1. Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a complex, multidomain variable construct that represents the patient’s overall perception of the impact of an illness and its treatment [

1,

2]. Myelodysplastic neoplasms (MDS) are clonal diseases characterised by ineffective haematopoiesis leading to peripheral blood cytopenias and an increased risk of progression to acute myeloid leukaemia [

3].

MDS predominate in the elderly with a median age of diagnosis above 70 years old [

4]. In clinical practice, a cutoff of 3.5 for the Revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R) score defines 2 distinct risk groups: lower-risk MDS (score ≤3.5, median survival 5.9 years) and higher-risk MDS (score >3.5, median survival 1.5 years) [

5]. This risk stratification has been the basis of a patient-centred approach to the management of MDS that aims to improve cytopenias for patients with lower-risk disease and to prevent or delay progression to AML for higher-risk patients. Currently, several treatment options are available for patients with MDS: hypomethylating agents (e.g., azacytidine), hematopoietic stimulating agents (e.g., erythropoietin, G-CSF, luspatercept), supportive care (e.g., blood and platelet transfusions, antibiotics), immunomodulatory agents (e.g., lenalidomide, cyclosporine), low-dose or intensive chemotherapy, iron overload chelation (deferasirox) [

6,

7]. However, at present, the only curative treatment for MDS is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT), an option for a limited number of younger and fit MDS patients either higher risk or with significant cytopenias [

8]. Thus, maintaining/improving HRQoL is one of the main goals of treatment both for lower and higher risk MDS patients [

9].

There are many factors related to MDS and unmet needs that may impact QoL of patients and their caregivers. Since patients with MDS are typically elderly, they often present with one or more comorbidities at the time of diagnosis which can contribute significantly to their HRQoL [

10,

11]. However, the proportion of problems in usual activities, as limitations in mobility, self-care, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression are significantly higher in MDS patients in comparison to age- and sex-matched peers [

12].

Several factors contribute to this, including the need for blood transfusions and frequent hospital visits in patients with anemia, as well as complications like infections and bleeding due to neutropenia and thrombocytopenia [

13,

14]. Among the most prominent symptoms of MDS is fatigue, which is noteworthy as it can only be assessed through patient self-reporting [

15]. Fatigue includes a range of symptoms, such as physical weakness, lethargy, and diminished mental alertness. These issues can profoundly affect both life expectancy and quality of life (QoL) [

5,

12,

16]. However, fatigue is not entirely correlated with hemoglobin levels [

17]. Beyond physical symptoms, HRQoL in MDS patients is also shaped by psychosocial and emotional factors, including limited communication with physicians, lack of understanding about the disease, fear of progression to acute leukemia, and anxiety about mortality. In addition, MDS patients often need a caregiver to support them, whose life can be affected by this role [

18].

We performed a national Italian survey to explore the impact of MDS on patients and caregivers across different aspects of everyday life. Moreover, we aimed to explore patient reported outcomes (PROs) through validated measures. Finally, this survey collected patients’ preferences and unmet needs in Italy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The survey was promoted by the Associazione Italiana Pazienti Sindromi Mielodisplastica (AIPaSiM) advocacy group from June 2022 to May 2024 in 46 different hematology centers in Italy. The survey was available online and distributed also in paper version to patients attending the centers. It included items that were identified by hematologists and patients: 60 items relevant to patients and 20 relevant to caregivers. The PRO measures (PROMs), QOL-E and HM-PRO, were included in the survey.

2.2. QOL-E

The QOL-E is the first HRQoL instrument developed and validated specifically for MDS patients [

19]. It consists of 29 items; two of which do not fit into a multi-item scale and assess subjects’ general perception of well-being at the time of the assessment and compares it with that from a month earlier (i.e., Item 1 and Item 2, respectively). The remaining 27 items address the following six domains:

Physical well-being (QOL-FIS): four items (Items 3a–d)

Functional well-being (QOL-FUN): three items (Items 4a–b and Item 5)

Social and family life (QOL-SOC): four items (Items 6a–c and Item 7)

Sexual well-being (QOL-SEX): two items (Item 8 and Item 14f)

Fatigue (QOL-FAT): seven items (Item 9, Item 10, Items 11a–d, and Item 12)

MDS-specific disturbances (QOL-SPEC): seven items (Item 13, Items 14a–e, and Item 14g).

Three summary scores could also be derived from these six domains:

General (QOL-GEN): the mean of all domains, except for QOL-SPEC

General (QOL-GENV): the mean of all domains, except for QOL-SPEC and QOL-SEX

QOL-ALL: the mean of QOL-GEN and QOL-SPEC

QOL-ALLV: the mean of QOL-GEN and QOL-SPEC, except for QOL-SEX

Treatment Outcome Index (QOL-TOI): the mean of QOL-FIS, QOL-FUN, and QOL-SPEC

Each domain or summary score of the QOL-E questionnaire is scored using a standardized scale with a possible range of 0 to 100. A higher score indicates better health or lower symptomology for that domain or summary score (i.e., lower scores reflect worse outcomes).

