Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

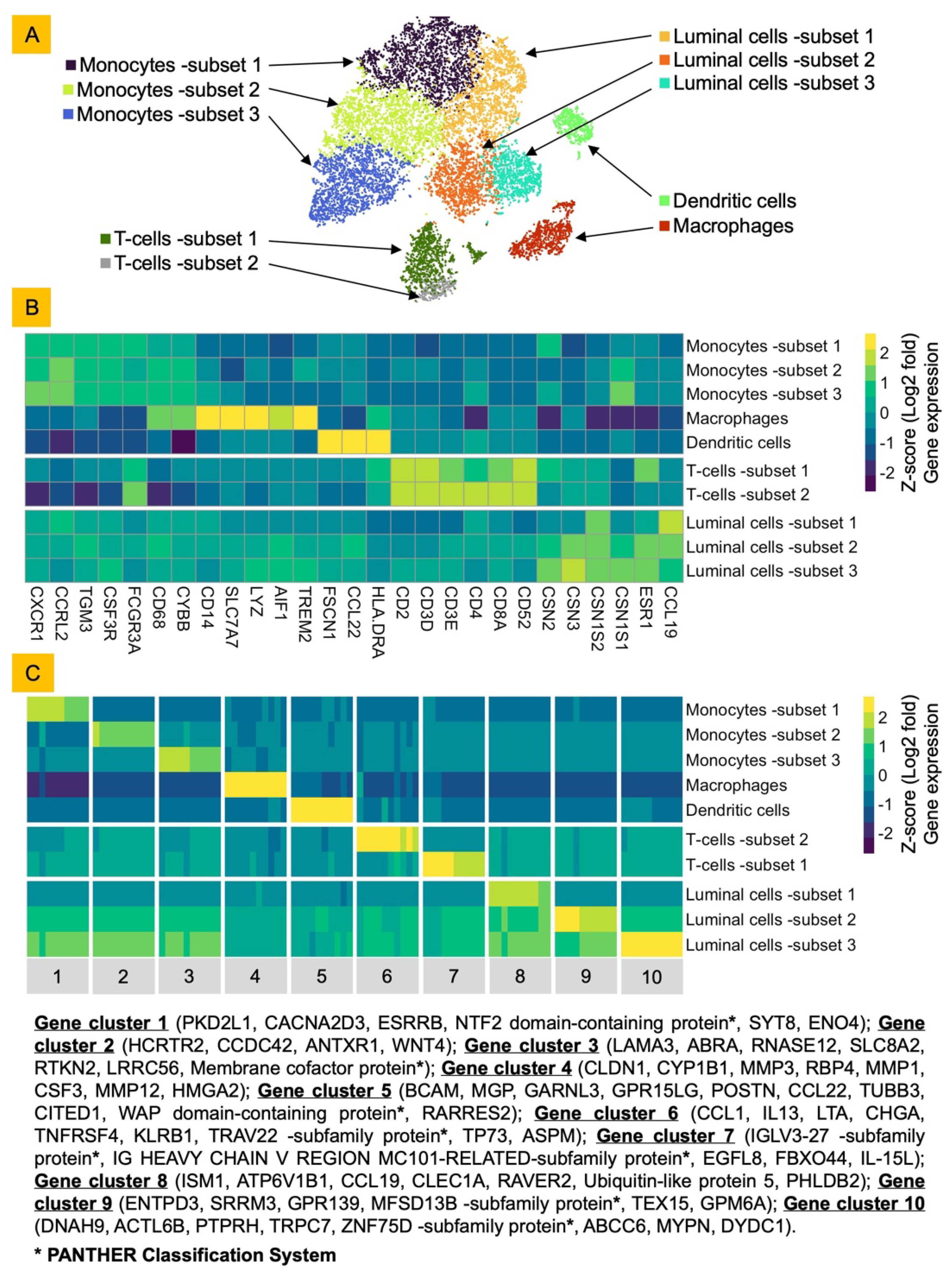

Bovine Milk Somatic Cells (bMSCs) Consist of Diverse