3.2. Qualitative Findings

Data analysis disclosed multiple and interconnected findings that align with the objectives of the study. The findings are organized into four main themes and subthemes (

Table 2). Some narratives are presented without the photo to ensure confidentiality. Additionally, group conversations and complementary experiences were included. A satisfaction questionnaire assessing the Photovoice sessions (

Table 3) is also presented.

3.2.1. Artmaking as an Artistic Couple

Creative and collaborative process

Participants emphasized the value of engaging in the creative process over focusing solely on the final product, aligning with participatory art principles. Participant 3 reflected: “Things do not appear; things are created,” highlighting the significance of the journey. Participant 4 described her experience:

“We started walking in the forest, collecting elements like pine cones and logs. From there, we built without a set plan, creating something with volume. I enjoyed the entire process—making the mold, turning it, and documenting it with my artistic partner’s photos.” (

Figure 1).

Participants found enjoyment in the "making-of" aspect of their work. For example, some participants expressed a preference for the process of creating, enjoying even the “behind-the-scenes” moments, sometimes valuing it more than the final artwork itself. This reflects a broader appreciation of the journey, as well as the therapeutic impact of engaging deeply with the process, capturing moments, and recording the stages of creation, which offered a lasting reminder of their efforts and growth.

The dynamic between clients and local artists also revealed power imbalances, as the artists’ expertise sometimes overshadowed collaborative efforts. Yet, these dynamics highlighted the balance between technical guidance and creative expression.

To express, to explain

Art served as a tool for participants to express emotions and thoughts difficult to articulate verbally. Participant 1 noted: “Art expresses what you cannot with words,”. Through art, they express not only their feelings but also attempt to make sense of them, thereby facilitating both self-understanding and communication with those around them. Art acts as a mirror of their internal states, enabling others to understand their experiences more accurately.

For Participant 25, art became a channel to release emotions from a difficult work situation:

“My work is called incomprehension. I didn’t know how to capture it, but after brainstorming, I realized it reflected my struggle at work, where colleagues didn’t treat me well. That’s when the idea to capture incomprehension in a painting came to me.”

Art through nature

Some participants engaged in the artistic process within a natural setting, which became a significant space for reflection, inspiration, and connection. Participants integrated natural elements into their practices, highlighting the interplay between nature and creativity. During a group discussion, Participant 1 shared a landscape photo alongside Vincent van Gogh’s quote (

Figure 2):

This sparked a debate about whether nature is art or merely a canvas for human creativity. While some, like Participant 1, viewed “nature as art,” others, like Participant 2, argued that “art is generated solely by human beings.”

3.2.2. Social Connections

A recurring theme among participants was the dynamic exchange of personal and artistic experiences within the artistic couple process. Some participants delved deeply into personal topics, while others maintained a primary focus on the art itself. These interactions often reflected the level of connection and trust developed between partners.

A conversation starts

Participant 23, the youngest participant at 19 years old, collaborated with two high school students (local artists) to create graffiti artwork. She described how their process began with a two-hour conversation, focusing on personal topics like dreams and emotions. This dialogue inspired their project, which explored adolescence through a character navigating emotional worlds such as anger, sadness, fear, euphoria, and shame. Participant 23 explained:

"When we started, we first got to know each other and spent two hours just talking. Only talking. We didn’t talk about the artwork; we talked about ourselves. We realized we had things in common. The topic of emotions came up, especially the world of dreams and the subconscious. The main idea was to create a character that went through different emotional worlds, representing adolescence. While we were sketching, I came up with the idea of 'teenmare,' which is a fusion of 'teenager' and 'nightmare. We depicted anger, which is a very common emotion among teenagers. Sadness was also included because it's a time when you begin to realize that life isn’t the world you thought it was when you were a child. Problems start to arise, and you have to decide what to do with your life. Fear was represented because adolescence brings many changes, and we have to try new things and choose our future. Fitting in with others also creates fear. Then there was euphoria and shame, the chains that stop you from being or doing what you want. I had never created an artistic piece with someone else before. I had always worked individually. Relationships are very difficult for me, but with them, it just clicked instantly. It was very easy, and everything went really well. I was nervous in this regard, but I came out delighted."

