1. Introduction

In international relations, environment, and climate change only recently became a part of the mainstream discourse. The international efforts are directed at reducing Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions caused by fossil fuels. One of the most visible and tangible effects of climate change and environmental degradation is global warming and the melting of glaciers. Keeping in view that climate change is the most severe threat faced by all international communities, the issue was only recently acknowledged as the biggest threat to coming generations. The implications of climate change include pollution, loss of biodiversity, destruction of local ecosystems, deforestation, change in habitats, and natural disasters. It is induced by both human activities and nature. Industrialization, GHG emissions, and inefficient infrastructure contribute to climate change. The GHG emissions are a result of fossil fuel energy sources and the massive industrialization in the last two centuries. Carbon dioxide emissions in the 1700s were thirty percent lower than the current emissions rate, while the years 2015 to 2019 have been the warmest years recorded in history. The most prominent effort to mitigate the threats to the earth’s environment was made in 2015 when a hundred ninety-five countries signed the Paris Agreement. The agreement calls for sweeping measures to contain the earth’s rising temperature, which is mainly owing to GHG emissions. The Paris Agreement calls for measures to prevent the earth’s temperature from rising beyond 1.5 degrees Celsius. The developed countries are the main sources of GHG emissions, with the USA and China being the largest GHG emitters in the world. The Paris Agreement calls on developed countries to limit and cap their quota of global GHG emissions (Climate Action Tracker, 2020). The agreement directs the parties to phase out the use of coal-fired energy sources entirely and utilize renewable energy sources instead, as coal is the biggest contributor to GHG emissions. China is a party to the agreement with a robust domestic environmental policy. Major infrastructure projects undertaken by the developed world are mandated by the Paris Agreement to adhere to environmental protection. The study adopted a quantitative research design using the Green Theory of Politics which deals with the environmental concerns outside the realm of national interests and state competition. The opinion of the IR experts the university’s faculty and some other field experts was considered to conduct the study in relation to find out how BRI affects the Eurasian environment in relation to its implementation. Taking the implementation experience of BRI, the study took a turn to explore the relationship between the vision of BRI with respect to its implementation that will further lead to the finding out the impacts of BRI on the Eurasian environment.

The Belt and Road Initiative is hailed as the twenty-first century Silk Road owing to its massive geographical coverage and tremendous resources and capital involved. BRI extends from China, passing through Asia, and Africa and finally connecting it to Europe. On completion of all phases, BRI will connect three continents; the proposed route follows the ancient Silk Road hence becoming the modern Silk Road. The BRI initially One Belt One Road (OBOR) consists of two components; the first is the Silk Road Economic Belt, and the second is the Twenty-First Century Maritime Silk Road. At its core, BRI connects the least developed Western region of China to Asia, Africa, and Europe via development infrastructures such as railways, highways, and maritime routes. The BRI is one of the largest development projects in the history of mankind (Kai, 2017). The BRI is an investment of US $ 850 billion, consisting of nine hundred projects that span around sixty-five countries. This project engages two-thirds of the global population and three-fourths of the global energy resources. The Silk Road Economic Belt consists of three major routes, first from China to Europe, the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean, and the Persian Gulf. In its entirety, the Silk Road Economic Belt provides connectivity between China, the Middle East, Central Asia, and Europe. The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is set to connect Asia, Africa and Europe. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was set up entirely to finance the whopping nine hundred billion dollars of investment. The BRI is a combination of various infrastructural and developmental projects ranging from railways, gas pipelines, economic corridors, industrial parks, Special Economic Zones, energy, mining, and IT Sector development to the development of seaports along the BRI routes. The BRI is considered the signature project of Chinese President Xi Jinping. The plans for BRI were announced in 2013, followed by whirlwind diplomacy led under the leadership of the Chinese President to realize the project and initiate work as early as possible. BRI’s major objectives include coordination of policy issues among the partner countries, enabling regional connectivity through infrastructural development, promotion of trade among the member countries, financial integration, and an all-encompassing improvement of relations among the partner countries. Free trade agreements are a part of policy coordination. The project focuses on remedying the missing links in infrastructural development and ultimately enabling regional connectivity as well as access to Chinese markets to diverse marketplaces (Sarker, 2018).

In 2014 BRI was declared a part of China’s National Economic Development Strategy at the Central Economic Work Conference. The multi-billion projects, along with regional connectivity and Chinese market access to global avenues, also aim towards dealing with the uneven economic development in China’s Western regions to that of the eastern coastal regions. The Western regions, particularly the Xinjiang Autonomous Region, are plagued with poverty along with religious extremism and unrest. The economic development enabled by the BRI will result in prosperity and development for the Western provinces, including Tibet, Gansu, and Qinghai, and, in the case of Xinjiang, address the poverty and resentment among the population. Hence the Chinese BRI has multipronged advantages, including regional connectivity to neighbors and key states, access to global markets to enhance Chinese exports, China’s involvement via BRI in more than sixty countries across the three continents, access and management of resources under the BRI, development in the Western Chinese regions and eradication of poverty, separatism and religious extremism which the Chinese policymakers correlate directly to poverty and under development.

2. Theoretical Framework

The Green Theory of Politics deals with environmental concerns outside the realm of national interests and state competition, unlike the leading IR theories such as realism, liberalism, and critical theory. Green theorists shift the focus from an anthropological view to ecocentrism, putting the needs of nature and non-human beings also into consideration. Green theory suggests a change in the attitudes to address environmental issues, particularly climate change. States are driven by short-term goals such as economic or environmental gains; green theorists suggest consideration of long-term ecological implications as central to any state decision. Moreover, the green theory requires a global approach rather than being limited to one or a few states. The green theory declares climate change to be a consequence of collective human actions that cannot be undone or remedied by the actions of a few. Hence a globalist approach is suggested to combat environmental issues (Dyer, 2018).

The BRI, as predicted by green theory, is driven primarily by short-term economic gains. Though the environment is touched upon as an issue, the BRI does not take environmental issues into consideration in the planning or implementation stages. Being a global project encompassing over sixty partner states, the BRI actually presents an opportunity to develop and implement a global effort to undo climate change as suggested by the green theory. Environmental issues are limited to just declarations; the BRI is a platform to actually adopt norms, institutions, and policies that centralize environmental protection as a key issue rather than a short-term goal.

3. The Building of Special Economic Zones and Industrialization

Special Economic Zones(SEZs) are defined as “geographically delimited areas within which governments facilitate industrial activity through fiscal and regulatory incentives and infrastructure support”. The regulations in the SEZs are different from the rest of the country which is more favorable to investors. SEZs are designed to facilitate and encourage Foreign Direct Investment. SEZs were introduced in the fifties; by the seventies, a number of states in East Asia and Latin America had developed SEZs. Though SEZs are a successful phenomenon, the most successful experience of SEZs belongs to China. In 1979 China established four SEZs; after massive success, fourteen more SEZs were established in the Southern areas. The SEZs brought in massive Foreign Direct Investment for Beijing (Barone, 2020). China now has around fifteen hundred functioning SEZs, accounting for twenty-two percent of the country’s GDP and forty-six percent of the FDI (Khan, 2018). Under the BRI, China is set to replicate its success.

Pakistan will receive a large buck of special economic zones planned under the BRI. The Bostan Industrial Zone in Balochistan has been notified as a SEZ while the rest are undergoing preliminary stages such as feasibility studies and land acquisitions. Bostan Industrial Zone is located over an area of 1000 acres. The Rashakai Economic Zone is being built on 702 acres; the Dhabeji Zone is being built on 1530 acres, the Allama Iqbal Industrial City is provided with 3217 acres of land, the ICT Model Industrial Zone is allocated 200-500 acres of land, 1078 acres of land is allocated for Mirpur Special Economic Zones, 350 acres is allocated for Mohmand Marble City while 250 acres of land is proposed for Moqpondass Special Economic Zone (Special Economic Zones, 2020).

