Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

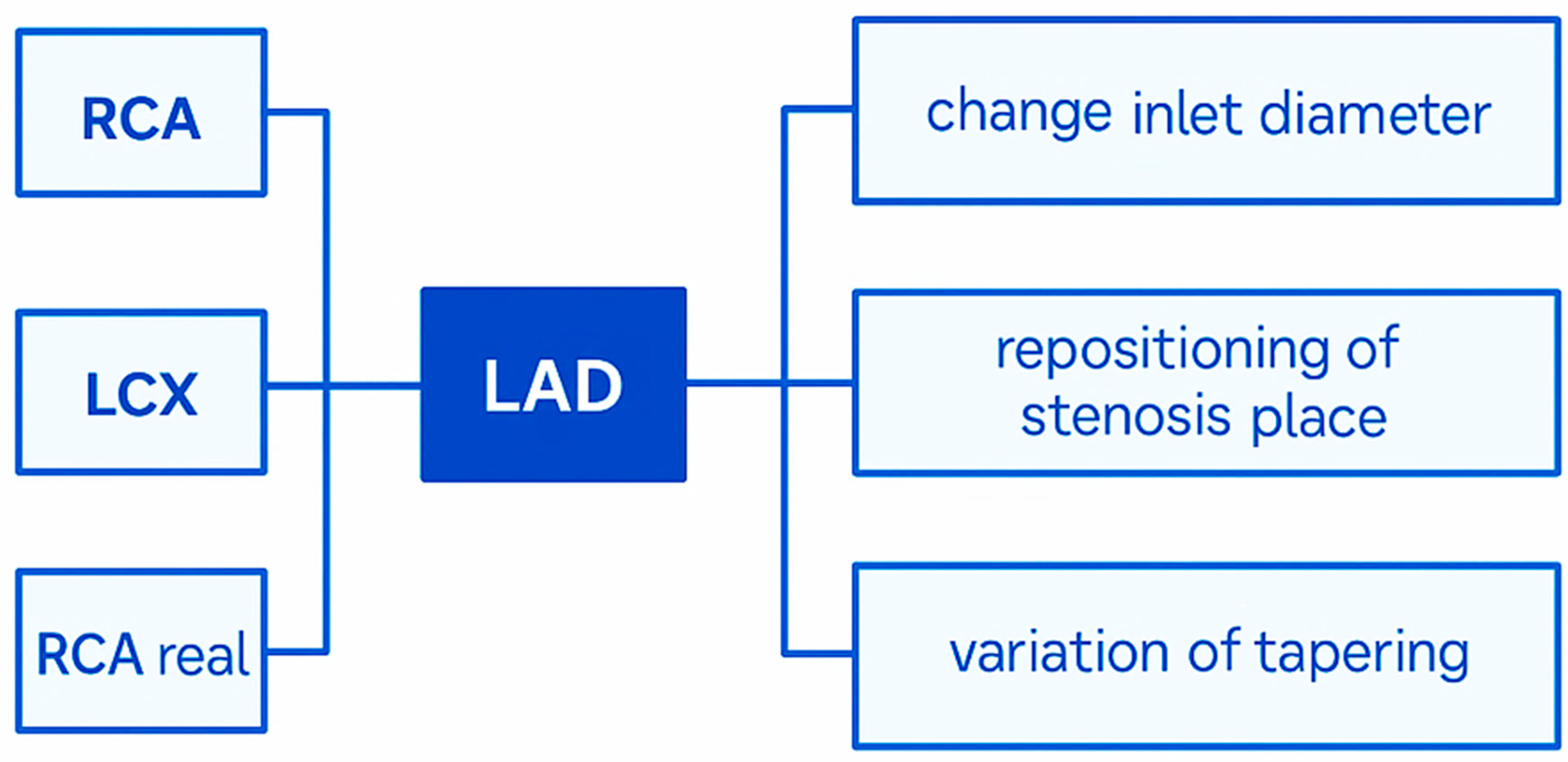

2. Materials and Methods

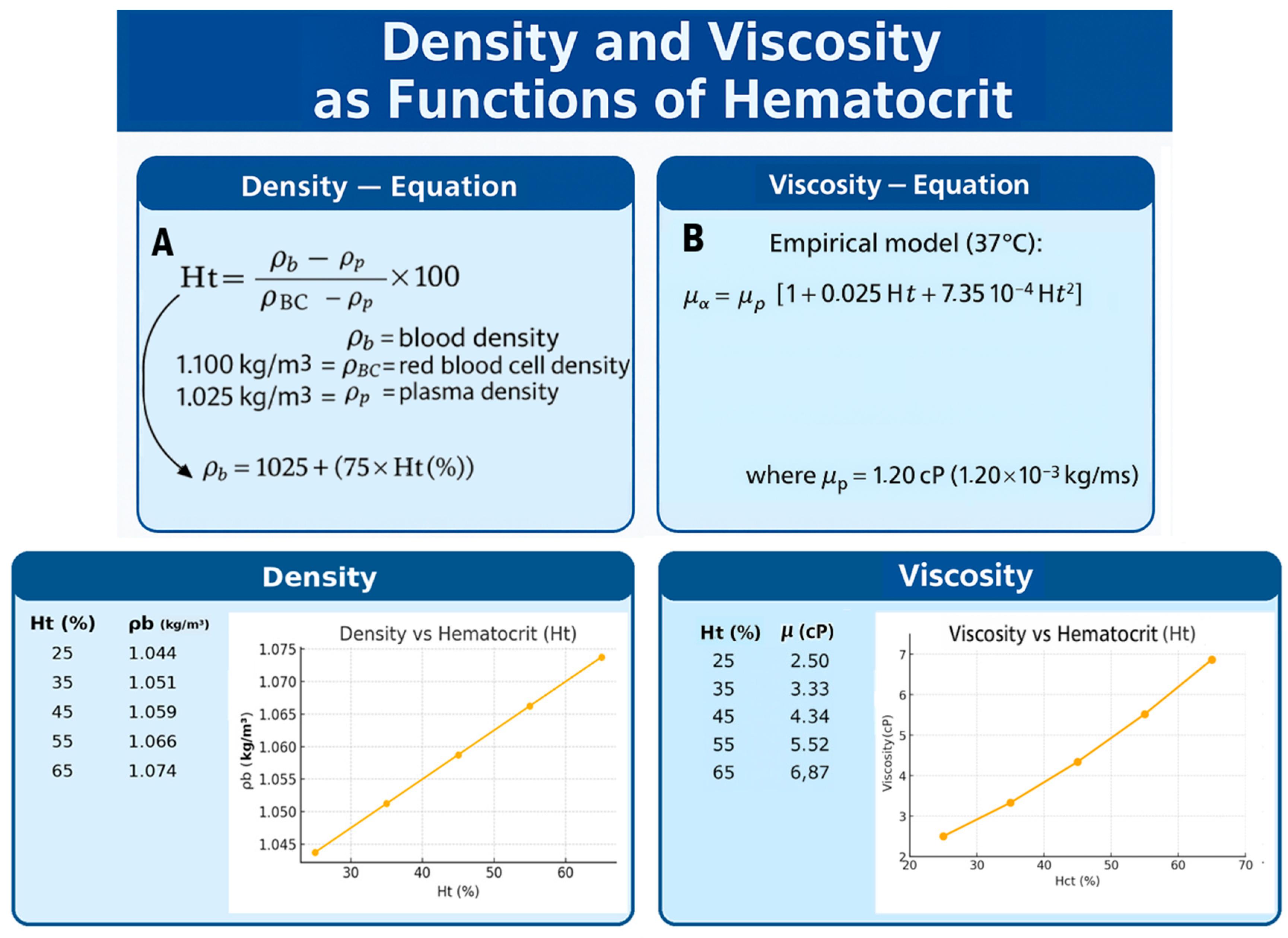

2.1. Clinical Variables Applied to CFD

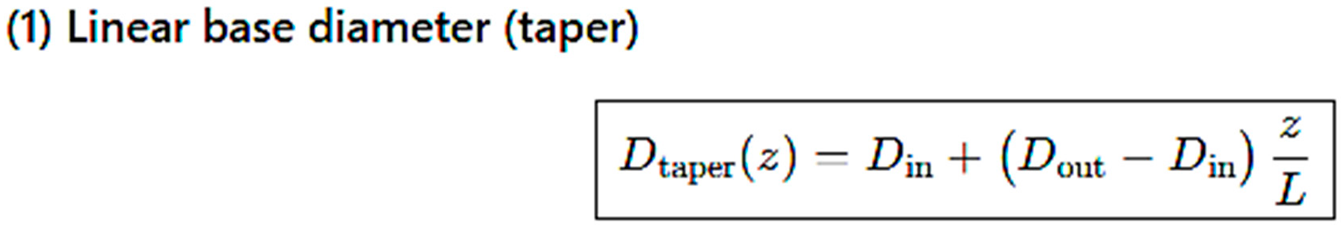

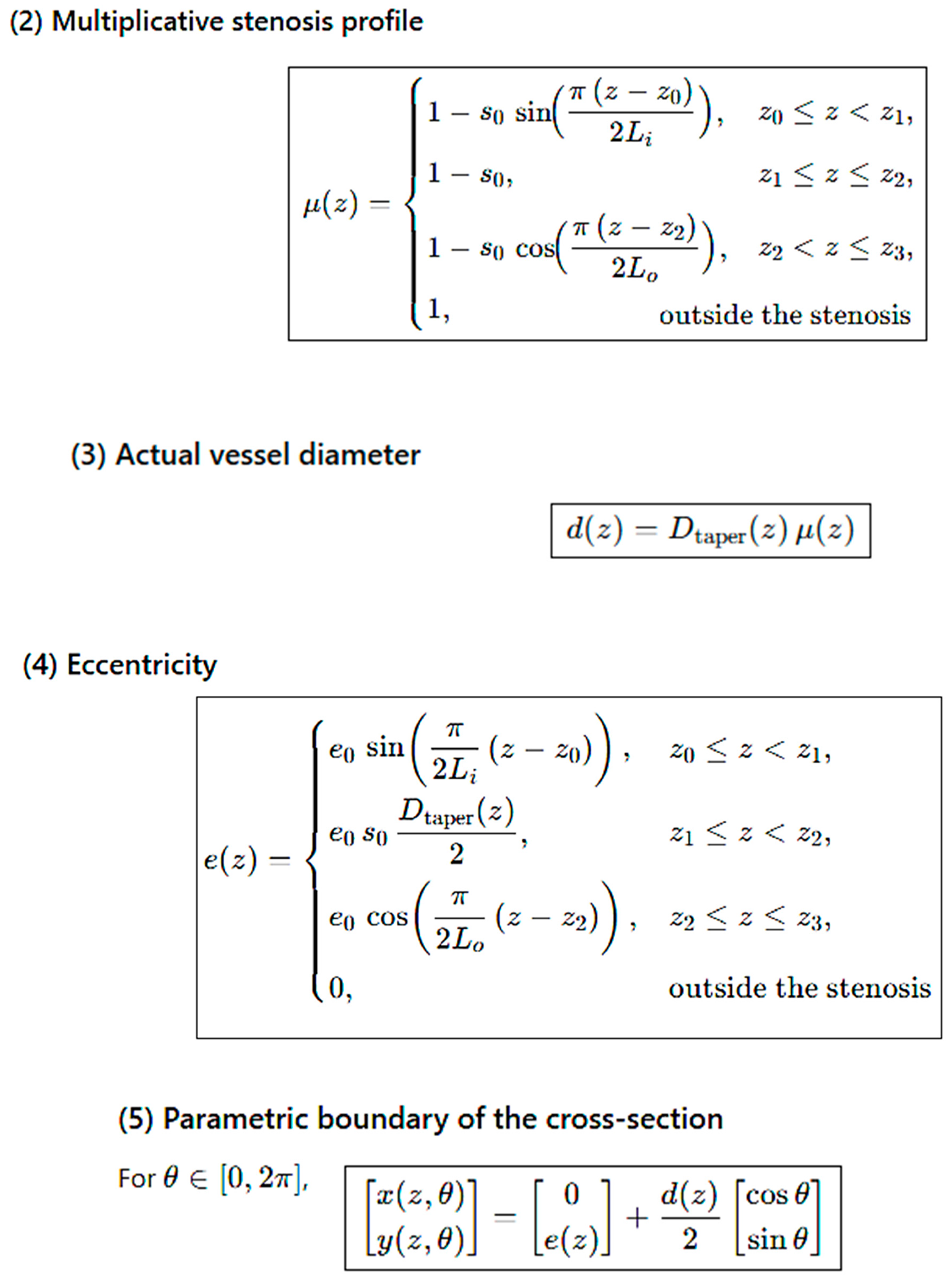

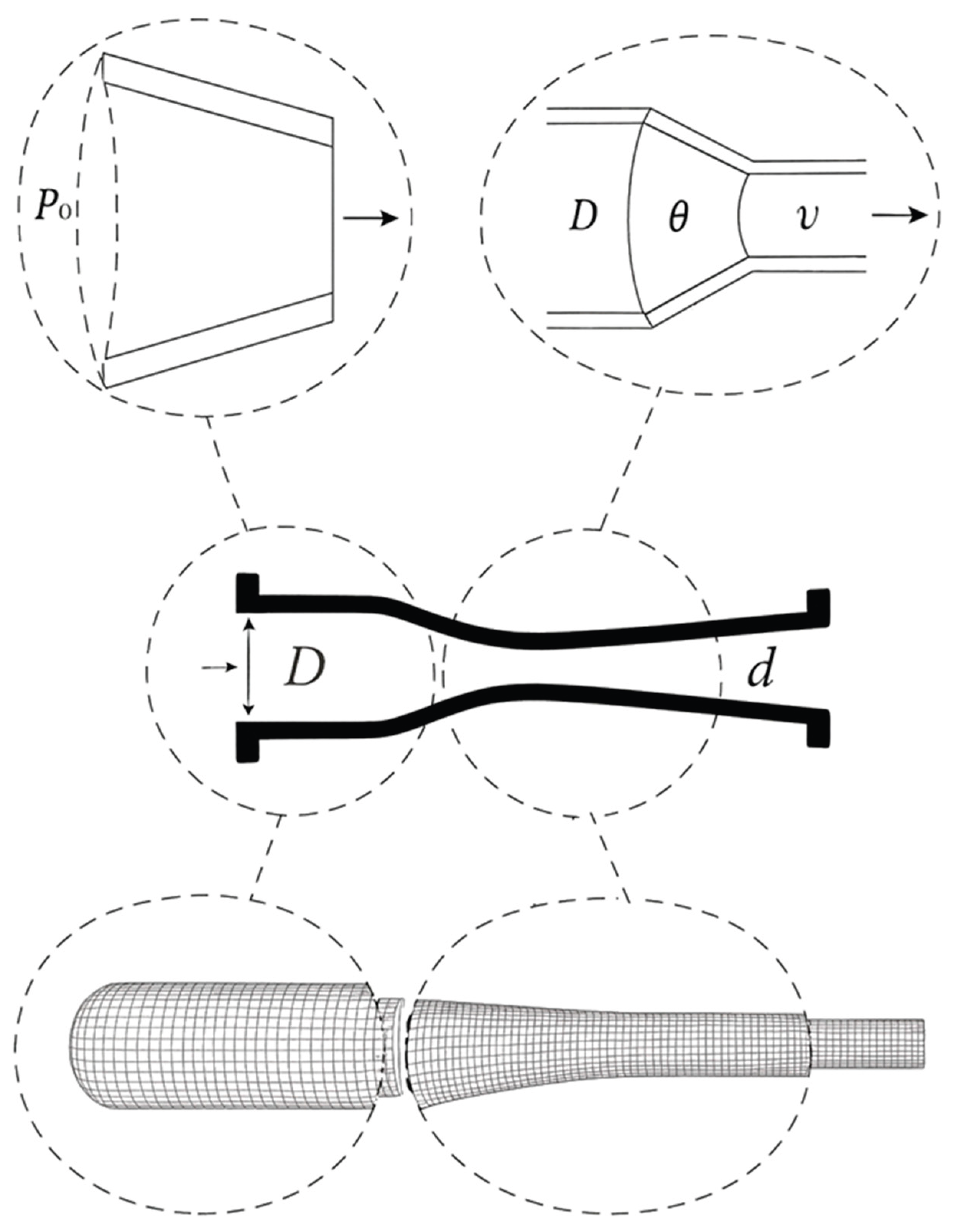

Computational Mesh Geometry

3. Results

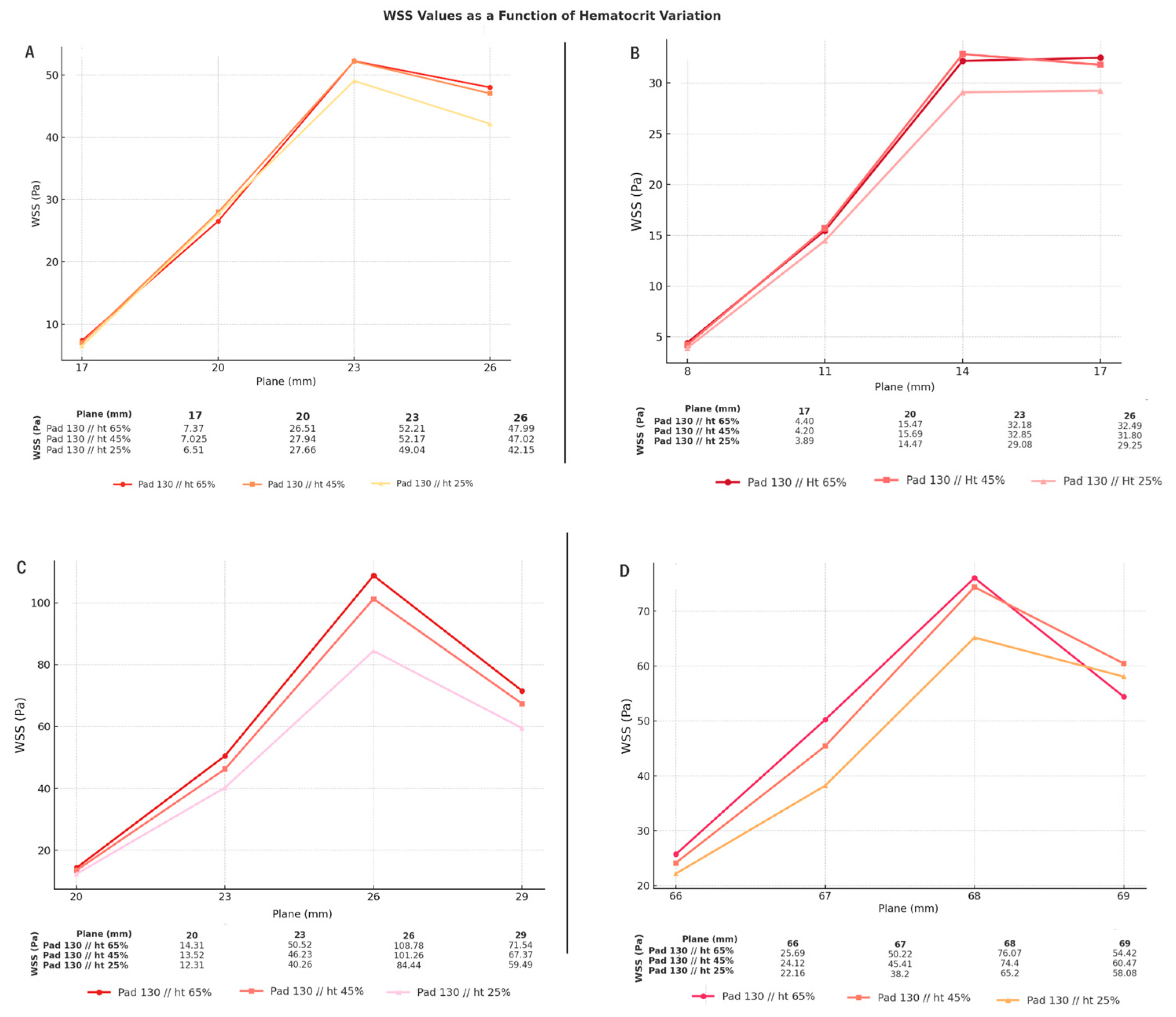

3.1. Comparison of Hematocrit

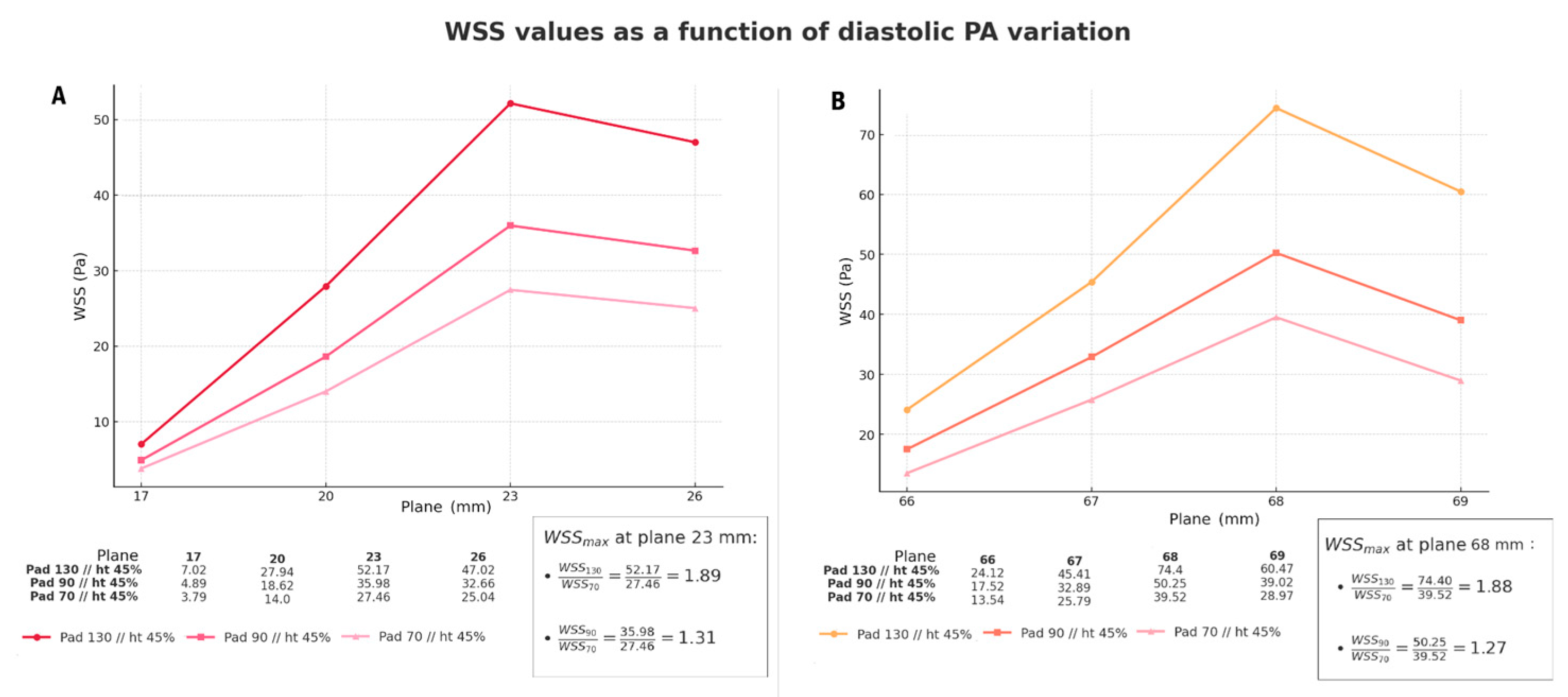

3.2. Comparison of Different Inlet Pressure Values

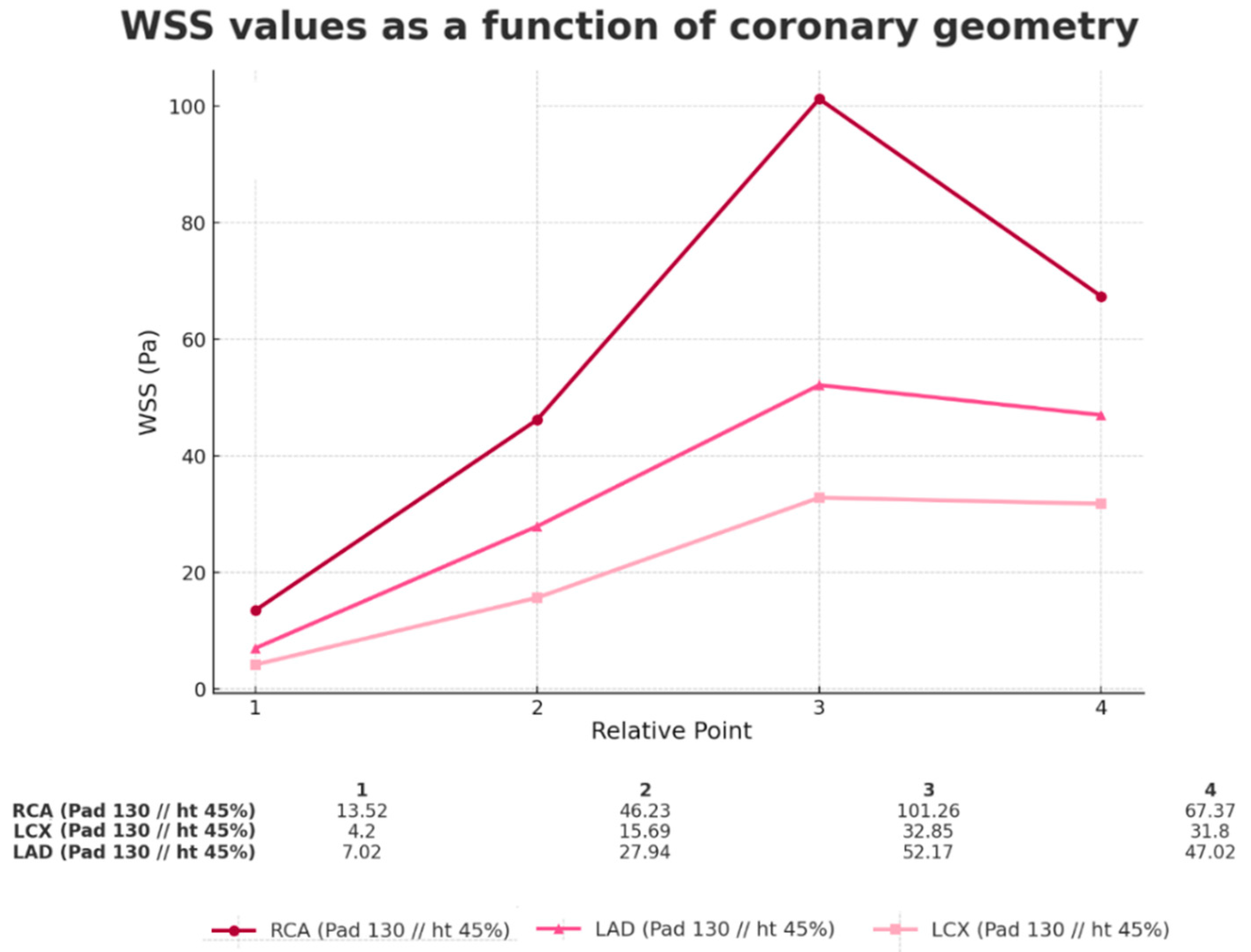

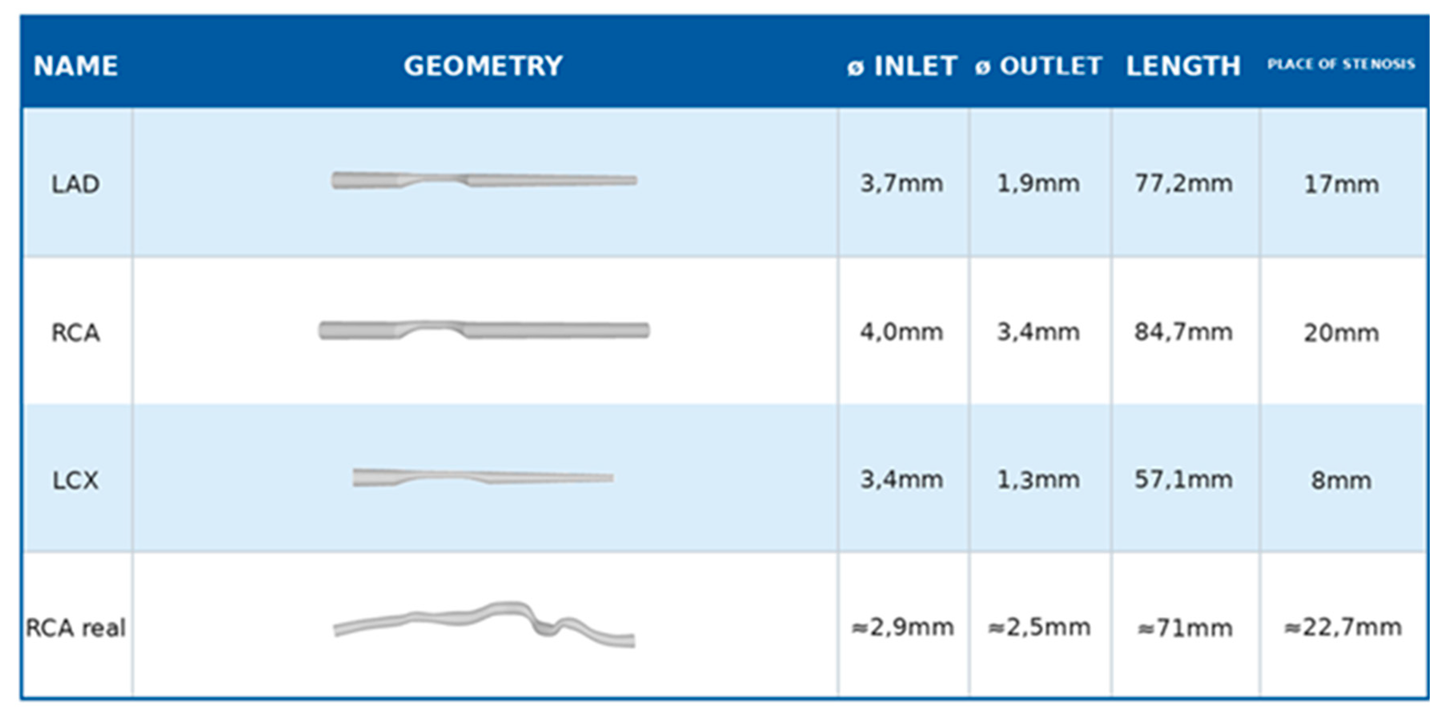

3.3. Comparison of Different Arteries (Geometries)

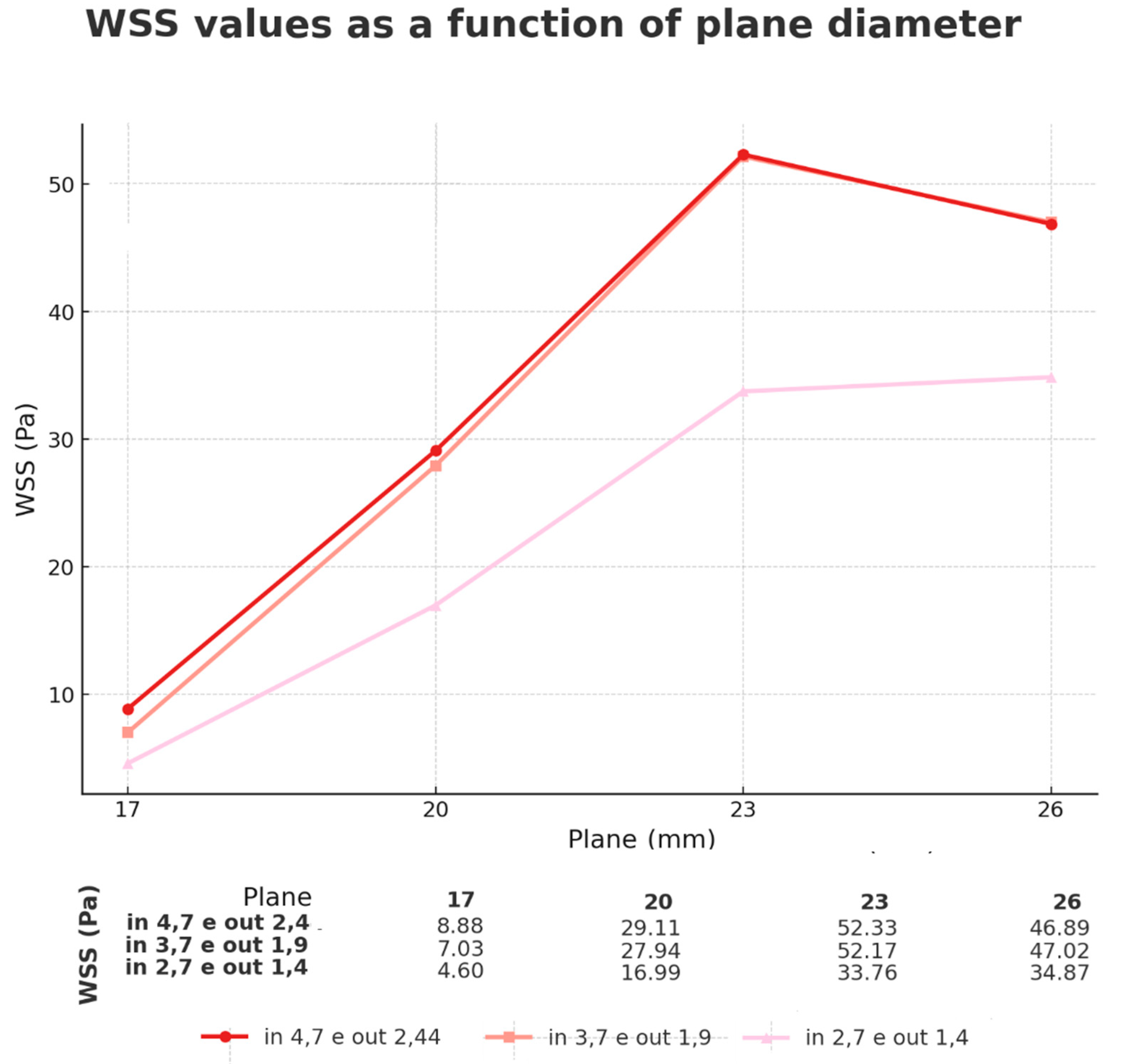

3.4. Comparison of Different Inlet Diameters (Geometries)

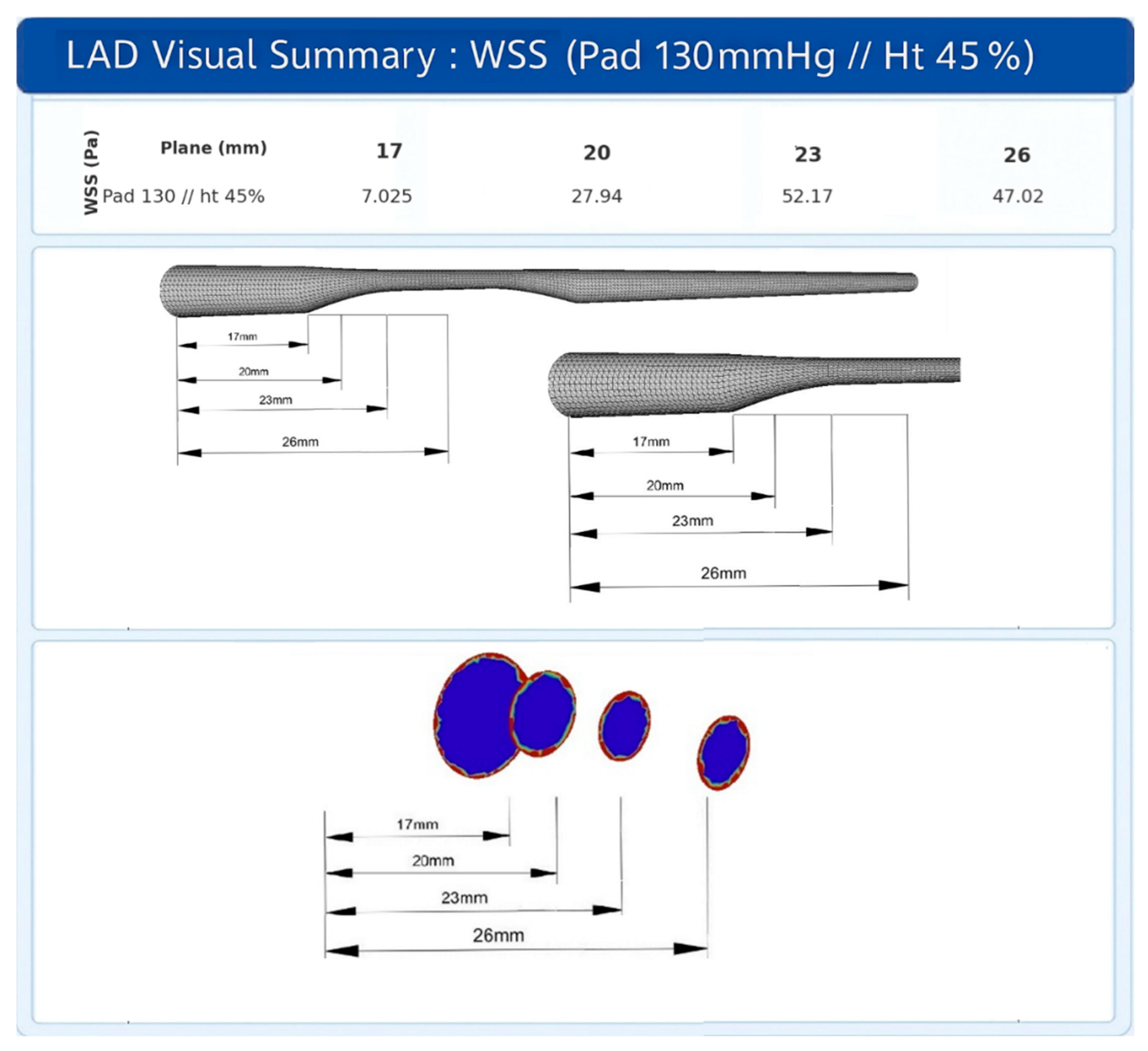

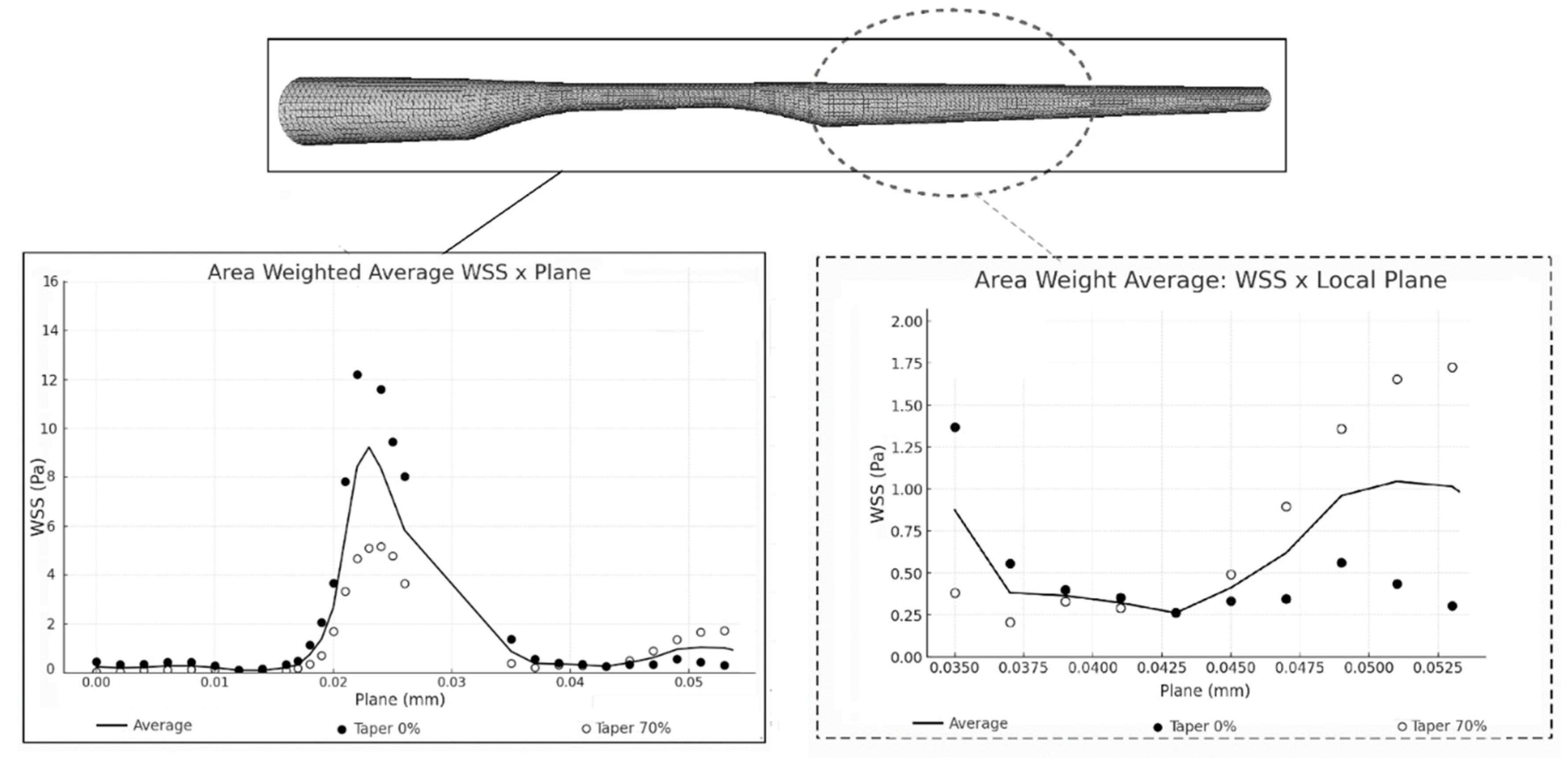

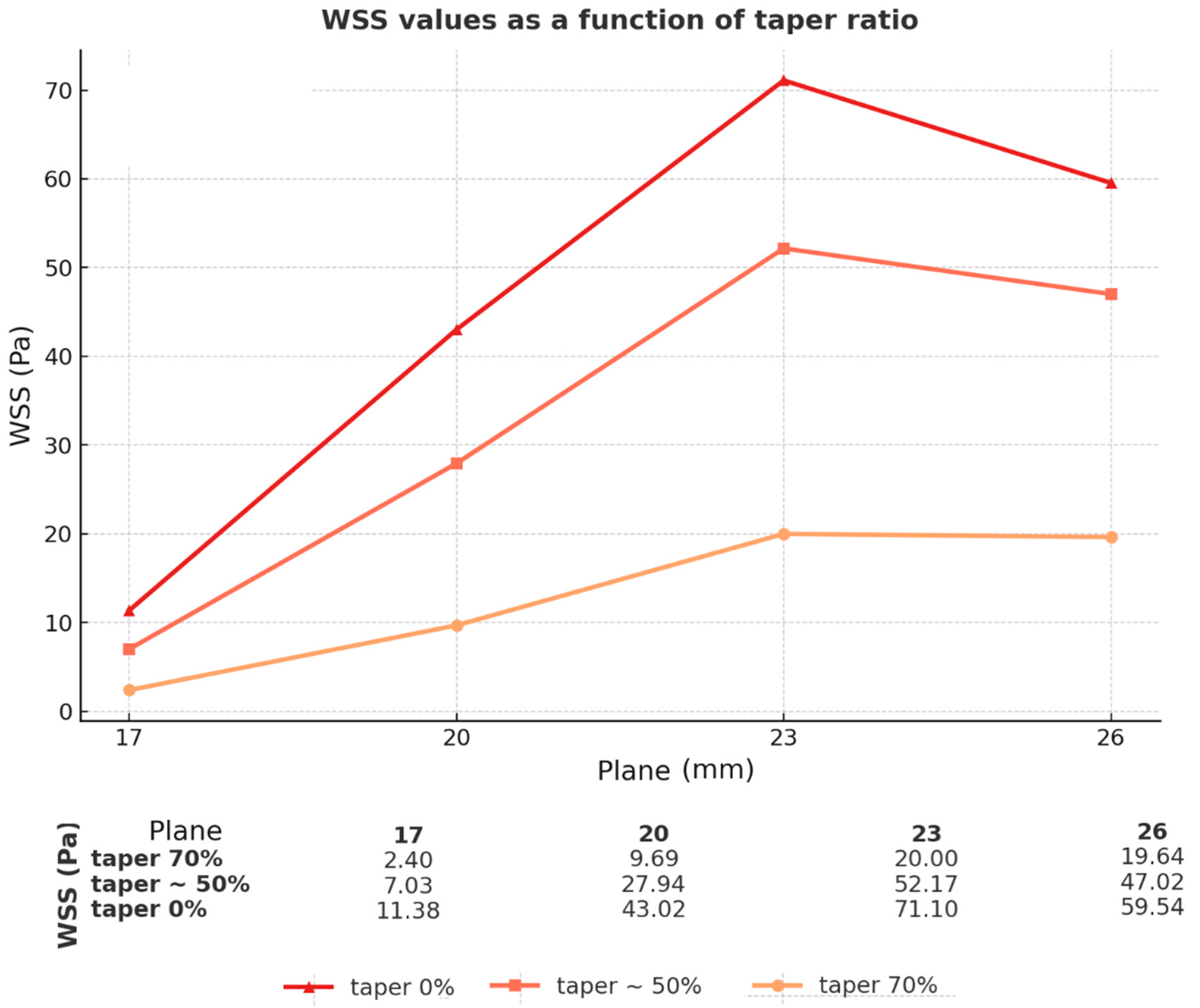

3.5. Comparison of Different Taper (Geometries)

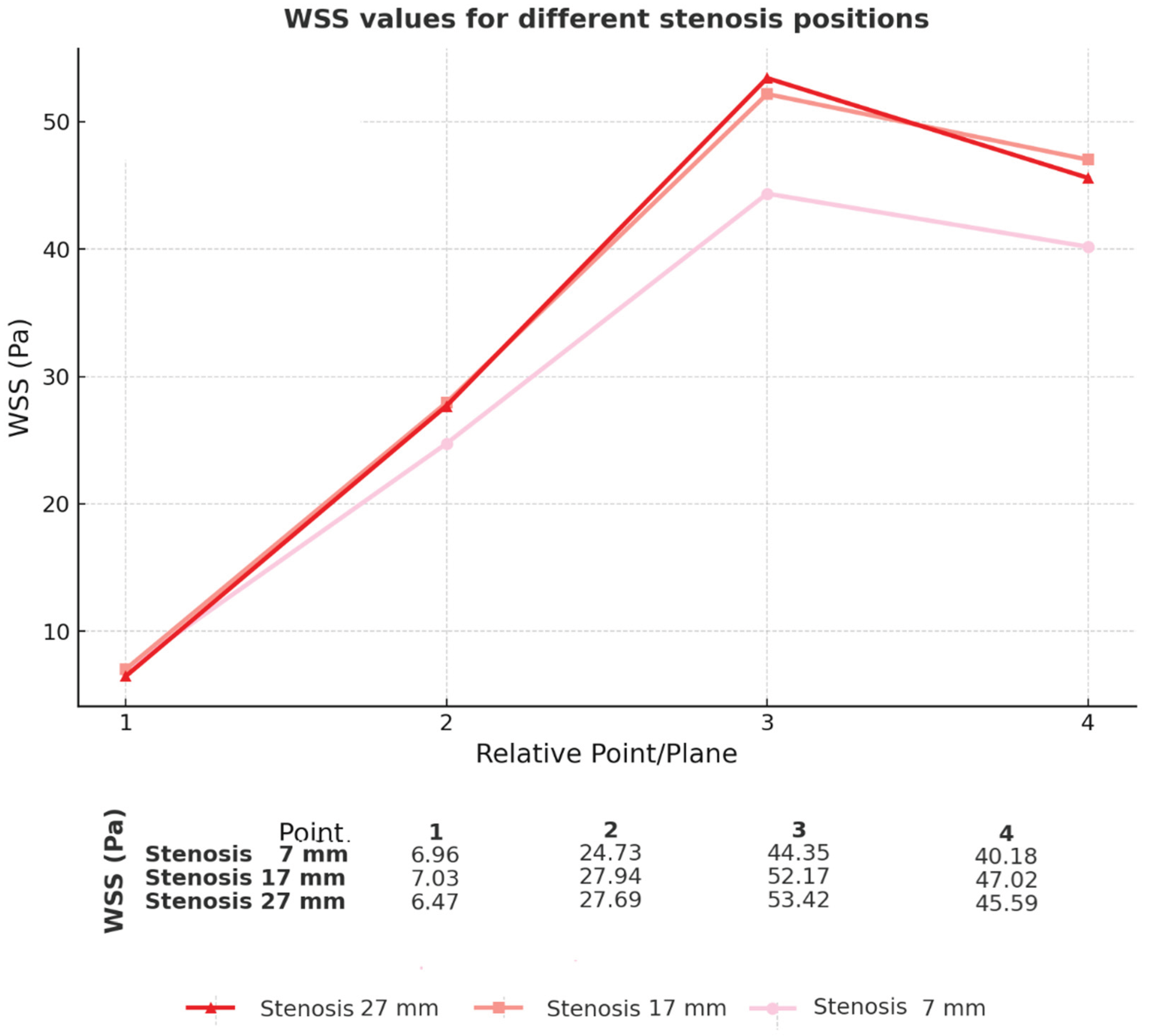

3.6. Comparison of Different Sites of Stenosis Initiation (Geometries)

4. Discussion

4.1. Gap in the Literature

4.2. Analysis of Simulated Results

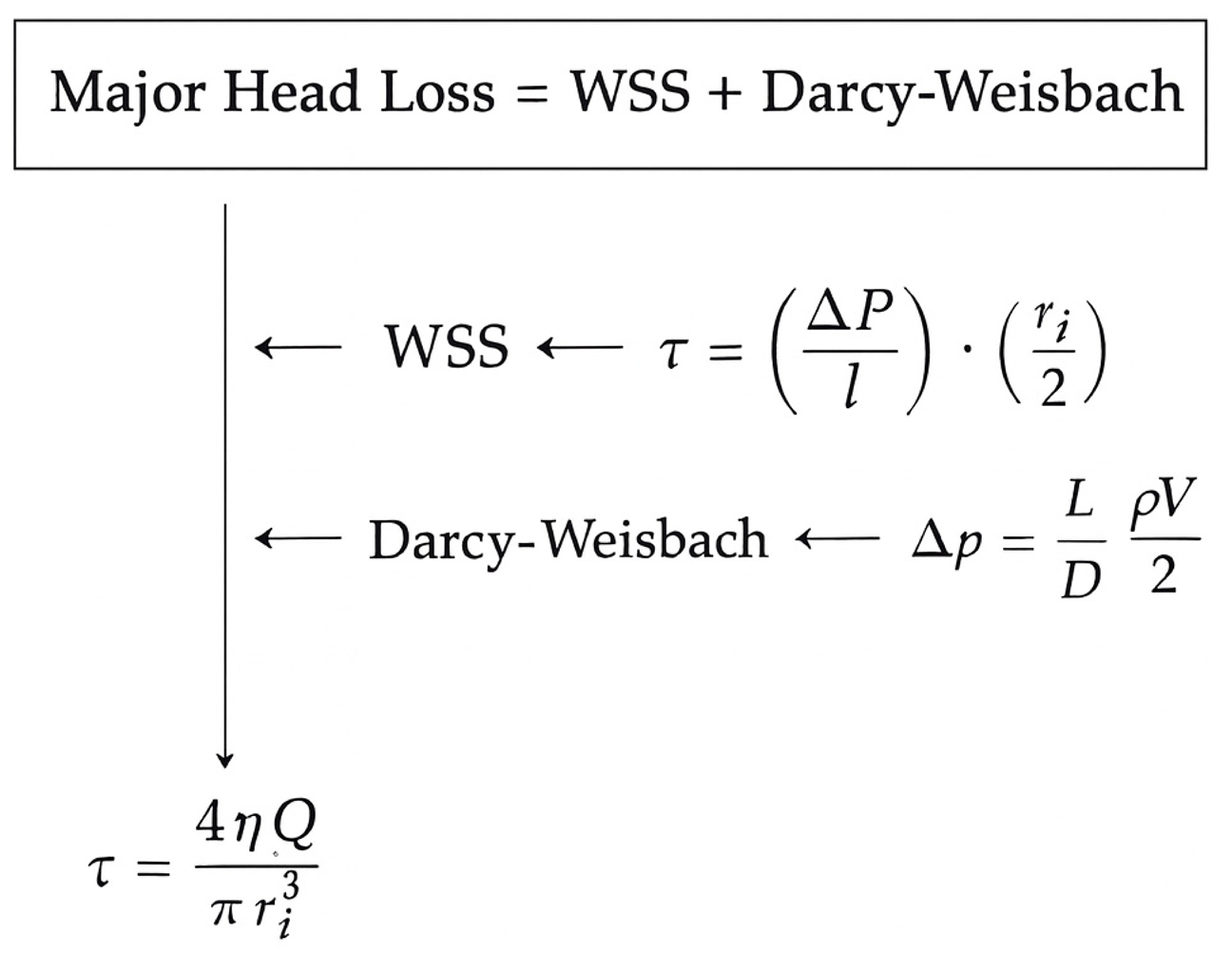

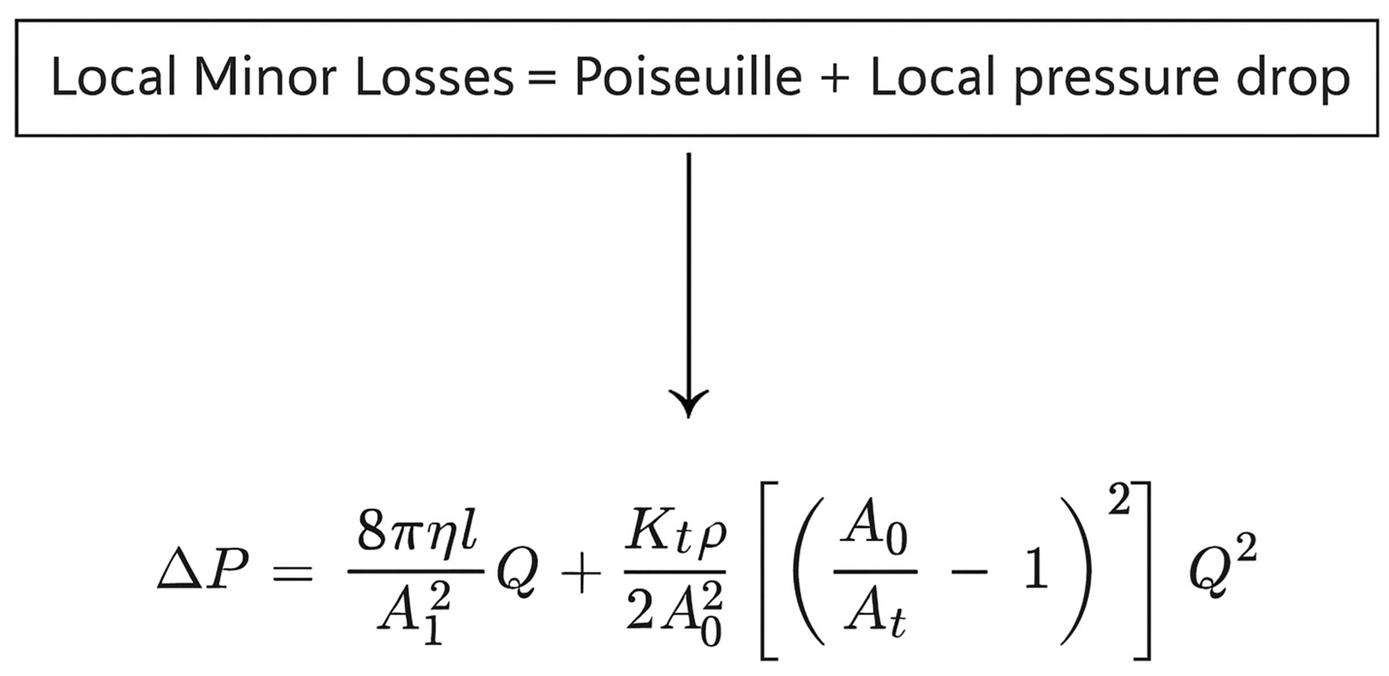

4.3. Fundamentals of Fluid Mechanics

4.4. Biological Analysis and Future Clinical Applicability

4.5. Physical Analysis and Future Clinical Applicability

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMI | acute myocardial infarction |

| CCP | coronary perfusion pressure |

| CFD | computational fluid dynamics |

| FFR | fraction flow reserve |

| Ht | hematocrit |

| LAD | left anterior descending |

| LCX | left circumflex artery |

