1. Introduction

Often using over 50% of their annual electricity to space cooling and heating [5], high-rise commercial buildings are responsible for most of the global energy consumption and carbon emissions, due to solar heat gains through the façade [

6,

7,

8] causing an increase in climate change. Traditional static facades are increasingly being replaced by adaptive building envelopes that can adapt and respond dynamically to the external environment to enhance the building energy performance and to maintain indoor comfort [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. ETFE (Ethylene Tetrafluoroethylene), a lightweight, transparent fluoropolymer, has been used in the construction industry ranging from long-span roofs to complete dynamic facade systems. Many studies have shown how this material can significantly save energy year-round by modulating insulation and solar heat gain. As the world continues to seek innovative and sustainable solutions to address the various challenges, advanced polymers, especially auto-healing material, have gained significant interest in the field of construction. Such innovative and unique material with enhanced mechanical properties, with greater resistance to environmental factors like temperature, light, humidity, and UV radiation, when used as Responsive Kinetic Skins, adds a layer of resilience and sustainability, improving the building energy performance and urban built environment. In the need of improving the Energy efficiency in the design and the construction of the building.

In India, through codes and standards, the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) has emphasised the importance of high-performance building envelopes by developing the Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC) [1], launched by the Ministry of Power in 2007. ECBC sets minimum energy performance standards and guidelines for commercial building components including envelopes, HVAC, lighting, and others. Alongside ECBC, international standards like ASHRAE 90.1 [

2,

4] for energy performance and ASHRAE 55 [4]for thermal comfort provide guidelines to ensure buildings meet efficiency and comfort criteria. The ECBC encourages the architects, designers and engineers to use advanced building performance simulation (BPS) tools such as Design Builder [

5] during the design process to predict a building’s energy consumption and comfort outcomes under various design scenarios, enabling data-driven decisions on materials and facade strategies for sustainable and energy efficient development.

Following these guidelines, a simulation-based study to evaluate these two smart materials as a Responsive kinetic facade was conducted. A hypothetical building model (benchmarking a prototypical office building) was created in Design Builder, with defined geometry, location, and composite climate data [

6,

7]. First, a baseline case with a conventional static facade having no external shading or dynamic elements was simulated to establish reference performance for energy consumption and indoor comfort. This base model was calibrated to meet ECBC’s and ASHRAE guidelines and basic requirements and serves as the reference point. Next, two responsive facade scenarios were implemented on the same model using ETFE and Auto Heal as the adaptive materials. In both cases, the facade was assumed to be capable of reacting to external conditions (for example, by changing its transparency, thermal resistance, or aperture as needed) to modulate heat gain and loss. Integrating the study with the established standards and simulating real-world operational conditions, this research paper provides a detailed evaluated analysis of the smart materials as responsive kinetic facades for the building energy efficiency and indoor environment quality. By aligning the study with established standards, this research provides a rigorous evaluation of smart materials in kinetic facades.

The following sections detail the literature review of ETFE focusing on the strengths and limitations as a smart material for kinetic facades, the introduction of Auto Heal, a self-healing polymer, into the domain of responsive facades, exploring its potential for thermal performance, the methodology of the simulations, the performance metrics used for evaluation, the results of the comparative analysis, and the implications of these findings for sustainable facade design for the energy efficiency of the buildings and urban built environment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. ETFE as an Adaptive Material

Since the mid-20th century, because of the cost-effectiveness, lightweight nature, and versatility, plastics have emerged as one of the most widely utilized materials worldwide. In the construction industry, they have remarkably replaced traditional materials such as wood and steel. Since its synthesis by DuPont in the 1940s, Ethylene Tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE), a plastic polymer, has gained attention as a smart material for sustainable architectural and construction applications [

18]. Its innovative characteristics, including high light transmission, thermal insulation, and flexibility in design, have made it an advisable choice for iconic projects such as the Allianz Arena in Munich, the National Aquatics Center in Beijing and the Media-TIC building in Barcelona [

7,

17,

18]. Studies have demonstrated that ETFE can reduce energy consumption by up to 40% compared to glass and lower construction costs by 24-70% [7]. However, it often lacks comprehensive analyses of its long-term performance under extreme environmental conditions, such as shifting temperatures [

3,

4,

19] . Additionally, a lack of detailed analysis of its overall environmental footprint, including production and end-of-life considerations [20]. Furthermore, while ETFE is celebrated for its sustainability and recyclability, there is a notable absence of technical data on its thermal and acoustic performance, such as U-values, thermal conductivity, and acoustic properties [

5,

11,

21,

22,

23] . Additionally, there is a lack of comprehensive comparison between ETFE and other adaptive facade materials specifically for multistory applications [

9,

10,

23,

24] . The potential of ETFE extends beyond its current applications, particularly in the context of adaptive facades for multistorey buildings. However, research in this area remains limited. For example, one study does not thoroughly investigate occupant interaction, user comfort, and control mechanisms for adaptive ETFE facades in multistorey structures [5]Furthermore, discussions on the current state of building codes and standards for adaptive ETFE facades are insufficient, which is critical for their widespread adoption [25].

There is a growing demand for using ETFE as adaptive smart material, several research and implementation gaps remain. There is limited information on the maintenance and repair requirements needed for ETFE building skins [25]. Additionally, more comprehensive research is needed on the visual perception of ETFE adaptive systems [

12,

13]. For validating the effectiveness of the application of ETFE as façade material a detailed quantitative data on the energy performance and occupant comfort improvements in different climates is required [26]. To evaluate, researchers have employed advanced energy simulation tools such as Rhinoceros, Grasshopper, Ladybug, Honeybee, and Radiance to predict the building performance [23]. However, the study primarily focuses on daylighting and energy performance, investigation into thermal discomfort, hours, melting range, light transmission, and K-value, remains unexplored [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. However, the use of software like Design Builder to calculate total discomfort hours and compare ETFE with other materials would have provided a more comprehensive understanding of its potential [

42,

43] . ETFE, when used as Responsive façades, can improve the building energy performance and indoor air quality when they interact with the external weather conditions [

44,

45,

46]. However, there is insufficient data on the integration of ETFE with other smart building technologies, such as nanomaterials, which could further enhance its performance [47]. One of the key points that needs to be addressed is the validation of simulation results with real world scenarios [48]. While ETFE has proved to be a favourable adaptive material to create sustainable and energy efficient buildings. There is the need for further research on how effectively ETFE can be used as kinetic responsive facades for multistory buildings responding to changing environmental conditions, leading to more sustainable, energy-efficient structures and better urban built environment.

2.2. Auto Heal as an Adaptive Material

2.2.1. Self-Healing Materials in Facades

A transformative advancement in material science, where Self-healing materials are moving from a theoretical concept to an imminent reality. There is a change in thinking where engineered materials including polymers, metals, ceramics, and composites possess the built-in potential to self-repair the damage, thereby improving their durability, functionality, and longevity [

49,

50] . This new ability provides the scope for the Architects, designers, and researchers to explore the potential for innovative material design to resolve long standing limitations in structural integrity and sustainability [51]. There is a transformation in the design and function of the building facades with application of self-healing materials. For example, bacterial concrete is an innovative solution that reduces carbon emissions, minimizes cracks, and improves durability [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. To prevent water ingress and structural damage, self-healing concrete can close micro -cracks, thereby lowering the maintenance expenses and improving the quality performance of the structure [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. In architectural applications, self-healing coatings can repair minor degradation on the façade surfaces, preserving the underlying material used. Despite these developments, implementation of these materials into construction practices, achieving an optimization in terms of cost, performance, and sustainability, and their response to varying environmental conditions has always been a challenge.

2.2.2. Polymer Materials in Facades

Due to their lightweight, durable, and versatile nature, polymers like PMMA, PVC, and polycarbonate are widely used in building facades. Self-healing polymer materials, a recent development in the building construction industry, can autonomously repair damage and extend the lifespan of building exteriors [

66,

67,

68]. For instance, smart polymeric coatings, when used with natural additives like tung oil and linalyl acetate, have shown improved ability to repair microcracks, improving the durability of the facade. A notable advancement includes polymer-clay hybrid materials capable of self-repair upon contact with water. This development provides an eco-friendly approach to preserving facade durability across diverse environmental conditions. Additionally, to seal cracks and prevent water damage, a polymer cement-based coating with ion chelators can form calcite crystals. These evolutions using computational simulations validate the efficiency of these materials and demonstrate the potential of self-healing polymers in creating more sustainable and resilient architectural designs [

57,

69,

70].

2.2.3. Auto-Healing Materials with Ion-Dipole Interactions

Self-healing materials can also be created using dynamic supramolecular interactions, such as ion-dipole bonds. These interactions, which occur between charged ions and polar molecules, create strong, reversible bonds that allow materials to repair themselves and adapt to environmental changes [

71,

72,

73]. Both extrinsic methods (e.g., encapsulation, hollow fibers) and intrinsic methods (e.g., reversible covalent bonds, hydrogen bonding) have been explored by researchers to achieve these properties [

74,

75,

76] . A significant development is a bio-inspired material that mimics the self-healing abilities of Wolverine, a Marvel comic character. This material is transparent, stretchable, and can repair itself when damaged, making it ideal for applications in soft robotics, wearable electronics, and flexible displays [

77,

78]. Advanced auto-healing materials can respond to environmental changes, which have helped in overcoming challenges in material science and building technology. These materials offer several benefits, including enhanced durability, responsiveness to factors like temperature, and self-heal when electric fields are activated. Integrating Auto heal with kinetic transformation strategies can hold an extensive potential for improving the sustainability, urban built environment, and energy performance of the building when used as responsive kinetic facades.

2.2.4. Research Gap Analysis

In summary, numerous studies on ETFE as a responsive adaptive façade material focuses on its sustainability and energy efficiency. Significant issues remain as far as long -term performance under various climatic conditions. Additionally, the integration of self-healing technologies with ETFE remains uninvestigated. There is also a lack of comparative analysis between ETFE and other adaptive façade materials. Further research is required to explore their combined impacts on the thermal comfort of the occupants, building energy efficiency and the overall sustainable built environment. However, the application of advanced, innovative self-healing material offers a novel opportunity to develop the functionality and durability of the adaptive façades.

3. Methodology

3.1. Simulation Setup and Tools

An extensive simulation was conducted using whole-building energy modeling to evaluate each facade material under uniform conditions [

79,

80,

81,

82,

83] . Design Builder (with an Energy Plus engine) software was chosen for its advanced capabilities in assessing the building energy performance [

83,

84] . This tool is well-established for predicting annual energy consumption, thermal comfort indices, and daylighting, aligning with best practices encouraged by ECBC and ASHRAE standards [5]. Building performance simulation is extensively utilised to optimise building envelopes and systems. This technology enables the assessment of different facade materials' impact on energy efficiency and occupant comfort without the need for physical prototypes [

85,

86,

87] .

