1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020. In the three years since the pandemic began, the virus variants have caused 768 million confirmed cases and nearly 7 million associated deaths worldwide, as of 1 September 2023 [

1].

While most COVID-19 patients recovered with a low mortality rate [

2], the chronic features of SARS-COV-2 infection have become increasingly apparent. These common long-lasting symptoms affect 50-70% of hospitalised acute COVID-19 cases and 10-30% of non-hospitalised cases (a total of 5-50%, depending on the study) and have been given alternative names and slightly different definitions [

3]. The current study used the term Post COVID-19 Syndrome, PCS; other commonly used terms include Long COVID, Post Acute COVID-19 Syndrome (PACS), Subacute sequelae of COVID-19 and Chronic COVID Syndrome [

4,

5].

The WHO defines PCS as a syndrome that may occur either as a continuation of the acute illness or as a consequence of a previous infection, with the appearance of new symptoms that were not previously present [

6]. Symptoms may last for weeks, months or years (at least two weeks) and may fluctuate or relapse over time. The diagnosis of PCS requires that clinical symptoms were not present prior to infection, persist for at least two months, cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis, and occur at least 12 weeks after the onset of the acute illness, with patients experiencing significant impairment in daily functioning [

7,

8].

PCS lesions primarily include respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation and mental disorders [

9]. Respiratory changes are the most common; at the beginning of the pandemic, SARS-COV-2 infection was reported to cause permanent respiratory impairment in patients after hospital discharge [

10]. They are often the result of interstitial lung disease (ILD) diagnosed in patients with PCS, also referred to as persistent ILD COVID-19 [

11]. Typical respiratory complaints associated with PCS include fatigue, decreased exercise tolerance, cough and dyspnoea. Clinical findings include abnormal CT images of the lungs and impaired pulmonary function tests [

12].

The pathogenesis of PCS remains unclear. Research has focused on two key mechanisms: the survival of viral antigens in the lower respiratory tract with an ineffective chronic inflammatory response [

15] or, conversely, the complete elimination of the virus with local autoimmunity [

16]. Dysregulation of the immune system, particularly of T cells, including changes in the reciprocal proportions of effector Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells, is possible [

17]. Changes in the expression of immune checkpoints, i.e. molecules expressed on lymphocytes that regulate the intensity of the immune response and ultimately cause apoptotic lymphocyte death, have been detected [

18]. The significant increase in the percentage of CD8+PD1+ cells found in PCS is thought to indicate a down-regulation of the antiviral potential of cytotoxic T cells (exhaustion phenomenon) [

19].

In addition to lymphocytes, neutrophils are import ant cells in the lower airway inflammatory response in patients with PCS [

20]. Their recruitment to the lung interstitium may depend on Th17 effector lymphocytes; however, to our knowledge, this possibility has not been tested.

Examination of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid has been shown to have diagnostic and clinical relevance in acute SARS-COV-2 infection [

21]. In contrast, less is known about the cytological and immunological profiles of BAL in the PCS group [

22].

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the immunocytological profile of PCS in the lower respiratory tract, including the subgroup with persistent changes without current remission. Therefore, we tried to identify (1) BAL changes characteristic for PCS, and (2) BAL abnormalities responsible for worse prognosis in PCS.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patients

We enrolled 58 patients from the Department of Pulmonary Diseases, John Paul II Hospital, Krakow, and the Department of Pulmonary Diseases, Cancer and Tuberculosis, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Bydgoszcz, who were initially suspected of having new-onset ILD. These patients had BAL samples taken between August 2020 and May 2023 as part of a diagnostic work-up and were ultimately diagnosed with PCS. The diagnostic procedure followed the European Respiratory Society guidelines [

23].

All subjects enrolled had a history of acute COVID-19 infection confirmed by PCR or antibody testing in a medical facility or at home. They were enrolled regardless of the severity of the infection or the pandemic wave.

We excluded patients: 1) those with a history of previous interstitial lung disease; 2) those treated with systemic corticosteroids, methotrexate, amiodarone, biologic drugs, or other drugs known to be a potential cause of interstitial lung pathology; 3) those with New York Heart Association class IV heart failure, respiratory failure, or acute coronary syndromes [

1,

2,

14,

23].

Smokers were not analyzed in the study because the number of PCS smokers with BAL examination was insignificant and there were too few smokers in the control group for statistical analysis.

All enrolled patients underwent pulmonary function testing prior to bronchoscopy. They all reported respiratory symptoms and abnormal lung computed tomography (CT) scans showing interstitial lung lesions. The following were considered eligible for extended diagnosis: on chest CT, ground-glass opacities, consolidations, linear and reticular lesions, honeycombing, traction bronchiectases, interlobular septa thickening and reduced lung volumes including vital capacity (VC). The distinction between fibrotic and non-fibrotic symptoms in PCS was made in this study using the Fleischner Society dictionary [

24]. Traction bronchiectasias, honeycomb lesions on CT, and VC volume loss, were considered fibrotic changes. In fact, small residual fibrotic changes may occur as a direct consequence of COVID-19-related ARDS and are found in PCS remission; VC and diffusing lung capacity for CO (DLCO) remain normal in these patients [

2].

Patients were assessed for known risk factors for PCS including: age, sex, comorbidities (arterial hypertension, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD, diabetes, coronary artery disease), vaccination status and severity of acute COVID-19 (subdivided into mild, moderate, severe and critical). Severe (usually pneumonia with hospitalisation) and critical (usually ARDS) acute COVID-19 are considered risk factors for PCS [

2,

24,

25].

The time of BAL examination was at least 12 weeks (3 months) from the end of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection [

26].

Patients underwent follow-up CT lung examinations and functional tests at least 12 months after the BAL and baseline CT lung examinations; this was done as suggested by other authors. [

6,

27]. Patients were divided into 2 groups according to the dynamics of interstitial lung lesions, ventilation and diffusion disorders:

(1) Interstitial lesions with complete or partial resolution by 12 months after the first examination [

28,

29], predictive value of VC and DLCO greater than 80%; these patients were defined as PCS remission (n=33);

(2) Persistent interstitial lesions (defined as both non-fibrotic and fibrotic) observed at 12 months from baseline with associated ventilatory compromise (VC and/or DLCO predicted value less than 80%); patients were defined as having PCS persistence (n=25).

Exceptionally, patients with small fibrotic lesions, assessed as residua following acute illness (especially after COVID-related ARDS), that showed no enlargement and no ventilatory compromise, were classified in the PCS remission subgroup [

2].

The control group consisted of 11 non-smoking subjects with no lung pathology, no symptoms of acute or chronic lung disease, and normal lung function tests, chest X-rays and chest CT scans. They were not treated with corticosteroids or any other medication known to be a potential cause of ILD (see above).

Informed consent was obtained from all enrolled subjects (Bioethics Committee of Nicolaus Copernicus University, approval no KB107/2017 and KB199/2022).

2.2. Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

BAL was performed as a routine diagnostic procedure according to European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines [

18]. BAL fluid fractions were collected by gentle aspiration, combined, filtered and immediately transported to laboratories. Fluid recovery was calculated as a percentage of the instilled volume. Total cell count, cell viability (trypan blue exclusion test) and differential white blood cell count [

23] were calculated.

BAL samples with fluid recovery <30% of the instilled volume and epithelial cell contamination >3% of BAL cells were excluded from further analysis due to poor technical quality [

14].

