1. Introduction

Polyacetylene (PA, polyethyne) is a well-known conductive organic polymer. Linear trans-polyacetylene was firstly prepared by G. Natta in 1958 [

1]. Trans(E)- and cis(Z)- linear PA can be prepared with good degree of stereospecificity [

2]. PA can be considered as single-dimensional carbon material in which one hydrogen atom is attached to each carbon atom. Conductivity of PA depends mainly on its structure (cis- or trans-isomers) and trans(E)-PA operate better as conductor (4.4 × 10

-5 Ω

-1×cm

-1) than cis(Z)-PA (1.7 × 10

-9 Ω

-1×cm

-1). Pristine PA is a semiconductor, but, after doping with halogens, Lewis acids or oxidants/reductants (p/n-doping), its conductivity increases up to seven orders of magnitude. Hence it obtains metal properties in respect of conductivity after doping, irrespective of its initial polymeric (cis or trans) form [

3], [

4].

The energy bandgap between HOMO and LUMO orbitals can be used to estimate the conductivity of organic compounds. According to literature reports, the bandgap in

E-PA appeared to be 1.4 eV based on the NIR spectrum [

3]. The molecules with wide bandgaps (more than 3.0 eV) are insulators, while narrower energy gap attributes to semiconductors, and the molecules with ca. 0 eV energy gap are metal-alike conductors.

Another way to measure conductivity is to estimate a Fermi level. In organic compounds, it can be considered as an energy barrier, i.e. an energy needed to add electron to organic molecule or to remove an electron into infinity from the same molecule. Neutral molecule results in a cation/anion radical at the end of process. The smaller this barrier, the easier it will be for a substance to conduct the electric current. Thus, the Fermi level for an organic molecule can be considered as the ΔE of Total Potential Energy (TPE) between the Transition State (TS) and the Ground State (GS) of this molecule in the electron removal/addition process on the reaction coordinate from GS to the cation/anion radical state. Unlike the bandgap energy, which is quite simple to calculate by using quantum chemistry methods, finding the TS on the Potential Energy Surface (PES) utilizing the same methods is a black art.

The average molecular weight (M

w) of PAs obtained by various methods fluctuates in the range of 5-12 kDa [

5]. Since the DFT calculations of such large molecules are impossible using conventional computer systems, we decided to study the sequence of PA oligomers with hydrogens as end groups to simplify the calculations. The study of entire sequence of oligomers is very expensive and complicated task in terms of computer time and practicality. Therefore, a set of prime numbers {n} = {1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, …, 83, 89, 97} was chosen, where the prime number reflects the number of double bonds in each PA oligomer.

So, the study of bandgap of PA oligomers by quantum chemical methods can be suggested as a tool for studying the conductivity of PA theoretically.