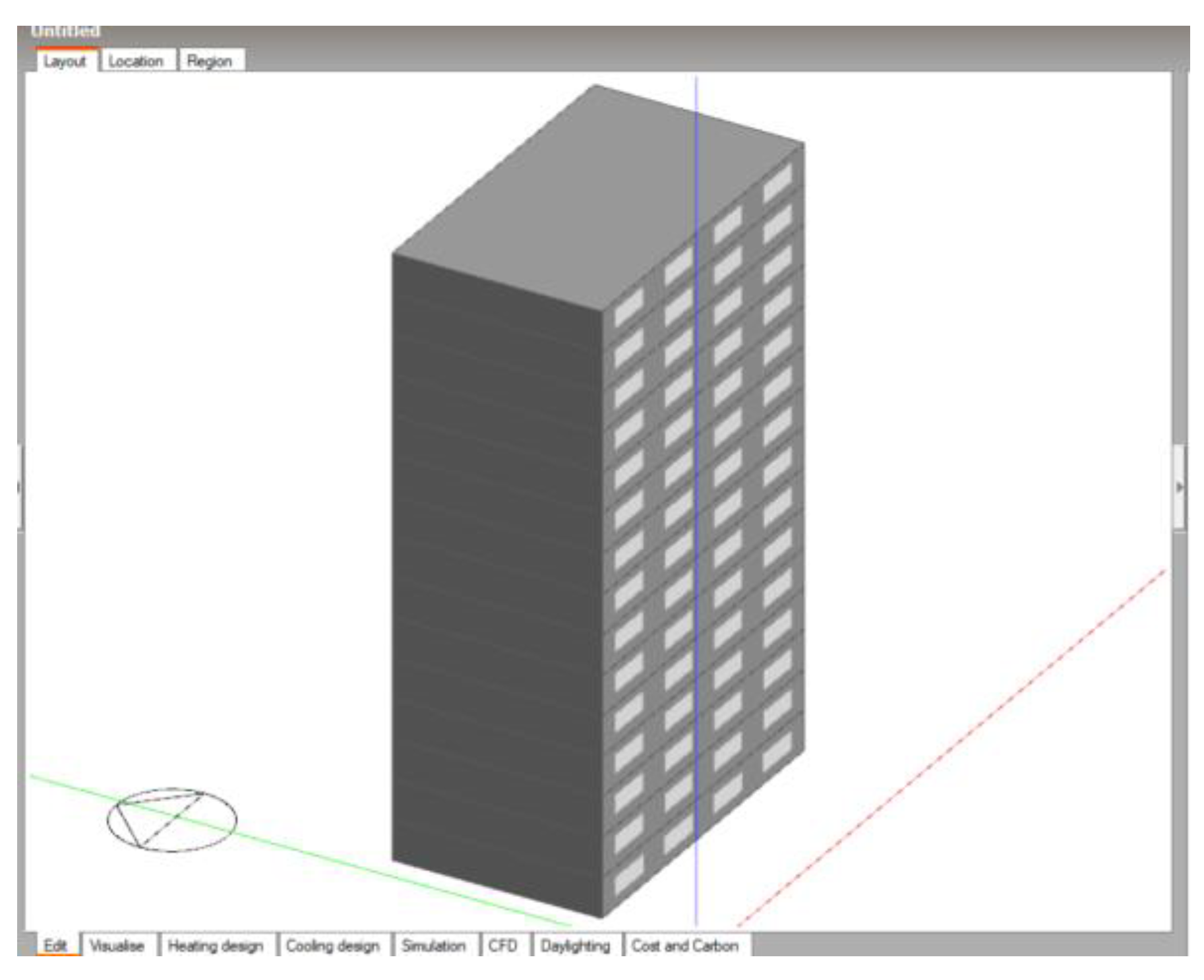

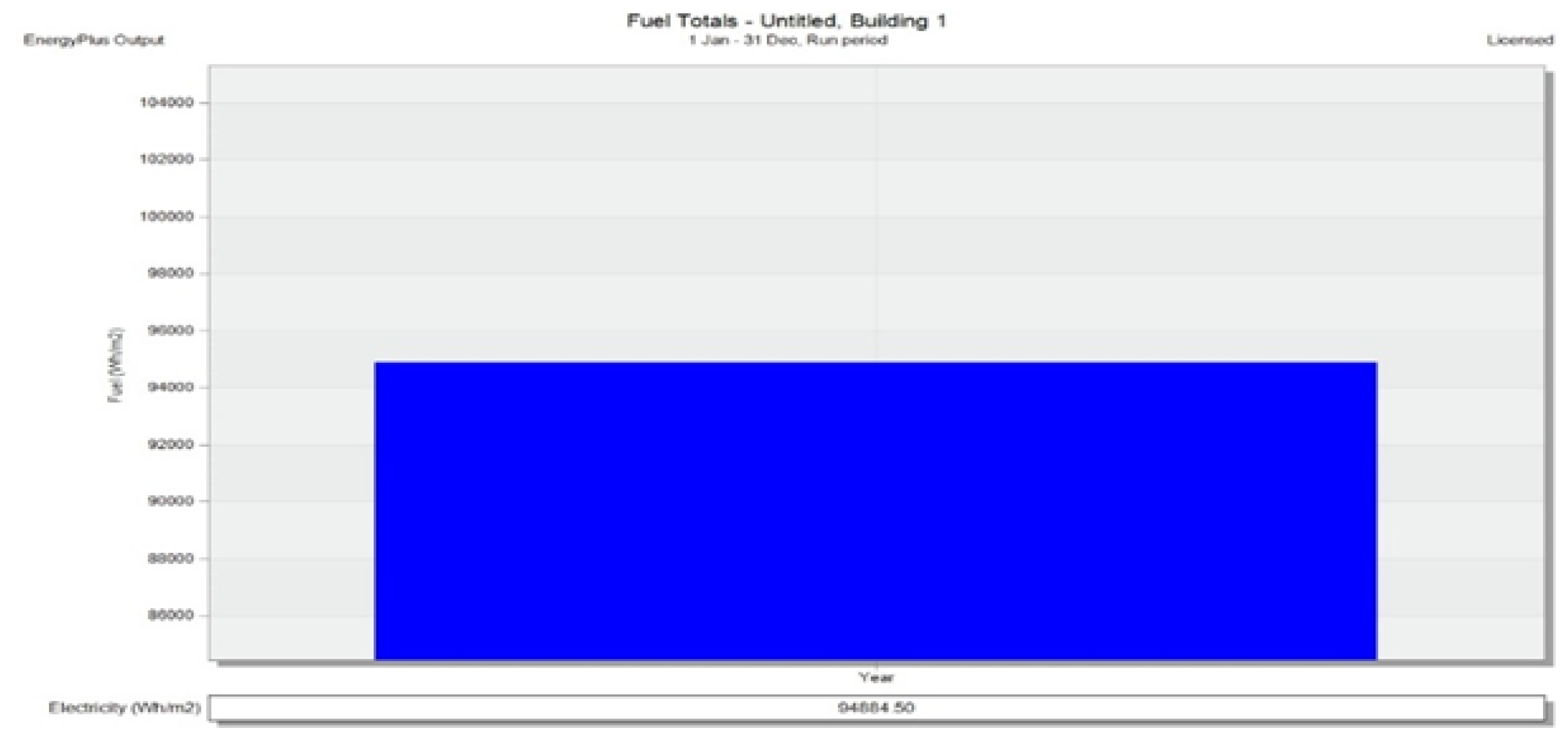

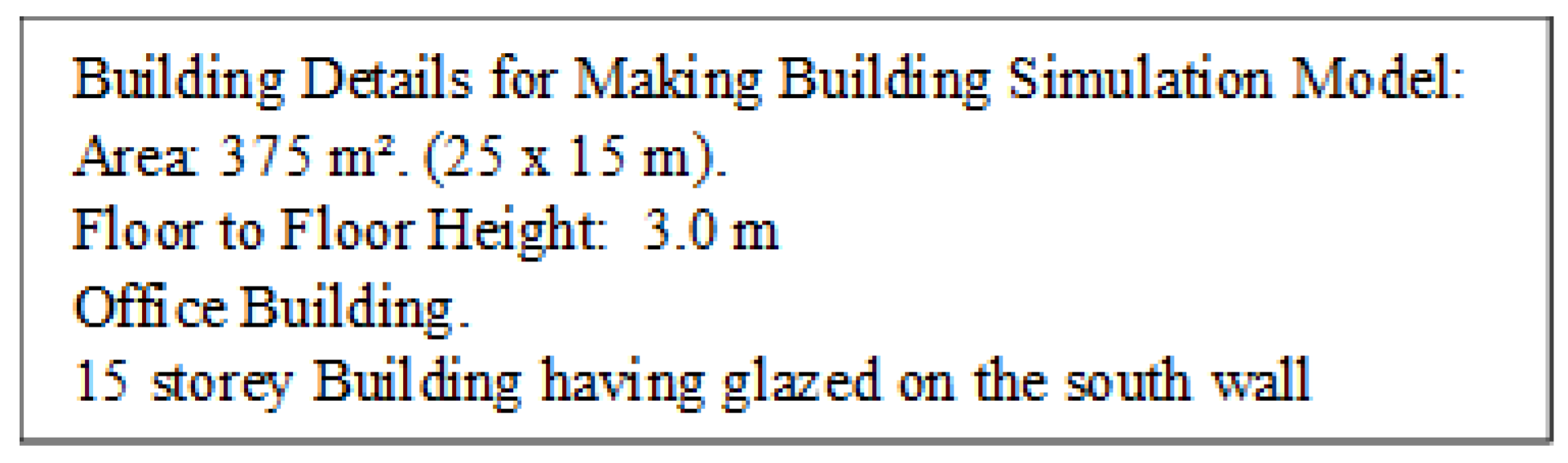

Figure 1 shows the baseline building model that was utilised for all simulations. The office block, located in Jaipur, Rajasthan, India, is in a composite climate region with hot summers and cool winters. The geometry and orientation of the model were maintained consistently across all simulation runs. Key building parameters (floor area, number of floors, occupancy density, internal loads, etc.) Standard reference models [6] were utilized and modified to accommodate the local climate [7]. The building envelope in the base case consisted of typical construction materials meeting ECBC 2017 prescriptive requirements [1] for U-values and solar heat gain coefficients. In the base case, no shading devices or kinetic features were used, providing a clear performance benchmark under static facade conditions [

88,

89].

For climate data, an appropriate weather file (in Energy Plus EPW format) representing the composite climate was used. All simulations for the different facade scenarios used the same weather data to ensure comparability. The HVAC system in the model was configured to be a standard efficient system (e.g., variable air volume with economizer) sized according to the building load. Internal thermostat setpoints and operation schedules were kept consistent in all cases. This uniform setup isolates the effect of the facade material as the primary variable.

3.2. Façade Scenarios

After running the base case simulation to obtain a performance baseline, we introduced responsive facade systems in two scenario runs:

1. ETFE facade: The building’s external skin is replaced or overlaid with an ETFE-based kinetic facade. In simulation terms, this was represented by modifying the envelope properties to mimic ETFE foil cushions. ETFE is highly transparent with relatively low thermal insulating value as a single layer, but in a cushion system (multiple layers of ETFE with air cavities) its effective U-value can be much lower [

90,

91,

92,

93,

94]. In our model, the ETFE facade was assumed to dynamically adjust (for instance, by inflating or deflating cushions, or by deploying shading within the cavity) in response to outside conditions. This setup aims to reduce solar gains on hot days and increase insulation on cold days, following principles observed in prior ETFE dynamic facade research.

2. Auto-heal facade: The building facades use Auto heal, a self-healing material, as the kinetic layer. The purpose of including Auto Heal is to test if a material with self-repairing capability and presumably good insulation can outperform ETFE in maintaining comfort and reducing energy demand. To characterize the thermal stability and composition of the material, TGA (Thermogravimetric analysis) was conducted under various temperature conditions up to 600 °C by METS (Middle East Testing Services) Laboratories, Ajman, UAE [

95,

96].

In both adaptive scenarios, the control strategy for the kinetic facade was simplified in the simulation: the facade was set to fully deploy its maximum shading/insulating state during periods of excessive solar gain (to minimize cooling load), and to retract or become maximally transparent during cold periods or when solar heat is beneficial (to reduce heating load). This on/off control approximates a responsive system, provides a reasonable estimate of potential performance improvement. By keeping the control logic consistent for both ETFE and Auto Heal, we ensured a fair comparison between the materials.

3.3. Performance Metrics

To thoroughly compare the facade options, several key performance metrics from the simulation results, which were analysed:

Energy Use per year (Fuel Consumption, Wh/m²): It provides the total building energy consumption per unit floor area, mainly for HVAC (cooling and heating) and fans. It is expressed in watt-hours per square meter for the analysis period. Lower values indicate better energy efficiency of the building. The focus in this study is on the fuel consumption for HVAC, since facade changes mostly impact heating/cooling loads.

Discomfort Hours: The total number of hours in an entire year when the temperature inside falls beyond a specified comfort range. In this case the comfort range is determined by standard criteria such as the acceptable range of PMV/PPD per ASHRAE 55 [

4]. Lesser discomfort hours depict the building maintains a comfortable environment for occupants most of the time, indicating an effective facade and HVAC design.

Fanger Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied (PPD, %): This index predicts the percentage of users who will experience thermal discomfort in the indoor environment. It is derived from the Fanger comfort model and related to the PMV. A less PPD percentage indicates a higher fraction of thermally satisfied users. For instance, PPD = 25% means one in four people may be dissatisfied on average [97].

