Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

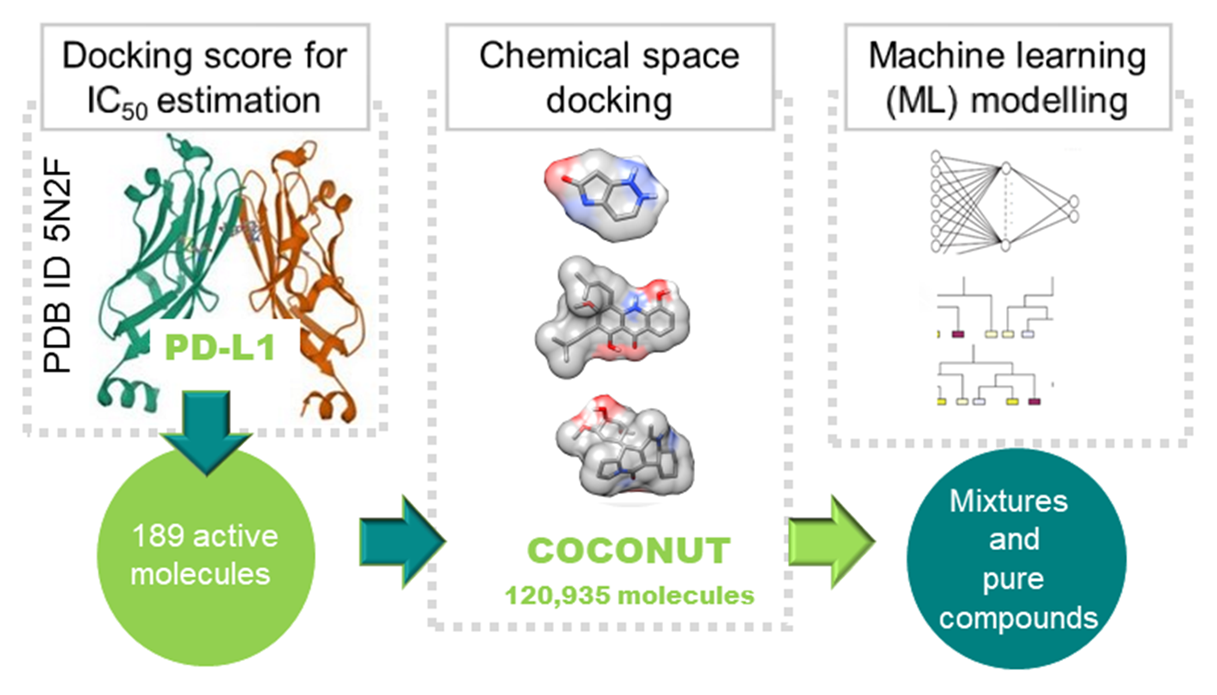

2. Results and Discussion

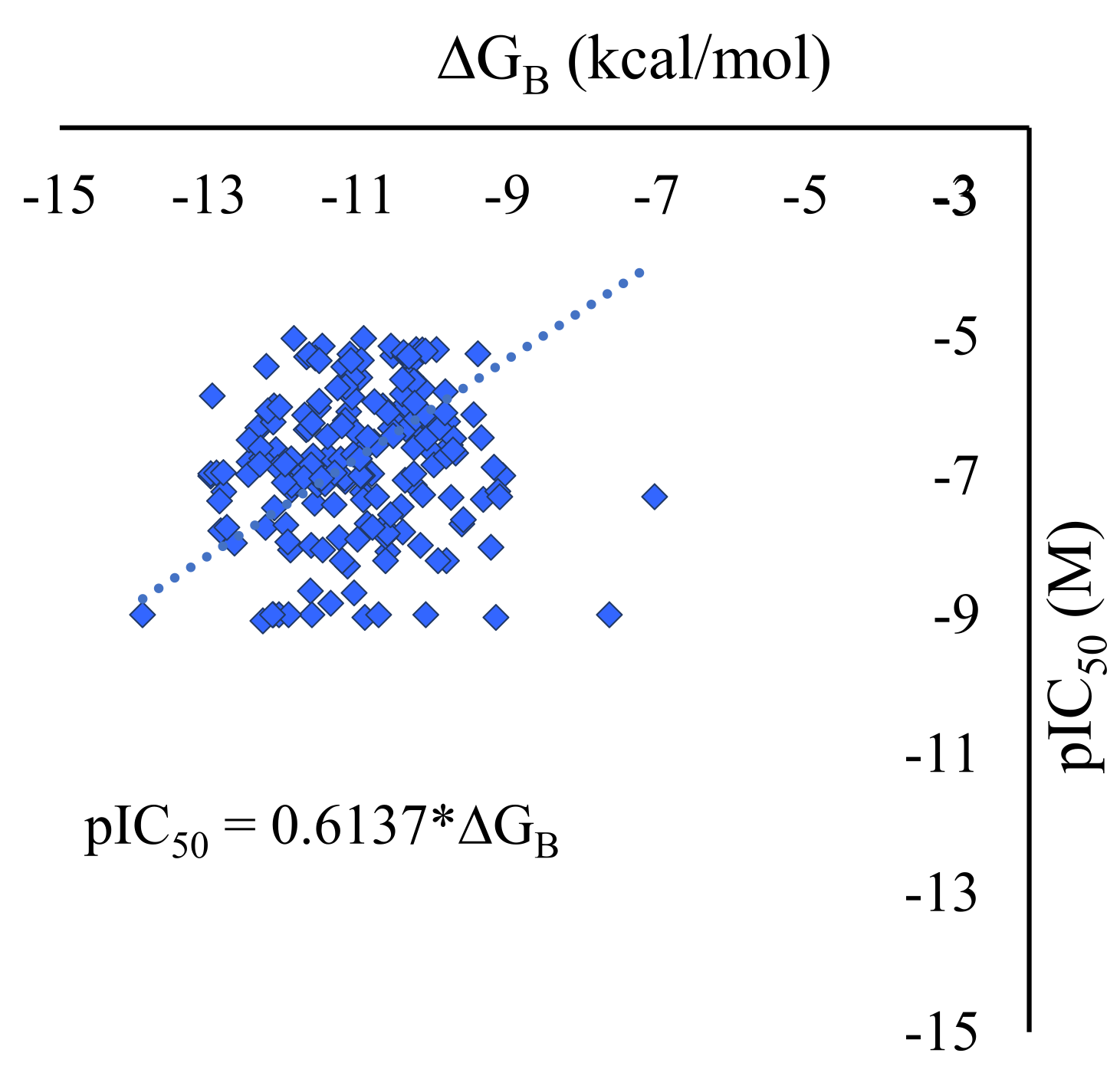