| RCA | right coronary artery |

| RCAreal | real right coronary artery |

| WSS | wall shear stress |

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). World Health Organization, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- Krittanawong, C.; Khawaja, M.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Girotra, S.; Rao, S.V. Acute Myocardial Infarction: Etiologies and Mimickers in Young Patients. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2023, 12, e029971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sama, C. , Santucci A., Mastroianni C., et al. Near-fatal acute myocardial infarction in a young patient. Cureus 2022, 14, e32994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, P.A.; Țieranu, M.L.; Piorescu, M.T.L.; Buciu, I.C.; Belu, A.M.; Cureraru, S.I.; Țieranu, E.N.; Moise, G.C.; Istratoaie, O. Myocardical Infarction in Young Adults: Revisiting Risk Factors and Atherothrombotic Pathways. Medicina 2025, 61, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmejian, A.A.; Carpenter, H.J.; Ciofani, J.L.; Gray, B.H.M.; Allahwala, U.K.; Ward, M.; Escaned, J.; Psaltis, P.J.; Bhindi, R. Advances in the Computational Assessment of Disturbed Coronary Flow and Wall Shear Stress: A Contemporary Review. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2024, 13, e037129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasouli-Drakou, V.; Ogurek, I.; Shaikh, T.; Ringor, M.; DiCaro, M.V.; Lei, K. Atherosclerosis: A Comprehensive Review of Molecular Factors and Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Pratico, D.; Lin, L.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Bahijri, S.; Tuomilehto, J.; Ren, J. