1. Introduction

Austenitic stainless steels exhibit a good resistance to corrosion and high ductility and are used for many applications such as aerospace, automotive, marine, defense [

1], chemical industries and medical applications [

2,

3]. However, wider use of these steels requires improved mechanical properties and wear resistance [

4]. These improvements can be achieved by using metal-matrix composites reinforced with ceramic particles, which provide higher hardness, toughness, wear resistance and corrosion resistance. Several types of ceramic particles have been used [

5,

6], including Al₂O₃, SiC, TiC, TiN and ZrC.

Regarding stainless steels, only a few reinforcement studies have been carried out, mainly with alumina particles. Alumina is attractive for metal-matrix composites due to its good hardness, wear resistance, chemical inertness, thermal stability and low cost.

Several techniques can be used to produce these composites:

• Melting and solidification (conventional ingot casting [

7], Laser Powder Bed Fusion [

8]).

• Powder metallurgy process with the following steps: powder mixing, powder preparation, debinding and sintering. In order to form the ceramic powder into the component shapes, uniaxial compaction is generally used; Metal Injection Molding can also be employed [

9]. Different sintering processes are possible: pressureless sintering [

3,

5], hot pressing [

6], spark plasma sintering (SPS) [

10,

11].

In these processes, the powders employed typically consist of blends of both materials. Such mixtures exhibit heterogeneities arising from particle agglomeration, particularly when the alumina powder used is nanoscale. Post-consolidation, the addition of Al₂O₃ in 316L results in increased hardness but also a deterioration in mechanical strength and elongation at break due to porosity formation and poor wettability of 316L on Al₂O₃ [

12,

13].

To address these challenges of powder mixture heterogeneity, several studies have adopted a two-step approach: granule preparation via spray granulation followed by RF plasma spheroidization. This methodology has been successfully applied to fabricate composite powders, at the particle scale, of metal/metal [

14,

15,

16], metal/ceramic [

17,

18,

19], ceramic/ceramic [

20,

21] or more complex compositions such as Dual-Phase High-Entropy Ceramics (DPHECs) [

22].

In this study, the 316L/Al₂O₃ composite granules were prepared by spray granulation and spheroidized using RF plasma. The resultant powders were subsequently consolidated using Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS); density, hardness and microstructure were determined. This enabled a comparative evaluation of materials obtained from plasma-processed powders against those fabricated from granules and powder blends.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Powders

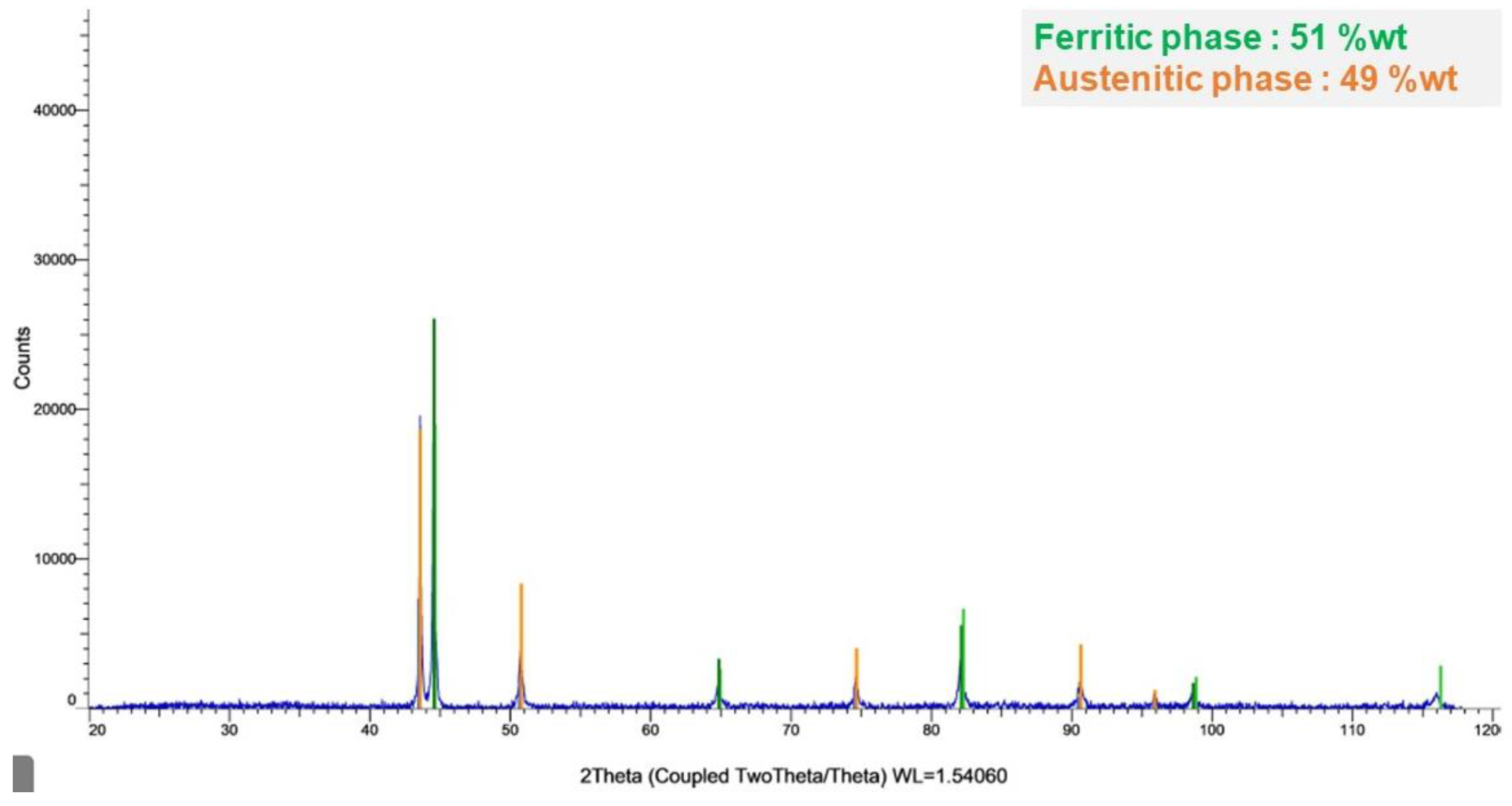

The composite used in this paper was processed using a mixture of two commercial micron powders: high purity (99.9%) commercial alumina Al₂O₃ (P172HPB – ALTEO) with a median nanoparticle size of 400 nm and 316L powder (PF-3K – EPSON ATMIX) with a median particle size of 3 µm. An XRD analysis of 316L powder shows that it is composed of two phases: ferrite and austenite (

Figure 1).

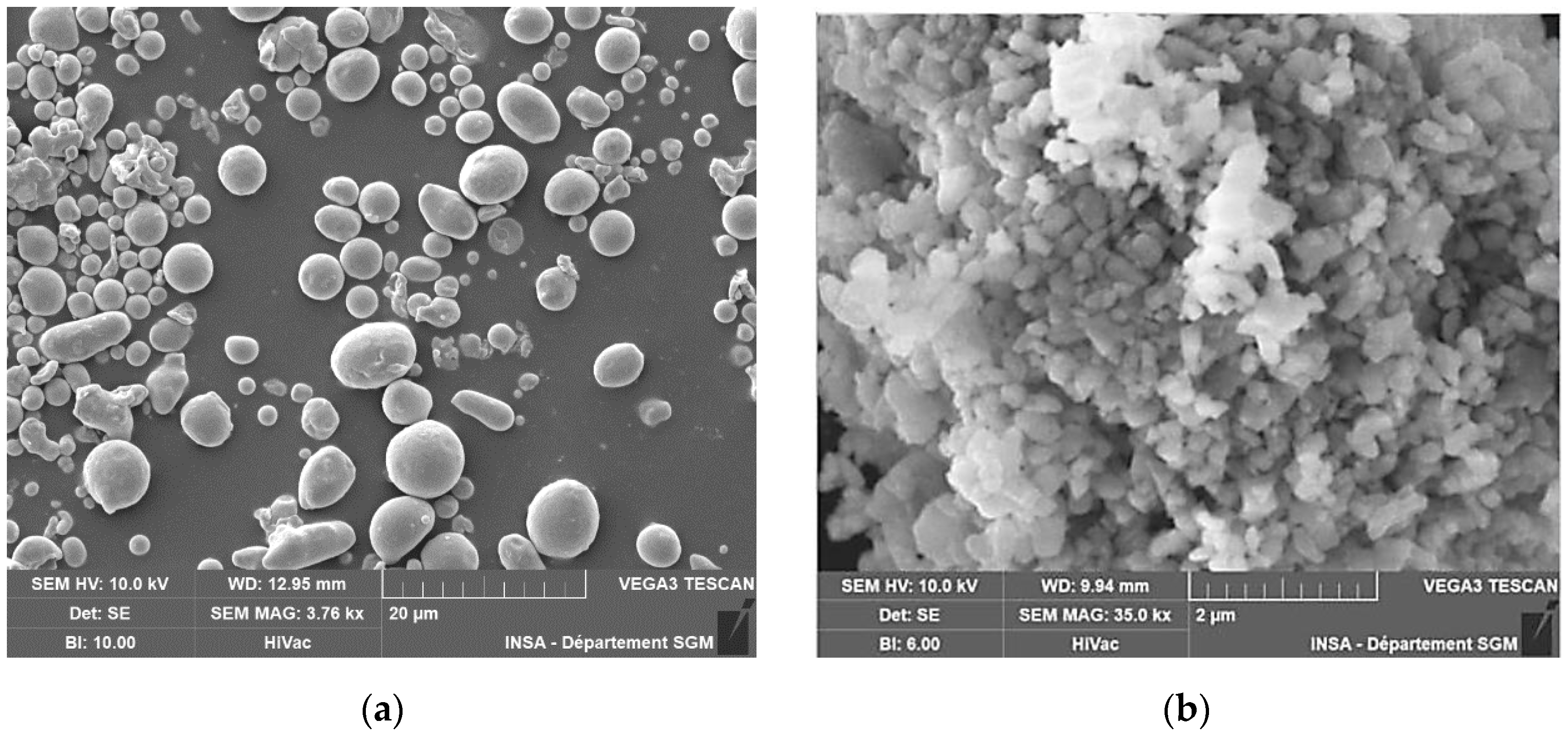

Figure 2a shows the 316L powder made of spherical micronic particles, whereas submicron alumina particles display more non-spherical and agglomerated nanaparticles (

