1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a heterogeneous lung disease characterized by chronic respiratory symptoms, such as dyspnea, cough, sputum production, and exacerbation, due to abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) and/or alveoli (emphysema), causing persistent, often progressive, airflow obstruction. Smoking remains a main risk factor for COPD development and progression [

1].

The inflammatory response mediated by innate and adaptive immune cells has been described in the development and progression of COPD, and the importance of Th17 cytokines has been observed since the early stages of this disease [

2,

3]. Neutrophil recruitment is present from the earlier stages, and they are mainly related to IL-17A and IL-17A/F activation. The activation of IL-17 receptors expressed on bronchial epithelial cells orchestrates the neutrophil chemotactic factors secretion, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or the chemokine CXC ligand (CXCL)8, cytokines such as IL-6, and antimicrobial peptides such as β-defensins and S100 proteins [

4,

5].

Regarding the adaptive immune response, depending on the COPD stage, the Th17 cytokines could be found in lung and blood samples. Lourenço JD et al. [

6] evaluated the gene expression of intracellular proteins and related cytokines involved in Th17 response in both mild and moderate COPD patients and compared the local and systemic responses. They showed that intracellular signaling for the Th17 response was also present from the early stages of this disease. Th17 markers could be observed in lung samples from mild COPD, whereas, in moderate stages, they were observed also in blood samples.

Although there are many current therapeutic approaches to managing COPD, healthcare professionals face numerous challenges in this field. These challenges can be attributed to the heterogeneity of the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development and progression of COPD [

7]. COPD is mostly treated with bronchodilators and eventually with corticosteroid therapy [

8]. The importance of steroid therapy in type 17-mediated pulmonary inflammation has already been studied in other pulmonary disease models [

9,

10]. However, the use of steroids is associated with many adverse events, mainly with the cumulative dose due to the common re-current pulmonary infections in COPD patients [

11].

Previous studies have shown that anti-IL-17 decreases inflammation in experimental models of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- induced acute lung injury and chronic allergic lung inflammation exacerbated with LPS [

12,

13,

14]. Also, Fukuzaki S et al. [

15] tested the therapeutic effect of anti-IL-17 in an elastase-induced lung injury in mice, and they noticed an attenuation in most of the inflammation and lung remodeling parameters in this model of lung injury.

Considering that tobacco smoking is the main etiological factor contributing to the development of COPD in humans, our research group has previously investigated the importance of Th17 cytokines in an animal model of cigarette smoke (CS) exposure and a CS-induced model associated with LPS administration. We showed that in both models there was a skewing for Th17 immune response, which was associated with a decline in respiratory mechanics and histological parameters changes that characterize COPD development, resembling certain clinical findings in humans.

Thus, in this study, we evaluated the effects of administering an Il-17 neutralizing antibody in functional and histological lung parameters in a CS-induced COPD model in mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human and Animal Research of the Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo (Animal Use Ethics Committee—CEUA protocol number 1452/2020). Male C57BL/6 mice, 6–8 weeks old, were used. All animals received humane care in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

2.2. Induction of emphysema

The animals were exposed to cigarette smoke for 30 minutes/day, twice a day, 5 times/week, for 6 months. The exposure was conducted in an inhalation chamber, a 28-liter plastic box (approximately 40x27 cm at the base, with a height of 26 cm) with two air inlets: synthetic air and cigarette smoke. A small fan for air homogenization is at the top of this box. The airflow inside the compartment is controlled by a flow meter connected to a compressed air torpedo and will be maintained at 2 L/min. The second air inlet receives a mixture of synthetic air and cigarette smoke, drawn in by a Venturi system connected to the lit cigarette. The laminar flow of synthetic air passes through a region of smaller diameter, resulting in an acceleration of the flow and a consequent reduction in pressure at this point, known as the Venturi effect, which facilitates the aspiration of cigarette smoke. The decrease in pressure at the point of diameter reduction in the tube depends on the airflow, which is kept constant. This system creates a concentration of carbon monoxide ranging from 250 to 350 ppm (ToxiPro, Biosystems, USA) [

16].

2.3. IL-17 Neutralizing Antibody Administration

An anti-IL-17A (clone 50104) neutralizing antibody (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) was administered by intraperitoneal injection 1 hour before each cigarette smoke exposure at a dose of 7.5 μg/application during the last month of exposure. Each animal received 16 applications in total [

14,

17].

2.4. Experimental Groups

The animals were divided into four different experimental groups:

Control Group (CONTROL): animals not exposed to cigarette smoke that received IL-17 neutralizing antibody administration (n=12).

COPD Group (COPD): animals exposed to cigarette smoke for 6 months (n=9).

COPD Group + anti-IL17 (COPD Anti IL-17): animals were exposed to cigarette smoke for 6 months and received IL-17 neutralizing antibody administration (n=8).

2.5. Respiratory Mechanics

The animals were anesthetized with Thiopental (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally), tracheostomized, and

placed on a rodent mechanical ventilator (flexiVent, SCIREQ, Montreal, Canada) for respiratory mechanics assessment. They were ventilated with a tidal volume of 10 mL/kg and a respiratory rate of 120 cycles per minute. Using the previously described constant-phase model, airway resistance (Raw), tissue damping (Gtis), and tissue elastance (Htis) parameters were calculated [

18].

2.6. Lung Preparation

After the respiratory mechanic assessment, mice were euthanized by exsanguination through the abdominal aorta, and their lungs were removed and fixed at a constant pressure of 20 cmH

2O using 10% buffered formalin infused through the trachea for 24 hours [

19]. The lungs were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-µm sections for histological and morphometric evaluation.

2.7. Morphometry

The tissue samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H.E) for conventional morphometry to perform the mean linear intercept (Lm) measurements. Lm was obtained by counting the number of times that the lines of the reticulum, containing 50 lines and 100 points, intercepted the alveolar walls. We performed the Lm analysis in distal areas of parenchyma (peripheral airspaces) and used the following equation: Lm = Ltotal/NI

6 where Ltotal is the sum of all grid segments, calculated by measuring each segment with a ruler (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) attached to the microscope, and NI is the average number of times that the lines intersected the alveolar walls. All Lm values were expressed in micrometers (μm) [

20].