2.3. HM-PRO

The HM-PRO (Hematological Malignancy-Patient Reported Outcomes) is a validated patient-reported outcome tool designed specifically to assess the impact of haematological malignancies such as MDS, leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma, on patients’ HRQoL and symptoms [

20,

21,

22,

23]. It consists of two parts, assessing impact (Part A) and signs and symptoms (Part B) of hematological malignancies. Part A has a total of 24 items in four domains: physical behaviour (7); social behaviour (3); emotional behaviour (11); and eating and drinking habits (3). Patients’ responses are recorded on a three-point Likert scale (Not at all, A little, A lot) and “not applicable” as a separate response option.

Part B consists of 18 items in a single domain and the responses are captured on a three-point severity Likert scale (Not at all, Mild, Severe). The scales have linear scoring systems ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing greater (negative) impact (worse outcomes) on QoL and symptom burden.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The median value and interquartile range were used for reporting continuous variables, the absolute and relative frequency were reported for categorical variables.

Comparisons between groups were performed using Fisher’s exact test, the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test or Wilcoxon’s two-sample test as appropriate, and Student’s two-sample t test for normal continuous variables.

The consistency of the QOL-E items was evaluated through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS Software for Windows (version 13, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

From June 2022 to May 2023, 259 patients and 105 caregivers completed the survey.

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A summary of the main patient characteristics is presented in

Table 1. Median age of the patients was 73 years (IQR: 64-79) and 56% were female. MDS disease duration was less than 1 year for 45 patients (18%), 1-2 years for 59 patients (24%), 2-5 years for 73 patients (30%) and over 5 years for 69 patients (28%).

Data on treatment was available for 244 patients. One hundred and sixty-seven patients (70%) were receiving treatment: 100 (41%) with recombinant erythropoietin, luspatercept, lenalidomide, danazol or eltrombopag for lower risk MDS and 53 (22%) with azacytidine or chemotherapy for higher risk MDS. Five patients (2%) received an allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, and 11 patients (5%) did not know what the ongoing treatment was. Overall, 97 patients (42%) received regular red blood cell transfusions.

MDS affected work life in 20% (N=53) of patients, leading to changes in job type (N=3) or working hours (N=25) or to retirement/activity stop (N=25). At the time of the survey, only 60 patients (23%) were still working.

It is worth noting that almost half of all patients (N=118; 48%) needed a caregiver to accompany them to hospital. Fifty-five patients (21.5%) lived in a different area (N=41) or in a different region (N=14) from the treating hematological center. Overall, for 107 patients (45%), travelling to hospital was claimed as being distressful in terms of physical and economic burden and impacted on family members and work.

3.2. PROM QOL-E and HM-PRO

A total of 211 patients responded to QOL-E and HM-PRO questionnaires, although some patients only answered part of the questions. Median scores across all domains are reported in

Table 2.

MDS affected different domains of everyday life of patients; particularly fatigue (median score of 76.2), sexual and functional domains (median scores of 66.6 for both)

Table 2. For instance, 47% of patients found it difficult to work or study and 47% to go on holiday, 56% felt distressed and 66% anxious, and 60% worried about their treatment.

3.3. Impact of Distance from Hospital and Time Spent in Hospital on HRQoL

A total of 114 patients (63%), reported that their dependence on hospital, physicians or nurses disturbed their everyday life.

For 107 patients (45%), travelling to hospital was claimed as being distressful. In this group there were more patients living distant from hospital (32% vs 13% p 0.002), needing a family member, volunteer or a friend to go to the treating center (63% vs 36%, p<0.001) and receiving transfusions (53.5% vs 35%, p=0.006) compared to the remaining 55%.

Comparing PROMs of these patients to the others, distress was associated with significantly worse median HM-PRO physical (PB, 53.5 vs 21.4, p<0.001), emotional (EB, 56.8 vs 31.8, p<0.001), social (SB, 66 vs 50, p<0.001), eating and drinking habits (ED, 25 vs 25, p<0.001), Part A (56.0 vs 26.6, p<0.001) and Part B symptom score (SS, 20.6 vs 8.8, p<0.001) and QOL-E physical (Ph, 50.0 vs 62.5, p<0.001), functional (Fun, 22.2 vs 88.8, p<0.001), social (Soc, 25.0 vs 75.0, p<0.001), fatigue (Fat, 64.3 vs 80.9, p<0.001), general (Gen, 46.7 vs 72.1, p=0.003), MDS specific (MDSS, 44.04 vs 73.8, p<0.001) and treatment-outcome index scores (TOI, 38.2 vs 69.8, p<0.001) (

Table 3).

