Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

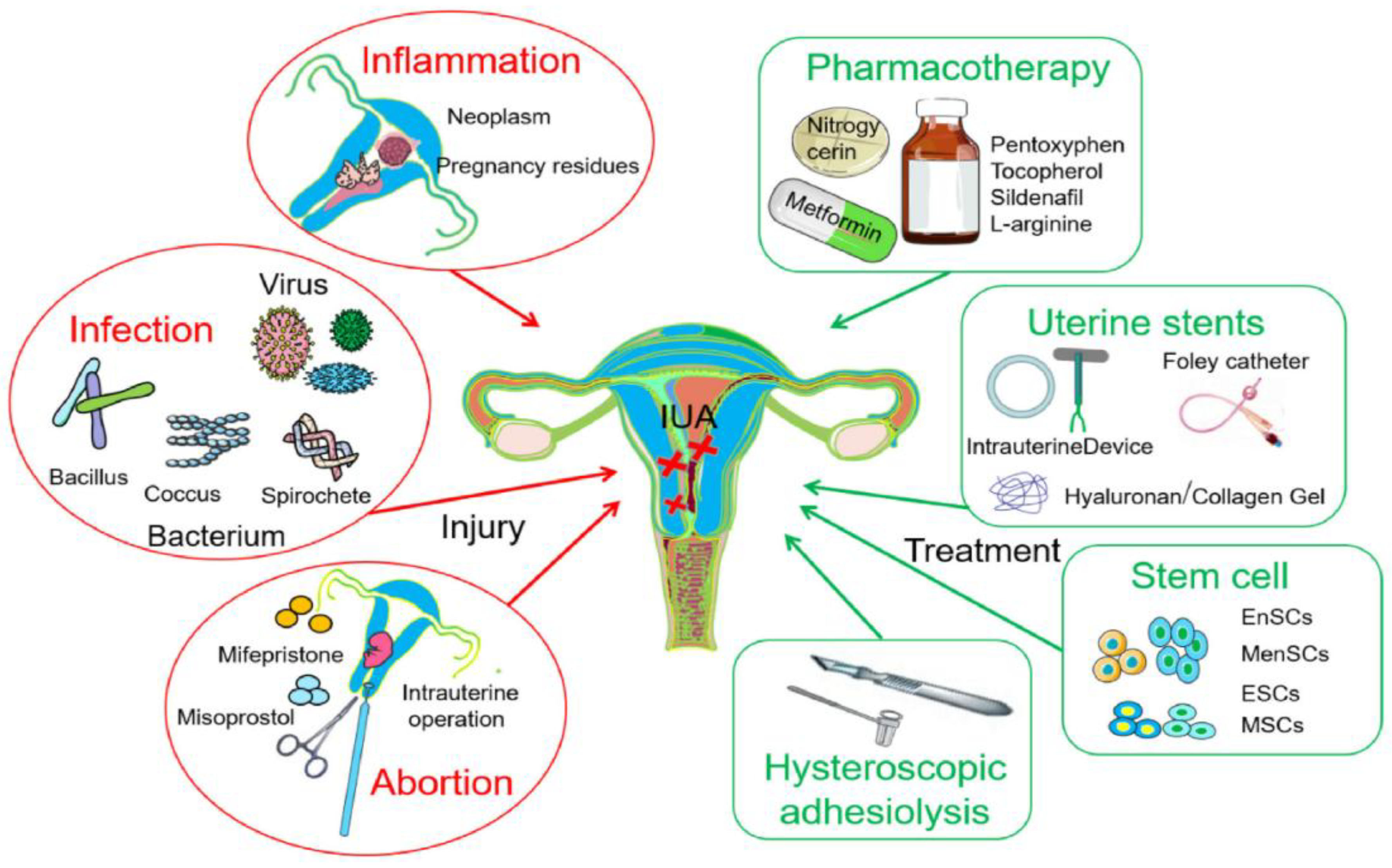

1. Introduction

2. Combination Therapy for IUAs (Hysteroscopy & Biomaterials)

3. Biopolymers and Potential Biomedical Applications

4. Examples of Naturally-occurring Biomaterials and their Applications

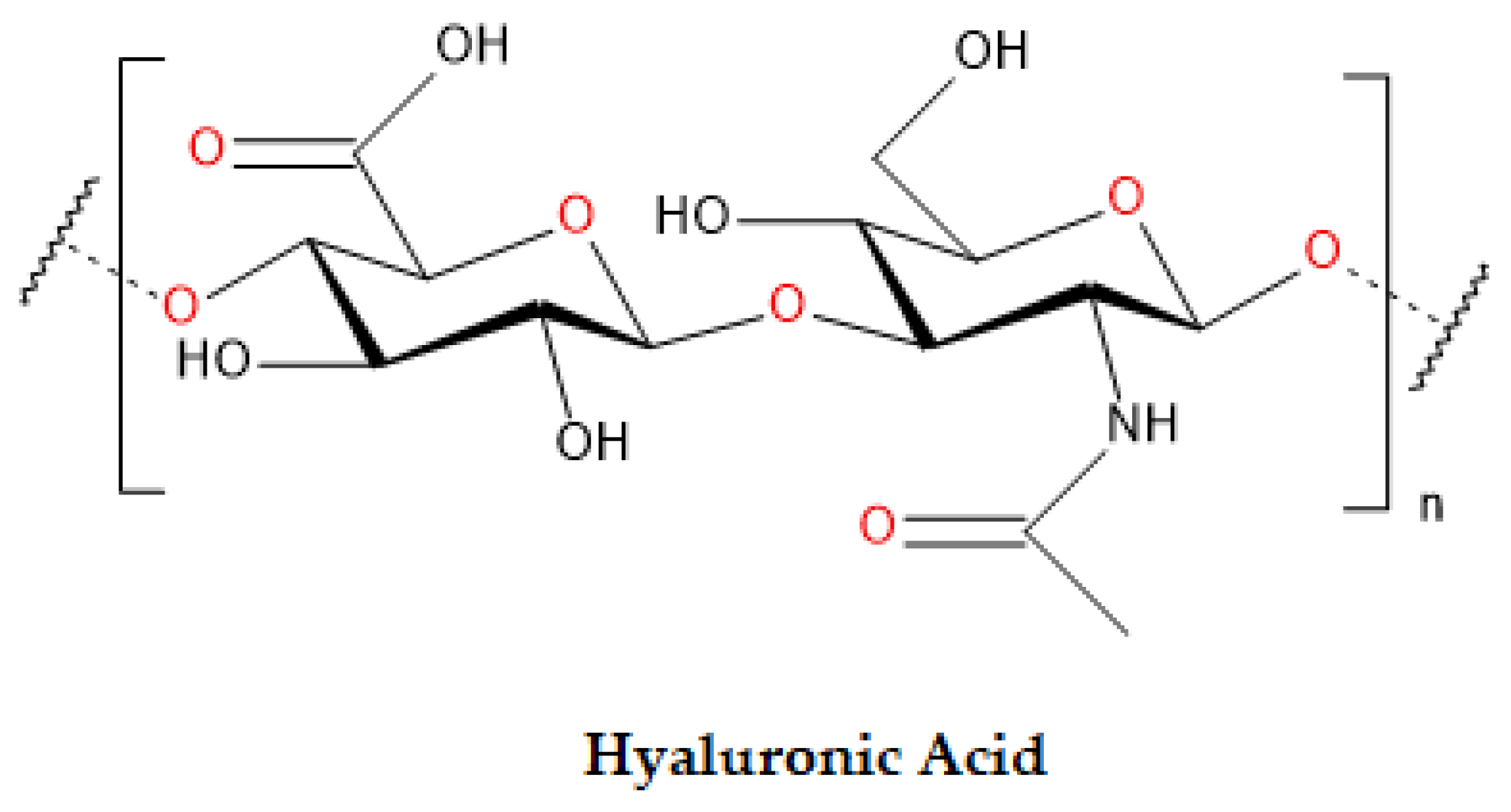

4.1. Hyaluronic Acid

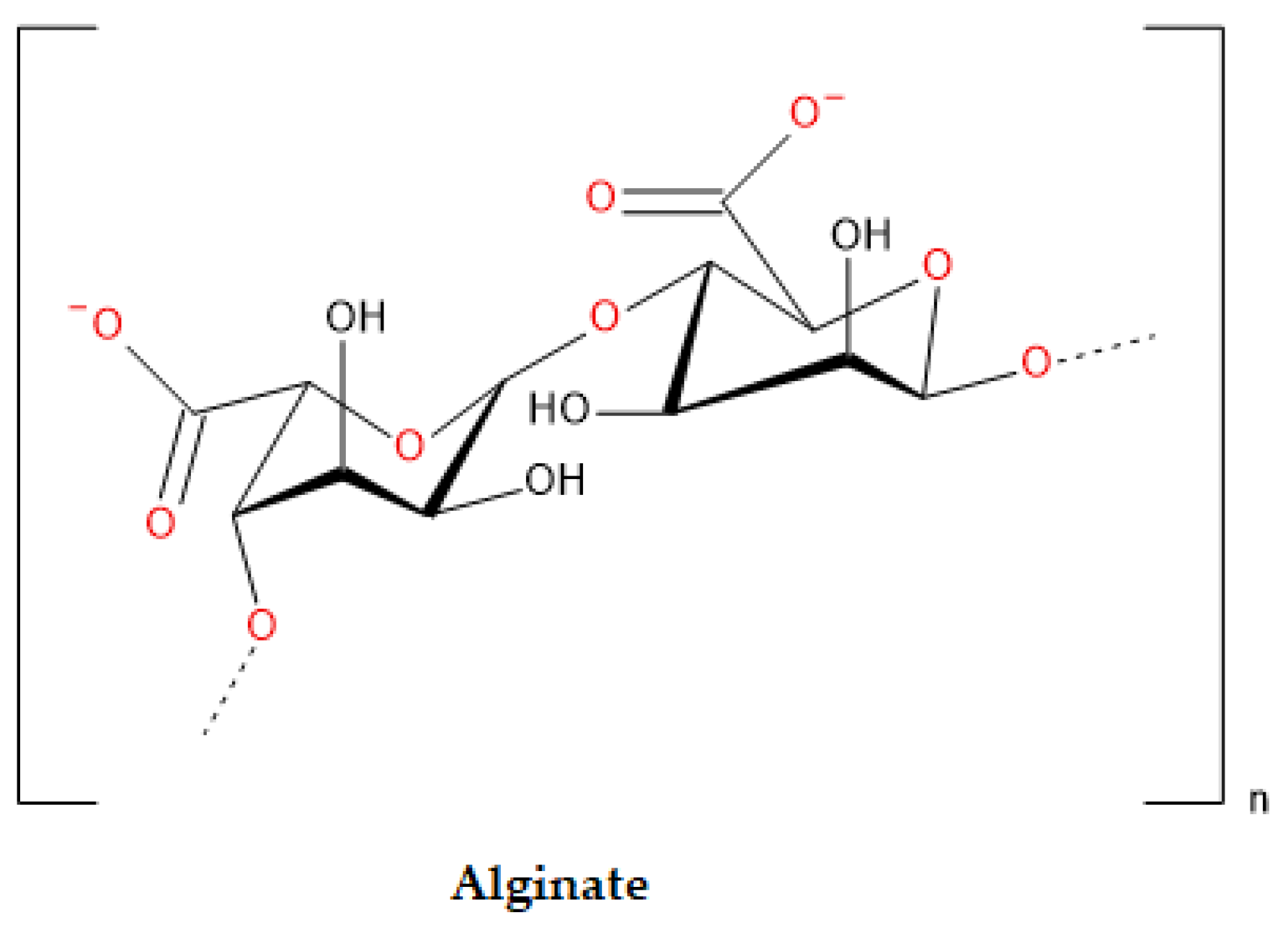

4.2. Alginate

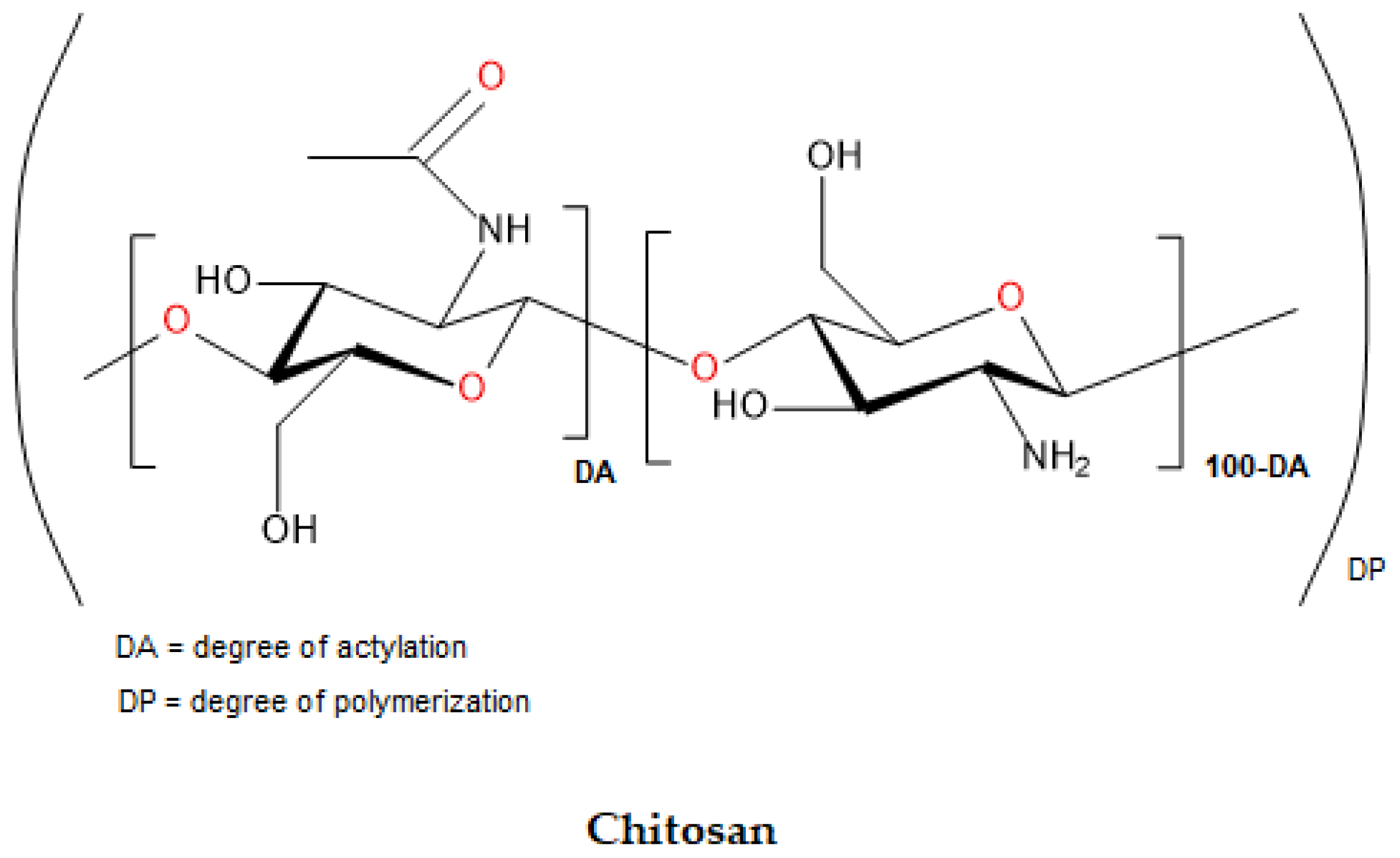

4.3. Chitosan

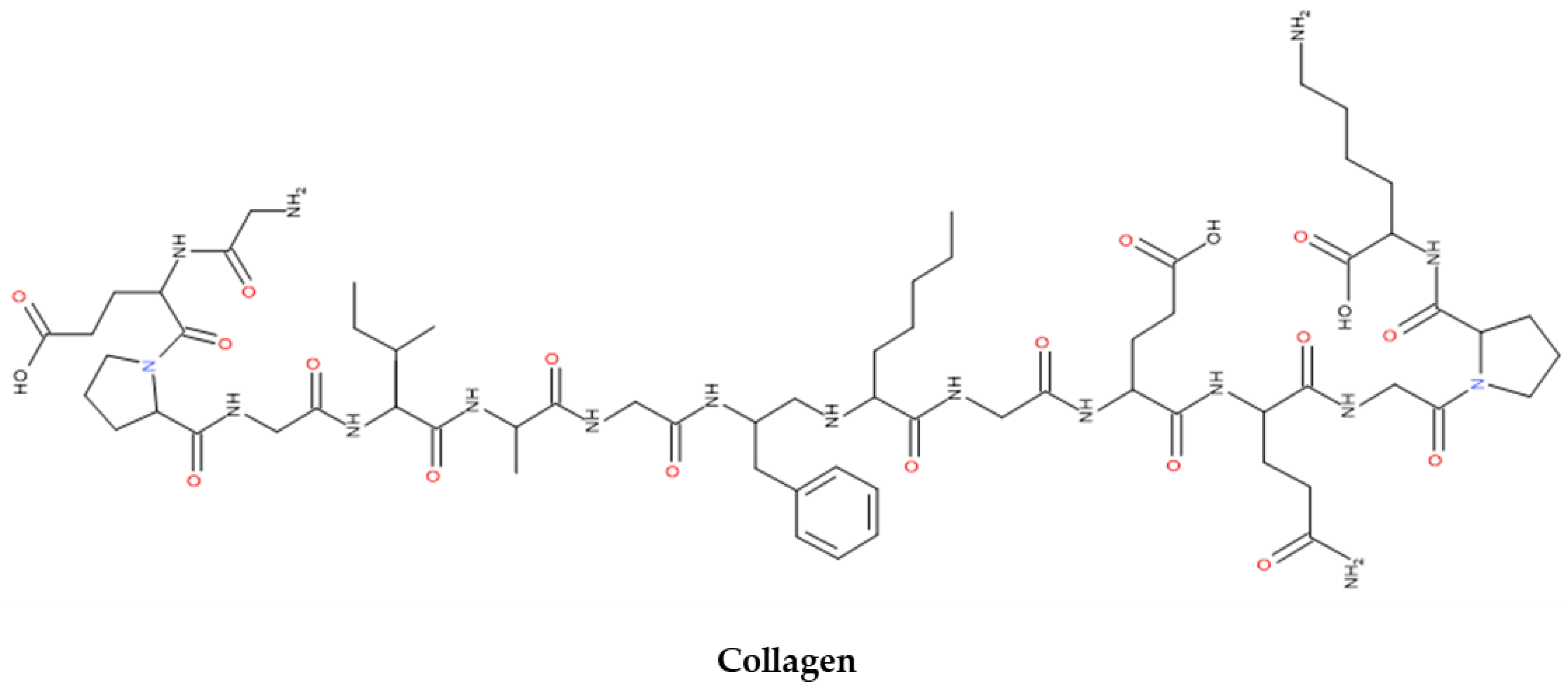

4.4. Collagen

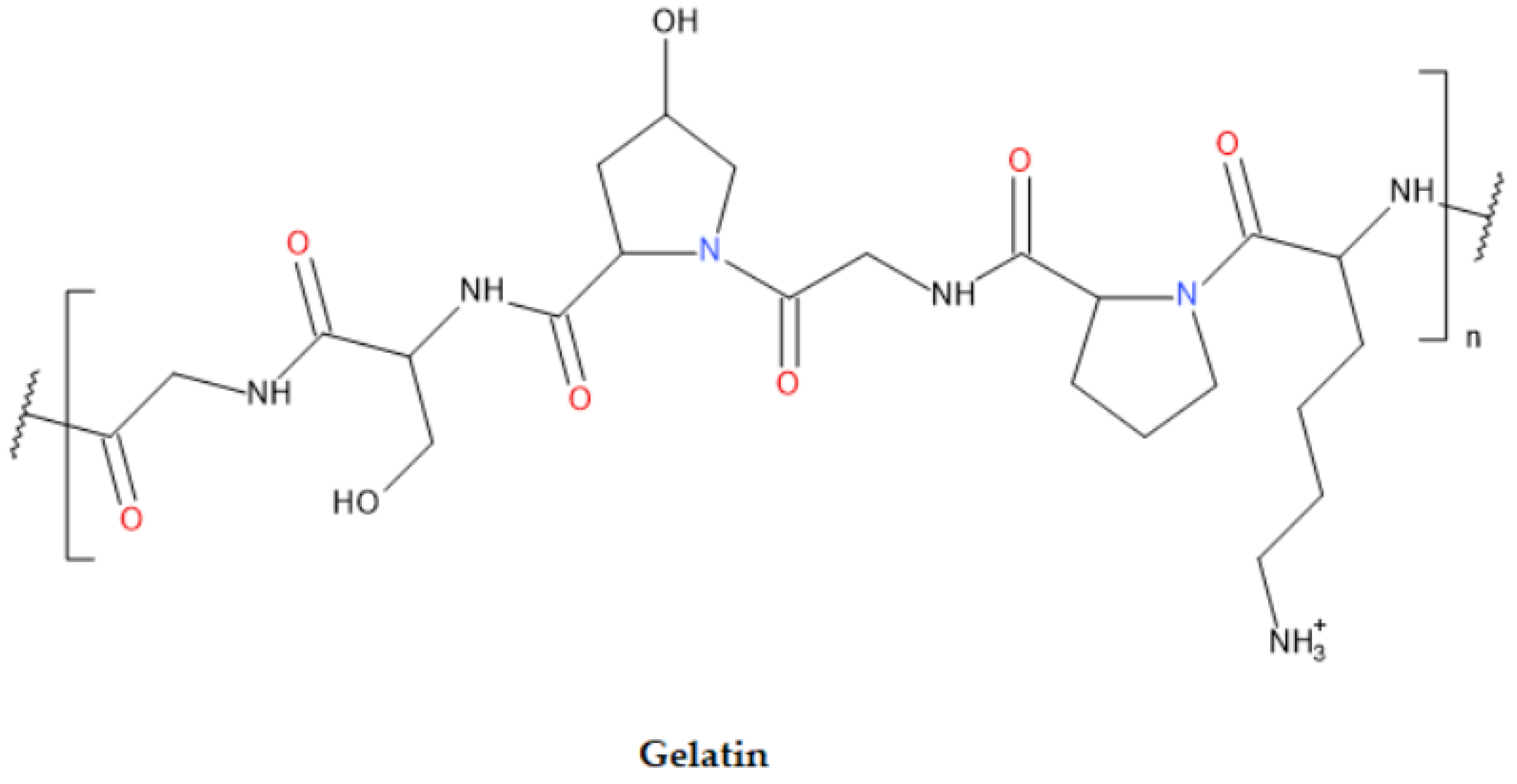

4.5. Gelatin

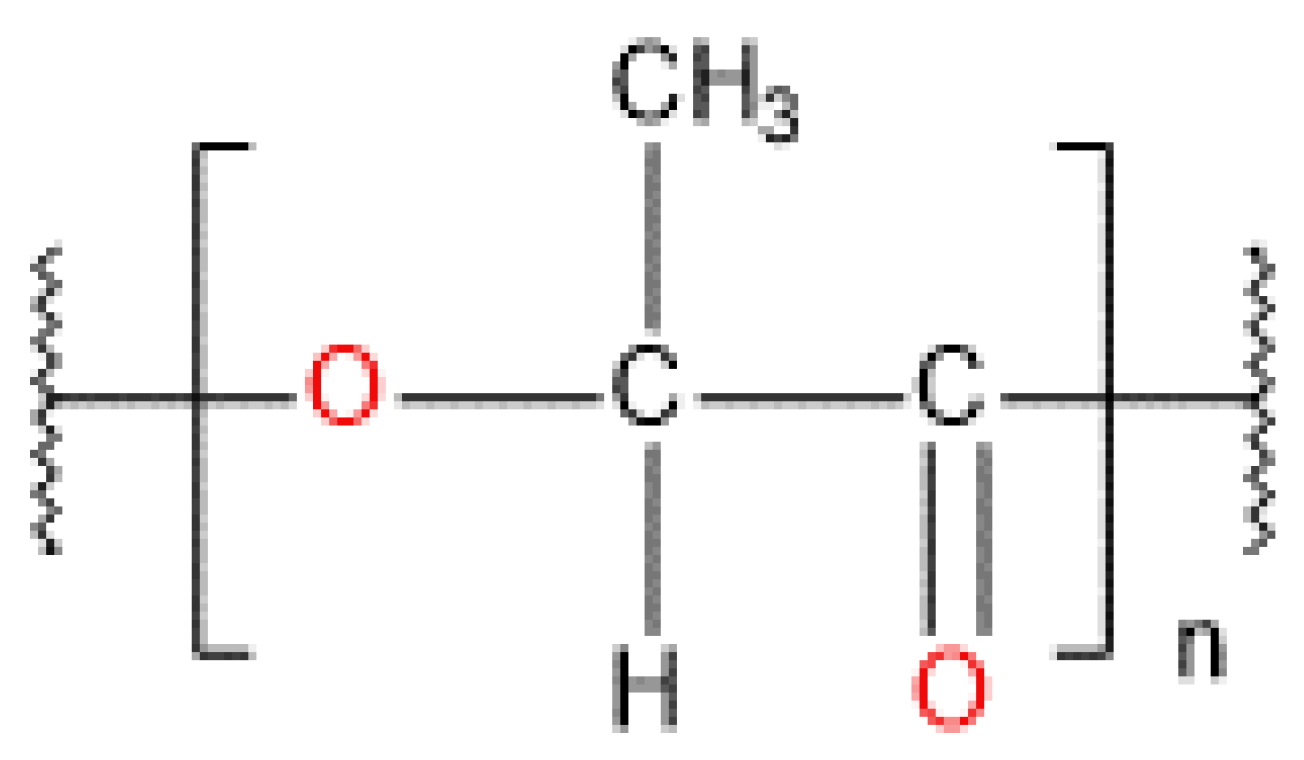

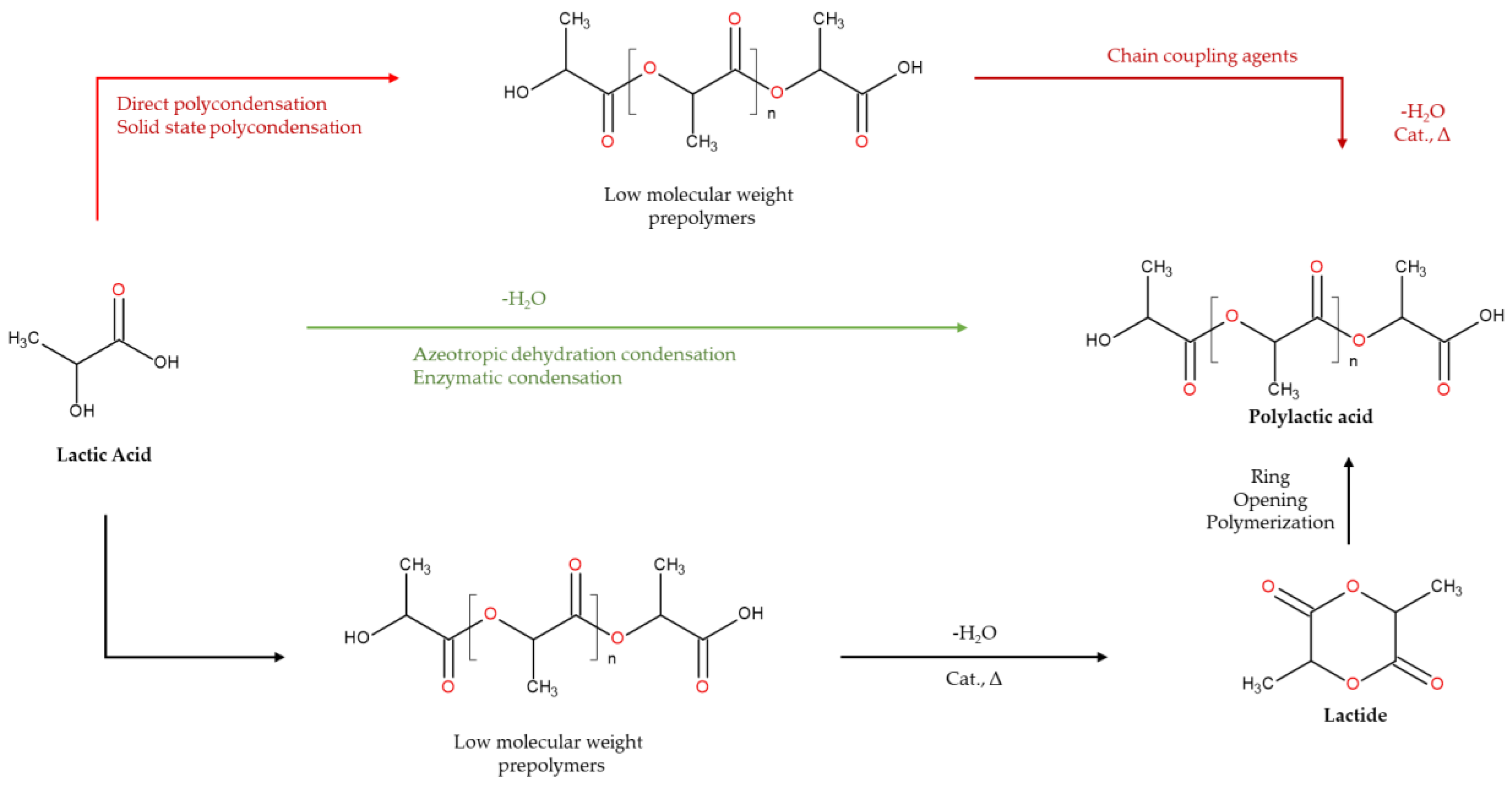

4.6. Polylactic Acid

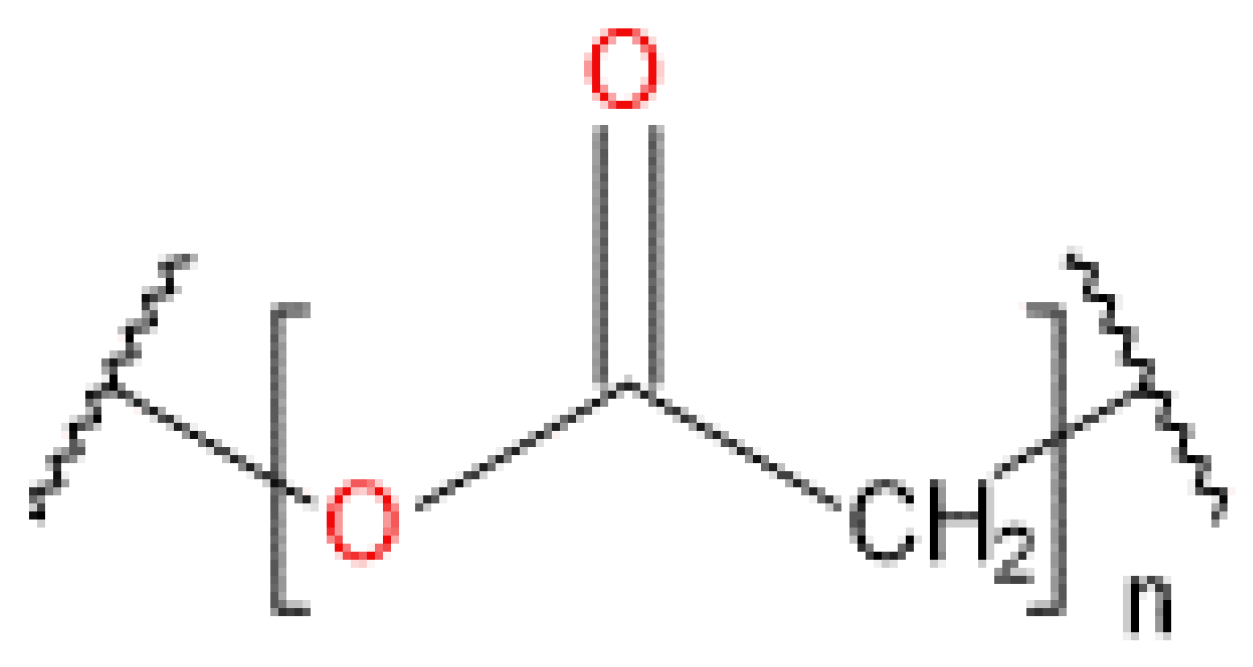

4.7. Polyglycolic Acid

4.8. Carboxymethylcellulose

| Biomaterial | Nature | Source | Tm (°C) | Applications/Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | Polysaccharide-based | Mainly in extracellular matrices of vertebrates and humans | N/A | Reproductive & regenerative medicine Tissue engineering Drug delivery Endometrial regeneration Abundant in ECM High biocompatibility and fluidity |

Rapid degradation Limited mechanical strength Immunosuppressive and antiangiogenic (long chains) |

[52,54] |

| ALG | Polysaccharide-based | Seaweed and bacterial origin | 99 | FDA approved and Ph. Eur adopted Stable in the form of hydrogel Facilitate cell encapsulation and 3D printing Artificial ovaries making DDSs High level of deformability Relatively less expensive |

Limited degradation and renal clearance Deficiency in the property of cell adhesion Limited ability to promote cell migration and cell adhesion Cannot be used alone |

[64,65] |

| Chitosan | Polysaccharide-based | Crustacean shells | 102.5 | Wound dressings Hemostatic properties Implants Tissue engineering DDSs |

Limited mechanical strength Poor water resistance, and low thermal stability |

[70,79] |

| Collagen | Protein-based | ECM component in mammals and aquatic organisms | 71-96 | Cell adhesion and regeneration Amenability to modifications Stem cells and DDSs |

Low mechanical stability Cannot be used alone |

[47,115] |

| Gelatin | Protein-based | Extracted from bones, skin, and connective tissues of animals | 40 | Excellent gelation Flexible for modifications Promote cell proliferation and adhesion Low cost |

Low thermal stability and weak mechanical strength | [86,116] |