4. BRI Transport Projects

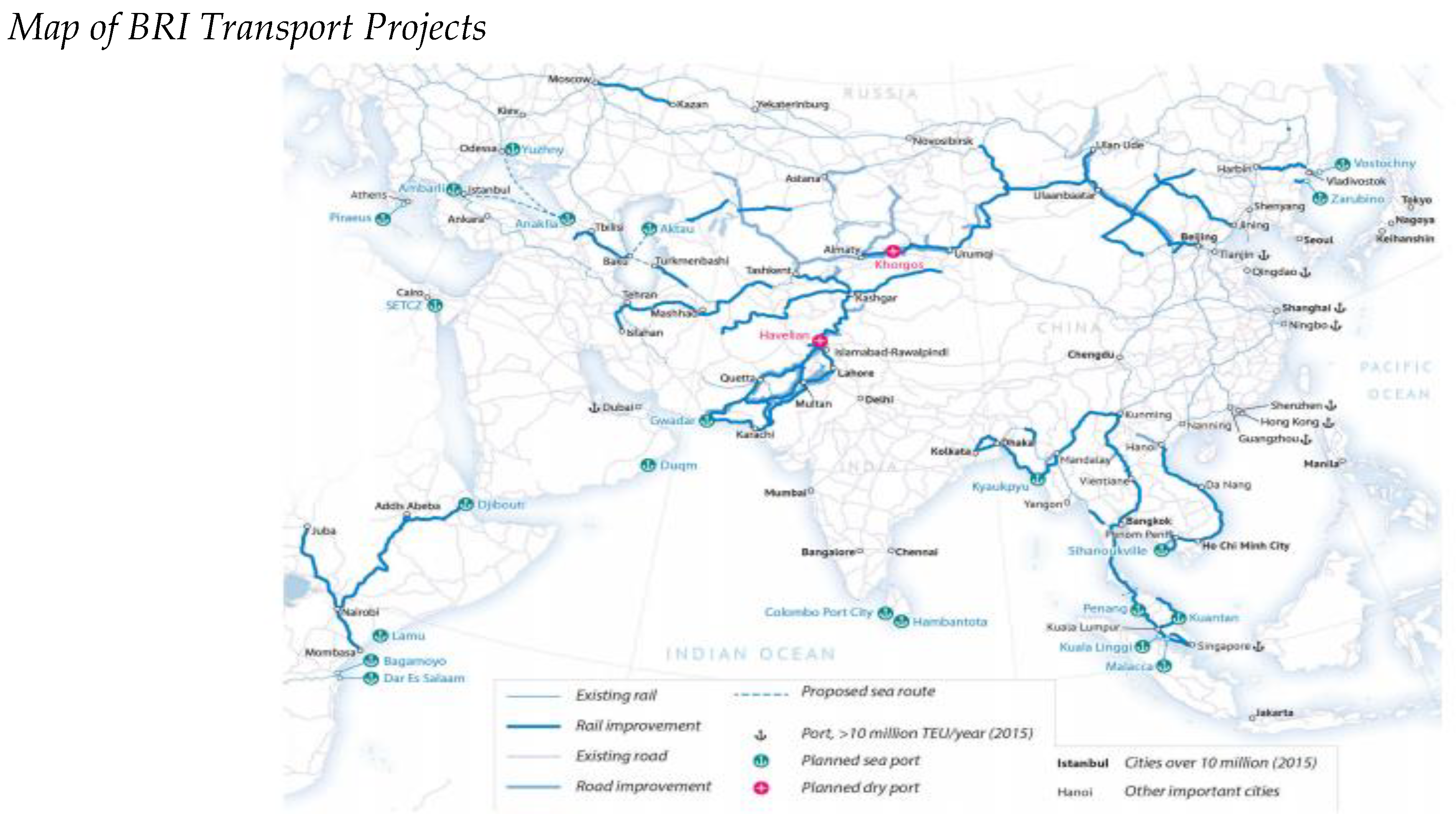

Figure 1.

Geographic Map of highways, railways, and seaports along with the Countries and cities it will connect under the BRI project (Losos, 2019).

Figure 1.

Geographic Map of highways, railways, and seaports along with the Countries and cities it will connect under the BRI project (Losos, 2019).

BRI transport projects consist primarily of highways, railway links, seaports, mass transits, and freight lines across sixty countries. The total of mappable roads along the BRI is 170,126 km; the railway lines span 80,451 km, while pipeline networks run along 343,677 km (Losos, 2019). The BRI development projects span South Asia, Central Asia, South East Asia, Africa, and Europe. Twenty-eight railway lines are being constructed and improved upon, twenty-three highways and mass transits are under development, while a total of fifteen seaports and terminals are currently being built in the partner countries. In some cases, these railway links and roads connect with the six aforementioned economic zones. The development of infrastructure takes up the biggest chunk of BRI projects. The objective guiding such large-scale investment in transport development is rooted in connecting land trade routes for China. The network of rails and roads will translate into the speedy transfer of goods and services. Moreover, the companies participating in construction are generally Chinese state-owned and private firms hence creating opportunity and generating revenue for Chinese citizens. Developed infrastructure means connectivity, setting of urban centers, industrialization, and access of Chinese producers to newer markets. For building newer railway links and roads, the areas of the projects will be deforested, and the existing set-up will be replaced with the state of the art infrastructure. The tables below detail the extensive transport development under the BRI.

Table 2.

Railway Links under the BRI.

Table 2.

Railway Links under the BRI.

| Railway Project |

Country |

| Padma Rail Link |

Bangladesh |

| Europe-China – Rail Link I & II |

Multiple |

| Budapest–Belgrade Railway |

Multiple |

| Lagos-Calabar Railway |

Nigeria |

| Sino-Thai – High-Speed Railway |

Multiple |

| Abuja-Kaduna Railway |

Nigeria |

| Savannakhet-Lao Bao Railway |

Laos |

| East Coast Railway |

Malaysia |

| Bangkok-Nong Khai Railway |

Thailand |

| Addis Ababa Light Rail |

Ethiopia |

| Khunjerab Railway |

Pakistan |

| Karachi Circular Railway |

Pakistan |

| Muse-Mandalay Railway |

Myanmar |

| Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) |

Kenya |

| Chad-Cameroon & Chad-Sudan Railway |

Chad |

| Djibouti-Ethiopia Railway |

Multiple |

| Tehran-Mashhad Railway |

Iran |

| Bangkok-Chiang Mai Railway |

Thailand |

| Jakarta-Bandung Railway |

Indonesia |

| Pap Angren Railway |

Uzbekistan |

| Lagos-Kano Railway |

Nigeria |

| Gemas-Johor Bahru Railway |

Malaysia |

| Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High-Speed Rail |

Multiple |

| Benguela Railway |

Angola |

5. Energy Infrastructure Under the BRI

BRI has thirty-three energy projects in the pipeline. The projects range from coal power plants to pipelines to hydropower dams, LNG projects, and wind power stations. Cooperation in the field of energy is one of the most critical aspects of the BRI. Pakistan receives the largest share of BRI energy projects. The distribution for energy projects is displayed in the chart below.

5.1. Distribution of BRI Energy Projects

List of energy projects under the BRI.

| Project Name |

Country |

| Lower Seasan Two Hydro Power Dam |

Cambodia |

| Central Asia China Gas Pipeline |

Multiple |

| Diamer Basha Dam |

Pakistan |

| Engro Thar Block II Power Plant |

Pakistan |

| Karuma Hydro Power Project |

Uganda |

| Yamal LNG Project |

Russia |

| Nurek Hydropower Rehabilitation Project Phase I |

Tajikistan |

| Natural Gas Project |

Bangladesh |

| Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline Project |

Azerbaijan |

| Tarbela 5 Hydro Power Extension Project |

Pakistan |

| Kohala Hydel Power Station |

Pakistan |

| Phander Hydropower Station |

Pakistan |

| Rahimyar Khan Power Plant |

Pakistan |

| Cacho 50MW Wind Power Project |

Pakistan |

| Gilgit KIU Hydropower |

Pakistan |

| Suki Kinari Hydropower Project |

Pakistan |

| Sahiwal Coal Power Project |

Pakistan |

| Quaid e Azam Solar Park |

Pakistan |

| Port Qasim Power Project |

Pakistan |

| Matiari Lahore Transmission Line |

Pakistan |

| Gaddani Power Project |

Pakistan |

| Balloki Power Plant |

Pakistan |

| That Mine Mouth Oracle Power Plant |

Myanmar |

| Sachal 50MW Wind Farm |

Pakistan |

| Hydro China Dawood 50MW Wind Farm |

Pakistan |

| UEP 100MW Wind Farm |

Pakistan |

| Sahiwal 2x660MW Coal Fired Power Plant |

Pakistan |

| Neelum Jhelum Project |

Pakistan |

| Nasayian Hydropower Project |

Georgia |

| Hassyan Clean Coal Project |

UAE |

| Kayan River Hydro Power Plant |

Indonesia |

Source: (Belt and Road Initiative, 2020).

Figure 2.

Detailed digestion of BRI and its main projects (Hao, 2020).

Figure 2.

Detailed digestion of BRI and its main projects (Hao, 2020).

6. Assessment of BRI’s Impact on the Environment:

After the groundbreaking success of SEZs in China’s economic growth, the SEZ model spread throughout the country; changes were incorporated in the original design according to the local demands. The SEZs are, in fact, considered to be one of the main drivers of industrialization in China and its ascend as a global economic power. However, along with accelerated industrialization China experienced a reciprocal increase in environmental pollution, adverse effects of climate change such as resource scarcity, and public health issues. In 2006, China became the leading emitter of Greenhouse gases, and the industrial sector accounted for seventy-six percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. SEZs house the most notable chunk of greenhouse gas emitting industries in China; hence the SEZs indirectly became the leading cause of China’s Greenhouse gas emissions (Kim, 2017). To deal with this threat, the Chinese policymakers began researching for a sustainable and environmentally friendly design for the SEZs. In 2003, the Chinese government set up an Eco-Industrial Park (EIP) to incorporate environmentally friendly modes of production. The objective was to test the efficiency of a resource-efficient and environment-suitable industrial zone. In 2005 the Circular Economy Demonstration Industrial Park (CEDIP) was also established. The mantra of recycling, reusing, and reducing was adopted with curbs on CO2 emission levels. The CEDIP program later evolved into the Circular Transformation of the Industrial Park program in 2012. The provisions were made consistent with Beijing’s environmental commitments. The special economic zones developed under this program focused on clean energy industries. Furthermore, the next year, Beijing established the Low Carbon Industrial Parks (LCIP) to monitor and strictly ensure low CO2 emissions using viable technology and procedures in the SEZs. Low-carbon industrial parks were promoted by the Chinese government under this program. The analysts claim that China’s green industrialization programs have been a success. Local governments, as well as private stakeholders, adopted the government-initiated projects, and all the environment-related objectives laid out in the eleventh and twelfth five-year plan have been successfully accomplished. Thirteen percent of fifteen hundred SEZs in China belong to either EIP or LCIP (Abdelhak Senadjki, 2022). Tangible advantages of these programs include a reduction in toxic discharge as well as a reduction in CO2 emissions. Furthermore, the Chinese government now considers environmental policy one of the core evaluation factors for awarding contracts for company services.

