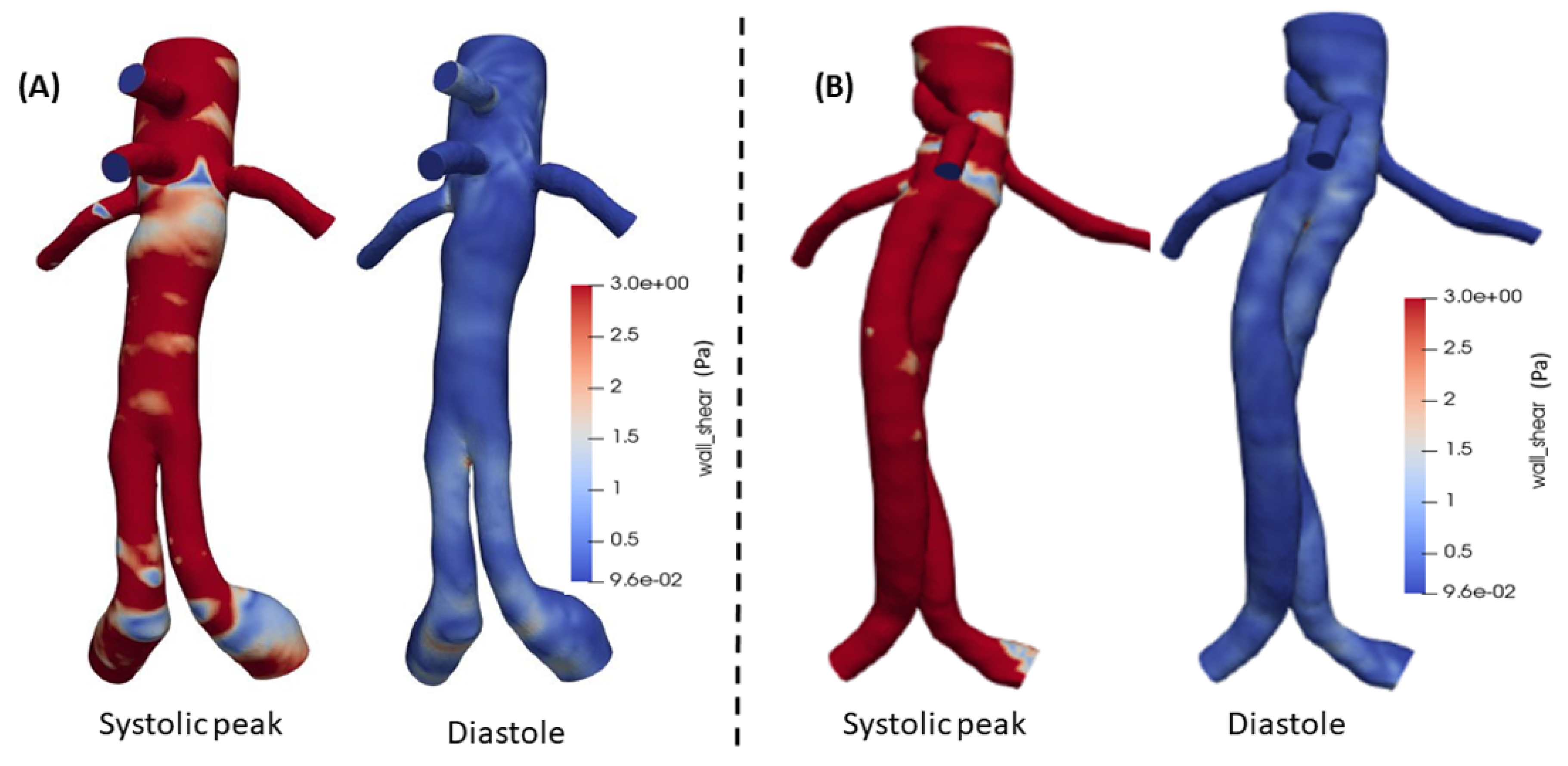

Additionally, the WSS as a significant parameter, is presented in

Figure 13(A) and (B) for both FEVAR and BEVAR cases, respectively, at the peak systole and at the diastolic phase with a maximum value of

for both designs. During the systolic phase in the BEVAR case, higher WSS values are observed compared to FEVAR, especially in the visceral arteries. At the diastolic phase the WSS values are almost identical in both cases.