Fanger Predicted Mean Vote (PMV): The PMV is an indicator of the average thermal sensation on a scale from -3 (cold) to +3 (hot), with 0 being neutral. It takes several factors like air temperature, radiant temperature, humidity, air speed, metabolic rate, and clothing level. Values close to 0 (between -0.5 and +0.5) are mainly considered comfortable [

4]. In this research, a PMV slightly above 0 indicates a tendency toward warmth. Lower absolute PMV (closer to zero) signifies better thermal comfort.

The above-mentioned metrics were calculated for every simulation scenario to provide a detailed picture: energy performance (via annual Wh/m²) and occupant comfort (via discomfort hours, PPD, PMV) [

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103]. All other variables being equal, a facade that yields lower energy use and improved comfort indices is considered superior. In addition to this, we also note the percentage savings in energy use for the adaptive cases relative to the base case, to quantify improvement.

4. Analysis and Findings

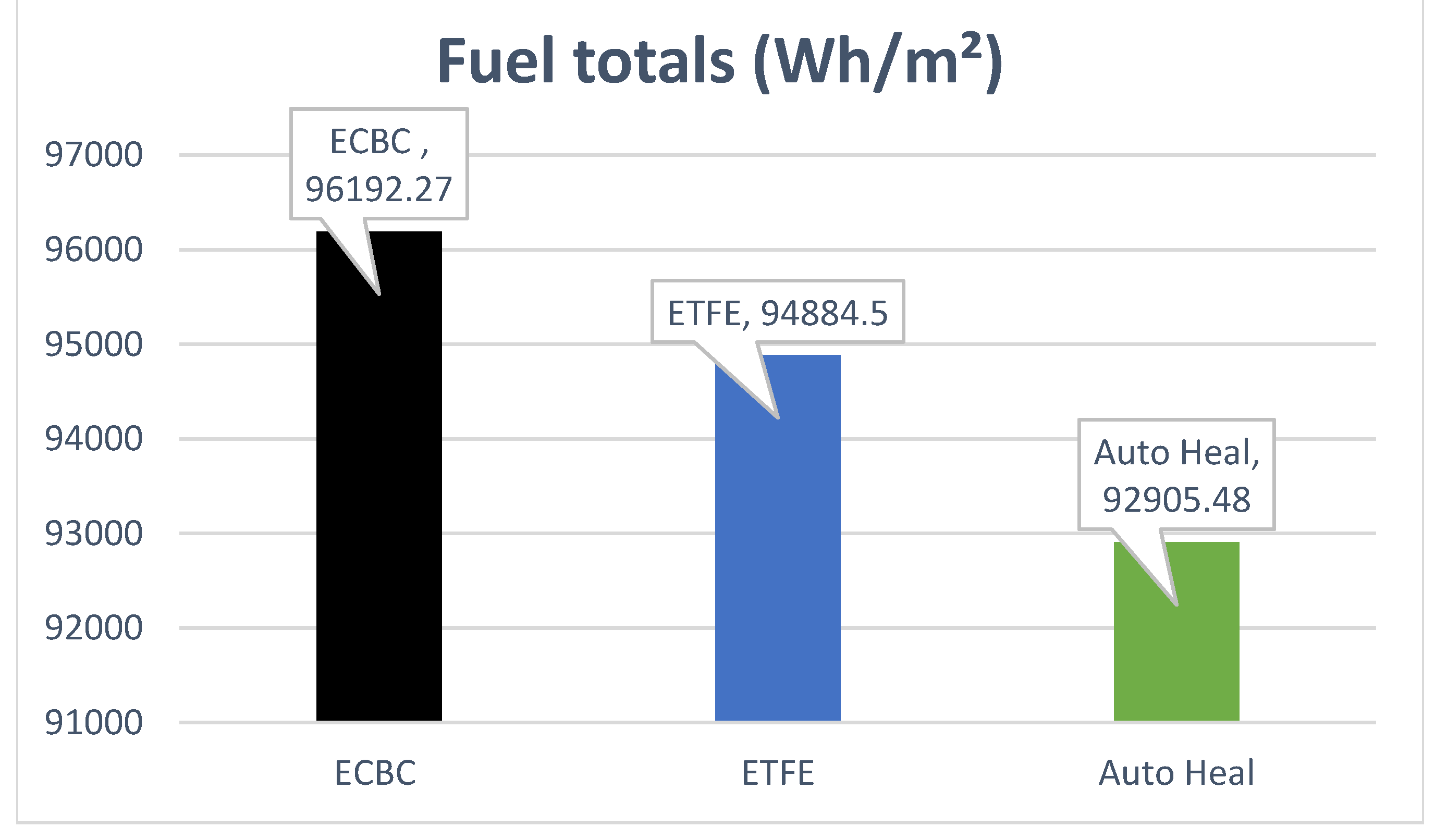

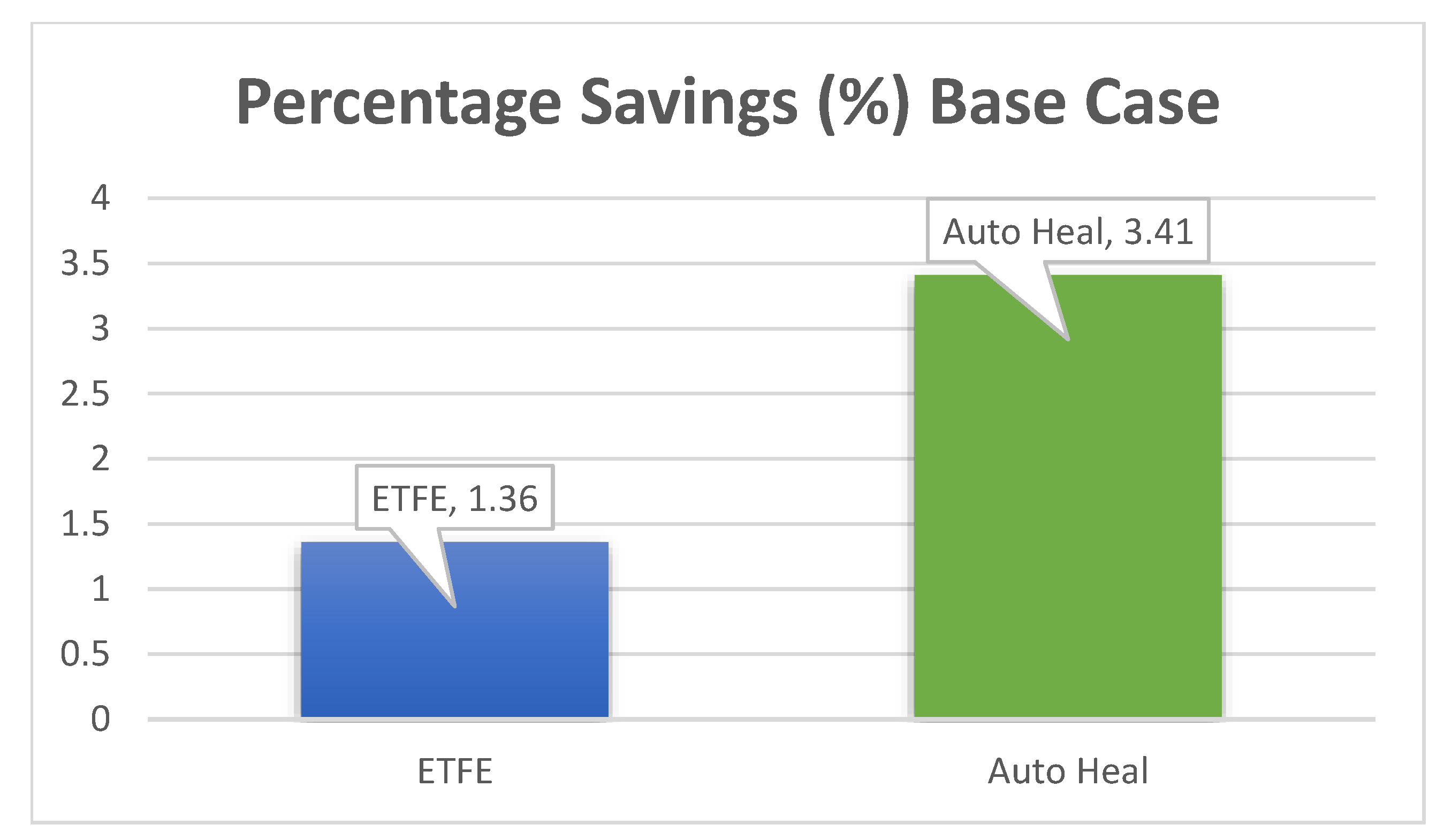

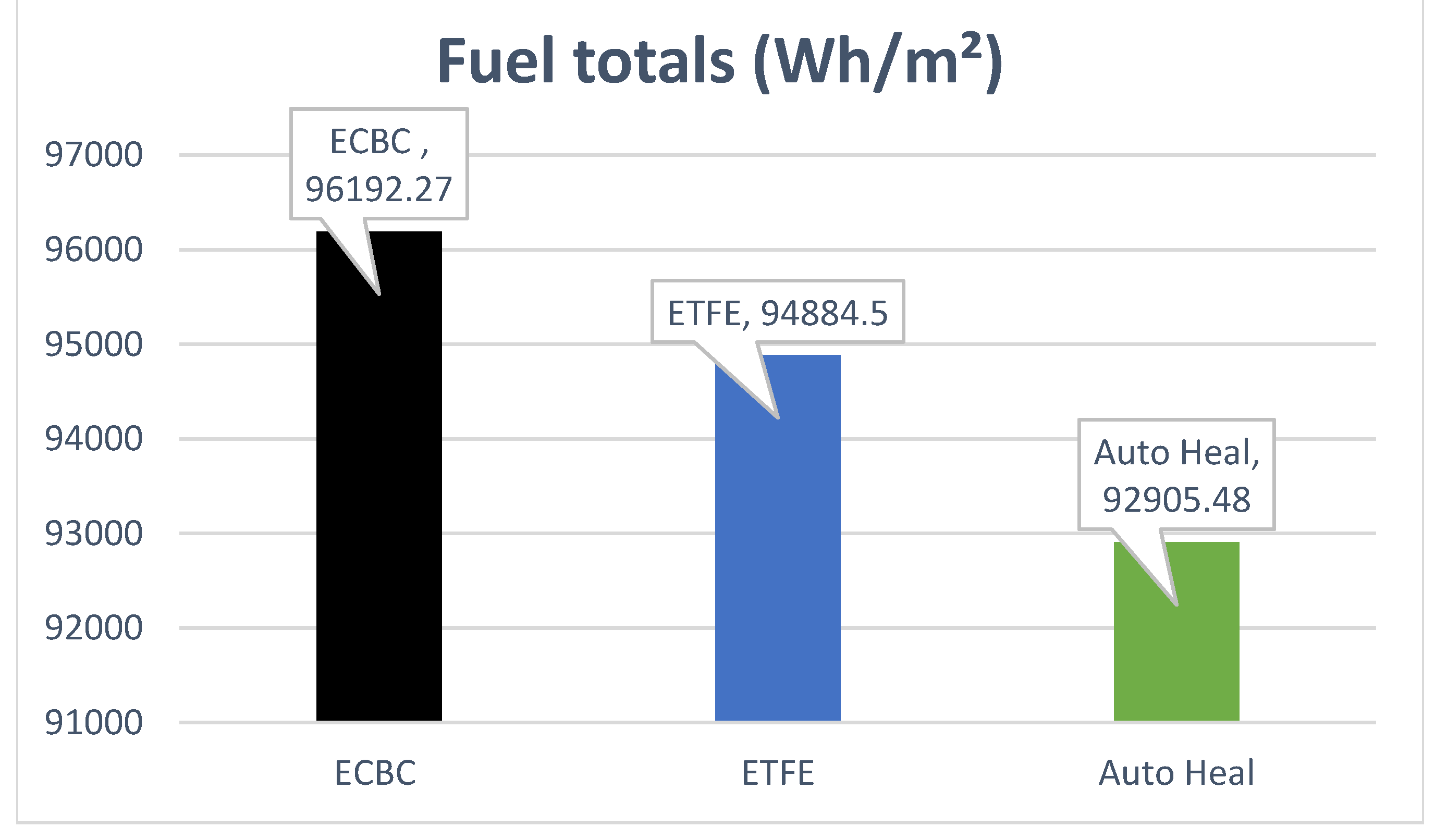

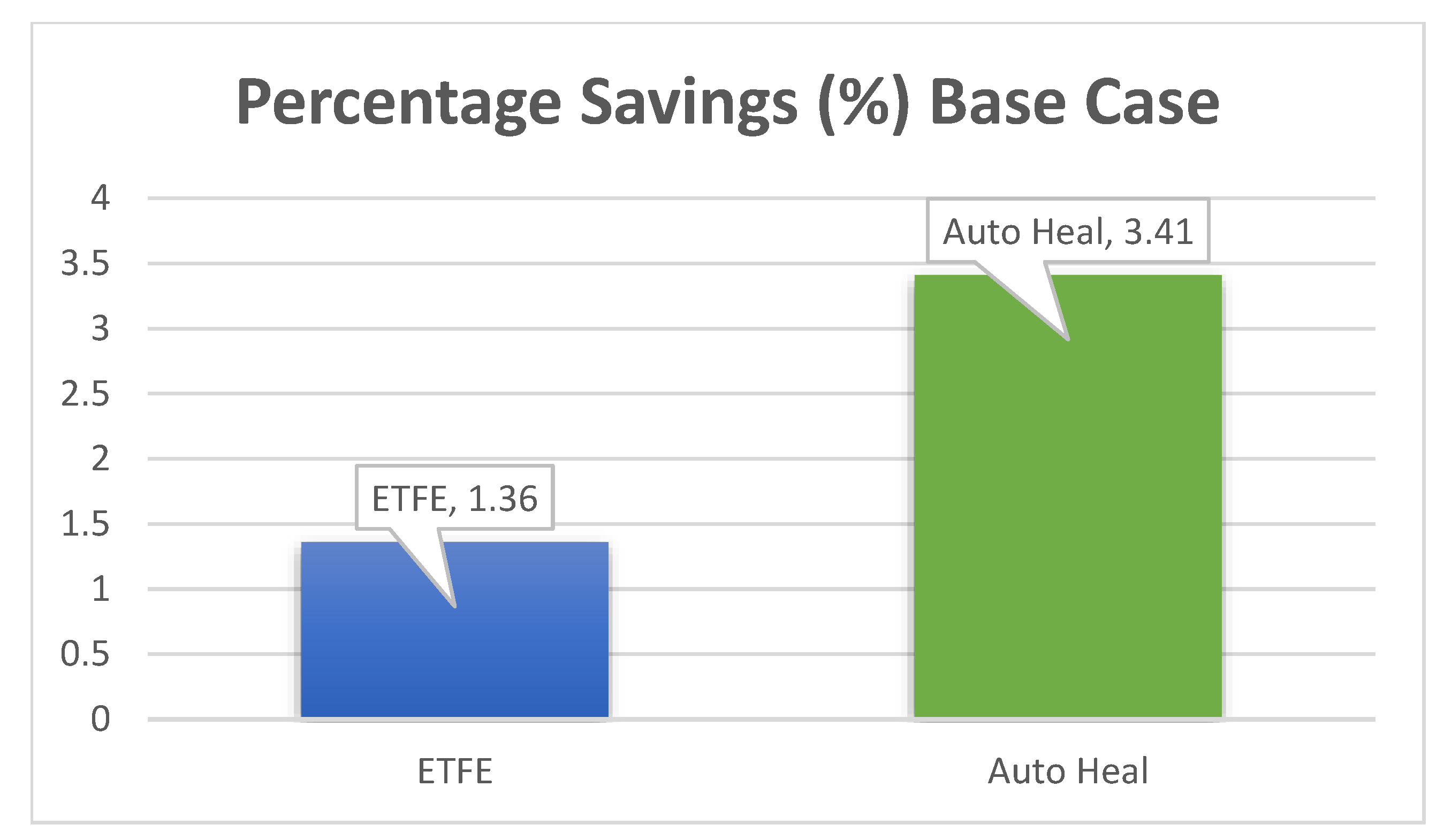

After running the simulations, the performance of the two smart facade materials, ETFE and Auto Heal, was compared against the ECBC-compliant base case. The subsequent discussion interprets the key findings shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The total fuel consumption and the percentage of energy savings in Graph 1 and Graph 2.

