1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) processes, such as laser-based powder bed fusion of metals (PBF-LB/M), enable the realization of complex topologies with variable stiffness and internal cavities, which can significantly enhance structural performance [

1,

2]. However, with increasing geometric complexity, manufacturing costs rise due to the need for additional support structures, rework, and longer production times [

3]. Additionally, the limited build space of AM machines constrains the maximum size of a single AM component manufacturable, affecting the feasibility of AM for various applications. To overcome these limitations and reduce manufacturing costs, part separation and subsequent joining of AM subcomponents can be an effective strategy [

4,

5]. Moreover, the freedom of design underlying AM processes is often needed only in specific regions of a structure. Thus, it can make sense to enhance the structure with non-AM components (i.e. fiber-reinforced composites) by means of a hybrid structure [

6,

7]. Adhesive bonding is a particularly promising joining technology in this context, as it adds minimal weight and does not restrict the geometry of the joining surfaces or the material of the adherends [

8,

9,

10,

11].

To ensure structural integrity, the adhesive joint design plays a crucial role [

12,

13]. This entails ensuring a sufficiently large adhesive surface area and preferably subjecting the adhesive to shear rather than peel stress (tensile stress perpendicular to the adhesive surface) [

12,

13,

14]. Adhesive joint designs can roughly be categorized into butt joints and lap joints. In butt joints the substrates are simply joined end-to-end at their front surfaces. Due to the comparably small adhesive surface area and the occurrence of large peel stresses, this design is less common in structural applications [

15]. In lap joints, the joining surfaces of the substrates are overlapping and therefore providing an arbitrarily large adhesive surface area. Disadvantageous is the additional weight due to the material overlap, as well as the eccentric load application in combination with finite adherend stiffness, which is causing pronounced adhesive stress increases at the overlap ends [

16]. As the stress increases initiate failure [

17], it is conceivable to increase the bearable load of the joint (bond strength) while maintaining a constant adhesive surface area by homogenizing the adhesive stress distribution and shifting the adhesive stress state towards pure shear through optimizing the geometry of the adherends.

Finite element (FE)-based genetic algorithm (GA) and topology optimization (TOP) approaches have already been applied to enhance bond strength in rectangular [

18,

19] and tubular [

12] single-lap joints (SLJ´s). These studies employ either a continuum mechanics approach with energy- or stress-based failure criteria or a fracture mechanics approach utilizing cohesive zone modeling (CZM) and a damage-based failure criterion. While previous TOP procedures neglect adhesive plasticity in the corresponding constitutive response, an essential factor in strength assessment [

20,

21], the GA approach accounts for debonding through a traction-separation law and considers adhesive plasticity via a Johnson-Cook plasticity model, making it the most suitable method in terms of strength assessment and failure prediction. However, this approach is computationally expensive and, as a result, fails to leverage the extensive design flexibility offered by additive manufacturing. Although all procedures demonstrate significant potential for increased bond strength, previous studies lack experimental validation.

Therefore, in this study, a computationally efficient solid isotropic material with penalization (SIMP) algorithm [

22] and implicit FE analysis are used to optimize the topology of an additively manufactured laser-based powder bed fusion aluminum alloy AlSi10Mg (PBF-LB/M/AlSi10Mg) sleeve, which is part of an axially loaded single-lap tubular joint (SLTJ) adhesively bonded to an inner carbon fiber reinforced composite (CFRC) tube using a highly ductile two-component (2C) structural adhesive based on epoxy resin (

3M Scotch-Weld, DP490). The joint is modeled using a continuum mechanics approach, where adhesive plasticity is accounted for by means of a multilinear elastoplastic material model. To increase the bond strength of the joint, the element density of the PBF-LB/AlSi10Mg sleeve is iteratively adjusted to achieve homogenous adhesive shear stress. The optimum sleeve topology found is redesigned considering manufacturing constraints of the PBF-LB/M additive manufacturing process. To quantify the resulting adhesive stress state, non-linear FE analysis is conducted at different tensile loads with tubular joints featuring optimum, redesigned and non-optimized cylindrical reference sleeves. Subsequently redesigned and cylindrical reference sleeves are manufactured and adhesively bonded to CFRC tubes to experimentally quantify the difference in bond strength by means of static tensile and fatigue testing.

