Submitted:

30 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

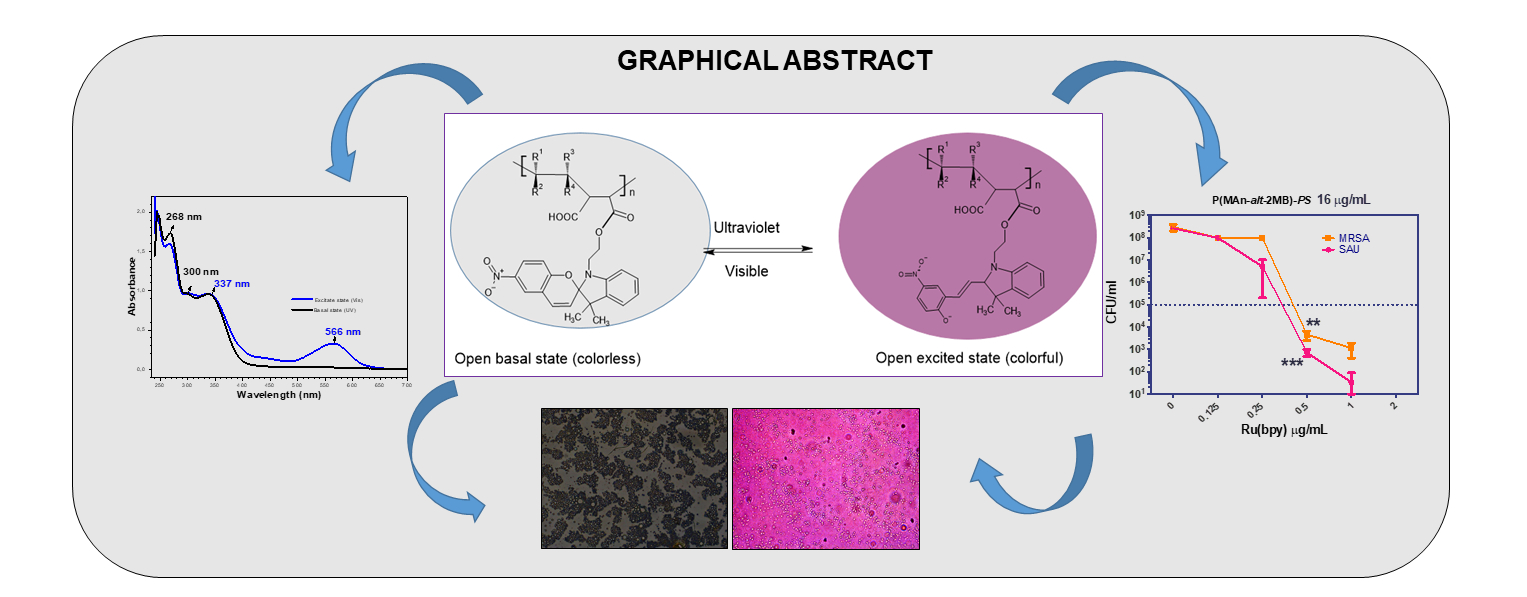

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Part

2.1. Characterization

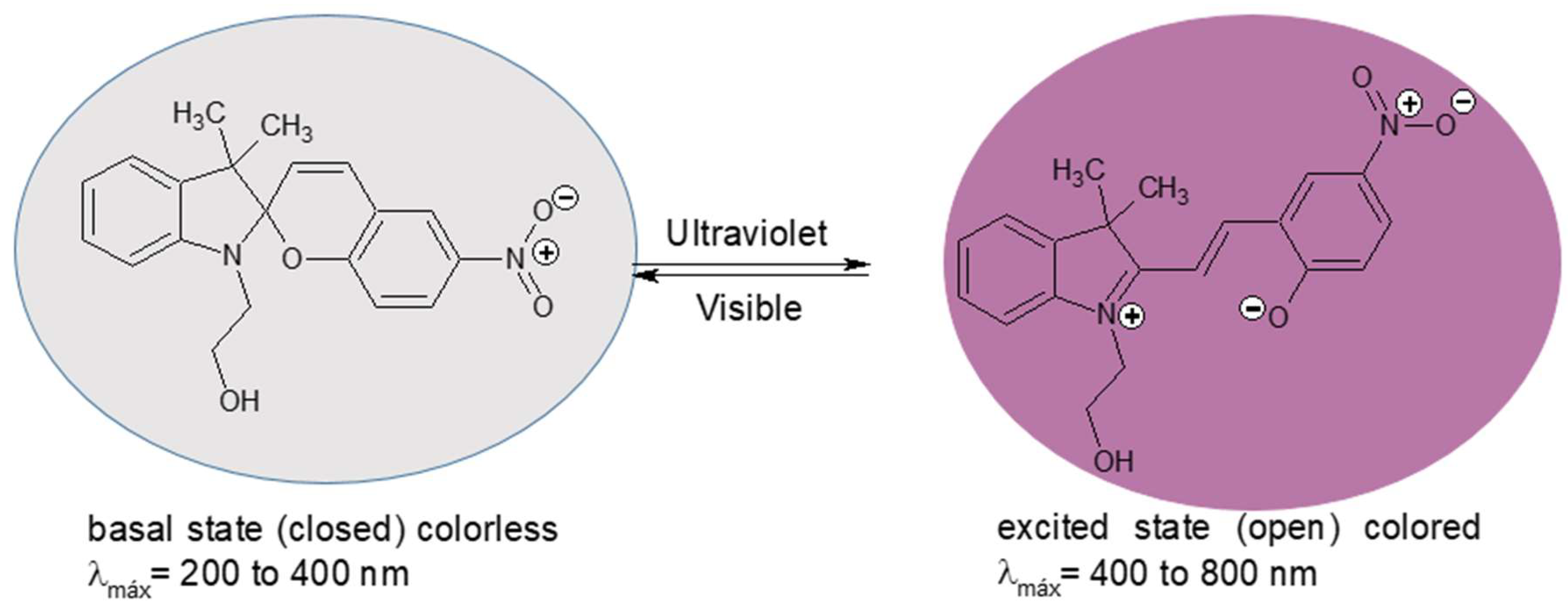

2.2. Procedure of Photochromic Agent Synthesis

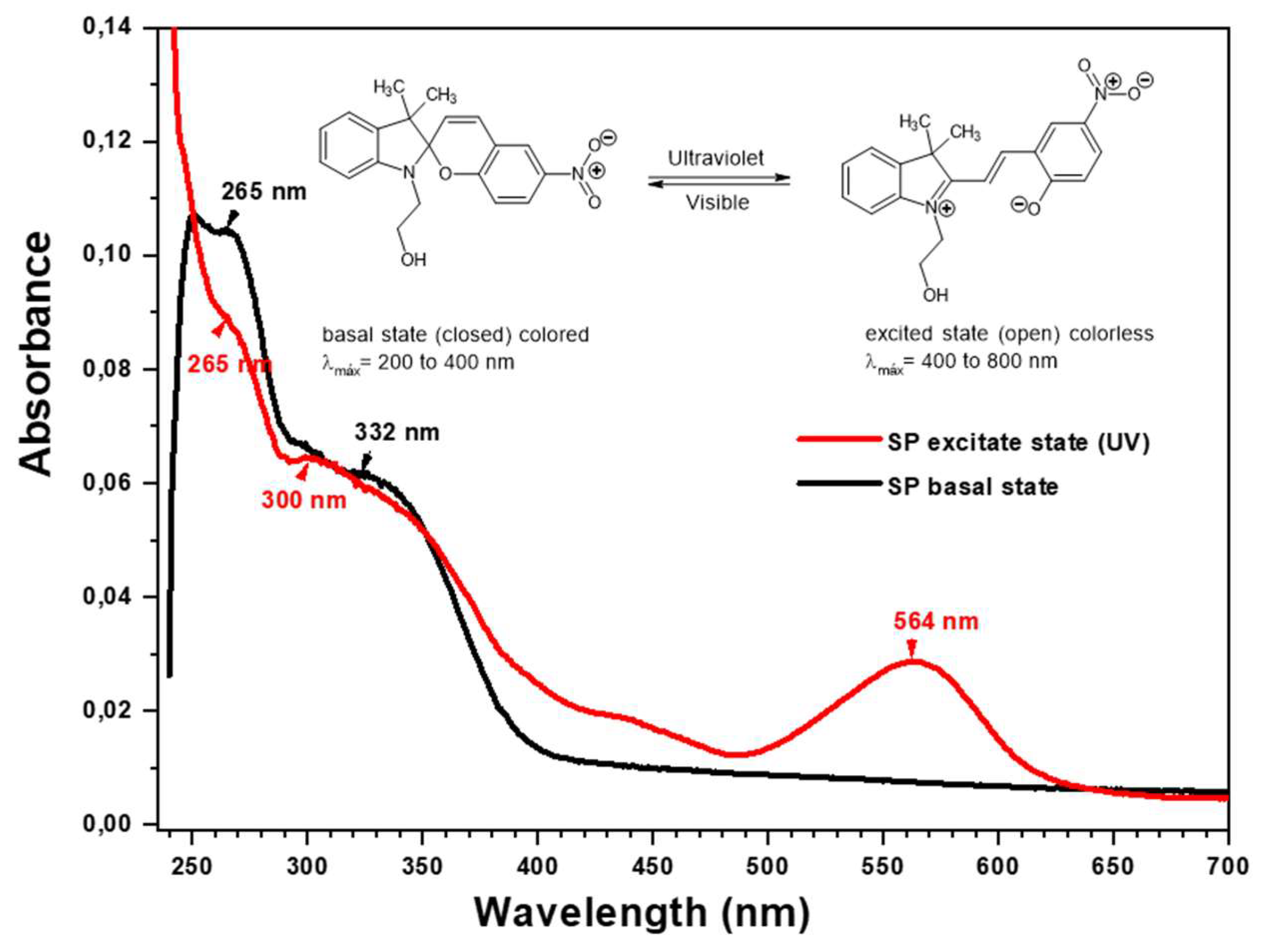

