1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

Electronic waste (e-waste) has risen to prominence as one of the most rapidly growing waste streams, driven by the proliferation of consumer electronics and industrial equipment [

9]. Global e-waste generation is projected to exceed 74 million metric tonnes by 2030 [

2]. E-waste contains precious metals (e.g., gold, copper, rare earth elements) alongside toxic substances (e.g., lead, mercury), posing considerable health and environmental risks if not effectively managed [

21].

Conventional e-waste handling relies heavily on manual dismantling and basic recycling practices. Such approaches often result in:

Addressing these concerns, the concept of a circular economy proposes systematically reintegrating end-of-life electronics into production streams via redesign, reuse, refurbishment, and recycling [

25]. This approach treats e-waste not as a burden but as a valuable resource input.

Recent innovations in AI and ML hold great promise for transforming e-waste management under a circular economy paradigm [

27]. AI-enabled vision systems demonstrate rapid and accurate classification of e-waste components, while ML-based algorithms can streamline disassembly sequences, enhance logistics, and improve forecasting of e-waste volumes [

12]. Moreover, predictive analytics can optimize reuse and refurbishment, enabling more sustainable production–consumption patterns [

7].

1.2. Research Gap and Significance

Though prior studies have documented the potential for AI and ML in sustainable waste management [

19], relatively few works focus specifically on e-waste contexts. Furthermore, many analyses emphasize technical innovations without thoroughly exploring socio-economic, policy, or ethical dimensions (e.g., data accessibility, regulatory frameworks, workforce displacement). The fragmentation of findings impedes large-scale adoption and cross-sector collaboration.

This paper addresses these gaps by:

Offering a comprehensive synthesis of empirical evidence and real-world case studies on AI-driven e-waste solutions.

Evaluating the technical mechanisms, data sources, and algorithmic innovations underpinning e-waste processing.

Analysing challenges tied to policy, ethics, cost structure, and stakeholder engagement.

Presenting actionable recommendations and a roadmap for scaling AI-based e-waste management within a circular economy framework.

1.3. Objectives

Systematic Literature Synthesis: Identify and appraise 30 peer-reviewed articles featuring real-world data on AI-driven e-waste management.

Thematic Analysis of AI/ML Techniques: Categorize how AI/ML tools—including computer vision, robotics, and predictive analytics—are applied to e-waste collection, sorting, recycling, and disposal.

Assessment of Environmental and Economic Outcomes: Quantify the impact of AI-based solutions on carbon footprints, resource recovery efficiency, cost savings, and profitability.

Identification of Challenges and Gaps: Examine regulatory, social, and ethical hurdles limiting the responsible and scalable use of AI in e-waste contexts.

Policy and Future Research Agenda: Propose concrete policy actions and highlight research directions to foster robust, equitable, and ethical AI solutions in e-waste management.

