Submitted:

28 July 2023

Posted:

01 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

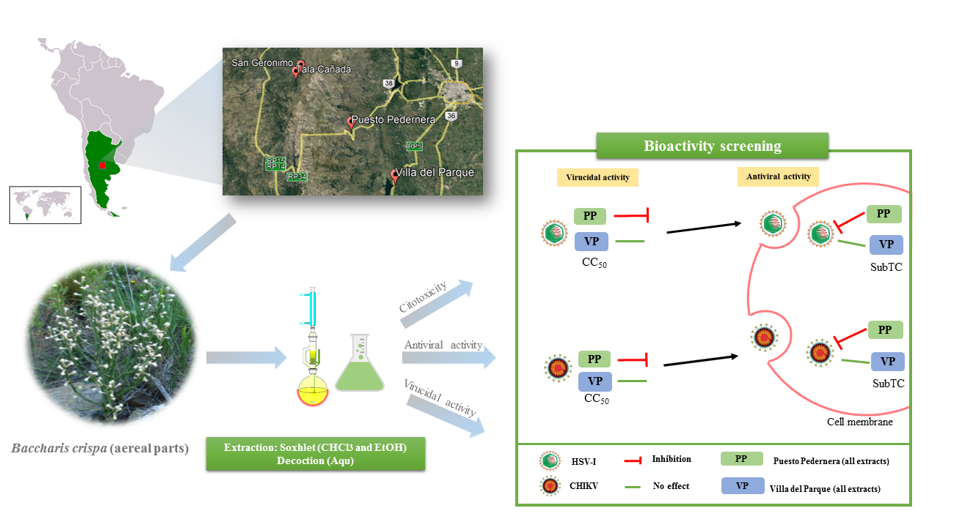

2.1. Plant material

2.2. Preparation of plant extracts

2.2.1. Organic Extracts

2.2.2. Aqueous Extract

2.3. Phytochemical screening

2.4. Cells and viruses

2.5. Sample solutions

2.6. In vitro Cytotoxicity assay

2.7. Plaque reduction assay

2.7.1. Antiviral assays

2.7.2. Viral inactivation activity

2.8. Positive controls

2.9. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cytotoxicity assay

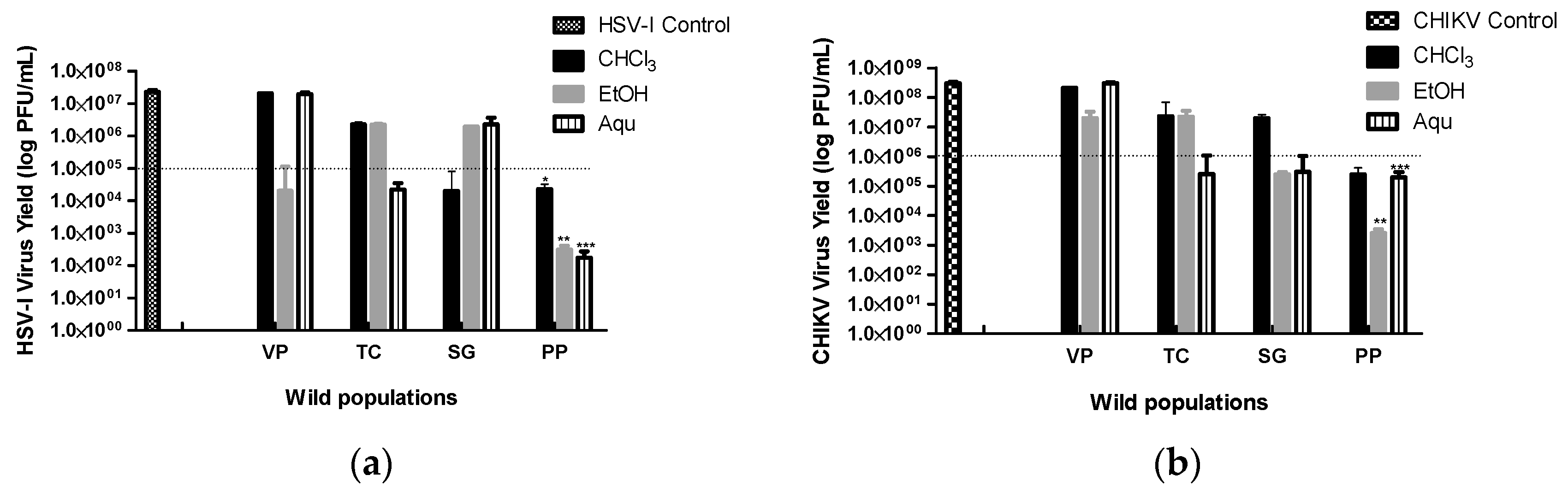

3.2. Plaque Reduction assay

3.2.1. Antiviral assays

3.2.2. Viral inactivation assay

3.3. Phytochemical screening

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ben Sassi, A.B.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F.; Bourgougnon, N.; Aouni, M. Antiviral activity of some Tunisian medicinal plants against Herpes simplex virus type 1. Nat. Prod. Res 2008, 22, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.K. Reasons for the increase in emerging and re-emerging viral infectious diseases. Microbes Infect 2006, 8, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.K.; Parveen, S. Evolution and Emergence of Pathogenic Viruses: Past, Present, and Future. Intervirology 2017, 60, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, 2018. Managing epidemics: key facts about major deadly diseases. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Sautto, G.; Mancini, N.; Gorini, G.; Clementi, M.; Burioni, R. Possible future monoclonal antibody (mAb)-based therapy against arbovirus infections. Biomed Res Int. 2013, 2013, 838491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketkar, H.; Herman, D.; Wang, P. Genetic Determinants of the Re-Emergence of Arboviral Diseases. Viruses 2019, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.W. The Newala epidemic: III. The virus: isolation, pathogenic properties and relationship to the epidemic. J. Hyg (Lond) 1956, 54, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arankalle, V.A.; Shrivastava, S.; Cherian, S.; Gunjikar, R.S.; Walimbe, A.M.; Jadhav, S.M.; Sudeep, A.B.; Mishra, A.C. Genetic divergence of Chikungunya viruses in India (1963–2006) with special reference to the 2005–2006 explosive epidemic. J. Gen. Virol 2007, 88, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochedez, P.; Hausfater, P.; Jaureguiberry, S.; Gay, F.; Datry, A.; Danis, M.; Bricaire, F.; Bossi, P. Cases of chikungunya fever imported from the islands of the South West Indian Ocean to Paris, France. Euro. Surveill 2007, 12, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Toloza, P.; Clouet-Huerta, D.E.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J. Chikungunya, the emerging migratory rheumatism. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; Paniz-Mondolfi, A.E. Venezuela: far from the path to dengue and chikungunya control. J. Clin. Virol 2015, 66, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, I.N. Dengue, Zika, Chikungunya y El Desarrollo De Vacunas. Medicina 2018, 78, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, G.; Turriziani, O. Antiviral therapy: old and current Issues. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2012, 40, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilukuri, S.; Rosen, T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol. Clin. 2003, 21, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Chen, W.; Liang, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Hong, H.; Xie, L.; Nie, H.; Xiong, S. Preparation of a monoPEGylated derivative of cyanovirin-N and its virucidal effect on acyclovir-resistant strains of herpes simplex virus type 1. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitazato, K.; Wang, Y.; Kobayashi, N. Viral infectious disease and natural products with antiviral activity. Drug Discov. Ther. 2007, 1, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Tahir, I.M.; Shah, S.M.A.; Mahmood, Z.; Altaf, A.; Ahmad, K.; Munir, N.; Daniyal, M.; Nasir, S.; Mehboob, H. Antiviral potential of medicinal plants against HIV, HSV, influenza, hepatitis, and coxsackievirus: A systematic review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, K.S.; Sivasubramanian, S.; Vincent, S.; Murugan., S.B.; Giridaran., B.; Dinesh., S.; Gunasekaran., P.; Krishnasamy, K.; Sathishkumar, R. Anti—chikungunya activity of luteolin and apigenin rich fraction from Cynodon dactylon. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2015, 8, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troost, B.; Mulder, L.M.; Diosa-Toro, M.; Van de Pol, D.; Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Smit, J.M. Tomatidine, a natural steroidal alkaloid shows antiviral activity towards chikungunya virus in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Agrawal, M.; Almelkar, S.; Jeengar, M.K.; More, A.; Alagarasu, K.; Kumar, N.V.; Mainkar, P.S.; Parashar, D.; Cherian, S. In vitro and in vivo studies reveal α-Mangostin, a xanthonoid from Garcinia mangostana, as a promising natural antiviral compound against chikungunya virus. Virol. J. 2018, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vitto, L.A.; Petenatti, E.M.; Petenatti, M.E. Recursos Herbolarios de San Luis (República Argentina) Primera Parte: Plantas Nativas. Multequina 1997, 6, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, M.J.; Bermejo, P. Baccharis (Compositae): a review update. Arkivoc 2007, 7, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, M.J.; Bermejo, P.; Gonzales, E.; Iglesias, I.; Irurzun, A.; Carrasco, L. Antiviral activity of Bolivian plant extracts. Gen. Pharmacol 1999, 32, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abad, M.J.; Bermejo, P.; Sanchez Palomino, S.; Chiriboga, X.; Carrasco, L. Antiviral activity of some South American Medicinal Plants. Phytother. Res 1999, 13, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanon, S.M.; Ceriatti, F.S.; Rovera, M.; Sabini, L.J.; Ramos, B.A. Search for Antiviral activity of Certain Medicinal Plants from Córdoba, Argentina. Rev. Latinoam. Microbiol 1999, 41, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Montanha, J.A; Mentel, R.; Reiss, C.; Lindequist, U. Phytochemical screening and antiviral activity of some medicinal plants from the island Soqotra. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.V.; Domínguez, M.J.; Carbonari, J.L.; Sabini, M.C.; Sabini, L.I.; Zanon, S.M. Study of Antiviral and Virucidal Activities of Aqueous Extract of Baccharis articulata against Herpes suis virus. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 994–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintini Jaime, M.F. Actividad antiviral de plantas medicinales argentinas de la familia Asteraceae. Identificación de compuestos bioactivos y caracterización del mecanismo de acción. Doctoral thesis. Universidad de Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 2014.