2. Materials and Methods

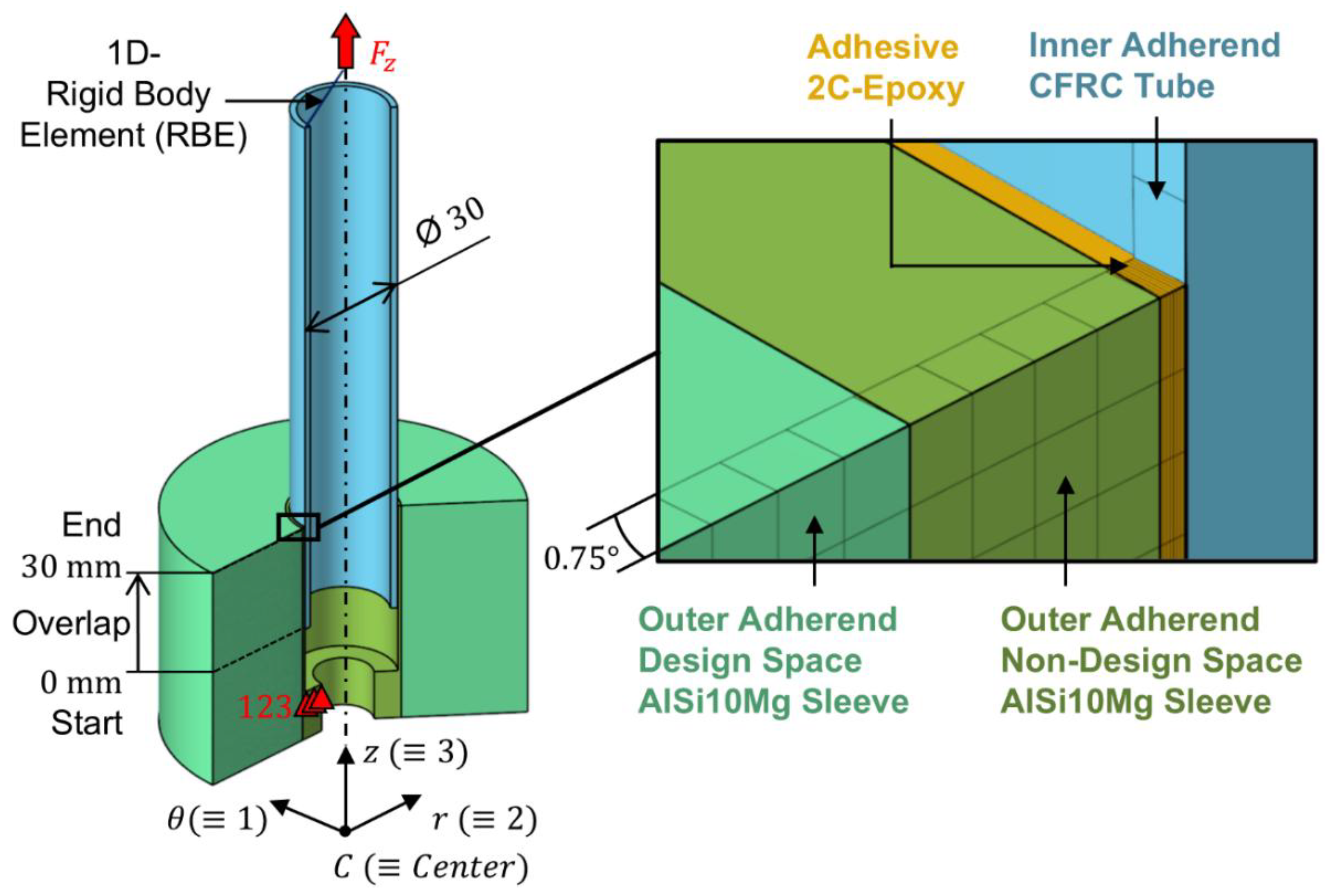

The axially loaded SLTJ subjected to implicit FE-based TOP comprises an inner adherent, which is a roll-wrapped unidirectional CFRC tube having an outer diameter of

and a wall thickness of

, as well as an outer adherent, which is an additively manufactured PBF-LB/M/AlSi10Mg sleeve having an inner diameter of

. The adherends are joined by an interstitial layer of a two-component epoxy-based (2C-Epoxy) structural adhesive (

3M Scotch-Weld, DP490) having a thickness of

. The outer adherent is divided into the non-design space (NDS) having an outer diameter of

and the design space (DS) having an outer diameter of

. During the optimization process, the element density of the DS is the variable to be altered to meet the objective function of the SIMP optimization (

Figure 1).

The overlap between the inner and outer adherend is

, leading to a adhesive surface area of

. To minimize computational effort, only a

segment of the rotationally symmetric joint was discretized using

CHEXA20 second-order solid elements (outer adherend and adhesive), respectively

CQUAD8 second-order shell elements (inner adherend), which were assigned to a cylindrical analysis coordinate system. To enforce rotational symmetry, the azimuthal displacement of elemental nodes at the symmetry faces was constrained to

. The adhesive layer is represented by eight elements in the radial direction (

) and 120 elements in the longitudinal direction (

), resulting in element edge lengths of

(radially) and

(longitudinally). The average element edge length in the DS of the AlSi10Mg Sleeve results to

. The contacts between adjacent components are modelled continuously by merging coincident elemental nodes at the component interfaces. To replicate the boundary conditions of the pursuing tensile tests, rigid clamping is applied by fixing all degrees of freedom at nodes on the top surface of the clamping shoulder (bolt head seating, see

Figure 2) and a longitudinal tensile force

is introduced at nodes on the top surface of the CFRC tube using a one-dimensional rigid body element (1D-RBE). As part of the TOP process, the longitudinal tensile force was set to

. Given the reduced adhesive surface area of

of the

segment considered, this results in a nominal adhesive shear stress of

.

The material parameters utilized for modeling the structural mechanical behavior of the components are shown in

Table 1.

As the von Mises equivalent stress in the AlSi10Mg sleeve must not exceed the yield strength of

, it is reasonable to define linear-elastic material parameters only. Neglecting the build-direction-induced anisotropy intrinsic to the PBF-LB/M process is permissible, as the material parameters defined in

Table 1 were determined from vertically oriented tensile samples [

23], consistent with the intended build direction of the AlSi10Mg sleeves. The CFRC tube exhibits linear-elastic material behavior up to the tensile strength of

[

24]. Considering a nominal tensile stress in the CFRC tube of

(corresponding to

, the constitutive response of the CFRC tube is fully characterized by specifying linear-elastic material parameters. The CFRC tube laminate is composed of ten stacked unidirectional plies having a thickness of

each. The fibers extend parallel to the longitudinal (z) direction of the tube. By modeling the laminate ply-based, the layer stack and fiber orientation can be represented by single shell elements. This requires specifying the orthotropic material parameters of a single unidirectional ply, along with the orientation and order of the plies. The material parameters provided in

Table 1 are referring to a unidirectional ply with high tenacity (HT) fibers and a fiber content of

according to [

24]. Since the 2C-Epoxy adhesive exhibits non-linear stress-strain behavior far below the ultimate strength of

, pure consideration of elasticity is insufficient for structural-mechanical analysis [

