1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women globally[

1]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is the most aggressive subtype of breast cancer. It is highly heterogeneous, lacks canonical biomarkers, and is often associated with treatment resistance, which leads to worse oncologic outcomes compared to other breast cancer subtypes[

2,

3]. Radiotherapy (RT) is a key modality for local and/or regional control at the primary tumor or metastatic disease sites in breast cancer[

4,

5,

6]. However, resistance to RT is commonly observed in TNBC[

7], leading to poor clinical outcomes[

8,

9,

10]. Although the molecular mechanisms driving radioresistance in TNBC are not fully understood, recent studies point to DNA repair[

11] pathways, cell cycle redistribution[

12], epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)[

13], and the tumor microenvironment[

14] as potential contributors. Gaining deeper insights into these underlying molecular mechanisms may facilitate the identification of predictive biomarkers for RT response, paving the way for more effective and personalized treatment strategies for TNBC patients.

RT induces genotoxicity by generating DNA double-stranded breaks (DDSBs)[

15], which are repaired primarily through homologous recombination (HR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathways[

15]. Cancer cells exploit these repair mechanisms to evade genotoxic effects induced by RT, often leading to resistance[

16]. Studies have demonstrated that targeting DNA repair pathway components is a promising strategy for sensitizing breast cancer cells to RT[

17,

18]. NHEJ is commonly activated in TNBC[

19] and hence, disrupting this pathway could enhance TNBC cell sensitivity to RT. Several components of the NHEJ repair pathway such as the protein kinase DNA-Pkc, have been tested in pre-clinical models[

20] but have shown increased toxicity and poor pharmacokinetics[

21]. This suggests the need to identify novel targets that are specifically upregulated in TNBC tumors to enhance radiotherapy response.

Artemis is an endonuclease, encoded by

DNA Crosslink Repair 1C (

DCLRE1C), required for processing DNA ends, during V(D)J recombination[

22] and NHEJ-mediated repair of RT-induced DDSBs[

23]. Deficiency in Artemis has been linked to severe combined immunodeficiency with sensitivity to RT (RS-SCID) due to impaired VDJ recombination[

24,

25]. Exon sequencing of breast cancer patients with familial BRCA1/2 mutation identified nonsense mutations in

DCLRE1C gene[

26], suggesting its role in breast cancer. However, the role of Artemis in breast cancer pathogenesis and therapy resistance, particularly in TNBC, is poorly understood.

In the current study, we employed a genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screen to investigate the mechanisms of radioresistance in MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells. Our screen identified Artemis as a potential radiosensitizing target. Our findings demonstrated that the loss of function of Artemis lead to a decrease in cell proliferation and enhanced anti-cancer effects of RT in TNBC cells both

in vitro and

in vivo. Furthermore, we found that targeting Artemis activity with non-oncology drugs such as ceftriaxone and auranofin, inhibitor of Artemis’ endonuclease activity in cell free assays,[

27] significantly enhanced RT response in TNBC cells. RNA-seq analysis revealed that loss of Artemis resulted in the perturbation of genes related to cellular senescence that may potentially enhance RT. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that Artemis plays a significant role in TNBC proliferation and survival following RT. Therefore, these results indicate Artemis as a predictive biomarker and therapeutic target for enhancing radiosensitivity in TNBC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture Reagents

The MDA-MB-231 cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and the SUM159 cell line was obtained from Asterand Inc. (Detroit, MI, USA). MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM)/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). SUM159 cells were cultured in HAM/F-12 + 5% FBS, 1% HEPES, 0.5% insulin and 0.1% hydrocortisone. MDA-MB-231 (ExPASy Callisaurus Research Resource Identifier RRID:CVCL_0062) and SUM159 (RRID: CVCL_5423) were authenticated via third-party testing on 04/2024 (IDEXX BioAnalytic, Columbia MO, USA) using short tandem repeat profiling (using 9 markers) and were regularly tested to confirm mycoplasma negativity. The lenti-Cas9-blast transduced MDA-MB-231 cell line used for the CRISPR screen was obtained from the laboratory of Dr. DW Cescon[

28]. The HEK-293T cells used for producing lentiviral particles were obtained from ATCC, Manassas, VA.

2.2. Genome-Wide CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout Screening

Lentiviral particles encoding the genome-wide Moffat Toronto Knockout (TKO)-v2 pooled library[

29] was generated by co-transfecting pooled TKO-v2 plasmid with psPAX2 (Addgene #12260) and pMD2.G (Addgene #12259) into HEK-293T cells using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (ThermoFisher, Massachusetts, USA). MDA-MB-231-Cas9 cells were transduced with the TKO-v2 library at an MOI of ~0.3 using 8µg/mL polybrene. The infection was performed at a low multiplicity of infections to ensure most of the cells were infected with a single sgRNA. Library transduced MDA-MB-23-Cas9 cells were selected with puromycin for 7 days (Supplementary

Figure 1A) to generate a knockout cell pool. The pools were expanded and treated with 0 Gy or 4 Gy radiation using the XRAD 225Cx (Precision) micro-IGRT delivery system. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from cells at day 0 and the surviving cells on Day 25 for both 0 Gy and 4 Gy treated conditions and subjected to sgRNA-targeted sequencing at the Princess Margaret Genome Centre (Toronto). Screens were performed with technical duplicates maintaining 200X library coverage. sgRNA abundance between treatment conditions was statistically compared using the MAGeCK algorithm (v0.5.723) to identify screen hits, defined as genes targeted by sgRNA that were significantly depleted in the irradiated compared to non-irradiated condition.

2.3. CRISPR/Cas9 Artemis-Specific Knockout

MDA-MB-231 cells were used to generate the Artemis knockout lines. Four different sgRNA sequences (Supplementary Table 1A) targeting Artemis (DCLRE1C) were selected from the TKO-v2 sgRNA library, and a scrambled sgRNA was used as a control. For each sgRNA, oligos were annealed and individually inserted into the LentiCRISPRv2 lentiviral vector (Addgene, Massachusetts, USA, #52691). Lentivirus was made as described. Viral particles (sgControl, sgDCLRE1C #1, #2, #3 and #4) were transduced into MDA-MB-231 cells using 8µg/mL polybrene. After 24 hours, cells were selected using 2µg/mL puromycin for 48 hours. All the knockout lines were confirmed to be negative for mycoplasma.

2.4. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Data Analysis

Clinical data from TCGA was analyzed using the University of ALabama at Birmingham CANcer (UALCAN) (

https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html) interactive web resource[

30,

31]. Expression of genes in breast cancer patients was analyzed using the TCGA breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA) data set. Survival analysis of TNBC patients with high and low

DCLRE1C expression through median was performed using the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA2) web-based tool (

http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#survival). The BRCA data set, with basal-like/triple-negative subtype filter, was used to generate a survival plot.

2.5. Colony-Forming Assay

Colony formation assays were performed as previously described[

32,

33,

34]. Parental and CRISPR-knockout MDA-MB-231 and parental SUM159 TNBC cells were plated singly at a density of ~20 cells/cm

2 of 9.6cm

2 cell culture dish. The following day (16-20 hours after seeding), the cells were exposed to an ID50 dose of radiation (2 Gy for MDA-MB-231 and 5 Gy for SUM159)[

32,

35] using a Cobalt-60 irradiator at the Verspeeten Family Cancer Centre (London, ON). Immediately after irradiation, cells were replenished with media containing either DMSO (0.1%; equivalent to the highest dose of the drug) or varying concentrations (0.01µM, 0.1µM, 1µM, 10µM and 100µM) of ceftriaxone (Cat. No. C5793, Millipore Sigma, Germany), auranofin (Cat. No. A6733, Millipore Sigma, Germany) and ampicillin (Cat. No. BP1760-5, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, USA).

2.6. In Vivo Studies

Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the Canadian Council for Animal Care under a protocol approved by the University of Western Ontario Animal Care Committee (#2022-43). MDA-MB-231 sgControl and sgDCLRE1C_#2 lines were exposed to either 2 Gy or no radiation (0 Gy). Subsequently, the cells were trypsinized and viability was assessed using trypan blue. Cells were then resuspended in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) at a concentration of 1 x 107 viable cells/mL. Cell suspensions (100 µL; 1 x106 cells/mouse) were injected into the mammary fat pad (m.f.p) of 6–8-week-old female NOD/SCID mice (n=5 mice/group). The size of the primary tumor was assessed weekly for 6 months using a digital caliper measurement in 2 perpendicular dimensions and tumor volume was calculated using the formula: volume = 0.52 x (width)2 x (length). Mice were sacrificed once the tumor volume reached 1500 mm3.

2.7. Immunoblotting

MDA-MB-231 sgControl and sgDCLRE1C (#1 - #4) cell lines were lysed using 1X RIPA lysis buffer (Cat. No. 89900, Thermo Scientific, USA) containing 1X protease inhibitor (Cat. No. 78430, Thermo Scientific) and 1X phosphatase inhibitor (Cat. No.1862495, Thermo Scientific). Protein (30 µg per sample; quantified by Lowry assay) was boiled for 5 minutes in 1X gel loading buffer. The samples were then subjected to sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (PVDF, Cat. No. 88518, Thermo Scientific). Membranes were blocked using either 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) or 5% skimmed milk powder (Supplementary Table 1) in Tris-buffer saline + 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature prior to incubation with primary antibody (Supplementary Table 1) diluted in 5% blocking solution for overnight at 4° Celsius. Blots were then incubated with secondary antibody (Supplementary Table 1B) conjugated to horse radish peroxidase (HRP) for 1 hour at room temperature. The Amersham ECL Primer Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, WI, USA) was used to measure protein expression by visualizing chemiluminescence using the BioRad ChemiDoc™ MP imaging system. The blot was stripped using a stripping buffer (1.5% glycine, 0.1% SDS, 1% tween-20) and incubated with anti-Actin-HRP conjugated antibody (1:25,000, Cat. No. ab49900, Abcam, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature and protein expression was measured as described above. The densitometric analysis was performed using Image Lab software (v6.1, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

2.8. Cell Cycle Analysis

The sgControl and sgDCLRE1C#2 MDA-MB-231 cells were plated a ~7250 cells/cm2 of a 55cm2 cell culture dish. The following day (16-20 hours after seeding), the cells were exposed to either 0 Gy or 2 Gy dose of RT. The media was replenished immediately after irradiation and cells were cultured for 24-hours. Cells were trypsinized, washed and centrifuged at 1000g for 5 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in 0.4 ml of 1X PBS and 1 ml of pre-chilled 100% ethanol was added dropwise to the cell suspension with gentle vortexing. Cells were then centrifuged at 200g for 3 minutes at 4° C and washed twice with 1X PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in PBS containing 100µg/ml RNase A and 50µg/ml propidium iodide and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. Cell cycle data was acquired using were then analyzed using a Beckman Coulter FC500 flow cytometer. The data was analyzed using FlowJo software (v10.6.2).

2.9. Galactosidase Staining

Control and Artemis knockout MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at a density of ~5000 cells per/cm2 of a 9.6cm2 cell culture dish. The following day (16-20 hours after seeding), the cells were exposed to either 0 Gy or 2 Gy dose of RT. Immediately after irradiation, cells were replenished with media and incubated for 72 hours. The senescence β-galactosidase staining kit (Cell Signaling, Cat. No. 9860) was used to characterize senescent cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The stained cells were imaged using an Olympus CKX53 microscope and β-galactosidase positive cells were counted using ImageJ software.

