1. Introduction

Ginger (Zingiber officinale), the herbaceous member of Zingiberaceae family, is one of the most commonly consumed and globally renowned dietary condiments (Surh, 1999). In addition to being a widely used spice derived from the plant's rhizome, it is also a popular folk medicine which is native to parts of Asia, including China, India, and Japan. Considering the far-extending biological properties of plant extracts with low toxicity, ginger has drawn appreciable interest among ethnopharmacologists and researchers world over. Interestingly, ginger is among the most investigated natural sources, drawing a large proportion of research publications in the last two decades (Garza-Cadena et al. 2023). Recent literature has also documented the innumerable benefits and potential of ginger in combating microbial infections and treatment of bodily ailments (Darekar et al. 2023). Multiple phytocompounds and metabolites have been identified in ginger extracts through chemical and metabolic investigations. Various nutraceuticals such as carbohydrates, proteins, amino acids, lipids, fatty acids, minerals, and vitamins have been identified in ginger extracts (Yang et al. 2024). Phytochemical profiling of ginger extracts has also revealed the presence of secondary metabolites like alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, glycosides, oxalates, phenols, steroids, and anthraquinones, which demonstrate health-promoting and immunity-enhancing properties (Fahmi et al. 2019; Ghafoor et al. 2020). The chemical components of ginger include both volatile oils and non-volatile pungent components. More than 50 volatile components have been successfully characterized in ginger, including sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (monoterpenes) consisting zingiberene, curcumene, and farnesene, while non-volatile components comprise phenolic compounds like gingerols, shogaols, paradols, and zingerone, responsible for its pharmacological activities (Li et al. 2019a). Interestingly, fresh ginger extracts constitute the latter phytochemicals except zingerone (ZiN), which forms gradually upon drying or cooking of ginger, reportedly via a retroaldol reaction of gingerol (Ahmad et al. 2015). This has been previously documented in a study wherein charring fresh ginger significantly increased zingerone levels (9.25%) in rhizome extracts, eventually lowering the content of 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, and 10-gingerol (Ahmad et al. 2015). Apart from ginger, ZiN is naturally emitted from the floral parts of certain Bulbophyllum sp., including B. patens and B. baileyi, functioning as a sex pheromone to attract fruit flies for pollination (Tan and Nishida, 2007). Although ginger contains a plethora of nutraceutical and bioactive components that display pharmacological properties, ZiN has been a subject of great relevance and scrutiny among researchers in recent years.

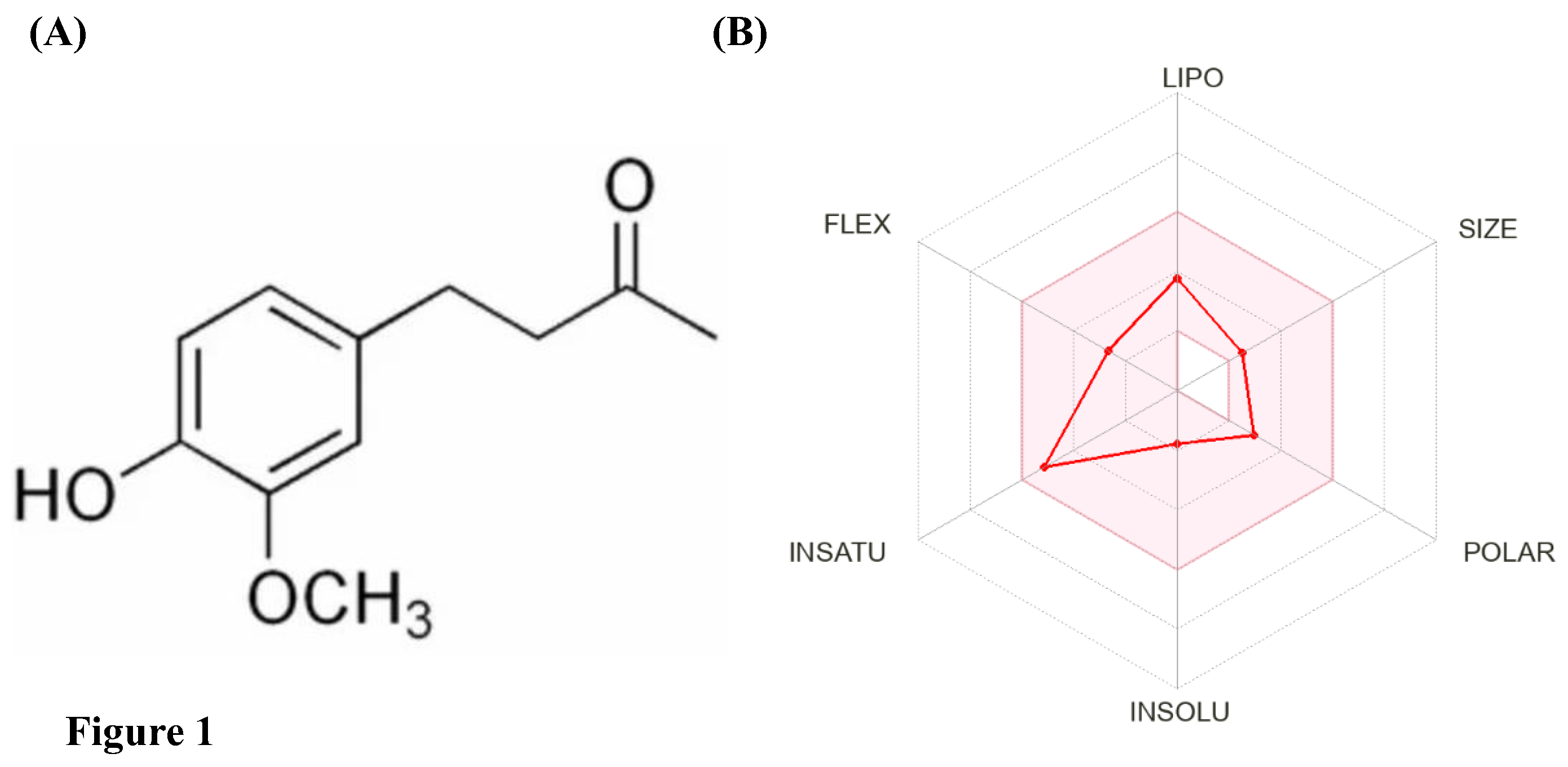

ZiN is a polyphenolic alkanone, commonly known as vanillyl acetone, with the IUPAC name: [4-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-butan-2-one] and chemical formula C

11H

14O

3 (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Zingerone). Structurally, it is a methyl ketone that is 4-phenylbutan-2-one, with methoxy- and hydroxy groups substituting the phenyl ring at positions 3 and 4, respectively (

Figure 1A). At room temperature, ZiN exists as a distinct yellowish-brown crystalline mass with a strong, pungent vanilla-like odor and a sharp sweet-spicy taste similar to ginger. It melts at 40.5°C and is sparingly soluble in water but dissolves readily in organic solvents like ethyl ether, chloroform, and dimethyl sulfoxide (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Zingerone). Some other molecular properties of ZiN have been enlisted in

Table 1. Additionally, bioavailability radar generated using SwissADME indicates that ZiN shows ideal drug-like properties and oral bioavailability since it obeys the Lipinski's rule for druglikeliness without any violation (

Figure 1B). ADMET profiling using the pkCSM server (

https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm/prediction) also provided more insights into the pharmacokinetic (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) and toxicity properties of ZiN, thereby affirming its drug-like properties (

Table 2). ZiN was predicted to have high absorption and distribution without inhibiting various cytochrome P450 subunits, exhibiting minimal excretion and low cytotoxicity in humans (

Table 2). In relation to the pharmacokinetics, a recent in vivo study evaluated the oral bioavailability, biotransformation, and excretion profiles of orally-administered ZiN (30 mg/kg body) in Sprague Dawley rats (Songvut et al. 2024). Interestingly, ZiN showed favorable tolerability in rats accompanied by rapid absorption, attaining peak plasma concentration within 4.8 mins post-oral administration and an absolute oral bioavailability of 1.6%. Moreover, ZiN was detected in significant amounts in the plasma of animals receiving only 6-gingerol (orally), indicating that the latter undergoes biotransformation through a metabolic pathway that generates ZiN (Songvut et al. 2024). Also, tissue distribution studies indicated that ZiN was prominently concentrated in the brain (cortex region and hippocampus) and organs of the digestive system, with a relatively higher tissue-to-plasma ratio, thereby undergoing minimal renal excretion (< 1%) in urine within 24-48 h of oral administration (Songvut et al. 2024). This strongly advocates the pharmacokinetic properties and drug-like potential of ZiN, which may be subsequently evaluated in humans. Nevertheless, there are myriads of studies that establish the multifaceted nature and far-extending biological effects of ZiN, including but not limited to its antivirulence, antifouling, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, antidiarrheal, antiemetic, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory capabilities. Hence, this review aims to provide an updated insight into the pharmacological prospects of ZiN, recapitulating the recent advances accomplished using multiple pre-clinical investigations (in vitro, in silico, and in vivo) and clinical trials. We also augment literature on the pharmaceutical formulations of ZiN that have been widely explored for therapeutic applications against various human diseases.