Luminal and Immune Cells

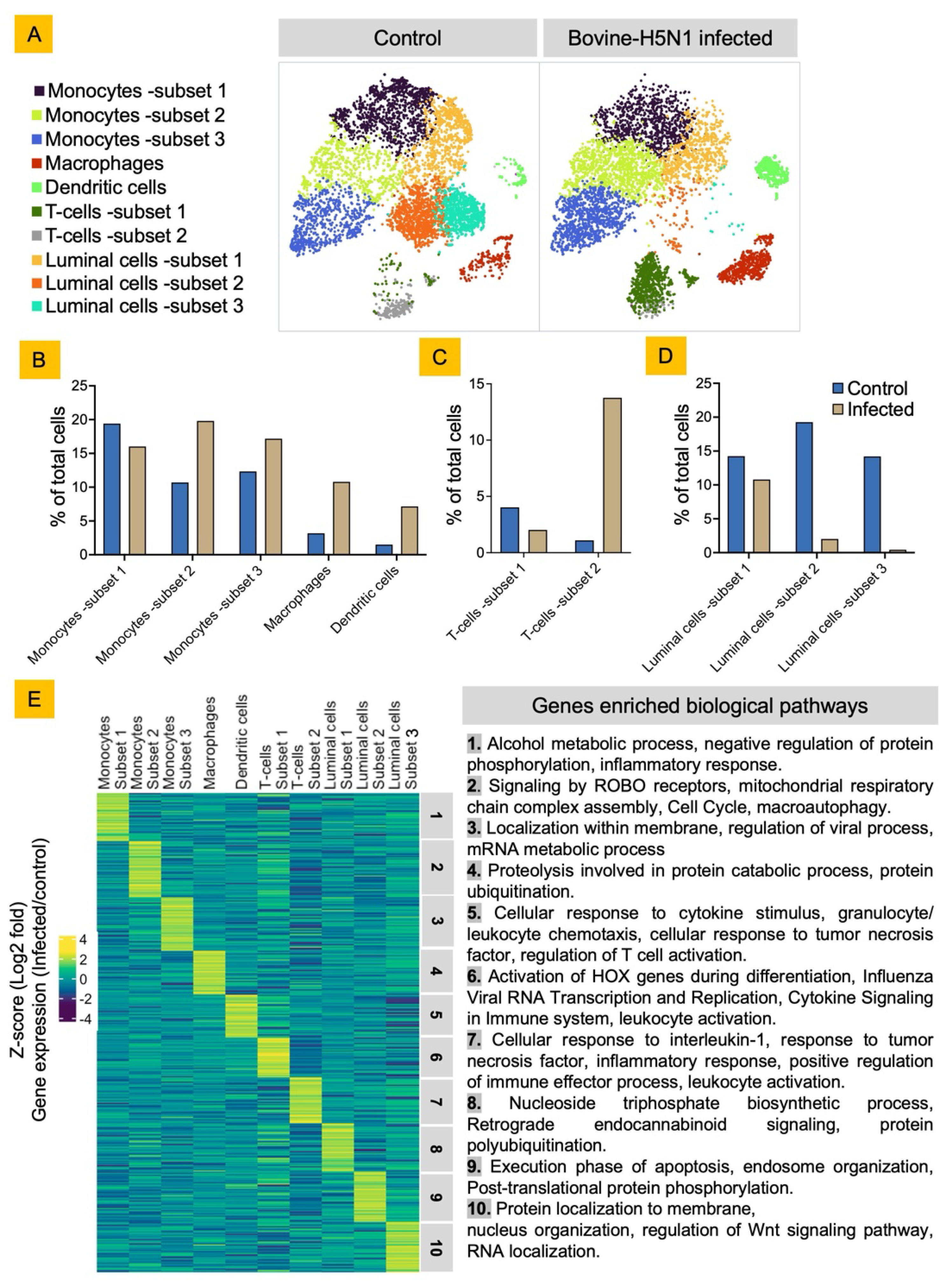

Bovine-H5N1 Infection Alters the bMSCs Cellular Diversity and Their Functional State

