Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Design Requirements

3. Formulation of a Concept of Radar Antennas for CA Systems

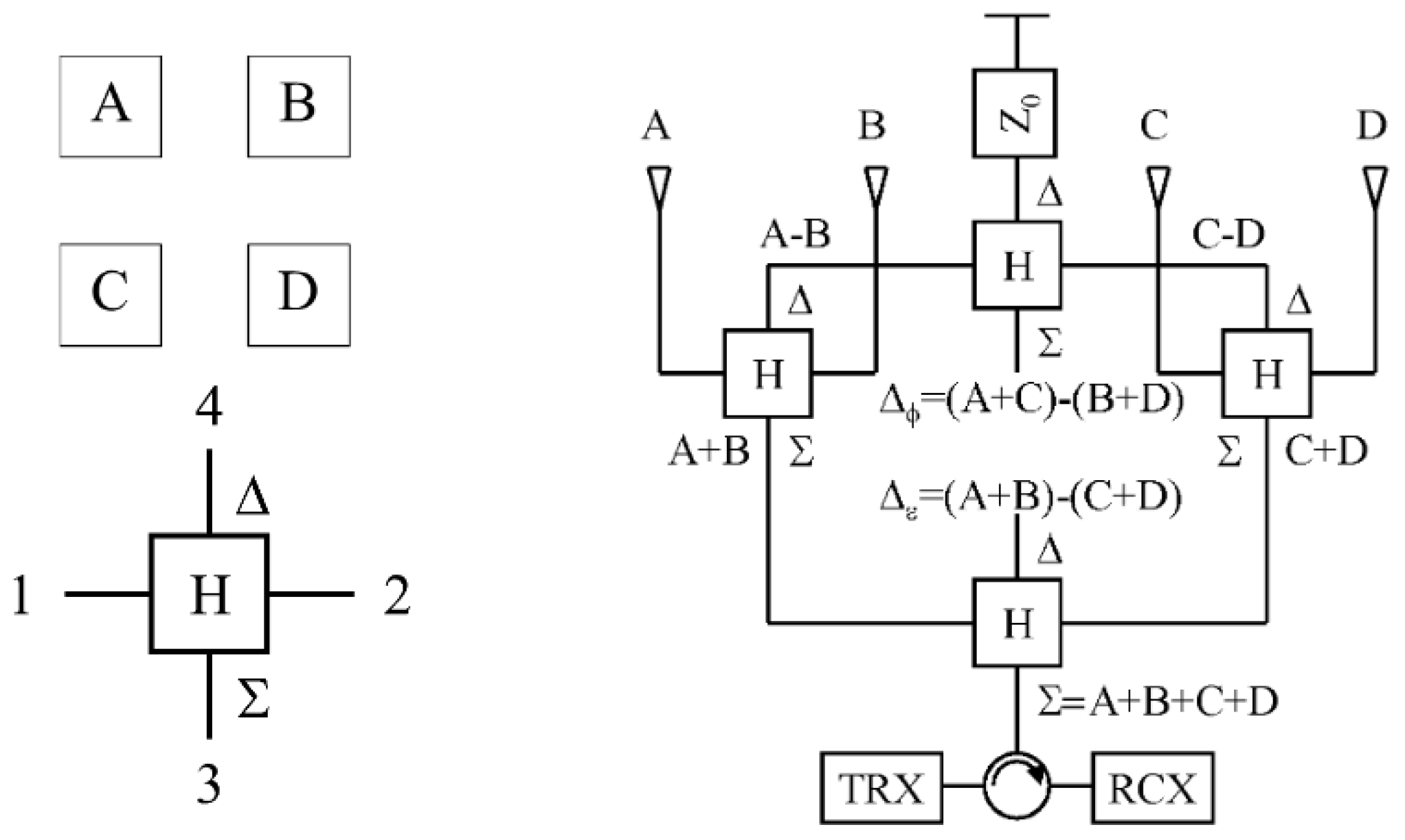

3.1. Identification of a Candidate Architecture

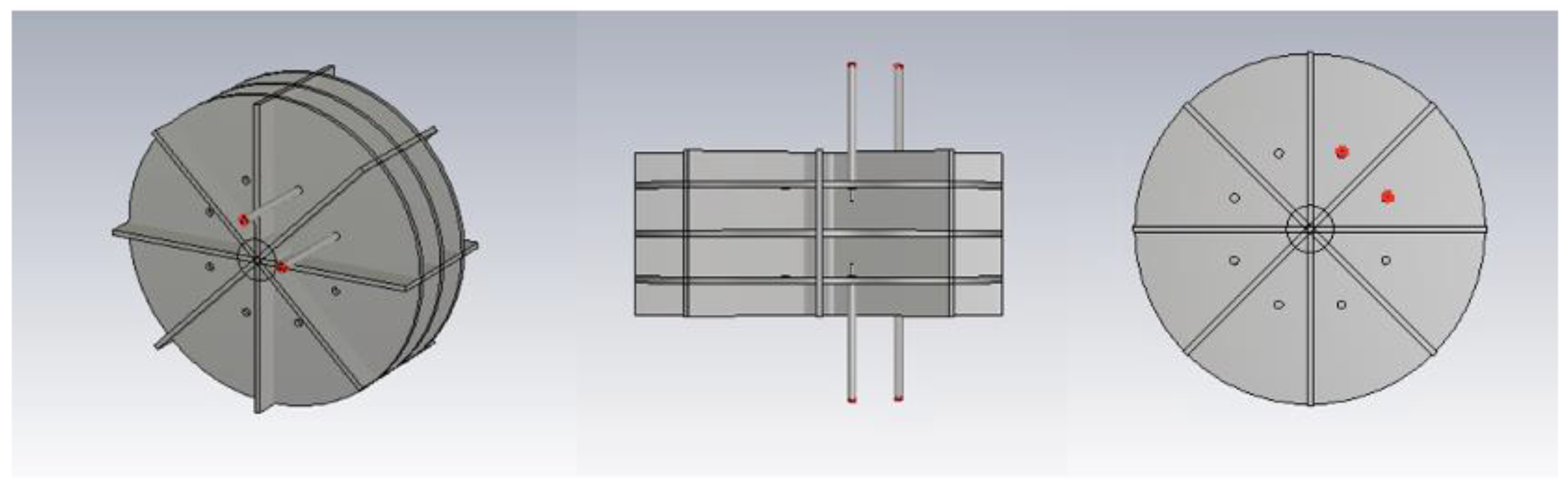

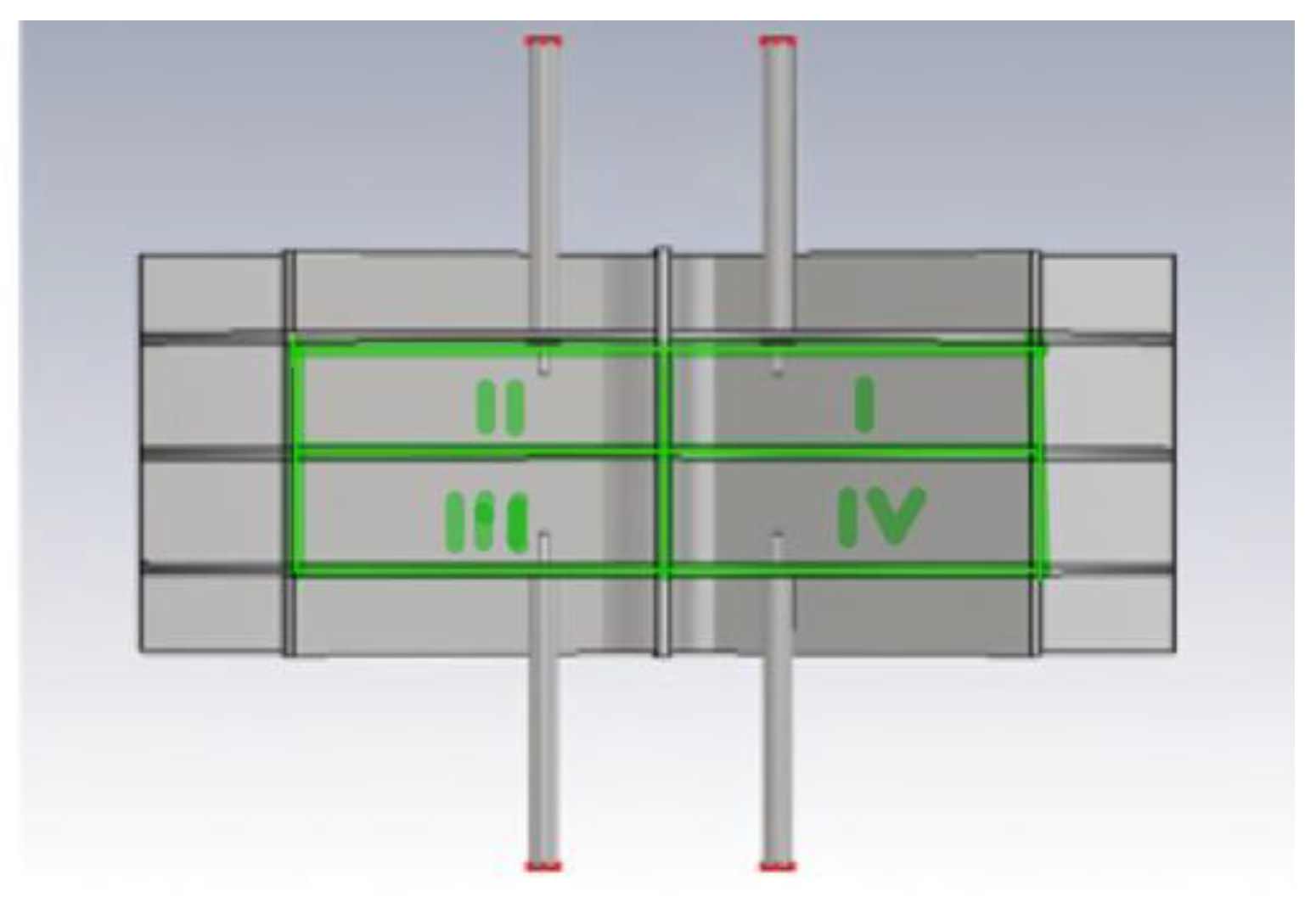