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: pathophysiology and mechanisms. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Maehara, A.; Lv, R.; Guo, X.; Yang, M.; Mintz, G.S.; Tang, D.; Jia, H.; et al. Role of biomechanical factors in plaque rupture and erosion: insight from intravascular imaging based computational modeling. npj Cardiovasc. Heal. 2025, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-W.; Kim, H.; Singh, A.; Brown, D.L. Prophylactic stenting of vulnerable plaques: pros and cons. EuroIntervention 2024, 20, e278–e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, P. Novel imaging modalities for the identification of vulnerable plaques. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1450252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Song, Y.; Mu, X. The Role of Fluid Mechanics in Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaques: An Up-to-Date Review. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Lv, R.; Maehara, A.; Wang, L.; Gao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhang, X.; et al. Plaque Ruptures Are Related to High Plaque Stress and Strain Conditions: Direct Verification by Using In Vivo OCT Rupture Data and FSI Models. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1617–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Park, J.-K. Modular 3D In Vitro Artery-Mimicking Multichannel System for Recapitulating Vascular Stenosis and Inflammation. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Song, H.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Q.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Jia, D.; Cao, S.; et al. Three-dimensional printing for cardiovascular diseases: from anatomical modeling to dynamic functionality. Biomed. Eng. Online 2020, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jing, B.; Lane, B.A.; Tempestti, J.M.; Padala, M.; Veneziani, A.; Lindsey, B.D. Dynamic Coronary Blood Flow Velocity and Wall Shear Stress Estimation Using Ultrasound in an Ex Vivo Porcine Heart. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2023, 15, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufaro, V.; Torii, R.; Erdogan, E.; Kitslaar, P.; Koo, B.-K.; Rakhit, R.; Karamasis, G.V.; Costa, C.; Serruys, P.; Jones, D.A.; et al. An automated software for real-time quantification of wall shear stress distribution in quantitative coronary angiography data. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 357, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauer, R. Severe Asymptomatic Hypertension: Evaluation and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 95, 492–500. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, M.; Schumacher, H.; Teo, K.K.; Lonn, E.; Mahfoud, F.; E Mann, J.F.; Mancia, G.; Redon, J.; Schmieder, R.; Weber, M.; et al. Achieved diastolic blood pressure and pulse pressure at target systolic blood pressure (120–140 mmHg) and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk patients: results from ONTARGET and TRANSCEND trials. Eur. Hear. J. 2018, 39, 3105–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, D.-Y.; Lee, C.-H.; Ho, M.-Y.; Yeh, J.-K.; Huang, Y.-C.; Lu, Y.-Y.; Chang, C.-Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; et al. Risk Stratification by Coronary Perfusion Pressure in Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction Patients Undergoing Revascularization: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 860346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Vignon-Clementel, I.E.; Coogan, J.S.; Figueroa, C.A.; Jansen, K.E.; Taylor, C.A. Patient-Specific Modeling of Blood Flow and Pressure in Human Coronary Arteries. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 38, 3195–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaan, J.A. Coronary diastolic pressure-flow relation and zero flow pressure explained on the basis of intramyocardial compliance. Circ. Res. 1985, 56, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegehuis, V.E.; Wijntjens, G.W.; Piek, J.J.; van de Hoef, T.P. Fractional Flow Reserve or Coronary Flow Reserve for the Assessment of Myocardial Perfusion: implications of FFR as an imperfect reference standard for myocardial ischemia. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2018, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, D.; Jiang, J.; Xia, L. Effect of microcirculatory dysfunction on coronary hemodynamics: A pilot study based on computational fluid dynamics simulation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 146, 105583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yi, T.; Yang, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, B.; Hong, T.; Liu, Z.; Huo, Y.; et al. Coronary Angiography-Derived Diastolic Pressure Ratio. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 596401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. , Ping J., Yu X., et al. Fractional flow reserve-based 4D hemodynamic simulation of time-resolved blood flow in left anterior descending coronary artery. Clin. Biomech. 