1. Introduction

The citrus industry is of paramount importance in the Oriental region. Nowadays, with the globalization of trade and biotic and abiotic constraints, Morocco needs to be a safe bet in the agricultural sector.

Citrus fruits have a specialized berry form (

Hesperdium) resulting from a single ovary. In addition to the Citrus genus, there are five other genera of this fruit type:

Poncirus (trifoliate orange),

Fortunella (the kumquat which is eaten as is with its skin),

Microcitrus, Eremocitrus, and

Clymenia subfamily Aurentioidae and all belonging to the

Rutaceae family. Citrus fruits are almost all native to China and India, where they were known 4200 years ago and cultivated 3000 years ago [

1].

Citrus production provides Morocco's exports with substantial added value, and consequently a source of foreign currency earnings and a reputation for quality. Improving cultivation and infrastructure is a priority for preserving this heritage.

Considerable efforts are being made to counter phytosanitary and environmental problems in order to enhance the long-term value of the sector.

The aim of this study is to provide information on the varieties of clementine grown in the Lower Moulouya perimeter, in order to enhance the value of the Berkane clementine compared with other varieties. The study of citrus-growing phytosanitary problems in the Lower Moulouya irrigated perimeter represents an approach to citrus development, especially at varietal level.

The current total area under citrus is 118,000 ha, of which 92,000 ha is productive. The average annual increase is 5285 Ha/year. Thus, the productive area of small fruits has increased by 31%, while that of oranges has risen by 24% (Ministry of Agriculture and Maritime Fisheries [

2]. Morocco is the 8

th largest exporter of citrus fruits, with the aim of doubling its exports by 2020 following a restructuring of the sector.

Citrus trees in Morocco, as in all other producing countries, are subject to various diseases and disorders, the severity of which varies in proportion to the infection concerned. In order to combat these, systematic research into all citrus disorders has been carried out for several years, resulting in a global assessment. This may seem a dauntingtask, particularly where viral diseases are concerned. However, it would be wrong to conclude that the health situation is worse in Morocco than in other Mediterranean countries.

After viral diseases, fungal diseases are the most serious plant pests affecting citrus

trees in Morocco. Phytophthora gum disease accounts for most of this danger, with the rest of the fungal diseases not reaching the same level of severity. The Mediterranean fruit fly or ceratitis (

Ceratitis capitata) is also often a source of direct damage to many citrus species and varieties [

3].

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of Berkane Clementines

Organoleptic characteristics are shown in

Table 1. In fact, 2 to 4 samples of each clementine variety were studied. The four varieties showed weights and sizes that differed from one variety to another. Fruit size is determined by measuring the diameter of the equatorial section of the fruit. Fruits are classified into three size categories: (Sizes: C1 > 78 mm; 68 mm < C2 < 78 mm; C3 < 68 mm) [

4].

2.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

2.2.1. Sugar in Juice

Our results for the nova variety are mainly for C2. The same applies to the Berkane clementine and the Nour variety. Class C2 would be for the ortanique variety. The latter has the highest weight.

The pH is very acidic, between 2.7 and 3.5. Juice volume gives a general idea of juice yield, which also differs from variety to variety and even within the same variety. Peel is an essential parameter for citrus fruit. It is generally between 2 and 5 mm.

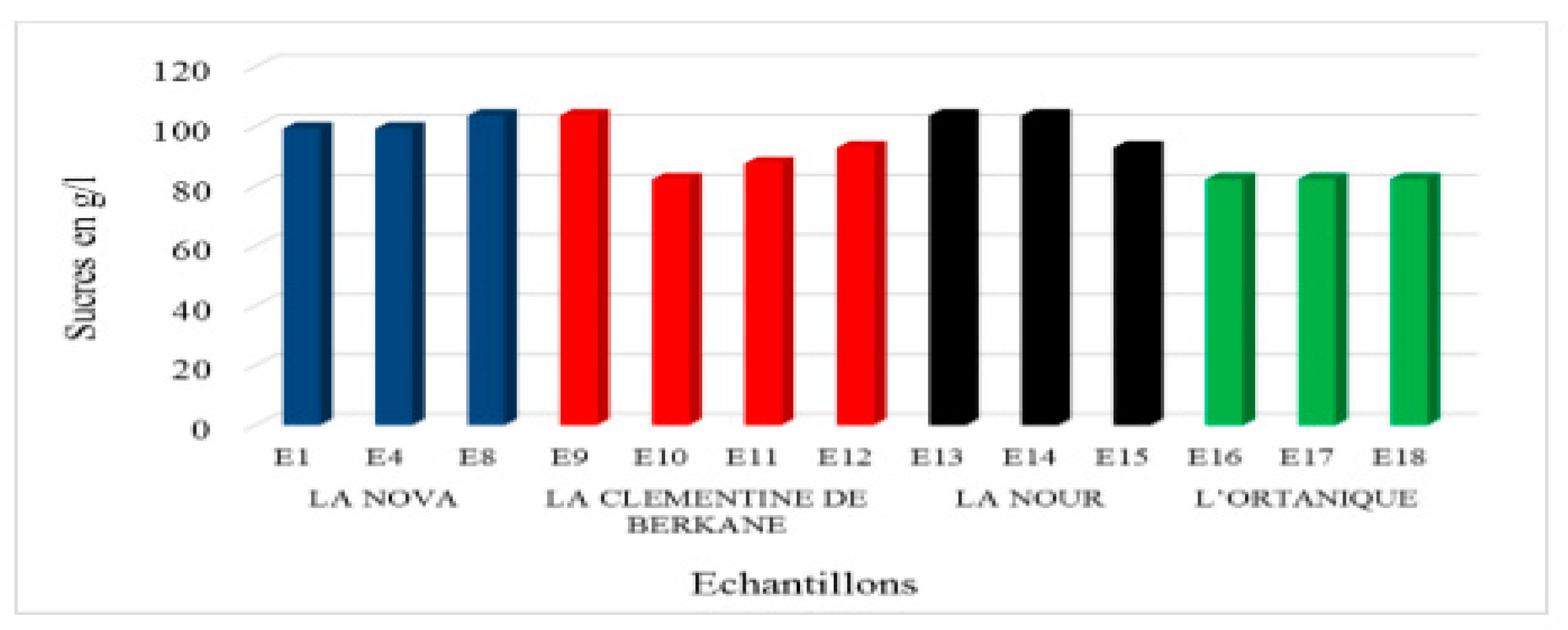

Measurement of sucrose content by refractometry shows that ortanique has the lowest content (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) compared with the other varieties. The other varieties (Nova and Nour) have intermediate values. The evolution of alcohol (alcoholic degrees) (data by refractometer catalog) and sucrose show the same trend as above.

Figure 1.

Total sugar content by refractometer of clementine and mandarin samples.

Figure 1.

Total sugar content by refractometer of clementine and mandarin samples.