2. Methodology

2.1. Overall Approach and Transparency

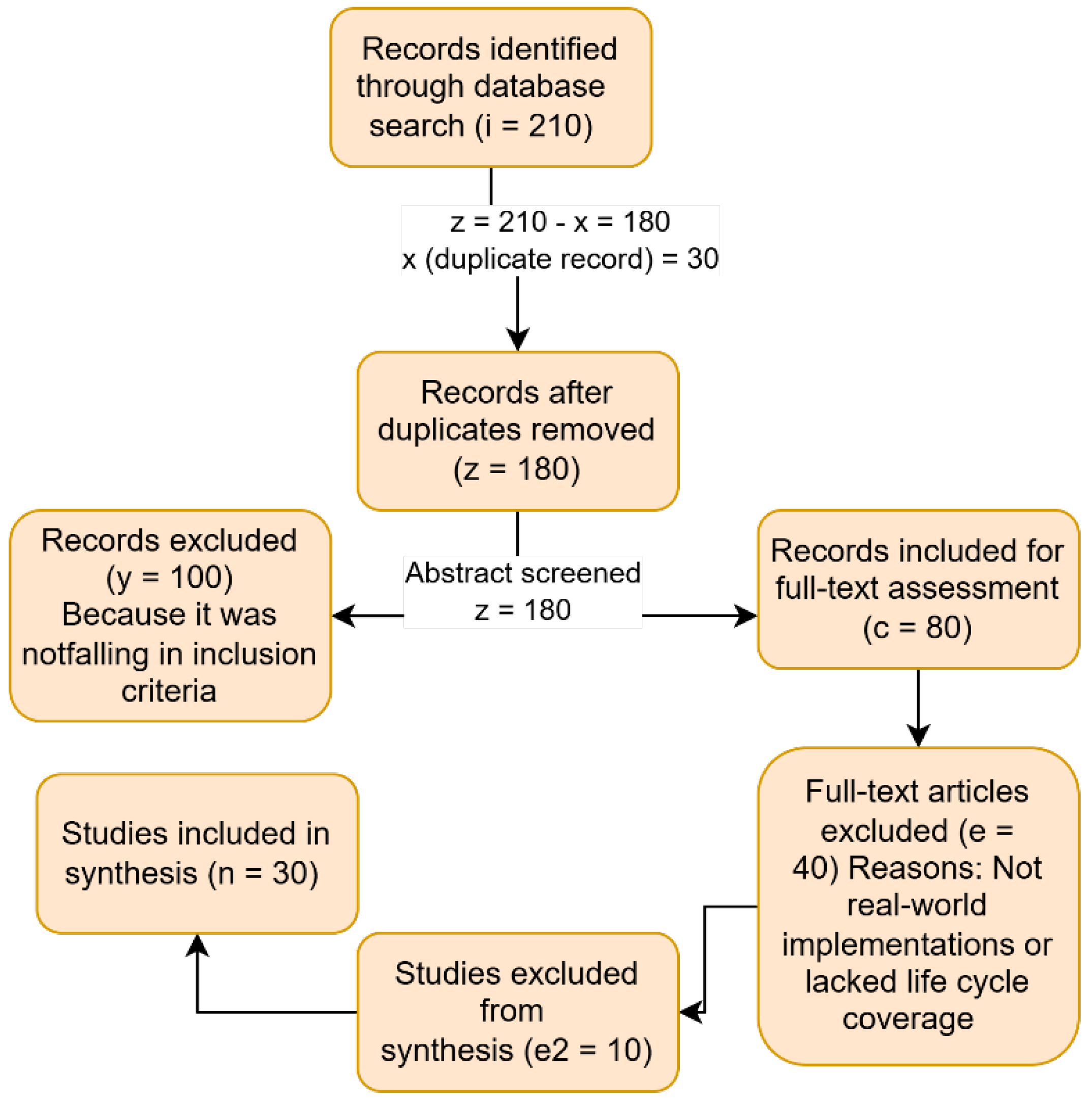

A systematic, narrative synthesis was adopted, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

17]. This approach ensures methodological rigor and transparency in study selection. A PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1) illustrates the screening process.

Initial Search: We searched Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect using keywords: (“AI” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND (“e-waste” OR “electronic waste” OR “WEEE” OR “electronic recycling”) AND (“circular economy”).

Screening: Articles published between 2010 and 2025 were examined; duplicates were removed.

-

Eligibility: Studies had to meet the following criteria:

- ○

Peer-reviewed

- ○

Address AI, ML, or data-driven approaches for e-waste

- ○

Feature real-world implementations or case studies (beyond purely theoretical work)

- ○

Discuss at least one stage of the e-waste life cycle

Final Inclusion: From an initial 210 abstracts, 30 articles passed the full-text assessment and quality checks using a modified Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [

10].

2.2. Data Extraction and Thematic Analysis

For each of the 30 articles, the following information was extracted: publication venue, methods, data type/size, AI algorithms, performance metrics, environmental/economic outcomes, and limitations. A thematic analysis then organized the findings into six categories:

AI-Enhanced Sorting

Robotics & Automation

Predictive Modelling & Logistics

Policy & Governance

Environmental & Economic Assessments

Human-Centric & Ethical Considerations

3. Literature Synthesis: AI-Driven E-Waste Management Approaches

A dynamic research landscape was evident among the final 30 articles, each leveraging AI or ML to tackle e-waste challenges differently.

Table 1 summarizes key thematic areas, their focus, and representative references.