2.8. Cell Density

To count the number of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells in the peribronchovascular areas, a Weibel reticle (100 points and 50 lines) was attached to the eyepiece of a standard optical microscope, used in a known area on the 100x objective with immersion oil. The quantification of cells in the edema area between the vessel and the airway was done by reading 15 fields/slide (Hematoxylin & Eosin) [

21].

2.9. Positive Cells by Immunohistochemistry for IL-17 Detection

Lung sections (5 µm thick) were deparaffinized and hydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed, and the sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide at room temperature. Then, the sections were incubated with a mouse anti-IL-17 antibody (Santa Cruz, SC374218) at a dilution of 1:200. The primary antibody was diluted in bovine serum albumin (BSA) overnight (16–18 hours) in a humidified chamber at 4–8 °C. Subsequently, the sections were washed in PBS and incubated with a secondary antibody (Vector ABCElite, horseradish peroxidase [HRP]; anti-mouse) at 37 °C in a humidified chamber. Three additional 5-minute washes in PBS were performed, and the samples were stained with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (code K3468, Dako Citomation, Fort Collins, CO, USA) for 5 min. Subsequently, the tissues were washed with tap water and counterstained with Harris hematoxylin. Cell density was assessed by the number of cells divided by the respective peribronchovascular area (10

4 cells/µm2) in 15 fields/slide. Analysis was performed using an optical microscope equipped with an integrating eyepiece containing a known area (104 μm² at ×1000 magnification), consisting of 50 lines and 100 points [

21].

2.10. Cytokine Analysis

The lungs were removed, stored in labeled tubes containing crushed ice, and then individually homogenized. To detect the cytokine levels was determined by ELISA (OptEIA, BD PharMingen, Oxford, UK) using microplates (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) for each cytokine sensitized with specific monoclonal antibodies. After the samples were washed, specific antibodies were added to the different cytokines conjugated to biotin. After the solution contained streptavidin-peroxidase, substrate, and chromogen enzyme conjugate were added. The reaction was read at 450 nm using an M2 spectrophotometer (Molecules Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Sample concentrations were calculated from the standard curves obtained with the recombinant cytokines, and the results were expressed in units of pg/ml. R&D Systems ELISA kits determined interleukin (IL-6 and IL-17) and TGF-β expression [

22].

2.11. Real-Time PCR

Gene expression was evaluated using Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) in a Rotor Gene (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) thermal cycler and a Syber Green kit as a fluorescent marker (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Reactions occurred in the following steps: 95°C for 5 minutes, 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 seconds (denaturation) and 60°C for 10 seconds (annealing and extension). The PCR products were run on agarose gel to confirm fragment sizes and the specificity of the reaction. The primers were designed and used to quantify messenger RNA (mRNA) encoded by the genes described below. Analysis was performed using the software provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, an arbitrary number of copies of the genes of interest and constituents was calculated using a formula (1000000/2CT, where CT is the number of amplification cycles required to reach the threshold determined at the exponential phase of the curve) for each sample. The values are presented as the number of copies relative to the control after correction with the constitutive GAPDH [

22].

Table 1.

Sense and antisense sequences of the primers used in qPCR.

Table 1.

Sense and antisense sequences of the primers used in qPCR.

| Gene |

5′ Primer (5′-3′) |

3′ Primer (5′-3′) |

| RORyt |

TAGCACTGACGGCCAACTTA |

TCGGAAGGACTTGCAGACAT |

| GAPDH |

CCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG |

CTTGGGCTACACTGAGGACC |

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SigmaStat program (version 11.0; Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). We used the one-way ANOVA test followed by the multiple-comparison test (Holm-Sidak). Results were expressed as means ± standard error (SE), and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

