Introduction

Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI/H5N1) has spread in dairy cows and pigs in the United States. In September 2024, the spread of HPAI/H5N1 infections among dairy cows in the United States was reported, and the scale of the outbreak was much more serious than expected [

1]. Cases of HPAI/H5N1 infection of human or livestock infections have been increasing in the country, with HPAI/H5N1 being detected in live cattle and dairy products [

2]. Experts believe the virus may be evolving in conjunction with seasonal influenza virus epidemics. Since March 2024, 14 cases of HPAI/H5N1 infection have been reported [

3]. Virologists and medical staff considered this as a worrying development, fearing that the U.S. government’s slow and lax response to the HPAI/H5N1 virus will once again put the entire world at risk of a pandemic. HPAI/H5N1 has been spreading for the past few years, causing the deaths of millions of wild birds and farmed poultry, as well as tens of thousands of marine and terrestrial mammals [

4]. The development of a potentially troubling situation within the U.S. is currently creating increasing public concern. For example, dairy cows have shown a high HPAI/H5N1 viral load, causing recurring problems for dairy farmers with poultry. Furthermore, the continued spread of HPAI/H5N1 among dairy cows and pigs, as well as its frequent detection in raw milk, could indicate a pandemic [

5,

6]. Most worryingly, in human HPAI/H5N1 infections have increased, and the risk of a potential pandemic has been increasing since September 2024. However, compared with the situation during the coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020, we are now better prepared to prevent an emerging infectious disease, should HPAI/H5N1 infection become a viral pandemic. In contrast, the U.S. government believes that preparedness for an HPAI/H5N1 epidemic is not very good [

7].

In March 2024, the HPAI/H5N1 virus was detected for the first time in dairy cows in Texas, while the HPAI/H5N1 infection continues to spread among dairy cows across the country [

3]. HPAI/H5N1 infection in wild bird populations has a very high mortality rate and has caused the extinction of poultry and seabirds over the past few years [

8,

9]. The HPAI/H5N1 virus also causes fatal infections in many mammals that come into contact with infected birds. The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) under the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported 675 HPAI/H5N1 infections in dairy cows across 15 states [

10]. This number of infected dairy herds are only those cases known to APHIS officials. The actual number of cases may be higher. The USDA has since required HPAI/H5N1 testing for dairy cows before moving them between states [

11].

The most worrying situation is the increase in human HPAI/H5N1 infections. According to a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 55 cases of human HPAI/H5N1 infection have been reported in the U.S. as of October 2024 [

12]. Of the total number of confirmed cases of HPAIV/H5N1 infection, 29 were confirmed in California [

13]. In almost all cases, HPAI/H5N1 infection, transmission was believed to have originated from dairy cows or poultry [

14]. However, the source of infection was unknown in 2 cases [

15]. The U.S. government speculates that the symptoms and route of infection may have not been reported in some cases. Therefore, when the CDC tested 115 dairy workers in Michigan and Colorado, 7% of the dairy workers were found to have had a recent HPAI/H5N1 infection [

15,

16]. The zoonotic transmission of HPAI/H5N1 from infected dairy cows to humans has been confirmed, although no evidence of human-to-human transmission has been obtained [

17]. However, on October 6, 2024, a patient who had been seriously ill with the HPAI/H5N1 virus had died in Louisiana [

18], which is the first reported mortality from HPAI/H5N1 infection in the U.S. [

19]. The deceased individual was elderly, had underlying conditions, and had been in contact with pets and wild birds. As no spread of HPAI/H5N1 infection has been reported in the immediate vicinity of the case, the risk to the general public has been assessed as still low [

20]. Meanwhile, the CDC reported that an HPAIV/H5N1 virus specimen isolated from a patient in Louisiana showed characteristics similar to those of a specimen isolated from a 13-year-old female patient who became seriously ill in western Canada in November 2024 [

21]. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report, as of mid-December 2024, 954 cases of HPAI/H5N1 infections have been confirmed worldwide, with 464 (49%) deaths. Humans can also function as incubators for the virus. Each time a human is infected, the virus gains a fresh opportunity to evolve into a form capable of infecting humans [

22].

As we have experienced with the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread vaccination is important to prevent viral spread. To achieve this, medical professionals and virologists must understand the virological and biological characteristics of HPAI/H5N1 and its mutant variants. Our research team compared the infectivity of HPAIV/H5N1 to humans and dairy cows by molecular pathological analysis of mammary gland tissues collected from humans and dairy cows. The analysis revealed that the receptors for the HPAI/H5N1 virus are more frequently expressed in dairy cows than in human tissues. Furthermore, in silico analysis revealed that HPAI/H5N1 specimens isolated from infected dairy cows were capable of infecting humans. Similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), HPAI/H5N1 can also infect lions, as observed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, people around the world should emphasize the implementation of One Health to prevent HPAI/H5N1 virus infection from becoming a pandemic.

Materials and Methods

1.Publicly available virus sequences: a human N1H1 influenza virus, N5H1, Indonesia N5H1, Bovine N5H1. Human H1N1 influenza virus; A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018. We purchased HA protein obtained from H1N1 virus from Sino Biological Inc. BDA, Beijing, 100176, P.R.China. Indonesia H5N1; gene HA protein; Influenza A H5N1 (A/Indonesia/5/2005) Hemagglutinin (HA). We purchased HA protein obtained from Bovine N5H1 from Sino Biological Inc. BDA, Beijing, 100176, P.R.China. Bovine H5N1; nfluenza A virus gene (A/bovine/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024(H5N1)) segment 4 hemagglutinin (HA) gene, complete cds. We purchased HA protein obtained from Bovine H5N1 from Sino Biological Inc. BDA, Beijing, 100176, P.R.China.

2. Detection of SAα2,3Gal (α2,3SA) and SAα2,6Gal (α2,6SA) in respiratory tissues, mammary gland tissues, conjunctuve obtained from human, dairy cow, Lion as big feline animal: For detection of sialyloligosaccharides reactive with SAα2,3Gal- or SAα2,6Gal-specific lectins, the tissue sections were incubated with 250 µl of FITC-labeled Sambucus nigra (SMA) lectin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and biotinylated Maackia amurensis (MAA) lectin (Vector Laboratories) overnight at 4oC.

3. Solid-phase binding assay: Microtitre plates (Nunc) were incubated with fourfold serial dilutions (2.5, 0.625, 0.156, 0.039, 0.01, 0.002 and 0.001 μg ml-1) of the sodium salts of sialylglycopolymers (Yamasa Corporation Co. Ltd.)— Neu5Acα2,3Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ1-poly-Glu (α2,3SA) and Neu5Acα2,6Ga lβ1,4GlcNAcβ1-poly-Glu (α2,6SA)—in PBS at 4 °C overnight. The next day, glycopolymer solutions were removed and non-specific binding was blocked by the addition of PBS containing 4% BSA at room temperature for 1 h. Plates were washed with cold PBS, and then solutions containing influenza viruses.

