1. Introduction

In recent years, China has faced escalating public health risks posed by tick-borne diseases, particularly those linked to

Haemaphysalis longicornis (Asian longhorned tick). This species serves as a vector for severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), a life-threatening viral disease with a 12–50% fatality rate [

1]. Since its first identification in 2009, SFTS cases have surged, with over 1,500 infections reported annually across Henan, Hubei, Shandong, Anhui, Liaoning, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang provinces [

2]. The expanding geographic range of

H. longicornis—now documented in 441 counties—has been exacerbated by climate warming and increased human encroachment into tick habitats through recreational activities such as hiking and camping [

3,

4]. Concurrently, livestock infestation rates have risen and the distributions have expanded in rural areas, threatening agricultural productivity and amplifying zoonotic transmission risks [

5].

Current tick control strategies heavily rely on chemical acaricides (e.g., cypermethrin) and vegetation management. However, these methods are increasingly challenged by widespread pesticide resistance and environmental contamination [

6,

7]. For instance, resistance ratios to pyrethroids have reached more than 7× in

H. longicornis populations in South Korea, drastically reducing efficacy [

6]. Integrated pest management (IPM) approaches, though promising, remain underutilized in China due to logistical complexities and limited public awareness [

8,

9]. Moreover, personal protective measures, such as protective clothing, are impractical for communities in endemic regions, where socioeconomic factors limit access to preventative tools.

Tick repellents represent a critical yet underexplored solution to mitigate human-tick contact. DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide), the "gold standard" repellent, has demonstrated >90% efficacy against

Amblyomma americanum and

Ixodes scapularis ticks in controlled studies [

10]. However, the performance of commercial DEET formulations against

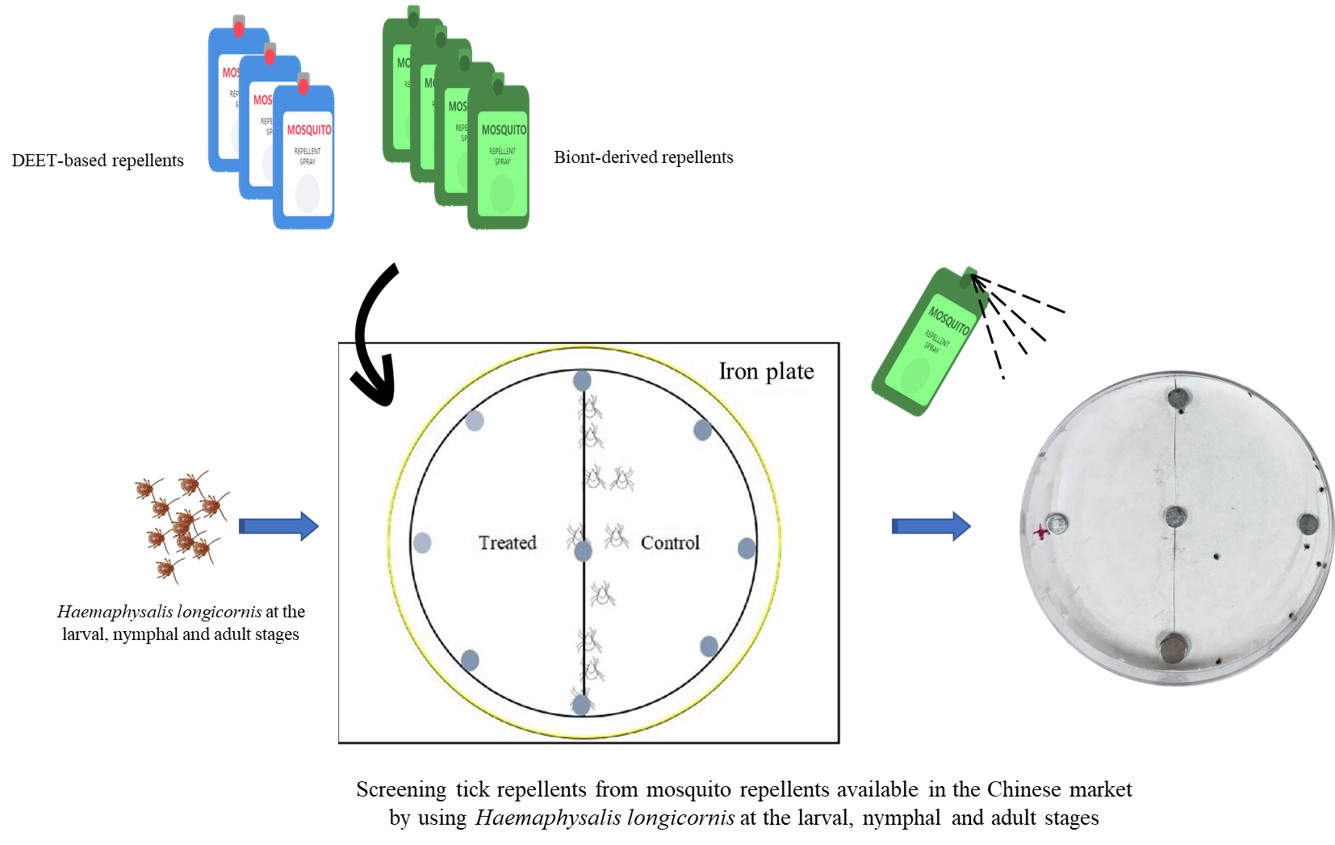

H. longicornis—especially across its larval, nymphal, and adult stages—remains poorly characterized in China. This study evaluates four DEET-based (5–10% DEET concentrations) and four biont-based repellents available on the Chinese market to determine their hourly repellency rates against

H. longicornis under controlled laboratory conditions. Our goal is to identify accessible, cost-effective products that balance efficacy with user safety, addressing gaps in practical tick bite prevention strategies for at-risk populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tick Maintenance

Unfed H. longicornis (15–60 days old) were obtained from a laboratory colony maintained under controlled conditions (27 ± 1°C, >80% relative humidity, 12:12 light-dark cycle). Ticks were reared on Kunming mice using a feeding apparatus glued to the shaved dorsum. Ethical approval for animal use was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Test Compounds

In September 2024, we purchased several products for mosquito repellents. Four widely available DEET-based repellents and four commonly used biont-derived repellents were included in the study (

Table 1). The concentrations of DEET varied from 5 to 10 percent that represented the range of commonly purchased repellents in China. The biological repellents were made up of plant and animal-based extracts, including geranium extract, clove leaf oil, snake bile extract, citronella grass oil, East Indian lemongrass oil, and lemongrass oil (

Table 1).