3. Results and discussions

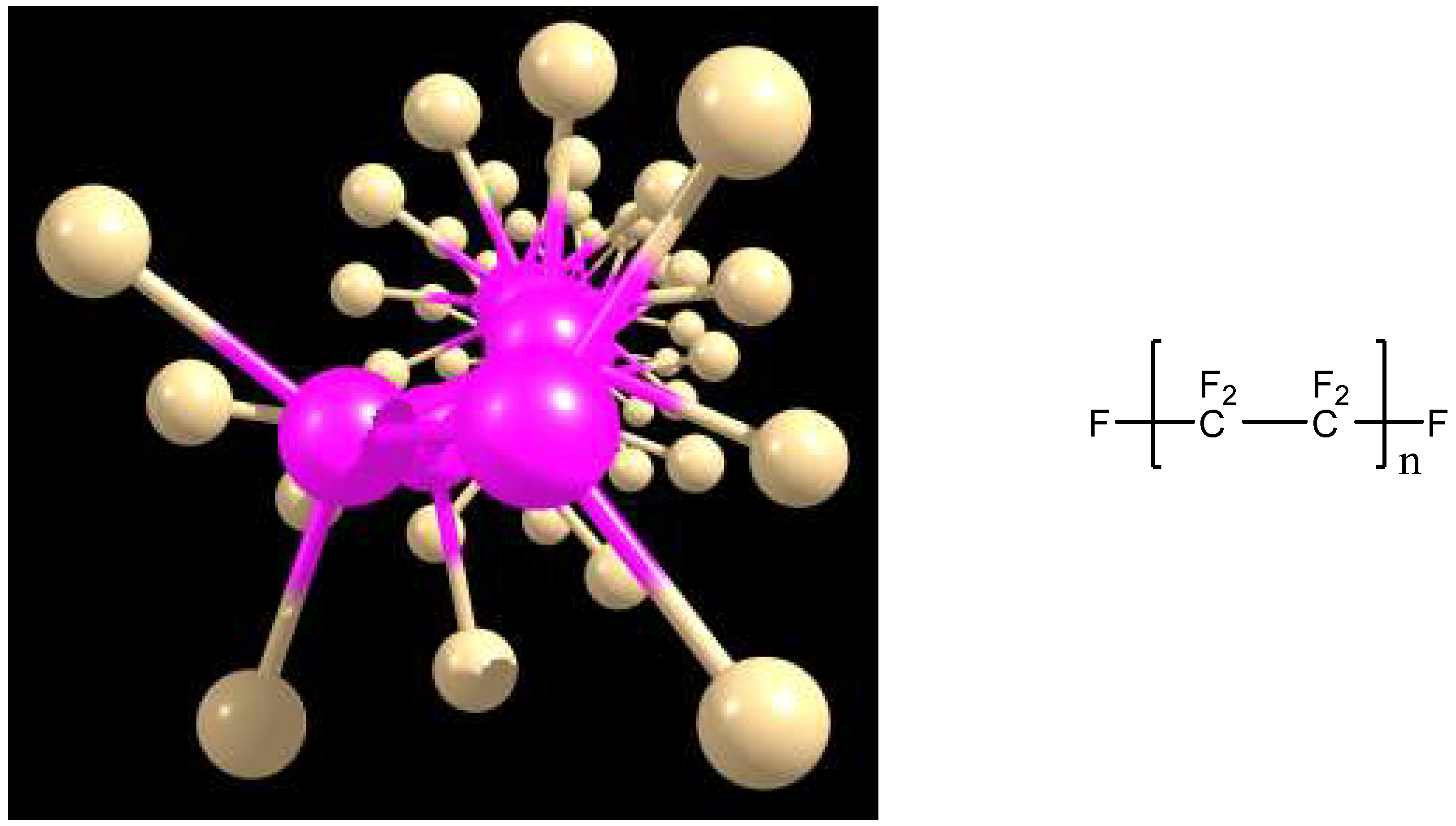

To verify the validity of the statement that a compound with a high bandgap value is an insulator, we investigated the bandgap of such a well-known organic insulator polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which is used in high voltage wires. Two molecules with the number of monomer units of 11 and 23 were investigated. Interestingly, we found that the optimized monomers have a helical pattern of the CF

2 units’ arrangement.

Figure 1 shows an example with n = 11 units as well as the general molecular formula of the PTFE oligomers studied. The calculated bandgap values were of 8.161 eV for the oligomer with n = 11 units and 7.972 eV for the oligomer with n = 23 units. Indeed, these two examples of PTFE oligomers exhibited high bandgap values, which are practically independent from the polymer chain lengths, which confirms their good abilities to act as insulators.

