Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

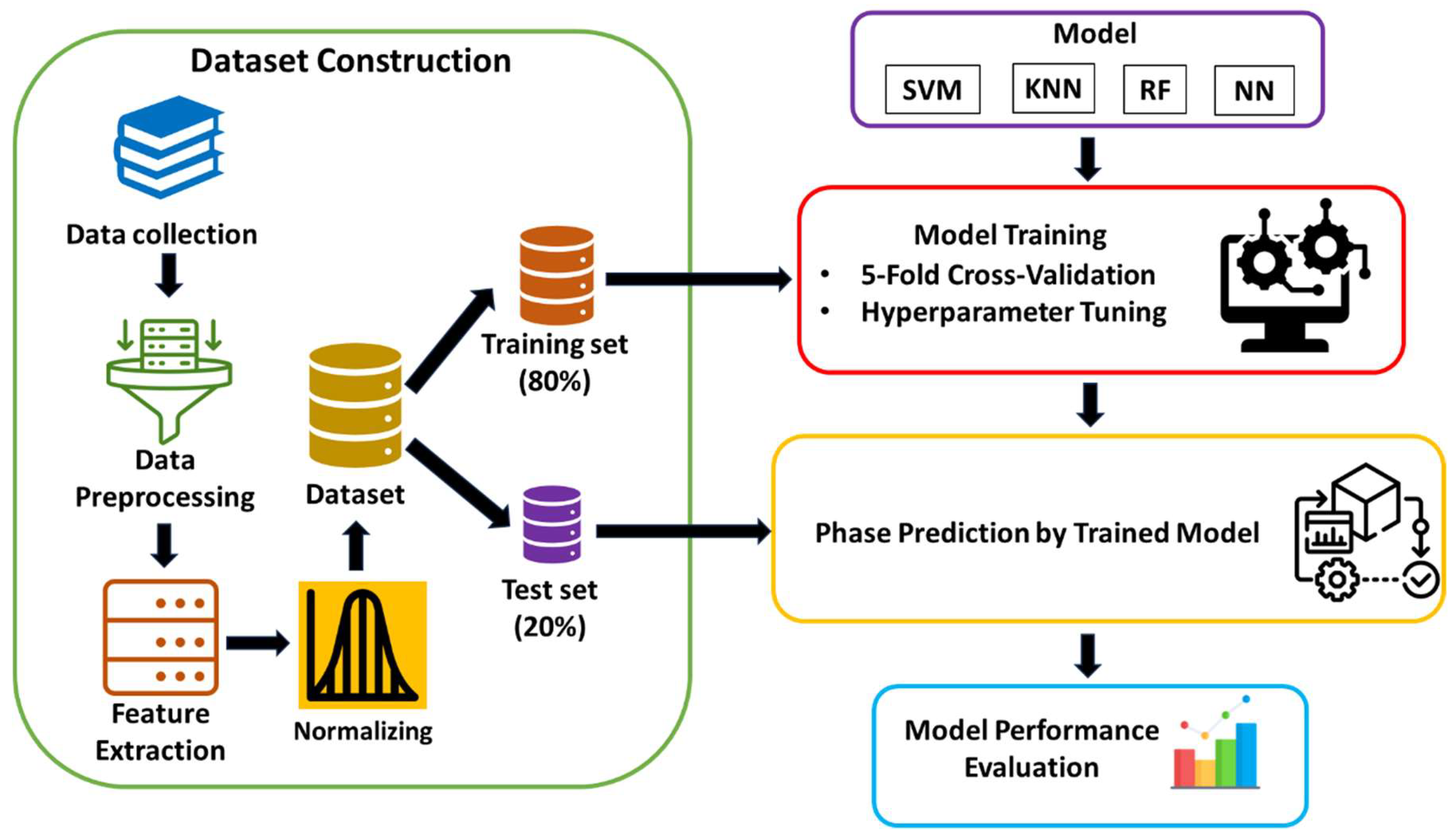

Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Construction

2.1.1. Data Collection and Feature Extraction

2.1.1. Data Normalization

2.2. ML Algorithms

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

- Random Forest (RF)

- Neural Network (NN)