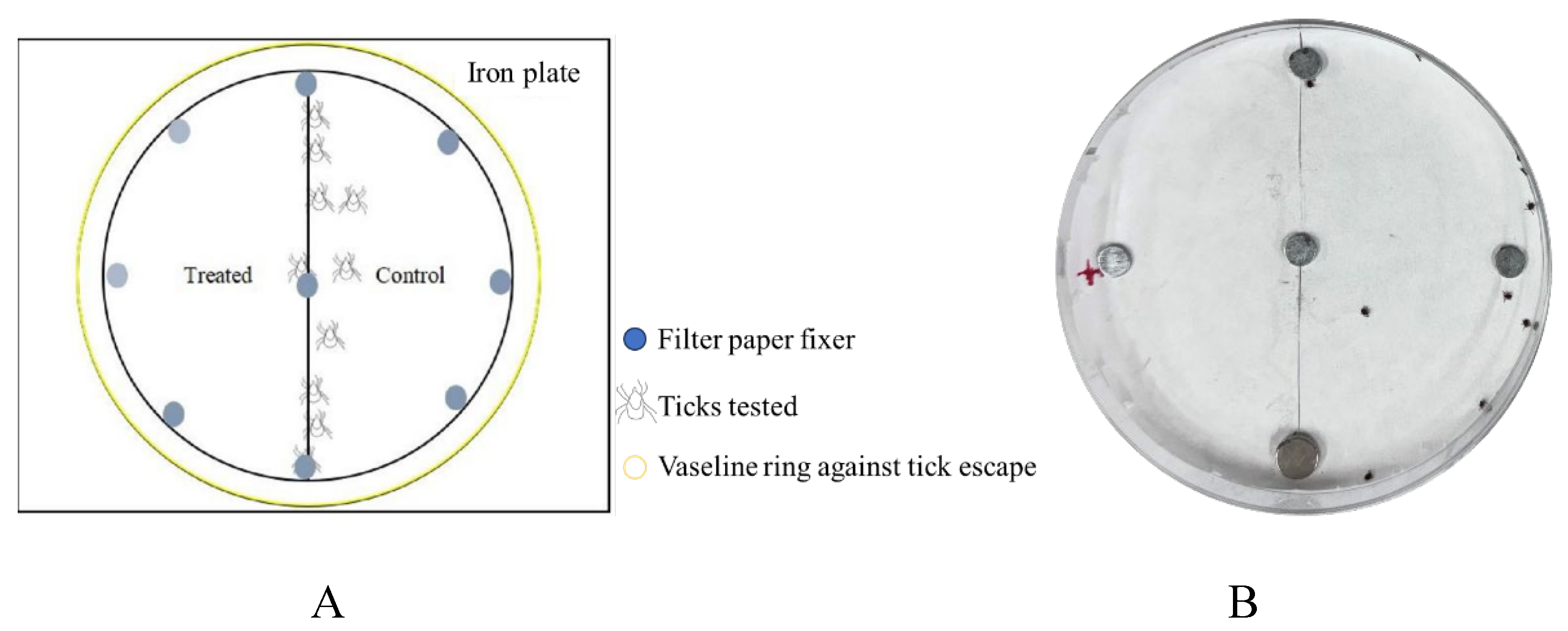

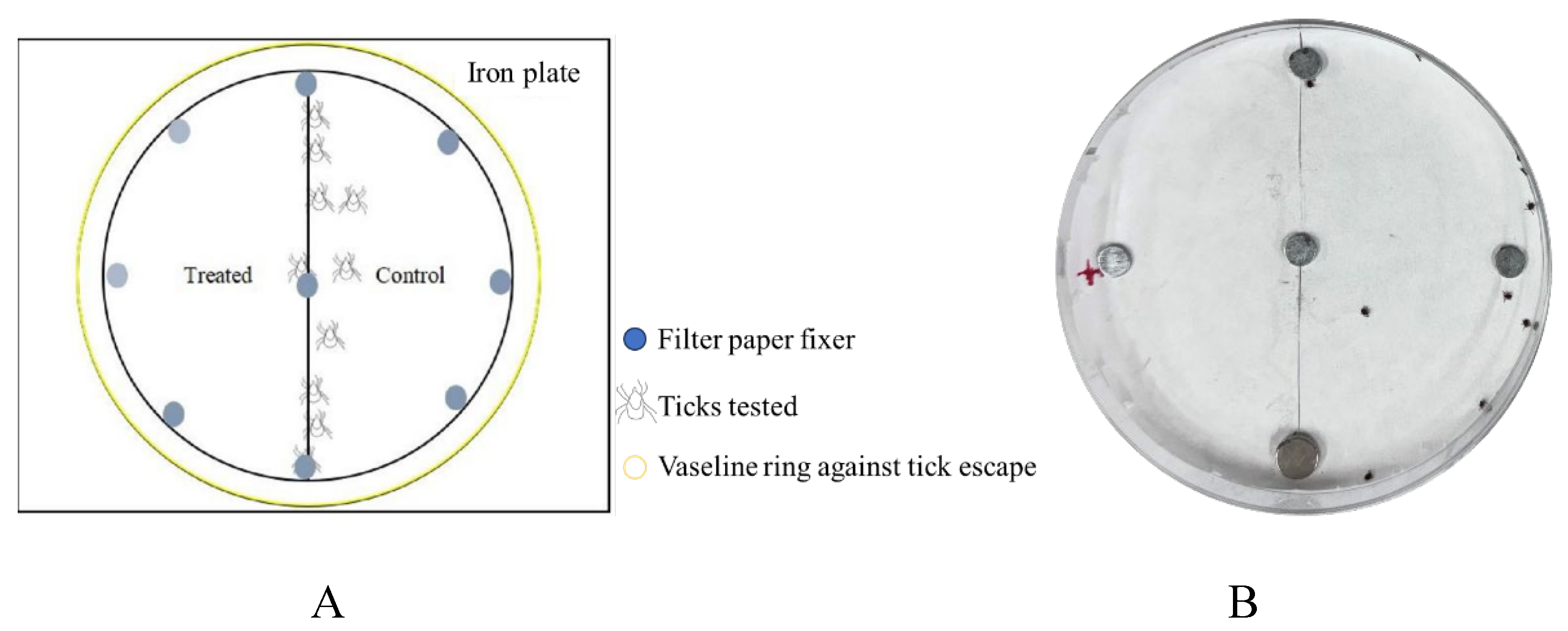

2.3. Testing Methods

The repellent activity was determined using a choice assay. In the experimental group, a 9 cm diameter filter paper was bisected into two halves. One half was soaked with 250 μL of the commercial repellent being tested, while the other half was treated with 250 μL of 100% ethanol. A pipette was used to measure and transfer the respective liquids to soak each half of the filter paper, with three replicates per group. Simultaneously, a negative control group and a positive control group were established: the negative control used 250 μL of 100% ethanol in place of the commercial repellent, and the positive control used 250 μL of 10% DEET instead of the commercial repellent. After air-drying the filter papers, they were placed in the lid of a Petri dish. The dish lid was aligned with an iron plate, and the filter papers were secured to the paper using magnets. Finally, a ring of medical-grade Vaseline was applied to the edge of the Petri dish lid to prevent ticks from escaping. Ticks (20 larvae, 10 nymphs, or 5 adults) were placed in the central position between the treated and control filter papers to initiate the repellency test. The experiment lasted for 1 hour, with data recorded every 10 minutes. For CaliforniaBaby repellent testing, the experiment was conducted over a 6-hour period. Observations were performed not only during the first hour (as per the standard protocol for the commercial repellents) but also at the 2nd, 4th, and 6th hours. After each observation, the ticks were carefully returned to the central position to reset the timer.

H. longicornis evaluated in filter papers impregnated with the repellent commodities. A, Schematic diagram for the evaluation of tick repellent; B, ticks were introduced in filter papers. The right side represented filter paper treated with the repellent, the left side with absolute alcohol. Obviously, ticks aggregated on the right side. Photo by Weiqing Zheng.

2.4. Data Treatment and Statistical Analysis

Percent repellency was calculated using the given formula: repellency (%) =(C-T)/C*100%.

where C represents the number of mosquitoes landing on the negative control and T represents the number of mosquitoes landing on the tested repellent.

The adjusted repellency was calculated with the below formula: Ra=(Rn-Rc)/(1-Rc).

Where Ra is the adjusted repellency of a product, Rn represents the repellency of the product, and Rc is the repellency of the negative control set.

Unless indicated, all experiments in this study were performed with three biological replicates. The results are presented as mean values ± standard deviation. The statistical analysis was carried out with Chi square test.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The experimental results across larval, nymphal, and adult developmental stages clearly demonstrate varying sensitivities to repellents within the same tick species. Notably, nymphs exhibited the highest sensitivity to repellents. Similar conclusions were reported by Kulma et al., who observed that

Ixodes ricinus nymphs showed significantly greater sensitivity to DEET than adult females in

in vitro assays [

11].

In larval experiments, partial “swaying” gait patterns were observed in the DEET-positive control group after larvae entered DEET-treated zones. This aligns with findings by Koloski et al., who documented uncoordinated movement and convulsive behaviors in

Dermacentor variabilis exposed to DEET [

12]. Further evidence from Koloski et al. indicated a rapid, marked reduction in acetylcholinesterase gene transcription levels in DEET-exposed

Dermacentor variabilis, suggesting a potential mechanism underlying the observed gait abnormalities [

13].