2.3. BAL Lymphocyte Phenotyping and Flow Cytometry (FC)

All BAL samples met the exact criteria for cytometric material collection and analysis [

18]. Five-colour direct typing was used (flow cytometer BD FACSCantoTM II, BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). BAL samples containing 50 μl of cell suspension (2-10 x 10

6 cells/ml) were incubated with saturating amounts of mouse fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies to human surface markers: CD3, CD4, CD8, CD16+56, CD19, HLA-DR, CD45, CD152 (CTLA4), CD183 (CXCR3), CD194 (CCR4), CD196 (CCR6), CD274 (PDL1), CD279 (PD1); monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Becton-Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA and Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) for 30 min in the dark, washed in PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) and then resuspended in 500 μL PBS containing 1% formaldehyde. The internal control consisted of samples stained with the negative isotype control [

23], with between 10,000 and 100,000 cells collected per sample. Alveolar macrophages, alveolar lymphocytes (AL) and BAL granulocytes were graded according to cell granularity (sidescatter, SSC) and intensity of CD45 staining. The AL phenotype was obtained by dot plot quadrant analysis of the corresponding fluorescent channels [

18]. BAL lymphocyte phenotyping included: 1) major subset typing; 2) assessment of Th effector cell subpopulations (Th1-like cells as CD4+CD183+CD196-. Th2-like cells as CD4+CD194+CD183-CD196- and Th17-like cells as CD4+CD183-CD196+) [

30]; 3) immune checkpoints, ICP, expression study on Th and Tc cells, including the percentage of CD4+PD1+ and CD8+PD1+ cells, i.e. exhausted T cells [

31].

The set of monoclonal antibodies used in the study is presented in the Supplementary Material,

Table S1. The representative dot plots of the flow cytometry analysis are shown in the Supplementary Material,

Figure S2.

2.4. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). BAL Cytokines / Chemokines

The concentration of cytokines (IL-5, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-15, IL-17, IFNγ, TGFβ1,) in BAL supernatants was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems, Quantikine cat. no. IL-5: D5000B, IL-7: HS750; IL-8: D8000, IL-10: D1000B, IL-15: D1500, IL-17: HS170, IFNγ: HSDIFO, TGFβ1: DB100C, Minneapolis, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Optical density was measuredat 450 nmor 490 nm using an ELx808 spectrophotometric reader (Biotek Instruments, Inc., USA). Results were expressed in pg/mL.

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using STATISTICA version 12.5 (Stat Soft STATISTICA™, Poland).

Patient age and lung function data are expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation); cytokine concentrations in BAL supernatant, AL staining results, and cytology data are presented as median, minimum-maximum range, and interquartile range [Q1-Q3] due to the non-parametric distribution of values [

18]. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups (PCS subgroups with each other and with the control group). Correlations between the two random variables were tested using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient r. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Baseline characteristics of patients with PCS are presented in

Table 1.

Patients in the PCS persistence subgroup were more likely to be male and older (statistical trend, p=0.09) than those with PCS remission. COPD was a comorbidity in only a few patients with PCS, but this was due to the exclusion of cigarette smokers from the study; the prevalence of other comorbidities was consistent with the literature [

32].

To date, a significant number of PCS studies have focused on specific groups of COVID-19 patients, most of whom were hospitalised for acute infection, i.e. with severe or critical illness [

2]. As a result, patients with mild/moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection are likely to have been under-represented [

33]. In this study, we proposed a different approach: instead of following selected patients, we looked for PCS in patients diagnosed with suspected ILD.

The significant differences in the predicted values of VC and DLCO are explained by the way the subgroups of patients with PCS were defined.

Baseline data were supplemented with clinical findings known to be risk factors for acute COVID-19, such as C-reactive protein and peripheral blood neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio (

Table 1) [

34].

PCS was characterised by significantly elevated BAL total cell counts, as well as elevated lymphocyte, T, Th, Tc and NK cell counts, and a higher percentage of neutrophils compared to controls. When the neutrophil results were converted to total cell counts, the increase was 17.6 [8.3-41] in PCS vs. 2.6 [1.9-5.4] 103/ml in controls (p<0.001).

The differences between the subgroup with persistent PCS and controls mirrored those between all PCS and controls. Of note, the neutrophil count was 26 [17-36] in PCS persistence vs. 11.2 [5.9-27] in PCS remission, p=0.012, and 2.6 [1.9-5.4] 103/ml vs. controls, p<0.001.

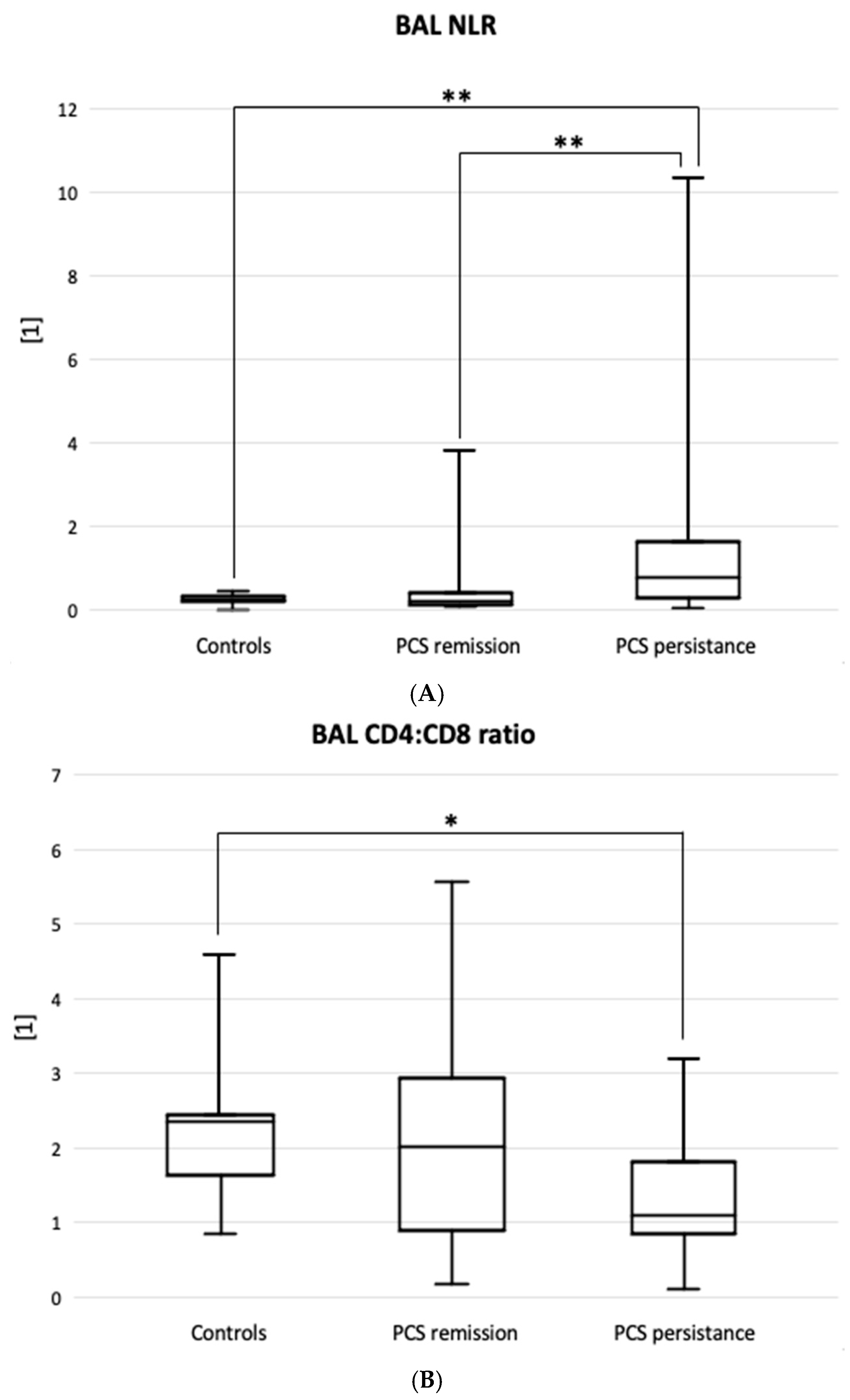

The percentage of BAL lymphocytes was significantly higher in the PCS remission group than in the control group, but not in the PCS resistance group (

Table 2). In summary, the BAL neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio best reflected the difference between the PCS resistance group and the PCS remission group (0.77 [0.26-1.63] vs. 0.23 [0.12-0.40], p<0.01) as well as the controls (vs. 0.21 [0.17-0.31],

Figure 1A).