20,

21]. To account for the adhesive´s plasticity, in [

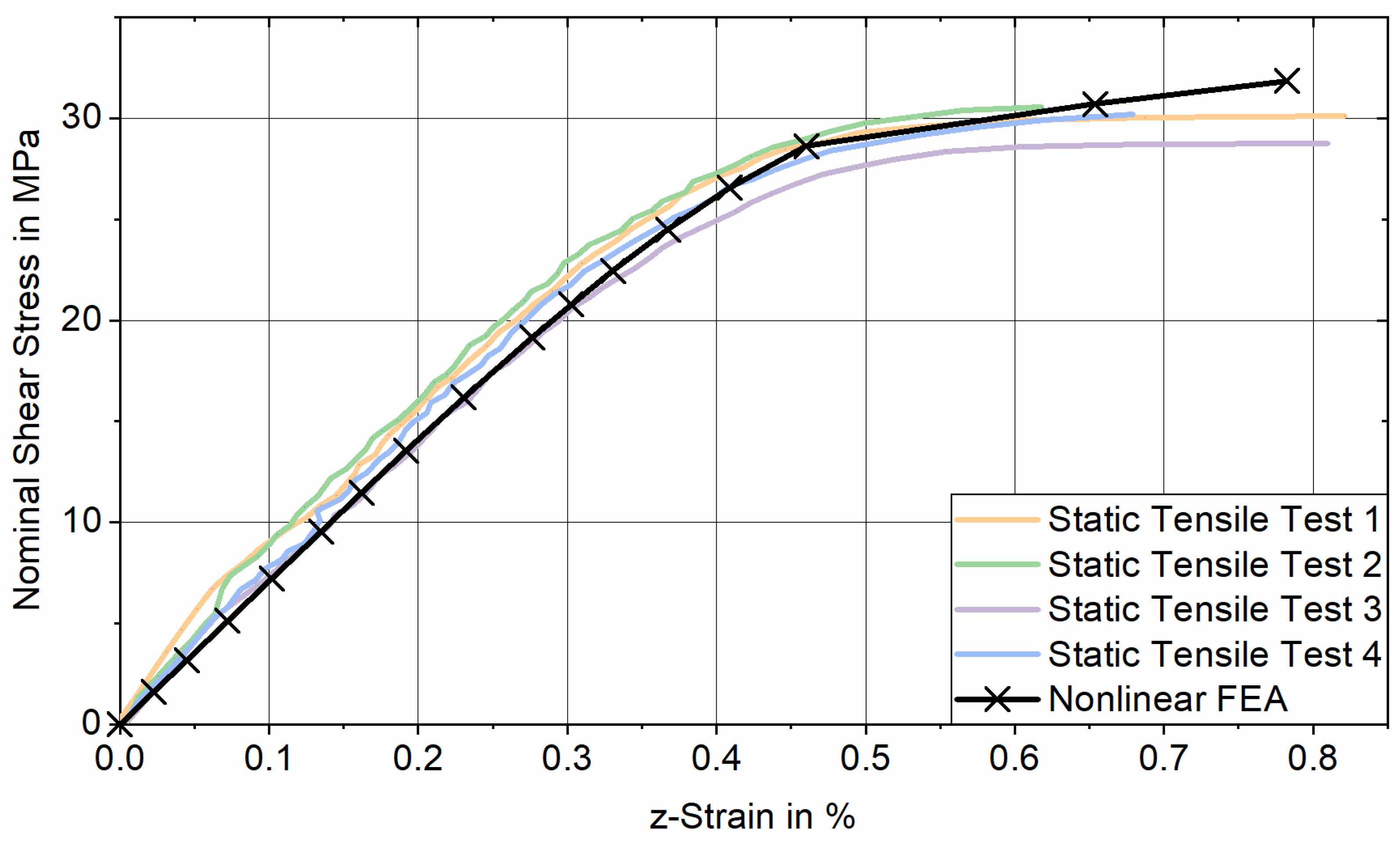

25] a multilinear elastoplastic material model is employed. In doing so, the technical stress-strain curve obtained from static tensile tests using adhesive bulk samples according to [

26] is approximated using multiple regression lines and the deflection points of the locally linearized stress-strain curve serve as input parameters for the material model. By assuming elastic and plastic isotropy, the structural-mechanical behavior of the 2C-Epoxy adhesive is fully characterized by additionally specifying the shear modulus G, which was determined through torsion testing of butt-bonded hollow cylinders [

25].

The optimization function considered by the SIMP algorithm is defined by an optimization target and optimization constraints [

22]. As FE-based analysis of an axially loaded SLTJ using CZM shows that bonding failure, following a bi-linear traction-separation law, correlates with the maximum first principal stress adjacent to the bonding interface [

12], the optimization target is set to minimize the first principal stress

within the adhesive component. Considering a reference value for the first principal stress of

, pure adhesive shear and minimum peel stress is aimed for. Optimization constraints regarding the aluminum sleeve (DS and NDS) include a maximum von Mises equivalent stress of

and a mass reduction of

in the DS. To meet the objective function criteria, the SIMP algorithm iteratively adjusts the element density (

) of each individual element in the DS of the PBF-LB/AlSi10Mg sleeve. The

can vary in the range of

, where

corresponds to no material and

corresponds to solid material. Since the penalization parameter of the SIMP algorithm is set to

, intermediate element densities (

) are penalized, promoting a clear distinction between solid and void regions. The optimization process converges when the relative change in the objective function between two consecutive iterations falls below the threshold of

.