4. Phylogenetic Analysis and Annotation: Reference genomes and amino acids of hemagglutinin (HA) from H1N1 virus, H5N1, Indonesian H5N1 (called as Indonesian H5), Bovine H5N1 (called as Bovine H5) were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Orthologs of the National Library of Medicine.

5. Analyzes the three-dimensional structure of the binding site between SAα2,3Gal (α2,3SA) and SAα2,6Gal (α2,6SA) and amino acids of hemagglutinin (HA) from H1N1 virus, H5N1, Indonesian H5N1 (called as Indonesian H5), Bovine H5N1 (called as Bovine H5): Spanner is a structural homology modeling pipeline that threads a query amino-acid sequence onto a template protein structure. Spanner is unique in that it handles gaps by spanning the region of interest using fragments of known structures.

6. Statistical Analyses: Differences between vaccinated and naturally-infected groups depicted in Table 1 were assessed using Mann Whitney U test for continuous variables, or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. P<0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.0.2, and Graphpad Prism v.9.0.

Details of materials and methods are shown in supplementary data online.

Results

Expression of the α2.3SA and α2.6SA Receptors in Respiratory, Mammary Gland, and Conjunctival Tissues Obtained from Humans and Dairy Cows

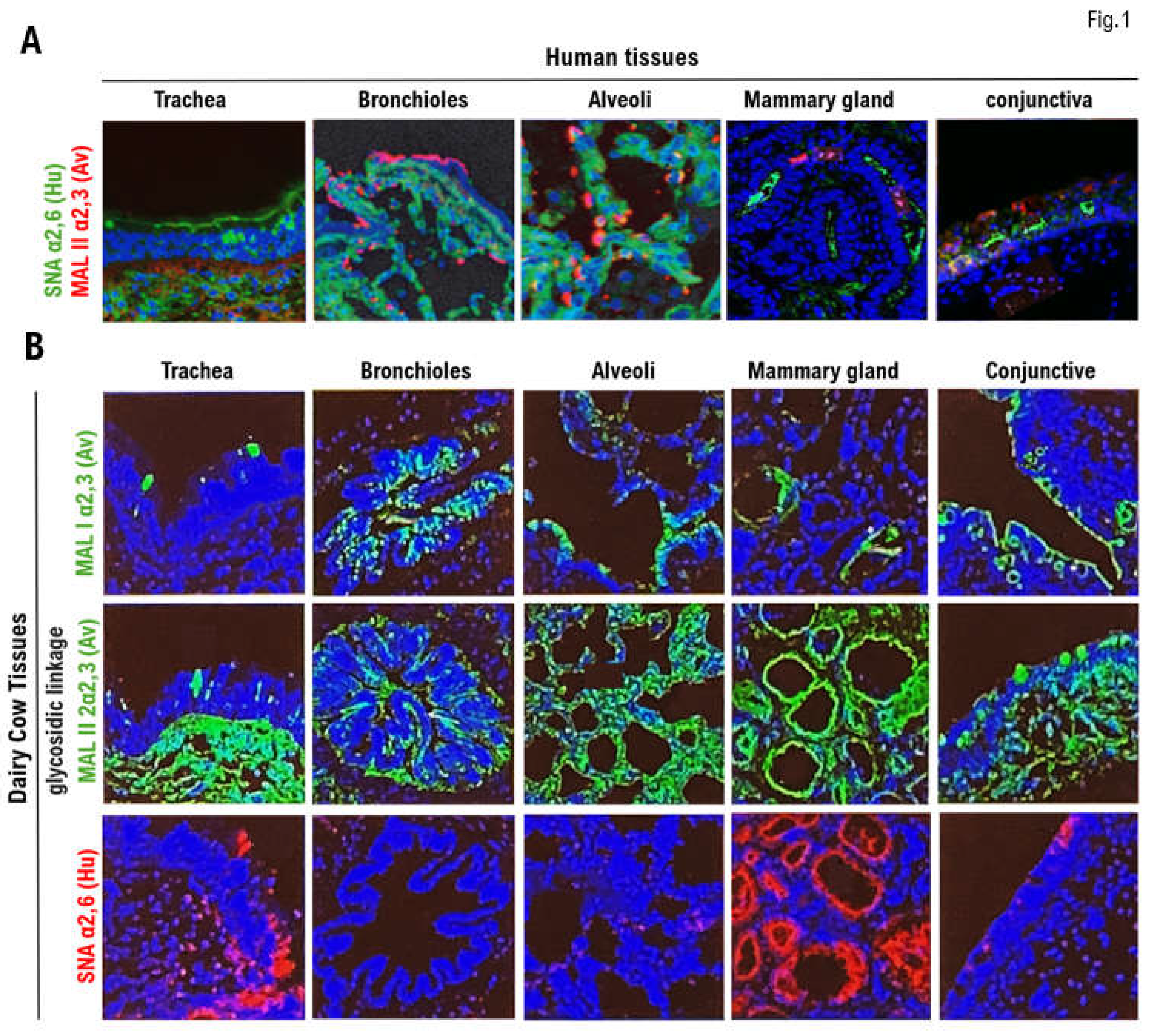

The expression of the HPAI/H5N1 virus receptor α2.3SA (red) and human influenza virus receptor α2.6SA (green) in human respiratory (trachea, bronchioles, and alveoli), mammary gland, and conjunctival tissues is shown in

Figure 1A. The α2.6SA receptor was expressed in all tissues but particularly prominently in the bronchioles and alveoli. Furthermore, α2.6SA was weakly expressed in the human mammary gland and conjunctival tissues. Human influenza viruses enter the body and bind to the mucosal epithelial cells of the bronchioles and alveoli to establish infection. Human bronchioles and alveoli exhibited marked expression of α2.3SA (

Figure 1A, Supplementary Table 1). Human mammary and conjunctival tissues showed weak expression of the α2.3SA receptor. Similarly, HPAI/H5N1 invades the body and binds to the mucosal epithelial cells of the bronchioles and alveoli to establish infection.

The expression of the HPAI/H5N1 α2.3SA receptor and human influenza virus α2.6SA receptor in the respiratory (trachea, bronchioles, and alveoli), mammary gland, and conjunctival tissues obtained from dairy cows is shown in

Figure 1B. To investigate the expression of α2.6SA, respiratory tissues were incubated with SMA lectin (red) for 12 h at 4°C. The tissues were then washed with PBS and observed under a confocal laser microscope (LEICA SP8 FALCON, Wetzlar, Germany). The expression of α2.6SA was observed in the respiratory tissues, specifically the bronchioles and alveoli. To examine the expression of α2.3SA, we incubated respiratory tissues (trachea, bronchioles, and alveoli) from lions with MAL I lectin (red) or MAL II lectin (red) for 12 h at 4°C. α2.6SA was strongly expressed in mucosal epithelial tissue of the trachea and mammary gland tissue cells. However, α2.6SA was not detected in the bronchioles, alveoli, or conjuctiva (

Figure 1B, Supplementary Table 2). Therefore, human influenza viruses invade the body from the outside and bind to the mucosal epithelial cells of the bronchioles and alveoli to establish infection. α2.3SA was highly expressed in all bovine tissues compared with those in human tissues.