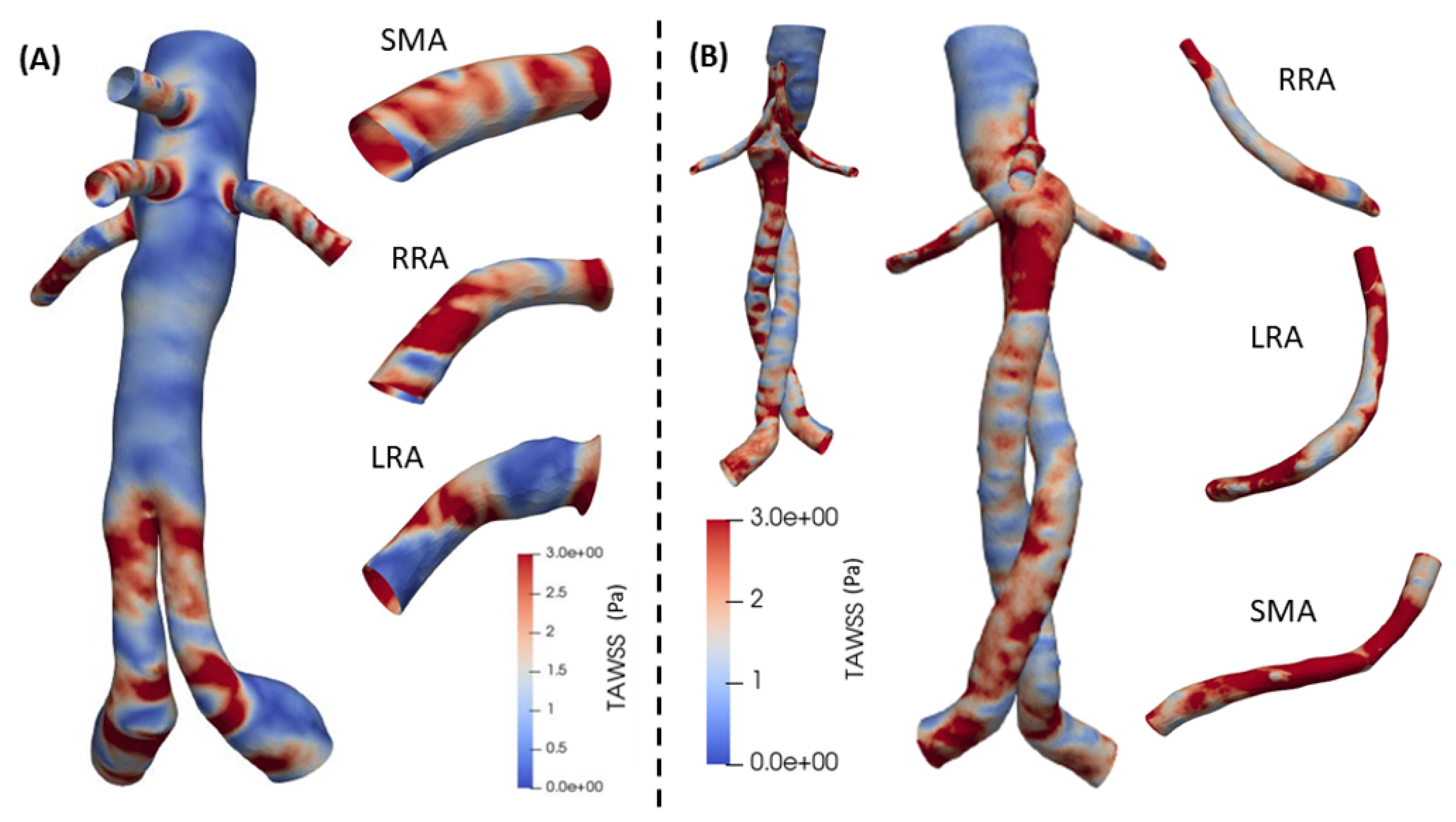

Finally, the TAWSS is depicted in

Figure 14 for both cases. In BEVAR case an overall increase is remarked in the center section of the graft and in the visceral arteries. A large change is also observed in the RRA artery. The behavior of TAWSS in FEVAR case ranges in intermediate values along the entire length. It shows relatively high values in SMA, RRA and LRA at the proximal extent and proximal end. In BEVAR cases, visceral arteries show increased values in most surfaces of the distal end. The postoperative results in both designs, show several variations with a maximum value of

.

