Figure 1.

ERCP remains the first-line method for accessing the bile duct. [

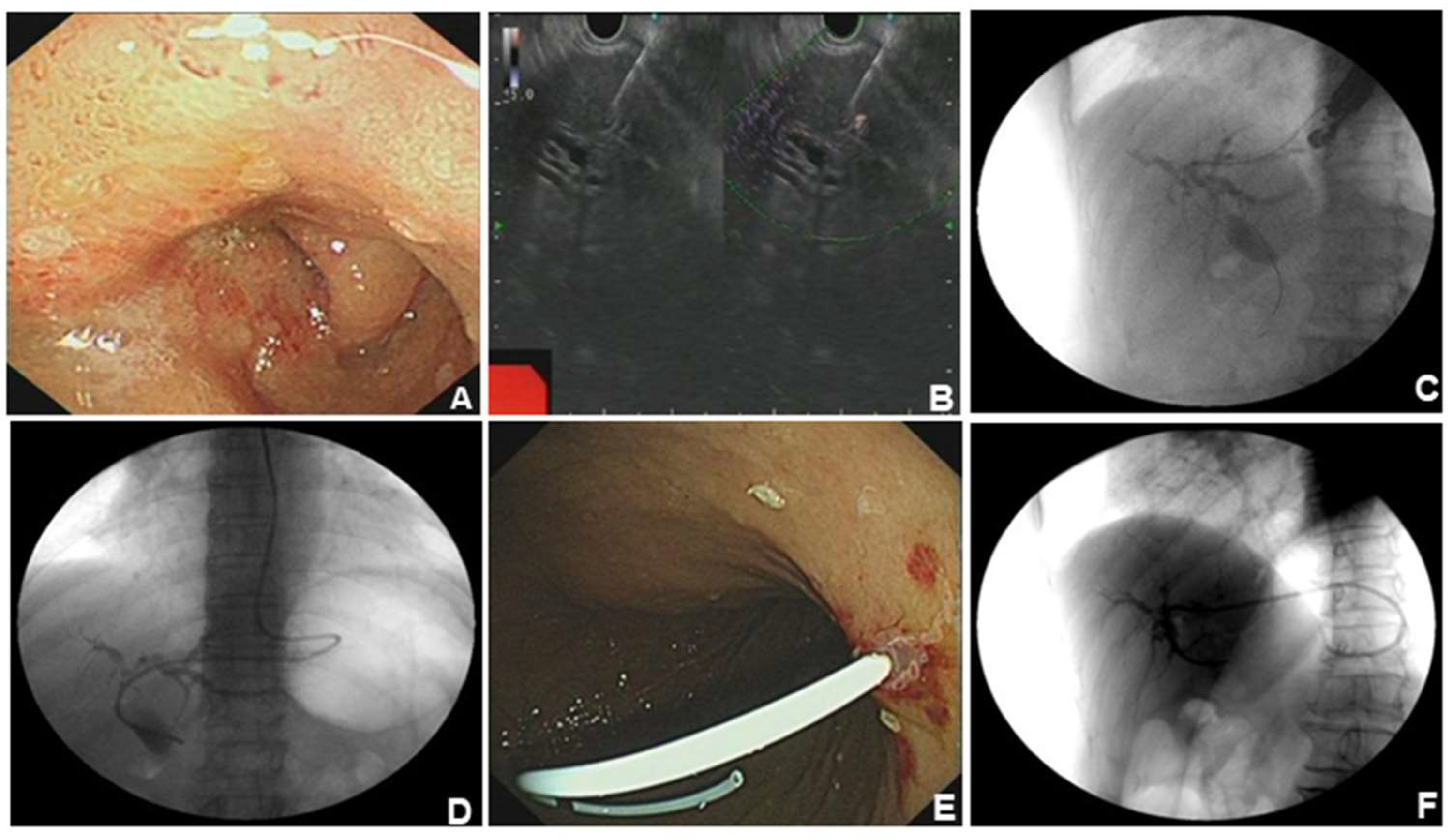

1] However, ERCP fails in 5%–10% of cases due to inaccessible papilla or inability to cannulate the papilla. [