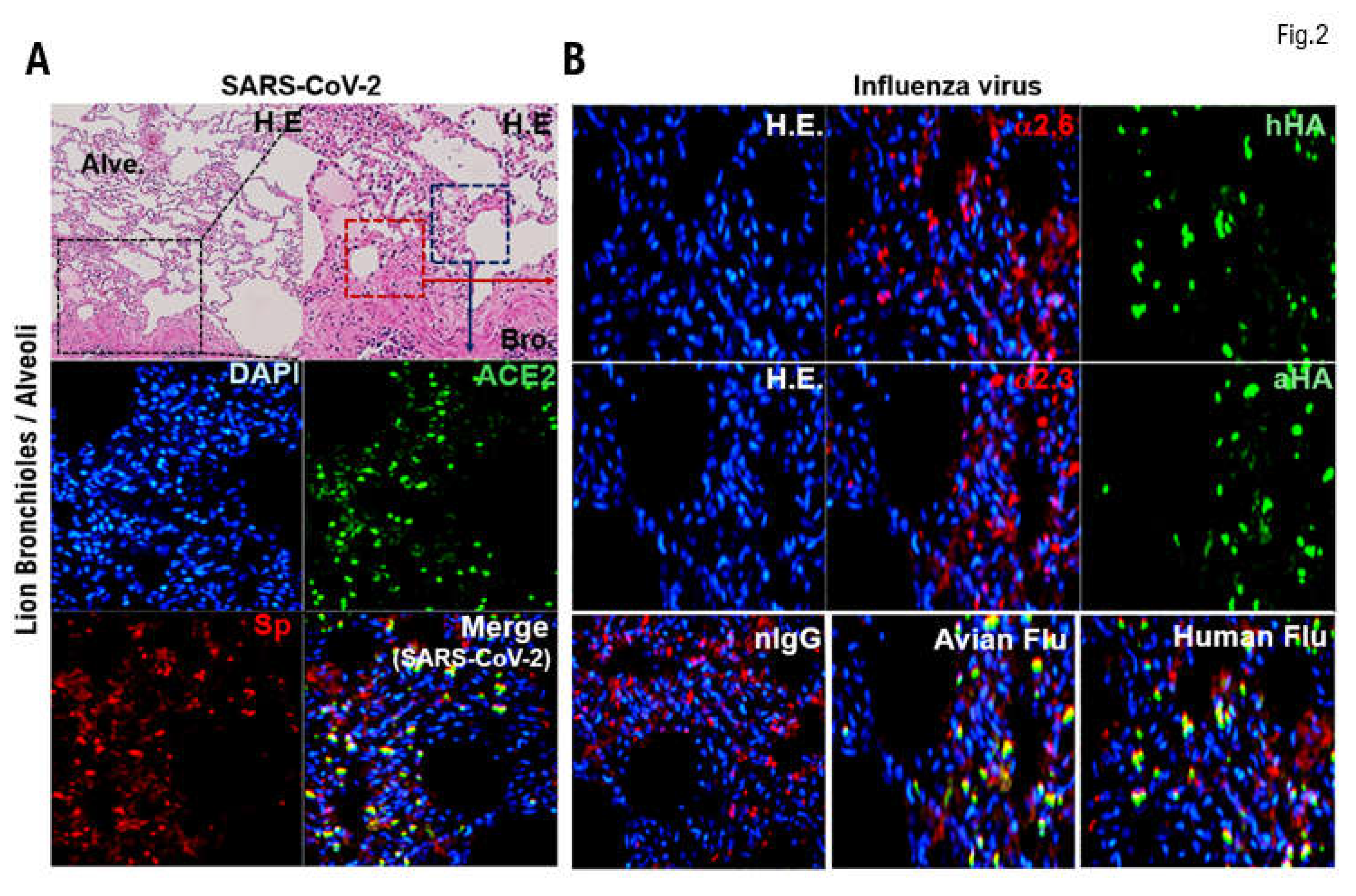

Expression of the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2, α2.3SA, and α2.6SA Receptors in Respiratory Tissues Obtained from Lions

Many cases have been reported of lions in zoos being infected with SARS-SoV-2 via transmission from zoo keepers with COVID-19. Therefore, our medical staff confirmed by immunohistochemical staining the expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is the host’s receptor for SARS-CoV-2 [

23], in respiratory tissues (bronchioles and alveoli) obtained from lions. ACE2 (green) was more strongly expressed in the mucosal epithelial cells of the bronchioles than those of the alveoli (

Figure 2A, Supplementary Table 3). Therefore, we attached recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein to the respiratory tissues (bronchioles and alveoli) obtained from lions and incubated them at 4°C for 12 h. The tissues were then washed with PBS and observed under a confocal laser microscope (LEICA SP8 FALCON, Wetzlar, Germany). The SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein (yellow) bound to mucosal epithelial cells in the bronchioles more than those in the alveoli (

Figure 2A, Supplementary Table 3). Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 can infect the respiratory tissues of lions (bronchioles and alveoli) and causes COVID-19–like symptoms.

To investigate the expression of the α2.6 receptor for human influenza virus, respiratory tissues (bronchioles and alveoli) from lions were incubated with SMA lectin (red) for 12 h at 4°C. The tissues were then washed with PBS and observed under a confocal laser microscope. α2.6 (red) was expressed in the bronchioles and alveoli (

Figure 2B, Supplementary Table 3). To examine the expression of α2.3 receptor for HPAI/H5N1, we incubated respiratory tissues (bronchioles, alveoli) from lions with MAL I lectin (red) or MAL II lectin (red) for 12 h at 4°C. The tissues were then washed with PBS and observed under a confocal laser microscope. α2.3 (red) was also expressed in the bronchioles and alveoli. Therefore, α2.3 and α2.6 were expressed in the facial membrane epithelial cells of respiratory tissues (bronchioles, alveoli) obtained from lions (

Figure 2B, Supplementary Table 3). Subsequently, we attached hemagglutinin (HA) from human influenza virus or HPAI/H5N1 to the respective treated tissues and incubated them at 4°C for 12 h. After incubation, we added anti-HA monoclonal antibody (green) to each treated tissue and incubated at 4°C for 12 h. After incubation, we observed the cells under a confocal laser microscope (LEICA SP8 FALCON). α2.6 and human influenza virus HA binding complex (yellow) or α2.3 and HPAI/H5N1 HA binding complex (yellow) were observed in the mucosal cells of the bronchiole and alveoli specimens. After incubation, we observed the cells under a confocal laser microscope (LEICA SP8 FALCON) (

Figure 2B, Supplementary Table 3).