2. Biosynthesis and Metabolism of ZiN

Ginger contains several bioactive phytochemicals like gingerols, shogaols, and paradols, but surprisingly, ZiN is completely absent in freshly-prepared rhizome extracts (Mao et al. 2019). It is only produced upon subjecting ginger extracts to heating (charring), which results in the biotransformation of gingerols into ZiN through a reverse retro aldol decomposition and dehydration reaction (Ahmad et al. 2015). Although ZiN is a phytocomponent derived from ginger, its biosynthesis has also been documented in yeast (

Saccharomyces cerevisiae: YMDB01809), where it is an intermediate of an unidentified metabolic pathway (

https://www.ymdb.ca/compounds/YMDB01809). Accordingly, ZiN possesses disparate methods for production on an industrial scale. The first scalable process for manufacturing ZiN was patented by William J. Cotton in 1945 (US Patent: US2381210A), who demonstrated the efficient conversion of vanillalacetone into zingerone through hydrogenation in the presence of activated nickel catalyst. Furthermore, Svetaz et al. illustrated the biotransformation process of dehydrozingerone (precursor) for efficient production of ZiN (90%) using filamentous fungi like

Aspergillus fumigatus,

Geotrichum candidum, and

Rhizopus oryzae, yielding ZiN as the sole product within 8 hours of fermentation (Svetaz et al. 2014). Another study focused on genetically engineering

Escherichia coli ΔCOS4 strain (L-tyrosine-overproducer) for constructing artificial metabolic pathways directing ZiN production by promoting the heterologous expression of six genes,

viz. optal,

sam5,

com,

4cl2nt,

pmpks, and

rzs1. Using complete

de novo synthesis in the presence of ferulic acid, ZiN was produced from the recombinant

E. coli strain at a maximum yield of 24.03 ± 2.53 mg/L (Heo et al. 2021). More recently, Rawat and colleagues devised a two-step method for synthesizing ZiN from lignin-derived vanillin using aluminium phosphate and nickel supported on lignin residue-derived carbon catalysts (Rawat et al. 2022). The process was found to be efficient and cost-effective, allowing repeated recycling of the catalysts alongside supporting the idea of sustainability. In relation to its metabolism in rats, it was previously elucidated that ZiN (100 mg/kg body weight; orally) undergoes conjugation with glucuronic and/or sulfuric acids, yielding multiple metabolites that are excreted in bile juice within 12 h of administration (Monge et al. 2009). Interestingly, the authors also unraveled the role of rat caecal microbiota (anaerobic) in metabolizing and demethylating ZiN and its biliary metabolites using β-glucuronidase and

O-demethylase enzymes. In addition, orally-administered ZiN (30 mg/kg body weight) has been recently shown to undergo metabolism in rat liver via the Phase II metabolic pathway, thereby generating its conjugated form (zingerone glucuronide), which is released in biliary secretions and excreted slowly in urine within 24 hours of oral administration (Songvut et al. 2024).

3. Toxicity and Safety Profile of ZiN

The primary limitation concerning the application of bioactive phytochemicals in mainstream medicine is their cytotoxicity towards human cells. However, ZiN is reported to have a relatively lower toxicity profile and does not extend any off-target effects. In this context, the lethal dose 50 (LD

50) of ZiN, when administered orally in rats, was found to be 2580 mg/kg body weight (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Zingerone#section=Toxicological-Information). On similar lines, a recent study demonstrated the protective role of ZiN in mitigating carfilzomib-induced cardiotoxicity in rats, without extending any cytotoxic effects (Alam et al. 2022). Oral administration of ZiN (100 mg/kg body weight) did not alter the levels of hematological and biochemical markers, inflammatory cytokines, and most importantly caspase-3 (pro-apoptotic marker). Additionally, computational analysis (ADMET lab) also predicts that ZiN is negative (Category 0) for inducing Ames mutagenicity, human hepatotoxicity, drug-induced liver injury, and does not block pore-forming subunit (hERG) of potassium ion channel (

https://admet.scbdd.com/calcpre/index/#). Although ZiN exhibits skin sensitising potential, it has found application as an anti-aging ingredient in skincare products since it notably improves photodamage, and reduces dyspigmentation, redness, and appearance of wrinkles (Dhaliwal et al. 2020). Moreover, several clinical trials evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of ZiN are underway, which further corroborates the non-toxic profile, tolerance, and safety of this multifaceted phytochemical in humans.

4. Pharmacological Properties of ZiN: Insights from Pre-Clinical Studies

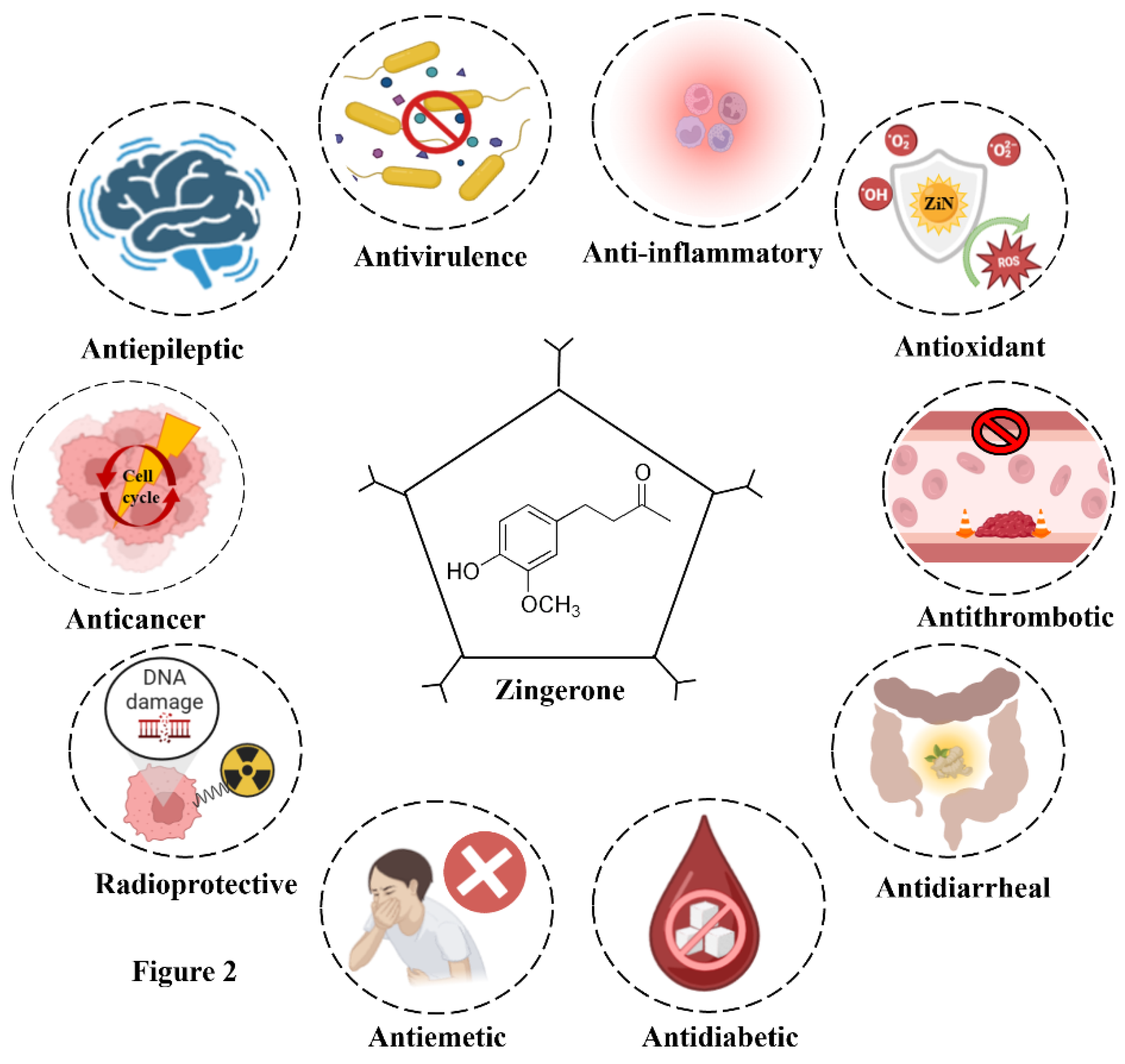

The natural origin, abundance, and safety profile of ZiN have further made it an attractive candidate for pre-clinical research and biomedical applications. Investigations are being conducted extensively to study how it can be used as a prophylactic agent against both microbial and lifestyle-based diseases. The pharmacological/biological prospects of ZiN have been illustrated in

Figure 2. The upcoming sections provide a more thorough description of ZiN's pharmacological properties and discuss the scientific evidences establishing its multifaceted nature.