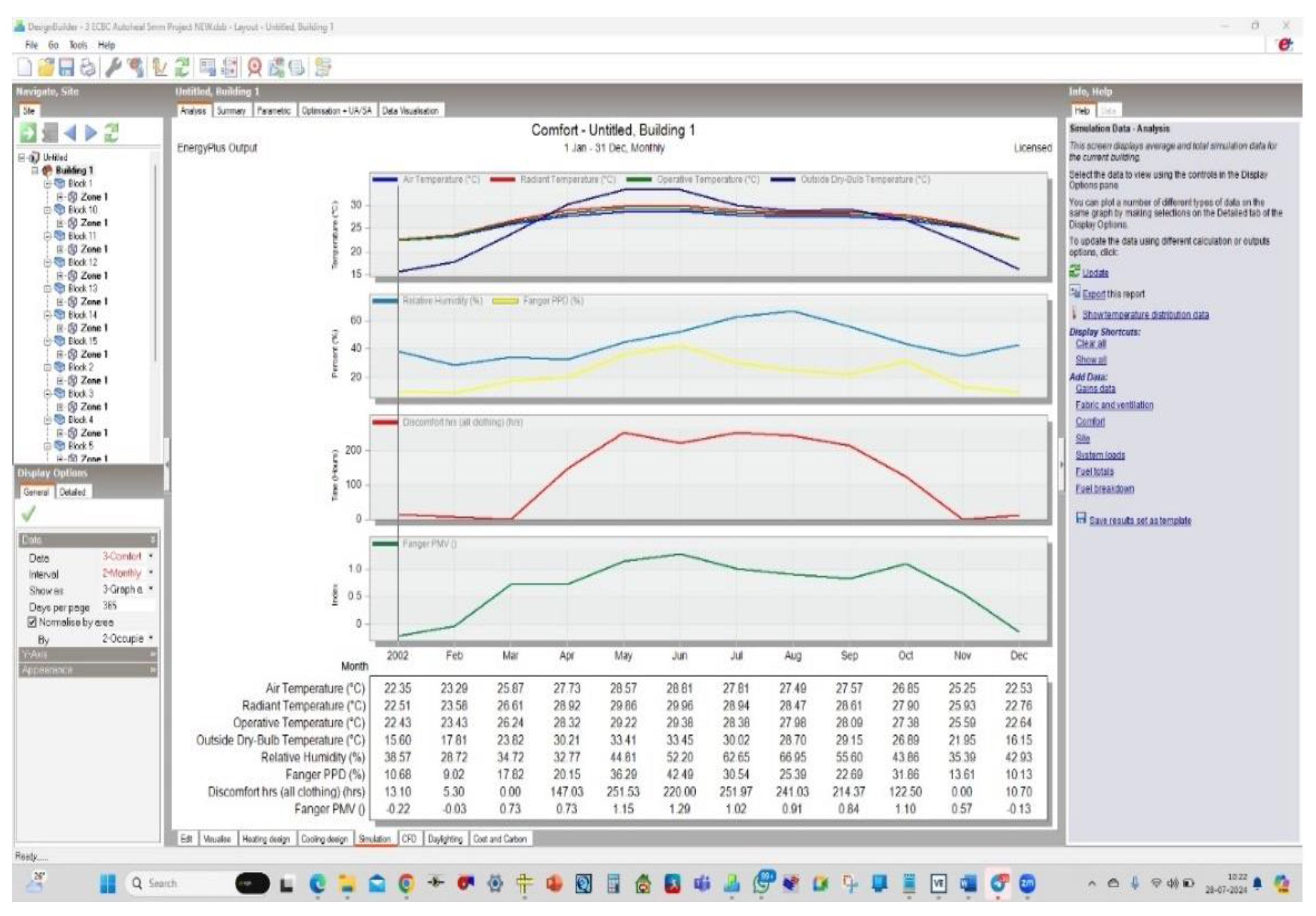

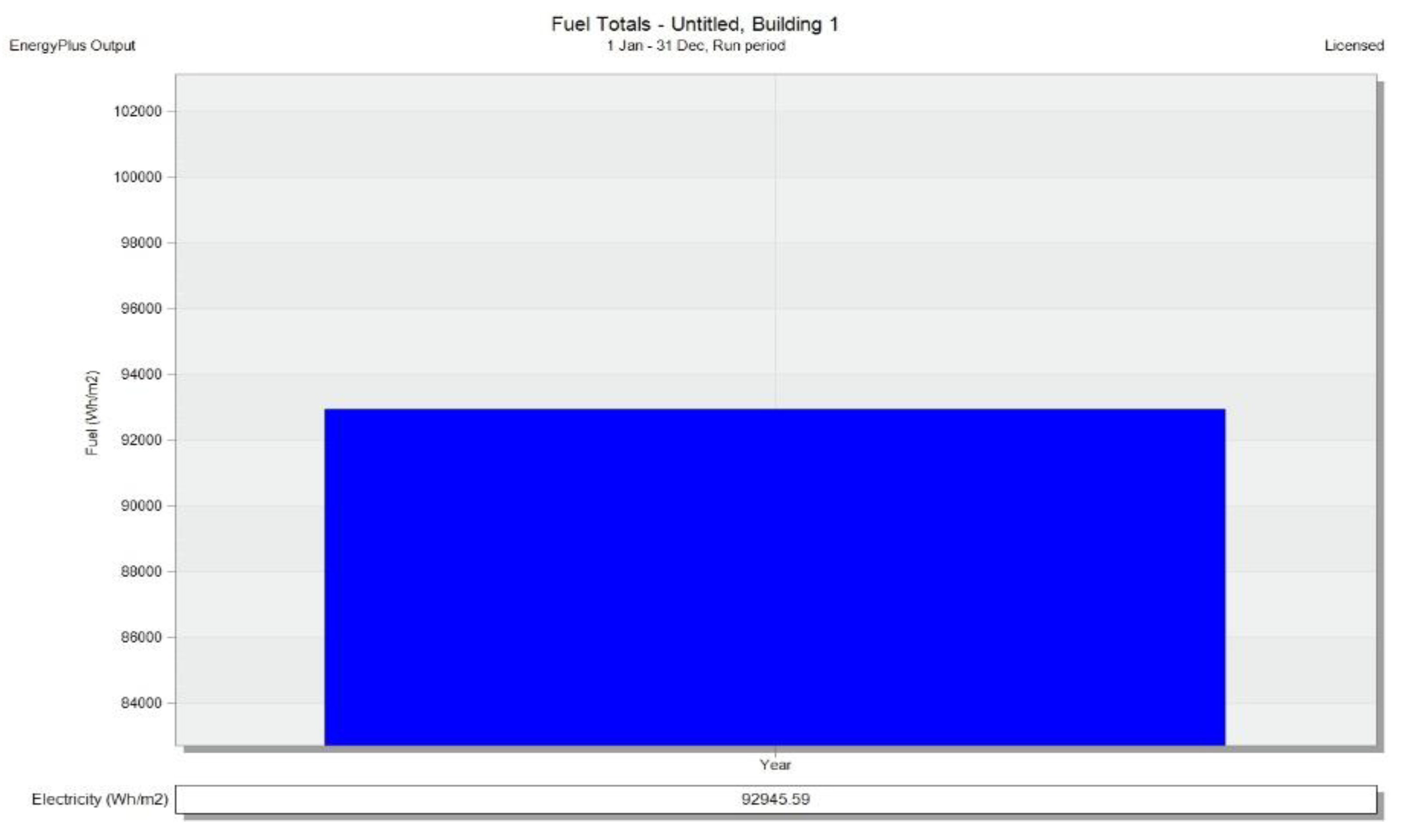

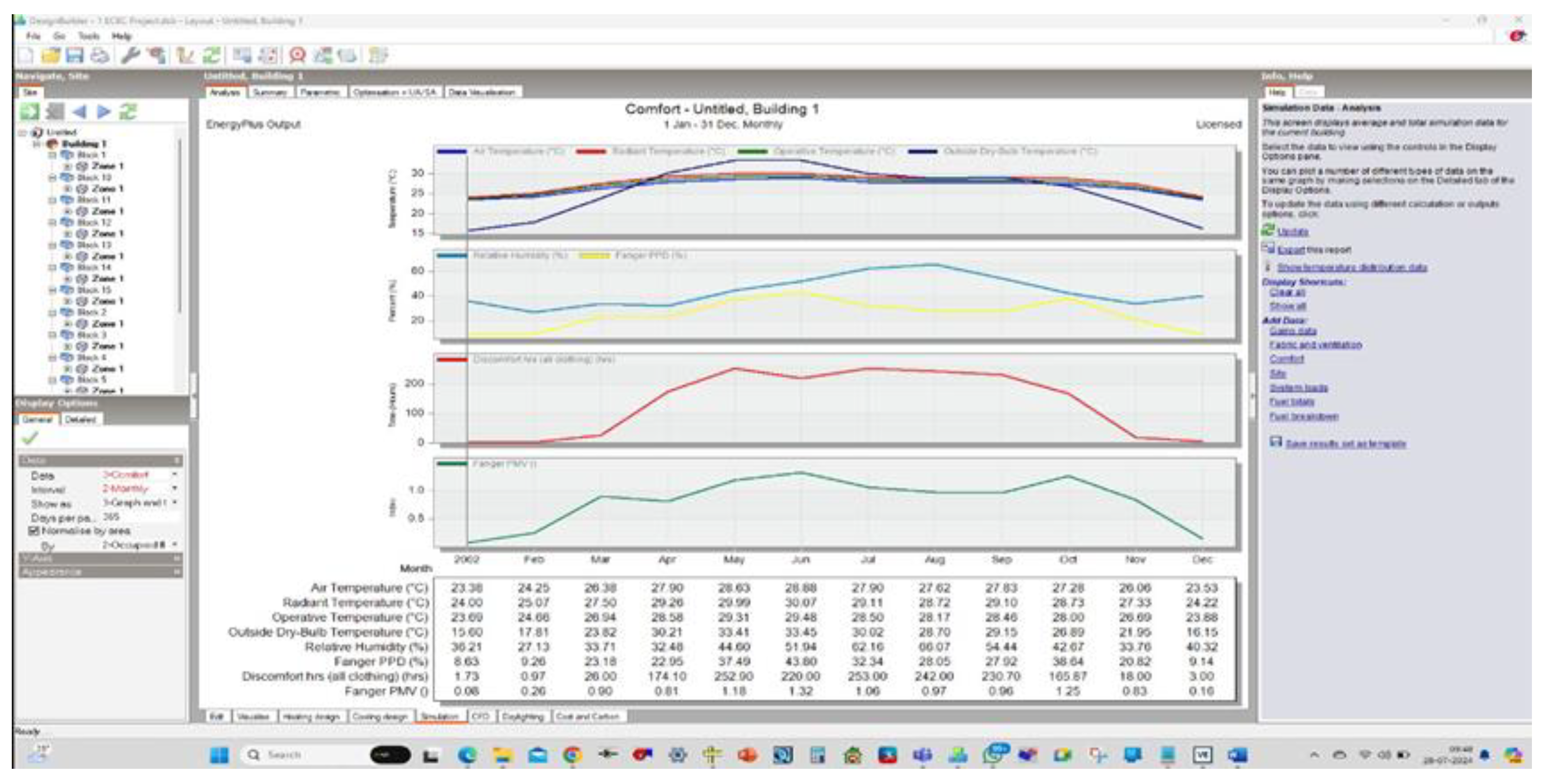

4.1. Baseline Performance

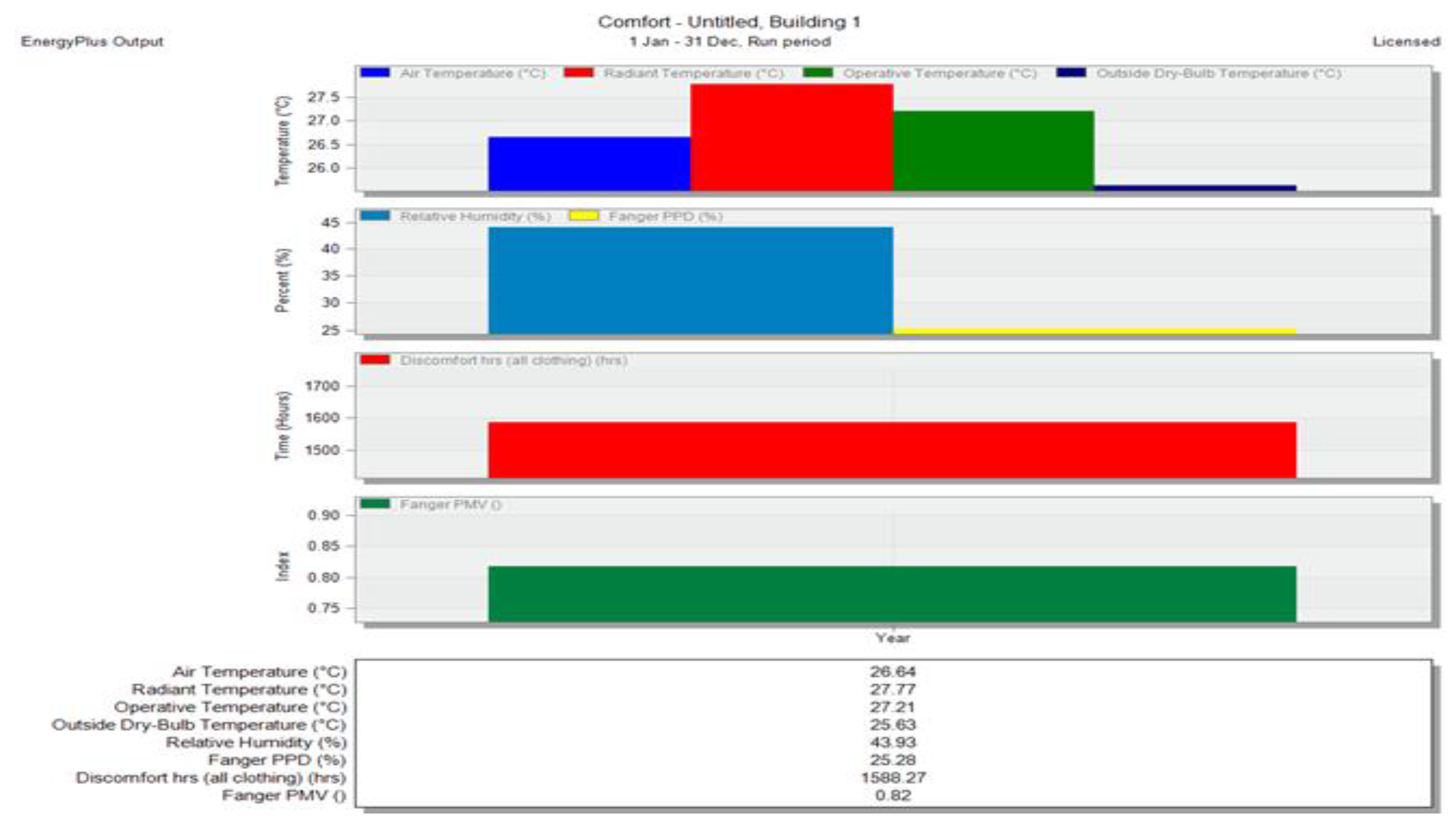

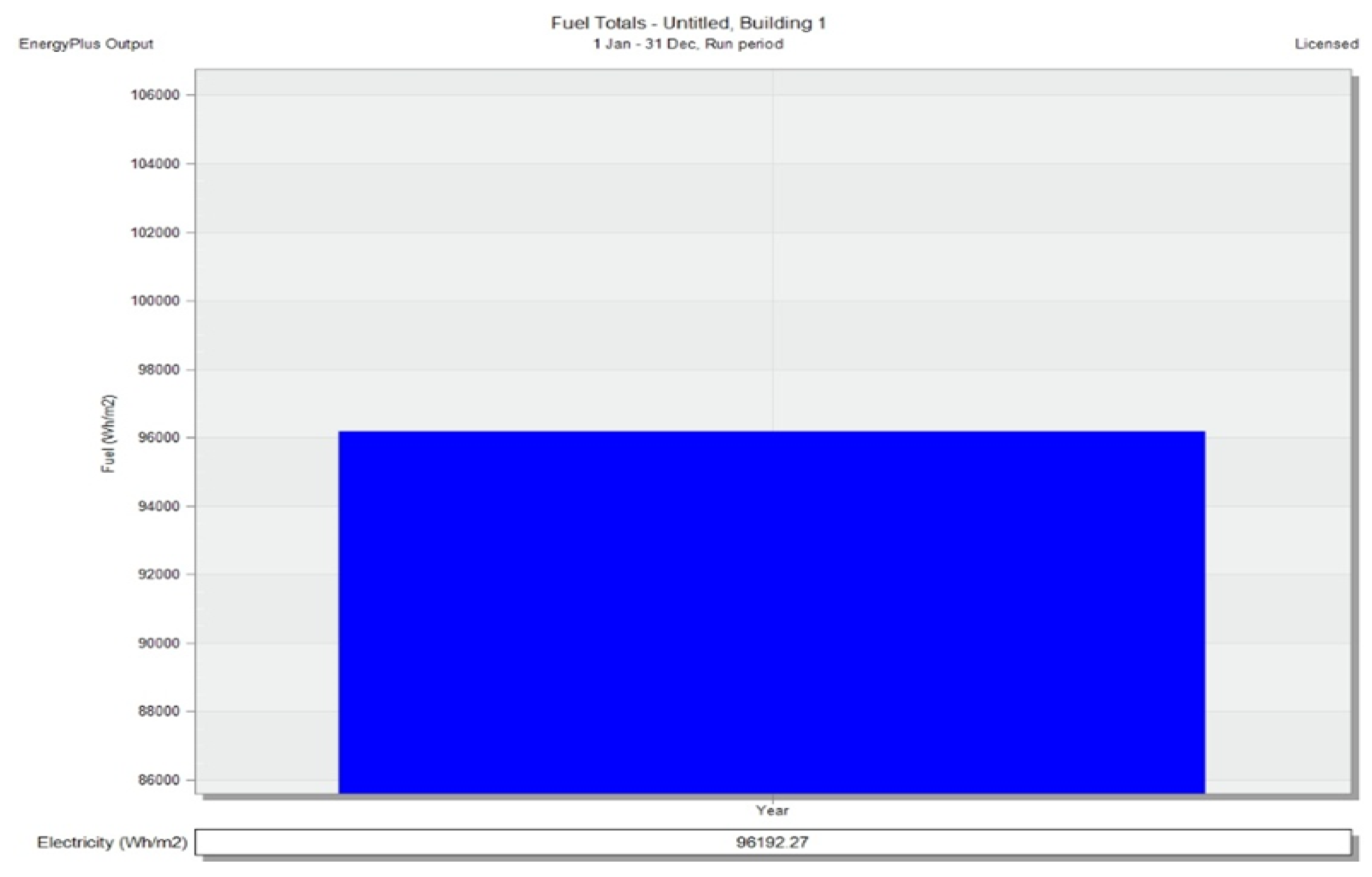

The ECBC Base Case, without any shading device, noticeably had the highest energy consumption and indoor discomfort values. The annual HVAC energy use was the high load is mainly due to extensive solar gains and thermal losses through the static facade, resulting in greater HVAC demand of about 96,192 Wh/m². Correspondingly, the base building experienced 1588 discomfort hours over the year, indicating that for nearly 18% of the time in a year, indoor environment fell outside the comfort zone refer

Table 1. The PPD was about 25.3%, meaning one in four occupants were predicted to be uncomfortable on average, and the PMV of +0.82 suggests the indoor environment tended to be uncomfortably warm for occupants (near the upper limit of the comfort range). Since the baseline simulation scenario meets the minimum standards, there is a need for improvement for enhancing the building energy efficiency and the indoor comfort for the users.

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 shows the monthly comfort graph, yearly bar chart for comfort and yearly bar chart for energy consumption respectively using ECBC base case.