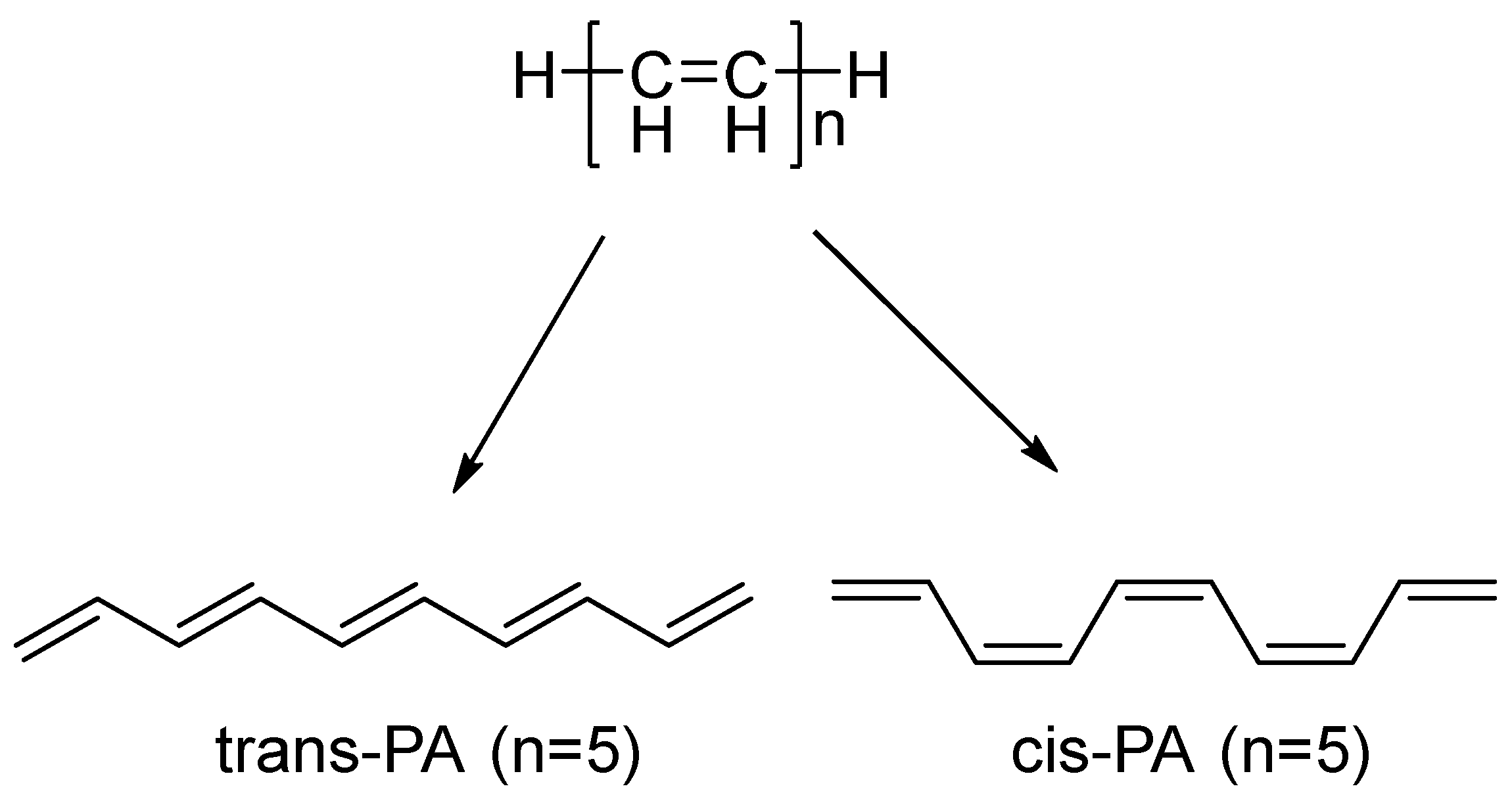

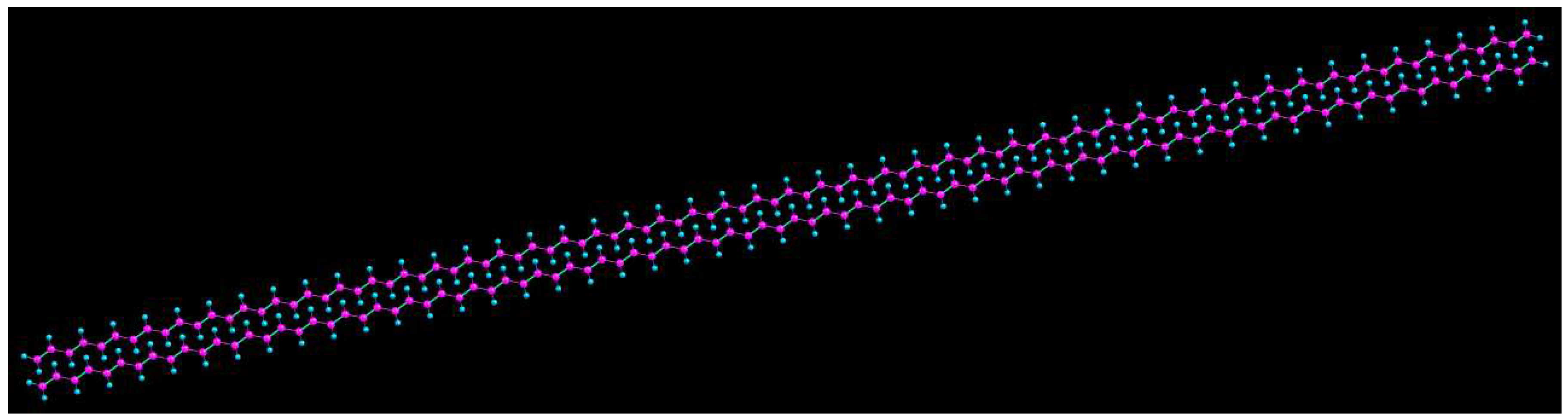

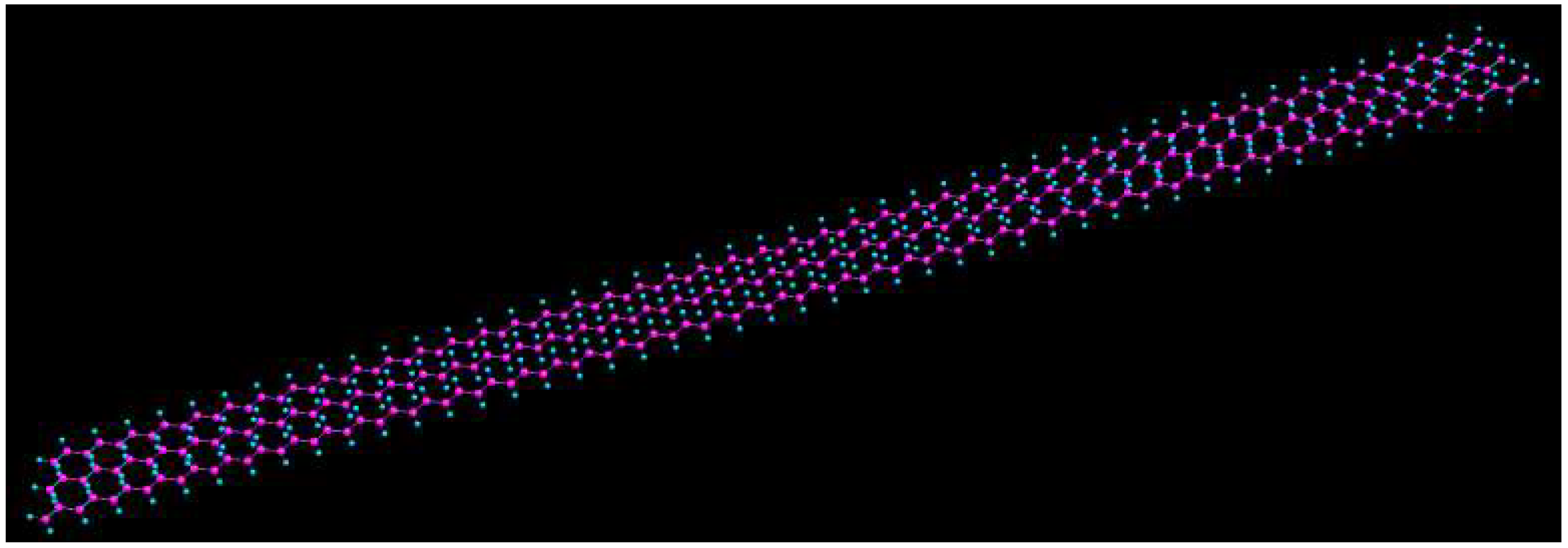

At the beginning of the study, we calculated the dependence of bandgap from the number of double bonds in PA oligomers. Both cis-PA and trans-PA were investigated initially. The sequence of the number of double bonds in PA was taken as the sequence of prime numbers from the first hundred {n} = {1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, …, 83, 89, 97} with H-atoms as ending groups,

Figure 2. The results are presented in

Table 1:

Figure 2.

Structure of PA with examples (n = 5).

Figure 2.

Structure of PA with examples (n = 5).

Table 1.

Results of DFT study of the E/Z-PA oligomers.

Table 1.

Results of DFT study of the E/Z-PA oligomers.