4.1. Beyond the Antimicrobial Spectrum: Anti-Quorum Sensing and Antivirulence Prospects of ZiN

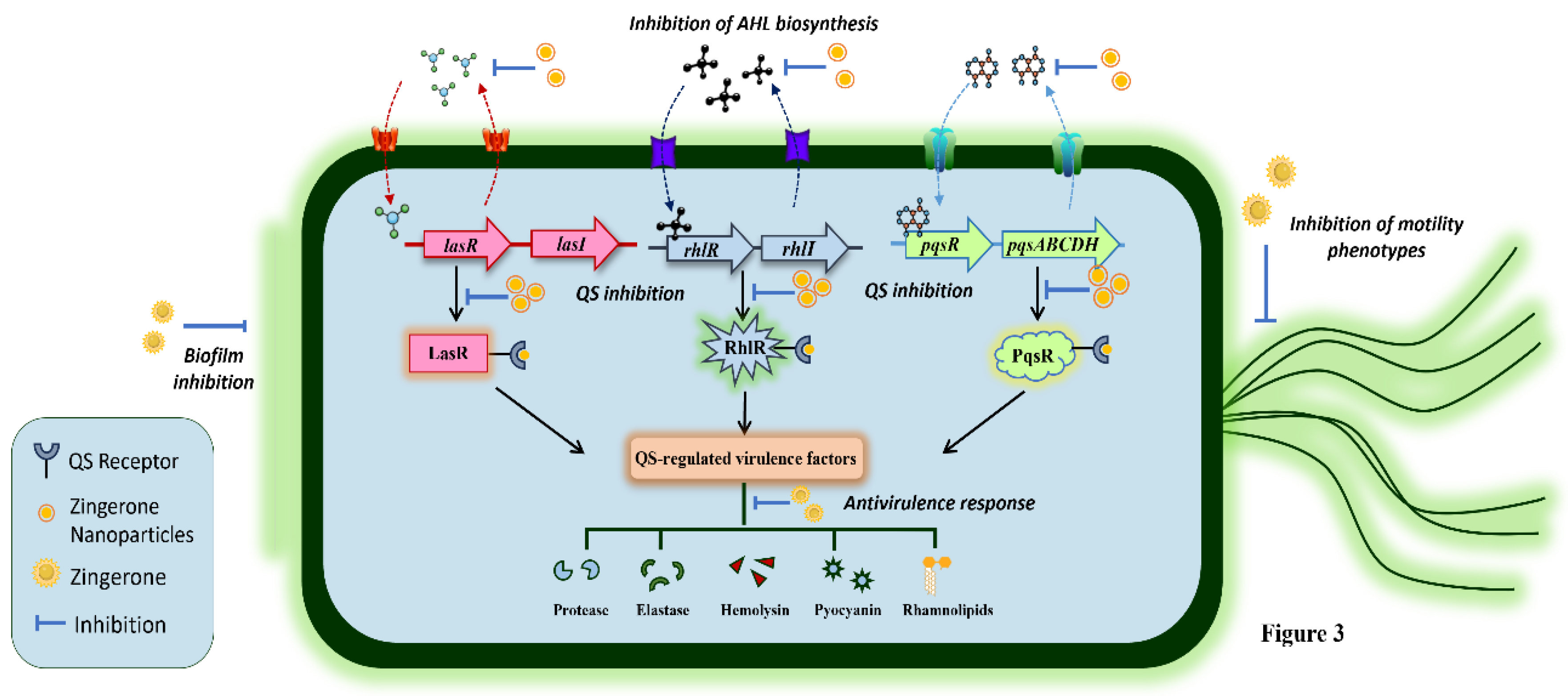

The antimicrobial property of ZiN has not been precisely reported, but it is known to augment the biological activity of existing antibiotics and antimicrobial drugs. However, its anti-quorum sensing (QS) and antivirulence potential has been thoroughly investigated, highlighting its ability to hinder the virulence pathways in bacterial pathogens without killing them. Research on ZiN’s potential as a QS inhibitor has primarily been focused on preventing bacterial biofilm-related infections. In this context, the first evidence was provided by Kumar and colleagues, who unveiled the antibiofilm activity of ZiN against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Kumar et al. 2013). In the study, the authors examined ZiN alone and in combination with ciprofloxacin, which notably impeded the motility phenotypes alongside inhibiting biofilm development/establishment in P. aeruginosa PAO1. Interestingly, ZiN alone was also effective in averting pseudomonal biofilm formation in vitro. In a follow-up study, the authors reported the anti-virulence and anti-QS properties of ZiN on the basis of decreased swimming (68%), swarming (55%), and twitching (67%) motility phenotypes in P. aeruginosa PAO1 as well as uropathogenic (clinical) pseudomonal strains (Kumar et al. 2015). Interestingly, the phenotypic expression of QS-regulated virulence factors, including rhamnolipids, pyocyanin, protease, elastase, and hemolysins (cell-free and cell-bound) were significantly inhibited, thereby rendering the pathogen avirulent. The findings were supported by molecular docking analysis that predicted high-affinity interactions between ZiN and QS receptors of P. aeruginosa, thereby possibly disrupting the ligand-receptor interactions between QS molecules (acyl-homoserine lactones: AHLs) and QS receptors. Furthermore, the authors investigated the effect of ZiN treatment on the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to various antibiotics and immune components: serum and phagocytes (Kumar et al. 2014). ZiN treatment drastically lowered the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of azithromycin, gentamicin, amikacin, carbenicillin, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, and cefotaxime by more than 4-, 2-, 3-, 6-, 2-, 3-, and 8-folds against P. aeruginosa PAO1, respectively, when compared to untreated controls. Additionally, ZiN exposure resulted in alteration of cell-surface hydrophobicity, which coincided with reduction in alginate, lipopolysaccharide production, and extracellular matrix. These structural modifications increased the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa towards murine serum and promoted macrophage-mediated phagocytic uptake and intercellular killing, thereby reducing the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and MIP-2) in murine macrophages.

Furthermore, ZiN-loaded polymeric chitosan nanoparticles (ZNPs) for enhanced drug delivery have also been prepared and examined for antivirulence potential in vitro (Sharma et al. 2020b). Sharma et al. prepared ZNPs using the ion-gelation method, which showed sustained drug release and silenced QS circuits in

P. aeruginosa by lowering AHL biosynthesis. Treatment with ZNPs was found to be more efficacious over ZiN (alone) in promoting antivirulence response by significantly lowering phenotypic production of pyocyanin, alginate, hemolysin, protease, and elastase in

P. aeruginosa PAO1. The genotypic expression of QS genes (

lasI,

lasR,

rhlI,

rhlR) was also notably downregulated in the presence of ZNPs, which further promoted the anti-motility and biofilm-eradication ability of ZNPs. The authors subsequently tested the therapeutic efficacy of ZNPs in a murine model of biofilm-associated acute pyelonephritis induced by

P. aeruginosa (Sharma et al. 2020a). Upon intravesicular administration of ZNPs (100 mg/kg body weight), bacterial burden in urinary bladder and kidneys was drastically reduced within 5 days and the renal tissues displayed mild neutrophil infiltration corresponding to significantly lowered levels of inflammatory markers like myeloperoxidase, malondialdehyde, and reactive nitrogen intermediates. ZNP-treated

P. aeruginosa also showed increased susceptibility to serum and murine macrophages, indicating phagocytic uptake and killing of bacterial cells ex vivo. The mechanisms by which ZiN extends anti-QS activity, thereby eliciting antivirulence response against

P. aeruginosa have been depicted in

Figure 3.

Additionally, ZiN’s anti-fouling activity is currently being studied against other pathogens responsible for causing biofilm-associated infections. One such study conducted by Kharga et al. assessed the potency of ZiN against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (S. Typhi) biofilms, alone and in combination with ciprofloxacin and kanamycin (Kharga et al. 2023). The study draws a positive correlation with previous reports, highlighting ZiN’s ability to retard bacterial motility, bacterial attachment/adhesion to surfaces, and alter biofilm architecture of S. Typhi by reducing exopolysaccharide secretion. Moreover, the antifouling potential of ciprofloxacin and kanamycin was notably augmented by the presence of ZiN (100 µg/mL). Similar effects of ZiN have also been reported against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (Larijanian et al. 2024). The pre-clinical study described a niosomal formulation of ZiN that was tested against pre-formed MRSA biofilms. Interestingly, encapsulated ZiN (250 µg/mL) was more efficacious over free-ZiN (1000 µg/mL) in eradicating pre-formed MRSA biofilms by 90%, 70%, and 55% on days 1, 3, and 5, respectively. Hence, ZiN proves to a potent phytochemical that can be aggressively explored as a promising antivirulence agent and an adjuvant for existing antimicrobial therapies.

4.2. Antioxidant Potential: Radical Scavenging Activity in Focus

ZiN is one of the most prominent phytochemicals that exhibits remarkable antioxidant properties and free-radical-scavenging activity. For the first time, Reddy and Lokesh demonstrated the antioxidant property of ZiN (150-600 µM), wherein the phytochemical prevented liver microsomal (rat) lipid peroxidation by 50-60% (Pulla Reddy and Lokesh, 1992). The authors thus indicated the health benefits of ZiN and proposed that its antioxidant effect may help in slowing down the progression of rheumatoid arthritis, neurological disorders, cancer and atherosclerosis. Besides, ZiN has been studied for its potential application as an antioxidant food additive. Aeschbach et al. demonstrated the ZiN could weakly inhibit peroxidation of ox-brain phospholipid liposomes in presence of Fe3+ and ascorbate (Aeschbach et al. 1994). Contrarily, ZiN was found to effectively scavenge peroxyl radicals (CCl3O2-) in vitro. Moreover, Kabuto et al. also revealed that ZiN could scavenge O2- and OH- radicals and inhibit lipid peroxidation in mouse brain homogenate very weakly (Kabuto et al. 2005) under simulated conditions. Nevertheless, in view of its antioxidative potential, the authors implicated the use of ZiN for treating Parkinson's disease, a condition that is known to be associated with increased oxidative stress resulting from decreased activity of free-radical scavenging enzymes like catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase. The authors injected 6-hydroxydopamine in mice to reduce the levels of dopamine and subsequently administered ZiN intraperitoneally (65 nmol/kg body weight). ZiN treatment significantly lowered striatal dopamine levels and increased the serum O2- scavenging activity in mice. Additionally, ZiN administration did not affect catalase or glutathione peroxidase activity in striatum or serum, but promoted superoxide dismutase activity, thereby extending neuroprotective effects (Kabuto et al. 2005).