Nine economic zones are planned for Pakistan, while one for Kazakhstan and Egypt each. By 2016, Chinese investment financed fifty-six industrial parks and economic zones in the BRI countries. The Paris Agreement dictates that regional and local projects must be designed in accordance with environment-friendly policies. The SEZs are required to cater to the local ecosystem and environmental stability. The environmental instability includes loss of land, increased air pollution, increased energy consumption, and water stress. South Asia is becoming one of the most water-stressed regions in the world. The SEZ in Dhabeji is assessed to contribute to higher levels of air pollution, energy consumption, and water stress with low levels of loss of land. The Rashakai Special Economic Zone will affect the medium loss of land, low levels of air pollution, and water stress with medium levels of energy consumption, whereas the Faisalabad SEZ is assessed to result in medium levels of land loss with high levels of water stress, air pollution, and energy consumption. This shows that the SEZs planned under the BRI hardly incorporate the guidelines set under the Paris Agreement directing the stakeholders to lay special emphasis on environmental protection and sustainability (Ahmed, 2020).

The SEZ selection in Pakistan is driven entirely by the FDI and export factors. The success of an SEZ is no doubt dependent on these factors; however, the environmental factor is also critical. An evaluation of SEZs in Pakistan reveals that the environmental stability, safeguarding of local ecological structures, and adaption of policies according to the threat of climate change have not been considered. Maximum export yield has been the central characteristic of policymaking. Pakistan is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change as the country struggles with air pollution, deforestation, water scarcity, and natural environmental disasters. The issue of environmental protection or the adaptation of the Eco-industrial zones or parks has not been observed in the BRI SEZs in Pakistan Egypt, and Kazakhstan. The Eco-Industrial Zones operate with the objective of ensuring environmental stability, waste reduction, and strict adherence to environmentally friendly principles (Ahmed, 2020). According to the available information, the SEZs planned under the BRI do not follow the principles of China’s own tested and implemented policies of Eco-Industrial Parks or Low Carbon Industrial Parks. The evidence of environmental consideration in terms of SEZs is simply unavailable, contributing to the assessment that the BRI SEZs are mainly modeled on the previous versions of economic zones rather than the environment-friendly parks envisioned by the Eco-Industrial or Low Carbon Industrial Parks. As assessed by the International Institute for Sustainable Development, most of China’s greenhouse-emitting industrial clusters were located in the SEZs when China was the largest global contributor of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in 2006. This grim statistic is a reminder that SEZs would become the leading source of environmental degradation and loss of ecological systems in Pakistan, as well as other recipients of BRI-financed special economic zones (Tan, 2021). Some reports suggest that SEZ plans are being updated to incorporate environmental considerations after Beijing’s declaration of “The Belt and Road Ecological and Environmental Cooperation Plan” in 2017. This plan envisions a “green BRI”, though owing to the shrouded nature of the BRI projects in general and the unavailability of updated information certifying the environmental safety in SEZ projects raises skepticism. Moreover, the plan is more of a declaration rather than a legally binding document. It is, however, critical to note that approximately thirty renewable energy plans under the BRI are currently being constructed, mostly relating to solar and wind renewable energy generation (Gu, 2020).

The BRI is focused on industrial buildup; after the completion of all BRI phases, the leading BRI member countries are expected to experience a boom in industrial productivity. China’s official policy for BRI investments and loans to its domestic firms does not dictate environmental performance or adherence to environmental safety. Internally China evaluates investment companies based on strict criteria of safe environmental practices and policies. Despite the conception of “Green BRI”, no such criteria have been enacted for BRI projects. In fact, the Chinese government encourages local coal sector companies to seek maximum investments in BRI projects. China’s coal sector experienced a massive downfall in contracts and investments owing to Beijing’s adoption of safe environmental policies such as the Low Carbon Industrial Parks. Coal-fired projects are among the leading sources of CO2 emissions. China, domestically conscious of harmful environmental practices, is, unfortunately, encouraging these practices in BRI projects (Eder, 2019).

6.1. CO2 Emissions Caused by BRI Projects

CO2, along with other Greenhouse gases, is the major cause of climate change. To mitigate the threat of climate change, the levels of greenhouse gas emissions are required to be capped. Currently, BRI countries contribute thirty percent of the global GHG emissions (Hou, 2020). According to estimates, the BRI partner countries are expected to contribute a staggering sixty percent of global GHG emissions by 2030. This estimate does not account for the BRI projects as the sole cause of this massive contribution as heavily industrialized China and India while oil-producing Iran and Saudi Arabia are the major contributors of GHG emissions owing to the very nature of their own industrial development and generation of fossil fuel energy (Logan, 2019). BRI countries possess numerous untapped renewable energy resources; however, infrastructure and development of these resources are virtually non-existent, resulting in heavy reliance on fossil fuels to fulfill energy demands. The BRI transport projects, including the railways, highways, sea, and airports, along with energy infrastructure including power plants and dams, are expected to be primarily powered by fossil fuel. The extent and scope of BRI projects are massive; even if half of the BRI projects are fueled by fossil fuels, the level of GHG emissions and their toll on the environment is staggering (Gu, 2020).

Among sixty-five BRI partner states plus twenty-three countries receiving investments under the banner of BRI, twenty-five percent of CO2 emissions from the production-based perspective came from the transport, electricity, nonmetallic, and ferrous metals sectors. The largest production-based CO2 emissions in the BRI plus twenty-three countries have been contributed by the electricity sector followed by the transport sector. While from the consumption perspective, the BRI-plus countries contributed twenty-four percent of the global CO2 emissions, the largest share belongs to the electricity and construction sector. In terms of production, thirty, three percent of the global CH4 (a member of greenhouse gases ) emissions came from BRI-plus countries with government services as the largest contributor to CH4 production-based emissions. In terms of consumption-based global CH4 emissions, the BRI plus twenty-three contributes twenty-three percent primarily from animal products and construction. The percentage of global NCO2 production-based emissions is thirty-six percent, mainly from animal products and fruits, while thirty-seven percent of the global N2O consumption-based emissions came from the BRI plus twenty-three countries primarily from animal products and government services. The GHG consumption and production emissions of BRI plus twenty-three countries have steadily increased over the years (Hou, 2020).

The detailed analysis shows that transport, electricity, government services, and construction are the main drivers of production as well as consumption-based CO2 emissions in BRI plus twenty-three countries. BRI countries are largely developing or underdeveloped economies with an average per capita GDP of US$1200. The average consumption of electricity stands at four thousand kilowatts per hour. The social development level is low, along with an average to low human development index. The environmental regulations in BRI member states range from average to non-existent. BRI infrastructure, as well as energy projects, are carbon-intensive; the recipient states and investors either do not realize the risk of heavy carbon-intensive investment or, in some cases, actively de-risk it in favor of capital generation (Zdek, 2019). The nature and extent of carbon emissions are usually set at the initial phases when the contracts are drawn. The technology, procedures, regulations, and entire strategy to implement a project are guided by the same decisions at the contractual phase of the project. Hence decisions made related to the use of GHG-intensive technology and projects under BRI are expected to remain unchanged for decades, even in response to the opposition by environmental activists (Zdek, 2019). Along with the rise in emissions of GHG gases, the non-GHG environmental pollutants are particularly hazardous to health.