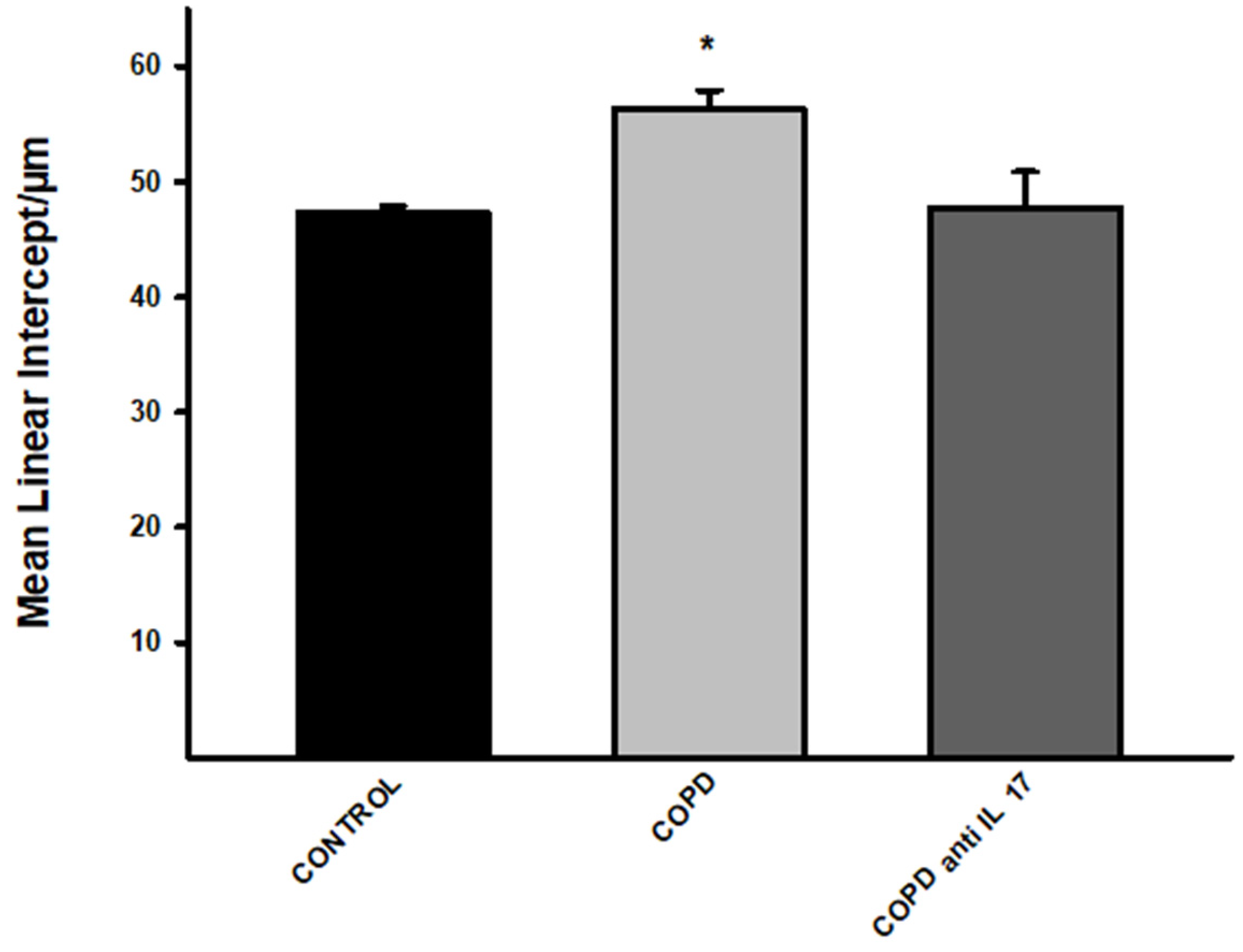

3.1. Increase in Lm

There was an increase in alveolar enlargement in the COPD group compared to the other experimental groups (Control and Anti IL17 COPD) (

Figure 1).

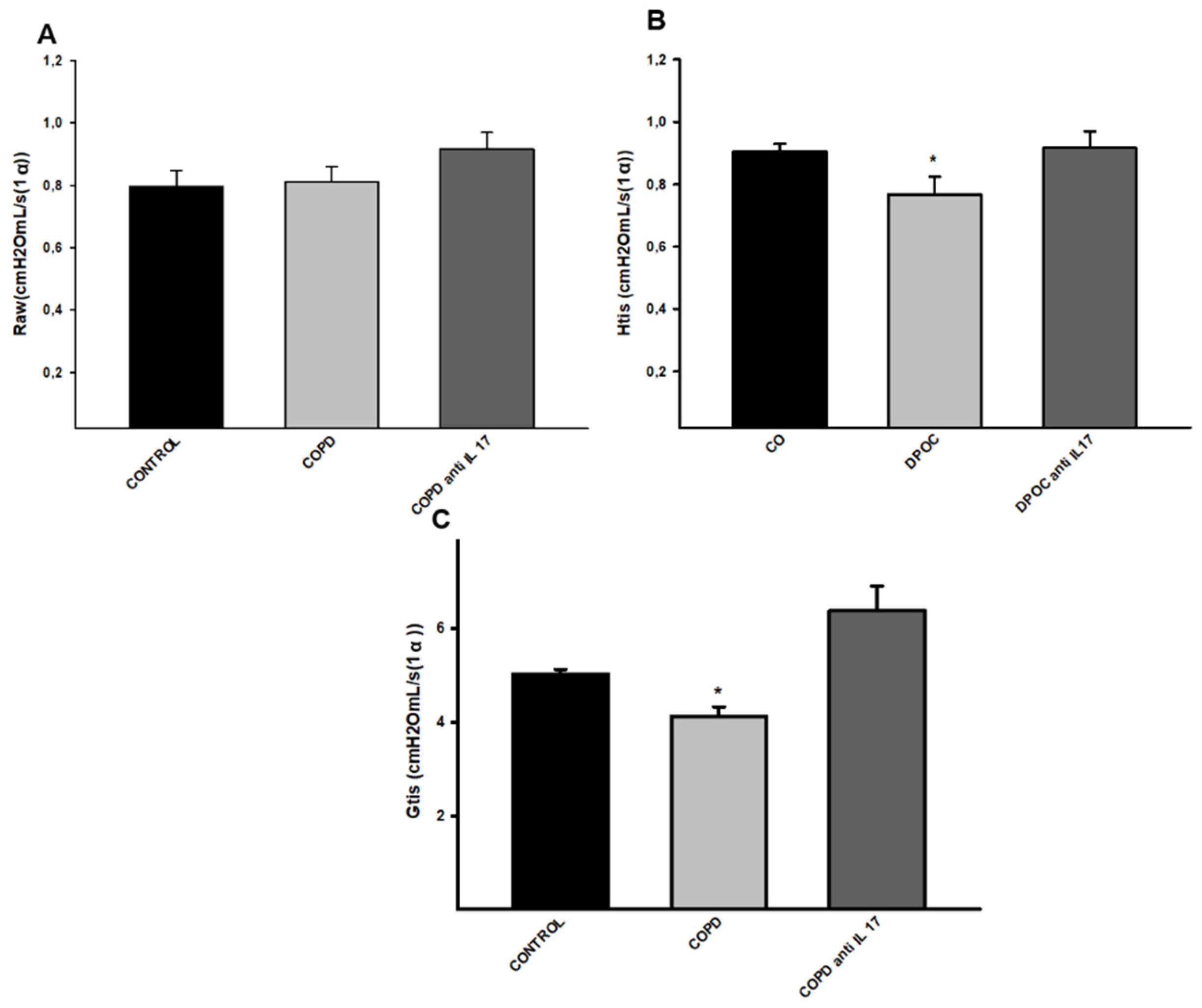

3.2. Decrease in Parameters Related to Respiratory Mechanics

No statistical difference was observed for the Raw parameter (airway resistance) comparing all experimental groups (

Figure 2A). There was a decrease in Htis values (tissue elastance) in the COPD group compared to the other groups (

Figure 2B). There was a decrease in Gtis values (tissue resistance) in the COPD group compared to the other groups, and treatment with anti-IL17 reverted this parameter change. (

Figure 2C).