2019, 70, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhof, N.; Stergiopulos, N.; Noble, M.I.; Westerhof, B.E. Snapshots of Hemodynamics: An Aid for Clinical Research and Graduate Education, 3rd ed.; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, United States, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P.M.; Sharma, S.D.; Chakraborty, S.; Roy, S. Effects of hematocrit levels on flow structures and stress levels in the healthy and diseased carotid arteries. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 011907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogourani, Z.S.; Alizadeh, A.; Salman, H.M.; Al-Musawi, T.J.; Pasha, P.; Waqas, M.; Ganji, D.D. Numerical investigation of the effect of changes in blood viscosity on parameters hemodynamic blood flow in the left coronary artery with consideration capturing fluid–solid interaction. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 77, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutsianis, E.; Dave, H.; Frauenfelder, T.; Poulikakos, D.; Wildermuth, S.; Turina, M.; Ventikos, Y.; Zund, G. Computational simulation of intracoronary flow based on real coronary geometry☆. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2004, 26, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candreva, A.; De Nisco, G.; Rizzini, M.L.; D’ascenzo, F.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Gallo, D.; Morbiducci, U.; Chiastra, C. Current and Future Applications of Computational Fluid Dynamics in Coronary Artery Disease. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, N.N.; Lee, K.Y.; Lee, S.