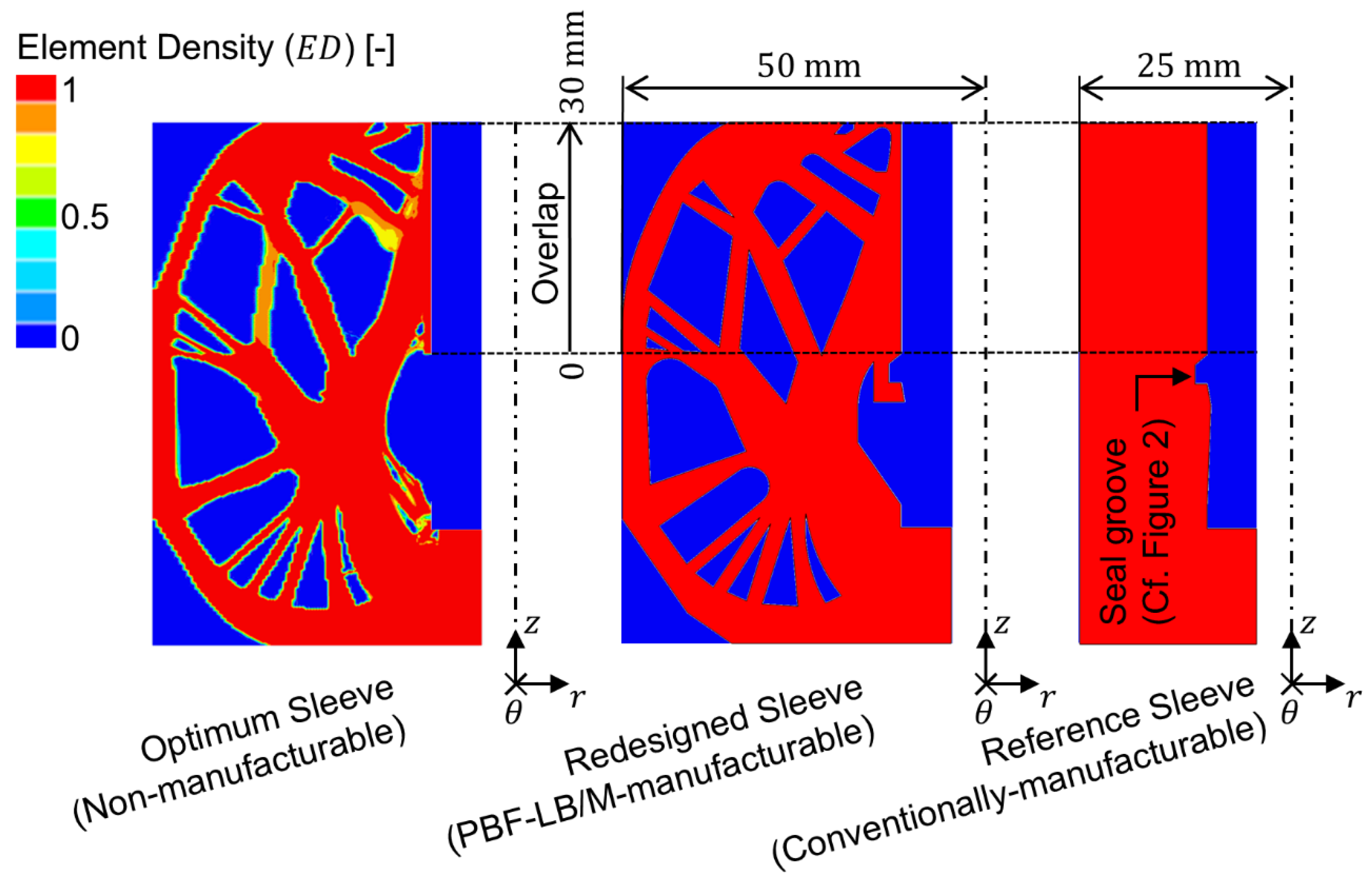

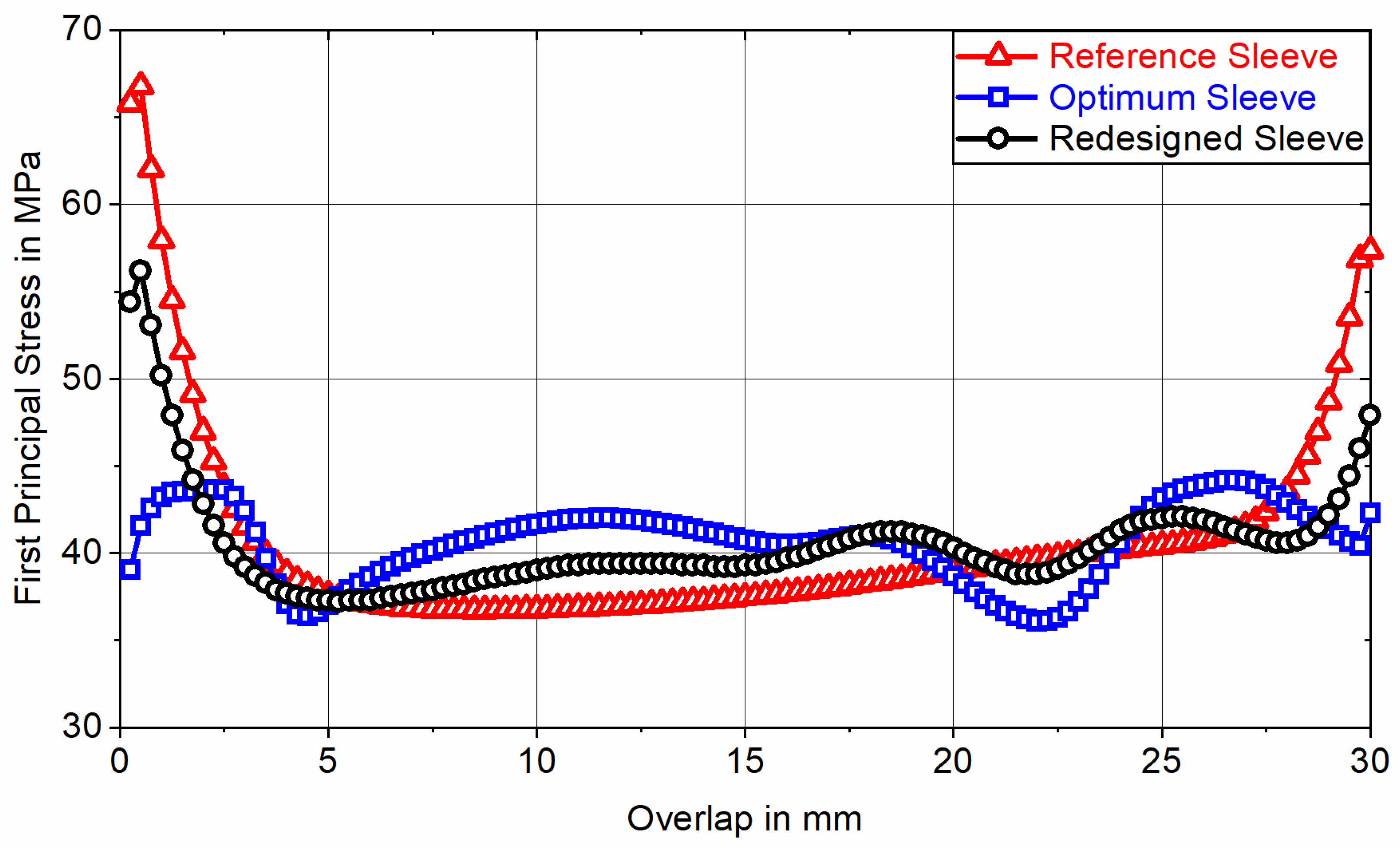

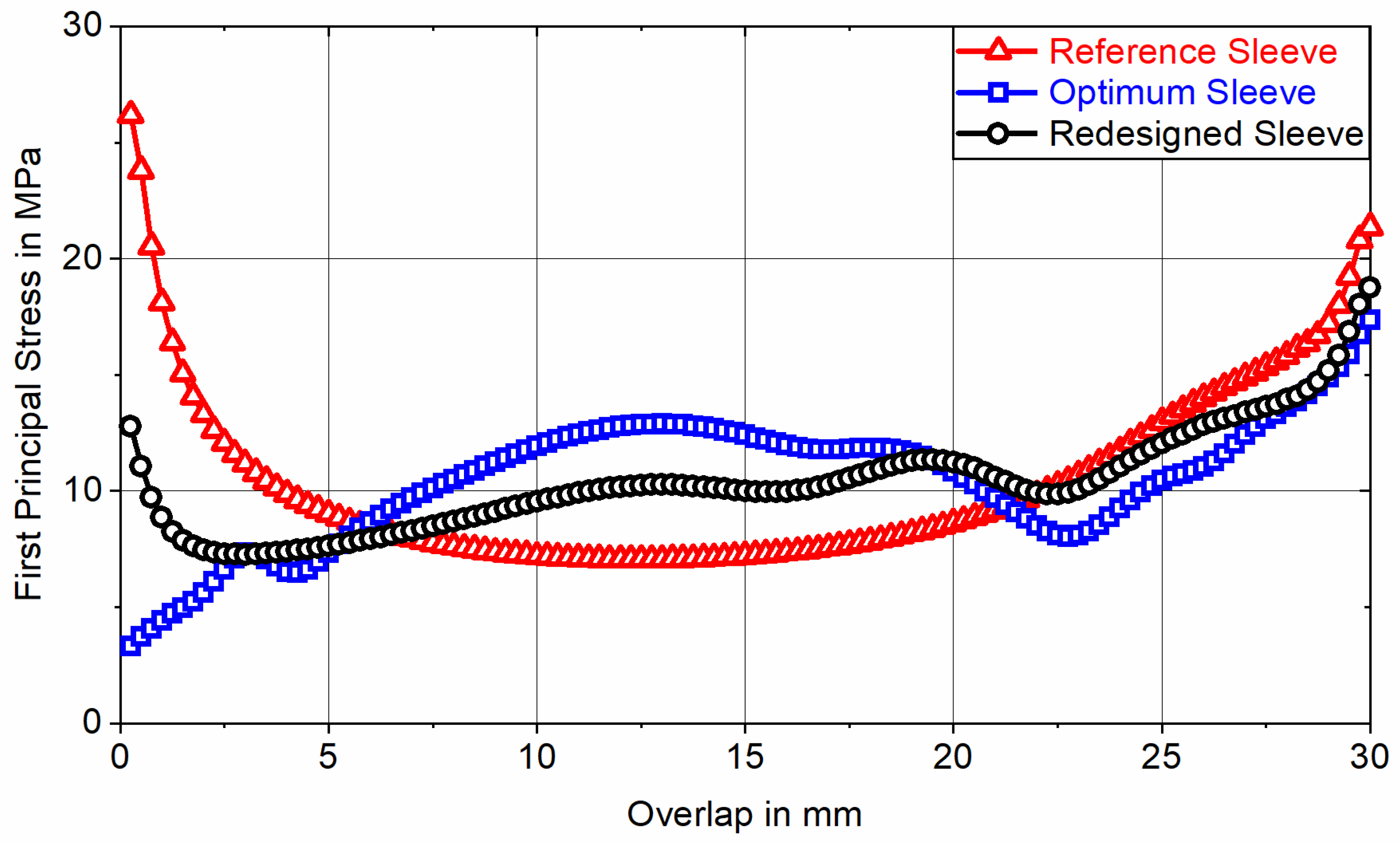

To quantify the resulting adhesive stress state, the optimum sleeve topology is FE analyzed at tensile loads of

and

, corresponding to nominal adhesive shear stresses of

(nonlinear) and

(linear) and the first principal stress is evaluated for all 120 elements representing the adhesive layer along the overlap (

-direction) at adhesive mid-thickness (in the fifth of eight element rows representing the adhesive layer in positive

-direction). For classification, this result is contrasted with the course of the first principal stress induced by a redesigned sleeve and a non-optimized cylindrical reference sleeve having an outer diameter of

. The redesigned sleeve is based on the optimum topology but considering manufacturing constraints related to the PBF-LB/M process. The redesign was generated based on the contour plot of optimum ED using computer-aided design (CAD) software (

Dassault Systèmes, CATIA V5). In doing so, the contours depicted where resketched (

neglected) and abstracted to comply with a minimum overhang angle of

and a minimum wall thickness of

[

2,

27]. Subsequently the sketch was rotated over an angle of

to form a solid body, which served as a basis for the ensuing FE analysis. Both the FE-based stress analyses and the TOP procedure were conducted using commercially available FE software (

Altair Engineering, HyperWorks 2021) with the

OptiStruct solver.

To experimentally quantify the bond strength of redesigned and reference sleeves, static tensile and fatigue tests were performed using a total of

bonded tensile samples. These include four redesigned and four cylindrical reference sleeves for conducting static tensile tests, as well as eight redesigned sleeves and eight cylindrical reference sleeves for conducting fatigue tests. The sleeves were manufactured using a

DMG MORI LASERTEC 30 SLM 2nd Generation PBF-LB/M additive manufacturing machine. The associated manufacturing parameters are depicted in

Table 2.

