1. Introduction

The author has studied multiple natural languages and artificial languages such as C for many years as a language hobby. In the process, he has developed a deep interest in language itself and the function of the brain that manipulates language [

1]. This study aims to clarify the geometric properties of the translation process, which are difficult to explain using conventional linguistic theory.

In this study, we regard language space as a mathematical coordinate space, and treat translation between different languages as a coordinate transformation, assuming the existence of an invariant called the meaning of language. From this perspective, different languages correspond to relative coordinate systems, and translation is expressed as a transformation (mapping) between them, so we call this approach "geometric language space."

Even though English is linguistically close to German and French, an English speaker with no knowledge of German or French would not be able to understand the meaning of a German or French sentence.

However, through the process of translation, it becomes possible to understand. Why is the process of translation possible?

What does the translation process do mathematically? The introduction of generative AI into language analysis provided a clue to this question [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

If we consider a sentence to be a point in language space, or a vector set or vector sum of "words: the smallest element vectors", it becomes possible to introduce geometry into language. If we consider a sentence to be a substance, then words correspond to the atoms or molecules that make up the sentence. Language space is ultra-multidimensional.

Thinking about it this way, a sentence vector becomes a set of point vectors that give a sequence (trajectory) of point vectors in a language space based on words.

Words in different languages can be matched up using the meaning of the word as a medium. Specifically, between English and French, there is a correspondence at the word level, for example, between "apple" in English and "pomme" in French. As a result, a close geometric relationship is created between the two different language spaces.

"A delicious apple" in English becomes "pomme délicieuse" in French, and "I eat a delicious apple" in English becomes "Je mange une pomme délicieuse" in French.

If you wanted to say "I eat a delicious apple at a restaurant" in English, you'd say "Je mange une pomme délicieuse au restaurant" in French.

If you wanted to say "I eat a delicious apple recommended by my friend at a restaurant" in English, you'd say "Je mange une pomme délicieuse recommandée par mon ami au restaurant" in French.

"I eat a delicious apple recommended by my friend at a restaurant, but I am disappointed" in English would be "Je mange une pomme délicieuse recommandée par mon ami au restaurant, mais je suis déçu".

At first glance, this unexpected correlation between languages seems puzzling. In the concrete space, the differences between different languages are large, but in the abstract space abstracted through meaning, the differences are small. This is to be expected as long as we are dealing with languages between humans on Earth.

In the above discussion, we have assumed that words are the basis, but other elements can also be used as the basis. For example, in the case of linguistic communication between humans and dolphins or whales, a communication medium and basis from a physically different perspective would be chosen.

In this direction, linguistics is likely to make great strides in the future.

2. Linguistic Geometry Space

Intuitively, the following equations seem to make sense:

Why? The abstractions of America and Japan are nations, and the abstractions of Washington and Tokyo are capitals, so at the abstract level, the following equations hold:

The same goes for the following examples:

Such algebraic properties suggest that linguistic spaces have invariants and linearity, like the distance between two points in mathematical Euclidean space.

The simplest way to vectorize words is to arrange the words in a row and assign an N-dimensional one-hot vector from the beginning of the row:

where N is the number of words.

Words in a language have various relationships with each other. For example, they may have similar meanings, or they may be often used side by side, such as "cute baby." Although one-hot vectors can convert words into numeric vectors, they do not reflect the relationships between words at all. Therefore, this method is useless as it is.

To convert words into useful numeric vectors, the distributed representation of words described in references [

2,

3,

4] is useful. An actual calculation method is word2vec. An explanation of the CBOW model, which is one of the word2vec models, is given in

Appendix A. Below, we explain how to estimate the middle word of a sequence of three consecutive words from the two words to the left and right of it, using the idea of CBOW.