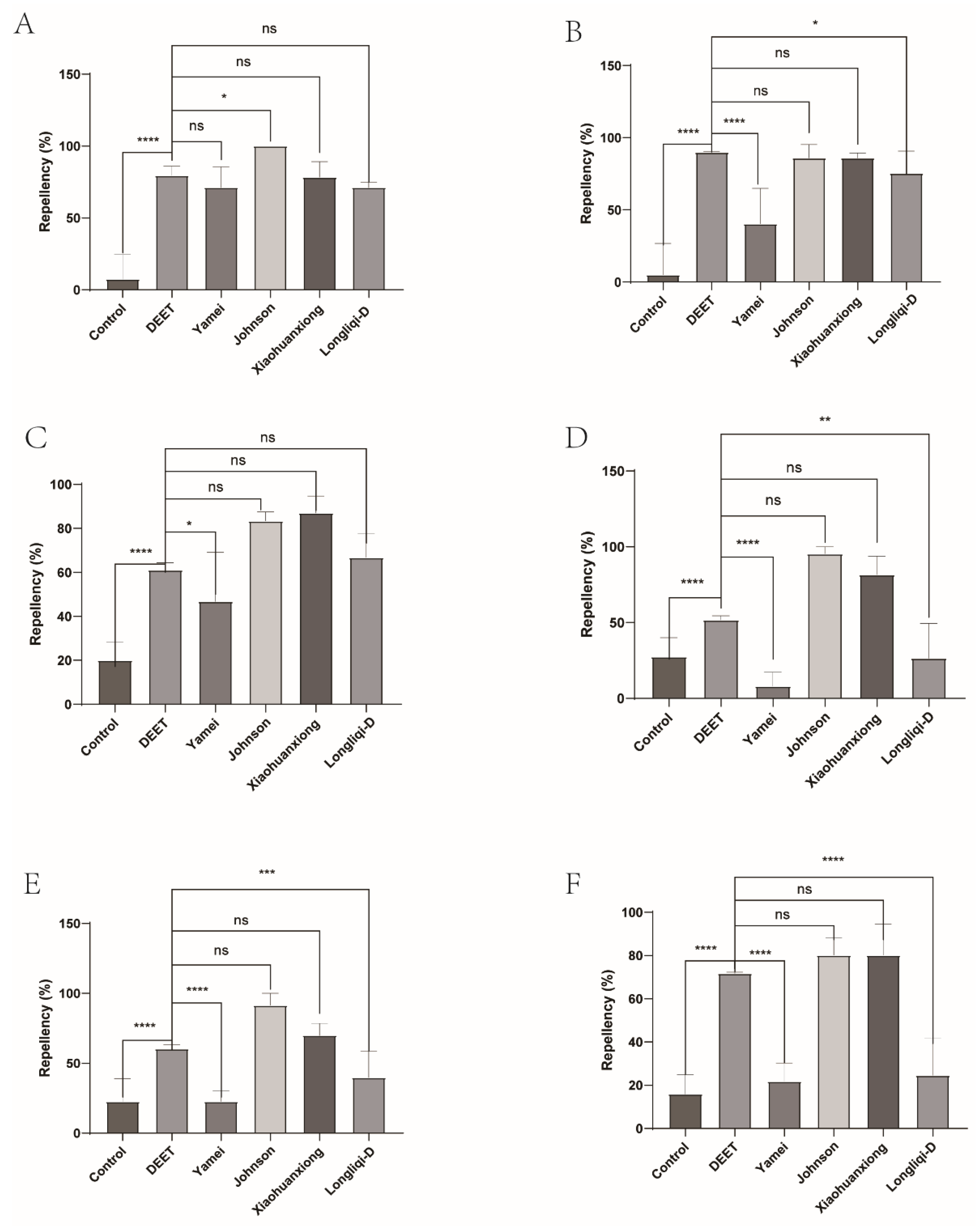

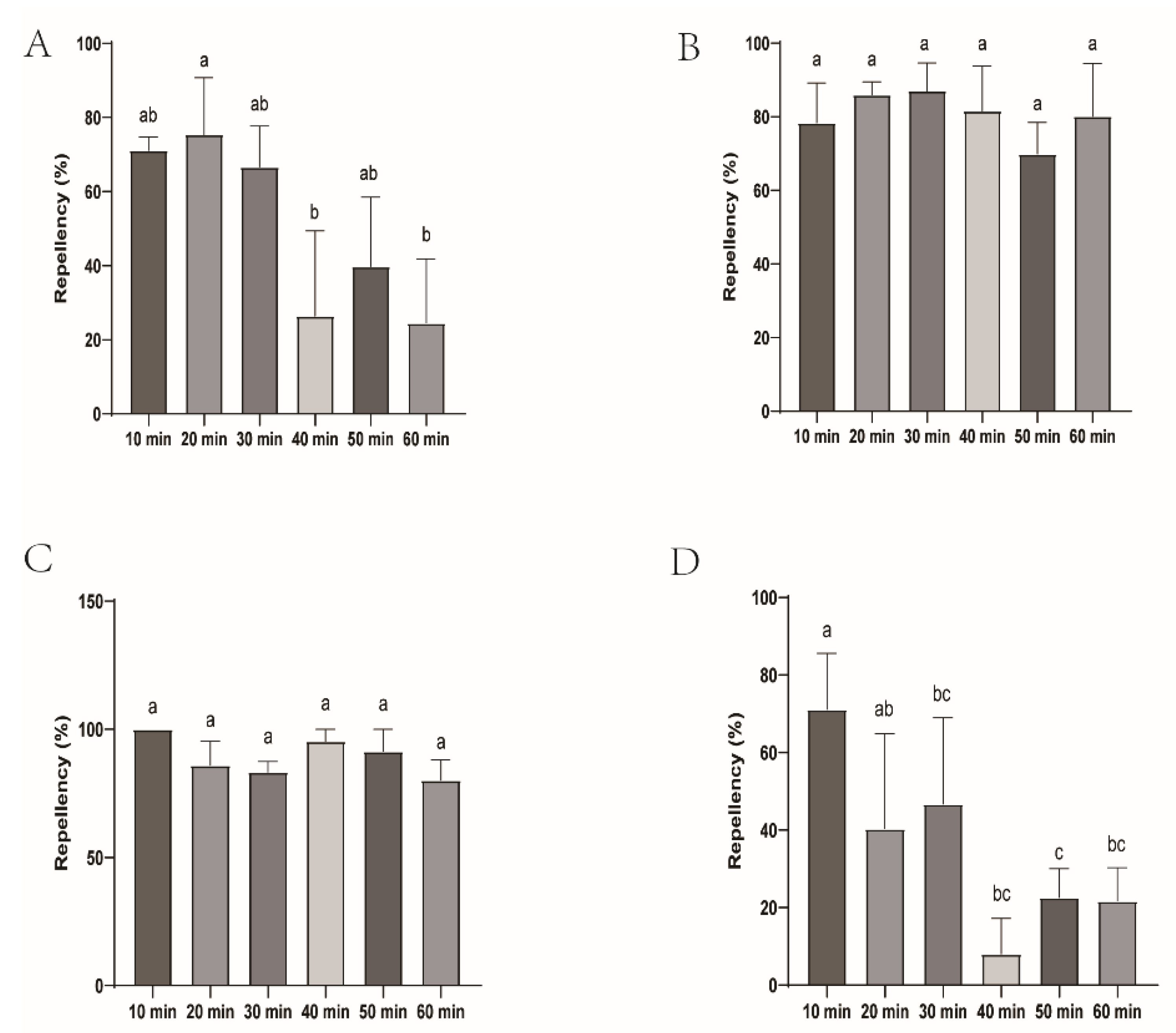

This study evaluated the repellent efficacy of four commercial DEET-based mosquito repellents and four biont-derived formulations against ticks. All products demonstrated strong repellent activity, particularly against nymphs and adults, with performance comparable to DEET. These findings suggest that mosquito repellents may also serve as effective tick repellents for nymphs and adults, though their efficacy against larvae remains suboptimal. Therefore, assessing larval repellency is critical for achieving robust field protection. Interestingly, DEET efficacy did not strictly correlate with concentration; for example, Johnson’s 7% DEET formulation outperformed Yamei’s 10% DEET product. This discrepancy may stem from differences in manufacturing processes or auxiliary ingredients, emphasizing the importance of optimizing production techniques and formulations to enhance active ingredient performance.

Biont-derived repellents, valued for their environmental compatibility and low human toxicity, are a vital complement to synthetic alternatives. Market analysis of purported biont-based products revealed that certain formulations (e.g., CaliforniaBaby) exhibited nymphal and adult tick repellency equivalent to DEET over 6 hours. However, some products labeled as “biont-derived” were found to contain DEET as the primary active ingredient, lacking detectable bioactive phytochemicals. Others, free of synthetic additives, contained repellent-active biont metabolites such as lemongrass essential oil (

Cymbopogon citratus). Thorsell et al. identified lemongrass oil as the most effective botanical repellent against

Ixodes ricinus, maintaining strong activity for 8 hours [

14]. Agwunobi et al. further reported that immersion of

H. longicornis in 40 mg/mL lemongrass oil induced cuticular fissures, Haller’s organ damage, secretory obstruction of spiracles, and midgut contraction within 5 minutes, indicating intense irritancy [

15]. This irritant effect may contribute to repellency, though mechanistic details require further investigation.

This study demonstrates that commercially available DEET-based and select biont-derived mosquito repellents exhibit significant repellent activity against H. longicornis, supporting their repurposing for tick bite prevention. The key findings reveal that ticks showed the high repellent sensitivity to DEET-based repellents, with Johnson’s 7% DEET achieving near-complete repellency. Some of biont-derived mosquito repellents also demonstrated good repellency to ticks and CaliforniaBaby matched DEET’s 6-hour repellency, indicating its utility in prolonged protection against ticks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and Q.X.; Methodology, W.Z.; Software, W.Z., Y.Z., Q.W., J.H., and X.Y.; Validation, W.Z. and Q.X.; Formal Analysis, W.Z., Y.Z. and Q.W.; Investigation, Y.Z., Q.W., J.F., Y.W., S.F., J.H., and X.Y.; Resources, W.Z.; Data Curation, Y.Z., Q.W., J.H., and X.Y.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, W.Z.; Writing – Review & Editing, Q.X.; Visualization, W.Z.; Supervision, Q.X.; Project Administration, Q.X.; Funding Acquisition, W.Z.

