Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation of Extracts

2.2. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

2.3. Determination of Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents

2.4. Determination of Antioxidant Activities

2.4.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.4.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

2.4.3. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

2.4.4. Cupric Reducing Antioxidant Capacity (CUPRAC)

2.4.5. Total Antioxidant Capacity by Phosphomolybden Assay

2.4.6. Metal Chelating Activity

2.5. Enzyme Inhibition Activities

2.5.1. AChE and BChE Inhibition Activities

2.5.2. α-Amylase Inhibition Activity

2.5.3. α-Glucosidase Inhibition Activity

2.5.4. Tyrosinase Inhibition Activity

2.6. Cytotoxicity and Antiviral Tests

2.6.1. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.6.2. Antiviral Activity Assay

2.7. The Statistical Analyses

3. Results

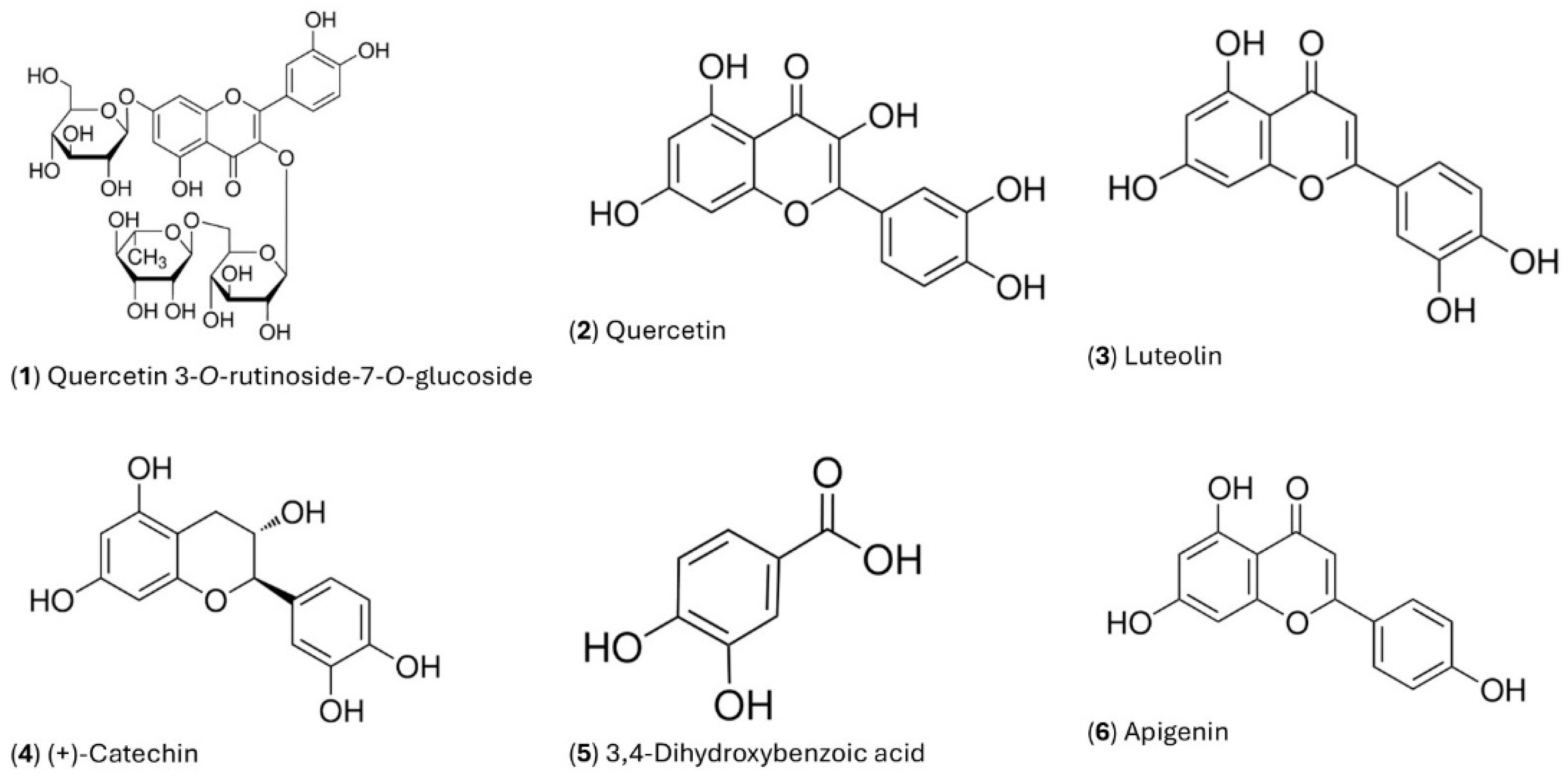

3.1. HPLC Analysis Results

3.2. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content Results

3.3. Antioxidant Activity Results

3.4. Enzyme Inhibition Activity Results

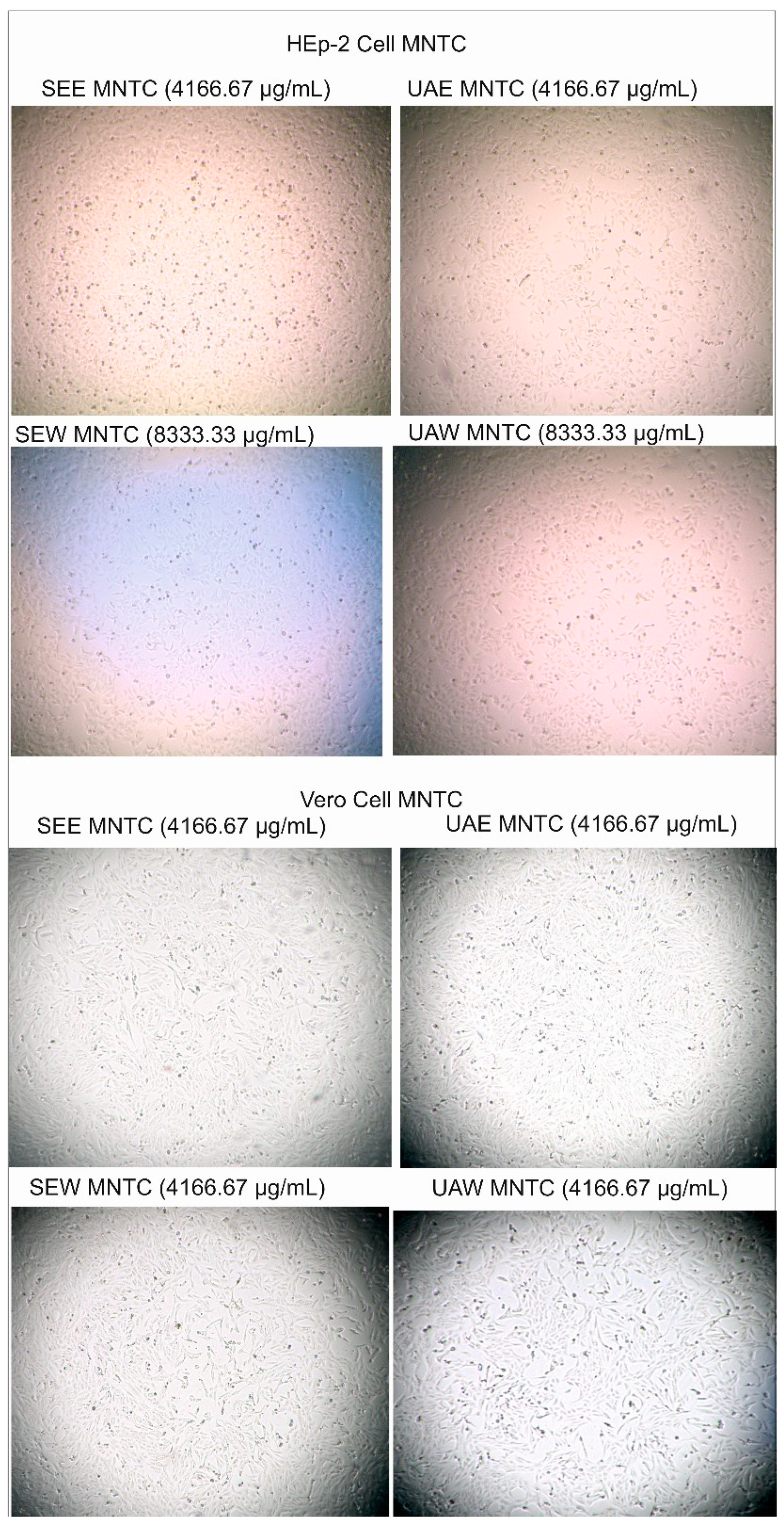

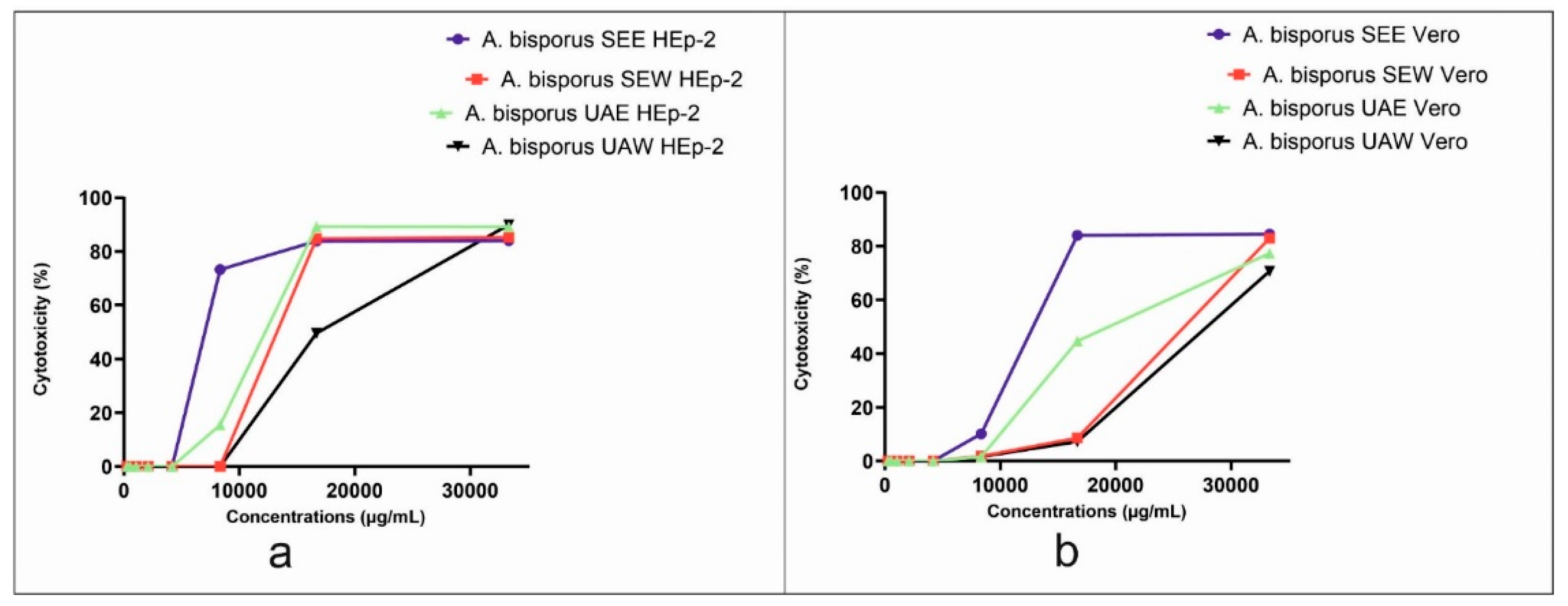

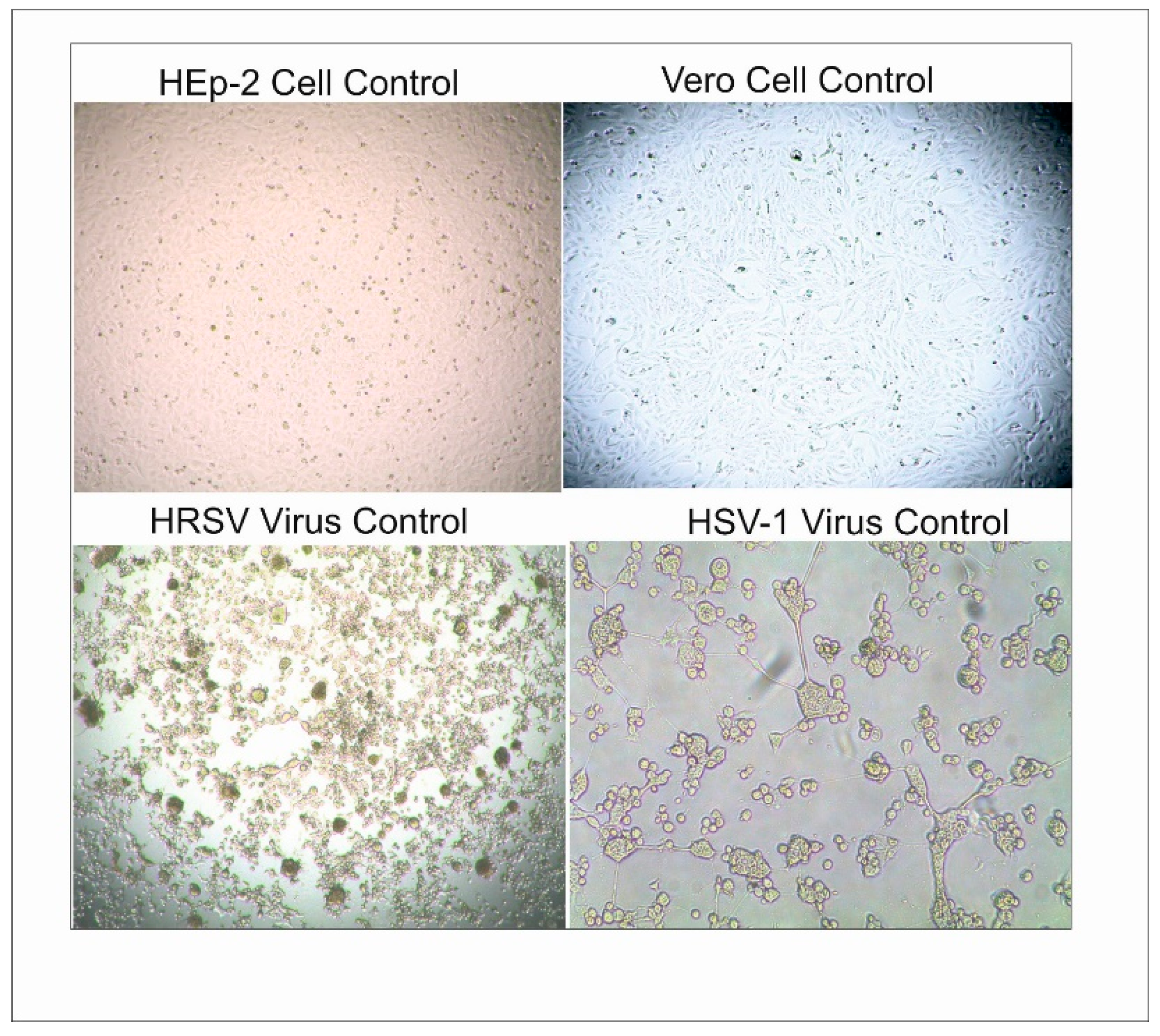

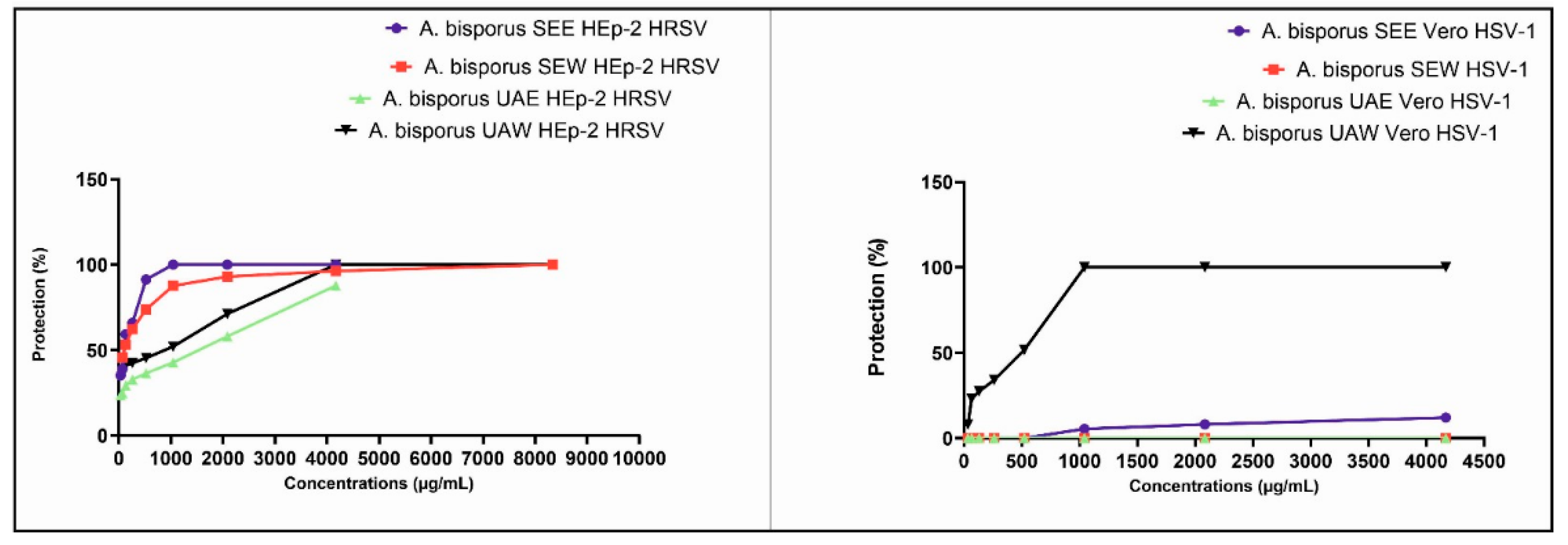

3.5. Cytotoxicity and Antiviral Activity Results

4. Discussion

4.1. HPLC Analysis Results

4.2. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content Results

4.3. Antioxidant Activity Results

4.4. Enzyme Inhibition Activity Results

