Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gerritsen, A.E.; Allen, P.F.; Witter, D.J.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Creugers, N.H. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiapasco M Casentini, P. Zaniboni M. Bone augmentation procedures in implant dentistrry. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Implants. 2009, 24, 237–259. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen, A.E.; Allen, P.F.; Witter, D.J.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Creugers, N.H. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobuto, T.; Imai, H.; Suwa, F.; Kono, T.; Suga, H.; Jyoshi, K.; Obayashi, K. Microvascular response in the periodontal ligament following mucoperiosteal flap surgery. J Periodontol. 2003, 74, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botticelli, D.; Berglundh, T.; Lindhe, J. Hard-tissue alterations following immediate implant placement in extraction sites. J Clin Periodontol 2004, 31, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minetti, E.; Celko, M.; Contessi, M.; Carini, F.; Gambardella, U.; Giacometti, E.; Santillana, J.; Beca Campoy, T.; Schmitz, J.H.; Libertucci, M.; Ho, H.; Haan, S.; Mastrangelo, F. Implants Survival Rate in Regenerated Sites with Innovative Graft Biomaterials: 1 Year Follow-Up. Materials 2021, 14, 5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tulio, A.V.; Kang, C.D.; Fabian, O.A.; Kim, G.E.; Kim, H.G.; Sohn, D.S. Socket preservation using demineralized tooth graft: A case series report with histological analysis. Int J Growth Factors Stem Cells Dent 2020, 3, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Menchini-Fabris, G.B.; Cosola, S.; Toti, P.; Hwan Hwang, M.; Crespi, R.; Covani, U. Immediate Implant and Customized Healing Abutment for a Periodontally Compromised Socket: 1-Year Follow-Up Retrospective Evaluation. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dhadse, P.V.; Yeltiwar, R.K.; Bhongade, M.L.; Pendor, S.D. Soft tissue expansion before vertical ridge augmentation: Inflatable silicone balloons or self-filling osmotic tissue expanders? J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014, 18, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, R.N.; Tandon, S.; Singh, A.K.; Bhattacharjee, B.; Pandey, S.; Chirakkattu, T. Sandwich osteotomy with interpositional grafts for vertical augmentation of the mandible: A meta-analysis. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2022, 13, 347–356, Khoury F, Hanser T. Mandibular bone block harvesting from the retromolar region: a 10-year prospective clinical study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2015, 30, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Urban, I.A.; Lozada, J.L.; Wessing, B.; Suárez-López del Amo, F.; Wang, H.L. Vertical bone grafting and periosteal vertical mattress suture for the fixation of resorbable membranes and stabilization of particulate grafts in horizontal guided bone regeneration to achieve more predictable results: a technical report. Int J Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2016, 36, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, S.; Levin, L. Human Studies of Vertical and Horizontal Alveolar Ridge Augmentation Comparing Different Types of Bone Graft Materials: A Systematic Review. J Oral Implantol. 2018, 44, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekry, Y.E.; Mahmoud, N.R. Vertical ridge augmentation of atrophic posterior mandible with corticocancellous onlay symphysis graft versus sandwich technique: clinical and radiographic analysis. Odontology. 2023, 111, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sáez-Alcaide, L.M.; González Gallego, B.; Fernando Moreno, J.; Moreno Navarro, M.; Cobo-Vázquez, C.; Cortés-Bretón Brinkmann, J.; Meniz-García, C. Complications associated with vertical bone augmentation techniques in implant dentistry: A systematic review of clinical studies published in the last ten years. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023, 124, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.E.; Shellenberger, T.; Wimsatt, J.; Correa, P. Severely resorbed mandible: predictable reconstruction with soft tissue matrix expansion (tent pole) grafts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002, 60, 878–888, discussion 888-889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, R.H.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, G.; Park, W.E.; Sohn, D.S. Simplified 3-dimensional ridge augmentation using a tenting abutment. Adv Dent & Oral Health 2020, 12, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, D.S.; Huang, B.; Kim, J.; Park, W.E.; Park, C.C.; et al. Utilization of autologous concentrated growth factors (CGF) enriched bone graft matrix (Sticky Bone) and CGF-enriched fibrin membrane in implant dentistry. J. Implant. Adv. Clin. Dent. 2015, 7, 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.H.; Choi, S.H.; Cho, K.S.; Lee, J.S. Dimensional alterations following vertical ridge augmentation using collagen membrane and three types of bone grafting materials: A retrospective observational study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2017, 19, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misch, C.M.; et al. Reconstruction of maxillary alveolar defects with mandibular symphysis grafts for dental implants; a preliminary procedural report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1992, 7, 360–366. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeeren, J.I.; Wismeijer, D.; van Waas, M.A. One-step reconstruction of the severely resorbed mandible with onlay bone grafts and endosteal implants. A 5-year follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996, 25, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbordone, L.; Toti, P.; Menchini-Fabris, G.B.; Sbordone, C.; Piombino, P.; Guidetti, F. Volume changes of autogenous bone grafts after alveolar ridge augmentation of atrophic maxillae and mandibles. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009, 38, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakkas, A.; Schramm, A.; Winter, K.W. Risk factors for post-operative complications after procedures for autologous bone augmentation from different donor sites. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018, 46, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Sánchez, I.; Sanz-Martín, I.; Ortiz-Vigón, A.; Molina, A.; Sanz, M. Complications in bone-grafting procedures: Classification and management. Periodontol 2022, 88, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiapasco, M.; Consolo, U.; Bianchi, A.; Ronchi, P. Alveolar distraction osteogenesis for the correction of vertically deficient edentulous ridges: a multicenter prospective study on humans. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004, 19, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melikov, E.A.; Dibirov, T.M.; Klipa, I.A.; Drobyshev, A.Y. Al'veolyarnyi distraktsionnyi osteogenez: vozmozhnye oslozhneniya i sposoby ikh ustraneniya [Alveolar distraction osteogenesis: possible complications and methods of their treatment]. Stomatologiia 2022, 101, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, F.; Hanser, T. Three-Dimensional Vertical Alveolar Ridge Augmentation in the Posterior Maxilla: A 10-year Clinical Study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2019, 34, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troeltzsch, M.; Troeltzsch, M.; Kauffmann, P.; Gruber, R.; Brockmeyer, P.; Moser, N.; Rau, A.; Schliephake, H. Clinical efficacy of grafting materials in alveolar ridge augmentation: A systematic review. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016, 44, 1618–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatos, N.K.; Stylianou, P.; Koidou, V.P.; Angelov, N.; Yukna, R.; Romanos, G.E. Limitations and options using resorbable versus nonresorbable membranes for successful guided bone regeneration. Quintessence Int. 2017, 48, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, I.A.; Montero, E.; Monje, A.; Sanz-Sánchez, I. Effectiveness of vertical ridge augmentation interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2019, 46, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchi, A.; Vignudelli, E.; Napolitano, A.; Marchetti, C.; Corinaldesi, G. Evaluation of complication rates and vertical bone gain after guided bone regeneration with non-resorbable membranes versus titanium meshes and resorbable membranes. A randomized clinical trial. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2017, 19, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Xie, Y.; et al. Hard tissue stability after guided bone regeneration: a comparison between digital titanium mesh and resorbable membrane. Int J Oral Sci 2021, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, B.; Rohrer, M.D.; Prasad, H.S. Screw "tent-pole" grafting technique for reconstruction of large vertical alveolar ridge defects using human mineralized allograft for implant site preparation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010, 68, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daga, D.; Mehrotra, D.; Mohammad, S.; Singh, G.; Natu, S.M. Tent pole technique for bone regeneration in vertically deficient alveolar ridges: A review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2015, 5, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeb, G.R.; Tran, D.; Carrico, C.K.; Block, E.; Laskin, D.M.; Deeb, J.G. How Effective Is the Tent Screw Pole Technique Compared to Other Forms of Horizontal Ridge Augmentation? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017, 75, 2093–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenton, C.C.; Nish, I.A.; Carmichael, R.P.; Sàndor, G.K. Metastatic mandibular retinoblastoma in a child reconstructed with soft tissue matrix expansion grafting: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007, 65, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfro, R.; Batassini, F.; Bortoluzzi, M.C. Severely Resorbed Mandible Treated by Soft Tissue Matrix Expansion (Tent Pole) Grafts: Case Report, Implant Dentistry. 2008, 17, 408–413.