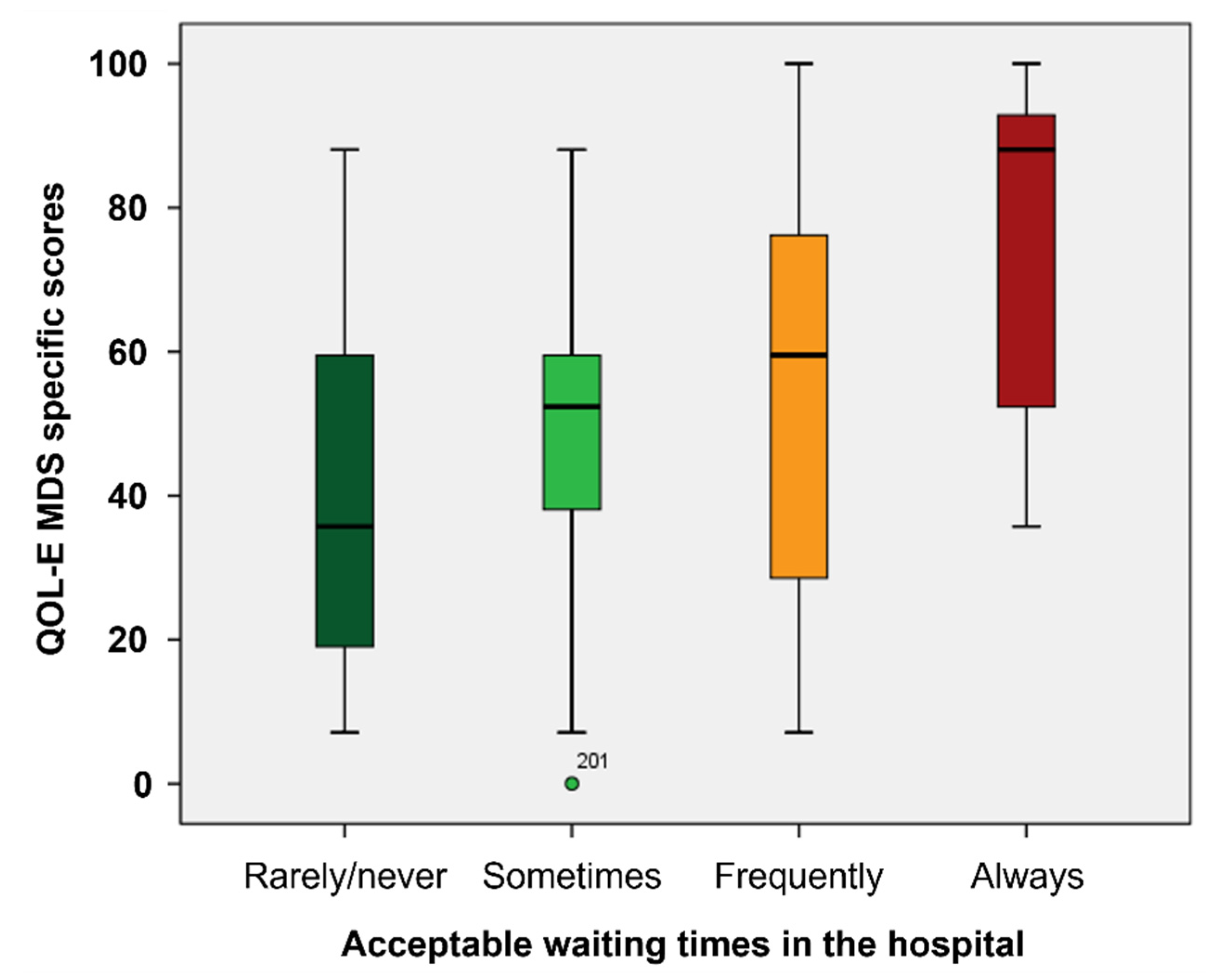

Moreover, waiting times in hospital was unacceptable for 87 patients (37%), who in fact had worse median scores in HM-PRO EB (p<0.001), Part A (p=0.020) and SS scores (p=0.002), and QOL-E Fun (p=0.004), Fat (p<0.001), Ses (p=0.018) MDSS (p=0.001), Gen (p=0.030) and TOI (p=0.003) (

Figure 1,

Supplementary Table S1).

Telemedicine communication was preferred in 54% of cases, particularly if reaching hospital was distressful (62% yes vs 45% no, p=0.035).

3.4. Impact of Treatment and Transfusion on HRQoL

PROM scores were not significantly different across the different treatment groups. Only 18% of patients felt that treatment impacted negatively on everyday life, and this aspect was independent from the type of treatment but was associated with red blood cell transfusion dependency. Overall, receiving regular transfusions impacted negatively on HRQoL (

Table 4), and 47% felt that transfusion dependence affected their everyday life.