-W. Uncertainty quantification of computational fluid dynamics-based predictions for fractional flow reserve and wall shear stress of the idealized stenotic coronary. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1164345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, J.J.T.; Brown, B.G.; Bolson, E.L.; Dodge, H.T. Lumen diameter of normal human coronary arteries. Influence of age, sex, anatomic variation, and left ventricular hypertrophy or dilation. Circulation 1992, 86, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, J.J. , Gijsen F.J.H., van der Giessen R.J., et al. Positive remodeling at 3-year follow up is associated with plaque-free coronary wall segment at baseline: a serial IVUS study. Atherosclerosis 2014; 236, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukicevic, A.M.; Çimen, S.; Jagic, N.; Jovicic, G.; Frangi, A.F.; Filipovic, N. Three-dimensional reconstruction and NURBS-based structured meshing of coronary arteries from the conventional X-ray angiography projection images. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, G.; Persson, M.; Adiels, M.; Björnson, E.; Bonander, C.; Ahlström, H.; Alfredsson, J.; Angerås, O.; Berglund, G.; Blomberg, A.; et al. Prevalence of Subclinical Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis in the General Population. Circulation 2021, 144, 916–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, W.A.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Quinones, M.A. Textbook of Clinical Hemodynamics, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchetti, M. “A comparative analysis of transient and steady-state CFD simulations in coronary arteries.” Politecnico di Torino; 2020.