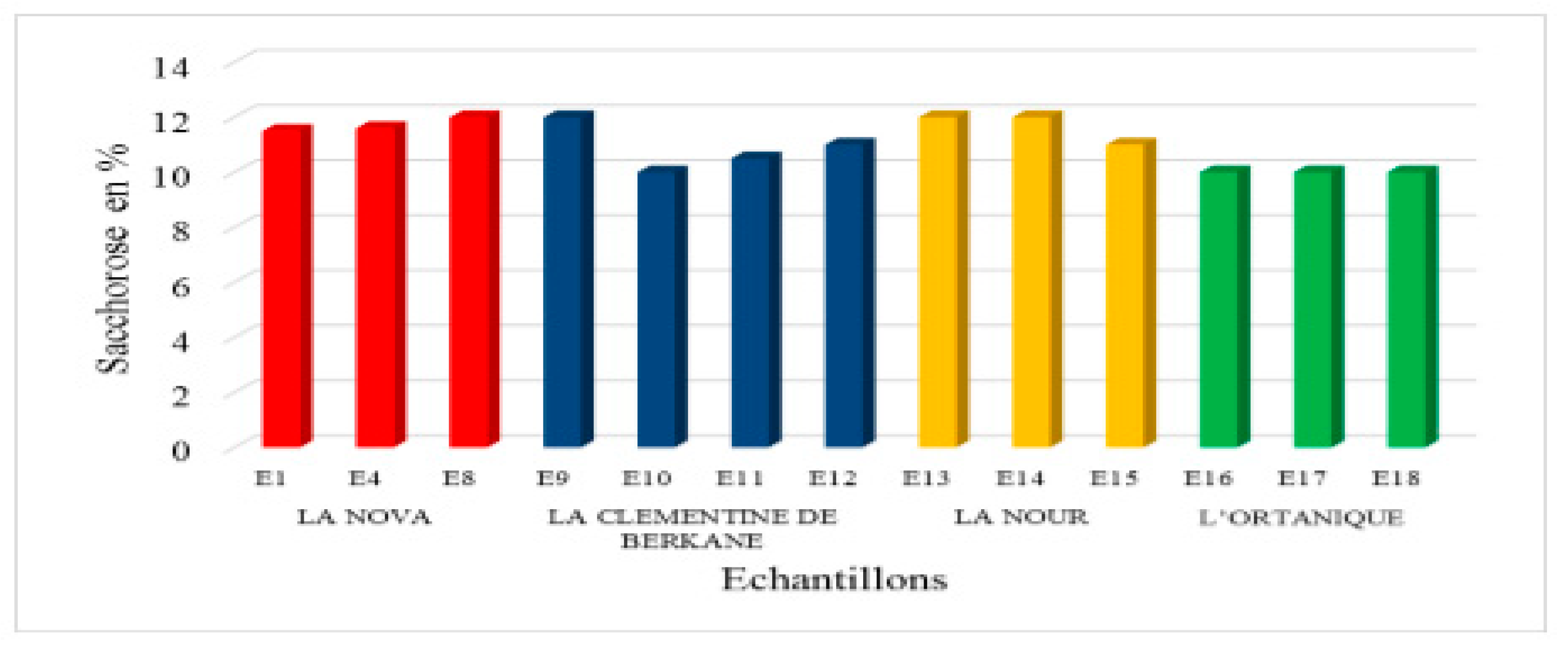

Figure 2.

Sugar content of juice by refractometer.

Figure 2.

Sugar content of juice by refractometer.

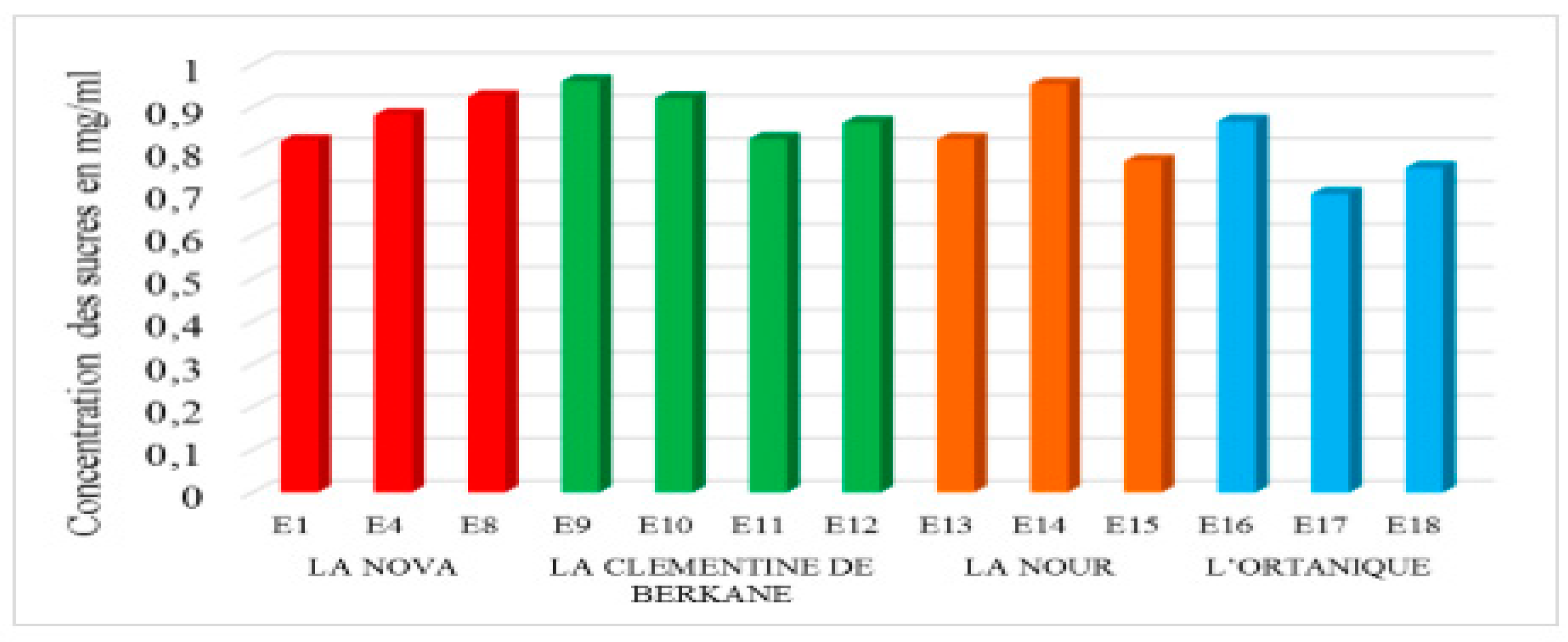

Figure 3.

Concentration of sugars by titration.

Figure 3.

Concentration of sugars by titration.