ZiN has also been shown to counter the peroxynitrite-induced oxidative damage in rat prostatic endothelial cells (YPEN-1). Under laboratory conditions, ZiN was able to effectively scavenge ONOO

- radicals (peroxynitrite), showing similar activity to a strong peroxynitrite scavenger, penicillamine (Shin et al. 2005). Further, ZiN prevented ONOO

--mediated nitration of tyrosine and bovine serum albumin through electron donation in a dose-dependent manner. In YPEN-1 cells, treatment with ZiN (5-60 µM) notably lowered the generation of intracellular reactive species and tert-butylhydroperoxide (oxidizing agent)-induced production of ONOO

-. Another study evaluated ZiN’s ability to protect against radiation-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage in Chinese hamster lung fibroblast cells (Rao and Rao, 2010). ZiN could readily scavenge different types of free radicals, including NO, O

2-, and OH

-. The total antioxidant activity of ZiN was measured in terms of IC₅₀ values (inhibitory concentration required to scavenge 50% of free radicals), which was found to be 43.09 µg/mL. Interestingly, ZiN (25 µg/mL) did not show any cytotoxicity but rescued and protected V79 cells from infrared- and gamma radiation-induced damage by significantly reducing DNA strand breaks (fragmentation). Consequently, ZiN reduced both apoptosis and necrosis in gamma-irradiated cells and prevented the intracellular oxidation of a fluorescent dye (DCHF-DA), which coincided with increased levels of glutathione, gluthione-

S-transferase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase (Rao and Rao, 2010). In a similar study, the authors elucidated the anticlastogenic and radioprotective effect of ZiN in Swiss albino mice (Rao et al. 2009). Oral administration of ZiN (10-100 mg/kg body weight: once for 5 days) did not show any signs of toxicity, but increased survival time in gamma-irradiated mice (1.2 folds). ZiN pre-treatment also boosted glutathione, gluthione-

S-transferase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase levels and conversely lowered lipid peroxidation in Swiss albino mice undergoing gamma radiation. Overall, this highlights the role of ZiN in mitigating radiation-induced cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, and mortality in mice. Subsequent studies have also shed light on the antioxidative and protective role of ZiN in ischemia-reperfusion-induced oxidative stress in rats that display neural degeneration resulting from the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Vaibhav et al. 2013). Oral administration of ZiN (50-100 mg/kg body weight twice daily) drastically reduced cerebral infarct volume (21-30%) and mitochondrial damage (23-36%) with improved behavioural responses: grip strength and motor coordination. Ischemic rats receiving ZiN showed reduced neural injury (degeneration) as compared to untreated groups along with suppressed expression of pro-apoptotic markers (caspase-3/9, Bac protein, and

Apaf-1) and increased expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, preventing tissue damage and cell death. Furthermore, ZiN-treated rats exhibited lowered lipid peroxidation with restored glutathione levels and restored superoxide dismutase activity, potentiating antioxidative responses (Vaibhav et al. 2013). ZiN has also been evaluated as a potent antioxidant capable of alleviating the toxicities and side effects associated with cisplatin, a widely used chemotherapeutic agent (Alibakhshi et al. 2018). Oral administration of ZiN (10-50 mg/kg body weight) significantly lowered malondialdehyde levels (lipid peroxidation marker) and maintained catalase activity and glutathione peroxidase levels in renal tissues of mice receiving cisplatin intraperitoneally (7.5 mg/kg body weight). Additionally, ZiN dosing also reduced the levels of pro-inflammatory markers (TNF-α) and improved tissue histopathology by abolishing leukocyte infiltration, vacuolation, loss of brush border, and erythrocyte congestion (Alibakhshi et al. 2018). In the same direction, a recent study by Elshopakey et al. suggested the use of ZiN as a dietary supplement to protect against renal toxicity from adriamycin, a chemotherapeutic agent (Elshopakey et al. 2021). The molecular mechanisms encompassing the antioxidant potential of ZiN have been depicted in

Figure 4. Overall, the existing evidences and advancing research on ZiN validates its intrinsic antioxidant capabilities, which can be exploited/repurposed for its application in mainstream medicine.

4.3. Anti-Inflammatory Property of ZiN: Subsiding the Inflammatory Responses

In addition to being an anti-oxidant, ZiN also harbors anti-inflammatory properties that enhance its broad pharmacological potential and use case in drug repurposing. The anti-inflammatory activity of ZiN is potentiated by the inhibition of inflammatory markers through its free radical-scavenging activity and intrinsic antioxidant potential. It further interferes with the cell signalling pathways involved in inflammation and modulates the NF-κB- (Nuclear Factor-kappa B), MAPK- (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase), and COX-2- (Cyclooxygenase-2) associated pathways (Jesudoss et al. 2017). In an attempt to scrutinize the anti-inflammatory potential of various active-spice components, Woo et al. elucidated that ZiN (10-100 µM) could suppress the activation of Raw 264.7 macrophage cell line by inhibiting chemotaxis up to 50%. Consequently, ZiN at 200 µM inhibited pro-inflammatory markers, i.e., nitric oxide and TNF-α production from Raw 264.7 cells by ~ 68% and ~ 50%, respectively. Moreover, ZiN (100 µM) was able to lower the production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) by ~ 33% in 3T3-L1 adipocytes in vitro. Subsequent evidence was provided by Kim and colleagues in an investigation that examined the short-term efficacy of ZiN supplementation in suppressing age-related inflammatory responses via NF-κB modulation (Kim et al. 2010). The findings reaffirmed the radical scavenging of ZiN and further established that ZiN treatment (1-20 µM) of YPEN-1 cells significantly suppressed NF-κB luciferase activity in a concentration-dependent manner in vitro. The results were validated in aged rats (24 months old) wherein ZiN supplementation in feed (8 mg/kg/day for 10 days) lowered the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and suppressed the age-associated up-regulation and phosphorylation of NF-κB, which in turn reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory markers (COX-2 and iNOS) in aged rat kidneys and endothelial cells. Additionally, it was revealed that ZiN interferes with NF-κB activation by abrogating the phosphorylation of NF-κB-inducing kinase and IκB kinase, and even through suppression of MAPKs pathway genes, including ERK, p38, and JNK (Kim et al. 2010).These pre-clinical studies are also being tested in disease models, wherein ZiN treatment has been shown to improve therapeutic outcome and potentiate anti-inflammatory responses in vivo. One such study by Hsiang et al. demonstrated the ability of ZiN (0.1-100 mg/kg body weight: intrarectal delivery) in ameliorating trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colitis in mice through downregulation of cytokine-related genes/pathways (microarray testing), which were notably upregulated by trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (Hsiang et al. 2013). The results were supported by histopathological analysis which displayed reduction in colonic injury, inflammation, and ulceration in ZiN-receiving mice. Moreover, immunohistochemical staining and ex vivo imaging confirmed the suppression of NF-κB activity and the IL-1β protein production in the colon tissues of ZiN-treated mice, thereby affirming the anti-inflammatory potential of ZiN.

The protective effect of ZiN has also been investigated against lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation in a murine model of

P. aeruginosa-associated peritonitis (Grivennikov et al. 2014). Intramuscular administration of ZiN (100 mg/kg body weight: single dose) in conjunction with cefotaxime-amikacin combination remarkably lowered endotoxin-mediated inflammatory responses within the hepatic tissue and improved liver histology. Several biochemical markers, including malondialdehyde, reactive nitrogen species, and myeloperoxidase production, and inflammatory markers: TNF-α, MIP-2, and interleukin-6 (IL-6), were all drastically reduced following ZiN treatment. Tissue damage markers,

viz. alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase were also lowered by 1.86-, 1.75-, 1.55-folds in ZiN-antibiotic-treated mice, respectively. The authors also highlighted the transcriptional downregulation of key pro-inflammatory markers, including TNF-α, TLR4, and iNOS, when compared to the untreated group. On similar lines, other investigations have also established the anti-inflammatory and protective effect of ZiN against alcohol-induced (Mani et al. 2016) and carbon tetrachloride- and dimethylnitrosamine-induced hepatotoxicity (Cheong et al. 2015) in Wistar and Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, respectively. Interestingly, ZiN has also been assessed for its anti-inflammatory and protective effects against coronary thrombosis in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction (Hemalatha and Stanely Mainzen Prince, 2016). Orally-administered ZiN (6 mg/kg body weight: daily for 2 weeks) markedly lowered heart lysosomal lipid peroxidation products along with high-sensitive C-reactive protein, serum cardiac troponin-I, and lysosomal hydrolases in Wistar rats. These biochemical changes coincided with downregulation of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β genes, which are responsible for promoting inflammation in the heart tissue. Moreover, histopathological findings were in-sync and indicated the absence of infiltrated inflammatory cells in myocardial-infarcted rats pretreated with ZiN (Hemalatha and Stanely Mainzen Prince, 2016). The mechanistic insights behind the anti-inflammatory potential of ZiN have been illustrated in

Figure 4. Overall, these pre-clinical findings strongly point towards the anti-inflammatory action of ZiN and establish its protective efficacy against a myriad of diseases.

