Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Brief Notes on Various ML Algorithms

2.1.1. Support Vector Machine

2.1.2. SGD Regressor

2.1.3. Bayesian Ridge

2.1.4. Automatic Relevance Determination Regression

2.1.5. (. e) Passive-Aggressive Regressor

2.1.6. Theil-Sen Regressor

2.1.7. (. g) Linear Regression

2.1.8. Random Forest

2.1.9. Backpropagation Neural Networks

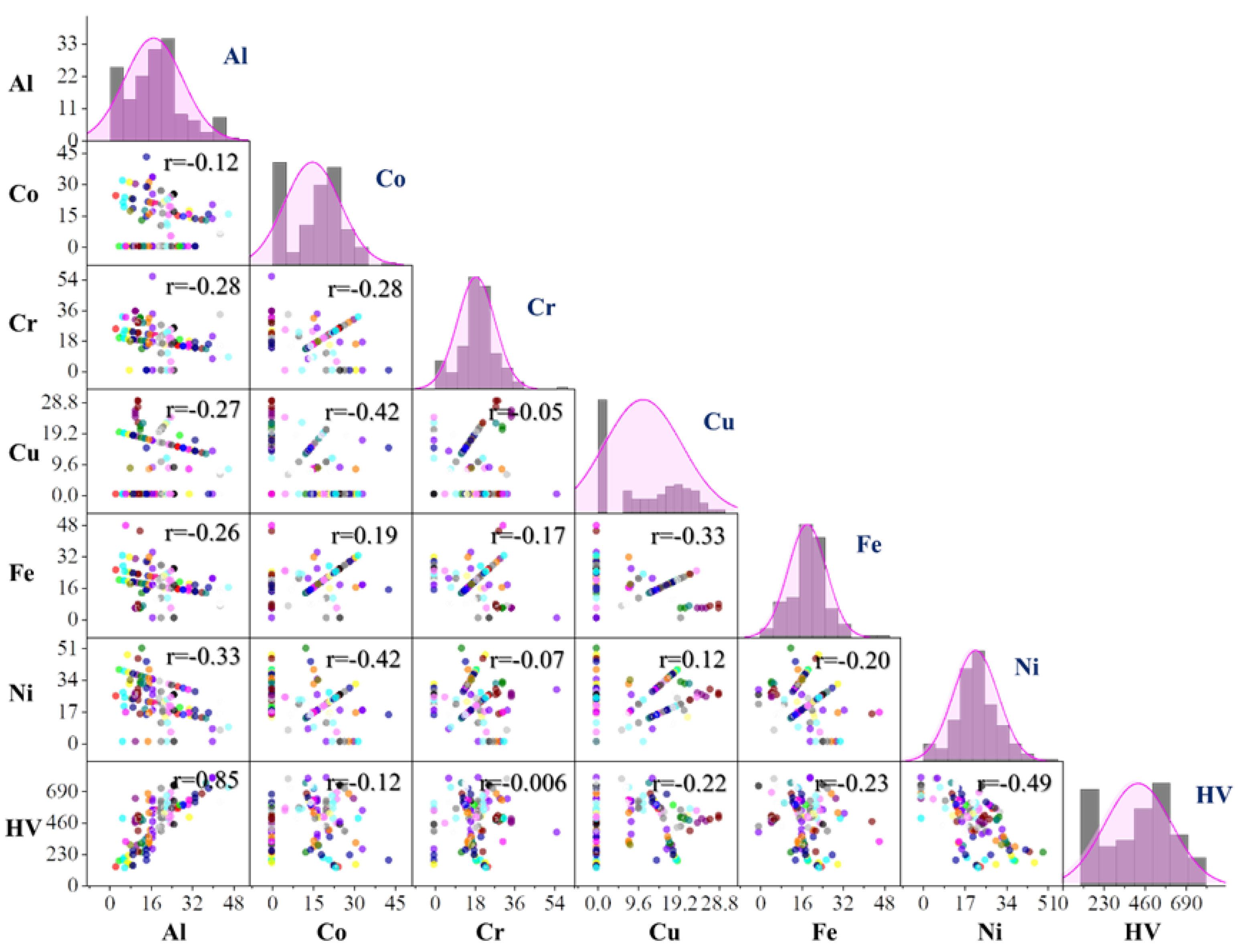

2.2. Data Processing

3. Results

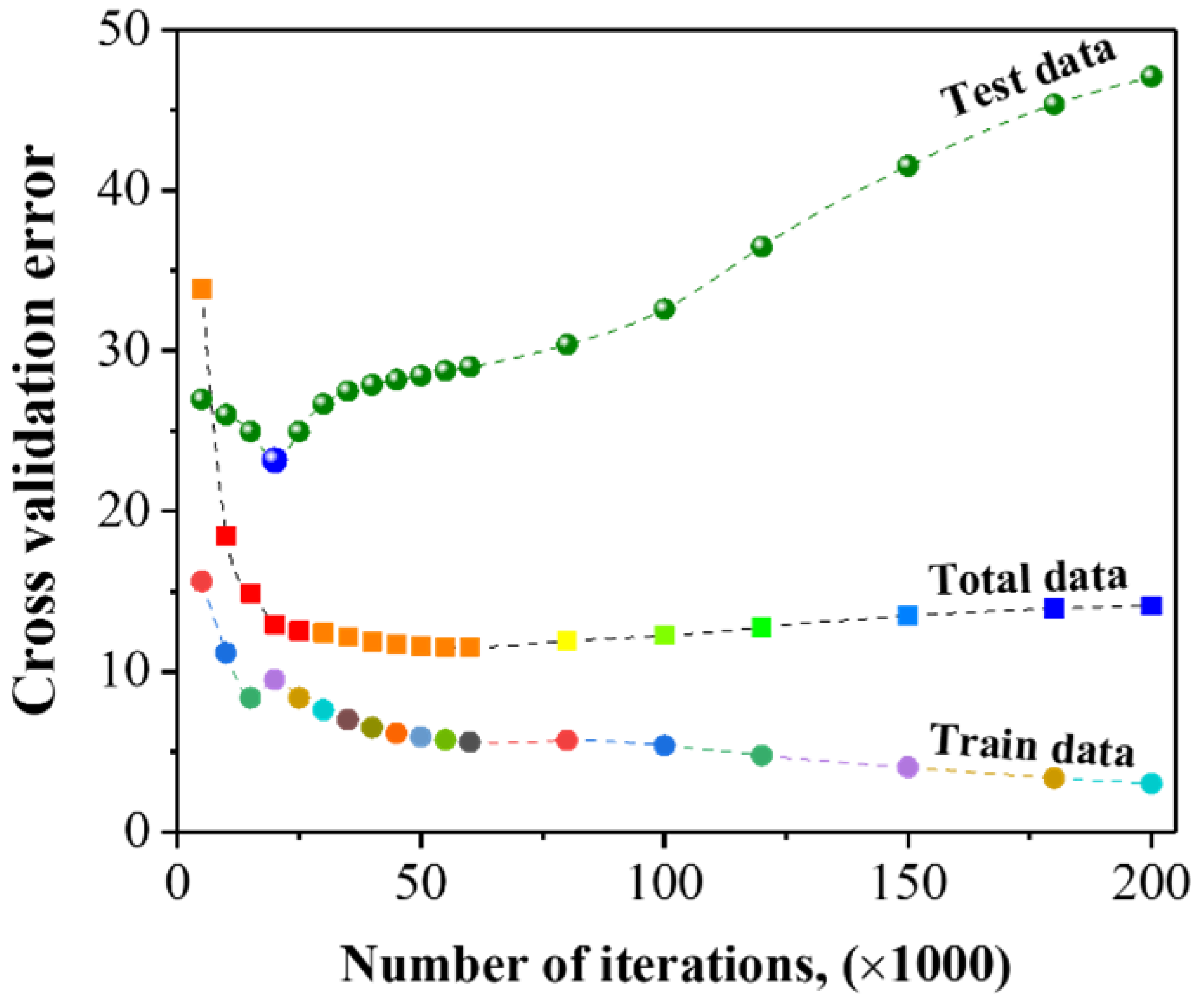

4.1. Model Development

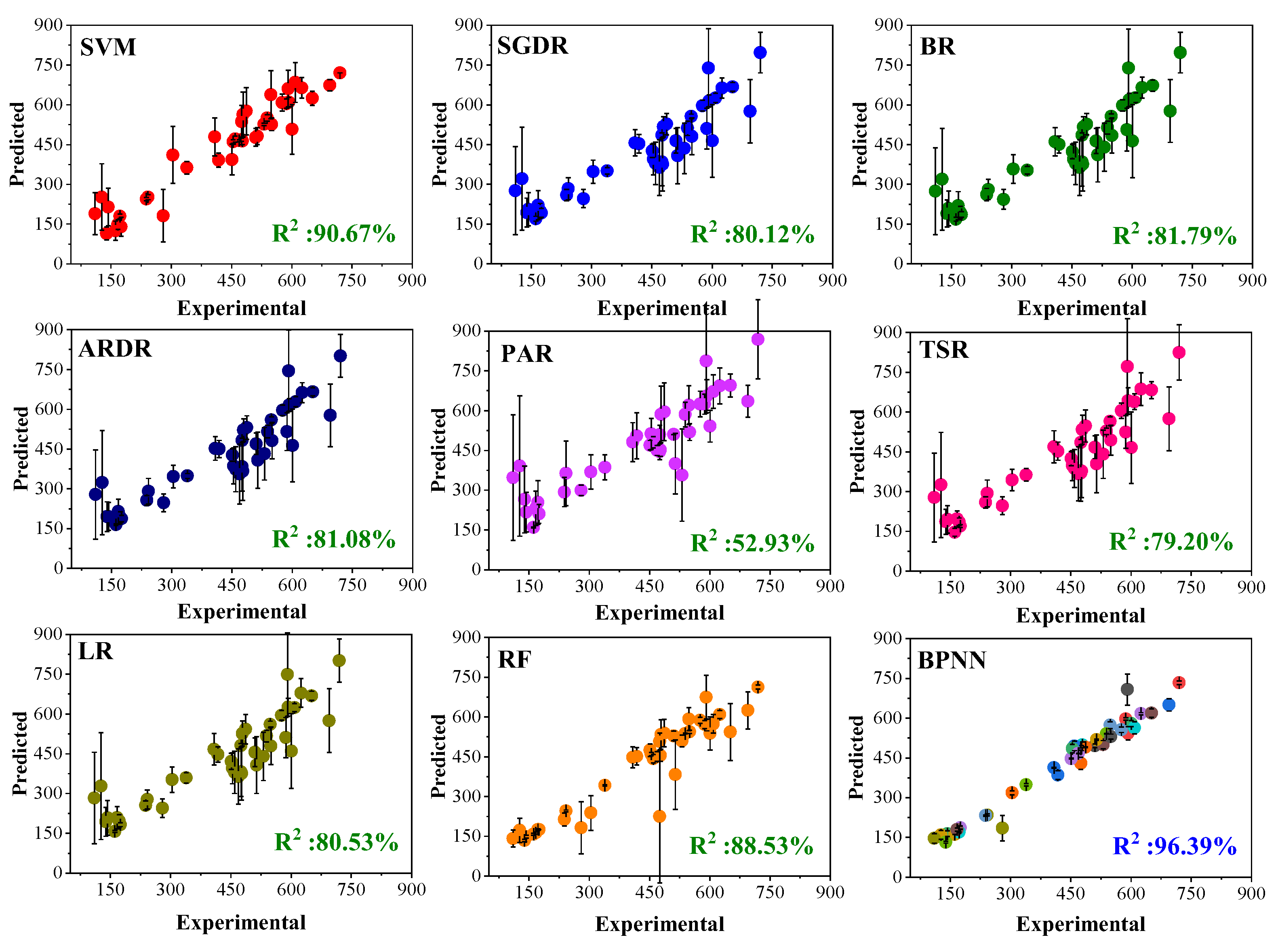

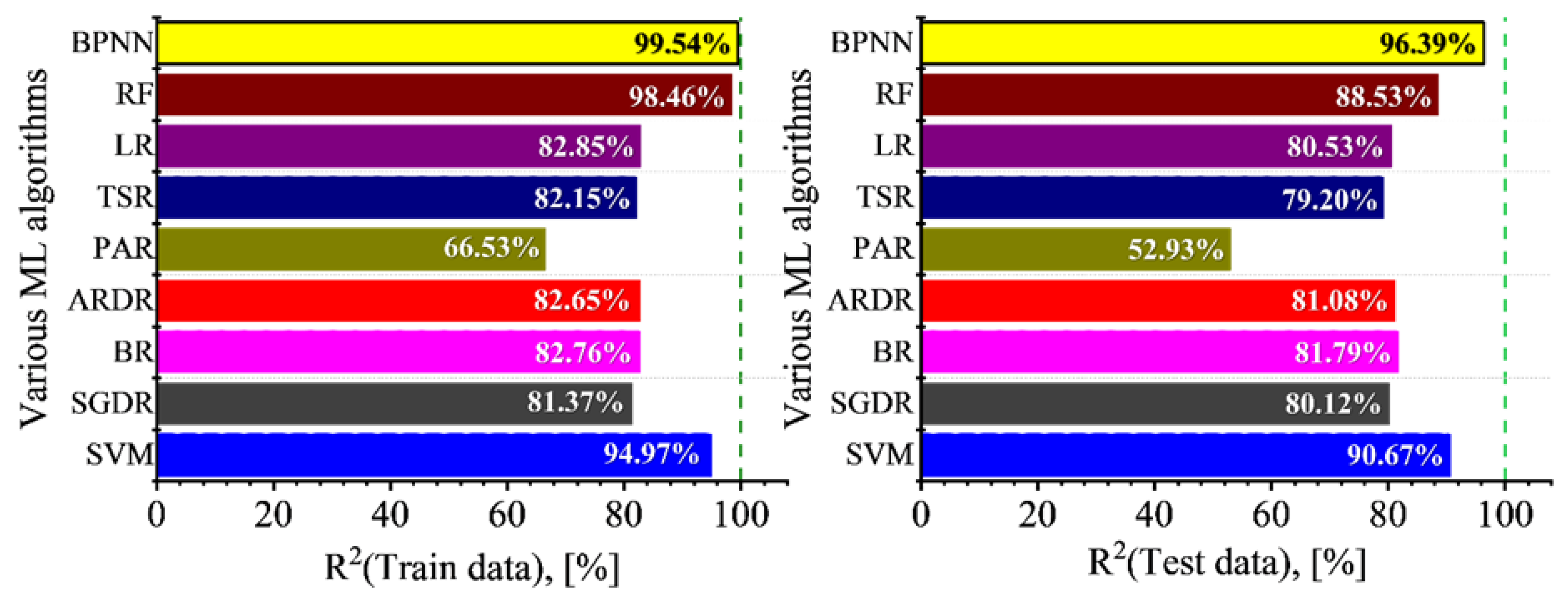