| PLA | Polymer of lactic acid | Extracted from sugar cane, corn, cassava and maize or Synthesized via direct polycondensation, azeotropic condensation or ring opening polymerization |

170-180 | FDA-approved Used as Implants Good biodegradability Excellent mechanical properties and chemical stability Less expensive The most commonly used poly-lactone |

Complex synthesis Rapid degradation Can elicit inflammatory responses from acidic by-products High permeability of gases or vapors via PLA films |

[1,43] |

| PGA | Polymer of glycolic acid | Synthesized via melt polycondensation or ring opening polymerization | 220 | FDA-approved Excellent mechanical strength, solvent resistance as well as excellent gas barrier capabilities |

Glycolic acid accumulation can elicit inflammation and lead to impaired cell proliferation and differentiation High production cost Reduced toughness, and rapid hydrolysis and biodegradation Thermal instability |

[42,104,105] |

| CMC | Polysaccharide-based | Synthesized from plants via alkalization and etherification reactions | 274 | Biocompatibility Common additive Less expensive Derivative of cellulose, the most abundant polymer Strong mechanical properties |

Poor degradation profile Limited viscosity, and poor rheological properties | [108,109,110] |

5. Marketed Biomaterial Products for Cell/Tissue Regeneration

6. Conclusions and Future Outlook

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Savioli Lopes, A. L. Jardini, and R. Maciel Filho, “Poly (lactic acid) production for tissue engineering applications,” Procedia Eng., vol. 42, no. August, pp. 1402–1413, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang et al., “Application of Bioactive Hydrogels for Functional Treatment of Intrauterine Adhesion,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 9, no. September, pp. 1–16, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Buckley, E. J. Murphy, T. R. Montgomery, and I. Major, “Hyaluronic Acid: A Review of the Drug Delivery Capabilities of This Naturally Occurring Polysaccharide,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 14, no. 17, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Murphy et al., “Polysaccharides—Naturally Occurring Immune Modulators,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Lee et al., “Self-healing and adhesive artificial tissue implant for voice recovery,” ACS Appl. Bio Mater., vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 1134–1146, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Pina, J. M. Oliveira, and