Discussion

Material and Methods

Cells and Viruses

Raw Milk Processing and Collection of Bovine Milk Somatic Cells (bMSCs):

bMSCs Infection with HPAIV Bovine-H5N1

Single-Cell Sequencing Using 10X Genomics Platform

Bioinformatics Analysis

RNA Extraction and qPCR for Viral RNA Detection

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgment and Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halwe, N. J.; Cool, K.; Breithaupt, A.; Schön, J.; Trujillo, J. D.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Kwon, T.; Ahrens, A. K.; Britzke, T.; McDowell, C. D.; Piesche, R.; Singh, G.; Pinho dos Reis, V.; Kafle, S.; Pohlmann, A.; Gaudreault, N. N.; Corleis, B.; Ferreyra, F. M.; Carossino, M.; Balasuriya, U. B. R.; Hensley, L.; Morozov, I.; Covaleda, L. M.; Diel, D.; Ulrich, L.; Hoffmann, D.; Beer, M.; Richt, J. A. H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b Dynamics in Experimentally Infected Calves and Cows. Nature 2024, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Caserta, L. C.; Frye, E. A.; Butt, S. L.; Laverack, M.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Covaleda, L. M.; Thompson, A. C.; Koscielny, M. P.; Cronk, B.; Johnson, A.; Kleinhenz, K.; Edwards, E. E.; Gomez, G.; Hitchener, G.; Martins, M.; Kapczynski, D. R.; Suarez, D. L.; Alexander Morris, E. R.; Hensley, T.; Beeby, J. S.; Lejeune, M.; Swinford, A. K.; Elvinger, F.; Dimitrov, K. M.; Diel, D. G. Spillover of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus to Dairy Cattle. Nature 2024, 634 (8034), 669–676. [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. L.; Arruda, B.; Palmer, M. V.; Boggiatto, P.; Davila, K. S.; Buckley, A.; Zanella, G. C.; Snyder, C. A.; Anderson, T. K.; Hutter, C. R.; Nguyen, T.-Q.; Markin, A.; Lantz, K.; Posey, E. A.; Torchetti, M. K.; Robbe-Austerman, S.; Magstadt, D. R.; Gorden, P. J. Dairy Cows Inoculated with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus H5N1. Nature 2024, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Thompson-Crispi, K.; Atalla, H.; Miglior, F.; Mallard, B. A. Bovine Mastitis: Frontiers in Immunogenetics. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 493. [CrossRef]

- Sordillo, L. M.; Streicher, K. L. Mammary Gland Immunity and Mastitis Susceptibility. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2002, 7 (2), 135–146. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Richoux, R.; Perruchot, M.-H.; Boutinaud, M.; Mayol, J.-F.; Gagnaire, V. Flow Cytometry Approach to Quantify the Viability of Milk Somatic Cell Counts after Various Physico-Chemical Treatments. PLoS ONE 2015, 10 (12), e0146071. [CrossRef]

- Cinar, M.; Serbester, U.; Ceyhan, A.; Gorgulu, M. Effect of Somatic Cell Count on Milk Yield and Composition of First and Second Lactation Dairy Cows. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 14 (1), 3646. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G. X. Y.; Terry, J. M.; Belgrader, P.; Ryvkin, P.; Bent, Z. W.; Wilson, R.; Ziraldo, S. B.; Wheeler, T. D.; McDermott, G. P.; Zhu, J.; Gregory, M. T.; Shuga, J.; Montesclaros, L.; Underwood, J. G.; Masquelier, D. A.; Nishimura, S. Y.; Schnall-Levin, M.; Wyatt, P. W.; Hindson, C. M.; Bharadwaj, R.; Wong, A.; Ness, K. D.; Beppu, L. W.; Deeg, H. J.; McFarland, C.; Loeb, K. R.; Valente, W. J.; Ericson, N. G.; Stevens, E. A.; Radich, J. P.; Mikkelsen, T. S.; Hindson, B. J.; Bielas, J. H. Massively Parallel Digital Transcriptional Profiling of Single Cells. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8 (1), 14049. [CrossRef]

- Maaten, L. van der; Hinton, G. Visualizing Data Using T-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9 (86), 2579–2605.