| n |

Energy E-PA, Eh

|

Energy Z-PA, Eh

|

Bandgap E-PA, eV |

Bandgap Z-PA, eV |

Delta Bandgap, eV |

Delta Energy, Eh

|

| 1 |

-78.59380543 |

7.521259 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

-156.058 |

-156.052 |

5.53171 |

5.589943 |

0.058233 |

0.005736 |

| 3 |

-233.494 |

-233.491 |

4.451791 |

4.514867 |

0.063076 |

0.003057 |

| 5 |

-388.367 |

-388.357 |

3.319570 |

3.498351 |

0.17878 |

0.009872 |

| 7 |

-543.24 |

-543.223 |

2.732616 |

3.004052 |

0.271436 |

0.017021 |

| 9 |

-698.114 |

-698.09 |

2.374784 |

2.720534 |

0.345751 |

0.024309 |

| 11 |

-852.988 |

-852.957 |

2.135648 |

2.542298 |

0.40665 |

0.031669 |

| 13 |

-1007.86 |

-1007.82 |

1.965793 |

2.422105 |

0.456311 |

0.039057 |

| 17 |

-1317.61 |

-1317.56 |

1.743964 |

2.275597 |

0.531633 |

0.053876 |

| 19 |

-1472.48 |

-1472.42 |

1.668588 |

2.22931 |

0.560722 |

0.061282 |

| 23 |

-1782.23 |

-1782.16 |

1.560123 |

2.163812 |

0.603689 |

0.076112 |

| 29 |

-2246.85 |

-2246.76 |

1.458678 |

2.109906 |

0.651228 |

0.098389 |

| 31 |

-2401.73 |

-2401.62 |

1.434759 |

2.095729 |

0.66097 |

0.105774 |

| 37 |

-2866.35 |

-2866.22 |

1.381859 |

2.068707 |

0.686848 |

0.12806 |

| 41 |

-3176.1 |

-3175.96 |

1.355927 |

2.057088 |

0.701161 |

0.142916 |

| 43 |

-3330.97 |

-3330.82 |

1.347845 |

2.051646 |

0.703801 |

0.15034 |

| 47 |

-3640.72 |

-3640.56 |

1.332824 |

2.043455 |

0.710631 |

0.165215 |

| 53 |

-4105.34 |

-4105.16 |

1.315681 |

2.034122 |

0.718441 |

0.187509 |

| 59 |

-4569.97 |

-4569.76 |

1.303109 |

2.027346 |

0.724237 |

0.209803 |

| 61 |

-4724.84 |

-4724.62 |

1.299572 |

2.025985 |

0.726414 |

0.217223 |

| 67 |

-5189.46 |

-5189.22 |

1.290809 |

2.021876 |

0.731067 |

0.239519 |

| 71 |

-5499.21 |

-5498.96 |

1.286102 |

2.019808 |

0.733706 |

0.254358 |

| 73 |

-5654.08 |

-5653.82 |

1.284007 |

2.019046 |

0.73504 |

0.261778 |

| 79 |

-6118.71 |

-6118.42 |

1.278564 |

2.016924 |

0.73836 |

0.284037 |

| 83 |

-6428.45 |

-6428.16 |

1.275544 |

2.015808 |

0.740264 |

0.298876 |

| 89 |

-6893.08 |

-6892.76 |

1.27168 |

2.014448 |

0.742768 |

0.321135 |

| 97 |

-7512.57 |

-7512.22 |

1.267534 |

2.013060 |

0.745526 |

0.350814 |

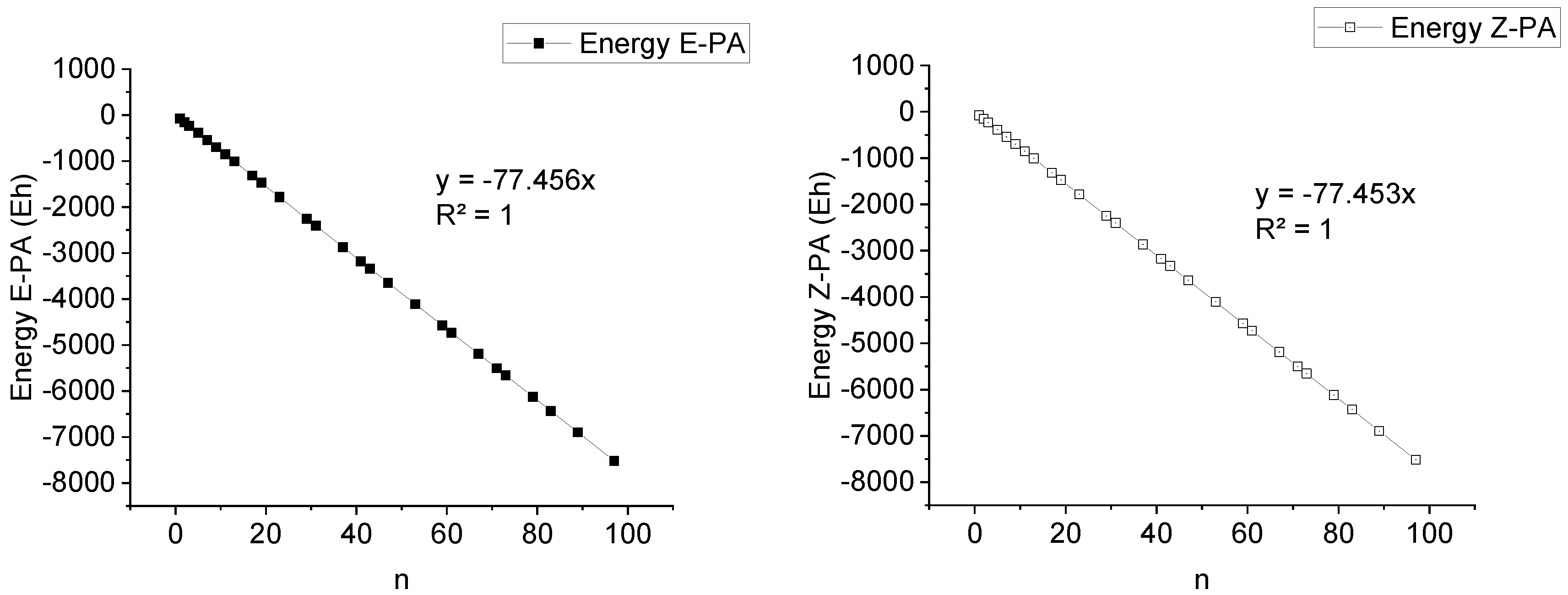

Figure 3.

Dependence of E/Z-PA TPE from number of double bonds.

Figure 3.

Dependence of E/Z-PA TPE from number of double bonds.

