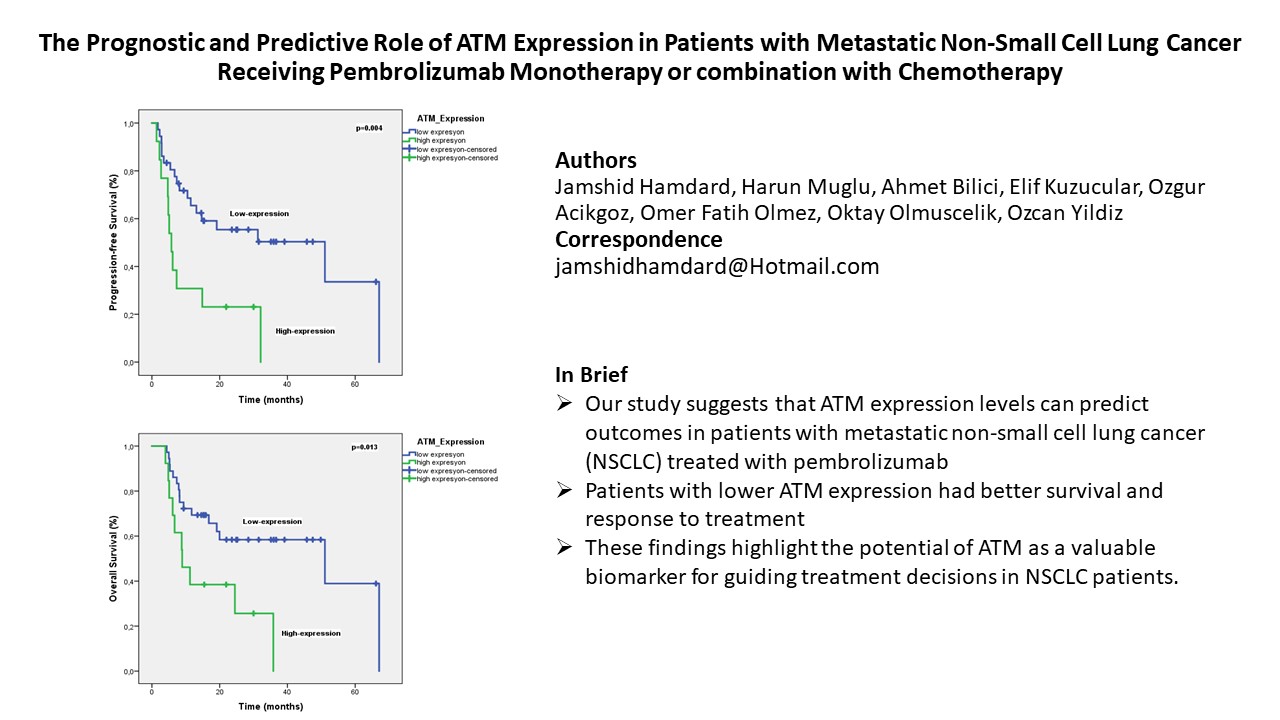

1. Introduction

ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated), encoded by the ATM gene, is a protein kinase involved in DNA damage repair. It plays a crucial role in the cellular response to double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs). When the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex detects a DSB, it activates ATM, which then phosphorylates downstream proteins to trigger DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoints, or apoptosis [

1]. The critical role of ATM lies in preserving genomic integrity by preventing DNA mutations that contribute to tumor formation and progression. Between 0.2% and 0.7% of the population carries pathogenic germline ATM gene variants, particularly those that result in a truncated protein, which increases susceptibility to breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer [

2]. Lung cancer patients exhibit a slightly elevated rate of inherited ATM gene mutations (up to 1.2-1.9%) compared to the general population, with this increase being most noticeable in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) [

3,

4].

ATM is often somatically mutated in lung tumors, in addition to germline variants. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohorts reveal that ATM is the most frequently mutated DNA damage response gene in NSCLC, with mutation rates around 9% in LUAD and 4% in lung squamous cell carcinoma [

5,

6]. The pattern of ATM mutations differs from that of common oncogenes; instead of being confined to specific areas, they are dispersed across the entire 150 kilobase gene [

7]. The high frequency of germline and somatic ATM gene variants in non-small cell lung cancer suggests their potential as prognostic biomarkers and/or predictors of therapeutic response.