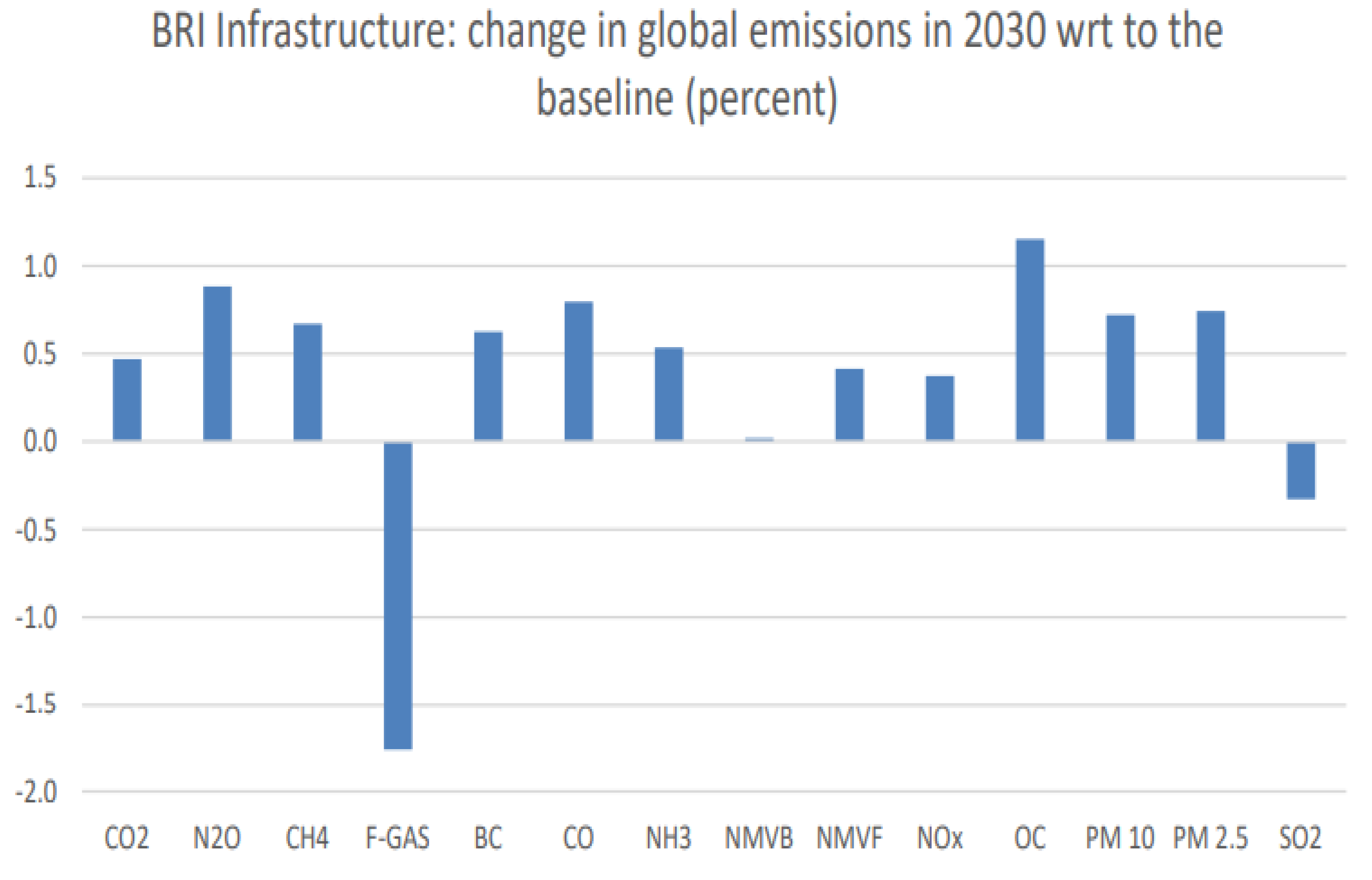

Figure 5.

Change in Global Emissions with respect to BRI infrastructure in 2030 (Maliszewska, 2019).

Figure 5.

Change in Global Emissions with respect to BRI infrastructure in 2030 (Maliszewska, 2019).

The figure above shows that the BRI contribution to the GHG emissions globally will experience an aggregate increase except for the F-Gases. Other non-GHG emissions with significant health hazards will also undergo a steady increase except the SO2. Methane gas emissions are expected to rise by 0.6 percent in the BRI region. The use of fossil fuels is the major contributor to methane gas emissions in the BRI region.

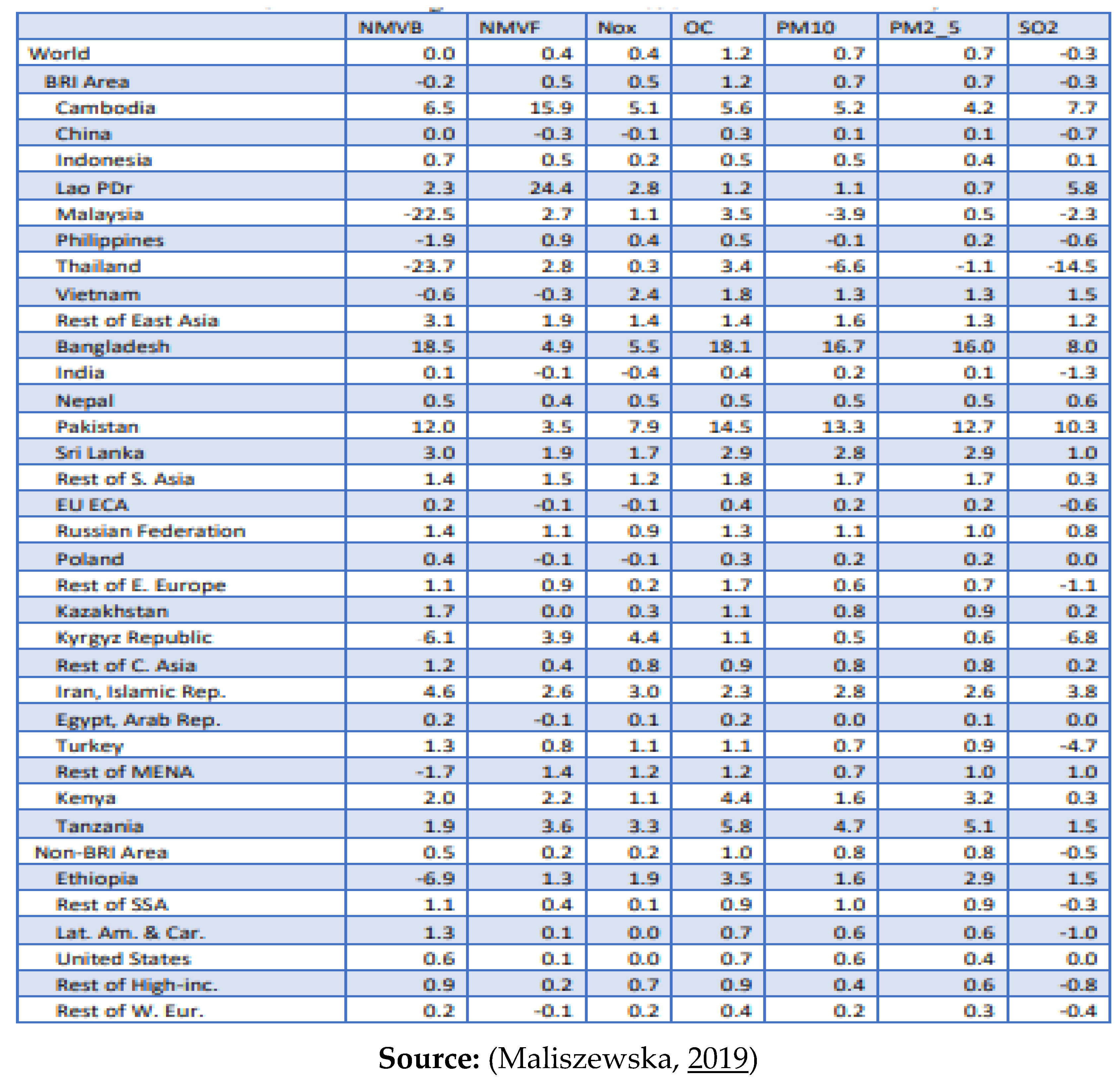

Figure 6.

Projected Percent change in harmful gas emission in BRI countries by 2030. Source: (Maliszewska, 2019)

Figure 6.

Projected Percent change in harmful gas emission in BRI countries by 2030. Source: (Maliszewska, 2019)

The above figure shows a steady increase in GHG emissions as well as major non-GHG emissions except the F-gases emissions, SO2 emissions, and NMVB emissions.

7. Risk to Biodiversity and Local Ecological Systems

The Current Biology journal estimates that BRI projects could introduce eight hundred alien invasive spaces, causing havoc on the local ecological system (Valentine, 2020). The invasive species, including vertebrates as well as insects and pathogens, could have massive implications for the local agricultural sector as well as livelihood patterns. The environmental damages, in the long run, include the loss of biodiversity and local ecological systems that could have damning consequences for local livelihoods as well as the agricultural sector (Dasgupta, 2019).

Economic corridors along the BRI route occupy a major land mass along with passing through significant ecological habitats. There are six economic corridors under construction, spread out from South Asia to Central Asia to South-East Asia. Under these economic corridors, vast rails and road projects are being built, passing through ecologically sensitive areas. There is a possibility that the development of transport infrastructure will put the ecological situation of these areas, particularly the Eurasian region, at risk. According to the World Wildlife Fund, sensitive ecological environments face an acute risk from the BRI projects. There are significant ecologically sensitive areas along the BRI route. The BRI route can significantly harm approximately seventeen hundred important bird areas and key biodiversity areas. A staggering 265 endangered species will suffer the hazards of BRI projects, including white tigers and saiga antelope (Environmental and Energy Study Institute, 2018).

Hydropower projects under the BRI have manifested a strong threat to local ecological systems. Though the source of energy is sustainable, the environmental threat posed by certain hydropower projects, in the long run, is way too great. BRI-financed Sumatra Dam constructions have raised concerns regarding the preservation of local ecological habitats. Its construction plan involves blasting off of a tunnel, construction of roads, and flooding of a large area of the nearby jungle. The Baran Toru ecosystem faces a severe risk of environmental harm, particularly its orangutan population and jungle. Both the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank refused to finance the project owing to its tremendous damage to the local ecological system. However, the Chinese hydropower company in charge of the project is likely to receive funding from China’s state-owned bank. The Indonesian government though under pressure to scrap the project altogether, is unlikely to give in owing to the financial and energy-related advantages of the dam (Environmental and Energy Study Institute, 2018).

In Myanmar, a hydropower project posing similar challenges to the local ecological system and habitat has stalled since 2011. The Myitsone dam, a controversial BRI project, faced the public’s, conversions, and environmentalists’ opposition owing to its irrefutable damage to the local ecological systems, including flooding and change in degradation of ecological habitat and adverse impact on local communities, including loss of livelihood. BRI hydroelectric projects along the Mekong River have also spelled disaster for local communities, such as increased flooding, changes in the fisheries breeding patterns, and reduced levels of water streams to Southeast Asian countries located on the lower downstream. The Mekong River passes through five Southeast Asian countries, and the construction of dams along the river has proven to alter the flow of the river and halt the fish migration that is crucial for local livelihoods (Valentine, 2020). A total of twenty dams have been built on the Mekong River so far, whose environmental impacts, along with changes in fish populations and water flow, also include an increase in methane emissions.