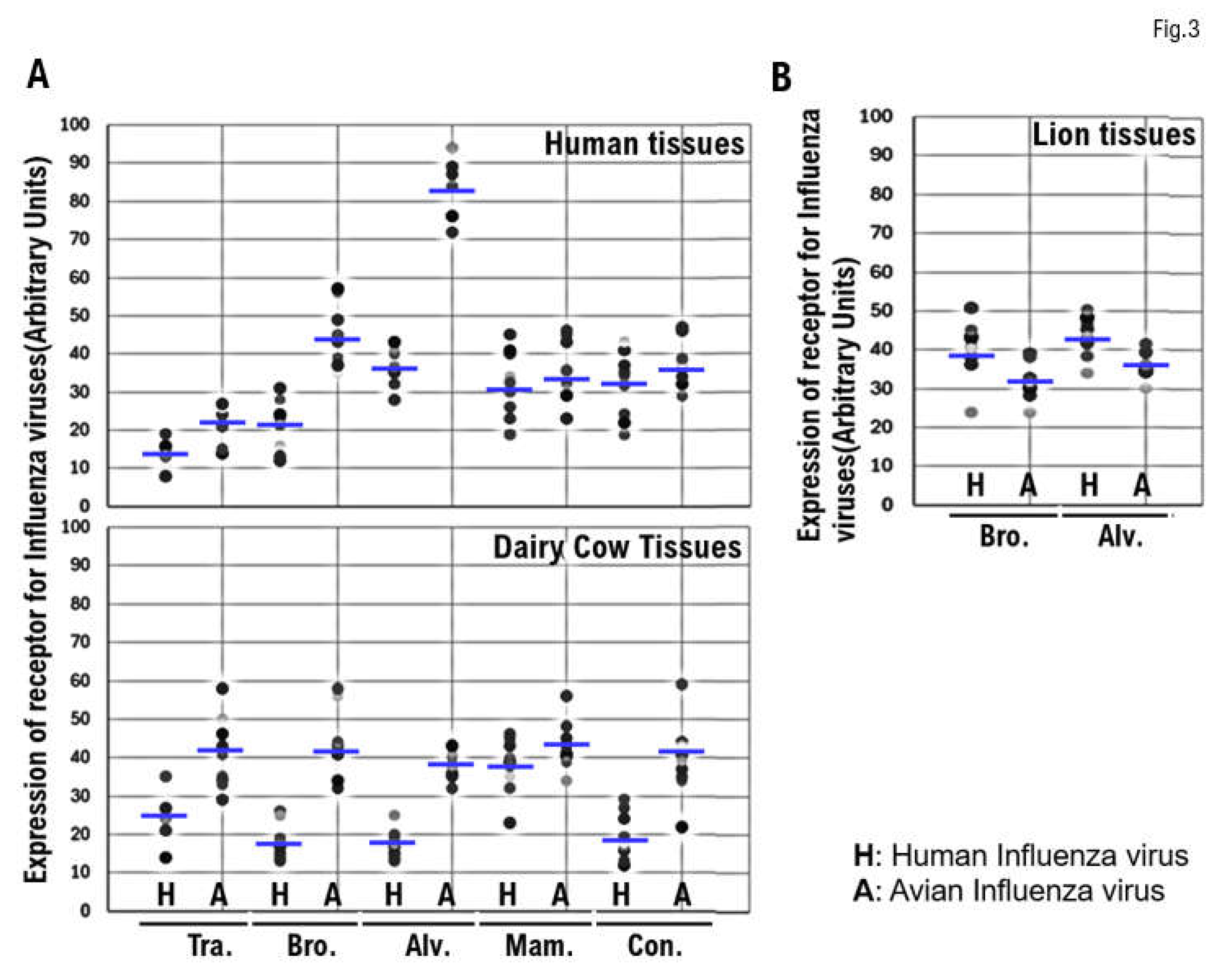

Comparison of the Expression of α2.6SA and α2.3SA Among Human, Dairy Cow, and Lion Tissues

The expression levels of host receptors α2.3SA and α2.6SA were quantified using an image analysis and measurement system (WinROOF2023, Mitani Corporation, Visual System, Fukui-shi, Fukui, Japan) (

Figure 3, Supplementary

Figure 1.). The analysis revealed that the expression level of α2.3SA was higher than that of α2.6SA in all human or dairy cow tissues (

Figure 3A, Supplementary

Figure 1.). Furthermore, the expression of α2.3SA was higher than that of α2.6SA in all dairy cow tissues (

Figure 3A, Supplementary

Figure 1.). Therefore, HPAI/H5N1 seems to be more likely to infect dairy cows than humans. The expression of α2.6SA was higher than that of α2.3SA in lion bronchiolar and alveolar tissues (

Figure 3B). This may be one of the reasons for the current spread of HPAI/H5N1 infections in dairy cows across the United States.

Binding Activity of HPAI/H5N1 Variants Isolated from Infected Dairy Cows to the Receptor (α2.6SA) for the Human Influenza Virus

The HPAI/H5N1 Indonesia H5 variant isolated from an Indonesian in 2005 is infectious to both α2.6SA and α2.3SA [

24,

25]. HPAI/H5N1 has a very low possibility of infecting α2.6SA [

22]. However, HPAI/H5N1 can mutate in the pig body and acquire infectivity to humans. An HPAI/H5N1 variant has been transmitted to humans from infected dairy cows. We investigated the binding affinity/recognition of HPAI/H5N1 bovine H5 variant isolated from infected dairy cows to α2.6SA or α2.3SA using an analog of either (LSTc or LSTa, respectively). HA of bovine H5 recognized and binds to LSTc or LSTa (

Figure 4A, 4D). We also used HPAI/H5N1 Indonesia H5 as the control virus and examined the binding affinity/recognition of Indonesia H5 to α2.6 or α2.3 using LSTc or LSTa, respectively. Indonesia H5 mut., a variant of Indonesia H5, binds to α2.6SA or α2.3SA but with a weaker affinity than that of Indonesia H5. In silico analysis showed strong binding affinity/recognition between the positive control Indonesia H5 and α2.6SA or α2.3SA (

Figure 4B, 4E). However, Indonesia H5 mut. showed a somewhat weak binding affinity to α2.6SA or α2.3SA (

Figure 4C, 4F). Similar to that with Indonesia H5, the binding affinity/recognition between bovine H5 and α2.6 or α2.3 was observed (

Figure 4A–4F). SMA lectin staining revealed that the binding affinity of bovine H5 was stronger than that of Indonesia H5 mut. to α2.6 or α2.3 . In other words, HPAI/H5N1 mutated within the dairy cow’s body during infection, resulting in an HPAI/H5N1 variant that is infectious to humans.