Indeed, for 70% (49/70) of transfusion-dependent patients treatment impacted negatively on everyday life as compared to 49% (46/94) of transfusion-independent patients, p=0.011 and had significantly worse scores across all domains of QOL-E and HM -Pro (

Supplementary Table S2).

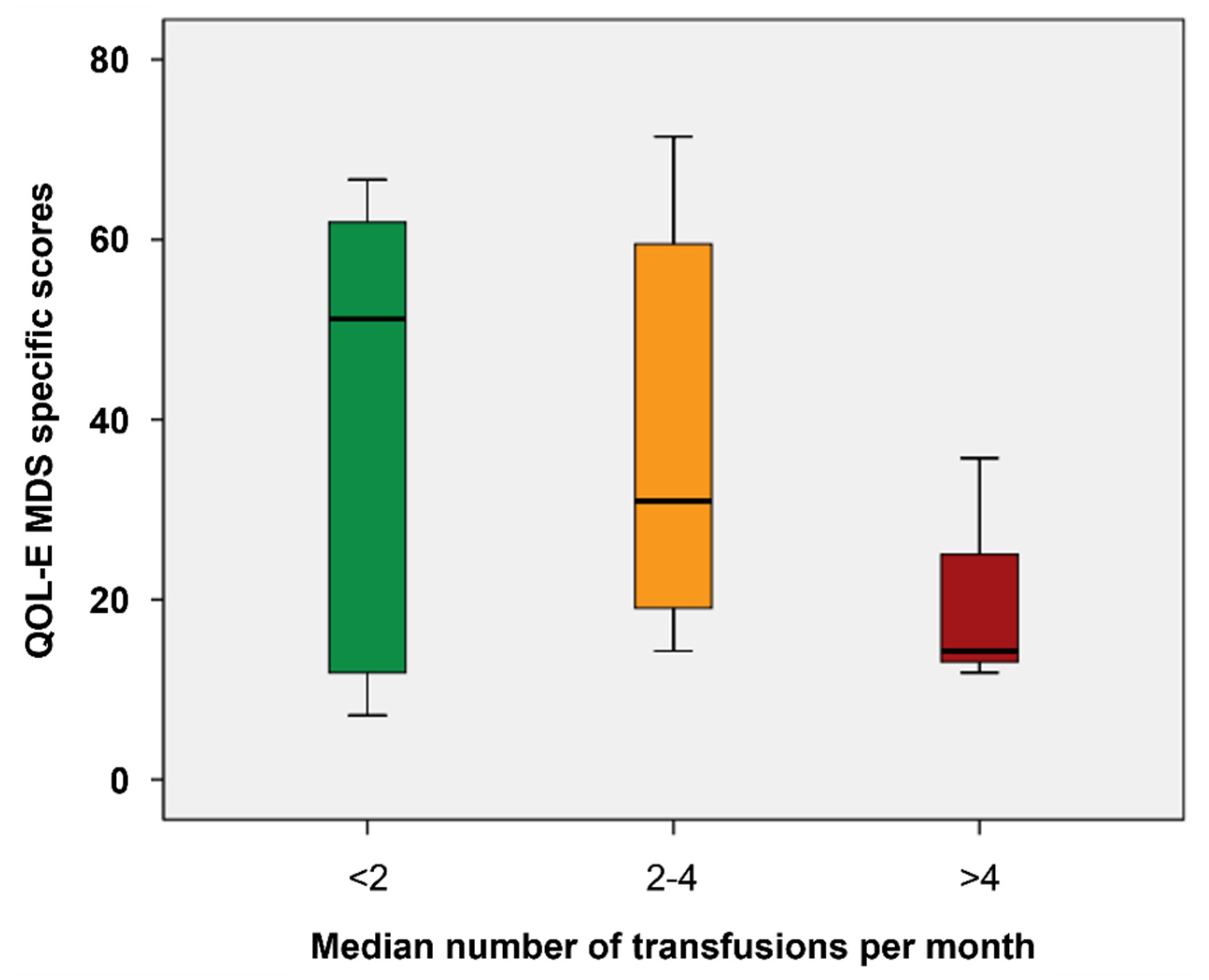

Moreover, the increasing frequency of transfusions was associated with worse HM-PB (p=0.037), SB (p=0.038) and part A scores (p=0.029) and QOL-E Soc (p=0.012), Fat (p= 0.034), MDSS (p=0.002) and Gen scores (p=0.049) (

Figure 2).

Only 2 patients received transfusions at home but 38% (N 30) would prefer receiving transfusions at home (77% of those with distress reaching the hospital and 20% of those far from treating center) and had worse PROM scores (

Table 4). QOL-E and HM-PRO scores for patients preferred place to undertake transfusions are summarized in

Table 5.