2.3. Evaluation of Model Performance

3. Results and Discussion

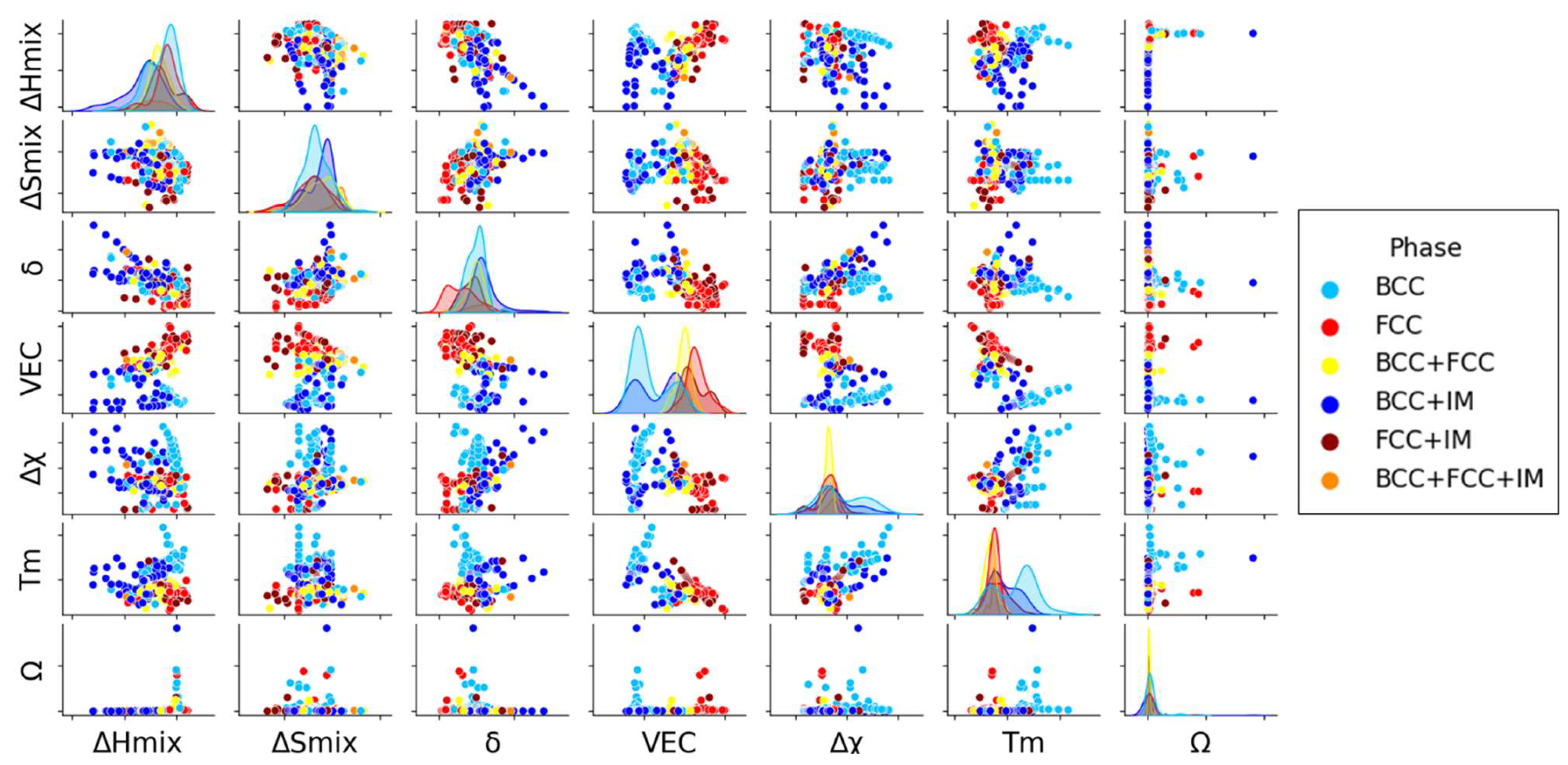

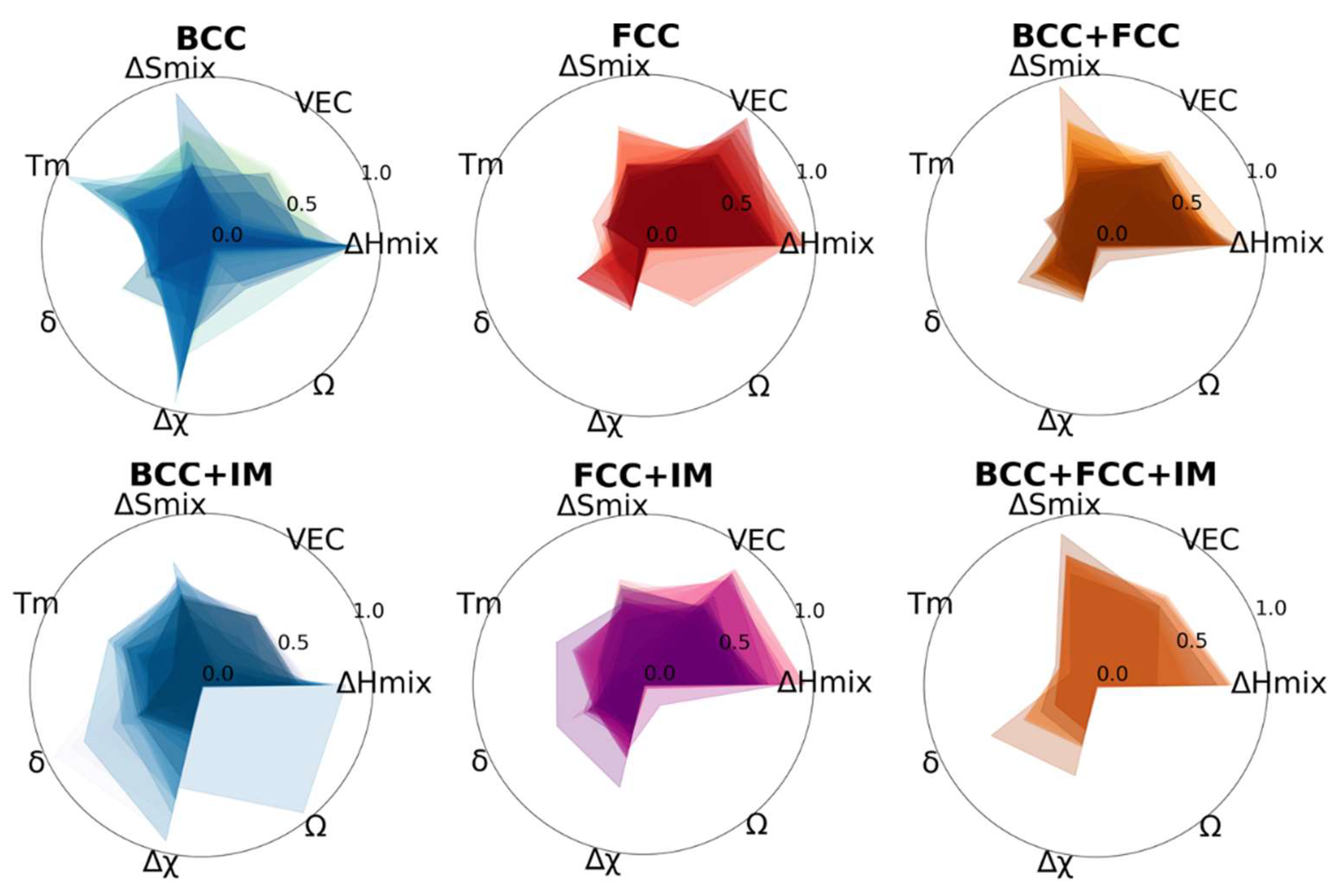

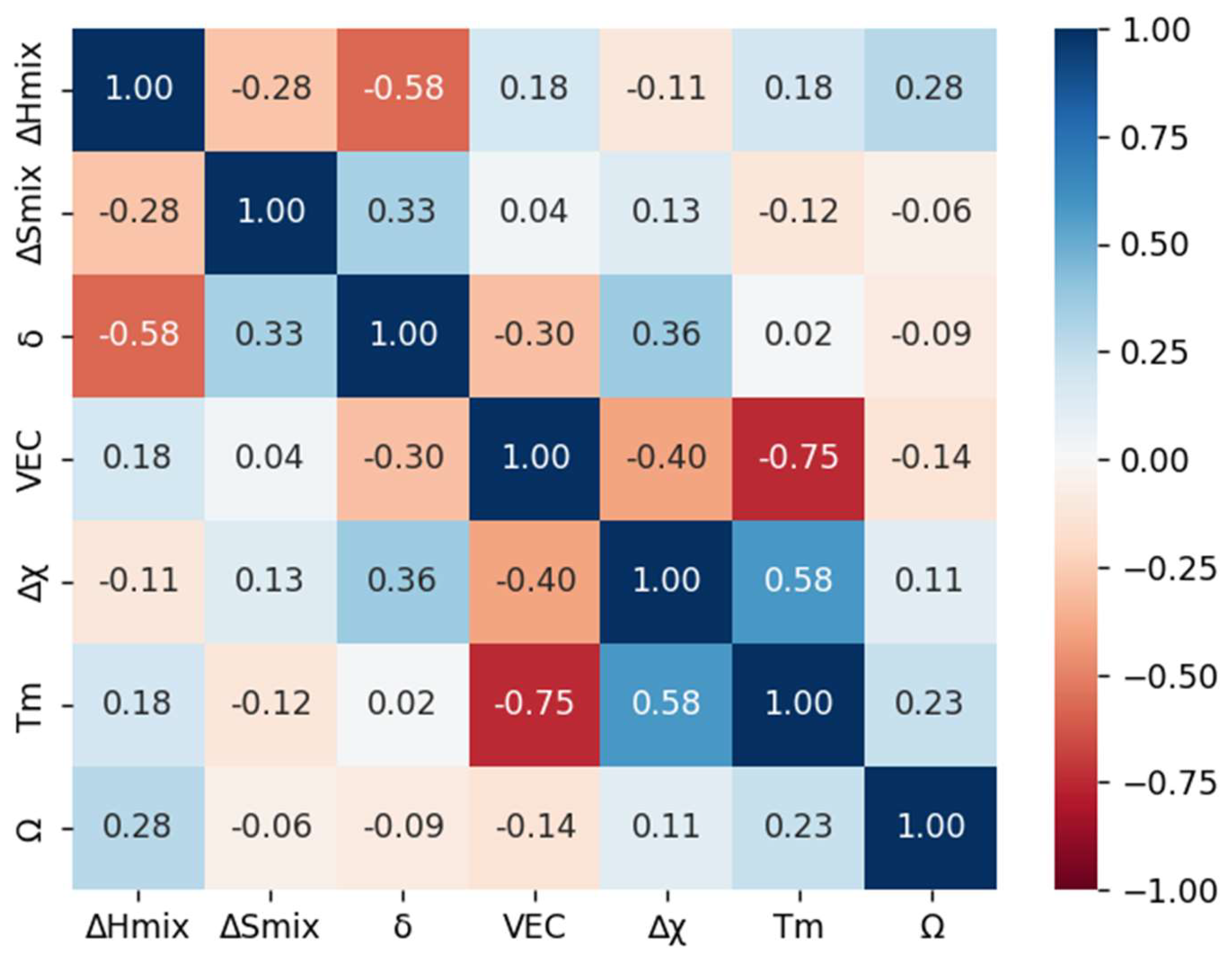

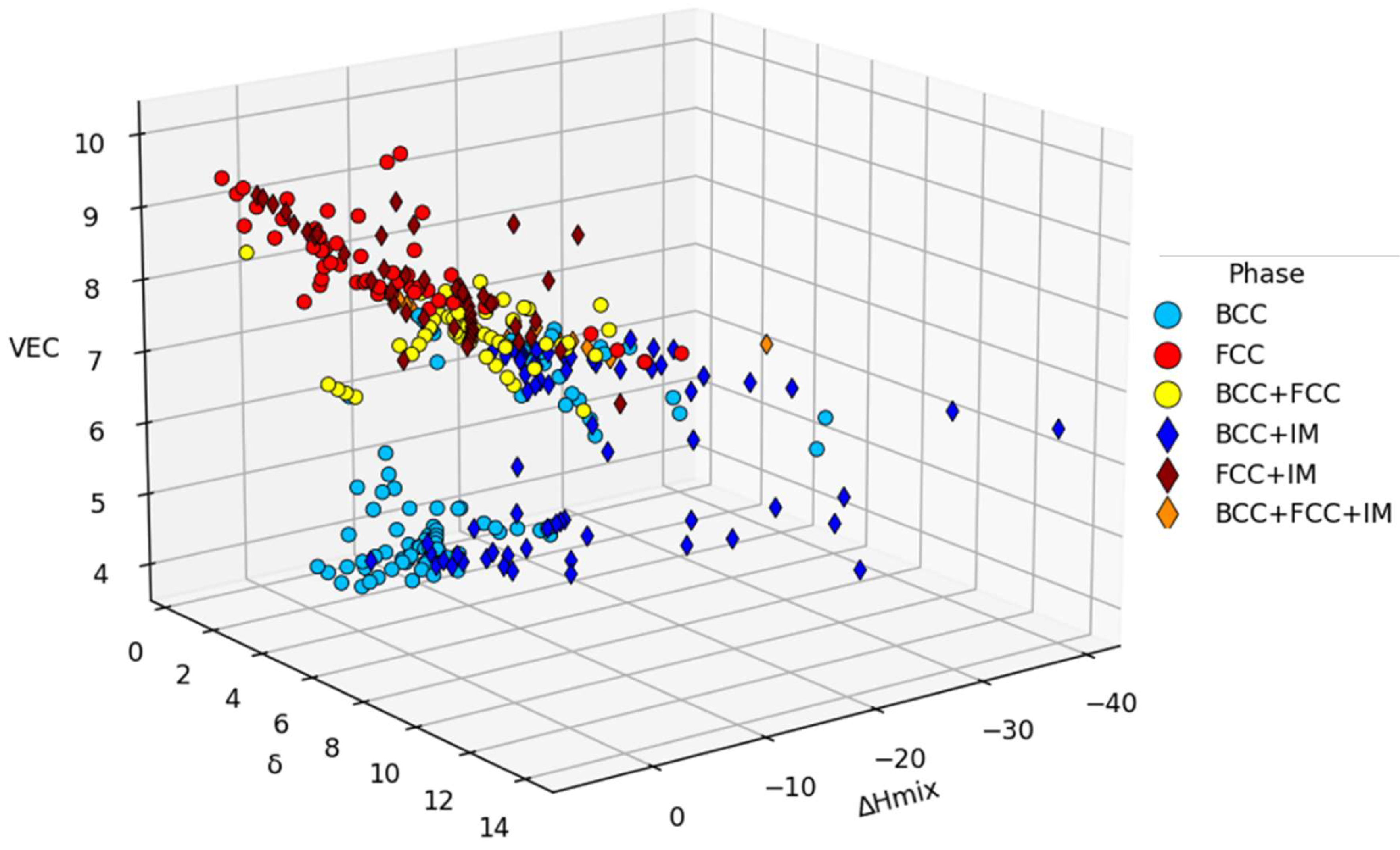

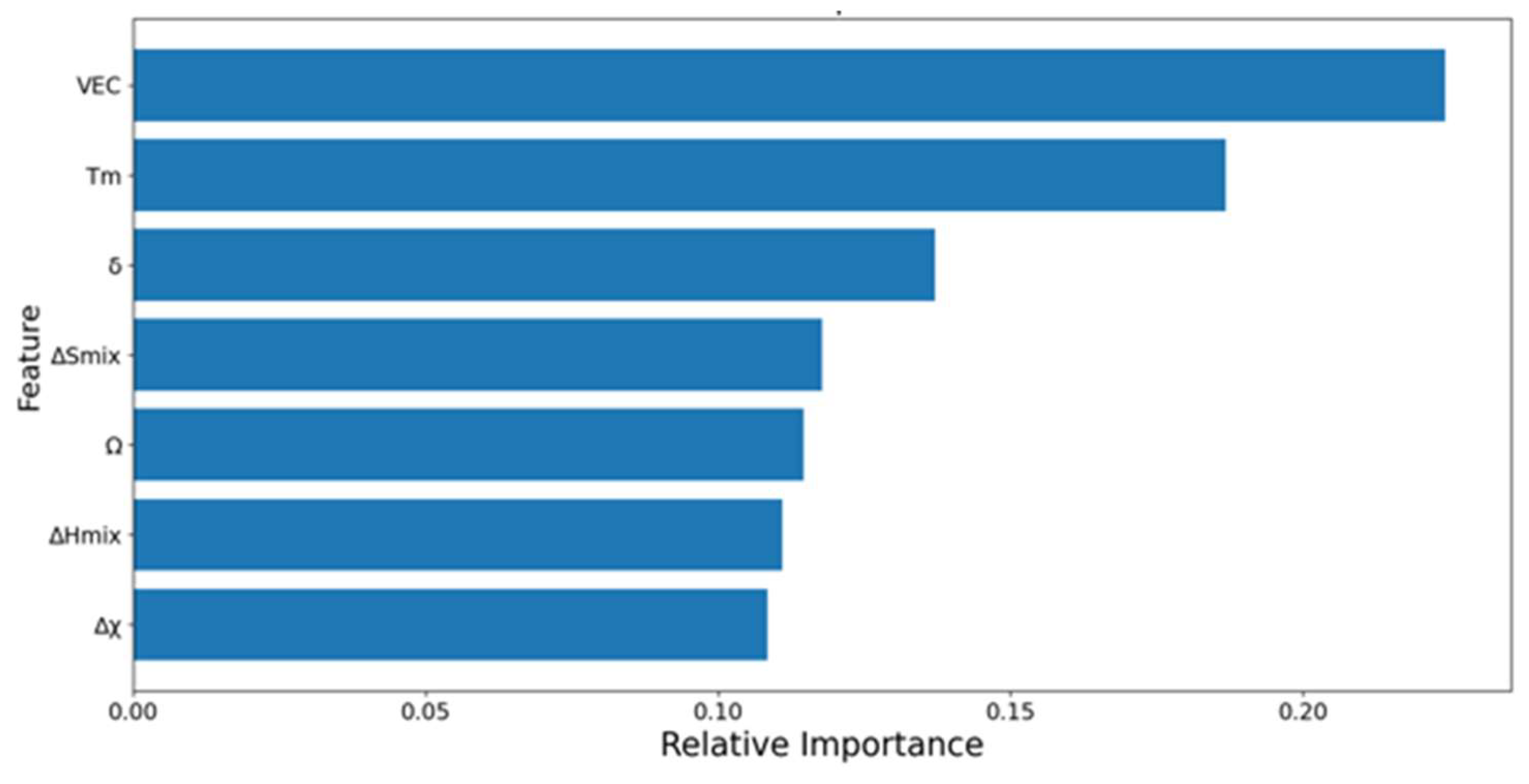

3.1. Data analysis

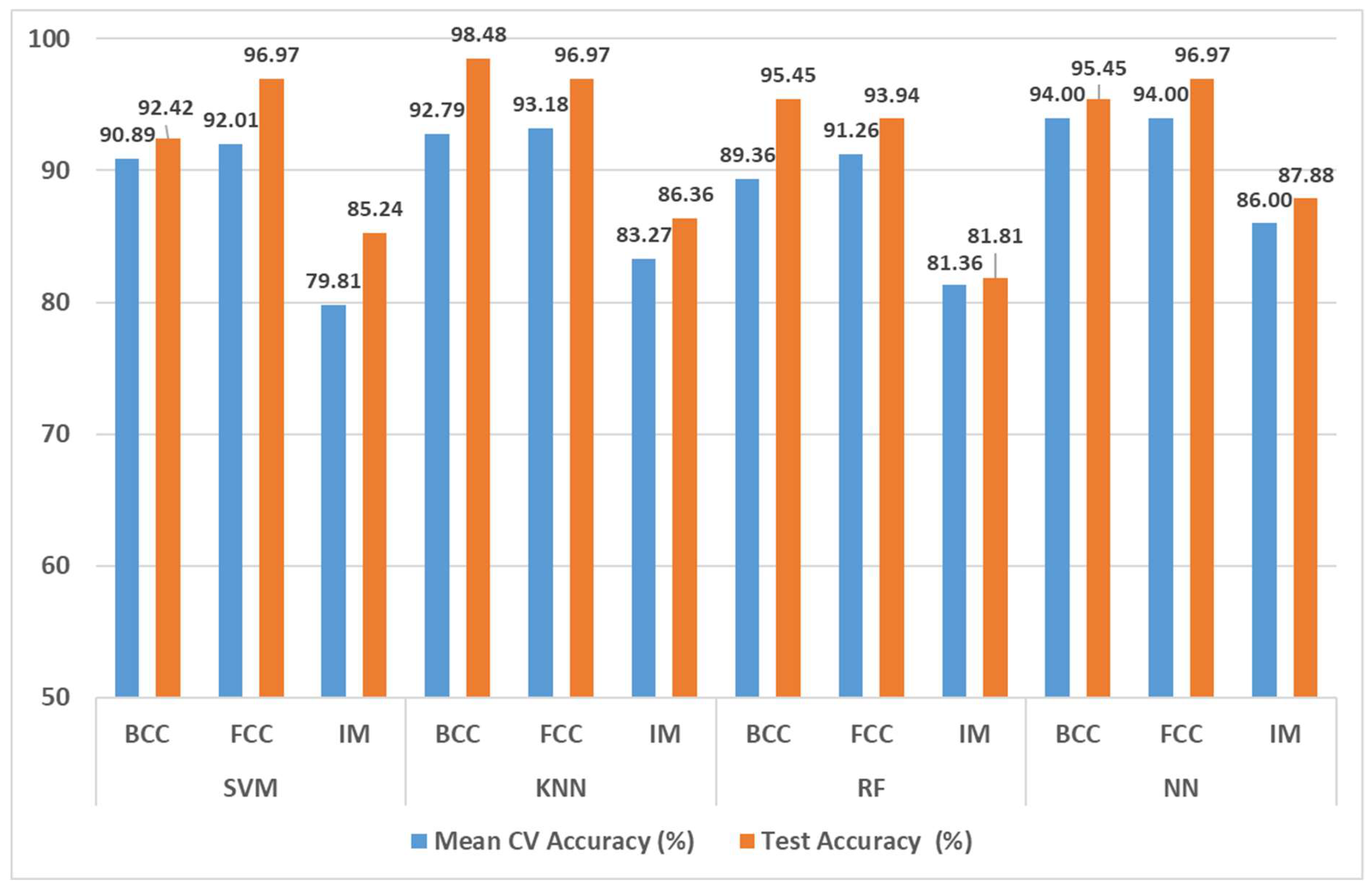

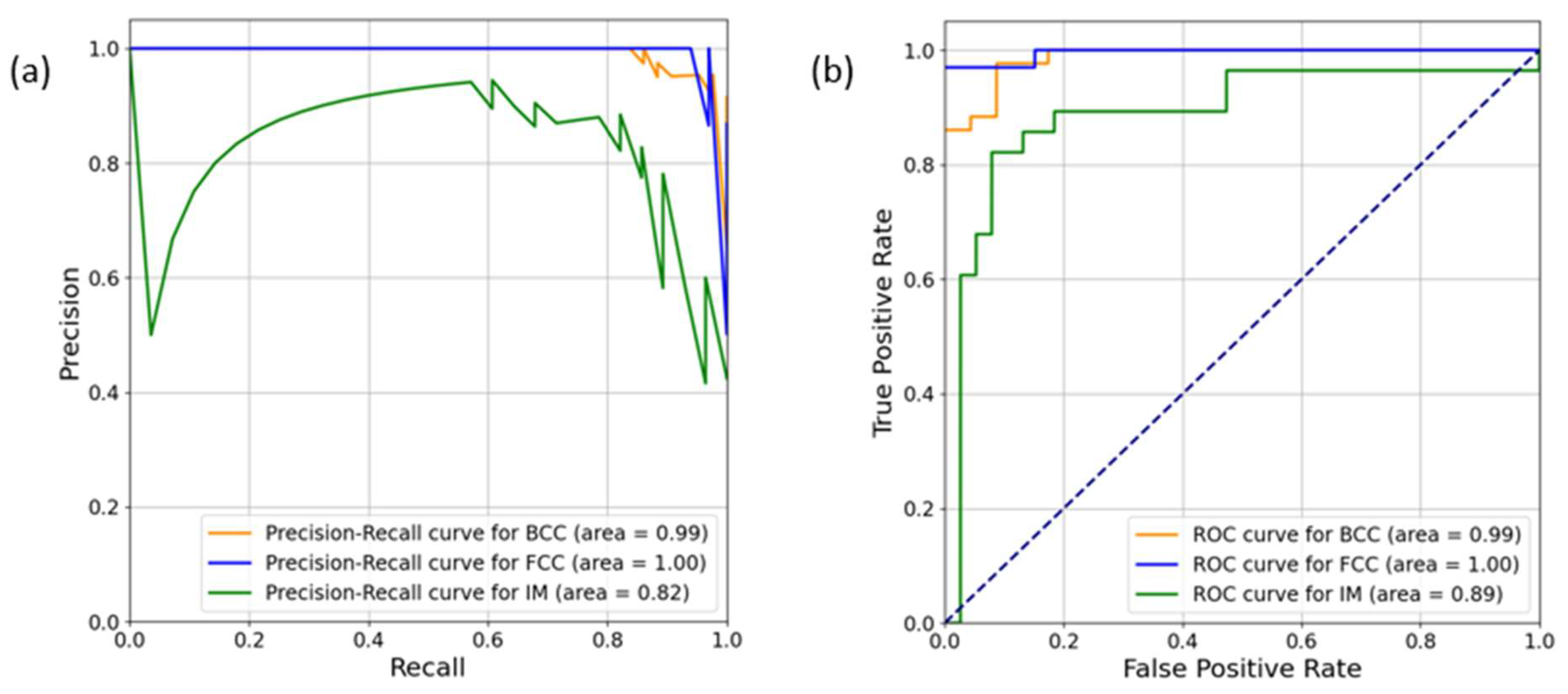

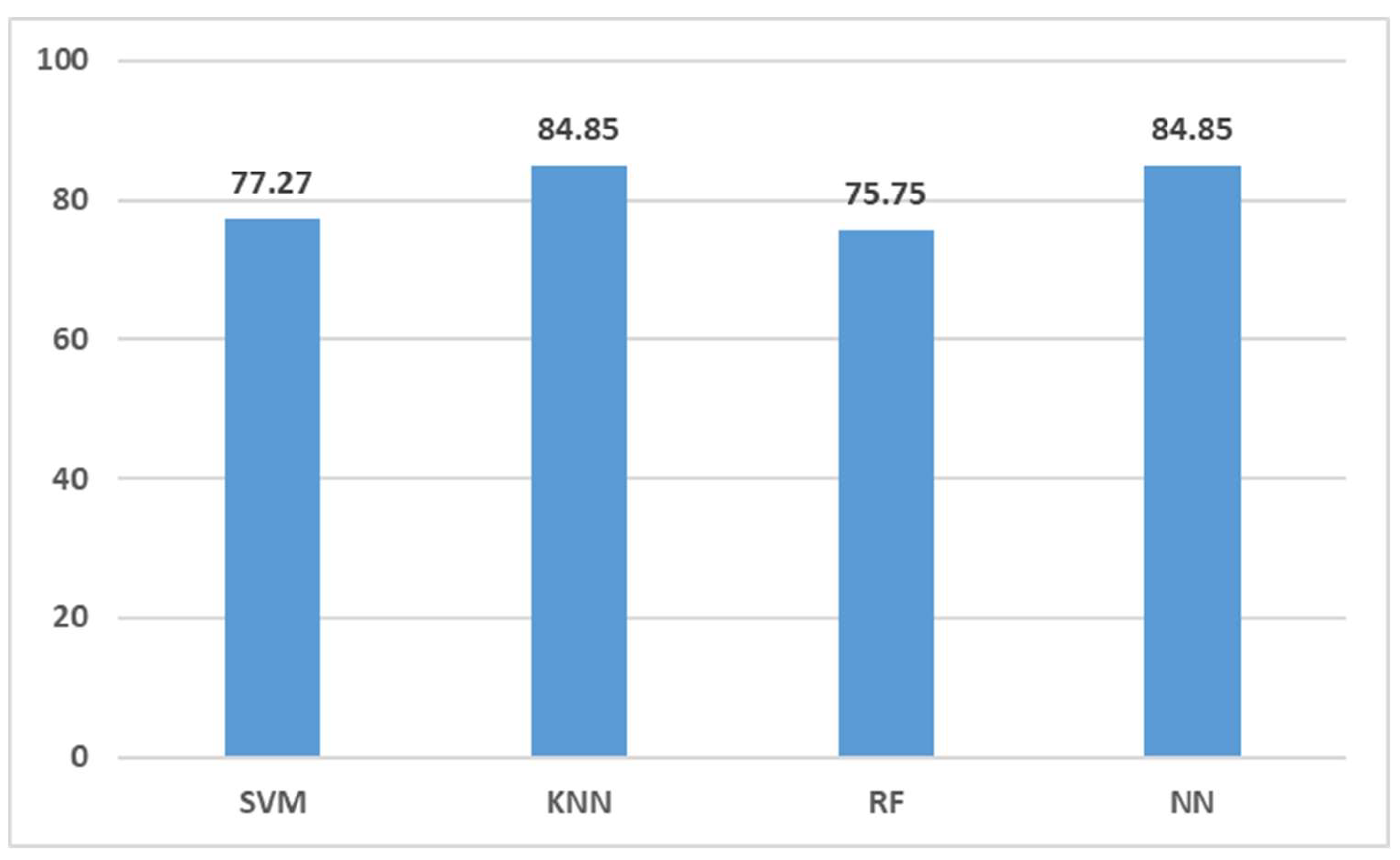

3.2. Model Performance for Phase Prediction

- 1.

-

SVM

- BCC Phases: The SVM achieves a mean CV accuracy of 90.89% and a test accuracy of 92.42%. Precision, recall and F1-score are all above 90%, with precision at 93.15 being the highest. This suggests that the SVM is highly reliable for correctly identifying BCC phases with only minor classifications.