4.4. Anticancer Potential: Far-Reaching Effects of ZiN

In the recent years, anticancer therapy has shifted its focus from chemically-synthesized drugs (artificial) to the use of naturally-occurring phytoconstituents. The application of phytochemicals is being seamlessly explored against various cancers to address the major limitation of drug resistance and adverse side effects of conventional anticancer drugs. In this direction, ZiN has been widely scrutinized for its antitumorigenic potential in several investigations. The first insights were provided by Daghri et al. who identified ZiN’s presence (16.5%) in fenugreek extract using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), proving its ability to induce dose-dependent autophagy-associated death in Jurkat cells (immortalized T-lymphocyte cell line) in vitro through transcriptional upregulation of LC3 (autophagy marker) (Al-Daghri et al. 2012). Subsequent investigation by Vinothkumar et al. analyzed the protective anticancer effects of oral ZiN supplementation (10-40 mg/kg body weight) in albino Wistar rats with 1,2-dimethylhydrazine (DMH)-induced colon cancer (Vinothkumar et al. 2014). ZiN administration (40 mg/kg body weight) lowered DMH-induced colonic tumors (polyps) by 41% and suppressed the formation of aberrant crypt foci by over 3-folds, when compared to untreated (control) rats. Also, ZiN treatment reduced lipid peroxidation in liver homogenates and promoted antioxidant potential by elevating the levels of superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione, and vitamin C/E. Thus, it was speculated that ZiN protects against chemically-induced cancers by potentiating antioxidant capabilities in vivo. Further, Su et al. also established the antitumor effects of ZiN in HCT116 colorectal cell line through modulation of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage and promoting apoptosis (Su et al. 2019). The study demonstrated the dose-dependent cytotoxic effect of ZiN (10 µM) against HCT116 cells by enhancing intracellular ROS accumulation, lowering mitochondrial membrane potential, and inflicting significant DNA damage. Consequently, the study further provided molecular insights, confirming the increased expression of Bax, caspase-3, and caspase-9, along with downregulation of Bcl-2, thereby stimulating apoptotic signalling and initiating cell death in ZiN-treated HCT116 cells in vitro (Su et al. 2019). On similar lines, Woom et al. demonstrated the anti-angiogenic activity of ZiN and elucidated its underlying mechanisms in a murine tumor model (Bae et al. 2016). BALB/c mice were subcutaneously injected with a murine-derived renal adenocarcinoma cell line (Renca cells) and ZiN (10 mg/kg body weight) was administered after 1 week. Interestingly, when compared to untreated mice that developed big tumors, treatment group showed reduction in tumor growth following ZiN administration, without showing any signs of hepatocytotoxicity. With significantly lowered hemoglobin content and immunohistological analysis revealing reduced expression of CD31 (endothelial biomarker) in tumor capillaries, angiogenesis was notably suppressed in ZiN-treated mice. The findings were also supported by in vitro that indicated the anti-angiogenic potential of ZiN during tumor progression through suppression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (matrix metalloproteinases) via the JNK signalling pathway (Bae et al. 2016).

ZiN and its derivatives have also been evaluated for its antiteratogenic potential in vitro. Kim and colleagues synthesized a novel ZiN derivative (ZD 2-1) and identified its synergistic anticancer potential with ZiN in overriding epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Kim et al. 2017). Combined treatment increased E-cadherin expression (tumor suppressor) and transcriptionally downregulated Snail and N-cadherin (mesenchymal markers) during transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF β-1)-induced EMT in SNU182 cells. Additionally, combinational treatment with ZiN and ZD 2-1 inhibited cell migration and invasion abilities, suppressed Smad2/3 (TGF β-1 cofactor) and MMP-2/9 activity, thereby inhibiting nuclear translocation of NF-κB. The experimental findings thus provided the first insights into the anticancer potential of ZiN and its derivative through inhibition of cell migration, invasion, and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. In a pioneering effort, Choi et al. investigated ZiN's potential as an anti-mitotic agent in tumor models using both in vitro and in vivo methods (Choi et al. 2018). The study demonstrated that ZiN (0.5-2 mM) effectively suppressed the growth of different neuroblastoma cell lines [SH-SY5Y, BE(2)C, and BE(2)-M17] and highlighted its potential as a therapeutic drug for human cancers. In vitro experiments revealed that ZiN delayed the transition from prometaphase to metaphase, resulting in cell-cycle arrest of BE(2)-M17 cells at mitosis. Further, ZiN treatment (2 mM) downregulated the expression of cyclin D1, a key regulator and potential target for cancer therapies, in BE (2)-M17 cells. This downregulation induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells through by enhancing the cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP-1 in BE(2)-M17 cells, without extending any cytotoxicity towards normal cells (Choi et al. 2018). Recently, ZiN has been shown to promote immune responses in a murine model of breast cancer induced using 4T1 cells (Kazemi et al. 2021). The authors examined parameters such as Th

1 and T

reg cells percentages, as well as expression of IFN-γ and TGF-β in blood mononuclear cells along with antibody production. Interestingly, intraperitoneal ZiN administration (100 mg/kg body weight) led to a drastic reduction in tumor size on day 18 (~ 60%), which coincided with a notable increase in the relative percentage of splenic Th

1 cells and decrease in T

reg cells, correlating to its anti-tumorigenic activity. This was further supported by enhanced IFN-γ expression and reduced TGF-β expression. Overall, the investigation highlights ZiN’s potential as an immunotherapeutic agent and lays the groundwork for more in-depth studies (Kazemi et al. 2021). Additionally, to overcome the limitation of oral bioavailability, self-microemulsifying drug delivery system containing ZiN (Z-SMEDDS) has been formulated for cancer treatment (Cao et al. 2021). Z-SMEDDS demonstrated steady/stable physicochemical characteristics with a particle size of 17.29 ± 0.07 nm, polydispersity index of 0.17 ± 0.01, and zeta potential of -38.25 ± 0.29 mV. In vitro studies revealed that ZiN released from SMEDDS was higher in comparison to the free ZiN in 4 different media, thereby improving its solubility and release rate. Further, the pharmacokinetic parameters including oral bioavailability, mean residence time, and elimination half-life of ZiN released from SMEDDS in SD rats was improved by 7.63-, 12.5-, and 13.1-times, respectively, as compared to free ZiN. Interestingly, cytotoxicity assays using HepG2 cells demonstrated that the IC

50 of Z-SMEDDS was ~ 1.63-folds lower than that of free ZiN, pointing towards the enhanced anticancer effect and potency of Z-SMEDDS as a drug delivery system. Based on the existing literature,

Figure 5 depicts the molecular mechanisms targeted by ZiN for extending its antitumorigenic potential against human cancers. In summary, these studies exemplify the far-reaching effects and therapeutic potential of ZiN for its repurposing as an anticancer drug.

4.5. Other Biological Properties of ZiN: Extending Beyond Boundaries

In addition to the well-elucidated pharmacological properties, several other studies have shown that ZiN provides health benefits, ranging from anti-diabetic, anti-hyperlipidaemic, neuromodulatory, and even radioprotective effects. For instance, researchers investigated the antidiabetic effects of ZiN in streptozocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats (Cs and Vincent, 2016). Oral administration with ZiN (10 mg/kg body weight) was shown to significantly reduce blood glucose and lipid profiles (serum, liver, & kidney), while preserving normal pancreatic histology. ZiN has also been shown to alleviate phenylephrine-induced vasoconstriction in the aorta of diabetic rats and significantly improve relaxatory response to acetylcholine likely due to the stimulation of nitric oxide and guanylate cyclase (Ghareib et al. 2016). Additionally, orally-administered ZiN (50-100 mg/kg body weight) was shown to ameliorate alloxan-induced diabetes and related ailments in Wistar rats by lowering oxidative stress through a marked increase in catalase, reduced glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, & superoxide dismutase activity, alongside suppressing the transcription of NF-κB, pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL1, IL-2, IL-6, & TNF-α). Moreover, ZiN was able to restore insulin levels to normal in diabetic rats, establishing its potential as a therapeutic agent for managing diabetes (Ahmad et al. 2018). Similarly, studies have reported the antihyperlipidemic effect of ZiN through a direct reduction in the activity of hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase and regulating the levels of cholesterol and triglycerides, low-density lipoproteins, thereby improving lipid metabolism and managing cardiovascular conditions (Hemalatha and Stanely Mainzen Prince, 2015) and even reverse ethanol induced-liver damage in rats (Mani et al. 2017).