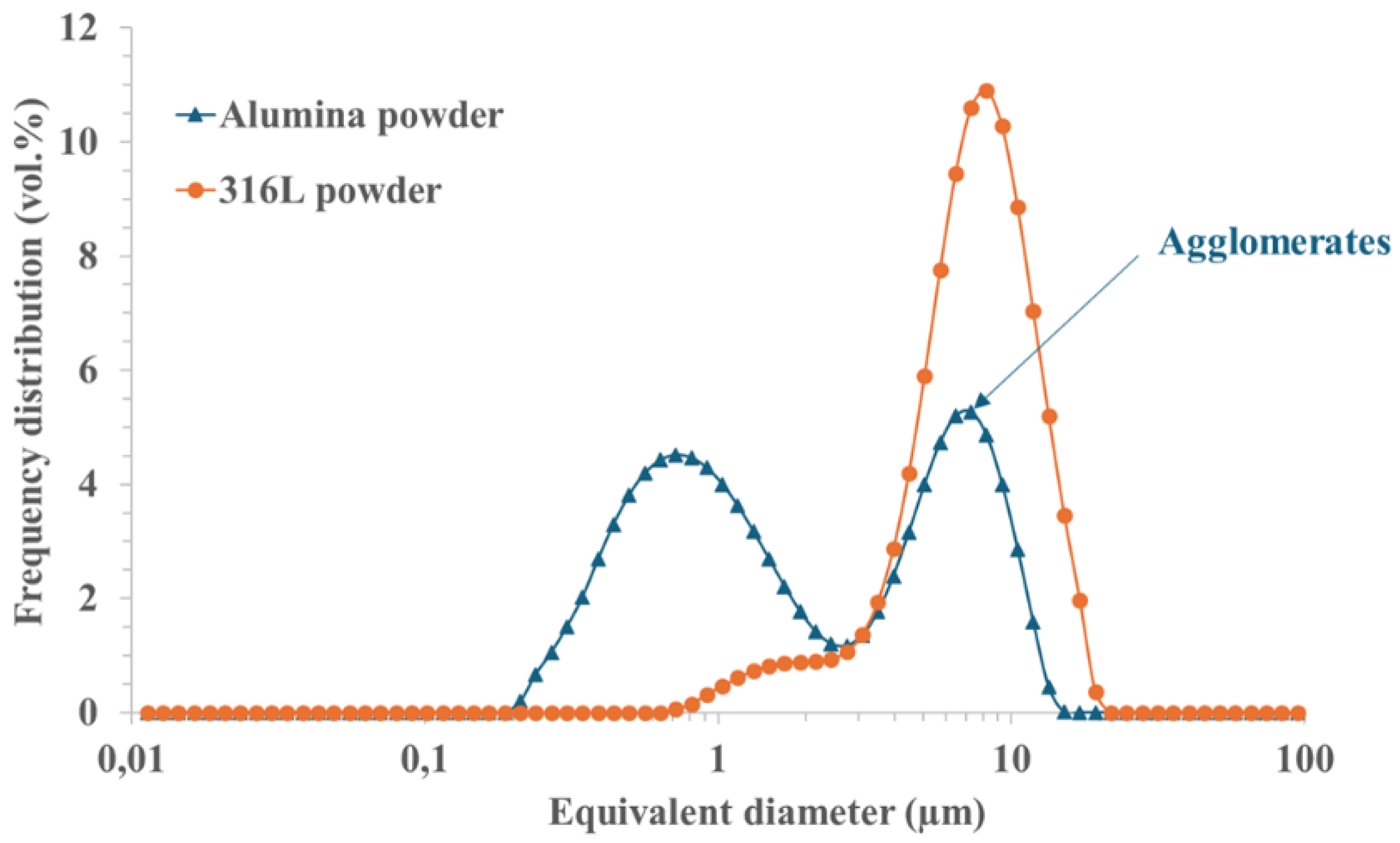

Figure 2b). A size distribution measurement was carried out on each of the initial powders (

Figure 3): 316L powder with D10 = 1.4 µm / D50 = 3.6 µm / D90 = 8.1 µm and alumina powder with D10 = 0.4 µm / D50 = 1.6 µm / D90 = 8.4 µm.

2.2. Suspension and Spray-Granulation

A formulation was prepared using a mixture of the two powders (80 vol% 316L / 20 vol% Al₂O₃) with polyacrylic acid as a dispersant (PAA, Mw 2000). The dispersant is dissolved (0.5 wt%) in high purity water after adjusting the pH to 11. The solution is homogenized for 10 min before adding the alumina powder. The alumina suspension was stirred for 24 hours before the steel powder was added. The mixture was then stirred for a further 4 hours before being atomized.

Wet laser granulometry (Malvern – Scirocco 2000) is used to check the state of dispersion.

The resulting slurry, with a solid loading ratio of 50 wt%, is spray-dried in an ultrasonic atomizer (Synetude SAS). A 20 kHz ultrasonic probe was used, with inlet and outlet temperatures maintained respectively at 250 °C and 110 °C.

The granules are then treated during 1h at 400°C for debinding and 1h at 800°C for consolidation.

2.3. Plasma Spheroidization

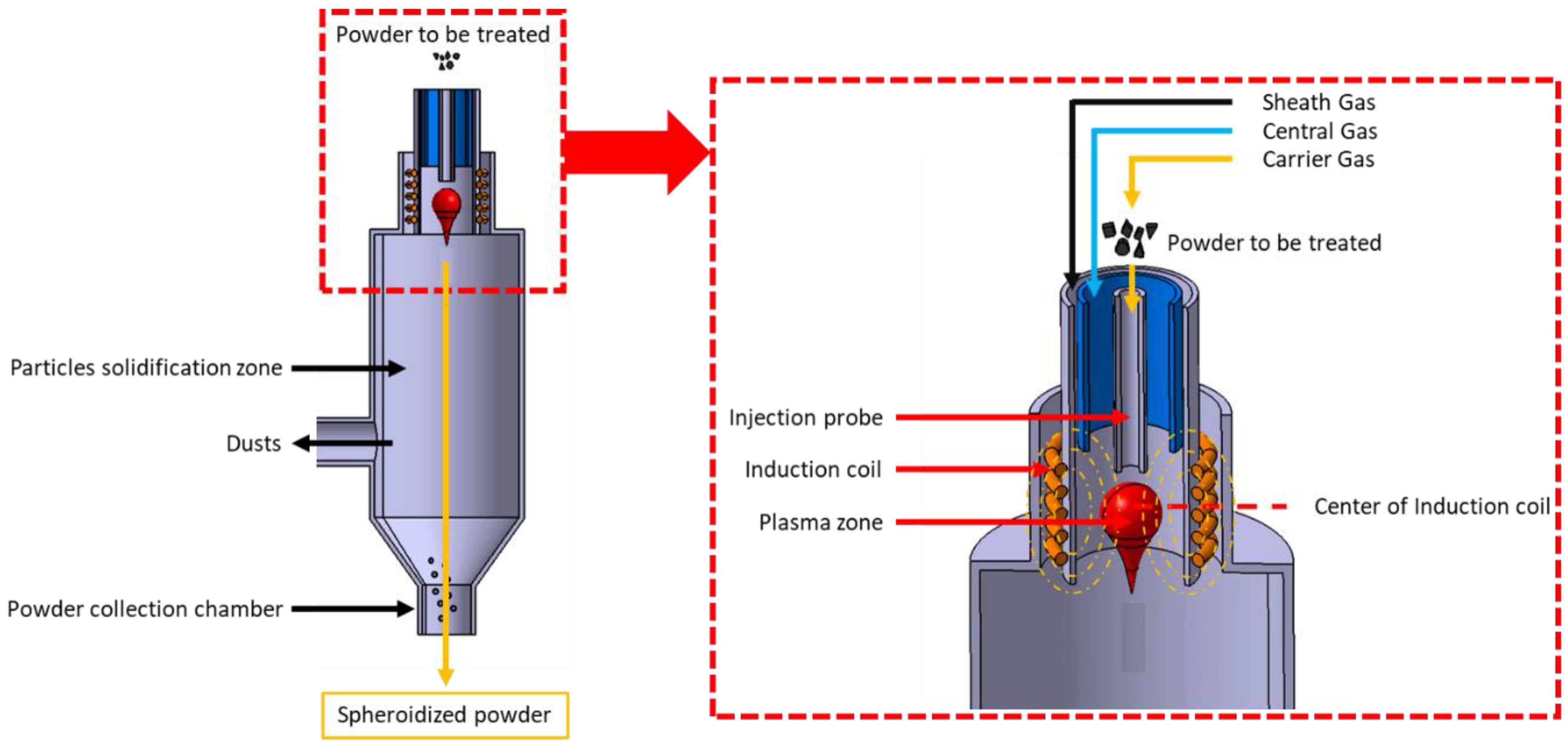

The granules are processed using RF plasma treatment on a TekSphero-40 spheroidization system (TEKNA). This treatment is employed to produce spherical and dense 316L/Al₂O₃ composite particles. A schematic representation of the spheroidization process, previously described in the literature [

23], is presented in

Figure 4.