R. L. Reis, “Natural-based nanocomposites for bone tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: A review,” Adv. Mater., vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 1143–1169, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Gwak, Y. Bin Lee, E. J. Lee, K. H. Park, S. W. Kang, and K. M. Huh, “The use of acetylation to improve the performance of hyaluronic acid-based dermal filler,” Korean J. Chem. Eng., vol. 40, no. 8, pp. 1963–1969, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Lee, X. Du, I. Kim, and S. J. Ferguson, “Scaffolds for bone-tissue engineering,” Matter, vol. 5, no. 9, pp. 2722–2759, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Feng et al., “Engineering self-healing adhesive hydrogels with antioxidant properties for intrauterine adhesion prevention,” Bioact. Mater., vol. 27, no. March, pp. 82–97, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Schmerold et al., “A cost-effectiveness analysis of intrauterine spacers used to prevent the formation of intrauterine adhesions following endometrial cavity surgery,” J. Med. Econ., vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 170–183, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Y. Huang et al., “Crosslinked hyaluronic acid gels for the prevention of intrauterine adhesions after a hysteroscopic myomectomy in women with submucosal myomas: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial,” Life, vol. 10, no. 5, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Wang, S. T. Yang, W. H. Chang, C. H. Liu, H. H. Liu, and W. L. Lee, “Intrauterine adhesion,” Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 312–319, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Kou, X. Jiang, S. Xiao, Y. Z. Zhao, Q. Yao, and R. Chen, “Therapeutic options and drug delivery strategies for the prevention of intrauterine adhesions,” J. Control. Release, vol. 318, no. December 2019, pp. 25–37, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. W. Huang et al., “A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing two different treatments of intrauterine adhesions,” Reprod. Biomed. Online, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 835–841, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Cen et al., “Research progress of stem cell therapy for endometrial injury,” Mater. Today Bio, vol. 16, no. August, p. 100389, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Hooker, F. J. Mansvelder, R. G. Elbers, and Z. Frijmersum, “Reproductive