- FCC Phases: The SVM performs exceptionally well for the FCC phases with test accuracy and all other metrics at 96.97%. This indicates that the SVM effectively classifies the FCC phase with near-perfect accuracy, likely due to clear distinguishing features in the dataset for this phase.

- IM Phases: For IM phases, the SVM shows a lower performance compared to for BCC and FCC phases, with a mean CV accuracy of 79.81% and a test accuracy of 85.24%. Precision and recall are both around 81-82% indicating moderate performance.

- 2.

-

KNN

- BCC Phases: The KNN shows excellent performance for BCC phases with a high mean CV accuracy of 92.79% and an impressive test accuracy of 98.48%. Both precision and recall are very high at 97.83% and 98.48%, respectively, indicating that the KNN is particularly effective in distinguish BCC phases.

- FCC Phases: The KNN’s performance for FCC phases is similarly strong, with a mean CV accuracy of 93.18%, a perfect test accuracy and other metrics at 96.97%. This suggests that the KNN can reliably identify FCC phases, similar to SVM.

- IM Phases: the KNN also performs well for IM phases with a mean CV accuracy of 83.27% and a test accuracy of 86.36%. The precision and F1-score are around 85-87%, indicating a balanced performance with a slight improvement over the SVM.

- 3.

-

RF

- BCC Phases: The RF achieves a mean CV accuracy of 89.36% and a strong test accuracy of 95.45% along with high precision (94.64%) and recall (96.50%). These metrics suggest that RF is highly effective in identifying BCC phases although it slightly lags behind the KNN in precision.

- FCC Phases: The RF performs well for FCC phases with a mean CV accuracy of 91.26% and a test accuracy of 93.94%. The precision, recall and F1-scores are all close to 94%, indicating a solid performance but slightly lower than the performance of the SVM and KNN. The RF is still reliable for FCC phases but the slightly lower metrics suggest that FCC features are well-learned but not perfectly.

- IM Phases: The RF’s performance for IM phases is moderate with a mean CV accuracy of 81.36% and a test accuracy of 81.81%. Precision and recall are around 80-83%, which are the lowest among the models. This lower performance for IM phases could indicate that RF struggles to differentiate IM from other phases, possibly due to the complex feature space of IM phases or insufficient training samples.