2.10. RNA-Seq Analysis

MDA-MB-231 sgControl and sgDCLRE1C#2 cell lines were exposed to either 0 Gy or 2 Gy radiation (previously determined ID50 dose)[

32,

35]. Immediately after irradiation, the growth medium was refreshed. Total RNA was harvested 72 hours post-irradiation using TRIzol

® (Cat. No. 15596-026, Thermo Scientific) reagent as per the manufacturer’s instruction and quantity and quality measurements were performed using NanoDrop One (Thermo Scientific). Samples were analyzed in the London Regional Genomics Centre (LRGC) for quality assessment using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, rRNA reduction and creation of indexed libraries. RNA sequencing was performed using an Illumina NextSeq High 75 cycle Sequencing Kit and RNA-seq analysis was performed using R software. Raw counts were imported into the R statistical environment (version 4.4.1). The DESeq2 (version 1.44)[

36] package was used for differential gene expression analysis. Independent filtering to remove genes with low counts were carried out as per the DESeq2 default protocol. The Benjamin-Hochberg method was used to adjust the p value for multiple testing, and a threshold of 0.05 was used for FDR. A PCA plot was generated using the 500 genes with the greatest variance in expression as input after normalizing the expression counts through variance stabilizing transformation (VST). Volcano plots were generated using ggplot2 (v.3.5.1) and ggrepel (v.0.9.5) packages. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were visualized in a volcano plot using the EnhancedVolcano package (

https://github.com/kevinblighe/EnhancedVolcano). The dplyr and ggplot2 packages were used to generate graphs.

2.11. Pathway Analysis and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the GSEA Preranked tool (version 4.3.3)[

37,

38] to identify enriched gene sets under different treatment conditions. Genes were ranked based on the numeric ranking statistic. The enriched pathways with FDR q-value <0.05 were considered significant. Pathway analysis was conducted using the Reactome package[

39] to identify pathways enrichment for DEGs under different treatment conditions.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All in vitro experiments were performed in triplicate (n=3) unless stated otherwise. In vivo experiments were carried out using 5 mice per group (total n=20 mice). All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (San Diego, CA, USA). All data are represented as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare multiple means across different groups. In all cases, p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

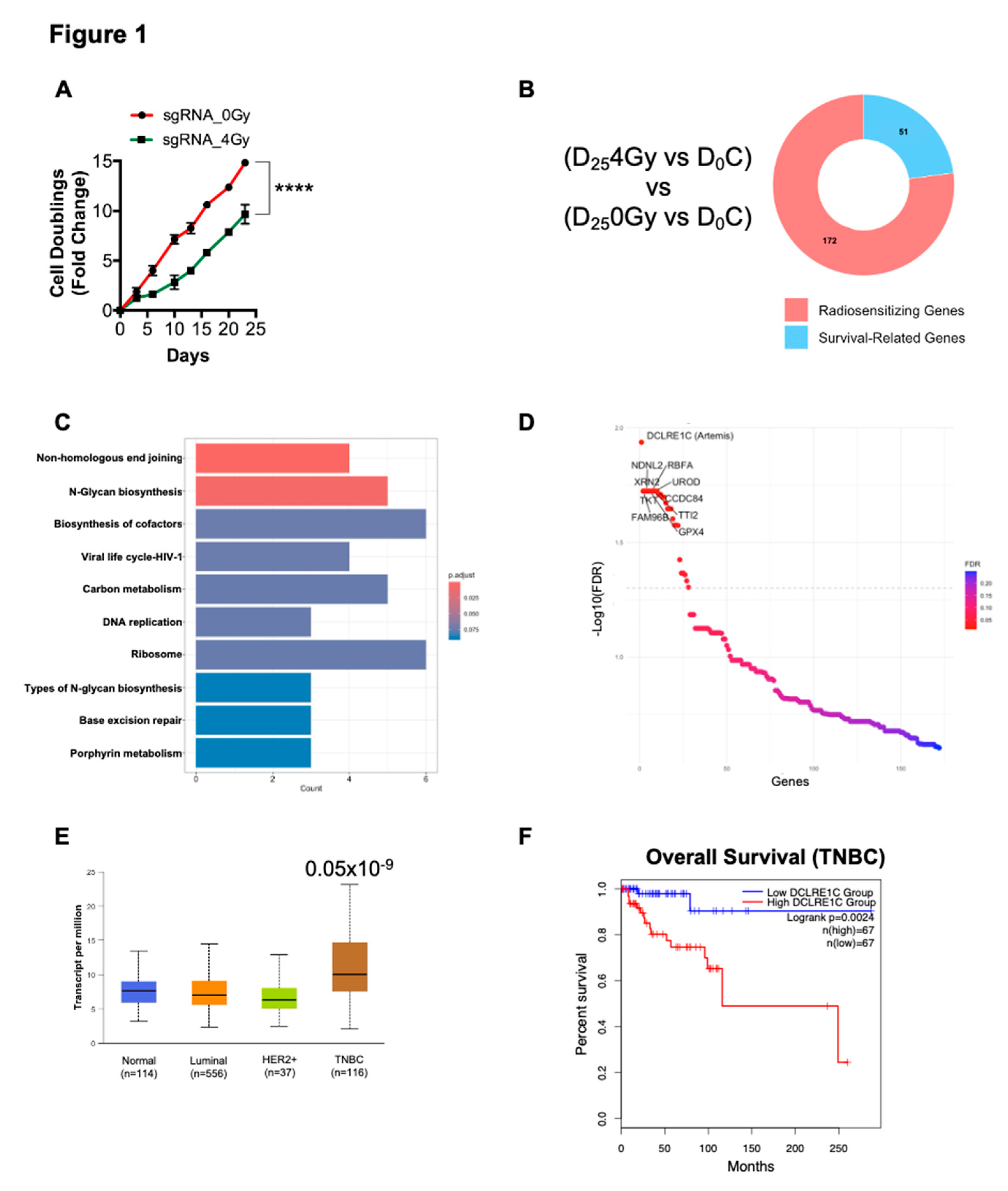

3.1. Genome-Wide CRISPR Knockout Screen Identifies Artemis as the Top Radiosensitizing Target

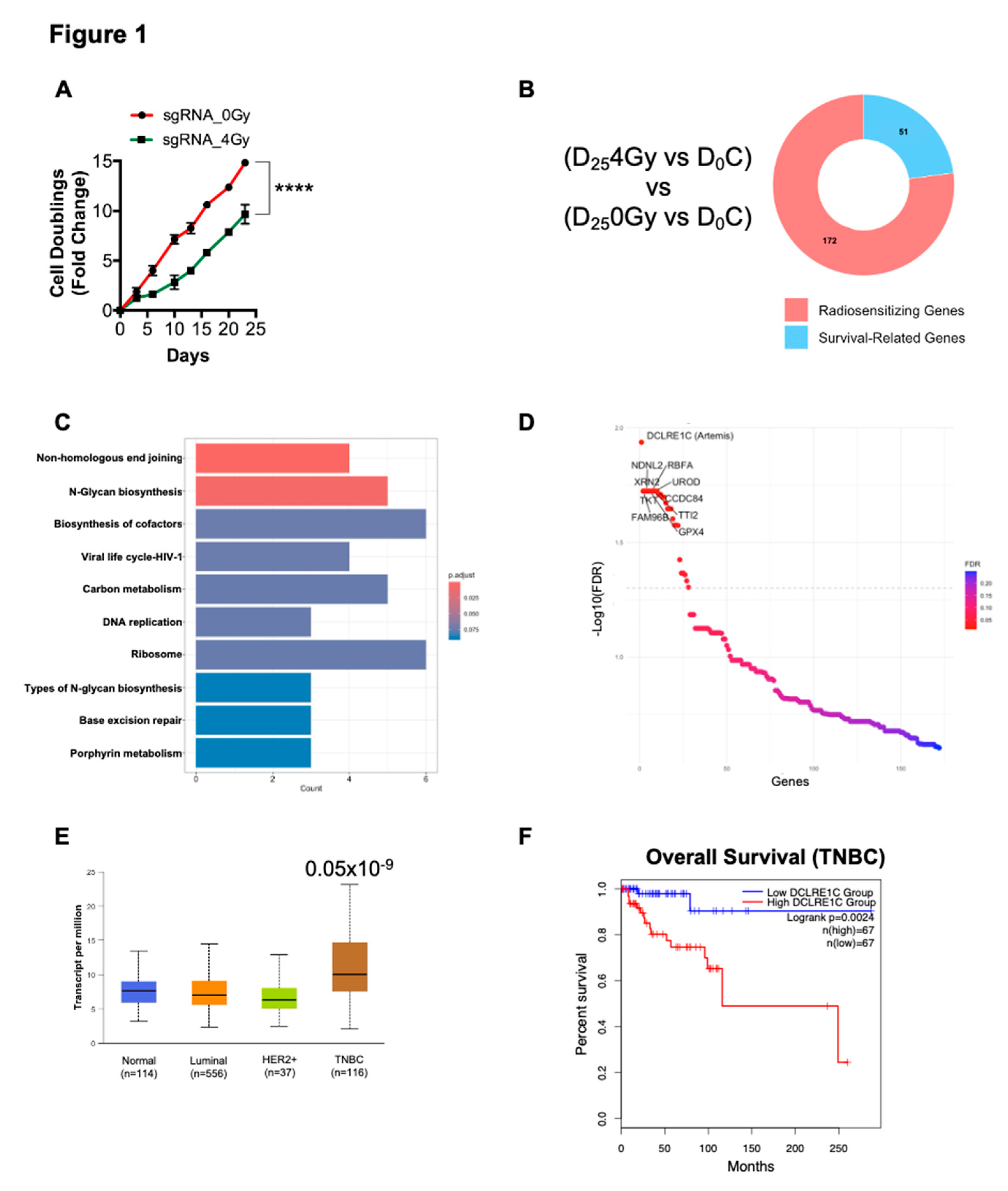

To identify potential genes involved in radioresistance, we performed a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 dropout screen in MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells. MDA-MB-231 cells expressing Cas9 were transduced with the human Moffat TKO-v2 library. Targeted sgRNA sequencing on genomic DNA (gDNA) from a fraction of cells collected pre-treatment was done to determine baseline sgRNA abundance (day 0, D

0). The remaining cells were treated with 0 Gy (non-irradiated control) and 4 Gy of radiation and subsequently passaged and cultured for 25 days (D

25), at which point gDNA was collected for sgRNA-sequencing (Supplementary Figure 1A). We found that 4 Gy RT significantly increased the doubling time of CRISPR-Cas9 knockout cells compared to the no-RT control (

Figure 1A). We then analyzed the sgRNA-sequencing data to identify sgRNAs that were selectively depleted in the D

254Gy treated cells compared to D

0C (

Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure 1A). These depleted sgRNAs have a high probability of representing genes whose loss-of-function sensitized MDA-MB-231 cells to RT. The putative radiosensitizing target from D

254Gy vs D

0C were then cross referenced to the D

25C vs D

0 gene list to identify hits specific to RT and to exclude survival related genes. This identified 172 potential radiosensitizing targets (Figure1B, Supplementary Table 2). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis on the candidate gene list revealed that pathways such NHEJ, DNA replication and base excision repair were significantly overrepresented (

Figure 1C) suggesting that inactivation of components of these pathways sensitized MDA-MB-231 cells to RT.

We then foused on the top 10 radiosensitizing targets identified from our screen. We found that DCLRE1C was the top hit in our screen, representing a potential gene whose loss of function resulted in radiosensitization of TNBC cells (

Figure 1D). We also identified additional genes, including Family with sequence similarity 96 member B (FAM96B), Transketolase (TKT), Necdin-like 2 (NDNL2), 5’-3’ Exoribonuclease 2 (XRN2), Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), Ribosome binding factor A (RBFA), TELO2 interacting protein 2 (TTI2), Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD) and Coiled-coil domain-containing 84 (CCDC84) as the top 10 hits in our screen (

Figure 1D). Evidence suggested that most of these genes were directly or indirectly involved in conferring resistance to radio and chemotherapies[

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47].

TCGA analysis revealed that DCLRE1C (Artemis) mRNA expression was significantly upregulated in the TNBC subtype as compared to other breast cancer subtypes and normal tissue (

Figure 1E). Furthermore, survival analysis using the GEPIA2 web-based tool revealed that higher expression of DCLRE1C correlates with poor overall survival of TNBC patients as compared to patients with low DCLRE1C levels (

Figure 1F).