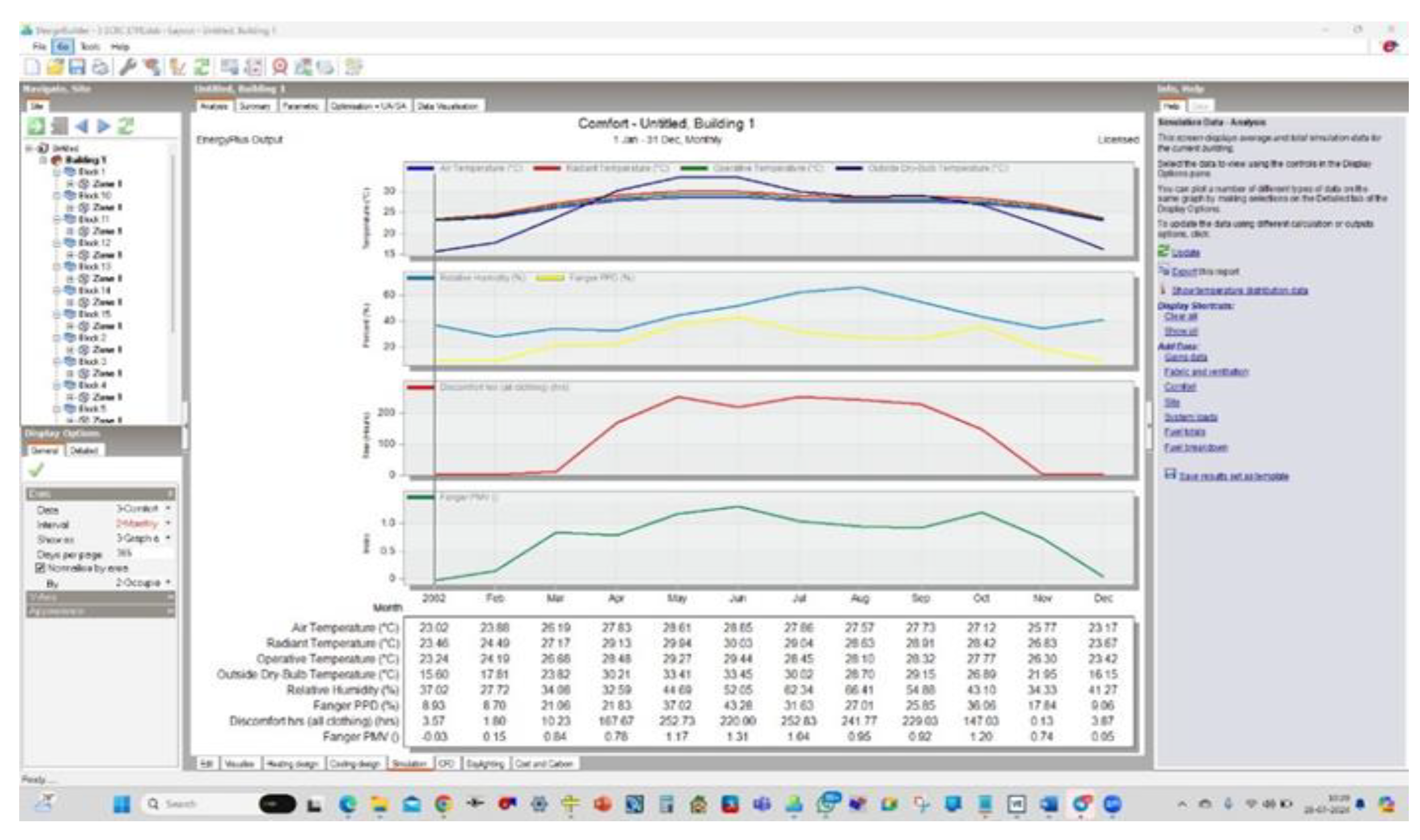

4.2. ETFE Façade Performance

Incorporating a responsive ETFE facade led to a noticeable improvement over the base case. Annual energy use dropped to ~94,885 Wh/m², which is a 1.36% reduction in HVAC energy consumption relative to the base case. While this energy saving is modest in percentage terms, it reflects the ETFE system’s ability to slightly reduce heat gains and losses by adapting to. The discomfort hours decreased to 1530.67 hours, about 58 fewer hours than the base case. This indicates that the ETFE dynamic facade kept the building in the comfort range for more hours of the year, likely by mitigating extreme thermal conditions. The PPD improved to 24.11%, so fewer occupants are predicted to feel dissatisfied, and the PMV moved to +0.76, closer to the neutral comfort point, referring to

Table 1.

The ETFE adaptive facade provided some enhancement in both energy efficiency and indoor environmental comfort, validating the concept that a dynamic envelope can outperform a static one.

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the monthly comfort graph, yearly bar chart for comfort and yearly bar chart for energy consumption respectively using ETFE on the façade as a shading material.

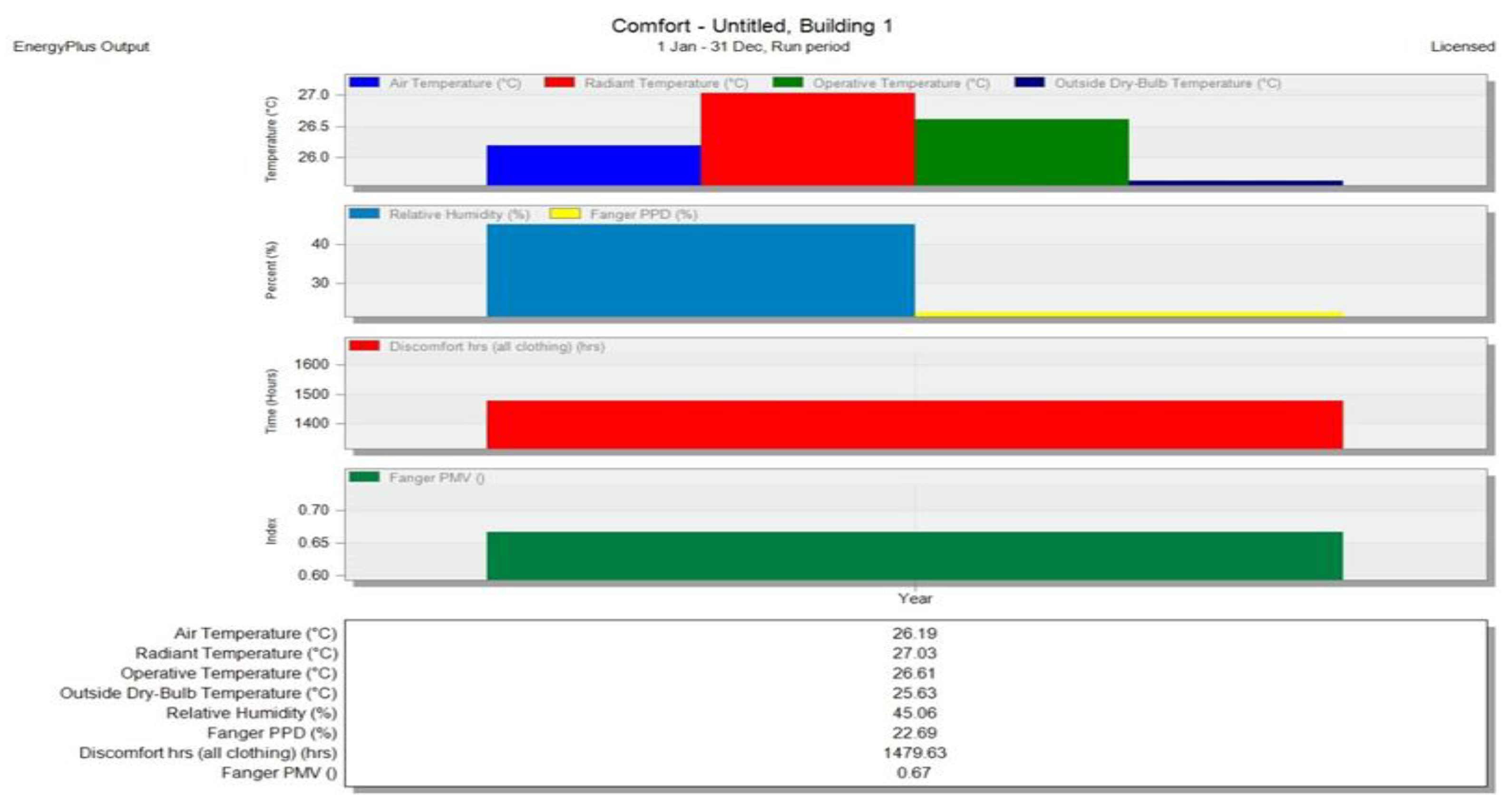

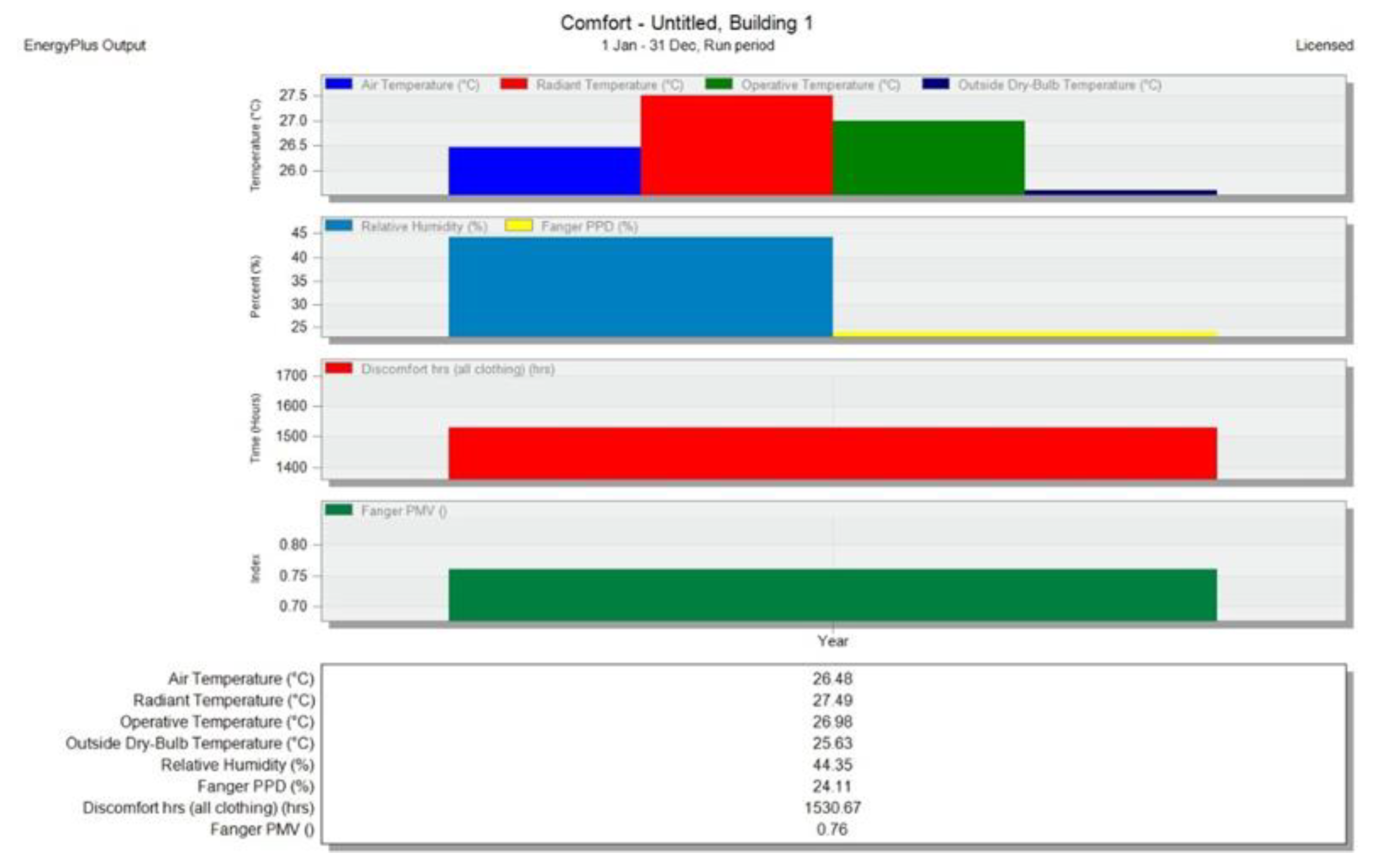

4.3. Auto Heal Façade Performance

The facade with the Auto Heal material demonstrated the best performance among the tested scenarios. The annual energy consumption dropped to 92,905.48 Wh/m², which is a 3.41% saving compared to the base case (and still about 2% better than the ETFE case). Significantly, the Auto Heal facade had the lowest number of discomfort hours (1477.53), indicating that the indoor environment quality stayed within the comfort range for a major portion of the year.