outcomes in women with mild intrauterine adhesions; a systematic review and meta-analysis,” J. Matern. Neonatal Med., vol. 35, no. 25, pp. 6933–6941, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, L. Liu, Y. Luo, M. Chen, Y. Huan, and R. Fang, “Prevalence and Impact of Chronic Endometritis in Patients With Intrauterine Adhesions: A Prospective Cohort Study,” J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol., vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 74–79, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Di Guardo and M. Palumbo, “Asherman syndrome and insufficient endometrial thickness: A hypothesis of integrated approach to restore the endometrium,” Med. Hypotheses, vol. 134, no. November 2019, pp. 2019–2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Yu, Y. M. Wong, Y. Cheong, E. Xia, and T. C. Li, “Asherman syndrome-one century later,” Fertil. Steril., vol. 89, no. 4, pp. 759–779, 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. M. F. Hanstede, E. Van Der Meij, L. Goedemans, and M. H. Emanuel, “Results of centralized Asherman surgery, 2003-2013,” Fertil. Steril., vol. 104, no. 6, pp. 1561-1568.e1, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Bosteels et al., “Anti-adhesion therapy following operative hysteroscopy for treatment of female subfertility,” Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., vol. 2017, no. 11, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen et al., “Collagen-based materials in reproductive medicine and engineered reproductive tissues,” J. Leather Sci. Eng., vol. 4, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Kim, Y. Y. Kim, H. Kim, and S. Y. Ku, “Recent Advancements in Engineered Biomaterials for the Regeneration of Female Reproductive Organs,” Reprod. Sci., vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 1612–1625, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Tabeeva et al., “The Therapeutic Potential of Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cell—Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Endometrial Regeneration,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 24, no. 11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Ma et al., “Recent trends in therapeutic strategies for repairing endometrial tissue in intrauterine adhesion,” Biomater. Res., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 1–25, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Z. Liu, H. G. Zhao, Y. Gao, M. Liu, and