The BAL CD4:CD8 ratio was significantly lower in patients with PCS resistance than in controls, 1.09 [0.85-1.81] vs. 1.98 [1.65-2.41], p=0.016 (

Figure 1B).

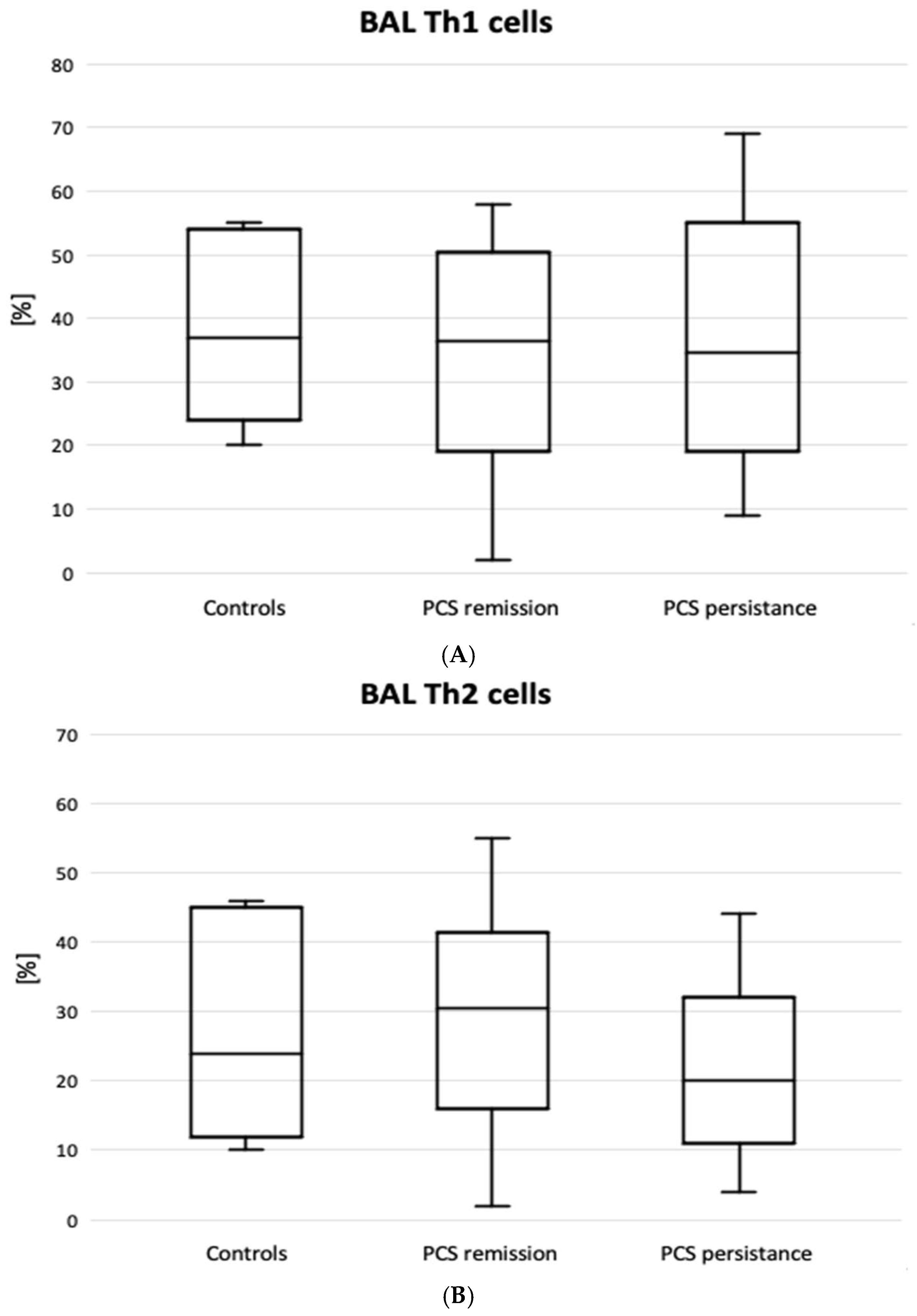

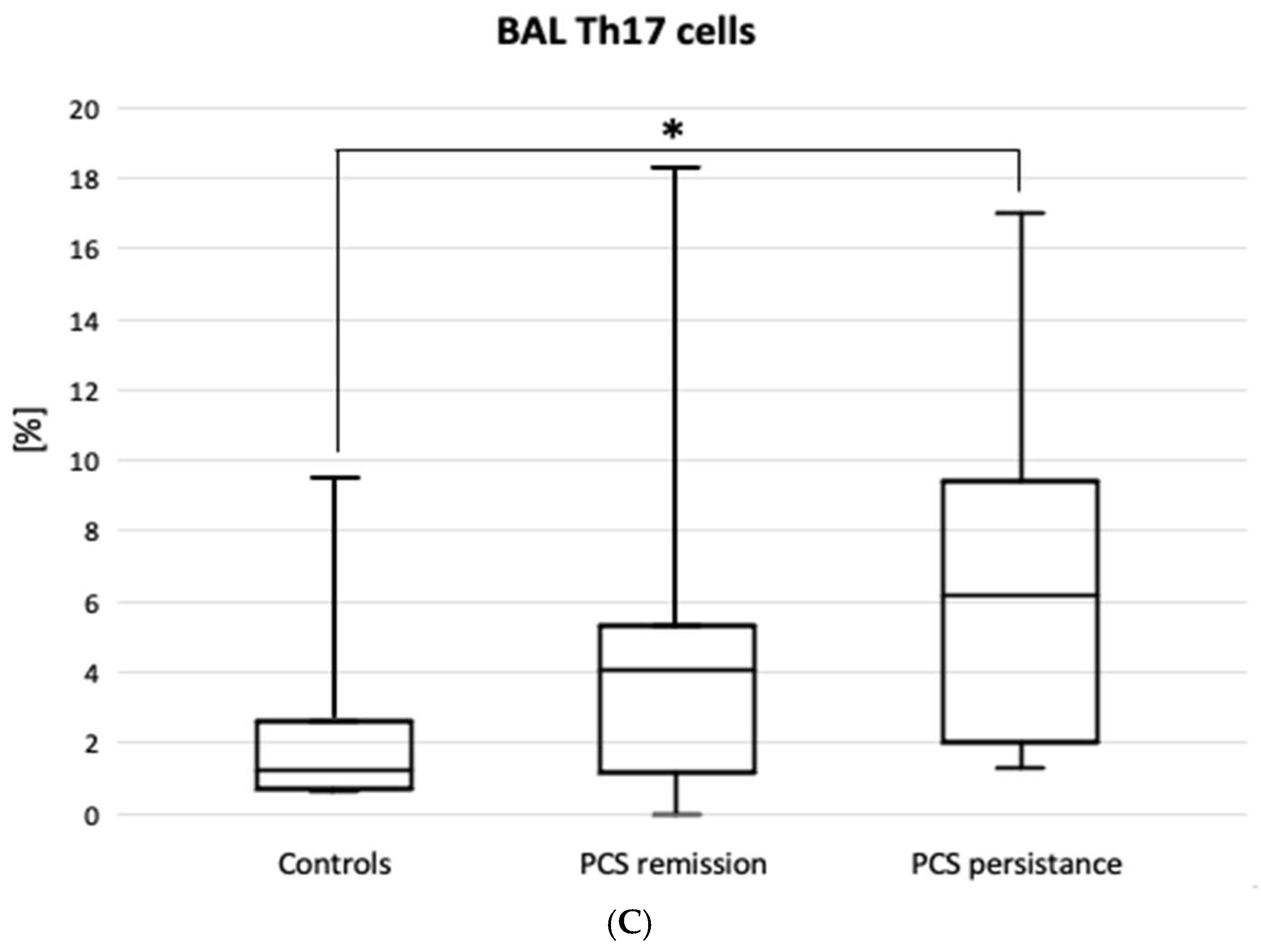

Figure 2 shows the results of lymphocyte typing for Th1, Th2 and Th17. There was an increase in the percentage of Th lymphocytes with Th17 cell-specific markers (CD4+CD183-CD194+) in the PCS persistence group compared to the control group (6.2 [2.0-9.4] vs. 1.2 [0.7-2.7] %, p=0.02). There were no significant differences between the PCS subgroups and the control group in the expression of Th1, Th2 (

Figure 2), PDL1 and CTLA4 markers. However, there was a significantly higher percentage of CD8+PD1+ cells in the BAL of patients with PCS persistence compared to controls (

Table 3).