This is about 111 fewer uncomfortable hours than the base case – a noticeable improvement for occupants. The PPD in the Auto Heal scenario was 22.64%, the lowest of all the cases tested, signifying that the predicted dissatisfaction rate among occupants is reduced (roughly 2-3% fewer dissatisfied people compared to the base and 1.5% fewer than with ETFE). The PMV came down to +0.67, much closer to the ideal neutral value of 0 refer

Table 1.

This suggests that the indoor environment comfort with the Auto Heal facade was generally slightly warm but well within a tolerable range, improving overall thermal comfort. The superior performance of Auto Heal across all the parameters, i.e., lower energy use, fewer discomfort hours, lower PPD, and a PMV nearer to zero – underscores its potential as an innovative material for responsive kinetic facades.

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the monthly comfort graph, yearly bar chart for comfort and yearly bar chart for energy consumption respectively using ETFE on the façade as a shading material.

Figure 8.

Auto heal - The comfort graph (Monthly).

Figure 8.

Auto heal - The comfort graph (Monthly).

Figure 9.

Auto heal - Bar Chart for Comfort (Yearly).

Figure 9.

Auto heal - Bar Chart for Comfort (Yearly).

Figure 10.

Auto heal - Bar chart for Energy Consumption (Yearly).

Figure 10.

Auto heal - Bar chart for Energy Consumption (Yearly).

Table 1.

Performance of Base Case vs. Adaptive Facade Scenarios. (Annual values are given per square meter of floor area; PPD and PMV are comfort indices.)

Table 1.

Performance of Base Case vs. Adaptive Facade Scenarios. (Annual values are given per square meter of floor area; PPD and PMV are comfort indices.)

| Facade Scenario |

Annual HVAC Energy (Wh/m²) |

Discomfort Hours |

PPD (%) |

PMV |

| ECBC Base Case |

96,192.27 |

1588.27 |

25.28 |

+0.82 |

| ETFE Facade |

94,884.50 |

1530.67 |

24.11 |

+0.76 |

| Auto Heal Facade |

92,905.48 |

1477.53 |

22.64 |

+0.67 |

Graph 1. Illustrates these comparisons in terms of percentage savings in energy relative to the base, highlighting that Auto Heal achieved the highest reduction in energy use and indoor environment comfort.

Table 2.

Percentage savings of Base Case vs. Adaptive Facade Scenarios.

Table 2.

Percentage savings of Base Case vs. Adaptive Facade Scenarios.

| S.No |

Material |

Fuel totals (Wh/m²) |

Percentage Savings (%) |

| 1 |

ECBC |

96192.27 |

Base Case |

| 2 |

ETFE |

94884.5 |

1.36 |

| 3 |

Auto Heal |

92905.48 |

3.41 |

Graph 2. Illustrates Energy savings achieved by each facade material compared to the ECBC base case. The Auto Heal facade showed ~3.4% reduction in annual HVAC energy consumption, more than double the ~1.36% reduction achieved by the ETFE facade.

6. Results

The analysis indicates that ETFE has been an innovative material in this field, but emerging unique smart materials like Auto Heal have the potential to redefine the limits of innovation. By choosing facade materials that are responsive to the external climatic conditions, it is possible to develop building envelopes that substantially enhance building energy performance and occupant well-being by reducing the energy consumption.

7. Conclusion

This research examined the performance of smart materials as responsive kinetic facades that adapt and respond to the external climatic stimuli like solar radiation, light and humidity, intending to reduce building energy consumption and improve indoor comfort. All key arguments and findings from the simulations done on a conventional static facade (ECBC base case) against two adaptive facade scenarios: one using the well-known ETFE material and another using an innovative Auto Heal self-healing material, have been presented with a scientific tone and backed by data. The original hypothesis – that material choice in responsive facades significantly affects performance – is strongly supported by the results. Finally, it is worth noting that the benefits of smart kinetic facades go beyond the numbers captured in the simulations. Improved thermal comfort and reduced energy demand lower operational costs and carbon footprints. As the temperature rises globally and the need for a comfortable built environment, adaptive kinetic facades with thoughtfully selected materials will play a crucial role. This research paper offers data-backed validation report and evidence that investing in advanced smart materials like Auto heal is a progressive approach to develop an energy-efficient building that will contribute to the sustainable urban built environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and M.Y.; methodology, A.K. and S.M.A.; software, S.M.A.; validation, A.K., M.Y. and S.M.A.; formal analysis, A.K.; investigation, A.K. and S.M.A.; resources, A.K. and M.Y; data curation, A.K. and M.Y.; writing-original draft preparation, A.K.; writing – review and editing, A.K., M.Y and S.M.A.; supervision, M.Y.; project administration, M.Y. All authors have significantly contributed to the research work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Sunil Kumar, the Country Manager of METS laboratory in Ajman, UAE and his team of scientists who conducted the test TGA on Auto heal material to check its thermal properties and the onset degradation temperature required to validate the report prepared. I would like to extend my gratitude to my supervisor for giving me immense support in writing this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ETFE |

Ethylene Tetrafluoroethylene |

| ECBC |

Energy Conservation Building Code |

| ASHRAE |

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| PMV |

Fanger Predicted Mean Vote |

| PPD |

Fanger Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied |

| PMMA |

Polymethyl methacrylate |

| PVC |

Polyvinyl chloride |

| HVAC |

Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning. |

| METS |

Middle East Testing Services |

| TGA |

Thermogravimetric analysis |

| BPS |

Building Performance Simulation |

References

- G. o. I. Ministry of Power, Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC), New Delhi: Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE), 2017.

- ASHRAE, ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2017 Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy, Atlanta: American National Standards Institute (ANSI), 2017.

- ASHRAE, ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2019 Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality, Atlanta: American National Standards Institute ANSI, 2019.

- ASHRAE, ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1-2019 Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings, Atlanta: American National Standards Institute ANSI, 2019.

- D. P. Jung Min Han, "Seasonal Optimization of Dynamic Thermo-Optical ETFE Façade System," in Building Simulation 2019, 2019.

- S. S. Mahshad Azima, "Evaluating the impact of building envelope on energy performance: Cooling analyses," Journal of Construction Engineering Management & Innovation, 2022.

- M. F. M. A. D. L. C. H. N. L. B. N. I. W. F. M. Y. A. A. Seyedehzahra Mirrahimi, "The effect of building envelope on the thermal comfort and energy saving for high-rise buildings in hot–humid climate," Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016.

- L. S. Khaled Mansouri, "The Effects of Envelope Building Materials on Thermal Comfort and Energy Consumption. Case of Hot and Dry Climate," in International Conference on Contemporary Affairs in Architecture and Urbanism, 2019.

- S. L.,. J. P. Z. Z. Z. X. Z. C. T. R. J. W. W. Xiaofei Zhen, "Analysis of building envelope for energy consumption and indoor comfort in a near-zero-energy building in Northwest China," Results in Engineering, vol. 25, 2025.

- Z. W. Shenghan Li, "Improving Energy Efficiency and Indoor Thermal Comfort: A Review of Passive Measures for Building Envelope," in Proceedings of the 24th International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, 2021.

- M. M. A. R. T. S. J. L. Seyed Morteza Hosseini, "A morphological approach for kinetic façade design process to improve visual and thermal comfort: Review," Building and Environment, vol. 153, 2019.

- S. T. I. R. J. Y. C. L. S. Y. M. M.,. P. S. C. A. F. B. N. W. Sujan Dev Sureshkumar Jayakumari, "Energy and Daylighting Performance of Kinetic Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) Façade," Sustainability, 2024.

- F. Alotaibi, "The Role of Kinetic Envelopes to Improve Energy Performance in Buildings," Journal of Architectural Engineering Technology, 2015.

- W. Basma Nashaat, "Responsive Kinetic Facades: An Effective Solution for Enhancing Indoor Environmental Quality in Buildings," The First Memaryat International Conference (MIC 2017) Architecture of the Future: Challenges and Visions, 2017.

- H. H. Ahmed Abdelwahed Mekhamar, "BRIEF OVERVIEW OF CLIMATE RESPONSIVE FACADES & ITS KINETIC APPLICATIONS," Engineering Research Journal, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. H. A. Ahmed Omar M.S. Mostafa, "Adaptive Facades’ Technologies to Enhance Building Energy Performance and More, A literature review and case-based analysis," Emirates Journal for Engineering Research, vol. 27, no. 4, 2022.

- K. M. Rainer Barthel, "Transparente Architektur – Bauen mit ETFE Folien,," Detail - Zeitschrift für Architektur + Baudetail, p. 1616, 2002.

- D. H. Dániel Tamás Karádi, "An Extensive Review on the Viscoelastic-plastic and Fractural Mechanical Behaviour of ETFE Membranes," Periodica Polytechnica Architecture, p. 121–134, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Mahshad Azima, "Evaluating the impact of building envelope on energy performance: Cooling analyses," Journal of Construction Engineering Management, 2022.

- G. C. Y. S. R. L. A. R. S. S. Michelangelo Scorpio, "Double-Skin Facades With Semi-Transparent Modules For Building Retrofit Actions: Energy And Visual Performances," in Proceedings of Building Simulation 2019: 16th Conference of IBPSA, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Italy, 2019.

- Z. W., "The Constructive Membrane Building Transparent Building Structures Considering as Example the Allianz Arena, Munich, Covertex.".

- N. Biloria, "Adaptive Building Skin Systems," in Computation World: Future Computing, 2009.

- G. C. L. T. M. S. Yorgos Spanodimitriou, "Flexible and Lightweight Solutions for Energy Improvement in Construction: A Literature Review," in Energies 2023, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, 81031 Aversa, Italy, 2023.

- C. A. Z. Carol Monticell, "Environmental load of EFTE cushions and future ways for their self-sufficient performances," in Evolution and Trends in Design, Analysis and Construction of Shell and Spatial Structures, 2015.

- Z. M. C. Carol MONTICELLI, "Application and validation of eco-efficiency principles to assess the design of lightweight structures: case studies of ETFE building skins," in Proceedings of the IASS Annual Symposium 2017 “Interfaces: architecture . engineering . science” , Hamburg, Germany , September 25 - 28th, 2017.

- K. R. K. D. ·. A. G. W. R. N. Audrey L Worden, "ETFE Membrane Envelope Strategies : Adaptive Double Skin Façades For New Builds and Retrofits," in Facade Tectonics, 2022.

- X. L. Y. S. P. B. Jan-Frederik Flor, "Switching daylight: Performance prediction of climate adaptive ETFE foil façades," Building and Environment 209:108650.

- J. C. R. M. S. C. N. D. A. Jader de Sousa Freitas, "Modeling and assessing BIPV envelopes using parametric Rhinoceros plugins Grasshopper and Ladybug," Renewable Energy, vol. 160, pp. 1468-1479, 2020.

- Zolfagharpour, M. Shafaei and P. Saeidi, "Responsive Architecture Solutions to Reduce Energy Consumption of High-Rise Buildings.," EBSCOhost, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Shan, "INTEGRATING RHINOCEROS/GRASSHOPPER WITH GENETIC ALGORITHM IN," 1University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 2014.

- S. HARRY, "Dynamic Adaptive Building Envelopes – an Innovative and State-of-The-Art Technology," 2016.

- C. Diou, "Innovative Applications for Net-zero Buildings in Architecture, Based on the Principles of Bioinspiration".

- Y. Z. Y. C. Y. H. J. Y. Yanbin Li, "Shape-morphing materials and structures for energy-efficient building envelopes," materialstoday ENERGY, vol. 22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Moritz, "Transparency Carried by Air—Pneumatic ETFE-Foil Cushion Technology," in Structures Congress, May 2010.

- P. B. R. W. Rakhmat Fitranto Aditra, "Pneufin: A switchable foil cushion inspired soft pneumatic adaptive shading," Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 77, 2023.