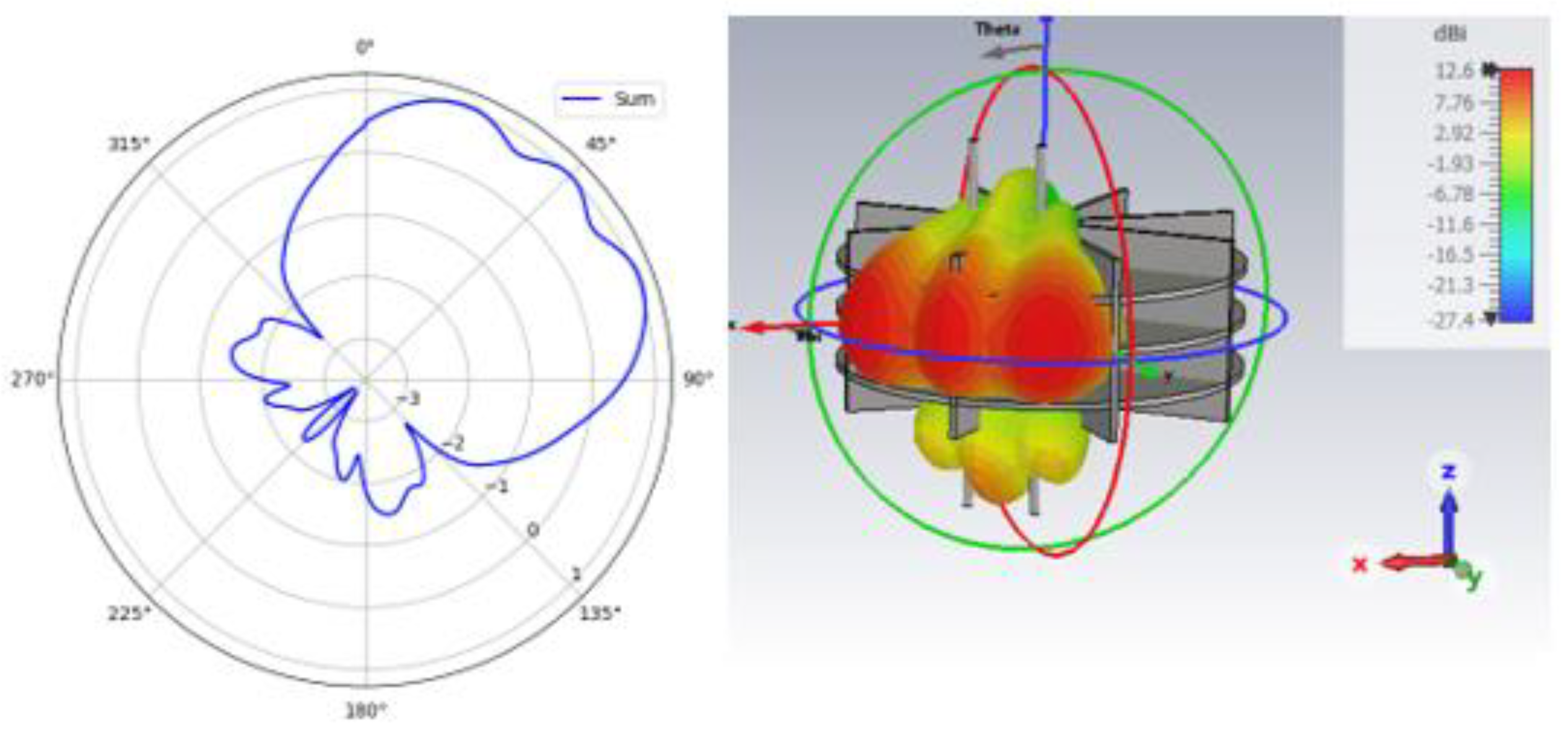

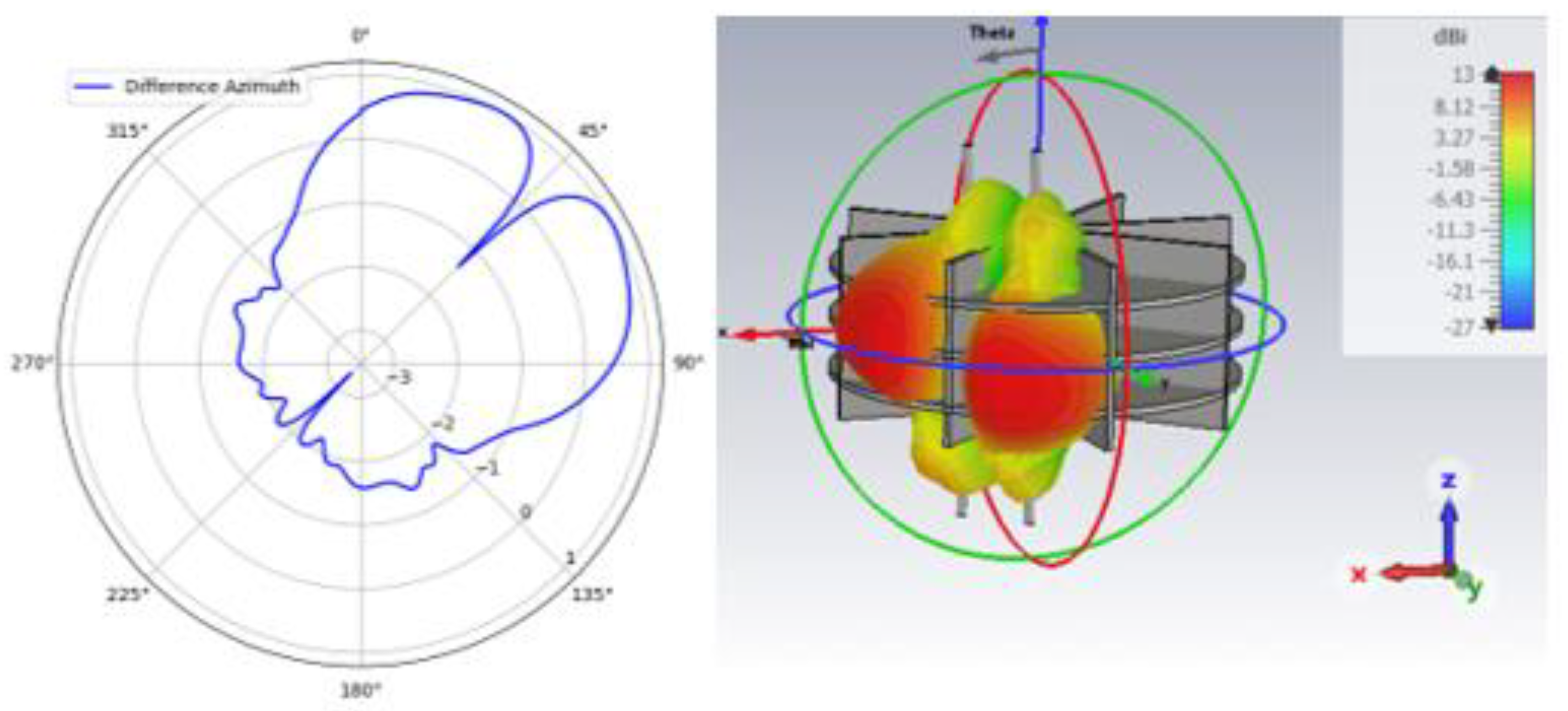

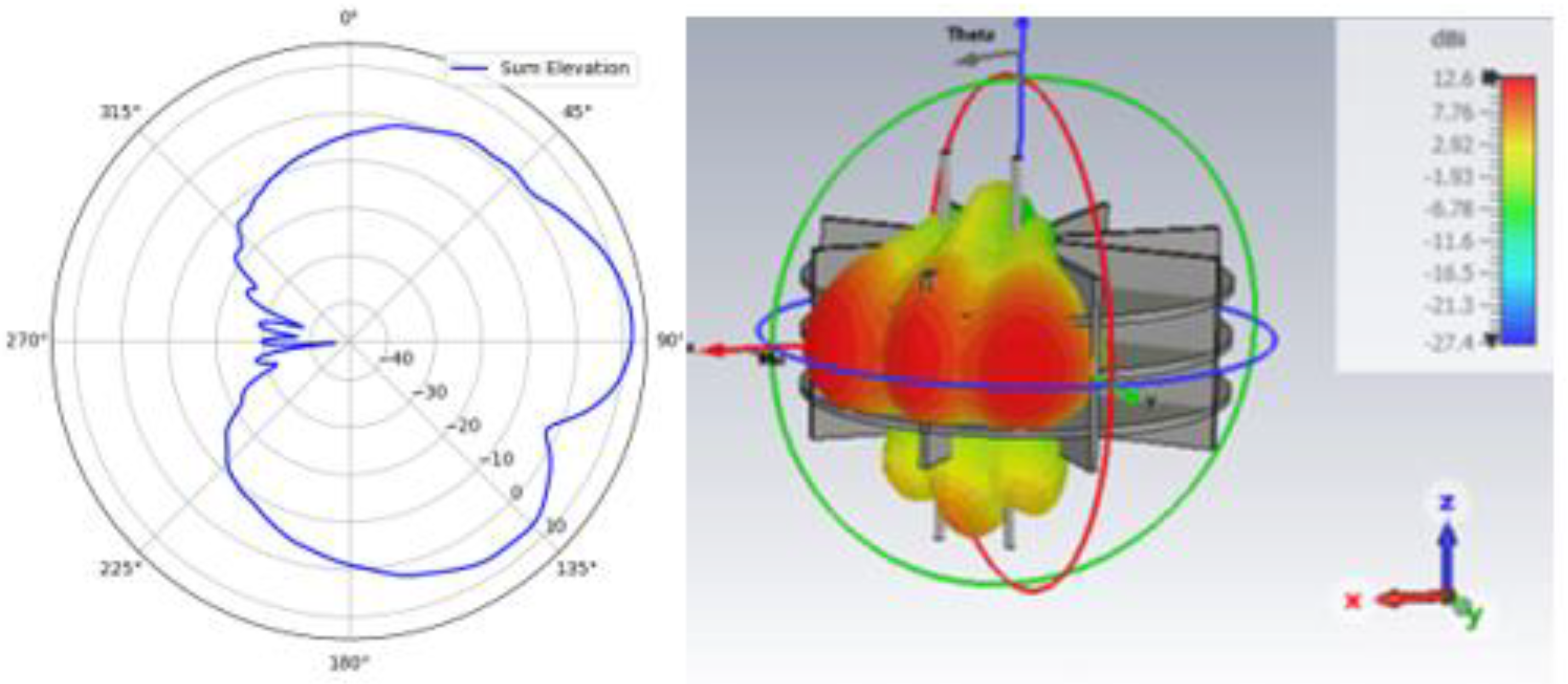

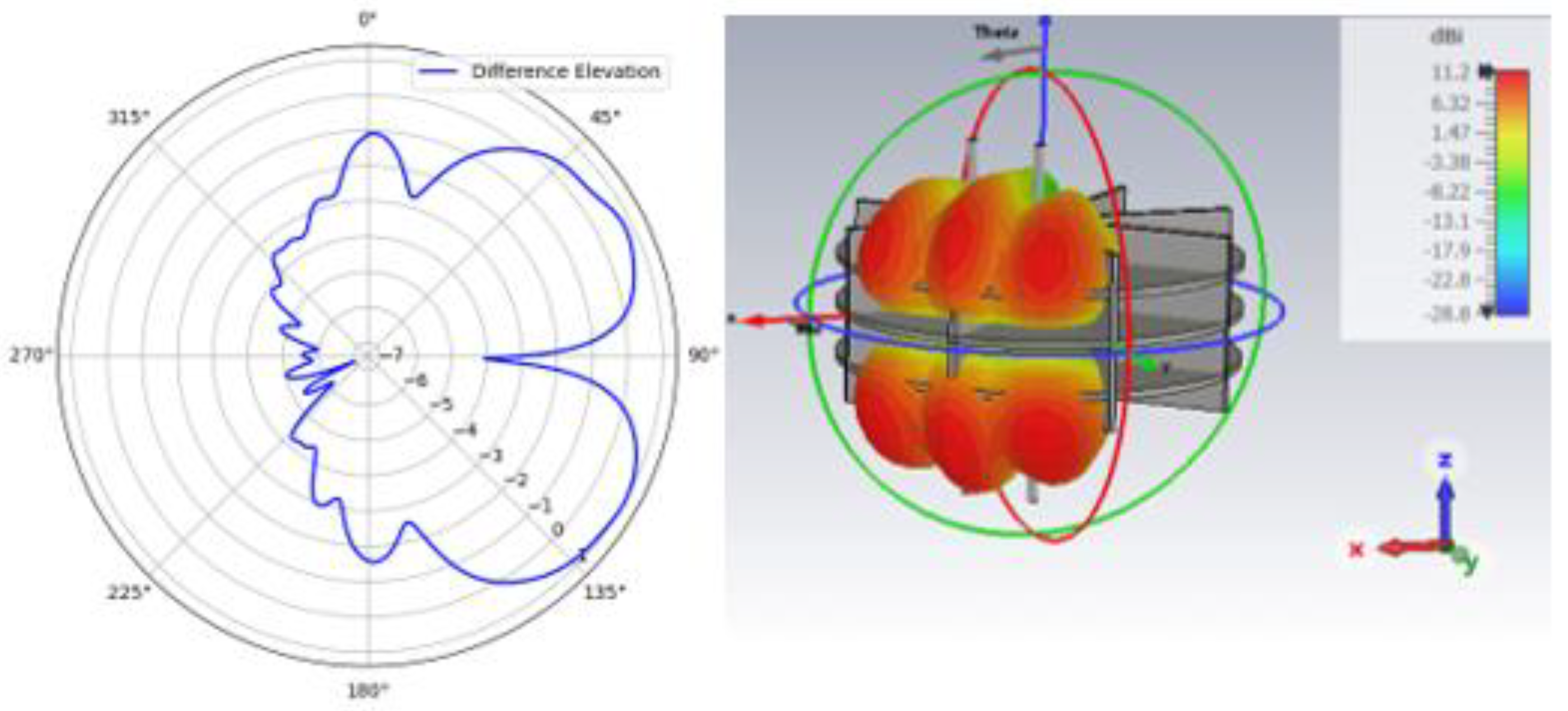