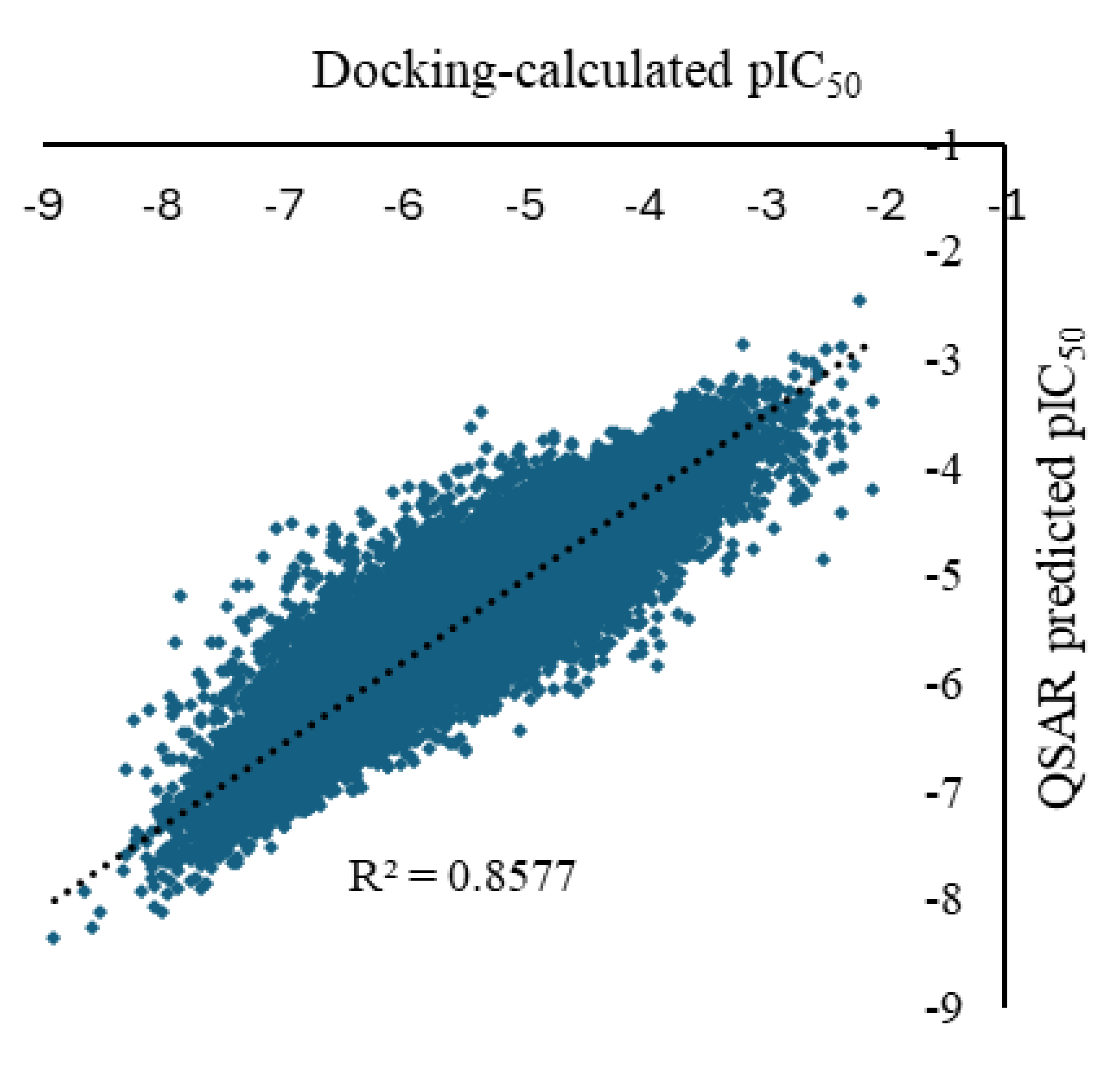

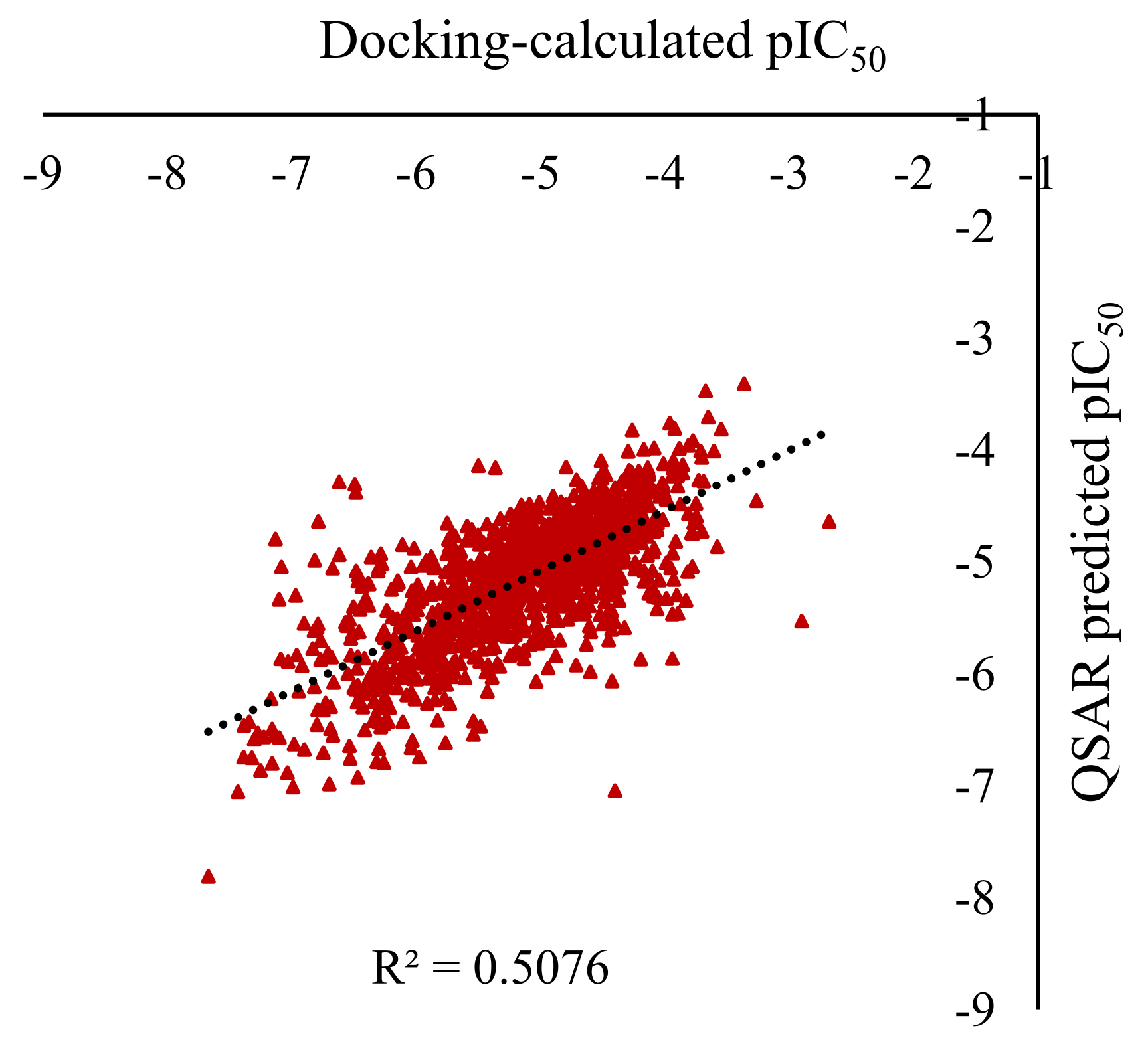

2.1. Docking score for the estimation of IC50 values