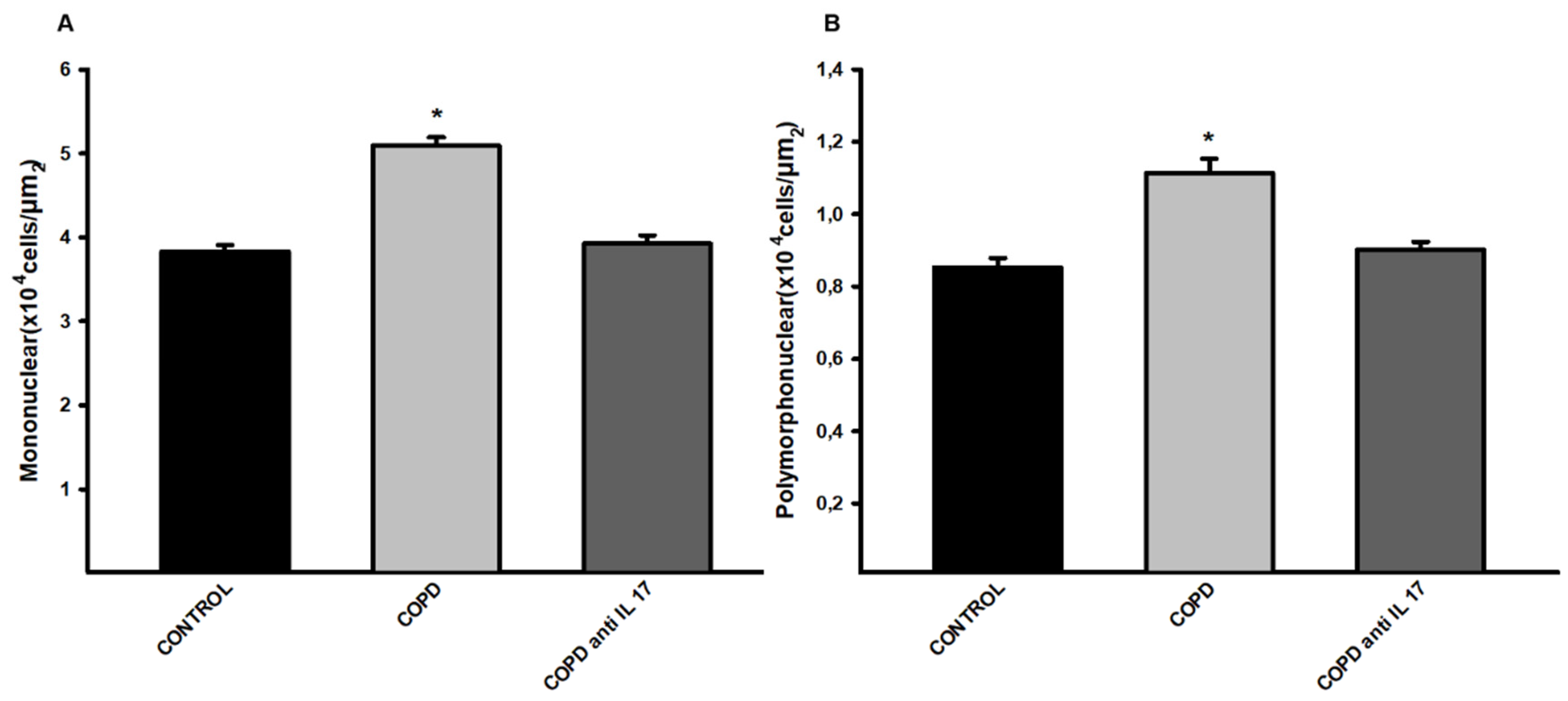

3.3. Density of Cells in the Peribronchoalveolar Space

There was an increase in mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells in the COPD group compared to the Control and COPD anti IL-17 groups. (

Figure 3).