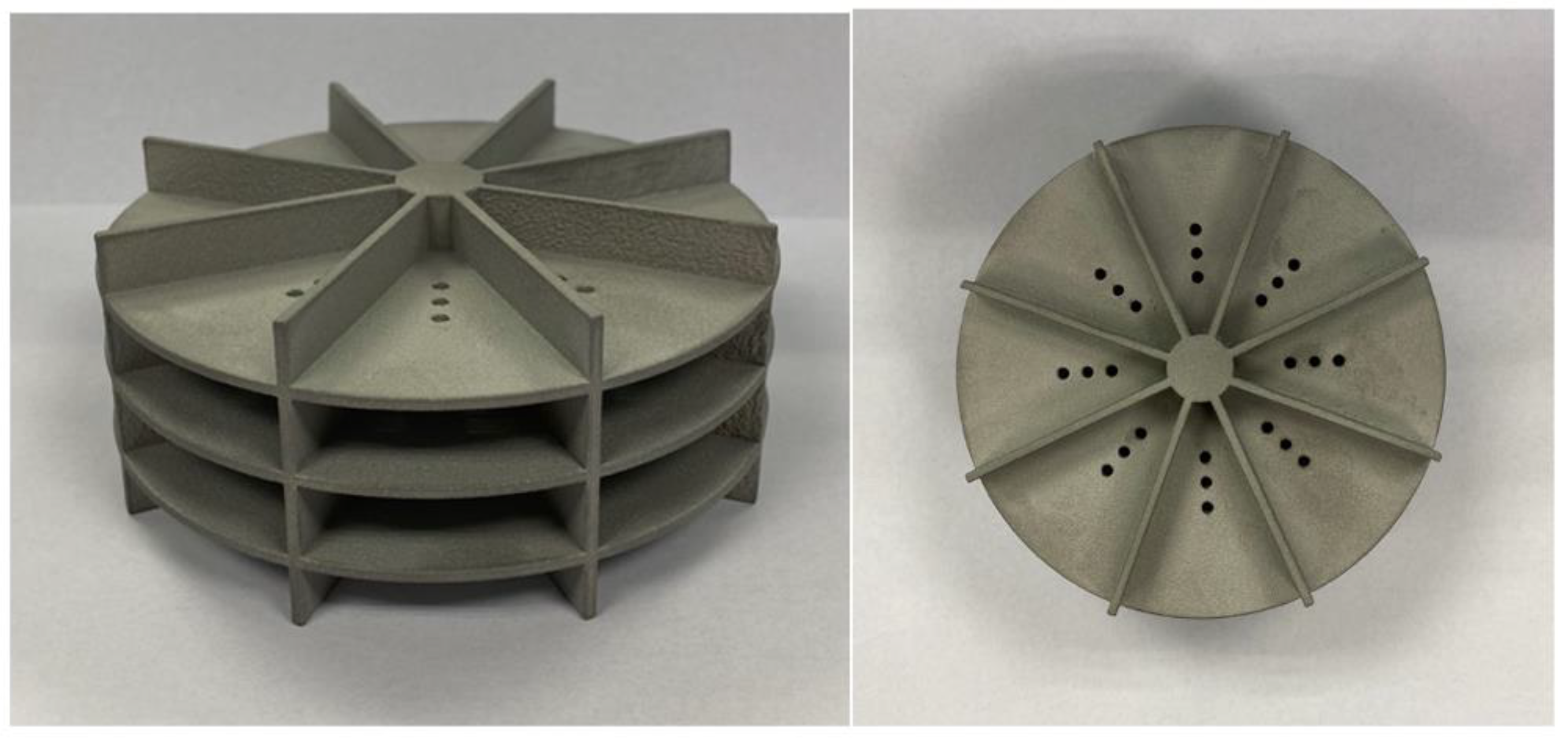

3.2. Design of a Prototype Implementing the Candidate Architecture

4. Experimental Proof of Concept