2.3. Characterization by UV-Visible Spectrophotometry

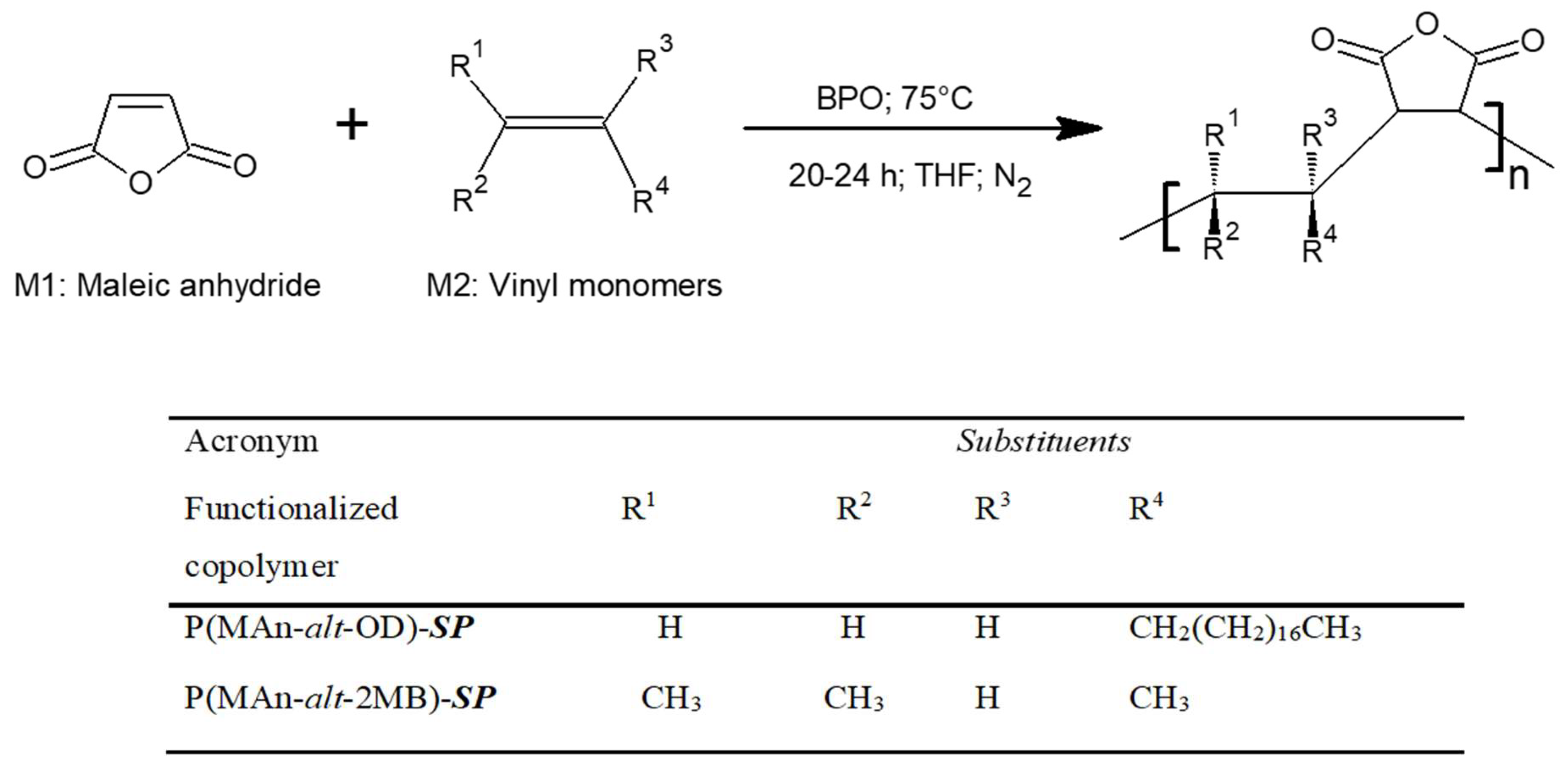

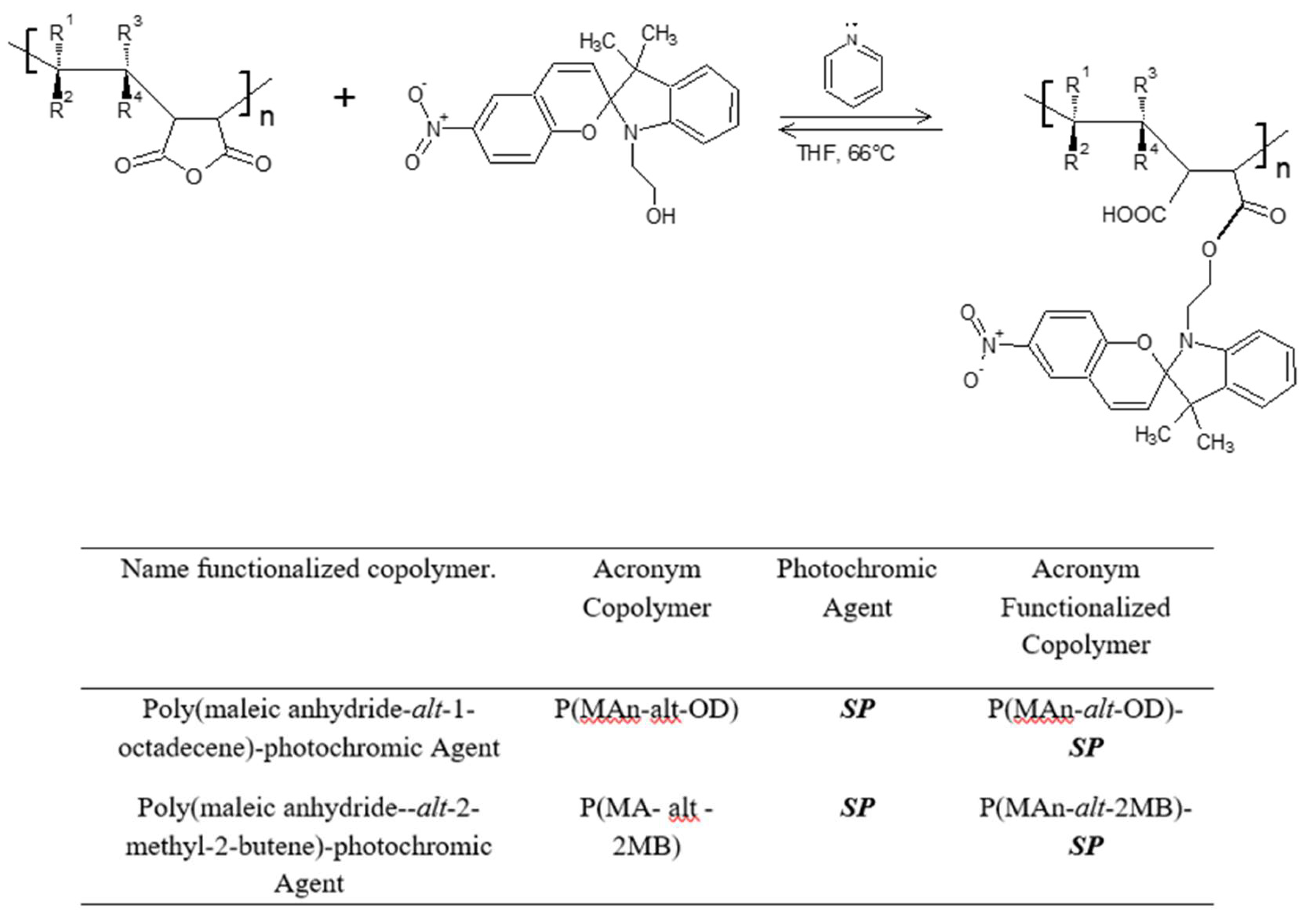

2.4. Preparation of Photoactive Alternating Copolymer

2.5. Determination of the Antimicrobial Photodynamic Property