The Fisheries Action Coalition Team states that the stock of fish has decreased in recent years owing to the BRI-funded hydroelectric projects along the Mekong River. According to a report published by the Mekong River Commission Council Study examining the effects of the BRI hydropower project on the Mekong River reveals that plans for the construction of eleven dams on low streams spell severe risks for the local ecological system (Hong, 2018).

8. The Green BRI is a Myth

In 2016, the Chinese government indicated an environment-conscious and environment-friendly BRI. President Xi Jinping himself called for the BRI partner states to strengthen cooperation on issues related to the environment, ensure the protection of ecological life, and transform the project towards a green Silk Road. This declaration is quite consistent with China’s effective environment-conscious policies domestically. The rising air pollution, water scarcity, and other climate change impacts forced the Chinese government to reconsider its use of coal energy. Beijing has also shown commitment to the Paris Agreement and enforced a policy framework to cap its share of carbon emissions. The declaration of a green BRI is a part of the continued Chinese effort to lead the world in the global fight against climate change, at least on paper. In 2017 “The Belt and Road Green Development and Climate Governance” kicked off. The event was organized to discuss the incorporation of the “ecological civilization” concept forwarded by the Chinese leadership. A think tank called “ Belt and Road Green Development Partnership" was also established by the Chinese and international NGOs to promote low-carbon development among the BRI partner countries (Li, 2017).

A number of environmental activists expressed concerns over China’s practices that will result in high emissions development, disturbances to local ecological patterns, and deforestation. The question arises about how effective the green BRI plan and is whether the Chinese governance of the BRI allows space for sustainable development. The Chinese government issued guidelines to the investors with regard to environmental safeguards and considerations for the BRI projects. The document is titled "Guidance on Promoting Green Belt and Road" and issues a number of recommendations on environment-friendly practices and procedures. However, the document is only advice and an official recommendation. It carries no legal value; implementation of the guidelines is entirely the decision of investors. This effectively reduces the guidelines as the Chinese attempt to appease international organizations and global powers. Similarly, “The Belt and Road Ecological and Environmental Cooperation Plan”, issued in 2017, contains a bunch of recommendations to investors and partners regarding the preservation of ecological life and environment-friendly policies, without making any legally binding provisions. A few other Chinese actions attempt to fool the observers into thinking that environmental safeguards are being implemented in the BRI projects; however, in reality, those measures have minimum to zero impact, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) claims that its environmental protection provisions are extremely strict and updated; however, the AIIB finances a minute amount of BRI projects. Its environmental policy, in the long run, has no impact on the entirety of BRI. Most BRI projects are being financed by Chinese state-owned banks, while the coal projects are being financed by domestic coal sector companies. The twenty-seven banks are financing the BRI focus on energy-related projects. Fossil fuel, particularly coal, is the enemy of the environment. These banks have loaned approximately $ 160 billion on energy investments in the BRI; eighty percent of the investment went to the fossil fuel sector, while the total investment in the coal sector stood at $43.3 billion. Only twenty percent of the total energy investment went to renewable energy such as hydropower, wind, or solar energy. The majority of China’s hydropower projects, despite being a source of renewable energy, contribute to either damage to local ecology or natural disasters. This shows that despite Beijing’s commitment to the green, energy-efficient, and environment-friendly BRI, the reality is quite the contrary. Chinese firms under the umbrella of BRI continue to finance the fossil fuel projects resulting in high emissions development for the BRI partners. Studies claim that BRI countries will contribute sixty percent of total GHG emissions by 2060. This grim statistic stands in contrast to China’s claims about “green BRI” (Hilton, 2019).

9. The Way Forward

The BRI is an economic endeavor first and foremost; however, major policy and practice changes can transform the project into a global platform for environmental protection. The most sweeping changes necessary to achieve this feat include:

9.1. Invest in Renewable Energy

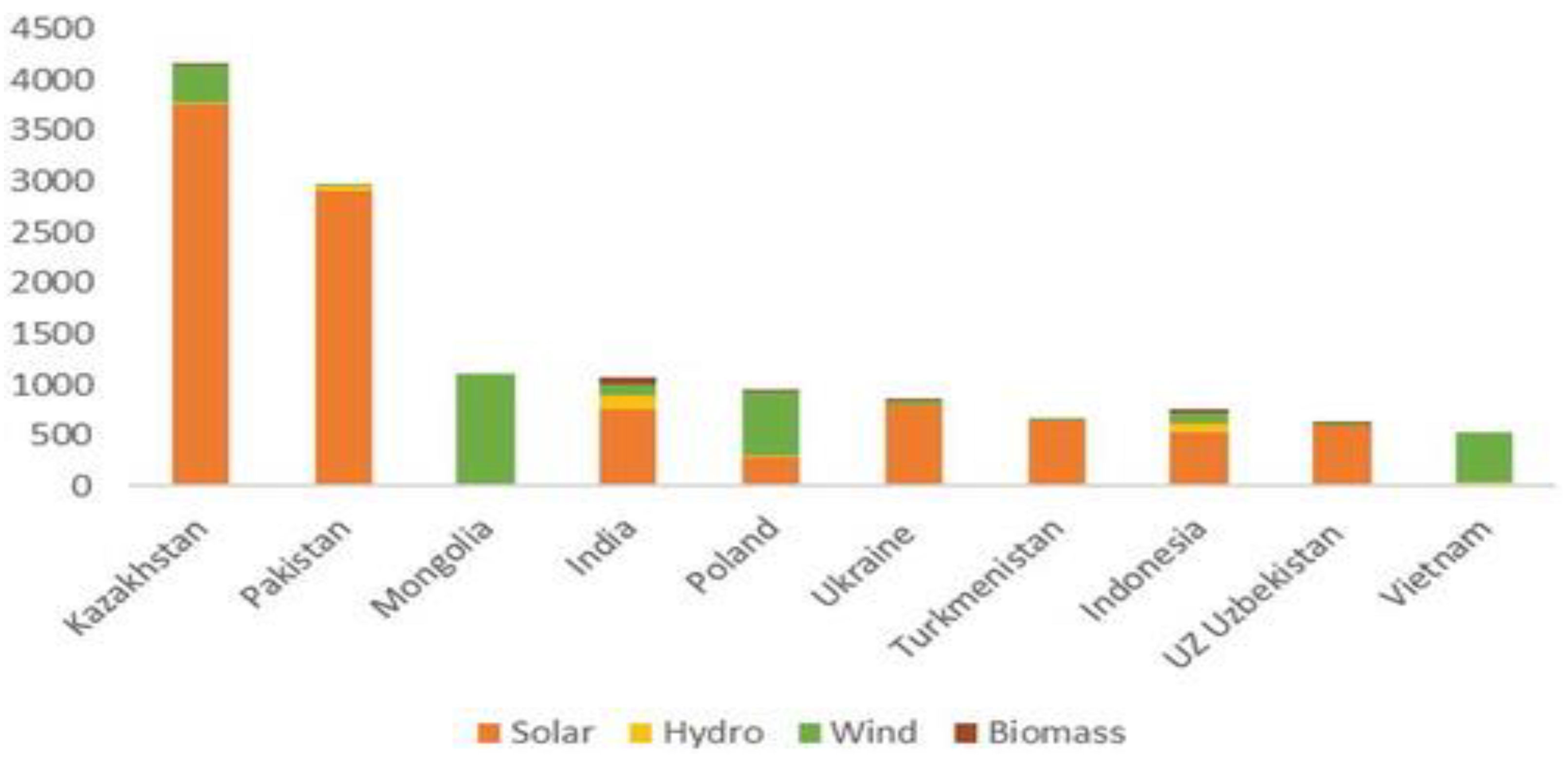

Renewable energy is a great source to protect the environment and mitigate the harmful effects of industrialization and infrastructure development. Renewable energy produces zero GHG emissions and generally consists of solar, wind, and hydropower projects. Moreover, unlike fossil fuels, renewable energy sources make no contribution to air pollution. BRI countries are predicted to contribute to sixty percent of global GHG emissions if the current rate and extent of policies continue. BRI’s current investment towards renewable resources is a mere twenty percent, while the existing infrastructure projects are funded by fossil fuels. BRI countries are abundant in renewable energy resources.

Figure 7.

The graph shows the capacity of energy projects in BRI countries (Gu, 2020).

Figure 7.

The graph shows the capacity of energy projects in BRI countries (Gu, 2020).

If China makes a gradual shift from fossil fuel to renewable energy resources, a reduction in GHG emissions can be achieved. China’s coal energy is considered to be inefficient and unsustainable. Renewable energy will not only benefit the environment but also prove advantageous for China’s economic interests in the long run as it is a sustainable source of energy. According to a study titled, "Emission reduction effects of the green energy investment projects of China in Belt and Road Initiative Countries", China’s renewable energy investment in the BRI stands at thirty-six projects. These projects will reduce global GHG emissions by 48.69 MtCO2, meaning a global reduction of 0.6% in emissions. Renewable energy makes up only twenty percent of BRI energy-related projects. If a larger investment is made towards Solar and Wind power plants, the BRI countries could cap their GHG emissions (Gu, 2020). Another study suggests that solar energy alone could generate 448.9 petawatt hours of electricity every year, which is approximately forty times the region’s electricity demand in 2016. The electricity needs of the entire region could be fulfilled a few times over by 2030 only if an investment in solar energy is made. Even if the BRI partner countries manage to generate only thirty percent of their total electricity demand by using solar power, a massive 2.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide is saved, resulting in a 7.2% reduction in global carbon emissions. Hence China should invest in renewable energy instead of fossil fuels. Not only is this type of energy sustainable and environment friendly it will also cap the GHG emissions of BRI countries and contribute towards the provisions of the Paris Agreement (Logan, 2019). Priority should be given to renewable energy projects with income stability. Chinese advanced technology is a great instrument for middle and low-income BRI countries. This way, Chinese products can also find a market in the BRI countries.