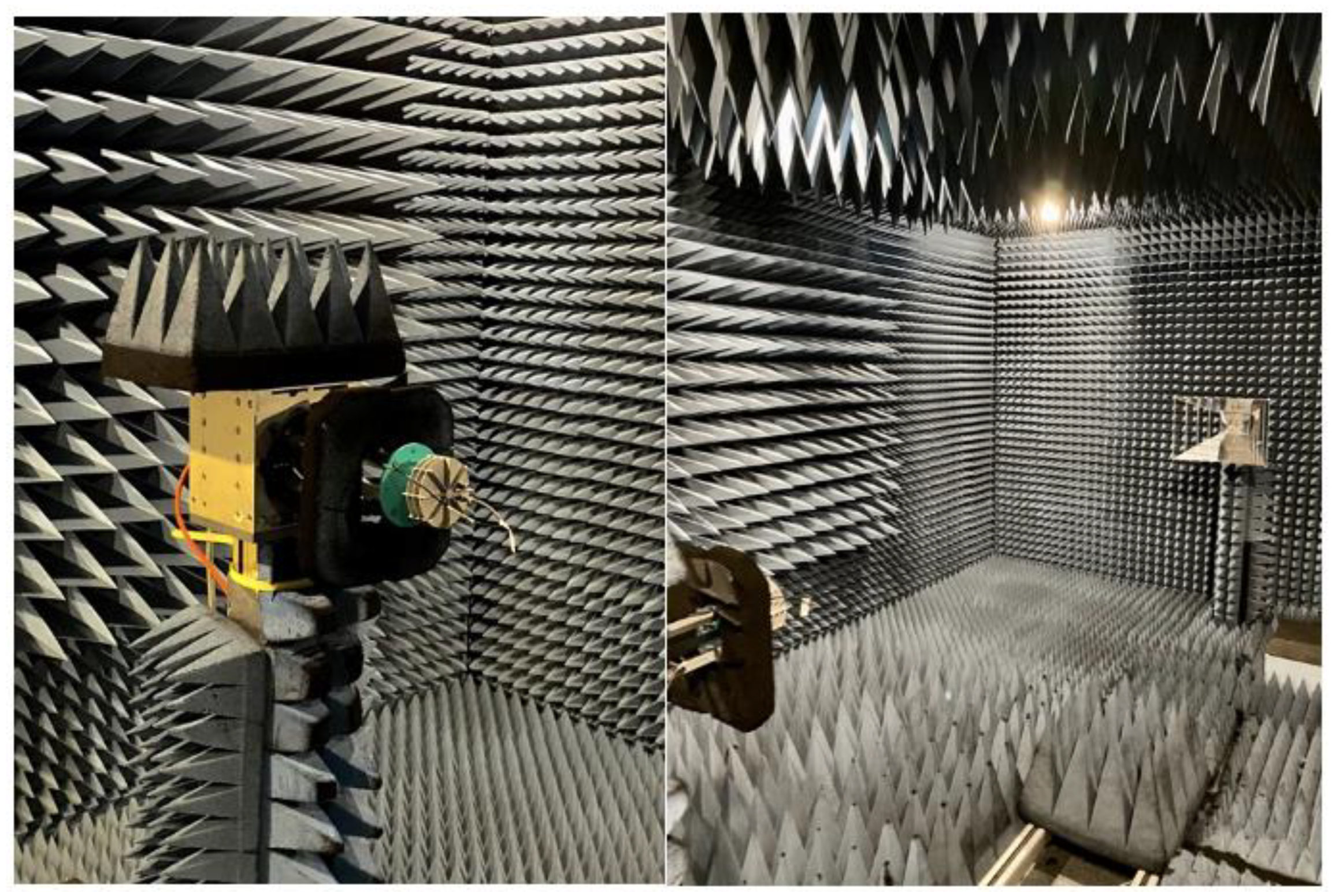

4.1. Material and Methods

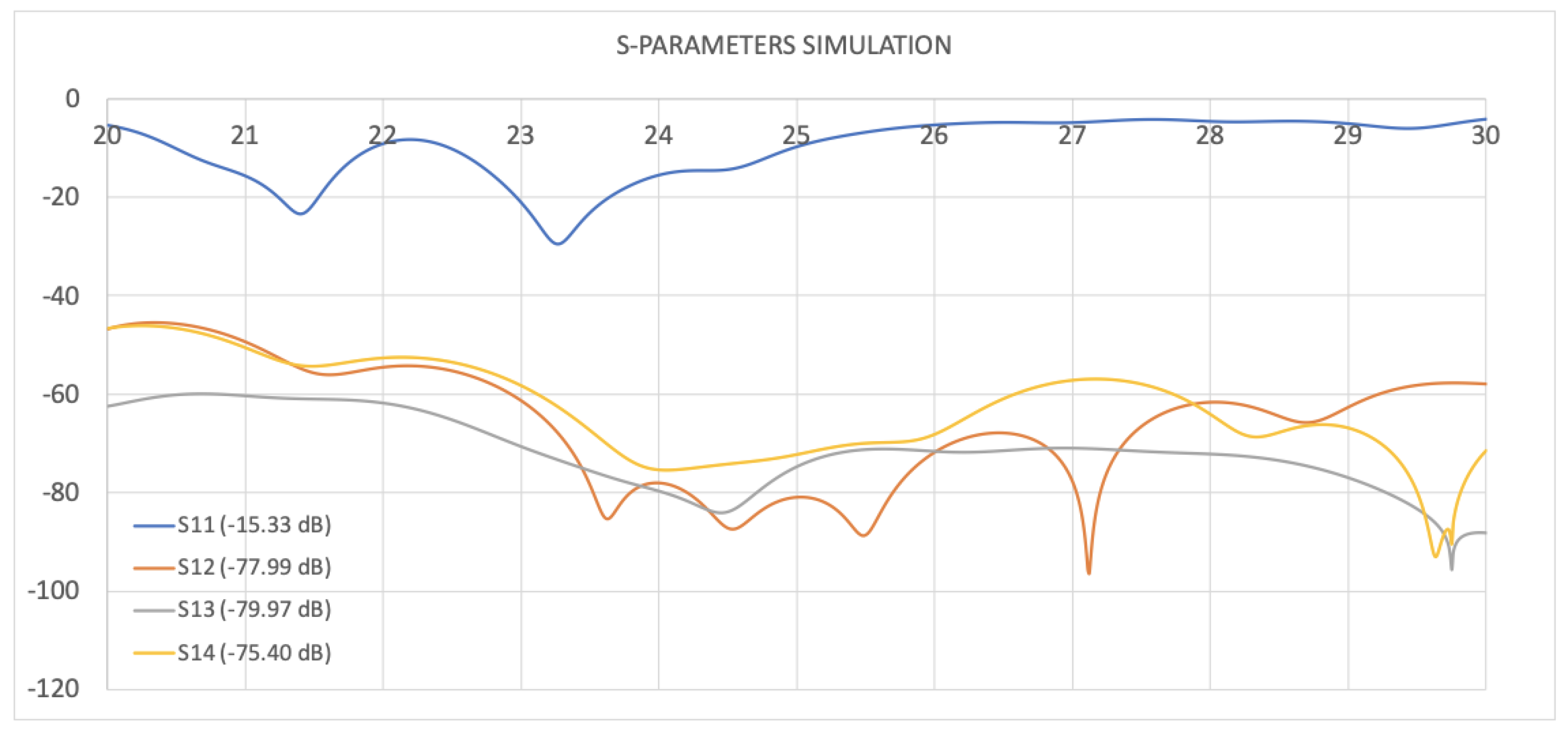

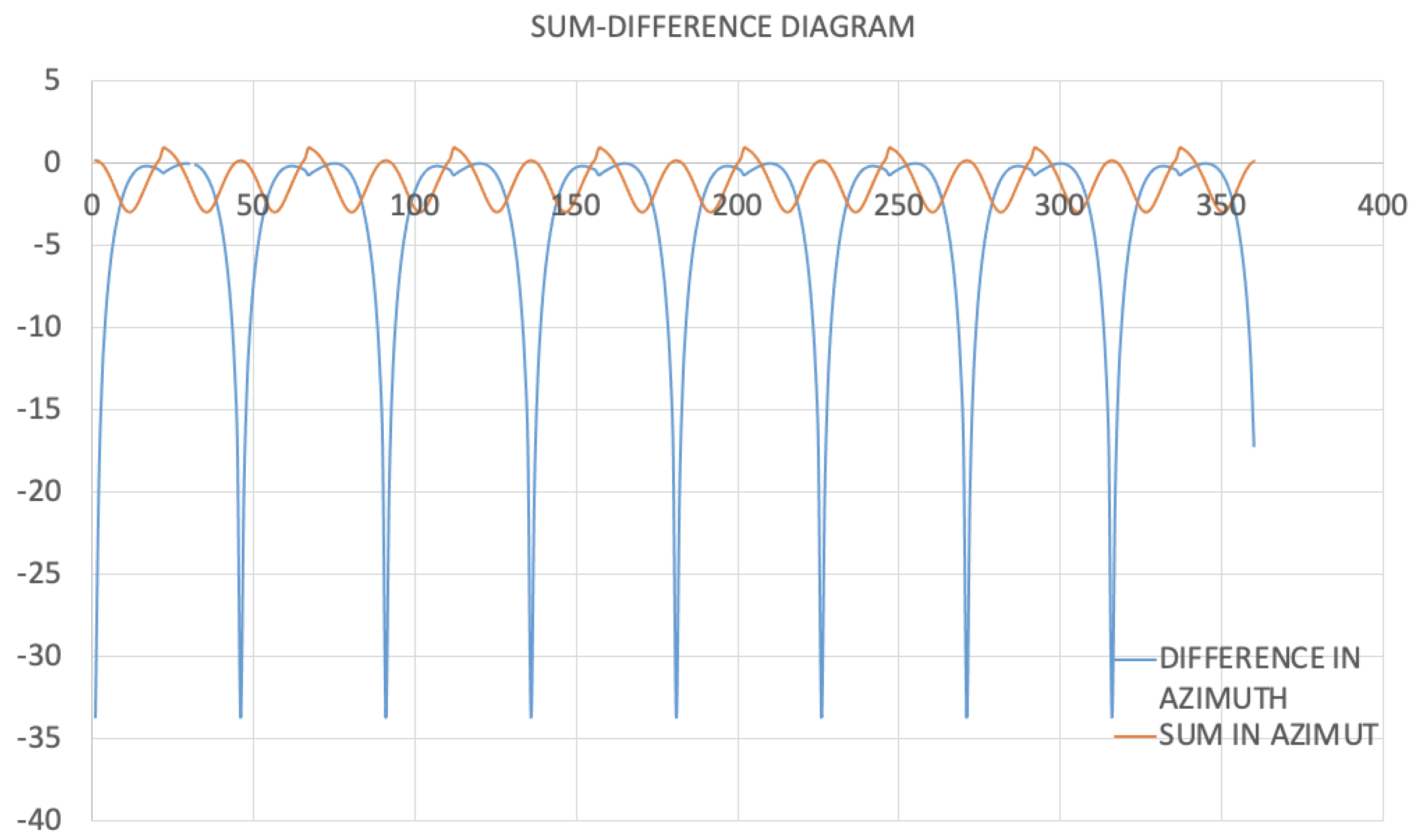