4.5. Cytotoxicity and Antiviral Activity Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRSV | Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| HSV-1 | Herpes simplex virus type 1 |

| SEE | Soxhlet ethanol extract |

| SEW | Soxhlet water extract |

| UAE | Ultrasonic-assisted ethanol extract |

| UAW | Ultrasonic-assisted water extract |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| GAEs | Gallic acid equivalent |

| REs | Routine equivalent |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| DPPH | 2,2-difenil1-pikrilhidrazil |

| ABTS | 2,2‟-azinobis (3-etil-bezotiazolin 6 sulfonat) |

| CUPRAC | CUPric Reducing Antioxidant Capacity |

| TEs | Trolox equivalent |

| EDTAE | EDTA equivalent |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| GALAEs | Galantamine equivalent |

| ACEs | Acarbose equivalent |

| KAEs | Kojic acid equivalent |

| BChE | Butyrylcholinesterase |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| TPC | Total Phenolic Content |

| TFC | Total Flavonoid Content |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| HEp-2 | Human Larynx Epidermoid Carcinoma Cell Line |

| Vero | African Green Monkey Kidney Cell |

| MNTC | Maximum non-toxic concentration |

| CC50 | 50% Cytotoxic Concentration |

| EC50 | 50% Effective Concentration |

| SI | Selective index |

| RBV | Ribavirin |

| ACV | Acyclovir |

References

- Pinya, S.; Ferriol, P.; Tejada, S.; Sureda, A. Mushrooms reishi (Ganoderma lucidum), shiitake (Lentinela edodes), maitake (Grifola frondosa). In Nonvitamin and nonmineral nutritional supplements; Elsevier: 2019; pp. 517-526.