Thirty-five patients (17%) felt to be a burden for their family and had lower QOL-E and higher HM scores across all domains (p<0.001) (

Supplementary Table S3). In this sub-group, there were more transfusion-dependent patients (61% vs 35% p=0.026), more patients for whom MDS impacted on work life (36% vs 21%, p=0.013) and more patients needing a caregiver (39% vs 17% p=0.006).

3.5. Work life

Retired patients had worse PROM median scores: QOL-E Fis (p=0.014) soc (p=0.030) Gen (p=0.043), all (p=0.040) and TOI (p=0.012); HM-PRO PB (p=0.005), SW (p <0.001) and PART A (p=0.001).

Ninety-seven percent of patients whose work-life was affected by MDS reported in QOL E that fatigue interfered with their daily activity.

3.6. Patients’ Preferences and Communication with Physician

For 18% of patients (N=43), the communication of diagnosis was incomplete and for 38% (N=92) partially understood or misunderstood. Twenty-four percent of patients (N=50) were not satisfied with communication of their treatment program, expected side-effects and looked for information on websites (34%) or from other doctors (30%). On the other hand, 85% of patients were satisfied with nurse’s support.

The worst aspect of their treatment journey was waste of time for 37% of patients (N=86) and hospital disorganization for 20% (N=46).

The most important unmet needs reported by patients for escalation to the authorities were access to new medicines for 35%, faster access to treatments for 33%, and being treated in their own area for 12%. Other unmet needs were comprehension of diagnosis for 15% and treatment options for 21%

3.7. Caregivers

Thirty-six percent of the patients who responded to the survey had a caregiver.

One hundred and five caregivers, of which 94% family members (35% partner and 59% other family component) and 80% females completed the survey. The median age of caregivers was 56 years (IQ range 48-64) and 53% were still working.

The caregiver’s work life was largely affected by their role leading to a change in type of job (29% of cases), or working hours (30%) or to work discontinuation (14%). On a scale 0-10 on the impact on work-life, family caregivers scored median 4 (interquartile range 2-6).

4. Discussion

This national survey of MDS patients and their caregivers offers valuable insights into the disease burden and its profound impact on HRQoL. Using two validated questionnaires, the QOL-E and HM-PRO, this study highlights several key areas that affect HRQoL in MDS patients, including fatigue, transfusion dependency, and emotional well-being, as well as the significant impact on caregivers’ QoL. These findings corroborate with results from recent studies that highlight the complex relationship between physical symptoms, emotional distress, and the practical burdens associated with chronic disease management.

Patients with MDS in this study were elderly (median of 73 years), 42% were transfusion dependent and therefore also dependent (in 48% of cases) on caregivers to accompany them to the hospital

Fatigue was identified as a major factor in reducing HRQoL, with over 76% of patients in the study reporting it as a significant problem. This finding is consistent with other studies [

24,

25,

26], including a study by Efficace et al. that investigated factors associated with fatigue severity in 280 newly diagnosed higher-risk MDS patients [

27]. In that study, Fatigue severity strongly impacted upon overall QoL, particularly in women. Another study by Escalante and colleagues based in the USA evaluated fatigue, symptom burden, and health-related QoL in 303 patients including 145 MDS [

26]. In the MDS group of patient’s severe fatigue was reported, with a mean fatigue score (FACT-F questionnaire) of 25 (i.e., severe). The average QoL score (FACT-G questionnaire) was 69. Common strategies for managing fatigue included conserving energy, physical activity, and naps. Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of these strategies in improving outcomes for MDS patients.

Another key finding that emerged from our study was the significant degree of emotional distress experienced by MDS patients, with 66% reporting anxiety related to their disease and treatment. This is consistent with recent literature that emphasizes the psychosocial impact of MDS [

28]. In addition, a large-scale study by Stauder and colleagues revealed that patients experience significant impairments in HRQoL, particularly in pain/discomfort, mobility, anxiety/depression, and usual activities [

28]. These limitations were more pronounced in older individuals, females, and those with high co-morbidity, low hemoglobin, or transfusion needs, compared to age- and sex-matched norms.

Transfusion dependency is considered a major factor that negatively impacts HRQoL. In this study, 42% of patients were dependent on regular red blood cell transfusions, and these patients reported significantly worse outcomes across multiple HRQoL domains. This finding is supported by other studies showing the impact of transfusion dependency on HRQoL [

29]. Fenaux et al. demonstrated that transfusion dependency is associated with increased fatigue, reduced physical function, and greater emotional distress [

30]. Novel therapies such as luspatercept and imetelstat, which have been shown to reduce transfusion needs, have shown to improve QoL [

31].

Our findings also highlighted the importance placed on caregivers, many of whom experienced significant disruptions to their work and personal lives. Almost half (48%) of patients required assistance from caregivers for hospital visits, and caregivers reported high levels of stress and emotional strain. This is consistent with recent studies that have examined the impact of caregiving in hematologic malignancies including MDS [

25,

32,

33].