The TekSphero-40 process parameters include power, gas flow rates, powder feed rate and the position of the powder injection probe in the plasma. The power can range from 20 to 40 kW. Argon gas is used to generate the plasma (central gas), convey the powder (carrier gas) and protect the torch walls (sheath gas). Hydrogen is often mixed with the sheath gas to enhance the thermal conductivity of the plasma. The atmosphere within the torch is maintained at a slight overpressure (15 psi) to prevent air entering. The processed powder is collected under argon and subsequently washed with water to remove the nanoparticles on the surface of the micrometric particles. The parameters employed in this study are detailed in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

2.4. Spray-Granulated and Spheroidized Granules Characterization

Granule bulk density is obtained by helium pycnometry (Micromeritics – Accpyc 1340). The size distribution of granules is measured by laser granulometry (Malvern – Scirocco 2000). All granule batches were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Zeiss-Supra 55.

In order to estimate the average size of the inner granule voids, X-ray computed microtomography scans are conducted on bulk samples. This technique is an alternative way to determine the pore size and visualize the microstructure of an entire granule, with a resolution comparable to that of optical microscopy instruments and in a non-destructive manner. As a result, individual pores are visualized and the true internal morphology of granules is revealed. X-ray tomography is performed using a v/tome/x (Phoenix X-ray Company) X-ray microtomograph. This commercial device includes a nanofocus transmission X-ray tube (W target).

2.5. Densification

The composites were densified using the spark plasma sintering (SPS) technique. The granules are introduced into a graphite die that allows uniaxial stress to be applied during sintering. A pulsed direct electrical current is applied via electrodes and passed through the pressing chamber to heat the sample. The temperature is measured using an optical pyrometer positioned close to the sample. A graphite paper foil is placed between the die, pistons and powder to protect the pressing elements.

The graphite die has an internal diameter of 10 mm and a thickness of 10 mm. During the entire cycle, a constant pressure of 64 MPa (5 kN) is maintained, and sintering is performed under high vacuum (∼1 Pa). The temperature cycle, for which we use is: heating up to 1040 °C with a ramping rate of 100 °C/min, up to 1070 °C at 10 °C/min to avoid overshoot, holding at 1070 °C for 1 h and cooling at 50 °C/min.

2.6. Sintered Samples Characterization

The density of sintered samples was measured using Archimedes method with distilled water. The values of the relative densities were calculated assuming a theoretical density of 7.17 g/cm3, taking into account the ratio of both materials and a theoretical density of 7.98 g/cm3 for the 316L and 3.94 g/cm3 for alumina. The measurement uncertainty was ± 0.2.

All sintered bodies were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Zeiss-Supra 55VP, after a polishing step. The polishing process proceeded as follows: first, diamond shields with grit sizes of 200, 500, 1200 µm were used. Then, diamond grains suspended in a lubricating fluid were applied with polishing cloths of grit sizes 6 nm, 3 nm and 1 nm. The polishing effect was continuously controlled after each step to obtain the best-quality mirror-finished samples.

A conventional Vickers hardness test (TestWell FV-700 equipment) under a 5 kg load applied for 10 s was performed. The choice of the applied load was made to ensure a well-defined imprint shape and a surface representative of the composite structure.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Spray-Granulation Optimization

Several slurries have been developed to optimise suspension parameters such as solid loading ratio, dispersant ratio and nature (polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyacrylic acid (PAA)) or pH (

Table 3).

To determine the optimum parameters, the slurries and granules obtained from these different slurries were characterized.

A first check is always made on the state of dispersion of the alumina alone, using the values given in the data sheet. In the case of slurry 3, it can be seen that the alumina disperses well and that, after the addition of the 316L powder, the slurry remains fluid and relatively stable.

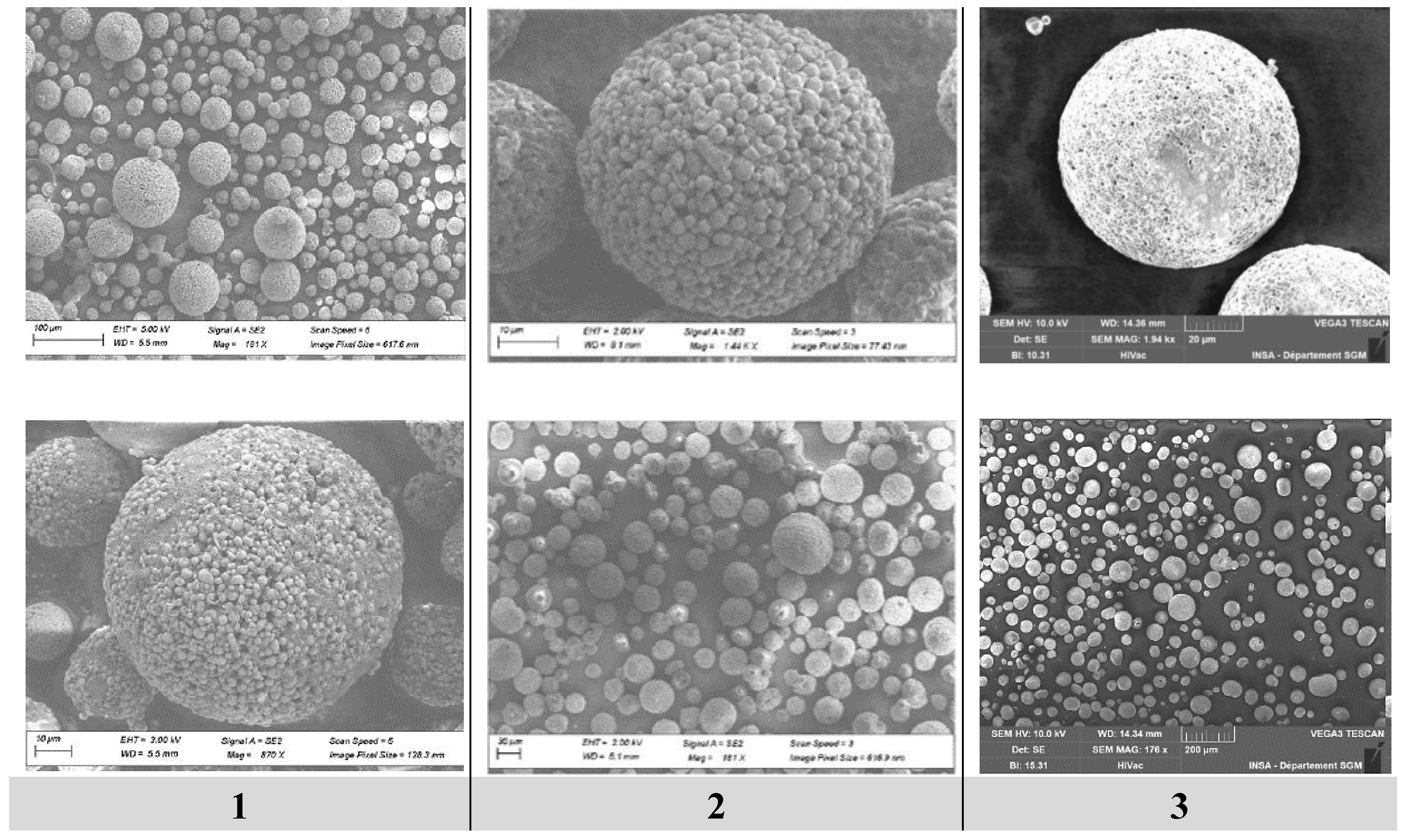

The microstructure of the granules obtained from each slurry was observed by SEM and X-ray tomography (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The different batches of granules have a fairly wide size distribution, which was characterized by laser granulometry (

Table 4). The granules appear to be fairly homogeneous, consisting of a mixture of submicron alumina particles and micron stainless steel particles. Examination of the internal microstructure of Batch 1 granules using X-ray tomography (