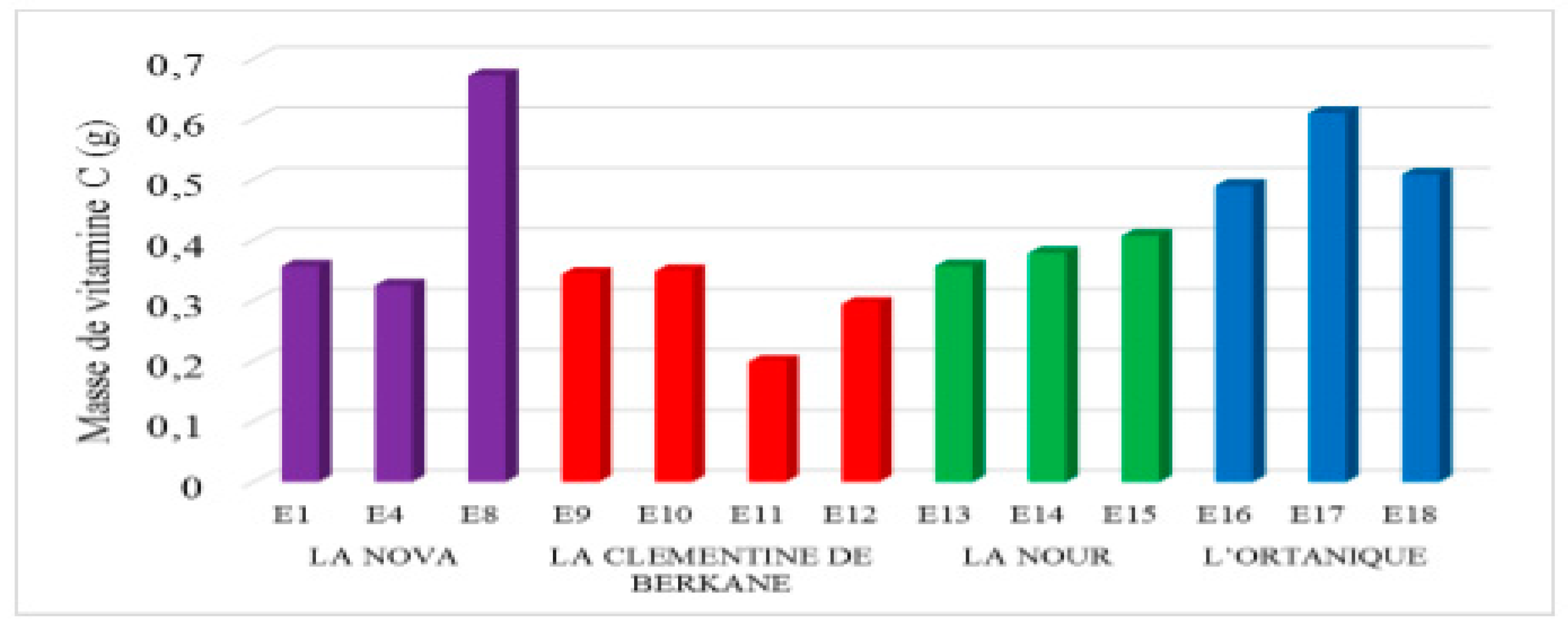

2.2.2. Vitamin C in Juice

Comparison of samples from Berkane citrus varieties shows a high vitamin C content for the ortanic variety. The Berkane clementine has the lowest value (figure 4). Vitamin C content is an essential parameter for the quality of citrus fruit, especially for export and secondary processing.

Figure 4.

Vitamin C content.

Figure 4.

Vitamin C content.

Sugar content is 0.65-0.95 mg/ml (DNS) and 80-100 g/l (IR) in all varieties (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). This parameter is also an indicator of citrus fruit quality for fresh consumption, secondary processing and post-harvest preservation.

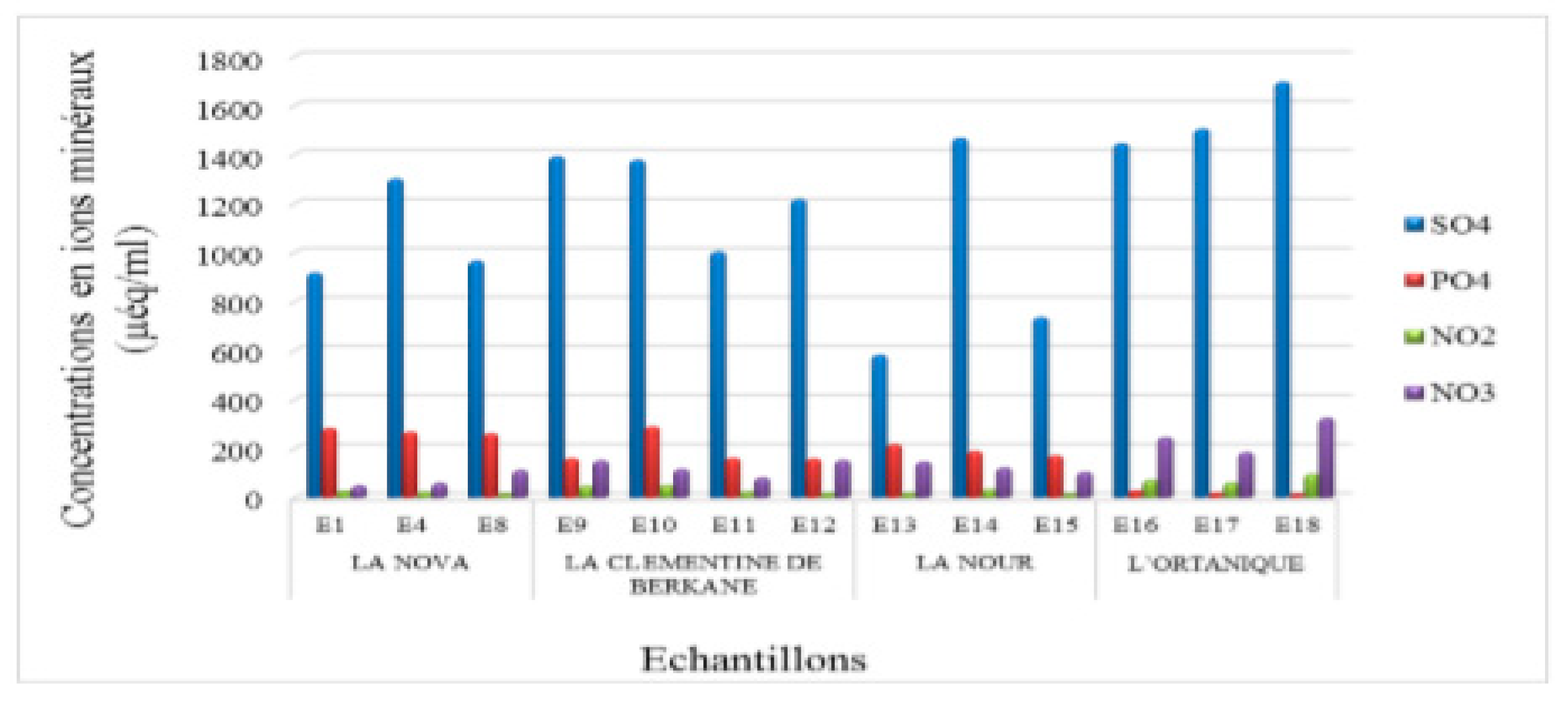

2.2.3. Mineral Ion Content in Juice

The mineral elements are: sulfates (S0

42- ), phosphates (P0

43- ), nitrates (N0

2- ) and nitrites (N0

3- ).