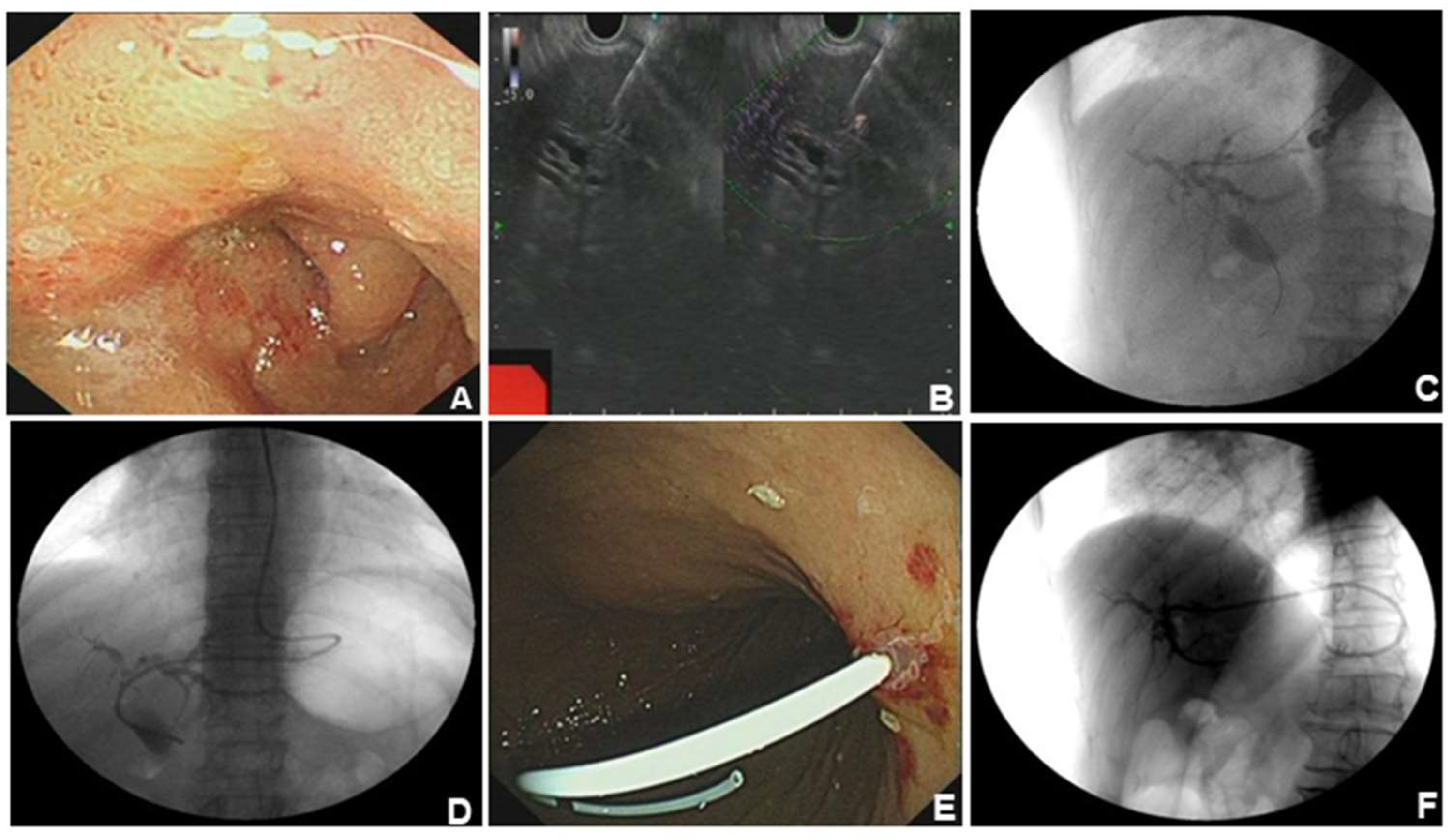

2] EUS-BD (including EUS-HGS and EUS-CDS) has appeared as a safe and efficacious alternative to PTCD or surgery when ERCP fails. A 76-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with intermittent pain in the upper abdomen for more than 2 months, with scleral icterus for 1 week. Previous imaging and pathology suggested adenocarcinoma in the head of the pancreas, accompanied by dilatation of the common bile duct. The patient failed ERCP and received EUS-BD for relieving jaundice, and the whole operation was successful. (A). The patient had obstruction in the descending part of duodenal bulb and duodenal papilla was inaccessible for ERCP. (B). Ultrasonographic endoscopic puncture of the intrahepatic S2 segmental bile duct puncture. (C). Puncture had succeeded and contrast agent was injected to show the intrahepatic bile ducts. (D). Nasal bile duct placement for drainage. (E). Snipped nasal bile duct for stent drainage. (F). Stent position under X-ray.

Figure 1.