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Alternating Copolymer

3.1.1. The Characterization by FT-IR and 1H-NMR

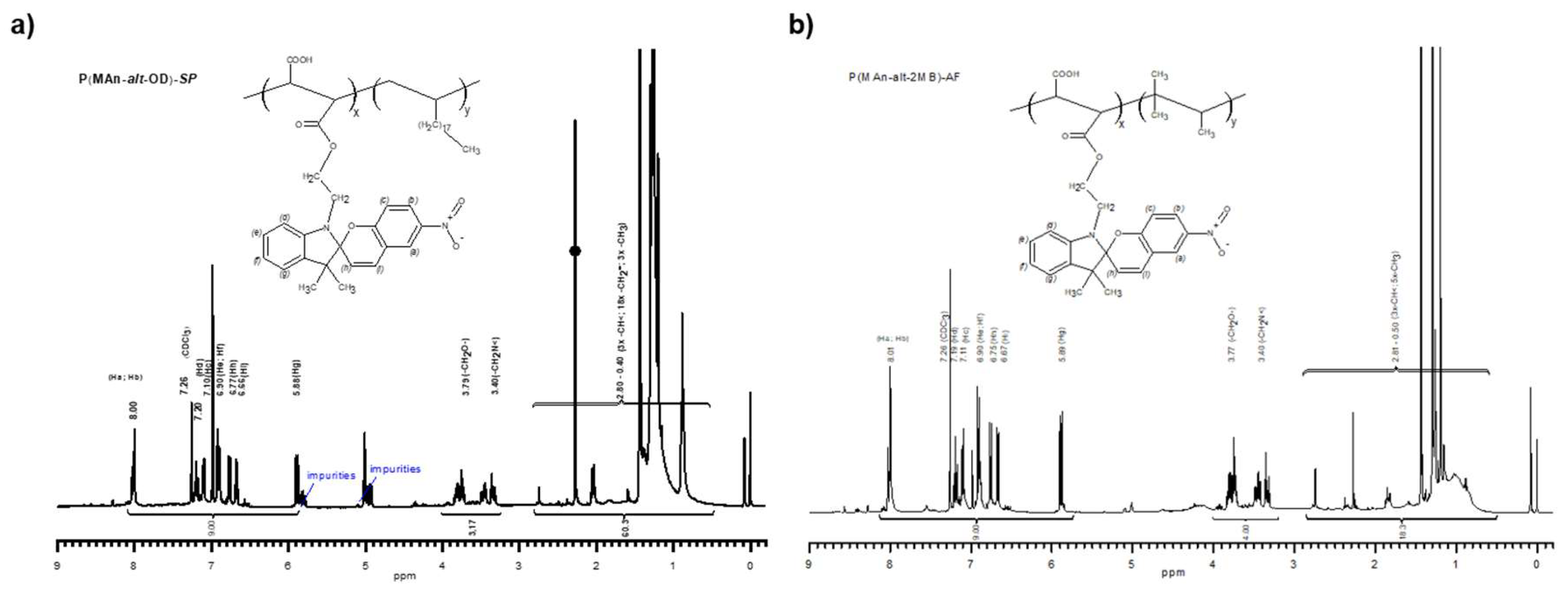

3.1.2. Characterization by NMR 1H- of the Copolymers P(MAn-alt-OD)-SP and P(MAn-alt-OD)-SP

3.1.3. Degrees of Functionalization (Copolymer Composition)

- = Number of aliphatic protons in the fraction X.

- = Number of aliphatic protons in the fraction Y

- = Number of methylene protons

- = Number of aromatic protons

- = Integral aliphatic protons

- = Integral aromatic protons

- = Integral methylene protons

- = Numerical value, mathematical operation of η1, η2, η4, ,.