- Stojković, D.; Reis, F.S.; Glamočlija, J.; Ćirić, A.; Barros, L.; Van Griensven, L.J.; Ferreira, I.C.; Soković, M. Cultivated strains of Agaricus bisporus and A. brasiliensis: chemical characterization and evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial properties for the final healthy product–natural preservatives in yoghurt. Food & function 2014, 5, 1602-1612.

- Harikrishnan, R.; Devi, G.; Van Doan, H.; Balasundaram, C.; Thamizharasan, S.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Abdel-Tawwab, M. Effect of diet enriched with Agaricus bisporus polysaccharides (ABPs) on antioxidant property, innate-adaptive immune response and pro-anti inflammatory genes expression in Ctenopharyngodon idella against Aeromonas hydrophila. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 2021, 114, 238-252. [CrossRef]

- Khatua, S.; Paul, S.; Acharya, K. Mushroom as the potential source of new generation of antioxidant: a review. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology 2013, 6, 496-505.

- Usman, M.; Murtaza, G.; Ditta, A. Nutritional, medicinal, and cosmetic value of bioactive compounds in button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus): a review. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 5943.

- Muszyńska, B.; Kała, K.; Rojowski, J.; Grzywacz-Kisielewska, A.; Opoka, W. Composition and biological properties of Agaricus bisporus fruiting bodies: a review. 2017. [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Condict, L.; Richardson, S.J.; Brennan, C.S.; Kasapis, S. Molecular characterization of interactions between lectin-a protein from common edible mushroom (Agaricus bisporus)-and dietary carbohydrates. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 146, 109253. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Jubair, A.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M.M.; Azam, M.S.; Biswas, M. Free radical-scavenging capacity and HPLC-DAD screening of phenolic compounds from pulp and seed of Syzygium claviflorum fruit. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2021, 6, 100203.

- Skendi, A.; Irakli, M.; Chatzopoulou, P. Analysis of phenolic compounds in Greek plants of Lamiaceae family by HPLC. Journal of applied research on medicinal and aromatic plants 2017, 6, 62-69. [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Sarikurkcu, C.; Aktumsek, A.; Ceylan, R.; Ceylan, O. A comprehensive study on phytochemical characterization of Haplophyllum myrtifolium Boiss. endemic to Turkey and its inhibitory potential against key enzymes involved in Alzheimer, skin diseases and type II diabetes. Industrial Crops and Products 2014, 53, 244-251. [CrossRef]

- Sarikurkcu, C.; Uren, M.C.; Tepe, B.; Cengiz, M.; Kocak, M.S. Phenolic content, enzyme inhibitory and antioxidative activity potentials of Phlomis nissolii and P. pungens var. pungens. Industrial Crops and Products 2014, 62, 333-340. [CrossRef]

- Berk, S.; Tepe, B.; Arslan, S.; Sarikurkcu, C. Screening of the antioxidant, antimicrobial and DNA damage protection potentials of the aqueous extract of Asplenium ceterach DC. African Journal of Biotechnology 2011, 10, 8902-8908.

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Özyürek, M.; Esin Karademir, S.; Erçağ, E. The cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity and polyphenolic content of some herbal teas. International journal of food sciences and nutrition 2006, 57, 292-304. [CrossRef]

- Vijayarathna, S.; Sasidharan, S. Cytotoxicity of methanol extracts of Elaeis guineensis on MCF-7 and Vero cell lines. Asian pacific journal of tropical biomedicine 2012, 2, 826-829. [CrossRef]

- Andrighetti-Fröhner, C.; Antonio, R.; Creczynski-Pasa, T.; Barardi, C.; Simões, C. Cytotoxicity and potential antiviral evaluation of violacein produced by Chromobacterium violaceum. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2003, 98, 843-848. [CrossRef]

- Artun, T.; Karagoz, A.; Ozcan, G.; Melikoglu, G.; Anil, S.; Kultur, S.; Sutlupinar, N. In vitro anticancer and cytotoxic activities of some plant extracts on HeLa and Vero cell lines. Journal of BU ON.: official journal of the Balkan Union of Oncology 2016, 21, 720-725.

- Ho, W.S.; Xue, J.Y.; Sun, S.S.; Ooi, V.E.; Li, Y.L. Antiviral activity of daphnoretin isolated from Wikstroemia indica. Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives 2010, 24, 657-661.

- Rukunga, G.; Simons, A.J. The potential of plants as a source of antimalarial agents: a review; PlantaPhile Publications Berlin, Germany: 2006.

- Čanadanović-Brunet, J.M.; Djilas, S.M.; Ćetković, G.S.; Tumbas, V.T.; Mandić, A.I.; Čanadanović, V.M. Antioxidant activities of different Teucrium montanum L. extracts. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2006, 41, 667-673.