Through next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis of 5,172 NSCLC tumors (using OncoPanel or MSK-IMPACT), Ricciuti et al. found that 9.7% of cases had damaging ATM mutations [

8]. Factors linked to ATM mutations included being female, having a history of smoking, non-squamous lung cancer, a high tumor mutation burden (TMB), and PD-L1 positivity [

8]. ATM-mutant tumors were more likely to also have KRAS, STK11, KMT2D, and KEAP1 mutations, but less likely to have TP53 and EGFR mutations [

8]. Vokes et al. studied ATM mutations in a significantly larger NSCLC group (N = 26,857), combining data from five separate clinical and genomic databases [

9]. Vokes et al. found that 11.2% of NSCLC cases had non-synonymous ATM mutations, confirming that these mutations are linked to KRAS mutations and high TMB, inversely linked to TP53 and EGFR mutations, and more common in lung adenocarcinoma and patients with a smoking history [

9].

Understanding the effects of the identified ATM mutations on protein production was a goal of both research groups, who utilized immunohistochemistry (Ricciuti) and reverse-phase protein arrays (Vokes) to analyze protein expression [

8,

9]. Predictably, ATM protein was less abundant in tumors with truncating mutations (like frameshifts or nonsense mutations) than in those with missense mutations.

Finally, to determine the impact of ATM mutations on patient outcomes, both studies performed correlation analyses. Ricciuti et al. discovered that while ATM mutations alone didn't influence survival or immunotherapy response, patients with both ATM and TP53 mutations had better PFS after immunotherapy [

8]. Conversely, Vokes et al. found that patients with functionally significant ATM mutations (such as truncating, splice site, or specific missense mutations) had improved OS, and that ATM-mutant patients specifically benefited from chemoimmunotherapy, showing better survival rates (9). Despite the discrepancies in reported links between ATM status and patient outcomes, both studies highlighted potential prognostic associations that require additional research.

In our study, we aimed to reinvestigate the prognostic and predictive significance of ATM expression in metastatic NSCLC patients treated with pembrolizumab alone or combined with chemotherapy (CT).

2. Materials and Methods

This study, conducted at Istanbul Medipol University between 2022 and 2024, included 49 metastatic NSCLC patients (over 18 years old, no actionable driver mutations) who received first-line pembrolizumab monotherapy or pembrolizumab with platinum chemotherapy.

The study included patients with enough tumor tissue for ATM and PD-L1 re-evaluation. Patients with poor performance status (ECOG PS 3/4) and those lost to follow-up were excluded from analysis.

Patient clinical data were gathered retrospectively from their medical records. Data on baseline characteristics such as age, gender, smoking history, histopathological type, stage of disease at diagnosis, history of curative intent therapy, T stage, presence of liver, brain, and bone metastases, PD-L1 status, first-line treatment, and ATM score were recorded after obtaining written informed consent from patients or their relatives. PD-L1 expression was determined using the PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx assay (Agilent), and results were categorized based on the tumor proportion score.