- Simoni, I.C.; Aguiar, B.; Martineli de Araujo Navarro, A.; Martins Parreira, R.; Bittencourt Fernandes, M.J.; Frankland Sawaya, A.C.H.; Fávero, O.A. In vitro antiviral activity of propolis and Baccharis sp. extracts on animal herpesviruses. Arq. Inst. Biol. 2018, 85, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, C.R.; De Loreto Bordignon, S.A.; Roehe, P.M.; Montanha, J.A.; Cibulski, S.P.; Gosman, G. Chemical analysis and antiviral activity evaluation of Baccharis anómala. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1960–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, G.; Cantero, J.J.; Nuñez, C.; Ariza Espinar, L. Flora Medicinal de la provincia de Córdoba (Argentina). Pteridófitas y Antófitas silvestres o naturalizadas. Museo Botánico de Córdoba. Córdoba. 2006; pp: 323-329.

- Cowan, M.M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbial. Rev. 1999, 12, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzada, M.L.; Fabri, R.L.; Nogueira, M.; Konno, T.U.; Duarte, G.G.; Scio, E. Antibacterial, cytotoxic and phytochemical screening of some traditional medicinal plants in Brazil. Pharm. Biol. 2009, 47, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratera, E.L.; Ratera, M.O. Plantas de la flora argentina empleadas en medicina popular. Hemisferio Sur, Buenos Aires, Argentina. 1980.

- Del Vitto, L.A.; Petenatti, E.M.; Petenatti, M.E. Introducción a la Herboristería. Ser. Tec. Herbario UNSL 2002, 14, 10–61. [Google Scholar]

- Harborne, J.B. Phytochemical Methods – A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant Analysis, 2nd ed; Chapman and Hall, London. 1984.