2.2. QSDAR Regression Modelling

2.2.1. Dataset

2.2.2. Spectral Data

2.2.3. QSDAR Model Development

2.3. Benchmarking with QSAR Using Molecular, Fingerprint, and Quantum Descriptors

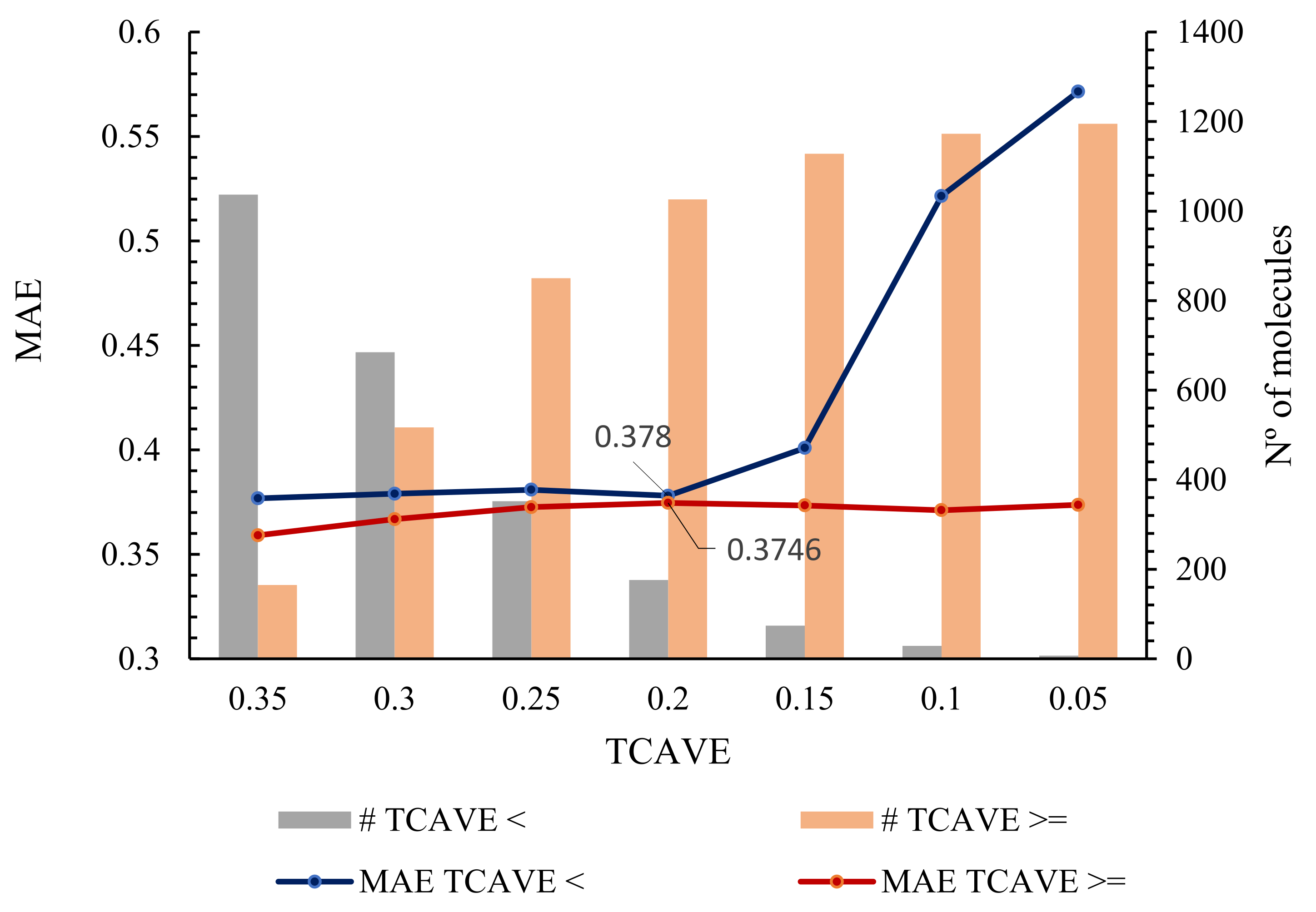

2.4. Applicability Domain of PD-L1 QSDAR Model