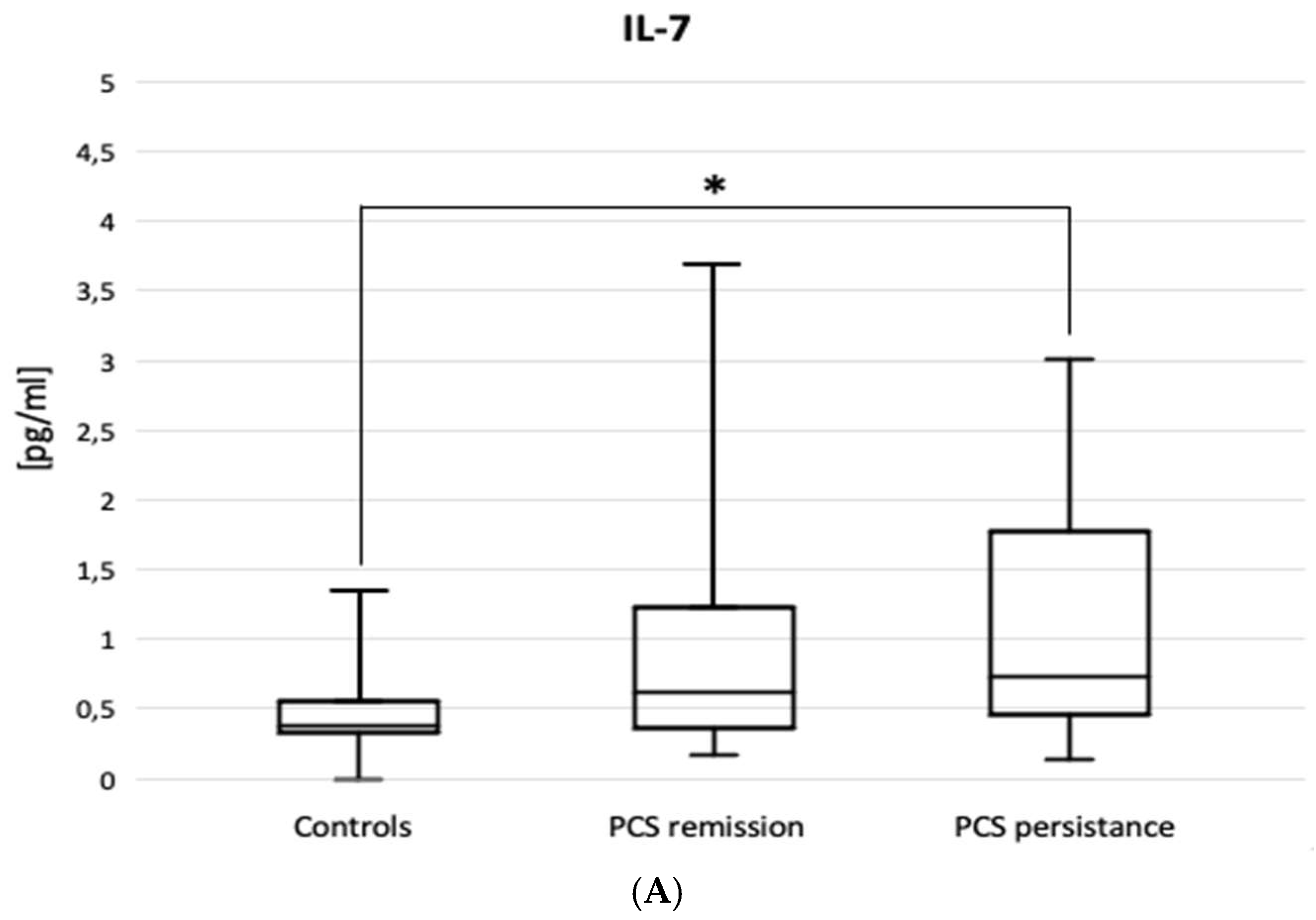

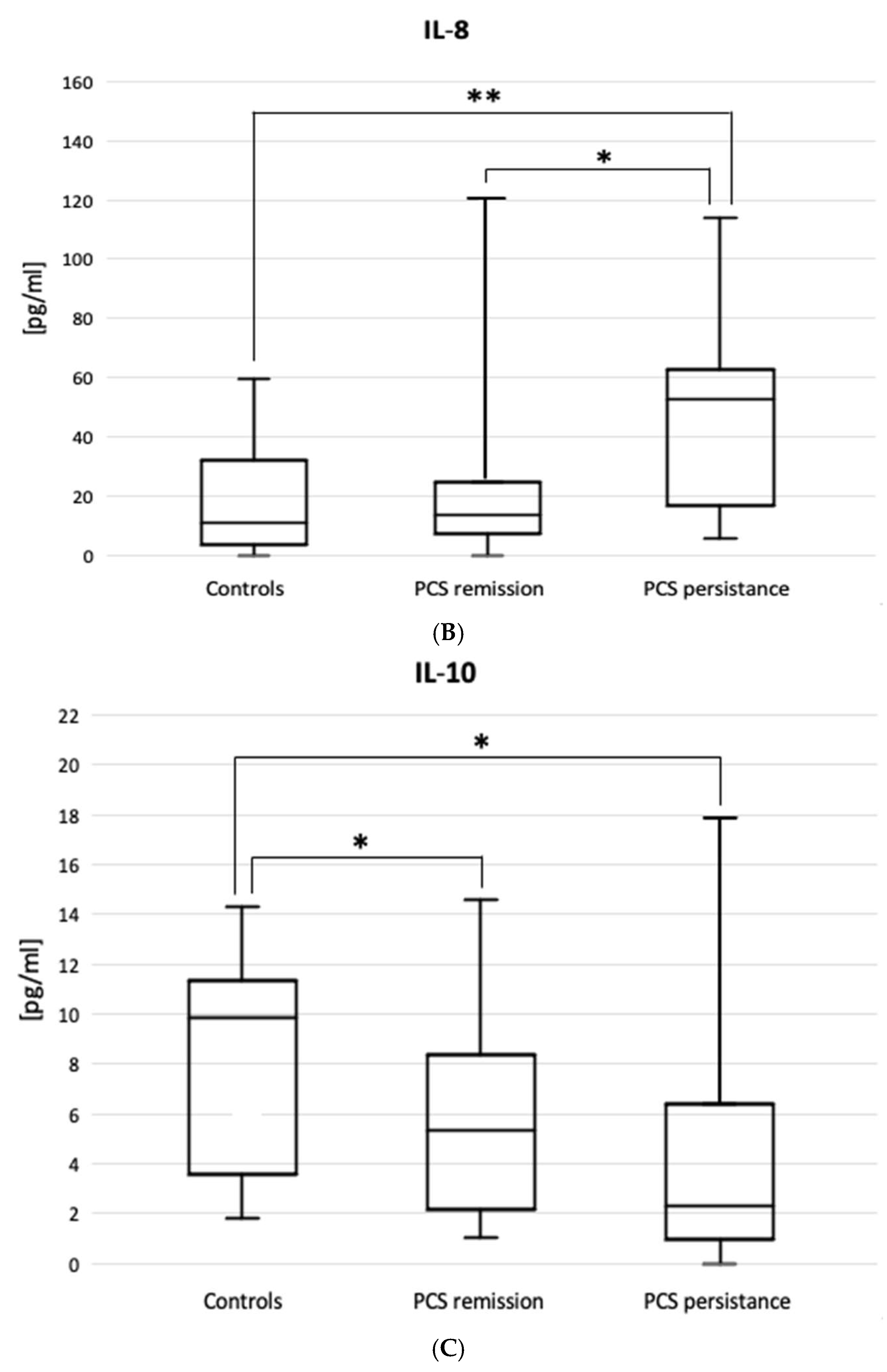

The ELISA results are shown in

Figure 3. Patients with PSC persistence had higher BAL levels of IL-7 (0.70 [0.4-1.71] vs. 0.39 [0.34-0.56] pg/mL, p=0.030) and IL-8 (62.5 [16-243] vs. 10.9 [3.44-32] pg/mL, p=0.002), but lower BAL levels of IL-10 (2.58 [0.97-7.77] vs. 6.62 [1.79-11.3] pg/mL, p=0.034) compared to controls. The figure does not include the results of the IL-5, IL-15, IL-17, IFNγ, TGFβ1 and TNFα ELISAs, as no statistically significant differences were observed between the patient subgroups or between the subgroups and the control group.

The description of the correlations in the study material focused on the relationships associated with VC and DLCO, assuming that these two parameters are particularly important for assessing the prognostic value of BAL examination in PCS.

In patients with PCS persistence, VC was negatively correlated with BAL NLR (r = -0.43, p<0.01) and BAL IL-17 level (r = -0.60, p<0.05), DLCO was negatively correlated with BAL NLR (r = -0.41, p<0.05). In addition, in the total PCS group, VC showed a negative correlation with total BAL NK cell count (r = -0.32, p<0.05) and the percentage of BAL CD8+PD1+ cells (r = -0.60, p<0.01). DLCO was negatively correlated with the percentage of BAL CD8+PD1+ cells (r = -0.41, p<0.05), but positively correlated with the BAL CD4:CD8 ratio (r = +0.36, p<0.05) and the number of weeks since the end of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection (r = +0.67, p<0.05).

4. Discussion

ILD-type lesions have been observed al most since the early sta ges of the COVID-19 pandemic. As early as 2022, based on the data from the pandemic in northern Italy, Besutti et al.presented the results of a 5-7 month follow-up after COVID-19 pneumonia and reported residual non-fibrotic chest abnormalities in 37.5% of patients whilst fibrotic lesions were found in only 4.4% of cases [

27].

In the material presented in this study, up to 57% (33/58) of patients with ILD showed significant improvement and even complete remission. The prognosis for the remaining patients is uncertain, but it is worth noting that according to a meta-analysis by de las Penas et al, only 30% of patients with PCS ILD develop lung lesions after two years of follow-up; these patients also recover gradually [

1]. In addition, it is likely that the prevalence of overall PCS decreased during the last phase of the pandemic and decreased after vaccination [

35].

The risk of fibrotic changes in the lungs of patients following COVID-19 is also low: according to Johnston et al, traction bronchiectases were rarely reported and the presence of honeycombing was incidental (0.2%) [

2]. Furthermore, Robey et al. analyzed a reduction in the incidence of fibrosis from 25 to 7% after a 4 month follow-up [