ERCP remains the first-line method for accessing the bile duct. [

1] However, ERCP fails in 5%–10% of cases due to inaccessible papilla or inability to cannulate the papilla. [

2] EUS-BD (including EUS-HGS and EUS-CDS) has appeared as a safe and efficacious alternative to PTCD or surgery when ERCP fails. A 76-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with intermittent pain in the upper abdomen for more than 2 months, with scleral icterus for 1 week. Previous imaging and pathology suggested adenocarcinoma in the head of the pancreas, accompanied by dilatation of the common bile duct. The patient failed ERCP and received EUS-BD for relieving jaundice, and the whole operation was successful. (A). The patient had obstruction in the descending part of duodenal bulb and duodenal papilla was inaccessible for ERCP. (B). Ultrasonographic endoscopic puncture of the intrahepatic S2 segmental bile duct puncture. (C). Puncture had succeeded and contrast agent was injected to show the intrahepatic bile ducts. (D). Nasal bile duct placement for drainage. (E). Snipped nasal bile duct for stent drainage. (F). Stent position under X-ray.

Figure 2.

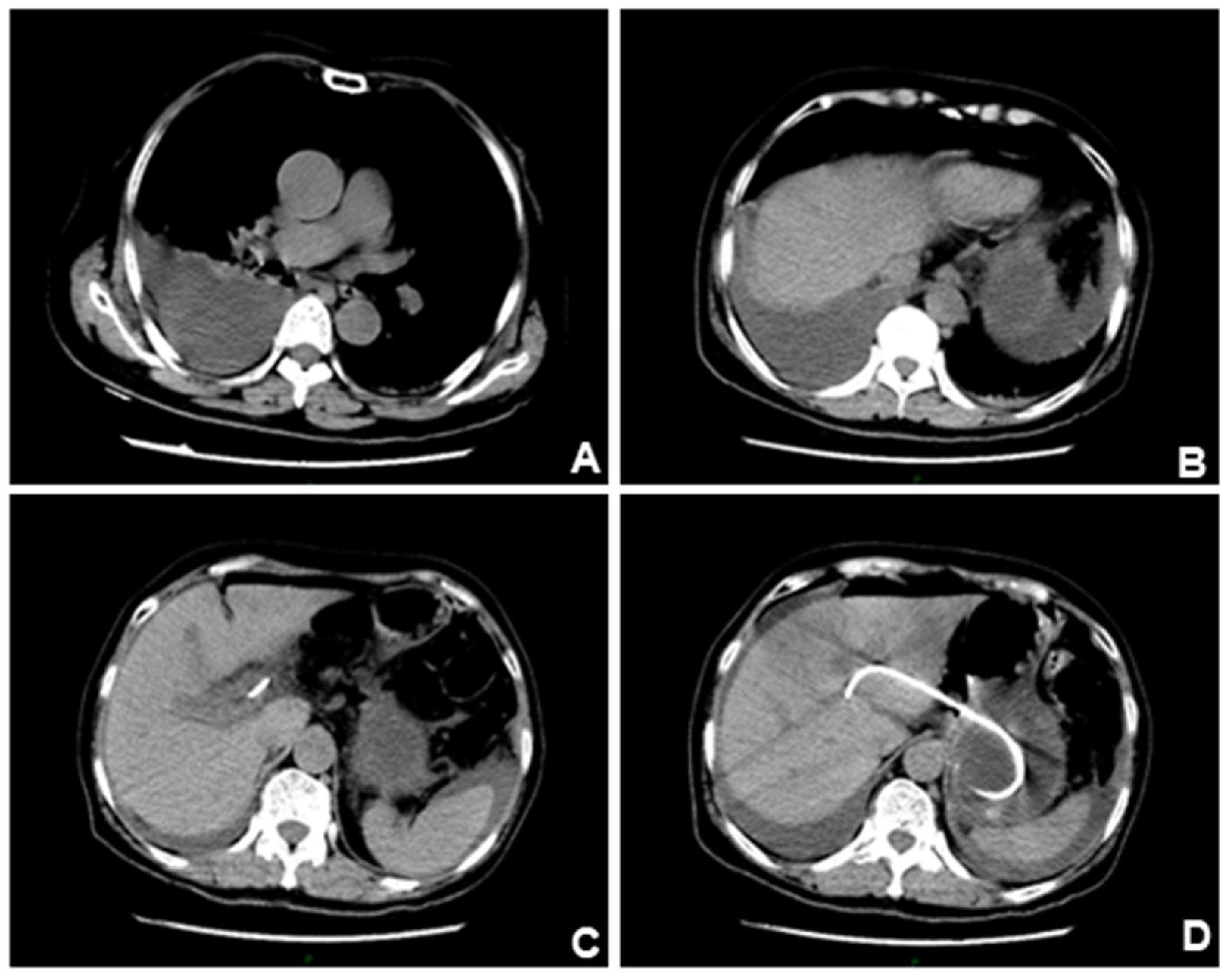

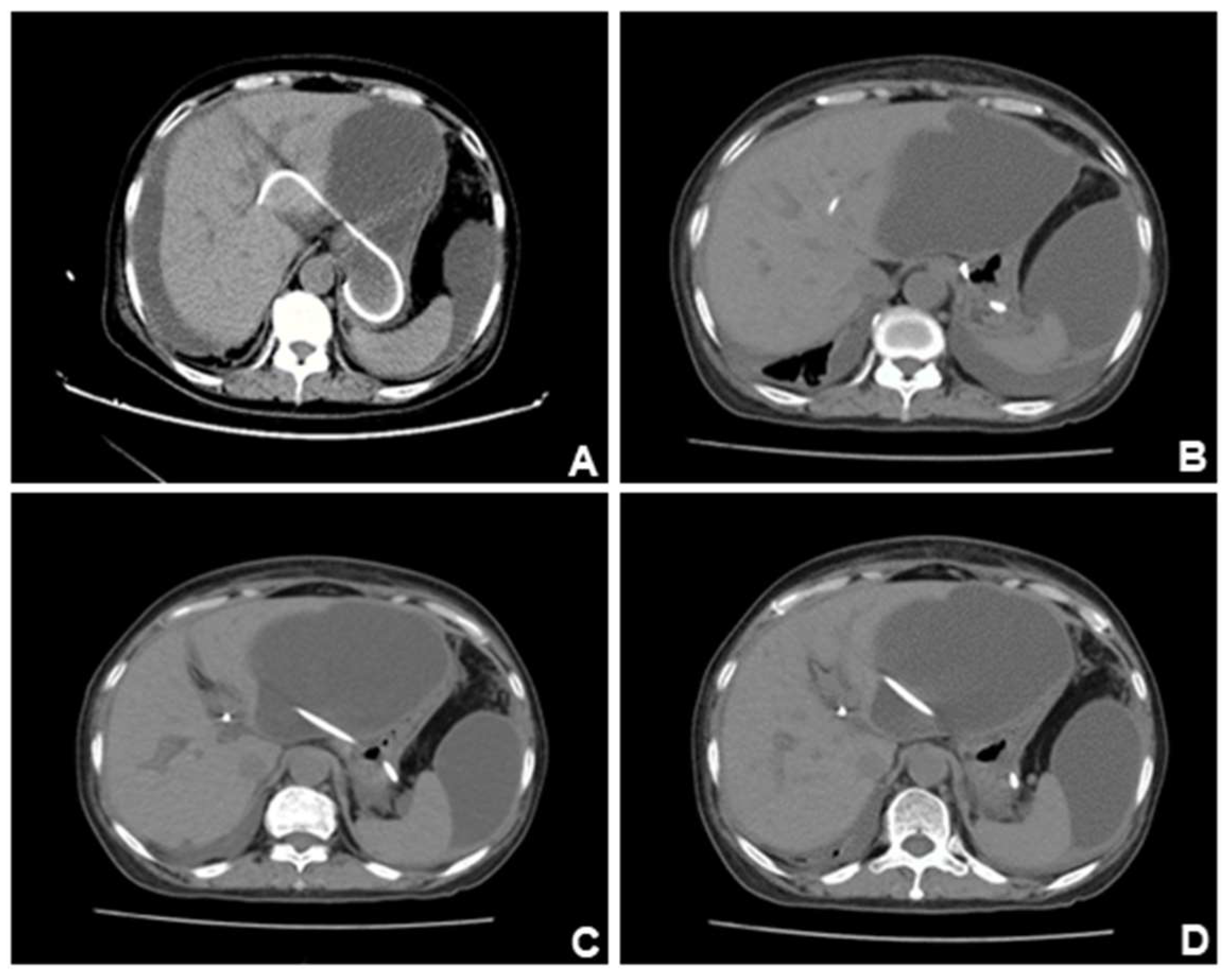

The patient reported abdominal pain and chest tightness in the next afternoon with difficulty in urinating and emergency CT of the chest was performed(A-B). CT results suggestive of right pleural effusion and right lower lobe lung atelectasis. (C-D). The stent was shown to be well-positioned under CT. We suspected that the patient's pleural effusion may have been caused by accidental injury to the diaphragm during the puncture procedure. After chest drainage was performed, the bilateral lung fields returned clear and showed no substantial lesions.

Figure 2.

The patient reported abdominal pain and chest tightness in the next afternoon with difficulty in urinating and emergency CT of the chest was performed(A-B). CT results suggestive of right pleural effusion and right lower lobe lung atelectasis. (C-D). The stent was shown to be well-positioned under CT. We suspected that the patient's pleural effusion may have been caused by accidental injury to the diaphragm during the puncture procedure. After chest drainage was performed, the bilateral lung fields returned clear and showed no substantial lesions.