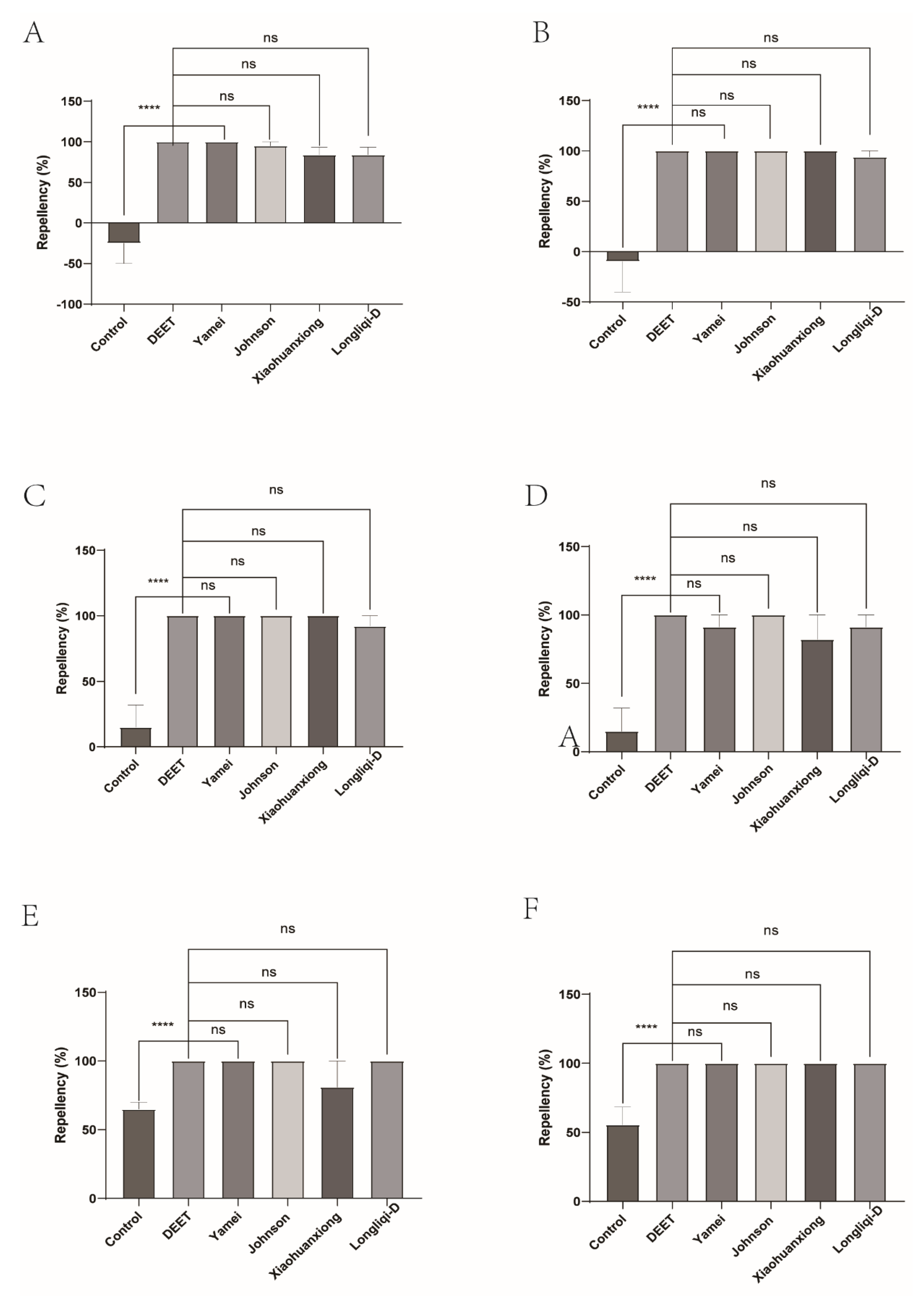

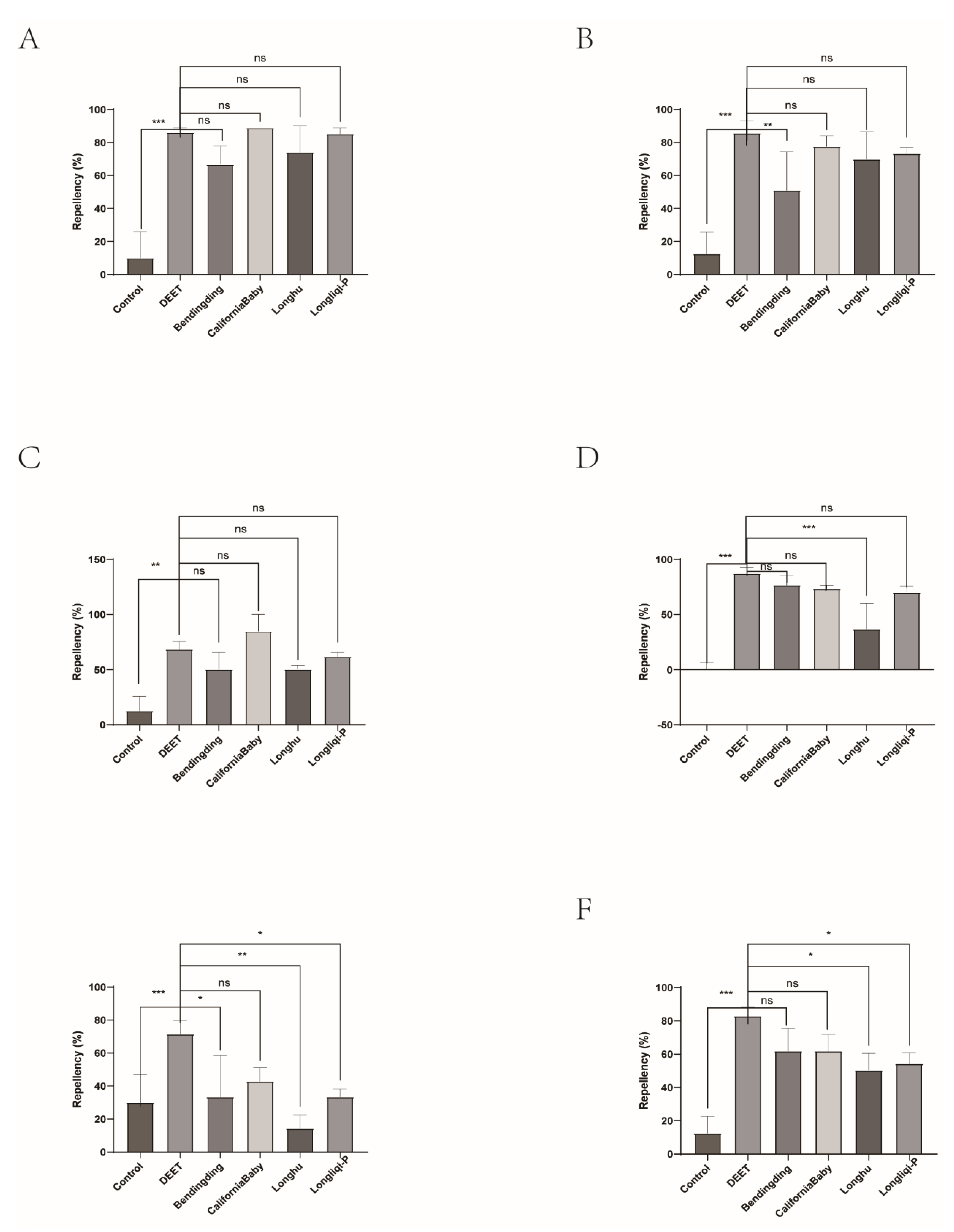

Figure 1.

The effect of four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents against H. longicornis larvae. Note: A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment. ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; the same applied to the following.

Figure 1.

The effect of four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents against H. longicornis larvae. Note: A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment. ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; the same applied to the following.