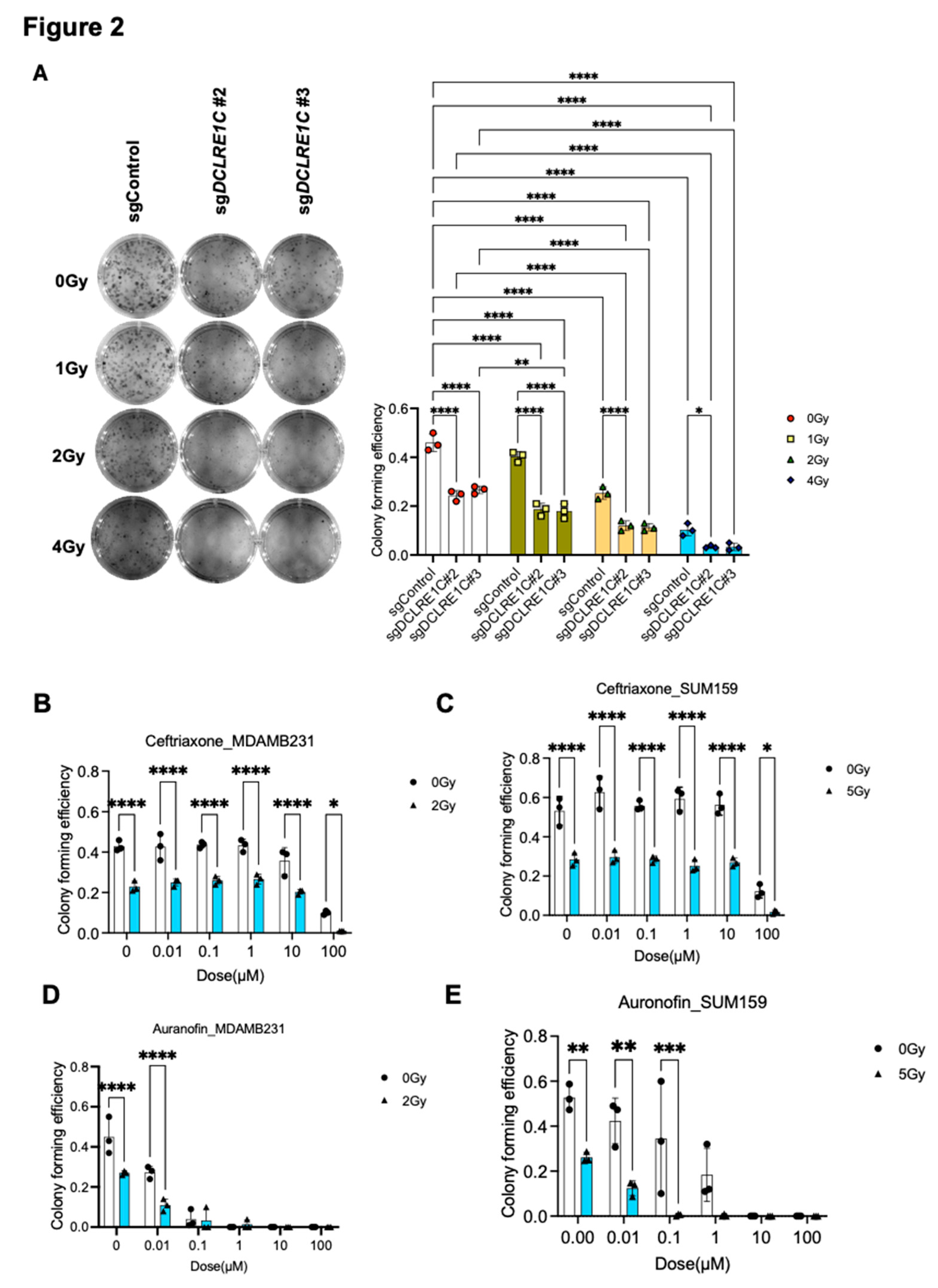

3.2. Loss of Function of Artemis Significantly Decreases Proliferation and Enhances RT Response in TNBC Cells In Vitro

To further investigate the role of Artemis in TNBC, we generated Artemis CRISPR-knockout lines using four unique sgRNAs targeting DCLRE1C gene (sgDCLRE1C#1 - #4). A non-targeting sgRNA (sgControl) was used to generate a control cell line wildtype for Artemis. Knockout lines that showed complete depletion of DCLRE1C (Suppl Figure B) in immunoblotting analysis were used for functional analysis. To investigate the role of Artemis in regulating RT response, we performed colony-forming assays (CFA) using control and CRISPR-knockout cell lines. The cells were exposed to different doses of RT (0, 1, 2 & 4 Gy), and after 7 days, the difference in colony-forming efficiency was calculated. We observed a dose-dependent decrease (1.14, 1.8 & 4.6-fold) in colony numbers in sgControl cells as compared to 0 Gy (

Figure 2A). We found a further reduction in colony numbers in sgDCLRE1C#2; 1.9-fold (0 Gy), 2.5-fold (1 Gy), 4-fold (2 Gy), 14-fold (4 Gy) and #3; 1.7-fold (0 Gy), 2.6-fold (1 Gy), 4-fold (2Gy), 13.9-fold (4 Gy) in response to RT, compared to 0 Gy and sgControl (

Figure 2A). These findings suggest that loss of Artemis function leads to a decrease in clonogenic survival, validating Artemis as a top hit in our screen.

3.3. Putative Pharmacological Inhibitors of Artemis Exert Antiproliferative and Radiosensitization Effects in TNBC

To investigate the possibility of targeting Artemis to enhance radiosensitivity in the clinic, we utilized non-oncology drugs previously reported to inhibit Artemis activity[

27,

48] in cell-free assays[

49], including ceftriaxone, ampicillin and auranofin. We found that 100 µM of ceftriaxone resulted in a 16- and 4-fold (p-value <0.0001) decrease in colony numbers in MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells respectively (

Figure 2B&C). Notably, this decrease was further enhanced (43- and 30-fold; p-value <0.0001) in the presence of RT (ID50 dose of RT[

32,

35]) in both cell lines (

Figure 2B&C) as compared to control.

Auranofin treatment at 0.1 µM concentration induced 11-fold and 1.5-fold (p-value <0.0001) decrease in colony formation in MDA-MB-231 (

Figure 2D) and SUM159 (

Figure 2E) cells, respectively, compared to vehicle treated control cells. This decrease in colony numbers was further enhanced in the presence of RT in both cell lines as compared to control (13-fold in MDA-MB-231 and 94-fold in SUM159) (

Figure 2D&E). However, ampicillin did not have a significant effect on colony-forming efficiency in TNBC cells (Supplementary Figure 1C&D). These results suggested that the pharmacological inhibition of Artemis exerted anti-proliferative effects on TNBC cells, which are further enhanced in the presence of RT.

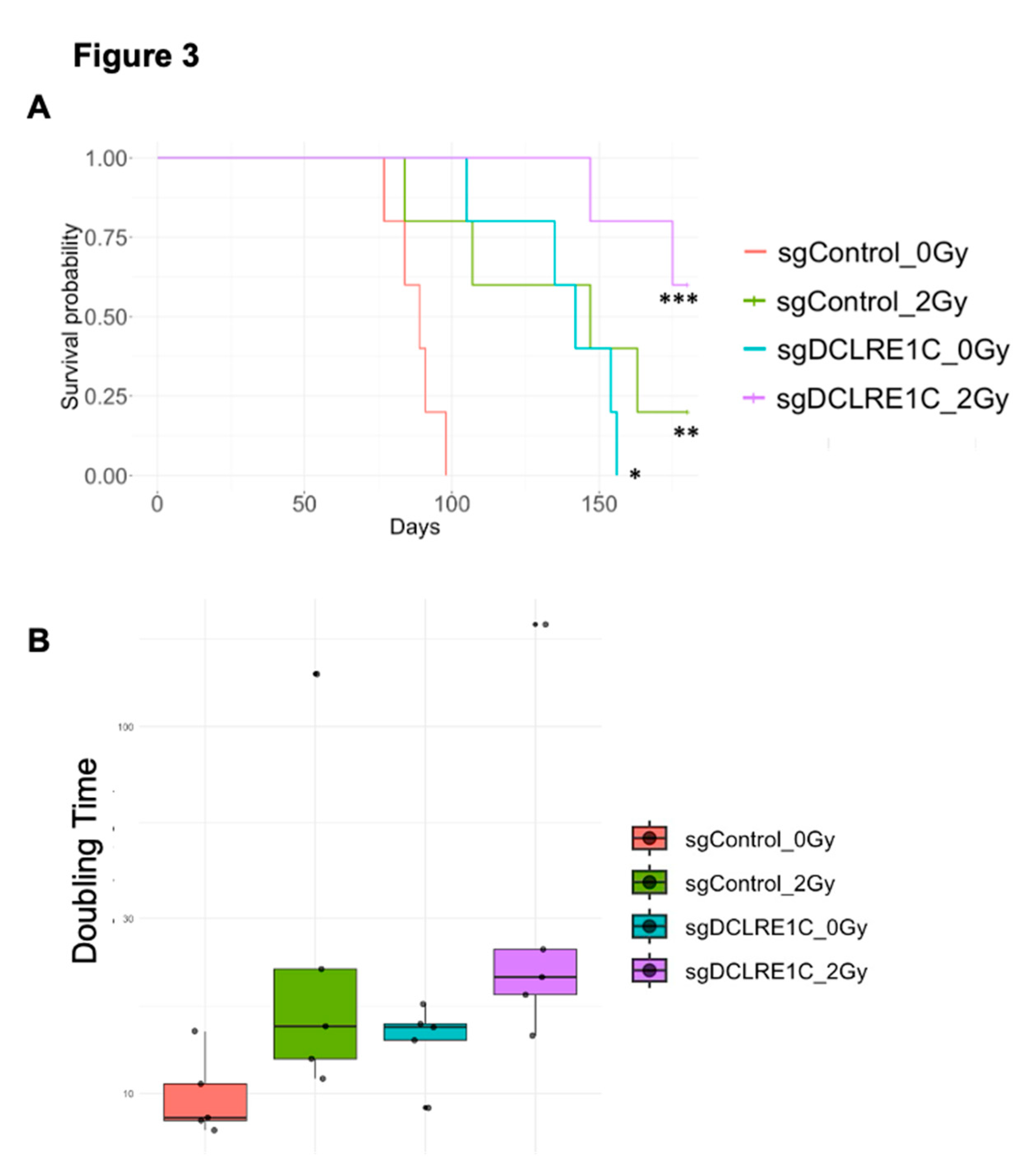

3.4. Loss of Function of Artemis Significantly Impairs Growth and Enhances Radiotherapy Response of TNBC Tumors In Vivo

To assess the role of Artemis in vivo, both sgControl and sgDCLRE1C#2 were exposed to either 0 Gy or 2 Gy (ID50 dose) radiation, and 1x106 viable cells were injected into 4-6 weeks old female NOD-SCID mice (Supplementary Figure 1E). Compared to mice in the sgControl_0Gy group (median 89 days), the median time to reach humane endpoint (1,500mm3 tumor volume) was significantly extended in the sgControl_2Gy (median 147 days; p<0.005), sgDCLRE1C_0Gy (median 142 days; <0.01), and sgDCLRE1C_2Gy (median >165 days; p<0.001) (

Figure 3A) groups. Additionally, we found that the tumor doubling times of sgControl_0Gy, sgControl_2Gy, sgDCLRE1C_0Gy, and sgDCLRE1C_2Gy were 10.1, 39.9, 14.3 & 53.7 days, respectively (

Figure 3B). Taken together, our data demonstrates that the loss of function of Artemis and RT combination significantly reduces TNBC growth and improves survival of tumor bearing mice.