- Karlsson, M.; Zhang, C.; Méar, L.; Zhong, W.; Digre, A.; Katona, B.; Sjöstedt, E.; Butler, L.; Odeberg, J.; Dusart, P.; Edfors, F.; Oksvold, P.; von Feilitzen, K.; Zwahlen, M.; Arif, M.; Altay, O.; Li, X.; Ozcan, M.; Mardinoglu, A.; Fagerberg, L.; Mulder, J.; Luo, Y.; Ponten, F.; Uhlén, M.; Lindskog, C. A Single–Cell Type Transcriptomics Map of Human Tissues. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7 (31), eabh2169. [CrossRef]

- Becker, D.; Weikard, R.; Hadlich, F.; Kühn, C. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Freshly Isolated Bovine Milk Cells and Cultured Primary Mammary Epithelial Cells. Sci. Data 2021, 8 (1), 177. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, P. A.; Levitin, H. M.; Miron, M.; Snyder, M. E.; Senda, T.; Yuan, J.; Cheng, Y. L.; Bush, E. C.; Dogra, P.; Thapa, P.; Farber, D. L.; Sims, P. A. Single-Cell Transcriptomics of Human T Cells Reveals Tissue and Activation Signatures in Health and Disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 4706. [CrossRef]

- Zorc, M.; Dolinar, M.; Dovč, P. A Single-Cell Transcriptome of Bovine Milk Somatic Cells. Genes 2024, 15 (3), 349. [CrossRef]

- Van den Bossche, J.; Laoui, D.; Morias, Y.; Movahedi, K.; Raes, G.; De Baetselier, P.; Van Ginderachter, J. A. Claudin-1, Claudin-2 and Claudin-11 Genes Differentially Associate with Distinct Types of Anti-Inflammatory Macrophages In Vitro and with Parasite- and Tumour-Elicited Macrophages In Vivo. Scand. J. Immunol. 2012, 75 (6), 588–598. [CrossRef]

- Šmerdová, L.; Svobodová, J.; Kabátková, M.; Kohoutek, J.; Blažek, D.; Machala, M.; Vondráček, J. Upregulation of CYP1B1 Expression by Inflammatory Cytokines Is Mediated by the P38 MAP Kinase Signal Transduction Pathway. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35 (11), 2534–2543. [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Bing, C. Macrophage-Induced Expression and Release of Matrix Metalloproteinase 1 and 3 by Human Preadipocytes Is Mediated by IL-1β via Activation of MAPK Signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 226 (11), 2869–2880. [CrossRef]

- Broch, M.; Ramírez, R.; Auguet, M. T.; Alcaide, M. J.; Aguilar, C.; Garcia-España, A.; Richart, C. Macrophages Are Novel Sites of Expression and Regulation of Retinol Binding Protein-4 (RBP4). Physiol. Res. 2010, 59 (2), 299–303. [CrossRef]

- Hollmén, M.; Karaman, S.; Schwager, S.; Lisibach, A.; Christiansen, A. J.; Maksimow, M.; Varga, Z.; Jalkanen, S.; Detmar, M. G-CSF Regulates Macrophage Phenotype and Associates with Poor Overall Survival in Human Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Oncoimmunology 2015, 5 (3), e1115177. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Wu, J. HMGA2 Facilitates Colorectal Cancer Progression via STAT3-Mediated Tumor-Associated Macrophage Recruitment. Theranostics 2022, 12 (2), 963–975. [CrossRef]

- Aristorena, M.; Gallardo-Vara, E.; Vicen, M.; de Las Casas-Engel, M.; Ojeda-Fernandez, L.; Nieto, C.; Blanco, F. J.; Valbuena-Diez, A. C.; Botella, L. M.; Nachtigal, P.; Corbi, A. L.; Colmenares, M.; Bernabeu, C. MMP-12, Secreted by Pro-Inflammatory Macrophages, Targets Endoglin in Human Macrophages and Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20 (12), 3107. [CrossRef]

- RARRES2 retinoic acid receptor responder 2 [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/5919 (accessed 2024-10-15).