9.2. Build Eco-Friendly Low Carbon SEZs

SEZs are the most important drivers of industrialization in the BRI partner countries. China’s own economic growth and rapid industrialization are attributed to the Special Economic Zones. There are various types of SEZs though all are aimed at initiating industrialization and are usually carbon-intensive as most industrial activities powered by fossil fuels are. The BRI SEZs follow the pattern of the typical SEZs implemented in China. As early as 2003, Eco-Industrial Parks (EIP) and Low Carbon Industrial Parks (LCIP) made an appearance. These two types of SEZs are eco-friendly with low carbon restructuring of the SEZs. The LCIP initiative focuses on low-carbon development in all aspects of urban infrastructure. The Chinese SEZs are gradually transitioning towards green and low-carbon SEZs (Kim, 2017). The low-intensity carbon SEZs can drive a low-carbon development strategy.

Figure 8.

Information regarding the low-intensity carbon SEZs and their benefits (Farole, 2011).

Figure 8.

Information regarding the low-intensity carbon SEZs and their benefits (Farole, 2011).

The infrastructure built under the green SEZs is directed at reducing carbon emissions. Green buildings and waste recycling is a part of low carbon infrastructure. In the short term, low-carbon infrastructure and SEZs could be expensive in terms of construction costs but profitable in terms of energy costs. For example, the construction cost of low-carbon development in China would be ten percent higher than the normal cost; however, the energy cost would be fifty percent less. Renewable energy is the most critical part of the low-carbon SEZs. It is impossible to run a low-carbon SEZ with fossil fuels as an energy source (Farole, 2011) e.

Low carbon SEZs along with being environmentally conscious and sustainable, are also investment friendly, a sentiment acknowledged by UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2010. Multinational corporations demonstrated a trend towards sustainable energy, such as the BP Solar program in India, Archer Daniels Midland in Brazil, and Cemsa in China, to name a few (Farole, 2011). The BRI SEZs are mostly powered by fossil fuels, particularly coal-fired plants. A number of BRI countries possess remarkable renewable energy resources. Pakistan, along with other South Asian BRI partners, is abundant in solar energy. Solar energy could fuel the low-carbon SEZs in Pakistan. Other encompassing efforts could include efficient buildings.

The BRI authorities could enforce mechanisms such as green building codes to ensure energy-efficient infrastructural development and reduce carbon emissions. Water reuse policies could be implemented within the framework of SEZs, resulting in a reduction of water pollution.

9.3. Enforce Climate Change Regulations and Policies

China has issued guidelines for a green BRI encompassing provisions for sustainable energy and other practices to protect agriculture, local ecological habitat, biodiversity, and forests. The guidelines are, however, voluntary. The document titled “Guidance on Promoting Green Belt and Road” outlines a number of critical measures to protect the environment. The Chinese government, in collaboration with its BRI partner, should enforce these guidelines as a binding document. Furthermore, these guidelines, including other documents detailing voluntary environment-preserving policies, are mainly focused on China’s large State-Owned Enterprises. The private firms generally consisting of small and medium enterprises are ignored in environmental policies. A large number of medium and small enterprises are engaged in BRI projects. Overlooking their environmental practices will override any efforts on China’s part (Teo, 2019).

These guidelines, if implemented, will transform the BRI into the biggest global climate change initiative. China domestically placed “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Environmental Impact Assessment”. This law assesses the environmental policies and impacts of the Chinese state and private enterprises. The investors are liable to pay for damages to the environment. In 2013, voluntary guidelines titled “Guidelines on Environmental Protection for Overseas Investment and Cooperation" were placed. The guideline calls for developing provisions that mitigate environmental threats, and risks to local ecosystems and cooperation with local communities to assess the environmental issues. The guideline is voluntary, unlike the domestic environmental assessment. The Chinese government should direct the investors to consider country-wise NDCs when planning and developing a BRI project. Major global banks have already incorporated NDCs, environmental safety measures, and commitment to low-carbon development. The World Bank and AIIB already have environmental safety measures in place; Chinese state-owned enterprises and medium and small private businesses investing in the BRI should be required to incorporate similar measures. All BRI partners developed national NDCs accept Syria. The BRI member states should update their NDCs with defined strategies so that investors can redesign their own strategies around the national NDCs (Walker, 2018).

9.4. Establish Protected Areas for the Protection of Biodiversity and Ecosystems

To protect biodiversity and local ecosystems along the BRI route, Chinese investors should develop a mechanism to collaborate with the locals regarding potential environmental threats. The issue of the Myitsone dam project in Vietnam underscores the importance of local involvement in the BRI projects. Prior to any BRI infrastructural project, a detailed environmental assessment should be carried out. If the long-term environmental threats outweigh the short-term economic goals, the project should not even kick off the planning stage. To protect biodiversity, the biodiversity endemism hotspots or umbrella species framework should be utilized. Measures should be taken to mitigate the effects on key biodiversity areas along the BRI routes. Protected areas should be established along the BRI route as mitigation strategies against the threat to biodiversity and endangered species. The protected areas will also result in protection from deforestation. A mitigation hierarchy framework, along with the umbrella species framework, could be used to protect the endangered species. Once the endangered species’ habitat is identified, no infrastructure project, including roads and railways, should be established within a few kilometers of their range (Pfaf, 2019).

10. Data Analysis and Results of the Study

Table 9 shows the demographic and their relevant details. A minimum of 20 years of age, participants provided their consent, while participants above 40 years also participated. The participants were from 3 different domains, i.e., University Faculty 23 %, Politicians (47%), and Field Experts (30 %) with M=2.07, and SD=073. The respondents were between 20 above 40 age. Among the participants, 78(23%) were BA/BSc, 152 (46.1) % were Masters, and 100 (30.3 %) were MPhil and PhD.

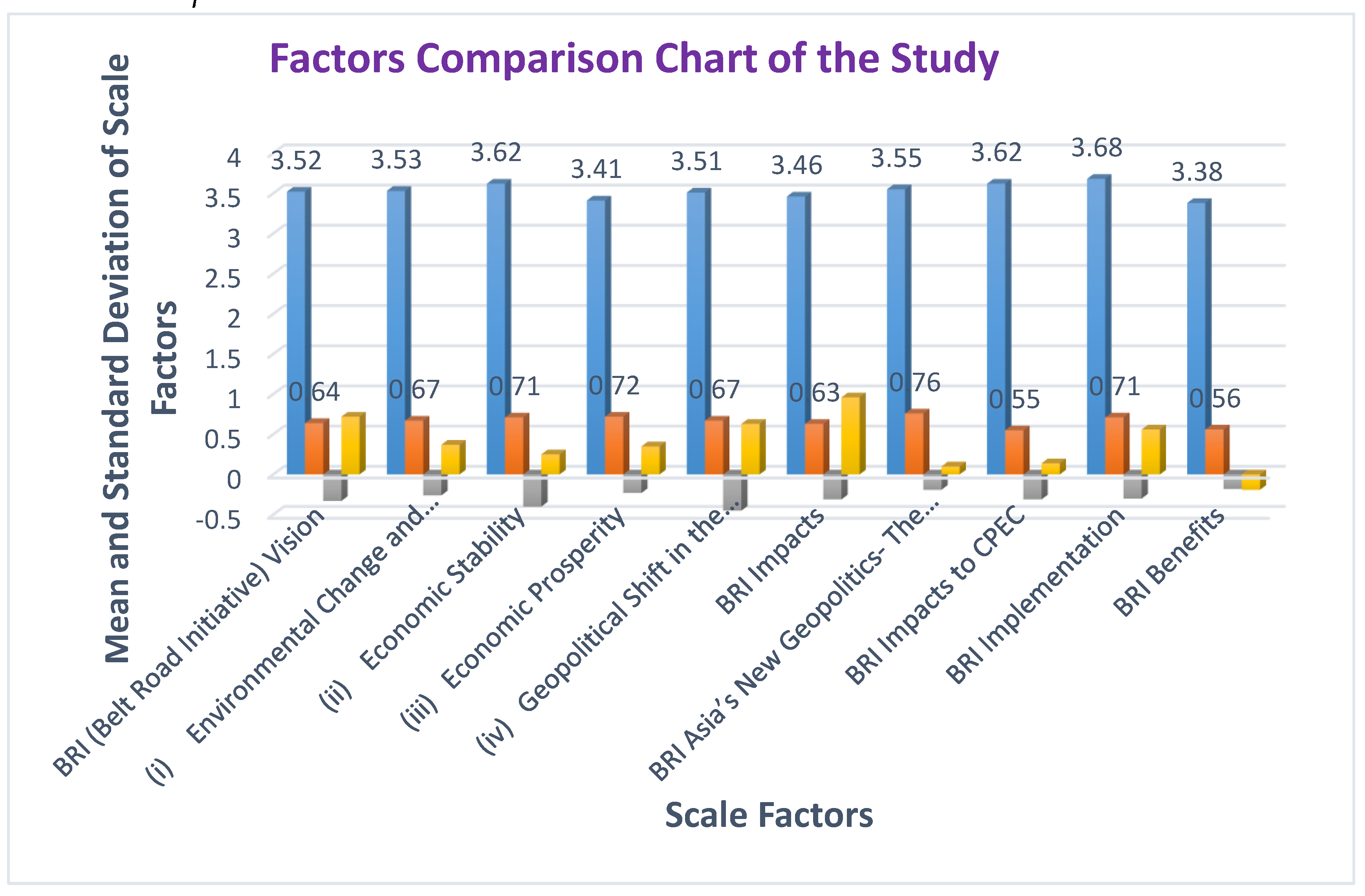

Table 3 shows the reliability statistics of scale factors with the sub-factors. It shows that BRI (Belt Road Initiative) contains 4 sub-factors, i.e., (i) Environmental Change and Development, (ii) Economic Stability, (iii) Economic Prosperity, and (iv) Geopolitical Shift in the region with their acceptable reliability value. Overall, the scale includes six main factors, i.e., BRI (Belt Road Initiative) Vision, BRI Impacts, BRI Asia’s New, Geopolitics- The Sino-Pak Context, BRI Impacts on CPEC, BRI Implementation, and BRI Benefits. The overall reliability of the scale was 0.906. It was found that the scale was reliable for use.