- = Numerical value, mathematical operation of η1, η2, η3, ,

- : Comonomer fraction in X

- : Comonomer fraction in Y

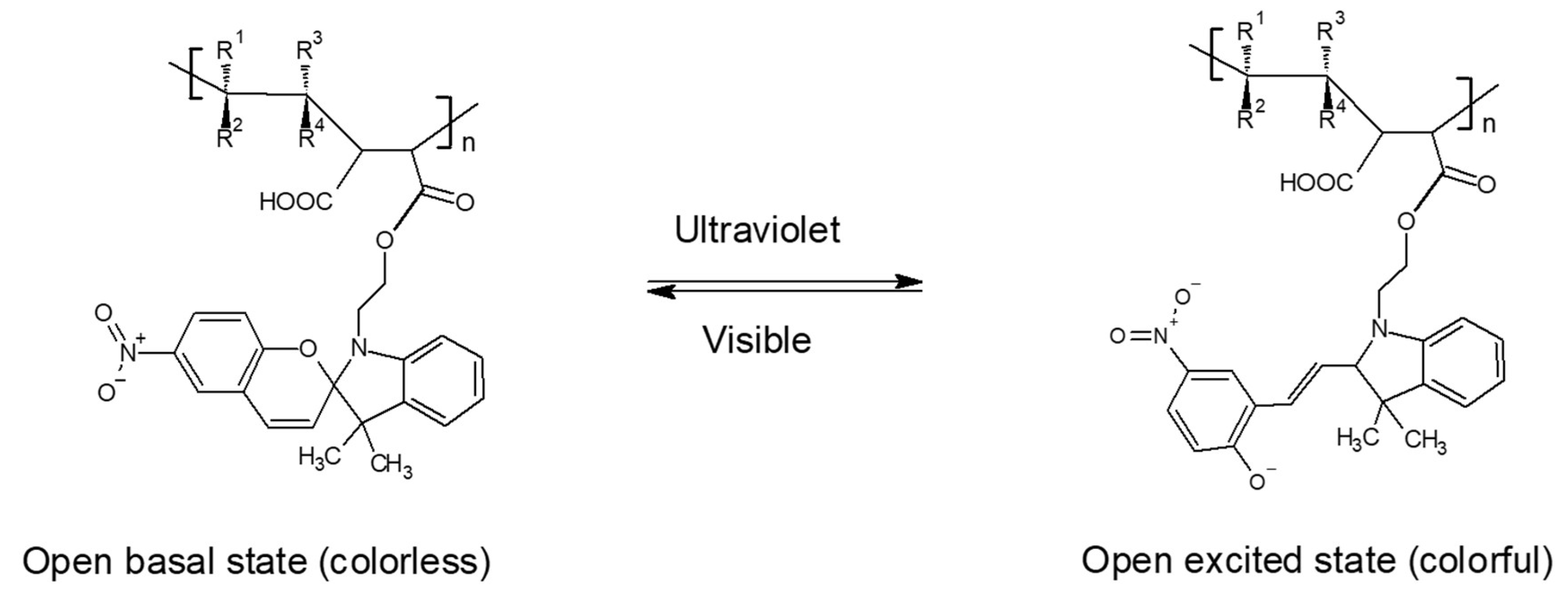

3.1.4. Functionalization of P (MAn-alt-OD)-SP and P(MAn-alt-2MB)-SP

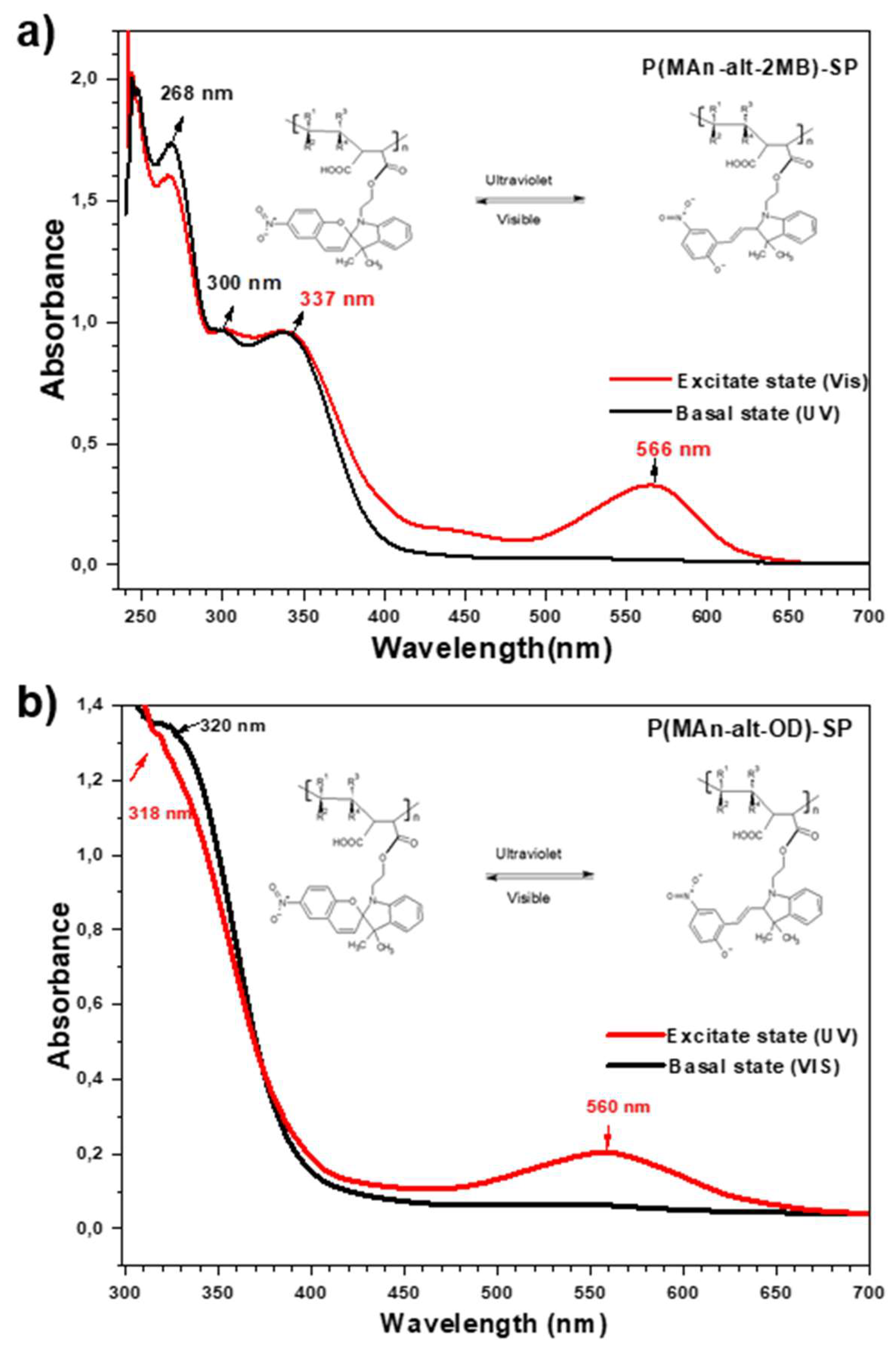

3.1.5. Characterization by UV-Visible Spectrophotometry

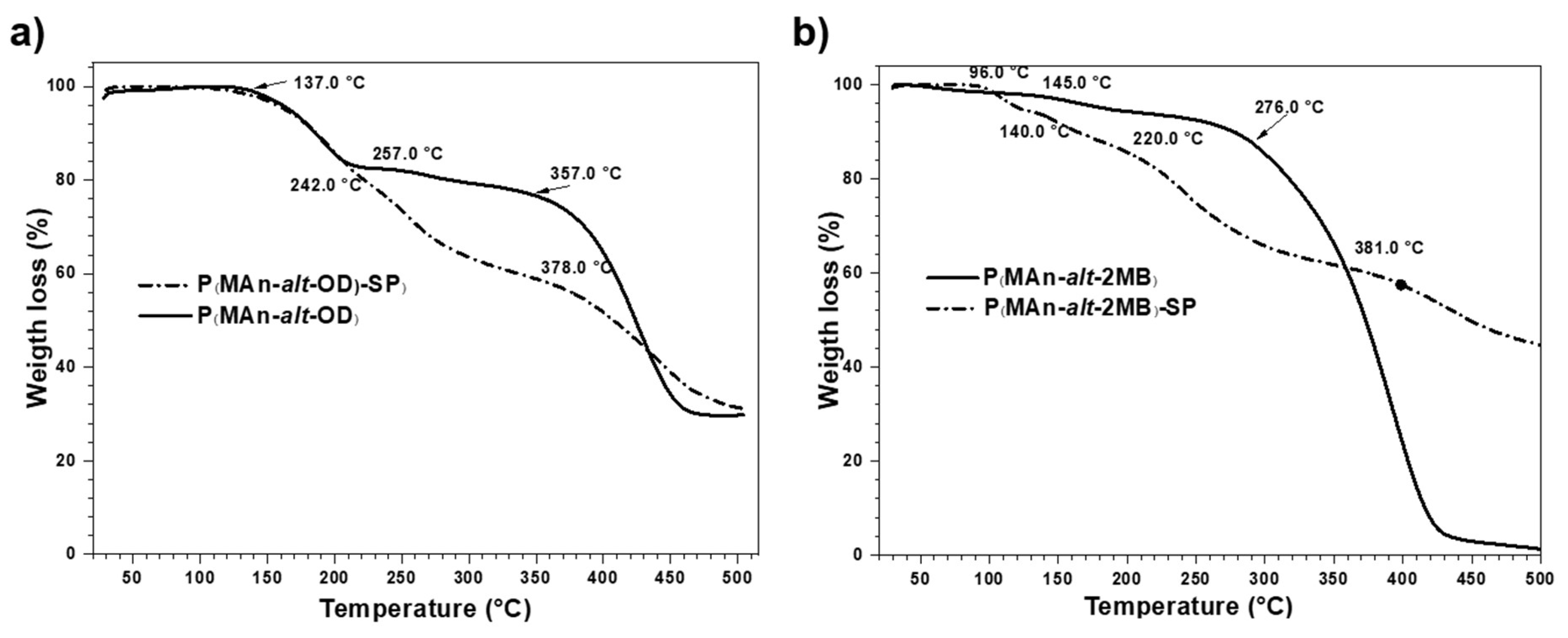