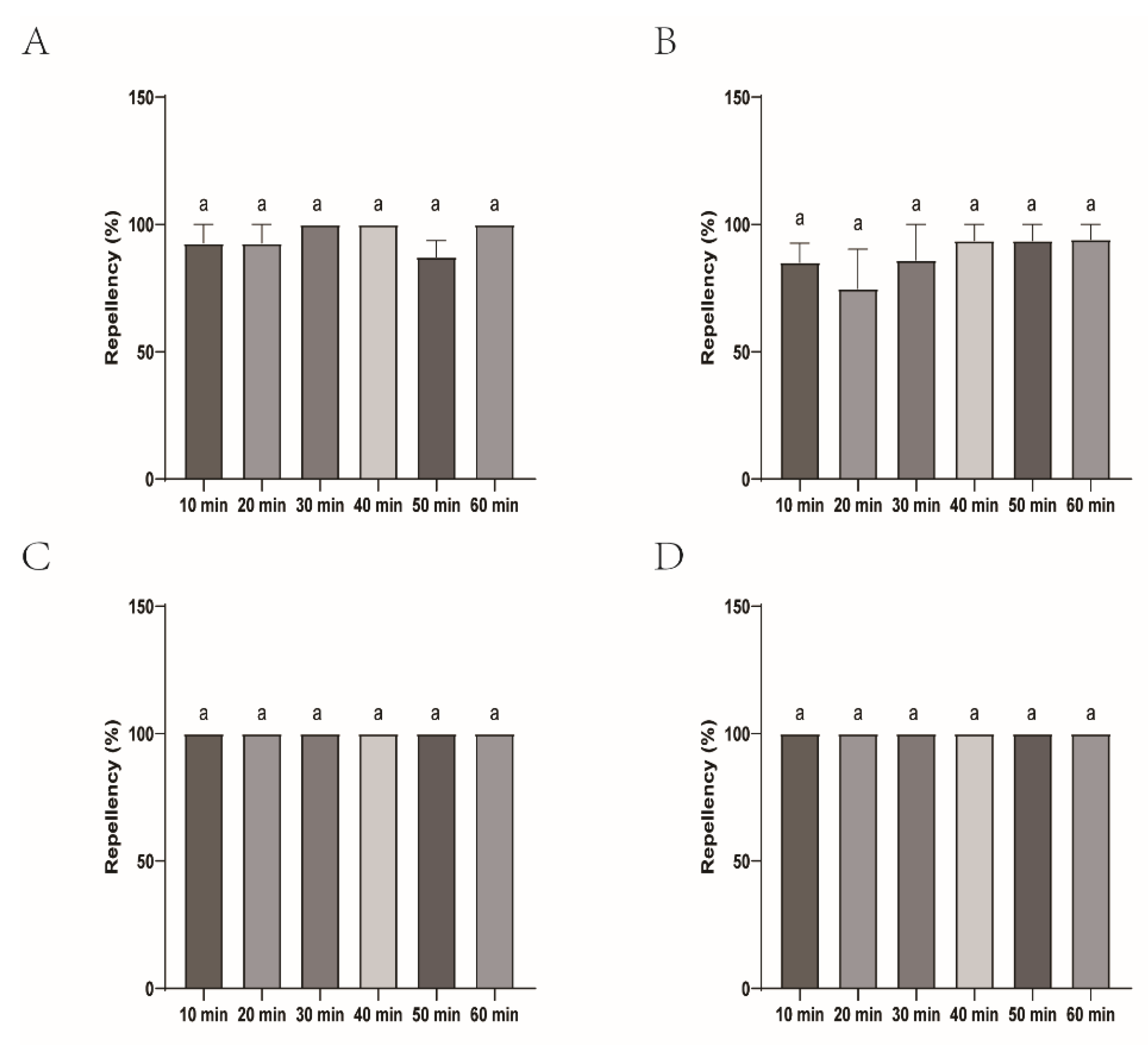

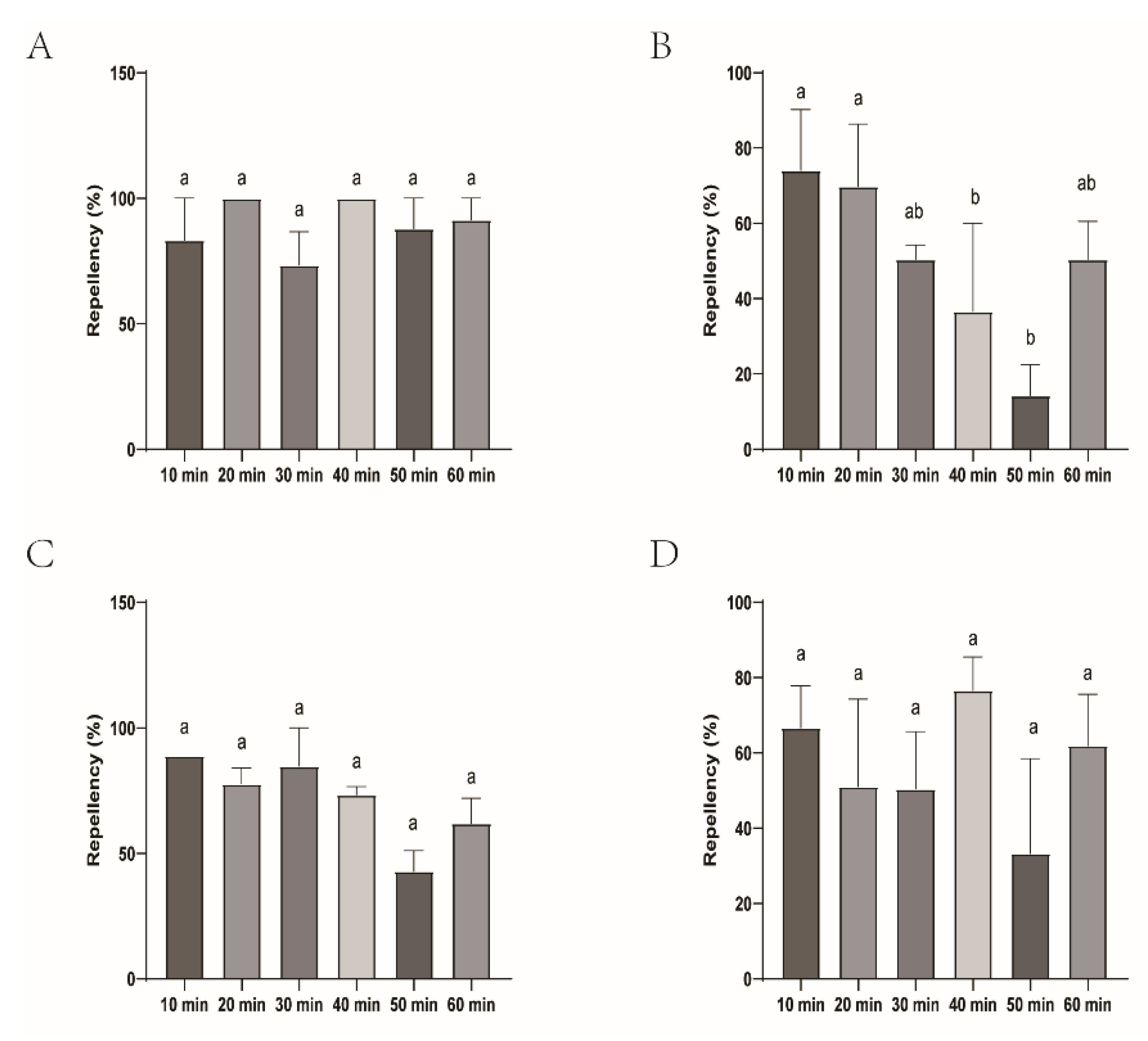

Figure 2.

Repellency of H. longicornis larvae over time after exposure to four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents. Note: A, Longliqi-D; B, Xiaohuanxiong; C, Johnson; D, Yamei. Different letters above the bars in the histogram indicate statistically significant differences, and hereinafter the same.

Figure 2.

Repellency of H. longicornis larvae over time after exposure to four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents. Note: A, Longliqi-D; B, Xiaohuanxiong; C, Johnson; D, Yamei. Different letters above the bars in the histogram indicate statistically significant differences, and hereinafter the same.