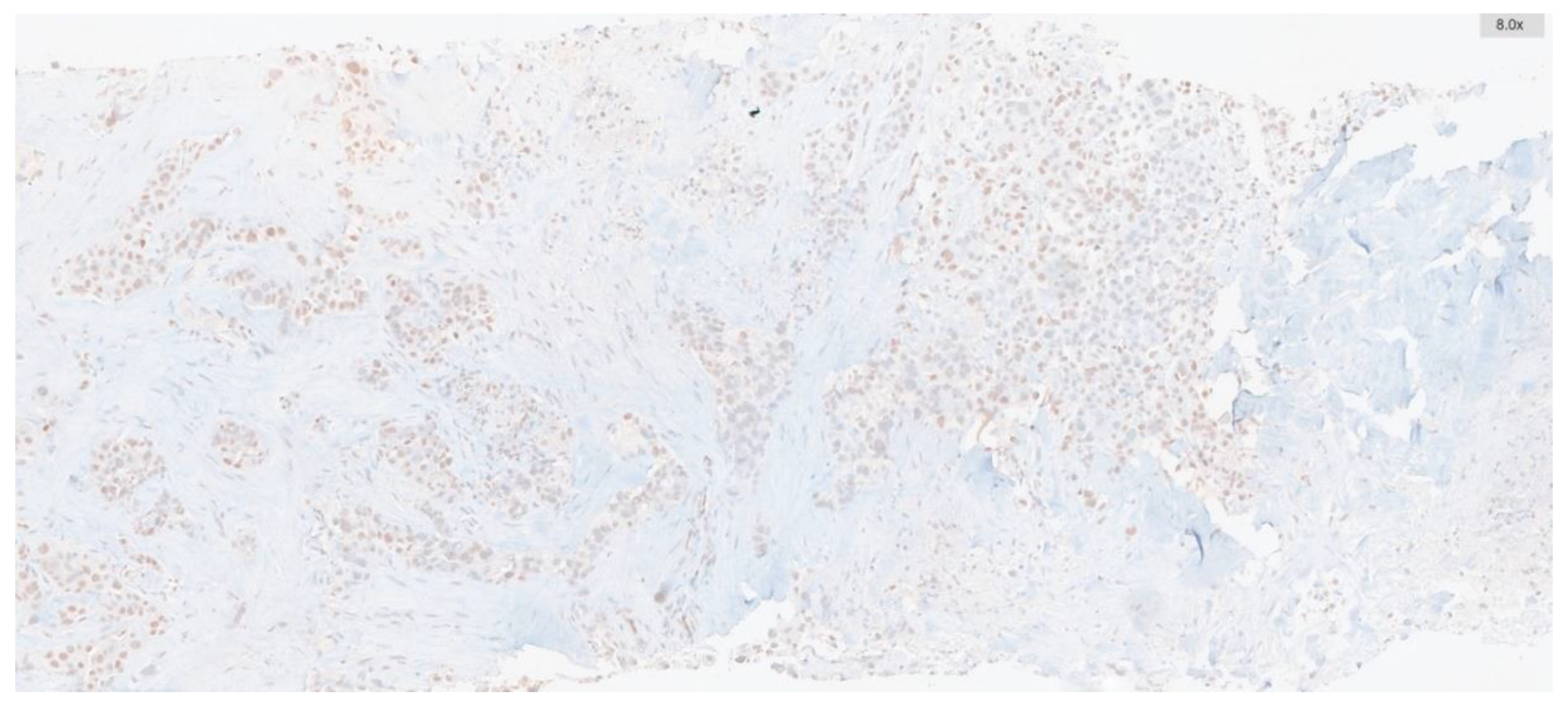

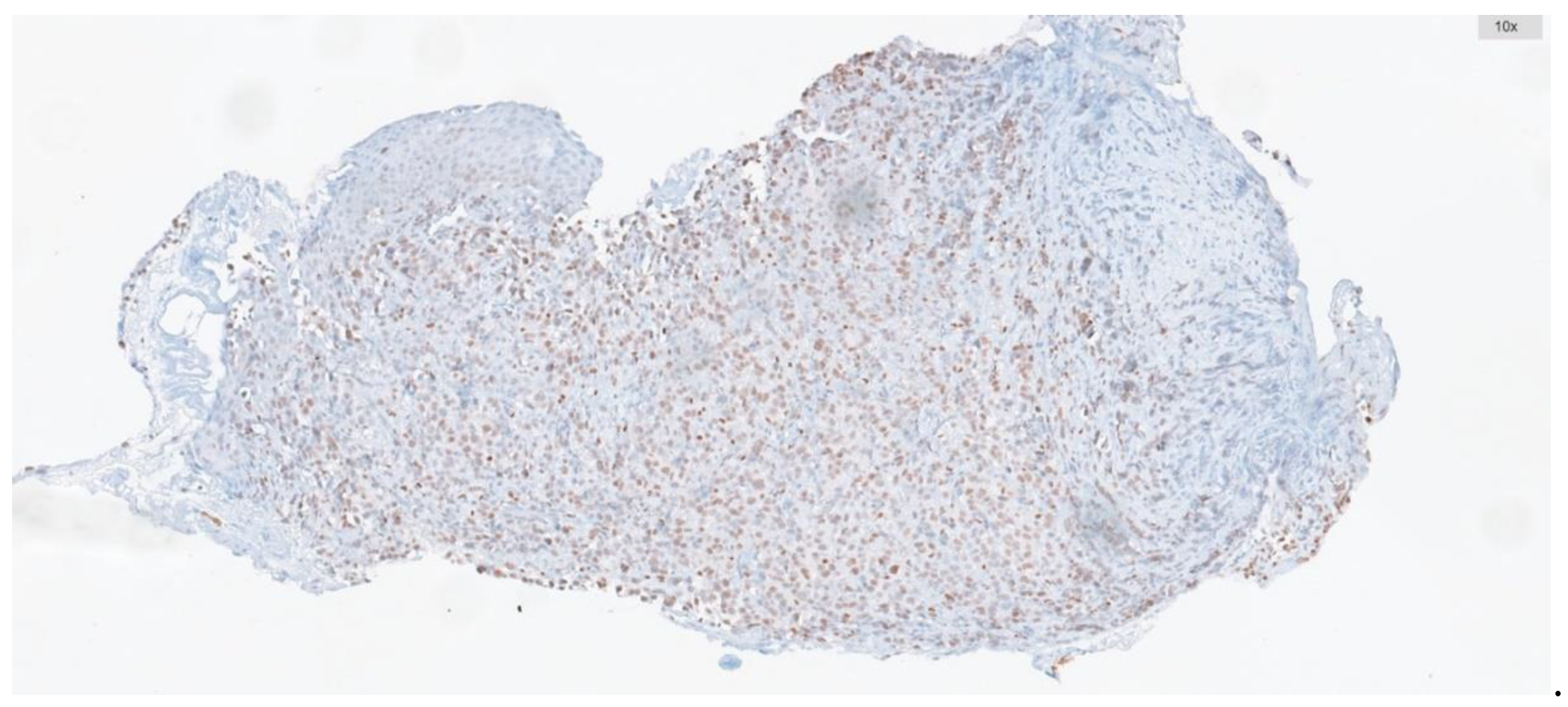

Immunohistochemistry targeting ATM was conducted on whole-tissue sections of biopsies containing tumors, including tru-cut biopsies and tumor samples from resection materials. To this end, 2 μm thick sections were prepared from paraffin-embedded blocks. Automated immunohistochemistry for ATM (using a rabbit polyclonal antibody at 1:250 dilution, SANTA CRUZ, G12) was performed on a BenchMark ULTRA staining instrument (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) for all cases. Antibody clone was applied with the UltraView DAB IHC Detection Kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. Positive external controls were included on each slide. Nuclear staining was considered positive.

The percentage of ATM-positive cells and staining intensity were scored. Intensity was graded as: negative, 0; weak, 1; moderate, 2; or strong, 3. The percentage of positive cells was graded as: 0, <5%; 1, 5%-25%; 2, 26%-50%; 3, 51%-75%; and 4, >75%. These two measurements were multiplied to obtain weighted scores ranging from 0-12, and cases were categorized into low expression group (score range: 0-5) and high expression group (score range: 6-12) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0. Baseline characteristics were described using descriptive statistics, survival analysis was performed with Kaplan-Meier curves, and the log-rank test was used for comparisons. The prognostic impact of clinicopathological features was evaluated through univariate analysis. Subsequently, Cox proportional hazards regression was used in multivariate analysis to determine independent prognostic factors for PFS and OS. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated and reported. Additionally, multivariate logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors of treatment response. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Data are shown as mean (SD), median (range), 95% CI, or percentages, as applicable. A two-sided p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Between 2022 and 2024, forty-nine patients over the age of 18 with metastatic NSCLC who had no actionable driver mutation were included in this study at the Istanbul Medipol University Department of Medical Oncology. All patients received pembrolizumab monotherapy or pembrolizumab plus platinum doublet chemotherapy in the first-line setting.

Patients who had sufficient tumor tissue for reassessing ATM and PD-L1 expression were included. Patients with ECOG PS 3/4 who were not candidates for systemic treatment and patients with loss of follow-up were excluded from the data analysis.

The clinical features of the patients were obtained retrospectively from medical records. Data on baseline characteristics such as age, gender, smoking history, histopathological type, stage of disease at diagnosis, history of curative intent therapy, T stage, presence of liver, brain, and bone metastases, PD-L1 status, first-line treatment, and ATM score were recorded after obtaining written informed consent from patients or their relatives. PD-L1 expression was assessed by PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx assay (Agilent) and expressions were categorized according to the tumor proportion score.