4.2. Comparing Prediction Accuracy of Various ML Algorithms

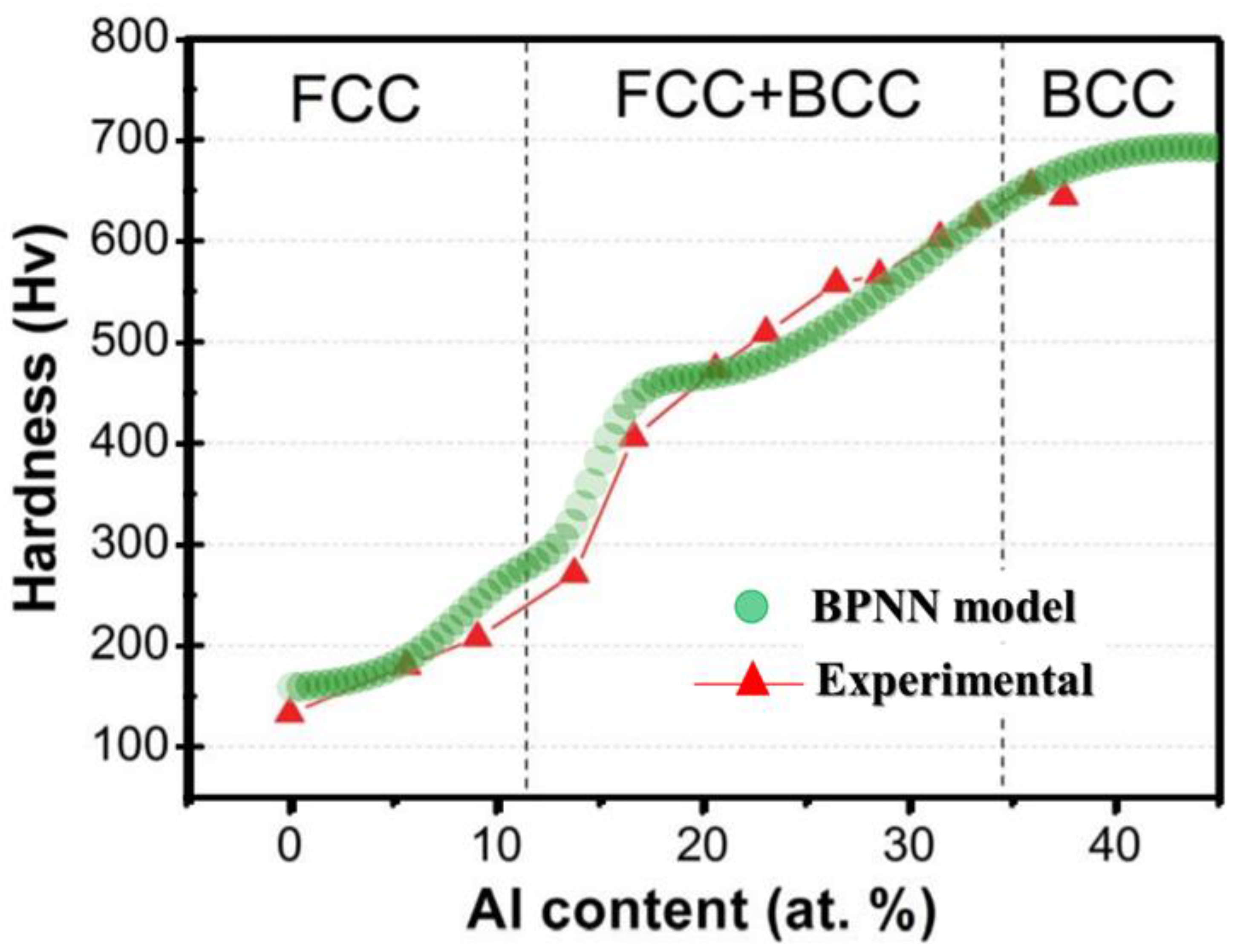

4.3. Validation of BPNN Model

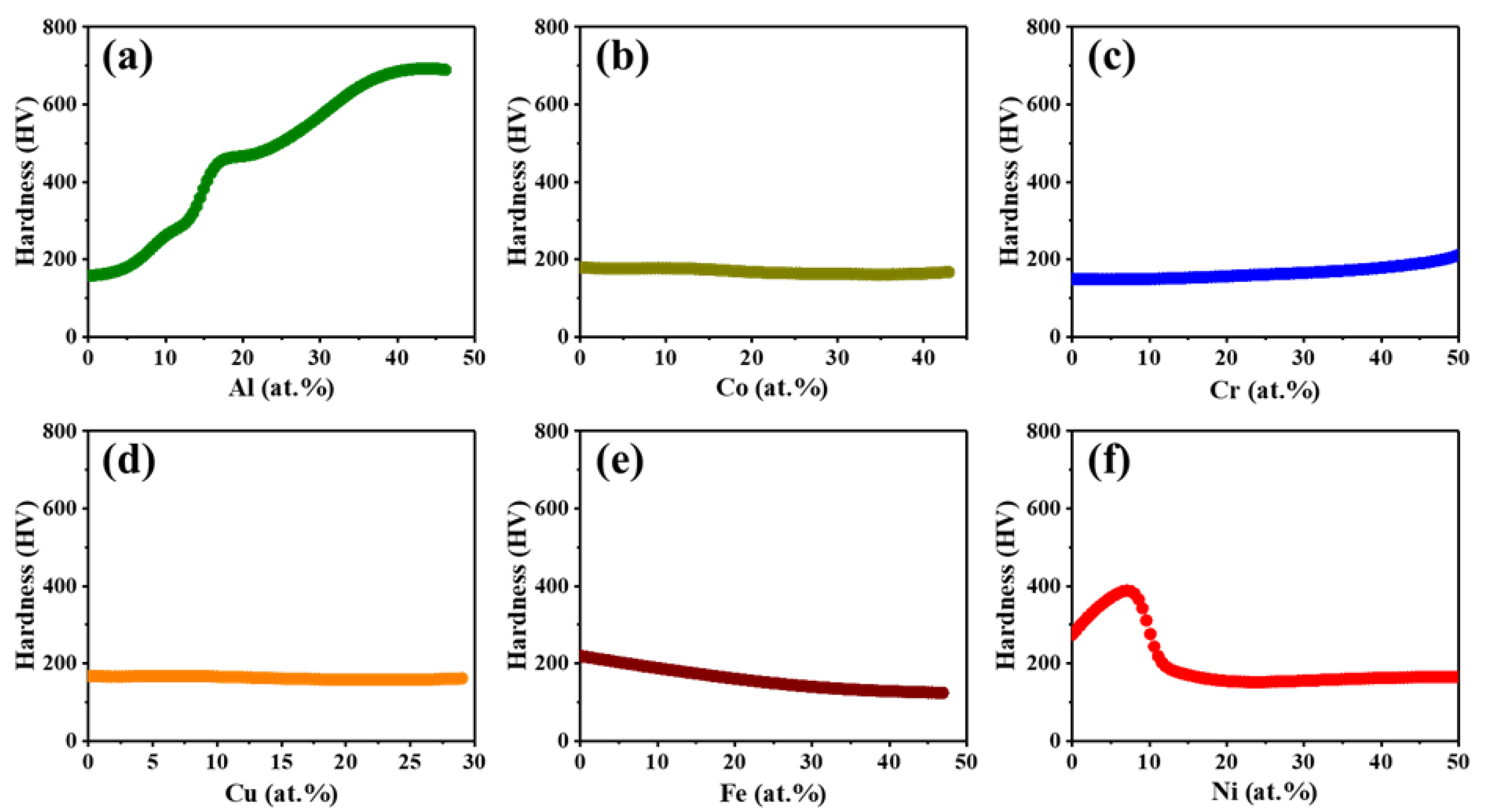

4.4. Effect of Element Concentration on the Hardness

| S No | Composition (at. %) | Hardness (Exp.) |

Hardness (BPNN) |

Error | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | Co | Cr | Cu | Fe | Ni | |||||