- 4.

-

NN

- BCC Phases: The NN has the highest mean CV accuracy for BCC phases at 94% and a high test accuracy of 95.45%. Precision, recall and F1-score are all above 94%, showing that the NN performs comparably to the KNN and RF for BCC phases. This suggests that the NN has a strong predictive capability for BCC phases and handles the features well.

- FCC Phases: The NN shows a strong performance for FCC phases with all metrics at 96.97%. This indicates that the NN is reliable and effective for FCC phase classification, similar to the SVM and KNN.

- IM Phases: The NN achieves the highest mean CV accuracy and test accuracy for IM phases at 86% and 87.88% respectively. Precision and F1-scores are also high at around 87-88%, indicating that the NN is the most effective model for distinguishing IM phases among the four.

3.3. Complex Combination Phase Prediction Results

4. Conclusion

References

- Yeh, J. -W.; Chen, S. -K.; Lin, S. -J.; Gan, J. -Y.; Chin, T. -S.; Shun, T. -T.; Tsau, C. -H.; Chang, S. -Y. Nanostructured High-Entropy Alloys with Multiple Principal Elements: Novel Alloy Design Concepts and Outcomes. Adv Eng Mater 2004, 6, 299–303, doi:10.1002/adem.200300567. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Qiao, J. High-Entropy Alloys (HEAs). Metals 2018, 8, 108, doi:10.3390/met8020108. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, B.; Liaw, P. Corrosion-Resistant High-Entropy Alloys: A Review. Metals 2017, 7, 43, doi:10.3390/met7020043. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, D.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Corrosion Behavior of High Entropy Alloys and Their Application in the Nuclear Industry—An Overview. Metals 2023, 13, 363, doi:10.3390/met13020363. [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Hou, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Cao, Z. The Microstructures and Wear Resistance of CoCrFeNi2Mox High-Entropy Alloy Coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 760, doi:10.3390/coatings14060760. [CrossRef]

- Firstov, S.A.; Gorban’, V.F.; Krapivka, N.A.; Karpets, M.V.; Kostenko, A.D. Wear Resistance of High-Entropy Alloys. Powder Metall Met Ceram 2017, 56, 158–164, doi:10.1007/s11106-017-9882-8. [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, M.A.; Yuan, T.; Wang, G.Y.; Yeh, J.W.; Tsai, C.W.; Chuang, A.; Liaw, P.K. Fatigue Behavior of Al0.5CoCrCuFeNi High Entropy Alloys. Acta Materialia 2012, 60, 5723–5734, doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2012.06.046. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Chen, R.; Liu, T.; Fang, H.; Qin, G.; Su, Y.; Guo, J. High-Entropy Alloys: A Review of Mechanical Properties and Deformation Mechanisms at Cryogenic Temperatures. J Mater Sci 2022, 57, 6573–6606, doi:10.1007/s10853-022-07066-2. [CrossRef]

- Ujah, C.O.; Von Kallon, D.V. Characteristics of Phases and Processing Techniques of High Entropy Alloys. International Journal of Lightweight Materials and Manufacture 2024, 7, 809–824, doi:10.1016/j.ijlmm.2024.07.002. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y. Prediction of High-Entropy Stabilized Solid-Solution in Multi-Component Alloys. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2012, 132, 233–238, doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2011.11.021. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Hu, Q.; Ng, C.; Liu, C.T. More than Entropy in High-Entropy Alloys: Forming Solid Solutions or Amorphous Phase. Intermetallics 2013, 41, 96–103, doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2013.05.002. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Ng, C.; Lu, J.; Liu, C.T. Effect of Valence Electron Concentration on Stability of Fcc or Bcc Phase in High Entropy Alloys. Journal of Applied Physics 2011, 109, 103505, doi:10.1063/1.3587228. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yen, S.; Chu, S.; Lin, S.; Tsai, M.-H. Mechanical and Thermodynamic Data-Driven Design of Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Ni Multi-Principal Element Alloys. Materials Today Communications 2021, 26, 102096, doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102096. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Smirnov, A.V.; Alam, A.; Johnson, D.D. First-Principles Prediction of Incipient Order in Arbitrary High-Entropy Alloys: Exemplified in Ti0.25CrFeNiAl. Acta Materialia 2020, 189, 248–254, doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2020.02.063. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.C.; Zhang, C.; Gao, P.; Zhang, F.; Ouyang, L.Z.; Widom, M.; Hawk, J.A. Thermodynamics of Concentrated Solid Solution Alloys. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science 2017, 21, 238–251, doi:10.1016/j.cossms.2017.08.001. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Uberuaga, B.P. Efficient Ab Initio Modeling of Random Multicomponent Alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 105501, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.105501. [CrossRef]

- Mulewicz, B.; Korpala, G.; Kusiak, J.; Prahl, U. Autonomous Interpretation of the Microstructure of Steels and Special Alloys. MSF 2019, 949, 24–31, doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.949.24. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Babuska, T.; Krick, B.; Balasubramanian, G. Machine Learned Feature Identification for Predicting Phase and Young’s Modulus of Low-, Medium- and High-Entropy Alloys. Scripta Materialia 2020, 185, 152–158, doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2020.04.016. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Xue, W.; Xiang, S.; Huang, H.; Meng, L.; Ma, G.; Ullah, A.; Zhang, G. Study on Time-Temperature-Transformation Diagrams of Stainless Steel Using Machine-Learning Approach. Computational Materials Science 2020, 171, 109282, doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2019.109282. [CrossRef]

- Elkatatny, S.; Abd-Elaziem, W.; Sebaey, T.A.; Darwish, M.A.; Hamada, A. Machine-Learning Synergy in High-Entropy Alloys: A Review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 33, 3976–3997, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.10.034. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J. A Focused Review on Machine Learning Aided High-Throughput Methods in High Entropy Alloy. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2021, 877, 160295, doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160295. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Xie, L.; Wang, L. Current Application Status of Multi-Scale Simulation and Machine Learning in Research on High-Entropy Alloys. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 26, 1341–1374, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.07.233. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Huang, W.; Zhuang, H.L. Machine Learning for Phase Selection in Multi-Principal Element Alloys. Computational Materials Science 2018, 150, 230–235, doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2018.04.003. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Martin, P.; Zhuang, H.L. Machine-Learning Phase Prediction of High-Entropy Alloys. Acta Materialia 2019, 169, 225–236, doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2019.03.012. [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Xu, T.; Wei, X.; Ding, G.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. Using Machine Learning and Feature Engineering to Characterize Limited Material Datasets of High-Entropy Alloys. Computational Materials Science 2020, 175, 109618, doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.109618. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Tao, X.; Cai, H.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Du, Y. Machine Learning Reveals the Importance of the Formation Enthalpy and Atom-Size Difference in Forming Phases of High Entropy Alloys. Materials & Design 2020, 193, 108835, doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2020.108835. [CrossRef]

- Machaka, R. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Phases in High-Entropy Alloys. Computational Materials Science 2021, 188, 110244, doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.110244. [CrossRef]

- Syarif, J.; Elbeltagy, M.B.; Nassif, A.B. A Machine Learning Framework for Discovering High Entropy Alloys Phase Formation Drivers. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12859, doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e12859. [CrossRef]