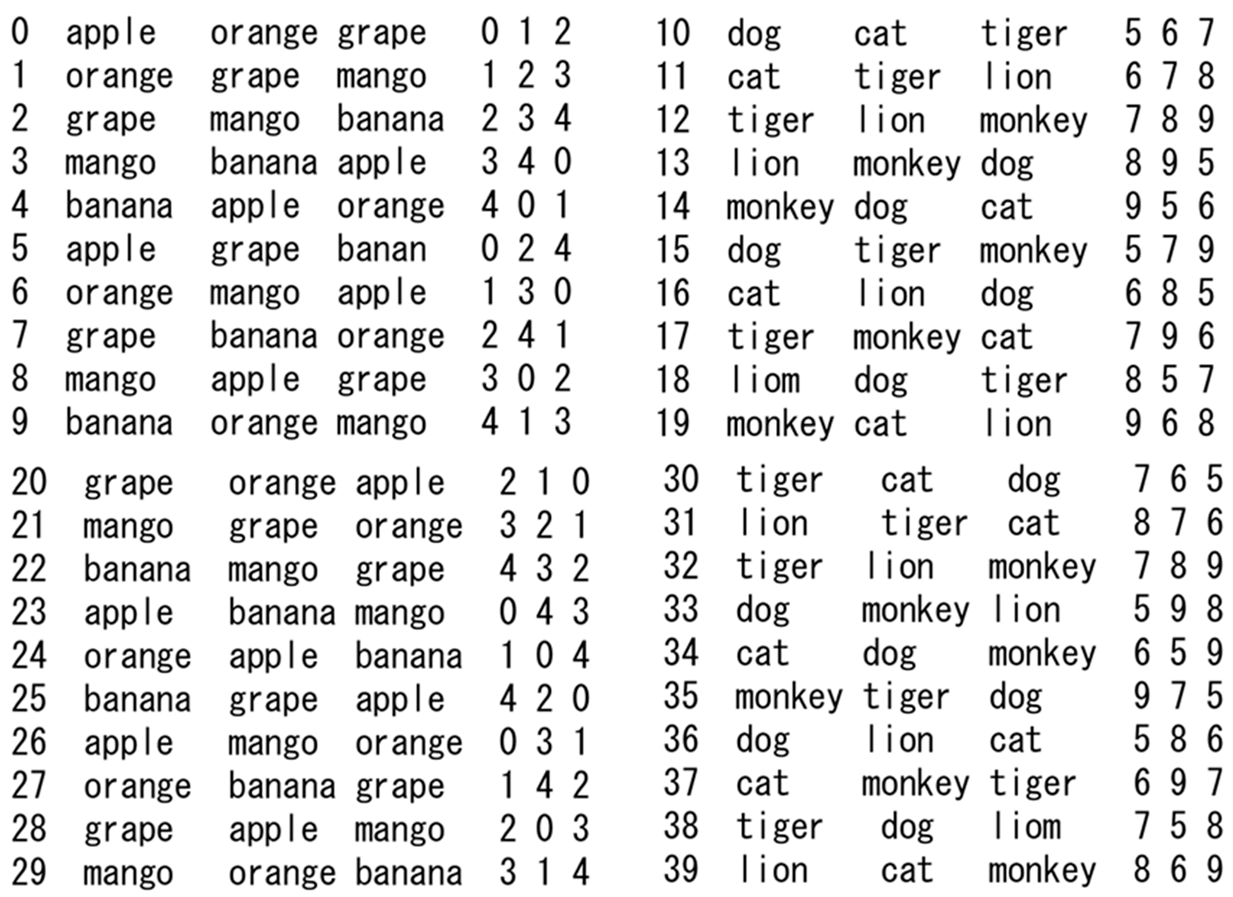

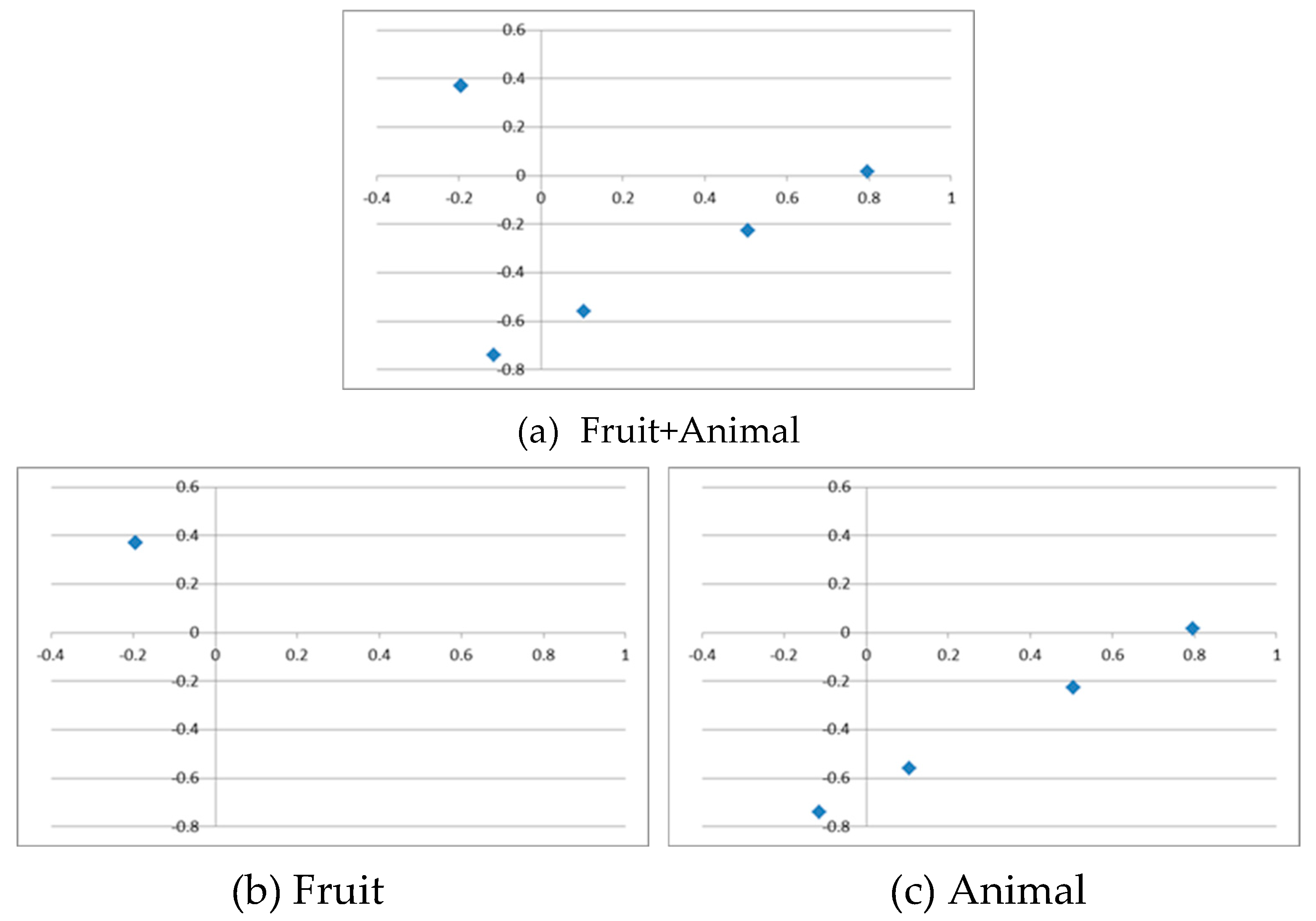

Each of the ten 10-dimensional one-hot vectors for the ten words (five fruit words and five animal words) shown in