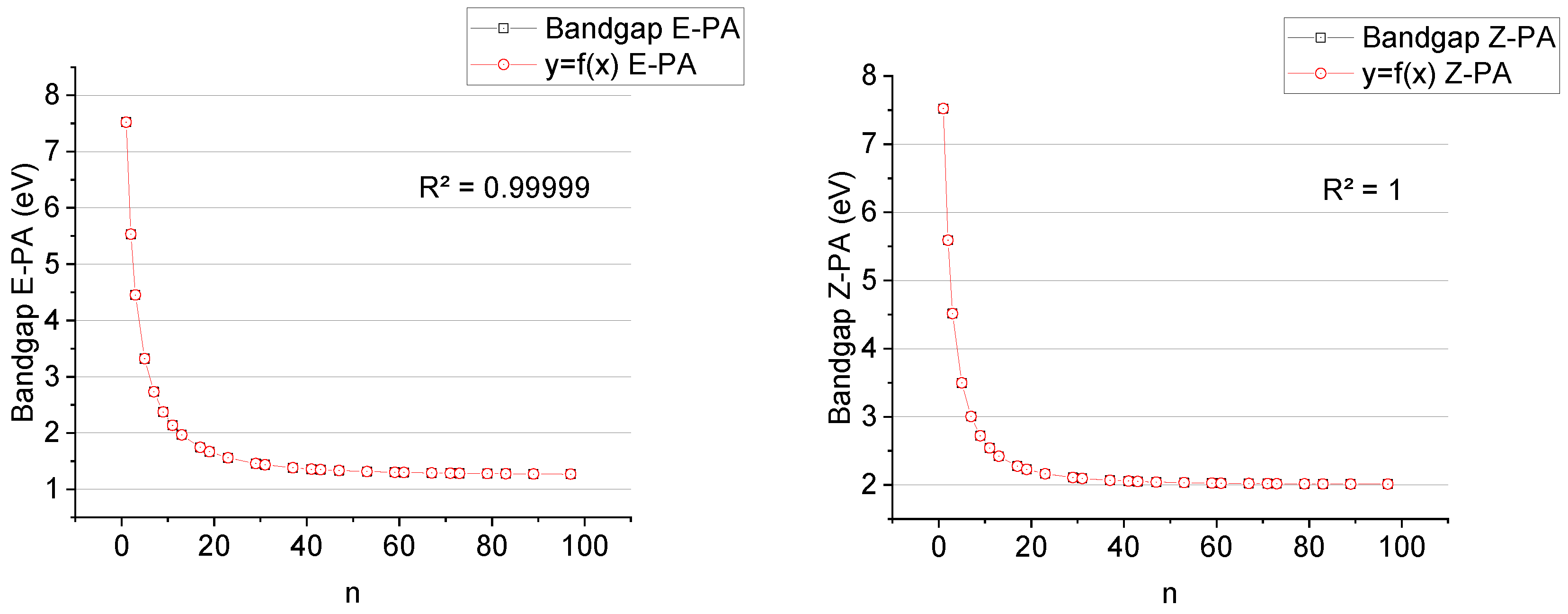

Based on the obtained results, we found that E-PAs possess lower TPE than Z-PAs because in the trans-isomer, the overlap of the p-orbitals of the conjugated double bonds is slightly more efficient. TPE of E/Z-PA increases linearly upon the increase in the number of double bonds,

Figure 4. The bandgap tends to some value near ~1.26 eV for

E-PA and ~2.01 eV for

Z-PA respectively when n is increasing,

Figure 4.

Extrapolation of the obtained data was performed to find out the precise values of bandgap to which ones tend asymptotically. Such math analysis was carried out by using TableCurve 2D v5.01 program.

For E/Z-PA data sets, Equation 1 was chosen to be best for extrapolation. In the case of E-PA, bandgap value tends to a = 1.265 eV (R

2 = 0.99999) when x (n) → ∞, Equation 2. For the n = 461 (n= 461 for the longest known PA with M

w = 12 kDa), the bandgap appeared to be 1.26 eV. In the case of Z-PA, the bandgap value tends to a = 2.012 eV (R

2 = 1) when x (n) → ∞. For n = 461, the bandgap appeared to be 2.01 eV (see corresponding SI Excel sheets for more information).