- De Bessa, N.G.F. , Borges, J.C.M., Beserra, F. P., Carvalho, R H.A., Pereira, M.A.B., Fagundes, R., Alves, A. Prospecção fitoquímica preliminar de plantas nativas do cerrado de uso popular medicinal pela comunidade rural do assentamento vale verde-Tocantins. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais 2013, 15, 692–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contigiani, M.; Sabattini, M. 1977. Virulencia diferencial de cepas de virus Junín por marcadores biológicos en ratones y cobayos. Medicina 1977, 37 (Suppl. 3), 244–251. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, J.S.; Roy, D.; Ghazal, P.; Wagner, E.K. Dimethyl sulfoxide blocks herpes simplex virus-1 productive infection in vitro acting at different stages with positive cooperativity. Application of micro-array analysis. BMC Infec. Dis. 2002, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notman, R.; Noro, M.; O’Malley, B.; Anwar, J. Molecular basis for dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) action on lipid membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13982–13983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ménorval, M.A.; Mir, L.M.; Fernández, M.L.; Reigada, R. Effects of dimethyl sulfoxide in cholesterol-containing lipid membranes: a comparative study of experiments in silico and with cells. PLoS One 2010, 7, e41733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvao, J.; Davis, B.; Tilley, M.; Normando, E.; Duchen, M.R.; Cordeiro, M.F. Unexpected low-dose toxicity of the universal solvent DMSO. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenfreund, E.; Puerner, J.A. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol. Lett. 1985, 24, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, L.S.; Wang, H.; Luk, C.W.; Ooi, V.E. Anticancer and antiviral activities of Youngia japonica (L.) DC (Asteraceae, Compositae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 94, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewa, M.; Legge, G.J.F.; Weigold, H.; Holan, G.; Birch, C.J. The use of a scanning proton microprobe to observe anti-HIV drugs within cells. Life Sci. 1994, 54, 1607–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.Y.; Lin, L.T.; Huang, H.H.; Yang, C.M.; Lin, C.C. Yin Chen Hao Tang, a Chinese prescription, inhibits both herpes simplex virus type-1 and type-2 infections in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2008, 77, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gescher, K.; Kühn, J.; Hafezi, W.; Louis, A.; Derksen, A.; Deters, A.; Lorentzen, E.; Hensel, A. Inhibition of viral adsorption and penetration by an aqueous extract from Rhododendron ferrugineum L. as antiviral principle against herpes simplex virus type-1. Fitoterapia. 2011, 82, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konigheim, B.S. Prospección de productos naturales con potencial actividad antiviral obtenidos a partir de especies nativas de género Larrea. Doctoral thesis. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Córdoba, Argentina. 2012.

- Andrei, G.M.; Coto, C.E.; De Torres, R.A. Ensayos de citotoxicidad y actividad antiviral de extractos crudos y semipurificados de hojas verdes de Melia azedarach L. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 1985, 17, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vanden Berghe, D.A.; Vlietinck, A.J.; Van Hoof, L. Plant products as potential antiviral agents. Bull lnst. Pasteur. 1986, 84, 101–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rienzo, J.A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.W. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. 2017.

- Geran, R.I.; Greenberg, N.H.; McDonald, M.M.; Schumacher, A.M.; Abbot, B.J. Protocol for screening chemical agents and natural products against animal tumors and other biological systems. Cancer Chemother. Rept. 1972, 3, 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cariddi, L.N.; Escobar, F.M.; Sabini, M.C.; Torres, C.V.; Zygadlo, J.L.; Sabini, L.I. First approaches in the study of cytotoxic and mutagenic damage induced by cold aqueous extract of Baccharis articulata on normal cells. Mol. Med. Chem. 2010, 21, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- García Villalón, M.D. (Doctoral thesis). Inhibidores de la multiplicación del virus de la peste porcina africana (tesis doctoral). Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Madrid, España. 2002.