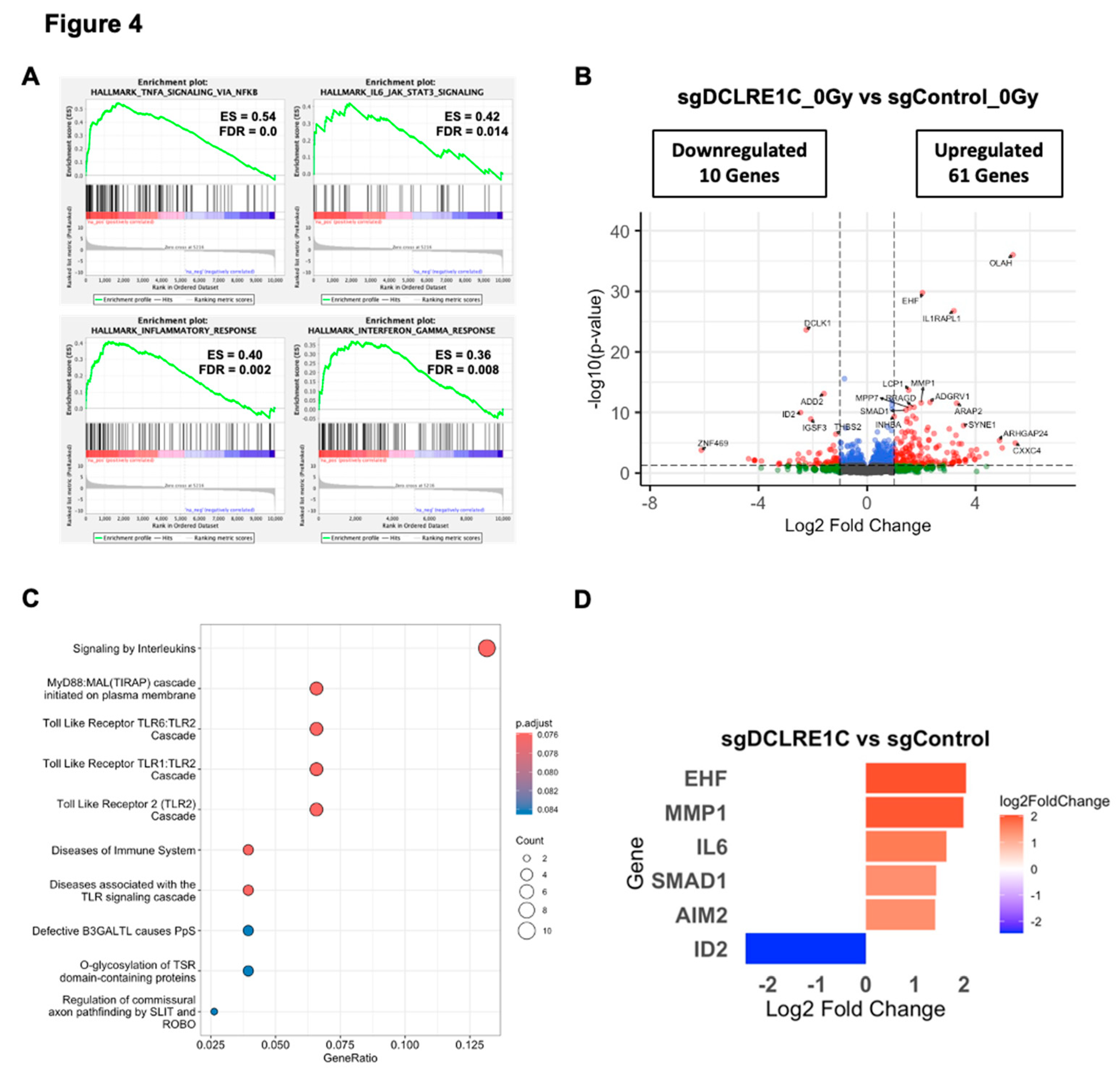

3.5. Loss of Artemis Expression Activates Anticancer Phenotypes in TNBC

To explore the mechanisms underlying the observed antiproliferative and radiosensitization effects mediated by the loss of Artemis, we performed bulk RNA-Seq on control and Artemis knockout cells exposed to either 0 or 2 Gy of RT. Whole transcriptomic profiles of the biological replicates clustered separately for each treatment condition (Supplementary Figure 2A). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of sgDCLRE1C_0Gy vs sgControl_0Gy for hallmark pathways revealed significant (FDR-q-value <0.05) enrichment of various inflammatory and senescence[

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55] associated gene sets including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFA) signaling via NFκB, IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, inflammatory response and interferon gamma response (

Figure 4A, Supplementary Table 3). We then restricted our analysis to a most significantly perturbed gene list (adjusted p-value <0.05). Compared to sgControl, we observed 122 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Artemis knockout cells (Supplementary Table 4). Among these DEGs, 61 genes were significantly upregulated (log2 foldchange ≥ 1.0), and 10 were significantly downregulated (log2 foldchange ≤ -1.0) (

Figure 4B, Supplementary Table 4). Furthermore, the Reactome pathway analysis on these genes revealed enrichment of inflammatory pathways such as Toll-like receptor and interleukin signaling (

Figure 4C). We found a number of DEGs associated with cellular senescence and SASP that were upregulated including: Absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)[

56], ETS homologous factor (EHF)[

57], interleukin 6 (IL6)[

58], matrix metallopeptidase 1 (MMP1)[

59], Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)[

55] and SMAD family member 1 (SMAD1)[

60]; as well as Inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (ID2)[

61], which is involved in inhibition of senescence, was significantly downregulated in the absence of Artemis (

Figure 4D).

To further understand the clinical relevance of DEGs upon Artemis depletion, we analyzed gene expression patterns across different breast cancer subtypes using the TCGA-clinical invasive carcinoma database. We found that most of the SASP-associated genes upregulated in the absence of Artemis had a significantly lower gene expression in TNBC samples compared to normal breast tissues (Supplementary Figure 2B). Similarly, genes downregulated in the Artemis knockout condition had higher expression in TNBC samples compared to normal tissue samples (Supplementary Figure 2B).

3.6. Artemis Deficiency Further Enhances RT Effects in TNBC via Induction of G2/M Arrest and Senescence

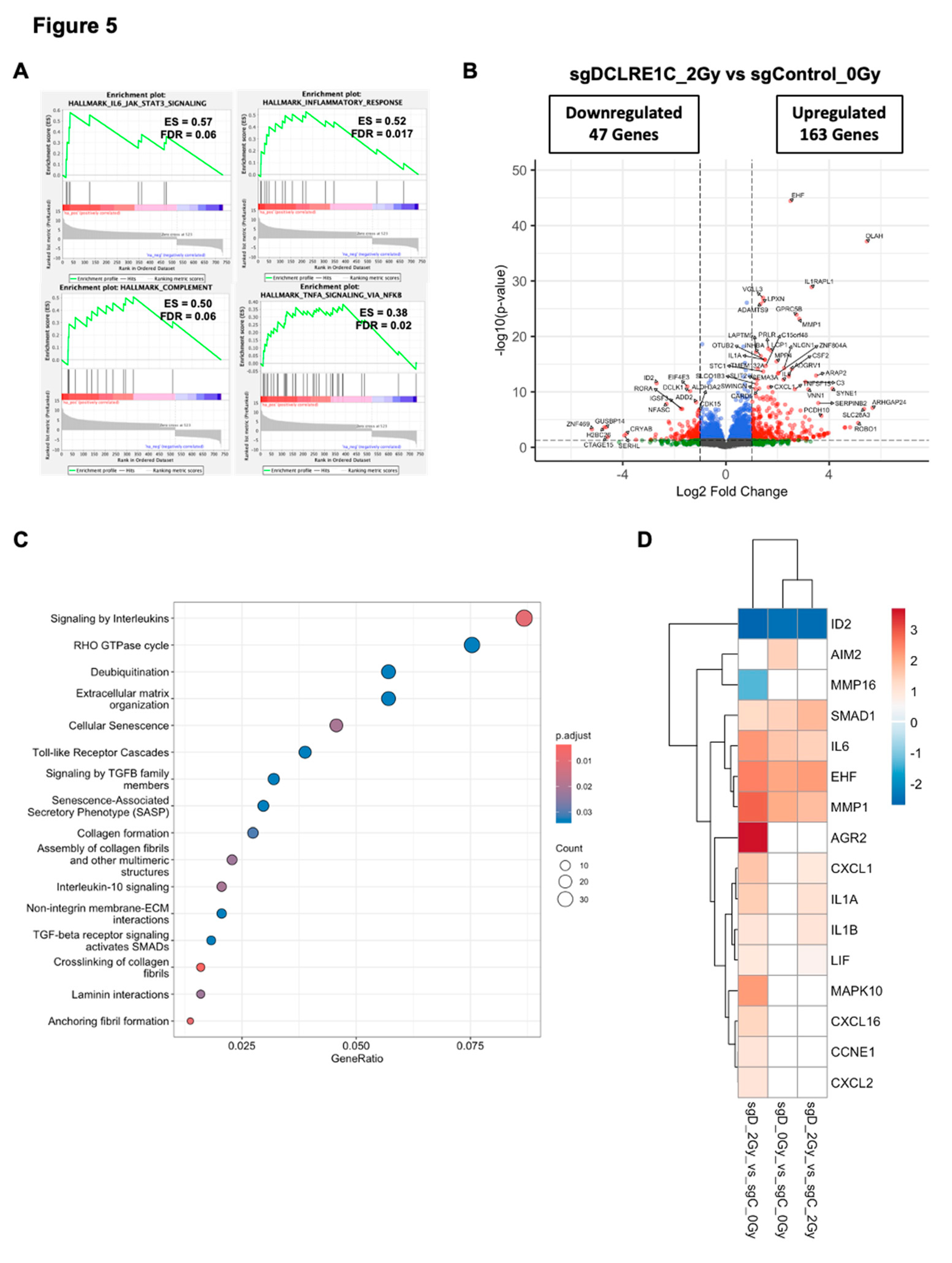

To investigate how the loss of Artemis enhanced RT response, we analyzed DEGs in sgDCLRE1C_2Gy as compared to sgControl_0Gy. Similar to the Artemis knockout alone condition, GSEA revealed enrichment of IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, inflammatory response and TNFA/NFκB signaling gene sets (

Figure 5A) in Artemis knockout cells exposed to RT relative to control cells (sgControl_0Gy). RT, under Artemis knockout condition, resulted in the perturbation of 734 genes, with 163 upregulated and 47 downregulated genes (

Figure 5B). Furthermore, the Reactome pathway analysis revealed overrepresentation of pathways associated with cellular senescence, SASP, interleukin, and Toll-like receptor signaling in radiation-treated TNBC cells lacking Artemis expression (

Figure 5C). Consistent with this result, we found perturbation of additional senescence/SASP-associated genes in the presence of RT (

Figure 5D). We also analyzed DEGs in sgDCLRE1C_2Gy compared to sgControl_2Gy. Although the enrichment of IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling (Supplementary Table 3) was not statistically significant in our GSEA, we observed perturbation of senescence/SASP-associated genes (

Figure 5D).