Table 11.

Mean and SD and Other Specifications of the Scale Factors (N=380).

Table 11.

Mean and SD and Other Specifications of the Scale Factors (N=380).

| Scale Factors |

M |

SD |

Skew |

Kurt |

| BRI (Belt Road Initiative) Vision |

3.52 |

0.64 |

-0.33 |

0.72 |

| (i) Environmental Change and Development |

3.53 |

0.67 |

-0.26 |

0.37 |

| (ii) Economic Stability |

3.62 |

0.71 |

-0.40 |

0.25 |

| (iii) Economic Prosperity |

3.41 |

0.72 |

-0.23 |

0.35 |

| (iv) Geopolitical Shift in the Region |

3.51 |

0.67 |

-0.45 |

0.63 |

| BRI Impacts |

3.46 |

0.63 |

-0.31 |

0.96 |

| BRI Asia’s New Geopolitics- The Sino-Pak Context |

3.55 |

0.76 |

-0.19 |

0.10 |

| BRI Impacts to CPEC |

3.62 |

0.55 |

-0.31 |

0.14 |

| BRI Implementation |

3.68 |

0.71 |

-0.30 |

0.56 |

| BRI Benefits to the Environment |

3.38 |

0.56 |

-0.18 |

-0.19 |

| Total |

58 |

0.906 |

Table 3 shows the

Mean and SD with Other Specifications of the Scale Factors. The study had 6 factors, including the 4 sub-factors to the factor BRI Vision (M=3.52, SD=0.64) out of 6 factors. The other 5 factors are BRI Impacts, BRI Asia’s New Geopolitics- The Sino-Pak Context, BRI Impacts on CPEC, BRI Implementation, and BRI Benefits. The participation of each of the factors in the study was denoted using

Chart 1:

Factors Comparison Chart of the Study.

Chart 1 of

Table 3 shows that factors "BRI Impacts to CPEC" (M= 3.62, SD=0.55), and "BRI Implementation" (M= 3.68, SD=0.71), with the sub-factor “Economic Prosperity” related to the factor “BRI Vision” possesses the higher means as compared to the other factors of the study. While the factor "BRI Benefits" (M=3.38, SD=0.56) has the lowest mean. All the factors show good mean values showing acceptable ratios. It was concluded that the BRI vision included with "BRI Asia’s New Geopolitics- The Sino-Pak Context", "BRI Impacts to CPEC", and "BRI Implementation" has better future concerns regarding the success of the BRI project as it was planned. But taking the BRI benefits, the study results show some concerns because of several other reasons like security aspects, the BRI country’s cooperation, and the environmental threats, which can hinder the way to progress of the Belt Road Initiative. Anyhow, if the BRI project is handled properly taking care of all the security concerns and other alarming factors, BRI could be beneficial to the BRI countries/ Eurasia regarding several concerns, specifically in perspectives like (i)Environmental Change and Development, (ii) Economic Stability, (iii) Economic Prosperity and (iv) Geopolitical Shift in the Region. Whatever the circumstances may arise in the future, the BRI can be beneficial to the South Asian region.

Table 12.

Relationship between BRI Vision and Implementation w.r.t its Environment (N=330).

Table 12.

Relationship between BRI Vision and Implementation w.r.t its Environment (N=330).

| Measures |

M |

SD |

r |

Sig. |

BRI Vision

BRI Implementation |

3.52

3.46 |

0.635

0.623 |

0.774** |

0.000 |

Table 5 shows the correlation statistics between the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) Vision and the BRI Implementation with respect to its environment. There was a strong significant positive correlation between the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) Vision and the BRI Implementation regarding the BRI project compatibility with the environment aroused through BRI (r=0.557, p=0.000). The more the BRI Vision, the better it will be its implementation for China-Pakistan and other countries joining hands in the BRI project. Resultantly, with the strong correlation of BRI Vision with its implementation, the BRI environment will improve which will develop the economy of the countries joined together in the BRI project. The hypothesis was rejected. So, BRI Vision is fully significant in relation to its implementation.

Table 13.

Effect of BRI Environment over BRI Implementation.

Table 13.

Effect of BRI Environment over BRI Implementation.

| Variables |

Unstandardized Co-efficient

|

Standardized Co-efficient

|

|

| (Model) |

B |

Std. Error Β

|

β |

t |

F |

df |

P |

R2 |

| Constant |

.785 |

.125 |

.778 |

6.29 |

124.97 |

325 |

0.000 |

0.606 |

| Environmental Change and Development |

.252 |

.070 |

.268 |

3.589 |

|

|

.000 |

|

| Environmental Stability |

.056 |

.055 |

.063 |

1.014 |

|

|

.311 |

|

| Economic Prosperity |

.184 |

.062 |

.212 |

2.947 |

|

|

.003 |

|

| Geopolitical Stability |

.275 |

.064 |

.294 |

4.262 |

|

|

.000 |

|

Table 6 shows the Effect of the BRI Environment on its implementation. The results of linear regression analysis show that there was a significant effect of BRI Environment over its implementation as shown in Table 5 [(R2 = 0.606) at p≤0.000 level of significance]. The findings of the study interpret that the factor “Environmental Change and Development” (β = .252, F=124.97, p= 0.000) predicted 25%, “Economic Prosperity” (β = .184, p= 0.003) predicted 18%, and “Geopolitical Stability” (β = .275, p= 0.000) predicted the BRI implementation up to 27%. The overall model was fully fit (R2 = 0.606, F=167.08, p=0.000). It was concluded that Environmental Change and Development, Economic Prosperity, and Geopolitical Stability were the predictors of BRI implementation, while Environmental Stability was not the predictor of BRI implementation, which means the BRI project can have concerns regarding environmental stability, i.e., security concerns, BRI-countries cooperation, and other factors.

Table 14.

Effect of BRI Impacts on the Environment of the Eurasian Region.

Table 14.

Effect of BRI Impacts on the Environment of the Eurasian Region.

| |

Unstandardized Co-efficient

|

Standardized Co-efficient

|

|

| Model |

B |

Std. Error Β

|

β |

t |

F |

df |

P |

R2 |

| Constant |

.785 |

.125 |

|

6.286 |

124.97 |

325 |

0.000 |

0.606 |

| Environmental Change and Development |

.252 |

.070 |

.268 |

3.589 |

|

|

.000 |

|

| Environmental Stability |

.056 |

.055 |

.063 |

1.014 |

|

|

.000 |

|

| Economic Prosperity |

.184 |

.062 |

.212 |

2.947 |

|

|

.311 |

|

| Geopolitical Stability |

.275 |

.064 |

.294 |

4.262 |

|

|

.003 |

|

Table 7 shows the Effect of the BRI Environment on its implementation. The results of linear regression analysis show that there was a significant effect of BRI Environment over its implementation as shown in Table 5 [(R2 = 0.606) at p≤0.000 level of significance]. The findings of the study interpret that the factor “Environmental Change and Development” (β = .252, F=124.97, p= 0.000) predicted 25%, “Economic Prosperity” (β = .184, p= 0.003) predicted 18 %, and “Geopolitical Stability” (β = .275, p= 0.000) predicted the BRI implementation up to 28%. The overall model was fully fit (R2 = 0.606, F=124.97, p=0.000). It was concluded that Environmental Change and Development, Economic Prosperity, and Geopolitical Stability were the predictors of the BRI Environment, while Environmental Stability (β = 0.056, p= 0.311) was not the predictor of BRI implementation, which means the BRI project can have concerns regarding environmental stability, i.e., security concerns, BRI-countries cooperation, and other factors.

11. Discussions

Multiple economic benefits to BRI integrate countries at their economic prosperity exposure primarily appear in goods trade, resources, and services, facilitated through the reduced cost of transportation including different trade barriers (Villafuerte et al., 2016) services and resources, facilitated reduced transportation costs and other trade barriers. BRI projects are aimed at increasing the total exports of 46 countries of BRI-chain by "$5 billion to $135 billion" and having an appealing GDP of 0.3 to 1.4 percent. A lot of factors affect the Belt Road Initiative taken by taken in the form of a development project that can change the destiny of developing countries like Pakistan joined it. The first objective of the study is to investigate the nature of the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) vision to develop the environment of the South Asian region with four different perspectives, i.e., (i) Environmental Change and Development, (ii) Economic Stability, (iii) Economic Prosperity and (iv) Geopolitical Shift in the Region. It was found that the factor “Economic Stability” gained the highest Mean value (i.e. M=3.62, SD=0.71), while the factor “Economic Prosperity” showed the lowest Mean (M=3.41, SD=0.72) value among these factors. These statistics reveal that all four perspectives that cover BRI Vision, in general, need attention regarding economic prosperity. At the same time, it was also clear from the results that the BRI project shows good results in economic stability. Hence, economic stability leads to economic prosperity. The factors "Environmental Change and Development" and "Geopolitical Shift in the Region" gained the average mean value depicting that the BRI project no doubt aims at the prosperity of the South Asian Region, yet the “Environmental Change and Development” and “Geopolitical Shift in the Region” are also very important in relation to the development of the region in the context of BRI project success.