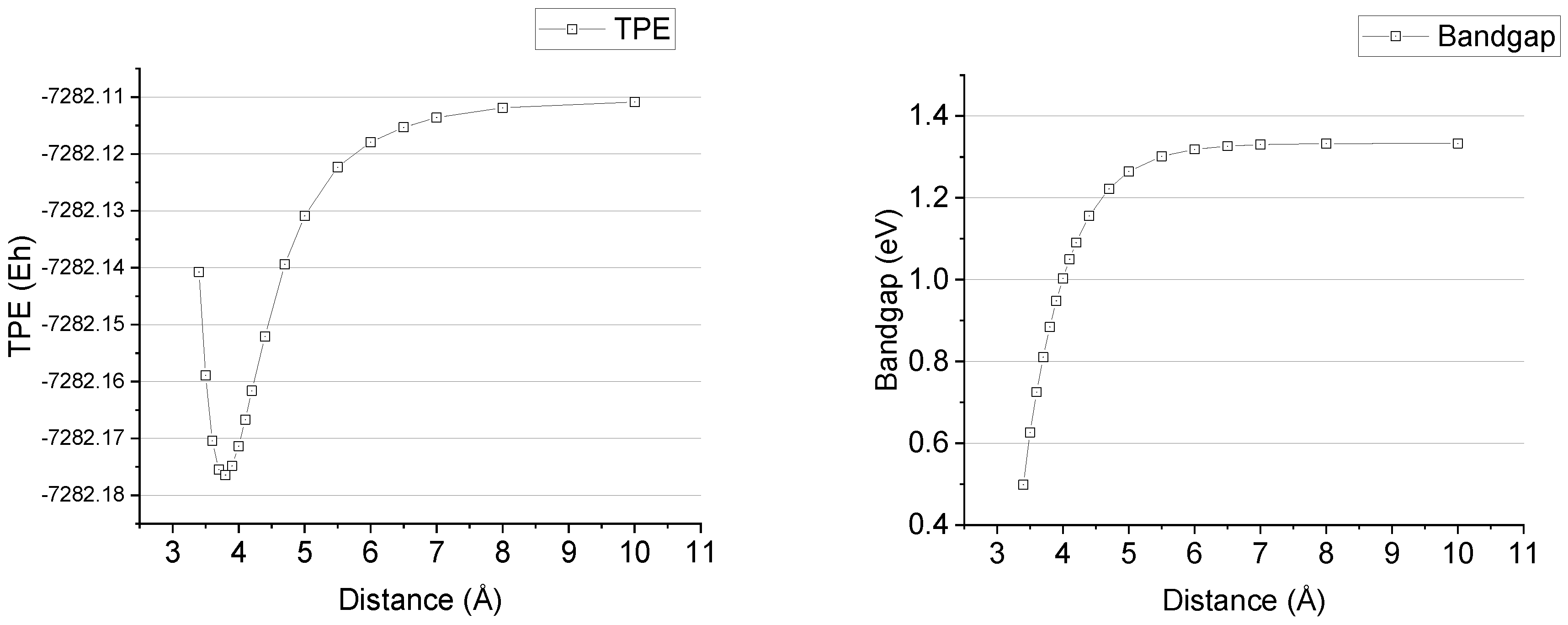

Next, the assumption of the mutual influence of the overlap of two PA chains in space on the bandgap was tested. Two pre-optimized E-PA chains containing 94 carbon atoms (n = 47) were chosen. Initially, they were located one above the other in parallel to xy domain planes with a starting distance of 3.4 angstrom (distance between the graphene layers in graphite). After that, the optimization was performed with geometric constraints of x and y coordinates due to pre-optimization of the separate chains which allowed them to be intact. Optimum/minimum energy geometry at 3.771 Å was achieved. An energy bandgap was found to be 0.871 eV, which is 30% lower than the bandgap of the E-PA with the longest known chain,

Figure 5.

The Single Point (SP) calculation of the such two chains, but with distance 3.4 Å gave the bandgap 0.498 eV. The same operation with three E-PA chains containing 94 carbon atoms each (n = 47) produced energy bandgap 0.294 eV in the case of total overlap,

Figure 6.

The sequence of SP calculations was performed subsequently for two chains with total overlap of E-PA (n = 47), in which distance between chains increased from 3.4 to 10 angstrom. The results are presented in

Figure 7 and

Table 2:

As it can be seen from

Figure 7 and

Table 2, the minimum of TPE in E-PA of two oligomers’ cluster corresponds to the previously obtained distance value of 3.771 Å, and tends to the double value of the single chain TPE when distance is large enough while the bandgap grows with distance from the value of 0.498 up to 1.333 eV, the latter corresponds to the exact value of single chain bandgap, see

Table 1.

The influence of the overlap in the cluster of E-PA on the bandgap value was investigated as well. As can be seen from

Table 3, there is a slight effect on the bandgap when some double bonds came out of the overlap. The SP calculations were carried out at the constant optimal distance 3.771 Å by shifting the chains relative to each other by the corresponding number of double bonds.

Thus, the influence of intramolecular distance on the cluster bandgap was confirmed by using several E-PA oligomers with a chain length of 47 double bonds. The resulted bandgap was found to be 30% less than that of an isolated single chain at the optimal distance between two chains. As this distance decreases, the bandgap decreases even more. The effect is cumulative, and the bandgap decreases further when more chains interact. Quality of the overlap has a slight effect on bandgap. We rationalize that the same regularities would be observed in the case of Z-PA oligomers.

Finally, the investigation of influence of the doping on the conductivity of PA was performed. Even though the study of the TS of the process of cation/anion radicals’ formation from PA is difficult, we investigated the final products of these processes. The process of removing an electron from a molecule can be considered as an oxidation process, while the addition of an electron can be considered as a reduction of the PA molecule. In other words, removing of one electron can be considered as a p-doping of PA while the addition of one electron is a PA n-doping. Initially, the cation/anion radicals of E/Z-oligomers with n = 29-53 were studied. The bandgaps of the cation radical and anion radical were almost identical, so the study of anion radicals was discontinued and continued for [E/Z-PA]

•+ isomers up to n = 97. For [Z-PA]

•+ isomers, the bandgap value was 1.33 - 2 times lower, see

Table 4.

Table 4.

.