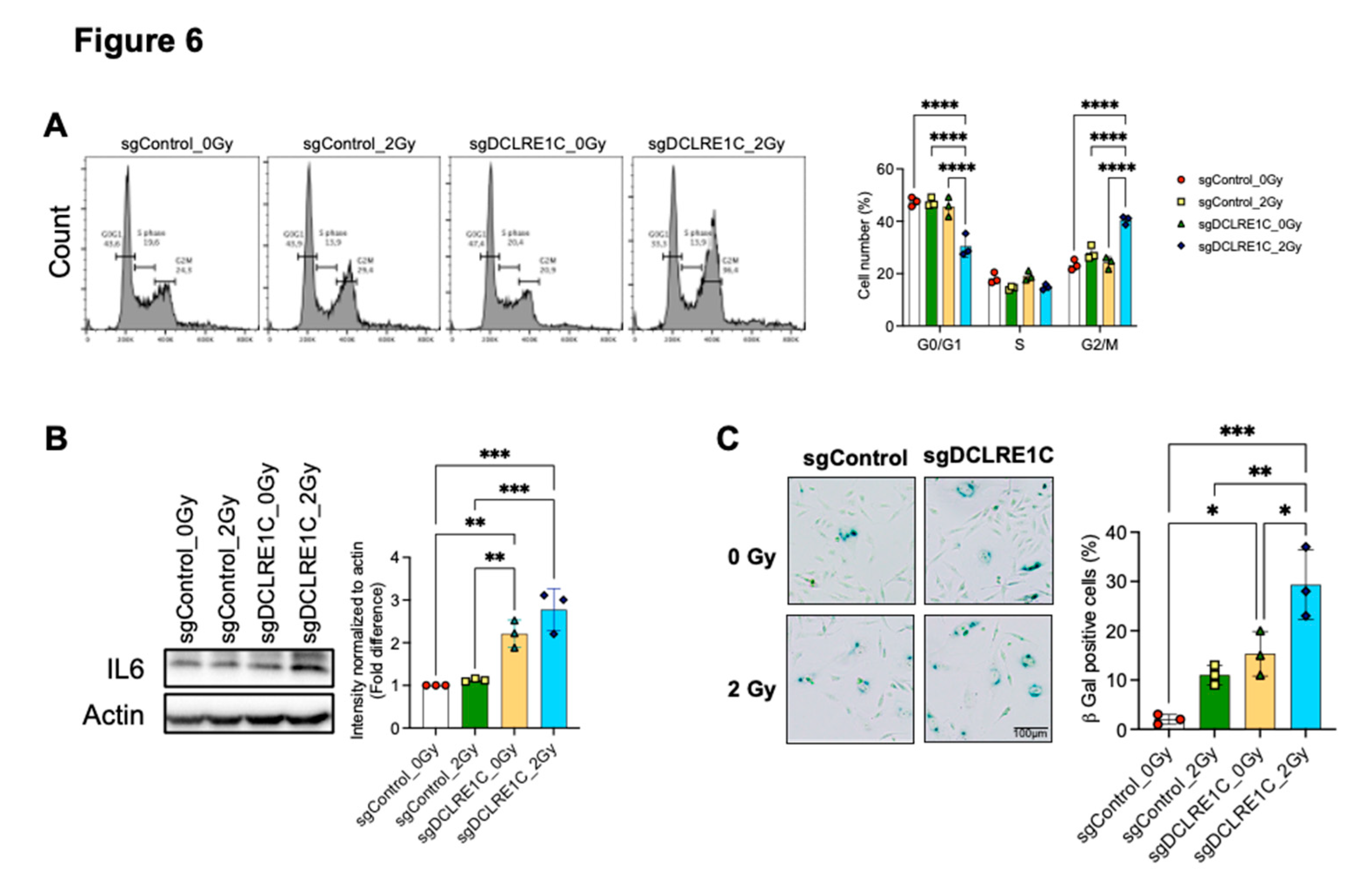

Next, we chose to investigate the consequence of senescence signaling activation on cell cycle in Artemis knockout cells following RT. Previous studies have demonstrated a bidirectional relationship between cell cycle arrest and senescence[

62,

63,

64]. We found that Artemis knockout cells exposed to RT at 24 hours had a significant increase in the percentage of cells in G2/M phase relative to control (1.9-fold; p value <0.0001), RT alone (1.4-fold; p value <0.0001) and Artemis knockout-alone (1.6-fold; p value <0.0001) conditions (

Figure 6A). Overall, our data suggested that Artemis knockout enhances RT response via induction of G2/M arrest.

Our bulk RNA-seq revealed enrichment of the IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway, suggesting its potential role in activation of cellular senescence and SASP. We observed that IL6 expression was significantly upregulated in Artemis knockout cells, both alone and in combination with RT (

Figure 6B). This increase in IL6 mRNA correlated with higher IL6 protein levels in Artemis knockout cells alone, which further increased in the presence of RT (

Figure 6B) relative to control. Given that GSEA identified significant enrichment of the IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling axis in both Artemis knockout, alone or in combination with RT, we assessed STAT3 phosphorylation. Although we observed an increasing trend in STAT3 phosphorylation in Artemis knockout cells, with or without RT, the changes were not significant relative to control (Supplementary Figure 2C).

Finally, to investigate whether loss of Artemis induced senescence in TNBC cells, we quantified cellular senescence using the β-galactosidase assay. We observed a significant increase in the number of senescent cells in the absence of Artemis as compared to control (p value = 0.02), which further increased in the presence of RT as compared to control (p value = 0.0003), RT alone (p value = 0.003) and Artemis knockout alone (p value = 0.01) (

Figure 6C). Taken together, our data demonstrated that combination of Artemis knockout and RT enhances anti-tumor effects by inducing G2/M arrest and activating cellular senescence.

4. Discussion

RT is a key treatment modality used for both local and regional control of primary breast cancer and its metastases[

4,

5,

7]. However, development of resistance to RT results in disease recurrence and poor treatment outcomes[

65]. For an effective RT response, it is imperative to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying cellular responses to RT, which will help identify novel targets and biomarkers to enhance RT response in TNBC patients.

We used genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in MDA-MB-231 cells and identified 172 potential radiosensitizing targets. Our screen revealed Artemis, a key component of the NHEJ pathway, as a top hit, whose depletion resulted in reduced cellular viability following RT. Previous studies have shown that loss of Artemis function[

66,

67,

68,

69,

70] and, inherited mutations or polymorphic variants results in cellular radiosensitivity[

71,

72,

73,

74]. Our analysis of the breast cancer TCGA database revealed that

DCLRE1C mRNA expression is significantly higher in TNBC, compared to normal breast tissue and other breast cancer subtypes (

Figure 1E). Notably, TNBC patients with higher

DCLRE1C mRNA expression had poor overall survival (

Figure 1F). This was consistent with evidence highlighting the role of Artemis as a radioresistance gene in multiple cancers, including cervical, hepatobiliary, and colorectal cancers resulting in worse overall survival and poor prognosis[

67,

70,

75,

76,

77]. These results emphasize the potential of Artemis as a biomarker and therapeutic target to modulate responses to RT as well as chemotherapy[

75,

76,

78].

Artemis deficiency has been reported to exhibit antiproliferative[

66,

67,

70,

76,

77,

79], pro-apoptotic[

80] and anti-invasive[

81] effects in various cancers. Our characterization of Artemis knockout TNBC models indicated that its depletion alone led to a significant decrease in proliferation and increase in tumor doubling times of TNBC cells, as well as improved survival of mice bearing tumor xenografts. Additionally, our data also demonstrated that RT in Artemis-depleted models led to a significant improvement in the survival of mice bearing tumor xenografts compared to either Artemis depletion or RT alone. These are novel findings, emphasizing the critical role of Artemis in TNBC pathogenesis and present us with an opportunity for targeting Artemis in combination with RT or DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agents to enhance anticancer treatment efficacy. Collectively, these findings suggest that Artemis holds potential as both a therapeutic target and a prognostic biomarker in TNBC.

To this end, we used clinically approved non-oncology drugs previously shown to inhibit Artemis activity in cell-free assays[

27], since no clinically approved novel drugs inhibit Artemis. A previous study demonstrated that β-lactam antibiotics can be repurposed as a pro-senescent radiosensitizer in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells[

82]. The β-lactam antibiotics such as ceftriaxone[

27] and ampicillin[

48], and auranofin[

27], which displaces zinc (Zn) from the β-CASP domain have been shown to inhibit Artemis’ nuclease activity. Additionally, auranofin has been shown to sensitize colon cancer cells to RT

in vivo and human colon cancer patient-derived organoids[

83]. Our results showed that ceftriaxone and auranofin, but not ampicillin, significantly reduced colony formation, an effect further enhanced when combined with RT in both MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells. However, both ceftriaxone[

84,

85] and auranofin[

86,

87] have be shown to exhibit additional mechanism of anti-cancer effects which needs to be further investigated. Our findings support further investigation into the potential repurposing of ceftriaxone and auranofin for TNBC treatment. These results also highlight the opportunity to develop novel structural analogs for enhancing radiotherapy efficacy in TNBC.

Cellular senescence or apoptosis is often active in response to unrepaired DNA damage in cells[

88]. Loss of Artemis has been shown to trigger apoptosis in osteosarcoma and cervical cancer cell lines[

80]. However, in our study, DEG analysis revealed perturbation of genes linked to cellular senescence (

Figure 4D). Among these,

IL6, a key component of SASP[

89,

90], was significantly upregulated in the absence of Artemis (

Figure 4D). This upregulation was consistent in Artemis knockout cells exposed to RT. Furthermore, the increase in

IL6 mRNA correlated with IL6 protein levels, which further increased in the presence of RT (

Figure 6B). Along with the enrichment of IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, our data suggested a possible IL6-mediated radiosensitization through the activation of cellular senescence. Interestingly, Artemis-knockout cells exposed to RT exhibited even greater perturbation of senescence-related genes (

Figure 5D). Consistent with this, we observed a significant increase in cellular senescence in Artemis knockout cells following RT (

Figure 6C) assessed through the β-galactosidase assay. These findings suggest that loss of Artemis triggers cellular senescence, contributing to increased RT sensitivity.

Both unrepaired DNA damage[

91] and cellular senescence[

63] can trigger G2/M phase arrest and promote genomic instability[

92]. Primary skin fibroblasts with mutant Artemis are associated with a defect in the G2 phase of cell cycle following RT[

73]. Loss of Artemis has been shown to cause G1 arrest and subsequent apoptosis through stabilization of the p53 protein [

80]. However, in our study, Artemis knockout cells exposed to RT exhibited significant G2/M phase accumulation 24 hours post RT (

Figure 6A). Taken together, our data suggest that the combination of Artemis knockout and RT results in activation of cellular senescence and G2/M arrest, eventually leading to anti-cancer effects in TNBC cells.

5. Conclusions

For the first time to our knowledge, we show that Artemis plays an important role in TNBC proliferation, growth and senescence. We also show that Artemis knockout facilitates RT responses through activation of senescence pathways and cell cycle perturbations. Artemis knockout alone or in combination with RT leads to significant improvements in survival of xenograft bearing mice, and its mRNA expression correlates with patient outcomes in TNBC. Moreover, we investigated biological mechanisms of Artemis depletion with or without RT and found that Artemis knockout activates inflammatory and cellular senescence pathways and leads to G2/M arrest in response to RT. As such, Artemis appears to represent a promising candidate in TNBC biology, with potential as a treatment response biomarker and novel drug target. Its role in modulating cellular responses to DNA-damage and immune/inflammatory responses warrants further investigation into its utility as a therapeutic vulnerability in combination with RT and DNA-damaging chemotherapeutics and immunotherapies, respectively.

Contributions

V.B.: K.L.T., A.L.A., and A.P. conceived and planned the experiments. V.B., D.G., A.P. performed the experiments. V.B., A.C.B., D.G. contributed to data acquisition. M.V.R. generated Artemis knockout lines. V.B., K.L.T., F.G., F.D., D.W.C., A.L.A. and A.P. contributed to data analysis and interpretation. V.B. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. K.L.T., A.C.B., F.D., D.W.C., A.L.A. and A.P. edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical declarations

Not applicable.