36]. This trend of improvement is also reflected in the results of the current study: in the total PCS group, the predictive value of DLCO showed a positive correlation with the number of weeks since the onset of acute COVID-19.

In this context, early concerns raised during the early phase of the pandemic – that SARS-CoV-2 infection might cause permanent respiratory disability in a significant proportion of patients after hospital discharge – have not been confirmed [

10].

However, some recovered patients are at risk of developing PCS ILD with pulmonary fibrosis [

37]. During the study, only two cases of progressive pulmonary fibrosis with respiratory failure were observed in our PCS persistence subgroup, both with multiple comorbidities. Thus, there remains a need to identify the subgroup with persistent ILD, to define the immunocytological changes typical of this group, and to monitor them for further development of pulmonary fibrosis [

21].

Patient demographics in the study were consistent with literature data. Known risk factors for persistent ILD after COVID-19 include age, male gender, history of severe/critical acute COVID-19, more than two comorbidities and predicted DLCO less than 80% [

9,

32].

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) has been proposed as a tool to increase the diagnostic sensitivity of COVID-19. BAL is a feasible procedure in confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19, useful in guiding appropriate patient management, and has potential for research [

21].

In this study, we demonstrated an increase in total BAL cells, lymphocytes and neutrophils in PCS patients. BAL neutrophilia was more pronounced in the PCS persistence subgroup, whereas lymphocytosis was more pronounced in the PCS remission subgroup. This translates into differences in the neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio, which was significantly higher in the PCS persistence subgroup than in the PCS remission subgroup and controls.

To date, the BAL immunocytological profile in acute COVID-19 has been better studied. According to Gelarden et al., hospitalized COVID patients showed BAL lymphocytosis (predominance of T cells with variable, usually low CD4:CD8 ratios), the appearance of activated "plasmacytoid" lymphocytes and an increased percentage of neutrophils [

38]. The cited study concluded that a high percentage of BAL lymphocytes supports a worse prognosis in the course of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. On the contrary, Liao et al. pointed out that neutrophilia and depletion of tissue-resident alveolar macrophages were found in severe cases; mild cases were characterized by clonal expansion of CD8+ T cells [

39]. According to Baron et al., BAL neutrophilia is typical of acute COVID; however, their study population limited to patients with critical forms of the disease [

40]. In summary, in the acute form of COVID-19, poor prognosis was associated with BAL neutrophilia and a high BAL NLR [

41].

