Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomimetic Scaffold Design

2.2. 3D Printing Set-Up

2.3. Micro-Tomographic Analysis

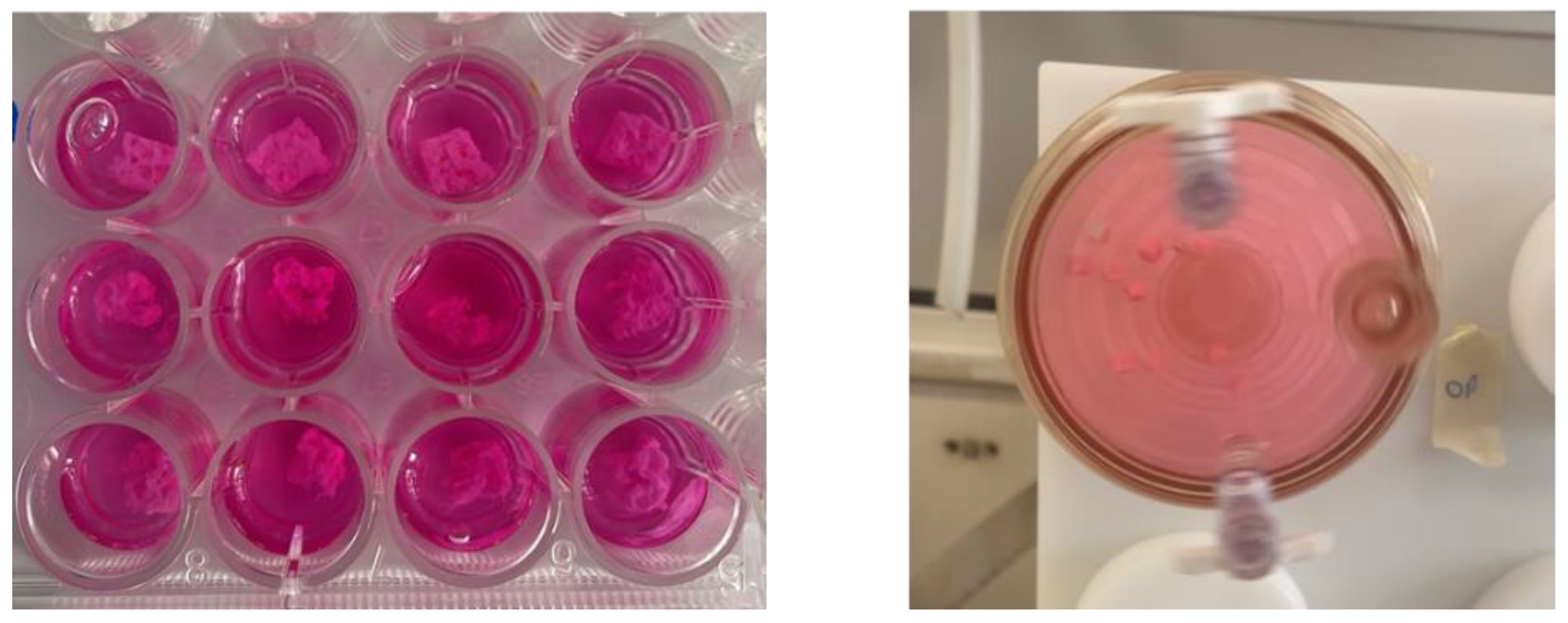

2.4. Cell Culture

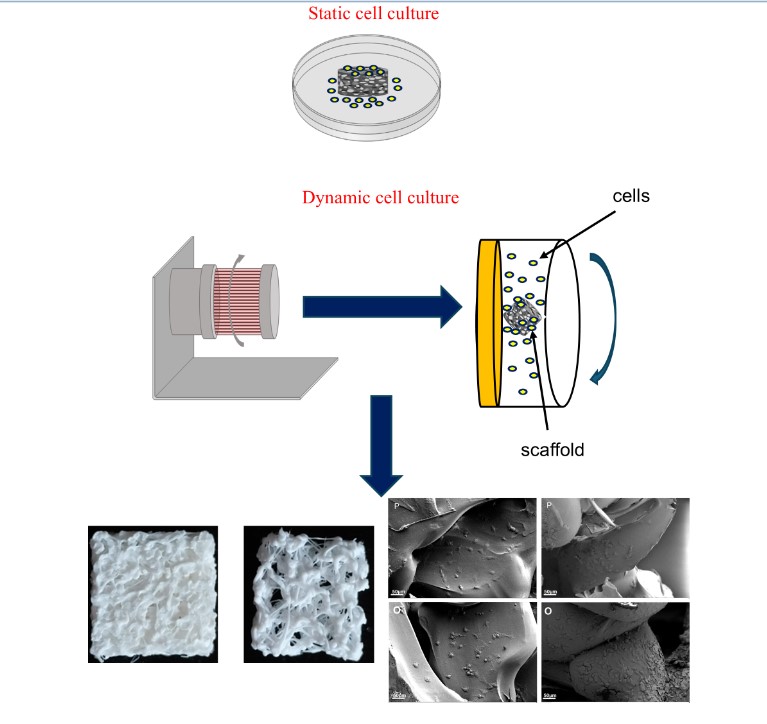

2.5. RCCS Bioreactor

2.6. Biological Assays