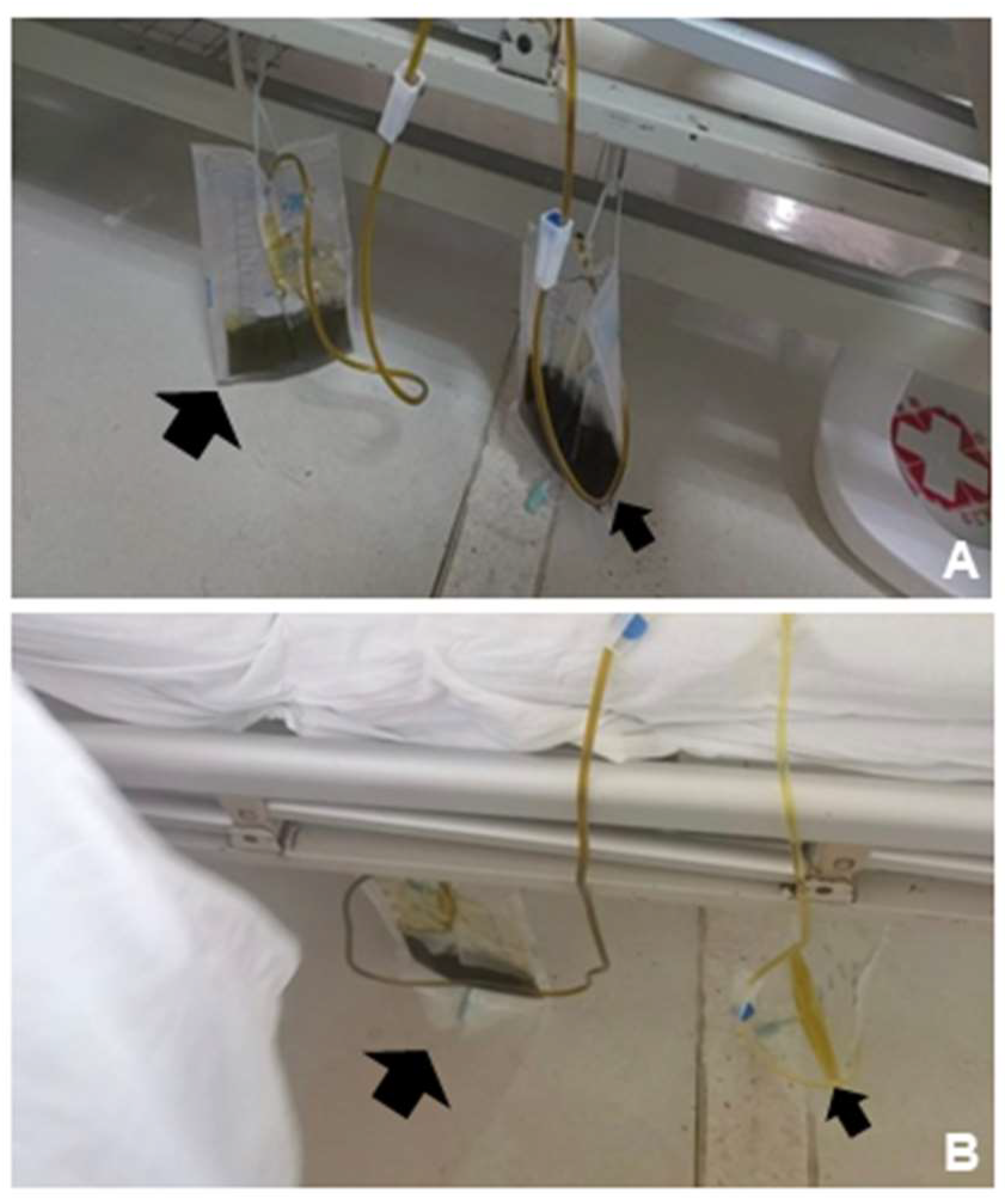

Figure 3.