The current knowledge of ILD in post-COVID syndrome needs to be further expanded. The typical CT findings of NSIP or OP imply BAL neutrophilia and lymphocytosis [

13,

14]. In fact, an increased percentage of neutrophils and/or lymphocytes in the BAL occurs in patients with PCS ILD [

26,

42].

The comprehensive study by Vijayakumar et al. provides additional characterisation of BAL material 3-6 months after discharge. They reported an increase in lymphocytes involving both T and B cells, with cytotoxic T cells associated with epithelial damage and airway disease, while B cells (and proinflammatory myeloid cells) correlated with the extent of lung CT abnormalities. The role of activated T cells (CD69+CD103+), the expression of Th1 cell markers (CXCR3) and the trend towards remission were highlighted [

43].

The results of the present study are partially similar (this is especially true for the increase in the percentage of T-cell-dominant lymphocytes in PCS compared to the control group), although the increase in the percentage of Th1 cells was unchanged and a different activation marker (HLA-DR) for CD3 cells was used. A significant difference was the finding of an increase in the number of BAL neutrophils in the PCS persistence group. This demonstrated the prognostic role of BAL NLR. It should be noted that severe/critical COVID-19 was overrepresented in the cited study [

43].

Although the present study found an increase in the total number of both CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes (with a significant increase in the PCS persistence group for CD8 only), there was a notable trend towards lower CD4:CD8 ratio values in patients with persistent ILD-type lesions. The same observations have been reported in the past in primary NSIP [

44].

The predominance of CD8+PD1+ cells in the PCS persistence subgroup is consistent with the existing literature [

45], but poses challenges with interpretation. On one hand, our results indicate the presence of PCS persistent T cells in the lower airways, characterized by a progressive loss of cytotoxic functions, impaired immune memory and interleukin-10 dependence. On the other hand, these cells showed a significant negative correlation with the predictive values of VC and DLCO, which may indicate a direct involvement in interstitial lung damage. Concentrations of IL-10, the immunosuppressive cytokine [

46], were significantly reduced in the PCS persistence group. In this situation, the hypothesis of local immune dysregulation [

47], whereby the SARS-CoV-2 virus persists in the airways, leading to exhaustion of cytotoxic T cells and a chronic inflammatory response, is plausible [

15]. Another indirect evidence of immune dysregulation in a group of patients with persistent ILD is the increase in IL-7, an immune memory cytokine, highlighted in this study [

46].

Notably, the vitro IL-10 blockade, which overrides the PD1 inhibitory signalling, can reverse T-cell exhaustion [

45].

Another key finding of the present study was the demonstration of a significant increase in the percentage of cells with a Th17 helper lymphocyte phenotype. Together with Th1 cells, they are involved in the pathogenesis of acute COVID-19 [

48]. Our findings, which also point to their involvement in PCS persistence, establish a pathophysiological chain linking Th17 lymphocytes, the IL-17 they release, the interleukin-8 dependent on the latter, and activated neutrophils.

To elaborate on this idea, Th17-driven interleukin-17 is a recognised factor of lung lesions in COVID-19, acting as a neutrophilic pro-inflammatory cytokine [

46]. Our results show no remarkable increase of IL-17 in PCS compared to controls, but there are significant correlations between IL-17 levels and the predictive values of VC and DLCO in patients, which may indicate the involvement of IL-17 in interstitial lung injury.

IL-8 recruits and activates neutrophils to the site of infection, and increased IL-8 levels are associated with COVID-19 severity and ARDS [

46]. IL-8 secretion is indirectly dependent on IL-17 [

49].

Activation of neutrophils in COVID-19 is a negative phenomenon [

5]; neutrophils in ILD are the cells of aggressive inflammatory reaction (via free radicals, metalloproteinases and through NETosis) [

18]. In addition, neutrophils can express PDL1 and induce apoptosis of PD1+ T cells in COVID-19 [

50].

The results of other ELISA tests, including the examination of IFNγ, TNFα and IL-5 concentrations (no significant differences between patients and controls) are consistent with the literature [

51,

52,

53].

5. Conclusions

The immunocytological profile of BAL in Post-COVID-19 (PCS) is characterized by elevated total cell counts, increased counts and percentages of lymphocytes and neutrophils and high BAL neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio, NLR).

A worse prognosis in PCS is associated with higher BAL NLR, higher BAL neutrophil count and percentage, elevated percentage of CD8+PD1+ lymphocytes, and a reduced CD4:CD8 ratio.

Th17 cells and IL-8 participate in lung PCS persistence.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This work was supported by the grant from the Collegium Medicum, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Bydgoszcz (MN-4/2022/ZES to M.G.). The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author’s Contribution

PK designed the study, performed flow cytometry examination, interpreted the results, drafted and revised the manuscript, 15%. JDM performed lab experiments and clinical examinations, acquired and analysed data, drafted and revised the manuscript, 50%. GP designed clinical examinations, interpreted clinical data, revised the manuscript, 5%. EW designed and performed lab experiments, 5%. MS performed ELISA assays, 5%. EW2 analysed data, prepared the study figures 5. KS acquired and analysed clinical and laboratory data, 5%. TS acquired and analysed clinical data, 5%. MG designed the study, critically revised the manuscript, 5%. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CD, cluster of differentiation; CCL, C-C motif chemokine ligand; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CTLA4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated antygen 4; CXCL, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; CXCR, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; ICP, immune checkpoints; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; ILD, interstitial lung disease(s); MERS, middle east respiratory syndrome; NK, natural killer; NLR, neutrophillymhocyte ratio; PCS, post-COVID-19 sydrome; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; PDL1 (2), programmed cell death protein ligand 1 (2); SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2; TGF, transforming growth factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

References

- Fernandez-de-Las-Peñas C, Notarte KI, Macasaet R, Velasco JV, Catahay JA, Ver AT, Chung W, Valera-Calero JA, Navarro-Santana M. Persistence of post-COVID symptoms in the general population two years after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2024;88(2):77-88. [CrossRef]

- Johnston J, Dorrian D, Linden D, Stanel SC, Rivera-Ortega P, Chaudhuri N. Pulmonary Sequelae of COVID-19: Focus on Interstitial Lung Disease. Cells 2023;12(18):2238. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, Shi X, Fritsche LG, Mukherjee B. Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(9):1593-1607. [CrossRef]

- Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV. WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(4):e102-e107. [CrossRef]

- Mohandas S, Jagannathan P, Henrich TJ, Sherif ZA, Bime C, Quinlan E, Portman MA, Gennaro M, Rehman J. RECOVER Mechanistic Pathways Task Force. Immune mechanisms underlying COVID-19 pathology and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). eLife. 2023;12:e86014. [CrossRef]

- Zhang P, Li J, Liu H, Han N, Ju J, Kou Y, Chen L, Jiang M, Pan F, Zheng Y. Long-Term Bone and Lung Consequences Associated with Hospital-Acquired Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome: A 15-Year Follow-up from a Prospective Cohort Study. Bone Res. 2020;8:8. doi: 10.1038/s41413-020-0084-5.