- Naithani, R.; Mehta, R.G.; Shukla, D.; Chandersekera, S.N.; Moriarty, R.M. Antiviral activity of phytochemicals: a current perspective. Dietary components and immune function 2010, 421-468.

- Lin, L.-T.; Hsu, W.-C.; Lin, C.-C. Antiviral natural products and herbal medicines. Journal of traditional and complementary medicine 2014, 4, 24-35.

- Loaiza-Cano, V.; Monsalve-Escudero, L.M.; Filho, C.d.S.M.B.; Martinez-Gutierrez, M.; Sousa, D.P.d. Antiviral role of phenolic compounds against dengue virus: A review. Biomolecules 2020, 11, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.-Y.; Rhim, J.-Y.; Park, W.-B. Antiherpetic activities of flavonoids against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) in vitro. Archives of pharmacal research 2005, 28, 1293-1301. [CrossRef]

- Palacios, I.; Lozano, M.; Moro, C.; D’Arrigo, M.; Rostagno, M.; Martínez, J.A.; García-Lafuente, A.; Guillamón, E.; Villares, A. Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds occurring in edible mushrooms. Food chemistry 2011, 128, 674-678. [CrossRef]

- Reis, F.S.; Martins, A.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C. Antioxidant properties and phenolic profile of the most widely appreciated cultivated mushrooms: A comparative study between in vivo and in vitro samples. Food and chemical toxicology 2012, 50, 1201-1207. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jia, L.; Kan, J.; Jin, C.-h. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity of ethanolic extract of white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Food and chemical toxicology 2013, 51, 310-316. [CrossRef]

- Gąsecka, M.; Magdziak, Z.; Siwulski, M.; Mleczek, M. Profile of phenolic and organic acids, antioxidant properties and ergosterol content in cultivated and wild growing species of Agaricus. European Food Research and Technology 2018, 244, 259-268. [CrossRef]

- Elhusseiny, S.M.; El-Mahdy, T.S.; Awad, M.F.; Elleboudy, N.S.; Farag, M.M.; Aboshanab, K.M.; Yassien, M.A. Antiviral, cytotoxic, and antioxidant activities of three edible agaricomycetes mushrooms: Pleurotus columbinus, Pleurotus sajor-caju, and Agaricus bisporus. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7, 645.

- Kutluer, F. Effect of formaldehyde exposure on phytochemical content and functional activity of Agaricus bisporus (Lge.) Sing. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2024, 31, 35581-35594. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Ramírez, A.; Pavo-Caballero, C.; Baeza, E.; Baenas, N.; Garcia-Viguera, C.; Marín, F.R.; Soler-Rivas, C. Mushrooms do not contain flavonoids. Journal of functional foods 2016, 25, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthi, R.; Srinivash, M.; Mahalingam, P.U.; Malaikozhundan, B. Dietary nutrients in edible mushroom, Agaricus bisporus and their radical scavenging, antibacterial, and antifungal effects. Process Biochemistry 2022, 121, 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, H.; Modi, N.; Rawal, R. Evaluation of Chemical Constituents, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Agaricus bisporus (JE Lange). Indian Journal of Natural Sciences 2023, 14, 66958-66967.

- Agboola, O.O.; Sithole, S.; Mugivhisa, L.; Amoo, S.; Olowoyo, J. Growth, nutritional and antioxidant properties of Agaricus bisporus (crimini and white) mushrooms harvested from soils collected around mining areas in South Africa. Measurement: Food 2023, 9, 100078. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant properties from mushrooms. Synthetic and systems biotechnology 2017, 2, 13-22. [CrossRef]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Niksic, M.; Jakovljevic, D.; Helsper, J.P.; Van Griensven, L.J. Antioxidative and immunomodulating activities of polysaccharide extracts of the medicinal mushrooms Agaricus bisporus, Agaricus brasiliensis, Ganoderma lucidum and Phellinus linteus. Food chemistry 2011, 129, 1667-1675. [CrossRef]

- Dorman, H.; Peltoketo, A.; Hiltunen, R.; Tikkanen, M. Characterisation of the antioxidant properties of de-odourised aqueous extracts from selected Lamiaceae herbs. Food chemistry 2003, 83, 255-262. [CrossRef]

- Frankel, E.N.; Meyer, A.S. The problems of using one-dimensional methods to evaluate multifunctional food and biological antioxidants. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2000, 80, 1925-1941. [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska, A.; Jaszek, M.; Stefaniuk, D.; Ciszewski, T.; Matuszewski, Ł. Anticancer, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities of low molecular weight bioactive subfractions isolated from cultures of wood degrading fungus Cerrena unicolor. PloS one 2018, 13, e0197044. [CrossRef]

- Jegathchandran, H.; Madhushani, W.N.; Liyanage, G.S. Comparative study on the nutritional composition, antibacterial and antioxidant properties of four edible mushroom species: Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus eous, Agaricus bisporus and Lentinula edodes. 2024.