2.6.1. Cell Proliferation and Metabolic Activity Analysis

2.6.2. TNF-α Secretion Analysis

2.6.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Scaffold Assessment

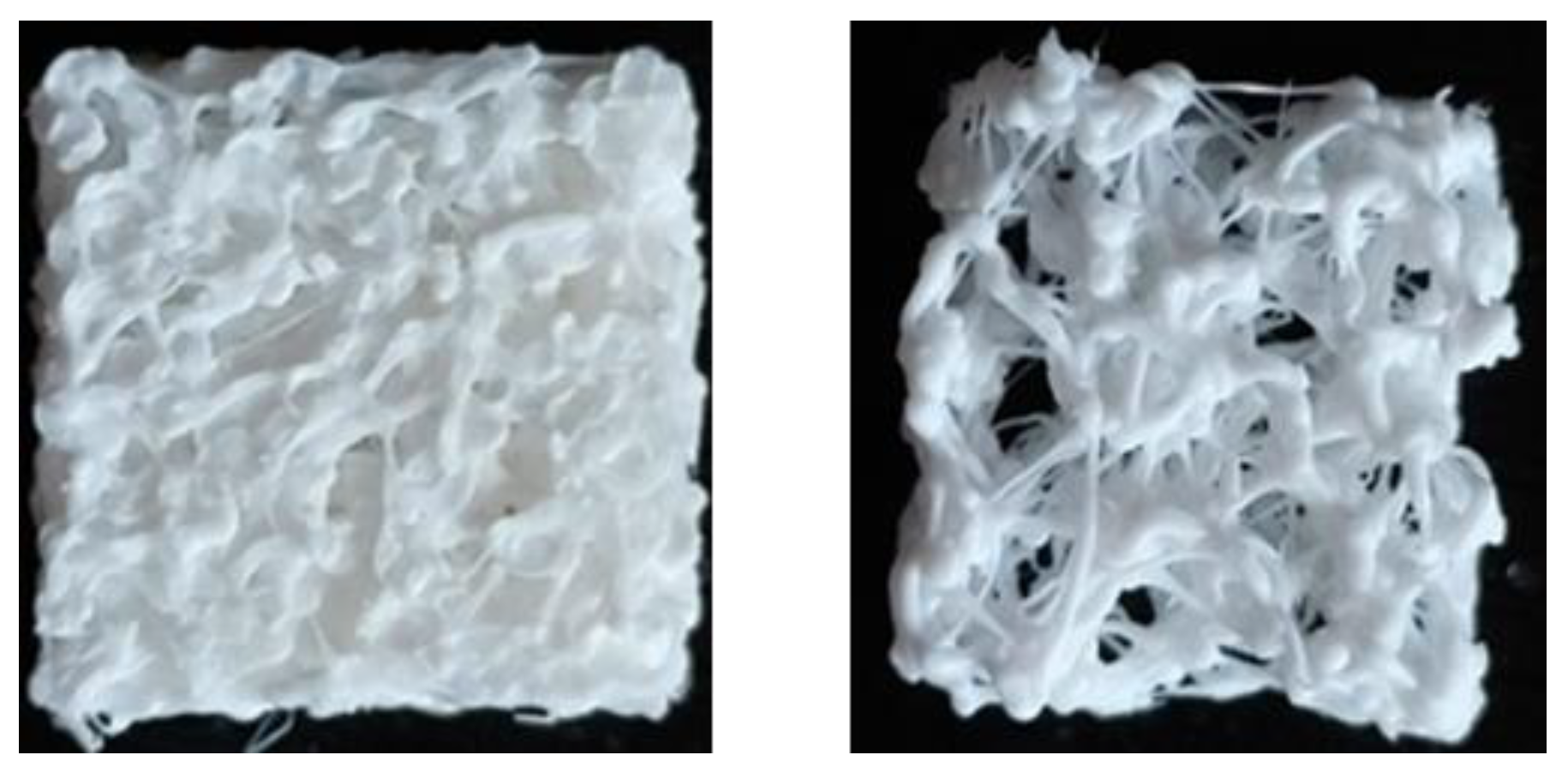

3.2. 3D Printed Scaffolds

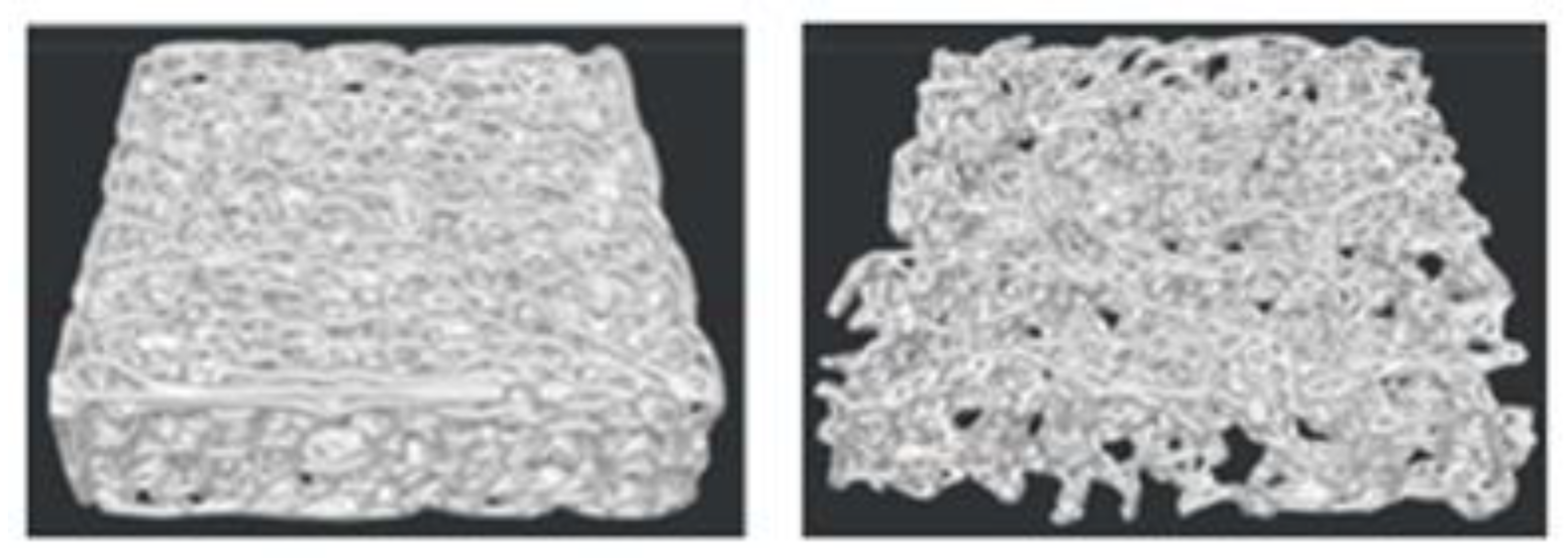

3.3. Morphometric Analysis