A large real-world study combined surveys with patient chart reviews from 1,445 patients to document real-world clinical practice and burden of MDS clinical practice [

25]. It found discrepancies between patient and physician reports on symptoms and QoL, with patients reporting higher fatigue and symptom frequency. Caregiver burden was also underestimated by physicians. The findings highlight the need for improved therapeutic strategies and better communication between patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers to enhance MDS management and QoL. Addressing caregiver needs, including providing and support for managing the logistical and emotional challenges of caregiving, is essential to improving the overall care experience for MDS patients.

One of the most striking findings of our study was the significant distress caused by hospital visits and waiting times, with 37% of patients reporting dissatisfaction with the amount of time spent in hospital. These logistical challenges were associated with worse HRQoL outcomes, particularly in patients who had to travel long distances or rely on caregivers for transportation. This finding is in line with several studies that the physical and economic burden of frequent hospital visits can significantly contribute to patient and caregiver distress [

34,

35,

36]. Telemedicine and home-based care options could help alleviate these burdens, particularly for patients who live far from treatment centers.

A recent study by LoCastro and colleagues assessed the feasibility and usability of a telehealth-delivered Serious Illness Care Program for patients with acute myeloid leukemia and MDS [

37]. With a 95% retention rate and usability scores averaging 5.9/7, the program was well-received. Most participants found it valuable, reporting enhanced closeness with clinicians and alignment in curability and life expectancy estimates. Furthermore, 89.5% of patients would recommend the telehealth program, demonstrating its acceptability and promise for wider use.

In terms of treatment burden, only 18% of patients felt that their current treatment had a negative impact on their everyday life. This finding is somewhat surprising, given the high level of physical and emotional distress reported by patients regarding the impact of transfusion. However, it may reflect the fact that many patients are on supportive therapies, such as erythropoiesis-stimulating agents or low-intensity chemotherapy, which are generally well-tolerated. Nonetheless, the negative impact of transfusion dependency on HRQoL suggests that efforts to reduce the need for transfusions, either through more effective anemia management or through the development of novel therapies, should remain a key focus in MDS treatment [

13,

38,

39].

5. Study Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the impact that MDS has on patients and their caregivers, several limitations need to be highlighted. First, the survey design may introduce response bias, as patients who are more engaged in their care may be more likely to participate. Second, the use of PROs inherently involves subjective assessments, which may vary between individuals and may not fully capture the complexity of disease burden. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to assess changes in HRQoL over time. Future longitudinal studies will be essential for tracking how HRQoL evolves with disease progression and treatment.

6. Conclusions

This Italian study emphasizes the significant challenges faced by patients with MDS and their caregivers. The emotional and economic burden of frequent hospital visits, long waiting times, and transfusion dependency negatively impacts QoL for both groups. Fatigue, distress, and the high frequency of transfusions are major factors contributing to worse QoL for patients. This study highlights the importance of improving communication regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment options, while also identifying unmet needs that influence patient care. To address these issues, there is a need for interventions that reduce transfusion requirements, enable treatment at home, and improve access to novel therapies. Telemedicine and strategies to alleviate the logistical burden of hospital visits could further enhance patients’ HRQoL and support caregivers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary Table S1. QOL-E and HM -PRO scores according to acceptable waiting time in hospital; Supplementary Table S2. QOL-E and HM-PRO scores according to negative impact of treatment on everyday life; Supplementary Table S3. QOL-E and HM -PRO scores according to patients feeling to be a burden for their family.

Author Contributions

EC and ENO designed the study, analyzed data and wrote the paper. AN contributed to study design, and promoted the survey to AIPASIm patients; SS and TI contributed to study design and interpretation of results. All other authors promoted the survey to their patients and reviewed the paper.

Funding

This research was funded by AIPASIM.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Colin Gerard Egan, PhD (CE Medical Writing SRLS, Pisa, Italy).

Conflicts of Interest

ENO; consultancy fees from BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Alexion and Sobi and royalties from Ryvu, Halix Therapeutics, Servier. VG; has received consultancy fees from Novartis, Sobi, Alexion, Incyte and Pfizer. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIPaSiM |

Associazione italiana pazienti sindromi mielodisplastica |

| alloHSCT |

allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells transplantation |

| HM-PRO |

Hematological malignancy-patient reported outcomes |

| HRQoL |

Health-related quality of life |

| HSTC |

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| IPSS-R |

Revised international prognostic scoring system |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| MDS |