| 1 | 0 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 174 | 160.63 | 13.37 | [7] |

| 2 | 7 | 23.3 | 23.3 | 0 | 23.3 | 23.3 | 125 | 113.68 | 11.32 | [7] |

| 3 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 11.1 | 0 | 22.2 | 564 | 552.28 | 11.72 | [7] |

| 4 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 558 | 517.52 | 40.48 | [7] |

| 5 | 27.3 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 0 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 482 | 462.23 | 19.77 | [7] |

| 6 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 204 | 197.94 | 6.06 | [7] |

| 7 | 33.3 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 0 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 510 | 542.74 | 32.74 | [7] |

| 8 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 9.1 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 563 | 560.96 | 2.04 | [7] |

| 9 | 11.1 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 0 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 160 | 172.77 | 12.77 | [7] |

| 10 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 410 | 409.6 | 0.4 | [7] |

| 11 | 0.5 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 208 | 161.84 | 46.16 | [37] |

| 12 | 19.9 | 0.5 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 473 | 469.61 | 3.39 | [37] |

| 13 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 0.5 | 19.9 | 418 | 407.25 | 10.75 | [37] |

| 14 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 0.5 | 423 | 466.72 | 43.72 | [37] |

4.5. Validation of the Model Predictions with Experimental Results

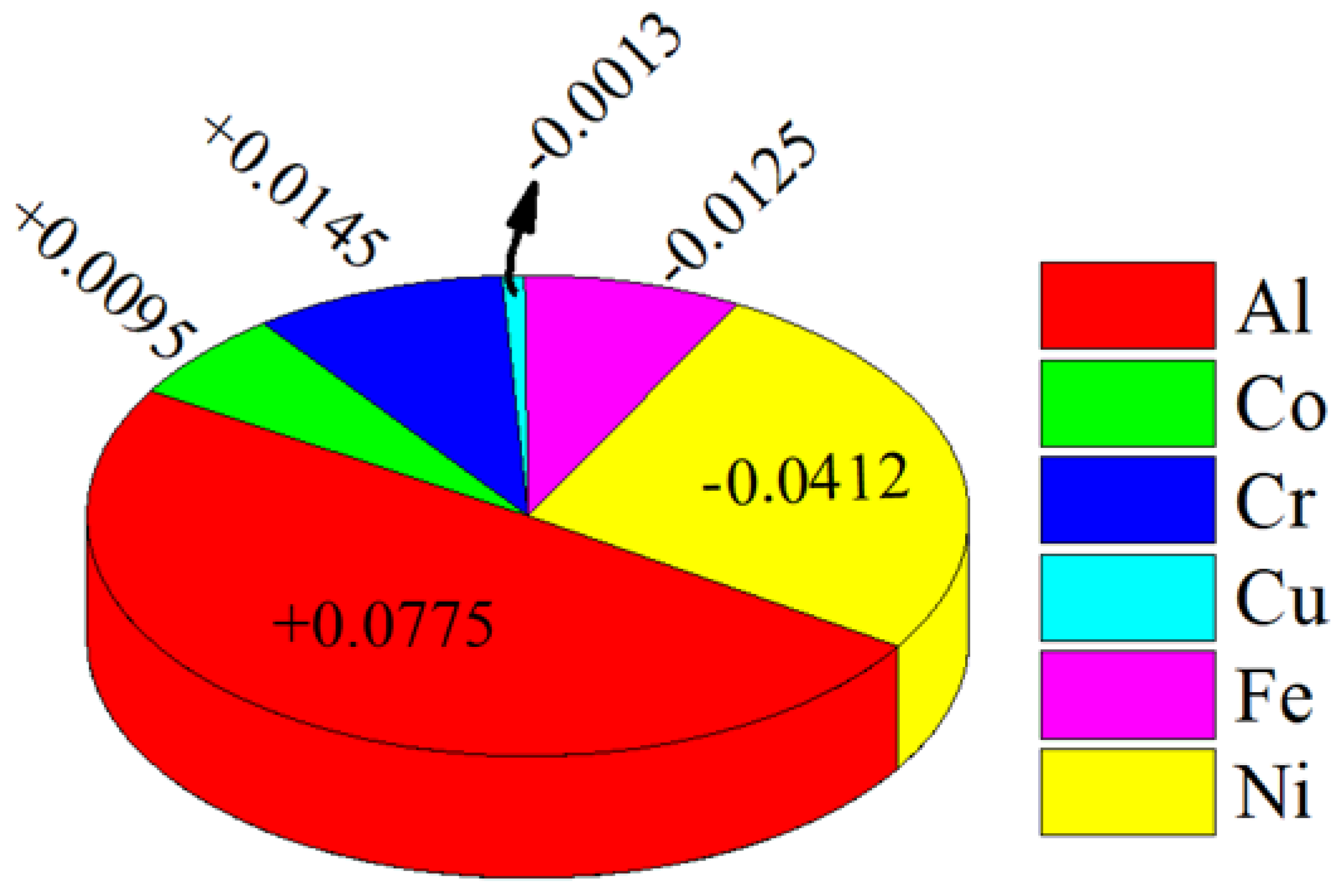

4.6. Significance of Alloy Components on the Hardness

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPNN | Back propagation neural network |

| IRI | Index of relative importance |

| HEA | High entropy alloy |

| FCC | Face centered cubic |

| BCC | Body centered cubic |

Appendix A

References

- George, E.P.; Curtin, W.A.; Tasan, C.C. High Entropy Alloys: A Focused Review of Mechanical Properties and Deformation Mechanisms. Acta Mater. 2020, 188, 435–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, K.; Vecchio, K.S. Searching for high entropy alloys: A machine learning approach. Acta Mater. 2020, 198, 178–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Hao, Y.; An, B.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.-A. Microstructure and mechanical properties of high entropy CrMnFeCoNi alloy processed by electopulsing-assisted ultrasonic surface rolling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lu, J.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y. High-entropy alloy: challenges and prospects. Mater. Today 2016, 19, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Byeon, S.; Kim, H.S.; Jin, H.; Lee, S. Deep learning-based phase prediction of high-entropy alloys: Optimization, generation, and explanation. Mater. Des. 2021, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Yin, J.; Hawk, J.A.; Alman, D.E.; Gao, M.C. Machine-learning informed prediction of high-entropy solid solution formation: Beyond the Hume-Rothery rules. npj Comput. Mater. 