Competing interests

D.W.C., reports consultancy and advisory relationships with AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, GenomeRx, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Inivata/NeoGenomics, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and SAGA and research funding to their institution from AstraZeneca, Guardant Health, Grail, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Inivata/NeoGenomics, Knight, Merck, Pfizer, ProteinQure, and Roche.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in this study are available upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This study was supported by the London Regional Cancer Program Catalyst Grant for Translational Cancer Research, Western University, London ON, and The Department of Surgery Internal Research Fund for Clinical Academics, Western University, London, ON. A.P., is supported by the Clinician Scientist Award, Department of Surgery, Western University, London, ON, Canada; Breast Cancer Canada and the AMOSO 2023-34 Academic Health Sciences Centre Alternative Funding Plan Clinical Innovation Fund Award (#INN24-017), ON, Canada. K.T., was supported by funding from Unity Health Toronto and the Canada Research Chairs program (233198). D.W.C., was supported by Canadian Institute of Health Research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Bartlomiej Kolendowski, Fatemeh Mousavi and Joana R Pinto for their input in transcriptomics data analysis.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIM2 |

Absent in melanoma 2 |

| CCDC84 |

Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 84 |

| CFA |

Colony forming assay |

| CPTAC |

Clinical proteomic tumor analysis consortium |

| DCLRE1C |

DNA cross-link repair 1 C |

| DDSBs |

DNA double stranded breaks |

| EHF |

ETS homologous factor |

| FAM96B |

Family with sequence similarity 96 member B |

| gDNA |

Genomic DNA |

| GPX4 |

Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GSEA |

Gene set enrichment analysis |

| HR |

Homologous recombination |

| ICPC |

International centre proteogenome consortium |

| ID2 |

Inhibitor of DNA binding 2 |

| IL6 |

Interleukin 6 |

| MMP1 |

Matrix metallopeptidase 1 |

| NDNL2 |

Necdin-like 2 |

| NHEJ |

Non-homologous end joining |

| RBFA |

Ribosome binding factor A |

| RT |

Radiotherapy |

| RS-SCID |

Severe combined immunodeficiency with radiation sensitivity |

| SASP |

Senescence associated secretory phenotype |

| SMAD1 |

SAMD family member 1 |

| TCGA |

The cancer genome atlas |

| TTI2 |

TELO2 interacting protein 2 |

| TKO-v2 |

Toronto knockout version 2 |

| TKT |

Transketolase |

| TLRs |

Toll-like receptors |

| TNBC |

Triple negative breast cancer |

| TNFA |

Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| UROD |

Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase |

| XRN2 |

5’ – 3’ Exoribonuclease 2 |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, R.; Ordóñez-Morán, P.; Allegrucci, C. Challenges for Triple Negative Breast Cancer Treatment: Defeating Heterogeneity and Cancer Stemness. Cancers 2022, 14, 4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, N.; Wu, H.; Yu, Z. Advancements and challenges in triple-negative breast cancer: a comprehensive review of therapeutic and diagnostic strategies. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1405491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, S., P. McGale. Effect of Radiotherapy after Breast-Conserving Surgery on 10-Year Recurrence and 15-Year Breast Cancer Death: Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data for 10,801 Women in 17 Randomised Trials. Lancet 2011, 378, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar]

- McGale, P. Taylor, C. Correa, D. Cutter, F. Duane, M. Ewertz, R. Gray, G. Mannu, R. Peto, T. Whelan, Y. Wang, Z. Wang, and S. Darby. "Effect of Radiotherapy after Mastectomy and Axillary Surgery on 10-Year Recurrence and 20-Year Breast Cancer Mortality: Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data for 8135 Women in 22 Randomised Trials." Lancet 383, no. 9935 (2014): 2127-35.

- Gradishar, W. J., M. S. Moran, J. Abraham, R. Aft, D. Agnese, K. H. Allison, B. Anderson, H. J. Burstein, H. Chew, C. Dang, A. D. Elias, S. H. Giordano, M. P. Goetz, L. J. Goldstein, S. A. Hurvitz, S. J. Isakoff, R. C. Jankowitz, S. H. Javid, J. Krishnamurthy, M. Leitch, J. Lyons, J. Mortimer, S. A. Patel, L. J. Pierce, L. H. Rosenberger, H. S. Rugo, A. Sitapati, K. L. Smith, M. L. Smith, H. Soliman, E. M. Stringer-Reasor, M. L. Telli, J. H. Ward, K. B. Wisinski, J. S. Young, J. Burns, and R. Kumar. "Breast Cancer, Version 3.2022, Nccn Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology." J Natl Compr Canc Netw 20, no. 6 (2022): 691-722.

- Zhou, Z.-R.; Wang, X.-Y.; Yu, X.-L.; Mei, X.; Chen, X.-X.; Hu, Q.-C.; Yang, Z.-Z.; Guo, X.-M. Building radiation-resistant model in triple-negative breast cancer to screen radioresistance-related molecular markers. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 108–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tuan, J.; Shao, Z.; Guo, X.; Feng, Y. Analysis in early stage triple-negative breast cancer treated with mastectomy without adjuvant radiotherapy: Patterns of failure and prognostic factors. Cancer 2013, 119, 2366–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, X.; Feng, Y. Radiotherapy Can Improve the Disease-Free Survival Rate in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients with T1–T2 Disease and One to Three Positive Lymph Nodes After Mastectomy. Oncol. 2013, 18, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F. Kyriakides, S. Ohno, F. Penault-Llorca, P. Poortmans, I. T. Rubio, S. Zackrisson, and E. Senkus. "Early Breast Cancer: Esmo Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up†." Ann Oncol 30, no. 8 (2019): 1194-220.

- Li, L.-Y.; Guan, Y.-D.; Chen, X.-S.; Yang, J.-M.; Cheng, Y. DNA Repair Pathways in Cancer Therapy and Resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, T. Molecular mechanisms of tumor resistance to radiotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Chen, Y.; Liang, N.; Xie, J.; Deng, G.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Targeting Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Radioresistance: Crosslinked Mechanisms and Strategies. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 775238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwa, T., M. Kobayashi, J. M. Nam, and H. Harada. "Tumor Microenvironment and Radioresistance." Exp Mol Med 53, no. 6 (2021): 1029-35.

- Carlos-Reyes, A.; Muñiz-Lino, M.A.; Romero-Garcia, S.; López-Camarillo, C.; la Cruz, O.N.H.-D. Biological Adaptations of Tumor Cells to Radiation Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouellette, M.M.; Zhou, S.; Yan, Y. Cell Signaling Pathways That Promote Radioresistance of Cancer Cells. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, V.; Pellizzari, S.; Allan, A.L.; Wong, E.; Lock, M.; Brackstone, M.; Lohmann, A.E.; Cescon, D.W.; Parsyan, A. Radiotherapy and radiosensitization in breast cancer: Molecular targets and clinical applications. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2022, 169, 103566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M. DNA repair pathways in breast cancer: from mechanisms to clinical applications. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 200, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegmans, A. P., A. Ward, E. Ivanova, P. H. G. Duijf, M. N. Adams, I. M. Najib, R. Van Oosterhout, M. C. Sadowski, G. Kelly, S. W. Morrical, K. O'Byrne, J. S. Lee, and D. J. Richard. "Genome Instability and Pressure on Non-Homologous End Joining Drives Chemotherapy Resistance Via a DNA Repair Crisis Switch in Triple Negative Breast Cancer." NAR Cancer 3, no. 2 (2021): zcab022.

- Dylgjeri, E.; Knudsen, K.E. DNA-PKcs: A Targetable Protumorigenic Protein Kinase. Cancer Res. 2021, 82, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragojevic, S.; Ji, J.; Singh, P.K.; Connors, M.A.; Mutter, R.W.; Lester, S.C.; Talele, S.M.; Zhang, W.; Carlson, B.L.; Remmes, N.B.; et al. Preclinical Risk Evaluation of Normal Tissue Injury With Novel Radiosensitizers. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 111, e54–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla-Soto, J. , and P. Cortes. "Vdj Recombination: Artemis and Its in Vivo Role in Hairpin Opening." J Exp Med 197, no. 5 (2003): 543-7.

- Vogt, A.; He, Y.; Lees-Miller, S.P. How to fix DNA breaks: new insights into the mechanism of non-homologous end joining. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2023, 51, 1789–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pluth, J.M.; Cooper, P.K.; Cowan, M.J.; Chen, D.J.; Yannone, S.M. Artemis deficiency confers a DNA double-strand break repair defect and Artemis phosphorylation status is altered by DNA damage and cell cycle progression. DNA Repair 2005, 4, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsyan, A. Bhat, H. Athwal, E. A. Goebel, and A. L. Allan. "Artemis and Its Role in Cancer." Transl Oncol 51 (2025): 102165.

- Shahi, R.B.; De Brakeleer, S.; Caljon, B.; Pauwels, I.; Bonduelle, M.; Joris, S.; Fontaine, C.; Vanhoeij, M.; Van Dooren, S.; Teugels, E.; et al. Identification of candidate cancer predisposing variants by performing whole-exome sequencing on index patients from BRCA1 and BRCA2-negative breast cancer families. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosaatmadja, Y.; Baddock, H.T.; A Newman, J.; Bielinski, M.; E Gavard, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.M.M.; A Dannerfjord, A.; Schofield, C.J.; McHugh, P.J.; Gileadi, O. Structural and mechanistic insights into the Artemis endonuclease and strategies for its inhibition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 9310–9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, K.L.; Silvester, J.; Elliott, M.J.; Ba-Alawi, W.; Duncan, M.H.; Elia, A.C.; Mer, A.S.; Smirnov, P.; Safikhani, Z.; Haibe-Kains, B.; et al. Disruption of the anaphase-promoting complex confers resistance to TTK inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 201719577–E1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, T.; Chandrashekhar, M.; Aregger, M.; Steinhart, Z.; Brown, K.R.; MacLeod, G.; Mis, M.; Zimmermann, M.; Fradet-Turcotte, A.; Sun, S.; et al. High-Resolution CRISPR Screens Reveal Fitness Genes and Genotype-Specific Cancer Liabilities. Cell 2015, 163, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Karthikeyan, S.K.; Korla, P.K.; Patel, H.; Shovon, A.R.; Athar, M.; Netto, G.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Kumar, S.; Manne, U.; et al. UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia 2022, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Bashel, B.; Balasubramanya, S.A.H.; Creighton, C.J.; Ponce-Rodriguez, I.; Chakravarthi, B.V.S.K.; Varambally, S. UALCAN: A portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsyan, A.; Cruickshank, J.; Hodgson, K.; Wakeham, D.; Pellizzari, S.; Bhat, V.; Cescon, D.W. Anticancer effects of radiation therapy combined with Polo-Like Kinase 4 (PLK4) inhibitor CFI-400945 in triple negative breast cancer. Breast 2021, 58, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, N.; Samaga, D.; Belka, C.; Zitzelsberger, H.; Lauber, K. Analysis of clonogenic growth in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 4963–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, N.A.P.; Rodermond, H.M.; Stap, J.; Haveman, J.; Van Bree, C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari, S.; Bhat, V.; Athwal, H.; Cescon, D.W.; Allan, A.L.; Parsyan, A. PLK4 as a potential target to enhance radiosensitivity in triple-negative breast cancer. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M. I. Huber, and S. Anders. "Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for Rna-Seq Data with Deseq2." Genome Biol 15, no. 12 (2014): 550.