Immunohistochemistry targeting ATM was conducted on whole-tissue sections of biopsies containing tumors, including tru-cut biopsies and tumor samples from resection materials. To this end, 2 μm thick sections were prepared from paraffin-embedded blocks. Automated immunohistochemistry for ATM (using a rabbit polyclonal antibody at 1:250 dilution, SANTA CRUZ, G12) was performed on a BenchMark ULTRA staining instrument (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) for all cases. Antibody clone was applied with the UltraView DAB IHC Detection Kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. Positive external controls were included on each slide. Nuclear staining was considered positive.

The percentage of ATM-positive cells and staining intensity were scored. Intensity was graded as: negative, 0; weak, 1; moderate, 2; or strong, 3. The percentage of positive cells was graded as: 0, <5%; 1, 5%-25%; 2, 26%-50%; 3, 51%-75%; and 4, >75%. These two measurements were multiplied to obtain weighted scores ranging from 0-12, and cases were categorized into low expression group (score range: 0-5) and high expression group (score range: 6-12) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

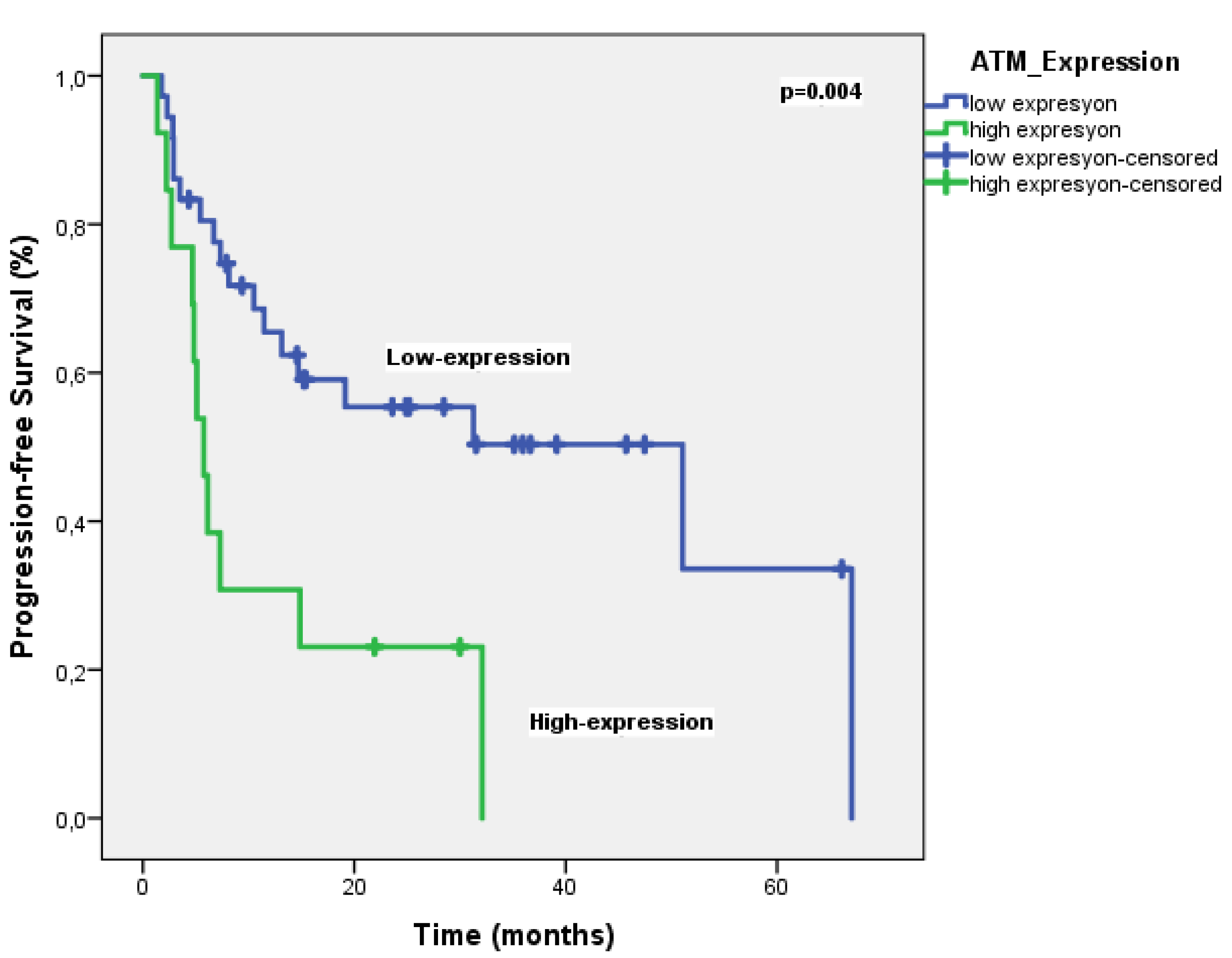

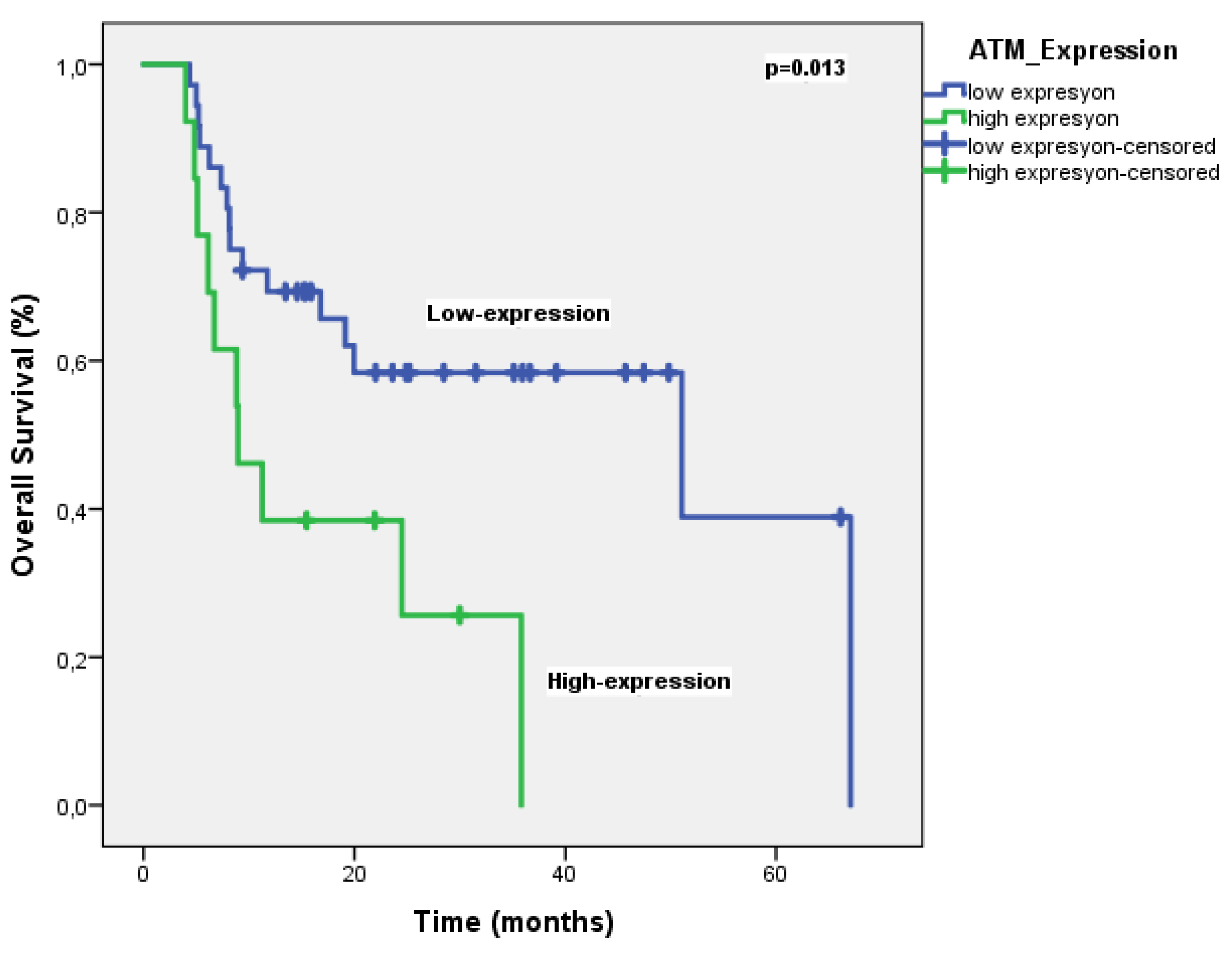

The objective response rate (ORR) was 69.4%. ATM expression was high in 37 patients (75.5%) and low in 12 patients (24.5%). With a median follow-up of 25.5 months, the median PFS was significantly longer in patients with low ATM expression compared to those with high expression (51 months vs. 5.7 months, P = 0.004) (