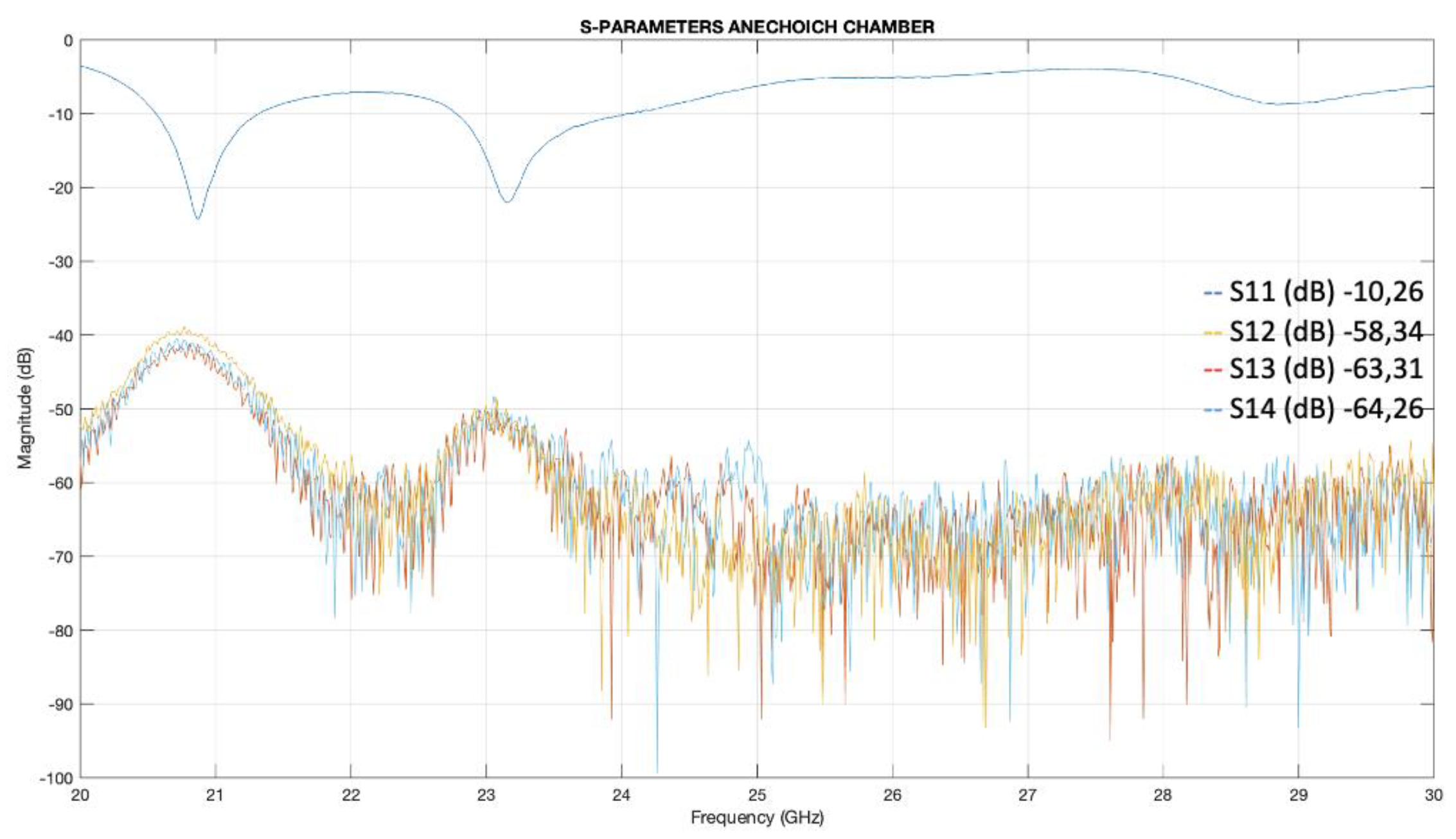

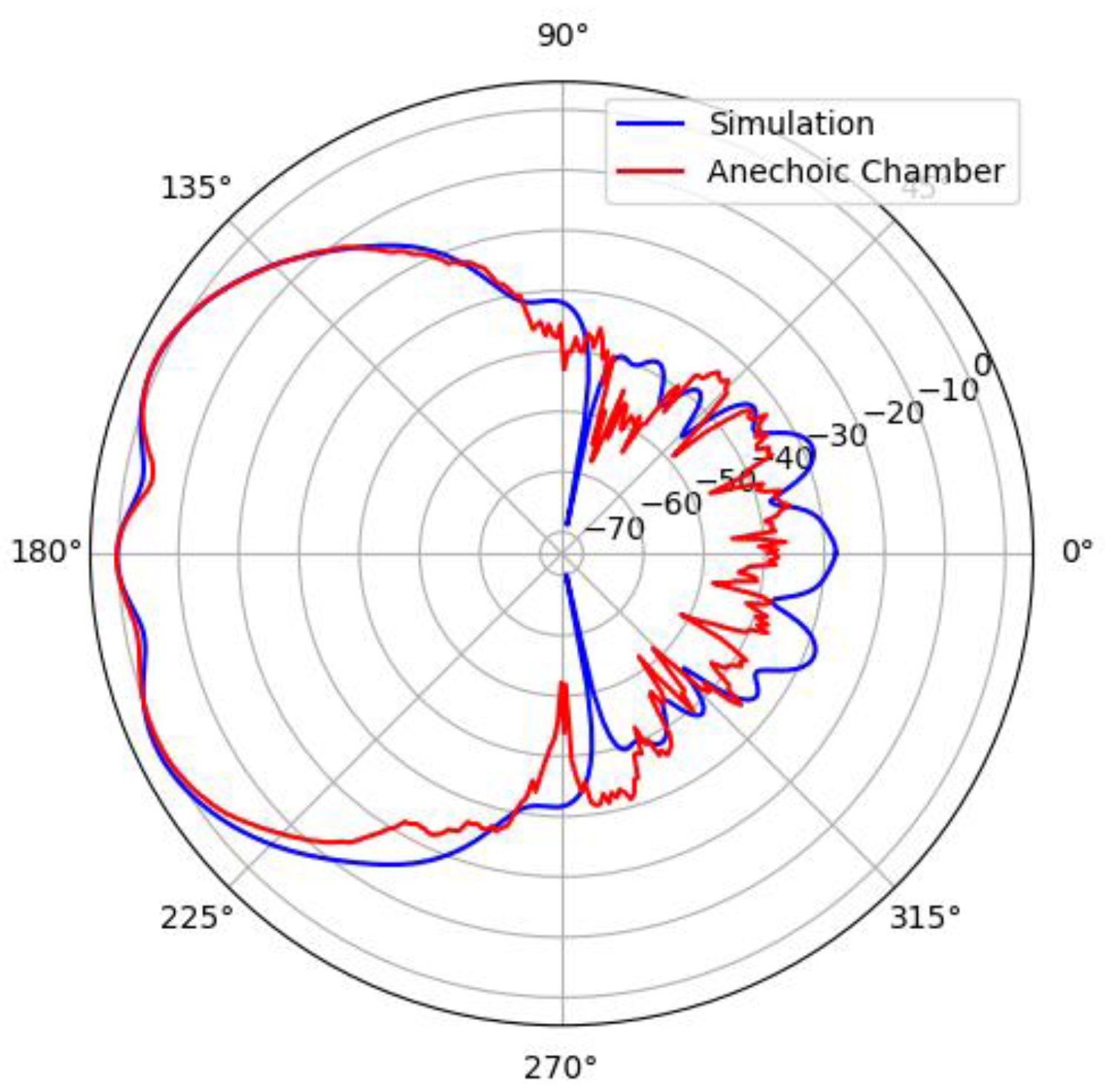

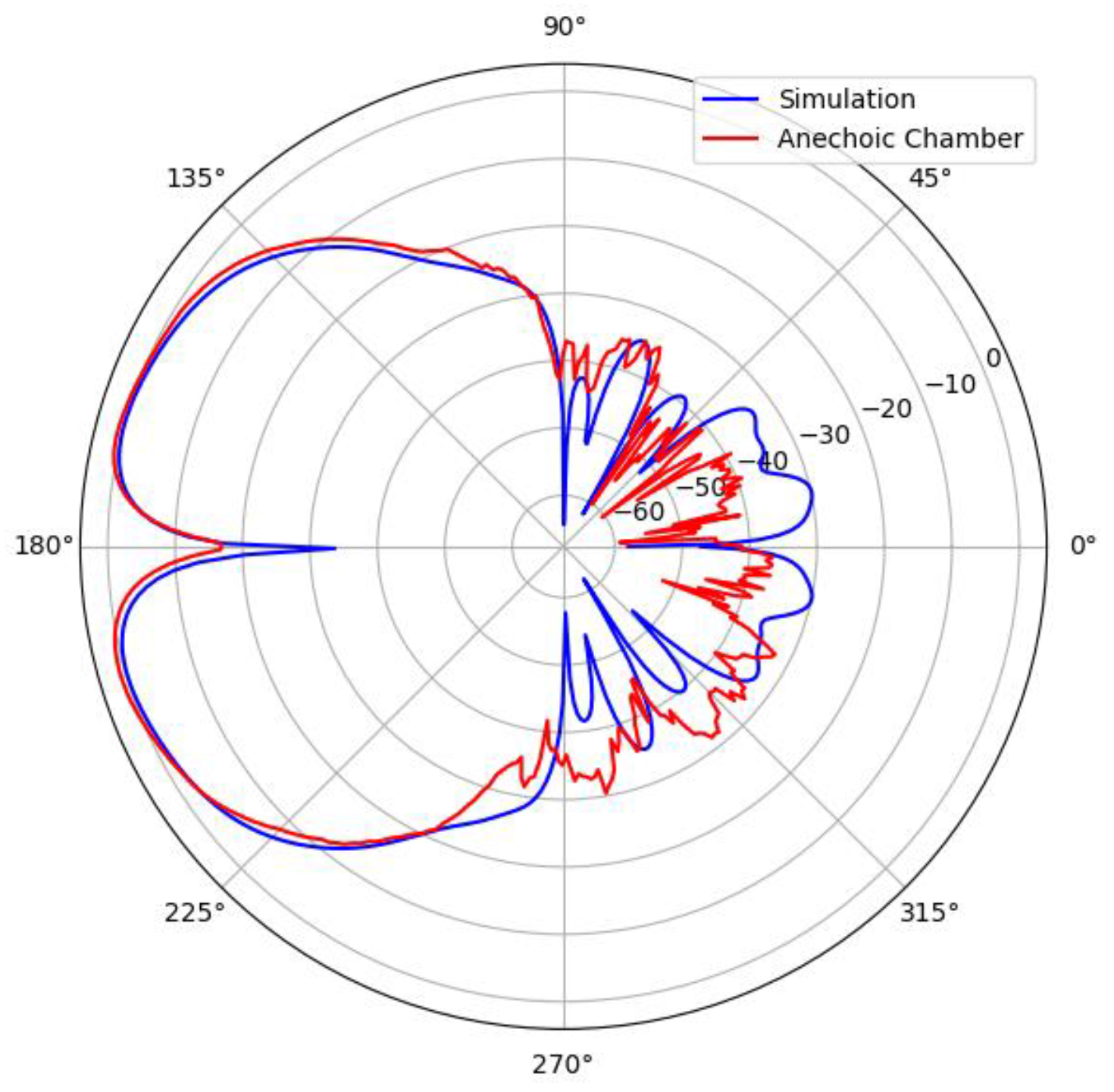