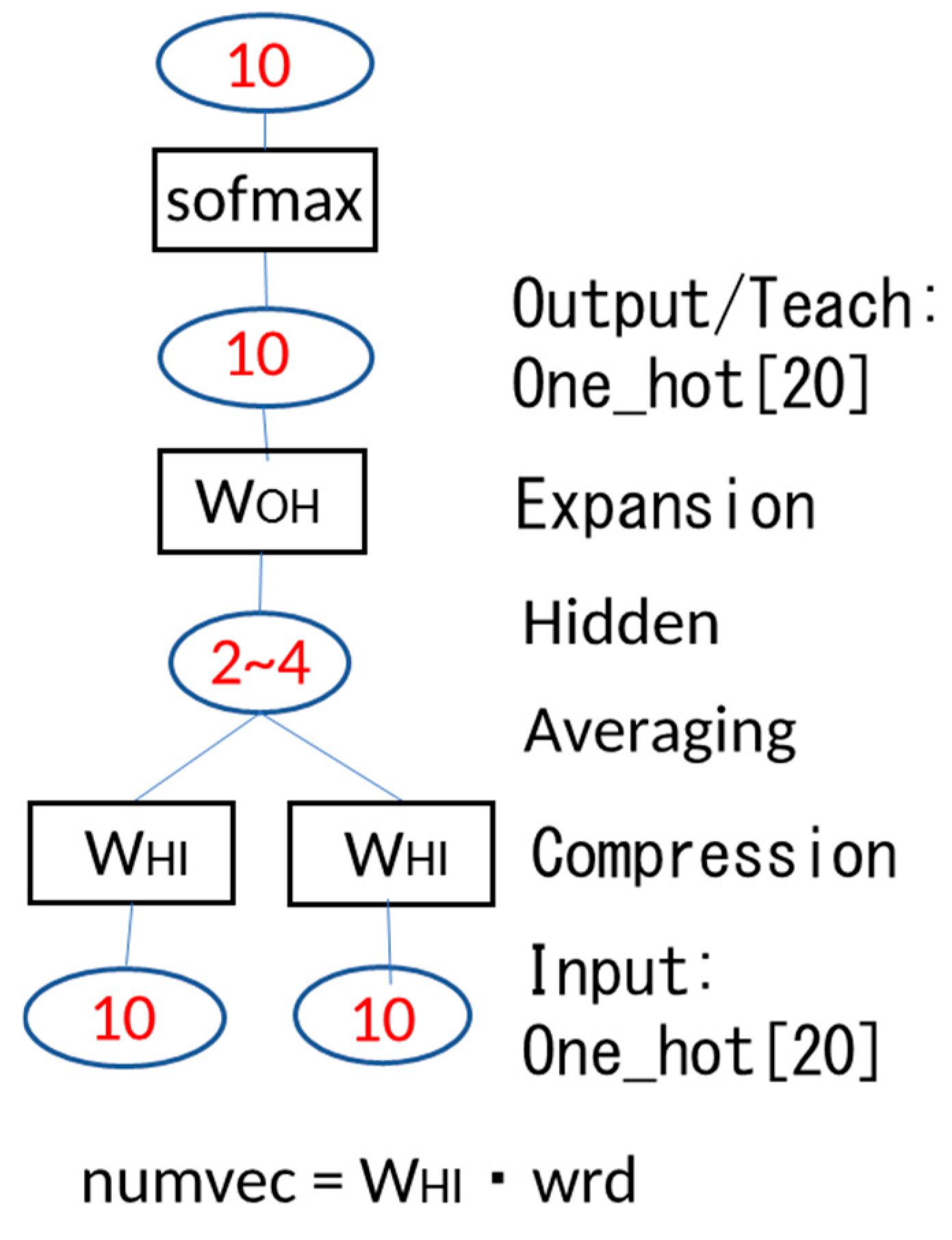

Figure 1 is compressed into ten 2- to 4-dimensional vectors using the neural network (NN) shown in

Figure 3 by solving the fill-in-the-blank problem in

Figure 2. In this way, the classification problem (feature extraction: fruit or animal) hidden in the fill-in-the-blank problem is solved.

In the NN shown in

Figure 3, two 10-dimensional one-hot vectors are given to the input layer, each of which is multiplied by the weight matrix

WHI, and an offset

OH is added, and then the average of the two is taken and becomes the input to the middle layer. The dimensions are compressed in the middle layer. Assuming a linear relationship between input and output, the input to the middle layer becomes the production of the middle layer as is. The output of the middle layer is multiplied by the weight matrix

WOH and an offset

OO is added, which becomes the input to the output layer and the production of the output layer as is. The dimensions are expanded in the output layer. The training data is given a single 10-dimensional one-hot vector used as the input data. Finally, it is converted to a probability by sofmax.

The structure of the neural network, i.e., the number of layers NLYR, the number of input cells IU, the number of hidden layer cells HU, and the number of output cells OU, are given in the SYSTEM.dat file. The parameters required for calculations are given in the PARAM.dat file. The number of learning iterations is specified by times.

Table 1.

SYSTEM.dat file.

Table 1.

SYSTEM.dat file.

| NLYR 3 |

| IU 20 |

| HU 2 |

| OU 10 |

| NT 40 |

Table 2.

PARAM.dat file.

| u0 0.5 |

| intwgt 0.3 |

| intoff 0.2 |

| alpha 0.025 |

| beta 0.025 |

| moment 0.025 |

| dmoment 0.002 |

| erlimit 0.001 |

| times 10000 |

We consider 40 pairs of three words in total, including 10 pairs taken only from fruits with no duplicates, 10 pairs taken only from animals in the same way, and 20 pairs created by swapping the two words on either side, for a total of 40 pairs (NT = 40).

Table 3.

INPUT-TEACH.dat file.