2020, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liaw, P.K. Alloy Design and Properties Optimization of High-Entropy Alloys. JOM 2012, 64, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Cao, W.; Kattner, U. An understanding of high entropy alloys from phase diagram calculations. Calphad 2014, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, Y.; Toher, C.; Vecchio, K.S.; Curtarolo, S. The search for high entropy alloys: A high-throughput ab-initio approach. Acta Mater. 2018, 159, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickman, J.M.; Chan, H.M.; Harmer, M.P.; Smeltzer, J.A.; Marvel, C.J.; Roy, A.; Balasubramanian, G. Materials informatics for the screening of multi-principal elements and high-entropy alloys. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Schmidt, M.R.G. J. Schmidt, M.R.G. Marques, S. Botti, M.A.L. Marques, Recent advances and applications of machine learning in solid-state materials science. npj Computational Materials 2019, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Y.; He, Q.; Ding, Z.; Li, F.; Yang, Y. Machine learning guided appraisal and exploration of phase design for high entropy alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 2019, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaq, M.; Tariq, H.M.R.; Reddy, D.Y.C.; Kang, S.-G.; Reddy, N.G.S. Prediction of Creep Rupture Life of 5Cr-0.5Mo Steel Using Machine Learning Models. Metals 2025, 15, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-J.; Jui, C.-Y.; Lee, W.-J.; Yeh, A.-C. Prediction of the Composition and Hardness of High-Entropy Alloys by Machine Learning. JOM 2019, 71, 3433–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menou, E.; Tancret, F.; Toda-Caraballo, I.; Ramstein, G.; Castany, P.; Bertrand, E.; Gautier, N.; Díaz-Del-Castillo, P.E.J.R. Computational design of light and strong high entropy alloys (HEA): Obtainment of an extremely high specific solid solution hardening. Scr. Mater. 2018, 156, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Xue, D.; Bai, Y.; Antonov, S.; Dai, L.; Lookman, T.; Su, Y. Machine learning assisted design of high entropy alloys with desired property. Acta Mater. 2019, 170, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Wanderka, N.; Murty, B.; Glatzel, U.; Banhart, J. Decomposition in multi-component AlCoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, A.; Sigari, M.H.; Maghiar, M.; Citrin, D. An analogy between various machine-learning techniques for detecting construction materials in digital images. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pääkkönen, P.; Heikkinen, A.; Aihkisalo, T. Online architecture for predicting live video transcoding resources. J. Cloud Comput. 2019, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Bose, A. R. Bose, A. Das, J. Poray, S. Bhattacharya, Risk Analysis for Long-Term Stock Market Trend Prediction, in: M. Singh, P.K. Gupta, V. Tyagi, J. Flusser, T. Ören, R. Kashyap (Eds.) Advances in Computing and Data Sciences, Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2019, pp. 381-391.