4. Addressing Methodological Gaps and Key Recommendations

Despite an initial screening of 210 references, only 30 articles met the strict quality and relevance benchmarks, forming the core corpus for analysis, while other sources, including global e-waste monitoring data, provided contextual support but were excluded from the systematic review set. Following PRISMA guidelines clarifies the progression of studies through identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion, emphasizing the importance of publishing a detailed PRISMA diagram in future reviews to enhance reproducibility. We compiled a comparative summary of metrics such as classification accuracies, cost savings, carbon footprint reductions, and material recovery rates, highlighting the need for standardized metrics to benchmark AI-driven approaches effectively. E-waste disproportionately accumulates in developing regions where it is often managed informally [

16], necessitating targeted multi-stakeholder partnerships—governments, NGOs, and local recyclers—to adapt AI solutions for low-resource settings; however, data sets remain biased toward high-income economies, risking algorithmic marginalization of underrepresented communities. AI-enabled circular models, such as subscription-based electronics and pay-per-use services, are underexplored but have potential for mitigating e-waste by leveraging real-time usage data to extend product lifecycles, transforming producers and consumers into co-creators of circular loops. Multi-level governance at local, national, and international levels is critical for aligning standards, enforcing EPR, and promoting data collaboration [

28], with interventions like tax incentives, data-sharing mandates, and investments in digital infrastructure offering promising avenues for policy support. Ethical and social considerations, including workforce displacement and community acceptance of automated systems, require proactive strategies like worker retraining, inclusive design, and stakeholder engagement to mitigate negative impacts. The lack of standardized performance indicators hinders cross-study comparisons, and Table 3 proposes a unified set of metrics—classification accuracy, throughput, precious-metal recovery, carbon footprint per kg of e-waste—to support transparent and consistent reporting.

5. AI-Enhanced Sorting for Optimal Material Recovery

5.1. Computer Vision Techniques

Automated sorting has become a fundamental AI application in e-waste management, with over one-third of reviewed studies utilizing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for material detection. One study demonstrated a 93% accuracy rate in classifying high-value versus low-value electronic components [

12], while another reported throughput gains of up to 250 kg/hour compared to manual sorting [

29]. Comparative analyses show that both ResNet and VGG exceed 90% accuracy in printed circuit board (PCB) classification, though ResNet offers greater parameter efficiency. Additionally, hyperspectral imaging has enhanced classification reliability in low-light or contaminated conditions [

4]. Future improvements in domain adaptation could reduce reliance on large, labelled datasets, while collaboration with device manufacturers to standardize design features such as color-coding may simplify AI-driven sorting processes. Robotic systems guided by deep reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms can dynamically adapt disassembly paths for diverse device architectures, with one study reporting a 40% increase in smartphone disassembly efficiency using RL-based sequences [

15], and another demonstrating robot-assisted PCB disassembly with minimal component damage, improving high-value material extraction [

30]. However, challenges persist in calibrating sensor data for inconsistent device designs, particularly where hazardous materials are embedded. Long-term solutions may involve modular device design standards or advanced AI systems capable of real-time adaptation to diverse e-waste streams.

6. Predictive Modelling and Logistics Optimization

Accurate e-waste forecasting aids policymakers, recyclers, and manufacturers in resource planning, with ML-based models such as random forests and LSTMs achieving R² values above 0.90 for short-term volume predictions [

20]. However, data gaps remain significant in developing nations due to the lack of official e-waste statistics [

1], necessitating stronger collaboration among governments, OEMs, and recyclers for robust data-sharing [

27]. Efficient reverse logistics, encompassing optimized collection depots, route planning, and centralized recycling, can significantly reduce CO₂ emissions and operational costs, with ML-driven frameworks demonstrating a 20–30% reduction in transport distances in certain pilot projects [

19]. Reinforcement learning further enhances adaptability by dynamically adjusting routing based on real-time traffic conditions and fluctuations in disposal demands [

23]. Consumer return behaviours are highly sensitive to financial incentives, and AI-driven dynamic pricing algorithms can improve e-waste collection rates by adjusting buy-back offers according to device condition and material composition [

8,

18]. Additionally, Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks can integrate dynamic fees or rebates to incentivize high recycling compliance [

1]

7. Policy and Governance Perspectives

International regulatory frameworks, such as the Basel Convention and the EU Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive, have contributed to the partial standardization of global e-waste management [

28]; however, AI-specific legislation remains fragmented, with unclear liabilities for automation errors or disassembly malfunctions [

3]. Establishing transparent standards for data sharing and system audits is essential to address these gaps. AI enhances Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) by enabling real-time tracking of product returns, material flows, and recycling compliance [

1], as demonstrated in a Chinese pilot program that integrated AI dashboards into EPR systems for real-time monitoring of OEM return rates [

27]. The widespread adoption of such platforms will require harmonized policy incentives and integrated data architectures. However, AI-driven systems often depend on user data, including geolocation and disposal habits, raising significant privacy concerns, while algorithmic biases may lead to the exclusion of certain demographics or regions [

13]. To mitigate these risks, regulatory bodies must implement frameworks that mandate robust data governance, transparent model audits, and alignment with human rights norms [

24].