Secondly, the study was to investigate the relationship between BRI vision and implementation. A strong significant positive correlation was found between the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) Vision and the BRI Implementation regarding the BRI project compatibility with the environment aroused through BRI (r=0.557, p=0.000). The study suggested that the more the BRI Vision, the better it will be its implementation for China-Pakistan and other countries joining hands in the BRI project.

The third research question aimed at exploring strong predictors of the BRI environment in relation to its implementation. Predictable environmental impacts can be caused by BRI at a huge scale with intensity. Several actors with numerous political, administrative, social, and administrative scales (concerning national and international) are likely to play a moderating role in maintaining such environmental impacts (Guttman et al., 2018). The study measured the impact of four environmental factors of BRI, being the predictors of BRI implementation: Environmental Change and Development, Environmental Stability, Economic Prosperity, and Geopolitical Stability. It was found that "Environmental Change and Development, Economic Prosperity, and Geopolitical Stability" were the predictors of the BRI Environment, while the Environmental Stability (β = 0.056, p= 0.311) was not the predictor of BRI implementation, which means the BRI project can have concerns regarding environmental stability, i.e., security concerns, BRI-countries cooperation, and other factors.

Regarding the fourth question of the study, the study found the BRI project impacts predicting the Eurasian environment in relation to the BRI project completion. Again the factor "economic stability" was found insignificant, referring to the security and other related concerns to the successful completion of the BRI project. So, the BRI project plays a vast and valuable role in affecting the Eurasian environment from several perspectives.

12. Conclusions

The BRI is an instrument of economic growth and prosperity for China as well as the BRI partner countries. The project seeks to revive the centuries-old Silk Road; BRI infrastructural projects not only connect the member states along the old Silk Road but also enable the industrialization of the member countries. The BRI is mainly concentrated in the middle and low-income countries except for Oceanic countries, Israel, and oil-rich Gulf states. Low and middle-income countries usually have weaker environmental regulations and, in exchange for economic advantages, are more susceptible to accepting long-term environmental damages. BRI Vision and its implementation regarding the BRI project compatibility with the environment. It was also found that Environmental Change and Development, Economic Prosperity, and Geopolitical Stability were the predictors of BRI implementation, while, Environmental Stability was not the predictor of BRI implementation, which means the BRI project can have concerns regarding environmental stability, i.e., security concerns, BRI-countries cooperation, and other factors. BRI infrastructure projects will result in fossil fuel-dependent development. Along with the use of carbon-intensive industrial practices, China’s rail and road projects, particularly those developed in synergy with the six economic corridors, are likely to cause massive deforestation, particularly in the Southeast Asian region. Deforestation causes a number of direct and indirect impacts such as the loss of local ecosystems, natural disasters as well as loss of the mechanism that diffuses carbon dioxide from the environment.

References

-

Special Economic Zones. (2020). Retrieved 04 20, 2021, from Ministry of Planning Development and Special Initiatives: http://cpec.gov.pk/project-details/67.

- Abdelhak Senadjki, I. M. (2022). The Belt and road initiative (BRI): A mechanism to achieve the ninth sustainable development goal (SDG). ScienceDirect.

- Ahmed, W. (2020). Sustainable and Special Economic Zone Selection. Symmetry.

- Arif, A. (2019). Politics of Economic Corridors in South Asia. Institute of Strategic Studies.

- Barone, A. (2020, September 30). Special Economic Zones. Retrieved from Investopedia : https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/sez.asp#:~:text=Key%20Takeaways-,A%20special%20economic%20zone%20(SEZ)%20is%20an%20area%20in%20a,foreign%20direct%20investment%20(FDI).

- Belt and Road Initiative. (2020). Belt and Road Initiatives. Retrieved April 18, 2021, from BRI: https://www.beltroad-initiative.com/belt-and-road/.

- Climate Action Tracker. (2020). President Xi Jinping announced in September 2020 that China will strengthen its 2030 climate target. CAT.

- Dasgupta, S. (2019, Feb 5). China’s Belt and Road Initiative could increase alien species invasion. Retrieved from Mongabay: https://news.mongabay.com/2019/02/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-could-increase-alien-species-invasion/.

- Derudder, B. (2018). Connecting along overland corridors of the Belt and Road Initiative. MIT Global Practice.

- Dyer, H. (2018, Jan 7). Introducing Green Theory in International Relations. Retrieved from E International Relations: https://www.e-ir.info/2018/01/07/green-theory-in-international-relations/.

- Eder, T. S. (2019). Powering the Belt and Road. MERICS.

- Environmental and Energy Study Institute. (2018). Exploring the Environmental Repercussions of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. EESI.

- Eunice Jieun Kim. (2017). China’s Green Special Economic Zone Policies —Development and implementation. Global Green Growth Institute.

- Farole, T. (2011). Special Economic Zones. World Bank.

- Farole, T. (2011). Special Economic Zones: Progress, emerging challenges, and future directions. World Bank.

- Geopolitical monitor. (2020, September 3 ). Belt and Road: China-Mongolia-Russia Corridor. Geopolitical monitor.

- Ghani, S. (2019). Industrialization and SEZs are hallmarks of BRI & CPEC. The South Asian Strategic Stability Institute.

- Gu, A. (2020). Emission reduction effects of green energy. Ecosystem health and sustainability.

- Hao, W. (2020). The Impact of Energy Cooperation and the Role of the One Belt and Road Initiative in Revolutionizing the Geopolitics of Energy among Regional Economic Powers: An Analysis of Infrastructure Development and Project Management. Hindawi.

- Hillman, J. (2021). The Climate Challenge and China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Council on Foreign Relations.

- Hilton, I. (2019). How China’s Big Overseas Initiative Threatens Global Climate Progress. Yale School of Environment.

- Hong, C. S. (2018). Mapping potential climate and development impacts of China’s Belt and Road Initiative::. Stockholm Environment Institute.

- Hou, J. (2020). A global analysis of CO2 and non-CO2 GHG emissions embodied in trade with Belt and Road. Ecosystem health and sustainability.

- Hughes, A. C. (2019). Understanding and minimizing the environment. Conservation Biology.

- Kai, P. (2017, March 22). UNDERSTANDING CHINA’S BELT AND ROAD INITIATIVE. Retrieved April 15, 2021, from Lowi Institute: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/understanding-belt-and-road-initiative.

- Khan, A. (2019). Does energy consumption, financial development, and investment contribute to ecological footprints in BRI regions? Environmental Science and Pollution Research.

- Khan, D. K. (2018). Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and CPEC: Background, Challenges and Strategies. The Pakistan Development Review.

- Li, X. (2017, November ). Green Development under Belt and Road Initiative: Pushing Forward the Global. Belt and Road Green Development Partnership. Bonn, Germany.

- Logan, K. G. (2019). Solar power could stop China’s Belt and Road Initiative from unleashing huge carbon emissions. The Conversation.

- Losos, E. (2019). The deforestation risks of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Brookings Institute.

- Maliszewska, M. (2019). The Belt and Road Initiative: Economic, Poverty and Environmental Impacts. World Bank Working Paper.

- Mullins, M. T. (2017). Dancing to China’s Tune: Understanding the Impacts of a Rising China through the Political-Ecology Framework. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs.

- Nunez, C. (2019, april 02). WHAT ARE FOSSIL FUELS? National Geographic.

- OECD. (2018). China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape. OECD.

- Petrella, S. (2018, March 27). What is an economic corridor? Retrieved April 19, 2021, from Reconnecting Asia: https://reconnectingasia.csis.org/analysis/entries/what-economic-corridor/.

- Pfaff, A. (2019). Reducing Environmental Risks from Belt and Road Initiative Investments. Policy Research Working Paper.

- Ruta, M. (2019). BELT AND ROAD ECONOMICS. Washington DC: World Bank. License: Creative Commons Attribution.

- Sarker, M. N. (2018). One Belt One Road Initiative of China: Implication for Future of Global Development. Scientific Research.

- Teo, H. C. (2019). Environmental Impacts of Infrastructure Development under the Belt and Road Initiative. Environments.

- Valentine, R. (2020, dec 1). Indonesia Needs to be Careful for Environmental Destruction Caused by the BRI. Retrieved from World News: https://intpolicydigest.org/indonesia-needs-to-be-careful-for-environmental-destruction-caused-by-the-bri/.

- Walker, B. (2018, November 21). China’s Belt and Road Initiative will make or break the global climate fight. Retrieved from The Pole: https://www.thethirdpole.net/en/energy/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-will-make-or-break-global-climate-fight/.

- Xian-Chun Tan, K.-W. Z.-L.-Y. (2021). Bibliometric research on the development of climate change in the BRI regions. Science Direct.

- Zdek, S. (2019). The critical frontier: Reducing emissions from China’s Belt and Road. Brookings Institute.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).