The neuromodulatory effect of ZiN has also been investigated in rat trigeminal ganglion cells, revealing its ability to activate transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptors and stimulate sensory pathways involved in sensing pain and inflammation (Liu and Simon, 1996). In addition, repeated lingual/corneal exposure of ZiN was shown to overcome tachyphylaxis, but rather elicit a gustatory response for a shorter duration, thereby suggesting a safer profile for its therapeutic use (Liu et al. 2000). Lastly, ZiN’s radioprotective effects have been demonstrated in various animal models. An in vivo study demonstrated how ZiN pre-treatment mitigates radiation-induced oxidative stress through enhanced free-radical-scavenging activity and antioxidant levels through increased levels of catalase, superoxide dismutase, reduced glutathione, and glutathione-S-transferase (Rao et al. 2009). A follow-up study further supported this hypothesis and elucidated the anti-apoptotic and anti-genotoxic potential of ZiN (10 μg/mL) against radiation-induced damage in human lymphocytes, validating its antioxidant and cytogenetic-protective properties (Rao et al. 2011). ZiN also demonstrated its protective effect against UVB-induced damage in keratinocyte stem cells through its potent anti-inflammatory mechanism (Lee et al. 2018). Interestingly, a zingerone derivative, thiazolidine hydrochloride (TZC01), was synthesized through structural modification and demonstrated radioprotective effects in preventing ionizing radiation-induced intestinal injury in C57BL/6J mice, suggesting the potential for developing more effective radioprotective agents (Li et al. 2019b). Another derivative of ZiN, acetyl ZiN, has demonstrated protective effects against UVA-induced DNA damage and -ROS production in keratinocytes in vitro, thereby extending its application for improving the photoprotective effects of conventional sunscreens and skin care products (Chaudhuri et al. 2019). These diverse pharmacological activities highlight ZiN’s potential as a multifaceted therapeutic agent. Besides the previously-discussed pharmacological properties, various other biological prospects of ZiN have been well documented in the scientific literature. These involve several additional attributes that further substantiate its therapeutic value. A brief overview of these properties is documented in

Table 3. Furthermore,

Table 4 outlines various ZiN formulations that have been recently developed and assessed for a range of biomedical applications. Additionally, researchers have generated intellectual property (patents) by showcasing the application/effectiveness of ZiN and its formulations for the treatment of human diseases/disorders. These have been summarized in

Table 5.

5. Clinical Trials on ZiN: The Ongoing Journey from Lab to Market

Although a plethora of preclinical studies involving comprehensive in vitro and in vivo experimentations have established the multifarious nature of ZiN, field trails or clinical testing dictates the ultimate fate for the widescale application of this phytochemical. Till date, the major bulk of studies pertaining to ZiN comprises only preclinical studies, while no substantial findings have been obtained from ongoing/completed clinical trials that evaluate the overall effectiveness of the phytochemical. In this direction, acetyl ZiN, has undergone two completed clinical trials to date, with one additional trial currently ongoing. Among the trials, one describes a randomised, double-blinded trial (NCT03530787) conducted to assess the efficacy of acetyl ZiN in preventing photoaging. The testing was conducted on 31 healthy individuals who applied 1% acetyl ZiN cream-based formulation, which was recommended for use, twice daily for 8 weeks. During the course of trial, various parameters were assessed to evaluate the signs of photoaging in terms of redness, wrinkles and dyspigmentation, using a specialised software. Subjects receiving acetyl ZiN for up to 8 weeks showed significant improvements, with reduction in wrinkle severity, pigmentation, and redness by 25.7%, 25.6%, and 20.7%, respectively. Additionally, no adverse effects like itching, stinging, and burning were reported among the participants, indicating its safety and tolerability (Dhaliwal et al. 2020). In a subsequent study, acetyl ZiN was further evaluated in combination with tetrahexyldecyl ascorbate (THDA) to examine their combined effects on skin photoaging. The study was carried out on 44 healthy males and females aged 30-65 years, all with wrinkles and facial fine lines, in a randomized, double-blind, comparative clinical trial (NCT05779280). The participants received the combined formulation (THDA 5%, acetyl ZiN 1%) or THDA (5%) alone, for up to 8 weeks. The results revealed a significant reduction in wrinkle severity (3.72%), skin redness (14.25%), and pigmentation (4.1%) with the combinational formulation, as compared to THDA alone. It was also observed that acetyl ZiN helped stabilizing THDA, thereby improving its bioavailability and overall effectiveness (Afzal et al. 2024). Another clinical trial is currently underway for evaluating the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of ginger extract, under the brand name Carelwon®. It is a botanical drug containing ZiN (12.5 mg/mL) as the active component, offering a novel approach to manage rheumatoid arthritis. The trial describes a double-blind, randomized, comparative Phase 1 study (ACTRN12624000125527) involving oral administration of Carelwon® in healthy volunteers. A total of 40 participants, aged 18-5 years, are being actively recruited. The primary assessment will focus on the incidence and severity of adverse events during the study period. Nevertheless, these ongoing studies highlight the growing interest in ZiN as a potential therapeutic agent. However, further investigations are needed to establish its therapeutic efficacy and safety for its widescale application in mainstream medicine and other avenues (ANZCTR, 2024).

6. Conclusion and Future Prospects

ZiN harbors a diverse range of biological properties, making it a compelling candidate for biomedical applications. Its pharmacological potential spans across multiple domains, including antivirulence, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects. These attributes position ZiN as a potent biomolecule for ongoing research and medical advancements. Owing to its synergistic interactions with existing antibiotics, ZiN holds promise as an effective adjuvant toward antimicrobial therapy. In view of rising antibiotic resistance, antivirulence strategies are gaining attention as the next-generation therapies for combating pathogenic bacteria. Since ZiN interferes with QS mechanisms that regulate bacterial virulence, it could play a plausible role as an alternative to conventional antibiotics. Furthermore, chemical modifications of ZiN may lead to the development of novel drug conjugates/hybrids with enhanced antivirulence properties. Enhancing the bioavailability of ZiN through preparation of pharmaceutical formulations, such as liposomes, niosomes, and nanoparticles, could remarkably improve its therapeutic efficacy. The antioxidant properties also make ZiN an excellent candidate as a nutraceutical or dietary supplement, for improving human health by preventing oxidative stress/damage-related disorders. Moreover, its anti-inflammatory properties offer an alternative to traditional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, thereby reducing the risk of associated side/adverse effects.

Among its most extensively studied benefits of ZiN is its profuse anticancer potential. Research suggests that it could be integrated into chemotherapy protocols alongside conventional anticancer agents to enhance treatment outcomes against different types of malignancies. Nevertheless, further validation of its pharmacological properties through largescale animal studies and clinical trials is an important prerequisite to successfully translate the bench-based findings into real-world medical applications. One of the primary obstacles to the widespread adoption of ZiN in mainstream medicine is the deficiency of clinical data. So far, majority of field trials have largely focused on the application of a ZiN derivative, acetyl ZiN, that too only as a photoprotective agent. To fully explore its therapeutic capabilities, more clinical research is warranted to bridge existing gaps in the knowledge about ZiN’s pharmacological benefits. Establishing collaboration between academic researchers and the pharmaceutical industry is quintessential to overcome this pitfall. Overall, the current scientific evidences validate the multifaceted nature and lay fertile grounds for extensively undertaking research on ZiN. In conclusion, this wonder molecule can play a major role in shaping the evolving landscape of phytochemical-based therapies, providing a new paradigm for innovative disease treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

JC and LK would like to acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Govt. of India, New Delhi, for providing Senior Research Fellowship (SRF).

Author Contributions

SR: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JC: Conceptualization, Supervision, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LK: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. BS: Formal Analysis. KH: Supervision, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

All the datasets generated and analyzed during the current study have all been cited in this manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Abbreviations

AHLs: acyl-homoserine lactones, COX-2: cyclooxygenase-2, DMH: 1,2-dimethylhydrazine, EMT: epithelial–mesenchymal transition, IC₅₀: inhibitory concentration (50% inhibition), IL: interleukin-6, LPS: lipopolysaccharide, MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase, MCP-1: monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration, MMP: matrix metalloproteinases, MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, NF-κB: nuclear factor-kappa B, ONOO-: peroxynitrite radical, QS: quorum sensing, ROS: reactive oxygen species, SD rats: Sprague-Dawley rats, TGF β-1: transforming growth factor beta-1, THDA: tetrahexyldecyl ascorbate, ZNPs: ZiN nanoparticles (ZNPs), Z-SMEDDS: self-microemulsifying drug delivery system containing ZiN, ZiN: Zingerone.