Table 3.

INPUT-TEACH.dat file.

When we calculate the fill-in-the-blank problem, we get the following interesting result in the dimensionally reduced hidden layer. The output cell of each cell is

Therefore, this problem is linear. This gives linear algebraic properties to the number vector. The number vector

numvec here is calculated as follows:

where,

WHI and

OH are the weights and offset between the hidden layer and the input layer, and the one-hot vectors of each word are given as input, respectively.

By solving the fill-in-the-blank problem, number vectors with a distributed word representation are obtained. The

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

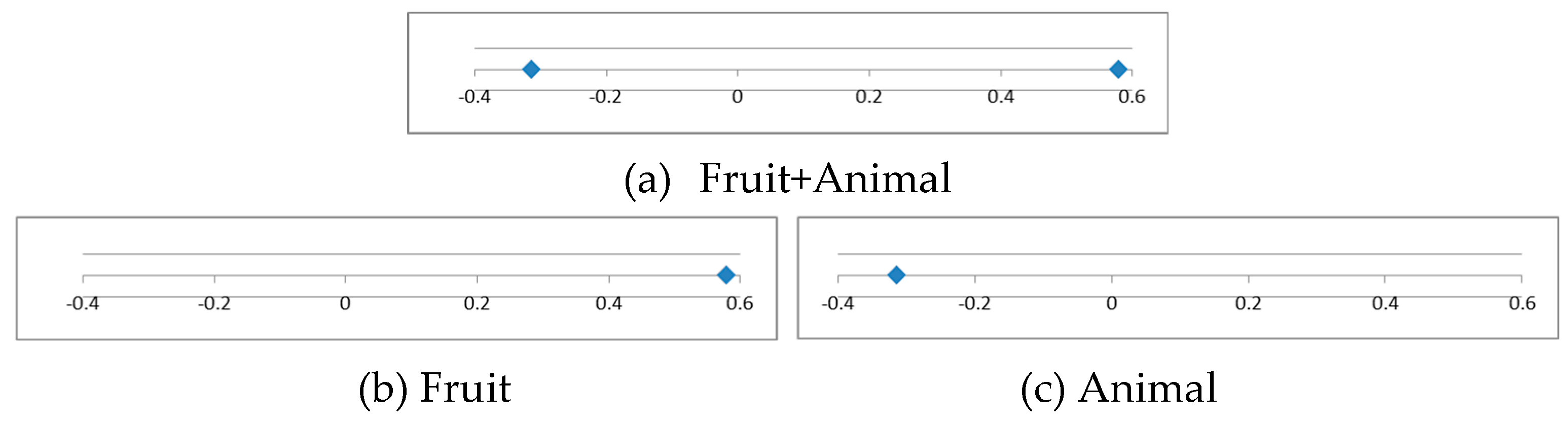

Figure 7 shows the learning results using the above input data and training data for the case where the number of training data pieces is NT = 40. This data has a hidden meaning of being classified into two categories, fruits and animals, and compact number vector representation is obtained from the one-hot vectors with this meaning reflected.

Figure 4 shows the number vector

numvec when there is one hidden cell (

HU = 1). We can see that the 40 data are classified into two categories, fruits and animals (two points on the line), according to the hidden meaning. However, since the fruit words and animal words are not separated, this representation cannot be used for translation or other purposes.

Figure 5 shows the number vector

numvec when there are two hidden cells (HU = 2). We can see that the 40 data points are classified into two categories: fruits and animals (two point groups on a plane). However, each fruit word is not separated, and the five animal words are reduced to four numeric vectors, so this representation is also unusable for purposes such as translation.

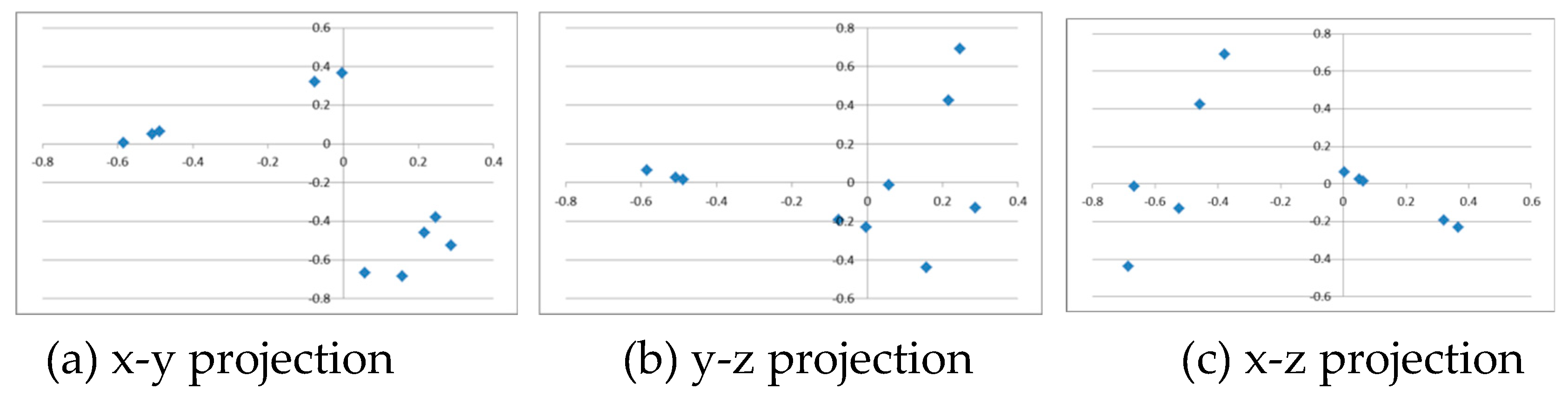

Figure 5 shows the number vector

numvec when there are three hidden cells (

HU = 3). It shows that the 40 data points are classified into two categories: fruits and animals (two point clouds in three-dimensional space). Furthermore, the components of the two point clouds for fruits and animals are completely separated. This representation seems usable for purposes such as translation.