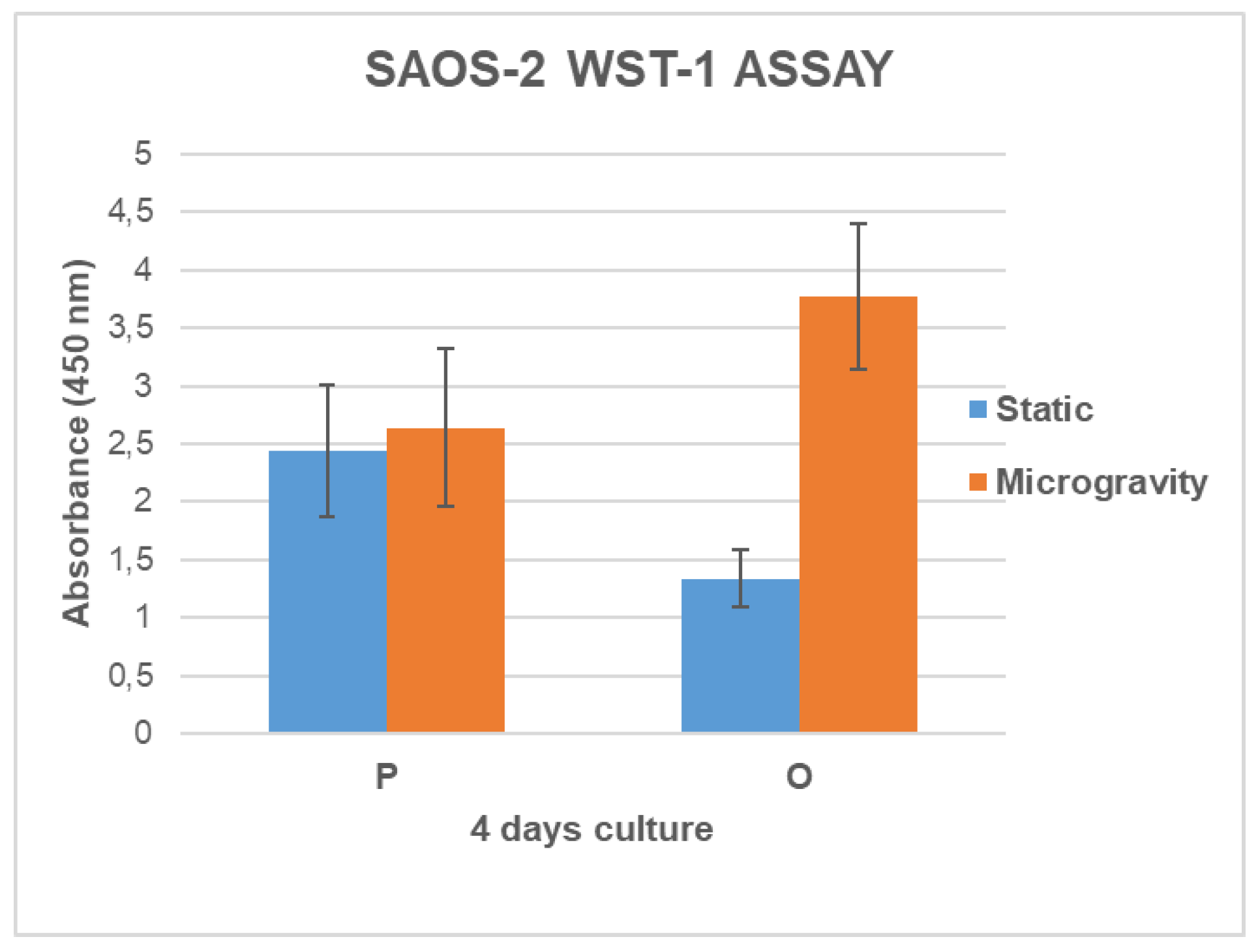

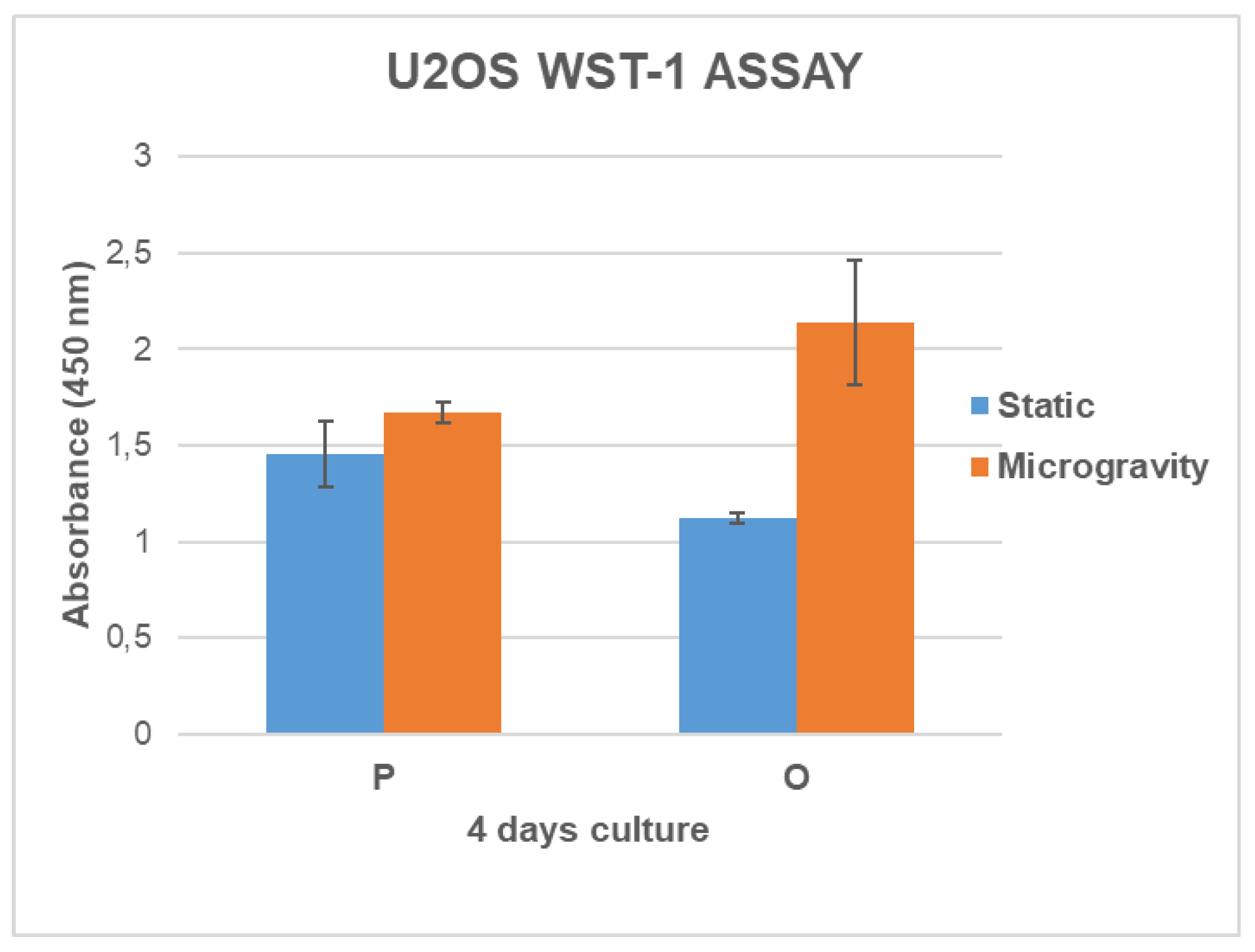

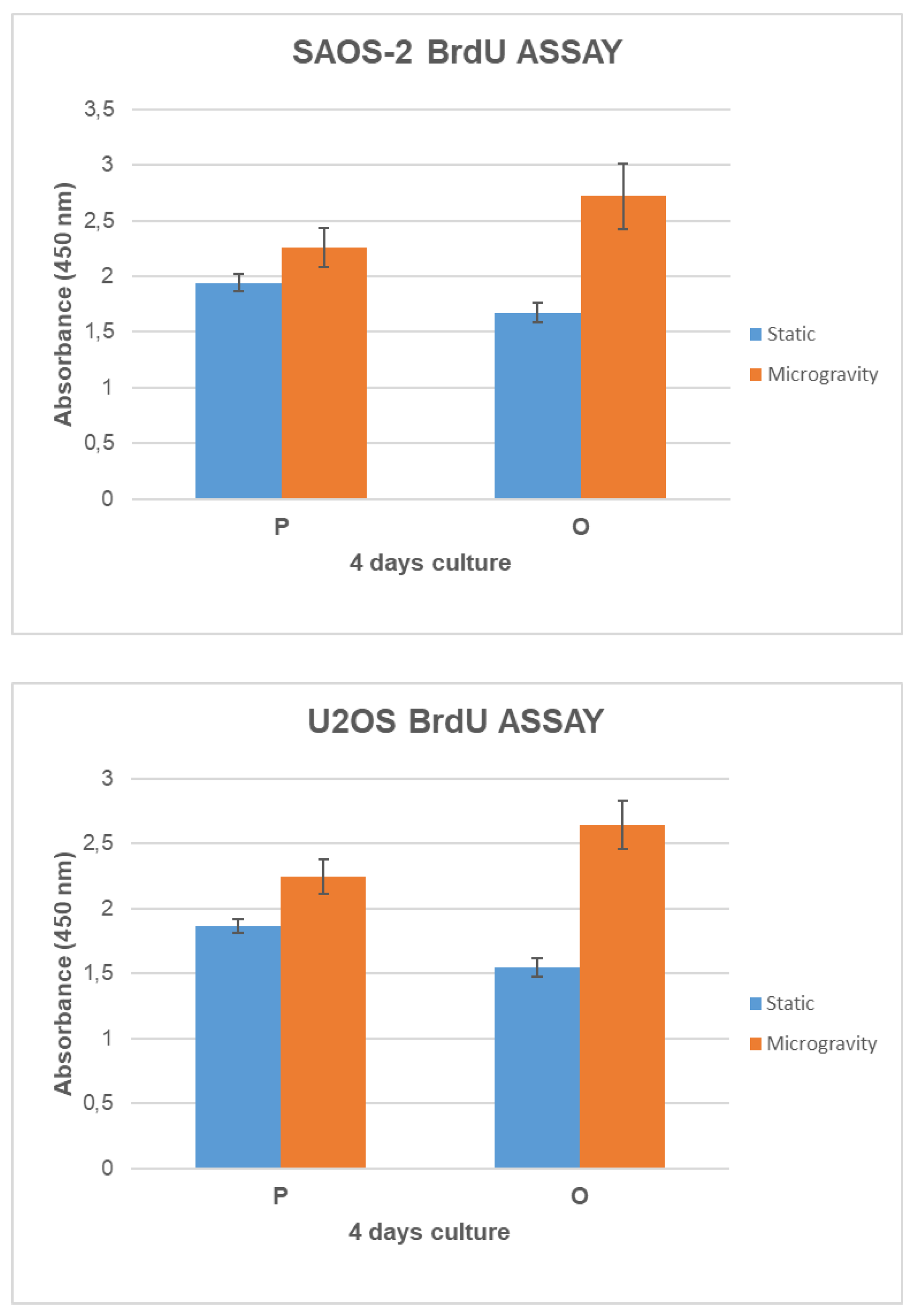

3.4. Cell Growth and Metabolic Activity Study in Microgravity Conditions

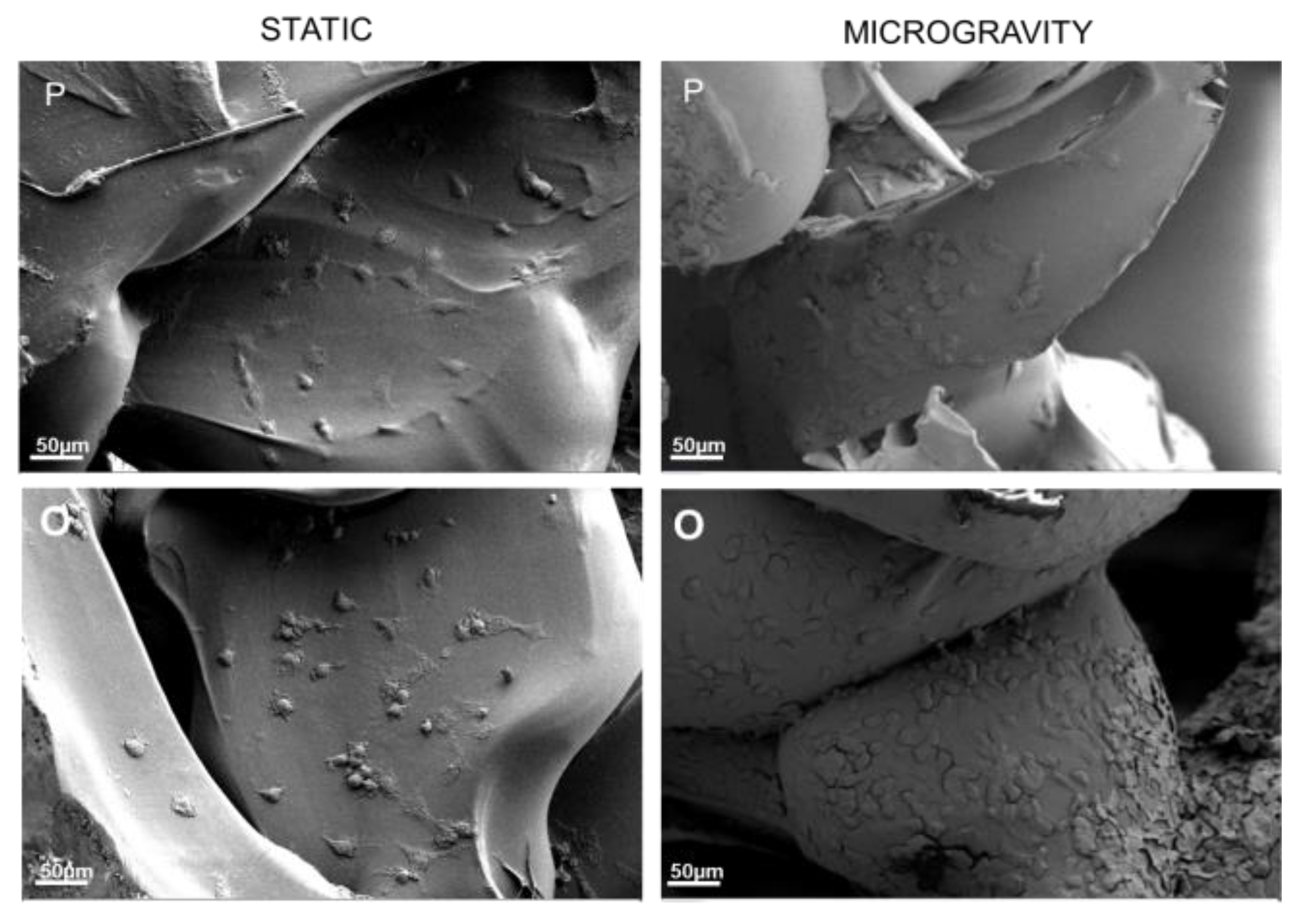

3.5. Cell Adhesion Study in Microgravity Conditions