| |

Cation |

Anion |

| n |

E |

Z |

E |

Z |

| 29 |

0.435113 |

0.213747 |

0.437807 |

n/a |

| 31 |

0.392582 |

0.189338 |

0.39465 |

n/a |

| 37 |

0.289885 |

0.13848 |

0.291708 |

n/a |

| 41 |

0.239217 |

0.116711 |

0.240959 |

n/a |

| 43 |

0.217366 |

0.108003 |

0.217856 |

n/a |

| 47 |

0.180848 |

0.093771 |

0.181039 |

0.094724 |

| 53 |

0.140711 |

0.078152 |

0.140657 |

0.079159 |

| 59 |

0.112819 |

0.066886 |

n/a |

n/a |

| 61 |

0.105309 |

0.063702 |

n/a |

n/a |

| 67 |

0.087839 |

0.055893 |

n/a |

n/a |

| 71 |

0.07856 |

0.05162 |

n/a |

n/a |

| 73 |

0.074805 |

0.049688 |

n/a |

n/a |

| 79 |

0.064845 |

0.044709 |

n/a |

n/a |

| 83 |

0.059485 |

0.041933 |

n/a |

n/a |

| 89 |

0.0528 |

0.038287 |

n/a |

n/a |

| 97 |

0.0459 |

0.034341 |

n/a |

n/a |

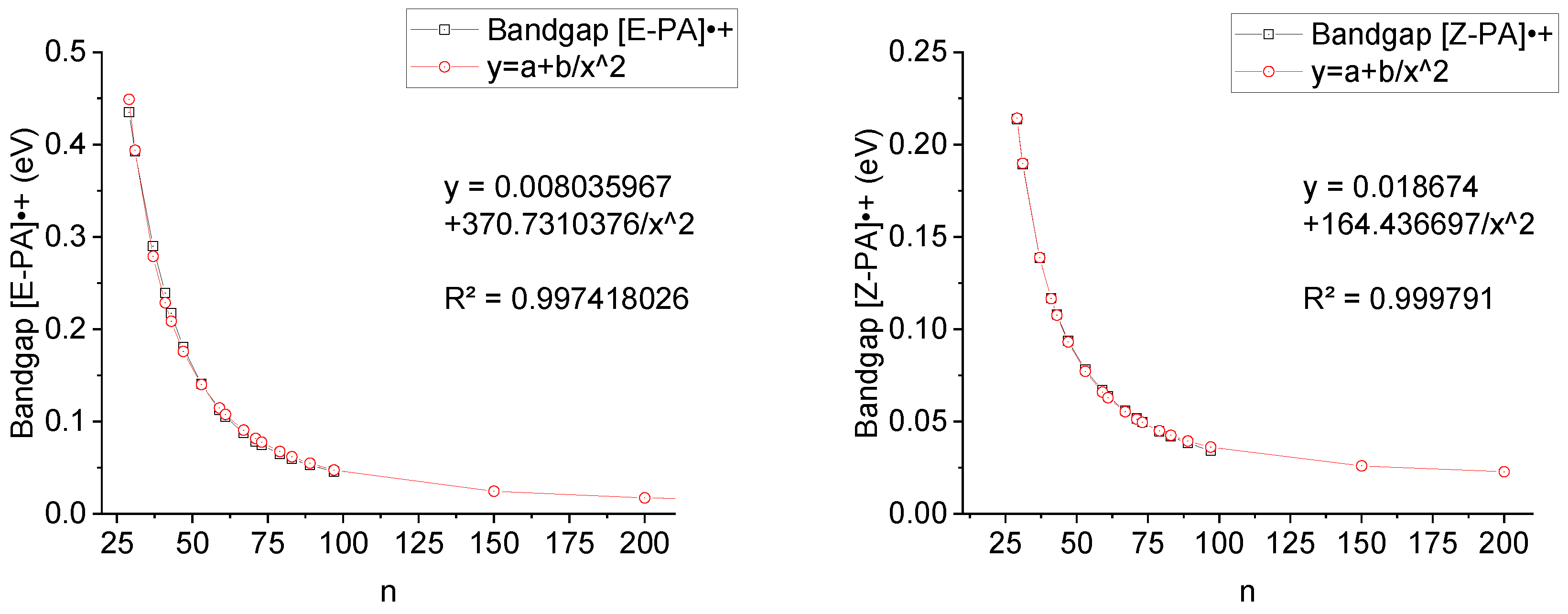

Extrapolation of the bandgap data of [E/Z-PA]

•+ relative to the number of chain units “n” gave a good result with the function presented in Equation 3,

Figure 8. According to Equation (2), the bandgap, a = 0.008 eV (R

2 = 0.997418) for E-PA, while a = 0.019 eV (R

2 = 0.999791) for Z-PA, when x tends to infinity. These values cannot be trusted due to possible extrapolation errors, however, there is a tendency for the difference in bandgap to decrease, see

Table 4. Interestingly, the bandgap value (0.0272 eV) for the Z and E isomers become identical at n = 139 according to Equation 4, see SI for details.

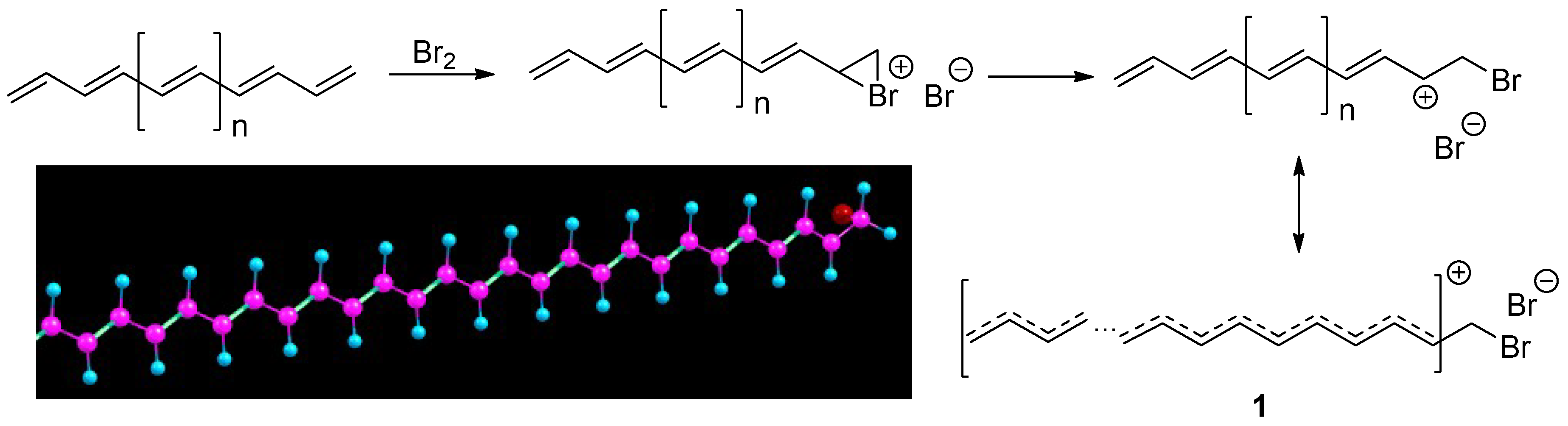

Next, we investigated products of the bromination reaction of the E/Z-PA with n = 47. The bromination reaction with the outer double bond was considered yielding the most stable carbocation with the longest conjugation chain. The result would be a less stable product if the reaction would occur with any other double bonds because such reaction will produce separation of the conjugation by the C

sp3-H fragment. On the other hand, the bromination reaction with a much longer chain (then presented in this work) even in the middle will result in the formation of considerable stable product with lower bandgap and good conductivity. Having reacted in this way several times, the long chain will contain several shorter conjugated cations, which should lead to a dramatic decrease in the bandgap of the entire polymer. Thus, the use of long chains will also allow increasing the dopant loading in the polymer. The restriction on using PA with a chain length of 100-150 units mentioned above is lifted in this way. An example of the E-PA reaction with bromine is presented in

Scheme 1. Reaction with Z-PA proceeds in the same way.