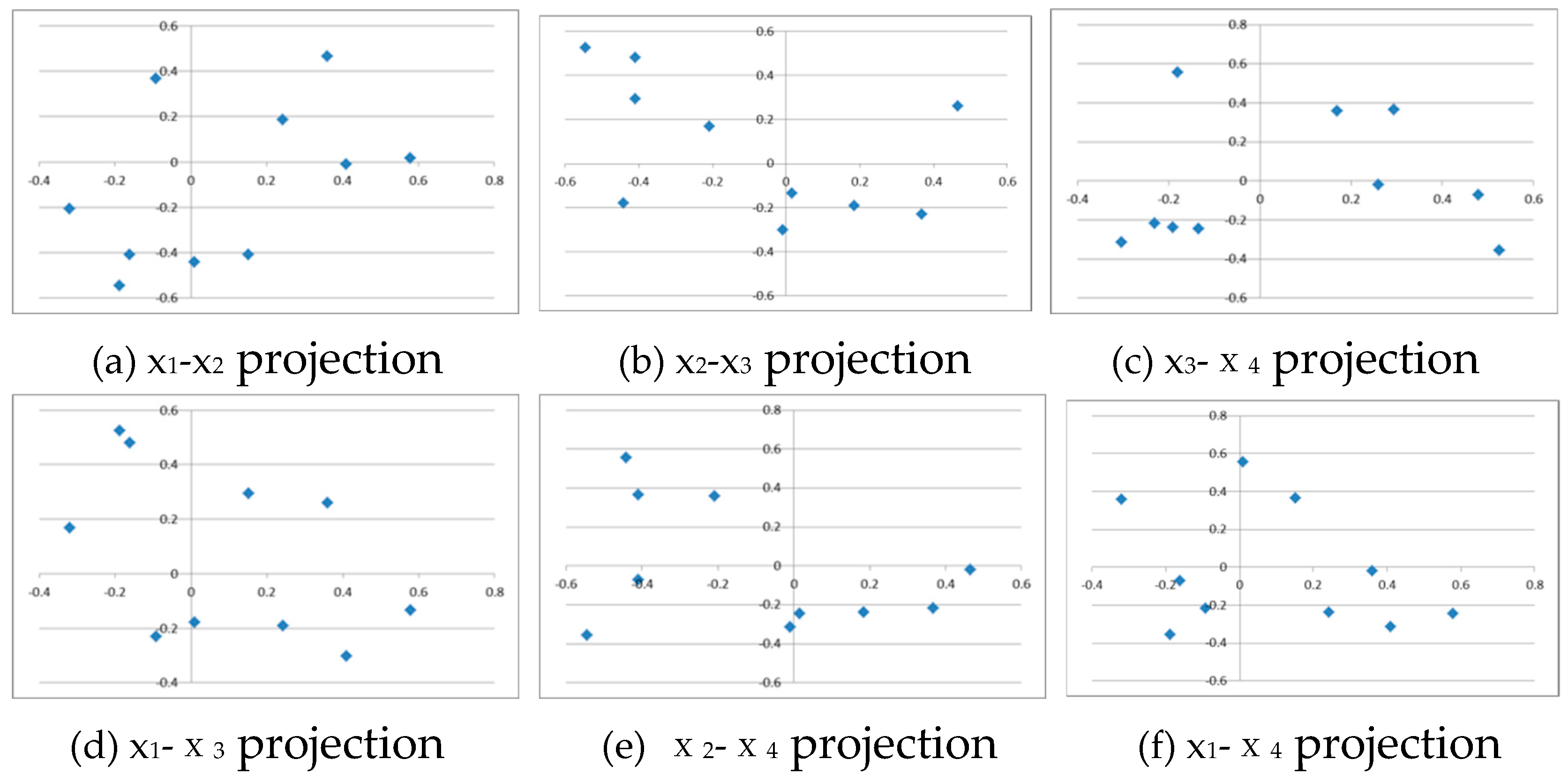

Figure 6 shows the number vector

numvec when there are four hidden cells (HU = 4). It can be seen that the 40 data points are classified into two categories: fruits and animals (two point clouds in four-dimensional space). Furthermore, the components of the two point clouds for fruits and animals are clearly separated. This expression seems to be useful for purposes such as translation.

The number vector

numvec for HU = 3 is shown in

Table 4. From this result, for example, the inner product of apples and oranges (apple, orange), the inner product of dogs and cats (dog, cat), and the inner product of apples and dogs (apple, dog) are

The correlation between fruits and animals is smaller than the correlation between fruits and fruits and the correlation between animals and animals.

If we introduce Euclidean distance as the distance between words, for example, the distance

d(

apple, orange) between apples and oranges and the distance

d(

dog, cat) between dogs and cats are calculated as

In addition, the average position of fruits (

xf, yf, zf) and the average position of animals (

xa, ya, za) are calculated as

The distances between the average positions

d(

fruit, animal) is calculated as

Table 4.

Number vector numvec for HU = 3.

Table 4.