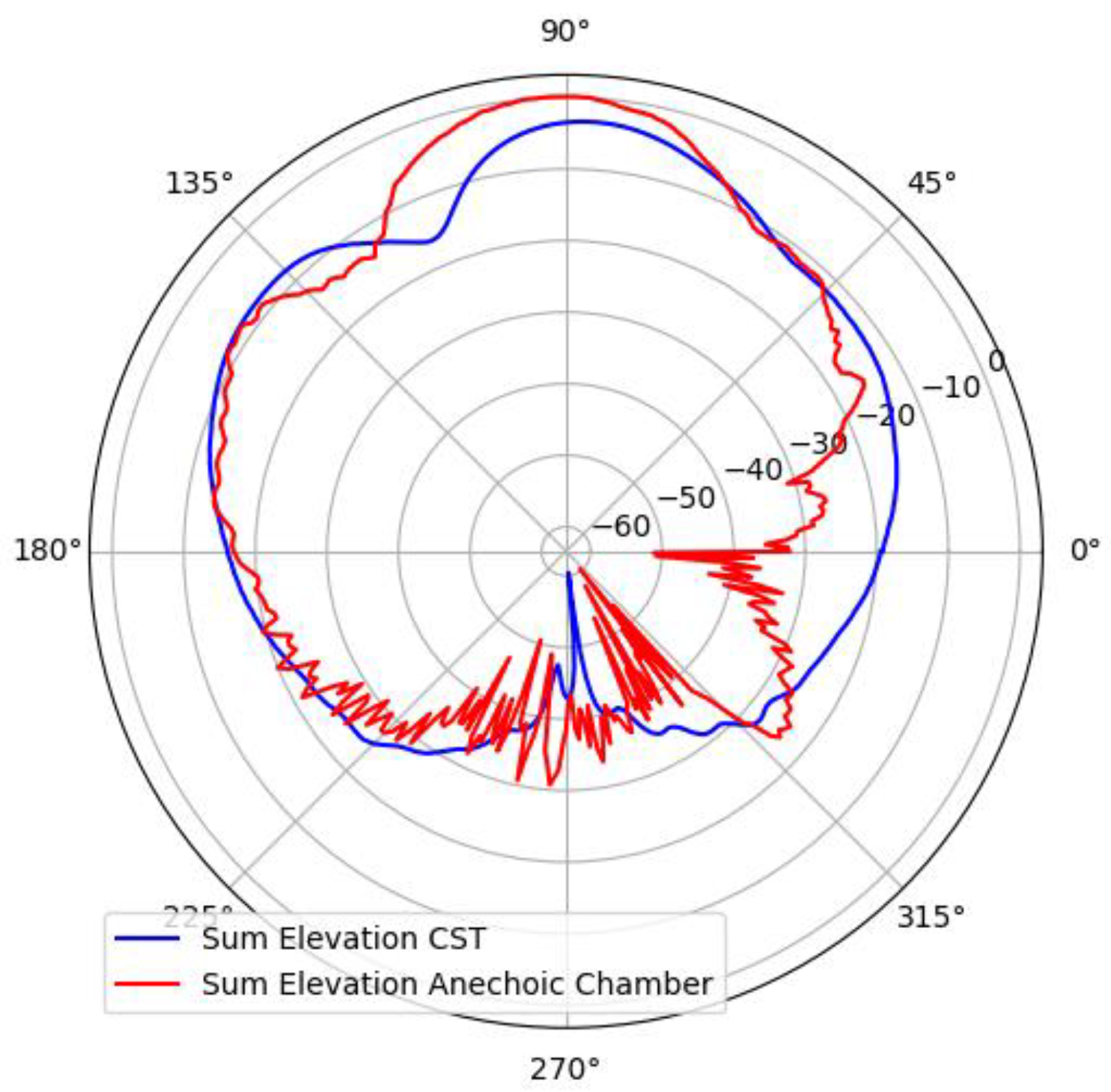

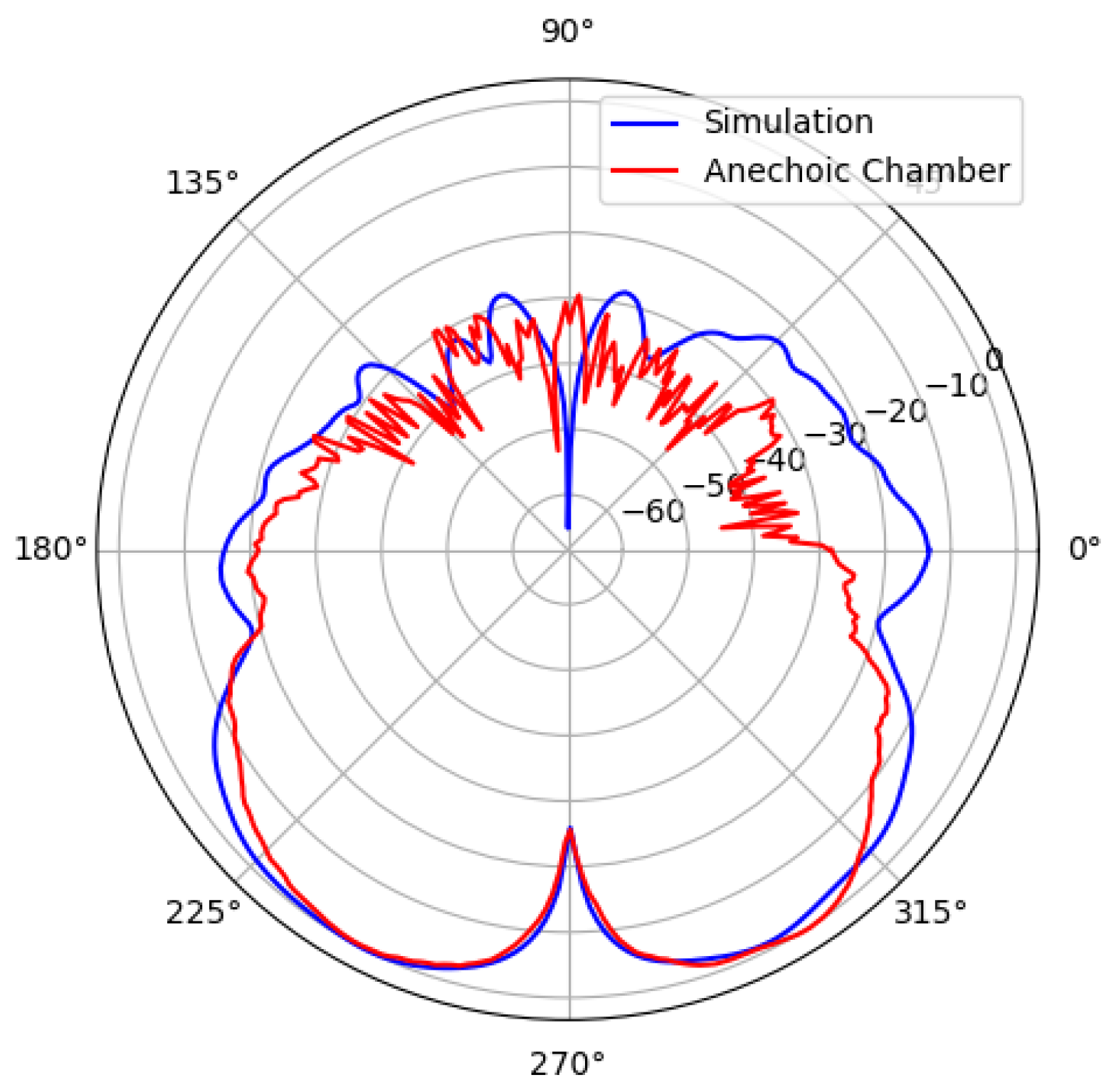

4.2. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAM | Advanced Air Mobility |