- Ghouchan Nezhad Noor Nia, R.; Jalali, M.; Houshmand, M. A Graph-Based k-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) Approach for Predicting Phases in High-Entropy Alloys. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 8021, doi:10.3390/app12168021. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Hou, J.; You, J.; Qiu, K.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Phase Prediction and Visualized Design Process of High Entropy Alloys via Machine Learned Methodology. Metals 2023, 13, 283, doi:10.3390/met13020283. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, H.; Ge, M.; Si, T.; Che, L.; Zheng, K.; Zeng, L.; Wang, Q. Machine Learning Guided BCC or FCC Phase Prediction in High Entropy Alloys. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 29, 3477–3486, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.01.257. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Ju, W.; Shi, S. Materials Discovery and Design Using Machine Learning. Journal of Materiomics 2017, 3, 159–177, doi:10.1016/j.jmat.2017.08.002. [CrossRef]

- Gorsse, S.; Nguyen, M.H.; Senkov, O.N.; Miracle, D.B. Database on the Mechanical Properties of High Entropy Alloys and Complex Concentrated Alloys. Data in Brief 2018, 21, 2664–2678, doi:10.1016/j.dib.2018.11.111. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Lin, Z.; Xu, H.; Sun, Y. Studies on the Microstructure and Properties of AlxCoCrFeNiTi1-x High Entropy Alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2018, 741, 826–833, doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.01.247. [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Ye, F.; Yang, C.; Wu, S. Effect of Alloying Elements on Microstructure, Mechanical and Damping Properties of Cr-Mn-Fe-V-Cu High-Entropy Alloys. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2018, 34, 2014–2021, doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2018.02.026. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Z.; Guo, N.; Ding, J.; Feng, L.; Zhu, G.; Yin, F. Phase Formation Mechanism of Triple-Phase Eutectic AlCrFe2Ni2(MoNb)x (x = 0.2, 0.5) High-Entropy Alloys. Materials Characterization 2024, 217, 114449, doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2024.114449. [CrossRef]

- Olorundaisi, E.; Babalola, B.J.; Anamu, U.S.; Teffo, M.L.; Kibambe, N.M.; Ogunmefun, A.O.; Odetola, P.; Olubambi, P.A. Thermo-Mechanical and Phase Prediction of Ni25Al25Co14Fe14Ti9Mn8Cr5 High Entropy Alloys System Using THERMO-CALC. Manufacturing Letters 2024, 41, 160–169, doi:10.1016/j.mfglet.2024.09.020. [CrossRef]

- Tirunilai, A.S.; Somsen, C.; Laplanche, G. Excellent Strength-Ductility Combination in the Absence of Twinning in a Novel Single-Phase VMnFeCoNi High-Entropy Alloy. Scripta Materialia 2025, 256, 116430, doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2024.116430. [CrossRef]

- Záděra, A.; Sopoušek, J.; Buršík, J.; Čupera, J.; Brož, P.; Jan, V. Influence of Substitution of Cr by Cu on Phase Equilibria and Microstructures in the Fe–Ni–Co–Cr High-Entropy Alloys. Intermetallics 2024, 174, 108455, doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2024.108455. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Chen, D.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Fang, H.; Chen, R. Enhancing Mechanical Performance of Ti2ZrNbHfVAl Refractory High-Entropy Alloys through Laves Phase. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2024, 918, 147438, doi:10.1016/j.msea.2024.147438. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Lu, W.; Li, Y.; Liang, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. A Single-Phase Nb25Ti35V5Zr35 Refractory High-Entropy Alloy with Excellent Strength-Ductility Synergy. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2024, 1006, 176290, doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.176290. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Liu, B.; Han, X.; Zhang, C.; Wilde, G.; Ye, F. Effect of Al–Zr and Si–Zr Atomic Pairs on Phases, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Si-Alloyed (Ti28Zr40Al20Nb12)100-Si (=1, 3, 5, 10) High Entropy Alloys. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 32, 2563–2577, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.08.128. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Li, X.; Dilixiati, N. Phase Evolution, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Resistance of Ti2NbVAl0.3Zrx Lightweight Refractory High-Entropy Alloys. Intermetallics 2024, 173, 108433, doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2024.108433. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Ozasa, R.; Sato, K.; Gokcekaya, O.; Nakano, T. Design and Development of a Novel Non-Equiatomic Ti-Nb-Mo-Ta-W Refractory High Entropy Alloy with a Single-Phase Body-Centered Cubic Structure. Scripta Materialia 2024, 252, 116260, doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2024.116260. [CrossRef]

- Saboktakin Rizi, M.; Ebrahimian, M.; Minouei, H.; Shim, S.H.; Pouraliakbar, H.; Fallah, V.; Park, N.; Hong, S.I. Enhancing Mechanical Properties in Ti-Containing FeMn40Co10Cr10C0.5 High-Entropy Alloy through Chi (χ) Phase Dissolution and Precipitation Hardening. Materials Letters 2024, 377, 137516, doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2024.137516. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, S.; Xu, H.; Liu, C.; An, X.; Chu, Z.; Wei, W.; Wang, D.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; et al. A Novel Cast Co68Al18.2Fe6.5V4.75Cr2.55 Dual-Phase Medium Entropy Alloy with Superior High-Temperature Performance. Intermetallics 2024, 169, 108301, doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2024.108301. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, S.; Chu, C.; Huang, L.; Duan, J.; Tian, Z.; Fu, Z. Exceptional Combinations of Tensile Properties and Corrosion Resistance in a Single-Phase Ti1.6ZrNbMo0.35 Refractory High-Entropy Alloy. Intermetallics 2024, 171, 108349, doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2024.108349. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; George, E.P.; Laplanche, G. Effects of Grain Size and Stacking Fault Energy on Twinning Stresses of Single-Phase Cr Mn20Fe20Co20Ni40- High-Entropy Alloys. Acta Materialia 2025, 282, 120470, doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2024.120470. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, M.; Xing, C.; He, Y. Tailoring Phase Transformation and Precipitation Features in a Al21Co19.5Fe9.5Ni50 Eutectic High-Entropy Alloy to Achieve Different Strength-Ductility Combinations. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2024, 195, 111–125, doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2024.01.044. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, G.; Ding, X.; Li, Y.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, T.; Qu, Y. The Synergistic Effect of Ni and C14 Laves Phase on the Hydrogen Storage Properties of TiVZrNbNi High Entropy Hydrogen Storage Alloy. Intermetallics 2024, 164, 108102, doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2023.108102. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z.; Cao, F. Effects of Sc Addition on Microstructure, Phase Evolution and Mechanical Properties of Al0.2CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2023, 33, 3756–3769, doi:10.1016/S1003-6326(23)66368-X. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wang, W.; Qi, X.; Lv, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, T.; Chen, J. Effects of Heat Treatment Cooling Methods on Precipitated Phase and Mechanical Properties of CoCrFeMnNi–Mo5C0.5 High Entropy Alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 29, 3566–3574, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.02.076. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xing, W.; Liu, C.; Yang, K.; Shao, H.; Zhao, H. Construction of Multiscale Secondary Phase in Al0.25FeCoNiV High-Entropy Alloy and in-Situ EBSD Investigation. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 30, 7607–7620, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.05.168. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Luo, H.; Yang, Z.; Pan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Islamgaliev, R.K.; Li, X. Hydrogen Induced Cracking Behavior of the Dual-Phase Co30Cr10Fe10Al18Ni30Mo2 Eutectic High Entropy Alloy. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 134–147, doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.09.053. [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, A.; Khani Moghanaki, S.; Amirjan, M. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of a Dual Phase Al14Co41Cr15Fe10Ni20 High Entropy Alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 26, 2419–2431, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.08.071. [CrossRef]