- Kokubo, K.; Onodera, A.; Kiuchi, M.; Tsuji, K.; Hirahara, K.; Nakayama, T. Conventional and Pathogenic Th2 Cells in Inflammation, Tissue Repair, and Fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, V.; Fu, Y.-X. Lymphotoxin Signaling in Immune Homeostasis and the Control of Microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13 (4), 270–279. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Liang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Liu, L.; Liao, J.; Xu, H.; Zhu, M.; Fu, Y.-X.; Peng, H. T Cell-Derived Lymphotoxin Limits Th1 Response during HSV-1 Infection. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8 (1), 17727. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, T. H.; Wolf, D.; Bodero, M.; Gonzalez, L.; Podack, E. R. T Cell Costimulation by TNFRSF4 and TNFRSF25 in the Context of Vaccination. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 2012, 189 (7), 3311–3318. [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, J. R.; Hühn, M. H.; Swadling, L.; Walker, L. J.; Kurioka, A.; Llibre, A.; Bertoletti, A.; Holländer, G.; Newell, E. W.; Davis, M. M.; Sverremark-Ekström, E.; Powrie, F.; Capone, S.; Folgori, A.; Barnes, E.; Willberg, C. B.; Ussher, J. E.; Klenerman, P. CD161int CD8+ T Cells: A Novel Population of Highly Functional, Memory CD8+ T Cells Enriched within the Gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2016, 9 (2), 401–413. [CrossRef]

- Truong, K.-L.; Schlickeiser, S.; Vogt, K.; Boës, D.; Stanko, K.; Appelt, C.; Streitz, M.; Grütz, G.; Stobutzki, N.; Meisel, C.; Iwert, C.; Tomiuk, S.; Polansky, J. K.; Pascher, A.; Babel, N.; Stervbo, U.; Sauer, I.; Gerlach, U.; Sawitzki, B. Killer-like Receptors and GPR56 Progressive Expression Defines Cytokine Production of Human CD4+ Memory T Cells. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 2263. [CrossRef]

- Cadilha, B. L.; Benmebarek, M.-R.; Dorman, K.; Oner, A.; Lorenzini, T.; Obeck, H.; Vänttinen, M.; Di Pilato, M.; Pruessmann, J. N.; Stoiber, S.; Huynh, D.; Märkl, F.; Seifert, M.; Manske, K.; Suarez-Gosalvez, J.; Zeng, Y.; Lesch, S.; Karches, C. H.; Heise, C.; Gottschlich, A.; Thomas, M.; Marr, C.; Zhang, J.; Pandey, D.; Feuchtinger, T.; Subklewe, M.; Mempel, T. R.; Endres, S.; Kobold, S. Combined Tumor-Directed Recruitment and Protection from Immune Suppression Enable CAR T Cell Efficacy in Solid Tumors. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7 (24), eabi5781. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M. D.; Krangel, M. S. The Human Cytokine I-309 Is a Monocyte Chemoattractant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89 (7), 2950–2954. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Finlay, D.; Garcia, G.; Sun, D.; Rantala, J.; Barshop, W.; Hope, J. L.; Gimple, R. C.; Sangfelt, O.; Bradley, L. M.; Wohlschlegel, J.; Rich, J. N.; Spruck, C. FBXO44 Promotes DNA Replication-Coupled Repetitive Element Silencing in Cancer Cells. Cell 2021, 184 (2), 352-369.e23. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Chang, C. J.; Karger, A.; Keller, M.; Pfaff, F.; Wangkahart, E.; Wang, T.; Secombes, C. J.; Kimoto, A.; Furihata, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Fischer, U.; Dijkstra, J. M. Ancient Cytokine Interleukin 15-Like (IL-15L) Induces a Type 2 Immune Response. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-J.; Yoon, T.-D.; Muhammad, I.; Jeong, M.-H.; Lee, J.; Baek, S.-Y.; Kim, B.-S.; Yoon, S. Regulatory Role of Mouse Epidermal Growth Factor-like Protein 8 in Thymic Epithelial Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 425 (2), 250–255. [CrossRef]

- Subhan, F.; Yoon, T.-D.; Choi, H. J.; Muhammad, I.; Lee, J.; Hong, C.; Oh, S.-O.; Baek, S.-Y.; Kim, B.-S.; Yoon, S. Epidermal Growth Factor-like Domain 8 Inhibits the Survival and Proliferation of Mouse Thymocytes. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32 (4), 952–958. [CrossRef]