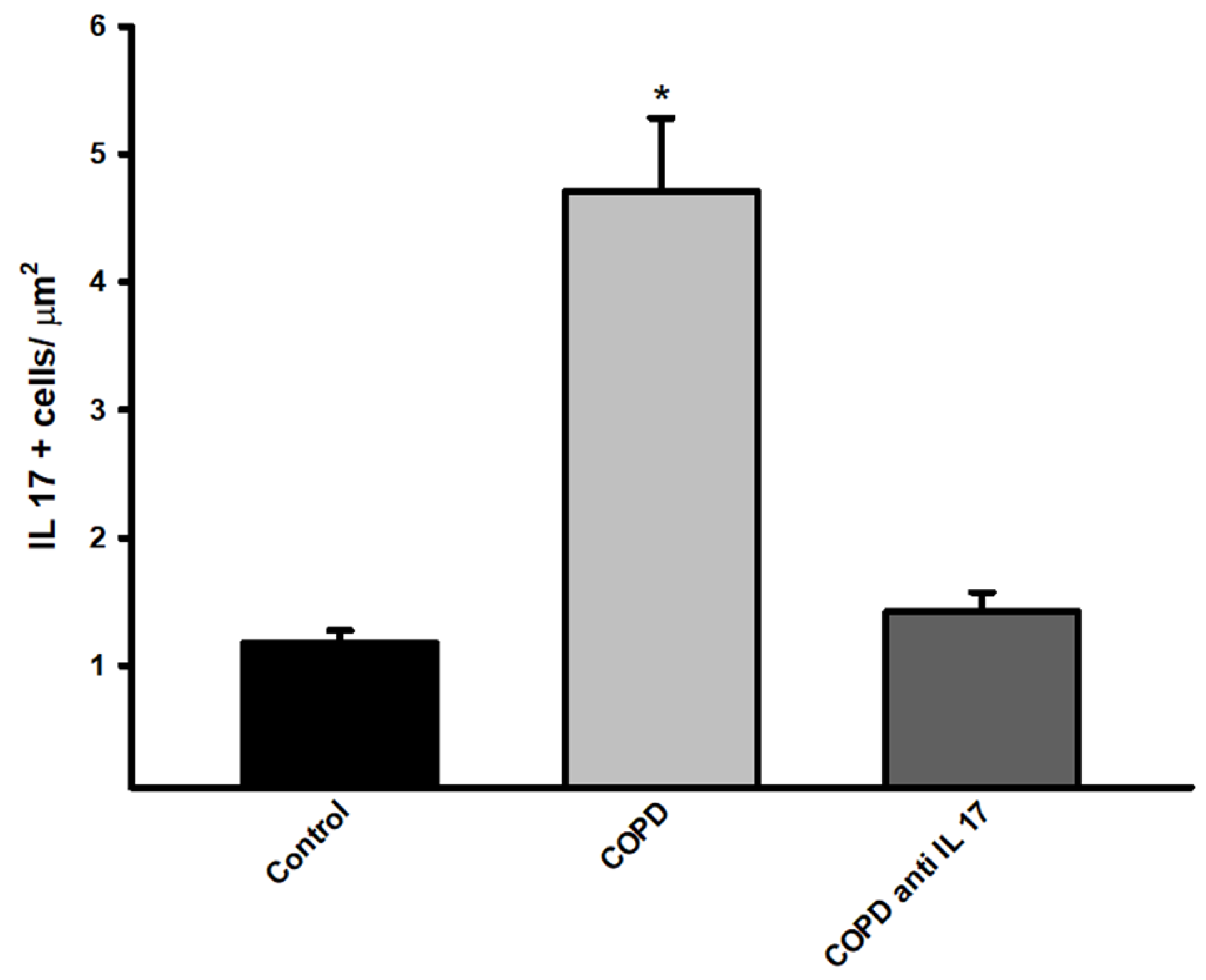

There was an increase in immunohistochemistry on IL-17 positive cells compared to expression in the Control and COPD anti IL-17groups (

Figure 4).

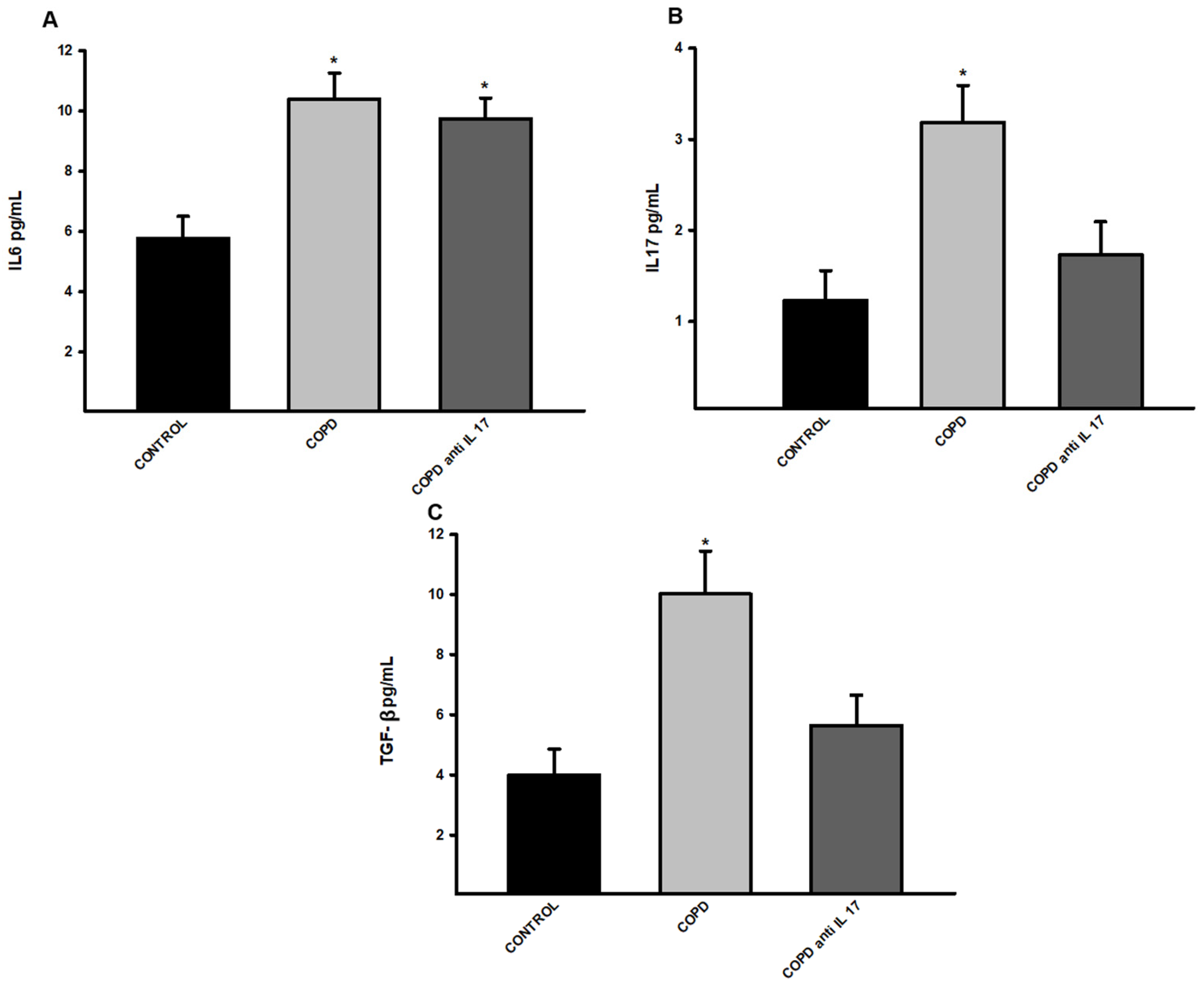

3.4. Increased Expression of Cytokines by ELISA

There was an increase in IL-6 protein levels in the groups exposed to cigarette smoke compared to the control group (

Figure 4A). There was an increase in IL-17 and TGF- β protein levels in the group exposed to cigarette smoke compared to the Control and COPD anti IL-17 groups (

Figure 5B,C).