Commercially available AlSi10Mg powder (EN-AC 43000 as specified in [

28]) with a particle size between

and

was used throughout. To suppress influences on the surface roughness caused by varying component orientation and to ensure consistency with the material parameters provided in

Table 1, the AlSi10Mg sleeves were manufactured vertically oriented (longitudinal axis perpendicular to the build plate). The redesigned sleeve features radial slots with a slot opening angle of

to facilitate the removal of residual powder from the internal cavities. The maximum and minimum inner diameters of the

sleeves were determined to

and

by optical measurement using a 3D laser scanning microscope (

Keyence, VK-X 3000). Commercially available roll-wrapped unidirectional CFRC tubes with nominal dimensions of

were used as inner adherents. They offer a HT fiber content of

and a ground outer surface finish. The tubes maximum and minimum inner diameters were determined to

and

using a digital outside micrometer (

Mitutoyo, Absolute Digimatic 2). A 2C-Epoxy structural adhesive (

3M Scotch-Weld, DP490) was used to adhesively bond the inner and outer adherend. Based on the measured inner sleeve and outer tube diameters the actual adhesive layer thickness ranges from

to

with an arithmetic mean of

.

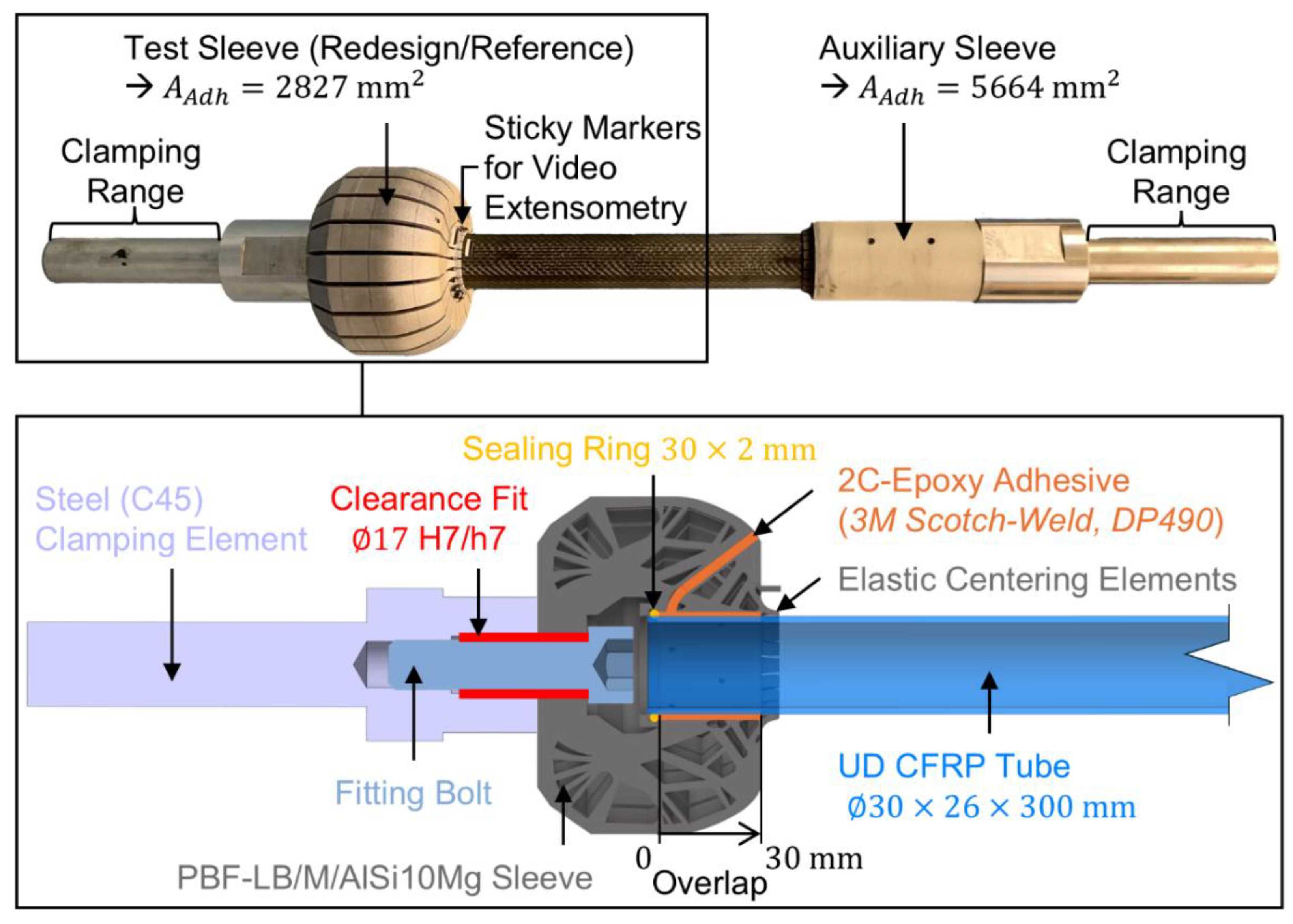

Figure 2 shows a schematic of a test sleeve (bottom) and an exemplary entire tensile test sample (top).

The preceding steps up to the completion of the bonded tensile test sample were as follows: After separating the de-powdered sleeves from the build plate using a band saw, the bottom surface was faced on a lathe. Then the adhesive surface of the sleeves was grid blasted with corundum (F200), cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with isopropanol, rinsed and dried. Subsequently the sleeves were bolted to steel clamping elements using a special fitting bolt to ensure concentrical alignment. Next a sealing ring (

) was inserted into a designated groove within the sleeve, followed by the CFRC tube which is concentrically aligned with the sleeve by the sealing ring at the bottom and elastic centering elements integrated at the top of the sleeve. The adhesive surface of the CFRC tube was mechanically treated using abrasive fleece (

Scotch-Brite, CF-HP 7447), followed by cleaning with isopropanol, before being inserted into the sleeve. Now the adhesive was injected, filling the adhesive fill gap between the adherends according to [

29] and [

30]. For hardening, the samples were stored in a climatic chamber for two hours at

and then conditioned to standard climate (

) for at least

hours. For clamping the CFRC tube in the test machine, a cylindrical auxiliary sleeve overlapping the tube by

was employed. Given the doubled adhesive surface area relative to the test sleeve, failure of the auxiliary sleeve’s adhesive bond is highly improbable.