3.2. Thermal Decomposition Analysis by TGA

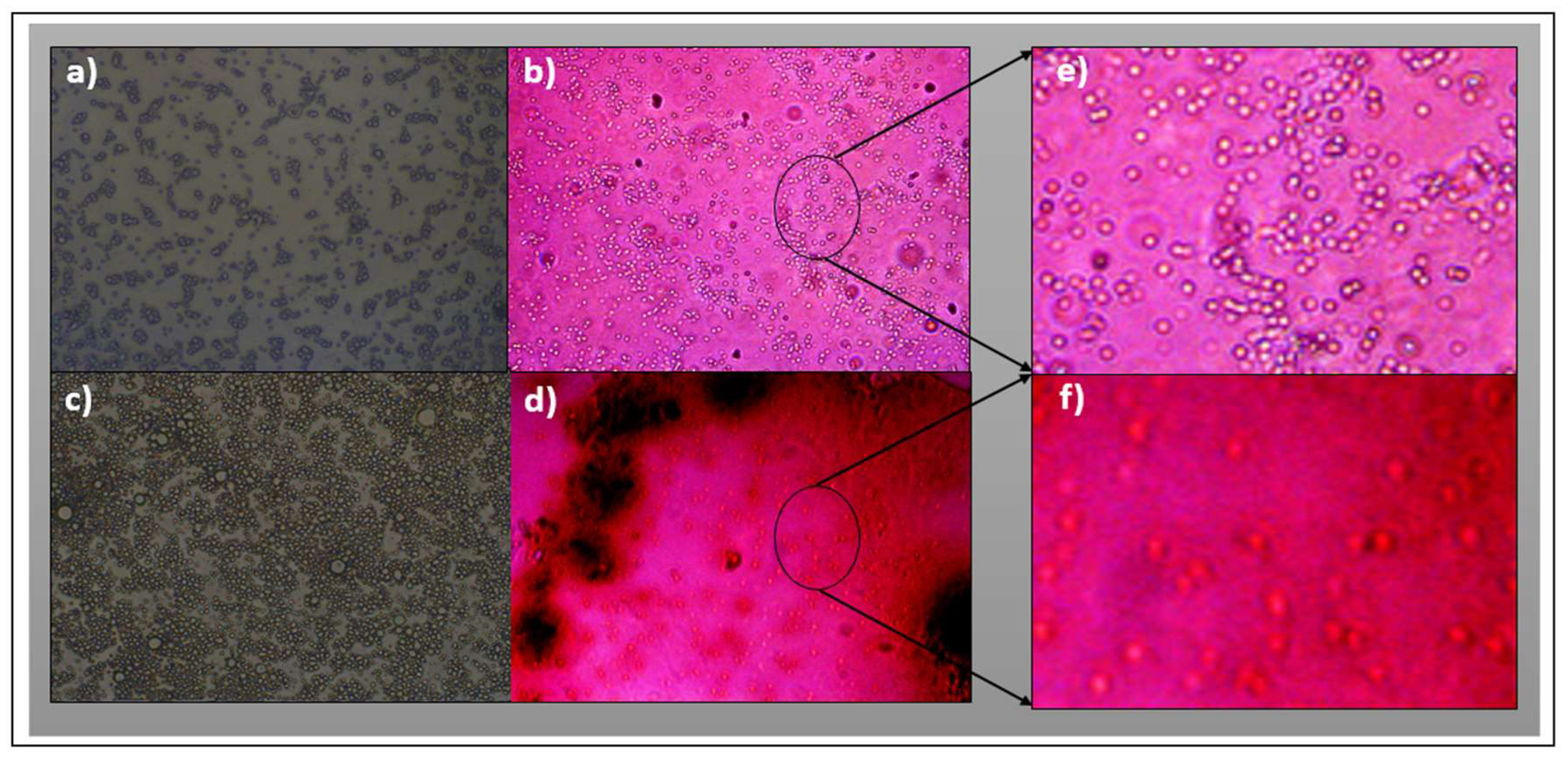

3.3. Characterization by Fluorescence Optical Microscopy

3.4. Determination of Antimicrobial Properties Based on Photodynamic Therapy (PDT).

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Paras, N.; Prasad, D. J. W. Introduction_to_Nonlinear_Optical_Effect, ilustrada; Wiley, 1991; Ed. [Google Scholar]