Number vector numvec for HU = 3.

| k: |

word |

x |

y |

z |

| 0 |

apple |

-0.584172 |

0.00403 |

0.065173 |

| 1 |

orange |

-0.002623 |

0.366662 |

-0.229709 |

| 2 |

grape |

-0.508273 |

0.051358 |

0.026687 |

| 3 |

mango |

-0.075167 |

0.321426 |

-0.192925 |

| 4 |

banana |

-0.487712 |

0.064179 |

0.016262 |

| 5 |

dog |

0.287074 |

-0.52356 |

-0.128992 |

| 6 |

cat |

0.057498 |

-0.666714 |

-0.012583 |

| 7 |

tiger |

0.157732 |

-0.684748 |

-0.439977 |

| 8 |

lion |

0.215578 |

-0.45749 |

0.424644 |

| 9 |

monkey |

0.245844 |

-0.37816 |

0.691991 |

Although it cannot be confirmed by simple learning with a small amount of data as described above, the number vectors based on distributed word representations by word2vec can realize very interesting algebraic properties as described below.

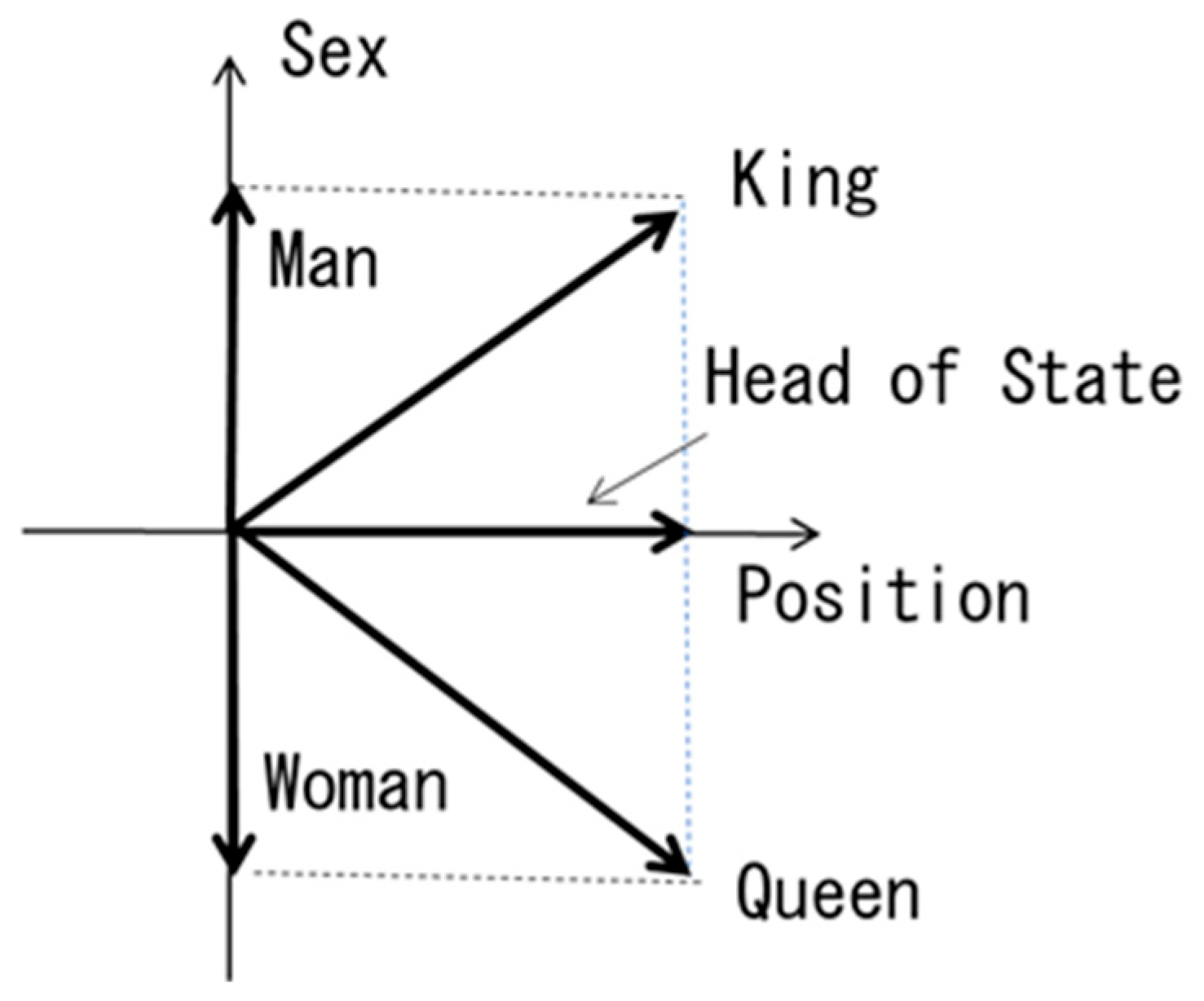

Figure 8 shows the algebraic properties of such number vectors:

Figure 8 illustrates the reason. This is probably because in learning methods like word2vec, the implicit relationships contained in the input data:

are also learned during the explicit learning process of fill-in-the-blank questions, and these relationships are accumulated in the weights between the input layer and the hidden layers.

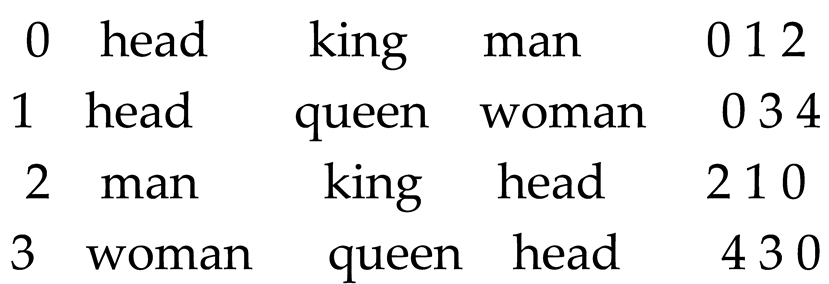

Let's consider this using the following data. For five words, Head (Head of State), King, Man, Queen, and Woman, we use the following three types of INPUT-TEACH.dat files:

Table 5.