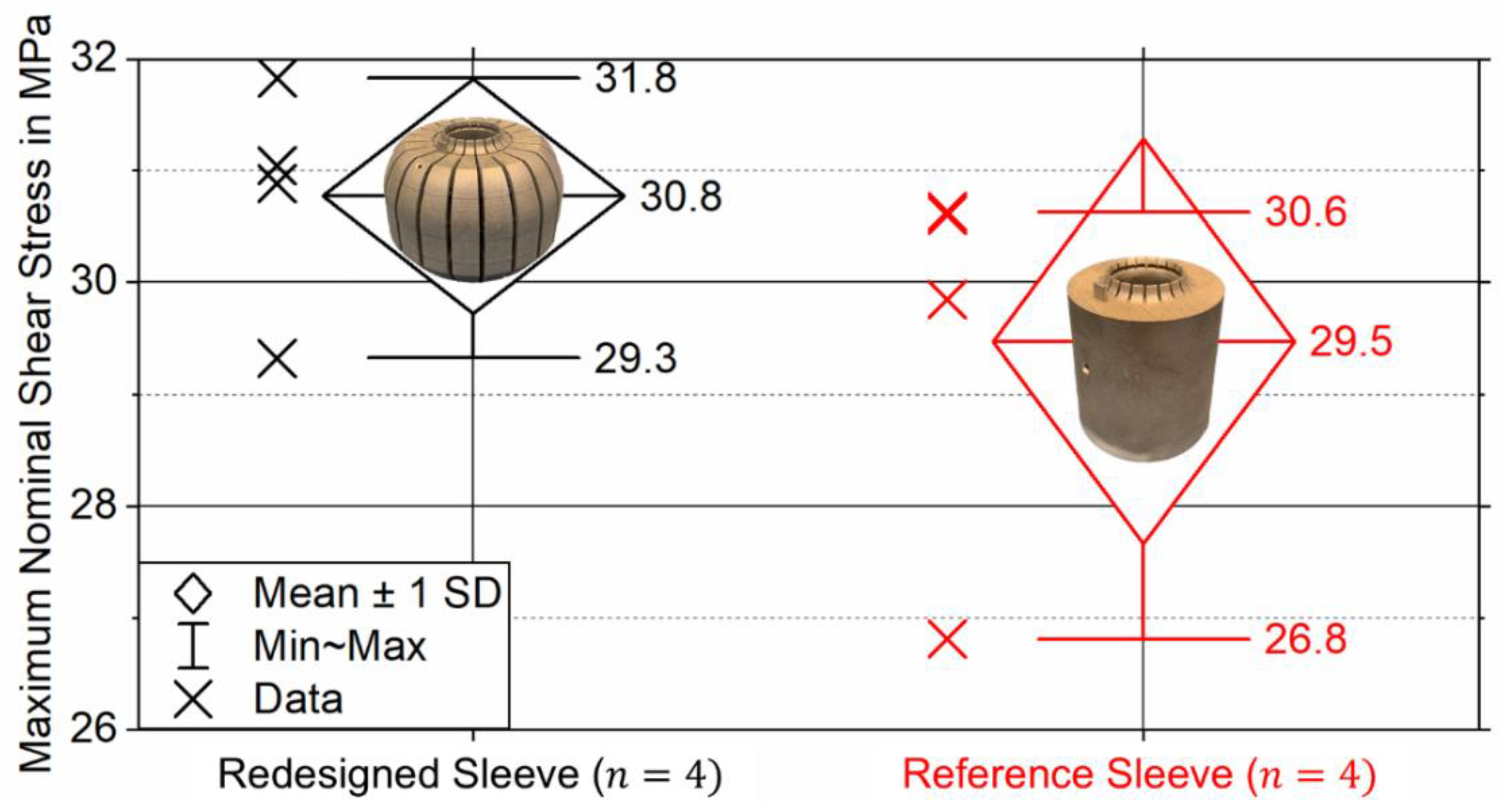

The static tensile tests were carried out using a

servo-hydraulic tensile testing machine (

Schenck, Trebel). The bonded samples were fixed over a clamping range of

using wedge grips. To steadily increase the load on the joint, the testing machine was operated displacement controlled with a constant test speed of

[

31]. The test results are documented in the form of nominal shear stress versus machine stroke diagrams, from which the maximum measured nominal adhesive shear stress (static bond strength) is determined by relating the maximum force measured to the sleeve´s adhesive surface area

. A video extensometer (

LIMESS, RTSS) was used to measure the

-strain between two high-contrast sticky markers applied to the lateral surfaces of the CFRC tube and the AlSi10Mg sleeves (see

Figure 2, top). To validate the FE model, the corresponding

-strain was determined by means of nonlinear FE analysis by evaluating the difference in

-displacement between elemental nodes positioned at the same locations as the contrast lines of the sticky markers. Up to a nominal shear stress of

, the stress-strain response obtained from tensile testing aligns well with the results of the nonlinear FE analysis for joints featuring cylindrical reference sleeves, supporting the validity of the FE model (see

Appendix A).