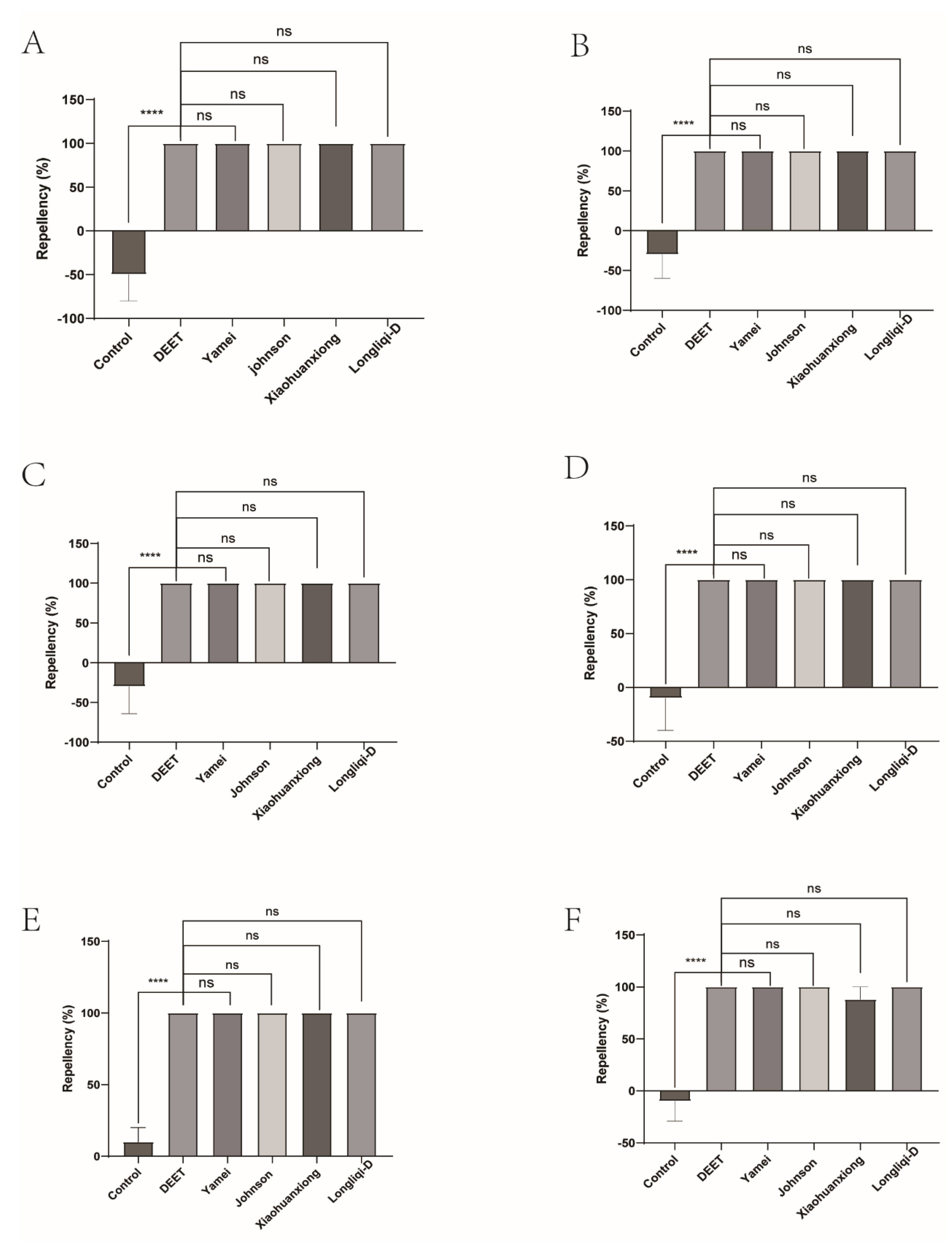

Figure 3.

The effect of four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents against H. longicornis nymphs. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

Figure 3.

The effect of four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents against H. longicornis nymphs. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

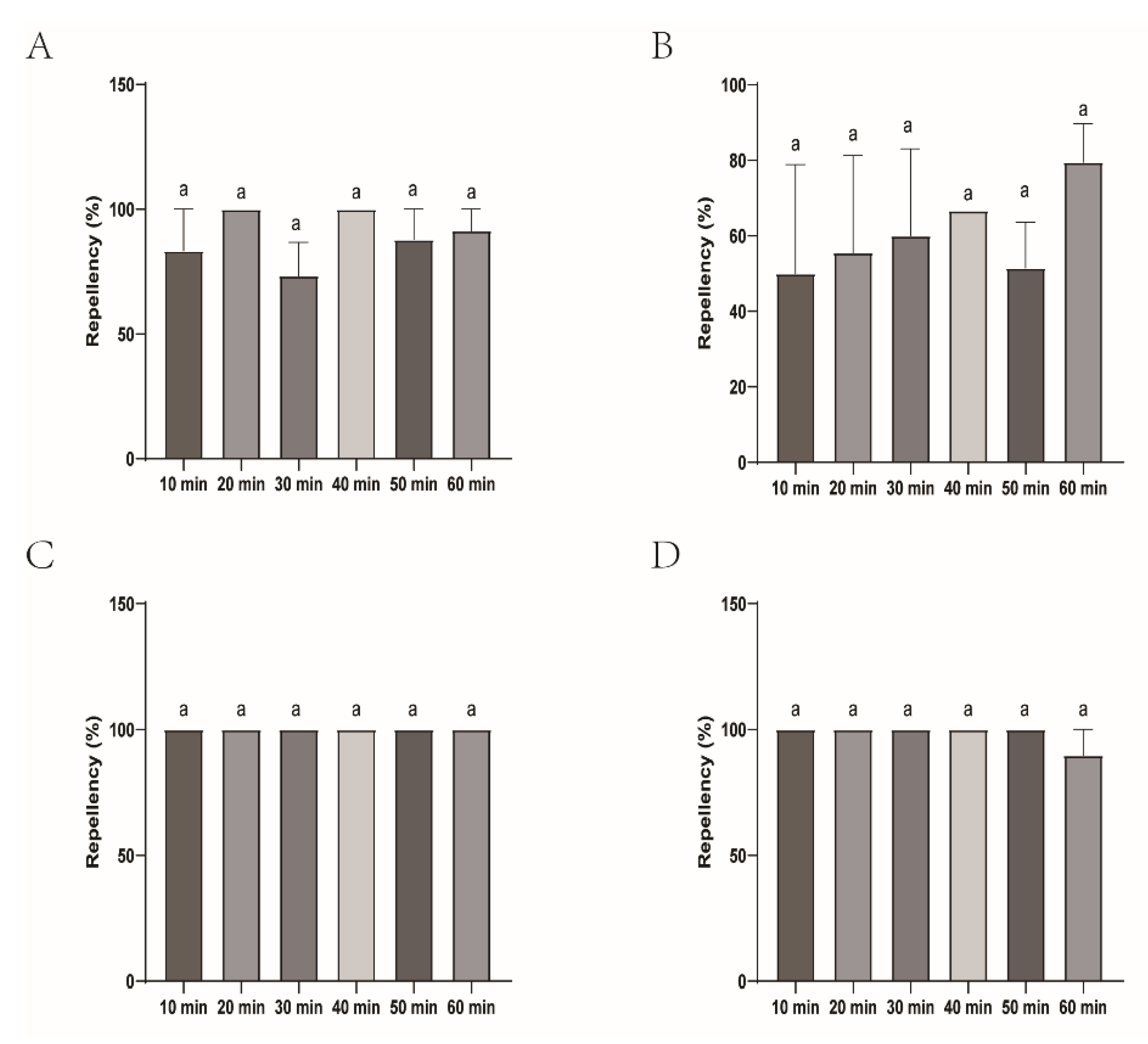

Figure 4.

Repellency of H. longicornis nymphs over time after exposure to four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-D; B, Xiaohuanxiong; C, Johnson; D, Yamei.

Figure 4.

Repellency of H. longicornis nymphs over time after exposure to four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-D; B, Xiaohuanxiong; C, Johnson; D, Yamei.

Figure 5.

The effect of four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents against H. longicornis females. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

Figure 5.

The effect of four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents against H. longicornis females. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

Figure 6.

Repellency of H. longicornis females over time after exposure to four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-D; B, Xiaohuanxiong; C, Johnson; D, Yamei.

Figure 6.

Repellency of H. longicornis females over time after exposure to four commercial DEET-solved mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-D; B, Xiaohuanxiong; C, Johnson; D, Yamei.