The resulting carbocation is very stable because the positive charge is highly delocalized along the long-conjugated polymer molecule and the bromide anion cannot “feel” feeble positive charge of each carbon atom and, accordingly, cannot react with it. In support of this, two facts can be presented. First, if the resulting carbocation would easily react with a bromide anion to form a dibromo product, only the destruction of the outer double bond would occur. This transformation would only lead to a decrease in the conjugation chain and some increase in the bandgap will occur and PA remains a semiconductor if modified in that way. And the second, a dramatic decrease in the bandgap is observed in practice. Thus, it should be recognized that the doping with bromine results in the formation of a product with a lower bandgap, which can be confirmed by calculation. Indeed, after geometrical optimization of the reaction products, we observed lower bandgaps in respect of starting E/Z-PA with the same chain length (n = 47),

Table 5.

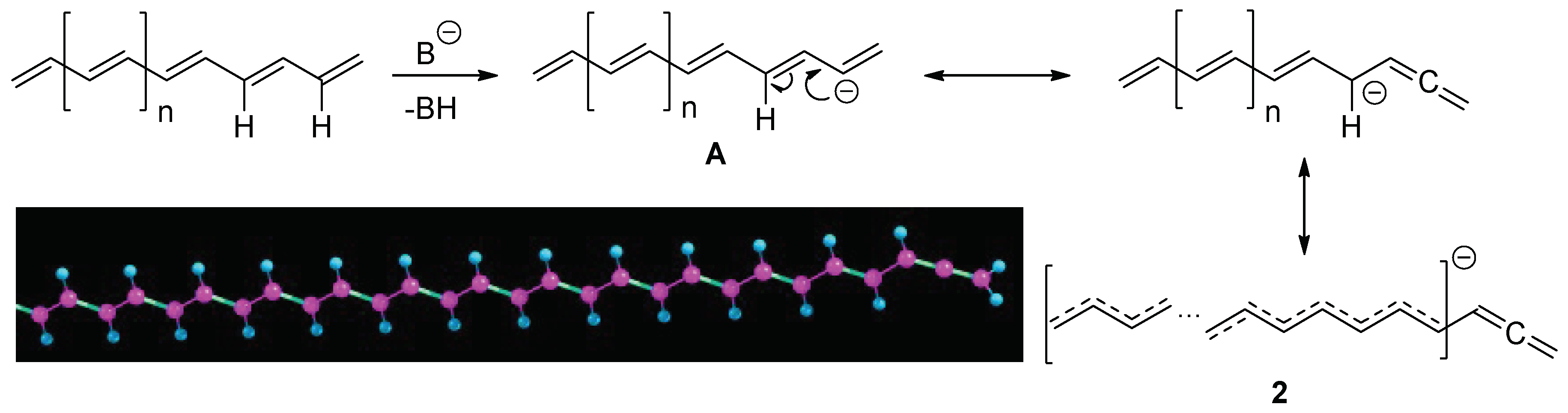

Finally, we performed a bandgap study of the deprotonation products of E/Z-PA with n = 47. After the geometry optimization of canonical anion

A, we obtained corresponding anionic structure

2 with terminal allene fragment,

Scheme 2. Interestingly, in the structure

2, there is no single C

sp3H fragment due to strong delocalization of a negative charge. However, when an allene fragment is formed by means of the reaction of the internal C

sp2H fragment, a conjugation through it is impossible. This occurs because of the presence of allene moiety with the p-orbitals planes lying, as it is known, in a perpendicular way from each other. Therefore, no advantage can be achieved compared to a doping through bromination. Indeed, after the calculation of the E/Z-PA anions, we achieved bandgap values comparable with the calculated bandgaps of the bromination reaction products, see

Table 6. Reaction with Z-PA proceeds in the same way.

4. Conclusions

By means of DFT calculations with PM3/B3LYP1/def2-TZVP level of theory, it was confirmed that such a well-known polymeric organic insulator as PTFE has a bandgap of ~ 8 eV and this value practically does not depend on the polymer chain length. This confirmed the statement that the insulators possess high bandgap and proved the applicability of the DFT calculations with the above-mentioned level of theory to be used in a frame of this work.

Regarding the improvement of the pristine PA conductivity - there is no point in increasing the number of polymer units more than 100-150 during the synthesis. Increasing the number of units further does not lead to a significant decrease in the bandgap (it tends to value 1.26 eV in the case of E-PA and 2.01 eV in the case of Z-PA), but leads to insoluble crystalline structures, which is not suitable, for example, for applying a conductor using inkjet printing technology. The computed value of 1.26 eV is close enough to the experimental value 1.4 eV in the case of E-PA. The PA synthesis can be quenched at the stage of 100-150 units, which can lead to a soluble form of PA with optimal conductivity.

It is confirmed that the trans-isomer of PA has a smaller bandgap than the cis-isomer which affects its better conductivity.

Having an optimal number of units, pristine PA nevertheless remains a semiconductor, the situation is not particularly improved by the fact that clusters of several closely spaced polymer molecules can have a reduced bandgap compared to even one longer chain composed from all available atoms. This positive effect is negated by the fact that in reality, PA clusters do not have an ideal overlap due to chaotical orientation of neighborhood PA chains in space.

Indeed, the use of dopants dramatically decreases the bandgap as well as increases the conductivity of PA, which is proven theoretically in this work by the calculations of the E/Z-PA anion/cation radicals, as well as the products of interaction with bromine and deprotonation products. Unlike pristine PA, the use of longer chains in doping is justified, since this will allow obtaining products with better bandgap characteristics and will allow increasing the dopant load in PA. It can be assumed that the presented approach can be used as a tool to find the optimal dopant for the best conductivity of PA utilizing conventional quantum-chemical calculations.