B. Z. Guo, “Effectiveness of estrogen treatment before transcervical resection of adhesions on moderate and severe uterine adhesion patients,” Gynecol. Endocrinol., vol. 32, no. 9, pp. 737–740, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chi et al., “Transdermal estrogen gel and oral aspirin combination therapy improves fertility prognosis via the promotion of endometrial receptivity in moderate to severe intrauterine adhesion,” Mol. Med. Rep., vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 6337–6344, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Shukla, R. Jamwal, and K. Bala, “Adverse effect of combined oral contraceptive pills,” Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 17–21, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. L. Lee, C. H. Liu, M. Cheng, W. H. Chang, W. M. Liu, and P. H. Wang, “Focus on the primary prevention of intrauterine adhesions: Current concept and vision,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 22, no. 10, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Y. Kim et al., “Synergistic regenerative effects of functionalized endometrial stromal cells with hyaluronic acid hydrogel in a murine model of uterine damage,” Acta Biomater., vol. 89, pp. 139–151, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Luo, Y. Wang, Y. Xu, J. Wang, and Y. Yu, “Modification and crosslinking strategies for hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel biomaterials,” Smart Med., vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 1–18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Buckley, T. R. Montgomery, T. Szank, and I. Major, “Hyaluronic acid hybrid formulations optimised for 3D printing of nerve conduits and the delivery of the novel neurotrophic-like compound tyrosol to enhance peripheral nerve regeneration via Schwann cell proliferation,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 661, no. July, p. 124477, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Tang, J. Chen, J. Guo, Q. Wei, and H. Fan, “Construction and evaluation of fibrillar composite hydrogel of collagen/konjac glucomannan for potential biomedical applications,” Regen. Biomater., vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 239–250, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Holländer et al., “Three-Dimensional Printed PCL-Based Implantable Prototypes of Medical Devices for Controlled Drug Delivery,” J. Pharm. Sci., vol. 105, no. 9, pp. 2665–2676, 2016. [CrossRef]