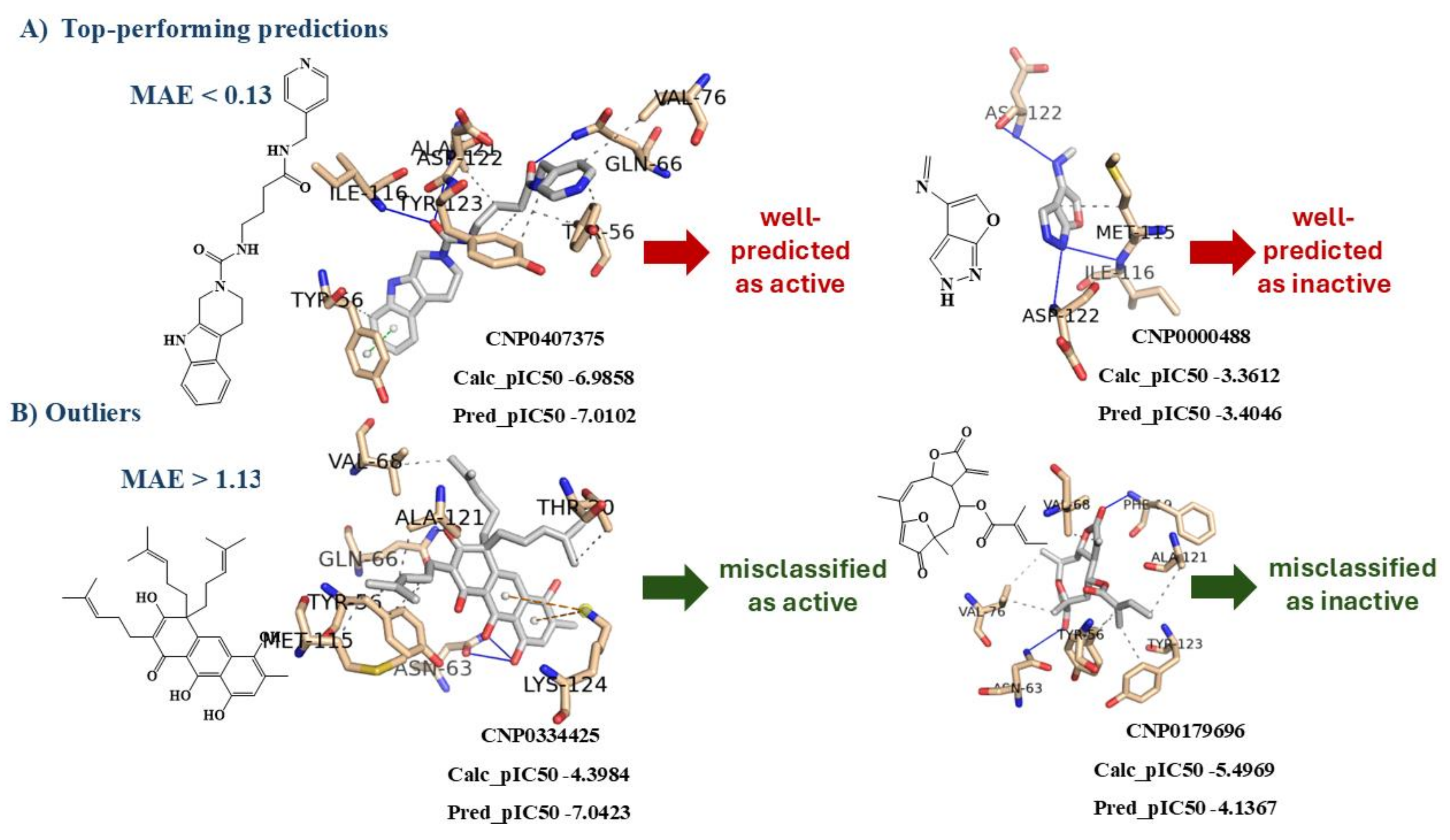

2.5. Analysis the Test Set Predictions with PD-L1 QSDAR Model

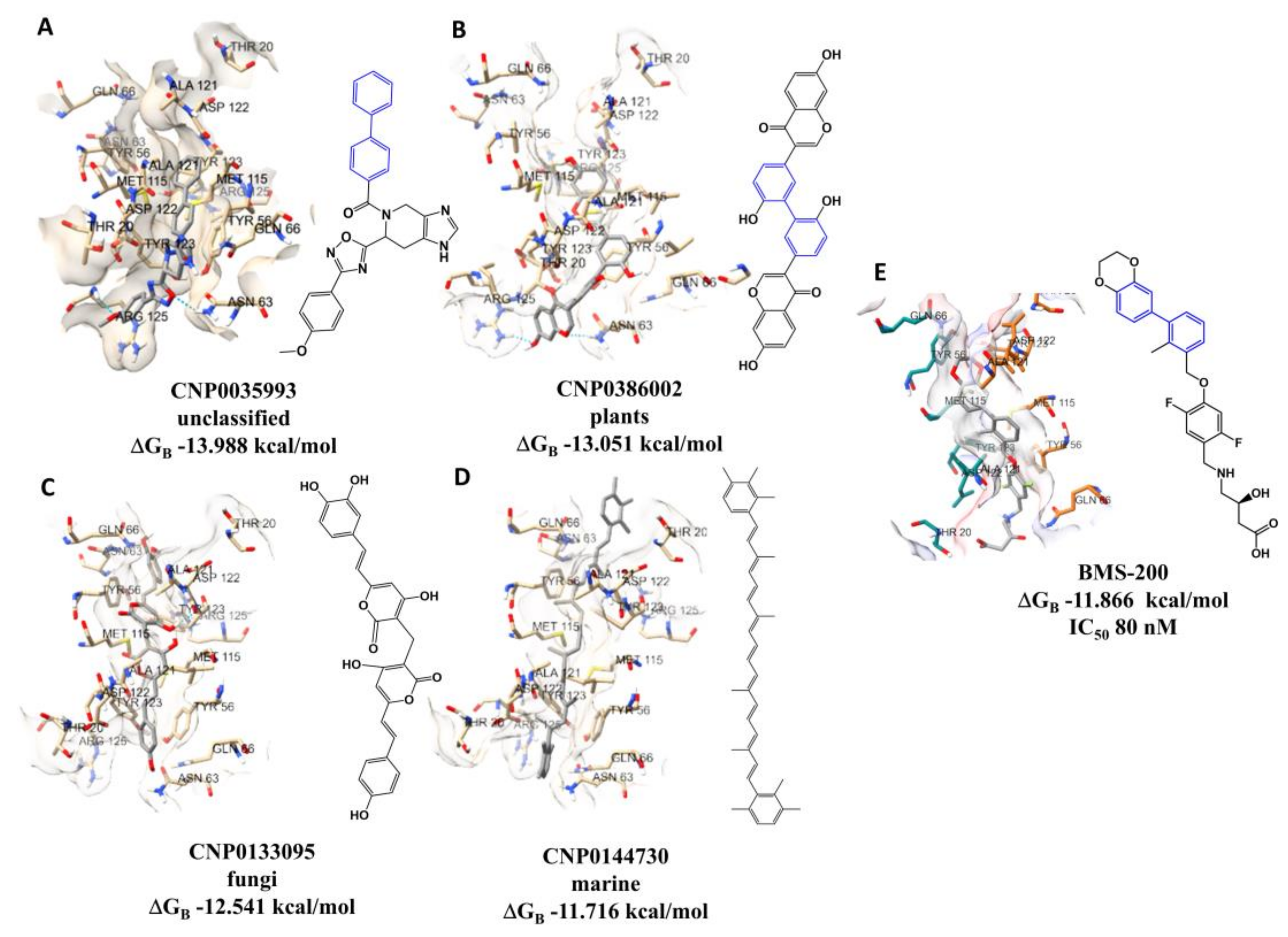