- Elnayef, B.; Monje, A.; Gargallo-Albiol, J.; Galindo-Moreno, P.; Wang, H.L.; Hernández-Alfaro, F. Vertical Ridge Augmentation in the Atrophic Mandible: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2017, 32, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.R.H.; Ng, E.; Lu, X.J.; Lai, W.M.C. Healing complications and their detrimental effects on bone gain in vertical-guided bone regeneration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2022, 24, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palkovics, D.; Solyom, E.; Somodi, K.; Pinter, C.; Windisch, P.; Bartha, F.; Molnar, B. Three-dimensional volumetric assessment of hard tissue alterations following horizontal guided bone regeneration using a split-thickness flap design: A case series. BMC Oral Health. 2023, 23, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, R.H.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, G.; Park, W.; Sohn, D. Simplified 3-Dimensional ridge augmentation using a tenting abutment. Adv Dent Oral Health 2020, 12, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, D.S. Reconstruction of three-dimensional alveolar ridge defects utilizing screws and implant abutments for the tent-pole grafting` techniques. In Tolstunov L, ed. Essential techniques of alveolar bone augmentation in implant dentistry, 2nd ed.; Wiley Blackwell: 2023; 404-418.

- Sohn, D.S.; Lui, A.; Choi, H. Utilization of Tenting Pole Abutments for the Reconstruction of Severely Resorbed Alveolar Bone: Technical Considerations and Case Series Reports. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

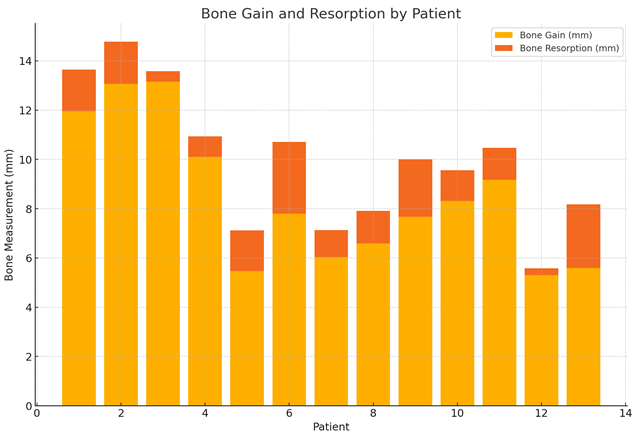

| Patient | Post-op height (mm) | Prosthetic Loading (mm, month) | Functional Loading (mm, month) | Bone Gain (mm) | Bone Resorption (mm) |

| 1 | 29.57 | 28.91(5m) | 27.87(11m) | 11.95 | 1.7 |

| 2 | 25.82 | 25.3(4m) | 24.1(8m) | 13.06 | 1.72 |

| 3 | 32.86 | 32.63(3m) | 32.43(8m) | 13.15 | 0.43 |

| 4 | 16.52 | 15.8(4m) | 15.68(16m) | 10.10 | 0.84 |

| 5 | 25.33 | 24.06(3m) | 23.68(14m) | 5.47 | 1.65 |

| 6 | 23.97 | 21.56(6m3w) | 21.06(18m) | 7.8 | 2.91 |

| 7 | 30.20 | 29.13(6m) | 29.1(10m) | 6.03 | 1.1 |

| 8 | 22.96 | 22.12(6m) | 21.64(20m) | 6.59 | 1.32 |

| 9 | 28.99 | 27.19(7m) | 26.65(13m) | 7.67 | 2.34 |

| 10 | 29.37 | 28.19(7m) | 28.13(20m) | 8.32 | 1.24 |

| 11 | 24.20 | 23.7(5m) | 22.9(8m) | 9.17 | 1.3 |

| 12 | 25.68 | 25.56(7m) | 25.4(16m) | 5.3 | 0.28 |

| 13 | 23.78 | 21.69(7m) | 21.19(19m) | 5.59 | 2.59 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).