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, V.K.; Lindgren, C.M.; Eriksson, K.-F.; Subramanian, A.; Sihag, S.; Lehar, J.; Puigserver, P.; Carlsson, E.; Ridderstråle, M.; Laurila, E.; et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003, 34, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; He, Q.-Y. ReactomePA: an R/Bioconductor package for reactome pathway analysis and visualization. Mol. Biosyst. 2015, 12, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redwood, A.B.; Zhang, X.; Seth, S.B.; Ge, Z.; Bindeman, W.E.; Zhou, X.; Sinha, V.C.; Heffernan, T.P.; Piwnica-Worms, H. The cytosolic iron–sulfur cluster assembly (CIA) pathway is required for replication stress tolerance of cancer cells to Chk1 and ATR inhibitors. npj Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, E.; Yue, S.; Moriyama, E.H.; Hui, A.B.; Kim, I.; Shi, W.; Alajez, N.M.; Bhogal, N.; Li, G.; Datti, A.; et al. Uroporphyrinogen Decarboxylase Is a Radiosensitizing Target for Head and Neck Cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 67ra7–67ra7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurov, K.E.; Cotta-Ramusino, C.; Elledge, S.J. A genetic screen identifies the Triple T complex required for DNA damage signaling and ATM and ATR stability. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1939–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, L.; Zhu, M.; Luo, D.; Chen, H.; Li, B.; Lao, Y.; An, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, A.; et al. TKT-PARP1 axis induces radioresistance by promoting DNA double-strand break repair in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 2024, 43, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Crabben, S. N. P. Hennus, G. A. McGregor, D. I. Ritter, S. C. Nagamani, O. S. Wells, M. Harakalova, I. K. Chinn, A. Alt, L. Vondrova, R. Hochstenbach, J. M. van Montfrans, S. W. Terheggen-Lagro, S. van Lieshout, M. J. van Roosmalen, I. Renkens, K. Duran, I. J. Nijman, W. P. Kloosterman, E. Hennekam, J. S. Orange, P. M. van Hasselt, D. A. Wheeler, J. J. Palecek, A. R. Lehmann, A. W. Oliver, L. H. Pearl, S. E. Plon, J. M. Murray, and G. van Haaften. "Destabilized Smc5/6 Complex Leads to Chromosome Breakage Syndrome with Severe Lung Disease." J Clin Invest 126, no. 8 (2016): 2881-92.

- Morales, J. C., P. Richard, P. L. Patidar, E. A. Motea, T. T. Dang, J. L. Manley, and D. A. Boothman. "Xrn2 Links Transcription Termination to DNA Damage and Replication Stress." PLoS Genet 12, no. 7 (2016): e1006107.

- Lei, G.; Zhang, Y.; Koppula, P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Lin, S.H.; Ajani, J.A.; Xiao, Q.; Liao, Z.; Wang, H.; et al. The role of ferroptosis in ionizing radiation-induced cell death and tumor suppression. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wolf, B.; Oghabian, A.; Akinyi, M.V.; Hanks, S.; Tromer, E.C.; E van Hooff, J.J.; van Voorthuijsen, L.; E van Rooijen, L.; Verbeeren, J.; Uijttewaal, E.C.H.; et al. Chromosomal instability by mutations in the novel minor spliceosome component CENATAC. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e106536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chang, H.H.; Niewolik, D.; Hedrick, M.P.; Pinkerton, A.B.; Hassig, C.A.; Schwarz, K.; Lieber, M.R. Evidence That the DNA Endonuclease ARTEMIS also Has Intrinsic 5′-Exonuclease Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 7825–7834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, G.; Lieber, M.R.; Williams, D.R. Structural analysis of the basal state of the Artemis:DNA-PKcs complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 7697–7720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.; Scuoppo, C.; Wang, X.; Fang, X.; Balgley, B.; Bolden, J.E.; Premsrirut, P.; Luo, W.; Chicas, A.; Lee, C.S.; et al. Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-κB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhaya-Pillai, R., X. Yang, T. Tchkonia, G. M. Martin, J. L. Kirkland, and J. Oshima. "Tnf-A/Ifn-Γ Synergy Amplifies Senescence-Associated Inflammation and Sars-Cov-2 Receptor Expression Via Hyper-Activated Jak/Stat1." Aging Cell 21, no. 6 (2022): e13646.

- Bae, E.-J.; Choi, M.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, D.-K.; Jung, M.K.; Kim, C.; Kim, T.-K.; Lee, J.S.; Jung, B.C.; Shin, S.J.; et al. TNF-α promotes α-synuclein propagation through stimulation of senescence-associated lysosomal exocytosis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Gong, H.; Wei, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Z.; Feng, F. Hesperidin inhibits lung fibroblast senescence via IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway to suppress pulmonary fibrosis. Phytomedicine 2023, 112, 154680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prattichizzo, F.; Giuliani, A.; Recchioni, R.; Bonafè, M.; Marcheselli, F.; De Carolis, S.; Campanati, A.; Giuliodori, K.; Rippo, M.R.; Brugè, F.; et al. Anti-TNF-α treatment modulates SASP and SASP-related microRNAs in endothelial cells and in circulating angiogenic cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 11945–11958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J., H. Kim, J. H. Lee, and C. Hwangbo. "Toll-Like Receptor 4 (Tlr4): New Insight Immune and Aging." Immun Ageing 20, no. 1 (2023): 67.

- Duan, X.; Ponomareva, L.; Veeranki, S.; Panchanathan, R.; Dickerson, E.; Choubey, D. Differential Roles for the Interferon-Inducible IFI16 and AIM2 Innate Immune Sensors for Cytosolic DNA in Cellular Senescence of Human Fibroblasts. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011, 9, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Lim, J.; Lee, A.; Kim, K.-I.; Lim, J.-S. Anticancer Effect of E26 Transformation-Specific Homologous Factor through the Induction of Senescence and the Inhibition of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Cancers 2023, 15, 5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernot, J.P. Senescence-Associated Pro-inflammatory Cytokines and Tumor Cell Plasticity. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, N.; Papismadov, N.; Solomonov, I.; Sagi, I.; Krizhanovsky, V. The ECM path of senescence in aging: components and modifiers. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 2636–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Z., Y. M. Zhou, L. L. Zhang, X. J. Chen, Y. Y. Yang, D. Zhang, K. C. Zhu, X. K. Kong, L. H. Sun, B. Tao, H. Y. Zhao, and J. M. Liu. "Bmp9 Reduces Age-Related Bone Loss in Mice by Inhibiting Osteoblast Senescence through Smad1-Stat1-P21 Axis." Cell Death Discov 8, no. 1 (2022): 254.

- Zebedee, Z.; Hara, E. Id proteins in cell cycle control and cellular senescence. Oncogene 2001, 20, 8317–8325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T. L., N. Deshpande, V. Kumar, A. G. Gauthier, and U. V. Jurkunas. "Cell Cycle Re-Entry and Arrest in G2/M Phase Induces Senescence and Fibrosis in Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy." Free Radic Biol Med 164 (2021): 34-43.

- Kumari, R.; Jat, P. Mechanisms of Cellular Senescence: Cell Cycle Arrest and Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gire, V. , and V. Dulic. "Senescence from G2 Arrest, Revisited." Cell Cycle 14, no. 3 (2015): 297-304.

- He, L.; Lv, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, B. The prognosis comparison of different molecular subtypes of breast tumors after radiotherapy and the intrinsic reasons for their distinct radiosensitivity. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, ume 11, 5765–5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawale, A.S.; Akopiants, K.; Valerie, K.; Ruis, B.; A Hendrickson, E.; Huang, S.-Y.N.; Pommier, Y.; Povirk, L.F. TDP1 suppresses mis-joining of radiomimetic DNA double-strand breaks and cooperates with Artemis to promote optimal nonhomologous end joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 8926–8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, A.; Gao, H.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, T.; Shi, L.; Wu, X.; Dong, Q.; Sun, X. Silencing Artemis Enhances Colorectal Cancer Cell Sensitivity to DNA-Damaging Agents. Oncol. Res. Featur. Preclin. Clin. Cancer Ther. 2018, 27, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Zhang, S.; Ge, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, S. The dominant negative mutant Artemis enhances tumor cell radiosensitivity. Radiother. Oncol. 2011, 101, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calugaru, V.; Nauraye, C.; Cordelières, F.P.; Biard, D.; De Marzi, L.; Hall, J.; Favaudon, V.; Mégnin-Chanet, F. Involvement of the Artemis Protein in the Relative Biological Efficiency Observed With the 76-MeV Proton Beam Used at the Institut Curie Proton Therapy Center in Orsay. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2014, 90, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, X. Developing a Peptide That Inhibits DNA Repair by Blocking the Binding of Artemis and DNA Ligase IV to Enhance Tumor Radiosensitivity. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 111, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshous, D.; Callebaut, I.; de Chasseval, R.; Corneo, B.; Cavazzana-Calvo, M.; Le Deist, F.; Tezcan, I.; Sanal, O.; Bertrand, Y.; Philippe, N.; et al. Artemis, a Novel DNA Double-Strand Break Repair/V(D)J Recombination Protein, Is Mutated in Human Severe Combined Immune Deficiency. Cell 2001, 105, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, T.; Pannicke, U.; Reisli, I.; Bulashevska, A.; Ritter, J.; Björkman, A.; Schäffer, A.A.; Fliegauf, M.; Sayar, E.H.; Salzer, U.; et al. DCLRE1C(ARTEMIS) mutations causing phenotypes ranging from atypical severe combined immunodeficiency to mere antibody deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 7361–7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodbine, L.; Grigoriadou, S.; Goodarzi, A.A.; Riballo, E.; Tape, C.; Oliver, A.W.; van Zelm, M.C.; Buckland, M.S.; Davies, E.G.; Pearl, L.H. An Artemis polymorphic variant reduces Artemis activity and confers cellular radiosensitivity. DNA Repair 2010, 9, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscariello, M.; Wieloch, R.; Kurosawa, A.; Li, F.; Adachi, N.; Mladenov, E.; Iliakis, G. Role for Artemis nuclease in the repair of radiation-induced DNA double strand breaks by alternative end joining. DNA Repair 2015, 31, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, L.; Gao, H.; Kuang, X.; Xiao, H.; Yang, C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Zhong, Y.; et al. APE1 promotes non-homologous end joining by initiating DNA double-strand break formation and decreasing ubiquitination of artemis following oxidative genotoxic stress. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, R.; Shan, J.; Xie, X.; Wang, C.; Hu, P.; Sun, X. Artemis as Predictive Biomarker of Responsiveness to Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, S.A.; Vymetalkova, V.; Vodickova, L.; Vodicka, P.; Nilsson, T.K. DNA methylation changes in genes frequently mutated in sporadic colorectal cancer and in the DNA repair and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway genes. Epigenomics 2014, 6, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, W.; Ding, Z.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J. Identification and validation of a novel tumor driver gene signature for diagnosis and prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 912620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogana, H.A.; Hurwitz, S.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Geng, H.; Müschen, M.; Bhojwani, D.; Wolf, M.A.; Larocque, J.; Lieber, M.R.; Kim, Y.M. Artemis inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Geng, L.; Wang, H.; Legerski, R.J. Artemis is a negative regulator of p53 in response to oxidative stress. Oncogene 2009, 28, 2196–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C.; Marquardt, S.; Li, F.; Spitschak, A.; Murr, N.; Edelhäuser, B.A.H.; Iliakis, G.; Pützer, B.M.; Logotheti, S. Rewiring E2F1 with classical NHEJ via APLF suppression promotes bladder cancer invasiveness. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labay, E.; Mauceri, H.J.; Efimova, E.V.; Flor, A.C.; Sutton, H.G.; Kron, S.J.; Weichselbaum, R.R. Repurposing cephalosporin antibiotics as pro-senescent radiosensitizers. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 33919–33933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, D., P. Bhanja, R. Riha, G. Sanchez-Guerrero, B. F. Kimler, T. T. Tsue, C. Lominska, and S. Saha. "Auranofin Protects Intestine against Radiation Injury by Modulating P53/P21 Pathway and Radiosensitizes Human Colon Tumor." Clin Cancer Res 25, no. 15 (2019): 4791-807.

- Li, X.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Zhu, F.; Kim, D.J.; Xie, H.; Li, Y.; Nadas, J.; Oi, N.; Zykova, T.A.; et al. Ceftriaxone, an FDA-approved cephalosporin antibiotic, suppresses lung cancer growth by targeting Aurora B. Carcinog. 2012, 33, 2548–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittavanich, P.; Saengwimol, D.; Roytrakul, S.; Rojanaporn, D.; Chaitankar, V.; Srimongkol, A.; Anurathapan, U.; Hongeng, S.; Kaewkhaw, R. Ceftriaxone exerts antitumor effects in MYCN-driven retinoblastoma and neuroblastoma by targeting DDX3X for translation repression. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 18, 918–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.Y.; Park, S.H.; Park, W.H. Anti-Cancer Effects of Auranofin in Human Lung Cancer Cells by Increasing Intracellular ROS Levels and Depleting GSH Levels. Molecules 2022, 27, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.-X.; Liu, P.-P.; Zhang, S.; Yang, M.; Liao, J.; Yang, J.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, W.-Q.; Wen, S.; Huang, P. Elimination of stem-like cancer cell side-population by auranofin through modulation of ROS and glycolysis. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J. H., C. N. Hales, and S. E. Ozanne. "DNA Damage, Cellular Senescence and Organismal Ageing: Causal or Correlative?" Nucleic Acids Res 35, no. 22 (2007): 7417-28.