4. Discussion

The present work provides an analysis of blood flow in bifurcated stenotic and non-stenotic arteries for . For the channel upstream the bifurcation region, the velocity and pressure fields exhibit a typical Poiseuille flow that is disturbed by the appearance of the bifurcation. A notable difference is observed near the stagnation point of the bifurcation, due to the collision of fluid particles with the arterial walls that drastically increases the WSS values. The flow does not present recirculation regions that could potentially lead to thrombus formation.

The addition of stenosis increased the velocity magnitude and led to a notable decrease in pressure in the stenotic region. The WSS showed an increase of more than in the stenosis region that could lead to undesirable effect on the arterial walls. Furthermore, the flow quantities, and near the bifurcation were altered by the addition of stenosis.

FEVAR and BEVAR are considered optimal treatment options for complex aortic aneurysms. In this study, we compared postoperative hemodynamic effects on the main and the secondary vessels (celiac trunk - CT, superior mesenteric artery - SMA, right renal artery - RRA, left renal artery - LRA) after endovascular aneurysm repair with FEVAR and BEVAR. The patient-specific computational approach offered valuable insights. These findings hold clinical significance and could play a role in selecting the right treatment, minimizing complications in the future [

17,

29]. A thorough comparison of postoperative hemodynamic characteristics between FEVAR and BEVAR was performed highlighting the importance of visceral arteries. Both techniques are considered reliable, resulting in similar outcomes, which are close to normal (healthy) levels [

17,

22,

29].

The results postoperatively exhibits changes in the main lumen and in visceral arteries in fluid flow [

17]. Key hemodynamic parameters behavior is different in each of the two cases providing in both a significant flow improvement [

17,

19,

20,

22]. For the pressure field, FEVAR presented a decrease trend, compared to BEVAR in CT, SMA, RRA and LRA visceral arteries. Postoperatively, due to the reconstruction of the geometry, there was a significant reduction in pressure overall. Specifically, in the case of BEVAR the pressure fluctuates at higher levels compared to FEVAR [

17]. In BEVAR the WSS exhibits a higher overall behavior, in FEVAR WSS is also high in visceral arteries but presents slightly lower values in the main body. Almost identical characteristics have been observed in previous simulations conducted on FEVAR cases [

18,

19].

Large LNH values are connected with regular flow circulation, inhibiting blood cell adhesion to the arterial wall and reducing thrombus formation [

36]. LNH in FEVAR cases present uniform and compact structures in the entire cardiac cycle, which is also validated in previous studies [

18,

19]. Overall, values of TAWSS are larger in the BEVAR case and it is more intense in RRA artery, this is cross checked with the work in [

17]. They concluded that the patient geometric morphology of the renal arteries was the reason for the variations observed between the FEVAR and BEVAR cases. Thrombus deposition and atherogenesis are linked to abnormally high or low TAWSS levels [

17,

22]. For BEVAR at systolic peak, the flow rate was higher than in FEVAR, between renals it ranged moderately but the most intense variation resulted in the mesenteric artery. Postoperatively, flow in CT, SMA, RRA and LRA with both techniques remodeled to approach normal (healthy) hemodynamic characteristics [

29].

The fundamental difference between BEVAR and FEVAR with the larger cross-sectional area of fenestrations may explain the larger values in the velocity field. In FEVAR procedures, fenestrations are aligned vertically with the custom-made openings, whereas in BEVAR procedures, they are incorporated into built-up side branches within the main graft segment, consisting of devices that combine visceral side branches with fenestrations [

17]. Significant changes in the geometry of these side branches (whether FEVAR or BEVAR) may negatively impact blood flow behavior. In the BEVAR technique, longer bridging stents facilitate blood flow expansion before it reaches the visceral artery [

22]. This essential difference might also contribute to the creation of recirculation regions in FEVAR case at the entrance of the bridging stents. In the BEVAR case, the recirculation regions are more intense in the CT and LRA artery, that leads to increase of reversed flow rate, this may be promoted from the fact that there is a flow decrease in this artery.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the geometric effects on blood flow are analyzed in both bifurcated and stenotic bifurcated cases. The coupling of the Finite Volume Method with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm ensures convergent and robust results. Geometry plays a crucial role in flow behavior, with particular interest in the stresses observed in both cases. Specifically, the stenotic bifurcation geometry exhibits higher values of wall shear stresses compared to the standard bifurcation, highlighting the danger for patient’s health from such a pathological condition. Additionally, significant pressure gradients observed in the stenotic case may contribute to vascular complications.