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(3):133-146. Erratum in: Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(6):408. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00896-0. [CrossRef]

- Sideratou CM, Papaneophytou C. Persisting Shadows: Unraveling the Impact of Long COVID-19 on Respiratory, Cardiovascular, and Nervous Systems. Infect Dis Rep. 2023;15(6):806-830. [CrossRef]

- Batiha GE, Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Welson NN. Pathophysiology of Post-COVID syndromes: a new perspective. Virol J. 2022;19(1):158. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Castro R, Vasconcello-Castillo L, Alsina-Restoy X, Solis-Navarro L, Burgos F, Puppo H, Vilaró J. Respiratory function in patients post-infection by COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulmonology. 2021;27(4):328-337. [CrossRef]

- Myall KJ, Mukherjee B, Castanheira AM, Lam JL, Benedetti G, Mak SM, Preston R, Thillai M, Dewar A, Molyneaux PL, West AG. Persistent Post-COVID-19 Interstitial Lung Disease. An Observational Study of Corticosteroid Treatment. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(5):799-806. [CrossRef]

- Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Riches DW, Moss M, Downey GP. The fibroproliferative response in acute respiratory distress syndrome: mechanisms and clinical significance. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(1):276-85. [CrossRef]

- Davidson KR, Ha DM, Schwarz MI, Chan ED. Bronchoalveolar lavage as a diagnostic procedure: a review of known cellular and molecular findings in various lung diseases. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(9):4991-5019. [CrossRef]

- Meyer KC, Raghu G, Baughman RP, Brown KK, Costabel U, du Bois RM, Drent M, Haslam PL, Kim DS, Nagai S, Rottoli P, Saltini C, Selman M, Strange C, and Wood b, on behalf of the American Thoracic Society Committee on BAL in Interstitial Lung Disease. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline: The Clinical Utility of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Cellular Analysis in Interstitial Lung Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185(9):1004–1014.

- Peluso MJ, Lu S, Tang AF, Durstenfeld MS, Ho HE, Goldberg SA, Forman CA, Munter SE, Hoh R, Tai V, Chenna A, Yee BC, Winslow JW, Petropoulos CJ, Greenhouse B, Hunt PW, Hsue PY, Martin JN, Daniel Kelly J, Glidden DV, Deeks SG, Henrich TJ. Markers of Immune Activation and Inflammation in Individuals With Postacute Sequelae of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(11):1839-1848. [CrossRef]

- Gagiannis D, Hackenbroch C, Bloch W, Zech F, Kirchhoff F, Djudjaj S, von Stillfried S, Bülow R, Boor P, Steinestel K. Clinical, Imaging, and Histopathological Features of Pulmonary Sequelae after Mild COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208(5):618-621. [CrossRef]

- Bertoletti A, Le Bert N, Tan AT. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in the changing landscape of the COVID-19 pandemic. Immunity. 2022;55(10):1764-1778. [CrossRef]

- Kopiński P, Wypasek E, Senderek T, Wędrowska E, Wandtke T, Przybylski G. Different expression of immune checkpoint markers on bronchoalveolar lavage CD4+ cells: a comparison between hypersensitivity pneumonitis and sarcoidosis. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2021;131(11):16084. [CrossRef]

- Chiappelli F, Fotovat L. Post acute CoViD-19 syndrome (PACS) - Long CoViD. Bioinformation. 2022;18(10):908-911. [CrossRef]

- Shafqat A, Omer MH, Albalkhi I, Alabdul Razzak G, Abdulkader H, Abdul Rab S, Sabbah BN, Alkattan K, Yaqinuddin A. Neutrophil extracellular traps and long COVID. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1254310. [CrossRef]

- Tomassetti S, Ciani L, Luzzi V, Gori L, Trigiani M, Giuntoli L, Lavorini F, Poletti V, Ravaglia C, Torrego A, Maldonado F, Lentz R, Annunziato F, Maggi L, Rossolini GM, Pollini S, Para O, Ciurleo G, Casini A, Rasero L, Bartoloni A, Spinicci M, Munavvar M, Gasparini S, Comin C, Cerinic MM, Peired A, Henket M, Ernst B, Louis R, Corhay JL, Nardi C, Guiot J. Utility of bronchoalveolar lavage for COVID-19: a perspective from the Dragon consortium. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1259570. [CrossRef]

- Lee J.H., Yim J.-J., Park J. Pulmonary Function and Chest Computed Tomography Abnormalities 6–12 Months after Recovery from COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Respir. Res. 2022;23:233. doi: 10.1186/s12931-022-02163-x.

- Kopiński P, Wandtke T, Dyczek A, Wędrowska E, Roży A, Senderek T, Przybylski G, Chorostowska-Wynimko J. Increased levels of interleukin 27 in patients with early clinical stages of non-small cell lung cancer. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2018;128(2):105-114. [CrossRef]

- Bankier AA, MacMahon H, Colby T, Gevenois PA, Goo JM, Leung ANC, Lynch DA, Schaefer-Prokop CM, Tomiyama N, Travis WD, Verschakelen JA, White CS, Naidich DP. Fleischner Society: Glossary of Terms for Thoracic Imaging. Radiology. 2024;310(2):e232558. [CrossRef]

- Mehta P, Rosas IO, Singer M. Understanding Post-COVID-19 Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD): A New Fibroinflammatory Disease Entity. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48:1803–1806. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06877-w.

- Vijayakumar B, Tonkin J, Devaraj A, Philip KEJ, Orton CM, Desai SR, Shah PL. CT Lung Abnormalities after COVID-19 at 3 Months and 1 Year after Hospital Discharge. Radiology. 2022;303(2):444-454. [CrossRef]

- Besutti G, Giorgi Rossi P, Iotti V, Spaggiari L, Bonacini R, Nitrosi A, Ottone M, Bonelli E, Fasano T, Canovi S, Colla R, Massari M, Lattuada IM, Trabucco L, Pattacini P; Reggio Emilia COVID-19 Working Group. Accuracy of CT in a cohort of symptomatic patients with suspected COVID-19 pneumonia during the outbreak peak in Italy. Eur Radiol. 2020 Dec;30(12):6818-6827. [CrossRef]

- Han X, Fan Y, Alwalid O, Li N, Jia X, Yuan M, Li Y, Cao Y, Gu J, Wu H, Shi H. Six-month follow- up chest CT findings after severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiology. 2021;299(1):E177–E186. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203153.

- Wu X, Liu X, Zhou Y, Yu H, Li R, Zhan Q, Ni F, Fang S, Lu Y, Ding X, Liu H, Ewing RM, Jones MG, Hu Y, Nie H, Wang Y. 3-Month, 6-Month, 9-Month, and 12-Month Respiratory Outcomes in Patients Following COVID-19-Related Hospitalisation: A Prospective Study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021;9:747–754. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00174-0.