8. Environmental and Economic Assessments

AI-driven solutions enhance material recovery and reduce the need for virgin resource extraction, with studies documenting a 28% decrease in CO₂ emissions when AI sorting improves high-value metal recovery [

6] and an 18% reduction in energy consumption at AI-equipped facilities compared to manual processes [

4]. These energy savings are particularly significant in regions where electrical grids rely on fossil fuels. Economic analyses indicate that AI-driven e-waste recycling can achieve net profit margins of 10–15%, primarily due to labour reductions and increased material capture [

4], though high capital costs for robotics may deter small-scale recyclers, necessitating joint ventures or targeted subsidies as potential solutions [

16]. While automation can displace manual dismantling roles, especially in regions with strong informal recycling economies [

16], it also creates new opportunities in robot operation, AI maintenance, and data analytics. Workforce retraining programs are essential to ensure an inclusive transition, minimizing social disruption and fostering long-term economic resilience [

24].

9. Strengthening Quantitative Comparisons

9.1. Need for Structured Data

Responding to reviewer requests for greater quantitative rigor,

Table 2 consolidates performance metrics from a subset of the reviewed studies.

9.2. Recommended Metrics and Protocols

Lack of standardization restricts cross-comparison.

Table 3 suggests a set of common metrics and methodologies for future research.

10. Discussion

10.1. Integration with Broader Sustainability Frameworks

AI-driven e-waste management aligns with several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production): By improving resource recovery and reducing hazardous disposal.

SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure): By fostering technological innovation in waste processing.

SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth): By transitioning workers to higher-skilled jobs, provided retraining is adequately supported.

SDG 13 (Climate Action): Through carbon footprint reductions and energy savings.

Linking these outcomes explicitly to the SDGs underscores the global relevance and cross-sector impact of AI-driven e-waste solutions.

10.2. Interdisciplinary Perspectives

Realizing the full potential of AI in e-waste management requires insights from:

Economics: Designing financial incentives and ROI models for small recyclers.

Sociology and Anthropology: Understanding user behaviours, informal sector dynamics, and cultural norms around product disposal.

Law and Public Policy: Addressing cross-border e-waste flows, data governance, and standardizing EPR frameworks.

Such interdisciplinary collaboration ensures that AI applications account for local labour policies, governance structures, and ethical imperatives.

10.3. Policy Guidelines and Industrial Implications

Multi-level governance is essential to accelerate AI adoption in e-waste management:

Local Level: Municipal AI pilot projects, tax incentives for purchasing AI-based sorting equipment, NGO-led operator training.

National Level: Strengthened EPR mandates that require real-time data reporting, financial incentives for OEMs adopting circular design, robust data-sharing agreements among stakeholders.

International Level: Harmonizing e-waste classification standards (e.g., under Basel Convention), coordinating R&D funding, and promoting cross-border data exchange 282828.

For industries, AI can bolster brand reputation, reduce operational costs, and open new markets. However, initial capital may be high, prompting the need for public–private partnerships, grants, or low-interest financing options to support small and medium recyclers.

11. Future Research Directions

Technological advancements in AI-driven e-waste management are revolutionizing the circular economy by integrating

multimodal fusion—combining optical, hyperspectral, and acoustic sensing for enhanced material detection [

4]—and

Edge AI, which enables low-power computation for rural or mobile recycling applications [

18]. Additionally,

advanced reinforcement learning is streamlining robotic disassembly across diverse device types, reducing labour-intensive processes [

23]. To accelerate AI adoption,

standardized open-access repositories for e-waste imaging, spectral data, and usage patterns—governed by uniform labelling practices—are essential for minimizing duplication and fostering more robust AI models [

19]. However, these advancements must be accompanied by deeper explorations into

algorithmic bias, workforce retraining, and socio-economic impacts [

13], ensuring that automation does not disproportionately disadvantage informal recyclers or underrepresented communities.