- S. B. &. H. M. Faramarzi, "Optimal control of switchable ethylene-tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) cushions for building façades.," Solar Energy, pp. 218,180-194, 2021.

- B. Kraja, "RESPONSIVE SKINS–EVOLVING PARADIGM IN CITIES".

- L. A. Robinson, Structural opportunities of ETFE (ethylene tetra fluoro ethylene), MIT, 2005.

- M. James, "FAÇADE-Integrated Sustainable Technologies for Tall Buildings:," International Journal of Engineering Technology, Management and Applied Sciences, vol. 5, no. 5, 2017.

- W. N. Göran Pohl, Biomimetics for Architecture & Design, 2015.

- M. D. F. R. F. C. Chr. Lamnatou, "Ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) material: Critical issues and applications with emphasis on buildings," Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 82, pp. 2186-2201, 2018.

- M. Y. a. A. K. Antima Kuda, "Importance of Smart Materials Application In Building Skins: An Overview," in International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Knowledge Economy, 2023.

- Z. M. M. Carol Monticelli, "Material saving and building component efficiency as main eco-design principles for membrane architecture: case - studies of ETFE enclosures," Architectural Engineering and Design Management, vol. 17, no. 3-4, pp. 264-280, 2021.

- H. N. A. A. &. M. I. ABDELALL, "RESPONSIVE FAÇADES DESIGN USING NANOMATERIALS FOR OPTIMIZING BUILDINGS’ ENERGY PERFORMANCE," The Sustainable City XV.

- Y. Mansy, "Can Ethylene Tetra Fluoro Ethylene Cushions Double Skin Façade Applications Improve Buildings Envelope Performance, Reduce Energy Consumption and Enhance Visual and Thermal Comfort in UAE Buildings?," The British University in Dubai ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, Dubai, UAE, 2019.

- T. Srisuwan, "Fabric Façade: An Intelligent Skin". BUILT.

- J.,. L. H. Lee, "Responsive Pneumatic Facade with Adaptive Openings for Natural Ventilation," Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea Planning & Design, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 1226-9093, 2017.

- S. L. C. W. H. M. I. C. MONTICELLI, "ELLIPSOIDAL SHAPE AND DAYLIGHTING CONTROL FOR THE ETFE PNEUMATIC ENVELOPE OF A WINTER GARDEN," in VI International Conference on Textile Composites and Inflatable Structures, 2013.

- R. P. Wool, "Self-healing materials: a review," Soft Matter, 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. Fischer, "Self-repairing material systems―a dream or a reality?," Natural Science, vol. Vol.2 No.8, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Ghosh, Self Healing Materials - Fundamentals, Design Strategies, and Applications, WILEY-VCH.

- N. J. K. P. H. H. M. J. K. S. W. H. Kiwon Choi, "Properties and Applications of Self-Healing Polymeric Materials: A Review," Polymers 2023, November.

- Y. G. K. S. P. Y. B. F. L. Yasmeena Javeed, "Microbial self-healing in concrete: A comprehensive exploration of bacterial viability, implementation techniques, and mechanical properties," Journal of Materials Research and Technology, January 2024.

- H. M. Jonkers, "Self Healing Concrete: A Biological Approach," in Self Healing Materia, SPRINGER NATURE, pp. 195-204.

- R. Stott, "Three Self-Healing Materials That Could Change the Future of Construction," ArchDaily - Architecture News, 2014.

- L. Z. S.-J. X. D. M. L. Cen-Ying Liao, "Recent Advances of Self-Healing Materials for Civil Engineering: Models and Simulations," Buildings 2024- Advanced Numerical and Computer Methods in Civil Engineering—2nd Edition.

- L. Z. S.-Y. H. S.-J. X. D. M. L. Cen-Ying Liao, "Recent Advances of Self-Healing Materials for Civil Engineering: Models and Simulations," Advances of Self-Healing Materials. Buildings 2024.

- N. R. S. D. A. A. K. &. P. P. Suman Kumar Adhikary, "Chemical-based self-healing concrete: a review," Discover Civil Engineering, vol. 1, November.

- K. V. T. a. N. D. Belie, "Self-Healing in Cementitious Materials—A Review," Materials 2013, 2013.

- E. C. Valérie Pollet, "Investigations on the development of self-healing properties in protective coatings for concrete and repair mortars," in ICSHM 2009 - 2nd international conference on self-healing materials, Chicago, 2009.

- M. J. Hans-Wolf Reinhardt, "Permeability and self-healing of cracked concrete as a function of temperature and crack width," Cement and Concrete Research, vol. 33, pp. 981-985, 2003. [CrossRef]

- T. E. Sma Nanayakkara, "SELF-HEALING OF CRACKS IN CONCRETE WITH PORTLAND LIMESTONE CEMENT," Engineering, Materials Science, 2005.

- Y. A. Abdel-Jawad, "“Self-Healing of Self-Compacting Concrete ”," in Proceedings of SCC 2005, Chicago, 2005.

- J. A. L. R. H. B. L. M. D. R. T. Nijland, "Self healing phenomena in concretes and masonry mortars: A microscopic study," in SEMANTIC SCHOLAR, 2007.

- M. O. R. F. N. I. V. R. S. M. R. H. A. T. O. Mugahed Amran, "Self-Healing Concrete as a Prospective Construction Material: A Review," Materials 2022.

- S. L. S. c. S. R. Ben Blaiszik, "Self-healing polymers and composites.," Annual Review of Materials Science, 2010.

- M. W. U. Siyang Wang, "Self-healing polymers," Nature Reviews Material, 2020.

- M. L. S. Z. L. L.,. Q. F. J. H. Lei Peng, "A Self-Healing Coating with UV-Shielding Property," Coatings, vol. 9, no. 7, 2019.

- W. L. W. C. X. H. G. Z. Y. M. X. J. Q. L. Yifan Huang, "Self-healing, adaptive and shape memory polymer-based thermal interface phase change materials via boron ester cross-linking," Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 496, 2024.

- S. M. D. S. Dong Yang Wu, "Self-healing polymeric materials: A review of recent developments," Progress in Polymer Science, 2008.

- M. L.,. Z. W. C. C. C. M. G. Y. Jing Yan, "Highly tough, multi-stimuli-responsive, and fast self-healing supramolecular networks toward strain sensor application," Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 389, 2020.

- M. R. MingQiu ZHANG, "Design and synthesis of self-healing polymers," SCIENCE CHINA Chemistry, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 648-676, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. D. B. a. F. Wudl, "Mendable polymers," Journal of Materials Chemistry, pp. 41-62, 2008.

- J. K. B. a. D. N. Tripathi, "Self-Healing Polymer Composites for Structural Application," in Functional Materials, 2018.

- L. H. B. Y. H. Z. Meng Wu, "Self-healing hydrogels based on reversible noncovalent and dynamic covalent interactions: A short review," Supramolecular Materials, vol. 2, December.

- R. Dallaev, "Advances in Materials with Self-Healing Properties: A Brief Review," Materials, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Nealon, "A wolverine inspired material: Self-healing, transparent, highly stretchable material can be electrically activated," Materials Science, December.

- C. W. Yue Cao, "A transparent, self-healing, highly stretchable ionic conductor," Advanced Materials, 2016.

- R. H. X. L. A. T. Amir Tabadkani, "Simulation-based personalized real-time control of adaptive facades in shared office spaces," Automation in Construction, vol. 138, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. T. Ping Chen, "A Framework for Adaptive Façade Optimization Design Based on Building Envelope Performance Characteristics," Buildings - Building Energy and Environment, 2024.

- P. N. Barakat, "Benefits of High-Performance Facades to improve building performance and achieve Sustainable Designs," Pakinam Nabil Barakat/Engineering Research Journal, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Rudai Shan, "Multi-Objective Optimization for High-Performance Building Facade Design: A Systematic Literature Review," Sustainability - AI and IoT for Promoting Green Operation and Sustainable Environment, 2023.

- M. Z. Y. L. Y. Y. Y. L. R. Y.,. Y. Y.,. X. J. X. W. F. Z. S. H. D. H. L. X.,. R. Y. Yiqun Pan, "Building energy simulation and its application for building performance optimization: A review of methods, tools, and case studies," Advances in Applied Energy, vol. 10, 2023.

- T. N. Adam, "Evaluation of Adaptive Facades within Context of Sustainable Building in Northern Cyprus," 2023.

- R. C. L. F. G. M. D. Fabio Favoino, Building Performance Simulation and Characterisation of Adaptive Facades - Adaptive Facades Network, 2018.

- R. L. Jan LM Hensen, "Building performance simulation – challenges and opportunities," in Building Performance Simulation for Design and Operation, 2019, pp. 1-10.

- J. R. F. R. R. V. G. B. Himanshu Patel Tuniki, "Thermal Comfort and Adaptive Occupant Behaviour in Open Plan Offices in India and Lithuania," Buildings 2025 - Building Energy, Physics, Environment, and Systems.

- M. Miren Juaristi, "Adaptive façades in temperate climates. An in-use assessment of an office building," in Advanced Building Skins, 2016.

- H. MODIN, Adaptive building envelopes.

- W.-j. C. B. Z. D. Y. Jianhui Hu, "Buildings with ETFE foils: A review on material properties, architectural performance and structural behavior," Construction and Building Materials, 2017.

- K. Moritz, "Transparency Carried by Air—Pneumatic ETFE-Foil Cushion Technology," in Structures Congress 2010, 2010.

- D. A. A. M. A. A. A. S. W. L. J. C. Benson Lau, "Understanding Light in Lightweight Fabric (ETFE Foil) Structures through Field Studies," Procedia Engineering, vol. 155, pp. 479-485, 2016.

- J. Chilton, "Lightweight envelopes: ethylene tetra-fluoro-ethylene foil in architecture," in Construction Materials, vol. 166, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. K. A. C.,. S. T. S Robinson-Gayle, "ETFE foil cushions in roofs and atria," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 323-327, 2001.

- P. S. F. A. A.-A. L. K. A. K. D. A. Ashish Srivastava, "Self-Healing Materials: Mechanisms, Characterization, and Applications: A detailed Review," in 3rd International Conference on Applied Research and Engineering (ICARAE2023), 2024.

- K. T. D. B. A. P. D.G. Bekas, "Self-healing materials: A review of advances in materials, evaluation, characterization and monitoring techniques," Composites Part B: Engineering, vol. 87, pp. 92-119, 2016.

- P. A. D. B. H. A. Anurag Aman Kaushal, "Assessment of the Impact of Building Orientation on PMV and PPD in Naturally Ventilated Rooms During Summers in Warm and Humid Climate of Kharagpur, India," in BuildSys '23: The 10th ACM International Conference on Systems for Energy-Efficient Buildings, Cities, and Transportation, 2023.

- P. A. D. B. H. A. Anurag Aman Kaushal, "Assessment of the Impact of Building Orientation on PMV and PPD in Naturally Ventilated Rooms During Summers in Warm and Humid Climate of Kharagpur, India," in BuildSys '23: The 10th ACM International Conference on Systems for Energy-Efficient Buildings, Cities, and Transportation, 2023.

- J. L. B. L. Runming Yao, "Occupants’ adaptive responses and perception of thermal environment in naturally conditioned university classrooms," Applied Energy, vol. 87, no. 3, pp. 1015-1022, 2010.

- H. Y. J. C. L. Liu Yang, "Thermal comfort and building energy consumption implications – A review," Applied Energy, pp. 164-173, 2014.

- R. J. d. D. Gail S. Brager, "Thermal adaptation in the built environment: a literature review," Energy and Buildings, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 83-96, 1998.

- J. V. Hoof, "Forty years of Fanger’s model of thermal comfort: comfort for all?," INDOOR AIR -International Journal of Indoor Environment and Health, 2008.

- J. T. P. Ole Fanger, "Extension of the PMV model to non-air-conditioned buildings in warm climates," Energy and Buildings, vol. 34, no. 6, 2002.

- T. N. Hirozo Mihashi, "Development of Engineered Self-Healing and Self-Repairing Concrete-State-of-the-Art Report," Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology, 2012.

- L. Z. S.-Y. H. S.-J. X. Cen-Ying Liao, "Recent Advances of Self-Healing Materials for Civil Engineering: Models and Simulations," Buildings.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).