Their conversations laid the foundation for trust, collaboration, and creativity, blending personal insights with artistic expression to address the transitional challenges of adolescence.

To share with my artistic couple

Interactions between participants often extended beyond their artistic projects, fostering deeper personal connections. Such exchanges created spaces for trust and understanding. However, they also highlighted challenges. Participant 21 recounted an initial conflict with her partner, who treated her unequally due to her mental health:

“I said, ‘No, we are equal.’ People are not bad; they are ignorant.”

By addressing the comment directly, she fostered mutual respect, concluding: “The process went very well, and now we are friends.” This moment underscores the importance of open communication in challenging stigma and promoting understanding within partnerships.

Solitude

Participants reflected on solitude as both a challenge and an opportunity for growth. While some struggled with being alone, they also found it could foster creativity and self-expression. Several participants reflected on the role of solitude in their recovery, with some struggling to cope with it while others found it a source of creative inspiration. For some, solitude became a companion that fostered artistic expression and personal reflection. However, the Artistic Couples project provided a space to counteract loneliness by fostering social connections through shared creative experiences. Collaborative art-making not only strengthened participants' sense of belonging but also enhanced their mental well-being, offering a meaningful way to engage with others and the artistic community.

3.2.3. Understanding Mental Health Recovery

Mental health recovery is a deeply personal and multifaceted journey that intertwines emotional, social, and creative dimensions. The outcomes of this project reveal how participants navigated their individual paths, using art and meaningful activities as tools for self-expression, empowerment, and connection. Through their experiences, we gain insight into the complexities of recovery, from overcoming stigma and personal struggles to rediscovering identity and finding joy in everyday moments.

Overcoming my current situation

Participant 2 reflected on his lifelong relationship with music, sharing a photograph of the iconic His Master’s Voice logo, which holds personal significance from his time working at RCA Victor (

Figure 3). He explained:

“Music was the reason why they stigmatized and damaged my brain. But it’s also always been the center of my life.” As he grew older, personal circumstances distanced him from music. He shared, “I’ve really been a fish out of water for 15 years. That’s why it feels so good to be making music again and to have the whole studio set up. I feel like I am regaining my identity as a musician.” When he got the studio ready, he invited his artistic couple to work there. “And for me, this is a very, very significant aspect of my recovery because what I needed was to regain my artistic identity as a musician”.

Some participants experienced emotional challenges during their creative process. One participant was unable to complete their work due to personal reasons, while others had fewer meetings due to external circumstances.

“Don’t treat me this way”

Participant 22 shared her journey of coping with mental health stigma, using three symbolic photographs to illustrate her experiences. She recounted how her challenges began at 15 years old, with panic attacks, anxiety, and depression. Despite these struggles, she pursued her studies and career by “putting on a mask” to appear normal:

“Even when I was shattered inside, I would dress well, do my hair, put on makeup, and just carry on. Now, I know I have bipolar disorder, but it took me a long time to accept it.” Art became her refuge, “I use art to express my emotions and feelings but also as a way to entertain myself because I enjoy it.”. Her second photo, titled "Don’t Treat Me This Way," depicted a collage of stigmatizing phrases she had encountered, such as: “What you want is to avoid working” or “Others have it much worse than you”. In contrast, her third photo, "Get to Know Me First and Discover Who I Am," revealed empowering statements like: “I’m fun “, I want to make a difference” or “Ask me if you don’t understand”.

Reflecting on the Artistic Couples project, she acknowledged the sensitivity of participants but noted occasional moments of discomfort:

“They mean well, but it can still feel bad when they explain things as if you were a child.”