Figure 3). In multivariate analysis, only ATM expression was an independent prognostic factor for PFS (

Table 2). On the other hand, the median OS was significantly shorter in patients with high ATM expression compared to those with low expression (51 months vs. 8.9 months, p = 0.013) (

Figure 4). Multivariate analysis for OS identified ATM expression as the only independent prognostic factor (HR 2.48, P = 0.041) (

Table 3).

Logistic regression analysis revealed that ATM expression is a significant predictor of treatment response in patients with metastatic NSCLC receiving pembrolizumab-based therapy

. In other word, patients with high ATM expression had a significantly lower likelihood of responding to treatment (OR: 0.06, p=0.006, 95% CI: 0.08-0.48). In contrast, gender, first-line treatment type, and brain metastases were not associated with treatment response. However, liver and bone metastases were significantly linked to a higher likelihood of treatment response (OR: 26.65, p=0.023 95%CI 1.58-447 and OR: 10.99, p=0.031 95% CI 1.25-96.7 respectively) (

Table 4). These findings highlight the potential importance of ATM expression as a biomarker for predicting treatment outcomes in NSCLC.

4. Discussion

Multiple studies have confirmed that NSCLC is often characterized by DNA repair deficiencies caused by ATM mutations [

10,

11,

12]. Two recent investigations found that ATM deficiency in lung adenocarcinomas occurs in 18% to 40% of cases [

13,

14]. In our study, 75.5% of patients exhibited high ATM expression, suggesting that alterations in ATM are common in NSCLC. Petersen and colleagues identified the ATM expression index (ATM-EI) as a significant prognostic factor for both DFS and OS in stage II/III NSCLC [

15]. The authors of the Ricciuti et al. study found a correlation between complete loss of ATM expression in tumors and a higher likelihood of smoking history [

8]. However, our study did not discover a similar association. Patients with low ATM expression exhibited worse survival compared to those with high ATM expression. The effect of ATM expression on survival was more evident in advanced-stage (II/III) NSCLC patients [

15]. In our study, patients with low ATM expression had significantly longer PFS compared to those with high expression. In Vokes et al.s’ study, ATM mutations were associated with improved survival in patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy [

9]. The Ricciuti et al. study did not find a statistically significant difference in treatment outcomes (ORR, PFS, and OS) based on ATM mutation status in patients receiving PD-(L)1 immune checkpoint blockade with platinum doublet chemotherapy, primarily in the first-line setting [

8]. However, there was a numerical trend towards a higher ORR in the ATM mutant group compared to the ATM wild-type group [

8]. Our study, using logistic regression analysis, found that ATM expression is a significant predictor of treatment response in patients with metastatic NSCLC receiving pembrolizumab-based therapy. Patients with high ATM expression had a significantly lower likelihood of responding to treatment (OR: 0.06, p=0.006, 95% CI: 0.08-0.48). Our findings were thus compatible with the literature [

8].

Our findings suggest that ATM expression is a clinically relevant biomarker in NSCLC. Assessing ATM expression could aid in identifying patients who may benefit from alternative treatment approaches or targeted therapies. Additional studies are required to validate these results and explore the underlying biological mechanisms linking ATM expression to patient outcomes. Given the limitations of current biomarkers like PD-L1 and TMB, and the increasing number of treatment options, additional biomarkers are necessary to guide clinical decisions effectively. These biomarkers may also be important in early-stage treatments like neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy [

16,

17,

18].

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective design and relatively small sample size. Additionally, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to patients treated with pembrolizumab-based therapy. However, we believe that our study will contribute to the literature because it only included patients who received pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab and chemotherapy as first-line treatment and showed that ATM expression in this population is both a prognostic factor for survival and a predictive factor for treatment.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study suggests that ATM expression is a valuable biomarker for predicting patient outcomes in metastatic NSCLC treated with pembrolizumab-based treatment in the first-line setting. Further research is necessary to confirm these findings and explore the potential clinical applications of targeting ATM in this patient population. Future studies should aim to validate our findings in larger, prospective cohorts and investigate the underlying mechanisms through which ATM expression affects patient outcomes. Additionally, exploring the potential therapeutic benefits of targeting ATM in NSCLC patients with high ATM expression is warranted.