- Mørup, M.; Hansen, L.K. Automatic relevance determination for multi-way models. Journal of Chemometrics: A Journal of the Chemometrics Society 2009, 23, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.J. Probable networks and plausible predictions—a review of practical Bayesian methods for supervised neural networks. Network: computation in neural systems 1995, 6, 469–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davronov, R.; Adilova, F. A comparative analysis of the ensemble methods for drug design. INTERNATIONAL UZBEKISTAN-MALAYSIA CONFERENCE ON “COMPUTATIONAL MODELS AND TECHNOLOGIES (CMT2020)”: CMT2020. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, UzbekistanDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 030001.

- XDang; Peng, H. ; Wang, X.; Zhang, H. Theil-sen estimators in a multiple linear regression model. Olemiss Edu 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Peck, E.A.; Vining, G.G. Introduction to linear regression analysis, John Wiley & Sons2012.

- Hassoun, M.H. Fundamentals of artificial neural networks, MIT press1995.

- Varacalle, D.J.; Wilson, G.C.; Johnson, R.W.; Steeper, T.J.; Irons, G.; Kratochvil, W.R.; Riggs, W. A taguchi experimental design study of twin-wire electric arc sprayed aluminum coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 1994, 3, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. Open Data for Sustainable Community: Glocalized Sustainable Development Goals, Springer2020.

- Tung, C.-C.; Yeh, J.-W.; Shun, T.-T.; Chen, S.-K.; Huang, Y.-S.; Chen, H.-C. On the elemental effect of AlCoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy system. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.-J.; Gan, J.-Y.; Chin, T.-S.; Shun, T.-T.; Tsau, C.-H.; Chang, S.-Y. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SKoppoju; Konduri, S. P.; Chalavadi, P.; Bonta, S.R.; Mantripragada, R. Effect of Ni on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of CrMnFeCoNi High Entropy Alloy. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals 2020, 73, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, F.; Cao, J.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, S. Strain rate effects on tensile deformation behaviors of Ti-10V-2Fe-3Al alloy undergoing stress-induced martensitic transformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 710, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-H.; Yeh, J.-W. High-entropy alloys: a critical review. Materials Research Letters 2014, 2, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Xue, W.; Fan, C.; Chen, R.; Wang, L.; Su, Y.; Ding, H.; Guo, J. Effect of Co content on phase formation and mechanical properties of (AlCoCrFeNi)100-Co high-entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 710, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Lim, K.R.; Won, J.W.; Na, Y.S. Effect of Co content on the mechanical properties of A2 and B2 phases in AlCoxCrFeNi high-entropy alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 2018, 769, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhou, K.; Jiang, L.; Lu, Y.; Lu, Y. Effects of Fe Content on Microstructures and Properties of AlCoCrFe x Ni High-Entropy Alloys. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2015, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.-J.; Chen, M.-R.; Yeh, J.-W.; Lin, S.-J.; Chen, S.-K.; Shun, T.-T.; Chang, S.-Y. Mechanical performance of the Al x CoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy system with multiprincipal elements. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2005, 36, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.-J.; Chen, Y.-L.; Yeh, J.-W.; Lin, S.-J.; Chen, S.-K.; Shun, T.-T.; Tsau, C.-H.; Chang, S.-Y. Microstructure characterization of Al x CoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy system with multiprincipal elements. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2005, 36, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Panigrahi, B.; Ho, C.M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, C.S. Artificial neural network modeling on the relative importance of alloying elements and heat treatment temperature to the stability of α and β phase in titanium alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2015, 107, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inputs | Al | 0 | 46.2 | 16.89 | 11.26 |

| Co | 0 | 42.9 | 14.56 | 10.23 | |

| Cr | 0 | 55.6 | 18.52 | 8.52 | |

| Cu | 0 | 29 | 10.65 | 9.2 | |

| Fe | 0 | 46.9 | 18.07 | 7.44 | |

| Ni | 0 | 50 | 21.31 | 9.2 | |

| Output | Hardness | 110 | 775 | 422.07 | 187.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).