- X. Mao et al., “Cross-linked hyaluronan gel to improve pregnancy rate of women patients with moderate to severe intrauterine adhesion treated with IVF: a randomized controlled trial,” Arch. Gynecol. Obstet., vol. 301, no. 1, pp. 199–205, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen et al., “Efficacy and safety of auto-cross-linked hyaluronic gel to prevent intrauterine adhesion after hysteroscopic electrosurgical resection: a multi-center randomized controlled trial,” Ann. Transl. Med., vol. 10, no. 22, pp. 1217–1217, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Fei, X. Xin, H. Fei, and C. Yuechong, “Meta-analysis of the use of hyaluronic acid gel to prevent intrauterine adhesions after miscarriage,” Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol., vol. 244, pp. 1–4, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Pabuçcu, E. Kovanci, Ö. Şahin, E. Arslanoğlu, Y. Yıldız, and R. Pabuçcu, “New crosslinked hyaluronan gel, intrauterine device, or both for the prevention of intrauterine adhesions,” J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg., vol. 23, no. 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. C. R. Leonel et al., “New Solutions for Old Problems: How Reproductive Tissue Engineering Has Been Revolutionizing Reproductive Medicine,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 2143–2171, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Tamadon, K. H. Park, Y. Y. Kim, B. C. Kang, and S. Y. Ku, “Efficient biomaterials for tissue engineering of female reproductive organs,” Tissue Eng. Regen. Med., vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 447–454, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Wu et al., “Biomaterials and advanced technologies for the evaluation and treatment of ovarian aging,” J. Nanobiotechnology, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–41, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Peng, H. Liu, and Y. Fan, “Biomaterial Scaffolds for Reproductive Tissue Engineering,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., vol. 45, no. 7, pp. 1592–1607, 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Hoveizi and T. Mohammadi, “Differentiation of endometrial stem cells into insulin-producing cells using signaling molecules and zinc oxide nanoparticles, and three-dimensional culture on nanofibrous scaffolds,” J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med., vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 1–11, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Cai et al., “Recent Developments in Biomaterial-Based Hydrogel as the Delivery System for Repairing Endometrial Injury,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 10, no. June, pp. 1–16, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Trucillo, “Biomaterials for Drug Delivery and Human Applications,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 17, no. 2, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Vanacker et al., “Transplantation of an alginate-matrigel matrix containing isolated ovarian cells: First step in developing a biodegradable scaffold to transplant isolated preantral follicles and ovarian cells,” Biomaterials, vol. 33, no. 26, pp. 6079–6085, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Zuidema, C. J. Rivet, R. J. Gilbert, and F. A. Morrison, “A protocol for rheological characterization of hydrogels for tissue engineering strategies,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater., vol. 102, no. 5, pp. 1063–1073, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Cai et al., “Design and Development of Hybrid Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications: Recent Trends in Anticancer Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 9, no. February, pp. 1–18, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. N. Sudha and M. H. Rose, Beneficial effects of hyaluronic acid, 1st ed., vol. 72. Elsevier Inc., 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Kisukeda, J. Onaya, and K. Yoshioka, “Effect of diclofenac etalhyaluronate (SI-613) on the production of high molecular weight sodium hyaluronate in human synoviocytes,” BMC Musculoskelet. Disord., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Mohan, S. R. R. Tadi, S. S. Pavan, and S. Sivaprakasam, “Deciphering the role of dissolved oxygen and N-acetyl glucosamine in governing higher molecular weight hyaluronic acid synthesis in Streptococcus zooepidemicus cell factory,” Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., vol. 104, no. 8, pp. 3349–3365, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Caspersen et al., “Thermal degradation and stability of sodium hyaluronate in solid state,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 107, no. 1, pp. 25–30, 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Snetkov, K. Zakharova, S. Morozkina, and R. Olekhnovich, “Hyaluronic Acid : The Influence of Molecular Weight and Degradable Properties of Biopolymer,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 12, p. 1800, 2020.

- P. Paulino, M. B. Da Cruz, and V. Santos, “Hyaluronic Acid Aesthetic Fillers: A Review of Rheological and Physicochemical Properties,” J. Cosmet. Sci., vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 132–142, 2023.