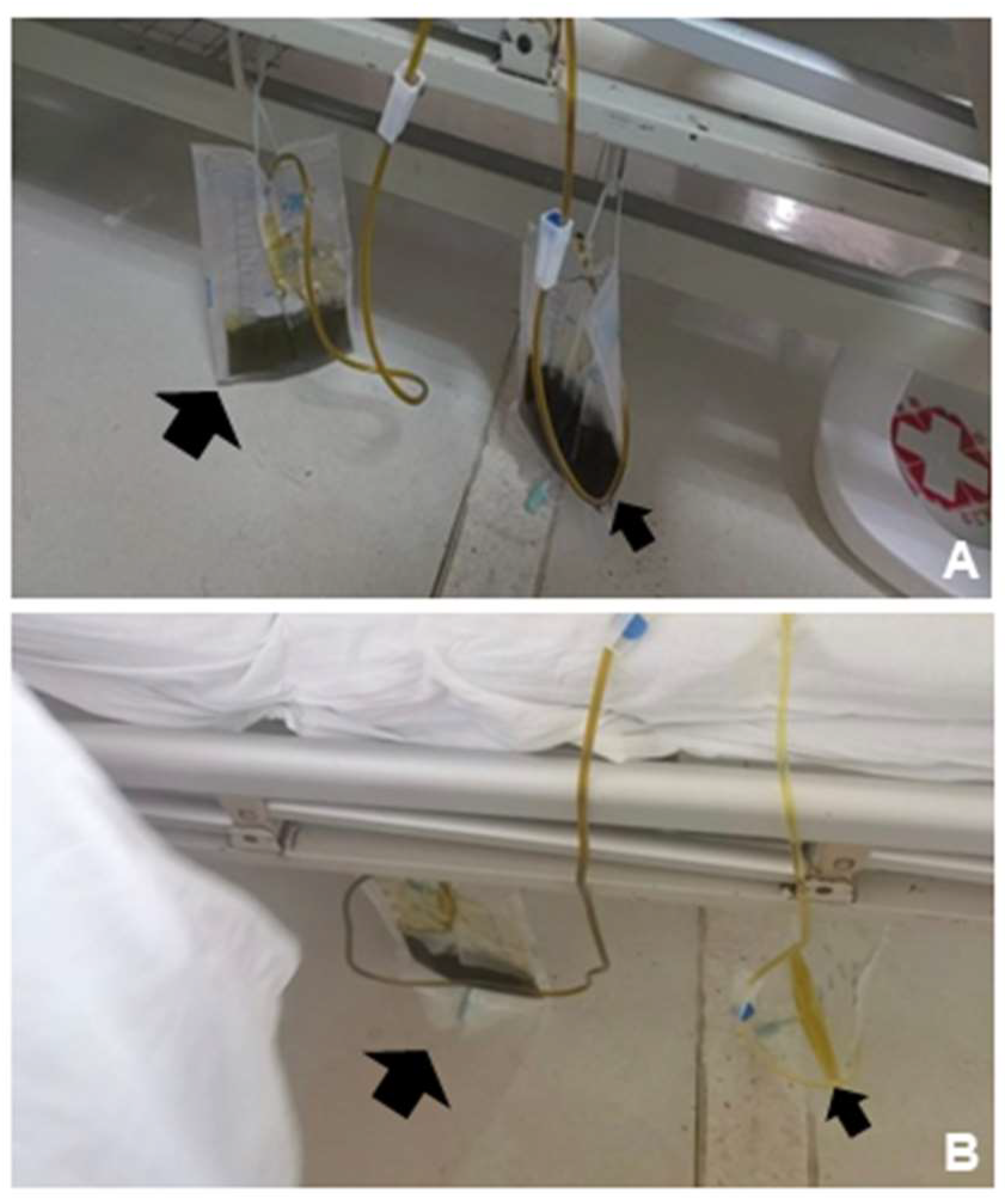

Thoracic drainage was performed and drained out dark green fluid (Figure3A, left, bigger black arrow). However, the urine drained out by catheterization was also dark green (Figure3A, right, smaller black arrow), and just as the same color (dark green) as the pleural effusion drained out. This abnormal change of urine color was unexplainable, but the color turned normal spontaneously after intravenous treatment in the everyday afternoon (

Figure 3B). Urinalysis showed: urinary glucose (+++); urinary ketone bodies (++); urobilinogen (-); urinary bilirubin (++); and urinary occult blood (+++). The total bilirubin level in the pleural effusion was 326.6μmol/L, suggesting potential biliary leak. Five days after the thoracic drainage, the pleural effusion relieved and showed no obvious pulmonary substantial lesions in reexamination. The color change of the urine, on the other hand, we suspected that it may be associated with intraoperative injury to blood vessels, and leading to the formation of a biliary-vascular fistula. Bile juice entered the blood circulation directly, and never underwent the normal metabolism of bile acids, thus causing bile juice-containing urine to be execrated by the kidneys, which may explain the dark green color of the urine. But this abnormal change automatically disappeared after intravenous treatment in the everyday afternoon, which is also unexplained and needs further investigation. .

Figure 3.