Her narrative highlights the dual role of art as a tool for self-expression and a means of confronting societal stigma, underscoring her resilience and the need for greater understanding.

Engaging in meaningful activities

Participants highlighted the importance of engaging in both artistic and non-artistic activities to support mental health recovery and provide meaningful ways to occupy their time. Examples included:

Listening to music: “Music makes me feel powerful emotions with every song I love,” said Participant 3, who chose colourful vinyl records to represent its impact (

Figure 4).

Climbing: Participant 1 also described the exhilaration of a via ferrata: “It’s the adrenaline, feeling alive, and enjoying nature.”

Other activities: Archery, visiting museums, and spending time in nature were also mentioned as meaningful practices.

These activities not only provided enjoyment but also contributed to participants’ emotional well-being and connection to the world around them.

3.3. Quantitative Findings

The pre- and post-intervention analysis provide insights into the project's impact on participants' mental health recovery, quality of life, and self-stigma (

Table 4). Seventeen out of thirty participants completed the questionnaires, while the remaining participants did not complete the test due to difficulties in understanding it. Moreover, a satisfaction questionnaire assessing participants' experiences in the project (

Table 5) and a measure of PREMs (

Table 6) were included. It is the latter that highlights the high levels of pleasure and well-being generated by the experience received in the research. Although overall recovery as measured by the QPR and RAS-DS showed no statistically significant changes, the 'Connecting and Belonging' subdomain of the RAS-DS revealed a notable improvement (t= -2.51, p=0.023), suggesting that participants experienced increased social integration and support. The overall recovery as measured by the RAS-DS (Recovery Assessment Scale—Domains and Stages) showed an increase in mean scores from 111.18 (SD = 19.69) pre-intervention to 116.71 (SD = 17.82) post-intervention, with the median rising from 113 to 118. Although the improvement was not statistically significant (t = -1.525, p=0.147), this increase in scores suggests a positive trend in participants’ perceived recovery. Regarding quality of life and psychological well-being, no significant changes were observed in the overall EQ-5D and PWB scores. Lastly, self-stigma levels, as assessed by the ISMI, remained stable across all domains, indicating that while stigma reduction was not significant, the intervention did not exacerbate negative self-perceptions.