- Vaghari, M.; Dehghani, K. Computational and Experimental Investigation of a New Non Equiatomic FCC Single-Phase Cr15Cu5Fe20Mn25Ni35 High-Entropy Alloy. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2023, 671, 415413, doi:10.1016/j.physb.2023.415413. [CrossRef]

- Tamuly, S.; Dixit, S.; Kombaiah, B.; Parameswaran, V.; Khanikar, P. High Strain Rate Deformation Behavior of Al0.65CoCrFe2Ni Dual-Phase High Entropy Alloy. Intermetallics 2023, 161, 107983, doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2023.107983. [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Wang, J.; Li, H. Ultrahigh Strength and Ductility Combination in Al40Cr15Fe15Co15Ni15 Triple-Phase High Entropy Alloy. Intermetallics 2024, 164, 108118, doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2023.108118. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, G.; Han, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Cao, X. Dynamic Recrystallization Behavior of Single-Phase BCC Structure AlFeCoNiMo0.2 High-Entropy Alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 23, 4376–4384, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.02.074. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Chu, C.; Fu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, X.; Lavernia, E.J. Microstructural Evolution and Mechanical Behavior of Novel Ti1.6ZrNbAl Lightweight Refractory High-Entropy Alloys Containing BCC/B2 Phases. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2023, 885, 145661, doi:10.1016/j.msea.2023.145661. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Gao, X.; Cui, H.; Song, Q.; Chen, R. Lightweight and High Hardness (AlNbTiVCr)100-Ni High Entropy Alloys Reinforced by Laves Phase. Vacuum 2023, 213, 112115, doi:10.1016/j.vacuum.2023.112115. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, X.; Niu, Y.; Yang, R.; Chen, W.; Yusupu, B.; Jia, L. A Dual-Phase CrFeNbTiMo Refractory High Entropy Alloy with Excellent Hardness and Strength. Materials Letters 2023, 337, 133958, doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2023.133958. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liao, H.; Chen, H.; Feng, D.; Zhu, W. Realizing Strength-Ductility Combination of Fe3.5Ni3.5Cr2MnAl0.7 High-Entropy Alloy via Coherent Dual-Phase Structure. Vacuum 2023, 215, 112297, doi:10.1016/j.vacuum.2023.112297. [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Chen, R.R.; Gao, X.F.; Liu, T.; Qin, G.; Wu, S.P.; Guo, J.J. Development of Wear-Resistant Dual-Phase High-Entropy Alloys Enhanced by C15 Laves Phase. Materials Characterization 2023, 200, 112879, doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2023.112879. [CrossRef]

- Shuo Wang; Xin Yao Multiclass Imbalance Problems: Analysis and Potential Solutions. IEEE Trans. Syst., Man, Cybern. B 2012, 42, 1119–1130, doi:10.1109/TSMCB.2012.2187280. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Lin, J.P.; Chen, G.L.; Liaw, P.K. Solid-Solution Phase Formation Rules for Multi-component Alloys. Adv Eng Mater 2008, 10, 534–538, doi:10.1002/adem.200700240. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, C.; Wang, C.; Antonov, S.; Xue, D.; Bai, Y.; Su, Y. Phase Prediction in High Entropy Alloys with a Rational Selection of Materials Descriptors and Machine Learning Models. Acta Materialia 2020, 185, 528–539, doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2019.11.067. [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J.H. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Springer series in statistics; 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-84857-0.

- Zhang, W.; Li, P.; Wang, L.; Wan, F.; Wu, J.; Yong, L. Explaining of Prediction Accuracy on Phase Selection of Amorphous Alloys and High Entropy Alloys Using Support Vector Machines in Machine Learning. Materials Today Communications 2023, 35, 105694, doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.105694. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Introduction to Machine Learning: K-Nearest Neighbors. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 218–218, doi:10.21037/atm.2016.03.37. [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, S.K.; Nagarjuna, C.; Jain, R.; Kumawat, R.L.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, A.; Ahn, B. Review on Applications of Artificial Neural Networks to Develop High Entropy Alloys: A State-of-the-Art Technique. Materials Today Communications 2023, 37, 107298, doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107298. [CrossRef]

- Arlot, S.; Celisse, A. A Survey of Cross-Validation Procedures for Model Selection. Statist. Surv. 2010, 4, doi:10.1214/09-SS054. [CrossRef]

- Armah, G.K.; Luo, G.; Qin, K. A Deep Analysis of the Precision Formula for Imbalanced Class Distribution. IJMLC 2014, 4, 417–422, doi:10.7763/IJMLC.2014.V4.447. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and Properties of High-Entropy Alloys. Progress in Materials Science 2014, 61, 1–93, doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2013.10.001. [CrossRef]

| Alloys | Phase | BCC | FCC | IM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HfMoNbTaTiZr | BCC | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| CoCrFeMnNiV0.5 | FCC | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| CoCrFeMnNiV0.75 | FCC+IM | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| AlCrCuFeNi0.8 | BCC+FCC | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| AlCoCuFeNiZr | BCC+FCC+IM | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Equation | Feature description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Mixing entropy | [66] | |

| Mixing enthalpy | [26] | |

| Melting temperature | [10] | |

| Parameter for predicting solid solution formation | [10] | |

| Atom size difference | [66] | |

| Valence electron concentration | [12] | |

| Electronegativity difference | [67] |

| Model | Hyperparameter | Range of hyperparameter |

|---|---|---|

| SVM | C kernel gamma |

[1,10, 50, 100] rbf, poly, sigmoid [1, 10, 100] |

| KNN | N_neighbors weights P Algorithm |

range (1, 50) uniform, distance manhattan, Euclidean auto, ball_free, kd_tree, brute |

| RF | n_estimators max_depth min_samples_split min_samples_leaf |

[50, 100, 200] [None, 5, 10, 20] [2, 5, 10] [1, 2, 4] |

| NN | hidden_layer_sizes activation solver alpha |

[50, 100, 200] logistic, tanh, relu lbfgs, sgd, adam [0.0001, 0.001, 0.01] |

| Performance metric | SVM | KNN | RF | NN | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCC | FCC | IM | BCC | FCC | IM | BCC | FCC | IM | BCC | FCC | IM | |

| Mean CV Accuracy (%) | 90.89 | 92.01 | 79.81 | 92.79 | 93.18 | 83.27 | 89.36 | 91.26 | 81.36 | 94.00 | 94.00 | 86.00 |

| Test Accuracy (%) | 92.42 | 96.97 | 85.24 | 98.48 | 96.97 | 86.36 | 95.45 | 93.94 | 81.81 | 95.45 | 96.97 | 87.88 |

| Precision (%) | 93.15 | 96.97 | 81.30 | 97.83 | 96.97 | 86.68 | 94.64 | 94.10 | 82.95 | 95.45 | 96.97 | 87.98 |

| Recall (%) | 90.14 | 96.97 | 82.15 | 98.48 | 96.97 | 85.34 | 95.50 | 93.94 | 79.98 | 94.49 | 96.97 | 87.12 |

| F1 score (%) | 91.38 | 96.97 | 82.15 | 98.48 | 96.97 | 85.81 | 95.04 | 93.93 | 81.39 | 94.94 | 96.97 | 87.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).