Thoracic drainage was performed and drained out dark green fluid (Figure3A, left, bigger black arrow). However, the urine drained out by catheterization was also dark green (Figure3A, right, smaller black arrow), and just as the same color (dark green) as the pleural effusion drained out. This abnormal change of urine color was unexplainable, but the color turned normal spontaneously after intravenous treatment in the everyday afternoon (

Figure 3B). Urinalysis showed: urinary glucose (+++); urinary ketone bodies (++); urobilinogen (-); urinary bilirubin (++); and urinary occult blood (+++). The total bilirubin level in the pleural effusion was 326.6μmol/L, suggesting potential biliary leak. Five days after the thoracic drainage, the pleural effusion relieved and showed no obvious pulmonary substantial lesions in reexamination. The color change of the urine, on the other hand, we suspected that it may be associated with intraoperative injury to blood vessels, and leading to the formation of a biliary-vascular fistula. Bile juice entered the blood circulation directly, and never underwent the normal metabolism of bile acids, thus causing bile juice-containing urine to be execrated by the kidneys, which may explain the dark green color of the urine. But this abnormal change automatically disappeared after intravenous treatment in the everyday afternoon, which is also unexplained and needs further investigation. .

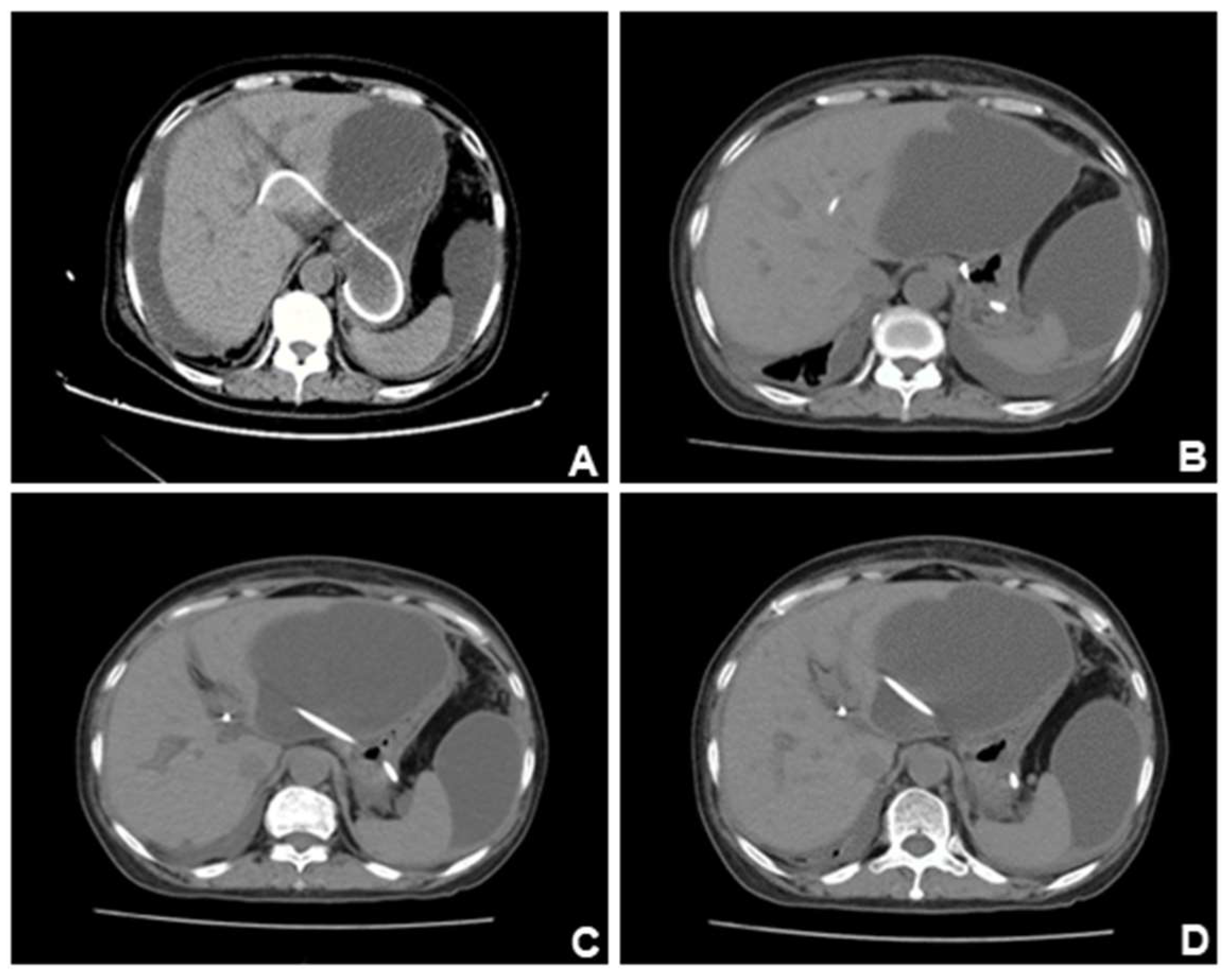

Figure 4.