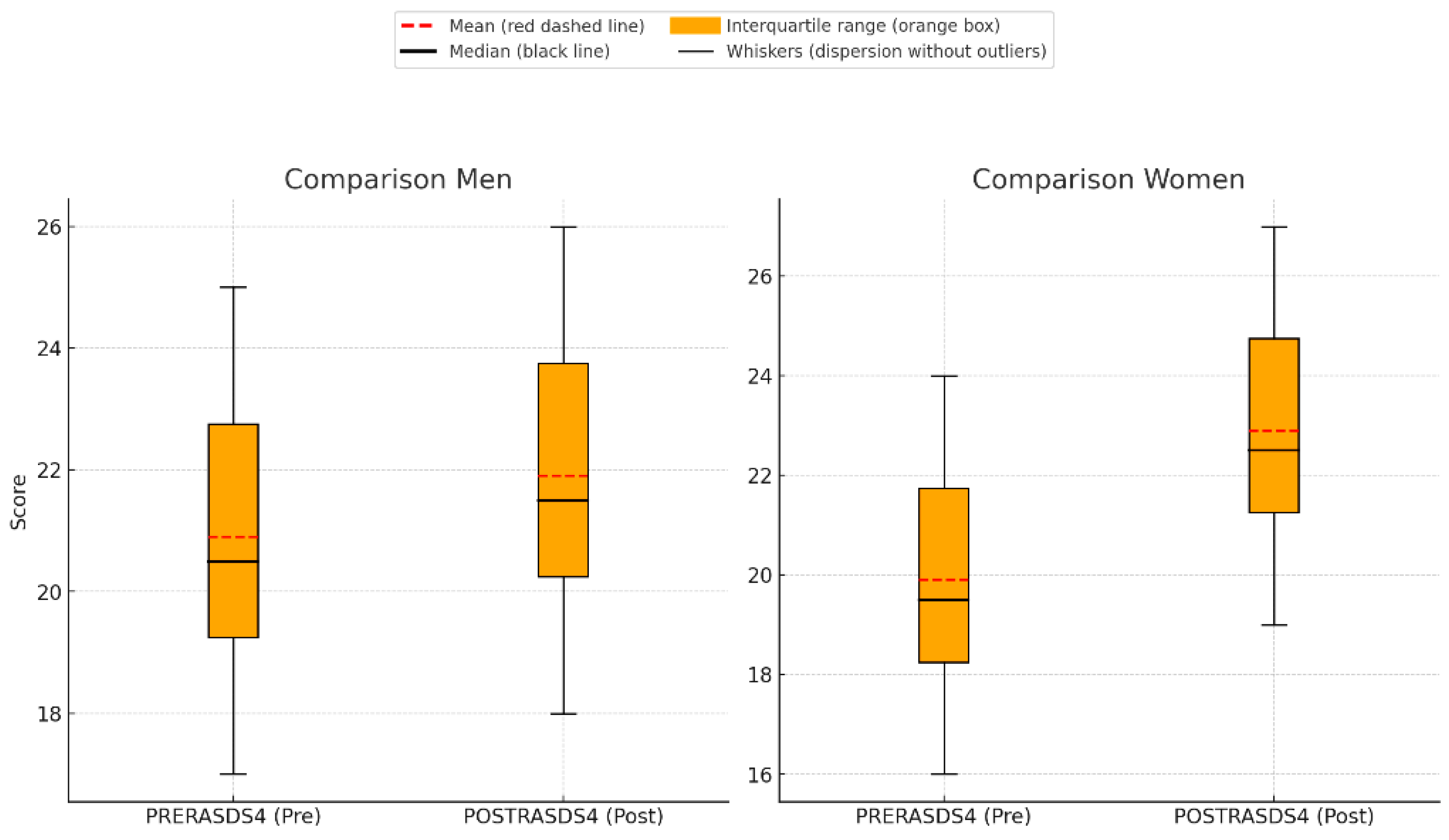

The analysis of the RAS-DS 'Connecting and Belonging' subscale revealed significant differences in recovery trajectories based on gender. Women demonstrated a statistically significant improvement, with mean scores increasing from 20.20 (SD = 3.39) pre-intervention to 22.30 (SD = 3.23) post-intervention (t = -2.85, p = 0.019) (

Figure 5). In contrast, men showed no significant change, with mean scores shifting only slightly from 21.00 (SD = 3.16) to 21.43 (SD = 3.36) (t = -0.55, p = 0.604). The direct comparison of improvements between genders yielded no statistically significant differences (t = -1.55, p = 0.142), though women exhibited a higher mean change (2.10 for women vs. 0.43 for men). Age-based analyses, including an ANOVA comparing three age subgroups (18–30, 31–50, and 51+), did not show statistically significant differences in recovery scores between groups (F = 0.45, p = 0.649 for all participants; F = 1.46, p = 0.295 for women only). Notably, older women (51+) showed the highest mean improvement (4.50, SD = 3.54), whereas younger and middle-aged women (18–30 and 31–50) exhibited smaller changes (1.50, SD = 2.08, and 1.50, SD = 1.73, respectively). While these findings were not statistically significant, they suggest that age and gender may influence recovery experiences and warrant further exploration. The results show a low positive correlation between women's age and improvement in the subscale (r=0.278), but it is not statistically significant (p=0.436), indicating that there is not enough evidence to confirm a relationship between these variables in this sample.

The one-way ANOVA showed no significant differences in improvement across diagnostic categories (F = 1.264, p = 0.327). However, the Depressive Disorders group exhibited the highest improvement trend (M = 3.00).