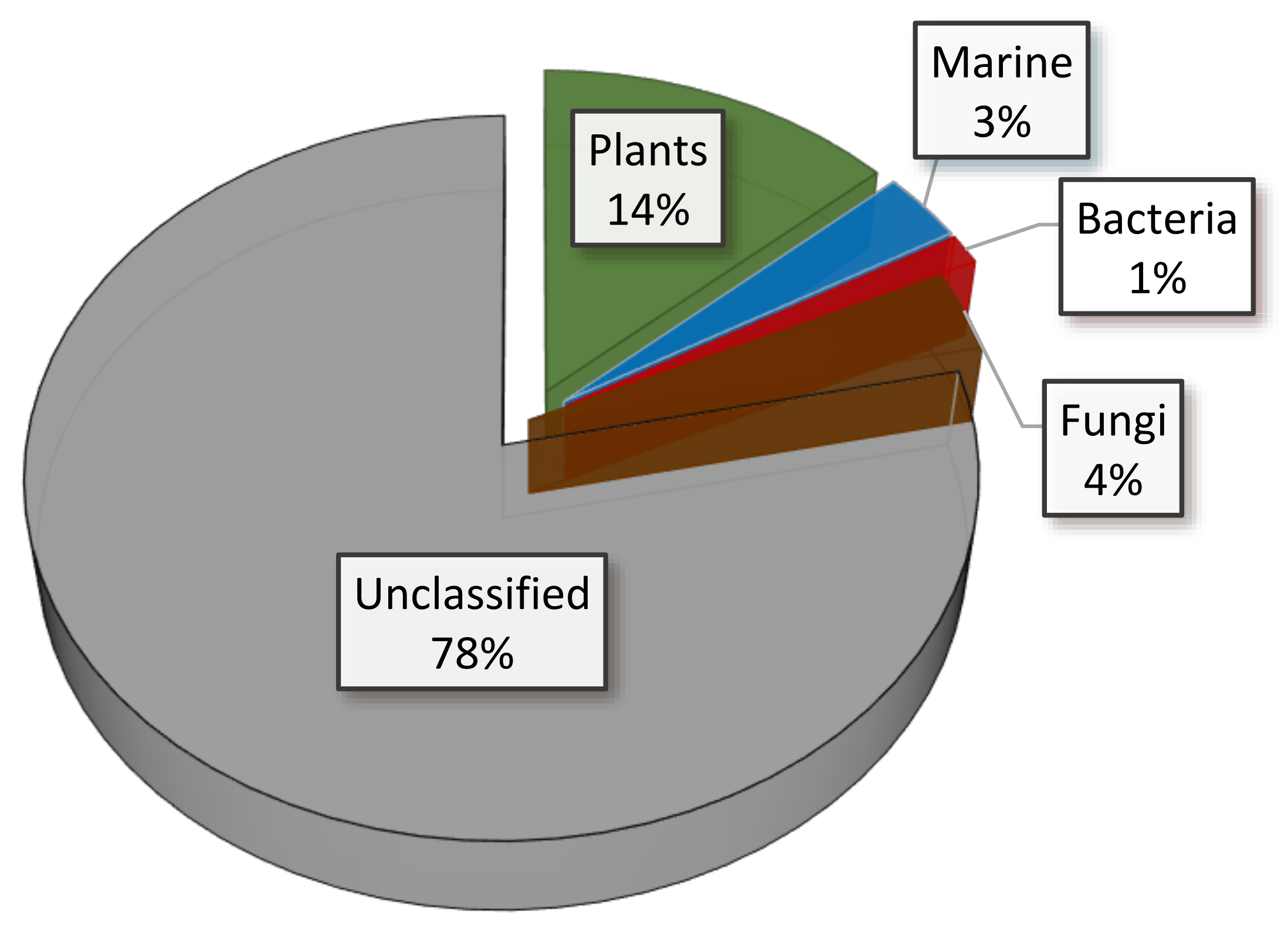

2.6. Virtual Screening

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Datasets: Training and Test Sets