Figure 5 shows the most representative mineral elements in fertilizers enriching orchard soil.

In fact, this richness is a very important organoleptic parameter, since on the one hand it can distinguish quality, but on the other it can also show unpleasant internal pollution due mainly to irrigation water and/or the use of undesirable products leaving harmful internal residues such as insecticides, herbicides and fungicides.

The ionic distribution of citrus fruit content in juices shows considerable varietal diversity, and is also likely to reflect the geographical location of the orchard of origin.

In fact, this could be a highly-developed area of research for adding value to citrus

products in direct relation to the immediate orchard environment. We note that sulfates

and phosphates are the most representative. Nitrate and nitrite levels are recorded in the

juice of the ortanique variety, which may give a qualitative overview of the production area. E: random samples

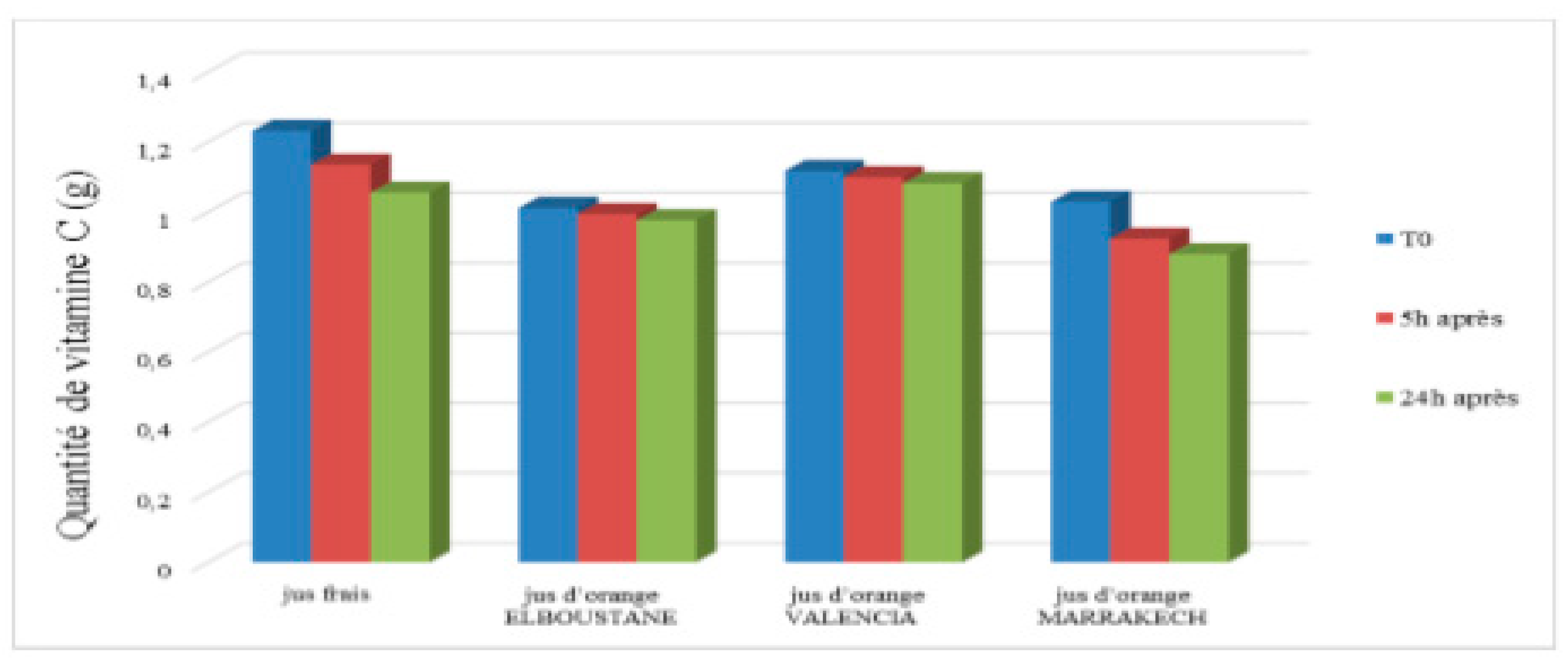

2.2.4. Comparison of Vitamin C Content in Fresh and Marketed Juices

The results in

Figure 6 show a slightly higher vitamin C content in the fresh juice sample, followed by the VALENCIA orange juice sample. There is also a very slight decrease over time, to around 10% after 24 hours.

