1. Introduction

Historically, the concept of «health» included in itself both body-care and mind-care: the 1948 World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”, referring to the biopsychosocial model. This model attributes the outcome of disease, as well as health, to the intricate and variable interaction of biological factors (genetic, biochemical, etc.), psychological factors (mood, personality, behavior, etc.) and social factors (cultural, family, socioeconomic, etc.). In line with this, it is essential to guarantee and improve the standard of care, also based to the real needs perceived by patients (PTS) and caregivers and to historical and social context, especially in a pandemic period like COVID-19 is in which the functional status can be compromised. The good medical practice in fact can’t be separated from the satisfaction of the PTS’ and their caregivers’ psychological needs.

Caregivers are mostly informal, as relatives and friends, and they help people with cancer during and after treatment. Specifically, they help with daily needs, doing or arranging housework, managing finances, planning for care and services, visiting often and providing emotional support. Less frequently PTS are supported by formal caregivers that are trained professionals and are paid to provide care for a PTS. Approximately 7% of the US population is made up of family caregivers of a loved one with cancer and 4% of the US population is surviving cancer, meaning the ratio of family caregivers to cancer survivors is nearly double, supporting the notion that cancer is not isolated only to the individual diagnosed but rather impacts an entire family unit and network of close friends [

https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2018.html].

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, there has been considerable emphasis placed on the implications for PTS with cancer in terms of their vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 virus in healthcare settings. There is also concern that cancer PTS and cancer survivors are more likely to get infected with the novel coronavirus and are more likely to die from complications of COVID-19 [

1].

Among other cancers, neuro-oncological PTS are often characterized by dismal prognosis: they daily deal with impaired functioning, sensation of uncertain, fear, and difficult medical decisions. The potential neurological deficits lead to a unique symptom profile considerably impairing the PTS themselves and their caregivers in everyday life. PTS can experienced physical limitations, neurocognitive deficits, or speech disorders, resulting into social isolation as well as work or studying interruption or career break. Such context of isolation is then more severe in neuro-oncological PTS compared to oncological ones due to the specifical clinical impairment.

In addition to physical decline and increasing social isolation, PTS may undergo a shattering of preconscious assumptions about their life and its meaning, causing existential anxiety. Then, the development of adaptive strategies to deal with the disease burden is mandatory, both for PTS and caregivers. Coping strategies are a determinant factor in the process of emotional adaptation to the disease, may change over the disease evolution and are influenced by several variables, such as quality of life (QoL), cognitive function, different psychological distress features, clinical condition, and disease awareness [

2,

3]. In addition, such strategies exhibit an important role in the dynamic interplay between the dyad made by the PTS and his/her main caregiver [

4].

In addition, but limited to a few studies, the emotional and social impact on the PTS and their caregivers as the relationship between doctor and PTS change, including the already complex and delicate communication modalities have been addressed [

5,

6,

7]. In parallel, also the clinicians reported the need to understand PTS’ unique experiences, to communicate sensitively and empathically with PTS and their caregivers as to what to expect, and to plan timely and appropriate interventions, within a dynamic real-time perspective from before diagnosis to the exitus [

2]. During pandemic, main reasons of possible relationship modifications between PTS/caregiver and doctors were related to the restrictions on medical facilities such as reduced non-emergency hospitalization and reduced access to physicians, also sourced by PTS reluctant to present because of fear of interacting with others, and sometimes limited to use video or teleconsultations when teleconsultation options were offered [

5,

6,

7].

PTS with malignancies have been described to experience higher rates of distress, anxiety, and depression than the general population, and the slower the course of treatment, the higher the distress would be [

5,

6,

7]. The emotional state of PTS, their perspectives and experiences related to the disease should be not neglected, to promote compliance with treatments. The assessment of the needs and perceptions of PTS and their caregivers appears to be a priority in order to ensure an adequate standard in taking care, especially in a context of collective difficulty as pandemic. In addition, PTS with primary brain tumors have mostly poor prognosis, although the best standard of care is followed.