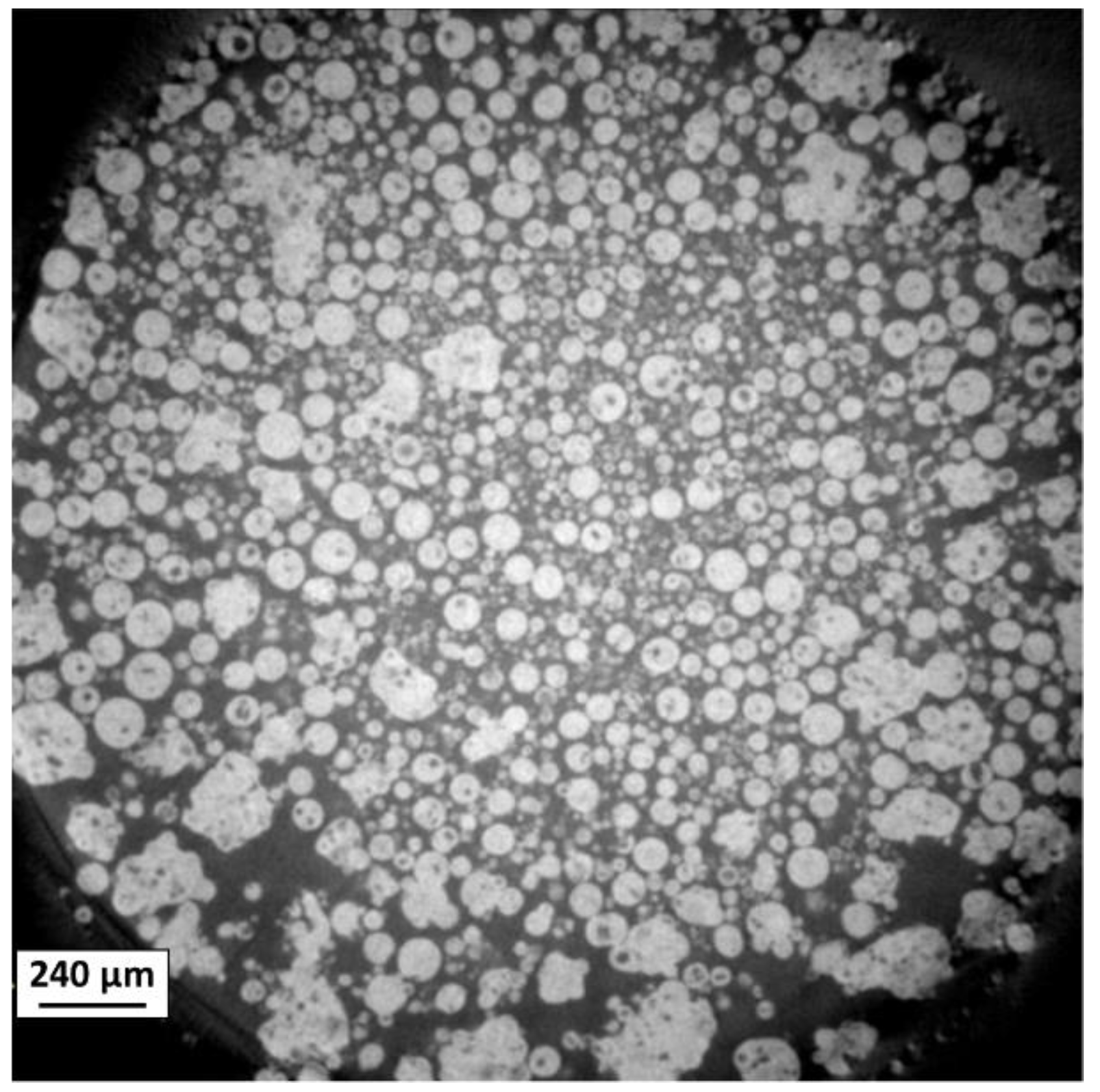

Figure 6) reveals that some are hollow, but overall, they are mostly dense.

The slurry 3 seems to give denser granules, closer to the theoretical density of the composite (theoretical density for a composite of 80 vol% 316L / 20 vol% Al

2O

3: 7.17 g/cm3). This could be explained by a higher solid content. In addition, the size distribution is narrower, with the largest granules decreasing in size. The reduction in size of the larger granules is confirmed by SEM images (

Figure 5).

3.2. Plasma Spheroidization

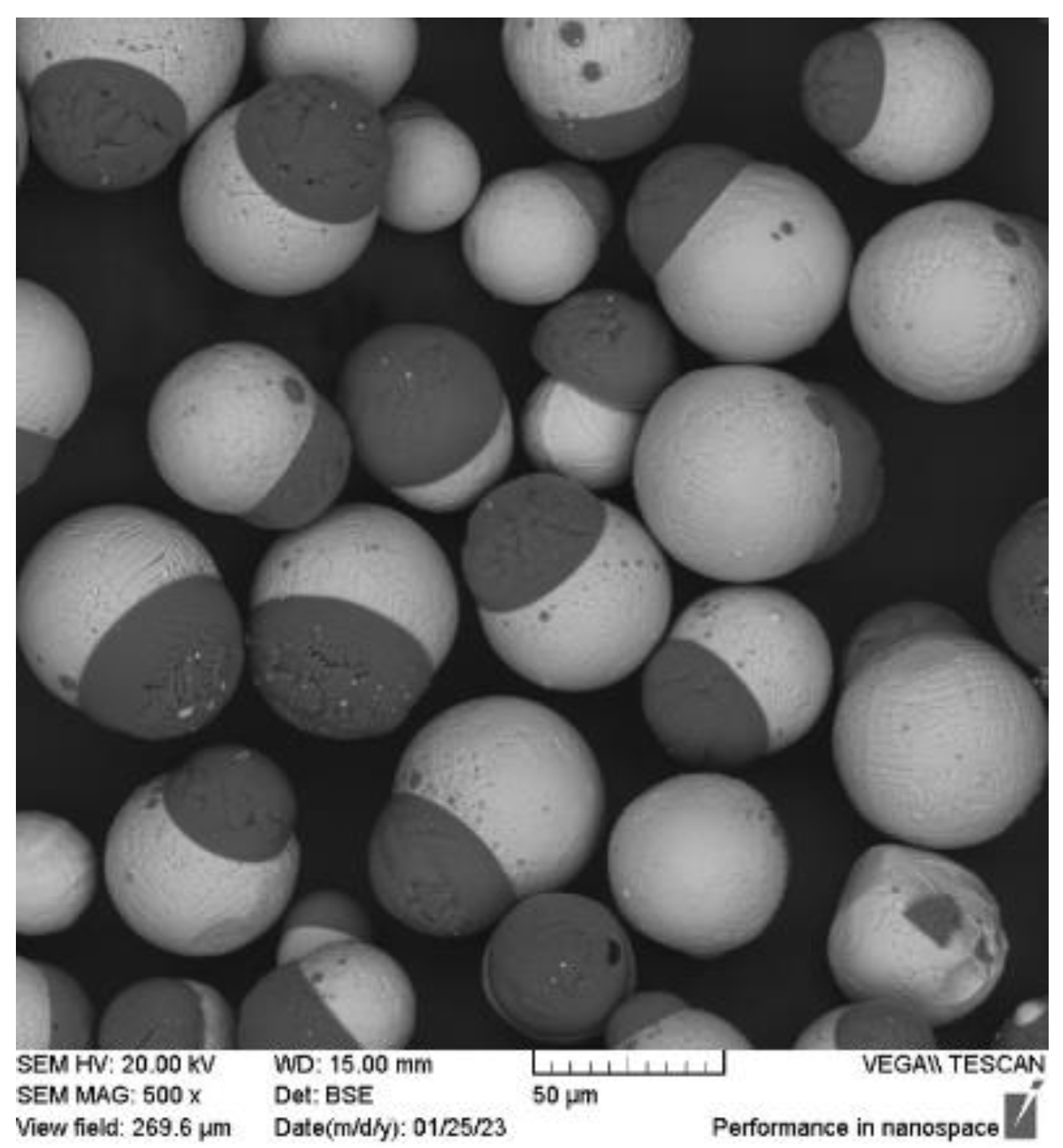

A parametric study was conducted by varying the power, gas composition, powder feed rate and the injection position of the powder. The results demonstrated that, for all parameter sets applied in the preliminary tests (

Table 1), a clear separation of alumina from steel was observed. The resulting particles were spherical and dense, with one side consisting of Al₂O₃ and the other of 316L (

Figure 7).

The primary challenge in producing homogeneous 316L/Al₂O₃ composite particles arises from the poor wettability between metals and oxide ceramics at high temperatures [

24]. To address this issue, we attempted to reduce the energy transferred to the particles, which is influenced by the plasma temperature (power, gas type and flow rates, powder feed rate) and the particle exposure time in the plasma (gas type and flow rates, injection probe position, powder feed rate) [

25]. The goal was to prevent constituent segregation by initiating rapid cooling immediately after melting.

The optimal parameters for plasma treatment of 316L/Al₂O₃ granules are detailed in