3.2. Molecular Docking

3.3. ML Techniques

3.3.1. Random Forest (RF)

3.3.2. Support Vector Machines (SVM)

3.3.3. Deep Learning Multilayer Perceptron Networks (dMLP)

3.3.4. Light Gradient-Boosting Machine (LightGBM)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaudencio, S.P.; Bayram, E.; Lukic Bilela, L.; Cueto, M.; Diaz-Marrero, A.R.; Haznedaroglu, B.Z.; Jimenez, C.; Mandalakis, M.; Pereira, F.; Reyes, F.; et al. Advanced Methods for Natural Products Discovery: Bioactivity Screening, Dereplication, Metabolomics Profiling, Genomic Sequencing, Databases and Informatic Tools, and Structure Elucidation. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, F.; Aires-de-Sousa, J. Computational Methodologies in the Exploration of Marine Natural Product Leads. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F. The Pharmaceutical Industry in 2020. An Analysis of FDA Drug Approvals from the Perspective of Molecules. Molecules 2021, 26, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, M.M.; Al-Obaidi, Z.; Kitchen, P.; Loreto, A.; Bill, R.M.; Wade-Martins, R. Advances in Applying Computer-Aided Drug Design for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Aouidate, A.; Wang, S.; Yu, Q.; Li, Y.; Yuan, S. Discovering Anti-Cancer Drugs via Computational Methods. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, P.C.; Wilke, D.V.; Branco, P.C.; Bauermeister, A.; Rezende-Teixeira, P.; Gaudencio, S.P.; Costa-Lotufo, L.V. Enriching cancer pharmacology with drugs of marine origin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F. Have marine natural product drug discovery efforts been productive and how can we improve their efficiency? Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2019, 14, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokina, M.; Merseburger, P.; Rajan, K.; Yirik, M.A.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT online: Collection of Open Natural Products database. J. Cheminform. 2021, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, V.; Rajan, K.; Kanakam, S.R.S.; Sharma, N.; Weißenborn, V.; Schaub, J.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT 2.0: a comprehensive overhaul and curation of the collection of open natural products database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D634–D643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, S.; Bon, R.S.; Kumar, K.; Waldmann, H. Biology-Oriented Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10800–10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, F.; Latino, D.A.R.S.; Gaudencio, S.P. A Chemoinformatics Approach to the Discovery of Lead-Like Molecules from Marine and Microbial Sources En Route to Antitumor and Antibiotic Drugs. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 757–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertl, P.; Roggo, S.; Schuffenhauer, A. Natural product-likeness score and its application for prioritization of compound libraries. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008, 48, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, J.; Hu, B.; Wang, J.; Zhu, F.; Kang, Y.; Li, D.; Sun, H.; Kong, D.-X.; Hou, T. A cheminformatic insight into the differences between terrestrial and marine originated natural products. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F. Machine Learning Methods to Predict the Terrestrial and Marine Origin of Natural Products. Mol. Inform. 2021, 40, 2060034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Song, Y.X.; Zhang, X.C. Relationship of Programmed Death-1 (PD-1) and Programmed Death Ligand-1 (PD-L1) Polymorphisms with Overall Cancer Susceptibility: An Updated Meta-Analysis of 28 Studies with 60 612 Subjects. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, P.; Luz, V.; Almeida, J.; Videira, P.; Pereira, F. Computational Approaches Drive Developments in Immune-Oncology Therapies for PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, R.; Wazynska, M.; Magiera-Mularz, K.; Plewka, J.; Musielak, B.; Surmiak, E.; Sala, D.; Kitel, R.; de Bruyn, M.; Nijman, H.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Imidazopyridines as PD-1/PD-L1 Antagonists. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczny, M.; Musielak, B.; Kocik, J.; Skalniak, L.; Sala, D.; Czub, M.; Magiera-Mularz, K.; Rodriguez, I.; Myrcha, M.; Stec, M.; et al. Di-bromo-Based Small-Molecule Inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 11271–11285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Qi, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Wang, K.; Cheng, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, S. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of PD-1/PD-L1 Antagonists Bearing a Benzamide Scaffold. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszak, D.; Surmiak, E.; Plewka, J.; Magiera-Mularz, K.; Kocik-Krol, J.; Musielak, B.; Sala, D.; Kitel, R.; Stec, M.; Weglarczyk, K.; et al. Terphenyl-Based Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Programmed Cell Death-1/Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Protein-Protein Interaction. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 11614–11636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Liu, B.; Peng, X.; Gu, W.; Sun, Y.; Xing, L.; Xu, Y.; Geng, M.; Ai, J.; Zhang, A. Design, Synthesis, and Pharmacological Evaluation of Biaryl-Containing PD-1/PD-L1 Interaction Inhibitors Bearing a Unique Difluoromethyleneoxy Linkage. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 16687–16702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Shen, L.; Xu, H.; Deng, M.; Cheng, M.; Wang, J. Discovery of benzo[d]isothiazole derivatives as novel scaffold inhibitors targeting the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) interaction through "ring fusion" strategy. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 123, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobral, P.; Carvalho, T.; Izadi, S.; Castilho, A.; Silva, Z.; Videira, P.; Pereira, F. Advancements in drug discovery: integrating CADD tools and drug repurposing for PD-1/PD-L1 axis inhibition. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 2298–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, A.; Brant, A.; Santos, J.; Ferreira, M.; Emerenciano, V. Simple Method for Identification of Skeletons of Aporphine Alkaloids from 13C NMR Data Using Artificial Neural Networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Van der Mei, F.; Voutchkova-Kostal, A. Global Model for Octanol-Water Partition Coefficients from Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra. Molecular Informatics 2014, 33, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, L.; Fernandes, M.; Muramatsu, E.; Emereciano, V.; Tavares, J.; da Silva, M.; Scotti. 13C NMR spectral data and molecular descriptors to predict the antioxidant activity of flavonoids. Braz. J. Pharm. 2011, 47, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latino, D.; Alres-De-Sousa, J. Linking Databases of Chemical Reactions to NMR Data: an Exploration of 1H NMR-Based Reaction Classification. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latino, D.; Aires-de-Sousa, J. Automatic NMR-Based Identification of Chemical Reaction Types in Mixtures of Co-Occurring Reactions. PLoS One 2014, 9, e88499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.; Gomes, S.E.; Borralho, P.M.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Gaudencio, S.P.; Pereira, F. In Silico HCT116 Human Colon Cancer Cell-Based Models En Route to the Discovery of Lead-Like Anticancer Drugs. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, T.; Gaudencio, S.P.; Pereira, F. A Computer-Driven Approach to Discover Natural Product Leads for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection Therapy. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto-Davo, A.; Dias, T.; Gomes, S.E.; Rodrigues, S.; Parera-Valadezl, Y.; Borralho, P.M.; Pereira, F.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Santos-Sanches, I.; Gaudencio, S.P. The Madeira Archipelago As a Significant Source of Marine-Derived Actinomycete Diversity with Anticancer and Antimicrobial Potential. Front. microbiol. 2016, 7, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzik, K.; Zak, K.; Grudnik, P.; Magiera, K.; Musielak, B.; Törner, R.; Skalniak, L.; Dömling, A.; Dubin, G.; Holak, T. Small-Molecule Inhibitors of the Programmed Cell Death-1/Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) Interaction via Transiently Induced Protein States and Dimerization of PD-L1. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 5857–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghose, A.; Viswanadhan, V.; Wendoloski, J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1999, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chakraborty, M.; White, A. Predicting chemical shifts with graph neural networks. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 10802–10809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binev, Y.; Aires-De-Sousa, J. Structure-Based Predictions of 1H NMR Chemical Shifts Using Feed-Forward Neural Networks. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binev, Y.; Marques, M.M.B.; Aires-de-Sousa, J. Prediction of H-1 NMR coupling constants with associative neural networks trained for chemical shifts. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 2089–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDKit: Open-Source, Cheminformatics Software, 2016, accessed March 2025.