The main aim of this study is to better understand comprehensive impact on mental health and wellbeing of COVID-pandemic in neuroncological patients and their caregivers. In particular, the specific aims are: I-how COVID-19 affects the neuro-oncological PTS and their caregivers’ emotional state and future perception, II-to explore PTS and their caregivers’ needs, III-the relationship between PTS and medical institution, as well as PTS’ compliance to care, including therapies.

3. Results

3.1. Population

From 250 PTS and 150 caregivers screened, a total of 162 PTS and 66 caregivers older than 18 year-old completed the questionnaire.

The demographic features are reported in the

Table 1.

The most common diagnoses were gliomas 46.05% and meningiomas (25.00%); less common ependimoma (5.26%), medulloblastoma (6.58%), Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma (PCNSL) (1.32%), neurinoma (3.29%) and other (12.50%). Disease duration was < 3 months in 6.17%, 3-6 months in 14.20%, 6-12 months in 9.26%, 1-5 years in 29.01% and >5 years in 41.36%.

The 9.26% of PTS got SARS-CoV-2 infection.

For demographic caregivers’ details see

Table 1 (sex PTS, sex caregivers, age caregivers, nationality caregivers, kinship PTS/caregivers).

The PTS got information about COVID-19 by different sources: general practitioner (37.88%), specialist doctor (16.66%), media (71.97%), web (46.97%), relatives and friends (23.48%). Most of them (77.27%) were satisfied with the information provided.

3.2. Perception of Patient and Their Caregivers: Emotional State and the Future Perception

The 37.50% PTS perceived greater risk of contracting the COVID-19 disease compared to general population, 57.50% the same risk and 5.00% lower risk than general population.