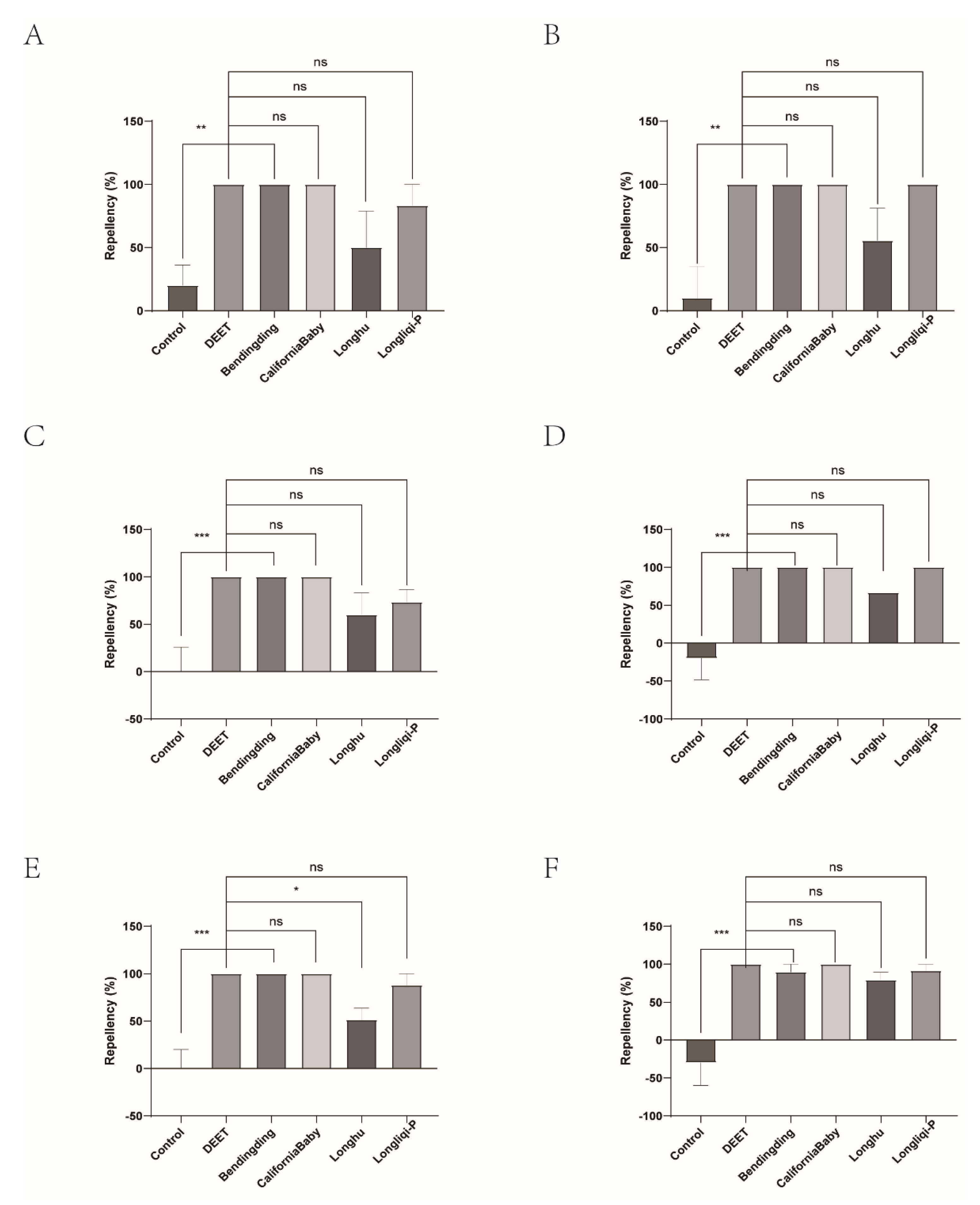

Figure 7.

The effect of the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents against H. longicornis larvae. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

Figure 7.

The effect of the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents against H. longicornis larvae. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

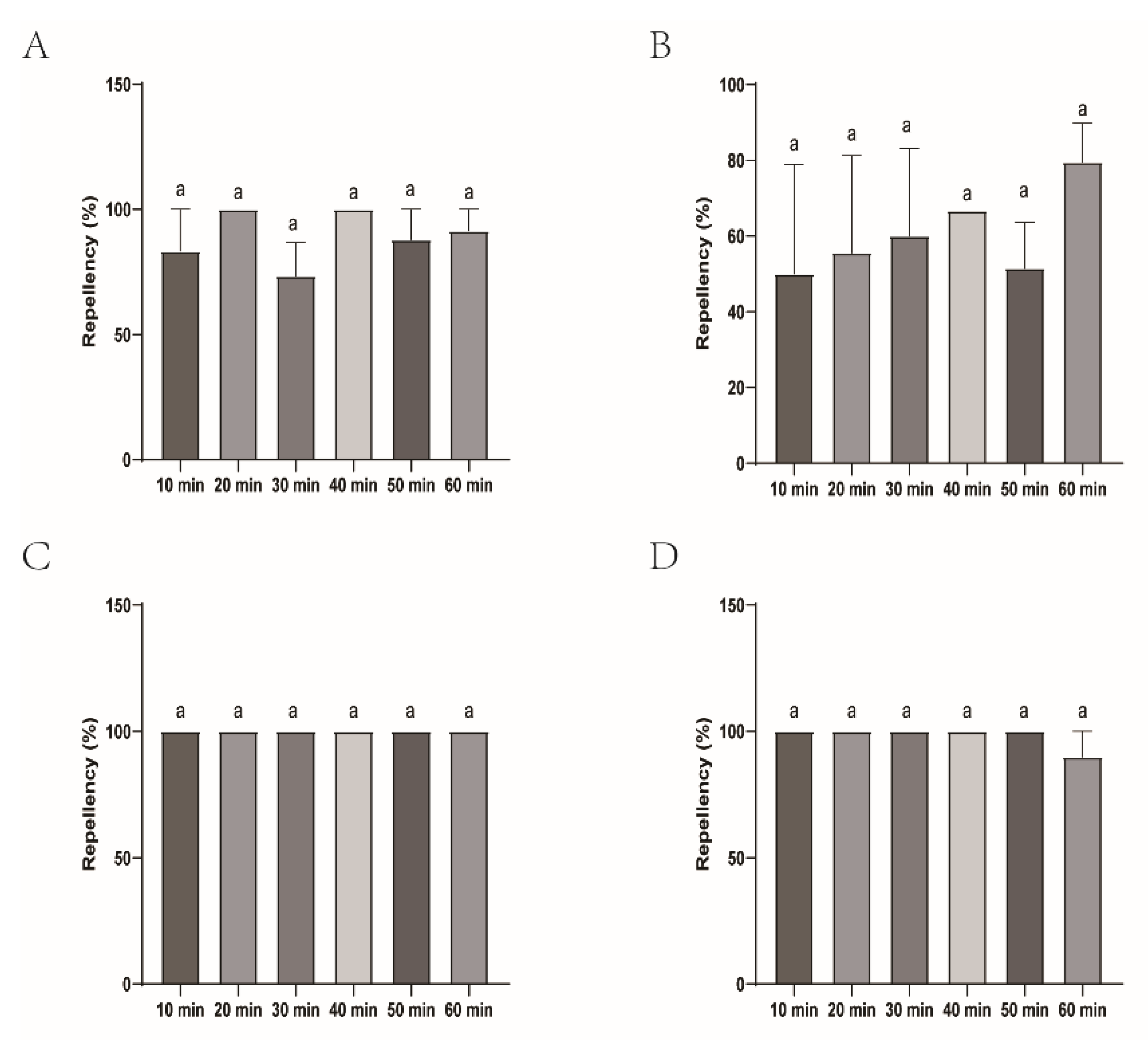

Figure 8.

Repellency of H. longicornis larvae over time after exposure to the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-P; B, Longhu; C, CaliforniaBaby; D, Bendingding.

Figure 8.

Repellency of H. longicornis larvae over time after exposure to the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-P; B, Longhu; C, CaliforniaBaby; D, Bendingding.