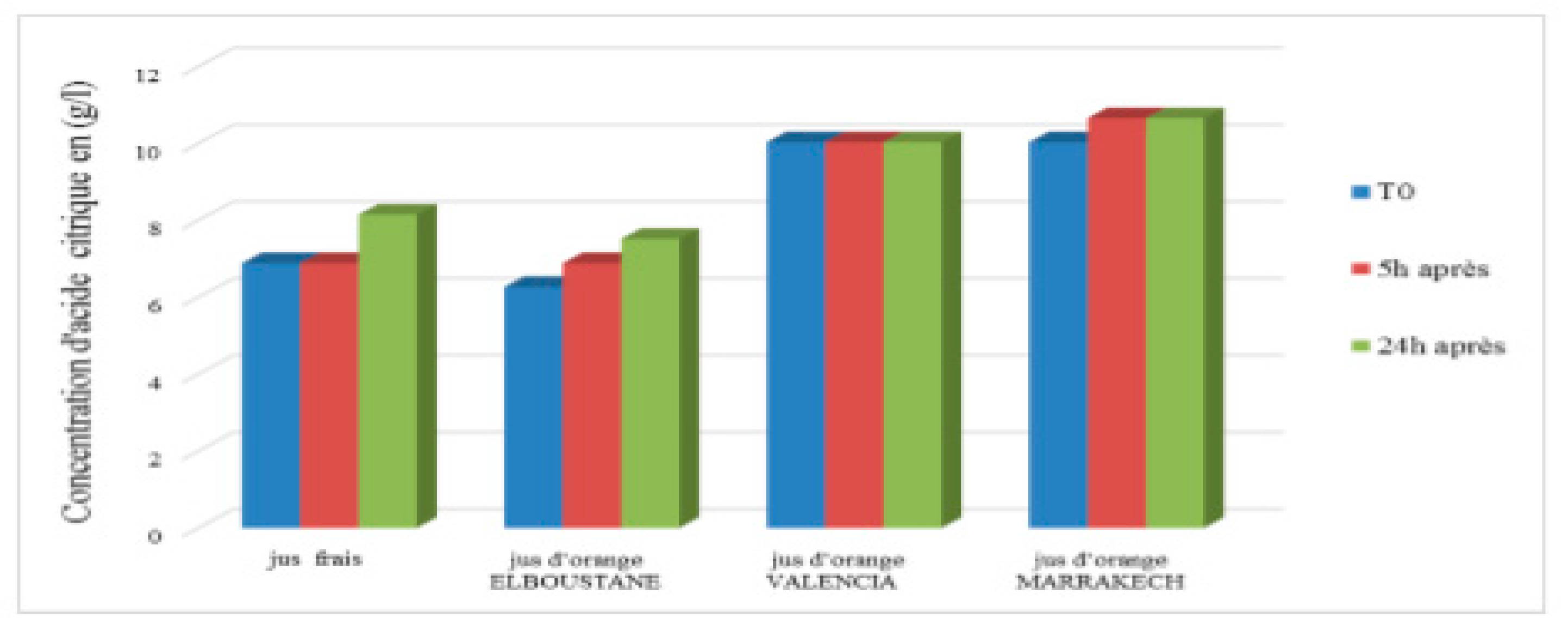

2.2.5. Comparison of Citric Acid Content in Fresh and Marketed Juices

Citric acid levels show (

Figure 7) an increase in MARRAKECH orange juice. The VALENCIA orange juice sample maintains the same level regardless of the period after opening, while the fresh juice shows an increase after 24 hours of pressing.

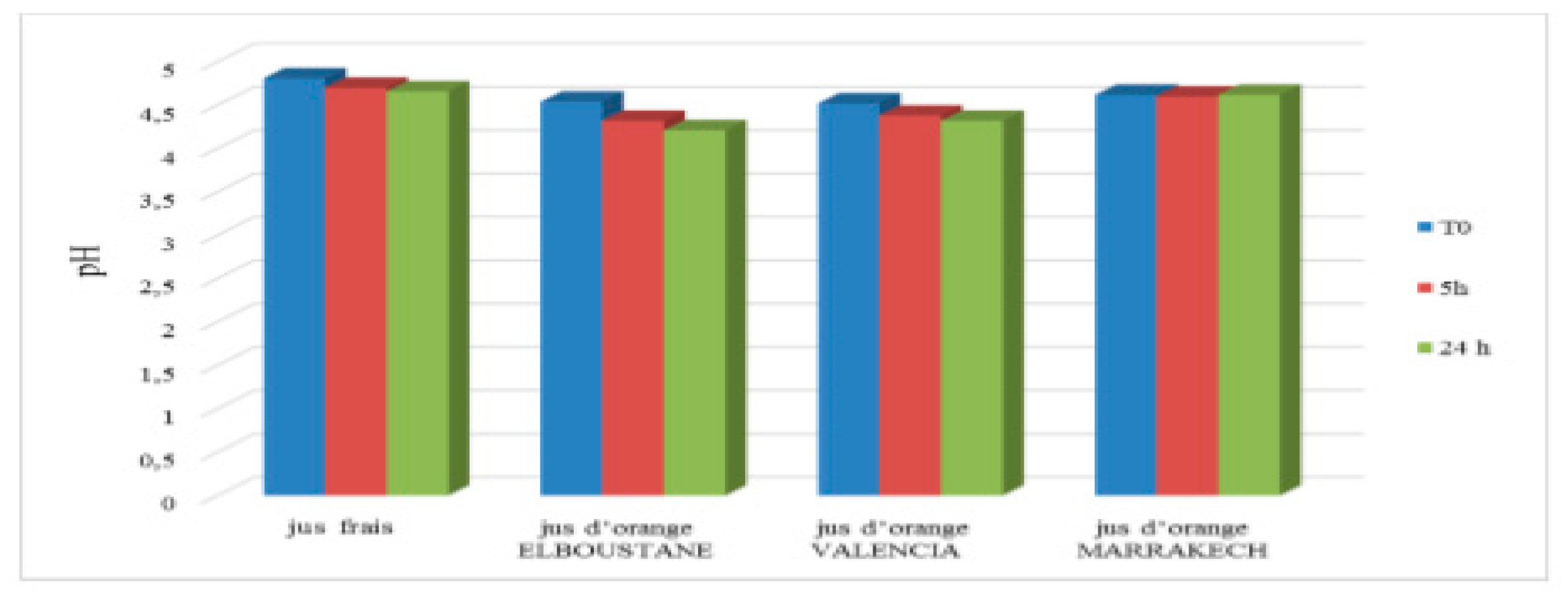

2.2.6. Comparison of pH Levels of Fresh and Marketed Juices

Sample pH values (

Figure 8) ranged from 4.2 to 4.8, with a slightly acidic pH in the ELBOUSTANE.