To further test the receptor specificity of bovine H5N1, we measured the binding affinity/recognition of recombinant bovine HA to either α2.3SA- or α2.6SA-linked sialic acid by performing established assays using either α2.3SA- or α2.6SA-linked sialylglycopolymers. As expected, Indonesia H5 HA showed a clear preference for α2.6SA-linked sialic acid, whereas HPAI/H5N1 HA showed a clear preference for α2.3SA-linked sialic acid (

Figure 4G, 4H). Furthermore, human Isumi-H1N1 virus HA showed non-preference for α2.3SA-linked sialic acid, whereas HPAI/H5N1 virus HA showed non-preference for α2.6SA-linked sialic acid (

Figure 4G, 4H). Indonesia H5 HA showed a clear preference for both α2.6SA- and α2.3SA-linked sialic acid. Similarly, bovine H5 HA also showed a clear preference for both α2.3SA- and α2.6-linked sialic acid (

Figure 4I, 4J). A single mutation (Q226L) within the 220-loop of H5N1 increases infectivity to humans (Supplementary

Figure 1). Thus, HPAI/H5N1 can mutate in the dairy cow’s body and acquire the ability to infect humans.

Comparison of α2.3SA expression between human and dairy cow mammary tissues

Paraffin-embedded human and bovine mammary tissue slices were incubated with recombinant H5N1 HA protein-His Tag for 12 h at 4°C. The labeled anti-His Tag antibody was then added to the treated human and bovine mammary tissue slices and incubated for 12 h at 4°C. Nuclear staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was performed. We then incubated paraffin-embedded human tissue slices with anti-avian α2.3 antibody at 4°C for 12 h and then stained the nuclei with DAPI. The stained tissue sections were photographed using a confocal laser microscope (LEICA SP8 FALCON), mainly after adjusting the z-axis. We then saved each image as a file and merged the image files for the DAPI, HA, and α2.3SA samples (

Figure 5A). The expression of host α2.3SA was quantified using an image analysis and measurement system (WinROOF2023, Mitani Corporation). The expression levels of host α2.3SA was then plotted on a graph (

Figure 5B). The expression of α2.3SA in bovine mammary gland tissue was approximately three times higher than that in human mammary gland tissue (

Figure 5B).

Discussion

According to the WHO, as of mid-December 2024, 954 people have been infected with HPAIV/H5N1 worldwide, 464 (49%) of whom have died [

26]. As we have found during the COVID-19 pandemic, the key the early production and dissemination of effective vaccines prevents the spread of infection. To achieve this, medical professionals, virologists, and other experts must understand the virological and biological characteristics of HPAI/H5N1 and its mutant variants. Our research team conducted a molecular pathological analysis using human and dairy cow mammary gland tissues to compare the infectivity of the HPAI/H5N1 virus in humans and dairy cows. The results of the molecular pathological analysis revealed that the α2.3 receptor for HPAI/H5N1 was more highly expressed in dairy cow tissues than in human tissues. In silico analysis further demonstrated that HPAI/H5N1 isolated from infected dairy cows were capable of infecting humans. Similar to SARS-CoV-2, HPAI/H5N1 can infect lions. In other words, since HPAI/H5N1 and its mutant variants are both emerging and zoonotic diseases, other wild animals, livestock, and pets can also become infected by HPAI/H5N1, facilitating the spread of infection. Therefore, responding as part of One Health is a crucial preventive measure [

27].

Human HPAI/H5N1 infections are extremely rare. However, when the CDC tested 115 dairy workers in Michigan and Colorado, they found that 7% of the workers had had a recent HPAIV/H5N1 infection [

28]. The transmission of HPAI/H5N1 from infected dairy cows to humans has been confirmed, but no evidence indicates human-to-human transmission of HPAI/H5N1. The Indonesia H5 variant is capable of zoonotic transmission between humans and birds. Because of a mutation in the amino acid molecule in the HA, the Indonesia H5 variant is able to recognize and bind to the α2.6 receptor for human influenza viruses and the α2,3 receptor for HPAI/H5N1. HPAI/H5N1 can also infect non-avian species, such as pigs, and that mutations in the viral backbone molecule within the host endows the Indonesia H5 variant with infectivity to humans. Such mutations likely facilitate the spread of zoonotic viral diseases. Our in silico analysis revealed that, like the Indonesia H5 variant, the bovine variant recognizes and binds to the α2.6SA receptor for human influenza virus and α2.3SA receptor for HPAI/H5N1. In a similar mechanism, SARS-CoV-2 isolated from mink mutates within the mink, resulting in a SARS-CoV-2 variant that is more infectious to humans. Like SARS-CoV-2, HPAI/H5N1 can also be transmitted between different species.

In the U.S., where HPAI/H5N1 infection is spreading among cattle, the seasonal influenza virus epidemic season has already begun. Virologists are concerned that humans infected with both human influenza viruses and HPAI/H5N1 may asymptomatically produce new HPAI/H5N1 strains. The U.S. government plans to stockpile millions of doses of the H5N1 vaccine. However, the current method for making influenza vaccines is time-consuming and laborious. Newer vaccines that do not rely on the use of eggs, such as those that use mRNA, induce mucosal immunity; therefore, mRNA-based vaccines may be superior vaccines. Preclinical testing of an mRNA-based vaccine against HPAI/H5N1 has been reported. The study demonstrated that a vaccine based on the HPAI/H5N1 2.3.4.4b lineage provided protection to ferrets subsequently infected with HPAI/H5N1 [

29]. Because mRNA-based vaccination prevented the development of severe COVID-19 symptoms, an mRNA-based vaccine against HPAI/H5N1 may also induce the same effect. The prevalence of HPAIV/H5N1 in the U.S. and other countries has been confirmed not only in dairy cows but also among cats and dogs living near dairy barns. Therefore, the efficacy of an mRNA-based vaccine against HPAI/H5N1 must be established in dairy cows, cats, and dogs [

29,

30].

Molecular histopathological analysis was also performed using respiratory tissue obtained from lions. The expression of α2.3SA virus was observed in mucosal epithelial cells of the bronchioles and alveoli. Thus, similar to SARS-CoV-2, HPAI/H5N1 infection may also affect several non-human species. In this study, no experiments using live viruses were performed. Therefore, histopathological analysis alone can provide information on the expression of α2.3SA or α2.6SA for each virus but cannot provide accurate information on their infectivity. Future studies involving infection experiments in a Biohazard Level 3 infection laboratory must be conducted to understand the virological and biological properties of HPAI/H5N1 and its variants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contribution: TH, KS, and TD were involved in the study design, data collection, data review and interpretation, and manuscript writing. TH, KS, and TD were involved in the literature search, study design, data collection, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. TH, KS, and TD were involved in data collection and interpretation. TH, KS, and TD were involved in data collection and interpretation and manuscript writing. TH, KS, and TD were involved in the study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. TH and IK were the medical leads for AstraZeneca, and they participated in the data collection and evaluation and manuscript writing and editing. TH and IK were the lead physicians and were involved in the study design and conduct, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript review.