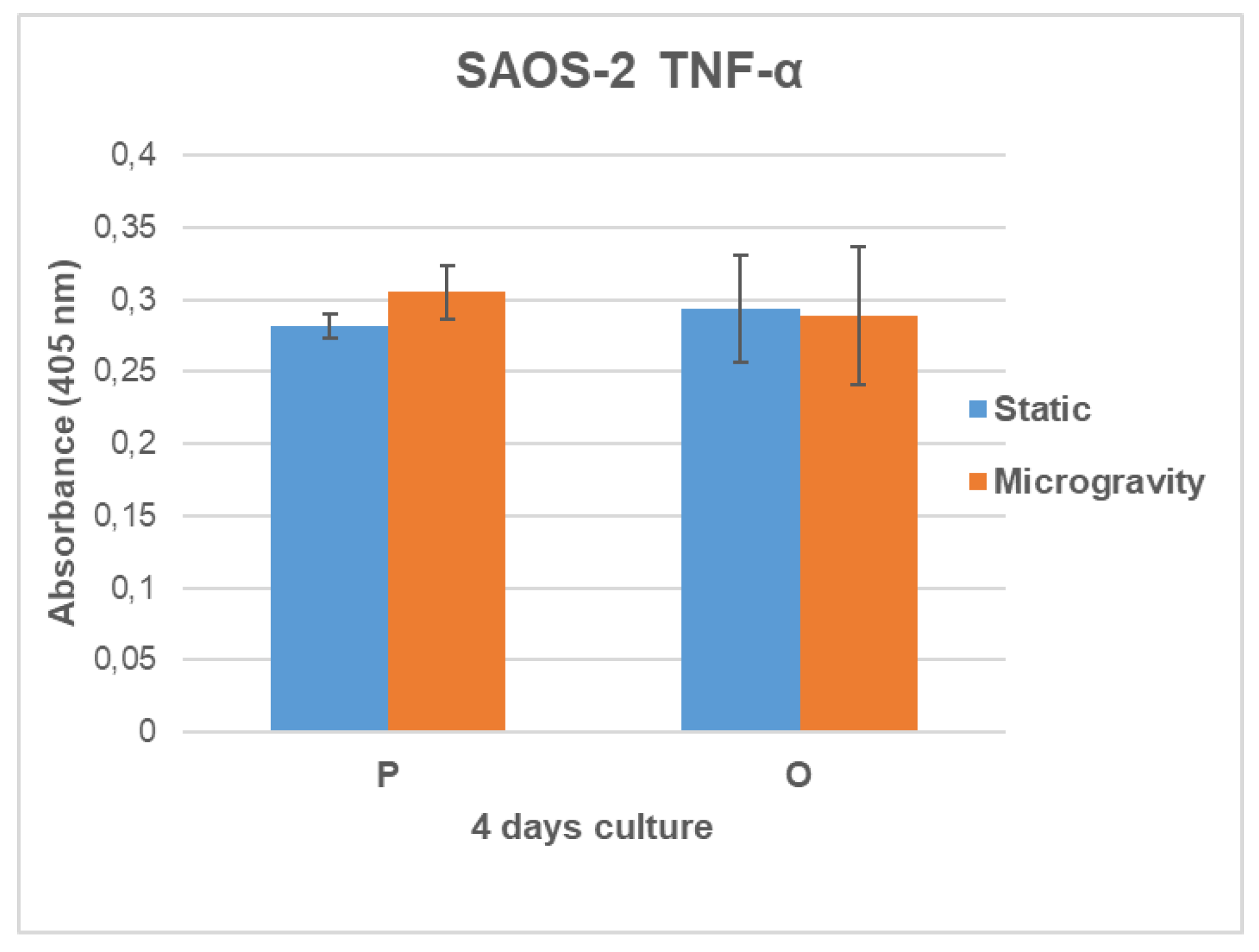

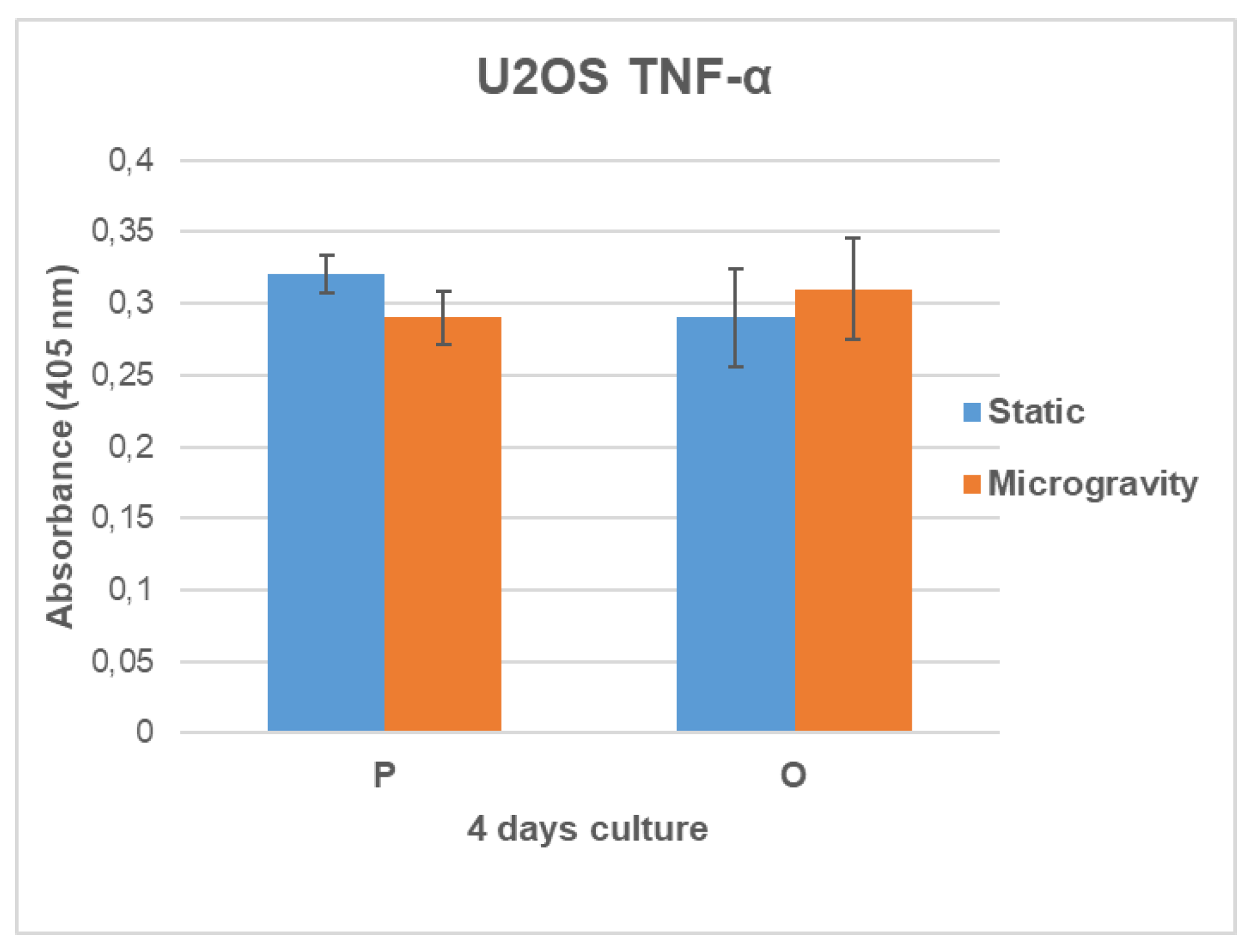

3.6. TNF-α Secretion Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Habanjar, O.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Caldefie-Chezet, F.; Delort, L. 3D Cell Culture Systems: Tumor Application, Advantages, and Disadvantages. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, C. Advances in 3D printing technology for preparing bone tissue engineering scaffolds from biodegradable materials. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2024, 12, 1483547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winarso, R.; Anggoro, P.W.; Ismail, R.; Jamari, J.; Bayuseno, A.P. Application of fused deposition modeling (FDM) on bone scaffold manufacturing process: A review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidaka, M.; Su, G.N.; Chen, J.K.; Mukaisho, K.; Hattori, T.; Yamamoto, G. Transplantation of engineered bone tissue using a rotary three-dimensional culture system. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2007, 43, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskey, A. Mineralization, Structure and Function of Bone. 2006; pp. 201–212.