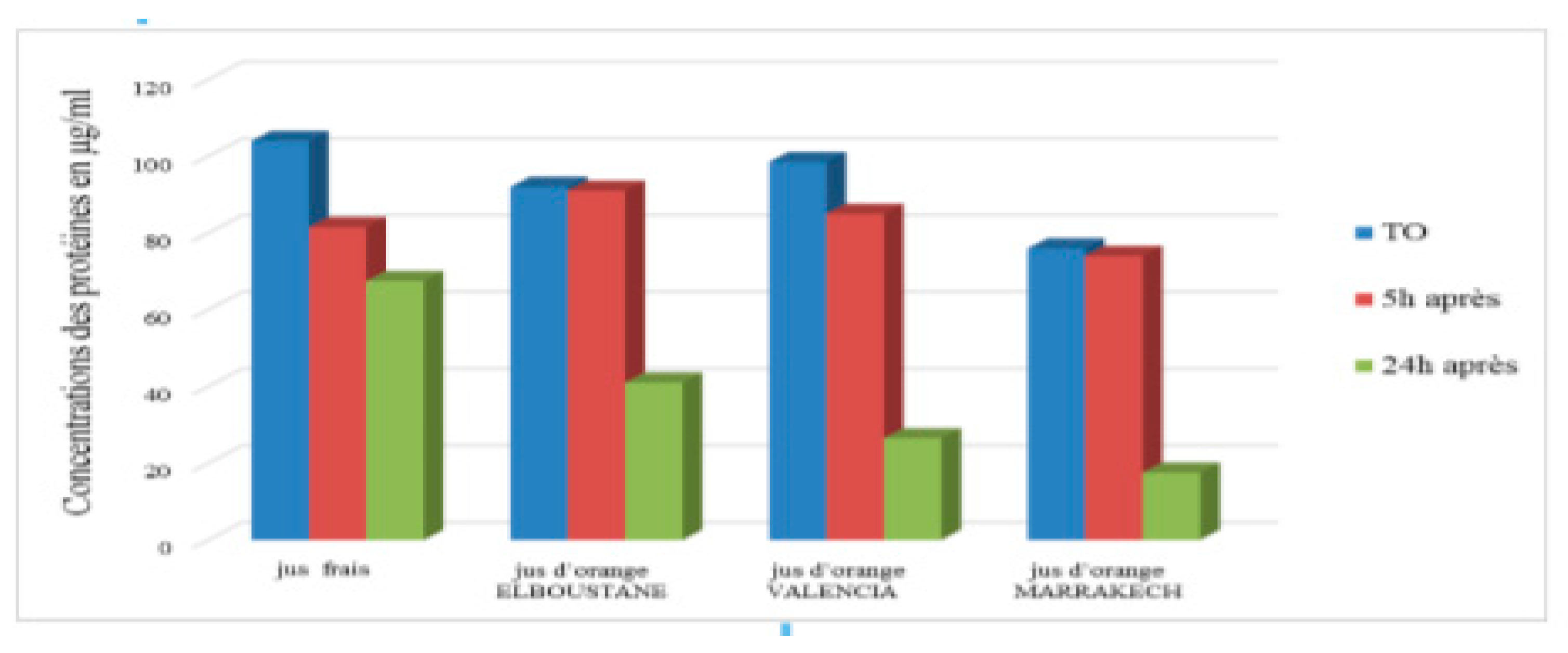

2.2.7. Comparison of Protein Content in Fresh and Marketed Juices

Protein content is slightly higher in fresh juice (

Figure 9). Protein levels fall progressively within the same variety. Protein levels fall sharply in other orange juices marketed after 24 hours of opening, exceeding 50% and even 75% in the MARRAKECH orange juice sample.

3. Discussion

Fruit juices are obtained from fruit by mechanical action (pressing), although a wide variety of other processes are available to extract the juice. The nature of the fruit is an important factor in the choice of process and the different techniques that can be applied to citrus or small-seeded fruits (lemons, apples, pears, raspberries, etc..).

Fruits used to make juice contain a wide variety of constituents, although sugars and acids generally predominate [

5]. After a conversion of our calibers we can conclude that the average diameter of the fruits studied varies between different citrus varieties which range from 27.34 mm of the Thaamrount variety, to 81.59 mm (orange variety Thomson) and 71.59 mm (orange variety Hamlin), [

6]. The overall average of our results is 57.88 mm. The thaamrount variety is lower than all our varieties and the hamlin variety is between the nour and ortanique varieties.

The average is about the same as for the nova variety. The specific quality of Berkane clementines on the average size with an equatorial diameter between 46 and 65 mm which places our results in this equatorial diameter [

7].

According to Séminaire International Antalya 10-14 Octobre 2012 berkane clementines have a sugar content: 7.5 – 14 degrees Brix, which are well below our studied levels. According to our results, the four varieties studied showed that the weight of the nova ranges from 77.73g to 174.93g; the Berkane clementine is from 55.79 to 101.8g; the nour is from 95.58g to 112.49g and finally the ortanique is between 168.84g to 189.97g which has the important weights. They are higher than the average fruit weight of the Thaghanimth variety which is 27.24g and lower than the Thomson variety orange which is 249.44g [

6]. According to the legal definition, a fruit juice is the natural product obtained by mechanical process from healthy, ripe fresh fruit, which has not undergone fermentation.

Orange juice consists largely of water (80- 90%), simple carbohydrates (total sugars such as glucose, fructose and sucrose) and polysaccharides (mainly pectic sustances, cellulose and hemicellulose).

Pectic substances are responsible for the juice's colloidal nature. The organic acids present in orange juice are mainly citric, isocitric and malic acids. Citric acid is responsible for the acidity of orange juice. The color of the juice is due to a complex mixture of carotenoids (mainly lutein, with zeaxanthin, cryptoxanthin and β-carotene in the minority) [

8,

9].

The ideal pH is between 5.5 and 7.5, while our results are all lower [

10,

11]. The average epidermis thickness of the different fruit varieties oscillates around an overall average of 2.44 mm, 0.34 mm (apricot variety Bulida) to 4.45 mm (orange variety Double fine and lemon variety Quatre saisons) and our results for bark thickness are similar to these data, which lies between 2 and 5 mm [

6]

The aromatic profile of orange juice varies according to variety and juice extraction

method. Indeed, during extraction, a greater or lesser quantity of essential oils from the flavored fruit may be incorporated into the juice. The delicate, fresh flavor of orange juice is easily modified by heat during processing and storage.

The juice undergoes compositional changes that invariably cause an alteration in the original flavor and aroma of the fresh juice. The shape of the fruit tends to be round to flattened. [

12,

13] have shown that fruit appearance varies with soil or cultural factors [

14], and with rootstock [

15].

Ascorbic acid in the body aids iron absorption from the intestines. It is required for connective metabolism, in particular scar tissue, bones and teeth [

16,

17]. It is needed as an anti-stress and protector against cold, chills and humidity [

18].

It prevents muscle fatigue and scurvy, which is characterized by skin hemorrhaging, bleeding gums, brittle bones, anemia, joint pain and skeletal calcification defects [

18].

It contributes to the promotion and restoration of skin and the improvement of fine wrinkles [

19,

20]. Vitamin C masses did not exceed 1g in all samples. Values ranged from 0.19g to 0.67g. Nova 0.33 and 0.67g; berkane clementine 0.19 and 0.34g; nour 0.3 and 0.4g; ortanique 0.4 to 0.6g, our varieties are below the vitamin C limit of 41-50 mg/100g. Since 2007, Corsican clementines have benefited from an IGP (Protected Geographical Indication) with an acidity of between 0.65 and 1.4, lower than our results.

According to literature sources, ready-todrink orange juice contains around 16 g/L

of total citric acid, while real orange juice contains less than around 9 g/L [

21]; so, our concentrations on fresh juice are well within the norms of the commercial juices analyzed in these literature sources.

Orange juices are not only sufficiently rich in calories, but also contain adequate amounts of other essential nutrients, such as proteins, vitamins and minerals [

18,

22].

Citrus fruits generally have low levels of fatty acids as well, presenting it as an ideal fruit for people suffering from colon cancer, coronary heart disease or thrombosis [

22].

Citrus fruits exposed to southeast or northeast sunlight have a darker color and higher soluble sugar content, while shaded fruits tend to have a higher juice content. Fruits facing south-east are generally of good quality, particularly Berkane clementines. Fruit position affects juice pH, rind thickness and number of seeds [

23].

4. Materials and Methods

For each clementine variety resulting from the field trips, the total weight of each sample, the caliper size, the pH, the volume of pressed juice, the number of cores, the peel and the various physicochemical analyses were determined. At the same time, a comparative study was carried out with marketed orange juices.

Photo 1.

Sample of clementines.

Photo 1.

Sample of clementines.