INPUT-TEACH.dat file (OU=5, HU=2, IU=10, NT=4).

Table 5.

INPUT-TEACH.dat file (OU=5, HU=2, IU=10, NT=4).

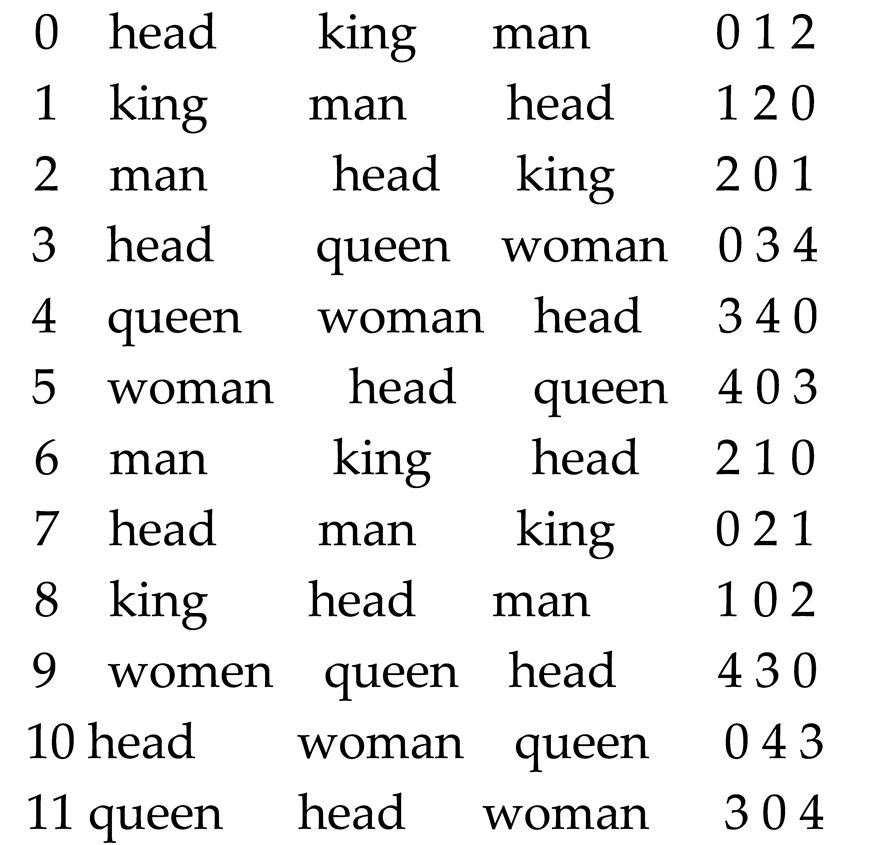

Table 6.

INPUT-TEACH.dat file (OU=5, HU=2, IU=10, NT=12).

Table 6.

INPUT-TEACH.dat file (OU=5, HU=2, IU=10, NT=12).

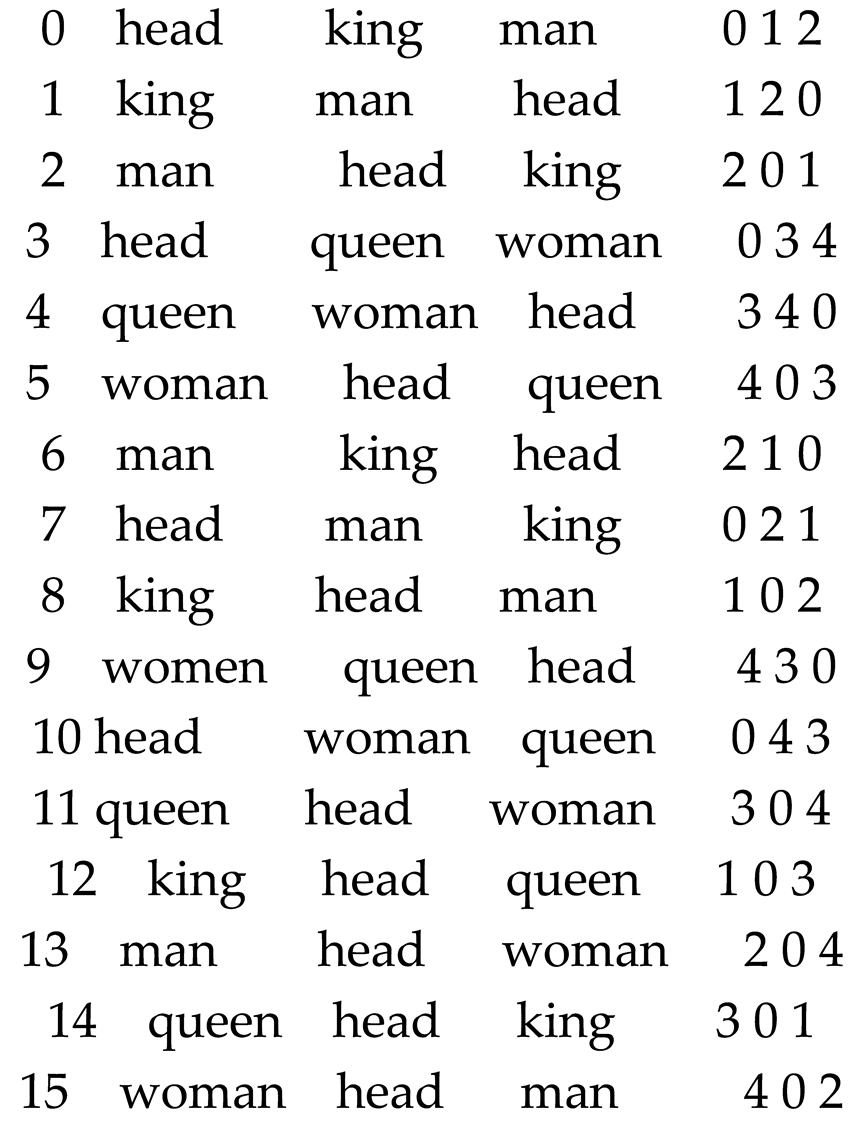

Table 7.