Author Contributions

J.H: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. H.M: Data curation. A.B: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology. E.K: Software, Validation, Data curation. O.A: Data curation. O.F.O, O.Y and O.O: Data curation, Visualization, Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee at the Medipol University (Istanbul, Turkey), on March 18, 2024 (decision number: 10840098-202.3.02-2000), and we confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulation.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients, or their designated relatives.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are not openly available. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Choi M, Kipps T, Kurzrock R. ATM Mutations in Cancer: Therapeutic Implications. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016 Aug;15(8):1781-91. [CrossRef]

- Hall MJ, Bernhisel R, Hughes E, Larson K, Rosenthal ET, Singh NA, et al. Germline Pathogenic Variants in the Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM) Gene are Associated with High and Moderate Risks for Multiple Cancers. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2021 Apr;14(4):433-440. [CrossRef]

- Lu C, Xie M, Wendl MC, Wang J, McLellan MD, Leiserson MD, et al. Patterns and functional implications of rare germline variants across 12 cancer types. Nat Commun. 2015 Dec 22;6:10086. [CrossRef]

- Sorscher S, LoPiccolo J, Heald B, Chen E, Bristow SL, Michalski ST, et al. Rate of Pathogenic Germline Variants in Patients With Lung Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2023 Sep;7:e2300190. [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014 Jul 31;511(7511):543-50. [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012 Sep 27;489(7417):519-25. [CrossRef]

- Thu KL, Yoon JY. ATM-the gene at the moment in non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2024 Mar 29;13(3):699-705. [CrossRef]

- Ricciuti B, Elkrief A, Alessi J, Wang X, Li Y, Gupta H, et al. Clinicopathologic, Genomic, and Immunophenotypic Landscape of ATM Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2023;29:2540-50. [CrossRef]

- Vokes NI, Galan Cobo A, Fernandez-Chas M, Molkentine D, Treviño S 3rd, Druker V, et al. ATM Mutations Associate with Distinct Co-Mutational Patterns and Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in NSCLC. Clin Cancer Res 2023;29:4958-72. [CrossRef]

- Schneider J, Illig T, Rosenberger A, Bickeböller H, Wichmann HE. Detection of ATM gene mutations in young lung cancer patients: a population-based control study. Arch Med Res. 2008 Feb;39(2):226-31. [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Kim H, Lee KJ, Choe KH, Ryu JS, Yoon HI, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of ataxia telangiectasia mutation affect lung cancer risk. Hum Mol Gen 2006;15:1181e1186. [CrossRef]

- Jialin L, Jiliang H, Lifen J, Wei Z, Zhijian C, Shijie C, et al. Variation of ATM protein expression in response to irradiation of lymphocytes in lung cancer patients and controls. Toxicology 2006;224: 138e146. [CrossRef]

- Weber AM, Drobnitzky N, Devery AM, Bokobza SM, Adams RA, Maughan TS, Ryan AJ. Phenotypic consequences of somatic mutations in the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated gene in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016; 7:60807–60822. [CrossRef]

- Villaruz LC, Jones H, Dacic S, Abberbock S, Kurland BF, Stabile LP, et al. ATM protein is deficient in over 40% of lung adenocarcinomas. Oncotarget. 2016; 7:57714–57725. [CrossRef]

- Petersen LF, Klimowicz AC, Otsuka S, Elegbede AA, Petrillo SK, Williamson T, et al. Loss of tumour-specific ATM protein expression is an independent prognostic factor in early resected NSCLC. Oncotarget. 2017 Jun 13;8(24):38326-38336. [CrossRef]

- Provencio M, Calvo V, Romero A, Spicer JD, Cruz-Bermúdez A. Treatment sequencing in resectable lung cancer: the good and the bad of adjuvant versus neoadjuvant therapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ B 2022;42:711–28. [CrossRef]

- Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, Csóśzi T, Vynnychenko I, Goloborodko O, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB–IIIA non–small cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomized, multicenter, open-label, phase III trial. Lancet 2021;398:1344–57. [CrossRef]

- Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, Provencio M, Mitsudomi T, Awad MM, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1973–85. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).