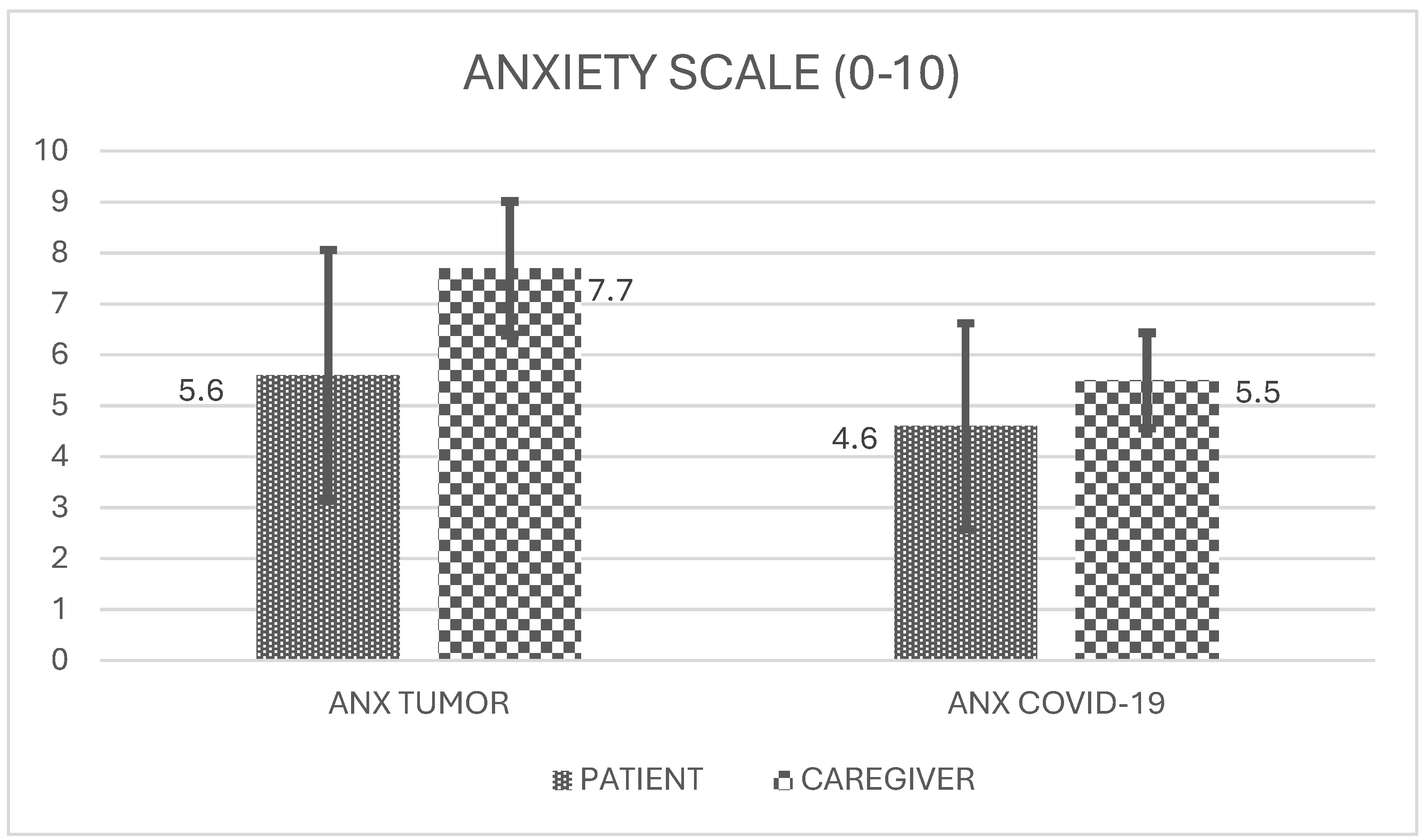

Using a scale 0-10 for assessment of anxiety, PTS experienced 5.8 (standard deviation, sd 2.5) as anxiety level related to tumor and 4.6 (sd 2.2) level about COVID-19 risk (

Figure 1). Caregivers experienced 7.7 (sd 2.3) anxiety level about tumor and 5.5 (sd 2.2) about COVID-19 risk (

Figure 1). No significant correlations were found between PTS and caregivers’ anxiety concerning tumor as well as COVID.