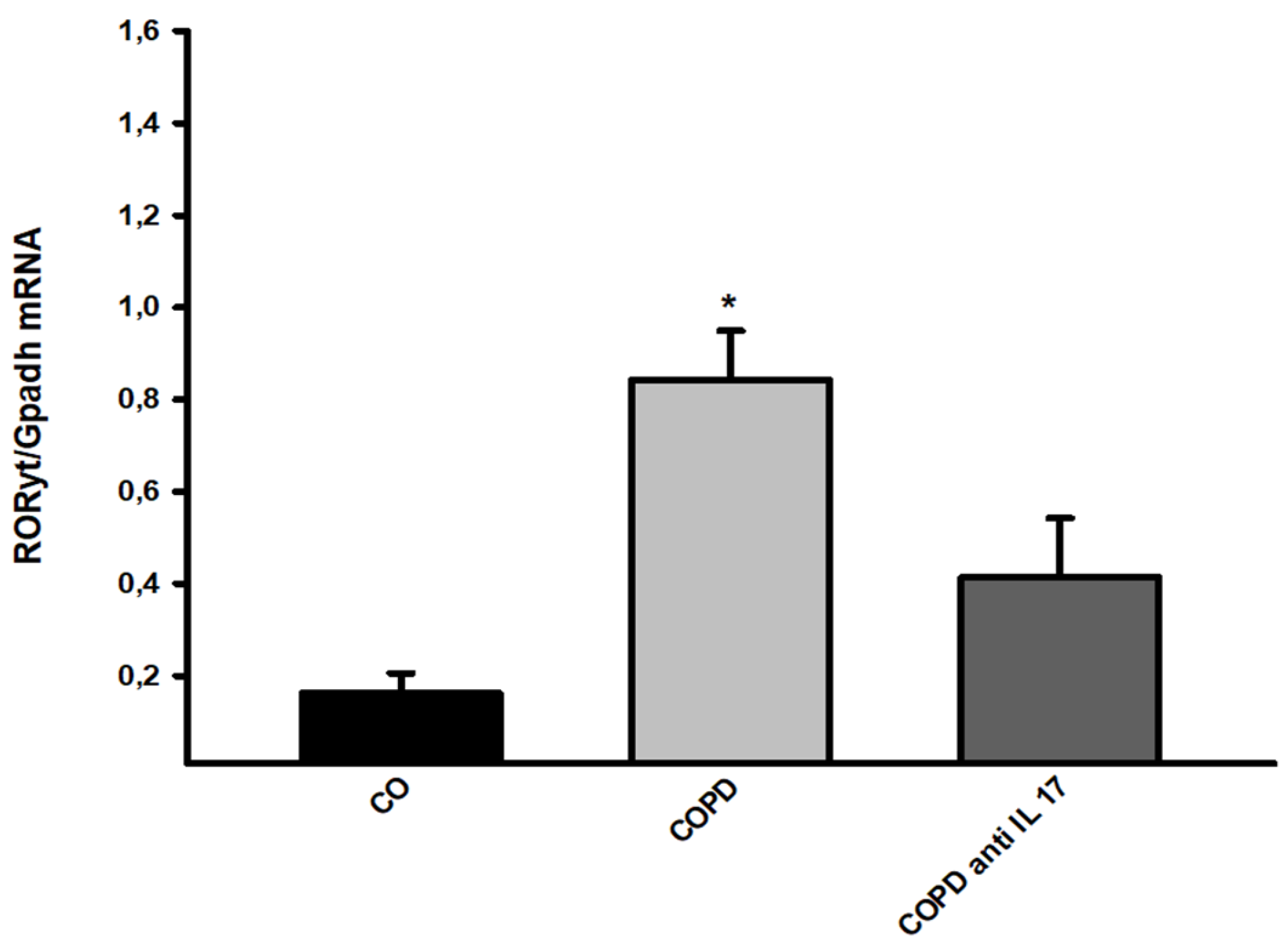

3.5. Gene Expression

Gene expression assessment for RORyt showed an increase in cigarette smoke-exposed groups compared to the others (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

Our results showed that IL-17 neutralizing antibody administration reverts the inflammatory response mediated by Th17 cytokine in the lungs, recovering the functional and structural changes induced by CS exposure in an experimental model of COPD.

We showed that there was a recovery of lung elastic recoil by the analysis of tissue elastance (Htis) and tissue damping (Gtis) after the IL-17 neutralizing antibody administration in animals that were exposed to CS, which corroborates with findings that described the Lm parameter. The increased alveolar enlargement observed in the CS group was not observed in animals exposed to CS that received the IL-17 inhibitor administration.

The analysis of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells evaluated in the peribronchovascular areas revealed that the administration of the IL-17 neutralizing antibody inhibits the migration of these inflammatory to the lungs. Neutrophils and macrophages are recognized for their importance in alveolar parenchyma destruction by delivering metalloproteinases (MMP) [

23]. Thus, the migration inhibition of these inflammatory cells to the lungs avoids the perpetuation of the alveolar wall destruction, which corroborates with respiratory mechanics and Lm data.

The importance of Th17 response has been described as playing a pivotal role in the development and progression of COPD [

24,

25]. The differentiation of CD4+ T cells to TH17 cells depends on the cytokines in the microenvironment, such as IL-6, by its importance to the expression of the nuclear factor RORyT [

26]. Interestingly, we did not find the effects of IL-17 inhibitor in this interleukin expression in the lungs, since both groups exposed to CS showed IL-6 expression increased compared with the Control group. These results are in accordance with the analysis of RORyT gene expression in the lungs homogenates since they showed an increased expression of this nuclear factor in the COPD and COPD Anti-IL17 group compared with the Control Group. In contrast, the results of IL-17 expression in the lung homogenates revealed the effects of this inhibitor in the diminishment of this interleukin expression. Moreover, we could observe a statistical decrease in +IL-17 lymphocytes in peribronchovascular areas in the COPD anti-IL-17 group compared with the COPD group.

In this experimental model, we previously demonstrated that after one month of CS exposure, the alveolar walls enlarged, showing a progression over time, and the elastic recoil loss was observed from the third month [

27]. In the present study, IL-17 inhibitor administration begins only in the fifth month, after alveolar enlargement and changes in lung mechanics have already occurred. Nevertheless, we observed a recovery of the lung parenchyma tissue and in lung mechanics parameters. Further investigation is necessary to better understand the impact of this inhibitor administration on the remodeling of extracellular matrix components, mediated by macrophages and neutrophils through the release of metalloproteases and their inhibitors. This could help explain the recovery of alveolar parenchyma and the improvement in respiratory mechanics parameters, even after lung tissue destruction has been established.