- Palomino, S.S.; Abad, M.J.; Bedoya, L.M.; Garcia, J.; Gonzales, E.; Chiriboga, X.; Bermejo, P.; Alcami, J. Screening of South American plants against human immunodeficiency vírus: preliminary fractionation of aqueous extract from Baccharis trinervis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 25, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.J.A.; Bessa, A.L.; Benito, P.B. Biologically active substances from the genus Baccharis L. (Compositae). Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2005, 30, 703–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanha, J.A.; Moellerke, P.; Bordignon, S.A.; Schenkel, E.P.; Roehe, P.M. . Antiviral activity of Brazilian plant extracts. Acta Farm. Bonaer. 2004, 23, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, C.G.T.; Campos, M.G.; Felix, D.M.; Santos, M.R.; de Carvalho, O.V.; Diaz, M.A.N.; de Almeida, M. R. Evaluation of the antiviral activities of Bacharis dracunculifolia and quercetin on Equid herpesvirus 1 in a murine model. Research in veterinary science 2018, 120, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintini Jaime, M.F.; Redko, F.; Muschietti, L.V.; et al. In vitro antiviral activity of plant extracts from Asteraceae medicinal plants. Virol J 2013, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, C.B.; Comunello, L.N.; Maciel, É.S.; Giubel, S.R.; Bruno, A.N.; Chiela, E.C.; Gosmann, G. The inhibitory effects of phenolic and terpenoid compounds from Baccharis trimera in Siha cells: differences in their activity and mechanism of action. Molecules 2013, 18, 11022–11032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, G.J.; Planchuelo, A.M.; Fuentes, E.; Ojeda, M. A numeric index to establish conservation priorities for medicinal plants in the Paravachasca Valley, Córdoba, Argentina. Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 15, 2458–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrighetti-Fröhner, C.R.; Sincero, T.C.M.; da Silva, A.C.; Savi, L.A.; Gaido, C.M.; Bettega, J.M.R.; Mancini, M.; de Almeida, M.T.R.; Barbosa, R.A.; Farias, M.R.; Barardi, C.R.M.; Simões, C.M.O. Antiviral evaluation of plants from Brazilian Atlantic Tropical Forest. Fitoterapia. 2005, 76, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, E. Antiviral agents: characteristic activity spectrum depending on the molecular target with which they interact. Adv. Virus Res. 1993, 42, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Barrio Alonso, G.; Álvarez Rodríguez, Á.L.; Valdés García, S.M.; Parra Fernández, F. Metodología de pesquisa preclínica de actividad anti-herpesvirus a partir de productos naturales. Rev. Cubana Farm. 2008, 42, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Loayza, I.; Abujder, D.; Aranda, R.; Jakupovic, J.; Collin, G.; Deslauriers, H.; Jean, F.I. Essential oils of Baccharis salicifolia, B. latifolia and B. dracunculifolia. Phytochemistry. 1995, 38, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Montenegro, G.; Hoffmann, J.J.; Timmermann, B.N. Diterpenoids from Baccharis linearis. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.G.; Oliveira, C.; Pinto, J.E.B.; Nascimento, V.E.; Santos, S.C.; Seraphin, J.C.; Ferri, P.H. Seasonal variability in the essential oils of wild and cultivated Baccharis trimera. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2007, 18, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzo, C.D.; Atti-Serafini, L.; Laguna, S.E.; Cassel, E.; Lorenzo, D.; Dellacassa, E. Essential oil variability in Baccharis uncinella DC and Baccharis dracunculifolia DC growing wild in southern Brazil, Bolivia and Uruguay. Flavour. Fragr. J. 2008, 23, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, A.G.; Bruentti, P.C.; Massuh, Y.; Ocaño, S.F.; Torres, L.E.; Ojeda, M.S. Variabilidad entre poblaciones silvestres de Baccharis crispa Spreng. de la Provincia de Córdoba, Argentina. Phyton. 2014, 83, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, X.; Abdala-Roberts, L.; Nell, C.S.; Vázquez-González, C.; Pratt, J.D.; Keefover-Ring, K.; Mooney, K.A. Sexual and genotypic variation in terpene quantitative and qualitative profiles in the dioecious shrub Baccharis salicifolia. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões-Pires, C.A.; Queiroz, E.F.; Henriques, A.T.; Hostettmann, K. Isolation and on-line identification of anti-oxidant compounds from three Baccharis species by HPLC-UV-MS/MS with post-column derivatisation. Phytochem. Anal. 2005, 16, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, P.; Gutkind, G.O.; Rondina, R.V.D.; Torres, R.A.D.; Coussio, J.D. Actividad antimicrobiana de Baccharis crispa Sprengel ("Carqueja", FA) y Baccharis notosergila Gris. Acta Farm. Bonaer. 1983, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ceñal, J.P.; Giordano, O.S.; Rossomando, P.C.; Tonn, C.E. Neoclerodane diterpenes from Baccharis crispa. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 490–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez, A.M.; Mallorquín, Z.E.; Montalbetti, Y.; Campuzano-Bublitz, M.A.; Hellión-Ibarrola, M.C.; Kennedy, M.L.; Ibarrola, D.A. Assessment of General effects and gastrointestinal prokinetic activity of Baccharis crispa in mice. J. App. Biol. Biotech. 2019, 7, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, C.; Pan, Y.; Gao, X.; Wu, X.; Bai, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Shi, S.; Luo, J.; Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, Y. Evaluation of antiviral activity of compounds isolated from Ranunculus sieboldii and Ranunculus sceleratus. Planta Med. 2005, 71, 1128–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, B.; Kartal, M.; Orhan, I. Cytotoxicity, antiviral and antimicrobial activities of alkaloids, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Qiao, H.; Lv, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Hou, Y.; Tan, R.; Li, E. Apigenin Inhibits Enterovirus-71 Infection by Disrupting Viral RNA Association with trans-Acting Factors. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakobyan, A.; Arabyan, E.; Kotsinyan, A.; Karalyan, Z.; Sahakyan, H.; Arakelov, V.; Nazaryan, K.; Ferreira, F.; Zakaryan, H. Inhibition of African swine fever virus infection by genkwanin. Antiviral Res. 2019, 167, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.; Massuh, Y.; Aguilar, J.J.; Ojeda, M.S.; Contigiani, M.S.; Núñez Montoya, S.C.; Konigheim, B.S. Cultivars of Tagetes minuta L. (Asteraceae) as a source of potential natural products with antiviral activity. J. Herb. Med 2020, 24, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, B.T.; Xavier, V.B.; Falcão, M.A.; Mondin, C.A.; dos Santos, M.A.; Cassel, E.; Astarita, L.V.; Santarém, E.R. Seasonal changes in phenolic compounds and in the biological activities of Baccharis dentata (Vell.) G.M. Barroso. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 51, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extracts/ positive control |