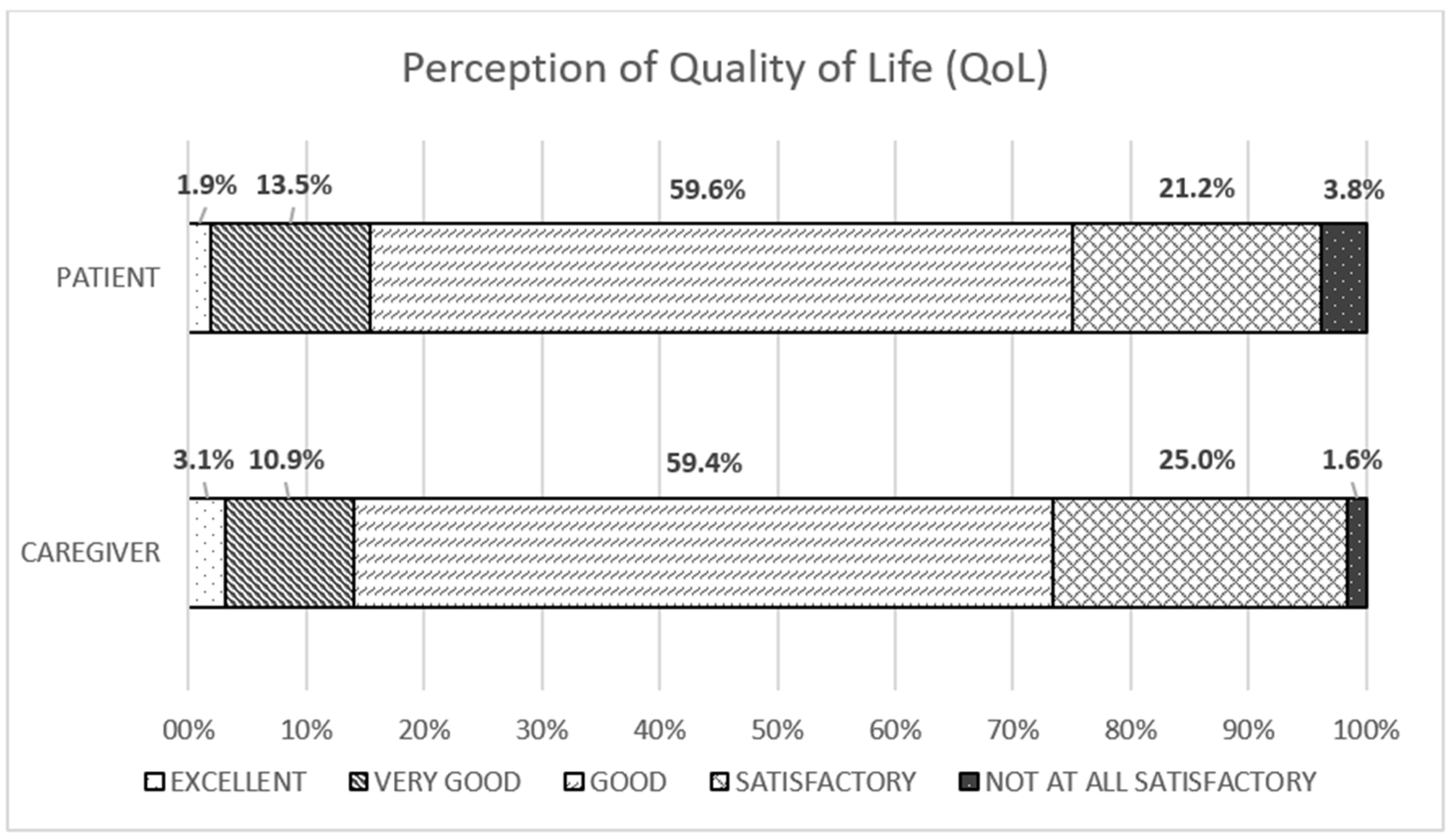

The 75.0% of PTS described at least good QoL; in particular, 1.92% optimal, 13.46% very good and 59.62% good (

Figure 2).

The 65.4% of PTS declared to have sufficient resources to deal with the situation.

There was a weak correlation between QoL and resources in PTS (ρ=0.37, P = 0.000).

The 73.44% caregivers defined their QoL at least as good (3.13% optimal, 10.94% very good and 59.38% good) (

Figure 2); only 22.73% caregivers defined their care burden increased during the pandemic, and care burden did not related with QoL.

There was a weak correlation between PTS and caregiver QoL (ρ=0.31, P=0.0154).