References

- Aeschbach, R.; Löliger, J.; Scott, B.C.; Murcia, A.; Butler, J.; Halliwell, B.; Aruoma, O.I. Antioxidant actions of thymol, carvacrol, 6-gingerol, zingerone and hydroxytyrosol. Food Chem Toxicol 1994, 32, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, N.; Nguyen, N.; Min, M.; Egli, C.; Afzal, S.; Chaudhuri, R.K.; Burney, W.A.; Sivamani, R.K. Prospective randomized double-blind comparative study of topical acetyl zingerone with tetrahexyldecyl ascorbate versus tetrahexyldecyl ascorbate alone on facial photoaging. J Cosmet Dermatol 2024, 23, 2467–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, B.; Rehman, M.U.; Amin, I.; Arif, A.; Rasool, S.; Bhat, S.A.; Afzal, I.; Hussain, I.; Bilal, S.; Mir, M.u.R.; Efferth, T. A Review on Pharmacological Properties of Zingerone (4-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-butanone). Sci World J 2015, 2015, 816364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, B.; Rehman, M.U.; Amin, I.; Mir, M.u.R.; Ahmad, S.B.; Farooq, A.; Muzamil, S.; Hussain, I.; Masoodi, M.; Fatima, B. Zingerone (4-(4-hydroxy-3-methylphenyl) butan-2-one) protects against alloxan-induced diabetes via alleviation of oxidative stress and inflammation: Probable role of NF-kB activation. Saudi Pharm J 2018, 26, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daghri, N.M.; Alokail, M.S.; Alkharfy, K.M.; Mohammed, A.K.; Abd-Alrahman, S.H.; Yakout, S.M.; Amer, O.E.; Krishnaswamy, S. Fenugreek extract as an inducer of cellular death via autophagy in human T lymphoma Jurkat cells. BMC Complement Altern Med 2012, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.F.; Hijri, S.I.; Alshahrani, S.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Jali, A.M.; Ahmed, R.A.; Adawi, M.M.; Algassmi, S.M.; Shaheen, E.S.; Moni, S.S.; Anwer, T. Zingerone Attenuates Carfilzomib-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Rats through Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Cytokine Network. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.M.; Alaghaz, A.-N.M.A.; Al Hujran, T.A.; Eldin, Z.E.; Elbeltagi, S. A novel zingerone-loaded zinc MOF coated by niosome nanocomposites to enhance antimicrobial properties and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Mater Today Commun 2024, 41, 110245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibakhshi, T.; Khodayar, M.J.; Khorsandi, L.; Rashno, M.; Zeidooni, L. Protective effects of zingerone on oxidative stress and inflammation in cisplatin-induced rat nephrotoxicity. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 105, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANZCTR (2024) A phase 1 study to evaluate the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of a ginger tincture extract in healthy volunteers. Available online: https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=387127 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Bae, W.-Y.; Choi, J.-S.; Kim, J.-E.; Park, C.; Jeong, J.-W. Zingerone suppresses angiogenesisviainhibition of matrix metalloproteinases during tumor development. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 47232–47241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, Q.-L.; Adu-Frimpong, M.; Wei, C.-M.; Weng, W.; Bao, R.; Wang, Y.-P.; Yu, J.-N.; Xu, X.M. Improvement of Oral Bioavailability and Anti-Tumor Effect of Zingerone Self-Microemulsion Drug Delivery System. J Pharm Sci 2021, 110, 2718–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caval, M.; Dettori, M.A.; Carta, P.; Dallocchio, R.; Dessì, A.; Marceddu, S.; Serra, P.A.; Fabbri, D.; Rocchitta, G. Sustainable Electropolymerization of Zingerone and Its C2 Symmetric Dimer for Amperometric Biosensor Films. Molecules 2023, 28, 6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, R.K.; Meyer, T.; Premi, S.; Brash, D. Acetyl zingerone: An efficacious multifunctional ingredient for continued protection against ongoing DNA damage in melanocytes after sun exposure ends. Int J Cosmet Sci 2019, 42, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, K.O.; Shin, D.-S.; Bak, J.; Lee, C.; Kim, K.W.; Je, N.K.; Chung, H.Y.; Yoon, S.; Moon, J.-O. Hepatoprotective effects of zingerone on carbon tetrachloride- and dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver injuries in rats. Arch Pharm Res 2015, 39, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.-S.; Ryu, J.; Bae, W.-Y.; Park, A.; Nam, S.; Kim, J.-E.; Jeong, J.-W. Zingerone Suppresses Tumor Development through Decreasing Cyclin D1 Expression and Inducing Mitotic Arrest. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chougule, S.; Basrani, S.; Gavandi, T.; Patil, S.; Yankanchi, S.; Jadhav, A.; Karuppayil, S.M. Zingerone effect against Candida albicans growth and biofilm production. J Med Mycol 2025, 35, 101527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cs, P.; Vincent, S. Antidiabetic, hypolipidemic, and histopathological analysis of zingerone in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2016, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darekar, S.U.; Nagrale, D.S.N.; Babar, D.V.B.; Pondkule, A. Review on ginger: Chemical constituents & biological effects. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2023, 12, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, S.; Rybak, I.; Pourang, A.; Burney, W.; Haas, K.; Sandhu, S.; Crawford, R.; KSivamani, R. Randomized double-blind vehicle controlled study of the effects of topical acetyl zingerone on photoaging. J Cosmet Dermatol 2020, 20, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Adawy, M.A.A.E.A.; Abd El-Latif, A.; Farrag, F.; Shukry, M.; Braiji, S.H.B.H.; Hanafy, A. Effect of Zingerone and/or Vitamin C on the Immune System of Albino Rats, Hematological, Biochemical, Gene Expression Biomarkers and Histological Study. Egypt J Vet Sci 2025, 56, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshopakey, G.E.; Almeer, R.; Alfaraj, S.; Albasher, G.; Abdelgawad, M.E.; Abdel Moneim, A.E.; Essawy, E.A. Zingerone mitigates inflammation, apoptosis and oxidative injuries associated with renal impairment in adriamycin-intoxicated mice. Toxin Rev 2021, 41, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmi, A.; Hassanen, N.; Abdur-Rahman, M.; Shams-Eldin, E. Phytochemicals, antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale) on diethylnitrosamine toxicity in rats. Biomarkers 2019, 24, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza-Cadena, C.; Ortega-Rivera, D.M.; Machorro-García, G.; Gonzalez-Zermeño, E.M.; Homma-Dueñas, D.; Plata-Gryl, M.; Castro-Muñoz, R. A comprehensive review on Ginger (Zingiber officinale) as a potential source of nutraceuticals for food formulations: Towards the polishing of gingerol and other present biomolecules. Food Chem 2023, 413, 135629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafoor, K.; Al Juhaimi, F.; Özcan, M.M.; Uslu, N.; Babiker, E.E.; Mohamed Ahmed, I.A. Total phenolics, total carotenoids, individual phenolics and antioxidant activity of ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizome as affected by drying methods. Lwt 2020, 126, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareib, S.A.; El-Bassossy, H.M.; Elberry, A.A.; Azhar, A.; Watson, M.L.; Banjar, Z.M.; Alahdal, A.M. Protective effect of zingerone on increased vascular contractility in diabetic rat aorta. Eur J Pharmacol 2016, 780, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivennikov, S.; Kumar, L.; Chhibber, S.; Harjai, K. Zingerone Suppresses Liver Inflammation Induced by Antibiotic Mediated Endotoxemia through Down Regulating Hepatic mRNA Expression of Inflammatory Markers in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Peritonitis Mouse Model. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.-K.; Morimoto, C.; Zheng, Y.-N.; Li, W.; Asami, E.; Okuda, H.; Saito, M. Effects of Zingerone on Fat Storage in Ovariectomized Rats. Yakugaku Zasshi 2008, 128, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, K.L.; Stanely Mainzen Prince, P. Antihyperlipidaemic, Antihypertrophic, and Reducing Effects of Zingerone on Experimentally Induced Myocardial Infarcted Rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2015, 29, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, K.L.; Stanely Mainzen Prince, P. Anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic effects of zingerone in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Eur J Pharmacol 2016, 791, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, K.T.; Park, K.W.; Won, J.; Lee, B.; Jang, J.-H.; Ahn, J.-O.; Hwang, B.Y.; Hong, Y.-S. Construction of an Artificial Biosynthetic Pathway for Zingerone Production in Escherichia coli Using Benzalacetone Synthase from Piper methysticum. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 14620–14629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, C.-Y.; Lo, H.-Y.; Huang, H.-C.; Li, C.-C.; Wu, S.-L.; Ho, T.-Y. Ginger extract and zingerone ameliorated trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colitis in mice via modulation of nuclear factor-κB activity and interleukin-1β signalling pathway. Food Chem 2013, 136, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yao, X.; Cao, B.; Zhang, N.; Soladoye, O.P.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y. Encapsulation of zingerone by self-assembling peptides derived from fish viscera: Characterization, interaction and effects on colon epithelial cells. Food Chem X 2024, 22, 101506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwami, M.; Shiina, T.; Hirayama, H.; Shima, T.; Takewaki, T.; Shimizu, Y. Inhibitory effects of zingerone, a pungent component of Zingiber officinale Roscoe, on colonic motility in rats. J Nat Med 2010, 65, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesudoss VAS, Victor Antony Santiago S, Venkatachalam K, Subramanian P (2017) Zingerone (Ginger Extract): antioxidant potential for efficacy in gastrointestinal and liver disease. Gastrointest Tissue pp. 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.; Park, C.-S.; Park, Y.S.; Jin, Y.-H. Ginger and Its Pungent Constituents Non-Competitively Inhibit Serotonin Currents on Visceral Afferent Neurons. The Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 2014, 18, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindal, S.; Ghosal, K.; Khamaisi, B.; Kana'an, N.; Nassar-Marjiya, E.; Farah, S. Facile Green Synthesis of Zingerone Based Tissue-Like Biodegradable Polyester with Shape-Memory Features for Regenerative Medicine. Adv Funct Mater 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuto, H.; Nishizawa, M.; Tada, M.; Higashio, C.; Shishibori, T.; Kohno, M. Zingerone [4-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-butanone] Prevents 6-Hydroxydopamine-induced Dopamine Depression in Mouse Striatum and Increases Superoxide Scavenging Activity in Serum. Neurochem Res 2005, 30, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Jafarzadeh, A.; Nemati, M.; Taghipour, F.; Oladpour, O.; Rezayati, M.T.; Khorramdelazad, H.; Hassan, Z.M. Zingerone improves the immune responses in an animal model of breast cancer. J Altern Complement Med 2021, 18, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharga, K.; Dhar, I.; Kashyap, S.; Sengupta, S.