- Pereira, F.; Xiao, K.; Latino, D.A.R.S.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Aires-de-Sousa, J. Machine Learning Methods to Predict Density Functional Theory B3LYP Energies of HOMO and LUMO Orbitals. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.; Aires-de-Sousa, J. Machine learning for the prediction of molecular dipole moments obtained by density functional theory. J. Cheminform. 2018, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, F.; Fartaria, R.; Latino, D.A.R.S.; Qu, X.; Campos, T.; Zhao, T.; Aires-de-Sousa, J. A QSPR approach for the fast estimation of DFT/NBO partial atomic charges. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2014, 134, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adasme, M.F.; Linnemann, K.L.; Bolz, S.N.; Kaiser, F.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2021: expanding the scope of the protein-ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W530–W534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetnik, V.; Liaw, A.; Tong, C.; Culberson, J.C.; Sheridan, R.P.; Feuston, B.P. Random forest: A classification and regression tool for compound classification and QSAR modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 1947–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RandomForestRegressor — scikit-learn 1.6.0 documentation. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.ensemble.RandomForestRegressor.html (accessed on March 2025).

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Lin, C.-J. LIBSVM: A Library for Support Vector Machines. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2011, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Keras: Deep Learning for humans. Available online: https://keras.io/ (accessed on March 2025).

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Distributed Systems. arXiv, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (Nips 2017) 2017, 30.

| Sets | # | PD-L1 Activity | Drug-likeness | NP-likeness score5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active1 | Inactive2 | MWheatom3 | MolLogP4 | |||

| Training | 119,733 | 62,651 (52%) |

57,082 (48%) |

112,555 (94%) |

100,534 (84%) |

52,640 (44%) |

| Test | 1,202 | 655 (54%) |

547 (46%) |

1,141 (95%) |

1,004 (84%) |

519 (43%) |

| Spectral Descriptors | #1 | R2 | MAE3 | RMSE4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPINUS | 570 | 0.8822 | 0.225 | 0.302 |

| GNN | 250 | 0.7632 | 0.310 | 0.395 |

| SPINUS + GNN | 820 | 0.9112 | 0.198 | 0.263 |

| Model | #1 | R2 | MAE3 | RMSE4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPINUS | 50 | 0.7142 | 0.333 | 0.432 |

| 100 | 0.7872 | 0.293 | 0.382 | |

| 150 | 0.8822 | 0.225 | 0.302 | |

| 200 | 0.8412 | 0.259 | 0.339 |

| Model | R2 | MAE2 | RMSE3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | |||

| RF4 | 0.8821 | 0.225 | 0.302 |

| LightGBM5 | 0.8581 | 0.219 | 0.296 |

| SVM5 | 0.5881 | 0.341 | 0.488 |

| CNN5 | 0.59301 | 0.3530 | 0.4835 |

| Test set | |||

| RF4 | 0.4921 | 0.406 | 0.547 |

| LightGBM5 | 0.5081 | 0.393 | 0.537 |

| SVM5 | 0.4041 | 0.450 | 0.591 |

| CNN5 | 0.45971 | 0.4241 | 0.5611 |

| Descriptors | #1 | R2 | MAE3 | RMSE4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPs | MACCS | 166 | 0.86642 | 0.1982 | 0.2762 |

| Morgan | 1024 | 0.962 | 0.1041 | 0.144 | |

| RDKit | 2048 | 0.972 | 0.0812 | 0.1317 | |

| 1D&2D | 425 | 0.992 | 0.0179 | 0.0269 | |

| 3D | Autocorr3D | 80 | 0.99472 | 0.0393 | 0.0548 |

| Getaway | 271 | 0.992 | 0.0139 | 0.02 | |

| RDF | 210 | 0.992 | 0.0213 | 0.0308 | |

| 3D | 561 | 0.992 | 0.0096 | 0.0139 | |

| Quantum | 5 | 0.65892 | 0.3513 | 0.4484 | |

| Model | #1 | R2 | MAE3 | RMSE4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set5 | ||||

| 1D&2D&3D | 986 | 0.992 | 0.0075 | 0.0111 |

| Test set | ||||

| 1D&2D&3D | 986 | 0.81312 | 0.2493 | 0.3283 |

| Hyperparameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Initializer | Glorot uniform |

| Number of hidden layers | 4 |

| Number of neurons in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th layers | 150 |

| Activation 1st–3rd layers | Relu |

| Activation 4th layer | Relu |

| Batch size | 128 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Epochs | 500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).