In recent years several monoclonal antibodies have been developed and tested as potent inhibitors of IL-17 in various inflammatory diseases to cease its induction or eliminate IL-17-producing cells [

28]Although the importance of IL-17 release by innate and adaptive immune cells in COPD development and progression has been extensively described, there are few studies evaluating the effects of inhibiting this interleukin after the disease has established.

This is the first study to demonstrate the potential therapeutic effects of administering an IL-17-neutralizing antibody in restoring functional and structural changes in a COPD-induced model caused by CS exposure.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the benefits of administering IL-17 neutralizing antibodies to restore both functional and structural changes in a COPD model induced by CS exposure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.M. and F.D.Q.S.L.; methodology, A.R.M., C.U.S., L.P.M.C., V.C.B., F.J.L., A.F.S., C.N.S., S.K.M.B.; validation, A.R.M., S.K.M.B; formal analysis, A.R.M., C.U.S., V.C.B.; investigation, A.R.M., L.P.M.C.; resources M.I.C.A.V., I.F.L.C.T.; F.D.Q.S.L; data curation C.U.S., L.P.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.M., J.J.S., M.I.C.A.V., F.M.A., F.D.Q.S.L ; writing—review and editing, A.R.M., F.M.A., F.D.Q.S.L; supervision, F.M.A., F.D.Q.S.L.; funding acquisition, I.F.L.C.T and F.D.Q.S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

Fundação de Amparo `a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo—FAPESP (2020/12863-7; 2018/02537-5; 2023/00549-4); Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico- CNPq (302957/2021-9).

Ethics Committee

Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Animal (CEUA protocol number 1452/2020, date of approval 04/28/2020).

Acknowledgments

LIM-20: LIM-11, LIM-50, FITAE-UNIFESP equippaments to analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| Lm |

Mean linear intercept |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| RORγt |

Factor Retinoic Acid-Related Orphan Receptor gamma t

|

| CXCL-8 |

Chemokine CXC ligand |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| CS |

Cigarette smoke |

| Th |

T helper |

| CEUA |

Animal Use Ethics Committee |

| Raw |

Airway resistance |

| Gtis |

Tissue damping |

| Htis |

Tissue elastance |

| H. E |

Hematoxylin and eosin |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| BSA |

Bovine serum albumin |

| HRP |

Horseradish peroxidase |

| DAB |

Diaminobenzidine |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| GAPDH |

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| TGF- β |

Transforming growth factor beta |

| MMP |

Metalloproteinases |

References

- GOLD. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis M and P of COPD. GLOBAL Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2024;208.

- Lourenço JD, Ito JT, Martins M de A, Tibério I de FLC, Lopes FDTQ dos S. Th17/Treg Imbalance in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Clinical and Experimental Evidence. Vol. 12, Frontiers in Immunology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2021.

- Rouzic OL PME al. Th 17 cytokines: novel potential therapeutic targets for COPD pathogenesis and exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2017 Jul;

- Rathore JS, Wang Y. Protective role of Th17 cells in pulmonary infection. Vol. 34, Vaccine. Elsevier Ltd.; 2016. p. 1504–14. [CrossRef]

- Pappu R, Rutz S, Ouyang W. Regulation of epithelial immunity by IL-17 family cytokines. Vol. 33, Trends in Immunology. 2012. p. 343–9. [CrossRef]

- Lourenço JD, Teodoro WR, Barbeiro DF, Velosa APP, Silva LEF, Kohler JB, et al. Th17/treg-related intracellular signaling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Comparison between local and systemic responses. Cells. 2021 Jul 1;10(7).

- Vogelmeier CF, Román-Rodríguez M, Singh D, Han MLK, Rodríguez-Roisin R, Ferguson GT. Goals of COPD treatment: Focus on symptoms and exacerbations. Vol. 166, Respiratory Medicine. W.B. Saunders Ltd.; 2020. [CrossRef]

- GOLD Report. Vol. 93, Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier Ltd.; 2018. p. 1488–502.

- Wang H, Ying H, Wang S, Gu X, Weng Y, Peng W, et al. Imbalance of peripheral blood Th17 and Treg responses in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical Respiratory Journal. 2015 Jul 1;9(3):330–41. [CrossRef]

- Banuelos J, Shin S, Cao Y, Bochner BS, Morales-Nebreda L, Budinger GRS, et al. BCL-2 protects human and mouse Th17 cells from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2016 May 1;71(5):640–50. [CrossRef]

- Ko FW, Chan KP, Hui DS, Goddard JR, Shaw JG, Reid DW, et al. Acute exacerbation of COPD. Vol. 21, Respirology. Blackwell Publishing; 2016. p. 1152–65.

- Righetti RF, Dos Santos TM, Camargo LDN, Barbosa Aristóteles LRCR, Fukuzaki S, De Souza FCR, et al. Protective effects of anti-IL17 on acute lung injury induced by LPS in mice. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Oct 4;9(OCT). [CrossRef]

- dos Santos TM, Righetti RF, Camargo L do N, Saraiva-Romanholo BM, Aristoteles LRCRB, de Souza FCR, et al. Effect of anti-IL17 antibody treatment alone and in combination with Rho-kinase inhibitor in a murine model of asthma. Front Physiol. 2018 Sep 5;9(SEP).

- Camargo L do N, Righetti RF, Aristóteles LR de CRB, dos Santos TM, de Souza FCR, Fukuzaki S, et al. Effects of Anti-IL-17 on Inflammation, Remodeling, and Oxidative Stress in an Experimental Model of Asthma Exacerbated by LPS. Front Immunol. 2018 Jan 5;8.

- Fukuzaki S, Righetti RF, dos Santos TM, do Nascimento Camargo L, Aristóteles LRCRB, Souza FCR, et al. Preventive and therapeutic effect of anti-IL-17 in an experimental model of elastase-induced lung injury in C57Bl6 mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021 Mar 1;320(3):C341–54. [CrossRef]

- Ito JT, Lourenço JD, Righetti RF, Tibério IFLC, Prado CM, Lopes FDTQS. Extracellular Matrix Component Remodeling in Respiratory Diseases: What Has Been Found in Clinical and Experimental Studies? Cells. 2019. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos TM, Righetti RF, Camargo L do N, Saraiva-Romanholo BM, Aristoteles LRCRB, de Souza FCR, et al. Effect of anti-IL17 antibody treatment alone and in combination with Rho-kinase inhibitor in a murine model of asthma. Front Physiol. 2018 Sep 5;9(SEP).