Population | CC50 (µg/mL)1 | SubTC (µg/mL)2 | CHIKV | HSV-I | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (%)3 | EC504 (µg/mL) |

SI5 | I (%) | EC50 (µg/mL) |

SI | ||||

| CHCl3 | VP | 326.2 ± 6.7d | 134.9 ± 5.6c | 45.7 ± 0.8 | - | - | 17.6 ± 0.6 | - | - |

| TC | 109.3 ± 4.6b | 52.0 ± 2.6a | 59.4 ± 0.6c | 44.2 ± 0.2 | 2.5 | 41.3 ± 0.6 | - | - | |

| SG | 169.1 ± 5.7c | 105.6 ± 10.1b | 67.0 ± 1.2b | 78.8 ± 0.5 | 2.1 | 48.3± 0.1 | - | - | |

| PP | 94.8 ± 1.6a | 45.7 ± 0.4a | 81.6 ± 0.9a | 28.2 ± 0.1 | 3.4 | 55.2 ± 0.4 | 41.4 ± 0.1 | 2.3 | |

| EtOH | VP | 92.9 ± 3.5ª | 20.2 ± 1.1a | 35.9 ± 0.6 | - | - | 32.5 ± 0.6 | - | - |

| TC | 413.6 ± 9,5c | 219.8 ± 5.4c | 43.0 ± 0.9 | - | - | 57.6 ± 0.4b | 190.8 ± 0.3 | 2.2 | |

| SG | 159.2. ± 1.5b | 103.6 ± 2.8b | 63.5 ± 0.9b | 81.6 ± 0.4 | 2 | 61.6 ± 0.5b | 84.1 ± 0.6 | 1.9 | |

| PP | 571.9 ± 0.3d | 326.8 ± 9.8d | 79.0 ± 0.8a | 188.7 ± 0.1 | 3 | 78.9 ± 0.2a | 207.1 ± 0.1 | 2.8 | |

| Aqu | VP | 700.4 ± 17.3d | 482.0 ± 11.4b | 27.8 ± 0.1 | - | - | 19.4 ± 0.2 | - | - |

| TC | 611.9 ± 9.1c | 507.0 ± 0.7c | 35.8 ± 0.2 | - | - | 30.2 ± 0.2 | - | - | |

| SG | 422.3 ± 9.6a | 342.8 ± 9.3a | 57.9 ± 1.1b | 296.0 ± 0.2 | 1.4 | 38.9 ± 0.1 | - | - | |

| PP | 573.4 ± 2.3b | 491.9 ± 0.7b | 74.0 ± 0.6a | 332.4 ± 0.5 | 1.7 | 51.2 ± 0.7 | 480.4 ± 0.1 | 1.2 | |

| Acyclovir | - | >200 | - | - | - | - | 100 | >1000 | >20.000 |

| Compound groups | Extracts | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHCl3 | EtOH | Aqu | ||||||||||

| VP | TC | SG | PP | VP | TC | SG | PP | VP | TC | SG | PP | |

| Tanins | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | +++ | +++ |

| Antocianins | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cardiac glycoside | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Carbohydrate | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | ++ | - | - | - | ++ |

| Saponins | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Flavonoids | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + | + | ++ |

| Anthraquinone | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Phytosterols | - | + | + | ++ | - | - | - | ++ | - | - | - | - |

| Alkaloids | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).