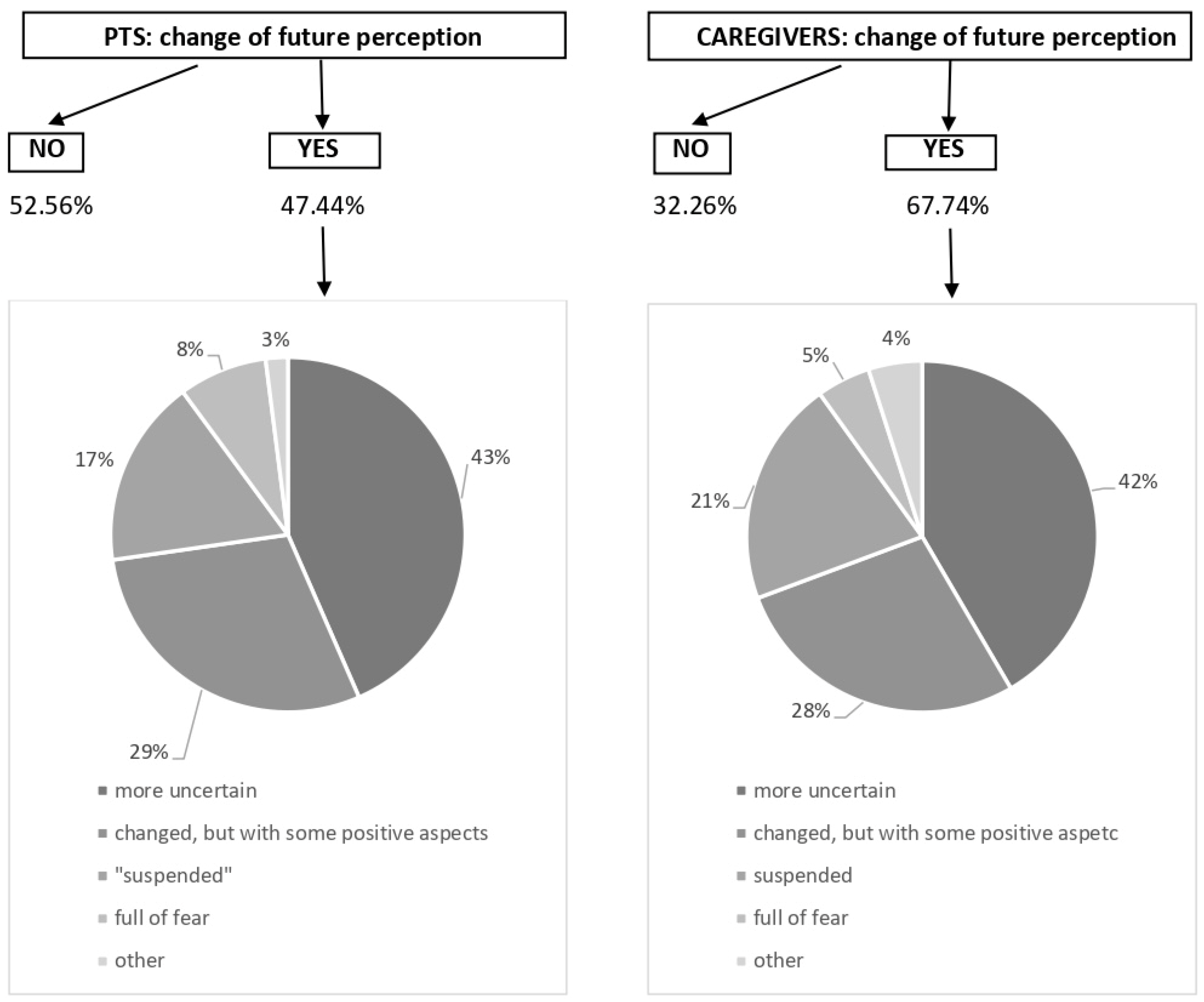

47.44% PTS felt different perception of the future during COVID-19, and now they feel higher sense of uncertainty (43.02%), a sensation of “different future” that they can no specifically further defined (29.07%), feeling of “suspension” (17.44%), fear (8.14%) or others (

Figure 3). In 67.74% of caregivers the perception of the future has been changed, mostly towards greater insecurity (41.86%) (

Figure 3).

COVID-19 pandemic influenced mostly social field (74.83%), and to less extent health and work area (32.65% and 34.01% respectively), psychological sphere (27.89%) and economic sector (21.09%) for PTS cohort. However, the COVID-forced everyday life modification could result into some positive suggestions for future coping strategies, as the ability to cope the emergency (26.54% and 36.36%, PTS and caregivers respectively), higher sense of responsability (45.06% and 53.03%), good technology expertice (21.60% and 28.79%), more attention to the social dimension (35.80% and 37.88%) and to the care of the self (31.48% and 13.64%).