- Schrauwen, J.T.C.; Karanasos, A.; van Ditzhuijzen, N.S.; Aben, J.-P.; van der Steen, A.F.W.; Wentzel, J.J.; Gijsen, F.J.H. Influence of the Accuracy of Angiography-Based Reconstructions on Velocity and Wall Shear Stress Computations in Coronary Bifurcations: A Phantom Study. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0145114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Society of Cardiology. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS). ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2023.

- Samady, H.; Molony, D.S.; Coskun, A.U.; Varshney, A.S.; De Bruyne, B.; Stone, P.H. Risk stratification of coronary plaques using physiologic characteristics by CCTA: Focus on shear stress. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2019, 14, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Hung, O.Y.; Piccinelli, M.; Eshtehardi, P.; Corban, M.T.; Sternheim, D.; Yang, B.; Lefieux, A.; Molony, D.S.; Thompson, E.W.; et al. Low Coronary Wall Shear Stress Is Associated With Severe Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. JACC: Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 11, 2072–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, E.M.J.; De Nisco, G.; Gijsen, F.J.H.; Korteland, S.-A.; van der Steen, A.F.W.; Daemen, J.; Wentzel, J.J. The definition of low wall shear stress and its effect on plaque progression estimation in human coronary arteries. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcha, A.; Gutiérrez, N.G. Sensitivity of coronary hemodynamics to vascular structure variations in health and disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourantas, C.V.; Zanchin, T.; Torii, R.; Serruys, P.W.; Karagiannis, A.; Ramasamy, A.; Safi, H.; Coskun, A.U.; Koning, G.; Onuma, Y.; et al. Shear Stress Estimated by Quantitative Coronary Angiography Predicts Plaques Prone to Progress and Cause Events. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, 2206–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.V.O. , Wutzow W.W., Costa A.M.S. Modelagem, simulação e análise de esforços hemodinâmicos em um vaso sanguíneo com aterosclerose. In: Anais do XI EPCC – Encontro Internacional de Produção Científica. Maringá (PR): UniCesumar; 2019. ISSN 2594-4991. ISBN 978-85-459-1960-5.

- Alamir, S.H.; Tufaro, V.; Trilli, M.; Kitslaar, P.; Mathur, A.; Baumbach, A.; Jacob, J.; Bourantas, C.V.; Torii, R. Rapid prediction of wall shear stress in stenosed coronary arteries based on deep learning. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1360330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogen, I.J.v.D.; Schultz, J.; Kuneman, J.H.; A de Graaf, M.; Kamperidis, V.; Broersen, A.; Jukema, J.W.; Sakellarios, A.; Nikopoulos, S.; Kyriakidis, S.; et al. Detailed behaviour of endothelial wall shear stress across coronary lesions from non-invasive imaging with coronary computed tomography angiography. Eur. Hear. J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, 1708–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nisco, G.; Rizzini, M.L.; Verardi, R.; Chiastra, C.; Candreva, A.; De Ferrari, G.; D'Ascenzo, F.; Gallo, D.; Morbiducci, U. Modelling blood flow in coronary arteries: Newtonian or shear-thinning non-Newtonian rheology? Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 242, 107823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G. , Pedicino D., Chiastra C., et al. Coronary artery plaque rupture and erosion: role of wall shear stress profiling and biological patterns in acute coronary syndromes. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 370, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Cao, H.; Jin, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Budoff, M.; Jiang, H.; Ren, J. Correlation analysis of hematocrit level and coronary heart disease in patients with chest pain: a case-control study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2025, 17, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorlie, P.D.; Garcia-Palmieri, M.R.; Costas, R.; Havlik, R.J. Hematocrit and risk of coronary heart disease: the Puerto Rico Heart Health Program. Am. Hear. J. 1981, 101, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, S.E.; Butcher, J.T.; Vignon-Clementel, I.E. Cohort-based multiscale analysis of hemodynamic-driven growth and remodeling of the embryonic pharyngeal arch arteries. Development 2018, 145, dev162578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reneman, R.S.; Hoeks, A.P.G. Wall shear stress as measured in vivo: consequences for the design of the arterial system. Med Biol. Eng. Comput. 2008, 46, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner, M.J.; Casey, D.P. Regulation of Increased Blood Flow (Hyperemia) to Muscles During Exercise: A Hierarchy of Competing Physiological Needs. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 549–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manton, M.J. Low Reynolds number flow in slowly varying axisymmetric tubes. J. Fluid Mech. 1971, 49, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microvascular Research. Flow resistance. In: Topics in Medicine & Dentistry. Elsevier; 2007. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/flow-resistancee.

- Dawson, L.P.; Layland, J. High-Risk Coronary Plaque Features: A Narrative Review. Cardiol. Ther. 2022, 11, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerlekar, N.; Brown, A.J.; Muthalaly, R.G.; Talman, A.; Hettige, T.; Cameron, J.D.; Wong, D.T.L. Association of Epicardial Adipose Tissue and High-Risk Plaque Characteristics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2017, 6, e006379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, C.S.; Bennett, S.; Holroyd, E.; Satchithananda, D.; Borovac, J.A.; Will, M.; Schwarz, K.; Lip, G.Y.H. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome who present with atypical symptoms: a systematic review, pooled analysis and meta-analysis. Coron. Artery Dis. 2024, 36, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).