Furthermore, a multiscale mathematical model is employed, coupling the 0D Windkessel with 1D boundary conditions waveforms and finally the 3D simulations to provide valuable insights into the post-operative aortic blood flow. Some important and influential quantities such as velocity, LNH, WSS and TAWSS are examined in patient-specific aortas in cases of advanced stent devices, BEVAR and FEVAR. These state-of-the-art grafts, are regarded as the best for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) and are worth analyzed via CFD. The two grafts provide similar results in most parameters and improve toward normal (healthy) hemodynamics. The FEVAR exhibits smaller values of velocity and more uniform, smooth helicity compared to BEVAR. The visceral arteries that are modeled through the multiscale model present increased values in BEVAR compared to the FEVAR cases. The 3D patient-specific aortas utilized, enhances the clinical relevance of this study, offering valuable guidance for personalized treatment strategies. This could lead in the future to technological refinement of more specific branch endografts to be used in F/BEBAR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K., S.M., A.R., M.M., A.G., M.X.; methodology, S.K., S.M., A.R., M.M., A.G., M.X.; software, S.K., S.M., A.R.; validation, S.K., S.M., A.R., M.X.; formal analysis, S.K., S.M.; investigation, S.K., S.M., A.R., M.M., A.G., M.X.; resources, M.M., A.G.; data curation, S.K., S.M., A.R., M.X.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K., S.M., M.X.; writing—review and editing, S.K., S.M., A.R., M.M., A.G., M.X.; visualization, S.K., S.M.; supervision, M.M., A.G., M.X.; project administration, S.K., M.X.; funding acquisition, M.M., A.G., M.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the framework of the Action “Flagship actions in interdisciplinary scientific fields with a special focus on the productive fabric,” which is implemented through the National Recovery and Resilience Fund Greece 2.0 and funded by the European Union–Next Generation EU (Project ID: TAEDR-0535983).

Informed Consent Statement

The processed imaging data were totally anonymised, thus no ethics committee approval was necessary.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pedley, T. J.; Schroter, R. C.; Sudlow, M. F. Flow and Pressure Drop in Systems of Repeatedly Branching Tubes.Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1971, 46 (2), 365–383. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, K.; Guha, A. Fluid Dynamics of a Bifurcation. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2019, 80, 108483. [CrossRef]

- David De Wilde; Bram Trachet; Debusschere, N.; Iannaccone, F.; Swillens, A.; Degroote, J.; Vierendeels, J.; Guido; Segers, P. Assessment of Shear Stress Related Parameters in the Carotid Bifurcation Using Mouse-Specific FSI Simulations, Journal of biomechanics 2016, 49 (11), 2135–2142. [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, N.; Micker, M.; Ciałkowski, M.; Warot, M.; Chęciński, M. Numerical Study of Carotid Bifurcation Angle Effect in Blood Flow Disorders. In New Developments on Computational Methods and Imaging in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering, Editor 1, João Manuel R.S. Tavares, Editor 2, Paulo Rui Fernandes, Publisher: Springer, 2019. .

- Ahmed, H.; Podder, C. Hemodynamical Behavior Analysis of Anemic, Diabetic, and Healthy Blood Flow in the Carotid Artery. Heliyon 2024, 10 (4), e26622. [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Manuel, F.; Doce, Y.; Castro, F.; Fernández, J. A. Pulsatile Flow in Coronary Bifurcations for Different Stenting Techniques. 10th World Congress on Computational Mechanics 2014, 1382–1394. [CrossRef]

- Younis, H. F.; Kaazempur-Mofrad, M. R.; Chan, R. C.; Isasi, A. G.; Hinton, D. P.; Chau, A. H.; Kim, L. A.; Kamm, R. D. Hemodynamics and Wall Mechanics in Human Carotid Bifurcation and its Consequences for Atherogenesis: Investigation of Inter-Individual Variation. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology 2004, 3 (1), 17–32 .