Funding

This clinical research was performed using research funding from the following: Japan Society for Promoting Science for TH (grant no. 19K09840), START-program Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) for TH (grant no. STSC20001), National Hospital Organization Multicenter Clinical Study for TH (grant no. 2019-Cancer in general-02), and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant no. 22ym0126802j0001), Tokyo, Japan. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

This research includes clinical/human materials, therefore Informed consent is required.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on various websites and have also been made publicly available. More information can be found in the first paragraph of the Results section. The transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version at

https://kyoto.hosp.go.jp/html/guide/medicalinfo/ clinical research/expand/gan.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Dr. Yoshiihiro Kawaoka at The Institution of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo for providing clinical research information. The authors also want to acknowledge all medical staff for clinical research at Kyoto University School of Medicine and the National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center. We also appreciate FUNAKOSHI Inc. (Meguro, Tokyo, Japan) and Wakenyaku Inc. (Kyoto, Kyoto, Japan) for effort shipping the tissues obtained from cows and lion.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; European Union Reference Laboratory for Avian Influenza; Alexakis L, Buczkowski H, Ducatez M, Fusaro A, Gonzales JL, Kuiken T, Ståhl K, Staubach C, Svartström O, Terregino C, Willgert K, Melo M, Kohnle L. Avian influenza overview September-December 2024.EFSA J. 2025 Jan 10;23(1):e9204. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2025.9204. eCollection 2025 Jan.

- Food & Beverages: Investigation of Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus in Dairy Cattle. U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2025 March 14. https://www.fda.gov/food/alerts-advisories-safety-information/investigation-avian-influenza-h5n1-virus-dairy-cattle.

- Between 16 March and 14 June 2024, 42 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5) virus detections were reported in domestic (15) and wild (27) birds across 13 countries in Europe. Avian influenza overview March–June 2024, Publication series: Avian influenza overview. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control An agency of the European Union. 2024 Jul 4. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/avian-influenza-overview-march-june-2024.

- Peacock TP, Moncla L, Dudas G, VanInsberghe D, Sukhova K, Lloyd-Smith JO, Worobey M, Lowen AC, Nelson MI. The global H5N1 influenza panzootic in mammals. Nature. 2025 Jan;637(8045):304-313. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08054-z.

- Guan L, Eisfeld AJ, Pattinson D, Gu C, Biswas A, Maemura T, Trifkovic S, Babujee L, Presler R Jr, Dahn R, Halfmann PJ, Barnhardt T, Neumann G, Thompson A, Swinford AK, Dimitrov KM, Poulsen K, Kawaoka Y. Cow’s Milk Containing Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus — Heat Inactivation and Infectivity in Mice Published May 24, 2024 N Engl J Med 2024;391:87-90 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2405495.

- Saied AA, El-Saeed BA. Infectiousness of raw (unpasteurised) milk from influenza H5N1-infected cows beyond the USA. The Lancet Microbe. Online first101107March 18, 2025. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanmic/article/PIIS2666-5247(25)00035-7/fulltext.

- Advancing Animal Health & Welfare in Canada. US Detections of H5N1 in Dairy Cattle.https://animalhealthcanada.ca/.

- World Health Organization. Human infection with avian influenza A(H5) viruses. Avian Influenza Weekly Update Number 983. 2025. January 31. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/wpro---documents/emergency/surveillance/avian-influenza/ai_20250131.pdf.

- Pan Arica and World Health Organization. Epidemiological Update Avian Influenza A(H5N1) in the Americas Region. 2025 January 24. https://www.paho.org/sites/default/files/2025-01/2025-jan-24-phe-epiupdate-avian-influenza-eng-final.pdf.

- Schnirring L. USDA. Topics Avian Influenza (Bird Flu): USDA confirms more avian flu in US dairy cattle and poultry. News brief November 28, 2024. USDA confirms more avian flu in US dairy cattle and poultry | CIDRAP.

- 11. United States Department of Agriculture HPAI in Livestock | Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. 2024. December 24. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-livestock#:~:text=This%20includes%20those%20taken%20by,against%20the%20spread%20of%20H5N1.

- For immediate release: CDC confirms H5N1 Bird Flu Infection in a Child in California. 2024 November 22. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/p1122-h5n1-bird-flu.html.

- Abene S. California Issues Raw Milk Recall After Detection of H5N1 Bird Flu Virus 2024, 26 November 26. https://www.contagionlive.com/view/california-issues-raw-milk-recall-after-detection-of-h5n1-bird-flu-virus.

- Mostafa A, Naguib MM, Nogales A, Barre RS, Stewart JP, García-Sastre A, Martinez-Sobrido L. Avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in dairy cattle: origin, evolution, and cross-species transmission. mBio. 2024 Dec 11;15(12):e0254224. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02542-24.

- Eisfeld AJ, Biswas A, Guan L, Gu C, Maemura T, Trifkovic S, Wang T, Babujee L, Dahn R, Halfmann PJ, Barnhardt T, Neumann G, Suzuki Y, Thompson A, Swinford AK, Dimitrov KM, Poulsen K, Kawaoka Y. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of bovine H5N1 influenza virus. Nature. 2024 Sep;633(8029):426-432. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07766-6.

- 16. Mellis AM, Coyle J, Marshall KE, Frutos AM, Singleton J, Drehoff C, Merced-Morales A, Pagano HP, Alade RO, White EB, Noble EK, Holiday C, Liu F, Jefferson S, Li ZN, Gross FL, Olsen SJ, Dugan VG, Reed C, Ellington S, Montoya S, Kohnen A, Stringer G, Alden N, Blank P, Chia D, Bagdasarian N, Herlihy R, Lyon-Callo S, Levine MZ. Serologic Evidence of Recent Infection with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5) Virus Among Dairy Workers — Michigan and Colorado, June–August 2024 Weekly / November 7, 2024 / 73(44);1004–1009 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024 Nov 7;73(44):1004-1009. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7344a3.

- Gu, C.; Maemura, T.; Guan, L.; Eisfeld, A.J.; Biswas, A.; Kiso, M.; Uraki, R.; Ito, M.; Trifkovic, S.; Wang, T.; et al. A human isolate of bovine H5N1 is transmissible and lethal in animal models. Nature, 2024; 636, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg S, Reinhart K, Couture A, Kniss K, Davis CT, Kirby MK, Murray EL, Zhu S, Kraushaar V, Wadford DA, Drehoff C, Kohnen A, Owen M, Morse J, Eckel S, Goswitz J, Turabelidze G, Krager S, Unutzer A, Gonzales ER, Abdul Hamid C, Ellington S, Mellis AM, Budd A, Barnes JR, Biggerstaff M, Jhung MA, Richmond-Crum M, Burns E, Shimabukuro TT, Uyeki TM, Dugan VG, Reed C, Olsen SJ. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Infections in Humans. N Engl J Med. 2025 Feb 27;392(9):843-854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2414610.

- Mahase E. Bird flu: US reports first human death in person infected with H5N1 BMJ 2025; 388 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.r28.

- CDC Newsroom Releases: CDC Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus Infection Reported in a Person in the U.S. CDC’s Risk Assessment for the General Public Remains Low. Monday, 2024 April 1. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/p0401-avian-flu.html.