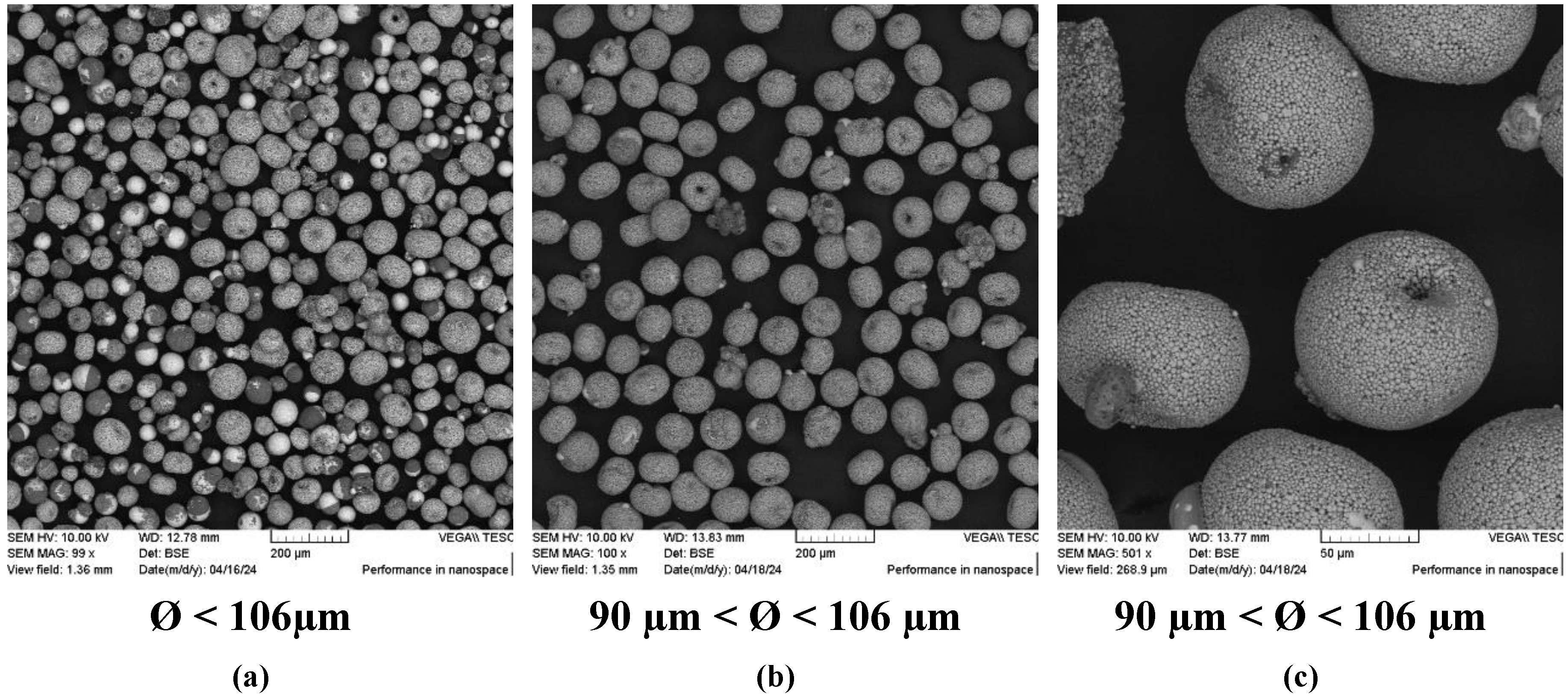

Table 2. The treatment exhibited varying effects depending on particle size. As shown in

Figure 8a, fine particles consistently displayed segregation, while larger particles were homogeneous. This discrepancy is attributed to the wide particle size distribution in the granules: the energy required for melting larger particles is excessive for smaller ones, thereby triggering segregation in the latter. As a result, it was not feasible to treat the entire powder batch uniformly. Post-spheroidization, the powder was sieved at 90 µm to isolate particles with homogeneous alumina and steel distributions (

Figure 8b and

Figure 8c).

3.3. Sintered Composites Microstructure and Hardness

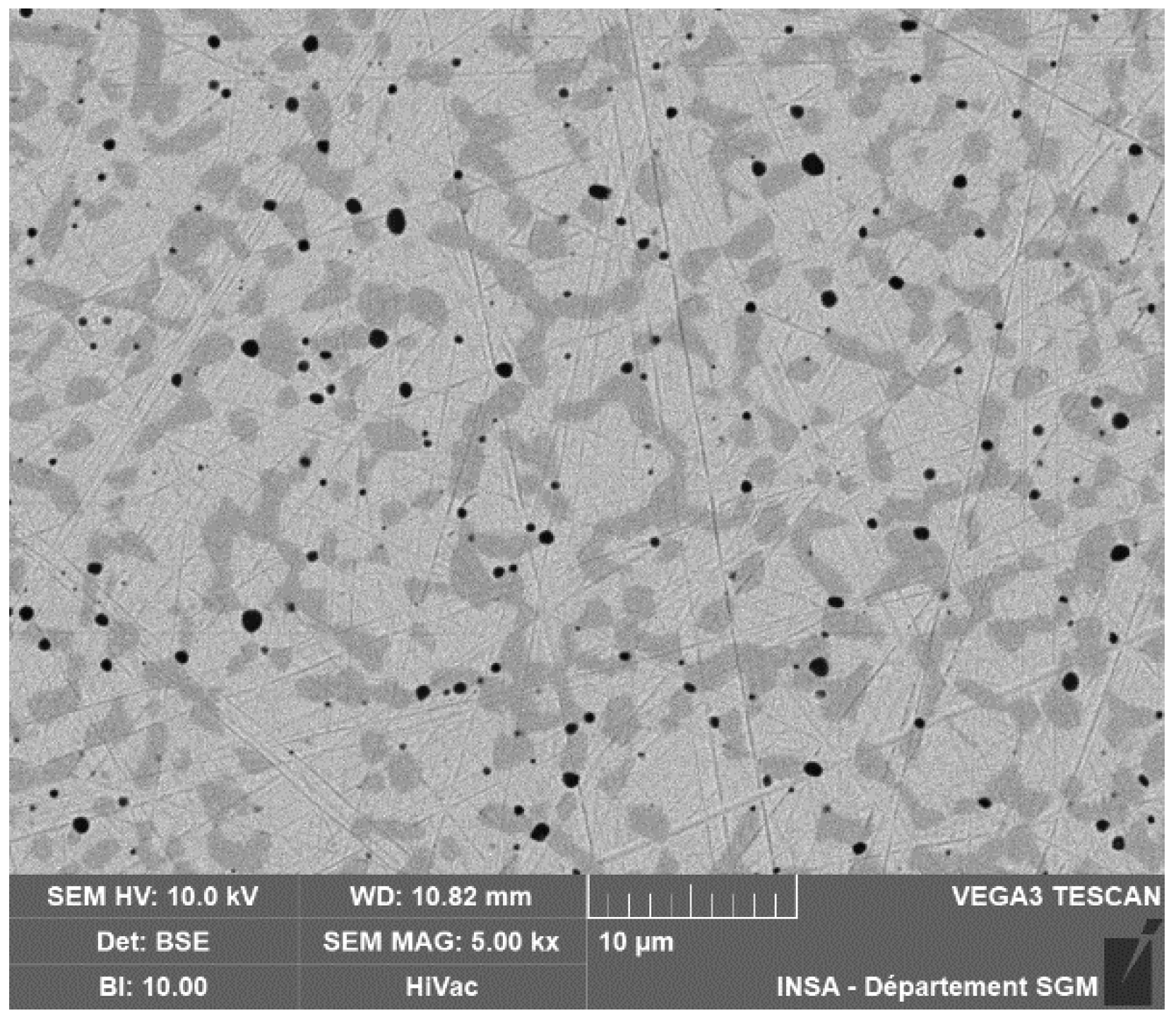

3.3.1. Sintered 316 L Stainless Steel

To optimize the densification of the composite, the sintering parameters were determined from the sintering of a stainless-steel sample. This sample was characterized by XRD analysis, as well as density and hardness measurements. The presence of two phases is observed: in dark gray, the ferritic phase and in light gray, the austenitic phase (

Figure 9). Pores with sizes in the µm range are also noted. The density is 99.5% of the theoretical density and the hardness is 3.7 GPa.

3.3.2. Composite Sintered from Ball-Milled Mixture

An initial composite was obtained by mixing the two powders using a dry ball-milling method, and then sintered.

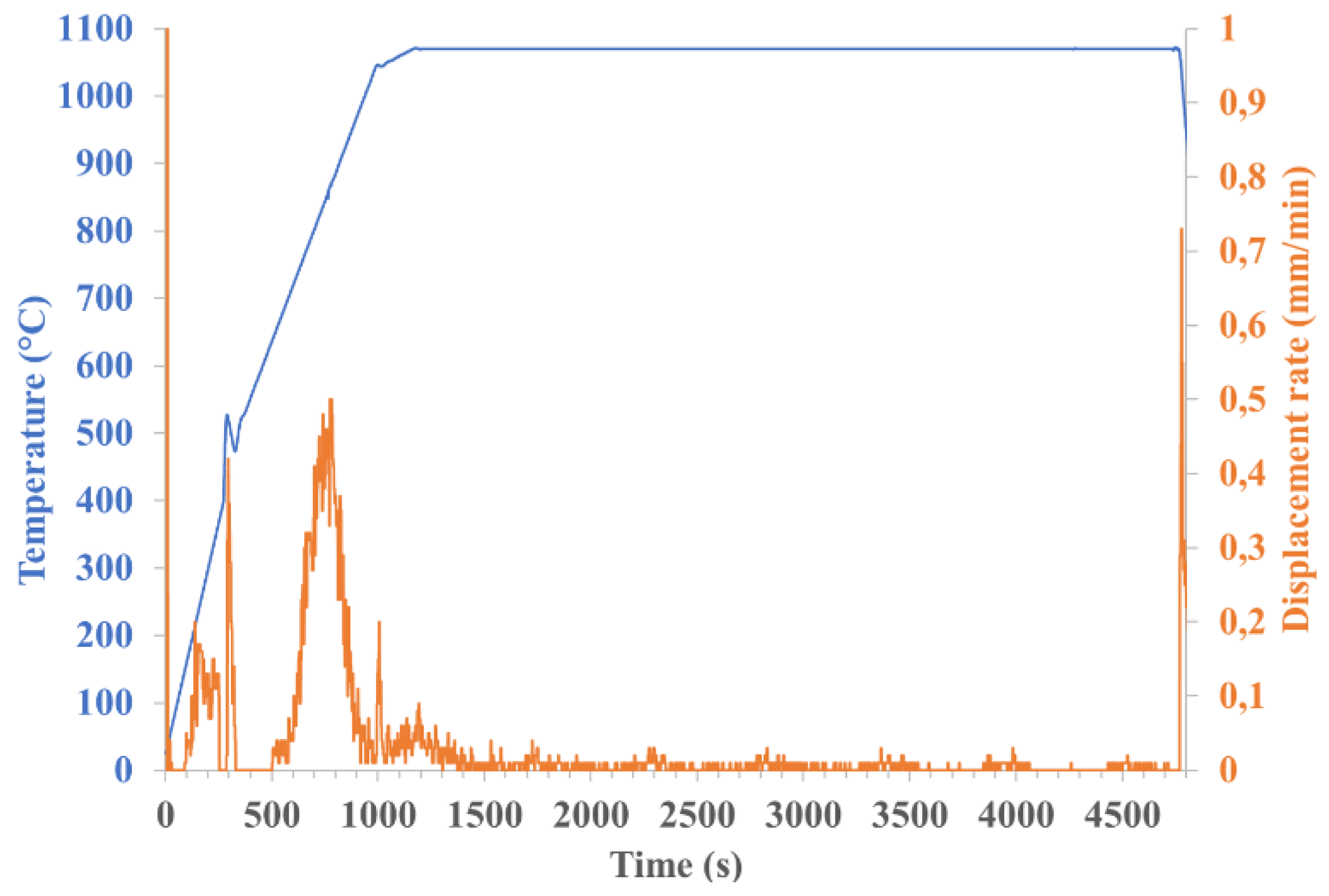

Figure 10 shows the evolution of piston displacement speed and temperature as a function of time for a 80 vol% 316L / 20 vol% Al₂O₃ composite. Initially, there is a densification zone corresponding to particle rearrangement (between 0 and 300 s), followed by a sintering zone with a significant densification peak at around 800 °C.