User-centric design and community engagement can mitigate unintended consequences, fostering equitable technology deployment [

24]. Moreover, AI has the potential to

reshape business models, introducing

subscription-based electronics, pay-per-use services, and real-time device monitoring, all of which extend product lifecycles and promote sustainable consumption [

14]. Achieving large-scale AI integration requires a

phased global approach that begins with

pilot projects in diverse settings (e.g., developing economies) to refine AI adaptability to informal sector needs, followed by the formation of

cross-industry consortia (OEMs, recyclers, AI firms) to establish

interoperable data standards.

Capacity building through workforce training programs is crucial to mitigating job displacement, while

longitudinal studies must assess how AI solutions perform over time under

evolving waste streams and shifting regulatory landscapes (e.g., Basel amendments) [

27]. Multi-year tracking of

resource recovery rates, carbon footprints, and socio-economic impacts will provide the empirical evidence needed to drive policy decisions. Finally, ensuring that AI-powered waste management is

ethically aligned with environmental and social justice principles necessitates

inclusive, participatory approaches that empower local recyclers and stakeholders, creating a truly circular and sustainable e-waste ecosystem.

12. Limitations of the Review

Despite efforts at rigor and comprehensiveness, this review has several limitations:

Language Filter: Only English-language articles were included, which may exclude pertinent research published in other languages.

Database Scope: We limited our search to four major databases. Relevant studies in specialized or regional databases might be missing.

Exclusion of Grey Literature: Policy briefs, non-peer-reviewed pilot results, and NGO reports were not systematically reviewed. This may omit practical insights or local innovations.

Publication Bias: Studies reporting successful AI implementations are more likely to be published, potentially skewing findings toward positive outcomes.

Heterogeneous Metrics: Variability in reporting methods and a lack of standardized measures make cross-study comparisons less precise.

Recognizing these constraints, future reviews could expand linguistic scope, integrate grey literature, and employ standardized metrics to mitigate these gaps.

13. Conclusion

This systematic review demonstrates the significant potential of AI and ML to advance e-waste management within a circular economy. Drawing on findings from 30 peer-reviewed articles, we reveal how automated sorting, robotic disassembly, predictive modelling, and supportive policy frameworks can substantially improve resource recovery, reduce environmental impact, and generate economic value.

Nevertheless, critical barriers persist—data limitations, regulatory gaps, high capital requirements, and societal/ethical concerns—that must be addressed through multi-level policy interventions, inclusive design strategies, and interdisciplinary collaborations. We call on researchers to standardize reporting metrics and pursue longitudinal studies, and on policymakers to implement enabling regulations and financial instruments that foster equitable AI uptake.

By aligning technological innovation with global sustainability goals, AI-driven e-waste management can help transition from a linear “take–make–dispose” approach to a truly circular and regenerative model—creating a pathway for sustainable development that respects both people and the planet.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were generated for this review. All data supporting the findings are derived from publicly available peer-reviewed articles as cited in the reference list.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the library staff at Dronacharya Group of Institutions for facilitating comprehensive database access and providing technical support during the literature review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Awasthi, A. K., & Li, J. (2017). Management of electrical and electronic waste: A comparative evaluation of China and India. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 76, 434–447. [CrossRef]

- Baldé, C. P., Forti, V., Gray, V., Kuehr, R., & Stegmann, P. (2021). The Global E-waste Monitor – 2020. United Nations University.

- Bakhiyi, B., Gravel, S., Ceballos, D., Flynn, M. A., & Zayed, J. (2018). Has the question of e-waste opened a Pandora’s box? An overview of risks and hazards of electronic wastes. Reviews on Environmental Health, 33(1), 49–69.

- Van Yken, J., Boxall, N. J., Cheng, K. Y., Nikoloski, A. N., Moheimani, N. R., & Kaksonen, A. H. (2021). E-Waste Recycling and Resource Recovery: A Review on Technologies, Barriers and Enablers with a Focus on Oceania. Metals, 11(8), 1313. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. E., Rastegarpanah, A., & Stolkin, R. (2024). Robotic disassembly for end-of-life products focusing on task and motion planning: A comprehensive survey. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 77, 483–524. [CrossRef]

- Cucchiella, F., D’Adamo, I., Koh, S. L., & Rosa, P. (2015). Recycling of WEEEs: An economic assessment of present and future e-waste streams. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 51, 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Elia, V., Gnoni, M. G., & Tornese, F. (2020). Measuring circular economy strategies through index methods: A critical analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 249, 119–136.