- G. Abatangelo, V. Vindigni, G. Avruscio, L. Pandis, and P. Brun, “Hyaluronic acid: Redefining its role,” Cells, vol. 9, no. 7, pp. 1–19, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Buckley, T. R. Montgomery, T. Szank, B. A. Murray, C. Quigley, and I. Major, “Modification of hyaluronic acid to enable click chemistry photo-crosslinking of hydrogels with tailorable degradation profiles,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 240, no. April, p. 124459, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Lin, X. Y. Qiao, X. P. Chen, L. Z. Xu, and H. Chen, “Efficacy of Reducing Recurrence of Intrauterine Adhesions and Improving Pregnancy Outcome after Hysteroscopic Adhesiolysis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 51, no. 4, 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Devi, R. Devi, S. Pradhan, D. Giri, N. Lepcha, and S. Basnet, “Application of Correlational Research Design in Nursing and Application of Correlational Research Design in Nursing,” J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed., vol. 65, no. 11, pp. 60–69, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Jasper et al., “Belgian consensus on adhesion prevention in hysteroscopy and laparoscopy,” Gynecol. Surg., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 179–187, 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Tu, X. L. Yang, X. Y. Qin, L. P. Cai, and P. Zhang, “Management of intrauterine adhesions: A novel intrauterine device,” Med. Hypotheses, vol. 81, no. 3, pp. 394–396, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Saska, L. Pilatti, A. Blay, and J. A. Shibli, “Bioresorbable polymers: Advanced materials and 4D printing for tissue engineering,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1–24, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, D. Wu, W. Li, and L. Yang, “Emerging biomaterials for reproductive medicine,” Eng. Regen., vol. 2, no. November 2021, pp. 230–245, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Kaczmarek-Pawelska, “Alginate-Based Hydrogels in Regenerative Medicine,” Alginates - Recent Uses This Nat. Polym., no. July, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Tønnesen and J. Karlsen, “Alginate in drug delivery systems,” Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm., vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 621–630, 2002. [CrossRef]

- D. R. Sahoo and T. Biswal, “Alginate and its application to tissue engineering,” SN Appl. Sci., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–19, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Kurowiak, A. Kaczmarek-Pawelska, A. G. Mackiewicz, and R. Bedzinski, “Analysis of the degradation process of alginate-based hydrogels in artificial urine for use as a bioresorbable material in the treatment of urethral injuries,” Processes, vol. 8, no. 3, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Francés-Herrero, A. Rodríguez-Eguren, M. Gómez-álvarez, L. de Miguel-Gómez, H. Ferrero, and I. Cervelló, “Future Challenges and Opportunities of Extracellular Matrix Hydrogels in Female Reproductive Medicine,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 23, no. 7, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cai et al., “Porous scaffolds from droplet microfluidics for prevention of intrauterine adhesion,” Acta Biomater., vol. 84, pp. 222–230, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. K. L. Levengood and M. Zhang, “Chitosan-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering,” J. Mater. Chem. B, vol. 2, no. 21, pp. 3161–3184, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Alkabli, “Recent advances in the development of chitosan/hyaluronic acid-based hybrid materials for skin protection, regeneration, and healing: A review,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 279, no. P3, p. 135357, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Amidi, E. Mastrobattista, W. Jiskoot, and W. E. Hennink, “Chitosan-based delivery systems for protein therapeutics and antigens,” Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 59–82, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. (Gabriel) Kou, L. M. Peters, and M. R. Mucalo, “Chitosan: A review of sources and preparation methods,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 169, pp. 85–94, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Baldrick, “The safety of chitosan as a pharmaceutical excipient,” Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 290–299, 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Col, M. Moore, B. Whisman, and R. Gomez, “Safety of Chitosan Bandages in Shellfi sh Allergic Patients,” vol. 176, no. October 2011, pp. 1153–1156, 2018.

- M. Rizzo et al., “Effects of chitosan on plasma lipids and lipoproteins: A 4-month prospective pilot study,” Angiology, vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 538–542, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Z. Shariatinia, “Pharmaceutical applications of chitosan,” Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 263, pp. 131–194, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. I. Sánchez-Machado, J. López-Cervantes, M. A. Correa-Murrieta, R. G. Sánchez-Duarte, P. Cruz-Flores, and G. S. la Mora-López, Chitosan. Elsevier Inc., 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Nagori, S. Panchal, and H. Patel, “Endometrial regeneration using autologous adult stem cells followed by conception by in vitro fertilization in a patient of severe Ashermans syndrome,” J. Hum. Reprod. Sci., vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 43–48, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Singh, G. Singh, C. Prakash, S. Ramakrishna, L. Lamberti, and C. I. Pruncu, “3D printed biodegradable composites: An insight into mechanical properties of PLA/chitosan scaffold,” Polym. Test., vol. 89, p. 106722, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Ershad-Langroudi, N. Babazadeh, F. Alizadegan, S. Mehdi Mousaei, and G. Moradi, “Polymers for implantable devices,” J. Ind. Eng. Chem., vol. 137, no. November 2023, pp. 61–86, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Kulkarni and M. Maniyar, “Utilization of Fish Collagen in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Industries: Waste To Wealth Creation,” Res. J. Life Sci. Bioinformatics, Pharm. Chem. Sci., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 11–20, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Lu et al., “Targeting cancer stem cell signature gene SMOC-2 Overcomes chemoresistance and inhibits cell proliferation of endometrial carcinoma,” EBioMedicine, vol. 40, pp. 276–289, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Yanez, J. Rincon, A. Dones, C. De Maria, R. Gonzales, and T. Boland, “In vivo assessment of printed microvasculature in a bilayer skin graft to treat full-thickness wounds,” Tissue Eng. - Part A, vol. 21, no. 1–2, pp. 224–233, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Park et al., “A comparative study on collagen type i and hyaluronic acid dependent cell behavior for osteochondral tissue bioprinting,” Biofabrication, vol. 6, no. 3, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, D. Jia, L. Li, and M. Wang, “Advances in Nanomedicine and Biomaterials for Endometrial Regeneration: A Comprehensive Review,” Int. J. Nanomedicine, vol. 19, pp. 8285–8308, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Qiao et al., “Enhancing thermal stability and mechanical resilience in gelatin/starch composites through polyvinyl alcohol integration,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 344, no. January, p. 122528, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Silva, “Regenerative medicine,” J. Transl. Med., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xiayi xu et al., “Dynamic gelatin-based hydrogels promote the proliferation and self-renewal of embryonic stem cells in long-term 3D culture,” Biomaterials, vol. 289, no. September, p. 121802, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Singhvi, S. S. Zinjarde, and D. V. Gokhale, “Polylactic acid: synthesis and biomedical applications,” J. Appl. Microbiol., vol. 127, no. 6, pp. 1612–1626, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Pawar, S. U. Tekale, S. U. Shisodia, J. T. Totre, and A. J. Domb, “Biomedical applications of poly(lactic acid),” Rec. Pat. Regen. Med., vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 40–51, 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Nair and C. T. Laurencin, “Biodegradable polymers as biomaterials,” Prog. Polym. Sci., vol. 32, no. 8–9, pp. 762–798, 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Hussain, S. M. Khan, M. Shafiq, and N. Abbas, “A review on PLA-based biodegradable materials for biomedical applications,” Giant, vol. 18, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. da Silva et al., “Biocompatibility, biodegradation and excretion of polylactic acid (PLA) in medical implants and theranostic systems,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 340, pp. 9–14, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Kheilnezhad and A. Hadjizadeh, “A review: Progress in preventing tissue adhesions from a biomaterial perspective,” Biomater. Sci., vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 2850–2873, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Pal, N. Kankariya, S. Sanwaria, B. Nandan, and R. K. Srivastava, “Control on molecular weight reduction of poly(ε-caprolactone) during melt spinning - A way to produce high strength biodegradable fibers,” Mater. Sci. Eng. C, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 4213–4220, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Rahaman and H. Tsuji, “Synthesis and Characterization of Stereo Multiblock Poly(lactic acid)s with Different Block Lengths by Melt Polycondensation of Poly(L-lactic acid)/Poly(D-lactic acid) Blends,” Macromol. React. Eng., vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 446–457, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Goyanes, A. B. M. Buanz, A. W. Basit, and S. Gaisford, “Fused-filament 3D printing (3DP) for fabrication of tablets,” Int. J. Pharm., vol. 476, no. 1, pp. 88–92, 2014. [CrossRef]

- U. Nöth, L. Rackwitz, A. F. Steinert, and R. S. Tuan, “Cell delivery therapeutics for musculoskeletal regeneration,” Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., vol. 62, no. 7–8, pp. 765–783, 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Xu, K. Crawford, and C. B. Gorman, “Effects of temperature and pH on the degradation of poly(lactic acid) brushes,” Macromolecules, vol. 44, no. 12, pp. 4777–4782, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Leprince et al., “Preliminary design of a new degradable medical device to prevent the formation and recurrence of intrauterine adhesions,” Commun. Biol., vol. 2, no. 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Kaczmarek, M. Nowicki, I. Vuković-Kwiatkowska, and S. Nowakowska, “Crosslinked blends of poly(lactic acid) and polyacrylates: AFM, DSC and XRD studies,” J. Polym. Res., vol. 20, no. 3, 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Qin, L. Wu, and S. Jie, “Poly(glycolic acid) materials with melt reaction/processing temperature window and superior performance synthesized via melt polycondensation,” Polym. Degrad. Stab., vol. 220, no. November 2023, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kureha Corporation, “Polyglycolic Acid ( PGA ) - Technical Guidebook,” no. November 2011, p. 1, 2011, [Online]. Available: http://www.kuredux.com/pdf/Kuredux_technical_EN.pdf.