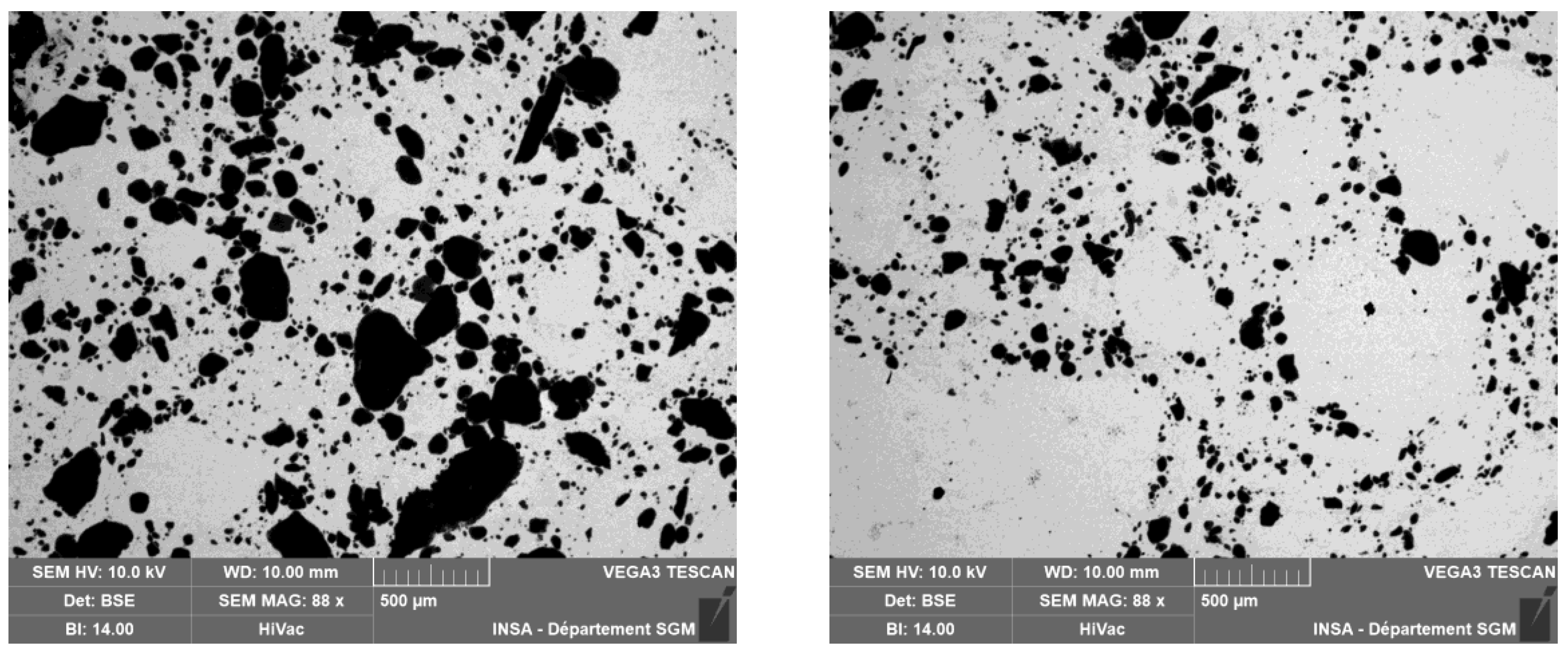

The

Figure 11 shows the microstructure of a ball-milled composite. It appears that the alumina powder is not well distributed, it is agglomerated in clusters. The density is only 91.8 % of the theoretical density of the composite and the hardness 4.3 GPa.

3.3.3. Composite Sintered from the Spray-Granulated Granules

The granules from slurry 3 were sintered using the same sintering parameters. The microstructures of the sintered samples are shown in

Figure 12. The distribution of alumina within a granule is more or less homogeneous. However, after sintering, traces of the granules obtained by atomization are still visible, the granules have not been properly destroyed. This explains the lower densification of the sintered samples. Indeed, the density of the sintered composite is 97.3 % of the theoretical density (lower than that of stainless steel alone) and the hardness is 4.6 GPa (higher than that of stainless steel).

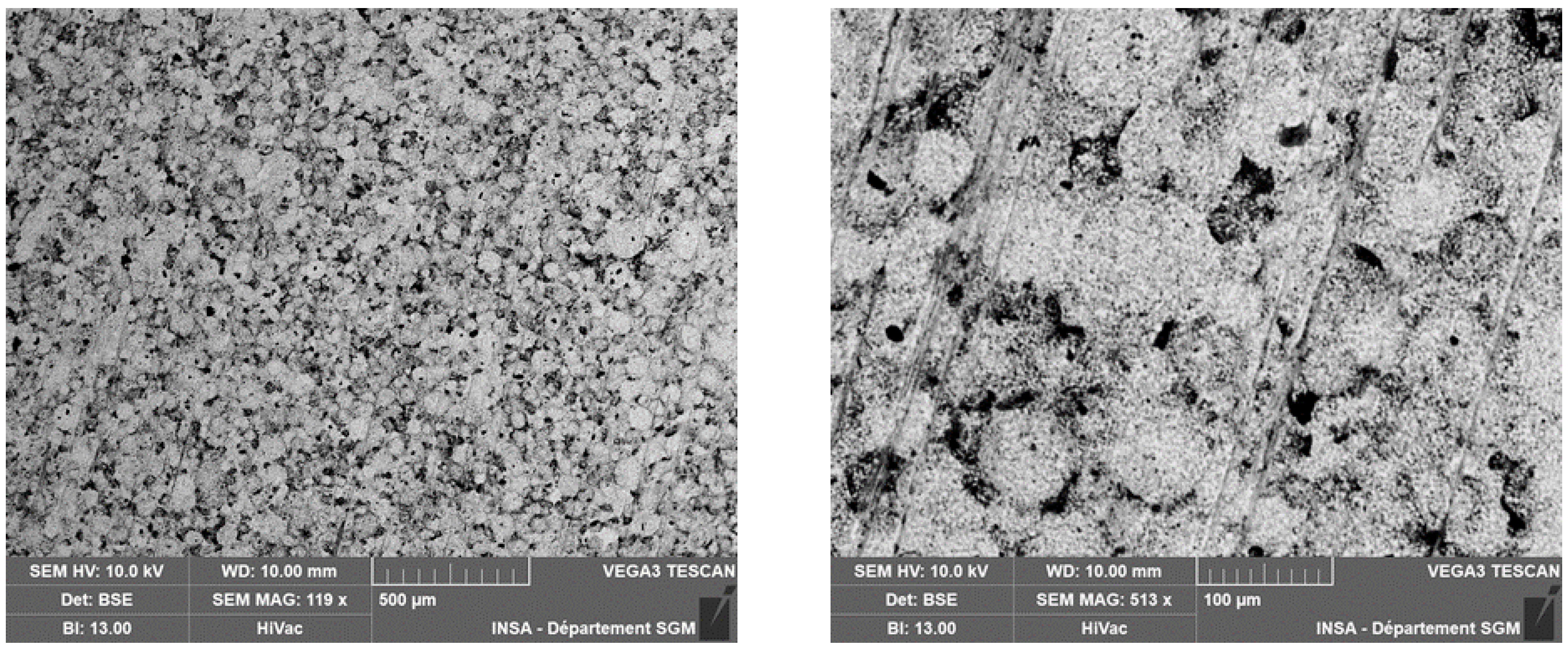

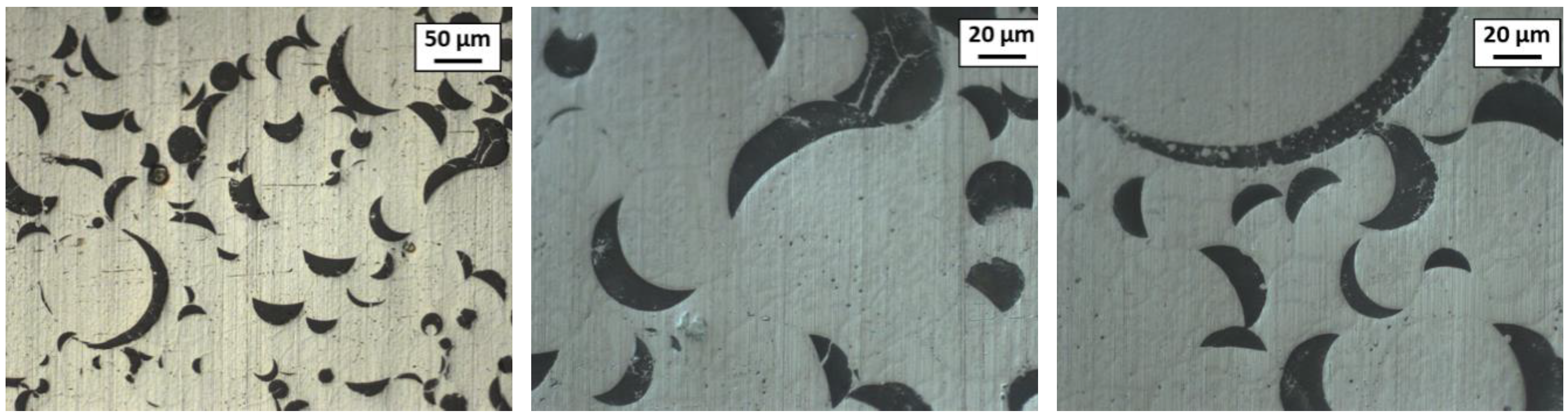

3.3.4. Composite Sintered from the Granules Spheroidized with the Preliminary Parameters

Concerning the composite sample sintered from the spheroidized granules with preliminary parameters (