- Drouin, M.; Saenz, J.; Gauttier, V.; Evrard, B.; Teppaz, G.; Pengam, S.; Mary, C.; Desselle, A.; Thepenier, V.; Wilhelm, E.; Merieau, E.; Ligeron, C.; Girault, I.; Lopez, M.-D.; Fourgeux, C.; Sinha, D.; Baccelli, I.; Moreau, A.; Louvet, C.; Josien, R.; Poschmann, J.; Poirier, N.; Chiffoleau, E. CLEC-1 Is a Death Sensor That Limits Antigen Cross-Presentation by Dendritic Cells and Represents a Target for Cancer Immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8 (46), eabo7621. [CrossRef]

- Makusheva, Y.; Chung, S.-H.; Akitsu, A.; Maeda, N.; Maruhashi, T.; Ye, X.-Q.; Kaifu, T.; Saijo, S.; Sun, H.; Han, W.; Tang, C.; Iwakura, Y. The C-Type Lectin Receptor Clec1A Plays an Important Role in the Development of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Enhancing Antigen Presenting Ability of Dendritic Cells and Inducing Inflammatory Cytokine IL-17. Exp. Anim. 2022, 71 (3), 288–304. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.; Hu, K.; Huang, L.; Lu, M.; Hu, Q. CCL19 and CCR7 Expression, Signaling Pathways, and Adjuvant Functions in Viral Infection and Prevention. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hawkridge, A. M.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, B.; Mangrum, J. B.; Hassan, Z. H.; He, T.; Blat, S.; Guo, C.; Zhou, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.-Y.; Fang, X. Ubiquitin-like Protein 5 Is a Novel Player in the UPR-PERK Arm and ER Stress-Induced Cell Death. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299 (7), 104915. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, V. C.; Chong, Y.-S.; Yoshioka, T.; Ge, R. Isthmin Targets Cell-Surface GRP78 and Triggers Apoptosis via Induction of Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21 (5), 797–810. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, X.; Hu, C.; Teng, T.; Tang, Q.-Z. A Brief Overview about the Adipokine: Isthmin-1. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 939757. [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, B. T.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.-M.; Stemke-Hale, K.; Gilcrease, M. Z.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Lee, J.-S.; Fridlyand, J.; Sahin, A.; Agarwal, R.; Joy, C.; Liu, W.; Stivers, D.; Baggerly, K.; Carey, M.; Lluch, A.; Monteagudo, C.; He, X.; Weigman, V.; Fan, C.; Palazzo, J.; Hortobagyi, G. N.; Nolden, L. K.; Wang, N. J.; Valero, V.; Gray, J. W.; Perou, C. M.; Mills, G. B. Characterization of a Naturally Occurring Breast Cancer Subset Enriched in Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Stem Cell Characteristics. Cancer Res. 2009, 69 (10), 4116–4124. [CrossRef]

- Lee, N. S.; Evgrafov, O. V.; Souaiaia, T.; Bonyad, A.; Herstein, J.; Lee, J. Y.; Kim, J.; Ning, Y.; Sixto, M.; Weitz, A. C.; Lenz, H.-J.; Wang, K.; Knowles, J. A.; Press, M. F.; Salvaterra, P. M.; Shung, K. K.; Chow, R. H. Non-Coding RNAs Derived from an Alternatively Spliced REST Transcript (REST-003) Regulate Breast Cancer Invasiveness. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11207. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, R.; Shao, N.; Cheang, T.; Wang, S. RING1 and YY1 Binding Protein Suppresses Breast Cancer Growth and Metastasis. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49 (6), 2442–2452. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H.; Kotani, T.; Park, J.; Murata, Y.; Okazawa, H.; Ohnishi, H.; Ku, Y.; Matozaki, T. Role of the Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Shp2 in Homeostasis of the Intestinal Epithelium. PLoS ONE 2014, 9 (3), e92904. [CrossRef]

- Fliegauf, M.; Olbrich, H.; Horvath, J.; Wildhaber, J. H.; Zariwala, M. A.; Kennedy, M.; Knowles, M. R.; Omran, H. Mislocalization of DNAH5 and DNAH9 in Respiratory Cells from Patients with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 171 (12), 1343–1349. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qiao, Y.; Di, Q.; Le, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, J.; Zong, S.; Koide, S. S.; Miao, S.; Wang, L. Interaction of SH3P13 and DYDC1 Protein: A Germ Cell Component That Regulates Acrosome Biogenesis during Spermiogenesis. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 88 (9), 509–520. [CrossRef]