4.1. Determination of Sugars by Hand Refractometer

The refractometer uses the principle of the refractive index of light. One or two drops of the sample, e.g. juice, are placed on the surface of the prism. The liquid deposited on the prism plate must be free from bubbles or floating particles of pulp or other matter. Close the prism cover carefully, the sample is crushed between the prism and the plate.

Point the instrument towards the light, and look through the eyepiece. For an accurate reading, we observe the reading through the eyepiece until a sharp image is obtained (by focusing), while light passing through the sample continues its trajectory and is reflected inside. Content is indicated by the position, on a vertical scale, of the dividing line separating an illuminated (light) zone from a dark zone. Where this line falls on the scale indicates the sugar content. From this refractive index, and following the catalog, we deduce the sucrose content of the juice.

4.2. Determination of Vitamin C Content in Juice

Vitamin C (C H O686 ) is the name commonly given to ascorbic acid. It is easily oxidized by many oxidizing agents, particularly oxygen in the air. After squeezing and filtering the orange juice through gauze, take a volume of 1 ml and place it in the Erlenmeyer flask. Next, add 10 ml of 5.10-3 M di-iodine solution. Add a pinch of starch starch. The solution is now black, due to the excess diiodine.

Fill the graduated burette with sodium thiosulfate solution C3 (concentration 3) =

5.0 10-3 mol.l-1 and titrate the remaining excess diiodine solution with thiosulfate until the black coloration disappears or the solution becomes discolored.

Note the volume of sodium thiosulfate poured at equivalence. Calculate the mass m of vitamin C in the entire fruit juice. The indirect titration method for vitamin C. Calculation of the mass m of vitamin C in all the fruit juice.

The mass of vitamin C in g and mg in total orange juice is:

no: Number of moles

m: Sample mass (g)

M: Molecular mass of ascorbic acid (g.mol-1)

V1: total volume of juice;

V2: volume of juice to be dosed

4.3. Determination of Total Sugars in Juice by Titration

Sugars are made up mainly of starch, and secondarily of sucrose and reducing monosaccharides. In an alkaline environment and in the presence of a reducing carbohydrate, 3,5-Dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) is reduced to 3-amino-5- nitrosalicylic acid.

The standard range consists of glucose solutions. The tubes are then placed in a water bath at 100°C for 5 min. After cooling for 5 min, 8 ml distilled water is added. Absorbance is read at 540 nm. Calculations are based on the calibration curve.

4.4. Determination of Citric Acid Content in Juice

After squeezing and filtering an orange juice, a volume of 2 ml is taken and poured into an Erlenmeyer flask, followed by 20 ml distilled water and two drops of phenolphthalein. Fill the burette with 0.1 mol/l sodium hydroxide, and titrate until the pink color appears and persists.

M (citric acid) = C (citric acid) x initial Vof juice (mg/g)

M: mass;

V: volume;

C: concentration.

4.5. Determination of Total Protein in Juice

The proteins contained in the supernatant (pressed juice) are assayed using the method of [

24]. The 0.2 ml protein extract with 1 ml Coomassie brilliant blue is shaken for 5 minutes. Absorbance is read at 595 nm. The amount of protein is determined using a standard range with increasing concentrations of bovine serum albumin.

4.6. Mineral Ion Assays

Nitrite (NO2- ), nitrate (NO3 -), sulfate (SO42 - ) and phosphate (PO43- ) ions are extracted and measured spectrophotometrically. Ions are measured in irrigation water and pressed juice.

4.6.1. Nitrate Determination

The NO3- method based on hydrazine sulfate reduction. Nitrates are reduced to nitrites by the addition of copper sulfate, hydrazine sulfate and sodium hydroxide.

Nitrites are then determined colorimetrically by diazotization with sulfanilamide and coupling with Nnaphthyl-diethylene diammonium dichloride (NNED). 1ml of sample added to 0.6 ml of copper sulfate (CuSO4; 25mg/l) after stirring, 0.4 ml hydrazine sulfate (0.69g/l) are added followed by stirring at 37°C for 5 minutes.

Finally, 0.6 ml NaOH (0.3N) is added with stirring at 37°C for 10 minutes. 1.5 ml of the mixture (sulfanilamide 40g/l and NNED 2g/l in 4.5N phosphoric acid) is added with stirring at 37°C for 10 minutes. Absorbance is read at 546 nm. NO3- concentrations are determined using a KNO standard range3- (0 to 0.2 mM).

4.6.2. Nitrite Determination

The NO2- method is based on reduction by N-azide3- in acid medium or by sulfamic

acid [

25,

26]. The oldest method involves forming a red azo dye with sulfanilic acid and α-naphthylamine (Griess reagent). The formation of an azo dye from sulfanilamide and N-(naphthyl1) ethylene diamine. To 25 ml of solution containing 5 to 50 µg of NO

2- , add 1 ml of sulfanilamide and wait 5 minutes. 1 ml naphthyl-ethylenediamine is added, topped up with 50 ml distilled water. Absorbance is read at 550 nm.

4.6.3. Inorganic Phosphate Assays

Inorganic phosphate in the samples was determined by the [

27]. The reaction medium consisted of 0.9 ml plant extraction medium and other extracts, 2.1 ml reagent (ascorbic acid 10%, ammonium heptamolybdate 0.42% in H

2 SO

4 1N, (1/6) (V/V), prepared at the time of use and stored at 4°C. After incubation for 20 minutes at 45°C (water bath), samples are cooled under a stream of water. The standard range is 0 to 0.1 mM. Absorbance is read at 820 nm.

4.6.4. Sulfate Dosage

To 25 ml of solution containing from 250 µg to 2 mg SO

42- , add 0.25 g barium chloride. Shake for 30 seconds and wait 30 minutes, then shake by inverting the bottle several times before measuring at 480 nm. The standard range is prepared with a solution of K

2 SO

4. [

28,

29].

5. Conclusions

Excessive humidity, young tree age and low temperatures can negatively influence sugar content, while the presence of grass in orchards has a positive effect on increasing sugar levels [

30]. Fruit appearance varies according to soil or cultural factors [

12,

13].

In general, variation in fruit size depends on the number of seeds per fruit. Berkane Clementine shows a positive correlation between the number of seeds per fruit and fruit size [

31]. Variation in fruit size also depends on growth conditions and inflorescence type [

32] number of seeds per fruit [

33]. growth regulators [

34]. and rootstock [

35].

Harvest date and fruit position on the tree affect fruit weight, diameter, bark color, pulp color and number of seeds [

36]. During harvesting, acidity decreases and ripeness index increases.