Table 2, test 3), the microstructure is shown in

Figure 13. Note the presence of large, moon-shaped alumina clusters (in black), which indicates that the alumina melted during the spheroidization process and clustered around the edges of the granules. The density of this composite is 98.1 % and the hardness is 4.1 GPa. Compared with the simply atomized granules, there is a drop in hardness due to the poor homogeneity of the alumina. Spheroidization also reduced the presence of pores in the sintered pellet, explaining the increase in density.

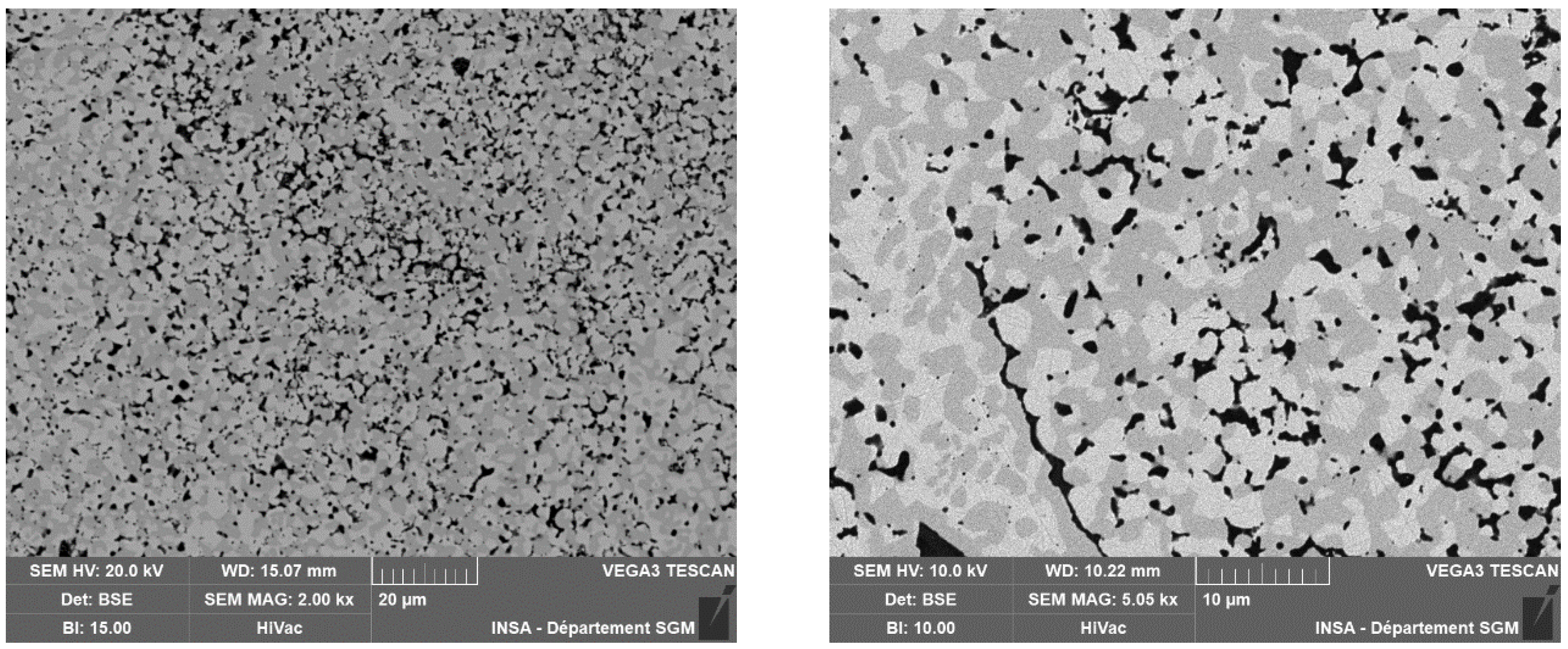

3.3.5. Composites Sintered from the Granules Spheroidized with the Optimal Parameters

The SEM images (

Figure 14) reveal the homogeneous distribution of alumina (in black) as well as the austenitic and ferritic phases of the steel. The measured density of the sintered composite is 98.9 % of the theoretical density and the hardness is 5.4 GPa, which is higher than that of the stainless-steel sample.

3.3.6. Summary of the Results on Sintered Samples

Table 5 summarises the results of density and harness obtained after sintering 80 vol% 316L / 20 vol% Al₂O₃ composite samples from different raw powders: ball-milled mixture, spray granulated powders, spray granulated granules spheroidized with the preliminary parameters, spray granulated granules spheroidized with the optimal parameters. These results are also compared with pure sintered 316L powder. All these results are obtained with identical sintering parameters, as described in section 2.5). The highest density and hardness are obtained for the composite material sintered from a powder manufactured by a combination of spray-granulation and spheroidization with optimised parameters.

4. Conclusions

We have demonstrated the feasibility of a hybrid process that combines spray-granulation, RF plasma treatment and SPS consolidation for the fabrication of 316L/Al₂O₃ composites. The optimisation of the suspension formulation through precise adjustment of the pH, solid loading, and selection of an appropriate dispersant resulted in a homogeneous dispersion of the constituents, thereby limiting the agglomeration of alumina particles and enabling control over the granulometric distribution.

The optimization of the spheroidization parameters was essential for minimizing phase separation and encouraging partial recrystallization of the alumina onto the 316L. This was achieved by adjusting the plasma power, gas flow rates and powder injection position. However, the observed size-dependent behaviour highlights the complexity of heat transfer from the plasma to the particles. This requires adjustments to the granulometric distribution and more precise control of the processing parameters to prevent the over-melting of fine particles.

The composite samples, produced by SPS at a constant pressure of 64 MPa and under a controlled thermal cycle, exhibited a final density of 98.9 % and a hardness of 5.4 GPa. Further microstructural analyses with SEM and microtomography revealed a uniform distribution of alumina within the 316L matrix, accompanied by a balanced distribution of austenitic and ferritic regions. This achieved an optimal balance between ductility and mechanical strength.

These results indicate that the developed approach opens a promising pathway for the fabrication of metal/ceramic composites. The combination of spray-granulation and RF plasma treatment provides enhanced control over the metal/ceramic interfaces, while the characterisations of the SPS-prepared samples reveal a homogeneous phase distribution with excellent mechanical properties for applications requiring superior wear resistance and thermal stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Elodie Cabrol, Sandrine Cottrino, Hocine Si-Mohand and Gilbert Fantozzi; Investigation, Elodie Cabrol, Sandrine Cottrino, Hocine Si-Mohand and Gilbert Fantozzi; Writing – original draft, Elodie Cabrol, Sandrine Cottrino, Hocine Si-Mohand and Gilbert Fantozzi.

References

- Auger JM.; Etude de la frittabilité de composites céramique-métal (alumine-acier inoxydable 316L) – Application à la conception et à l’élaboration de pieces multimatériaux multifonctionnelles architectures, PhD manuscript, 2010.

- Dudek A.; Włodarczyk R. Composite 316L+Al₂O₃ for Application in Medicine. Materials Science Forum 2012, 706-709, 643-648. https://www.scientific.net/MSF.706-709.643.

- Canpolat O.; Çanakçı A.; Erdemir F. SS316L-Al₂O₃ functionally graded material for potential biomedical applications. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2023, 293 . [CrossRef]

- Kuforiji C.; Nganbe M. Fabrication and characterisation of SS316L-Al₂O₃ composites for wear applications. In proceeding of the International Conference & Exhibition on Advanced and Nanomaterials, Ottawa, Canada, 10-12 August 2015.

- Coovattanachai O.; Mima S.; Yodkaew T.; Krataitong R.; Morkotjinda M.; Daraphan A.; Tosangthum N.; Vetayanugul B.; Panumas A.; Poolthong N.; Tongsri R. Effect of admixed ceramic particles on properties of sintered 316L stainless steel, In proceeding of the International Conference on Powder Metallurgy and Particulate Materials, San Diego, California, 18 - 21 June 2006.