3.3. Relationship with Healthcare Personal and Medical Institution

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 9.15% of PTS decided to delay anti-tumoral therapeutic schedule and 27.85% referred to be worried about going to hospital for consultation. Accordingly, we found a significant association between PTS spontaneous therapy delay and patient-doctor relationship modification (P=0.022, Fisher’s exact test).

Overall, on COVID-19 period, the large part of PTS experienced no changes in treatment timing (81.5%) as well as patient-doctor relationship (81.0%); 93.1% of PTS were satisfied with the treatments received.

4. Discussion

As largely reported, COVID-19 pandemic resulted into cancer care delay in a large type of cancer setting (ASCO survey reported that half of patients with active cancer experienced negative impact on their cancer care

https://www.asco.org/research-data/reports-studies/national-cancer-opinion-survey): in neuro-oncological setting the pandemic has changed treatment schedules and limited investigational treatment options [

8]. However, a mono-institutional study described that cancer delay did not impact on outcome [

9]. In our study mostly of the PTS (81.5%) experienced no changes in treatment timing or cancer care.

On the other side, PTS themselves could choose to differ oncological treatment based on their fear of SARS-CoV-2 exposition. We found that 9.15% of PTS decided to delay anti-tumoral therapeutic schedule and 27.85% referred to be worried about going to hospital for consultation. 9% of PTS refraining from consulting a doctor or visiting the hospital due to fear of contracting the virus in Jeppesen 2021 [

10]. COVID-19 related anxiety could discourage treatment in breast cancer PTS [

11]. To manage such issue as well as to protect PTS from SARS-CoV-2 exposure, we developed a telehealth intervention that provide a safe and easy way for PTS to access their doctors, if applicable [

12].

The emotional impact of COVID-19 is also measured by the perception of SARS-CoV-2 infection risk: the neuro-oncological PTS described higher risk than general population in our study.

Although cancer PTS are regarded as a highly vulnerable population to SARS-CoV-2 infection and development of more severe COVID-19 symptoms in any type of cancer [

13], in our series 9.26% of neuro-oncological PTS got SARS-CoV-2 infection, and this percentage was similar to the general Italian population (10.6% from the COVID pandemic onset to December 2021, from

https://covid19.who.int/region/euro/country/it).

In our cases, anxiety related to tumor is higher than COVID-related anxiety. Similar results were described by Binswanger that measured the distress thermometer, reporting the highest score for disease-correlation versus COVID-19-relation in neuro-oncological population [

14].

Besides, we report that tumor-related anxiety correlates with COVID anxiety, as described in similar oncological contest [

15].

Examples of strategies adopted to deal with cancer anxiety that emerge from our study are: meditation, mindfulness, having sex, psychiatric drugs, psychotherapy (individual or group) and prayer. These are very different from the examples reported for dealing with COVID-19 anxiety: information, attention to the rules, isolation and use of protective devices.

We reported that 47.44% PTS felt different perception of the future during COVID-19, describing a higher sense of uncertainty, general perception of “different future” or feeling of “suspension” and fear.

A survey of 1,079 patients with multiple myeloma showed that they have concern about the future and events ahead, worries about family, friends and relatives, and also have paternal irritation, feelings of sadness, anger, fear, loneliness, and problems communicating with their spouses during the COVID-19 pandemic [

16]. Moraliyage reported that the most important fears of the individual in COVID-19 pandemic were fear of infection, weak immunity against the virus, travel and caution among caregivers, as well as fear of supporting family and others, fear of social isolation and fear of infection [

17]. Guven found more than 90% of cancer patients had moderate to severe fear of COVID-19 [

18].

Besides PTS survey, we parallel evaluate their caregivers. Caregivers are often overburdened with the situation of taking care of the PTS, and the increased risk for stress and mood impairment can even be associated to a higher morbidity and mortality [

19].