- García, A. E.; Elizalde, L. E.; Guillén, L.; De los Santos, G.; Medellín, D. I. Síntesis y evaluación fotocromática de compuestos espirobenzopiránicos. J Mex Chem Soc 2004, 48, 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Angiolini, L.; Benelli, T.; Giorgini, L.; Raymo, F. M. Chiroptical Switching Based on Photoinduced Proton Transfer between Homopolymers Bearing Side-Chain Spiropyran and Azopyridine Moieties. Macromol Chem Phys 2008, 209(19), 2049–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de los Santos, G.; Elizalde, L. E.; Castro, B.; García, A. E.; Medellín, D. I. Sociedad Química de México : [Revista]. Revista de la Sociedad Química de México 1996, 48, 332–337. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, S. P.; Behzad, A. R.; Hooghan, B.; Sougrat, R.; Karunakaran, M.; Pradeep, N.; Vainio, U.; Peinemann, K.-V. Switchable PH-Responsive Polymeric Membranes Prepared via Block Copolymer Micelle Assembly. ACS Nano 2011, 5(5), 3516–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilke, R.; Pradeep, N.; Madhavan, P.; Vainio, U.; Behzad, A. R.; Sougrat, R.; Nunes, S. P.; Peinemann, K. V. Block Copolymer Hollow Fiber Membranes with Catalytic Activity and PH-Response. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2013. [CrossRef]

- Amado, F. D. R.; Gondran, E.; Ferreira, J. Z.; Rodrigues, M. A. S.; Ferreira, C. A. Synthesis and Characterisation of High Impact Polystyrene/Polyaniline Composite Membranes for Electrodialysis. J Memb Sci 2004, 234, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnhoven, J. E. G. J.; Vos, W. L. Preparation of Photonic Crystals Made of Air Spheres in Titania. Science (1979) 1998, 281(5378), 802–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imada, M.; Noda, S.; Chutinan, A.; Tokuda, T.; Murata, M.; Sasaki, G. Coherent Two-Dimensional Lasing Action in Surface-Emitting Laser with Triangular-Lattice Photonic Crystal Structure. Appl Phys Lett 1999, 75(3), 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KATSONIS, N.; LUBOMSKA, M.; POLLARD, M.; FERINGA, B.; RUDOLF, P. Synthetic Light-Activated Molecular Switches and Motors on Surfaces. Prog Surf Sci 2007, 82, 407–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugel, T.; Holland, N. B.; Cattani, A.; Moroder, L.; Seitz, M.; Gaub, H. E. Single-Molecule Optomechanical Cycle. Science (1979) 2002, 296(5570), 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R. J.; Stitzel, S. E.; Diamond, D. Photo-Regenerable Surface with Potential for Optical Sensing. J Mater Chem 2006, 16(14), 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kwon, T.; Kim, E. Electropolymerization of an EDOT-Modified Diarylethene. Tetrahedron Lett 2007, 48(2), 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymo, F. M.; Tomasulo, M. Optical Processing with Photochromic Switches. Chemistry – A European Journal 2006, 12, 3186–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, I.; Deniz, E.; Raymo, F. M. Fluorescence Modulation with Photochromic Switches in Nanostructured Constructs. Chem Soc Rev 2009, 38(7), 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkovic, G.; Krongauz, V.; Weiss, V. Spiropyrans and Spirooxazines for Memories and Switches. Chem Rev 2000, 100(5), 1741–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samat, A.; Lokshin, V. Thermochromism of Organic Compounds. In Organic Photochromic and Thermochromic Compounds; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston; pp. 415–466. [CrossRef]