- Jassem AN, Roberts A, Tyson J, Zlosnik JEA, Russell SL, Caleta JM, Eckbo EJ, Gao R, Chestley T, Grant J, Uyeki TM, Prystajecky NA, Himsworth CG, MacBain E, Ranadheera C, Li L, Hoang LMN, Bastien N, Goldfarb DM. Critical Illness in an Adolescent with Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Infection Published December 31, 2024 N Engl J Med 2025;392:927-929 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2415890.

- Lin TH, Zhu X, Wang S, Zhang D, McBride R, Yu W, Babarinde S, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. A single mutation in bovine influenza H5N1 hemagglutinin switches specificity to human receptors. Science. 2024 Dec 6;386(6726):1128-1134. doi: 10.1126/science.adt0180.

- Lan, J., Ge, J., Yu, J., Shan, S., Zhou, H., Fan, S., Zhang, Q., Shi, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, L., Wang, X. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581: 215-220, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5.

- Bertram S, Glowacka I, Steffen I, Kühl A, Pöhlmann S. Novel insights into proteolytic cleavage of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Rev Med Virol. 2010 Sep;20(5):298-310. doi: 10.1002/rmv.657.

- 25. Shinya K, Ebina M, Yamada S, Ono M, Kasai N, Kawaoka Y. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature. 2006 Mar 23;440(7083):435-6. doi: 10.1038/440435a.

- World Health Organization. Human infection with avian influenza A(H5) viruses. Avian Influenza Weekly Update Number 983. 2025, 31 January. hhttps://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/wpro---documents/emergency/surveillance/avian-influenza/ai_20250131.pdf.

- Alain R, Jean-Philippe D. (June 2021). “Crop protection practices and viral zoonotic risks within a One Health framework”. Science of the Total Environment. 774: 145172. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.774n5172R. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145172.

- Mellis AM, Coyle J, Marshall KE, Frutos AM, Singleton J, Drehoff C, Merced-Morales A, Pagano HP, Alade RO, White EB, Noble EK, Holiday C, Liu F, Jefferson S, Li ZN, Gross FL, Olsen SJ, Dugan VG, Reed C, Ellington S, Montoya S, Kohnen A, Stringer G, Alden N, Blank P, Chia D, Bagdasarian N, Herlihy R, Lyon-Callo S, Levine MZ. Serologic Evidence of Recent Infection with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5) Virus Among Dairy Workers - Michigan and Colorado, June-August 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024 Nov 7;73(44):1004-1009. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7344a3.

- Chiba S, Kiso M, Yamada S, Someya K, Onodera Y, Yamaguchi A, Matsunaga S, Jounai N, Yamayoshi S, Takeshita F, Kawaoka Y. Protective effects of an mRNA vaccine candidate encoding H5HA clade 2.3.4.4b against the newly emerged dairy cattle H5N1 virus. EBioMedicine. 2024 Nov;109:105408. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105408.

- Park J, Fong Legaspi SL, Schwartzman LM, Gygli SM, Sheng ZM, Freeman AD, Matthews LM, Xiao Y, Ramuta MD, Batchenkova NA, Qi L, Rosas LA, Williams SL, Scherler K, Gouzoulis M, Bellayr I, Morens DM, Walters KA, Memoli MJ, Kash JC, Taubenberger JK. An inactivated multivalent influenza A virus vaccine is broadly protective in mice and ferrets. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Jul 13;14(653): eabo2167. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abo2167.

Figure 1.

Expression of the α2.3SA receptor for HPAI/H5N1 and the α2.6SA receptor for human influenza virus in respiratory , mammary gland, and conjunctival tissues obtained from humans and dairy cows. (A) The expression of the HPAI/H5N1 virus receptor α2.3SA (red) and human influenza virus receptor α2.6SA (green) in human respiratory (trachea, bronchioles, and alveoli), mammary gland, and conjunctival tissues. α2.6SA (green) is expressed in all tissues, particularly in the bronchioles and alveoli. However, α2.6SA was weakly expressed in human mammary gland and conjunctival tissues. (B) The expression of α2.3SA (green) and α2.6SA (red) in respiratory (trachea, bronchioles, and alveoli), mammary gland, and conjunctival tissues obtained from dairy cows. α2.6SA (red) is strongly expressed in the mucosal epithelial tissue of the trachea and mammary gland tissue cells. The expression of α2.6SA was not detected in the bronchioles, alveoli, or conjunctiva. MAL I lectin (red) or MAL II lectin (red) is an antagonist of α2.3SA, while SMA is an antagonist of α2.6SA.

Figure 1.

Expression of the α2.3SA receptor for HPAI/H5N1 and the α2.6SA receptor for human influenza virus in respiratory , mammary gland, and conjunctival tissues obtained from humans and dairy cows. (A) The expression of the HPAI/H5N1 virus receptor α2.3SA (red) and human influenza virus receptor α2.6SA (green) in human respiratory (trachea, bronchioles, and alveoli), mammary gland, and conjunctival tissues. α2.6SA (green) is expressed in all tissues, particularly in the bronchioles and alveoli. However, α2.6SA was weakly expressed in human mammary gland and conjunctival tissues. (B) The expression of α2.3SA (green) and α2.6SA (red) in respiratory (trachea, bronchioles, and alveoli), mammary gland, and conjunctival tissues obtained from dairy cows. α2.6SA (red) is strongly expressed in the mucosal epithelial tissue of the trachea and mammary gland tissue cells. The expression of α2.6SA was not detected in the bronchioles, alveoli, or conjunctiva. MAL I lectin (red) or MAL II lectin (red) is an antagonist of α2.3SA, while SMA is an antagonist of α2.6SA.

Figure 2.

Expression of the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 , α2.3SA, and α2.SA6 in respiratory tissues obtained from lions. Many cases have been reported of lions kept in zoos contracting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-SoV-2) infections through zoo keepers with COVID-19. Therefore, we confirmed by immunohistochemical staining the expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is the host’s receptor for SARS-CoV-2, in respiratory tissues (bronchioles and alveoli) obtained from lions. (A) ACE2 (green) was more strongly expressed in the mucosal epithelial cells of the bronchiole tissue than in the alveoli tissue. (B) Bronchioles and alveoli were incubated with SMA lectin (red) for 12 h at 4°C. The tissues were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and observed under a confocal laser microscope. The expression of α2.6SA (red) was observed in the bronchioles and alveoli. Respiratory tissues (bronchioles, alveoli) from lions were also incubated with MAL I lectin (red) or MAL II lectin (red) for 12 h at 4°C. The tissues were then washed with PBS and observed under a confocal laser microscope. α2.3SA (red) was also expressed in the respiratory tissues (bronchioles and alveoli).

Figure 2.