- Hantos Z, Daroczy B, Suki B, Nagy S, Fredberg JJ, Dar~czy B, et al. Input impedance and peripheral inhomogeneity of dog lungs [Internet]. 1992. Available from: www.physiology.org/journal/jappl. [CrossRef]

- Toledo AC, Magalhaes RM, Hizume DC, Vieira RP, Biselli PJC, Moriya HT, et al. Aerobic exercise attenuates pulmonary injury induced by exposure to cigarette smoke. European Respiratory Journal. 2012 Feb 1;39(2):254–64. [CrossRef]

- Cervilha DAB, Ito JT, Lourenço JD, Olivo CR, Saraiva-Romanholo BM, Volpini RA, et al. The Th17/Treg Cytokine Imbalance in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbation in an Animal Model of Cigarette Smoke Exposure and Lipopolysaccharide Challenge Association. Sci Rep. 2019 Dec 1;9(1).

- de Genaro IS, de Almeida FM, dos Santos Lopes FDTQ, Kunzler DDCH, Tripode BGB, Kurdejak A, et al. Low-dose chlorine exposure impairs lung function, inflammation and oxidative stress in mice. Life Sci. 2021 Feb 15;267.

- Simao J de J, Bispo AF de S, Plata VTG, Abel ABM, Saran RJ, Barcella JF, et al. The Activation of the NF-κB Pathway in Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Alters the Deposition of Epigenetic Marks on H3K27 and Is Modulated by Fish Oil. Life. 2024 Dec 1;14(12).

- Silva MT, Correia-Neves M. Neutrophils and macrophages: The main partners of phagocyte cell systems. Front Immunol. 2012;3(JUL). [CrossRef]

- Alves LHV, Ito JT, Almeida FM, Oliveira LM, Stelmach R, Tibério lolanda FLC, et al. Phenotypes of regulatory T cells in different stages of COPD. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024 Oct 25;140. [CrossRef]

- Ito JT, Alves LHV, Oliveira L de M, Xavier RF, Carvalho-Pinto RM, Tibério I de FLC, et al. Effect of exercise training on modulating the TH17/TREG imbalance in individuals with severe COPD: A randomized controlled trial. Pulmonology. 2025 Dec 31;31(1):2441069.

- McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ. Th17 Cell Differentiation: The Long and Winding Road. Vol. 28, Immunity. 2008. p. 445–53. [CrossRef]

- Ito JT, De Brito Cervilha DA, Lourenço JD, Gonçalves NG, Volpini RA, Caldini EG, et al. Th17/Treg imbalance in COPD progression: A temporal analysis using a CS-induced model. PLoS One. 2019 Jan 1;14(1).

- Simopoulou Theodora SGTEZ and DPB. Secukinumab, ixekizumab, bimekizumab and brodalumab for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Drugs of Today. 2023.

Figure 1.

Mean Linear Intercept. Control group n=11, COPD n=7, COPD anti-IL17 n=7; Lm values in distal areas of the parenchyma are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p= 0.009 compared to Control and COPD anti-IL17 groups.

Figure 1.

Mean Linear Intercept. Control group n=11, COPD n=7, COPD anti-IL17 n=7; Lm values in distal areas of the parenchyma are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p= 0.009 compared to Control and COPD anti-IL17 groups.

Figure 2.

Respiratory Mechanics. A, Raw parameter (Control n=7, COPD n=5, COPD anti-IL17 =5); B, Htis values (Control n=8, COPD n=9, COPD anti-IL17 =5); C, Gtis values (Control n=8, COPD n=8, COPD anti-IL17 =7). Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p = <0.001 compared to other groups.

Figure 2.

Respiratory Mechanics. A, Raw parameter (Control n=7, COPD n=5, COPD anti-IL17 =5); B, Htis values (Control n=8, COPD n=9, COPD anti-IL17 =5); C, Gtis values (Control n=8, COPD n=8, COPD anti-IL17 =7). Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p = <0.001 compared to other groups.

Figure 3.

Mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells. A Mononuclear cell; B, polymorphonuclear cells; Control n=12, COPD n=8, COPD anti IL-17 n=8; Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p = <0.001 compared to the Control and COPD anti IL-17 group.

Figure 3.

Mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells. A Mononuclear cell; B, polymorphonuclear cells; Control n=12, COPD n=8, COPD anti IL-17 n=8; Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p = <0.001 compared to the Control and COPD anti IL-17 group.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry by IL-17. Control n=6, COPD n=6, COPD anti IL-17 =6; Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p = <0.001 compared to Control and COPD anti IL-17groups.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry by IL-17. Control n=6, COPD n=6, COPD anti IL-17 =6; Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p = <0.001 compared to Control and COPD anti IL-17groups.

Figure 5.

Expression of cytokines. A, IL-6 protein levels (Control n=6, COPD n=5, COPD anti IL-17 =5); B, IL-17 protein levels (Control n=6, COPD n=5, COPD anti IL-17 =5), C, TGF- β protein levels (Control n=12, COPD n=6, COPD anti IL-17 =7); Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; A, *p = 0.002 compared to Control group; B, *p = 0.004 compared to all groups; C, *p = 0.003 compared to all groups.

Figure 5.

Expression of cytokines. A, IL-6 protein levels (Control n=6, COPD n=5, COPD anti IL-17 =5); B, IL-17 protein levels (Control n=6, COPD n=5, COPD anti IL-17 =5), C, TGF- β protein levels (Control n=12, COPD n=6, COPD anti IL-17 =7); Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; A, *p = 0.002 compared to Control group; B, *p = 0.004 compared to all groups; C, *p = 0.003 compared to all groups.

Figure 6.

RORyt Gene expression. Control n=12, COPD n=6, COPD anti IL-17 =7; Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p = 0.001 compared to Control group.

Figure 6.

RORyt Gene expression. Control n=12, COPD n=6, COPD anti IL-17 =7; Data are expressed as the mean ± SE; *p = 0.001 compared to Control group.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).