- Chrimatopoulos G.; Tzirtzilakis, E. E.; Xenos, M. A. Magnetohydrodynamic and Ferrohydrodynamic Fluid Flow Using the Finite Volume Method.Fluids 2023, 9(1), 5–5. [CrossRef]

- Aravanis T.; Chrimatopoulos G.; Xenos, M.; Tzirtzilakis, E. E. Forecasting two-dimensional channel flow using machine learning.Physics of Fluids 2024, 36(10). [CrossRef]

- Xenos, M. A. An Euler–Lagrange approach for studying blood flow in an aneurysmal geometry. Proceedings of the Royal Society a Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences, 2017, 473(2199), 20160774–20160774. [CrossRef]

- Jorge Nocedal; Stephen J. Wright, Numerical Optimization, 2nd ed.; Publisher: Springer New York, NY, 2006; [CrossRef]

- Guha, A. and Pradhan, K. Secondary motion in 3D branching networks. Physics of Fluids 2017, 29(6). [CrossRef]

- Wilquem, F.; Degrez, G. Numerical Modeling of Steady Inspiratory Airflow Through a Three-Generation Model of the Human Central Airways. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 1997, 119(1), 59–65. [CrossRef]

- Comer, J. K., Kleinstreuer, C., & Kim, C.S. Flow Structures and Particle Deposition Patterns in Double-Bifurcation Airway Models. Part 2. Aerosol Transport and Aeposition. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2001, 435, 55–80. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., So, R. M. C., & Zhang, C. H. Modeling the Bifurcating Flow in a Human Lung Airway. Journal of Biomechanics 2002, 35(4), 465–473. [CrossRef]

- Fresconi, F. E., & Prasad, A. K. Secondary Velocity Fields in the Conducting Airways of the Human Lung. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 2007, 129(5), 722–732. [CrossRef]

- Tran, K., Deslarzes-Dubuis, C., DeGlise, S., Kaladji, A., Yang, W., Marsden, A. L., Lee, J. T. Patient-Specific Computational Flow Simulation Reveals Significant Differences in Paravisceral Aortic Hemodynamics between Fenestrated and Branched Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. JVS-Vascular Science 2023, 5, 100183. [CrossRef]

- Malatos, S., Raptis, A., Xenos, M.A., Kouvelos, G., Giannoukas, A. and Verhoeven, E.L. A multiscale model for hemodynamic properties’ prediction after fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repair. A pilot study. Hellenic Vascular Journal 2019, 1 (2), pp. 73-79. .

- Malatos, S., Fazzini, L., Raptis, A., Nana, P., Kouvelos, G., Tasso, P., Gallo, D., Morbiducci, U., Xenos, M. A., Giannoukas, A., & Matsagkas, M. Evaluation of Hemodynamic Properties After Chimney and Fenestrated Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Annals of Vascular Surgery 2024, 104, 237–247. [CrossRef]

- Kandail, H. S., Hamady, M., & Xu, X. Y. Hemodynamic Functions of Fenestrated Stent Graft under Resting, Hypertension, and Exercise Conditions. Frontiers in surgery 2016, 3, 35. [CrossRef]

- Haulon S, Steinmetz E, Feugier P, et al. Two-Year Results on Real-World Fenestrated or Branched Endovascular Repair for Complex Aortic Abdominal Aneurysm in France. Journal of Endovascular Therapy 2023;0(0). [CrossRef]

- Suess, T., Anderson, J., Danielson, L., Pohlson, K., Remund, T., Blears, E., Gent, S., & Kelly, P. Examination of near-wall hemodynamic parameters in the renal bridging stent of various stent graft configurations for repairing visceral branched aortic aneurysms. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2015, 64(3), 788–796. [CrossRef]

- Ricotta, J. J., & Oderich, G. S. Fenestrated and branched stent grafts. Perspectives in vascular surgery and endovascular therapy 2008, 20 2, 174-87; discussion 188-9.