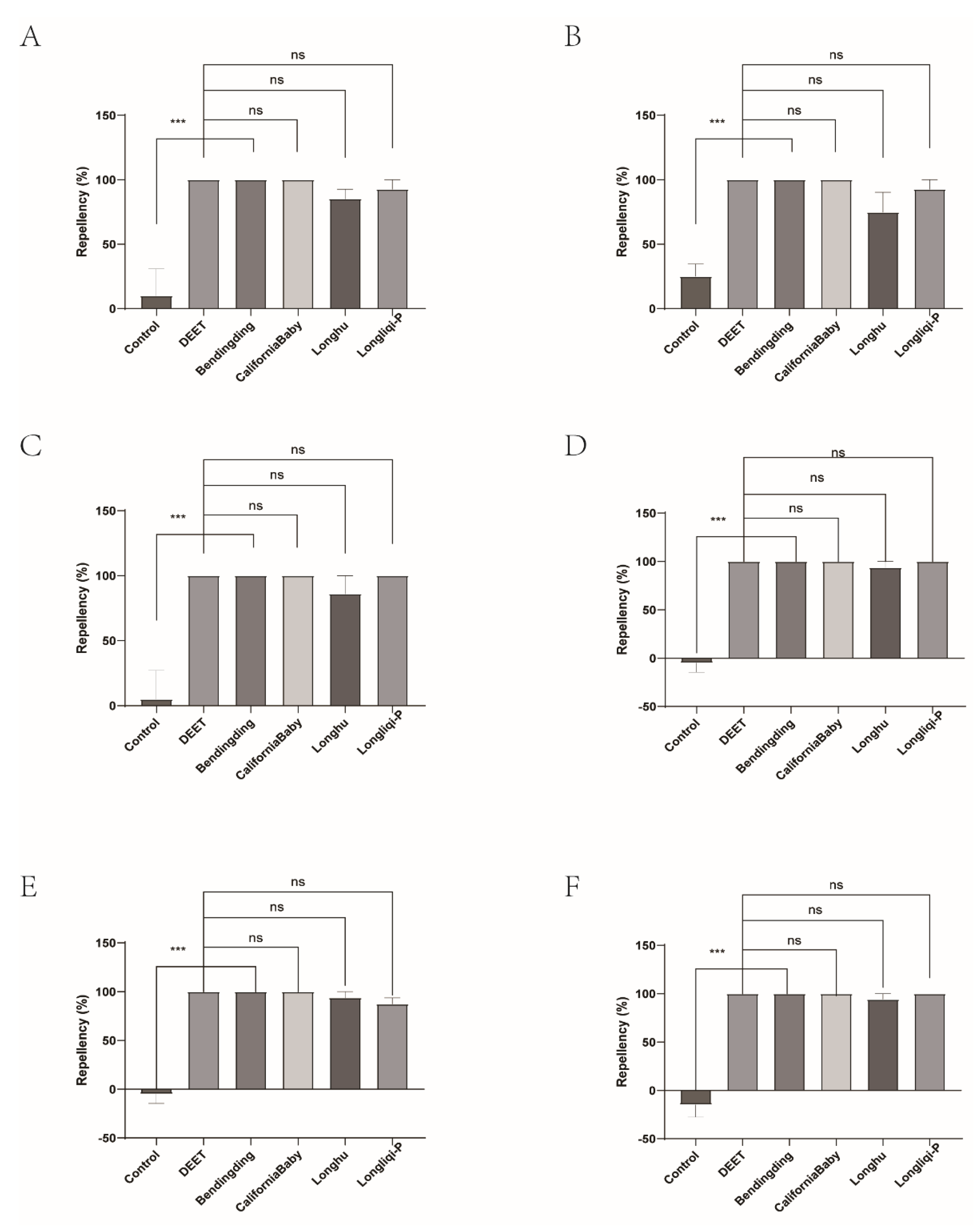

Figure 9.

The effect of the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents against H. longicornis nymphs. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

Figure 9.

The effect of the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents against H. longicornis nymphs. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

Figure 10.

Repellency of H. longicornis nymphs over time after exposure to the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-P; B, Longhu; C, CaliforniaBaby; D, Bendingding.

Figure 10.

Repellency of H. longicornis nymphs over time after exposure to the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-P; B, Longhu; C, CaliforniaBaby; D, Bendingding.

Figure 11.

The effect of the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents against H. longicornis females. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

Figure 11.

The effect of the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents against H. longicornis females. A, Repellency at 10 min post treatment; B, repellency at 20 min post treatment; C, repellency at 30 min post treatment; D, repellency at 40 min post treatment; E, repellency at 50 min post treatment; F, repellency at 60 min post treatment.

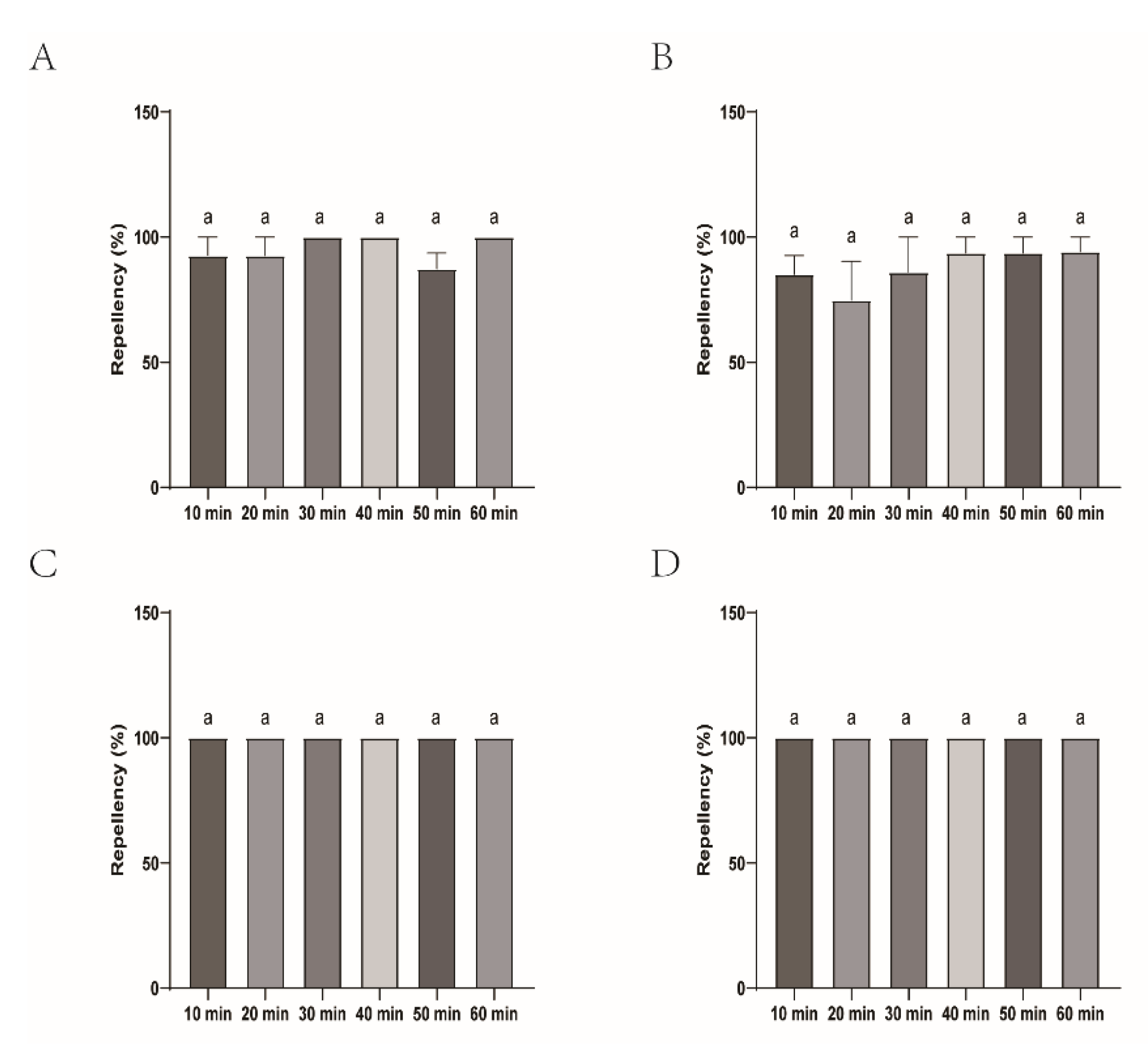

Figure 12.

Repellency of H. longicornis females over time after exposure to the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-P; B, Longhu; C, CaliforniaBaby; D, Bendingding.

Figure 12.

Repellency of H. longicornis females over time after exposure to the four commercial biont-based mosquito repellents. A, Longliqi-P; B, Longhu; C, CaliforniaBaby; D, Bendingding.

Table 1.

Widely available mosquito repellents tested in this study.

Table 1.

Widely available mosquito repellents tested in this study.

| No. |

Product |

Component |

No. |

Product |

Component |

| 1 |

Yamei |

10%DEET |

5 |

Longhu |

Geranium extract and clove leaf oil |

| 2 |

Longliqi-D |

5%DEET |

6 |

Longliqi-P |

Snake bile extract |

| 3 |

Johnson |

7%DEET |

7 |

CaliforniaBaby |

Extracts of citronella grass and East Indian lemongrass |

| 4 |

Xiaohuanxiong |

5%DEET |

8 |

Bendingding |

Lemongrass essential oil |

Table 2.

Repellency index (±SE) of CaliforniaBaby after different drying times in hours in unfed H. longicornis nymphs.

Table 2.

Repellency index (±SE) of CaliforniaBaby after different drying times in hours in unfed H. longicornis nymphs.

| Product |

Time (hours) |

Repellency (%) |

Classification |

| Control |

2 |

13.33±13.33 |

Neutral |

| 4 |

3.70±9.94 |

Neutral |

| 6 |

12±5.95 |

Neutral |

| DEET |

2 |

76.92±13.32 |

Repellent |

| 4 |

84.62±6.92 |

Repellent |

| 6 |

92.31±7.58 |

Repellent |

| CaliforniaBaby |

2 |

76.92±13.32 |

Repellent |

| 4 |

76.13±11.99 |

Repellent |

| 6 |

84.62±7.58 |

Repellent |