Expression of the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 , α2.3SA, and α2.SA6 in respiratory tissues obtained from lions. Many cases have been reported of lions kept in zoos contracting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-SoV-2) infections through zoo keepers with COVID-19. Therefore, we confirmed by immunohistochemical staining the expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is the host’s receptor for SARS-CoV-2, in respiratory tissues (bronchioles and alveoli) obtained from lions. (A) ACE2 (green) was more strongly expressed in the mucosal epithelial cells of the bronchiole tissue than in the alveoli tissue. (B) Bronchioles and alveoli were incubated with SMA lectin (red) for 12 h at 4°C. The tissues were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and observed under a confocal laser microscope. The expression of α2.6SA (red) was observed in the bronchioles and alveoli. Respiratory tissues (bronchioles, alveoli) from lions were also incubated with MAL I lectin (red) or MAL II lectin (red) for 12 h at 4°C. The tissues were then washed with PBS and observed under a confocal laser microscope. α2.3SA (red) was also expressed in the respiratory tissues (bronchioles and alveoli).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the expression of α2.6SA and α2.3SA among human, dairy cow, and lion tissues. The expression levels of host receptors α2.3SA and α2.6SA were quantified using an image analysis and measurement system (WinROOF2023, Mitani Corporation, Visual System, Fukui-shi, Fukui, Japan). The expression of α2.3SA was higher than that of α2.6SA in all human or dairy cow tissues. Furthermore, the expression of α2.3SA was higher than that of α2.6 in all dairy cow tissues. The expression of α2.6 was higher than that of α2.3SA in the bronchiolar and alveolar tissues obtained from lions.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the expression of α2.6SA and α2.3SA among human, dairy cow, and lion tissues. The expression levels of host receptors α2.3SA and α2.6SA were quantified using an image analysis and measurement system (WinROOF2023, Mitani Corporation, Visual System, Fukui-shi, Fukui, Japan). The expression of α2.3SA was higher than that of α2.6SA in all human or dairy cow tissues. Furthermore, the expression of α2.3SA was higher than that of α2.6 in all dairy cow tissues. The expression of α2.6 was higher than that of α2.3SA in the bronchiolar and alveolar tissues obtained from lions.

Figure 4.

Binding activity of HPAI/H5N1) variants isolated from infected dairy cows to the receptor (α2.6SA) for the human influenza virus. We investigated the binding affinity/recognition of the HPAI /H5N1) variant (called as Bovine H5) isolated from infected dairy cows to the α2.6SA or α2.3SA receptors using an analog of the α2.6SA receptor (LSTc) or an analog of the α2.3SA receptor (LSTa) using In silico analysis. HA of Bovine H5 recognized and binds to an analog of the α2.6SA receptor (LSTc) or an analog of the α2.3SA receptor (LSTa) (A, D). In silico analysis showed strong binding affinity/recognition between the positive control Indonesia H5 and the α2.6SA or α2.3SA receptors (B, E). Indonesia H5 mut. showed somewhat weak binding (affinity) to the α2.6SA receptor or α2.3SA receptor (C, F). To further test the receptor specificity of bovine H5N1, we measured the binding affinity/recognition of recombinant bovine HA to either α2,3- or α2,6-linked sialic acid using established assays with either α2,3- or α2,6-linked sialylglycopolymers. Indonesia-H5N1 virus HA showed a clear preference for α2,6-linked sialic acid, whereas HPAI (H5N1) virus HA also showed a clear preference for α2,3-linked sialic acid (G, H). As expected, the human Isumi-H1N1 virus HA showed no preference for α2,3-linked sialic acid, whereas the HPAI (H5N1) virus HA also showed no preference for α2,6-linked sialic acid (G, H).

Figure 4.

Binding activity of HPAI/H5N1) variants isolated from infected dairy cows to the receptor (α2.6SA) for the human influenza virus. We investigated the binding affinity/recognition of the HPAI /H5N1) variant (called as Bovine H5) isolated from infected dairy cows to the α2.6SA or α2.3SA receptors using an analog of the α2.6SA receptor (LSTc) or an analog of the α2.3SA receptor (LSTa) using In silico analysis. HA of Bovine H5 recognized and binds to an analog of the α2.6SA receptor (LSTc) or an analog of the α2.3SA receptor (LSTa) (A, D). In silico analysis showed strong binding affinity/recognition between the positive control Indonesia H5 and the α2.6SA or α2.3SA receptors (B, E). Indonesia H5 mut. showed somewhat weak binding (affinity) to the α2.6SA receptor or α2.3SA receptor (C, F). To further test the receptor specificity of bovine H5N1, we measured the binding affinity/recognition of recombinant bovine HA to either α2,3- or α2,6-linked sialic acid using established assays with either α2,3- or α2,6-linked sialylglycopolymers. Indonesia-H5N1 virus HA showed a clear preference for α2,6-linked sialic acid, whereas HPAI (H5N1) virus HA also showed a clear preference for α2,3-linked sialic acid (G, H). As expected, the human Isumi-H1N1 virus HA showed no preference for α2,3-linked sialic acid, whereas the HPAI (H5N1) virus HA also showed no preference for α2,6-linked sialic acid (G, H).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the expression of host receptors (α2,3SA) for HPAI/H5N1 viruses in human and dairy cow mammary tissues. (A) Paraffin-embedded human and bovine mammary tissue slices were incubated with recombinant H5N1 HA protein-His Tad for 12 h at 4°C. Then, the labeled anti-His Tag antibody was added to the treated human and bovine mammary tissue slices and incubated for 12 h at 4°C, and nuclear staining was performed with DAPI. We also incubated paraffin-embedded human tissue slices with anti-Avian α2,3 antibody at 4°C for 12 h and then stained the nuclei with DAPI. The stained images of each tissue section were photographed using a confocal laser microscope (LEICA SP8 FALCON). We then saved each image as a file and merged the three image files (DAPI, HA, α2,3SA). (B) The expression levels of host receptor α2,3SA is quantified using an image analysis and measurement system (WinROOF2023, Mitani Corporation, Visual System, Fukui-shi, Fukui, Japan). The quantified expression levels of host receptor α2,3SA is then plotted on a graph.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the expression of host receptors (α2,3SA) for HPAI/H5N1 viruses in human and dairy cow mammary tissues. (A) Paraffin-embedded human and bovine mammary tissue slices were incubated with recombinant H5N1 HA protein-His Tad for 12 h at 4°C. Then, the labeled anti-His Tag antibody was added to the treated human and bovine mammary tissue slices and incubated for 12 h at 4°C, and nuclear staining was performed with DAPI. We also incubated paraffin-embedded human tissue slices with anti-Avian α2,3 antibody at 4°C for 12 h and then stained the nuclei with DAPI. The stained images of each tissue section were photographed using a confocal laser microscope (LEICA SP8 FALCON). We then saved each image as a file and merged the three image files (DAPI, HA, α2,3SA). (B) The expression levels of host receptor α2,3SA is quantified using an image analysis and measurement system (WinROOF2023, Mitani Corporation, Visual System, Fukui-shi, Fukui, Japan). The quantified expression levels of host receptor α2,3SA is then plotted on a graph.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).