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, L. Zingerone inhibits biofilm formation and enhances antibiotic efficacy against Salmonella biofilm. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Jung, N.; Kim Hyun, J.; Kim, I.; Kim Yun, T.; Kim Byung, J. The Mechanism of Action of Zingerone in the Pacemaker Potentials of Interstitial Cells of Cajal Isolated from Murine Small Intestine. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 46, 2127–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Chung, S.W.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, E.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Ha, Y.M.; Kim, Y.H.; No, J.-K.; Chung, H.S.; Park, K.-Y.; Rhee, S.H.; Choi, J.S.; Yu, B.P.; Yokozawa, T.; Kim, Y.J.; Chung, H.Y. Modulation of age-related NF-κB activation by dietary zingerone via MAPK pathway. Exp Gerontol 2010, 45, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Jeon, Y.; Kim, T.; Lim, W.-C.; Ham, J.; Park, Y.N.; Kim, T.-J.; Ko, H. Combined treatment with zingerone and its novel derivative synergistically inhibits TGF-β1 induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration and invasion of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2017, 27, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Chhibber, S.; Harjai, K. Zingerone inhibit biofilm formation and improve antibiofilm efficacy of ciprofloxacin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Fitoterapia 2013, 90, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, L.; Chhibber, S.; Harjai, K. Structural alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by zingerone contribute to enhanced susceptibility to antibiotics, serum and phagocytes. Life Sci 2014, 117, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, L.; Chhibber, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, M.; Harjai, K. Zingerone silences quorum sensing and attenuates virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Fitoterapia 2015, 102, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, M.-L.; Lin, P.-Y.; Huang, S.-T.; Tai, M.-H.; Hsieh, S.-L.; Wu, C.-C.; Yeh, B.-W.; Wu, W.-J.; Hsieh, S. Zingerone Nanotetramer Strengthened the Polypharmacological Efficacy of Zingerone on Human Hepatoma Cell Lines. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 11, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larijanian L, Shafie M, Pirbalouti AG, Ferdousi A, Chiani M (2024) Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of zingerone and niosomal zingerone against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)s. Iran J Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Oh, S.W.; Shin, S.W.; Lee, K.-W.; Cho, J.-Y.; Lee, J. Zingerone protects keratinocyte stem cells from UVB-induced damage. Chem Biol Interact 2018, 279, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Ku, S.-K.; Kim, M.-A.; Bae, J.-S. Anti-factor Xa activities of zingerone with anti-platelet aggregation activity. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2017, 105, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-L.; Cui, Y.; Guo, X.-H.; Ma, K.; Tian, P.; Feng, J.; Wang, J.-M. Pharmacokinetics and Tissue Distribution of Gingerols and Shogaols from Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) in Rats by UPLC–Q-Exactive–HRMS. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, D.; Fan, S.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; Dong, Y.; Cui, J.; Duan, Y.; Wu, J. Protective effects of zingerone derivate on ionizing radiation-induced intestinal injury. J Radiat Res 2019, 60, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Simon, S.A. Similarities and differences in the currents activated by capsaicin, piperine, and zingerone in rat trigeminal ganglion cells. J Neurophysiol 1996, 76, 1858–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Welch, J.M.; Erickson, R.P.; Reinhart, P.H.; Simon, S.A. Different responses to repeated applications of zingerone in behavioral studies, recordings from intact and cultured TG neurons, and from VR1 receptors. Physiol Behav 2000, 69, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Arivalagan, S.; Islam Siddique, A.; Namasivayam, N. Antihyperlipidemic and antiapoptotic potential of zingerone on alcohol induced hepatotoxicity in experimental rats. Chem Biol Interact 2017, 272, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, V.; Arivalagan, S.; Siddique, A.I.; Namasivayam, N. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory role of zingerone in ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2016, 421, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Q.-Q.; Xu, X.-Y.; Cao, S.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y.; Corke, H.; Beta, T.; Li, H.-B. Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monge P, Scheline R, Solheim E. The Metabolism of Zingerone, a Pungent Principle of Ginger. Xenobiotica 2009, 6, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageshwar Rao, B.; Satish Rao, B.S. Antagonistic effects of Zingerone, a phenolic alkanone against radiation-induced cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, apoptosis and oxidative stress in Chinese hamster lung fibroblast cells growing in vitro. Mutagenesis 2010, 25, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounjaijean, S.; Somsak, V. Combination of zingerone and dihydroartemisinin presented synergistic antimalarial activity against Plasmodium berghei infection in BALB/c mice as in vivo model. Parasitol Int 2020, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulbutr, P.; Thunchomna, K.; Lawa, K.; Mangkhalat, A.; Saenubol, P. Lipolytic Effects of Zingerone in Adipocytes Isolated from Normal Diet-Fed Rats and High Fat Diet-Fed Rats. International Journal of Pharmacology 2011, 7, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulla Reddy, A.C.; Lokesh, B.R. Studies on spice principles as antioxidants in the inhibition of lipid peroxidation of rat liver microsomes. Mol Cell Biochem 1992, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.N.; Archana, P.R.; Aithal, B.K.; Rao, B.S.S. Protective effect of Zingerone, a dietary compound against radiation induced genetic damage and apoptosis in human lymphocytes. Eur J Pharmacol 2011, 657, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.N.; Rao, B.S.S.; Aithal, B.K.; Kumar, M.R.S. Radiomodifying and anticlastogenic effect of Zingerone on Swiss albino mice exposed to whole body gamma radiation. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2009, 677, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Wali, A.F.; Rashid, S.M.; Alsaffar, R.M.; Ahmad, A.; Jan, B.L.; Paray, B.A.; Alqahtani, S.M.A.; Arafah, A.; Rehman, U. Zingerone Targets Status Epilepticus by Blocking Hippocampal Neurodegeneration via Regulation of Redox Imbalance, Inflammation and Apoptosis. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, S.; Singh, B.; Kumar, R.; Pendem, C.; Bhandari, S.; Natte, K.; Narani, A. Value addition of lignin to zingerone using recyclable AlPO4 and Ni/LRC catalysts. Chem Eng J 2022, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Bose, S.K.; Chhibber, S.; Harjai, K. Exploring the Therapeutic Efficacy of Zingerone Nanoparticles in Treating Biofilm-Associated Pyelonephritis Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the Murine Model. Inflammation 2020, 43, 2344–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; Nirbhavane, P.; Chhibber, S.; Harjai, K. Sustained release of Zingerone from polymeric nanoparticles: An anti-virulence strategy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bioact Compat Polym 2020, 35, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.-G.; Kim, J.Y.; Chung, H.Y.; Jeong, J.-C. Zingerone as an Antioxidant against Peroxynitrite. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53, 7617–7622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistani Karampour, N.; Arzi, A.; Rezaie, A.; Pashmforoosh, M.; Kordi, F. Gastroprotective Effect of Zingerone on Ethanol-Induced Gastric Ulcers in Rats. Medicina 2019, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songvut, P.; Nakareangrit, W.; Cholpraipimolrat, W.; Kwangjai, J.; Worasuttayangkurn, L.; Watcharasit, P.; Satayavivad, J. Unraveling the interconversion pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of the major ginger constituents: [6]-gingerol, [6]-shogaol, and zingerone after single-dose administration in rats. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1391019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanely Mainzen Prince, P.; Hemalatha, K.L. A molecular mechanism on the antiapoptotic effects of zingerone in isoproterenol induced myocardial infarcted rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2018, 821, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Krishna Mohan, S.; Lu, W. A ginger derivative, zingerone—a phenolic compound—induces ROS-mediated apoptosis in colon cancer cells (HCT-116). J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2019, 33, e22403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunnap, O.; Subramanian, S.; Vemula, P.K.; Karuppannan, S. Zingerone-encapsulated Solid Lipid Nanoparticles as Oral Drug-delivery Systems to Potentially Target Inflammatory Diseases. Chem Nano Mat 2022, 8, e202200388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surh, Y.-J. Molecular mechanisms of chemopreventive effects of selected dietary and medicinal phenolic substances. Mutat Res 1999, 428, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svetaz, L.; Di Liberto, M.; Zanardi, M.; Suárez, A.; Zacchino, S. Efficient Production of the Flavoring Agent Zingerone and of both (R)- and (S)-Zingerols via Green Fungal Biocatalysis. Comparative Antifungal Activities between Enantiomers. Int J Mol Sci 2014, 15, 22042–22058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.H.; Nishida, R. Zingerone in the floral synomone of Bulbophyllum baileyi (Orchidaceae) attracts Bactrocera fruit flies during pollination. Biochem Syst Ecol 2007, 35, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaibhav, K.; Shrivastava, P.; Tabassum, R.; Khan, A.; Javed, H.; Ahmed, M.E.; Islam, F.; Safhi, M.M.; Islam, F. Delayed administration of zingerone mitigates the behavioral and histological alteration via repression of oxidative stress and intrinsic programmed cell death in focal transient ischemic rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2013, 113, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinothkumar, R.; Vinothkumar, R.; Sudha, M.; Nalini, N. Chemopreventive effect of zingerone against colon carcinogenesis induced by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine in rats. Eur J Cancer Prev 2014, 23, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Yan, J.; Xie, J. Nutritional components, phytochemical compositions, biological properties, and potential food applications of ginger (Zingiber officinale): A comprehensive review. J Food Compos Anal 2024, 128, 106057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).