INPUT-TEACH.dat file (OU=5, HU=2, IU=10, NT=16).

Table 7.

INPUT-TEACH.dat file (OU=5, HU=2, IU=10, NT=16).

The data includes information about the heads of state, including the King and Queen, and the genders of the King and Queen, Man and Woman. Therefore, the interesting relationships between titles (King, Queen) and job titles (Head of state) and gender (Man, Woman) mentioned above can be derived.

For NT = 4, NT = 12, and NT = 16, the distributed representation of the number vectors by the NN for the fill-in-the-blank problem in

Figure 3 is as follows:

Table 8.

Number vector (NT = 4).

Table 8.

Number vector (NT = 4).

| |

Head |

King |

Man |

Queen |

Woman |

| x |

-0.01387 |

0.185897 |

0.635359 |

0.33299 |

-0.65818 |

| y |

0.049428 |

-0.1526 |

0.785826 |

0.130928 |

-0.69117 |

Table 9.

Number vector (NT = 12).

Table 9.

Number vector (NT = 12).

| |

Head |

King |

Man |

Queen |

Woman |

| x |

-0.5415 |

0.767788 |

-0.08519 |

0.327094 |

-0.1742 |

| y |

-0.5789 |

-0.27271 |

0.482651 |

0.117548 |

0.561467 |

Table 10.

Number vector (NT = 12).

Table 10.

Number vector (NT = 12).

| |

Head |

King |

Man |

Queen |

Woman |

| x |

-0.54611 |

0.703868 |

-0.06764 |

0.307364 |

-0.14322 |

| y |

-0.74313 |

-0.06512 |

0.469316 |

0.209544 |

0.521668 |

From these vectors, we perform the algebraic operation King - Man + Woman.

Table 11.

Algebraic operations King - Man+Woman.

Table 11.

Algebraic operations King - Man+Woman.

| |

NT = 4 |

NT = 12 |

NT = 16 |

| x |

-1.10764 |

0.678785 |

0.628294 |

| y |

-1.6296 |

-0.19389 |

-0.01277 |

When calculating the correlation coefficient

ρ:

between King - Man + Woman and each of the words Head, King, Man, Queen, and Woman, it is seen that in the cases of NT = 12 and NT = 16, where the relationships between each word are sufficiently embedded, the correlation with Queen is large, except for King. In NT = 16, the correlation coefficients with Queen, Man, and Woman are higher than in NT = 12, and the correlation coefficients with King and Head are lower.

Table 12.

Correlation coefficients between King - Man + Woman and Head, King, Man, Queen, and Woman.

Table 12.

Correlation coefficients between King - Man + Woman and Head, King, Man, Queen, and Woman.

| |

Head |

King |

Man |

Queen |

Woman |

| NT = 4 |

-0.64441 |

0.090258 |

-0.99656 |

-0.82579 |

0.986585 |

| NT = 12 |

-0.45679 |

0.997775 |

-0.43692 |

0.812236 |

-0.54657 |

| NT = 16 |

-0.57570 |

0.997461 |

-0.16275 |

0.814677 |

-0.28429 |

Similarly, if we perform the algebraic operation Queen - Woman + Man from these vectors, the following results are obtained:

Table 13.

Algebraic operations Queen - Woman + Man.

Table 13.

Algebraic operations Queen - Woman + Man.

| |

NT = 4 |

NT = 12 |

NT = 16 |

| x |

1.626527 |

0.416097 |

0.382938 |

| y |

1.607926 |

0.038732 |

0.157192 |

Calculating the correlation coefficient ρ between Queen - Woman + Man and each word Head, King, Man, Queen, and Woman, we can see that in the cases of NT = 12 and NT = 16, where the relationships between each word are sufficiently embedded, the correlation with King is large, except for Queen. In NT = 16, the correlation coefficient with Queen, Man, and Woman is higher than in NT = 12, and the correlation coefficient between King and Head is lower.

Table 14.

Correlation coefficients between Queen - Woman + Man and Head, King, Man, Queen, and Woman.

Table 14.

Correlation coefficients between Queen - Woman + Man and Head, King, Man, Queen, and Woman.

| |

Head |

King |

Man |

Queen |

Woman |

| NT = 4 |

0.484746 |

0.10361 |

0.99382 |

0.919092 |

-0.99954 |

| NT = 12 |

-0.74787 |

0.907247 |

-0.0818 |

0.96837 |

-0.20652 |

| NT = 16 |

-0.85381 |

0.886176 |

0.243888 |

0.978269 |

0.121283 |

The mathematics of translating from English to French will be explained using a simple example:

Roughly speaking, when a human translates, they follow the following steps: first, they look up the dictionary and translate word by word, then they rearrange the word order. This can be expressed mathematically as follows:

When we consider this together with the numerical vector representation of words by word2vec mentioned above, we can replace translation with computation. This is why we think of translation as coordinate transformation.

Let a sentence SA1 in the concrete space of a language A be mapped to a point T A SA1 in the semantic space by a transformation T A from the concrete space A to the semantic space.

It seems that by introducing an abstract space, we can uniquely define distance. Thinking in this way, we can introduce scalar distance that is independent of the coordinate system into linguistic space, which becomes a traditional geometric space:

Namely,

The distance between sentence

SA1 and sentence

SA2 in concrete space A =

.

To turn mathematical linguistic space into a physical space, we will need a mathematical expression of the state of the brain.