- K. J. Jem and B. Tan, “The development and challenges of poly (lactic acid) and poly (glycolic acid),” Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 60–70, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Yamane, H. Sato, Y. Ichikawa, K. Sunagawa, and Y. Shigaki, “Development of an industrial production technology for high-molecular-weight polyglycolic acid,” Polym. J., vol. 46, no. 11, pp. 769–775, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Amiri et al., “Evaluation of polyglycolic acid as an animal-free biomaterial for three-dimensional culture of human endometrial cells,” Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med., vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 259–269, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Supra and D. K Agrawal, “Peripheral Nerve Regeneration: Opportunities and Challenges,” J. Spine Res. Surg., vol. 05, no. 01, pp. 10–18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Lee et al., “Synthesis and in vitro characterizations of porous carboxymethyl cellulose-poly(ethylene oxide) hydrogel film,” Biomater. Res., vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Rahman et al., “Recent developments of carboxymethyl cellulose,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 13, no. 8, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Yuwono, E. Wahyuningsih, Noviany, A. A. Kiswandono, W. Simanjuntak, and S. Hadi, “Characterization of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) synthesized from microcellulose of cassava peel,” Mater. Plast., vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 225–235, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Toǧrul and N. Arslan, “Production of carboxymethyl cellulose from sugar beet pulp cellulose and rheological behaviour of carboxymethyl cellulose,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 73–82, 2003. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Liu and R. A. Berg, “Adhesion barriers of carboxymethylcellulose and polyethylene oxide composite gels,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res., vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 326–332, 2002. [CrossRef]

- A. Di Spiezio Sardo et al., “Efficacy of a Polyethylene Oxide-Sodium Carboxymethylcellulose Gel in Prevention of Intrauterine Adhesions After Hysteroscopic Surgery,” J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol., vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 462–469, 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. Fuchs et al., “Intercoat (Oxiplex/AP Gel) for Preventing Intrauterine Adhesions After Operative Hysteroscopy for Suspected Retained Products of Conception: Double-Blind, Prospective, Randomized Pilot Study,” J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 126–130, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Fujii, Y. Taga, Y. K. Takagi, R. Masuda, S. Hattori, and T. Koide, “The Thermal Stability of the Collagen Triple Helix Is Tuned According to the Environmental Temperature,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 23, no. 4, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, S. Cheong NG, J. Yu, and W. B. Tsai, “Modification and crosslinking of gelatin-based biomaterials as tissue adhesives,” Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces, vol. 174, no. October 2018, pp. 316–323, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Kurowiak, T. Klekiel, and R. Będziński, “Biodegradable Polymers in Biomedical Applications: A Review—Developments, Perspectives and Future Challenges,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 24, no. 23, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Xu et al., “Injectable Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Laden Matrigel Microspheres for Endometrium Repair and Regeneration,” vol. 2000202, pp. 1–11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Raval, J. Parikh, and C. Engineer, “Mechanism of controlled release kinetics from medical devices,” Brazilian J. Chem. Eng., vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 211–225, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fu and W. J. Kao, “Drug release kinetics and transport mechanisms of non-degradable and degradable polymeric delivery systems,” Expert Opin. Drug Deliv., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 429–444, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Huberlant et al., “In Vivo Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of a Novel Degradable Polymeric Film for the Prevention of Intrauterine Adhesions,” J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol., vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 1384–1390, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Weyers et al., “Safety and Efficacy of a Novel Barrier Film to Prevent Intrauterine Adhesion Formation after Hysteroscopic Myomectomy: The PREG1 Clinical Trial,” J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 151–157, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lisa et al., “4DryField vs. hyalobarrier gel for preventing the recurrence of intrauterine adhesions–a pilot study,” Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol., vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–7, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Mettler, A. Audebert, E. Lehmann-Willenbrock, K. Schive, and V. R. Jacobs, “Prospective clinical trial of SprayGel as a barrier to adhesion formation: An interim analysis,” J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 339–344, 2003. [CrossRef]

- G. Ahmad et al., “Barrier agents for adhesion prevention after gynaecological surgery,” Cochrane Database Syst. Rev., no. 2, 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Khunmanee, Y. Jeong, and H. Park, “Crosslinking method of hyaluronic-based hydrogel for biomedical applications,” J. Tissue Eng., vol. 8, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Fundarò, G. Salti, D. M. H. Malgapo, and S. Innocenti, “The Rheology and Physicochemical Characteristics of Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Their Clinical Implications,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 23, no. 18, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Biesiekierski, K. Munir, Y. Li, and C. Wen, Material selection for medical devices. LTD, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Biomaterials should not trigger adverse immune responses when interacting with the body, while also providing biological and functional benefits to the construct |

| Biodegradability | After interacting with the body, the biomaterial should degrade, and either be excreted or absorbed by the body |

| Lack of toxicity | The by-products generated by biomaterials should be non-toxic and pose no harm to the body or surrounding tissues |

| Mechanical properties | Biomaterials should have strong mechanical properties that match the structure of reproductive organ tissues and support their functions effectively |

| Biomimicry | Biomaterials should be designed to align with the anatomical and physiological characteristics of specific native tissues |

| Property | PLA | PLLA | PDLLA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melting temperature, (°C) | 150–162 | 170–200 | Amorphous |

| Glass transition temperature (°C) | 45–60 | 55–65 | 50–60 |

| Ultimate tensile strength, (MPa) | 21–60 | 15.5–150 | 27.6–50 |

| Tensile modulus (GPa) | 0.35–0.5 | 2.7–4.14 | 1–3.45 |

| Ultimate tensile strain (%) | 2.5–6 | 3.0–10.0 | 2.0–10.0 |

| Specific tensile modulus (kNm/g) | 0.28–2.8 | 0.80 | 2.23–3.85 |

| Property | PGA |

|---|---|

| Melting temperature, (°C) | 220 |

| Glass transition temperature (°C) | 40 |

| Heat deflection temperature (°C) | 168 |

| Tensile elongation, (%) | 2.1 |

| Tensile modulus (GPa) | 7.0 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 109 |

| Parameters | Effects |

|---|---|

| 1. Drug properties | Impacts the aqueous solubility, which subsequently influences various factors such as protein binding, tissue retention, localized drug concentration, and the kinetics of drug release. |

| Hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity | |

| Diffusion/dissolution characteristics | |

| Charge | |

| Stability | |

| Solubility in biopolymer matrix | |

| 2. Biopolymer properties | Biopolymers influence degradation, hydrophobicity, drug release, and drug solubility. |

| Thermal property | |

| Degree of crystallinity | |

| Molecular weight | |

| 3. Release medium | Influences the degradation profile of biopolymers and the solubility of drugs. |

| pH | |

| Temperature | |

| Ionic strength | |

| Enzymes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).