- Botafogo V, Pérez-Andres M, Jara-Acevedo M, Bárcena P, Grigore G, Hernández-Delgado A, Damasceno D, Comans S, Blanco E, Romero A, Arriba-Méndez S, Gastaca-Abasolo I, Pedreira CE, van Gaans-van den Brink JAM, Corbiere V, Mascart F, van Els CACM, Barkoff AM, Mayado A, van Dongen JJM, Almeida J, Orfao A. Age Distribution of Multiple Functionally Relevant Subsets of CD4+ T Cells in Human Blood Using a Standardized and Validated 14-Color EuroFlow Immune Monitoring Tube. Front Immunol. 2020;27(11):166. [CrossRef]

- Zheng M, Gao Y, Wang G, Song G, Liu S, Sun D, Xu Y, Tian Z. Functional exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(5):533-535. [CrossRef]

- Fesu D, Polivka L, Barczi E, Foldesi M, Horvath G, Hidvegi E, Bohacs A, Muller V. Post-COVID interstitial lung disease in symptomatic patients after COVID-19 disease. Inflammopharmacology. 2023;31(2):565-571. [CrossRef]

- González J, Benítez ID, Carmona P, Santisteve S, Monge A, Moncusí-Moix A, Gort-Paniello C, Pinilla L, Carratalá A, Zuil M, Ferrer R, Ceccato A, Fernández L, Motos A, Riera J, Menéndez R, Garcia-Gasulla D, Peñuelas O, Bermejo-Martin JF, Labarca G, Caballero J, Torres G, de Gonzalo-Calvo D, Torres A, Barbé F; CIBERESUCICOVID Project (COV20/00110, ISCIII). Pulmonary Function and Radiologic Features in Survivors of Critical COVID-19: A 3-Month Prospective Cohort. Chest. 2021;160(1):187-198. [CrossRef]

- Lagunas-Rangel FA. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-to-C-reactive protein ratio in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):1733-1734. [CrossRef]

- Hallek M, Adorjan K, Behrends U, Ertl G, Suttorp N, Lehmann C. Post-COVID Syndrome. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2023;27;120(4):48-55. [CrossRef]

- Robey RC, Kemp K, Hayton P, Mudawi D, Wang R, Greaves M, Yioe V, Rivera-Ortega P, Avram C, Chaudhuri N. Pulmonary Sequelae at 4 Months After COVID-19 Infection: A Single-Centre Experience of a COVID Follow-Up Service. Adv Ther. 2021;38(8):4505-4519. [CrossRef]

- Mylvaganam RJ, Bailey JI, Sznajder JI, Sala MA. Northwestern Comprehensive COVID Center Consortium. Recovering from a pandemic: pulmonary fibrosis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur Respir Rev. 2021;30:210194. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0194-2021.

- Gelarden I, Nguyen J, Gao J, Chen Q, Morales-Nebreda L, Wunderink R, Li L, Chmiel JS, Hrisinko M, Marszalek L, Momnani S, Patel P, Sumugod R, Chao Q, Jennings LJ, Zembower TR, Ji P, Chen YH. Comprehensive evaluation of bronchoalveolar lavage from patients with severe COVID-19 and correlation with clinical outcomes. Hum Pathol. 2021;113:92-103. [CrossRef]

- Liao M, Liu Y, Yuan J, Wen Y, Xu G, Zhao J, Cheng L, Li J, Wang X, Wang F, Liu L, Amit I, Zhang S, Zhang Z. Single-Cell Landscape of Bronchoalveolar Immune Cells in Patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:842–844. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0901-9.

- Baron A, Hachem M, Tran Van Nhieu J, Botterel F, Fourati S, Carteaux G, De Prost N, Maitre B, Mekontso-Dessap A, Schlemmer F. Bronchoalveolar Lavage in Patients with COVID-19 with Invasive Mechanical Ventilation for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(4):723-726. [CrossRef]

- Voiriot G, Dorgham K, Bachelot G, Fajac A, Morand-Joubert L, Parizot C, Gerotziafas G, Farabos D, Trugnan G, Eguether T, Blayau C, Djibré M, Elabbadi A, Gibelin A, Labbé V, Parrot A, Turpin M, Cadranel J, Gorochov G, Fartoukh M, Lamazière A. Identification of bronchoalveolar and blood immune-inflammatory biomarker signature associated with poor 28-day outcome in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):9502. [CrossRef]

- Cheon IS, Son YM, Sun J. Tissue-resident memory T cells and lung immunopathology. Immunol Rev. 2023;316(1):63-83. [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar B, Boustani K, Ogger PP, Papadaki A, Tonkin J, Orton CM, Ghai P, Suveizdyte K, Hewitt RJ, Desai SR, Devaraj A, Snelgrove RJ, Molyneaux PL, Garner JL, Peters JE, Shah PL, Lloyd CM, Harker JA. Immuno-proteomic profiling reveals aberrant immune cell regulation in the airways of individuals with ongoing post-COVID-19 respiratory disease. Immunity. 2022;55(3):542-556.e5. [CrossRef]

- Nagai S, Kitaichi M, Itoh H, Nishimura K, Izumi T, Colby TV. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia/fibrosis: comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and BOOP. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(5):1010-9. Erratum in: Eur Respir J 1999;13(3):711. [CrossRef]

- Chiappelli F, Fotovat L. Virus interference in CoViD-19. Bioinformation. 2022;30;18(9):768-773. [CrossRef]

- Hsu RJ, Yu WC, Peng GR, Ye CH, Hu S, Chong PCT, Yap KY, Lee JYC, Lin WC, Yu SH. The Role of Cytokines and Chemokines in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infections. Front Immunol. 2022;13:832394. [CrossRef]

- Opsteen S, Files JK, Fram T, Erdmann N. The role of immune activation and antigen persistence in acute and long COVID. J Investig Med. 2023;71(5):545-562. [CrossRef]

- Toor SM, Saleh R, Sasidharan Nair V, Taha RZ, Elkord E. T-cell responses and therapies against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Immunology. 2021;162(1):30-43. [CrossRef]

- Resende GG, da Cruz Lage R, Lobe SQ, Medeiros AF, Costa e Silva AD, Tolentino Nogueira Sá A, de Assis Oliveira AJ, Sousa D, Cerqueira Guimarães H, Coelho Gomes I, Souza RP, Santana Aguiar R, Tunala R, Forestiero F, Souza Bueno Filho JS, Teixeira MM. Blockade of Interleukin Seventeen (Il-17a) With Secukinumab in Hospitalized Covid-19 Patients – The Bishop Study. medRxiv 2021;07.21.21260963. [CrossRef]

- Hirata T, Osuga Y, Hamasaki K, Yoshino O, Ito M, Hasegawa A, Takemura Y, Hirota Y, Nose E, Morimoto C, Harada M, Koga K, Tajima T, Saito S, Yano T, Taketani Y. Interleukin (IL)-17A stimulates IL-8 secretion, cyclooxygensase-2 expression, and cell proliferation of endometriotic stromal cells. Endocrinology. 2008;149(3):1260-7. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald L, Alivernini S, Tolusso B, Elmesmari A, Somma D, Perniola S, Paglionico A, Petricca L, Bosello SL, Carfì A, Sali M, Stigliano E, Cingolani A, Murri R, Arena V, Fantoni M, Antonelli M, Landi F, Franceschi F, Sanguinetti M, McInnes IB, McSharry C, Gasbarrini A, Otto TD, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Gremese E. COVID-19 and RA share an SPP1 myeloid pathway that drives PD-L1+ neutrophils and CD14+ monocytes. JCI Insight. 2021;6(13):e147413. [CrossRef]

- Oatis D, Herman H, Balta C, Ciceu A, Simon-Repolski E, Mihu AG, Lepre CC, Russo M, Trotta MC, Gravina AG, D'Amico M, Hermenean A. Dynamic shifts in lung cytokine patterns in post-COVID-19 interstitial lung disease patients: a pilot study. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2024;15:20406223241236257. [CrossRef]

- Islam MA, Getz M, Macklin P, Versypt ANF. An agent-based modeling approach for lung fibrosis in response to COVID-19. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023:2022.10.03.510677. Update in: PLoS Comput Biol. 2023;19(12):e1011741. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011741. [CrossRef]

- Fleischer M, Szepanowski F, Mausberg AK, Asan L, Uslar E, Zwanziger D, Volbracht L, Stettner M, Kleinschnitz C. Cytokines (IL1β, IL6, TNFα) and serum cortisol levels may not constitute reliable biomarkers to identify individuals with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2024;17:17562864241229567. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).