However, CT scan performed one week later showed a significant increase of ascites, and the previous pleural effusion basically disappeared. Position of the stent under X-ray and CT scan. (A). The position of the stent was far from the lung, so it was considered that the diaphragm had been accidentally injured intraoperatively. (B-C). The pleural effusion gradually disappeared after closed drainage.

Figure 4.

However, CT scan performed one week later showed a significant increase of ascites, and the previous pleural effusion basically disappeared. Position of the stent under X-ray and CT scan. (A). The position of the stent was far from the lung, so it was considered that the diaphragm had been accidentally injured intraoperatively. (B-C). The pleural effusion gradually disappeared after closed drainage.

Figure 5.

CT scan of the patient ten days after the CT scan in Figure4. (A). Previous pleural effusion was almost disappeared, but abdominal and pelvic ascites appeared. (B-C). Ascites gradually increased and accumulated around the liver. (D). The lesions were compartmentalized and encapsulated internally. The patient had developed complications of EUS-BD: biliary leak. Ultrasound-guided abdominal duct drainage was attempted, but failed due to high puncture difficulty and poor expected outcome. Based on the above presentation, we suspected that this patient had developed complications of EUS-BD: biliary leak. However, this complication is still insufficient to explain the color change of the urine, which appeared on every afternoon. It’s noteworthy EUS-BD has become the prior substitute for those who failed ERCP, and enhancing understanding of its process and potential risk and preventing its complications (which can be fatal such as stent migration) are of great importance to endoscopists. Despite a high clinical success rate, EUS-BD still may be associated with adverse effects in one-seventh of the cases. Therefore, postoperative surveillance after EUS-BD must be emphasized [3-5], for patients with abnormal laboratory findings or clinical manifestations, CT scans must be done to check for possible abnormalities such as stent migration, pneumoperitoneum, or fluid collection.

Figure 5.

CT scan of the patient ten days after the CT scan in Figure4. (A). Previous pleural effusion was almost disappeared, but abdominal and pelvic ascites appeared. (B-C). Ascites gradually increased and accumulated around the liver. (D). The lesions were compartmentalized and encapsulated internally. The patient had developed complications of EUS-BD: biliary leak. Ultrasound-guided abdominal duct drainage was attempted, but failed due to high puncture difficulty and poor expected outcome. Based on the above presentation, we suspected that this patient had developed complications of EUS-BD: biliary leak. However, this complication is still insufficient to explain the color change of the urine, which appeared on every afternoon. It’s noteworthy EUS-BD has become the prior substitute for those who failed ERCP, and enhancing understanding of its process and potential risk and preventing its complications (which can be fatal such as stent migration) are of great importance to endoscopists. Despite a high clinical success rate, EUS-BD still may be associated with adverse effects in one-seventh of the cases. Therefore, postoperative surveillance after EUS-BD must be emphasized [3-5], for patients with abnormal laboratory findings or clinical manifestations, CT scans must be done to check for possible abnormalities such as stent migration, pneumoperitoneum, or fluid collection.

Author Contributions

Keyi Zhang: writing original draft, conceptualization, visualization; Qi He: writing original draft; Yu Jin: writing original draft; Jun Liu: writing original draft; Chaoqun Han: writing-review& editing, resources, Rong Lin: supervision, writing-review& editing.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82170570, 2023YFC2307000, 82270698, 82470679).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflict of Interest

All authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Baars, J.E.; Kaffes, A.J.; Saxena, P. EUS-guided biliary drainage: A comprehensive review of the literature. Endosc Ultrasound 2018, 7, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Tyberg, A. Endoscopic ultrasound guided biliary drainage: a comprehensive review. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindryckx, P.; Degroote, H.; Tate, D.J.; Deprez, P.H. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of the biliary system: Techniques, indications and future perspectives. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019, 11, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, F.P.; Rossini, L.G.; Ferrari, A.P. Migration of a covered metallic stent following endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy: fatal complication. Endoscopy 2010, 42 Suppl 2, E126–E127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, S.; Nakagawa, K.; Suda, K.; Otsuka, T.; Oka, M.; Nagoshi, S. Practical Tips for Safe and Successful Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Hepaticogastrostomy: A State-of-the-Art Technical Review. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).