According to [

37]. acidity normalization ranges from 0.9 to 1.5%. However, the Carte noire, Berkane and Oroval varieties have an acidity of less than 0.9, which excludes them from the normalization range.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ahmed Matoir Mamie, Belabed Abdelmajid and Fadoua Belati. methodology, Ahmed Matoir Mamie; Fadoua Belati ; validation, Ahmed Matoir Mamie, Belabed Abdelmajid and Fadoua Belati.; formal analysis, Ahmed Matoir Mamie.; investigation, Ahmed Matoir Mamie; Fadoua Belati.; resources, Ahmed Matoir Mamie; Fadoua Belati.; data curation, Ahmed Matoir Mamie.; writing—original draft preparation, Ahmed Matoir Mamie.; writing—review and editing, Ahmed Matoir Mamie.; visualization, Ahmed Matoir Mamie, Belabed Abdelmajid.; supervision, Belabed Abdelmajid.; project administration, Ahmed Matoir Mamie. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

-

Brébion et al, 1999: Service des Espaces Verts et de l'Environnement de la Ville de Nantes.

-

MAPM, 2013: (Ministère de l'Agriculture et de la Pêche Maritime): Note de veille secteur agrumicole November 2013. Strategic note n°97. Strategy and Statistics Department.

-

Belati, 2007: Main pests of citrus fruits in the irrigated perimeter Moulouya irrigated perimeter. Dissertation. DESA. Univ. Mohamed I. Oujda.

-

Handaji et al, 2013: Pomological and organoleptic evaluation of 34 orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) variants from apomictic sowing in trial in the Gharb region. Al AwAmi A 127 - Year 2013.

-

Meric, 2012: Understanding the matrix effects of in vitro impact.

-

Metna et al, 2014: Effect of physicochemical parameters on fruit infestation by Ceratitis capitata WIEDEMANN, 1824 (DIPTERA: TEPHRETIDAE). AFPP-Dixième conférence internationale sur les ravageurs en agriculture Montpellier 22 et 23octobre 2014.

- 10 October 2012; -14, 7. International Seminar Antalya October 10-14, 2012.

-

Heinonen et al, 1989: Carotenoids in Finnish foods: vegetables, fruits and berries. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 37: p.655-659. [CrossRef]

-

Clotteau, 2002: Production of orange juice by coupling enzymatic treatment and tangential microfiltration. Master's thesis. ENSIA/SIARC. Agro. Univ. Montpellier.

-

Walali Loudyi et al, 2003: Fiches techniques: le bananier, la vigne, les agrumes. In T. d. t. e. agriculture (Ed.). Rabat: Institut Agronomique et vétérinaire Hassan II.

-

Van Ee, 2005 : Fruit growing in the tropics.Wageningen.

-

Metha and Bajaj, 1984: Changes in the chemical composition and organoleptic quality of citrus peel candy during preparation and storage. J Food Sci Technol 21:422-424.

-

Lodhi et al, 1987: Allelopathy in agroecosystems: wheat phytotoxicity and its possible role in crop rotation. J. Chem. Ecol. 13, 1881-1891. [CrossRef]

-

Cruse et al, 1982: The effect of rainfall and irrigation management on citrus juice quality in Texas. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 107: 767-770.

-

Wutscher, 1977: Performance of young nucellar grapefruit on 20 rootstocks. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 102: 267-270.

-

Okwu, 2005: Phytochemicals, Vitamins and Minerals Contents of Two Nigerian Medicinal Plants, International J. Molecular Medicine and Advance Sciences, 1,375-381.

-

Okwu, 2003: Investigation into the Medicinal and Nutritional Potentids of Garcinia kola Heckel and Dennettia Tripetala G. Baker Ph. D Thesis Michael Okpara University of Agriculture Umudike, Nigeria pp. 20-31.

-

Okwi and Emenike, 2006: Evaluation of the Phytonutrients and Vitamin Contents of Citrus Fruits. International J. Molecular Medicine and Advance Sciences 2(1), 1-6.

-

Roger, 1999: New Life Style Enjoy It. Editorial Safelie SL Spain pp. 75-76.

-

Okwu, 2008: Citrus fruits: A rich source of phytochemicals and their roles in human health. International Journal of Chemical Sciences, 6(2), 451-471. Retrieved from.

-

Penniston et al, 2008: Quantitative Assessment of Citric Acid in Lemon Juice, Lime Juice, and Commercially-Available Fruit Juice Products.

-

Okwu and Emenike, 2007: Nutritive Value and Mineral Content of Different Varieties of Citrus Fruits, J. Food Technology, 5(2), 92-1054.

-

Mars et al, 1994: Study on quality variability in citrus fruits harvested from the same tree. I. Effects of harvest date, fruit orientation and position in the foliage. Fruits (Paris), 49 (4): 269-278.

- A: 1976, 1976; 24. Bradford, 1976: A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding.

-

A.W. Morris and J.P. Riley, 1963: The determination of nitrate in sea water Analytica Chimica Acta Volume 29, 1963, Pages 272-279. [CrossRef]

-

K. Toei and T. Kiyose, 1977: Extraction-photometric determination of trace amounts of nitrite in waters. [CrossRef]

-

Ames method, 1966: Assay of inorganic phosphate, total phosphate and phosphatase. In: Methods in Enzymology s.p. colowik and N.N. KAPLAN eds, vol.8, Academic press, New York, London. 115-118.

-

B.W. Grunbaum and N. Pace, 1965: Simplified Determinations of Ammonia, Urea, Creatinine, Creatine, Phosphate, Uric Acid, Glucose, Chloride, Calcium, and Magnesium.

-

J.W. Wimberley,1968: The turbidimetric determination of sulfate without the use of additives. [CrossRef]

-

Benaissat, 2015: special siam 2016. supplement of tuesday 26 april 2016 - cannot be sold separately - legal deposit 100/1991.

-

Essalhi et al, 2016: Etude de la variation de la qualité des fruits de dix clones de clémentinier (Citrus clementina) dans la région du Gharb [Study of the variation of the quality of the fruit of ten clones clementine (Citrus clementina) in the region of Gharb], 15(2), 319-328.

-

Barry et al, 2004: Soluble solids in 'Valencia' Sweet organge as related to Rootstock selection and fruit size. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 594: 598-598. [CrossRef]

-

Cameron et al, 1960: Fruit size in relation to seed number in the Valencia orange and some other citrus varieties. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. Proc. 76: 170-180.

-

Goodwin et al, 1978: Phytohormones and fruit growth. In DS Letham, PB Goodwin, TJ Higgins, eds, Phytohormones and Related Compounds: A Comprehension Treatise, Vol 2.-ElsevierNorth Holland Biomedical Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp 175-213.

-

Wutscher et al, 1999: Performance of 'Valencia' Orange on 21 Rootstocks in Central Florida. HORTSCIENCE 34(4): 622-624. [CrossRef]

-

Mars et al, 1994: Study on quality variability in citrus fruits harvested from the same tree. I. Effects of harvest date, fruit orientation and position in the foliage. Fruits (Paris), 49 (4): 269-278.

-

EACCE, 2010: Etablissement Autonome De Contrôle et de Coordination Des Exportations. Revue Trimestrielle - Campagne 2010-2011 - N° 30. http://web2.eacce.org.ma/Portals/0/ Regl543-Norme%20Agrumes.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).