Myelodysplastic neoplasms |

| MDSS |

MDS specific |

| PRO |

patient reported outcome |

| PROM |

PRO measure |

| QOL-E |

HRQoL instrument developed specifically for MDS patients |

References

- Gorodokin, G.I.; Novik, A.A. Quality of Cancer Care. Ann Oncol 2005, 16, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. Health Care Rationing: The Public’s Debate. BMJ 1996, 312, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.-M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating Morphologic, Clinical, and Genomic Data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekeres, M.A. Epidemiology, Natural History, and Practice Patterns of Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes in 2010. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2011, 9, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, P.L.; Tuechler, H.; Schanz, J.; Sanz, G.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Solé, F.; Bennett, J.M.; Bowen, D.; Fenaux, P.; Dreyfus, F.; et al. Revised International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Blood 2012, 120, 2454–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewersdorf, J.P.; Carraway, H.; Prebet, T. Emerging Treatment Options for Patients with High-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Ther Adv Hematol 2020, 11, 2040620720955006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karel, D.; Valburg, C.; Woddor, N.; Nava, V.E.; Aggarwal, A. Myelodysplastic Neoplasms (MDS): The Current and Future Treatment Landscape. Current Oncology 2024, 31, 1971–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Witte, T.; Bowen, D.; Robin, M.; Malcovati, L.; Niederwieser, D.; Yakoub-Agha, I.; Mufti, G.J.; Fenaux, P.; Sanz, G.; Martino, R.; et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for MDS and CMML: Recommendations from an International Expert Panel. Blood 2017, 129, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.N.; Platzbecker, U.; Fenaux, P.; Garcia-Manero, G.; LeBlanc, T.W.; Patel, B.J.; Kubasch, A.S.; Sekeres, M.A. Targeting Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes – Current Knowledge and Lessons to Be Learned. Blood Reviews 2021, 50, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.N.; Finelli, C.; Santini, V.; Poloni, A.; Liso, V.; Cilloni, D.; Impera, S.; Terenzi, A.; Levis, A.; Cortelezzi, A.; et al. Quality of Life and Physicians’ Perception in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Am J Blood Res 2012, 2, 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- Stojkov, I.; Conrads-Frank, A.; Rochau, U.; Arvandi, M.; Koinig, K.A.; Schomaker, M.; Mittelman, M.; Fenaux, P.; Bowen, D.; Sanz, G.F.; et al. Determinants of Low Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes: EUMDS Registry Study. Blood Adv 2023, 7, 2772–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauder, R.; Yu, G.; Koinig, K.A.; Bagguley, T.; Fenaux, P.; Symeonidis, A.; Sanz, G.; Cermak, J.; Mittelman, M.; Hellström-Lindberg, E.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Lower-Risk MDS Patients Compared with Age- and Sex-Matched Reference Populations: A European LeukemiaNet Study. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzbecker, U.; Kubasch, A.S.; Homer-Bouthiette, C.; Prebet, T. Current Challenges and Unmet Medical Needs in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Leukemia 2021, 35, 2182–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakar, S.; Gabarin, N.; Gupta, A.; Radford, M.; Warkentin, T.E.; Arnold, D.M. Anemia-Induced Bleeding in Patients with Platelet Disorders. Transfus Med Rev 2021, 35, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caocci, G.; Baccoli, R.; Ledda, A.; Littera, R.; La Nasa, G. A Mathematical Model for the Evaluation of Amplitude of Hemoglobin Fluctuations in Elderly Anemic Patients Affected by Myelodysplastic Syndromes: Correlation with Quality of Life and Fatigue. Leuk Res 2007, 31, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcovati, L.; Della Porta, M.G.; Strupp, C.; Ambaglio, I.; Kuendgen, A.; Nachtkamp, K.; Travaglino, E.; Invernizzi, R.; Pascutto, C.; Lazzarino, M.; et al. Impact of the Degree of Anemia on the Outcome of Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Its Integration into the WHO Classification-Based Prognostic Scoring System (WPSS). Haematologica 2011, 96, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efficace, F.; Gaidano, G.; Breccia, M.; Criscuolo, M.; Cottone, F.; Caocci, G.; Bowen, D.; Lübbert, M.; Angelucci, E.; Stauder, R.; et al. Prevalence, Severity and Correlates of Fatigue in Newly Diagnosed Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Br J Haematol 2015, 168, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.L. The Impact of Myelodysplastic Syndromes on Quality of Life: Lessons Learned from 70 Voices. J Support Oncol 2012, 10, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.; Nobile, F.; Dimitrov, B. Development and Validation of QOL-E© Instrument for the Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Central European Journal of Medicine 2013, 8, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Oliva, E.N.; Ionova, T.; Else, R.; Kell, J.; Fielding, A.K.; Jennings, D.M.; Karakantza, M.; Al-Ismail, S.; Collins, G.P.; et al. Hematological Malignancy Specific Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (HM-PRO): Construct Validity Study. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Oliva, E.N.; Ionova, T.; Else, R.; Kell, J.; Fielding, A.K.; Jennings, D.M.; Karakantza, M.; Al-Ismail, S.; Lyness, J.; et al. Paper and Electronic Versions of HM-PRO, a Novel Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Hematology: An Equivalence Study. J Comp Eff Res 2019, 8, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, P.; Oliva, E.N.; Ionova, T.; Salek, S. Responsiveness and the Minimal Clinically Important Difference for HM-PRO in Patients with Hematological Malignancies. Blood 2018, 132, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Oliva, E.N.; Ionova, T.; Else, R.; Kell, J.; Fielding, A.K.; Jennings, D.M.; Karakantza, M.; Al-Ismail, S.; Collins, G.P.; et al. Development of a Novel Hematological Malignancy Specific Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (HM-PRO): Content Validity. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownstein, C.G.; Daguenet, E.; Guyotat, D.; Millet, G.Y. Chronic Fatigue in Myelodysplastic Syndromes: Looking beyond Anemia. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2020, 154, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Williamson, M.; Brown, E.; Trenholm, E.; Hogea, C. Real-World Study of the Burden of Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Patients and Their Caregivers in Europe and the United States. Oncol Ther 2024, 12, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escalante, C.P.; Chisolm, S.; Song, J.; Richardson, M.; Salkeld, E.; Aoki, E.; Garcia-Manero, G. Fatigue, Symptom Burden, and Health-related Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome, Aplastic Anemia, and Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria. Cancer Med 2019, 8, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efficace, F.; Gaidano, G.; Breccia, M.; Criscuolo, M.; Cottone, F.; Caocci, G.; Bowen, D.; Lübbert, M.; Angelucci, E.; Stauder, R.; et al. Prevalence, Severity and Correlates of Fatigue in Newly Diagnosed Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Br J Haematol 2015, 168, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauder, R.; Yu, G.; Koinig, K.A.; Bagguley, T.; Fenaux, P.; Symeonidis, A.; Sanz, G.; Cermak, J.; Mittelman, M.; Hellström-Lindberg, E.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Lower-Risk MDS Patients Compared with Age- and Sex-Matched Reference Populations: A European LeukemiaNet Study. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andritsos, L.A.; McBride, A.; Tang, D.; Barghout, V.; Zanardo, E.; Song, R.; Huynh, L.; Yenikomshian, M.; Makinde, A.Y.; Hughes, C.; et al. Real-World Impact of Luspatercept on Red Blood Cell Transfusions among Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes: A United States Healthcare Claims Database Study. Leukemia Research 2025, 148, 107624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenaux, P.; Platzbecker, U.; Mufti, G.J.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Buckstein, R.; Santini, V.; Díez-Campelo, M.; Finelli, C.; Cazzola, M.; Ilhan, O.; et al. Luspatercept in Patients with Lower-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.N.; Platzbecker, U.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Mufti, G.J.; Santini, V.; Sekeres, M.A.; Komrokji, R.S.; Shetty, J.K.; Tang, D.; Guo, S.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes with Ring Sideroblasts Treated with Luspatercept in the MEDALIST Phase 3 Trial. J Clin Med 2021, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, P.; Olshan, A.; Iraca, T.; Anthony, C.; Wintrich, S.; Sasse, E. Experiences and Support Needs of Caregivers of Patients with Higher-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndrome via Online Bulletin Board in the USA, Canada and UK. Oncol Ther 2024, 12, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soper, J.; Sadek, I.; Urniasz-Lippel, A.; Norton, D.; Ness, M.; Mesa, R. Patient and Caregiver Insights into the Disease Burden of Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2022, 13, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalie Oliva, E.; Santini, V.; Antonella, P.; Liso, V.; Cilloni, D.; Terenzi, A.; Guglielmo, P.; Ghio, R.; Cortelezzi, A.; Semenzato, G.; et al. Quality of Life in Myelodysplastic Syndromes and Physicians’ Perception. Blood 2009, 114, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucioni, C.; Finelli, C.; Mazzi, S.; Oliva, E.N. Costs and Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Am J Blood Res 2013, 3, 246–259. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, V.; Sanna, A.; Bosi, A.; Alimena, G.; Loglisci, G.; Levis, A.; Salvi, F.; Finelli, C.; Clissa, C.; Specchia, G.; et al. An Observational Multicenter Study to Assess the Cost of Illness and Quality of Life in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Italy. Blood 2011, 118, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoCastro, M.; Mortaz-Hedjri, S.; Wang, Y.; Mendler, J.H.; Norton, S.; Bernacki, R.; Carroll, T.; Klepin, H.; Liesveld, J.; Huselton, E.; et al. Telehealth Serious Illness Care Program for Older Adults with Hematologic Malignancies: A Single-Arm Pilot Study. Blood Adv 2023, 7, 7597–7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, A.M.A.; Platzbecker, U. Treatment of Lower-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Haematologica 2025, 110, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzbecker, U. New Approaches for Anemia in MDS. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia 2020, 20, S59–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).