- Heiligman-Rim, R.; Hirshberg, Y.; Fischer, E. 29. Photochromism in Some Spiropyrans. Part III. The Extent of Phototransformation. Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed) 1961, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. Z. A.; Nazri, S. A. A. A.; Zainuddin, M. T.; Islam, N. Z. M.; Aziz, N. M. A. N. A.; Isha, K. M. Effects of Papain Incorporation on the Photo-Transformation Stability of 5-Bromo-8-Methoxy-6-Nitro Bips. Adv Mat Res 2014, 879, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.; Byrne, R.; Zanoni, M.; Gambhir, S.; Dennany, L.; Breukers, R.; Higgins, M.; Wagner, P.; Diamond, D.; Wallace, G. G.; Officer, D. L. A Multiswitchable Poly(Terthiophene) Bearing a Spiropyran Functionality: Understanding Photo- and Electrochemical Control. J Am Chem Soc 2011, 133(14), 5453–5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, I.; Willner, B. Layered Molecular Optoelectronic Assemblies. J Mater Chem 1998, 8(12), 2543–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, I.; Willner, B. Photoswitchable Biomaterials as Grounds for Optobioelectronic Devices. Bioelectrochemistry and Bioenergetics 1997, 42(1), 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmagnani, S.; Walsh, Z.; Slater, C.; Alhashimy, N.; Paull, B.; Macka, M.; Diamond, D. Polystyrene Bead-Based System for Optical Sensing Using Spiropyran Photoswitches. J Mater Chem 2008, 18(42), 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahsoune, M.; Boutayeb, H.; Zerouali, K.; Belabbes, H.; El Mdaghri, N. Prévalence et État de Sensibilité Aux Antibiotiques d’Acinetobacter Baumannii Dans Un CHU Marocain. Med Mal Infect 2007, 37(12), 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R. B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M. E.; Giske, C. G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J. F. Bacteria : An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T. R.; Yi, L.-X.; Zhang, R.; Spencer, J.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.; Dong, B.; Huang, X.; Yu, L.-F.; Gu, D.; Ren, H.; Chen, X.; Lv, L.; He, D.; Zhou, H.; Liang, Z.; Liu, J.-H.; Shen, J. Emergence of Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Mechanism MCR-1 in Animals and Human Beings in China: A Microbiological and Molecular Biological Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16(2), 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczosa, M. K.; Mecsas, J. Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Going on the Offense with a Strong Defense. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2016, 80(3), 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W. C.; Paterson, D. L.; Sagnimeni, A. J.; Hansen, D. S.; Von Gottberg, A.; Mohapatra, S.; Casellas, J. M.; Goossens, H.; Mulazimoglu, L.; Trenholme, G.; Klugman, K. P.; McCormack, J. G.; Yu, V. L. Community-Acquired Klebsiella Pneumoniae Bacteremia: Global Differences in Clinical Patterns. Emerg Infect Dis 2002, 8(2), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhundi, S.; Zhang, K. Crossm. 2018, 31, 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Diekema, D. J.; Pfaller, M. A.; Schmitz, F. J.; Smayevsky, J.; Bell, J.; Jones, R. N.; Beach, M. Survey of Infections Due to Staphylococcus Species: Frequency of Occurrence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Isolates Collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific Region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillanc. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podschun, R.; Ullmann, U. Klebsiella Spp. as Nosocomial Pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998, 11(4), 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadasy, K. A.; Domiati-Saad, R.; Tribble, M. A. Invasive Klebsiella Pneumoniae Syndrome in North America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007, 45(3), e25–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulieri, S. G.; Tong, S. Y. C.; Williamson, D. A. Using Genomics to Understand Meticillin-and Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infections. Microb Genom 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, F.; Kang, J.; Wang, X.; Yin, D.; Dang, W.; Duan, J. Prevalence of Multidrug Resistant Gram-Positive Cocci in a Chinese Hospital over an 8-Year Period; 2015; Vol. 8. www.ijcem.com/.

- Pizarro, G.; Alavia, W.; González, K.; Díaz, H.; Marambio, O.; Martin-Trasanco, R.; Sánchez, J.; Oyarzún, D.; Neira-Carrillo, A. Design and Study of a Photo-Switchable Polymeric System in the Presence of ZnS Nanoparticles under the Influence of UV Light Irradiation. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14(5), 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Collins, J. G.; Keene, F. R. Ruthenium Complexes as Antimicrobial Agents. Chem Soc Rev 2015, 44(8), 2529–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymo, F. M.; Tomasulo, M. Electron and Energy Transfer Modulation with Photochromic Switches. Chem Soc Rev 2005, 34(4), 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymo, F. M.; Yildiz, I. Luminescent Chemosensors Based on Semiconductor Quantum Dots. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2007, 9(17), 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Hamblin, M. R. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy to Control Clinically Relevant Biofilm Infections. Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, D.; Choudhary, R. B. Augmented Optical and Electrical Properties of PMMA-ZnS Nanocomposites as Emissive Layer for OLED Applications. Opt Mater (Amst) 2019, 91, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Choudhary, R. B.; Kandulna, R. Optical Band Gap Tuning and Thermal Properties of PMMA-ZnO Sensitized Polymers for Efficient Exciton Generation in Solar Cell Application. Mater Sci Semicond Process 2019, 103, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, A. K.; Gupta, S.; Kumbhakar, P.; Ramamurthy, P. C. Nonlinear Optical Second Harmonic Generation in ZnS Quantum Dots and Observation on Optical Properties of ZnS/PMMA Nanocomposites. Opt Commun 2014, 313, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Maleic Anhydride (MAn) | COOH | Ester-COOR | -NO2 | ||

| Copolymer | Asymmetric (C=O) | Symmetrical (C=O) | Tension (C=O) | tension (C=O) | Tension (N-O) |

| P(MAn-alt-OD) | --- | 1780.0 | 1707.5 | --- | --- |

| P(MAn-alt-OD)-SP | --- | 1780.0 | --- | 1720.0 | 1460.0 |

| P(MAn-alt-2MB) | 1857.0 | 1780.0 | 1719.0 | --- | --- |

| P(MAn-alt-2MB)-SP | 1857.0 | 1780.0 | --- | 1728.0 | 1460.0 |

| Name | n1 | n2 | n3 | n4 | Ialiph | Imeth | Iar | X | Y |

| P(MAn-alt-OD)-SP | 8.00 | 10.0 | 4.00 | 9.00 | 48.0 | 6.06 | --- | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| P(MAn-alt -OD)-SP | 8.00 | 10.0 | 4.00 | 9.00 | 48.0 | --- | 2.53 | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| P(MAn-alt-2MB)-SP | 8.00 | 10.0 | 4.00 | 9.00 | 18.3 | 4.00 | --- | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| P(MAn-alt -2MB)-SP | 8.00 | 10.0 | 4.00 | 9.00 | 18.3 | --- | 9.00 | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| Compounds | λmax basal state (nm) | λmax excited state (nm) | |||||

| Photochromic agent | 265 | 332 | -- | 265 | 300 | -- | 564 |

| P(MAn-alt-OD)-SP | 320 | -- | -- | 318 | -- | -- | 560 |

| P(MAn-alt-2MB)-SP | 268 | 300 | 337 | 268 | 300 | 337 | 566 |

| Case | Eg (eV) | |

| before irradiation | after irradiation | |

| Photochromic agent (SP) | 3.00 | 2.00 |

| P(MAn-alt-OD)-SP | 3.73 | 3.02 |

| P(MAn-alt-2MB)-SP | 4.53 | 3.78 |

| * The Eg was estimated from Tauc plot equation41 , before and after irradiation at 365 nm. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).