- Ekowati, N.; Yuniati, N.I.; Hernayanti, H.; Ratnaningtyas, N.I. Antidiabetic potentials of button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) on alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Biosaintifika: Journal of Biology & Biology Education 2018, 10, 655-662. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Duru, M.E.; Kivrak, Ş.; Mercan-Doğan, N.; Türkoglu, A.; Özler, M.A. In vitro antioxidant, anticholinesterase and antimicrobial activity studies on three Agaricus species with fatty acid compositions and iron contents: A comparative study on the three most edible mushrooms. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2011, 49, 1353-1360. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jang, M.J.; Park, Y.J. In vitro α-amylase, α-glucosidase, pancreatic lipase, xanthine oxidase inhibiting activity of Agaricus bisporus extracts. Mycobiology 2023, 51, 60-66.

- Alkan, H.; Zengin, G.; Kaşık, G. Antioxidant and in vitro some enzyme inhibitory activities of methanolic extract of cultivated Lentinula edodes. J Fungus 2017, 8, 90-98.

- Özparlak, H.; Alkan, S.; Zengin, G.; Aktümsek, A. Türkiye’deki yabani ve kültüre alınmış Ganoderma lucidum’un sulu ekstraktlarının in vitro bazı enzim inhibitör özelliklerinin karşılaştırılması. Mantar Dergisi 2016, 7, 110-117.

- Wei, Q.; Zhan, Y.; Chen, B.; Xie, B.; Fang, T.; Ravishankar, S.; Jiang, Y. Assessment of antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of Agaricus blazei Murill extracts. Food science & nutrition 2020, 8, 332-339. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, D.; Chawla-Sarkar, M.; Chatterjee, T.; Dey, R.S.; Bag, P.; Chakraborti, S.; Khan, M.T.H. Recent advancements for the evaluation of anti-viral activities of natural products. New Biotechnology 2009, 25, 347-368. [CrossRef]

- del Mar Delgado-Povedano, M.; de Medina, V.S.; Bautista, J.; Priego-Capote, F.; de Castro, M.D.L. Tentative identification of the composition of Agaricus bisporus aqueous enzymatic extracts with antiviral activity against HCV: A study by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry in high resolution mode. Journal of Functional Foods 2016, 24, 403-419.

- Lopez-Tejedor, D.; Claveria-Gimeno, R.; Velazquez-Campoy, A.; Abian, O.; Palomo, J.M. In vitro antiviral activity of tyrosinase from mushroom Agaricus bisporus against hepatitis C virus. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 759. [CrossRef]

- Gallego, P.; Rojas, Á.; Falcón, G.; Carbonero, P.; García-Lozano, M.R.; Gil, A.; Grande, L.; Cremades, O.; Romero-Gómez, M.; Bautista, J.D. Water-soluble extracts from edible mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) as inhibitors of hepatitis C viral replication. Food & Function 2019, 10, 3758-3767. [CrossRef]

- Elhusseiny, S.M.; El-Mahdy, T.S.; Elleboudy, N.S.; Yahia, I.S.; Farag, M.M.; Ismail, N.S.; Yassien, M.A.; Aboshanab, K.M. In vitro anti SARS-CoV-2 activity and docking analysis of Pleurotus ostreatus, Lentinula edodes and Agaricus bisporus edible mushrooms. Infection and Drug Resistance 2022, 3459-3475. ttps://doi.org/10.2147/idr.s362823.

- Doğan, H.H.; Duman, R.; Tuncer, P. Effect of Morchella conica and Fomes Fomentarius Extracts Against The Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus In-Vitro. Int J Pharm Sci Res 2018, 9, 5240-5245.

- Doğan, H.H.; Karagöz, S.; Duman, R. In vitro evaluation of the antiviral activity of some mushrooms from Turkey. International journal of medicinal mushrooms 2018, 20. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.H. Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2003, 78, 517S-520S. [CrossRef]

- Louten, J. Virus replication. Essential human virology 2016, 49.

- Gong, P.; Wang, S.; Liu, M.; Chen, F.; Yang, W.; Chang, X.; Liu, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. Extraction methods, chemical characterizations and biological activities of mushroom polysaccharides: A mini-review. Carbohydrate Research 2020, 494, 108037. [CrossRef]

| Phenolics (mg/g extracts) | SEE | SEW | UAE | UAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic Acid | 0.388±0.019ay | 0.005±0.001by | 0.111±0.008bx | 0.050±0.003cx |

| Homogentisic Acid | 0.495±0.073ay | 0.222±0.008bx | 0.225±0.019bx | 0.194±0.021bx |

| 3.4 Dihidroxybenzoic Acid (5) | 0.261±0.012ay | 0.031±0.006bx | 0.049±0.001ax | 0.631±1.003ax |

| Chlorogenic Acid | 0.448±0.066ay | 0.008±0.003bx | 0.113±0.064ax | 0.017±0.008bx |

| Quercetin-3-O-Rutinoside 7-O-Glucoside (1) | 1.015±0.158ay | 0.049±0.043bx | 0.217±0.102ax | 0.283±0.146ax |