| ACAS | Airborne Collision Avoidance System |

| APL | Antennas and Propagation Lab |

| ARC | Air Risk Class |

| ATAR | Air-to-Air RADAR |

| CA | Collision Avoidance |

| ConOps | Concept of Operation |

| COTS | Commercial-Off-The-Shelf |

| CW-LFM | Continuous Wave, Linearly Frequency Modulated, |

| DAA | Detect and Avoid |

| EEA | European Economic Area |

| EU | European Union |

| EUROCAE | European Organisation for Civil Aviation Equipment |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| FOV | Field of Vision |

| GA | General Aviation |

| GRC | Ground Risk Class |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organisation |

| IFR | Instrumental Flight Rules |

| ISM | Industrial, Medical and Scientific |

| MAC | Mid-air collision |

| MOPS | Minimum Operational Performance Standard |

| NMAC | Near Mid-Air Collision |

| OSED | Operational Services and Environment Description |

| RCS | Radar Cross Section |

| RTCA | Radiotechnical Commission for Aeronautics |

| RWC | Remain Well Clear |

| SC | Special Committee |

| SESAR | Single European Sky Air Traffic Management Research |

| SLM | Selective Laser Melting |

| sNMAC | small UAS NMAC |

| SORA | Specific Operations Risk Assessment |

| sUA | Small UA |

| SWAP | Size, Weight, and Power |

| TCR | Tactical Conflict Resolution |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| VFR | Visual Flight Rules |

| VLL | Very Low Level |

| UA | Unmanned Aircraft |

| UAM | Urban Air Mobility |

| UAS | Unmanned Aircraft System |

| UTM | Unmanned Aircraft System Traffic Management |

| 1 | Notice that this definition comes from the DO-396 and should not be confused with other similar weight-based definitions commonly used in the literature (such as the small UAS with a maximum take-off weight below 55 pounds). |

References

- Imperial War Museums. Available online: https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/a-brief-history-of-drones (accessed on 17th March 2025).

- Wagner, William, “Lightning Bugs, and other Reconnaissance Drones”, 1982, published by Armed Forces Journal International in cooperation with Aero Publishers, Inc.

- European Drones Outlook Study, SESAR JU, Nov. 2016.

- ED-267 Operational Services & Environment Description (OSED) for Detect & Avoid in Very Low-level operations, European Organisation for Civil Aviation Equipment (EUROCAE).

- Study on the societal acceptance of Urban Air Mobility in Europe, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), 2021.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947 of 24 May 2019 on the rules and procedures for the operation of unmanned aircraft.

- Easy Access Rules for Unmanned Aircraft Systems, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), July 2024.

- EASA concept for regulation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) operations in the ‘certified’ category and Urban Air Mobility - Issue 3.0, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), 2021.

- Concept of Use for the Airborne Collision Avoidance System Xu for Smaller UAS (ACAS sXu), Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Version 2, 2020.

- Global Air Traffic Management Operational Concept, International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), 1st Edition, 2005.

- DO-396 Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Airborne Collision Avoidance System sXu (ACAS sXu), Radiotechnical Commission for Aeronautics (RTCA).

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/666 of 22 April 2021 amending Regulation (EU) No 923/2012 as regards requirements for manned aviation operating in U-space airspace.

- RTCA Paper No. 261-22/PMC-2336, available at https://www.rtca.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/SC-147-TOR-Rev-20-Approved-2022-09-15-1.pdf (retrieved on March 17th 2025). Radiotechnical Commission for Aeronautics (RTCA).

- Unmanned Aircraft Systems Traffic Management (UTM) – A Common Framework with Core Principles for Global Harmonization, the International Civil Aviation Organisation, Ed. 4, 2023.

- UTM Concept of Operations, v2.0, Federal Aviation Administration, v2.0, 2020.

- RPAS Traffic Management (RTM) System: Concept of Operations Version 1.1, NavCanada 2023.

- U-space ConOps and architecture, Ed. 4.0, CORUS-XUAM project, 2023.

- European ATM Master Plan, Edition 2020, SESAR Joint Undertaking.

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/945 of 12 March 2019 on unmanned aircraft systems and on third-country operators of unmanned aircraft systems.

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/1058 of 27 April 2020 amending Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/945 as regards the introduction of two new unmanned aircraft systems classes.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/664 of 22 April 2021 on a regulatory framework for the U-space.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/665 of 22 April 2021amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/373 as regards requirements for providers of air traffic management/air navigation services and other air traffic management network functions in the U-space airspace designated in controlled airspace.

- Easy Access Rules for U-space, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), May 2024.

- European ATM Master Plan, Edition 2025, SESAR Joint Undertaking.

- SPATIO website https://research.dblue.it/spatio/ (retrieved on March 17th, 2025).

- DO-366 Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Air-to-Air Radar for Traffic.

- Surveillance, Radiotechnical Commission for Aeronautics (RTCA), 2020.

- EUROCAE ED-275 - Minimum Operational Performance Standard (MOPS) for ACAS Xu, European Organisation for Civil Aviation Equipment (EUROCAE).

- Moses, M. J. Rutherford and K. P. Valavanis, "Radar-based detection and identification for miniature air vehicles," 2011 IEEE International Conference on Control Applications (CCA), Denver, CO, USA, 2011, pp. [CrossRef]

- N. Iwakiri, N. Hashimoto, T. Kobayashi, "Performance Analysis of Ultra-Wideband Channel for Short-Range Monopulse Radar at Ka-Band", Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, vol. 2012, Article ID 710752, 9 pages, 2012. [CrossRef]

- G. Fasano, D. Accado, A. Moccia and D. Moroney, "Sense and avoid for unmanned aircraft systems," in IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, vol. 31, no. 11, pp. 82-110, November 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Hägelen, R. Jetten, R. Kulke, C. Ben and M. Krüger, "Monopulse Radar for Obstacle Detection and Autonomous Flight for Sea Rescue UAVs," 2018 19th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Bonn, Germany, 2018, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Á. D. de Quevedo, F. I. Urzaiz, J. G. Menoyo and A. A. López, "Drone Detection With X-Band Ubiquitous Radar," 2018 19th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Bonn, Germany, 2018, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Haider Al and David Johnson, A Modular Conformal Antenna Array for Wide-Beam SAR and DAA Radars, 2023 IEE International Radar Conference. [CrossRef]

- Zhen Wang, A. Sinha, P. Willett and Y. Bar-Shalom, "Angle estimation for two unresolved targets with monopulse radar," in IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 998-1019, July 2004. [CrossRef]

- Doc. 9924 Aeronautical Surveillance Manual, International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), 3rd Edition, 2020.

- F3442/F3442M-20 Standard Specification for Detect and Avoid System Performance Requirement, the American Society for Test and Materials (ASTM), May 1st, 2020.

- Weinert, A., Alvarez, L. Owen, M., and Zintak, B., Near Mid-Air Collision Analog for Drone Based on Unmitigated Collision Risk, AIAA Journal of Air Transport, 2022.

- https://www.rflambda.com/pdf/poweramplifier/RFLUPA18G26GF.pdf, retrieved on March 17th, 2025.

- https://www.analog.com/en/products/adf5904.html, retrieved on March 17th, 2025.

- V. Semkin et al, IEE Access, Vol. 8, pp. 48958-48969, 2020.

- R. Mahafza, Radar Systems Analysis and Desing using Matlab, Chapman and Hall, 2020.

- Merryl, I. Skolnik, Introduction to Radar Systems, MC Graw-Hill, 3rd Edition, 2000.

- Merryl, I. Skolnik (editor), Radar Handbook, Mc Graw-Hill, 3rd Edition, 2008.

- H. Meikle, Modern Radars, Artech House, 2nd Edition, 2008.

- M. Skolnic, Systems Aspects of Digital Beamforming Ubiquitous Radars, Naval Research Laboratory, 2002.

- Á. D. de Quevedo, F. I. Urzaiz, J. G. Menoyo and A. A. López, "Drone Detection With X-Band Ubiquitous Radar," 2018 19th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Bonn, Germany, 2018, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- https://www.3ds.com/es/products/simulia/cst-studio-suite, retrieved on March 17th, 2025.

- https://www.pcbway.com, retrieved on March 17th, 2025.

- https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/other/wp/2018-2020/annexes/h2020-wp1820-annex-g-trl_en.pdf, retrieved on March 18th, 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).