- Weiner, S.; Wagner, H.D. The material bone: Structure mechanical function relations. Annu Rev Mater Sci 1998, 28, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, A.J.; Coutinho, O.P.; Reis, R.L. Bone tissue engineering: state of the art and future trends. Macromol Biosci 2004, 4, 743–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernikos, J.; Schneider, V.S. Space, gravity and the physiology of aging: parallel or convergent disciplines? A mini-review. Gerontology 2010, 56, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenobi, E.; Merco, M.; Mochi, F.; Ruspi, J.; Pecci, R.; Marchese, R.; Convertino, A.; Lisi, A.; Del Gaudio, C.; Ledda, M. Tailoring the Microarchitectures of 3D Printed Bone-like Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications. Bioengineering (Basel) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bray, T.J.P.; Hall-Craggs, M.A. Quantifying bone structure, micro-architecture, and pathophysiology with MRI. Clin Radiol 2018, 73, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, G.; Dalpozzi, A.; Ciapetti, G.; Lorusso, M.; Novara, C.; Cavallo, M.; Baldini, N.; Giorgis, F.; Fiorilli, S.; Vitale-Brovaron, C. Osteoporosis-related variations of trabecular bone properties of proximal human humeral heads at different scale lengths. J Mech Behav Biomed 2019, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarelli, T.E.; Fyhrie, D.P.; Schaffler, M.B.; Goldstein, S.A. Variations in three-dimensional cancellous bone architecture of the proximal femur in female hip fractures and in controls. J Bone Miner Res 2000, 15, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandino, C.; McErlain, D.D.; Schipilow, J.; Boyd, S.K. Mechanical stimuli of trabecular bone in osteoporosis: A numerical simulation by finite element analysis of microarchitecture. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2017, 66, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrelli, D.; Abrami, M.; Pelizzo, P.; Formentin, C.; Ratti, C.; Turco, G.; Grassi, M.; Canton, G.; Grassi, G.; Murena, L. Trabecular bone porosity and pore size distribution in osteoporotic patients - A low field nuclear magnetic resonance and microcomputed tomography investigation. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2022, 125, 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveen, J.; Perilli, E.; Zahrooni, S.; Jaarsma, R.L.; Doornberg, J.N.; Bain, G.I. Three-dimensional cortical and trabecular bone microstructure of the proximal ulna. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2023, 143, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, A.C.; Pereira, M.F.C.; Maurício, A.; Amaral, P.; Rosa, L.G.; Lopes, A.; Rodrigues, A.; Caetano-Lopes, J.; Vidal, B.; Monteiro, J.; et al. Micro-computed tomography and compressive characterization of trabecular bone. Colloid Surface A 2013, 438, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikodem, A. Correlations between structural and mechanical properties of human trabecular femur bone. Acta Bioeng Biomech 2012, 14, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozan, F.; Pekedis, M.; Koyuncu, S.; Altay, T.; Yildiz, H.; Kayali, C. Micro-computed tomography and mechanical evaluation of trabecular bone structure in osteopenic and osteoporotic fractures. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2017, 25, 2309499017692718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, M.; Wijenayaka, A.R.; Kumarasinghe, D.D.; Ormsby, R.T.; Evdokiou, A.; Findlay, D.M.; Atkins, G.J. SaOS2 Osteosarcoma Cells as an In Vitro Model for Studying the Transition of Human Osteoblasts to Osteocytes. Calcified Tissue Int 2014, 95, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekanska, E.M.; Stoddart, M.J.; Richards, R.G.; Hayes, J.S. In Search of an Osteoblast Cell Model for Research. Eur Cells Mater 2012, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mornet, E.; Stura, E.; Lia-Baldini, A.S.; Stigbrand, T.; Ménez, A.; Le Du, M.H. Structural evidence for a functional role of human tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase in bone mineralization. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 31171–31178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimo, H.; Shimada, T. Effects of phosphates on the expression of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase gene and phosphate-regulating genes in short-term cultures of human osteosarcoma cell lines. Mol Cell Biochem 2006, 282, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Q.; Zhou, G.; Junka, R.; Chang, N.X.; Anwar, A.; Wang, H.Y.; Yu, X.J. Fabrication of polylactic acid (PLA)-based porous scaffold through the combination of traditional bio-fabrication and 3D printing technology for bone regeneration. Colloid Surface B 2021, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aishwarya, P.; Agrawal, G.; Sally, J.; Ravi, M. Dynamic three-dimensional cell-culture systems for enhanced applications. Curr Sci India 2022, 122, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerath, E. Effects of microgravity on bone and calcium homeostasis. Adv Space Res 1998, 21, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Jones, J.; Shapiro, J.; Lang, T.; Shackelford, L.; Smith, S.M.; Evans, H.; Spector, E.; Ploutz-Snyder, R.; et al. Bisphosphonates as a supplement to exercise to protect bone during long-duration spaceflight. Osteoporosis Int 2013, 24, 2105–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, K.F.; Cheah, C.M.; Chua, C.K. Solid freeform fabrication of three-dimensional scaffolds for engineering replacement tissues and organs. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 2363–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, D.; Kaduri, M.; Poley, M.; Adir, O.; Krinsky, N.; Shainsky-Roitman, J.; Schroeder, A. Biocompatibility, biodegradation and excretion of polylactic acid (PLA) in medical implants and theranostic systems. Chem Eng J 2018, 340, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, M.; Techy, G.B.; Saroufeem, R.; Yazan, O.; Narayan, K.S.; Goodwin, T.J.; Spaulding, G.F. Three-dimensional growth patterns of various human tumor cell lines in simulated microgravity of a NASA bioreactor. In Vitro Cell Dev-An 1997, 33, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xuan, K.; He, D.; Deng, T.; Tang, L.; Lu, W.; Duan, Y. Establishment of three-dimensional tissue-engineered bone constructs under microgravity-simulated conditions. Artif Organs 2010, 34, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasal, R.M.; Janorkar, A.V.; Hirt, D.E. Poly(lactic acid) modifications. Prog Polym Sci 2010, 35, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SAMPLE | PD (µm) | PS (µm) | TT (µm) | TS (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 700 | 700 | 200 | 600 |

| O | 800 | 500 | 150 | 800 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).