- Hwang, S.B., Kim, S. (2006). Dynamic Pricing Algorithm for E-Commerce. In: Sobh, T., Elleithy, K. (eds) Advances in Systems, Computing Sciences and Software Engineering. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU), United Nations University (UNU), and International Solid Waste Association (ISWA). Retrieved from https://www.itu.int/en/itu-d/environment/pages/spotlight/global-ewaste-monitor-2020.aspx.

- Hong, Q. N., et al. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H., & Hanafiah, M. M. (2020). A review of sustainable e-waste generation and management: Present and future perspectives. Journal of Environmental Management, 264, 110–497. [CrossRef]

- Krichen, M. (2023). Convolutional Neural Networks: A Survey. Computers, 12(8), 151. [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, C., Douglas, D., Lu, Q., Schleiger, E., Whittle, J., Lacey, J., Newnham, G., Hajkowicz, S., Robinson, C., & Hansen, D. (2021). AI ethics principles in practice: Perspectives of designers and developers. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia. arXiv.

- Lewandowski, M. (2016). Designing the business models for circular economy—Towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability, 8(1), 1–28.

- Brogan, D. P., DiFilippo, N. M., & Jouaneh, M. K. (2021). Deep learning computer vision for robotic disassembly and servicing applications. Array, 12, 100094. [CrossRef]

- Manhart, A., & Osibanjo, O. (2009). Informal e-waste management in Lagos, Nigeria—Socio-economic impacts and feasibility of international recycling co-operations. Environmental Development, 3, 19–32.

- Moher, D., et al. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Shahrasbi, A., Shokouhyar, S., & Zeidyahyaee, N. (2021). Consumers’ behavior towards electronic wastes from a sustainable development point of view: An exploration of differences between developed and developing countries. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 28, 1736–1756. [CrossRef]

- Nizami, A., et al. (2021). Artificial intelligence in integrated solid waste management. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 150, 228–238.

- Okoye, P., & Zawbaa, H. (2021). E-waste forecasting using machine learning: A comparative study. Environmental Science & Policy, 125, 206–215.

- Ongondo, F. O., Williams, I. D., & Cherrett, T. J. (2011). How are WEEE doing? A global review of the management of electrical and electronic wastes. Waste Management, 31(4), 714–730.

- Recupel. (2022). Belgium’s Smart Sortation Pilot: Annual Report Fang, B., Yu, J., Chen, Z. et al. Artificial intelligence for waste management in smart cities: a review. Environ Chem Lett 21, 1959–1989 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Zheng, P., Yin, Y., Wang, B., & Wang, L. (2023). Deep reinforcement learning in smart manufacturing: A review and prospects. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology, 40, 75–101. [CrossRef]

- Risse, M. (2019). Human rights and artificial intelligence: An urgent agenda. Human Rights & International Legal Discourse, 13(2), 141–154.

- Stahel, W. R. (2016). The circular economy. Nature News, 531(7595), 435.

- UNEP. (2022). Responsible AI for a sustainable future. [Policy Report]. United Nations Environment Programme.

- Ankit, Saha, L., Kumar, V., Tiwari, J., Sweta, Rawat, S., Singh, J., & Bauddh, K. (2021). Electronic waste and their leachates impact on human health and environment: Global ecological threat and management. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 24, 102049. [CrossRef]

- WEF. (2021). Global E-waste Collaboration: Policy Enablers for Circular Electronics. World Economic Forum.

- J. Sousa, A. Rebelo and J. S. Cardoso, “Automation of Waste Sorting with Deep Learning,” 2019 XV Workshop de Visão Computacional (WVC), São Bernardo do Campo, Brazil, 2019, pp. 43-48. [CrossRef]

- Wegener, K., Chen, W. H., Dietrich, F., Dröder, K., & Kara, S. (2015). Robot assisted disassembly for the recycling of electric vehicle batteries. Procedia CIRP, 29, 716–721. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).