- Canpolat O.; Çanakçı A.; Erdemir F. Evaluation of microstructure, mechanical, and corrosion properties of SS316L/Al2O3 composites produced by hot pressing. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2022, 280. [CrossRef]

- Kracun A.; Tehnovnik F.; Kafexhiu F.; Kosec T.; Jenko D.; Podgornik B. Stainless steel matrix composites reinforced with ceramic particles through ingot casting process. MATEC Web of conferences 2018, 188, . [CrossRef]

- Li X.; Willy HJ.; Chang S.; Lu W.; Herng TS.; Ding J. Selective laser melting of stainless steel and alumina composite: Experimental and simulation studies on processing parameters, microstructure and mechanical properties. Materials & Design 2018, 145. [CrossRef]

- Gülsoy HÖ.; Baykara T.; Özbek S. Injection moulding of 316L stainless steels reinforced with nanosize alumina particles. Powder Metallurgy 2011, 54, 360-365. [CrossRef]

- Ben Zine HR.; Horváth ZE.; Balázsi K.; Balázsi C. Novel Alumina Dispersion-Strengthened 316L Steel Produced by Attrition Milling and Spark Plasma Sintering. Coatings 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Baross T.; Ben Zine H.R.; Bereczki P.; Palankai M.; Balazsi K.; Balazsi C.; Veres G. Diffusion Bonding of Al2O3 Dispersion-Strengthened 316L composite by Gleeble 3800. Materials 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Panumas A.; Yotkaew T.; Krataitong R.; Morakotjinda S.; Daraphan A.; Tosangthum N.; Coovattanachai O.; Vetayanugul B.; Tongsri R. Preparation of 316L-Al₂O₃ Composite. In proceeding of the 19th Conference of the Mechanical Engineering Network of Thailand,- Songkhla, Thailand, 19-21 October 2005.

- Tongsri R.; Asavavisithchai S.; Mateepithukdharm C.; Piyarattanatrai T.; Wangyao P. Effect of Powder Mixture Conditions on Mechanical Properties of Sintered Al₂O₃-SS 316L Composites under Vacuum Atmosphere. Journal of Metals, Materials and Minerals 2007, 17, 81-85. https://digital.car.chula.ac.th/jmmm/vol17/iss1/13/.

- Lia B.; Jina H.; Dinga F.; Baia L.; Yuan F. Fabrication of homogeneous Mo-Cu composites using spherical molybdenum powders prepared by thermal plasma spheroidization process. International Journal of Refractory Metals & Hard Materials 2018, 73, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Tan Z.; Zhou Z.; Wu X.; Wang Y.; Shao W.; Guo X.; Zhou Z.; Yang Y.; Wang G.; He D. In situ synthesis of spherical W–Mo alloy powder for additive manufacturing by spray granulation combined with thermal plasma spheroidization. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2021, 95. [CrossRef]

- Samokhin A. V.; Alekseev N. V.; Dorofeev A. A.; Fadeev A. A.; Sinayskiy M. A.; Zavertiaev I. D.; Grigoriev Y. V. Preparation of spheroidized W−Cu pseudo-alloy micropowder with sub-micrometer particle structure using plasma technology. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2024, 34, 592−603. [CrossRef]

- Yan Z.; Xiao M.; Mao X.; Khanlari K.; Shi Q.; Liu X. Fabrication of spherical WC-Co powders by radio frequency inductively coupled plasma and a consequent heat treatment. Powder Technology 2021, 385, 160–169. [CrossRef]

- Guo S.; Hao Z.; Ma R.; Wang P.; Shi L.; Shu Y.; He J. Preparation of spherical WC-Co powder by spray granulation combined with radio frequency induction plasma spheroidization. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 12372–12380. [CrossRef]

- Gao X.; Mo Z.; Hao Z.; Ma R.; Wang P.; Shu Y.; He J. Fabrication of spherical W–ZrC powder for additive manufacturing by spray granulation combined with plasma spheroidization. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 28, 4222–4228. [CrossRef]

- Khor K.A.; Li Y. Crystallization behaviors in the plasma-spheroidized alumina/zircon mixtures. Materials Letters 2001, 48, 57-63. [CrossRef]

- Sun S.; Ma Z.; Liu Y.; Gao L.; Liu L.; Zhu S. Preparation and characterization of ZrB2/SiC composite powders by induction plasma spheroidization technology. Ceramics International 2019, 45, 1258–1264. [CrossRef]

- Li F.; He P.; Li G.; Ye L.; Zhang B.; Sun C.; Xing Y.; Wang Y.; Duan X.; Liang X. Microstructure development of plasma sprayed dual-phase high entropy ceramic coating derived from spray dried and induction plasma spheroidized powder. Ceramics International 2024, 50, 24576–24593. [CrossRef]

- Massard Q.; Si-Mohand H.; Cabrol E. Study on the recycling of 100Cr6 powder by plasma spheroidization for laser powder bed fusion. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 27, 5889-5895. [CrossRef]

- Jupille J.; Lazzari R. Improving the wetting of oxides by metals. Journal of optoelectronics and advanced materials 2006, 8, 901–908.

- Sehhat MH.; Chandler J.; Yates Z. A review on ICP powder plasma spheroidization process parameters. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2022, 103. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

XRD analysis of 316L powder.

Figure 1.

XRD analysis of 316L powder.

Figure 2.

SEM observation of powders (a) 316L powder (b) Alumina powder.

Figure 2.

SEM observation of powders (a) 316L powder (b) Alumina powder.

Figure 3.

Particle size distribution of initial powders.

Figure 3.

Particle size distribution of initial powders.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of plasma spheroidization [

23].

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of plasma spheroidization [

23].

Figure 5.

SEM observations of the different granule batches.

Figure 5.

SEM observations of the different granule batches.

Figure 6.

X-ray tomography slide of granules batch 1.

Figure 6.

X-ray tomography slide of granules batch 1.

Figure 7.

SEM observation of segregation between alumina (in black) and steel (in grey) after preliminary spheroidization tests (image given for test 3).

Figure 7.

SEM observation of segregation between alumina (in black) and steel (in grey) after preliminary spheroidization tests (image given for test 3).

Figure 8.

SEM observations of particles after optimal plasma treatment.

Figure 8.

SEM observations of particles after optimal plasma treatment.

Figure 9.

SEM microstructure of sintered 316L stainless steel.

Figure 9.

SEM microstructure of sintered 316L stainless steel.

Figure 10.

Evolution of temperature and piston displacement during the sintering treatment of composite (80 vol% 316L / 20 vol% Al₂O₃).

Figure 10.

Evolution of temperature and piston displacement during the sintering treatment of composite (80 vol% 316L / 20 vol% Al₂O₃).

Figure 11.

SEM microstructure of the composite sintered from ball-milled mixture.

Figure 11.

SEM microstructure of the composite sintered from ball-milled mixture.

Figure 12.

SEM microstructure of the composite sintered from the spray-granulated granules.

Figure 12.

SEM microstructure of the composite sintered from the spray-granulated granules.

Figure 13.

Optical microscopic microstructure of the composite sintered from the granules spheroidized with the preliminary parameters (parameters 3).

Figure 13.

Optical microscopic microstructure of the composite sintered from the granules spheroidized with the preliminary parameters (parameters 3).

Figure 14.

SEM microstructure of the composite sintered from the granules spheroidized with the optimal parameters.

Figure 14.

SEM microstructure of the composite sintered from the granules spheroidized with the optimal parameters.

Table 1.

Spheroidization parameters for preliminary tests.

Table 1.

Spheroidization parameters for preliminary tests.

| |

Preliminary parameters |

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| Power (kW) |

40 |

30 |

30 |

20 |

| Central gas (slpm) |

Ar : 15 |

| Sheath gas (slpm) |

Ar: 55 / H2: 10 |

Ar: 55 |

| Carrier gas (slpm) |

Ar: 5 |

| Injection probe position |

Centre |

-10mm |

Centre |

| Powder feed rate (kg/h) |

8 |

4 |

2 |

Table 2.

Spheroidization parameters for optimal treatment.

Table 2.

Spheroidization parameters for optimal treatment.

| |

Optimal parameters |

| Power (kW) |

20 |

| Central gas (slpm) |

Ar : 15 |

| Sheath gas (slpm) |

Ar: 55 |

| Carrier gas (slpm) |

Ar: 5 |

| Injection probe position |

-10mm |

| Powder feed rate (kg/h) |

4 |

Table 3.

Slurries parameters.

Table 3.

Slurries parameters.

| Slurries batches |

316L

(vol%)

|

Al2O3

(vol%)

|

Dispersant ratio (wt%) |

Solid loading ratio

(wt%)

|

pH |

| 1 |

80 |

20 |

2 PEG |

40 |

7 |

| 2 |

80 |

20 |

2 PVA |

30 |

11 |

| 3 |

80 |

20 |

0.5 PAA |

50 |

11 |

Table 4.

Density and size distribution characteristic values for the different granules batches.

Table 4.

Density and size distribution characteristic values for the different granules batches.

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

D10 : 1 µm

D50 : 34 µm

D90 : 266 µm |

D10 : 2 µm

D50 : 26 µm

D90 : 70 µm |

D10 : 2 µm

D50 : 8 µm

D90 : 36 µm |

| Density : 6.6 g/cm3

|

Density : 6.9 g/cm3

|

Density : 7.1 g/cm3

|

Table 5.

Results of relative density and hardness of the sintered materials.

Table 5.

Results of relative density and hardness of the sintered materials.

| |

|

Relative density

(%)

|

Hardness

(GPa)

|

| Pure 316L |

99.5 |

3.7 |

| Composite 80 vol% 316L / 20 vol% Al2O3 |

Ball-milled mixture |

91.8 |

4.3 |

| Spray-granulated granules |

97.3 |

4.6 |

| Spheroidized granules with the preliminary parameters |

98.1 |

4.1 |

| Spheroidized granules with the optimal parameters |

98.9 |

5.4 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).