The origin of the stress, the goals, the appraisals, and the coping strategies of each individual and patient/caregiver dyads need to be considered to better manage the therapeutic path and to support families. One study reported that although the caregivers felt well supported by their social environment, stress, anxiety and depression are common phenomena in neuro-oncology, especially for female gender [

20].

In our study PTS’ and caregivers’ QoL are weakly correlated. Guariglia et al., 2021 [

21] reported that HGG PTS’ (n=24) and caregivers’ perceptions of QoL were correlated between them and with Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS). In a dyadic perspective, the adaptation of a member of the couple varies as a function of the other partner’s coping style. Other reported that QoL measures between PTS and their families were weakly or moderately correlated [

22].

As Baumstarck et al. 2018 [

23] described, coping strategies implemented by the high grade gliomas PTS (N=38) and their caregivers influenced their own QoL and the QoL of their relatives.

An appropriate health-system organization and a special attention to patient doctor communication can make the difference on QoL and the future perception. In this regard, communication works as a key tool to ensure the best possible care for the PTS and their caregivers: in such way they will act as allies in the continuum of care.

Some limits of our study are related to the type of questionnaires, that explore the different issues in a semistructured, self-administered survey, at a single time points. Such structures exhibit the advantages to collect fair answers (with no influence of interviewer/Caregivers opinion) and to be fast and easy to be completed, while not being completely exhaustive in grasping the details of the item studied and to lack the longitudinal evaluation of PTS’s perception change.

Other limit could be represented by the “monocentric” approach. However, it could be a great impact on our way to organize work in the team.

The merit of present survey is the collection of exclusively primary neuro-oncological case, although include very different types of brain tumors, with different prognosis, and at different time of therapeutic course as well as follow-up.

The majority of patients with malignant tumors are not necessarily hospitalized and not all have access to psychological support which may help them to cope with their fears, worries fatigue and anger, particularly during the Corona pandemic restrictions. To overcome feelings of isolation, depressive states, and insecurity about future perspectives, further supporting offers are needed. In this study the topics of meaning in life, having authentic and long-lasting relationships and mindful encounter with nature were important topics. These are the domains of psychotherapy and spiritual care. Spirituality, understood in this more broad and open context, can be seen as an individual resource for patient’s resilience, which is “maintaining self-esteem, providing a sense of meaning and purpose, giving emotional comfort and providing a sense of hope” [

24] in personal crisis management. Such spiritual care approaches [

25] can be easily incorporated into a more comprehensive treatment and support of tumor patients, particularly in times of pandemic restrictions.

The collected data will be useful to develop and ameliorate the coping strategies (maintaining social connection, redeploying previous coping strategies, engaging with spirituality, acceptance, self-distraction, and taking action, positive re-interpretation), as well as to modify the health-care system.

Setting up mental health facilities to mitigate pandemic-induced psychological impacts of any future eventualities can be of merit.

We unexpectedly verified at least good QoL in most of the studied fragile population, represented by neuro-oncological PTS during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also sustained by an adequate personal resources. However, the anxiety rates ranged from 4.6 to 7.7: higher score was described related to neuro-oncological disease than COVID-19, and by caregivers than PTS. The pandemic affected the tumor monitoring/therapy only marginally in our context: the PTS experienced treatment delay in less than 20% [

26]; surprisingly, 10% of the PTS decided to post-poned therapies. Contextually, the doctor-PTS interaction was reported as good, and did not change over the time.

The context of disease and pandemic reflected into the feeling of more uncertain future, as PTS and caregivers declared.

Based on the WHO biopsychosocial model of «health», the/a medical good disease management must include the PTS and their caregivers’ psychological needs, that can be coped also by a proactive support program. And it is more relevant in neuro-oncological setting during COVID-19 pandemic.

In this regard, communication works as a key tool to ensure the best possible care for the PTS and their caregivers: in such way they will act as allies in the continuum of care.