- Boutinaud, M.; Herve, L.; Lollivier, V. Mammary Epithelial Cells Isolated from Milk Are a Valuable, Non-Invasive Source of Mammary Transcripts. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 323. [CrossRef]

- Webster, H. H.; Lengi, A. J.; Corl, B. A. Short Communication: Mammary Epithelial Cell Exfoliation Increases as Milk Yield Declines, Lactation Progresses, and Parity Increases. JDS Commun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; García-Bernalt Diego, J.; Warang, P.; Park, S.-C.; Chang, L. A.; Noureddine, M.; Laghlali, G.; Bykov, Y.; Prellberg, M.; Yan, V.; Singh, S.; Pache, L.; Cuadrado-Castano, S.; Webb, B.; García-Sastre, A.; Schotsaert, M. Outcome of SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection Depends on Genetic Background in Female Mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15 (1), 10178. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Warang, P.; García-Bernalt Diego, J.; Chang, L.; Bykov, Y.; Singh, S.; Pache, L.; Cuadrado-Castano, S.; Webb, B.; Garcia-Sastre, A.; Schotsaert, M. Host Immune Responses Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Infection Result in Protection or Pathology during Reinfection Depending on Mouse Genetic Background. Res. Sq. 2023, rs.3.rs-3637405. [CrossRef]

- Charles A Janeway, J.; Travers, P.; Walport, M.; Shlomchik, M. J. Principles of Innate and Adaptive Immunity. In Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition; Garland Science, 2001.

- Ma, W.; Belisle, S. E.; Mosier, D.; Li, X.; Stigger-Rosser, E.; Liu, Q.; Qiao, C.; Elder, J.; Webby, R.; Katze, M. G.; Richt, J. A. 2009 Pandemic H1N1 Influenza Virus Causes Disease and Upregulation of Genes Related to Inflammatory and Immune Responses, Cell Death, and Lipid Metabolism in Pigs. J. Virol. 2011, 85 (22), 11626–11637. [CrossRef]

- Brydon, E. W. A.; Morris, S. J.; Sweet, C. Role of Apoptosis and Cytokines in Influenza Virus Morbidity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29 (4), 837–850. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zuo, X.; Zhang, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Jiang, S.; Wang, F.; Wang, G. The Mechanism behind Influenza Virus Cytokine Storm. Viruses 2021, 13 (7), 1362. [CrossRef]

- Yahia-Cherbal, H.; Rybczynska, M.; Lovecchio, D.; Stephen, T.; Lescale, C.; Placek, K.; Larghero, J.; Rogge, L.; Bianchi, E. NFAT Primes the Human RORC Locus for RORγt Expression in CD4+ T Cells. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 4698. [CrossRef]

- Capone, A.; Volpe, E. Transcriptional Regulators of T Helper 17 Cell Differentiation in Health and Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Egwuagu, C. E. STAT3 in CD4+ T Helper Cell Differentiation and Inflammatory Diseases. Cytokine 2009, 47 (3), 149. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wan, Y. Y. Intricacies of TGF-β Signaling in Treg and Th17 Cell Biology. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20 (9), 1002–1022. [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, J. T.; Sehra, S.; Thieu, V. T.; Yu, Q.; Chang, H.-C.; Stritesky, G. L.; Nguyen, E. T.; Mathur, A. N.; Levy, D. E.; Kaplan, M. H. Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 4 Limits the Development of Adaptive Regulatory T Cells. Immunology 2009, 127 (4), 587. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, F.; Liu, Z.; Bay, A.; Piccirillo, C. A. Deciphering the Developmental Trajectory of Tissue-Resident Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Trujillo, J. D.; McDowell, C. D.; Matias-Ferreyra, F.; Kafle, S.; Kwon, T.; Gaudreault, N. N.; Fitz, I.; Noll, L.; Morozov, I.; Retallick, J.; Richt, J. A. Detection and Characterization of H5N1 HPAIV in Environmental Samples from a Dairy Farm. Virus Genes 2024, 60 (5), 517–527. [CrossRef]

- Kolde, R. Pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps, 2019. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html (accessed 2024-09-14).

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A. H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S. K. Metascape Provides a Biologist-Oriented Resource for the Analysis of Systems-Level Datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 1523. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).