- Ortiz-Montero, P.; Londoño-Vallejo, A.; Vernot, J.-P. Senescence-associated IL-6 and IL-8 cytokines induce a self- and cross-reinforced senescence/inflammatory milieu strengthening tumorigenic capabilities in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Cell Commun. Signal. 2017, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, H.; Inoue, T.; Kunimoto, H.; Nakajima, K. IL-6-STAT3 signaling and premature senescence. JAK-STAT 2013, 2, e25763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhmoud, J.F.; Woolley, J.F.; Al Moustafa, A.-E.; Malki, M.I. DNA Damage/Repair Management in Cancers. Cancers 2020, 12, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaithamby, A.; Hu, B.; Chen, D.J. Unrepaired clustered DNA lesions induce chromosome breakage in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 8293–8298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

CRISPR screen identifies Artemis (DCLRE1C) as a candidate radiosensitizing target in TNBC. (A) Graph shows the cell doubling time of CRISPR knockout MDA-MB-231 cell lines exposed to either 0 or 4 Gy of RT. Cell doubling was calculated by counting cells at every cell passage for 25 days post-RT. ****= p≤0.0001. (B) Donut chart shows the number of potential radiosensitizing targets and survival related genes appeared in our screen in CRISPR knockout cells exposed to RT. (C) KEGG pathway analysis was performed to identify pathways significantly overrepresented for screen hits. (D) Sigmoid plot shows list of top hit genes identified in our CRISPR screen, whose depletion may sensitize TNBC cells to RT. (E) Using the UALCAN interactive web resource, TCGA-BRCA data was analyzed to examine the expression of NHEJ pathway genes in breast cancer. Expression of DCLRE1C in TNBC patient samples as compared to normal breast tissue samples (p≤0.05 x 10-9). (F) The GEPIA2 web-based tool was used to perform survival analysis on TNBC patients with high and low DCLRE1C (Artemis) expression. A lower expression of DCLRE1C was associated with better overall survival as compared to patients with high DCLRE1C expression.

Figure 1.

CRISPR screen identifies Artemis (DCLRE1C) as a candidate radiosensitizing target in TNBC. (A) Graph shows the cell doubling time of CRISPR knockout MDA-MB-231 cell lines exposed to either 0 or 4 Gy of RT. Cell doubling was calculated by counting cells at every cell passage for 25 days post-RT. ****= p≤0.0001. (B) Donut chart shows the number of potential radiosensitizing targets and survival related genes appeared in our screen in CRISPR knockout cells exposed to RT. (C) KEGG pathway analysis was performed to identify pathways significantly overrepresented for screen hits. (D) Sigmoid plot shows list of top hit genes identified in our CRISPR screen, whose depletion may sensitize TNBC cells to RT. (E) Using the UALCAN interactive web resource, TCGA-BRCA data was analyzed to examine the expression of NHEJ pathway genes in breast cancer. Expression of DCLRE1C in TNBC patient samples as compared to normal breast tissue samples (p≤0.05 x 10-9). (F) The GEPIA2 web-based tool was used to perform survival analysis on TNBC patients with high and low DCLRE1C (Artemis) expression. A lower expression of DCLRE1C was associated with better overall survival as compared to patients with high DCLRE1C expression.

Figure 2.

Loss of function or pharmacological inhibition of Artemis leads to anti-proliferative effects and radiosensitization in TNBC. (A) Left: Representative image showing the colonies formed in sgControl and sgDCLRE1C#2 & sgDCLRE1C#3 MDA-MB-231 cell lines exposed to different doses of radiation (0, 1, 2 and 4 Gy). Right: The Bar graph shows the colony-forming efficiency of sgControl and sgDCLRE1C#2 & sgDCLRE1C #3 MDA-MB-231 cell lines exposed to different doses of RT. *= p≤0.05, ****= p≤0.0001. (B-E) MDA-MB-231 and SUM-159 TNBC cells were grown in colony-forming assay conditions and treated with different doses of the drug in the absence or presence of ID50 dose (2 Gy for MDA-MB-231, 5 Gy for SUM159) of RT. Ceftriaxone (B&C) and auranofin (D&E) showed a dose-dependent decrease in colony forming ability and enhanced effects RT in TNBC cells. *= <0.05, **=0.01, ***=0.001, ****=0.0001.

Figure 2.

Loss of function or pharmacological inhibition of Artemis leads to anti-proliferative effects and radiosensitization in TNBC. (A) Left: Representative image showing the colonies formed in sgControl and sgDCLRE1C#2 & sgDCLRE1C#3 MDA-MB-231 cell lines exposed to different doses of radiation (0, 1, 2 and 4 Gy). Right: The Bar graph shows the colony-forming efficiency of sgControl and sgDCLRE1C#2 & sgDCLRE1C #3 MDA-MB-231 cell lines exposed to different doses of RT. *= p≤0.05, ****= p≤0.0001. (B-E) MDA-MB-231 and SUM-159 TNBC cells were grown in colony-forming assay conditions and treated with different doses of the drug in the absence or presence of ID50 dose (2 Gy for MDA-MB-231, 5 Gy for SUM159) of RT. Ceftriaxone (B&C) and auranofin (D&E) showed a dose-dependent decrease in colony forming ability and enhanced effects RT in TNBC cells. *= <0.05, **=0.01, ***=0.001, ****=0.0001.

Figure 3.

Loss of Artemis in combination with RT prolonged survival of mouse xenografts. The sgControl and sgDCLRE1C#2 cells were exposed to either no radiation (0 Gy) or 2 Gy RT and injected (viable cells) into the mammary fat pads of 6-8-week-old female NOD/SCID mice. (A) Kaplan-Maier survival curves show the time taken for the mice injected with sgControl_0Gy, sgControl_2Gy, sgDCLRE1C#2_0Gy and sgDCLRE1C #2_2Gy to reach the humane endpoint. *= p≤0.01, **= p≤0.005, ***= p≤0.001. (B) Graph shows the tumor doubling time of 10.1, 39.9, 14.3 & 53.7 days in sgControl_0Gy, sgControl_2Gy, sgDCLRE1C#2_0Gy and sgDCLRE1C#2_2Gy MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively.

Figure 3.

Loss of Artemis in combination with RT prolonged survival of mouse xenografts. The sgControl and sgDCLRE1C#2 cells were exposed to either no radiation (0 Gy) or 2 Gy RT and injected (viable cells) into the mammary fat pads of 6-8-week-old female NOD/SCID mice. (A) Kaplan-Maier survival curves show the time taken for the mice injected with sgControl_0Gy, sgControl_2Gy, sgDCLRE1C#2_0Gy and sgDCLRE1C #2_2Gy to reach the humane endpoint. *= p≤0.01, **= p≤0.005, ***= p≤0.001. (B) Graph shows the tumor doubling time of 10.1, 39.9, 14.3 & 53.7 days in sgControl_0Gy, sgControl_2Gy, sgDCLRE1C#2_0Gy and sgDCLRE1C#2_2Gy MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively.

Figure 4.

RNA-Seq analysis identifies differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and enriched pathways upon Artemis depletion. (A) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) plot shows positively enriched gene sets upon Artemis depletion relative to control. (B) Volcano plot shows DEGs in Artemis deficient cells compared to control. (C) Dot plot shows significantly overrepresented pathways in MDA-MB-231 cells lacking Artemis as compared to control. (D) Bar graph shows expression of pro- and anti-tumorigenic genes in Artemis-deficient cells as compared to control.

Figure 4.

RNA-Seq analysis identifies differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and enriched pathways upon Artemis depletion. (A) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) plot shows positively enriched gene sets upon Artemis depletion relative to control. (B) Volcano plot shows DEGs in Artemis deficient cells compared to control. (C) Dot plot shows significantly overrepresented pathways in MDA-MB-231 cells lacking Artemis as compared to control. (D) Bar graph shows expression of pro- and anti-tumorigenic genes in Artemis-deficient cells as compared to control.

Figure 5.

Artemis depletion enhances RT response via activation of cellular senescence related genes. (A) GSEA reveals positive enrichment of IL6/JAK/STAT3, inflammatory response, TNFA/NFκB and complement pathway gene sets in radiation treated, Artemis knockout cells relative to non-irradiated control. (B) Dot plot shows overrepresented signaling pathways under Artemis knockout condition combined with RT. (C) Volcano plot shows the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in radiation treated, Artemis depleted cells compared to non-irradiated control. (D) Heatmap depicting perturbation of genes related to cellular senescence in sgDCLRE1C_0Gy vs sgControl_0Gy, sgDCLRE1C_2Gy vs sgControl_0Gy, and sgDCLRE1C_2Gy vs sgControl_2Gy. Shades of red indicate significantly upregulated genes, blue indicates significantly downregulated gene, and the white represents non-significant changes.

Figure 5.

Artemis depletion enhances RT response via activation of cellular senescence related genes. (A) GSEA reveals positive enrichment of IL6/JAK/STAT3, inflammatory response, TNFA/NFκB and complement pathway gene sets in radiation treated, Artemis knockout cells relative to non-irradiated control. (B) Dot plot shows overrepresented signaling pathways under Artemis knockout condition combined with RT. (C) Volcano plot shows the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in radiation treated, Artemis depleted cells compared to non-irradiated control. (D) Heatmap depicting perturbation of genes related to cellular senescence in sgDCLRE1C_0Gy vs sgControl_0Gy, sgDCLRE1C_2Gy vs sgControl_0Gy, and sgDCLRE1C_2Gy vs sgControl_2Gy. Shades of red indicate significantly upregulated genes, blue indicates significantly downregulated gene, and the white represents non-significant changes.

Figure 6.

Loss of Artemis expression enhances radiation response via induction of G2/M arrest and cellular senescence. Cell cycle analysis was performed to assess the consequence of Artemis knockout, alone or in combination with RT. (A) Loss of Artemis combined with RT resulted in a significant increase in G2/M arrest compared to control, RT alone and Artemis knockout alone condition at 24 hours. (B) Immunoblot (left) and densitometric analysis (right) shows a significant increase in IL6 protein levels in Artemis knockout cells, alone and in combination with RT. (C) Representative image (left) shows positive β-galactosidase staining in sgControl and sgDCLRE1C MDA-MB-231 cells. Bar graph (right) shows percentage of β-galactosidase positive cells in control, and Artemis knockout cells, alone or in combination with RT. *=<0.05, **=<0.01, ***=<0.001, ****=0.0001. Scale = 100µm.

Figure 6.

Loss of Artemis expression enhances radiation response via induction of G2/M arrest and cellular senescence. Cell cycle analysis was performed to assess the consequence of Artemis knockout, alone or in combination with RT. (A) Loss of Artemis combined with RT resulted in a significant increase in G2/M arrest compared to control, RT alone and Artemis knockout alone condition at 24 hours. (B) Immunoblot (left) and densitometric analysis (right) shows a significant increase in IL6 protein levels in Artemis knockout cells, alone and in combination with RT. (C) Representative image (left) shows positive β-galactosidase staining in sgControl and sgDCLRE1C MDA-MB-231 cells. Bar graph (right) shows percentage of β-galactosidase positive cells in control, and Artemis knockout cells, alone or in combination with RT. *=<0.05, **=<0.01, ***=<0.001, ****=0.0001. Scale = 100µm.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).