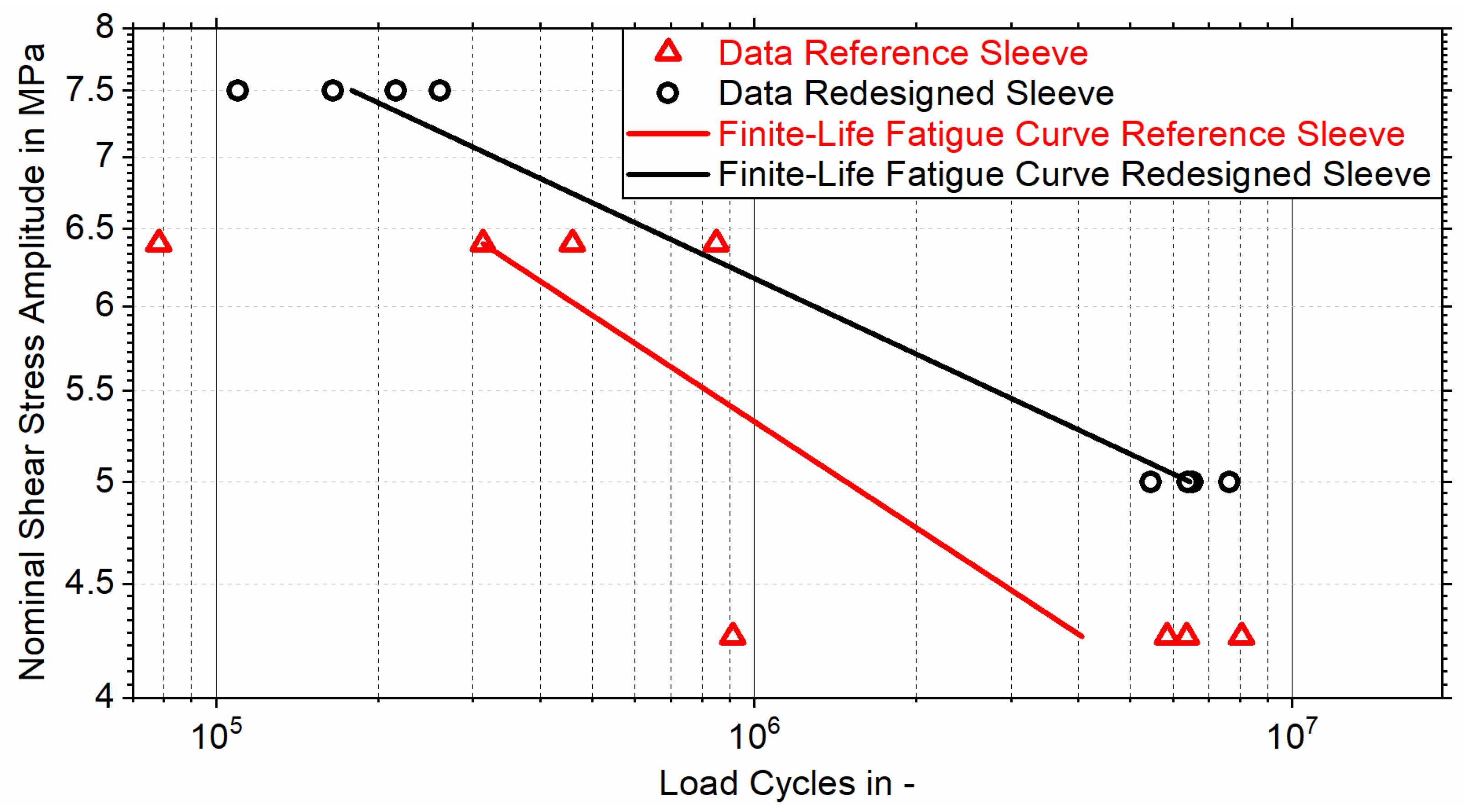

The fatigue strength of the joints was determined through pulsating tensile fatigue tests using an

SincoTec Power Swing electromechanical resonance testing machine, where eight bonded tensile samples with redesigned test sleeves were subjected to cyclic tensile loading with sinusoidal progression at nominal shear stress amplitudes of

or

, while eight bonded tensile samples with reference test sleeves were subjected to nominal shear stress amplitudes of

and

. All tests were conducted with identical stress ratios of

and test (resonance) frequencies ranging from

to

. Four tensile samples were subjected to each stress amplitude and the number of load cycles endured was counted until the maximum endurable stress of the test sleeve’s adhesive bond dropped below

of the respective maximum stress

. The load amplitudes were determined during preliminary tests to ensure that the number of endurable load cycles ranges from

to

. Accordingly, the results can be presented in a Wöhler (S-N) diagram, where a finite-life fatigue curve for each sleeve is evaluated at a

failure probability using the horizontal method [

32].

4. Discussion

The results of the FE stress analysis of the optimum and redesigned sleeve indicate that, due to the abstraction of the optimum sleeve’s contours in favor of PBF-LB/M manufacturability, the resulting redesigned sleeve demonstrates reduced performance in achieving a homogeneous adhesive shear stress distribution compared to the optimum sleeve. As the advantages of the optimum sleeve topology are associated with the nominal adhesive shear stress considered during the optimization process, the difference in performance between optimum and redesigned sleeve topologies decreases for load conditions deviating from the one considered in the optimization process. Upon comparing the results obtained for FE stress analysis of the non-optimized reference sleeve with the redesigned sleeve, it was found that the maximum adhesive stress increase induced by the reference sleeve exceeds the maximum adhesive stress increase of the redesigned sleeve by

for loading with

and by

for loading with

. This shows that the benefits of the redesigned sleeve in terms of achieving a homogenous adhesive stress distribution become more pronounced at lower loads, as for reduced adhesive ductility, the ability to relieve stress increases through adhesive yielding is limited. The significant influence of the adhesive plasticity on performance of optimized adherend geometry is also evident when comparing the

peak peel stress reduction between optimum and reference sleeve topologies evaluated in this study to the

peak peel stress reduction obtained for TOP of a rectangular SLJ using an energy-based failure criterion in [

19]. As in [

19] adhesive plasticity was neglected in the corresponding FE analysis, the total peak peel stress reduction between optimum and reference geometry exceeds that obtained in this study by almost a factor of two.

In the course of static tensile tests using bonded tensile samples featuring redesigned and reference sleeves, there was no difference in bond strength demonstrable. The discrepancy between the numerical and experimental results can be attributed to underestimation of the adhesive’s ductility in the FE model. Once the adhesive’s ultimate strength of

is exceeded, the final slope of the multilinear stress-strain curve (as presented in

Table 1) is extrapolated and, consequently, accounts for all stress-strain conditions beyond the ultimate strength. Assuming perfect plasticity of the adhesive after surpassing its ultimate strength would significantly reduce numerical stress increases for all sleeve topologies. A more accurate representation of the joint´s structural failure behavior could also be achieved by incorporating fracture mechanics into the FE model using CZM. As shown in [

12], by implementing cohesive zone elements at the interfaces between adhesive and adherents their degradation based on a traction-separation law could be captured, resulting in more accurate stress-strain prediction for ductile adhesives at higher loads [

34].

Since the adhesive exhibits minimal plasticization during pulsating ( fatigue tests at loading with nominal shear stress amplitudes between and , a correlation between the numerical adhesive stress increase and the corresponding service live was captured. The finite-life fatigue curves of tubular joints with redesigned and reference sleeves show that, as the load decreases, adhesive plasticization diminishes, resulting in a fourfold increase in service life of the redesigned sleeve compared to the reference sleeve at a shared load amplitude of .