- Verhoeven, E. L., Vourliotakis, G., Bos, W. T., Tielliu, I. F., Zeebregts, C. J., Prins, T. R., Bracale, U. M., & van den Dungen, J. J. Fenestrated stent grafting for short-necked and juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm: an 8-year single-centre experience.European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 2010, 39(5), 529–536. [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, E. L., Tielliu, I. F., Bos, W. T., & Zeebregts, C. J. Present and future of branched stent grafts in thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: a single-centre experience. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 2009, 38(2), 155–161. [CrossRef]

- Reymond, P., Merenda, F., Perren, F., Rüfenacht, D., & Stergiopulos, N. Validation of a one-dimensional model of the systemic arterial tree. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2009, 297(1), H208–H222. [CrossRef]

- Morbiducci, U., Ponzini, R., Gallo, D., Bignardi, C., & Rizzo, G. Inflow boundary conditions for image-based computational hemodynamics: impact of idealized versus measured velocity profiles in the human aorta. Journal of biomechanics 2013, 46(1), 102–109. [CrossRef]

- van de Vosse, F. N., & Stergiopulos, N. Pulse Wave Propagation in the Arterial Tree. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2011, 43(1), 467–499. [CrossRef]

- Raptis, A., Xenos, M., Georgakarakos, E., Kouvelos, G., Giannoukas, A., Labropoulos, N., & Matsagkas, M. Comparison of physiological and post-endovascular aneurysm repair infrarenal blood flow. Computer methods in biomechanics and biomedical engineering 2017, 20(3), 242–249. [CrossRef]

- Donas, K. P., Torsello, G. B., Piccoli, G., Pitoulias, G. A., Torsello, G. F., Bisdas, T., Austermann, M., & Gasparini, D. The PROTAGORAS study to evaluate the performance of the Endurant stent graft for patients with pararenal pathologic processes treated by the chimney/snorkel endovascular technique. Journal of vascular surgery 2016, 63(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ullery, B. W., Tran, K., Itoga, N. K., Dalman, R. L., & Lee, J. T. Natural history of gutter-related type Ia endoleaks after snorkel/chimney endovascular aneurysm repair.Journal of vascular surgery 2017, 65(4), 981–990. [CrossRef]

- Olufsen, M. S.; Peskin, C. S.; Kim, W. Y.; Pedersen, E. M.; Nadim, A.; Larsen, J. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Validation of Blood Flow in Arteries with Structured-Tree Outflow Conditions. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 2000, 28 (11), 1281–1299. [CrossRef]

- Stergiopulos, N.; Young, D. F.; Rogge, T. R. Computer Simulation of Arterial Flow with Applications to Arterial and Aortic Stenoses. Journal of Biomechanics 1992, 25 (12), 1477–1488. [CrossRef]

- Tasso, P., Raptis, A., Matsagkas, M., Rizzini, M. L., Gallo, D., Xenos, M., & Morbiducci, U. . Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Endovascular Repair: Profiling Postimplantation Morphometry and Hemodynamics With Image-Based Computational Fluid Dynamics. Journal of biomechanical engineering 2018, 140(11), 111003. [CrossRef]

- Morbiducci, U., Ponzini, R., Rizzo, G., Cadioli, M., Esposito, A., De Cobelli, F., Del Maschio, A., Montevecchi, F. M., & Redaelli, A. In vivo quantification of helical blood flow in human aorta by time-resolved 3D cine phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging. Annals of biomedical engineering 2009, 37(3), 516–531. [CrossRef]

- Morbiducci, U., Ponzini, R., Grigioni, M., & Redaelli, A. Helical flow as fluid dynamic signature for atherogenesis risk in aortocoronary bypass. A numeric study. Journal of biomechanics 2007, 40(3), 519–534. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, D., Steinman, D. A., Bijari, P. B., & Morbiducci, U. Helical flow in carotid bifurcation as surrogate marker of exposure to disturbed shear. Journal of biomechanics 2012, 45(14), 2398–2404. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, D., Bijari, P. B., Morbiducci, U., Qiao, Y., Xie, Y. J., Etesami, M., Habets, D., Lakatta, E. G., Wasserman, B. A., & Steinman, D. A. . Segment-specific associations between local hemodynamic and imaging markers of early atherosclerosis at the carotid artery: an in vivo human study. Journal of the Royal Society 2018, Interface, 15(147), 20180352. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).