| (+)-Catechin (4) | 0.666±0.098y | nd | 0.138±0.120bx | 0.141±0.006b |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic Acid | 0.379±0.056y | nd | 0.057±0.068ax | Nd |

| Vanillic Acid | 0.350±0.052 | nd | Nd | 0.004±0.003 |

| Epicatechin | 0.197±0.066 | nd | Nd | 0.053±0.025 |

| Rutin | 0.151±0.128 | nd | Nd | 0.138±0.151 |

| Ferulic Acid | Nd | nd | Nd | Nd |

| Isoquercitrin | 0.123±0.076 | nd | Nd | Nd |

| Naringin | 0.017±0.027 | nd | Nd | Nd |

| Quercitrin | 0.515±0.112y | Nd | 0.128±0.050ax | 0.137±0.119a |

| Myricetin | 0.201±0.046y | Nd | 0.038±0.045x | Nd |

| Quercetin (2) | 0.783±0.143ax | 0.447±0.056bx | 1.163±0.327ax | 1.184±0.506ax |

| Apigenin (6) | 0.232±0.147ay | 0.096±0.012by | 0.319±0.117ax | 0.317±0.124ax |

| Caffeic Acid | 0.257±0.055y | Nd | 0.056±0.014ax | 0.048±0.042a |

| Hyperoside | 0.231±0.076 | Nd | nd | 0.061±0.058 |

| Quercetin-3-O-Glucopyranoside | 0.281±0.079 | Nd | nd | 0.044±0.047 |

| Luteolin (3) | 0.661±0.103x | Nd | 0.691±0.087ax | 0.701±0.163a |

| SEE | SEW | UAE | UAW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total phenolic contents (mg GAEs/g extracts |

13.84±0.11ax | 9.56±0.06by | 11.60±0.05ax | 13.82±0.14ax |

|

Total flavonoid contents (mg REs/g extracts) |

0.73±0.03ax | 0.08±0.07bx | 0.38±0.04ax | 0.23±0.06ax |

| SEE | SEW | UAE | UAW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DPPH (mg TEs/g extract) |

20.29±1.69ax | 17.24±0.27ax | 13.81±1.45ay | 16.80±1.81ax |

|

ABTS (mg TE/g extract) |

48.33±3.03ax | 47.41±3.23ax | 37.32±2.70ax | 47.34±3.01ax |

|

FRAP (mg TEs/g extract) |

29.15±1.98 ax | 23.32±0.79 ax | 33.95±0.04 ax | 22.52±0.20 bx |

|

CUPRAC (mg TEs/g extract) |

54.35±1.24ax | 29.61±0.39bx | 49.71±0.59ax | 32.21±0.21ax |

|

Phosphomolybdate (mg TEs/g extract) |

1.44±0.06ax | 0.29±0.00bx | 1.41±0.08ax | 0.56±0.05ax |

|

Metalchelating (mg EDTAE/g extract) |

14.02±0.38ax | 29.55±0.04bx | 15.15±0.11ax | 25.68±0.20ax |

| SEE | SEW | UAE | UAW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AChE inhibition (mg GALAEs/g extract) |

2.56±0.02a | 0.52±0.02ax | na | 0.44±0.02x |

|

BChE inhibition (mg GALAEs/g extract) |

5.93±0.09x | na | 6.34±0.08x | na |

|

Amylase inhibition (mmol ACEs/g extract) |

0.27±0.02ax | 0.05±0.00bx | 0.29±0.00ax | 0.07±0.01ax |

|

Glucosidase inhibition (mg ACEs/g extract) |

1.03±0.00x | na | 0.98±0.05x | na |

|

Tyrosinase inhibition (mg KAEs/g extract) |

51.97±0.80ax | 12.46±0.91bx | 50.42±0.39ax | 8.84±0.57bx |

|

Metalchelating (mg EDTAE/g extract) |

14.02±0.38ax | 29.55±0.04bx | 15.15±0.11ax | 25.68±0.20ax |

| Cytotoxicity | Antiviral activity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRSV | ||||

| Extracts | MNTC (µg/mL) |

CC50 (µg/mL) |

EC50 (µg/mL) |

SI |

| SEE | 4166.67 | 7211 | 86.23 | 83.62 |

| SEW | 8333.33 | 14079 | 103.6 | 135.90 |

| UAE | 4166.67 | 11381 | 830.8 | 13.70 |

| UAW | 8333.33 | 17035 | 358.7 | 47.49 |

| RBV | 0.98 | 117 | 4.19 | 27.92 |

| HSV-1 | ||||

|

MNTC (µg/mL) |

CC50 (µg/mL) |

EC50 (µg/mL) |

SI | |

| SEE | 4166.67 | 12371 | 32302 | 0.38 |

| SEW | 4166.67 | 25213 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| UAE | 4166.67 | 19453 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| UAW | 4166.67 | 27880 | 324.7 | 85.86 |

| ACV | 31.25 | 1948 | 0.1967 | >1000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).